Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

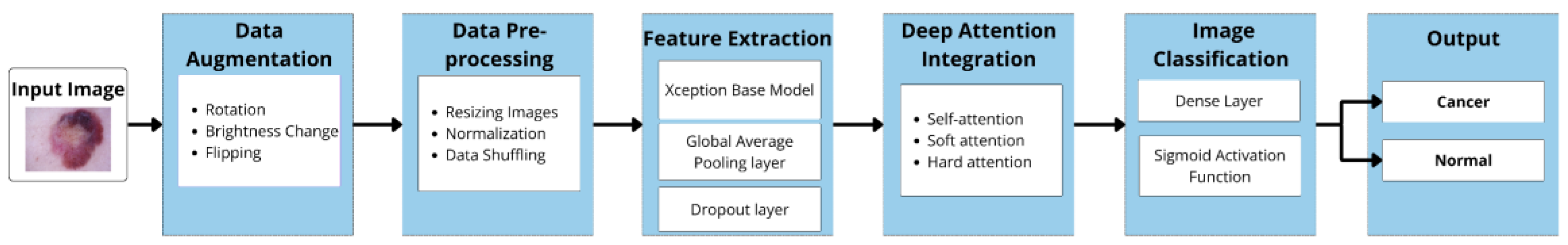

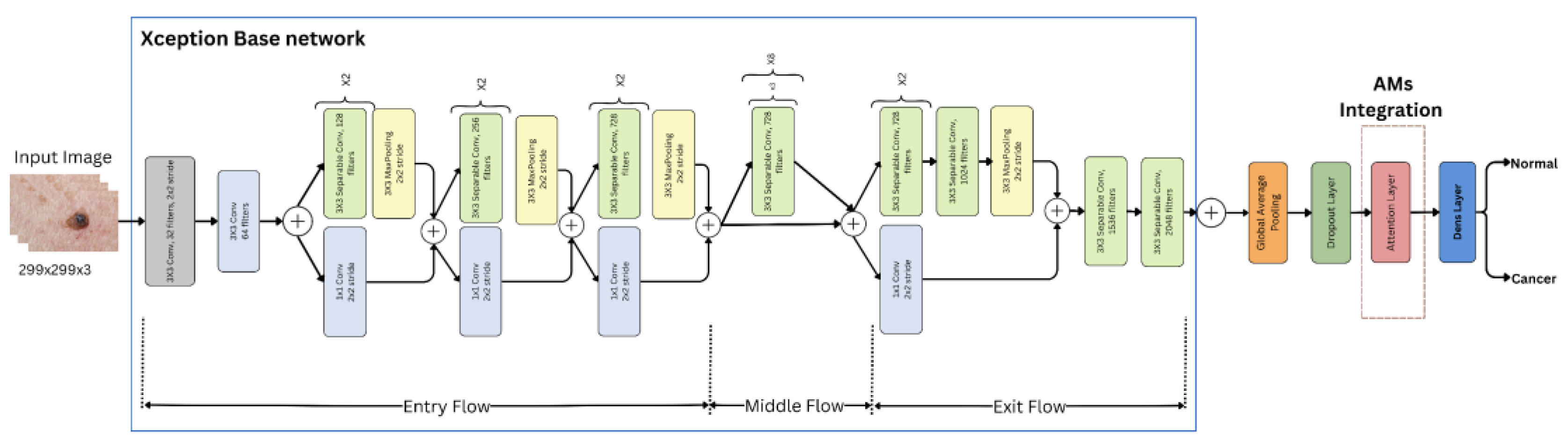

Early and accurate diagnosis of skin cancer improves survival rates; however, dermatologists often struggle with lesion detection due to similar pigmentation. Deep learning and transfer learning models have shown promise in diagnosing skin cancers through image processing. Integrating Attention Mechanisms (AMs) with deep learning have further enhanced the accuracy of medical image classification. While significant progress has been made, further research is needed to im-prove detection accuracy. Previous studies have not explored the integration of attention mechanisms with the pre-trained Xception transfer learning model for binary classification of skin cancer. This study investigates the impact of various attention mechanisms on the Xception model's performance in detecting benign and malignant skin lesions. Using the HAM10000 dermatoscopic image dataset, four experiments were conducted. Three models incorporated self-attention (SL), hard-attention (HD), and soft-attention (SF), respectively, while the fourth model used standard Xception without AMs. Results demonstrated the effectiveness of AMs, with models incorporating self, soft, and hard attention mechanisms achieving accuracies of 94.11%, 93.29%, and 92.97%, respectively, compared to 91.05% for the baseline model, representing a 3% improvement. Both self-attention and soft-attention models outperformed previous studies on recall metrics, which are crucial for medical investigations. These findings suggest that AMs can enhance performance on complex medical imaging tasks, potentially supporting earlier diagnosis and improving treatment outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Proposal of a novel model based on the Xception architecture that incorporates various AMs for binary classification of skin lesions as benign or malignant.

- A thorough investigation of how different AMs impact the Xception model's performance.

- Comparison of the proposed models with recent state-of-the-art skin cancer detection methods in binary classification, using the same dataset.

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

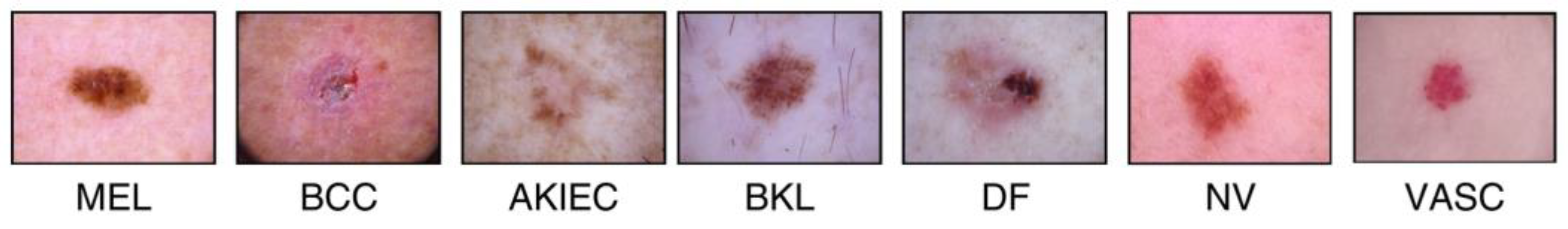

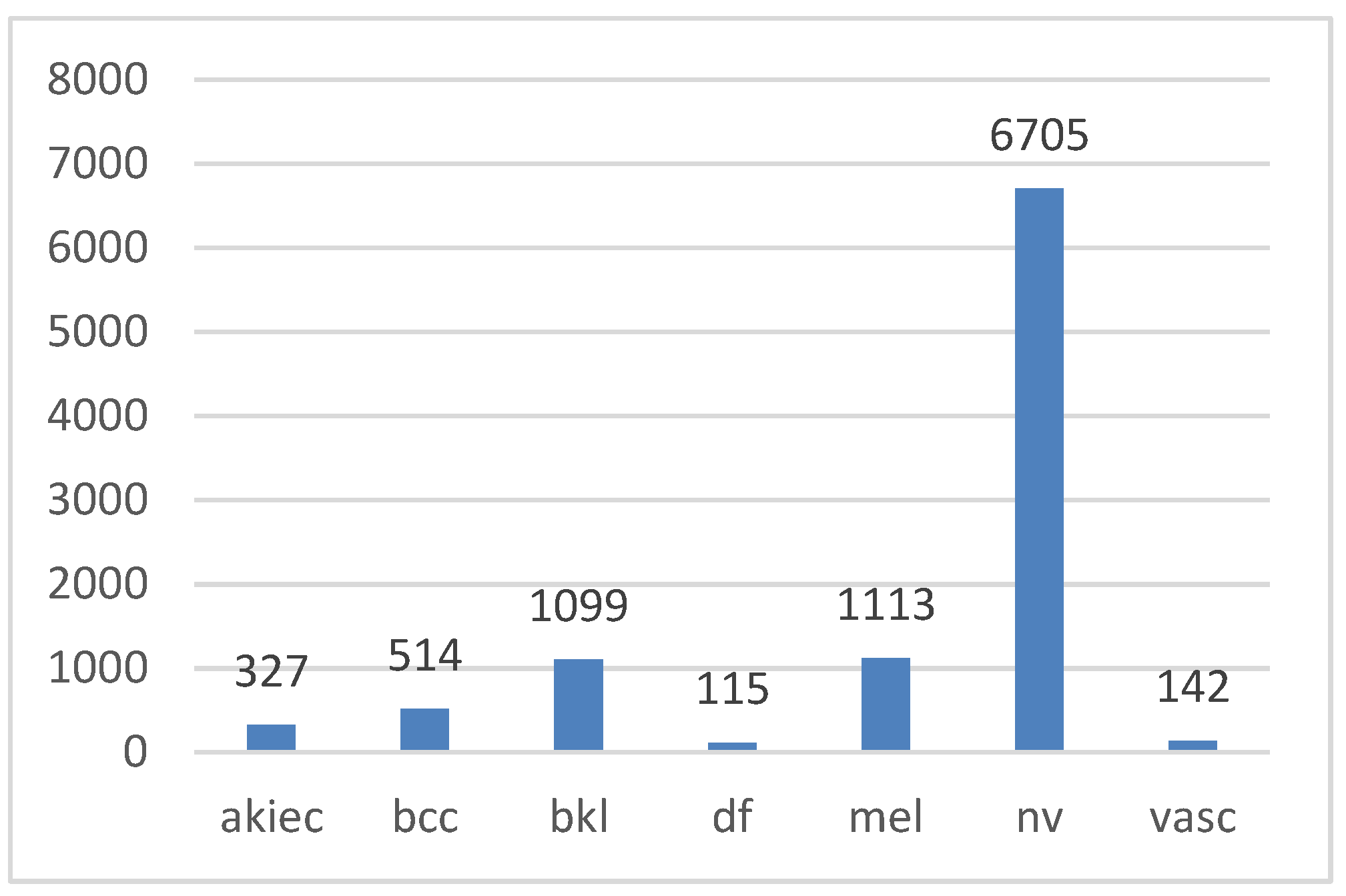

3.1. Dataset

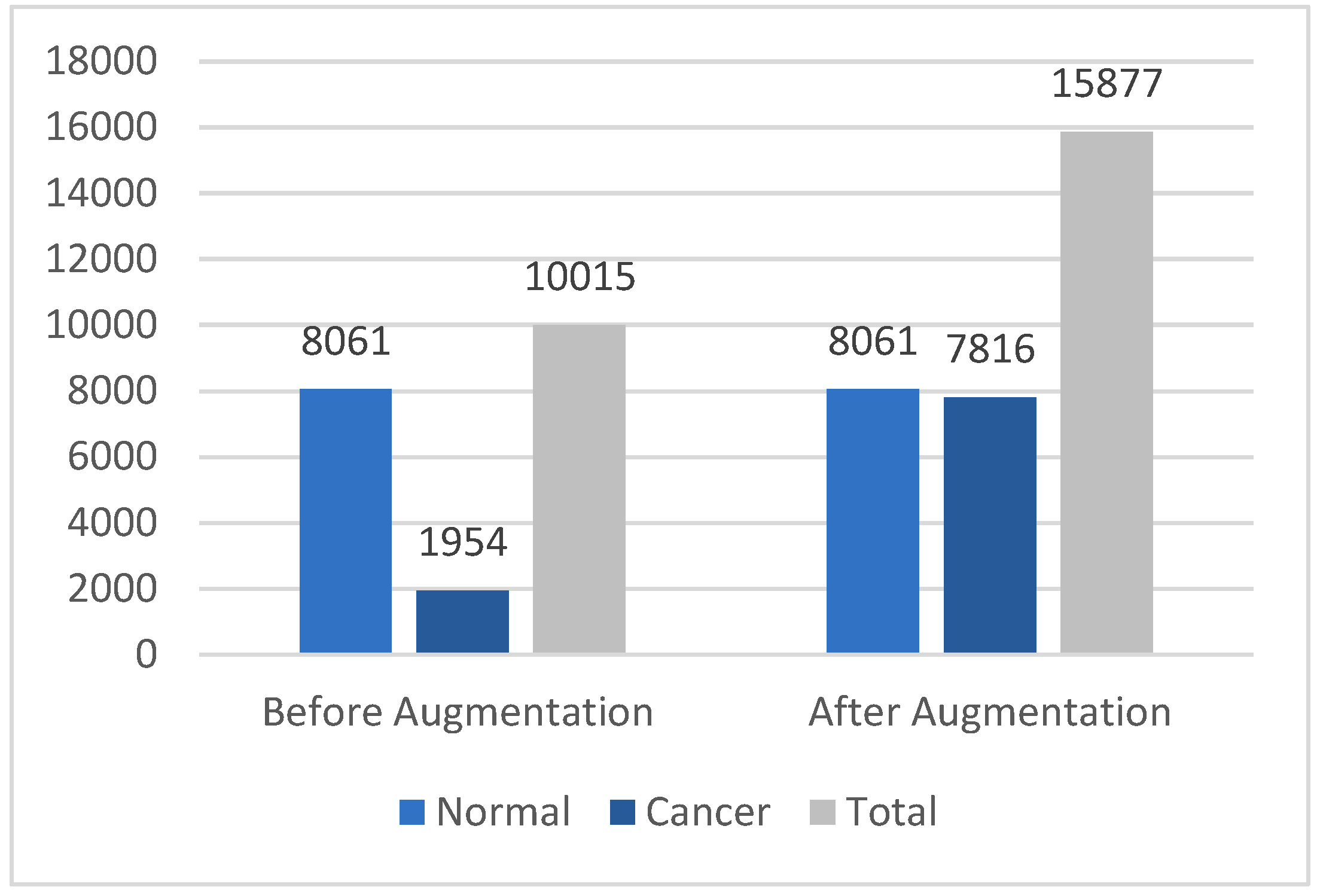

3.2. Data Augmentation

3.3. Data Preprocessing

3.4. Feature Extraction with Pre-Trained Xception Models

3.5. Deep Attention Integration

- 1.

- SL layer: This layer transformed the input into query (Q), key (K), and value (V) vectors through linear transformations. Attention scores were computed as the dot product of the query with all keys divided by . These scores were then normalized using Softmax to obtain attention weights for the values [42]. In this project, self-attention was internally implemented using Keras's built-in attention layer [43], following this equation:

- 2.

-

SF layer: This layer discredited irrelevant areas of the image by multiplying the corresponding feature maps with low weights. The low attention areas had weights closer to 0, allowing the model to focus on the most relevant information, which enhanced performance [12]. A dense layer was used with softmax activation to compute attention weights for each feature , where Softmax ensured that these weights sum to 1, as shown in the following equation [44]:These attention weights were then applied to the feature map x. using a dot product operation

- 3.

- HD layer: This layer compelled the model to focus exclusively on crucial elements, disregarding all others. The weight assigned was either 0 or 1 for each input component. This applied a binary mask to the attention scores between queries Q and keys K. The mechanism assigned a value of 1 to the top k highest-scoring elements (selected by TopK), and 0 to the rest [45]. This forced the model to focus only on the most important elements, disregarding others, without involving gradients in the selection process. The process is represented by the following equation:

3.6. Image Classification

3.6.1. Dense (Fully Connected) Layer

3.6.2. Sigmoid Layer

3.6.3. Classification Layer

3.7. Model Evaluation

3.7.1. Classification Accuracy

3.7.2. Recall

3.7.4. F1 Score

3.7.5. False Alarm Rate (FAR)

3.7.6. Cohen’s kappa

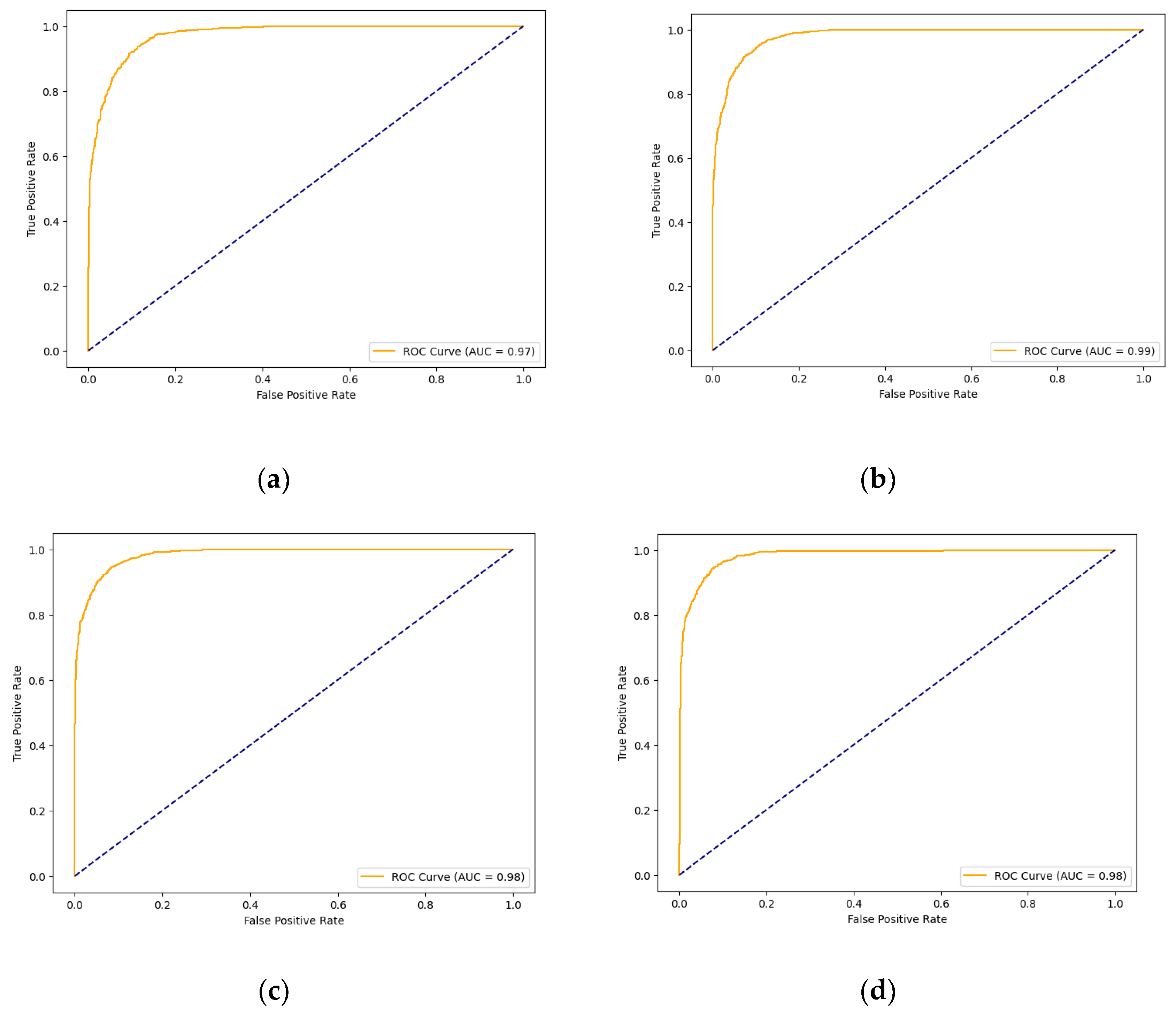

3.7.7. AUC Score and ROC Curve

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.2. Classification Results

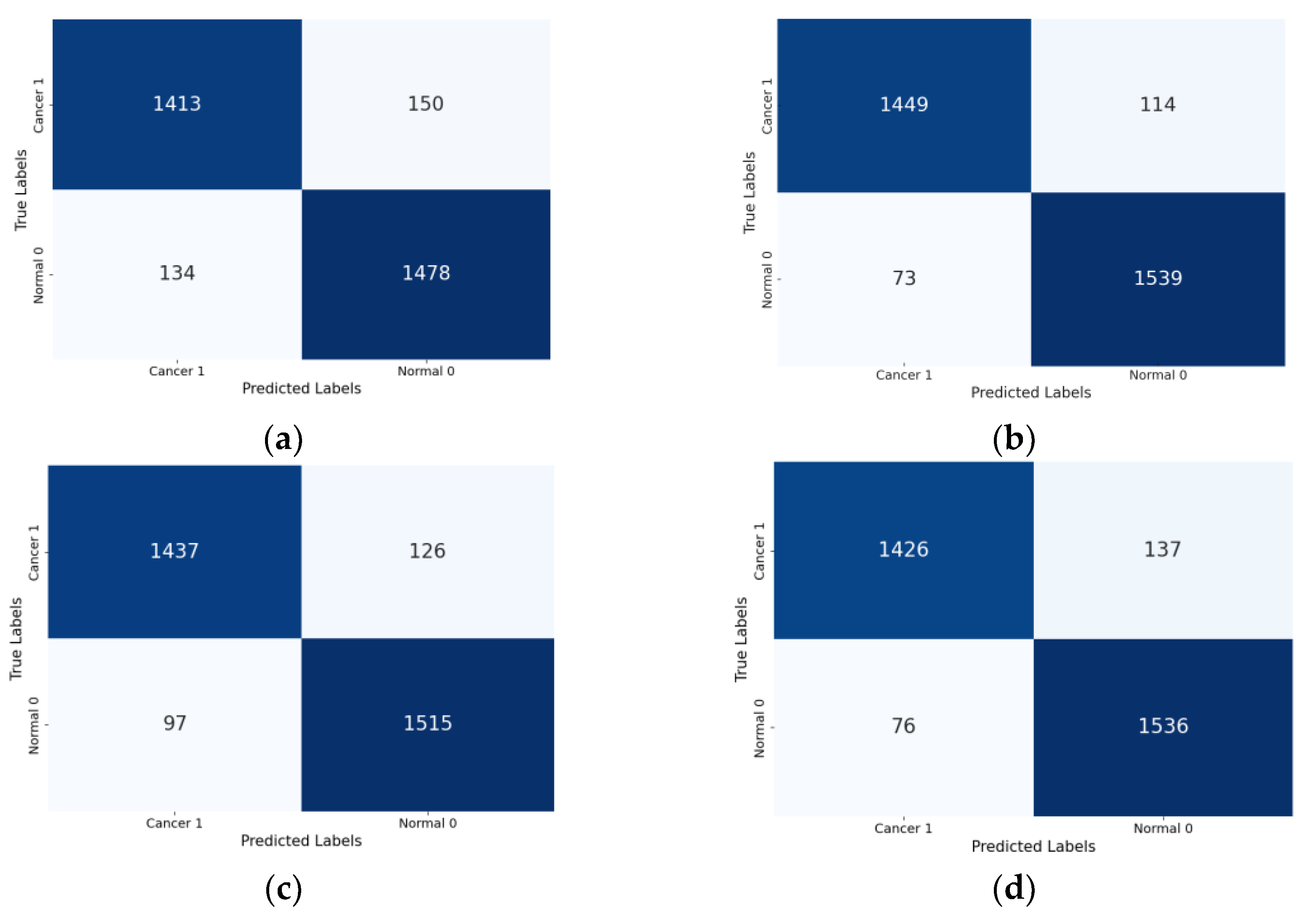

| Models | Accuracy (%) | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | F1-Score (%) | AUC | Cohen’s Kappa |

| Xception (Base) | 91.05% | 91.68% | 90.78% | 91.23% | 0.972 | 0.821 |

| Xception-SL | 94.11% | 95.47% | 93.10% | 94.27% | 0.987 | 0.882 |

| Xception-SF | 93.29% | 95.28% | 91.81% | 93.51% | 0.983 | 0.865 |

| Xception-HD | 92.97% | 93.98% | 92.32% | 93.14% | 0.983 | 0.859 |

4.3. Comparison with Other Models

| Ref/Year | Dataset Relabeling Method | Approach | Precision | Recall | Accuracy | F1-Score | AUC |

| [30] 2023 | Benign= 8,388Malignant= 1,627 | EfficientNetV2-M and EfficientNet-B4 | 95.95% | 94% | 83% | 88% | 0.980 |

| [11] 2024 | Benign= 8,061Malignant= 1,954 | Modified DenseNet-169 with CoAM+ Customized CNN | 93.2% | 91.4% | 95.3% | 93.3% | - |

| Our Proposed Models | Normal= 8,061Cancer= 1,954 | Xception (Base) | 91.05% | 91.68% | 90.78% | 91.23% | 0.972 |

| Xception-SL | 94.11% | 95.47% | 93.10% | 94.27% | 0.987 | ||

| Xception-SF | 93.29% | 95.28% | 91.81% | 93.51% | 0.983 | ||

| Xception-HD | 92.97% | 93.98% | 92.32% | 93.14% | 0.983 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.S.; Amend, S.R.; Austin, R.H.; Gatenby, R.A.; Hammarlund, E.U.; Pienta, K.J. Updating the Definition of Cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2023, 21, 1142–1147, doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-23-0411. [CrossRef]

- Rovenstine, R. Skin Cancer Statistics 2023. The Checkup 2022.

- Razmjooy, N.; Ashourian, M.; Karimifard, M.; Estrela, V.V.; Loschi, H.J.; Nascimento, D. do; França, R.P.; Vishnevski, M. Computer-Aided Diagnosis of Skin Cancer: A Review. Current Medical Imaging 16, 781–793.

- Al-Dawsari, N.A.; Amra, N. Pattern of Skin Cancer among Saudi Patients Attending a Tertiary Care Center in Dhahran, Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. A 20-Year Retrospective Study. International Journal of Dermatology 2016, 55, 1396–1401, doi:10.1111/ijd.13320. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.H.; Mir, M.; Qian, L.; Baloch, M.; Ali Khan, M.F.; Rehman, A.-; Ngowi, E.E.; Wu, D.-D.; Ji, X.-Y. Skin Cancer Biology and Barriers to Treatment: Recent Applications of Polymeric Micro/Nanostructures. Journal of Advanced Research 2022, 36, 223–247, doi:10.1016/j.jare.2021.06.014. [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Román, M.; Padilla-Gutiérrez, J.R.; Valle, Y.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Valdés-Alvarado, E. Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: A Genetic Update and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 2371, doi:10.3390/cancers14102371. [CrossRef]

- PhD, J.N. Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer Deaths Exceed Melanoma Deaths Globally Available online: https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/home/cancer-topics/skin-cancer/non-melanoma-skin-cancer-deaths-exceed-melanoma-deaths-globally/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Why Is Early Cancer Diagnosis Important? Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/https%3A//www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/spot-cancer-early/why-is-early-diagnosis-important (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Kato, J.; Horimoto, K.; Sato, S.; Minowa, T.; Uhara, H. Dermoscopy of Melanoma and Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers. Front. Med. 2019, 6, doi:10.3389/fmed.2019.00180. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Koban, K.C.; Schenck, T.L.; Giunta, R.E.; Li, Q.; Sun, Y. Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology Image Analysis: Current Developments and Future Trends. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 6826, doi:10.3390/jcm11226826. [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, K.; Thayumanaswamy, I.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Won, D.; Lingaswamy, S. Integration of Localized, Contextual, and Hierarchical Features in Deep Learning for Improved Skin Lesion Classification. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1338, doi:10.3390/diagnostics14131338. [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.K.; Shaikh, M.A.; Srihari, S.N.; Gao, M. Soft-Attention Improves Skin Cancer Classification Performance 2021.

- Jones, O.T.; Matin, R.N.; van der Schaar, M.; Prathivadi Bhayankaram, K.; Ranmuthu, C.K.I.; Islam, M.S.; Behiyat, D.; Boscott, R.; Calanzani, N.; Emery, J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Algorithms for Early Detection of Skin Cancer in Community and Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Lancet Digit Health 2022, 4, e466–e476, doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00023-1. [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V. Attention Cost-Sensitive Deep Learning-Based Approach for Skin Cancer Detection and Classification. Cancers 2022, 14, 5872, doi:10.3390/cancers14235872. [CrossRef]

- Arshed, M.A.; Mumtaz, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Ahmed, S.; Tahir, M.; Shafi, M. Multi-Class Skin Cancer Classification Using Vision Transformer Networks and Convolutional Neural Network-Based Pre-Trained Models. Information 2023, 14, 415, doi:10.3390/info14070415. [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, S.B.; Patil, H.Y. Skin Cancer Classification Framework Using Enhanced Super Resolution Generative Adversarial Network and Custom Convolutional Neural Network. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1210, doi:10.3390/app13021210. [CrossRef]

- Mridha, K.; Uddin, Md.M.; Shin, J.; Khadka, S.; Mridha, M.F. An Interpretable Skin Cancer Classification Using Optimized Convolutional Neural Network for a Smart Healthcare System. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 41003–41018, doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3269694. [CrossRef]

- Shapna Akter, M.; Shahriar, H.; Sneha, S.; Cuzzocrea, A. Multi-Class Skin Cancer Classification Architecture Based on Deep Convolutional Neural Network. arXiv e-prints 2023.

- Kekal, H.P.; Saputri, D.U.E. Optimization of Melanoma Skin Cancer Detection with the Convolutional Neural Network. Journal Medical Informatics Technology 2023, 23–28, doi:10.37034/medinftech.v1i1.5. [CrossRef]

- Nour, A.; Boufama, B. Convolutional Neural Network Strategy for Skin Cancer Lesions Classifications and Detections. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 11th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, November 24 2020; pp. 1–9.

- Nawaz, M.; Mehmood, Z.; Nazir, T.; Naqvi, R.A.; Rehman, A.; Iqbal, M.; Saba, T. Skin Cancer Detection from Dermoscopic Images Using Deep Learning and Fuzzy K-Means Clustering. Microscopy Research and Technique 2022, 85, 339–351, doi:10.1002/jemt.23908. [CrossRef]

- Alabdulkreem, E.; Elmannai, H.; Saad, A.; Kamil, I.; Elaraby, A. Deep Learning-Based Classification of Melanoma and Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer. Traitement du Signal 2024, 41, 213–223, doi:10.18280/ts.410117. [CrossRef]

- G, R.; Ayothi, S. An Efficient Skin Cancer Detection and Classification Using Improved Adaboost Aphid–Ant Mutualism Model. International Journal of Imaging Systems and Technology 2023, 33, n/a-n/a, doi:10.1002/ima.22932. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, J.; Ishfaq, M.; Ali, G.; Saeed, M.R.; Hussain, M.; Alkhalifah, T.; Alturise, F.; Samand, N. Skin Cancer Disease Detection Using Transfer Learning Technique. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5714, doi:10.3390/app12115714. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Anees, T.; Fiza, M.; Naqvi, R.A.; Lee, S.-W. SCDNet: A Deep Learning-Based Framework for the Multiclassification of Skin Cancer Using Dermoscopy Images. Sensors 2022, 22, 5652, doi:10.3390/s22155652. [CrossRef]

- Alabduljabbar, R.; Alshamlan, H. Intelligent Multiclass Skin Cancer Detection Using Convolution Neural Networks. Computers, Materials & Continua 2021, 69, 831–847, doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.018402. [CrossRef]

- Imran, A.; Nasir, A.; Bilal, M.; Sun, G.; Alzahrani, A.; Almuhaimeed, A. Skin Cancer Detection Using Combined Decision of Deep Learners. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 118198–118212, doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3220329. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, R.; Afzal, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Gul, S.; Baber, J.; Bakhtyar, M.; Mehmood, I.; Song, O.-Y.; Maqsood, M. Region-of-Interest Based Transfer Learning Assisted Framework for Skin Cancer Detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 147858–147871, doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3014701. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Singhania, U.; Tripathy, B.; Nasr, E.A.; Aboudaif, M.K.; Kamrani, A.K. Deep Learning-Based Transfer Learning for Classification of Skin Cancer. Sensors 2021, 21, 8142, doi:10.3390/s21238142. [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V.; Raj, N.I.; Nath, M.K.; Stephen, N. A Deep Neural Network Using Modified EfficientNet for Skin Cancer Detection in Dermoscopic Images. Decision Analytics Journal 2023, 8, 100278, doi:10.1016/j.dajour.2023.100278. [CrossRef]

- Di̇mi̇li̇ler, K.; Sekeroglu, B. Skin Lesion Classification Using CNN-Based Transfer Learning Model. Gazi University Journal of Science 2023, 36, 660–673, doi:10.35378/gujs.1063289. [CrossRef]

- A Comparative Study of Neural Network Architectures for Lesion Segmentation and Melanoma Detection Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9230969 (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Bansal, P.; Garg, R.; Soni, P. Detection of Melanoma in Dermoscopic Images by Integrating Features Extracted Using Handcrafted and Deep Learning Models. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2022, 168, 108060, doi:10.1016/j.cie.2022.108060. [CrossRef]

- Parmonangan, I.H.; Marsella, M.; Pardede, D.F.R.; Rijanto, K.P.; Stephanie, S.; Kesuma, K.A.C.; Cahyaningtyas, V.T.; Anggreainy, M.S. Training CNN-Based Model on Low Resource Hardware and Small Dataset for Early Prediction of Melanoma from Skin Lesion Images. Engineering, MAthematics and Computer Science Journal (EMACS) 2023, 5, 41–46, doi:10.21512/emacsjournal.v5i2.9904. [CrossRef]

- Alhudhaif, A.; Almaslukh, B.; Aseeri, A.O.; Guler, O.; Polat, K. A Novel Nonlinear Automated Multi-Class Skin Lesion Detection System Using Soft-Attention Based Convolutional Neural Networks. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2023, 170, 113409, doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2023.113409. [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.; AlSaeed, D. Breast Cancer Detection in Thermography Using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) with Deep Attention Mechanisms. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12922, doi:10.3390/app122412922. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Wu, S.; Shi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhuang, H.; Fu, E. An Investigation of a Multidimensional CNN Combined with an Attention Mechanism Model to Resolve Small-Sample Problems in Hyperspectral Image Classification. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 785, doi:10.3390/rs14030785. [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Gupta, S.; Altameem, A.; Nayak, S.R.; Poonia, R.C.; Saudagar, A.K.J. An Enhanced Transfer Learning Based Classification for Diagnosis of Skin Cancer. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1628, doi:10.3390/diagnostics12071628. [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 Dataset, a Large Collection of Multi-Source Dermatoscopic Images of Common Pigmented Skin Lesions. Sci Data 2018, 5, 180161, doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.161. [CrossRef]

- Codella, N.C.F.; Gutman, D.; Celebi, M.E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.A.; Dusza, S.W.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Mishra, N.; Kittler, H.; et al. Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection: A Challenge at the 2017 International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) 2018.

- ISIC | International Skin Imaging Collaboration Available online: https://www.isic-archive.com (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need 2023.

- Tf.Keras.Layers.Attention | TensorFlow v2.16.1 Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/api_docs/python/tf/keras/layers/Attention (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- “Soft & Hard Attention” Available online: https://jhui.github.io/2017/03/15/Soft-and-hard-attention/ (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Papadopoulos, A.; Korus, P.; Memon, N. Hard-Attention for Scalable Image Classification 2021.

- Hicks, S.A.; Strümke, I.; Thambawita, V.; Hammou, M.; Riegler, M.A.; Halvorsen, P.; Parasa, S. On Evaluation Metrics for Medical Applications of Artificial Intelligence. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5979, doi:10.1038/s41598-022-09954-8. [CrossRef]

| Ref | Approaches | Dataset | Classification Type | Evaluation metrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | Accuracy | F1-Score | ||||

| [20] | CNN | HAM1-ISIC 2017 | multi-class | NA | NA | 78% | NA |

| [16] | CNN | HAM | multi-class | NA | NA | 98.89% | NA |

| [21] | RCNN-FKM | ISIC-2016 ISIC-2017 PH2 |

Binary | NA | 97.2% | 96.1% | NA |

| [23] | Adaboost + IAB-AAM + AlexNet | HAM | Binary | 95.4% | 94.8% | 95.7% | 95% |

| [22] | LWCNN | HAM | Binary | NA | NA | 91.05% | NA |

| [25] | CNN-VGG16 | ISIC 2019 | Multi-class | 92.19% | 92.18% | 96.91%, | 92.18% |

| [28] | Pre-trained CNN model AlexNet + ROI | DermIS DermQuet |

Binary | NA | NA | 97.9% | NA |

| [24] | MobileNetV2 | ISIC-2020 | Binary | 98.3% | 98.1% | 98.20% | 98.1% |

| [31] | Pre-trained CNN | PAD-UFES-20 | Binary/ multi-class | B=88% M=90% |

B=81% M=83% |

B=86% M =NA |

B=NA M =86% |

| [38] | Modified VGG16 architecture | Kaggle | Binary | NA | NA | 89.09% | 93.0% |

| [27] | CNN-VGGNet, CapsNet, and ResNet | ISIC | multi-class | 94% | NA | 93.5% | 92.0% |

| [26] | CNN- ResNet, InceptionV3 | ISBI 2016ISBI 2017Ham | Multi-class | 95.30% | NA | 95.89% | 94.90% |

| [33] | HC + ResNet50V2 and EfficientNet | HAM and PH2 | Binary | 92.8% | 97.5% | 98% | 95% |

| [30] | EfficientNet V2-M and EfficientNet-B4 | ISIC 2020, ISIC 2019HAM | Multi-class / Binary | B=96% M=96% |

B=95% M=95% |

B= 97.06% M=95% |

B=95% M=95% |

| Ref | Approaches | Dataset | Classification Type | Evaluation metrics | |||

| Precision | Precision | Precision | Precision | ||||

| [29] | Six transfer learning networks | HAM | Multi-class | 88.76% | 89.57% | 90.48%, | 89.02% |

| [32] | Four pretrained + image segmentation | Ham | Binary | NA | 94.16% | 96.10% | 96.02% |

| [34] | MobileNetV2, EfficientNetV2+ DenseNet121 + CNN | Ham | Binary | 93.77% | 89.78% | 93.77% | 93.51% |

| [35] | CNNs +Soft attention | Ham | Multi-class | NA | NA | 95.94 % | NA |

| [12] | Six pre-trained models+ Soft attention | HAM and ISIC 2017 | Multi-class | 93.7% | NA | 93.4% | NA |

| [11] | Densenet-169 with CoAM + customized CNN | HAM | Binary | 95.3% | 91.4% | 93.2% | 93.3% |

| Cancer | Total | Normal | Total | |||||

| MEL | BCC | AKIEC | 1954 (19.56%) | DF | BKL | NV | VASC | 8,061 (80.49%) |

| 1113 | 514 | 327 | 115 | 1099 | 6705 | 142 | ||

| Parameters | Values | Description |

| Rotation range | 40 | Randomly rotate images within a range of 40 degrees |

| Brightness range | [1.0,1.3] | Adjust brightness 1.0-1.3 times original |

| Horizontal flip | True | Flipping the Image horizontally |

| Vertical flip | True | Flipping the Image Vertically |

| Dataset Size | Training Sets | Testing Sets |

| 15,877 | 12,702 | 3,175 |

| Parameter | With AMs | Without AMs |

| Epochs | 50 | 50 |

| Dropout | 0.7 | Not Used |

| Shuffle | True | True |

| Activation function | Sigmoid/Softmax | Sigmoid |

| L2 Regularization | 0.001 | Not Used |

| Loss-Function | binary-cross-entropy | binary-cross-entropy |

| Probability Threshold | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Optimizer | Adam | Adam |

| Learning rate | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).