1. Introduction

Virtual spaces allow the development of knowledge of a place [

1] and provide unique experiences so that users can get to know the site in advance [

2]. Augmented reality applications (ARA) provide more information about the environment by augmenting the application with experiential elements simultaneously [

3]; which could be used by people with blindness to navigate freely through an unfamiliar space. Some applications have been used to reduce students ‘stress and improve their mental well-being [

3], others were used in design and construction and still others were used for entertainment and education [

4].

Various health conditions can affect human mobility permanently or transiently, impacting people´s daily lives [

5]. For blind individuals the vision of the world is realized through hearing and touch, with them they obtain information from the environment and explore their surroundings [

6] . They establish spatial relationships and create their mental map based on their previous visual experiences [

7,

8,

9].

The design of applications for blind people must contain appropriate physical and cognitive interfaces that allow for good performance and minimal mental effort [

10]. According to Armougum et al. [

11], an individual's working memory can benefit from using multiple sensory channels. Several mobility support systems for blind people often use auditory and haptic devices to provide safety and confidence in users [

12,

13]. At the Polytechnic University of Madrid, several virtual and augmented reality applications were developed that use different sensitive interfaces to enable blind people to take virtual visits in advance of unfamiliar places [

14,

15].

Cognitive load is the mental effort made by an individual to perform a certain activity, and is related to the amount of memory used and the difficulty of its execution [

16]. When visiting an unfamiliar space virtually, the cognitive load of blind people increases, since they must identify and locate objects of interest using only the information from the application [

7,

17]. The ability to multitask is crucial, as it requires the simultaneous execution of cognitive and motor tasks [

18]. This ability is fundamental for a wide range of daily activities, such as gathering information about the anticipated route, allowing quick reactions to the environment; or perceiving alerts to potential hazards and obstacles during ambulation [

19]. The interaction between cognitive processes and motor actions is essential for performing efficiently and safely in a wide variety of environments.

The dimensions of cognitive load are multiple [

20], from the interpretation of biosignals [

19] or physiological data of individuals [

21], to the inference in the execution of a task [

22]. According to Vasquez [

23] cognitive load should be approached from a comprehensive perspective considering: cognitive demands, task complexity, task characteristic, temporal organization, work pace and health consequences. According to Cegarra and Chevalier [

24] the techniques to measure mental workload are: performance measures, subjective measures and physiological measures; each technique has advantages and limitations. An indicator of cognitive load corresponds to the mental effort applied by an individual while performing a task or immediately after completing it [

25].

In this study, the cognitive load of fourteen blind individuals was measured during navigation through a test maze, using as a secondary task, listening and memorizing of five words during the journey. According to Plummer et al. [

26] the difficulty of the cognitive task has a direct effect on the second auditory task when the user walks through the virtual environment. According to Clark, Kirschner and Sweller [

27] the memory has a limited capacity in size and complexity, so the number of words used in this study was lower than the maximum contemplated in other studies [

28].

2. Materials and Methods

There are four sections:

Section 2.1 describes the study participants.

Section 2.2 describes the measurement of the cognitive load of the participants.

Section 2.3 describes the development of the navigation system. Finally, section 2.4 describes the study design used in the research.

2.1. Participants

Fourteen adults with more than eight years of blindness and no other physical impairment participated in the present study. There were 9 men and 5 women with an average age of 45 years. All were affiliated the ONCE Foundation (National Organization of the Spanish Blind).

2.2. Cognitive Load

The cognitive load was modeled as the Mahalanobis distance of two four-dimensional vectors. Whose dimensions are described in

Table 1. The origin vector (1, 1, 1,1) represents that the user successfully completed all the activities established in this research.

Concentration and working memory: A segment of the Montreal test was used to assess participants’ concentration and working memory. The method is described in the procedure (

Section 2.4). Each correct word is worth 1 point. The data are normalized. 1 corresponds to 5 correct words and 0 to none.

To find a way through the maze: Participant enters the maze with his/her white cane and the mobile application. They go to the target point using the information provided by the App. If he/she completes the route. 1 point is assigned, otherwise 0.

Running time: A stopwatch is used to record the time it takes the participant to complete the maze. The shortest time is assigned 1. If the participant did not reach the target point. 0 is assigned.

Deferred memory: Deferred memory is linked to the working memory. During the tour the researcher pronounced five words. At the end of the tour the participant had to remember these words. One point was assigned for each of the words remembered regardless of the order. Incorrect or omitted words were considered an information processing error that was attributed to excessive mental effort to complete this task. For the evaluation 1 corresponds to five correct words and 0 to none.

2.3. Navigation System

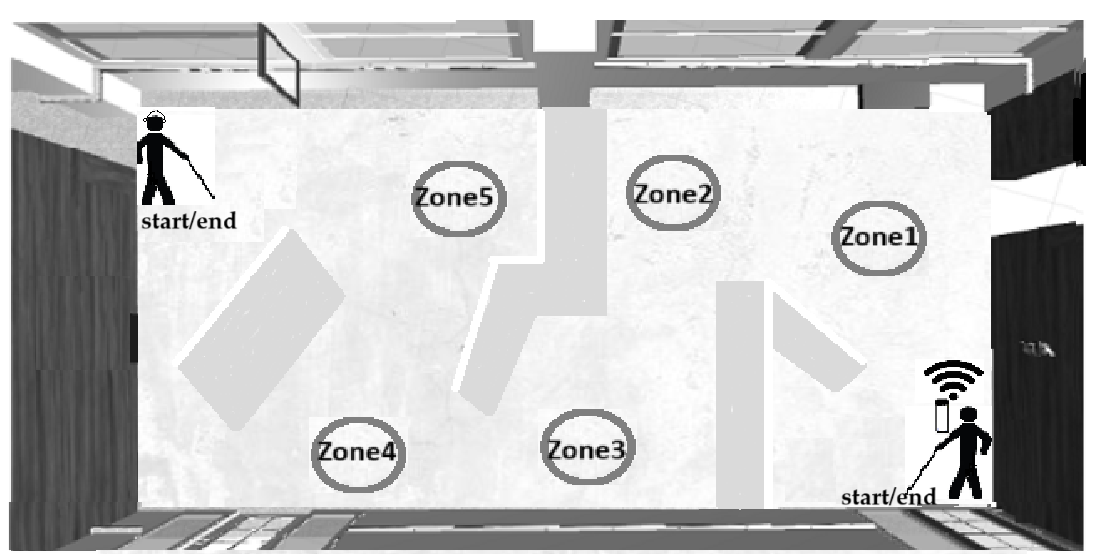

The system tracks user’s progress through the maze and dynamically updates the scene in the virtual world. A laser and infrared sensor attached to the smartphone establishes the distance to objects and structures that appear during the walkthrough. Proximity beacons were also used to correct the error produced by the sensor when the laser is pointed at windows. Bone headsets connected to the smartphone via Bluetooth 4.0 were used to allow the user to receive auditory notifications. Since the user requires a free hand to carry the with cane, the navigation system was placed on the participant’s chest (See

Figure 1).

2.3.1. Test Scenarios

Since large spaces are difficult to control. A 16.75mx5.63mx2.5m test maze was designed on the second floor of the Biomedical Technology Center at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

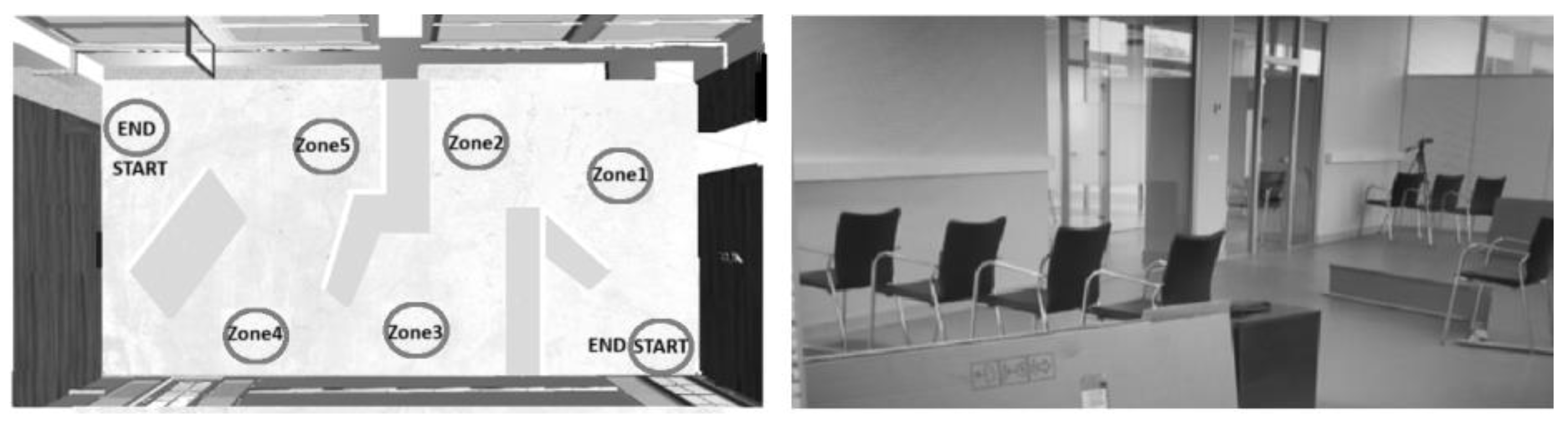

Figure 2.

Test scenarios a) virtual; b) real.

Figure 2.

Test scenarios a) virtual; b) real.

The space had six windows. Two columns and two access doors and was divided into five sections using chairs, carboard and wood. Each section had an obstacle-free zone, which was marked with colored tape on the floor. The maze could be traversed in both directions.

2.3.2. Augmented Reality Applications

Four applications were developed to guide participants through the maze. Two for traversing the maze in one direction and two for traversing it in the opposite direction. Each virtual application shows the maze, the view of which is the starting position of the avatar. Each App was implemented as a video game for iOS using Unity3D. The Apps require a smartphone with a gyroscope and a sensor with laser and infrared for user tracking and maze mapping. In the design of the application, two 0.5-meter side rectangular prisms were placed to the left and right of the avatar and inform the user about objects or structures entering these areas. Participants can stop or change direction at will. Causing the avatar to stop or walk in the application. In two of the applications. Five safe zones were modeled as 0.75m radius cylinders within the maze to provide supplemental information to the user. Although the visual information is irrelevant for blind people. It was useful for the development and debugging process of the data obtained.

Cognitive and Physical Interfaces of the Mobile Application

The physical interface is the medium used to communicate between the user and the mobile device. The cognitive interface indicates how the user acquires information from the location.

Previous studies conducted within the eGlance project [14, 15, 30], allowed choosing three physical interfaces: 3D sounds to guide users through unfamiliar environments, pointing out the direction and distance to the target point using bone earphones. A 440Hz tone of different intensities was used to warn of nearby obstacles and the female voice was used to generate complementary information, linked to the user’s progress while walking through the maze.

Interface 1: When the participant enters the test maze, the mobile application continuosly generaties a 3D sound that indicates the end of the maze. The participante walks freely through this space using his cane in a similar way as he would in a confined space, sensing the presence of objects and structures inside. The App generates a warning tone about obstacles that apperar near the user, so that he/she can modify his/her trajectory and avoid collisions. The closer the user is to the obstacle. The higher the intensity of the tone. The user can use the wand to confirm the presence of these obstacles and change direction at will.

Interface 2: When the participant enters the test maze. The mobile application generates a 3D sound that guides the user to an obstacle-free area. Each time the user reaches a safe area. The application generates a female voice that tells the participant the success achieved in each section of the course and the distance to the next point; the application then generates a new 3D sound for the user to continue his/her journey to the next safe area, until the entire course is completed. A total of five safe areas were established. Participants changed trajectory. The system alerted them with a voice message.

2.4. Study Design

A cross-sectional between-subjects study was performed. Talking into account the availability of physical space and the size of the research team, it was decided to limit the duration of the experiment based on previous studies conducted with the participants. Everyone participated in two runs. One in the direct direction with one cognitive interface and one in the opposite direction with another interface. To minimize the impact of possible carryover effects. Both direction and interface were randomized according to the Latin square in

Table 2.

Procedure

Participantes signed their prior consent before the start of the study. The activities were recorder by two cameras. Which were placed at opposite ends of the maze. The researchers used observational logs to record the time, responses and comments of the participants. No time limit was set for navigation. The procedure was divided into five stages.

Welcome: The entire team welcomed the participants to the present study. They were informed about the objectives of the study and their participation in it.

Assessment of concentration and working memory: A list of five words was read at a normal pace for the user to hear and repeat. Subsequently, the same words were reread. Cut now the participant was asked to remember them for later. Next, the participant is asked to clap once each time he/she hears the letter A; the researcher read a series of the letters. At the end of the reading of the letters. The participant was asked to repeat the words he or she had initially heard. The number of words and correct order was recorder by the researcher.

Training: A member of the research team placed the bone headphones on the user’s head; then opened a practice application on the smartphone for the user to follow the sound by rotating on its own axis. Next. The navigation device was placed on the participant’s chest. The user was asked to move around a test room, following the sound until the App indicated that he/she had arrived. This stage has no time constraints. The device is removed once the participant’s training was completed.

Navigation process: A team member selects the application according to

Table 2; places the navigation system on the chest and places the user at the beginning of the maze. The participant was asked to walk through the maze until the application indicated that he/she had reached the destination. In addition, the user was asked to retain in memory the words spoken by the researcher during the walkthrough. If the researcher observed that the participant could not overcome the obstacles places within the maze, the test was terminated. At this stage the navigation time and the success in reaching the destination were recorded. In the case that the participant did not reach the destination, these two variables are recorded as 0.

Post/navigation: Each participant was asked to recall all the words pronounced by the researcher during the running. The responses were recorded manually. At this stage were recorded the number of correct words recalled regardless of the order. Finally. A five-minute pause was taken before continuing with the second run-through.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

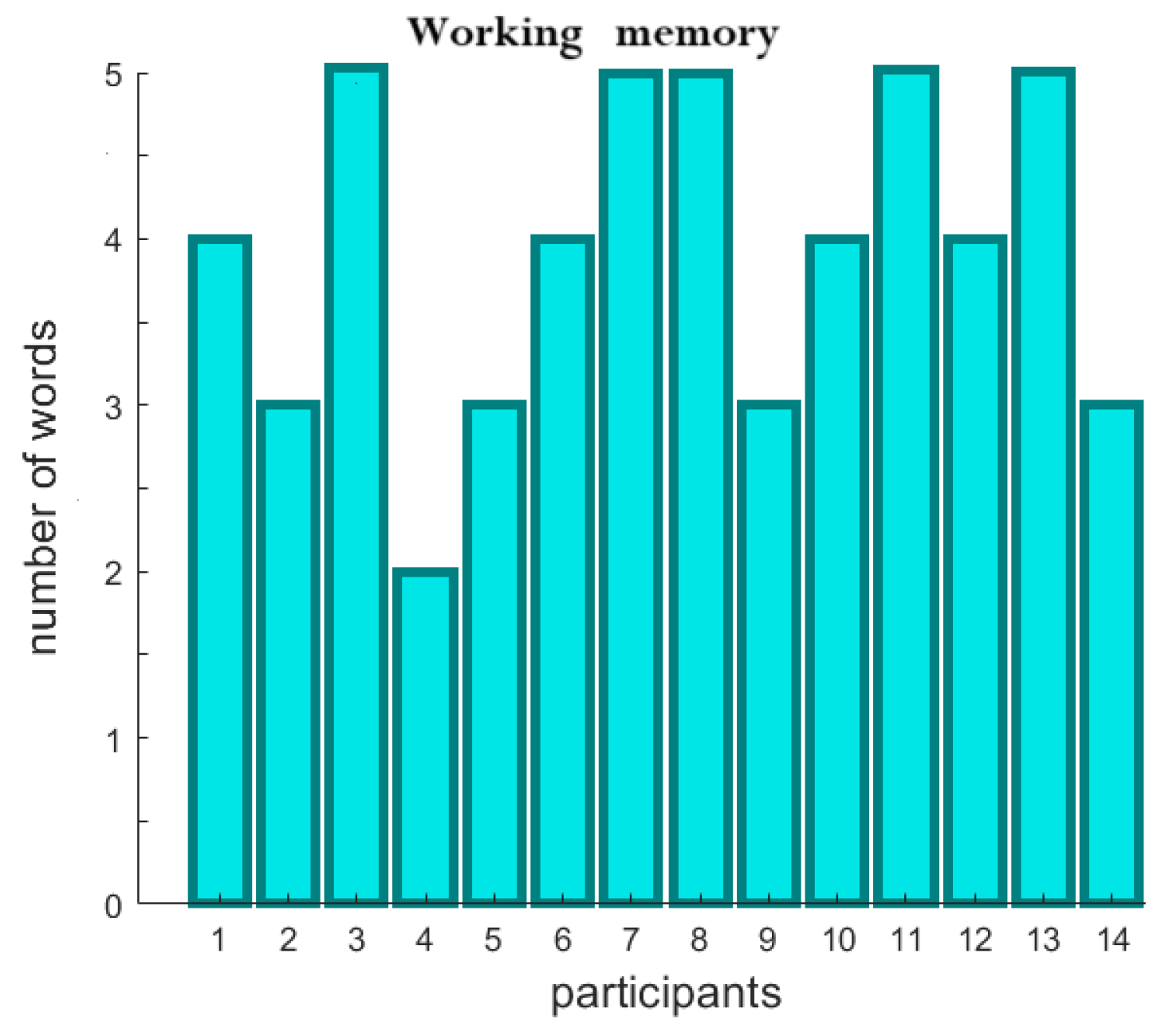

3.1. Concentration and Working memory

The working memory test is performed after the concentration test. Which presented the following variations (See Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Working memory.

Figure 3.

Working memory.

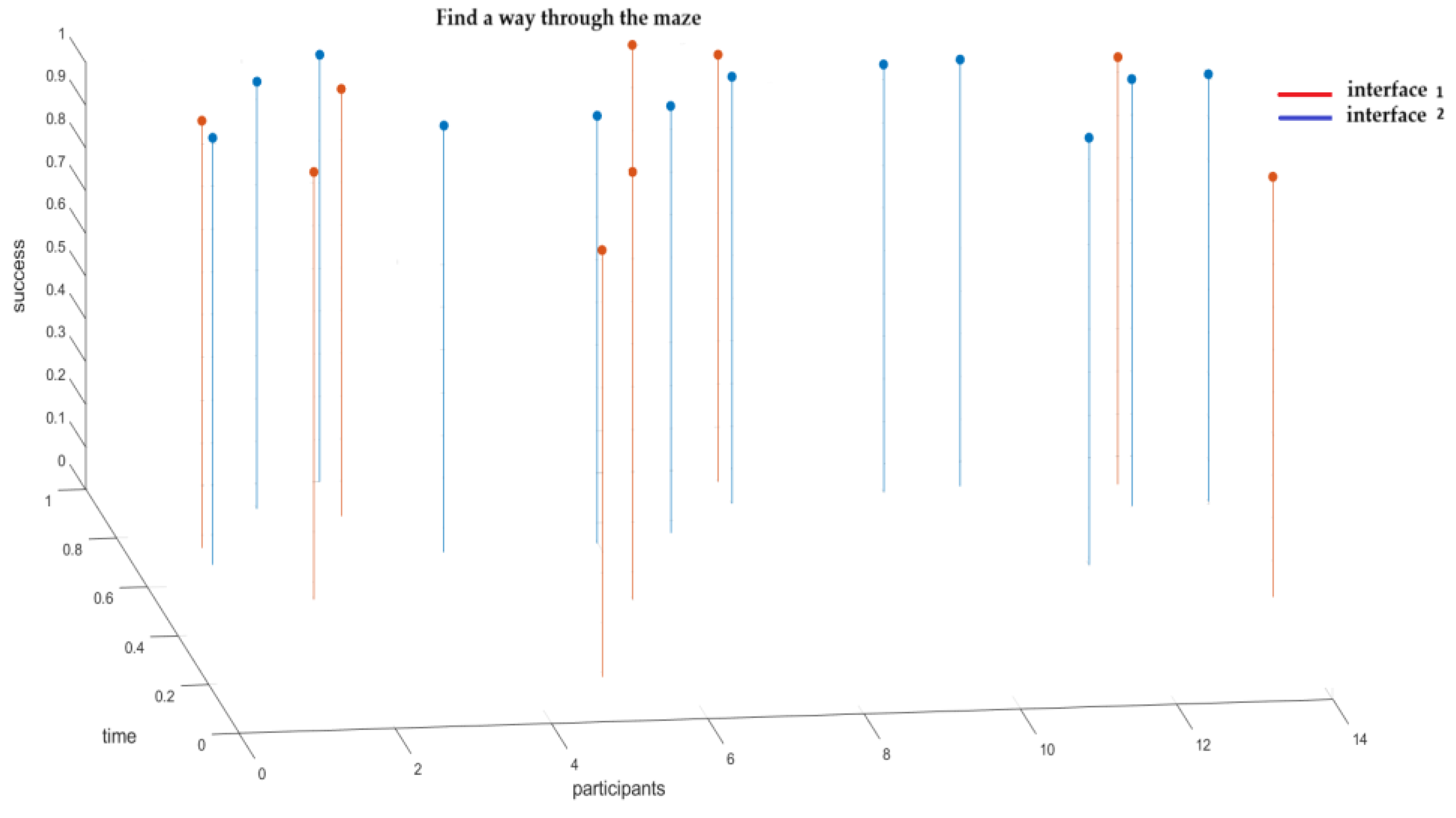

3.2. To find a Way Through the Maze

Success in completing the course and the time taken to navigate the maze were evaluated (See Figure 5).

The dependence of success with each configuration was evaluated with the Friedman test. After verifying the assumptions for this type of test. The result was not statistically significant (Chi-sq=1. DF=1. P-value=0.3173). A higher success rate (21.43%) was observed when interface 2 was used.

The dependence of running time was evaluated with Friedman test. The time spent during the direct path was much less, than, in the opposite path, so each path was evaluated separately. The direct path was evaluated, and the result was statistically significant (Chi-sq=3.85, DF=1, p-value=0.043). The opposite trajectory was also evaluated, whose result was not statistically significant (Chi-sq=0.2, DF=1, p-value=0.654), which made us think that the opposite trajectory had a much higher degree of complexity, which had an impact on the measurement of this variable. So, another study implementing a new orientation method could measure the efficiency of the system to reach the target point, in any new space. A 17.8% reduction in the time taken to traverse the maze in the direct trajectory and an 11% reduction in the time taken to traverse the maze in the opposite trajectory was observed when using interface 2.

Figure 4.

Success to find a way through the maze and running time.

Figure 4.

Success to find a way through the maze and running time.

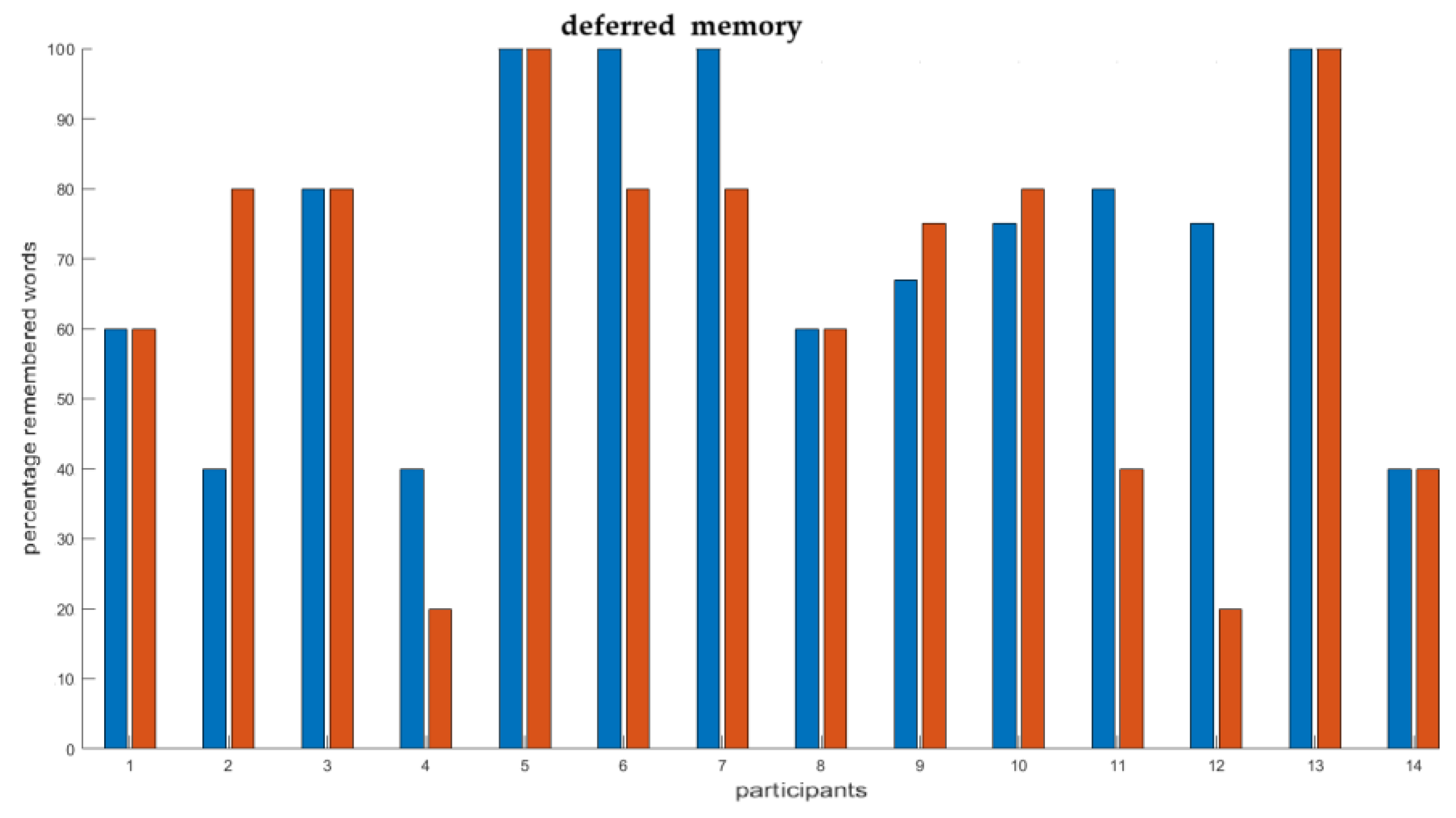

3.3. Deferred Memory

The deferred memory test is performed after the participant’ traverse the maze, the results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Deferred memory.

Figure 5.

Deferred memory.

The dependence of deferred memory on each interface was evaluated with the Friedman test, which was statistically non-significant (Chi-sq=0.1, DF=1, p-value=0.751). A higher percentage of correctly recalled words (7.8%) was observed when interface 2 was used.

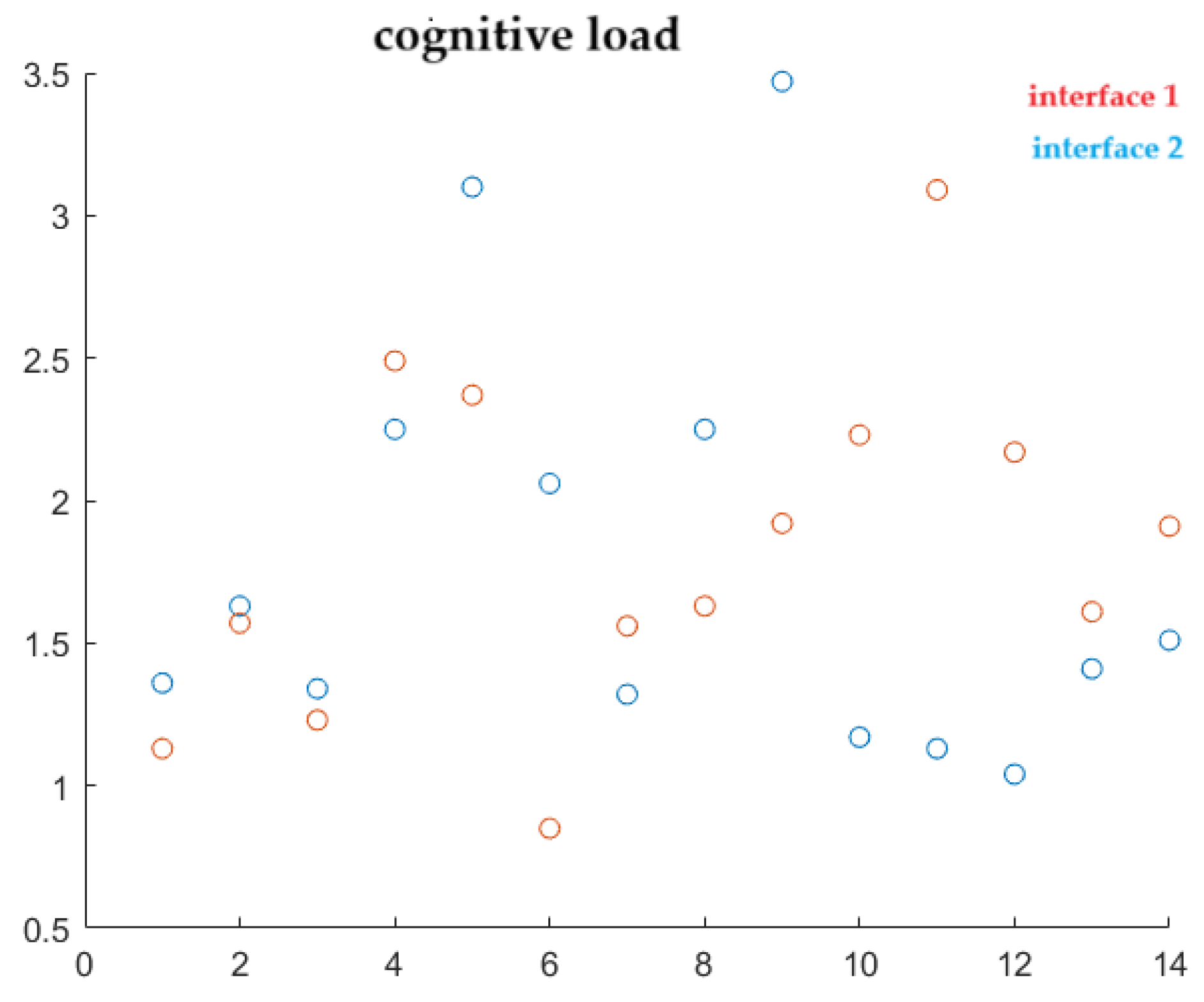

3.4. Cognitive Load

Deviations from the point of lowest cognitive load are calculated as the Mahalanobis distance of two vectors of four dimensions: working memory, running time. Success in to find a way through the maze and deferred memory. The smallest distance with respect to the origin vector corresponds to the lowest cognitive load (See Figure 9).

Figure 6.

Cognitive load.

Figure 6.

Cognitive load.

The dependence of cognitive load on configuration was evaluated with a Friedman test that was statistically non-significant (Chi-sq=0.34, DF=1, p-value=0.558). A slight reduction in cognitive load (4.3%) was observed in users who used interface 2.

4. Discussion

Traversing unfamiliar places can be exhausting for blind people, given their limited ability to recognize and avoid obstacles. Finding points of interest in an unfamiliar environment requires a great deal of mental effort, which can be reduced using virtual reality tools. Assistive systems for the blind use physical interfaces to convey information to users and provide guidance for obstacle avoidance. In this study. Two mobile applications were used by 14 blind individuals to navigate an obstacle-based maze. It was observed during testing that those participants who were slightly nervous at the beginning of their participation felt more comfortable and confident using the app built with cognitive interface 2; we presume that reaching the first safe zone without difficulty with the app increased their confidence to advance through the maze. Both apps helped users reach the goal through a test maze. Blind users using cognitive interface 2 achieved a 4.3% reduction in cognitive load. Relative to interface 1. The 93.75% of participants reached the target point using interface 2 and 71% arrived using interface 1. The running time was reduced by 53.07% using interface 2. With an appropriate effect size and significance level. Interface 1 took an additional 69 seconds on average to complete the maze. Success in reaching the goal was evident when participants used interface 2. With a 22.75% improvement over interface 1 and although there was no statistical significance. This study requires further analysis with larger numbers of users. Therefore. We argue that the application built with interface 2. Which presented more favorable results. Could be use by blind people. For navigation through unfamiliar places.

Others research [11, 31]demonstrated the efficiency of using virtual reality applications for navigation, using smaller test mazes for training, with slightly lower times than those obtained in this study, however, it worked with sighted people, thus justifying the longer time taken to running the maze. Armougum et al. [

11] used three mazes to measure alternation and cognitive load in people with normal vision during dual tasks. The study found no statistically significant differences; as the results indicate, the hearing task was not difficult enough to sufficiently affect participants’ attention.

In another study [

31] a significant difference in performance was found between two training sessions with different proportions of completed mazes, the study indicated that this result was likely due to the additional time and more difficult starting orientations of each session, which could possibly make completing the mazes more difficult. In this study, it was observed that the opposite path causes greater difficulty that the direct path. Most likely because of the initial orientation and turning they had to do to progress through the maze.

Given that the two applications guided to users through the navigation process and help them complete the tour. We presume that the chosen task is very simple and neither of the two evidenced a significant reduction in the value of the cognitive load used by the participants< however., the reduction in time was significant when interface 2 was used., so this effect could be studied in greater detail and with a larger number of users in the future. Using a more demanding task.

In another research that analyzed dual-task interference during navigation and cognitive performance in a space with and without obstacles [

31] they found significant differences in cognitive domains such as executive function. Habitual response inhibition and processing speed. In this research. Adding an auditory task during the walk increased participants’ cognitive processing and thus there was a reduction in walking speed. Especially near obstacles. However. We did not find significant differences in cognitive load. Which was the focus of this study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Video1: blind.

Author Contributions

A.C., N.G. and J.J.S worked in the conceptualization, development of methodology and validation. L.G. and R.M. worked in resources and software. N.G; writing—original draft preparation, review and editing. J.J.S.; visualization, supervision and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Cátedra Indra-Fundación Adecco (e-Glance project).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Resultados mayo 2018.xlsx

Acknowledgments

We thank to the ONCE Foundation for its collaboration with the participants and the facilities where the tests were conducted. Special thanks to blind volunteers for spending their time and effort in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Esteve-Gonzalez V, Cela-Ranilla JM, Gisbert-Cervera M (2011) Using simulation games to improve learning skills. In: 4th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation. pp 506–515.

- Rooms C, Dastan M, Ricci M, et al (2024) Enhancing Well-Being : A Comparative Study of Virtual Reality. Sensors 24:.

- Gonzalez, D.A.Z.; Richards, D.; Bilgin, A.A. Making it Real: A Study of Augmented Virtuality on Presence and Enhanced Benefits of Study Stress Reduction Sessions. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 2020, 147, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jiang, W. Research on the application value of Multimedia-Based virtual reality technology in drama education activities. Entertain. Comput. 2024, 50, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado F, Loureiro M, Bezerra M, et al (2024) Virtual Obstacle Avoidance Strategy: Navigating through a Complex Environment While Interacting with Virtual and Physical Elements. Sensors 24.

- Lahav, O.; Schloerb, D.W.; Srinivasan, M.A. Rehabilitation Program Integrating Virtual Environment to Improve Orientation and Mobility Skills for People Who Are Blind. Comput. Educ. 2014, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobo, A.; Guerrón, N.E.; Martín, C.; del Pozo, F.; Serrano, J.J. Differences between blind people's cognitive maps after proximity and distant exploration of virtual environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualotto, A.; Spiller, M.J.; Jansari, A.S.; Proulx, M.J. Visual experience facilitates allocentric spatial representation. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 236, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proulx, M.J.; Brown, D.J.; Pasqualotto, A.; Meijer, P. Multisensory perceptual learning and sensory substitution. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigeon, C.; Li, T.; Moreau, F.; Pradel, G.; Marin-Lamellet, C. Cognitive load of walking in people who are blind: Subjective and objective measures for assessment. Gait Posture 2018, 67, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armougum, A.; Orriols, E.; Gaston-Bellegarde, A.; Marle, C.J.-L.; Piolino, P. Virtual reality: A new method to investigate cognitive load during navigation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis JM, Klatzky RL, Giudice NA (2014) Representing 3D space in working memory: Spatial images from vision, hearing, touch, and language. In: Multisensory Imagery. Springer New York, pp 131–155.

- Sánchez, J.; Campos, M.d.B.; Espinoza, M.; Merabet, L.B. Audio Haptic Videogaming for Developing Wayfinding Skills in Learners Who are Blind. PMC4254778 2014, 2014, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrón, N.E.; Cobo, A.; Serrano Olmedo, J.J.; Martín, C. Sensitive interfaces for blind people in virtual visits inside unknown spaces. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2020, 133, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrón NE, Cobo A, Olmedo JJS (2018) Virtual Reality Application for Blind People in Unknown Interior Spaces. 157–162. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, G.; Yeasin, M. (2011) Cognitive Load and Usability Analysis of R-MAP for the People who are B lind or Visual Impaired. [CrossRef]

- Leppink, J. Cognitive load theory: Practical implications and an important challenge. J. Taibah Univ. Med Sci. 2017, 12, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan X, Wang K, Sun W, et al (2024) A Review of Recent Advances in Cognitive-Motor Dual-Tasking for Parkinson’s Disease Rehabilitation. Sensors 24.

- Wu Y, Zhang Z, Aghazadeh F, Zheng B (2024) Early Eye Disengagement Is Regulated by Task Complexity and Task Repetition in Visual Tracking Task.

- Stull DE (1996) The Multidimensional Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI): Its measurement and structure. - PsycNET. Am Psychol Assoc 2:175–196.

- Korivand S, Galvani G, Ajoudani A, et al (2024) Optimizing Human–Robot Teaming Performance through Q-Learning-Based Task Load Adjustment and Physiological Data Analysis. Sensors 24.

- Biondi, F.N.; Cacanindin, A.; Douglas, C.; Cort, J. Overloaded and at Work: Investigating the Effect of Cognitive Workload on Assembly Task Performance. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2020, 63, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez, P.C.; Klijn, T.P.; Moreno, M.B.; Barriga, O. Validation of subjective mental workload scale in academics staff. Cienc Y Enferm 2014, 20, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra, J.; Chevalier, A. The use of Tholos software for combining measures of mental workload: Toward theoretical and methodological improvements. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 988–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranguren Álvarez W (2013) Carga mental en el trabajo. 9–20.

- Plummer-D'Amato, P.; Brancato, B.; Dantowitz, M.; Birken, S.; Bonke, C.; Furey, E. Effects of gait and cognitive task difficulty on cognitive-motor interference in aging. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark BRE, Kirschner PA, Sweller J (2012) Putting Students on the Path to Learning The Case for Fully Guided Instruction. 6–11.

- Robison, M.K.; Unsworth, N. Working memory capacity, strategic allocation of study time, and value-directed remembering. J. Mem. Lang. 2017, 93, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletzel, S.L.; Hernandez, J.M.; Miskiel, E.F.; Mallinson, T.; Pape, T.L.-B. Evaluating the performance of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in early stage Parkinson's disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2017, 37, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrón N, Cobo A, Serrano JJ (2018) METHODOLOGY FOR BUILDING VIRTUAL REALITY MOBILE APPLICATIONS FOR BLIND PEOPLE ON ADVANCED VISITS TO UNKNOWN INTERIOR SPACES. In: IADIS 2018 International Conference. pp 3–15.

- Rothacher, Y.; Nguyen, A.; Lenggenhager, B.; Kunz, A.; Brugger, P. Walking through virtual mazes: Spontaneous alternation behaviour in human adults. Cortex 2020, 127, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).