Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

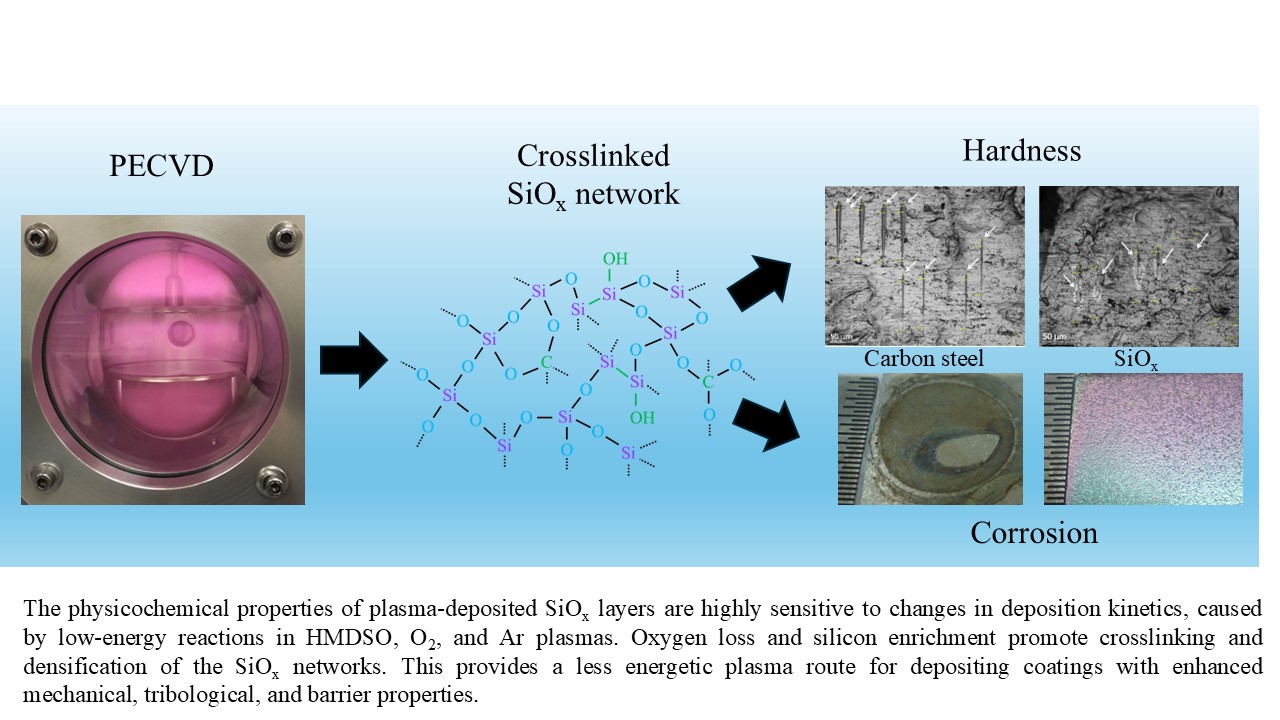

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

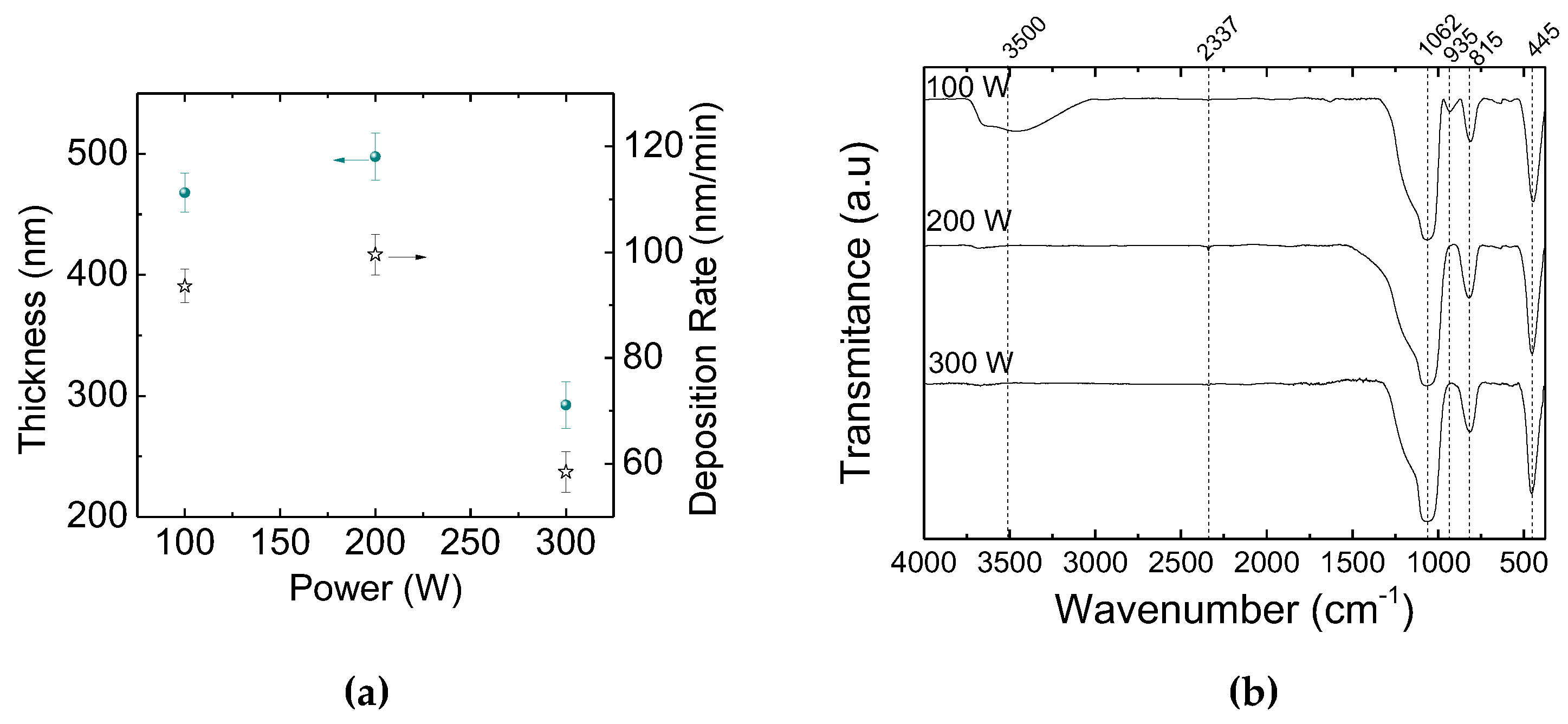

3.1. Thickness and Deposition Rate

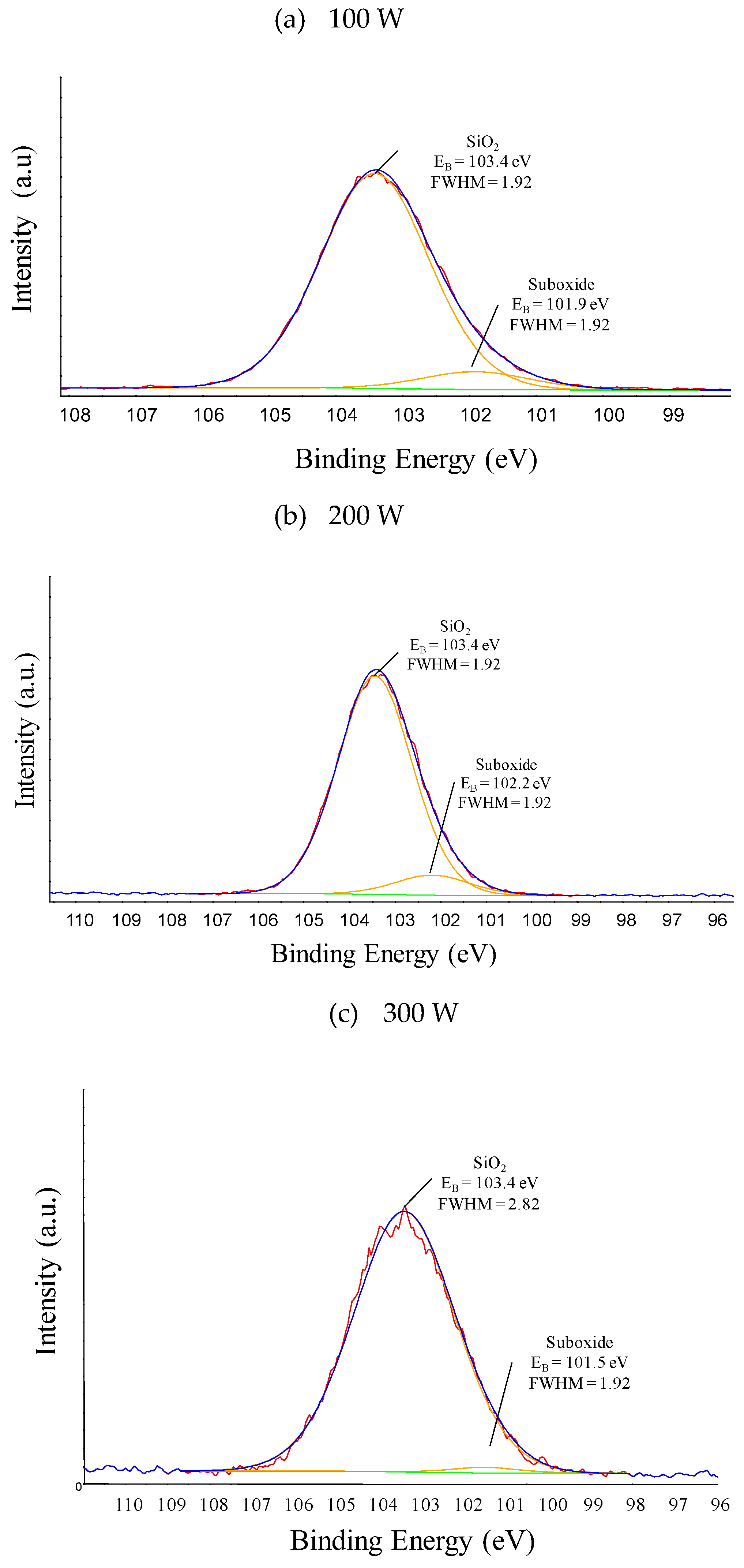

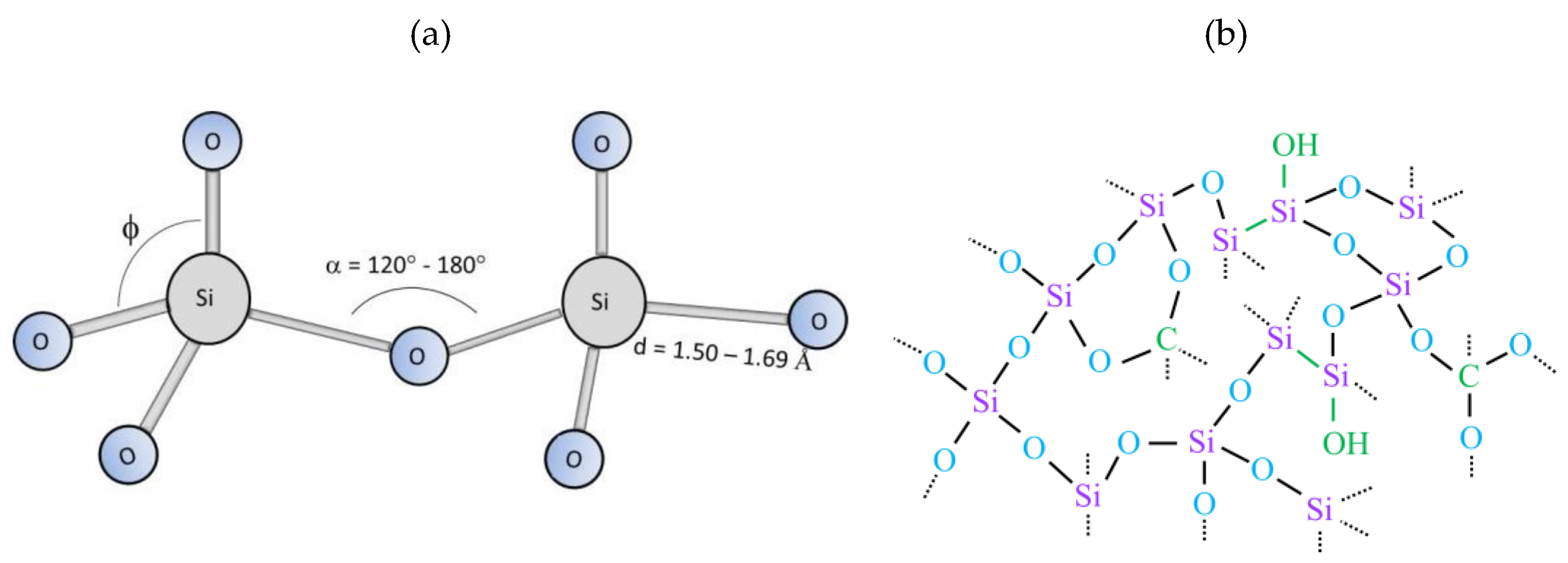

3.2. Chemical Structure an Elemental Composition

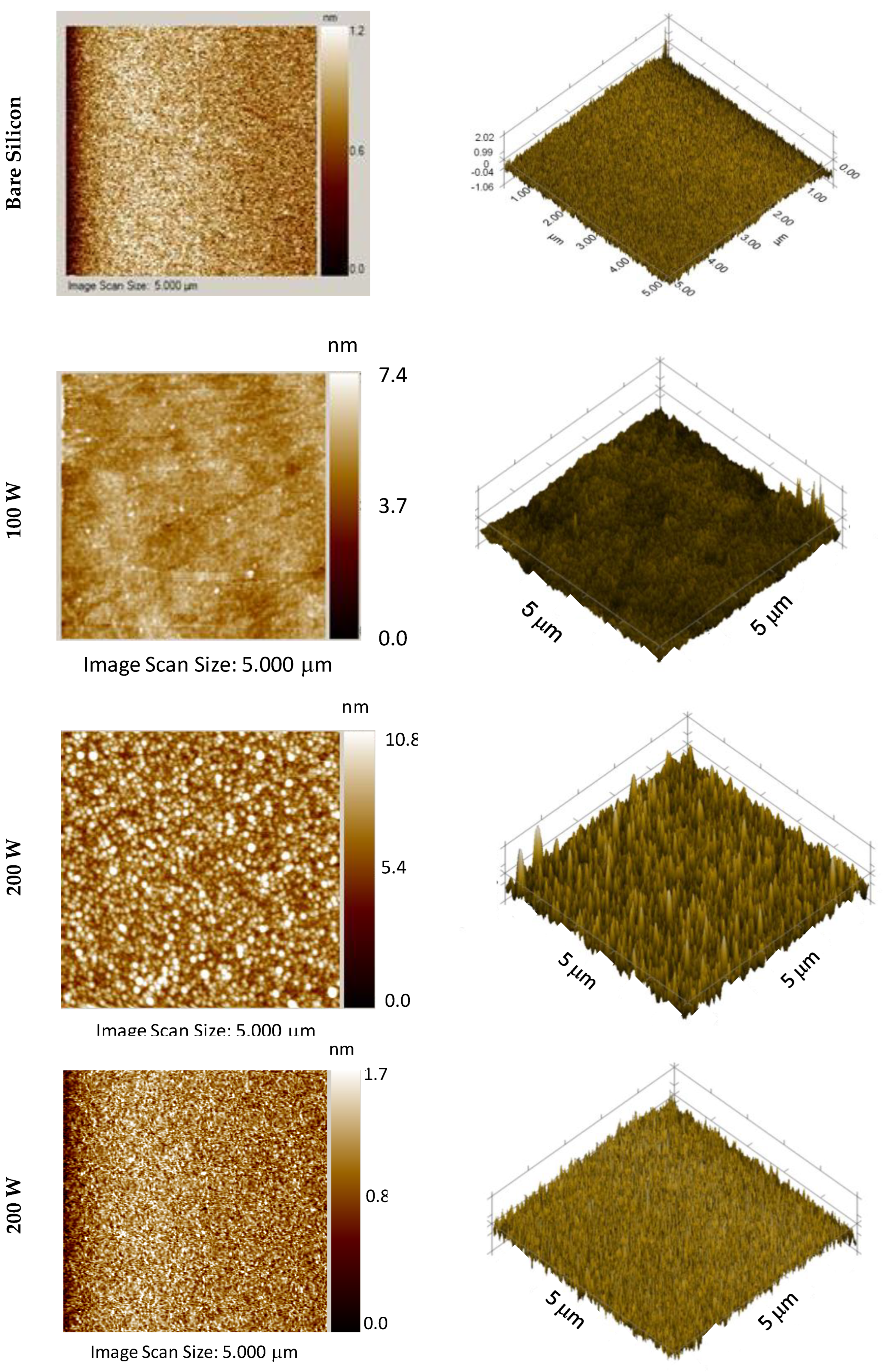

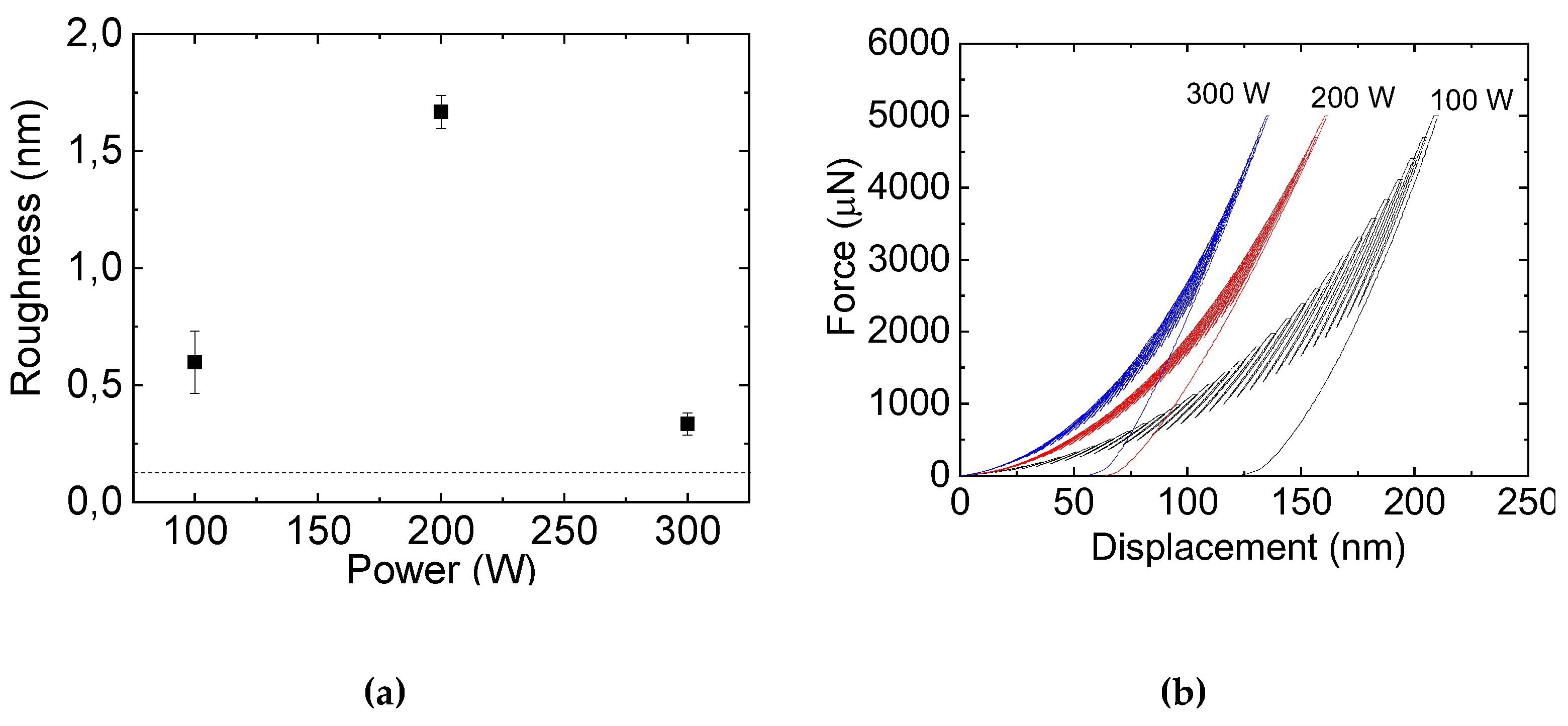

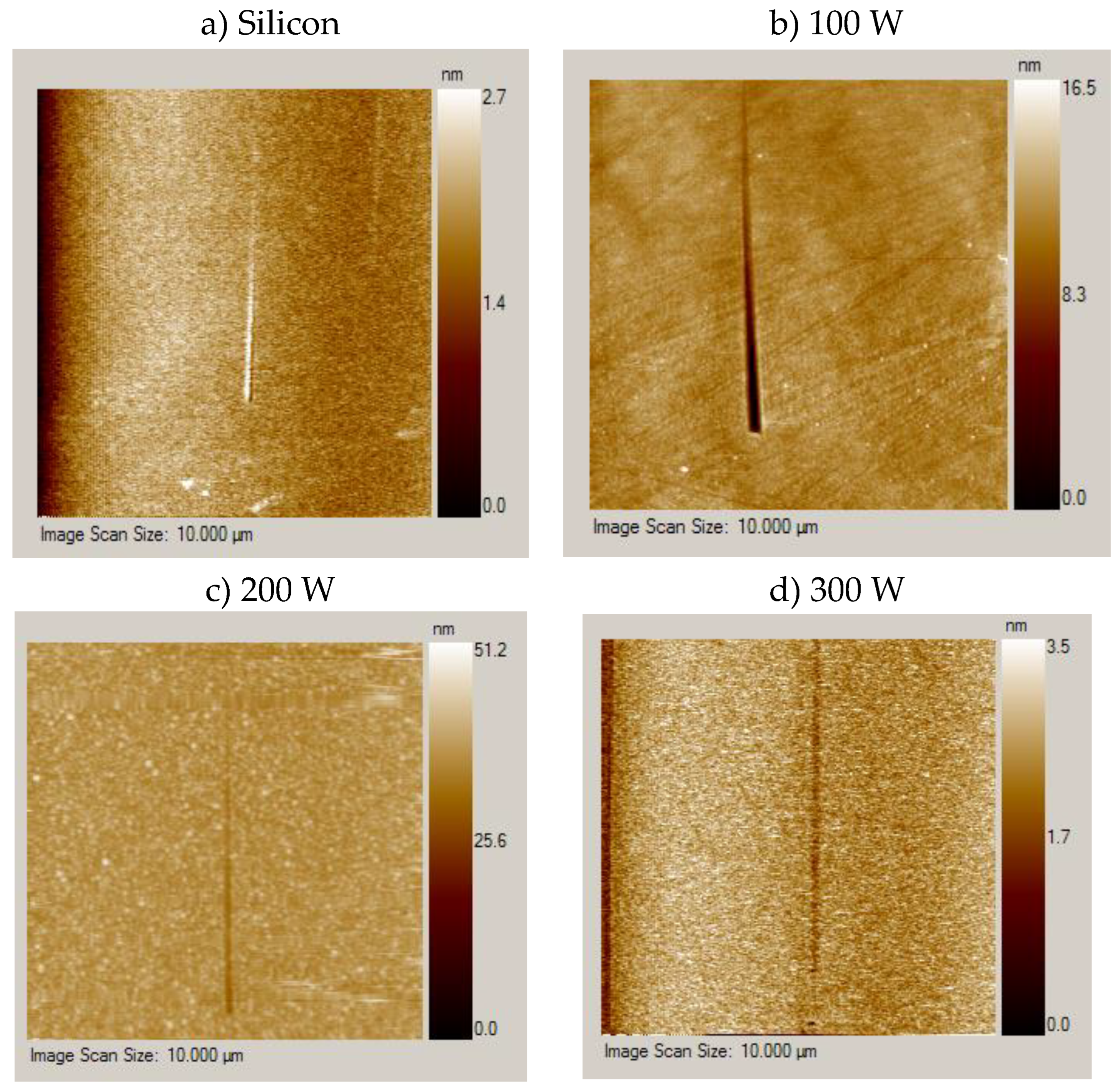

3.3. Surface Topography and Roughness

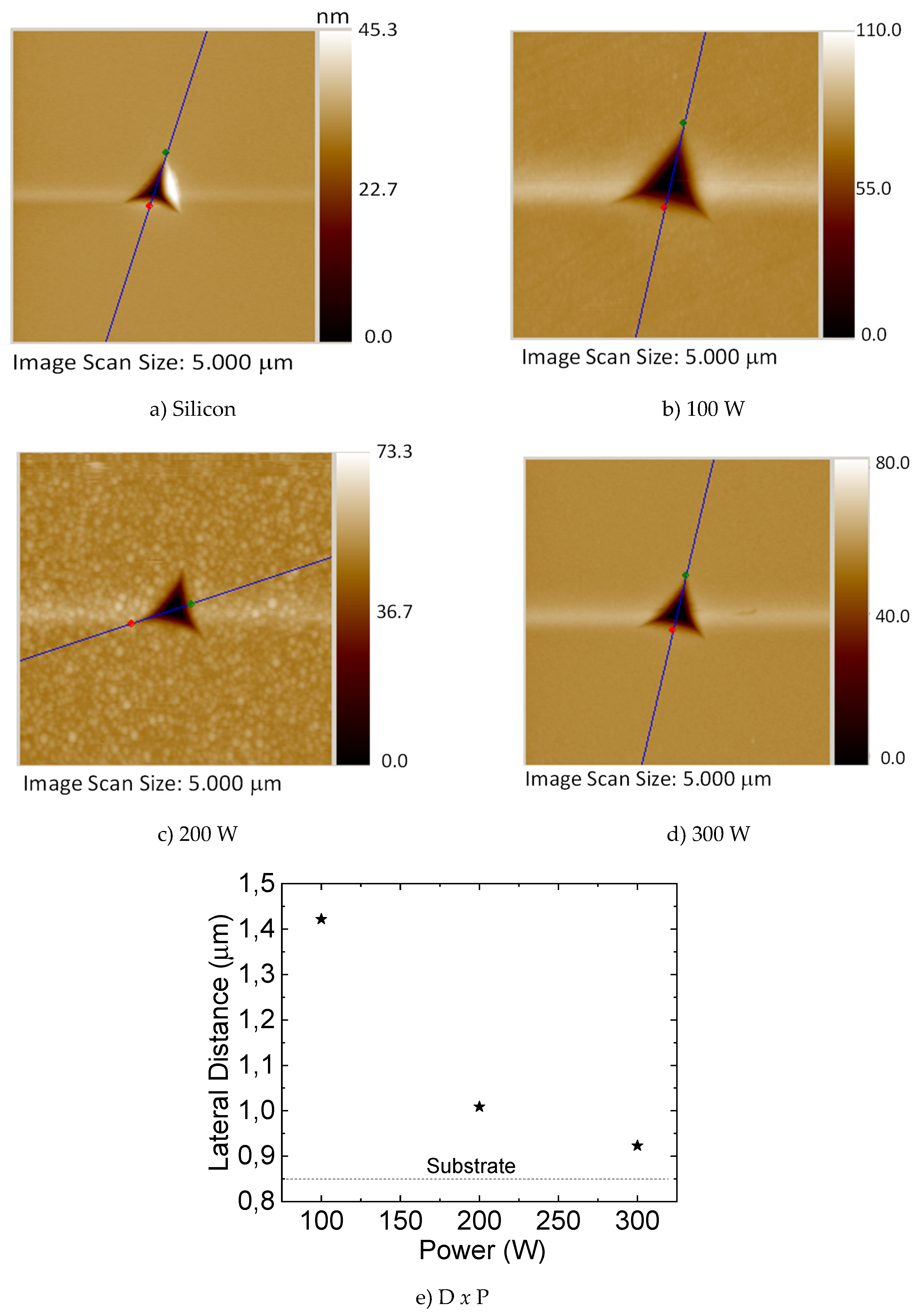

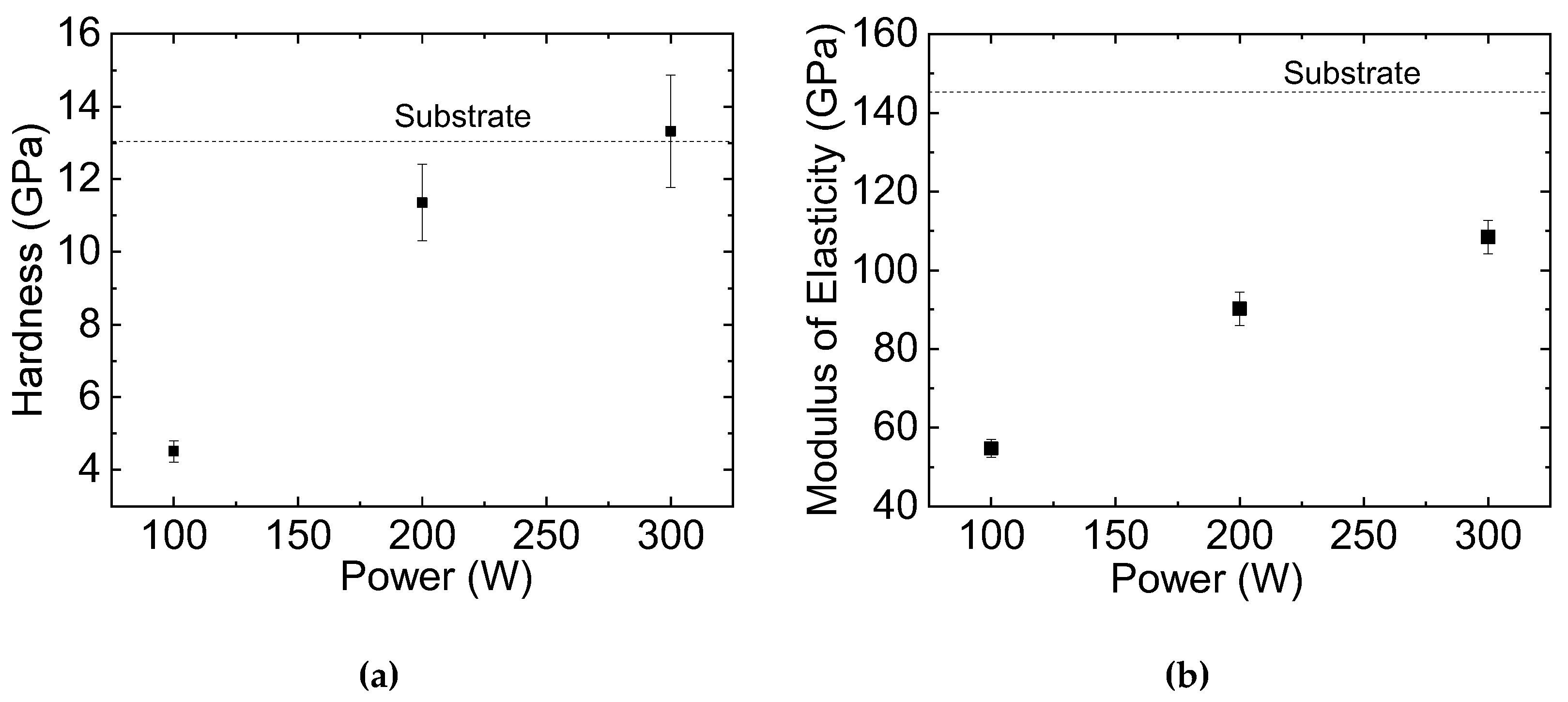

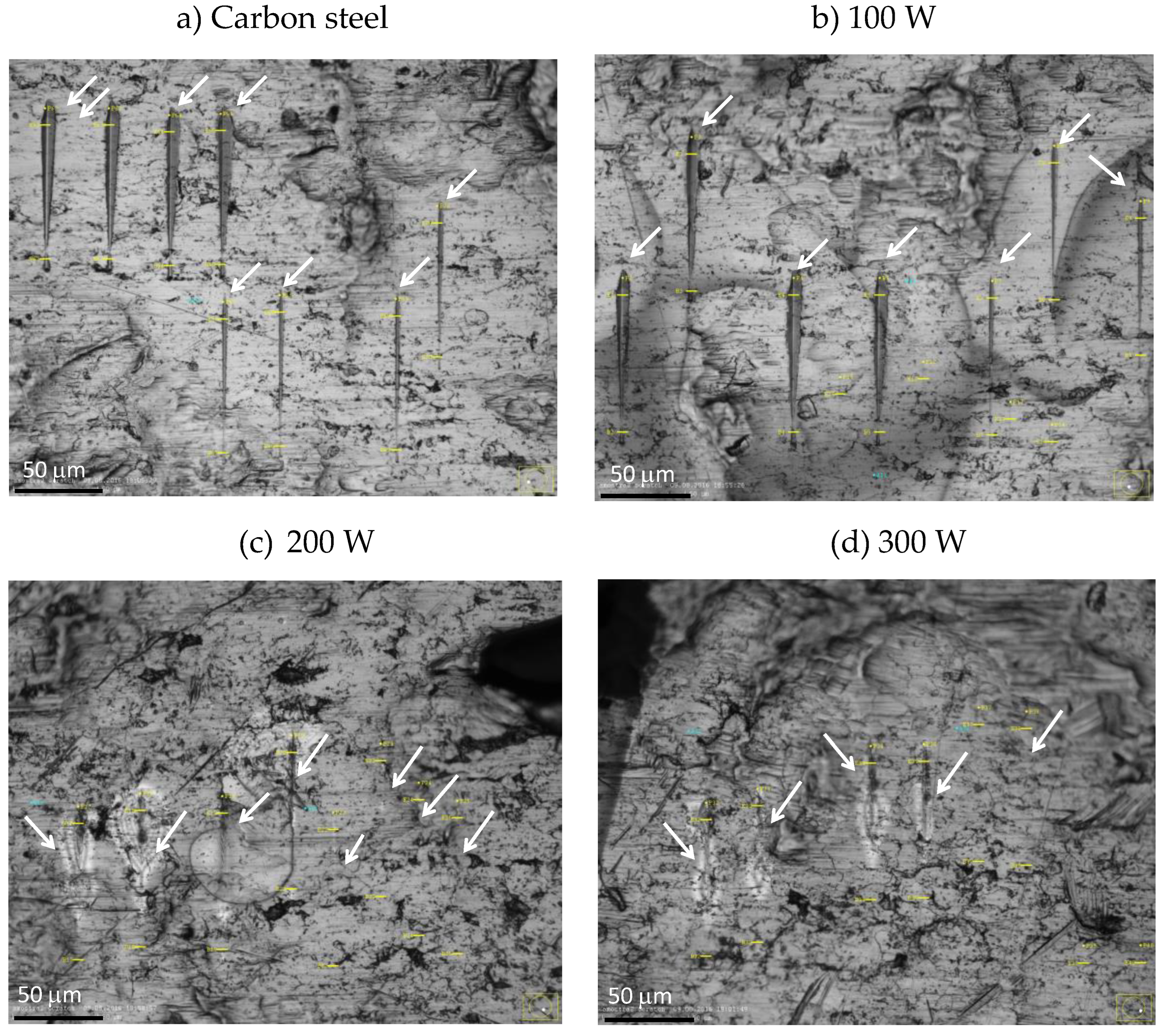

3.4. Mechanical and Tribological Properties

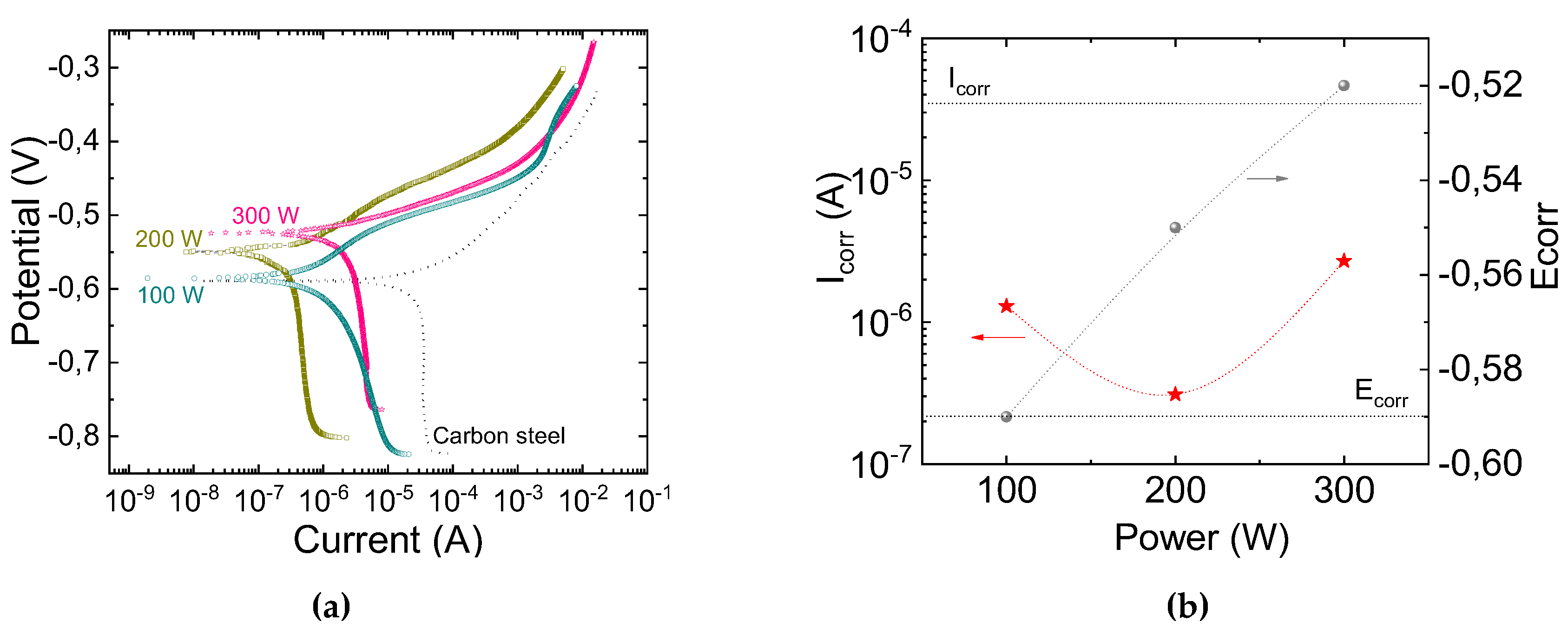

3.5. Barrier Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benítez, F.; Martínez, E.; Esteve, J. Improvement of Hardness in Plasma Polymerized Hexamethyldisiloxane Coatings by Silica-like Surface Modification. Thin Solid Films 2000, 377–378, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milella, A.; Creatore, M.; Blauw, M.A.; van de Sanden, M.C.M. Remote Plasma Deposited Silicon Sioxide-like Film Densification by Means of RF Substrate Biasing: Film Chemistry and Morphology. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2007, 4, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Lv, G.H.; Pang, H.; Zhang, G.P.; Yang, S.Z. Comparing Deposition of Organic and Inorganic Siloxane Films by the Atmospheric Pressure Glow Discharge. Surf Coat Technol 2012, 206, 2552–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, E.; Grassini, S.; Rosalbino, F.; Fracassi, F.; d’Agostino, R. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Evaluation of the Corrosion Behaviour of Mg Alloy Coated with PECVD Organosilicon Thin Film. Prog Org Coat 2003, 46, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, X. Surface Structures Tailoring of Hexamethyldisiloxane Films by Pulse Rf Plasma Polymerization. Mater Chem Phys 2006, 96, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimoldi, E.; Zanini, S.; Siliprandi, R.A.; Riccardi, C. AFM and Contact Angle Investigation of Growth and Structure of Pp-HMDSO Thin Films. European Physical Journal D 2009, 54, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Ji, L.; Ge, J.; Sadoway, D.R.; Yu, E.T.; Bard, A.J. Electrodeposition of Crystalline Silicon Films from Silicon Dioxide for Low-Cost Photovoltaic Applications. Nat Commun 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.N.; Chan, K.Y.; Tohsophon, T. Effects of Annealing Temperature on ZnO and AZO Films Prepared by Sol-Gel Technique. Appl Surf Sci 2012, 258, 9604–9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.C.; Chang, J.K.; Lin, C.S. The Influence of Aluminum Nitrate Pre-Treatment on High Temperature Oxidation Resistance Resistance of Dip-Coated Silica Coating on Galvanized Steel. J Chem Inf Model 2019, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.P.; Yang, J.H.; Yang, J.G.; Zhu, L.Y.; Huang, W.; Yuan, G.J.; Feng, J.J.; Jen, T.C.; Lu, H.L. Systematic Study of the SiOx Film with Different Stoichiometry by Plasma-Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition and Its Application in SiOx/SiO2 Super-Lattice. Nanomaterials 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, R.C.C.; Cruz, N.C.; Milella, A.; Fracassi, F.; Rangel, E.C. Barrier and Mechanical Properties of Carbon Steel Coated with SiOx/SiOxCyHz Gradual Films Prepared by PECVD. Surf Coat Technol 2019, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, R.; Hamed, Z. Ben; Gamra, D.; Lejeune, M.; Bouchriha, H. Optical Modeling and Investigation of Thin Films Based on Plasma-Polymerized HMDSO under Oxygen Flow Deposited by PECVD. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2023, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.P.; Kim, H.; Choi, J.; Oh, D.; Chung, Y. Bin; Jeon, W.S.; Jo, J.; Dao, V.A.; Dhungel, S.K.; Yi, J. In-Situ PECVD-Based Stoichiometric SiO2 Layer for Semiconductor Devices. Opt Mater (Amst) 2023, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubner, J.; Stellmann, L.; Mertens, A.K.; Tepper, M.; Roth, H.; Kleines, L.; Dahlmann, R.; Wessling, M. Organosilica Coating Layer Prevents Aging of a Polymer with Intrinsic Microporosity. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, E.; Pedroni, M.; Aloisio, M.; Chen, H.; Firpo, G.; Pietralunga, S.M.; Ripamonti, D. Plasma Deposition to Improve Barrier Performance of Biodegradable and Recyclable Substrates Intended for Food Packaging. Plasma 2022, 5, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zou, Y.; Lai, Q.; Tu, C.; Xiong, L.; Jin, C.; Sun, F.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yue, Z. In Situ Preparation of Double-Layered Si/SiOx Nano-Film as High Performance Anode Material for Lithium Ion Batteries. Solid State Sci 2023, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentil, V. Corrosão; 3rd ed.; LTC: Rio de Janeiro, 1996; ISBN 9788521618041. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, A.J.; Barve, S.A.; Chutia, J.; Pal, A.R.; Kishore, R.; Jagannath; Pande, M. ; Patil, D.S. RF-PACVD of Water Repellent and Protective HMDSO Coatings on Bell Metal Surfaces: Correlation between Discharge Parameters and Film Properties. Appl Surf Sci 2011, 257, 8469–8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vautrin-Ul, C.; Roux, F.; Boisse-Laporte, C.; Pastol, J.L.; Chausse, A. Hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDSO)-Plasma-Polymerised Coatings as Primer for Iron Corrosion Protection: Influence of RF Bias. J Mater Chem 2002, 12, 2318–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clergereaux, R.; Calafat, M.; Benitez, F.; Escaich, D.; Savin de Larclause, I.; Raynaud, P.; Esteve, J. Comparison between Continuous and Microwave Oxygen Plasma Post-Treatment on Organosilicon Plasma Deposited Layers: Effects on Structure and Properties. Thin Solid Films 2007, 515, 3452–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xia, Z.; Kong, X.; Xue, S.; Wang, H. Uniform Deposition of Silicon Oxide Film on Cylindrical Substrate by Radially Arranged Plasma Jet Array. Surf Coat Technol 2022, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.P.; Rangel, R.D.C.C.; Fernandes, F.O.; Cruz, N.C.; Rangel, E.C. Effect of Plasma Oxidation Treatment on Production of a SiOx/SiOxCyHz Bilayer to Protect Carbon Steel against Corrosion. Materials Research 2021, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Framil, D.; Van Gompel, M.; Bourgeois, F.; Furno, I.; Leterrier, Y. The Influence of Microstructure on Nanomechanical and Diffusion Barrier Properties of Thin PECVD SiOx Films Deposited on Parylene C Substrates. Front Mater 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajíkov, L.; Buríkov, V.; Kuerov, Z.; Franta, D.; Dvok, P.; Míd, R.; Peina, V.; MacKov, A. Deposition of Protective Coatings in Rf Organosilicon Discharges. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 2007, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, E.; d’Agostino, R.; Fracassi, F.; Grassini, S.; Rosalbino, F. Surface Analysis of PECVD Organosilicon Films for Corrosion Protection of Steel Substrates. Surface and Interface Analysis 2002, 34, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.J.; Chutia, J.; Kakati, H.; Barve, S.A.; Pal, A.R.; Sarma, N. Sen; Chowdhury, D.; Patil, D.S. Studies of Radiofrequency Plasma Deposition of Hexamethyldisiloxane Films and Their Thermal Stability and Corrosion Resistance Behavior. Vacuum 2010, 84, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit-Etienne, C.; Tatoulian, M.; Mabille, I.; Sutter, E.; Arefi-Khonsari, F. Deposition of SiOx-like Thin Films from a Mixture of HMDSO and Oxygen by Low Pressure and DBD Discharges to Improve the Corrosion Behaviour of Steel. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2007, 4, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patelli, A.; Vezzù, S.; Zottarel, L.; Menin, E.; Sada, C.; Martucci, A.; Costacurta, S. SiOx-Based Multilayer Barrier Coatings Produced by a Single PECVD Process. In Proceedings of the Plasma Processes and Polymers; 2009; Vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Perevalov, T. V.; Volodin, V.A.; Kamaev, G.N.; Krivyakin, G.K.; Gritsenko, V.A.; Prosvirin, I.P. Electronic Structure and Nanoscale Potential Fluctuations in Strongly Nonstoichiometric PECVD SiOx. J Non Cryst Solids 2020, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, E.; Cremona, A.; Laguardia, L.; Mesto, E. Preparation of Plasma-Polymerized SiOx-like Thin Films from a Mixture of Hexamethyldisiloxane and Oxygen to Improve the Corrosion Behaviour. Surf Coat Technol 2006, 200, 3035–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milella, A.; Creatore, M.; Milella, A.; Van De Sanden, M.C.M.; Tomozeiu, N. SiOx Structural Modifications by Ion Bombardment and Their Influence on Electrical Properties Catholytes for Intermediate Temperature Sodium Sulfur (IT-NaS) Battery View Project Atomic Layer Deposition Processes for Li-Ion Batteries: Novel Chemistries, Surface Reactions and Film Properties View Project SiO x Structural Modifications by Ion Bombardment and Their Influence on Electrical Properties; 2006; Vol. 8.

- Lefèvre, A.; Lewis, L.J.; Martinu, L.; Wertheimer, M.R. Structural Properties of Silicon Dioxide Thin Films Densified by Medium-Energy Particles. Phys Rev B Condens Matter Mater Phys 2001, 64, 1154291–1154299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, N.E.; Hanselmann, B.; Drosten, J.; Heuberger, M.; Hegemann, D. Densification and Hydration of HMDSO Plasma Polymers. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2015, 12, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, R.; Zanini, S.; Riccardi, C. Characterization of the Chemical Kinetics in an O2/HMDSO RF Plasma for Material Processing. Advances in Physical Chemistry 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. Measurement of Hardness and Elastic Modulus by Instrumented Indentation: Advances in Understanding and Refinements to Methodology; 2004; A.

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, G.Y.; Liu, B.; Jiang, C.C.; Lu, Y.P. Influence of Processing Time on the Phase, Microstructure and Electrochemical Properties of Hopeite Coating on Stainless Steel by Chemical Conversion Method. New Journal of Chemistry 2015, 39, 5813–5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wavhal, D.S.; Zhang, J.; Steen, M.L.; Fisher, E.R. Investigation of Gas Phase Species and Deposition of SiO2 Films from HMDSO/O2 Plasmas. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2006, 3, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendemiatti, C.; Hosokawa, R.S.; Rangel, R.C.C.; Bortoleto, J.R.R.; Cruz, N.C.; Rangel, E.C. Wettability and Surface Microstructure of Polyamide 6 Coated with SiOXCYHZ Films. Surf Coat Technol 2015, 275, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, S.F.; Mota, R.P.; de Moraes, M.A.B. Fluorinated Polymer Films from r.f. Plasmas Containing Benzene and Sulfur Hexafluorine. Thin Solid Films 1992, 220, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucovsky, G. Low-Temperature Growth of Silicon Dioxide Films: A Study of Chemical Bonding by Ellipsometry and Infrared Spectroscopy. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B: Microelectronics and Nanometer Structures 1987, 5, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassi, F.; d’Agostino, R.; Palumbo, F.; Angelini, E.; Grassini, S.; Rosalbino, F. Application of Plasma Deposited Organosilicon Thin Films for the Corrosion Protection of Metals. Surf Coat Technol 2003, 174–175, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.H.; Fleming, I. Spectroscopic Methods in Organic Chemistry; 1st ed.; McGraw Hill: London, 1966;

- Fanelli, F.; D’Agostino, R.; Fracassi, F. GC-MS Investigation of Hexamethyldisiloxane-Oxygen Fed Cold Plasmas: Low Pressure versus Atmospheric Pressure Operation. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2011, 8, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wavhal, D.S.; Zhang, J.; Steen, M.L.; Fisher, E.R. Investigation of Gas Phase Species and Deposition of SiO2 Films from HMDSO/O2 Plasmas. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2006, 3, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, R.C.C.; Cruz, N.C.; Rangel, E.C. Role of the Plasma Activation Degree on Densification of Organosilicon Films. Materials 2020, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benissad, N.; Boisse-Laporte, C.; Vallée, C. ; Granier, a; Goullet, a Silicon Dioxide Deposition in a Microwave Plasma Reactor. Surf Coat Technol 1999, 116–119, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coclite, A.M.; Milella, A.; Palumbo, F.; Le Pen, C.; D’Agostino, R. Plasma Deposited Organosilicon Multistacks for High-Performance Low-Carbon Steel Protection. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2010, 7, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tochitani, G.; Shimozuma, M.; Tagashira, H. Deposition of Silicon Oxide Films from TEOS by Low Frequency Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A: Vacuum, Surfaces, and Films 1993, 11, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.R.; Short, R.D.; Jones, F.R.; Michaeli, W.; Blomfield, C.J. A Study of HMDSO/O2 Plasma Deposits Using a High-Sensitivity and -Energy Resolution XPS Instrument: Curve Fitting of the Si 2p Core Level. Appl Surf Sci 1999, 137, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.B.; Kim, S.I.; Choi, Y.S.; Choi, I.S.; Han, J.G. Effect of Bipolar Pulsed Dc Bias on the Mechanical Properties of Silicon Oxide Thin Film by Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition. Current Applied Physics 2011, 11, 1107–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, F.; Qiang, C.; Zhongwei, L.; Fuping, L.; Solodovnyk, A. The Application of Nano-Siox Coatings as Migration Resistance Layer by Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing 2012, 32, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Liu, C.H.; Wu, S.Y. Surface Characterization of the SiOx Films Prepared by a Remote Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet. Surface and Interface Analysis 2009, 41, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Liu, C.H.; Su, C.H.; Chen, H. Atmospheric-Pressure Plasma Deposition of SiOx Films for Super-Hydrophobic Application. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517, 5284–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, W.; Qiang, C. Investigation of Microwave Surface-Wave Plasma Deposited SiO x Coatings on Polymeric Substrates ∗. Plasma Science and Technology 2014, 16, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, C.; MacKay, J.F.; Savage, D.E.; Lagally, M.G.; Brohl, M.; Wagner, P. Comparison of Surface Roughness of Polished Silicon Wafers Measured by Light Scattering Topography, Soft-x-Ray Scattering, and Atomic-Force Microscopy. Appl Phys Lett 1995, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OPUS by uMASCH. Roughness of Si Wafer.

- Naganuma, Y.; Horiuchi, T.; Kato, C.; Tanaka, S. Low-Temperature Synthesis of Silica Coating on a Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Film from Perhydropolysilazane Using Vacuum Ultraviolet Light Irradiation. Surf Coat Technol 2013, 225, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.; Elias, J.; Erni, R.; Parlinska, M.; Philippe, L.; Michler, J. Mechanical Behavior of Intragranular, Nano-Porous Electrodeposited Zinc Oxide. Thin Solid Films 2015, 578, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekaya, A.; Ghulman, H.A.; Benameur, T.; Labdi, S. Cyclic Nanoindentation and Finite Element Analysis of Ti/TiN and CrN Nanocoatings on Zr-Based Metallic Glasses Mechanical Performance. J Mater Eng Perform 2014, 23, 4259–4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhang, X. Nanoindentation Creep of Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposited Silicon Oxide Thin Films. Scr Mater 2007, 56, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Chen, Z.K.; Shen, L.; Liu, B. Study of Mechanical Properties of Light-Emitting Polymer Films by Nano-Indentation Technique. In Proceedings of the Thin Solid Films; April 22 2005; Vol. 477, pp. 111–118.

- Martinatti, J.F.; Santos, L. V.; Durrant, S.F.; Cruz, N.C.; Rangel, E.C. Lubricating Coating Prepared by PIIID on a Forming Tool. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; Institute of Physics Publishing, 2012; Vol. 370.

- Charitidis, C.A.; Kassavetis, S.; Logothetidis, S. Nanomechanical and Nanotribological Properties of Silicon Oxide Thin Films on Polymeric Membranes.

- Jin, S.B.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y.S.; Choi, I.S.; Han, J.G. High-Rate Deposition and Mechanical Properties of SiOx Film at Low Temperature by Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition with the Dual Frequencies Ultra High Frequency and High Frequency. Thin Solid Films 2011, 519, 6334–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Coclite, A.; De Luca, F.; Gleason, K.K. Mechanically Robust Silica-like Coatings Deposited by Microwave Plasmas for Barrier Applications. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A: Vacuum, Surfaces, and Films 2012, 30, 061502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.G.; Lawn, B.R.; Martyniuk, M.; Huang, H.; Hu, X.Z. Evaluation of Elastic Modulus and Hardness of Thin Films by Nanoindentation. J Mater Res 2004, 19, 3076–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, B.B.; Rangel, R.C.C.; Antonio, C.A.; Durrant, S.F.; Cruz, N.C.; Rangel, E.C. Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Plasma Deposited A-C : H : Si : O Films. In Nanoindentation in Materials Science; Nemeck, J., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, 2012; pp. 179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, M.A.; Khaled, K.F.; Mohsen, Q.; Arida, H.A. A Study of the Inhibition of Iron Corrosion in HCl Solutions by Some Amino Acids. Corros Sci 2010, 52, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delimi, A.; Galopin, E.; Coffinier, Y.; Pisarek, M.; Boukherroub, R.; Talhi, B.; Szunerits, S. Investigation of the Corrosion Behavior of Carbon Steel Coated with Fluoropolymer Thin Films. Surf Coat Technol 2011, 205, 4011–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, C.B.; Ueda, M.; Oliveira, R.M.; Garcia, J.A. Corrosion Effects of Plasma Immersion Ion Implantation-Enhanced Cr Deposition on SAE 1070 Carbon Steel. Surf Coat Technol 2011, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Tang, H. Microstructure and Corrosion Resistance of Ceramic Coating on Carbon Steel Prepared by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation. Surf Coat Technol 2010, 204, 1685–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wavenumbers (cm-1) | Vibrational Modes |

| 445 | Si-O-Si (rocking) |

| 815 | Si-O-Si (bending) |

| 935 | OH in Si-OH (stretching) |

| 1062 | Si-O-Si in SiOx (stretching) |

| 3500 | OH in Si-OH (stretching) |

| Atomic Proportion | ||||

| Plasma Excitation Power (W) | C (% ) | O (% ) | Si (% ) | O/Si |

| 100 | 0.9 | 63.9 | 35.2 | 1.8 |

| 200 | 0.0 | 64.3 | 35.0 | 1.8 |

| 300 | 1.0 | 64.0 | 33.9 | 1.9 |

| Plasma Excitation Power (W) | Si-O4 (103.4 eV) |

Si-O2 (102.0 eV) |

Si-O1 (101.5 eV) |

| 100 | 92.3 | 7.7 | - |

| 200 | 91.6 | 8.4 | - |

| 300 | 98.5 | - | 1.5 |

| P (W) | Porosity (%) |

| 100 | 0.096 |

| 200 | 0.002 |

| 300 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).