1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has dramatically affected our planet in its entirety, with the total amount of registered cases reaching about 250 million by November 2021, just a year and a half after the pandemic began [

1]. Due to the arrival of new variants, this figure even tripled by the end of the same winter [

2]. The impact on people's health was immense, with 5 million of detected deaths rising to almost 7 during the same period [

1]. Although the virus reached every continent, its spreading varied significantly in different geographical habitats, seasons, and communities [

3,

4,

5] and factors related to this phenomenon are still under study worldwide [

6,

7].

In Italy, for example, in the northernmost province of Bolzano, also called South Tyrol, the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic showed epidemiological characteristics differing greatly both from the neighbouring territories and across its territory, especially during winter 2021/22 [

8,

9]. This area has also peculiar and heterogeneous geomorphological and socio-cultural characteristics. Its natural environment resembles that of further northern countries, although the peaks of the southern Alpine slope protect it from the cold polar currents, giving it a sunny Mediterranean climate [

10]. Further, its multifaceted historic background is reflected in a great socio-cultural heterogenicity of its inhabitants, with 65% of the population being German-speaking and evenly distributed across the territory, 30% Italian-speaking and concentrated in the low altitude cities, and 5% Ladin, a local ancient population of the higher mountains, although there is considerable mixing between groups [

11].

South Tyrol is administered as an 'autonomous statute region' and divided into 20 health districts grouped into four sections built up around the four largest municipalities in the area (Bolzano, Merano, Bressanone and Brunico), where the main health services are located [11,12). The section of Bolzano, the densely populated capital city, includes both the southern, low-lying districts, with a strong Italian cultural influence, and those higher up, more anchored in the German or Ladin tradition. Around Merano, the districts are mostly composed by isolated rural sunny valleys devoted to agriculture and farms. The Bressanone section is a predominantly mountain area, where low tourism is balanced by high trade, thanks to the presence of the main link between Italy and Austria. Finally, the Brunico section is characterised by isolated and highly touristy valleys, which are important links with Austria and the other Italian Dolomite regions [12).

Literature investigating the epidemiological variability of the disease related to health services provision and vaccination coverage (herd immunity) and to the geographical or cultural characteristics that mark this territory, such as altitude, tourism, population dynamics, is scarce, and evidence is conflicting [9,13–16). Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate whether the deep geographical heterogeneity of socio-cultural, morphologic, and health-related features characterizing Soth Tyrol territory (northern Italy) can be related to the differing spread of SARS-CoV-2 observed across the region in the first winter of the pandemic characterized by the absence of social restrictions and the availability of an effective preventive measures, including vaccination.

2. Materials and Methods

We carried out an ecological study based on the 20 districts composing the Province of Bolzano (South Tyrol), Italy. Aggregated data on geomorphological, socio-cultural, health service-related features and SARS-CoV-2 cases and deaths were collected from the Local Health Authority (SABES) [17) or the Provincial Institute of Statistics (ASTAT) [18)

Geographical, socio-demographic and health service-related variables of the area were the exposure variables of interest, while SARS-CoV-2 epidemiological measures of occurrence (incidence, hospitalisation, or death) were the outcomes evaluated.

The study protocol was approved by the Bolzano Hospital Ethics Committee on 16th March 2022 (Prot. 0259655-BZ).

2.1. Exposure Variables

Geomorphological, socio-cultural and health service-related data was taken from the public ASTAT database (accessed in April 2024), referring to the most recent period available for each variable [18). Information on vaccination coverage was provided by the Local Health Authority [17).

The following data was available.

Demographics:

Inhabitants, represented by the resident population amount (2021);

Population density (people living for every square km, 2021);

Social dynamics variables:

Average yearly salary, for employees in the private sector (2019, before the pandemics);

Winter tourism, expressed as tourist amount (November – April 2019);

Geographic variables:

Presence of main cities

Average altitude, or vertical distance above the reference sea level (meters, current);

Bordering with other Italian regions through winter-opened mountain passes or ordinary roads (current);

Bordering with other countries (Austria and Switzerland) through the same roads (current).

Health Services-related variables:

Number of pharmacies every square km (2010);

Presence of small (without an intensive care unit - ICU) or big sized (with ICU) hospitals (current) [17);

Primary series vaccination coverage, updated as of 12 February 2022 and expressed as the number of subjects who got primary vaccination reported to total resident population (%). In this variable we included subjects with one dose of viral vector vaccine, two of mRNA vaccine or one of any with a previous infection, in the timeframe and with the vaccines authorized by the Italian Health Ministry [19,20);

Booster/additional dose coverage; a variable including number of subjects who got a booster (or additional) dose of vaccine with the serums defined by the Italian Health Ministry reported to total resident population, updated as of February 12, 2022, and expressed as a percentage. [21) The booster vaccination campaign in South Tyrol began in November 2021 and was initially reserved for the most vulnerable.

2.2. Outcome Variables

Health data on SARS-Cov-2 cases referring to winter season 2021-2022 was provided by the Epidemiological Surveillance Unit of Bolzano that oversaw tracking SARS-CoV-2 cases on the entire territory of South Tyrol [11).

The following information was available.

SARS-CoV-2 cases: a total number of all new cases occurred among resident population between 1st November 2021 and 12th February 2022. To this category belong all patients who had taken a diagnostic swab with a positive result in any authorised centre of the province without a recorded positive result in the previous 90 days [22).

Hospitalisations: total number hospitalisation related to the SARS-CoV-2 cases occurring up to 21 days (lastly up to 4th March 2022) after diagnosis. Total hospitalisations for COVID-19 and ICU-admissions were considered. Admissions were excluded if referring to patients who were positive but asymptomatic for COVID and suffered from diseases unrelated to the infection.

Deaths: total number of deaths caused or contributed by SARS-CoV-2, linked to the cases included in the study and occurring up to 21 days (lastly up to 4th March) after diagnosis.

2.3 Data Processing

ASTAT data were displayed by municipality, so an aggregation of data at district level was performed to make them comparable with district-related outcome data, following the belongings of each municipality to the 20 districts, as depicted in Supplementary

Table 1.

A sum was made for the amount variables, such as winter tourists, inhabitants, and surface. A weighted average for the number of inhabitants was performed to assess districts’ average salary. Average altitude, pharmacies density and population density were weighted for the surface size, while the highest municipality value about hospital presence and size, borders information and main cities was used for the district.

Outcomes amounts were clustered for each district and derived into epidemiological measures.

Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 during whole winter 2021/22 was calculated for each district relating the cases amount to the number of inhabitants and expressed per 100,000 inhabitants.

Hospitalisation Rates were assessed in the same way, relating both ordinary and ICU admissions to the inhabitant amount of each district and reported every 100,000 inhabitants.

Hospitalisation proportion correspond to the number of both ordinary and ICU admissions related to the number of cases in the same district and expressed per 10,000 cases.

Mortality and case fatality rate (CFR) were assessed relating the district’s death amount respectively per 100,000 inhabitants and per 10,000 cases.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

The variables were firstly summarized by descriptive analyses, after which correlations and bivariate non-parametric statistical analyses were performed (Spearman's correlation, Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney-U tests) to assess the relationships between the variables.

The variables associated with each outcome (p-value<0.1) were then analysed together by multiple linear regression, performing the model for the outcomes with at least three non collinear variable associated with it. An easier interpretable scale for the exposure variable was used in the model: population density was considered for inhabitant every hectare (10,000 m2), winter tourist amount expressed by 100,000 units and altitude expressed in kilometres. Variables with VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) >5 were considered collinear and not included in the linear regression. The distribution of residuals and Nagelkerke's adjusted R square were evaluated to ensure a good fit of the model to the data.

Statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi software [23).

3. Results

3.1. Main Features of the Area

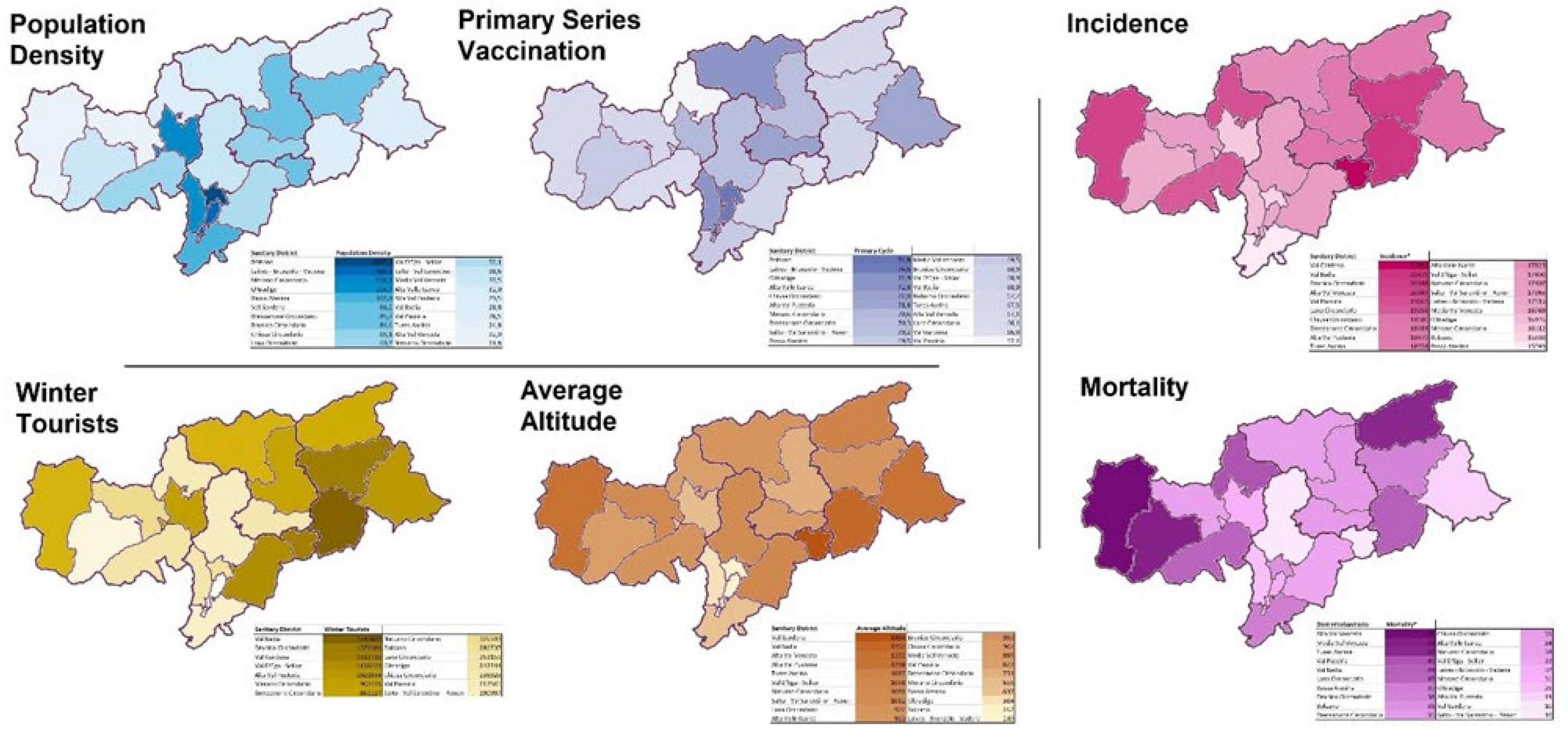

The twenty districts in the province of Bolzano differ greatly in geomorphological and socio-cultural characteristics and health-care facilities distributions, as shown in

figure 1 and

Supplementary Table 2 and 3.

Four districts are directly connected with Austria, 6 with other Italian regions. Laives-Bronzolo-Vadena (LBV) has the lowest altitude (249 m to the sea level), Val Gardena the highest (1454 m), the median of the province is 961 m (IQR of 338).

The number of inhabitants (district median:20,259; IQR:11,536) ranges from less than 10,000 in Val Passiria, to over 100,000 in Bolzano; that of winter tourists (median:491,182; IQR:701,423). from 78,618 in LBV to 1.7 million in Val Badia. The lowest wage in the private sector is in Val Passiria (25,591 euros/year), the highest in Brunico (29,132 euros/year).

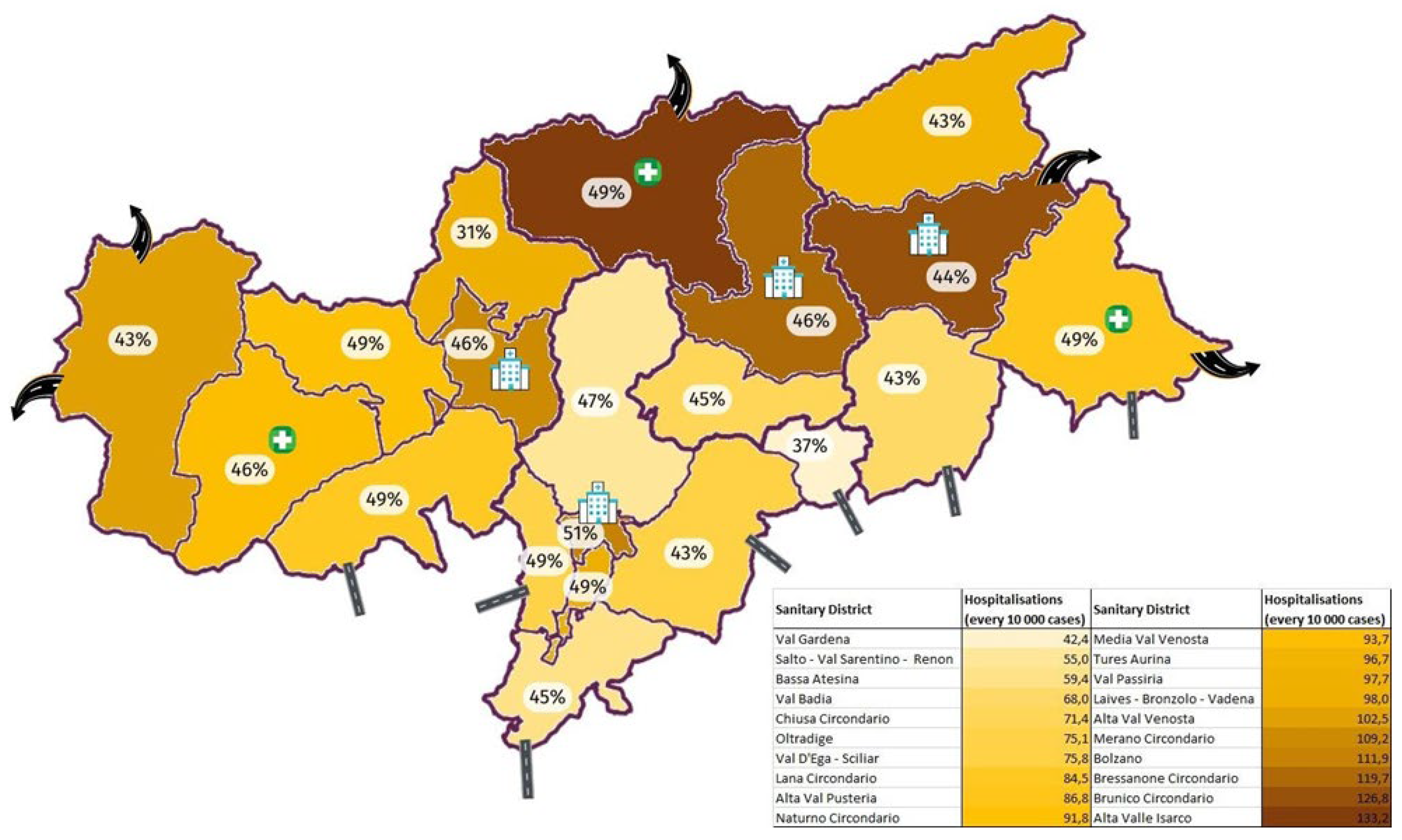

Big hospitals are located in the four main cities (Bolzano, Merano, Bressanone, Brunico) and the small one in Media Val Venosta, Alta Val Pusteria and Alta Valle Isarco. Pharmacies for each district are in median 1 every 100 square km. At winter 2021/22 end, primary series vaccination coverage varied extremely, with an IQR between 68% and 72% (median:70%); booster dose coverage 43% - 46% (median 45%). Lowest values are in Val Passiria (57% primary series, 31% booster), highest in Bolzano (75% and 51%).

The geographical distribution of SARS-Cov-2 pandemic is shown in

Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 4. Outcomes varied greatly across districts. SARS-CoV-2 incidence was lowest in Bolzano and highest in Val Gardena, with an overall district median of 18,090 cases per 100,000 inhabitants (IQR:2,356). Hospitalization rate (per 100,000 inhabitants) ranged from 90 in Bassa Atesina to 256 in Brunico (district median:162; IQR:48). ICU admissions rate median was 15 per 100,000 inhabitants (IQR:4 - 23). District median of CFR was 19 per 10,000 cases (IQR:4), ranging between 5 in Val Gardena and 31 in Media Venosta.

3.2. Territorial Characteristics and SARS-Cov-2 Epidemiology

According to bivariate analyses (table 1 and 2) SARS-CoV-2 incidence at district level appeared significantly correlated to several district factors and features, including the total number of inhabitants and of winter tourists, the average altitude and primary and booster dose coverage. Health care facilities distribution, on the contrary, did not result associated with any significative variation of this parameter.

Table 1.

SARS-Cov-2 incidence, hospitalisation and mortality correlation (Spearman’s Rho, p-value) with quantitative district characteristics of the 20 districts in Soth Tyrol, Italy, during winter 2021/22.

Table 1.

SARS-Cov-2 incidence, hospitalisation and mortality correlation (Spearman’s Rho, p-value) with quantitative district characteristics of the 20 districts in Soth Tyrol, Italy, during winter 2021/22.

| District Characteristics |

Incidence* |

Hospitalisation Rate* |

ICUa Admission Rate* |

Mortality* |

Hospitalisation on cases** |

ICUa Admission on cases** |

Case fatality rate** |

| Demographics |

Inhabitants |

-0.54

(0.015) |

0.19

(0.416) |

-0.27

(0.253) |

-0.17

(0.478) |

0.4

(0.077) |

-0.23

(0.332) |

-0.09 (0.696) |

| |

Population Density |

-0.44

(0.050) |

-0.18

(0.435) |

-0.54

(0.014) |

-0.4

(0.077) |

0.03

(0.905) |

-0.52

(0.020) |

-0.36 (0.120) |

| Social dynamics |

Average Salary |

0.269

(0.250) |

−0.114

(0.630) |

0.093

(0.697) |

−0.289

(0.216) |

−0.205

(0.385) |

0.091

(0.704) |

−0.462 (0.040) |

| |

Winter Tourism |

0.54

(0.015) |

0.22

(0.359) |

0.29

(0.208) |

-0.11

(0.645) |

0.12

(0.627) |

0.29

(0.218) |

-0.2 (0.405) |

| Health Services |

Primary Series |

-0.62

(0.004) |

0.01

(0.970) |

-0.4

(0.081) |

-0.43

(0.061) |

0.25

(0.298) |

-0.4

(0.080) |

-0.36 (0.123) |

| |

Booster Dose |

-0.68

(0.001) |

0.11

(0.65) |

-0.38

(0.095) |

-0.34

(0.139) |

0.39

(0.091) |

-0.37

(0.11) |

-0.23 (0.326) |

| |

Pharmacies (/km2) |

-0.326

(0.161) |

-0.095

(0.690) |

-0.436

(0.055) |

0.109

(0.647) |

-0.424

(0.062) |

-0.401

(0.080) |

-0.363 (0.116) |

| Geography |

Average Altitude |

0.67

(0.001) |

-0.11

(0.631) |

0.23

(0.339) |

0.04

(0.865) |

-0.34

(0.141) |

0.19

(0.420) |

-0.05 (0.830) |

Table 2.

SARS-Cov-2 incidence, hospitalisation, and mortality (median, IQR, p-value) according to qualitative characteristics SARS-Cov-2 incidence, hospitalisation and mortality.

Table 2.

SARS-Cov-2 incidence, hospitalisation, and mortality (median, IQR, p-value) according to qualitative characteristics SARS-Cov-2 incidence, hospitalisation and mortality.

District

Characteristics |

Incidence* |

Hospitalisation Rate* |

ICUa

Admission Rate* |

Mortality* |

Hospitalisation on cases** |

ICUa

Admission

on cases** |

Case

fatality rate** |

Health

Services |

Big hospitals |

17298

(16035 - 18910) |

199

(177 - 230) |

20

(14 - 29) |

36

(34 - 37) |

116

(111 - 121) |

12

(8 - 16) |

19

(19 - 20) |

| |

Small hospitals |

17825

(16969 - 18479) |

160

(159 - 237) |

5.3

(4.8 - 24.7) |

33.9

(18.5 - 53) |

94

(87 - 133) |

3.1

(2.7 - 13.4) |

19

(10 - 31.2) |

| |

No hospitals |

18354

(17365 - 19661) |

139

(123 - 168) |

12.5

(0 - 23.1) |

34.6

(31.7 - 43.5) |

76

(68 - 97) |

6.2

(0 - 12.4) |

19.3

(18.5 - 23) |

| |

p-value |

0.707 |

0.054 |

0.739 |

0.993 |

0.01 |

0.683 |

0.987 |

| Geography |

Main Cities |

17298

(15958 - 19336) |

199

(176 - 239) |

19.9

(10.6 - 35.3) |

35.5

(32.9 - 37.1) |

116

(111 - 123) |

11.7

(5.9 - 18.9) |

19.1

(18.8 - 21.1) |

| |

Rural/ Towns |

18090

(17240 - 19510) |

159

(128 - 173) |

8.9

(1.9 - 23.9) |

34.3

(28.9 - 44.4) |

86

(70 - 97) |

4.7

(1.3 - 12.9) |

19.2

(17.2 - 24.4) |

| |

p-value |

0.617 |

0.029 |

0.554 |

0.963 |

0.005 |

0.437 |

0.963 |

| |

Bordering with abroad |

19263

(18152 - 20118) |

221

(183 - 247) |

18.6

(8.7 - 36.4) |

36

(26.2 - 47) |

115

(95 - 130) |

9.8

(4.5 - 18.6) |

18.9

(14.4 - 23.5) |

| |

Not bordering |

17419

(16708 - 18974) |

159

(128 - 176) |

11.3

(1.9 - 22.8) |

34.7

(31.4 - 43.2) |

88

(70 - 98) |

5.8

(1.2 - 13.2) |

19.3

(18.6 - 23) |

| |

p-value |

0.178 |

0.022 |

0.335 |

0.82 |

0.05 |

0.437 |

0.82 |

| |

Bordering with Italian regions |

18479

(16446 - 20475) |

132

(93 - 160) |

4.7

(0 - 19.5) |

33

(18.5 - 42.8) |

75

(59 - 84) |

2.7

(0 - 10.1) |

18.9

(10 - 22.1) |

| |

Not bordering |

17825

(17115 - 18589) |

177

(160 - 206) |

17.4

(4.8 - 33.7) |

34.8

(33.7 - 45.2) |

98

(94 - 112) |

9.4

(2.7 - 19.3) |

19.3

(18.8 - 23) |

| |

p-value |

0.643 |

0.006 |

0.275 |

0.351 |

0.003 |

0.211 |

0.351 |

Both hospitalization rate and the proportion of hospitalization cases resulted significantly higher in districts with main hospitals and cities and in districts bordering with other countries or not bordering with other Italian regions. District ICU hospitalization, the proportion of ICU cases, mortality and CFR resulted less related to the ecological variables analyses in this study, excluding population density for ICU admission rate or proportion of cases or average salary for CFR.

The results of the multiple linear regressions, carried out with incidence or hospitalisations proportion as outcome, are shown in

Table 3. Due to collinearity issues a limited number of variables could be included in the models (Supplementary table 5).

SARS-CoV-2 incidence was mainly related to vaccination coverage (p-value=0.033). while the result of the linear regression for hospitalisations identified geographical location and the presence and size of hospitals as the most statistically reliable predictors. The distribution of the variables included in the second model and of the outcome is represented graphically in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

During winter 2021/22, SARS-CoV-2 was diagnosed in almost one out of every six people in Bolzano province (South Tyrol). However, the incidence was unevenly distributed across the territory, reflecting its complexity. According to our ecological study, the variable mostly related with its distribution across districts was the vaccination coverage [9). In addition, different geographical and social-demographic features of the territory appeared to play a role in the spread of the disease as incidence was higher in districts where population density was greater, in traditional mountain areas and in those with higher tourist flows.

ICU admissions and mortality due to COVID-19 partially tracked the incidence, being higher at higher altitudes and in districts with less vaccination coverage, while higher rates of overall hospitalization were observed in the districts bordering with other countries in the northern, and lower rates in those with the Italian regions to the south. Moreover, hospitalization was highest where the capacity of healthcare facilities was the greatest, i.e. in major cities, where major hospitals are located, and the lowest in districts where hospitals are absent. Case fatality rate (CFR), on the other hand, was found to be negatively correlated with the average district salary.

The results of this study can be evaluated in the light of the existing literature, even though comparisons can be difficult due to the scarcity of studies analysing similar variables often reporting contrasting results [7,24). The role played by altitude, for example, is still unclear as it has been found in previous studies to be both negatively and positively associated with the spread of the disease [13), and this relationship is only partially supported by pathophysiological hypotheses [25). Population density and number of inhabitants, on the other hand, resulted almost always positively associated with incidence, since a larger and more concentrated population increases human contact and consequently also the likelihood of contagion. In our study we found similar correlations; nevertheless, the strength of these relationships fades when performing multivariate analyses.

Indeed, vaccination coverage confirmed to be the most relevant predictor of geographical distribution of SARS-CoV-2 incidence, being also associated to intensive care admissions and deaths. Although this is one of the first studies suggesting the presence of a herd immunity effect at ecological level, a lower prevalence of the disease had already been predicted at a higher vaccination coverage [16), and the effectiveness of vaccination at the individual level has been well established in preventing severe SARS-CoV-2 disease [26,27), but also the contagion, both through increased protection against infection [28) and less contagiousness [29). The lower vaccination coverage could be therefore the underlying reason of the increased incidence of the disease in the less inhabited and higher districts, geographically and culturally distant from the national health governance.

Finally, we analysed the role played by winter tourism, which is an important part of the local economy and was considered responsible for a significant spread of the virus in the first pandemics wave. However, our study highlights how during the winter 2021/22 tourism contributed to a limited extent to the spread of the disease, not followed by an increase of the severe form. This is probably due to an effective implementation of the social and community preventive measures, such as isolation of positive people, social distancing, personal protection equipment (PPE), mandatory during that winter. Effective public health training and communication might prove to be crucial for managing outbreaks [

30,

31]. Clear communication on prevention and vaccination might help build trust and compliance with public health measures.

Geographical and socio-demographic features of this territory seems to have a greater influence on the hospital admissions, that did not follow exactly the distribution of incidence, ICU admissions and mortality, and that resulted linked also to other variables, such as geographical location (higher rates were observed on the northern border with other countries, lower in the south close to the other Italian regions), and accommodation capacity of health facilities. If for the former association we can assume a protective role of the milder and sunnier climate in the southern districts of the province [32), as already shown by other reliable studies [4,5), the second association strongly suggests that living in a district with highly responsive healthcare structures, facilitates access to it, underlying the potential of health inequalities. The possible presence of health disparities is further highlighted by the negative correlation between the CFR of infection and the average income of the district.

Finally, regional infectious disease surveillance system is vital for monitoring and controlling disease spread. It allows for the timely collection and analysis of data, helping to identify outbreaks early and implement targeted interventions [

33,

34]. In Bolzano province, localized surveillance revealed how factors like vaccination coverage and population density influenced SARS-CoV-2 incidence. This enables efficient resource allocation and tailored public health measures, reducing disease burden.

This article has considerable strengths, such as the possibility of including all SARS-Cov-2 cases occurred in the period of interest and of analysing a very wide and varied range of geographical, socio-cultural, heath related variables in the area studied. Nevertheless, there are also some important limitations, first of all that of analysing only a specific period of the pandemic (winter 2021/22), without therefore considering the previous waves, the deaths that had already occurred and their distribution, although the total number of cases recorded in the province up to that time we considered was less than a third of that at the end of the period studied [35).

Furthermore, a possible under-diagnosis could be occurred, especially in the more vaccinated district, since during the period under study only non-vaccinated subject had to routinely test negative to obtain a green pass to work or participate in most social activities [36). Consequently, this could have led to the detection of a higher number of asymptomatic cases in districts with fewer vaccination coverage, explaining the higher incidence. However, ICU admissions rate and mortality distribution, showed similar correlations patterns of incidence rate, and similar associations patterns were observed when considering cases or inhabitants as rate denominators all these findings suggest a uniform detection of cases across the territory. Furthermore, the number of COVID-19-positive hospitalizations and deaths data should be really accurate, since all hospitalized and deceased subjects were tested, and no private hospitals for acute diseases are found in in South Tyrol.

Finally, ecological bias cannot be ruled out. Further studies based on individuals are, therefore, needed to investigate further the main findings emerging from this study.

5. Conclusions

This study, by analysing the distribution of SARS-CoV-2 and its outcomes during a high incidence period in the multifaceted territory of South Tyrol, shows that, besides the effective protective effect played by vaccination coverage, several geographical and socio-cultural variables can be associated with the disease incidence, hospitalisation, and mortality. Overall, more remote and higher altitude areas with fewer availability of health facilities suffered the most, confirming the need of targeting specific subgroups and geographical areas by implementing specific territorial tailored public health interventions to address more efficiently potential heath inequities and reduce social and economic health related costs both to individuals and society.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Supplementary

Table 1: The 118 municipalities in South Tyrol grouped in the 20 districts and 4 health sections to which they belong; Table S2: Quantitative variables representing the geo-morphological and social characteristics of each district, health section and the whole province; Table S3: Qualitative variables representing the geo-morphological and health-service related characteristics of each district, health section and the whole province; Table S4: Distribution of outcomes in each district, health section and in the whole province; Table S5: Collinearity diagnoses between variables analysed in the two linear regressions.

Author Contributions

AL contributed to all the phases of the present work accompanied by LP; AL, RP, FL, CC, and FZ actively participated in the collection of the data; CR participated in the literature search together with FU. AL, LP, and FU performed data analysis as well as writing the first draft of the manuscript; Critical analysis of results was performed by CC, FZ, and PB. All phases of the study took place under the critical supervision of ER. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors thank the Department of Innovation, Research, University and Museums of the Autonomous Province of Bozen/Bolzano for covering the Open Access publication costs.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the South Tyrolean Healthcare Agency on 16th February 2022 with protocol code 0259655.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Diego Gallino, Fabrizio Selmi and Dieter Nardon for assistance with data management and programming; Marco Vinceti and Josef Widmann for the positive management of the working environment, which was supportive of this research project; Federica De Giuli of the Ethics Committee for their commendable kindness; Francesca Verginella and Elisabetta Pagani for their helpfulness in providing data; Michael Mian, Paola Zuech and Antonio Fanolla for their availability in providing support for the research; Patrizia Corazza, Sabina Sani, Elisabetta Calcaterra and the whole medical, nursing and administrative staff of the epidemiological surveillance unit for their intensive professional contribution. Finally, a very special thanks goes to Anna Maria Bassot, without whom this project would never have existed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Worldometer. Coronavirus Graphs: Worldwide Cases and Deaths. Available from: https://www.worldometers.

- Duong BV, Larpruenrudee P, Fang T, Hossain SI, Saha SC, Gu Y, et al. Is the SARS CoV-2 Omicron Variant Deadlier and More Transmissible Than Delta Variant? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4586. [CrossRef]

- Zeberg H, Pääbo S. The major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals. Nature. 2020;587(7835):610–2. [CrossRef]

- Landier J, Paireau J, Rebaudet S, Legendre E, Lehot L, Fontanet A, et al. Cold and dry winter conditions are associated with greater SARS-CoV-2 transmission at regional level in western countries during the first epidemic wave. Sci Rep. 2021;11:12756. [CrossRef]

- Smit AJ, Fitchett JM, Engelbrecht FA, Scholes RJ, Dzhivhuho G, Sweijd NA. Winter Is Coming: A Southern Hemisphere Perspective of the Environmental Drivers of SARS-CoV-2 and the Potential Seasonality of COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5634. [CrossRef]

- Meyerowitz EA, Richterman A, Gandhi RT, Sax PE. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: A Review of Viral, Host, and Environmental Factors. Ann Intern Med. 2020;M20-5008. [CrossRef]

- Vandelli V, Palandri L, Coratza P, Rizzi C, Ghinoi A, Righi E, et al. Conditioning factors in the spreading of Covid-19 – Does geography matter? Heliyon. 2024;10(3):e25810. [CrossRef]

- Open data Ministero della Salute. COVID-19 – Situazione Italia. Available from: https://opendatamds.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/0f1c9a02467b45a7b4ca12d8ba296596.

- Lorenzon A, Palandri L, Uguzzoni F, Cristofor CD, Lozza F, Poluzzi R, et al. Effectiveness of the SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Preventing Severe Disease-Related Outcomes: A Population-Based Study in the Italian Province of Bolzano (South Tyrol). Int J Public Health. 2024;69:1606792. [CrossRef]

- Elvidge AD, Renfrew IA. The Causes of Foehn Warming in the Lee of Mountains. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 2016 Mar 1;97(3):455–66. [CrossRef]

- Alcock, A. The Protection of Regional Cultural Minorities and the Process of European Integration: the Example of South Tyrol. International Relations. 1992;11(1):17–36. [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. South Tyrol. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=South_Tyrol&oldid=1181193098.

- Millet GP, Debevec T, Brocherie F, Burtscher M, Burtscher J. Altitude and COVID-19: Friend or foe? A narrative review. Physiol Rep. 2021;8(24):e14615. [CrossRef]

- Weaver AK, Head JR, Gould CF, Carlton EJ, Remais JV. Environmental Factors Influencing COVID-19 Incidence and Severity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43:271–91. [CrossRef]

- Pun M, Turner R, Strapazzon G, Brugger H, Swenson ER. Lower Incidence of COVID-19 at High Altitude: Facts and Confounders. High Alt Med Biol. 2020;21(3):217–22. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez VJ, Hormeño-Holgado A, Jiménez M, Benitez-Agudelo JC, Navarro-Jiménez E, Perez-Palencia N, et al. Dynamics of Population Immunity Due to the Herd Effect in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(2):236. [CrossRef]

- Azienda Sanitaria dell’Alto Adige. Home page. Available from: https://www.asdaa.

- Provincia autonoma di Bolzano - Alto Adige. Istituto provinciale di statistica. Available from: https://astat.provincia.bz.it/it/default.

- Frei A, Kaufmann M, Amati R, Butty Dettwiler A, von Wyl V, Annoni AM, et al. Development of hybrid immunity during a period of high incidence of Omicron infections. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2023;52(6):1696–707. [CrossRef]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/03/04/22A01497/sg.

- Provincia autonoma di Bolzano - Alto Adige. In Alto Adige è in costante aumento il tasso di copertura vaccinale. Available from: https://news.provincia.bz.it/it/news-archive/663463.

- Gazzetta Ufficiale. Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri del 17 giugno 2021. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/06/17/21A03739/sg.

- Jamovi. Open statistical software for the desktop and cloud. Available from: https://cloud.jamovi.

- Palandri, L.; Rizzi, C.; Vandelli, V.; Filippini, T.; Ghinoi, A.; Carrozzi, G.; Girolamo, G.D.; Morlini, I.; Coratza, P.; Giovannetti, E.; et al. Environmental, Climatic, Socio-Economic Factors and Non-Pharmacological Interventions: A Comprehensive Four-Domain Risk Assessment of COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death in Northern Italy. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2025, 263, 114471. [CrossRef]

- Devaux CA, Raoult D.The impact of COVID-19 on populations living at high altitude: Role of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) signaling pathway in SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication. Front Physiol. 2022;13:960308. [CrossRef]

- Fiolet T, Kherabi Y, MacDonald CJ, Ghosn J, Peiffer-Smadja N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(2):202–21. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds L, Dewey C, Asfour G, Little M. Vaccine efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 for Pfizer BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines: a systematic review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Thirión-Romero I, Fernández-Plata R, Pérez-Kawabe M, Meza-Meneses PA, Castro-Fuentes CA, Rivera-Martínez NE, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Effectiveness in Hospitalized Patients: A Multicenter Test-Negative Case–Control Study. Vaccines. 2023 Dec;11(12):1779. [CrossRef]

- Braeye T, Catteau L, Brondeel R, van Loenhout JAF, Proesmans K, Cornelissen L, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against transmission of alpha, delta and omicron SARS-COV-2-infection, Belgian contact tracing, 2021–2022. Vaccine. 2023;41(20):3292–300. [CrossRef]

- Lugli, C.; Ferrari, E.; Filippini, T.; Corsini, A.G.; Odone, A.; Vinceti, M.; Righi, E.; Palandri, L. It’s (Not) Rocket Science: Public Health Communication Experience as Expressed by Participants to an International Workshop. Popul. Med. 2024, 6, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Palandri, L.; Urbano, T.; Pezzuoli, C.; Miselli, F.; Caraffi, R.; Filippini, T.; Bargellini, A.; Righi, E.; Mazzi, D.; Vigezzi, G.P.; et al. The Key Role of Public Health in Renovating Italian Biomedical Doctoral Programs. Ann Ig 2024. [CrossRef]

- Provincia autonoma di Bolzano - Alto Adige. Download dati – Meteo. Available from: https://meteo.provincia.bz.it/download-dati.

- Palandri, L.; Morgado, M.; Colucci, M.E.; Affanni, P.; Zoni, R.; Mezzetta, S.; Bizzarro, A.; Veronesi, L. Reorganization of Active Surveillance of Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) in Emilia-Romagna, Italy: A Two-Step Public Health Intervention. Acta Biomed 2020, 91, 85–91. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, E.; Scannavini, P.; Palandri, L.; Fabbri, E.; Tura, G.; Bedosti, C.; Zanni, A.; Mosci, D.; Righi, E.; Vecchi, E. Training in Infection Prevention and Control: Survey on the Volume and on the Learning Demands of Healthcare-Associated Infections Control Figures in the Emilia-Romagna Region (Northern Italy). Ann Ig 2024. [CrossRef]

- L’Adige.it. Coronavirus in Alto Adige, la situazione sta precipitando: altri 2 morti e 255 nuovi contagi nelle ultime 24 ore - Alto Adige - Südtirol. Available from: https://www.ladige.it/territori/alto-adige-s%C3%BCdtirol/2021/11/04/covid-in-alto-adige-la-situazione-precipita-altri-2-morti-e-255-nuovi-contagi-1.3045707.

- Gazzetta Ufficiale. Legge 21 gennaio 2022, n. 3. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/01/25/22G00006/sg.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).