Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

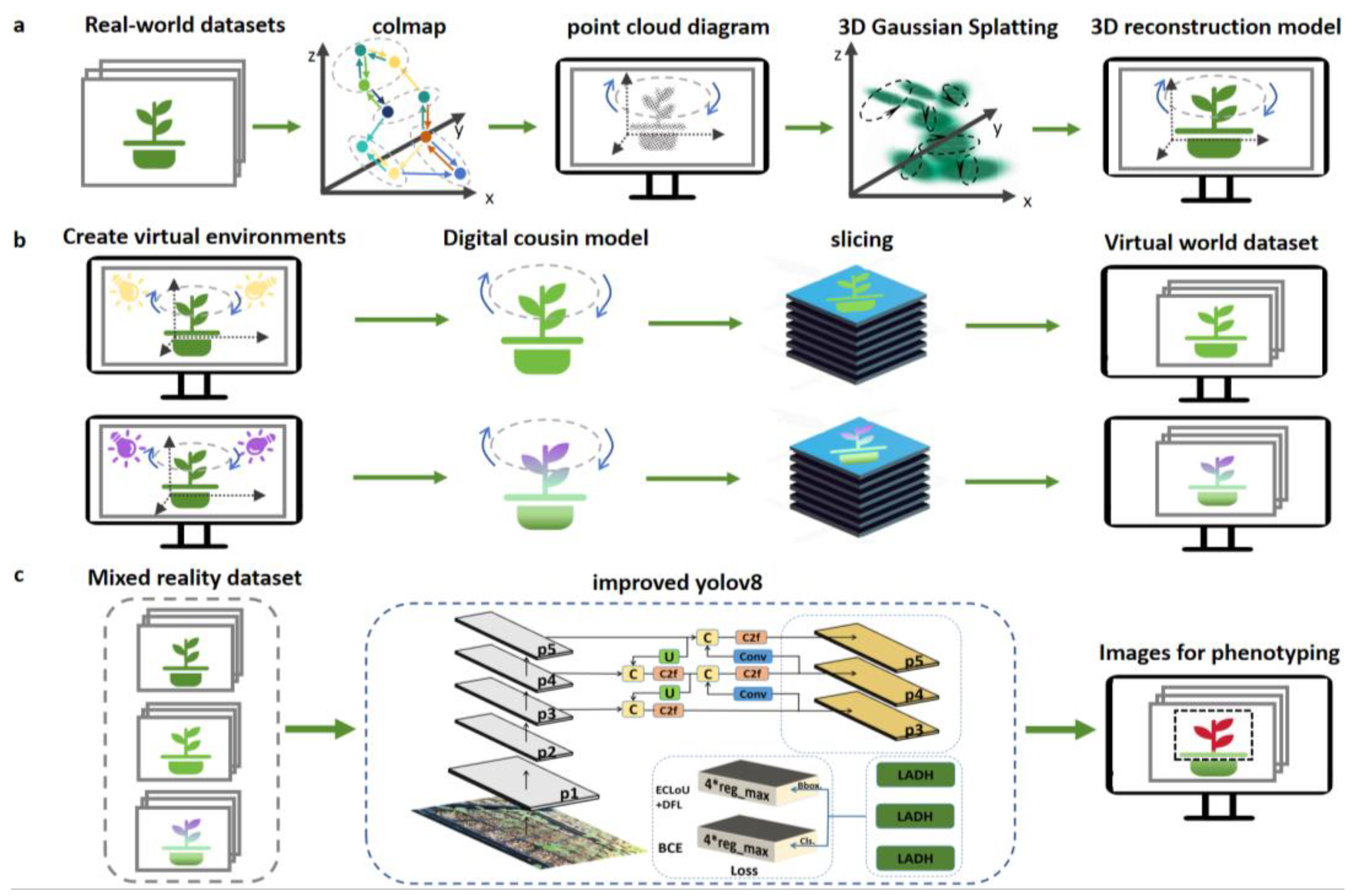

2.1. Overall process from creation of mixed real-virtual datasets to semantic segmentation.

2.2. Data preparation

2.2.1. Image acquisition

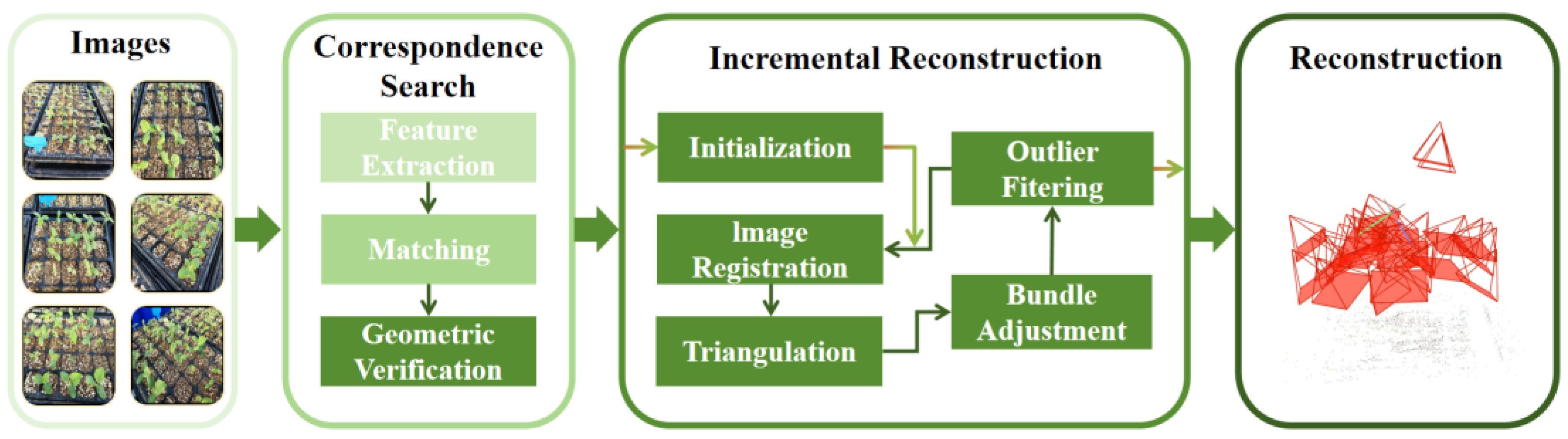

2.2.2. Generation of point cloud datasets for 3D Gaussian Splatting

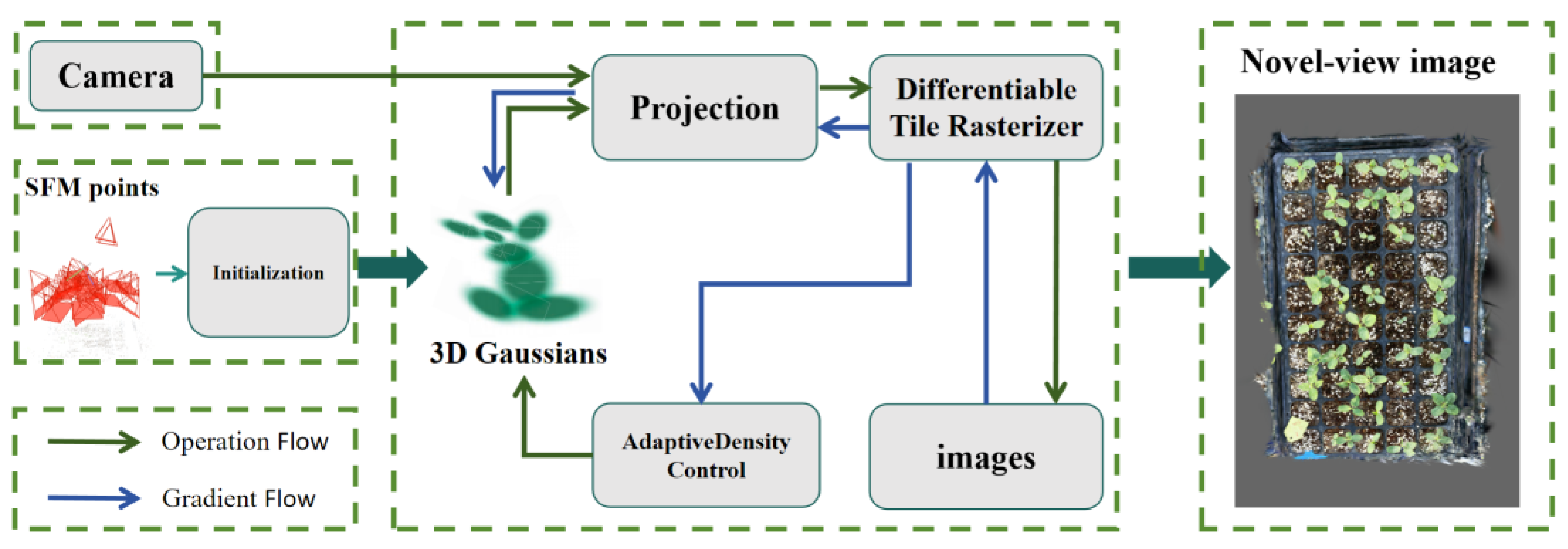

2.3. Building 3D Scenes with 3D Gaussian Splatting

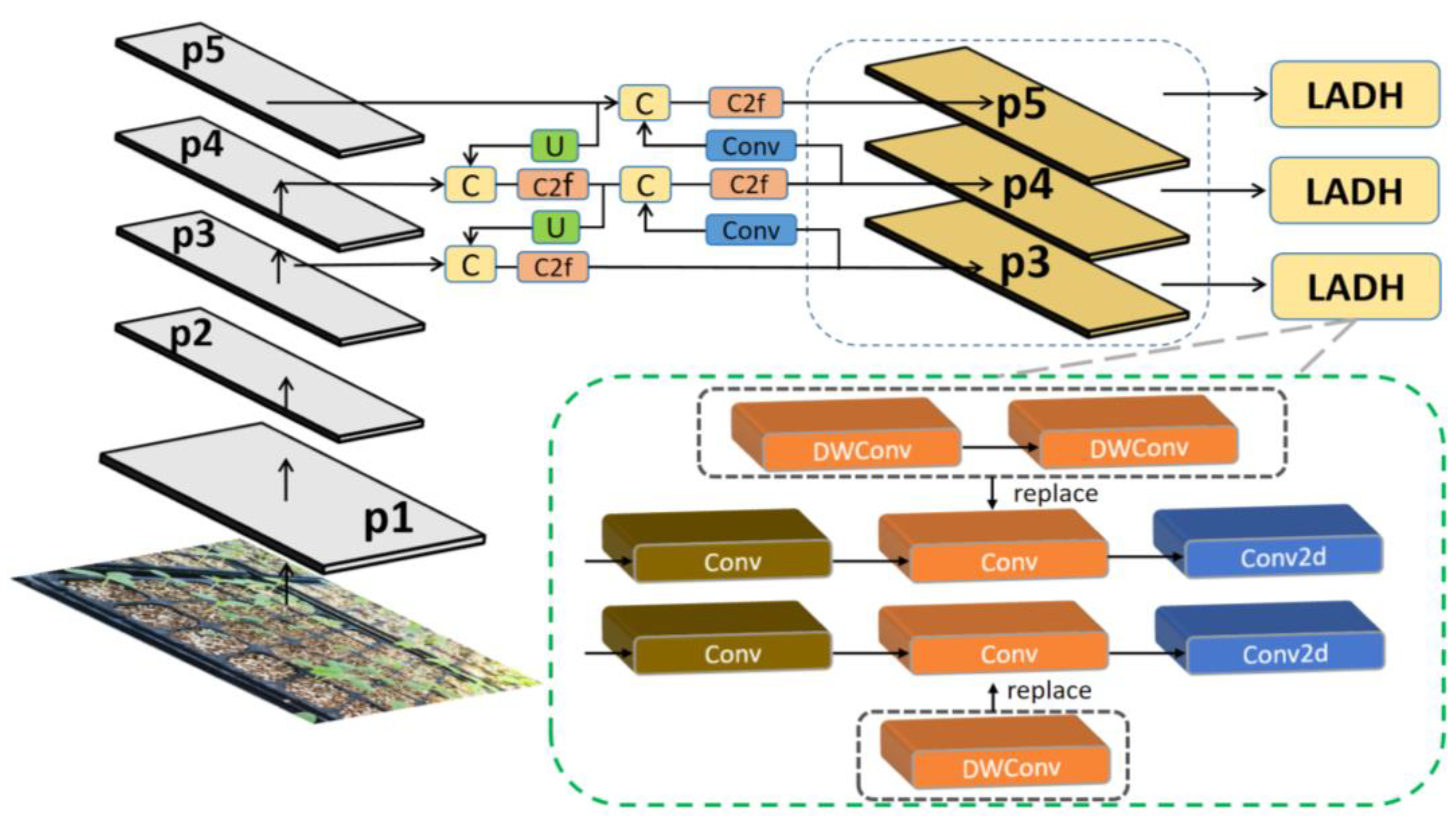

2.4. Implementation of YOLOv8 improvements

2.4.1. Improving the detection model of YOLOv8

2.4.2. LADH-Head

2.4.3. SPPELAN

2.4.4. Focaler-ECIoU

3. Results

3.1. Experimental setup

3.2. D models generated with 3D Gaussian Splatting

3.2.1. RGB imaging datasets in real world

3.2.2. Emonstration in 2D imaging in virtual world

3.2.3. Demonstration of 3D geometry extraction in virtual world

3.3. The perfromances of Improved YOLOv8

3.3.1. Comparative analysis of the performance of different models

3.3.2. Improved YOLOv8 detection model ablation test

4. Discussion

4.1. RGB imaging dataset from real and virtual world

4.2. Performance analysis and comparison of improved YOLOv8 semantic segmentation models

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saranya, T. , Deisy, C., Sridevi, S., & Anbananthen, K. S. M. A comparative study of deep learning and Internet of Things for precision agriculture. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 122, 106034. [Google Scholar]

- Kierdorf, J. , Junker-Frohn, L. V., Delaney, M., Olave, M. D., Burkart, A., Jaenicke, H.,... & Roscher, R. GrowliFlower: An image time-series dataset for GROWth analysis of cauLIFLOWER. Journal of Field Robotics 2023, 40, 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. , Zhang, Y., Wen, W., Gu, S., Lu, X., & Guo, X. The future of Internet of Things in agriculture: Plant high-throughput phenotypic platform. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 280, 123651. [Google Scholar]

- Strock, C. F. , Schneider, H. M., & Lynch, J. P. Anatomics: High-throughput phenotyping of plant anatomy. Trends in Plant Science 2022, 27, 520–523. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y. , Wu, Y., Yang, X., Liu, F., & Liao, Y. Review the state-of-the-art technologies of semantic segmentation based on deep learning. Neurocomputing 2022, 493, 626–646. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J. , Cheng, F., Huang, Y., & Bie, Z. Grafting watermelon onto pumpkin increases chilling tolerance by up regulating arginine decarboxylase to increase putrescine biosynthesis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 12, 812396. [Google Scholar]

- Dallel, M. , Havard, V., Dupuis, Y., & Baudry, D. Digital twin of an industrial workstation: A novel method of an auto-labeled data generator using virtual reality for human action recognition in the context of human–robot collaboration. Engineering applications of artificial intelligence 2023, 118, 105655. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, T. , Wong, J., Jiang, Y., Wang, C., Gokmen, C., Zhang, R.,... & Fei-Fei, L. (2024). Acdc: Automated creation of digital cousins for robust policy learning. arXiv e-prints, arXiv-2410.

- Samavati, T. , & Soryani, M. Deep learning-based 3D reconstruction: a survey. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 9175–9219. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G. , Kim, Y., Yun, J., Moon, S. W., Kim, S., Kim, J., Park, J., Badloe, T., Kim, I., & Rho, J. Metasurface-driven full-space structured light for three-dimensional imaging. Nature communications 2022, 13, 5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J. , & Yoo, S. K. Design of ToF-Stereo Fusion Sensor System for 3D Spatial Scanning. Smart Media Journal 2023, 12, 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H. , Zhang, H., Li, Y., Huo, J., Deng, H., & Zhang, H. Method of 3D reconstruction of underwater concrete by laser line scanning. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2024, 183, 108468. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Wang, S., Bai, Z., Wang, H., Li, S., & Wen, S. Research on 3D reconstruction of binocular vision based on thermal infrared. Sensors 2023, 23, 7372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z. , Peng, S., Niemeyer, M., Sattler, T., & Geiger, A. Monosdf: Exploring monocular geometric cues for neural implicit surface reconstruction. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 25018–25032. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S. , & Wei, H. A global generalized maximum coverage-based solution to the non-model-based view planning problem for object reconstruction. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2023, 226, 103585. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbl, B. , Kopanas, G., Leimkühler, T., & Drettakis, G. 3D Gaussian Splatting for Real-Time Radiance Field Rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 139–1. [Google Scholar]

- Sodjinou, S. G. , Mohammadi, V., Mahama, A. T. S., & Gouton, P. A deep semantic segmentation-based algorithm to segment crops and weeds in agronomic color images. information processing in agriculture 2022, 9, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifani, K. , & Amini, M. Machine learning and deep learning: A review of methods and applications. World Information Technology and Engineering Journal 2023, 10, 3897–3904. [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar, B. , Bayraktar, R., Ozturk, A. E., & Arayici, Y. Implementing PointNet for point cloud segmentation in the heritage context. Heritage Science 2023, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. , Zhang, D., Luo, L., & Yi, T. PointResNet: A grape bunches point cloud semantic segmentation model based on feature enhancement and improved PointNet++. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 224, 109132. [Google Scholar]

- La, Y. J. , Seo, D., Kang, J., Kim, M., Yoo, T. W., & Oh, I. S. Deep Learning-Based Segmentation of Intertwined Fruit Trees for Agricultural Tasks. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2097. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G. , Hou, Y., Cui, T., Li, H., Shangguan, F., & Cao, L. YOLOv8-CML: A lightweight target detection method for Color-changing melon ripening in intelligent agriculture. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 14400. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B. , Li, Y., Bie, Z., Peng, C., Huang, Y., & Xu, S. MIX-NET: Deep learning-based point cloud processing method for segmentation and occlusion leaf restoration of seedlings. Plants 2022, 11, 3342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z. , Liu, X., Guan, H., Yin, J., Duan, F., Zhang, S., & Qv, W. A depth map fusion algorithm with improved efficiency considering pixel region prediction. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2023, 202, 356–368. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, C. , Chen, R. C., Yu, H., & Jiang, X. Robust detection method for improving small traffic sign recognition based on spatial pyramid pooling. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2023, 14, 8135–8152. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H. , Lan, L., Zhang, J., Zhang, X., Zhan, Y., & Luo, Z. IoUformer: Pseudo-IoU prediction with transformer for visual tracking. Neural Networks 2024, 170, 548–563. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C. , & Duoqian, M. Control distance IoU and control distance IoU loss for better bounding box regression. Pattern Recognition 2023, 137, 109256. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. , & Zhang, S. Focaler-IoU: More Focused Intersection over Union Loss. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10525. [Google Scholar]

- Venu, D. N. PSNR based evalution of spatial Guassian Kernals For FCM algorithm with mean and median filtering based denoising for MRI segmentation. IJFANS International Journal of Food and Nutritional Sciences 2023, 12, 928–939. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J. , Jiang, G., Ding, W., & Zhao, Z. Fast Digital Orthophoto Generation: A Comparative Study of Explicit and Implicit Methods. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 786. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Resolution | 4624*3472 |

| Flash bulb | none |

| Storage space | 256GB |

| Weight | 210g |

| Battery capacity | 4700mAh |

| DATASET | 3D GAUSSIAN SPLATTING(Strong light) | Instant NGP(Strong light) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-7000 | PSNR-7000 | Time-30000 | PSNR-30000 | Time | PSNR | |

| S1 | 5.38min | 25.22 | 30.03min | 32.31 | 3.05min | 21.28 |

| S2 | 5.87min | 26.02 | 27.65min | 32.09 | 3.13min | 21.65 |

| S3 | 6.00min | 25.55 | 30.85min | 39.17 | 3.82min | 20.77 |

| S4 | 5.45min | 24.64 | 31.52min | 33.67 | 3.18min | 20.25 |

| S5 | 6.15min | 26.11 | 29.38min | 35.61 | 3.65min | 21.02 |

| S6 | 5.77min | 30.34 | 29.85min | 39.01 | 3.45min | 21.84 |

| S7 | 5.82min | 27.40 | 27.98min | 35.11 | 3.58min | 20.34 |

| S8 | 6.03min | 27.49 | 29.62min | 36.37 | 3.98min | 20.67 |

| S9 | 5.35min | 27.40 | 27.55min | 35.11 | 3.25min | 20.14 |

| S10 | 5.67min | 16.51 | 22.87min | 22.31 | 3.33min | 13.27 |

| S11 | 6.35min | 18.20 | 24.65min | 23.56 | 4.11min | 14.54 |

| S12 | 5.82min | 24.63 | 28.45min | 31.68 | 3.87min | 19.51 |

| DATASET | 3D GAUSSIAN SPLATTING(Medium light) | Instant NGP(Medium light) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-7000 | PSNR-7000 | Time-30000 | PSNR-30000 | Time | PSNR | |

| S1 | 6.77min | 24.72 | 31.55min | 32.64 | 3.87min | 20.96 |

| S2 | 7.02min | 27.65 | 33.25min | 36.57 | 4.30min | 21.88 |

| S3 | 5.87min | 27.52 | 30.62min | 35.97 | 3.55min | 21.24 |

| S4 | 6.55min | 27.42 | 32.45min | 37.43 | 3.67min | 19.32 |

| S5 | 6.52min | 25.23 | 34.21min | 34.97 | 3.82min | 20.85 |

| S6 | 6.32min | 28.37 | 33.30min | 36.65 | 3.58min | 21.98 |

| S7 | 6.45min | 26.07 | 33.75min | 35.78 | 3.45min | 20.65 |

| S8 | 6.77min | 25.74 | 32.25min | 33.80 | 3.13min | 20.14 |

| S9 | 5.98min | 27.12 | 29.82min | 36.64 | 3.85min | 22.54 |

| S10 | 6.77min | 25.84 | 34.52min | 33.75 | 4.03min | 20.32 |

| S11 | 6.21min | 24.51 | 30.85min | 31.55 | 4.48min | 19.85 |

| S12 | 6.13min | 25.98 | 29.77min | 33.87 | 3.70min | 20.66 |

| DATASET | 3D GAUSSIAN SPLATTING(Violet light) | Instant NGP(Violet light) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-7000 | PSNR-7000 | Time-30000 | PSNR-30000 | Time | PSNR | |

| S1 | 6.18min | 26.16 | 29.85min | 33.43 | 4.14min | 23.66 |

| S2 | 5.93min | 23.94 | 30.03min | 30.85 | 3.35min | 21.54 |

| S3 | 6.10min | 28.60 | 23.58min | 34.47 | 3.77min | 21.72 |

| S4 | 6.21min | 25.65 | 32.65min | 33.95 | 3.68min | 19.41 |

| S5 | 6.33min | 28.61 | 23.68min | 34.62 | 4.32min | 23.85 |

| S6 | 6.17min | 17.15 | 23.45min | 24.90 | 3.70min | 14.32 |

| S7 | 5.85min | 25.53 | 28.70min | 32.55 | 3.82min | 20.25 |

| S8 | 6.11min | 31.10 | 23.48min | 36.61 | 3.97min | 23.11 |

| S9 | 5.87min | 26.16 | 28.63min | 34.14 | 3.35min | 20.74 |

| S10 | 5.97min | 26.34 | 23.77min | 34.93 | 3.55min | 20.25 |

| S11 | 6.30min | 25.96 | 26.97min | 32.76 | 3.82min | 20.66 |

| S12 | 6.18min | 24.60 | 27.80min | 32.05 | 3.80min | 19.58 |

| MODELS | BOX-MAP50 | MASK-MAP50 | LOSS | EPOCH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOV5N-SEG | 0.895 | 0.909 | 0.855 | 201 |

| YOLOV8N-SEG | 0.907 | 0.909 | 0.765 | 370 |

| OURS | 0.910 | 0.913 | 0.616 | 254 |

| Methods | LADH | Focaler-ECIoU | SPPLAN | mAP50(B) | mAP50(M) | Epoch | Loss | GFLOPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | × | × | × | 0.907 | 0.909 | 370 | 0.765 | 12.0 |

| LADH | √ | × | × | 0.906 | 0.908 | 201 | 0.854 | 11.6 |

| LADH+ Focaler-ECIoU | √ | √ | × | 0.907 | 0.913 | 181 | 0.667 | 11.6 |

| LADH+ Focaler-ECIoU +SPPELAN | √ | √ | √ | 0.910 | 0.913 | 254 | 0.616 | 11.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).