1. Introduction

Heavy crude oil is a specific type of oil that has a high viscosity. It is called “heavy” for the simple reason that its specific gravity is relatively high. In fact, by definition, heavy crude oil has an API gravity of less than 20 and has a low solubility. Some of the world’s largest reserves are present in heavy oil reservoirs. The problem with heavy oil is not the lack of resources, but rather its production method; the high viscosity prevents the liquid from flowing naturally. Producing heavy crudes is a significant challenge that requires a high oil price to financially justify the operations.

Before 1985, heavy oil production was based on using thermal stimulation to reduce the viscosity. Some of the used techniques are cyclic steam stimulation huff ‘n’ puff, steam flooding, wet or dry in-situ combustion with air or oxygen, or even a combination of these previous methods. Several other methods were tried over the last decade but were never proved viable. These methods include solvent injection, biological methods, cold gas injection, polymer methods, and in-situ emulsification. Thermal stimulation was found to be the most successful, specifically the Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD), hot fluid injection, and in situ combustion. Use of microwave heating was discussed by Soliman 1997 [

1] and Banerjee, 2011 [

2].

A new technique that was found to overcome all these limitations is the use of microwaves. A microwave is an electromagnetic wave that is generated by a magnetron. The irradiations have a frequency between 300 MHz to 300 GHz and a wavelength between 1mm and 1 m. Polar material such as water, reacts to the waves by turning back and forth at the frequency of the microwave which creates heat. Oil on the other hand lacks this polarity; hence it will not heat up significantly when exposed to microwave irradiation. An array of microwave sources is lowered in the formation through the well, also called an “antenna” (Othman et al., 2017 [

3]; Naufel et al., 2013 [

4]; Demiral et al., 2008 [

5]). The irradiations of the microwave will heat the water in the formation, which in turn will heat the oil by conduction. This will decrease the viscosity of the oil and will increase the flow of the well.

A more efficient method for increasing the temperature within the reservoir formation has been identified. As previously discussed, microwave irradiation primarily heats the water present in the formation, which subsequently transfers heat to the oil through conduction. However, the direct heating of oil within the reservoir poses a significant challenge. Recent studies have demonstrated that the introduction of activated carbon can markedly enhance the thermal response within the formation (Othman, 2015 [

6]; Atwater & Wheeler, 2004 [

7]). Activated carbon exhibits high real and imaginary permittivity, properties that enable it to effectively absorb microwave energy and subsequently release it as heat into the surrounding environment. Due to these dielectric properties, activated carbon achieves elevated temperatures more rapidly than other naturally occurring materials in the reservoir, such as water and rock. This enhanced heating capability reduces the energy input required to achieve the target temperature, thereby optimizing the thermal recovery process in terms of both time and cost efficiency.

The use of activated carbon has been used extensively to clean contamination and spills in multiple industries due to its high absorption ability. The high absorption ability of activated carbon is not limited to absorbing spills but also to absorbing heat energy, specifically microwave energy. As reported by Othman et al., 2017 [

3], activated carbon has significantly higher real and imaginary permittivity values than any naturally existing materials in heavy oil reservoirs, namely water, oil, and rock. Real permittivity of a substance is the ability to absorb microwave energy while imaginary permittivity is the ability of this substance to convert this energy to heat. As a result, activated carbon will heat up to a very high temperature when microwave irradiation is directed at it and hence it will heat the reservoir. The use of activated carbon might increase the oil recovery factor between 5 and 14% when compared to the use of microwave only (Othman et al., 2017 [

3]; Renouf et al., 2003 [

8]).

Injection of Nano-Particles into the reservoir could be categorized as a method under tertiary recovery methods. These methods enhance oil recovery since they change one and/or many reservoirs rock and fluid properties of the reservoir. Examples of properties altered by Nano-particles are, but not limited to, water and oil viscosity, fluid/rock interfacial tension, and wettability. These changes sometimes are favorable causing higher oil recovery. The degree of the oil recovery depends on the type of Nano-Particle used. Different nano-particles have different additional recovery factors (Ogolo et al., 2012 [

9]). The Nano-particles used in this study are activated carbon. The property of activated carbon that is desirable in this research is its high permittivity (Othman et al., 2017 [

3]; Ferri and Uthe, 2001 [

10]).

Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of activated carbon as a substance in heating oil. It is well documented across the literature that activated carbon has a very high permittivity, heating up to four folds of water when both water and activated carbon are exposed to the same level of microwave energy (Othman et al., 2017 [

3]; Okassa et al., 2010 [

11]). In addition, the energy produced by a microwave costs the least per unit of energy among different heat energy sources used in the oil industry.

Based on the scientific facts that activated carbon has a very high permittivity and microwave energy is relatively the least expensive compared to other heating methods, the main objective now of this study is to successfully inject the optimum concentration of activated carbon Nano-particles into a sandstone core and heat it using microwave to reach the desired temperature in the most economical way. After achieving that, we can reflect that method on the field and inject that optimum concentration in a heavy oil reservoir to test the effect on the recovery. The study approach section of this work is divided into three main sections. The first section explains the steps used to test the objectives of this paper and how successful is the injection of Nano-particles activated carbon into a core. The second section will cover the optimization of the concentration of the nano-particles injected in the core. Finally, the last section discusses the investigation of the effect of salinity on microwave heating. This is crucial as the activated carbon is mixed with brine in the reservoirs.

2. Methodology

2.1. Nano-Particle Activated Carbons Injection

The purpose of this section is to find a transporting medium that would keep the activated carbon suspended well enough for the whole duration of the injection process. In this section the steps taken to inject Nano-particles activated carbon into the cores are presented. After each injection, the core is tested by heating it in the microwave and measuring the temperature of the core to check if the injection was successful. The particles are injected into the cores in a fluid serving as a transport medium. A guar-based fracturing fluid, LGW01, was used as the transport fluid. The activated carbons are just mixed in the fluid. Three different samples were prepared by adding 0, 0.1, up to 0.5 grams to 100 ml of the frac-fluid, yielding 0, 0.1% to 0.5% activated carbon Frac-Fluid solutions.

All the cores used were Brea Sandstone cores with a permeability ranging between 100 and 200 mD. All cores were injected with distilled water and then dried. For each fluid tested, the same core was divided into multiple smaller cores before the injection process to ensure the integrity of the results.

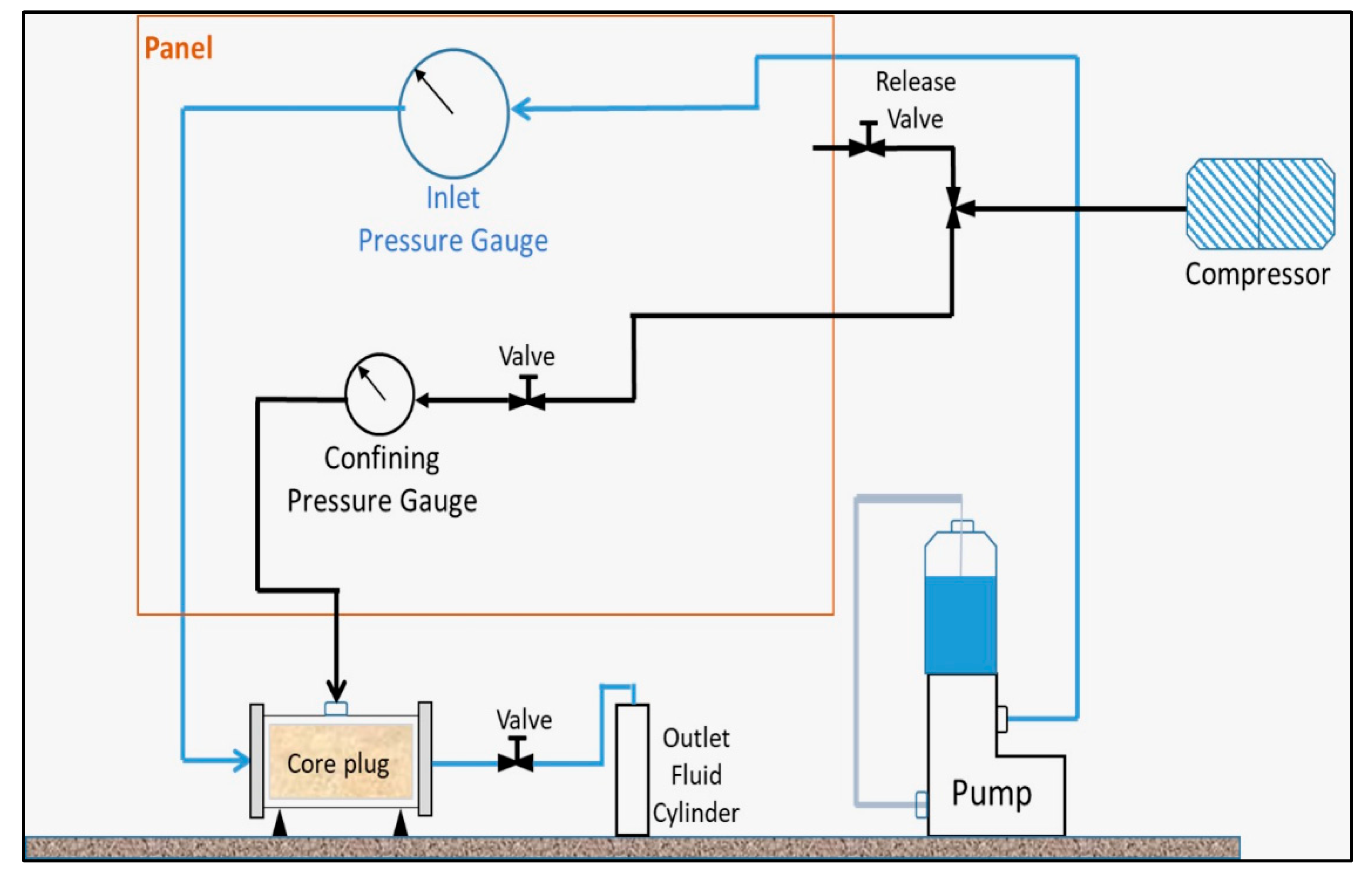

A positive displacement pump was used in the process. A schematic of the pump is shown in

Figure 1. For each fluid, the inlet pump pressure was monitored. Due to limited confining pressure, the rate of injection was set at 5 ml/min for the whole duration of the injection. The confining pressure could be applied by air or nitrogen, however, in this case we used air.

After injection, the cores are placed in a microwave and heated for 10 seconds and 1 minute. A successful transporting medium will deliver the activated carbon inside the core, resulting in higher temperature cores than the control cores that don’t have any activated carbons. After each core was microwaved, the temperature was measured using an infrared thermometer.

2.2. Activated Carbons Concentration Optimization

The target of the following step is the optimization of activated carbon concentration for maximum core heating. The experiment setup was a little different than the previous experiment. Seven different cores were tested. Six cores were injected with activated carbon solutions ranging from 0% to 0.5% in 0.1 increments. Since the fracturing fluid showed satisfactory results as a transport medium, various concentrations of activated carbon were prepared using the same fluid to find the optimum activated carbon concentration for heating. 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 grams of activated carbon were each mixed with 100 ml of Frac-Fluid to create 0%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.3%, 0.4%, 0.5% activated carbon Frac-Fluid solution. The seventh core was microwaved empty for control purposes. Each core was labeled with “I” at the fluid injection side and “D” at the fluid discharge side as shown in

Figure 2.

2.3. CT Scan Testing

A supplementary experiment was performed to measure the effect of salinity on the activated carbon permittivity. Previous studies showed that as the salinity increases the permittivity increases. This is due to the increase in conductivity, as the solution gets more saline. All studies performed previously were limited to different concentrations of saline solution with no activated carbon mixed in. Since the activated carbon is expected to mix with brine in the reservoirs, the experiment performed here involved the effect of saline solutions on the activated carbon permittivity.

Recording the temperature of the cores after they were heated identified the optimum activated carbon concentration. Another testing method used to validate the successful injection of activated carbon was CT scanning the cores. Selected cores; the empty core, the core injected with 0.3% activated carbon Frac-Fluid solution, and the core injected with 0.5% activated carbon Frac-Fluid solution, were scanned using a CT scanner. Each core tested is 2.5 inches in length. The CT scanner used produced 64 cross-sectional images along the vertical axis of the core. All images are equally spaced. Screenshots of the 20th, 40th, and 60th slides of each core were taken. Four dots equally spaced were drawn on each core and two temperature readings were taken for each core as shown in the results.

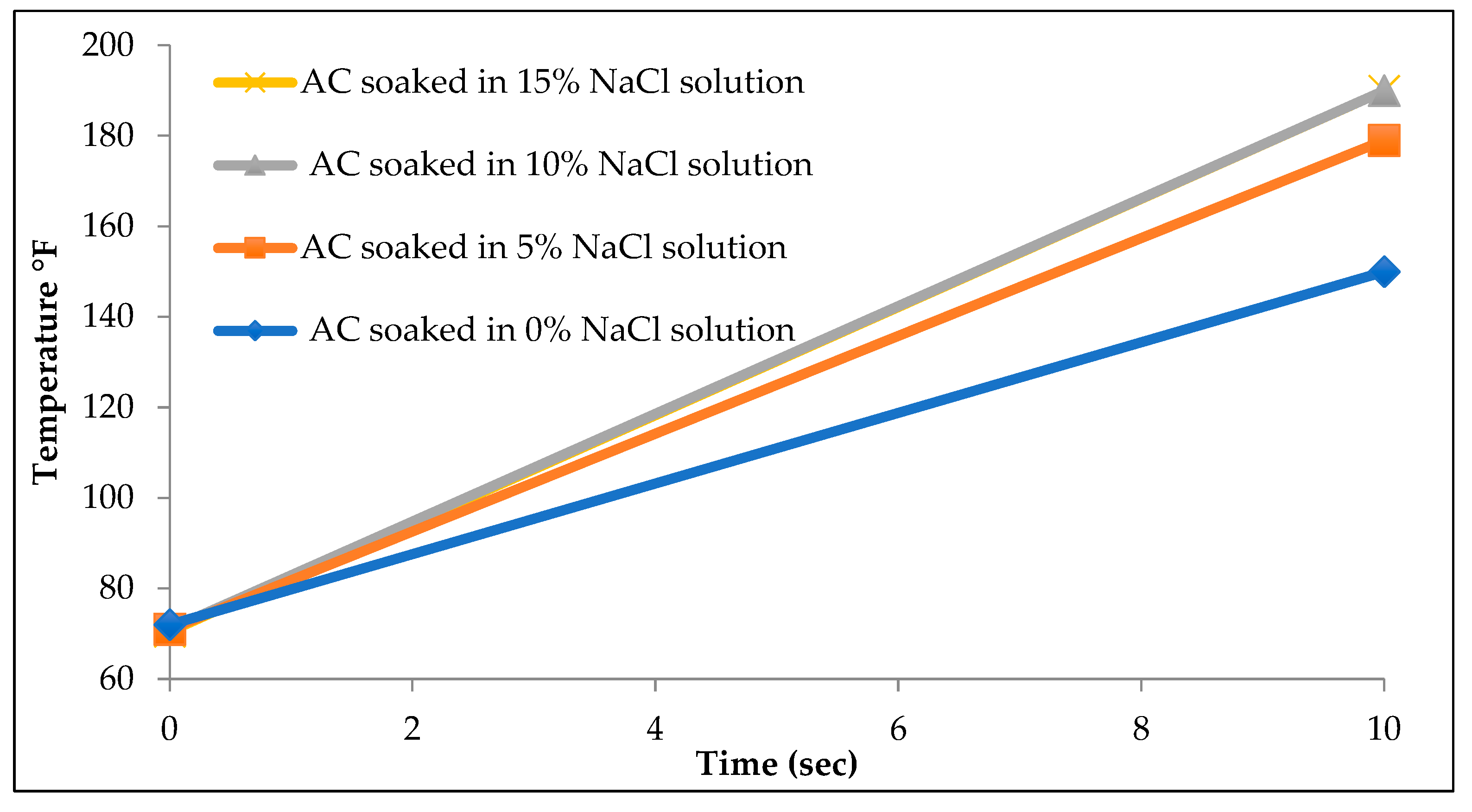

2.4. Effect of Salinity on Microwave heating

Two groups of experiments were performed. In the first set, activated carbon was soaked into four different concentrations of saline solution. Two, four, and six grams of calcium chloride salt were each mixed with 40 ml of water to create 0, 5%, 10%, and 15% calcium chloride solutions. The four samples were heated for 10 seconds and then their temperature was measured using the infrared thermometer. Temperature recordings are a direct measure of permittivity. The setup of the second experiment was similar to the first experiment except that sodium chloride was used this time to prepare the four different concentrations of saline solutions.

3. Results

3.1. Nano-Particle Activated Carbons Injection

Four different cores were tested. The first core was empty (no solution injection), the second was injected with pure distilled water (0% AC), and the third and fourth cores were injected with an aqueous solution of activated carbon at 0.1% and 0.5% respectively.

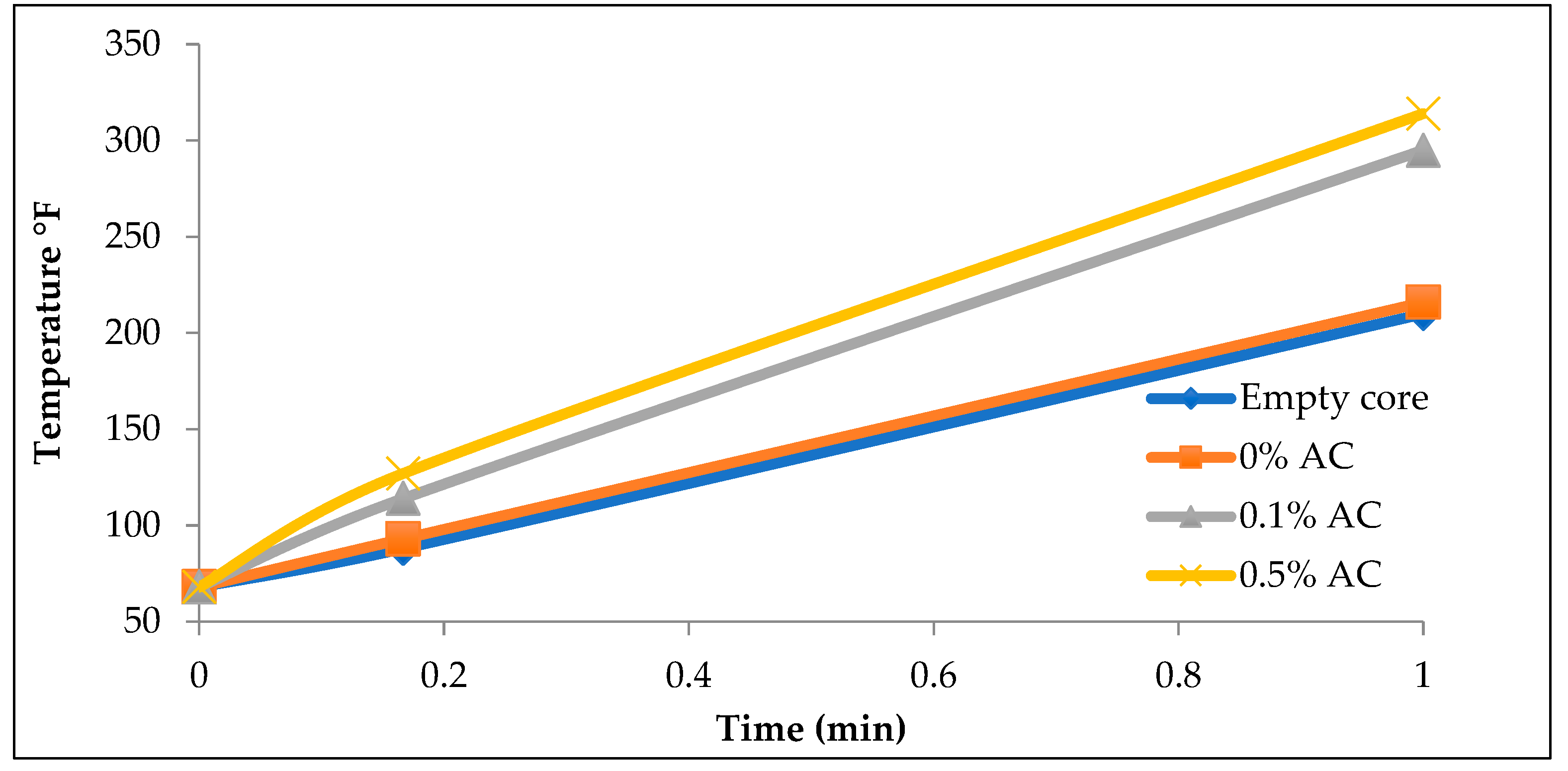

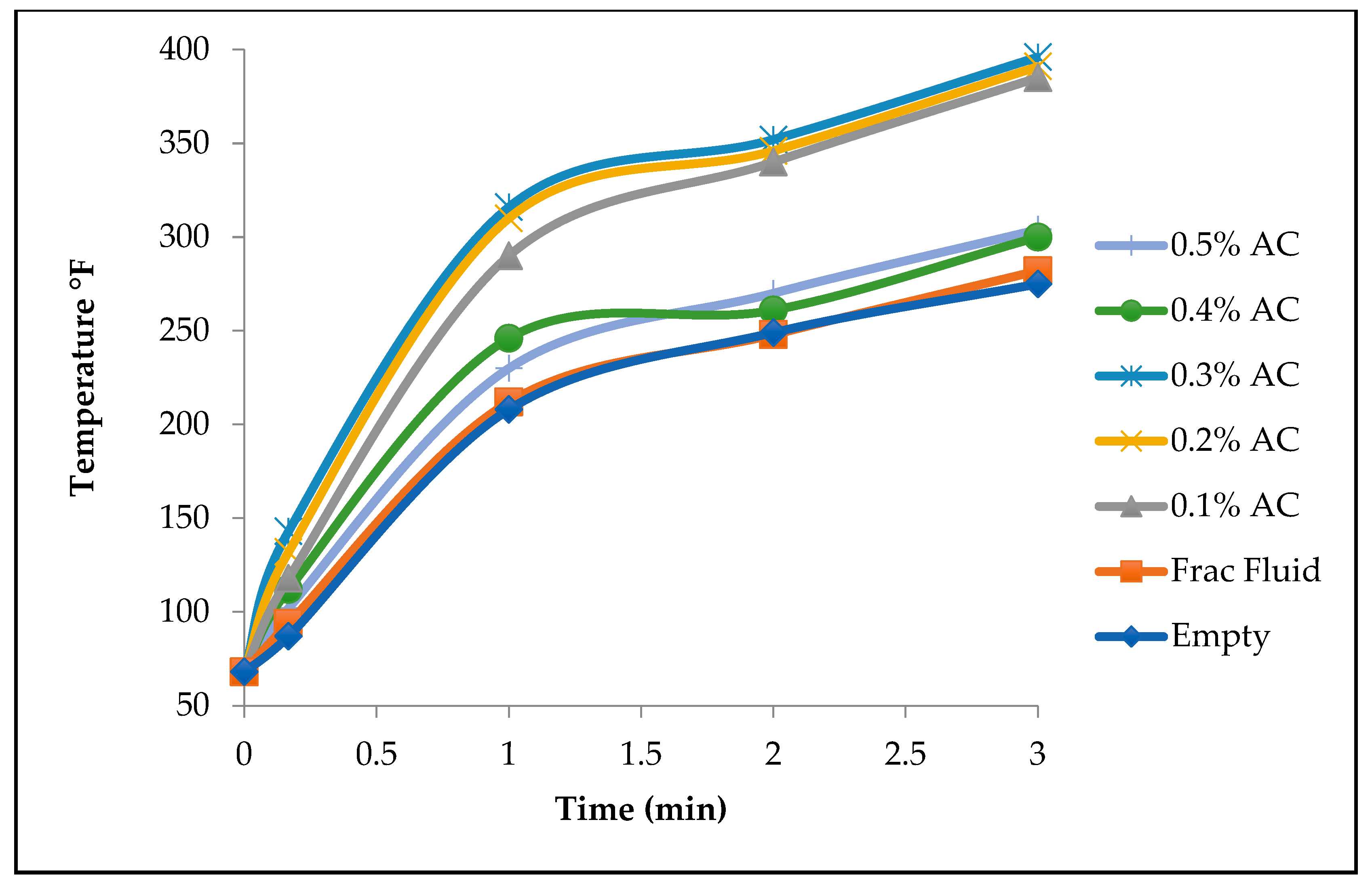

Figure 3 shows the temperature of the cores after exposure to microwave radiation for different durations of time.

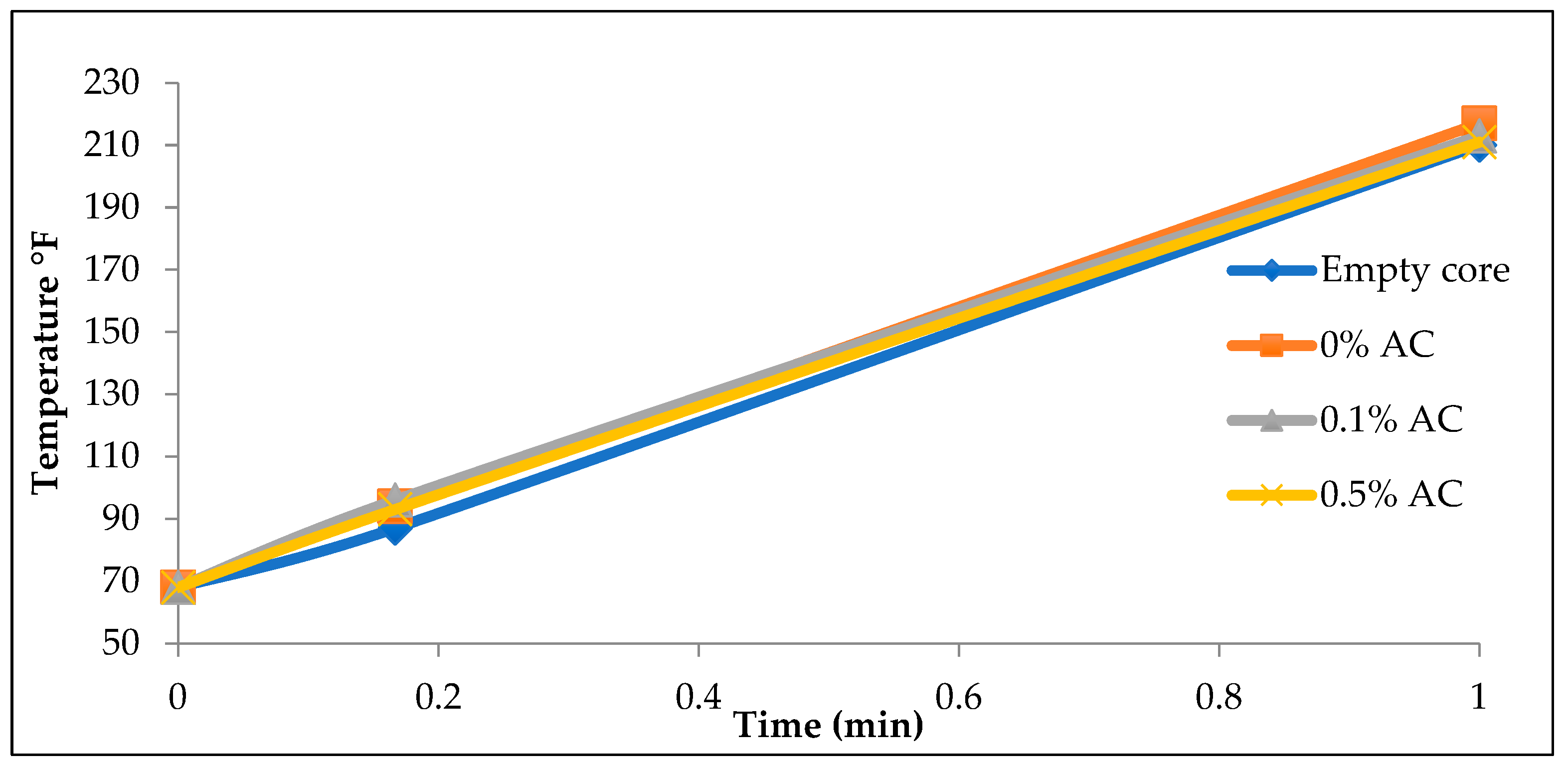

Figure 4 shows the temperature of the cores after exposure to microwave radiation for different durations of time.

3.2. Activated Carbons Concentration Optimization

Table 1 shows the temperature recordings for seven different cores with different activated carbon concentrations.

The process of injecting 0% and 0.1% activated carbon was a smooth process with no sharp increase in inlet pump pressure. Injecting the 0.5% activated carbon was not as smooth, as we experienced a sharp increase in inlet pump pressure during the injection; an indication of blockage. By monitoring the temperatures at the inlet and the discharge of the pump, discrepancies are found in the cases of the 0.4% and 0.5% AC. The results are summarized in

Table 2.

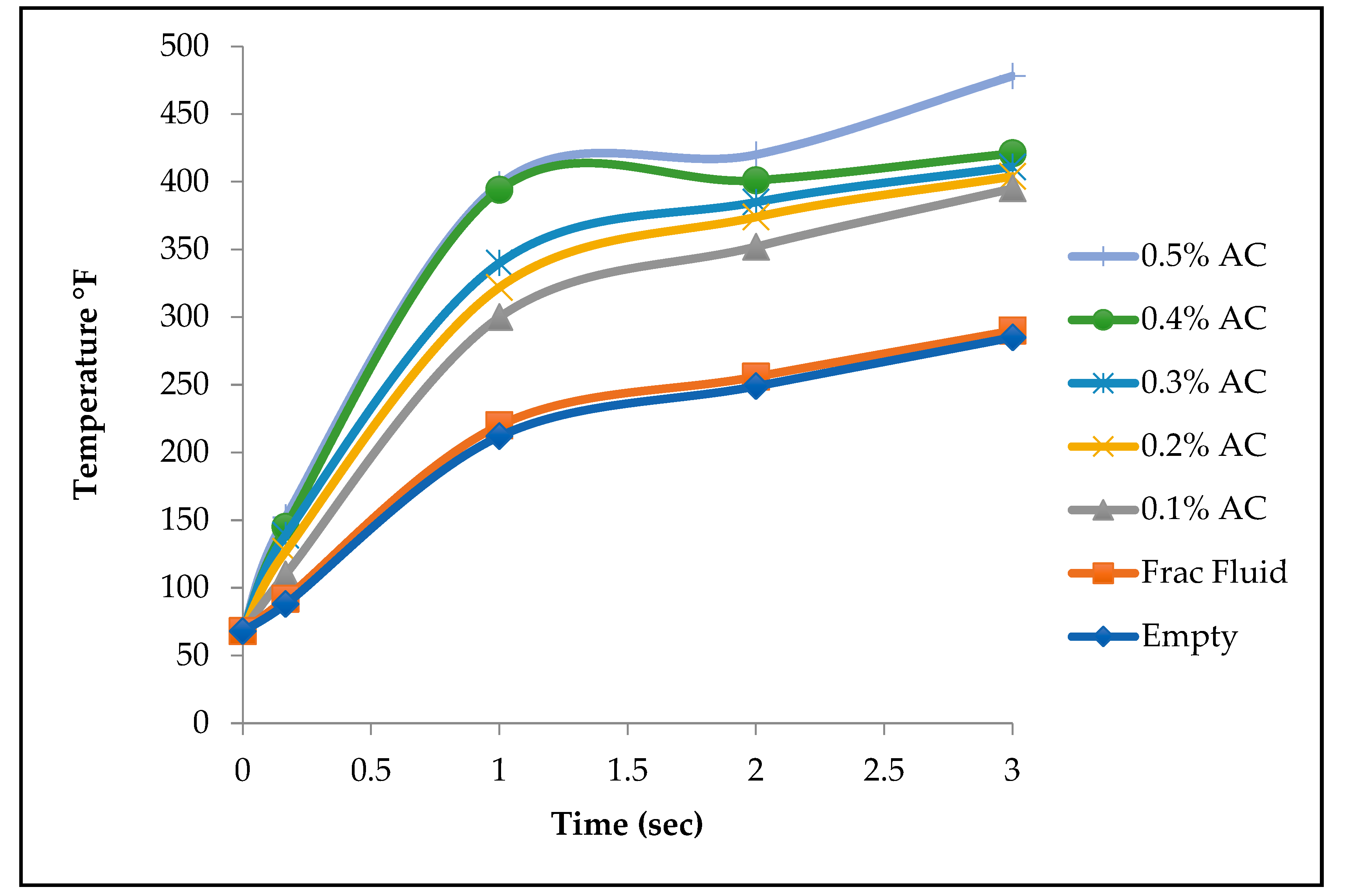

Figure 5 below shows a graph of the injection point temperature recordings of 7 cores with different activated carbon concentrations. The core saturated with 0.5% activated carbon showed the highest temperature recording at the injection side. However, that same core showed the lowest temperature recording at the discharge point as presented in

Figure 6.

3.3. CT Scanning Results

The 20th, 40th, and 60th slides correspond to cross-sectional views of 0.78, 1.57, and 2.34 inches, respectively, into each core.

Figure 7,

Figure 8, and

Figure 9 show a comparison between the three selected cores at various locations inside the cores.

3.4. Effect of Salinity on Microwave Heating

The impact of salinity on microwave heating is demonstrated in

Table 3, highlighting how variations in salt concentration influence the heating efficiency, energy absorption, and temperature distribution within the medium. Sodium chloride displayed similar behavior to calcium chloride as seen in

Figure 10.

4. Discussion

The Nano-Particle Activated Carbon Injection experiments reveal several critical insights into the relationship between activated carbon concentration and thermal performance in core heating. As illustrated in

Figure 3, increasing activated carbon concentrations generally results in higher temperatures during heating, suggesting that higher concentrations can optimize heating. However, the difference in temperature between the 0.1% and 0.5% concentrations is observed to be minimal, potentially due to pore blockages that would occur at higher concentrations. This observation is particularly relevant, as pore blockages could prevent the even distribution of heat throughout the core. To address this, monitoring the inlet and discharge pressures during the injection process could help identify the extent and location of these blockages.

The results shown in

Figure 3 also underscore the effectiveness of fracturing fluids as suspending mediums for activated carbon nanoparticles. Cores injected with fracturing fluids containing activated carbon, particularly at a 0.5% concentration, exhibited notably higher temperatures compared to those with lower activated carbon concentrations or no carbon injection at all. Conversely, using water as a transport medium, as seen in

Figure 4, produced minimal heating effects, demonstrating that water is an ineffective carrier for activated carbon nanoparticles. The majority of the nanoparticles settled before injection, significantly limiting their ability to penetrate the core. This observation reinforces the idea that fracturing fluids are a far more effective transport medium for nano-particles in such experiments.

Further analysis, as shown in

Table 1, provides a clear relationship between activated carbon concentration and temperature until the 0.3% concentration threshold is reached. Beyond this point, temperature readings begin to decline, suggesting that higher concentrations lead to blockages in the pore throats, inhibiting effective heat transfer. This was particularly evident in cores injected with 0.4% and 0.5% solutions, where the accumulation of particles blocked fluid flow and thus reduced the efficiency of heat distribution. These results highlight the need to balance concentration levels to avoid such blockages, which can reduce the thermal benefits of activated carbon injection.

Table 2 adds further nuance to the findings, showing an increasing temperature gap between the injection and discharge sides as the concentration of activated carbon increases. For example, after three minutes of heating, the 0.1% concentration showed a small difference of 10°F between the injection and discharge sides, whereas the 0.5% concentration exhibited a much larger difference of 174°F. This substantial disparity indicates that higher concentrations of activated carbon lead to uneven distribution, causing blockages near the injection side and preventing the nanoparticles from reaching the discharge side. The more uniform heat transfer seen in the 0.1% concentration emphasizes the importance of selecting an optimal concentration to maximize efficiency without creating flow obstructions.

CT scan results, as shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, further support these observations. Higher concentrations, such as 0.5%, led to a sharp spike in temperature near the injection side, where the activated carbon particles accumulated before blocking the pore throats. This blockage prevented the carbon from fully penetrating the core, resulting in lower temperatures at the discharge side. Interestingly, the core injected with 0.3% activated carbon produced the highest average temperature, despite not having the highest injection-side temperature. This suggests that while the 0.5% concentration may initially generate more heat, it leads to premature blockages, whereas the 0.3% concentration allows for a more even distribution of heat throughout the core.

Despite these compelling results, no clear differences were detected between the cores using the standard CT scanner. This is likely due to the low resolution (the highest resolution is 4 microns) of the scanner, which was unable to detect the nanoscale particles and their distribution within the core. The use of micro-CT scanning, which offers higher resolution, would likely provide more detailed insights into the behavior of nanoparticles and their effects on core permeability and heat distribution. Such advanced imaging techniques would help to refine the understanding of how varying concentrations of activated carbon influence core performance, allowing for more precise optimization of the injection process.

In addition to investigating the impact of activated carbon concentrations, the study also examined the effect of salinity on microwave heating. As expected, higher salinity levels increased the permittivity of the solutions, allowing for faster and more efficient heating. The presence of activated carbon did not alter the fundamental behavior of saline solutions in terms of permittivity. However, the results showed that increasing the salinity beyond a 10% sodium chloride solution had no further effect on permittivity.

Table 3 illustrates that while the 10% solution reached 187°F after 10 seconds of heating, the 15% solution recorded only a negligible difference of 2°F. In contrast, the 0% sodium chloride solution recorded a temperature of 147°F, a significant 40°F lower than the 10% solution. These findings confirm that salinity plays a crucial role in enhancing microwave heating efficiency, but only up to a certain concentration threshold.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the complex interplay between activated carbon concentration, pore blockage, and thermal efficiency in core heating. While increasing concentrations of activated carbon can enhance thermal performance, concentrations above 0.3% lead to pore blockages that limit heat transfer. Optimizing the concentration is critical for ensuring even heat distribution without premature blockage. Furthermore, advanced imaging techniques like micro-CT scanning are essential for providing detailed insights into the nanoscale behavior of injected particles, enabling more precise optimization of the injection process. Additionally, the effect of salinity on microwave heating demonstrates that while higher salinity improves heating efficiency, its impact plateaus beyond a certain concentration. Both findings are crucial for optimizing nanoparticle injection processes and improving overall thermal performance in future applications.

This study demonstrated that nano-particles of activated carbon can be successfully injected into sandstone cores. Testing with a commercial frac-fluid showed promising results, as cores injected with activated carbon suspended in this fluid recorded higher temperatures than control cores, confirming the frac-fluid as an effective medium for nanoparticle transport.

The study found that increasing the concentration of activated carbon improves heating; however, excessive concentrations caused pore blockages, leading to injection failure. Therefore, optimizing concentration is critical to avoid flow obstructions while maximizing thermal benefits.

Once the frac-fluid was established as a suitable carrier, the experiment focused on identifying the optimal concentration of activated carbon. For the Berea sandstone cores used in this setup, 0.3% concentration yielded the highest temperature, outperforming both higher and lower concentrations.

The ideal concentration of activated carbon also depends on other factors, including the desired penetration depth, reservoir permeability, pore throat size, pump power, microwave exposure time, microwave power, and the nanoparticle size range. These parameters contribute to achieving optimal thermal enhancement in different formations.

CT scanning was inconclusive due to its 4-micrometer resolution limit, insufficient for observing nanoparticle-scale details. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), with its higher sensitivity to fluids, offers a superior alternative for studying fluid-nanoparticle interactions within porous media. Utilizing magnetic properties of hydrogen nuclei, MRI provides detailed insights into fluid distribution and dynamics, overcoming the resolution limitations of CT. Future studies are recommended to use MRI for clearer visualization of nanoparticle behavior in the core.

Ideal reservoirs for injecting activated carbon nanoparticles are heavy oil reservoirs with high permeability and salinity, which are also economically viable for hydraulic fracturing. The study also explored the impact of salinity on activated carbon’s permittivity, showing that higher salinity levels improve heating efficiency by increasing the permittivity of the activated carbon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. & Y.E. and Y.E.; methodology, A.A. and Y.E..; validation, A.A., Y.E., and M.Y.S.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, A.A., Y.E. and M.Y.S.; resources, M.Y.S.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A. and Y.E.; writing—review and editing, M.A.G. and S.N.; visualization, S.N.; supervision, M.Y.S.; project administration, M.Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Soliman, M.Y. Approximate solutions for flow of oil heated using microwaves. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 1997, 18, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.K. Process for Enhanced Production of Heavy Oil using Microwaves. US Patent 7,975,763 B2, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, H.A.; Soliman, M.Y. Combining microwave and activated carbon for oilfield applications: Thermal-Electromagnetic analysis of activated carbon. In Proceedings of the SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition, Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia, 24–27 April 2017; SPE-188130-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naufel, R.; De Sa, C.H.M.; Panisset, C.M.D.V.; Martins, A.L.; Ataide, C.H.; Pereira, M.; Barrozo, M. Microwave Drying of Drilled Cuttings. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 29–31 October 2013; OTC-24377-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, B.; Akin, S.; Acar, C.; Hascakir, B. Microwave assisted gravity drainage of heavy oils. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3–5 December 2008; IPTC-12536-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, J.E.; Wheeler, R.R. Jr. Microwave permittivity and dielectric relaxation of a high surface area activated carbon. Appl. Phys. A 2004, 79, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, H.A. Using Microwave to Produce Heavy Oil Reservoirs: Experimental and Numerical Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Renouf, G.; Scoular, R.J.; Soveran, D. Treating heavy slop oil with variable frequency microwaves. In Proceedings of the PETSOC Canadian International Petroleum Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 10–12 June 2003; PETSOC-2003-020-EA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogolo, N.A.; Olafuyi, O.A.; Onyekonwu, M.O. Enhanced oil recovery using nanoparticles. In Proceedings of the SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition, Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia, 8–11 April 2012; SPE-160847-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, R.P.; Uthe, M.T. Hydrocarbon remediation using microwaves. In Proceedings of the SPE Health, Safety, Security, San Antonio, TX, USA, 26–28 February 2001; SPE-66519-MS., Environment and Social Responsibility Conference—North America. [CrossRef]

- Okassa, F.; Godi, A.; Simoni, M.D.; Matteo, M.; Misenta, M.; Maddinelli, G. A non-conventional EOR technology using RF/MW heating coupled with a new patented well/reservoir interface. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Florence, Italy, 19–22 September 2010; SPE-134324-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).