Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

During early embryogenesis, the trilaminar germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—undergo complex topological transformations and molecular interactions that define tissue differentiation. The ectoderm, which gives rise to the central nervous system and epidermis, exhibits developmental pathways closely tied to morphogenetic gradients and folding dynamics. This study explores how shared topological features and signalling pathways across germ layers can generate resembling pathologies under comparable disruptions, such as neurocutaneous syndromes and craniofacial anomalies. By integrating concepts from developmental biology and topological data analysis, this work provides a theoretical framework to understand the intersection of embryonic topology and disease etiology, offering insights into novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Keywords:

Section 1. Introduction

Section 1.1. Topological Mechanisms Linking Pathologies

Section 1.2. The Neural Tube: A Paradigm of Topological Complexity

Section 1.3. Craniofacial Development: Interactions and Fusion

Section 1.4. Segmentation and the Emergence of Patterns

Section 1.5. Folding and Closure: The Creation of Body Cavities

Section 1.7. Implications and Future Directions

Section 2. Methodology

Section 2.1. A Theoretical Framework with Mathematical Foundations

- 1.

- Manifold Representation of Germ Layers

- 2.

- Topological Transformations and Critical Points

- Minima: Local regions of invagination.

- Maxima: Local regions of expansion.

- Saddle points: Fold or closure sites.

- 3.

- Interaction Between Germ Layers

- 4.

- Persistence of Topological Features

- 5.

- Pathological Disruptions

- 6.

- Theoretical Proof of Shared Origins

- Neural tube defects (NTDs) correspond to persistent cycles in , reflecting failed closure.

- Craniofacial anomalies involve persistent cycles spanning and , reflecting ectoderm-mesoderm interactions.

- 7.

- Conclusion of the Proof

Section 2.2.

Sectio 3. Results

Section 3.1. Graphs Overview:

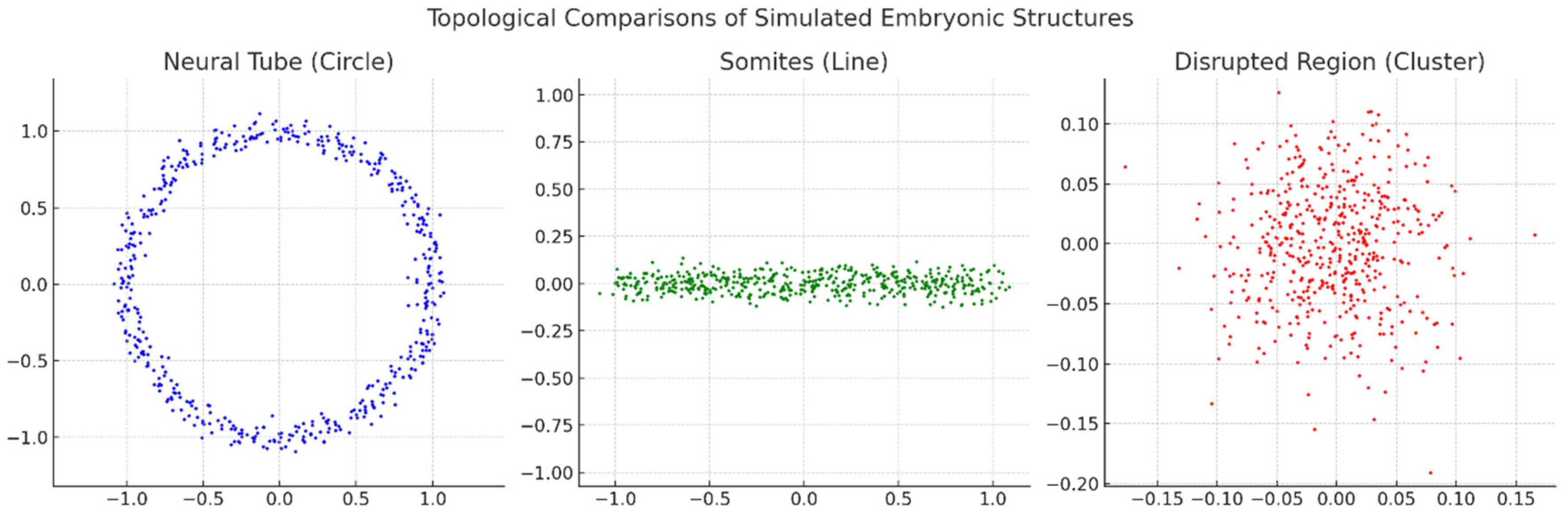

-

Neural Tube (Circle):

- ○

- The data points form a clear circular structure, representing the topology of a neural tube during embryonic development. This pattern signifies continuity and loop-like formation typical of such biological structures.

-

Somites (Line):

- ○

- The data points align in a linear configuration, symbolising somite development, which is segmental and elongated. This topological representation highlights a linear structure.

-

Disrupted Region (Cluster):

- ○

- The data points are scattered without a clear geometric or topological form, suggesting a disrupted or irregular developmental region. This randomness indicates a breakdown or abnormality in the structure.

Section 3.2. Explanation:

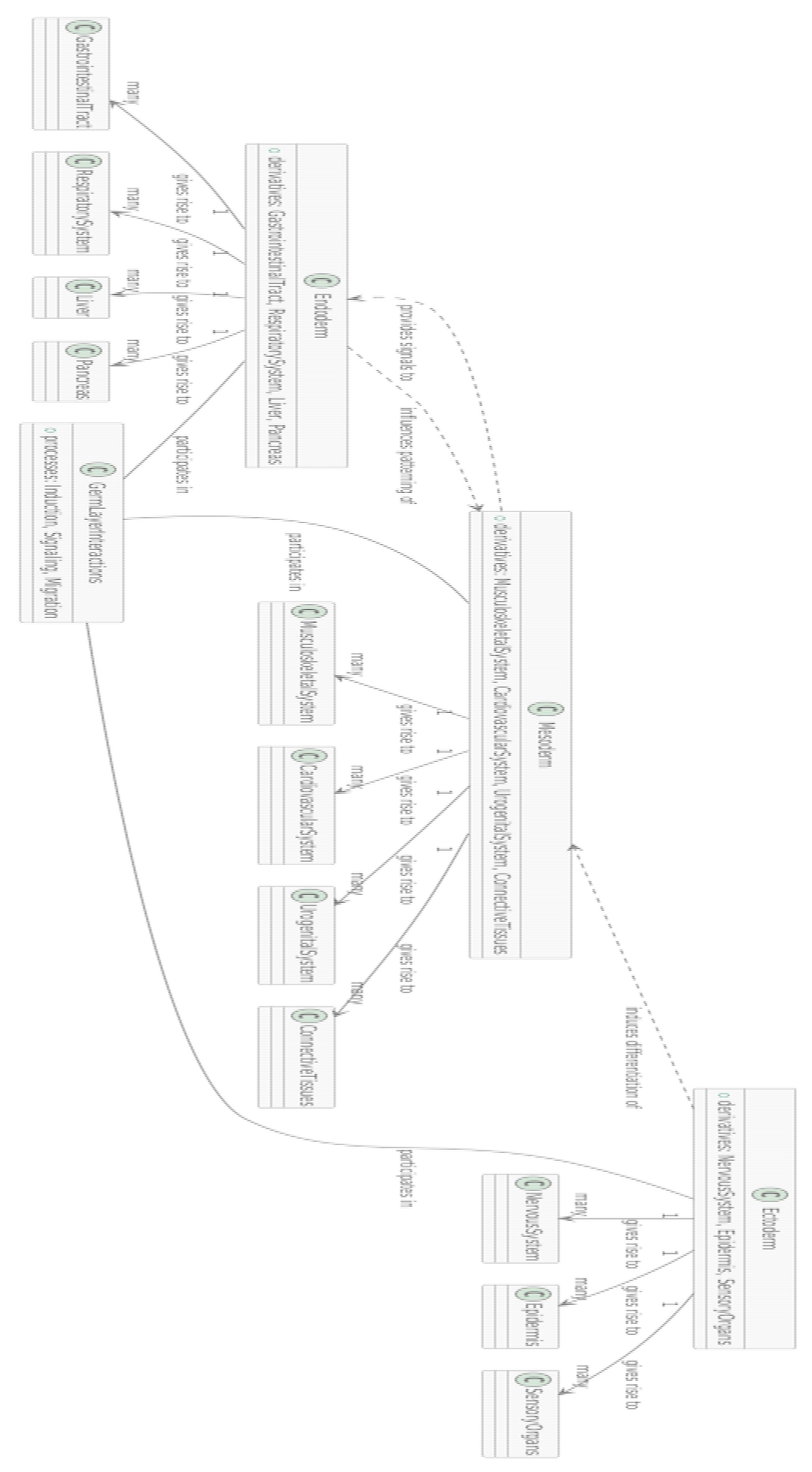

-

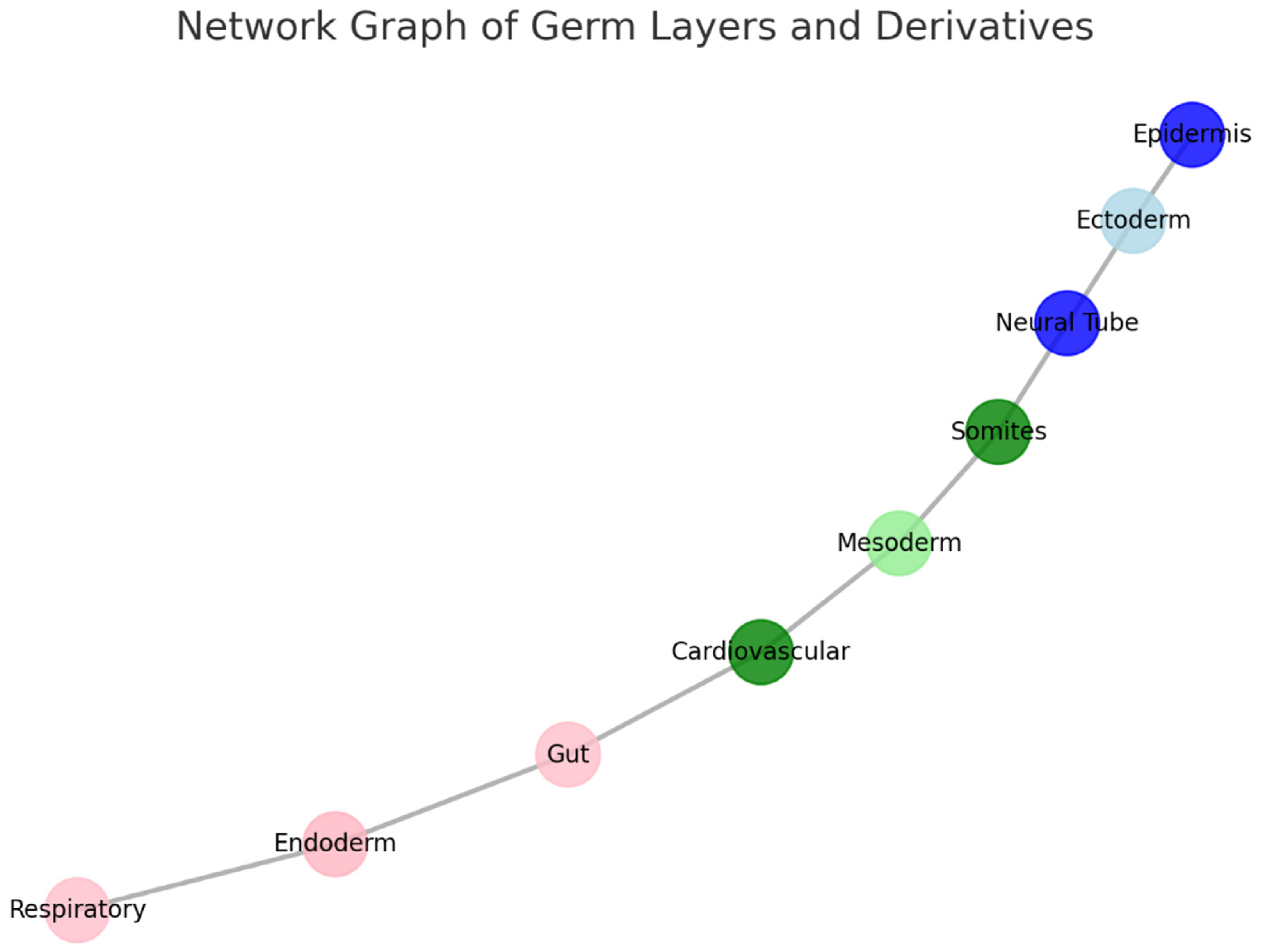

Nodes:

- ○

-

Ectoderm (light blue) and its derivatives:

- ▪

- Neural Tube (blue): Develops into the central nervous system.

- ▪

- Epidermis (dark blue): Forms the outer skin layer.

- ○

-

Mesoderm (green shades) and its derivatives:

- ▪

- Somites (green): Give rise to skeletal muscles and vertebrae.

- ▪

- Cardiovascular system (dark green): Includes the heart and blood vessels.

- ○

-

Endoderm (pink shades) and its derivatives:

- ▪

- Gut (red-pink): Forms the digestive tract.

- ▪

- Respiratory system (light pink): Includes the lungs and airways.

-

Edges:

- ○

- The lines between nodes represent developmental pathways or relationships, tracing how germ layers differentiate into specific structures.

Section 3.3. Explanation of Each Plot:

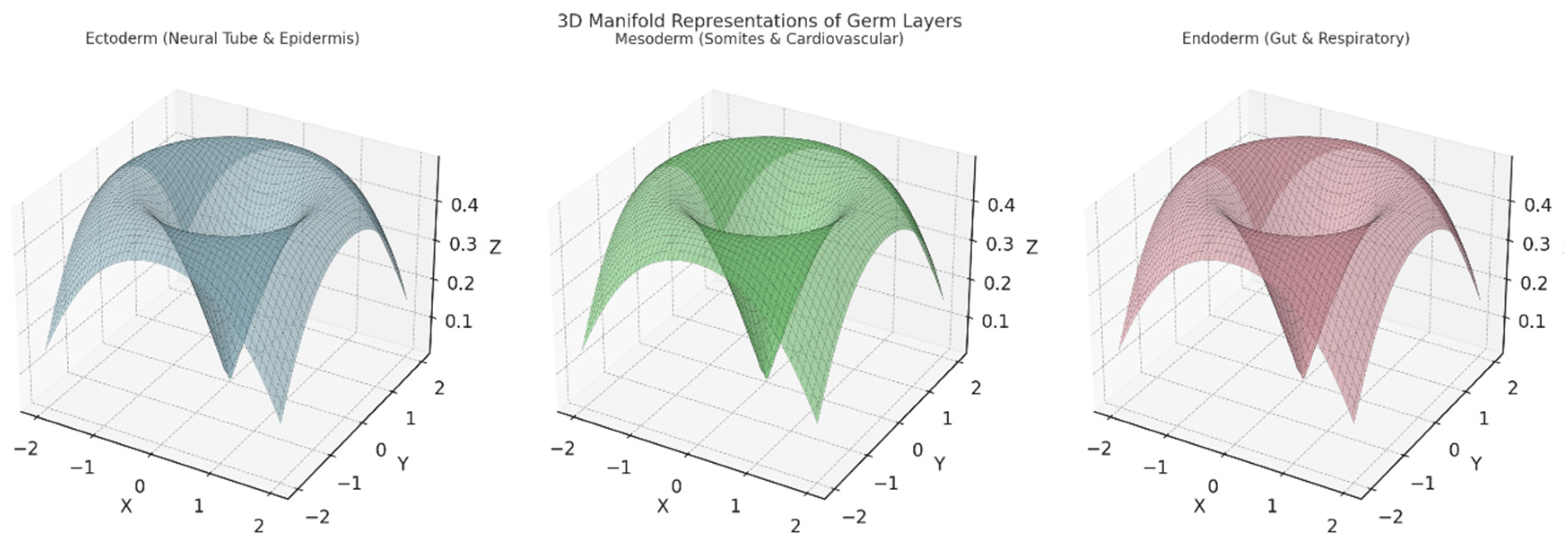

-

Left Plot: Ectoderm (Neural Tube & Epidermis):

- ○

- A 3D surface representing the ectoderm and its derivatives (e.g., neural tube and epidermis).

- ○

- The structure suggests branching and separation into distinct pathways for neural and epidermal development.

- ○

-

Axes:

- ▪

- X,YX, YX,Y: Represent spatial or topological coordinates.

- ▪

- ZZZ: Encodes aspects of differentiation or development over time.

-

Middle Plot: Mesoderm (Somites & Cardiovascular):

- ○

- Depicts the 3D topology of the mesoderm and its derivatives, including somites (segments) and the cardiovascular system.

- ○

- This manifold is smoother and broader, symbolising the more diverse range of tissues formed by the mesoderm.

- ○

-

Axes:

- ▪

- Similar spatial or developmental coordinates (X,Y, Z,X, Y, ZX, Y,Z).

-

Right Plot: Endoderm (Gut & Respiratory):

- ○

- Represents the endoderm's contribution to forming the gut and respiratory system.

- ○

- The surface exhibits a more funnel-shaped topology, indicating internalisation processes like tube formation for the digestive and respiratory tracts.

-

Topological Differences:

- ○

- The ectoderm's shape reflects branching for neural and external layers.

- ○

- The mesoderm's smoothness indicates the spread into multiple structures.

- ○

- The endoderm's inward topology corresponds to tube-like organ formation.

-

Interpretation:

- ○

- These manifolds highlight the spatial and developmental pathways, visually encoding differentiation patterns among the germ layers.

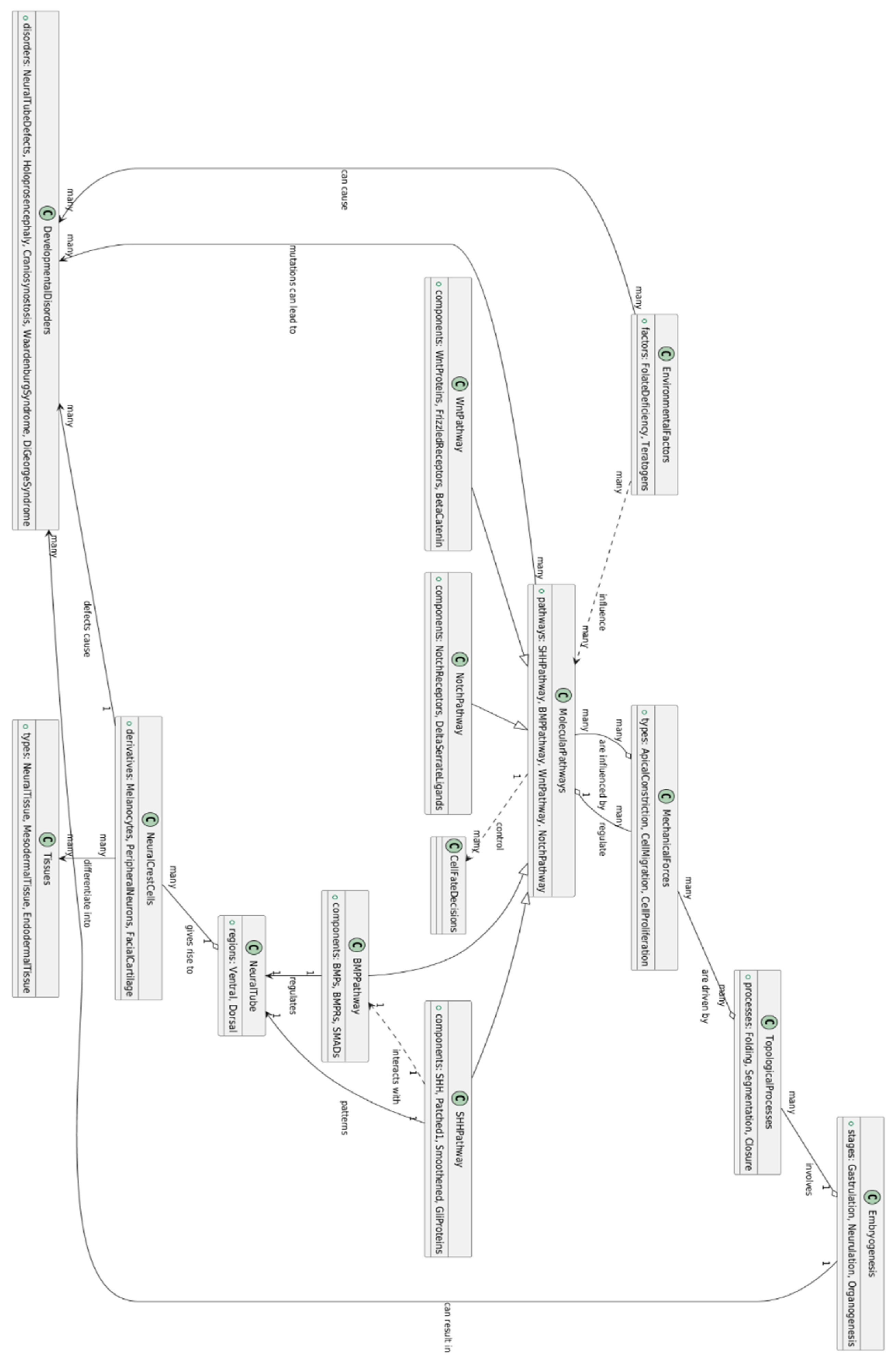

Section 3.4. Explanation

Section 3.5. Explanation

Section 4. Discussion

Section 4.1 Embryogenesis: The Interrelations between Topology, Molecular Pathways, and Developmental Disorders

Section 4.2. The Role of Topology in Embryogenesis

Section 4.4. Molecular Pathways as Orchestrators of Topology

Section 4.5. Clinical Implications and Future Perspectives

Section 5. Conclusion

References

- Anderson, R. M., Lawrence, A. R., Stottmann, R. W., Bachiller, D., & Klingensmith, J. (2006). Chordin and noggin promote organizing centers of forebrain development in the mouse. Development, 133(21), 4935–4947. [CrossRef]

- Berry, R. J., Li, Z., Erickson, J. D., et al. (1999). Prevention of neural-tube defects with folic acid in China. New England Journal of Medicine, 341(20), 1485–1490. [CrossRef]

- Blom, H. J., Shaw, G. M., den Heijer, M., & Finnell, R. H. (2006). Neural tube defects and folate: case far from closed. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7(9), 724–731. [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, J., & Novitch, B. G. (2008). Regulatory pathways linking progenitor patterning, cell fates, and neurogenesis in the ventral neural tube. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363(1489), 57–70. [CrossRef]

- Brodland, G. W., & Veldhuis, J. H. (2006). Computer simulations of convergent extension: Cell rearrangements and tissue mechanical properties. Developmental Biology, 303(1), 256–270.

- Bronner, M. E., & LeDouarin, N. M. (2012). Development and evolution of the neural crest: an overview. Developmental Biology, 366(1), 2–9. [CrossRef]

- Colas, J. F., & Schoenwolf, G. C. (2001). Towards a cellular and molecular understanding of neurulation. Developmental Dynamics, 221(2), 117–145. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M. J., Marazita, M. L., Beaty, T. H., & Murray, J. C. (2011). Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nature Reviews Genetics, 12(3), 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Doudna, J. A., & Charpentier, E. (2014). The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science, 346(6213), 1258096. [CrossRef]

- Edelsbrunner, H., & Harer, J. (2010). Computational Topology: An Introduction. American Mathematical Society.

- Greene, N. D., & Copp, A. J. (2009). Development of the vertebrate central nervous system: formation of the neural tube. Prenatal Diagnosis, 29(4), 303–311. [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, D. H., Ferner, R. E., Listernick, R. H., Korf, B. R., Wolters, P. L., & Johnson, K. J. (2017). Neurofibromatosis type 1. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 3, 17004. [CrossRef]

- Haigo, S. L., Hildebrand, J. D., Harland, R. M., & Wallingford, J. B. (2003). Shroom induces apical constriction and is required for hingepoint formation during neural tube closure. Current Biology, 13(24), 2125–2137. [CrossRef]

- McDonald-McGinn, D. M., Sullivan, K. E., Marino, B., et al. (2015). 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1, 15071.

- McMahon, J. A., Takada, S., Zimmerman, L. B., et al. (1998). Noggin-mediated antagonism of BMP signaling is required for growth and patterning of the neural tube and somite. Genes & Development, 12(10), 1438–1452. [CrossRef]

- Muenke, M., Beachy, P. A., & Rosenthal, A. (2004). Therapeutic implications of possible genetic and teratogenic interactions in holoprosencephaly. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 16(6), 614–621.

- Oates, A. C., Morelli, L. G., & Ares, S. (2012). Patterning embryos with oscillations: structure, function and dynamics of the vertebrate segmentation clock. Development, 139(4), 625–639. [CrossRef]

- Read, A. P., & Newton, V. E. (1997). Waardenburg syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics, 34(8), 656–665. [CrossRef]

- Riddle, R. D., Johnson, R. L., Laufer, E., & Tabin, C. (1993). Sonic hedgehog mediates the polarizing activity of the ZPA. Cell, 75(7), 1401–1416. [CrossRef]

- Roessler, E., & Muenke, M. (2010). The molecular genetics of holoprosencephaly. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 154C(1), 52–61. [CrossRef]

- Shore, E. M., Xu, M., Feldman, G. J., et al. (2006). A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nature Genetics, 38(5), 525–527. [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, D. B., Chapman, G., & Dunwoodie, S. L. (2012). The mouse notches up another success: understanding the causes of human vertebral malformation. Mammalian Genome, 23(1-2), 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J., Mai, C. T., Mulinare, J., et al. (2015). Updated estimates of neural tube defects prevented by mandatory folic acid fortification—United States, 1995–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(1), 1–5.

- Wilkie, A. O., & Morriss-Kay, G. M. (2001). Genetics of craniofacial development and malformation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2(6), 458–468. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., & Bradley, A. (1996). Mice deficient for BMP2 are nonviable and have defects in amnion/chorion and cardiac development. Development, 122(10), 2977–2986.

- Copp, A. J., Greene, N. D. E., & Murdoch, J. N. (2003). The genetic basis of mammalian neurulation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 4(10), 784–793. [CrossRef]

- Greene, N. D. E., & Copp, A. J. (2014). Neural tube defects. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 37, 221–242. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M. J., Marazita, M. L., Beaty, T. H., & Murray, J. C. (2011). Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nature Reviews Genetics, 12(3), 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y., Xu, J., & Jiang, R. (2015). Neural crest cells regulate FGF-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during palatal development. Science Signaling, 8(404), ra89. [CrossRef]

- Oates, A. C., Morelli, L. G., & Ares, S. (2012). Patterning embryos with oscillations: Structure, function and dynamics of the vertebrate segmentation clock. Development, 139(4), 625–639. [CrossRef]

- Clugston, R. D., & Klatt, J. (2010). Embryogenesis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery, 19(2), 82–90. [CrossRef]

- Trainor, P. A. (2010). Neural crest cells: Evolution, development, and disease. Developmental Biology, 344(1), 3–6. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).