Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Instruments

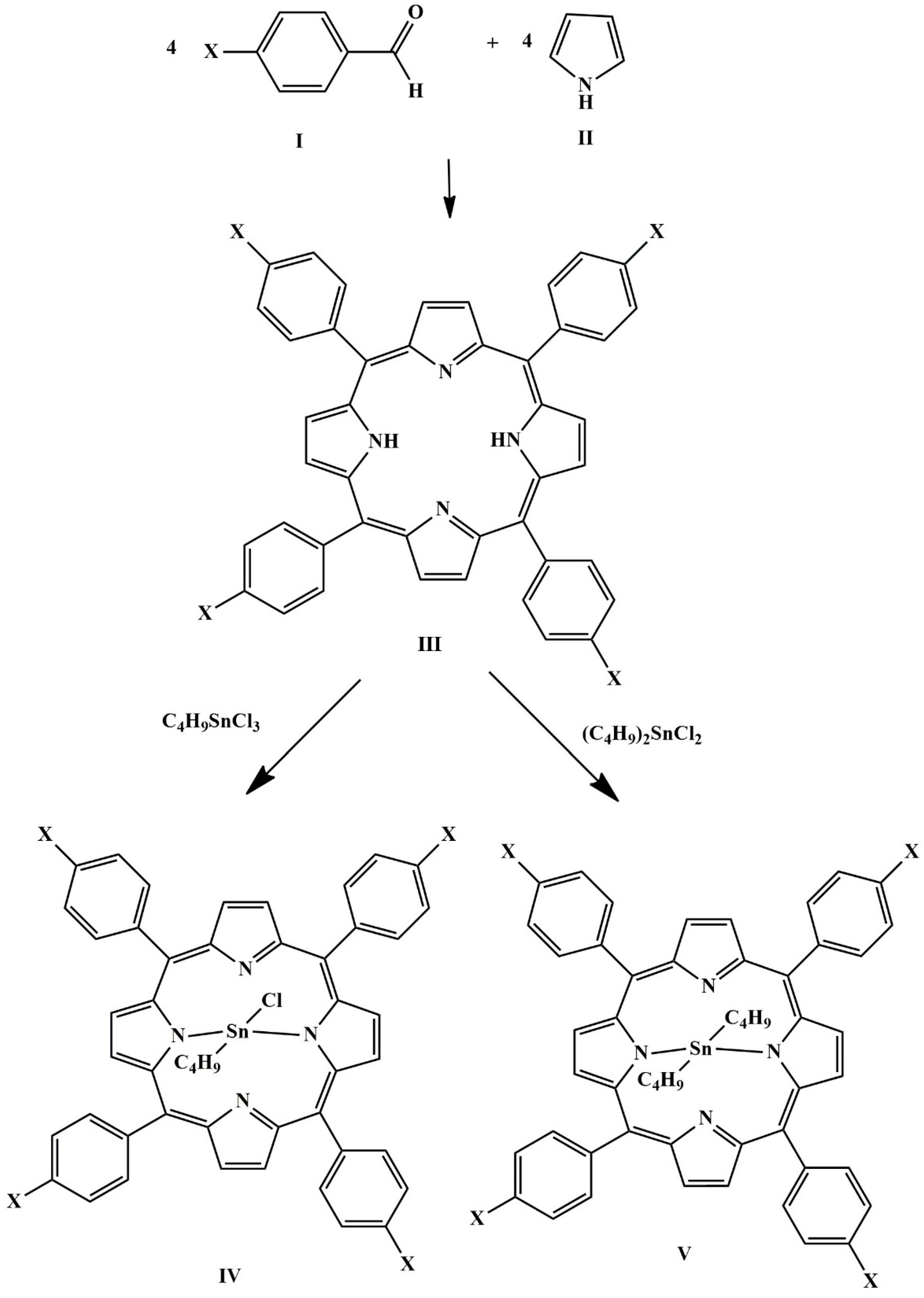

2.2. Preparation of 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-methoxyphenyl)porphyrin (TMOPPH2)

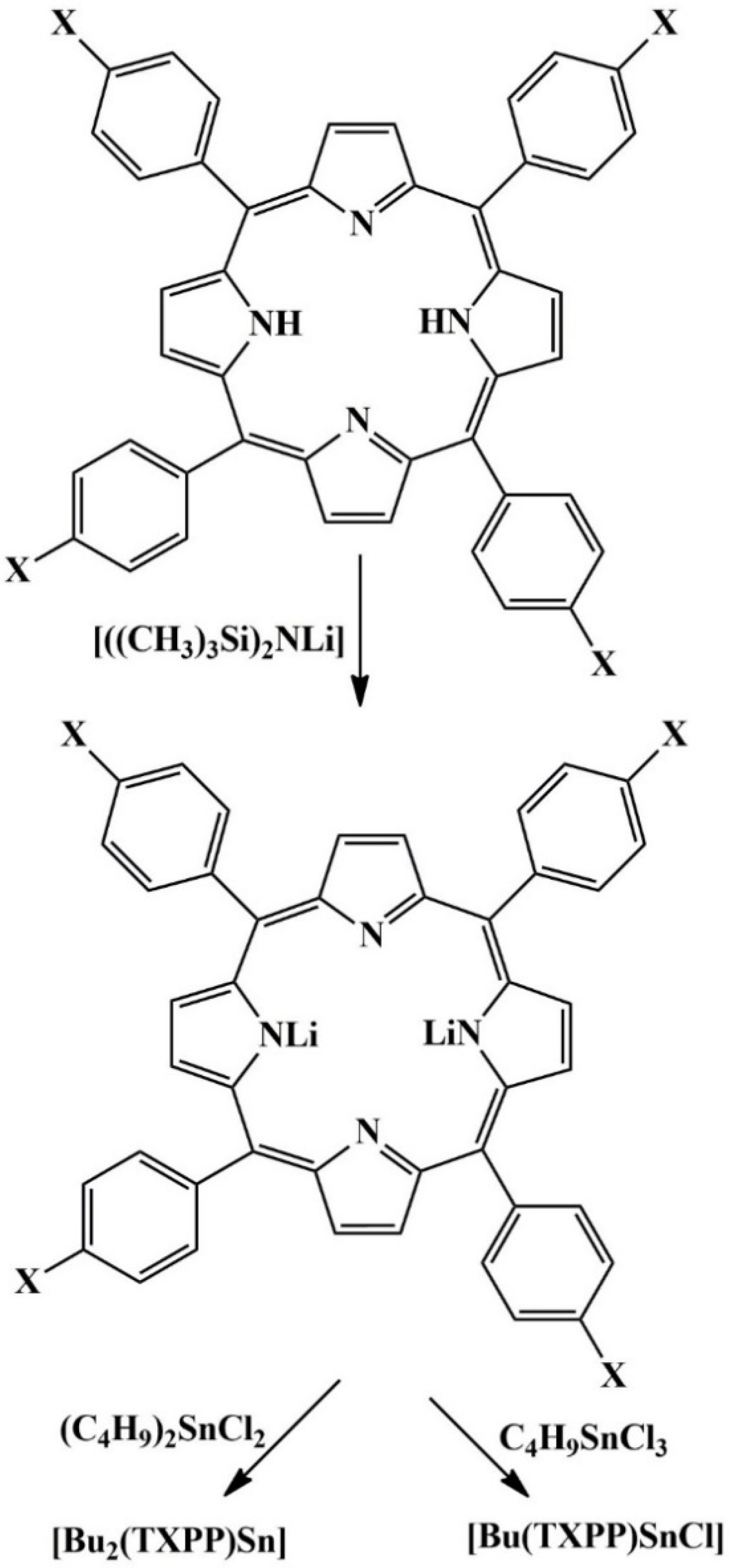

2.3. Preparation of Butyl(5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-methoxyphenyl)porphyrinato)tin(IV) Chloride, [Bu(TMOPP)SnCl]

2.4. Preparation of Dibutyl(5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-methoxyphenyl)porphyrinato)tin(IV), [Bu2Sn(TMOPP)]

2.5. Preparation of (5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-methoxyphenyl)porphyrinato)lithium(I), [Li2(TMOPP)]

2.6. Preparation of Dibutyl(5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-methoxyphenyl)porphyrinato)tin (IV) from[Li2(TMOPP)]

2.7. Adsorption Studies

3. Results and Discussions

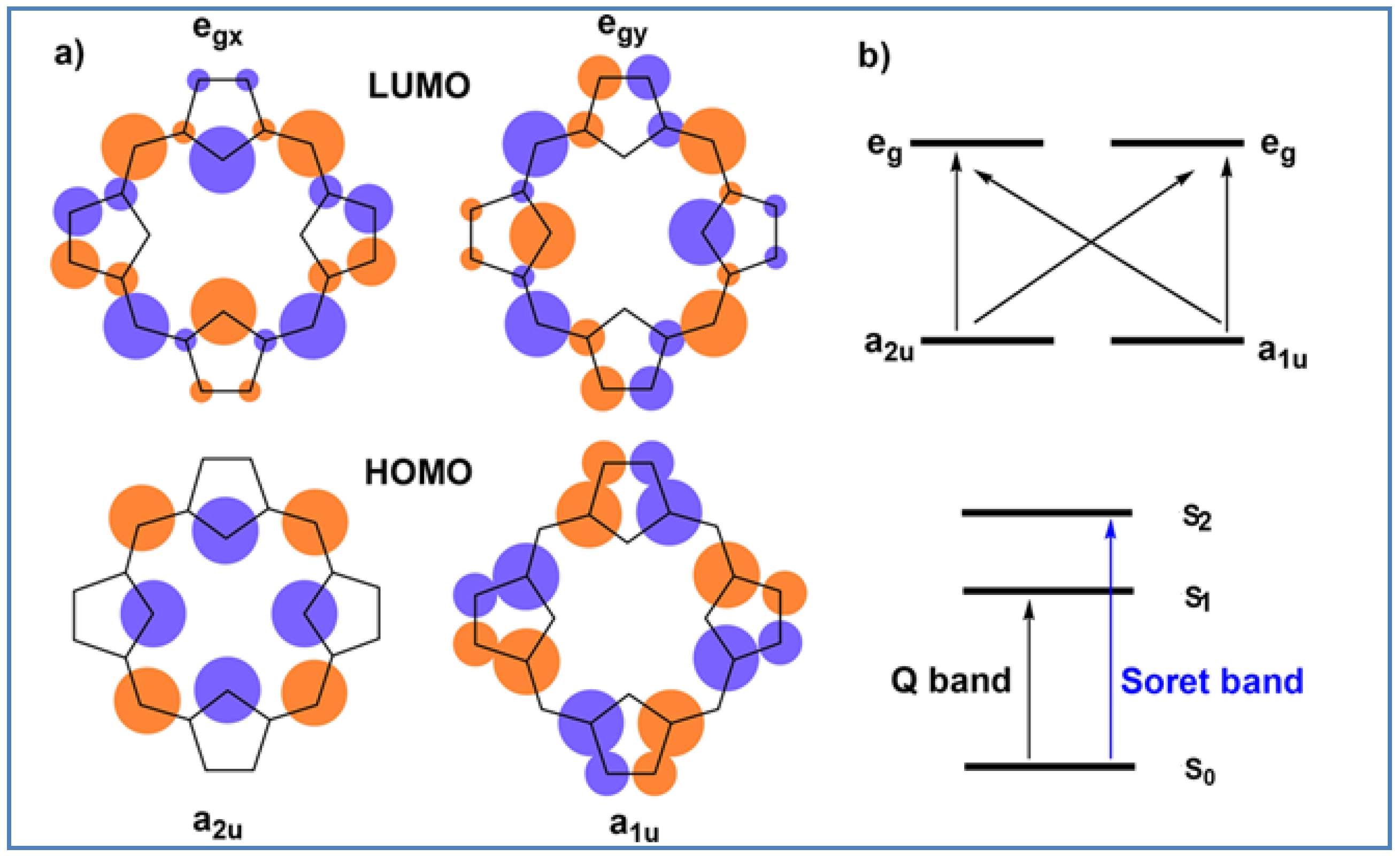

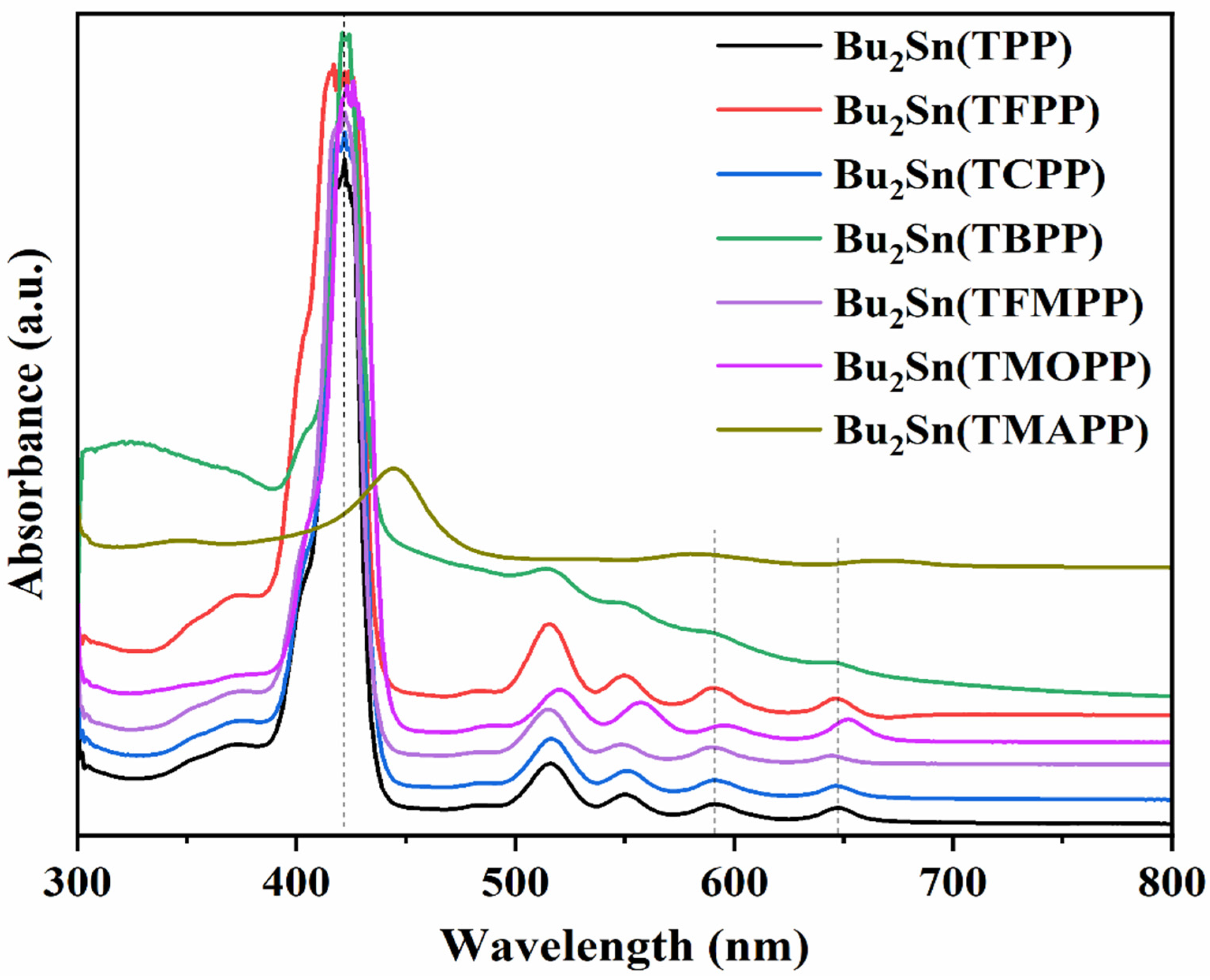

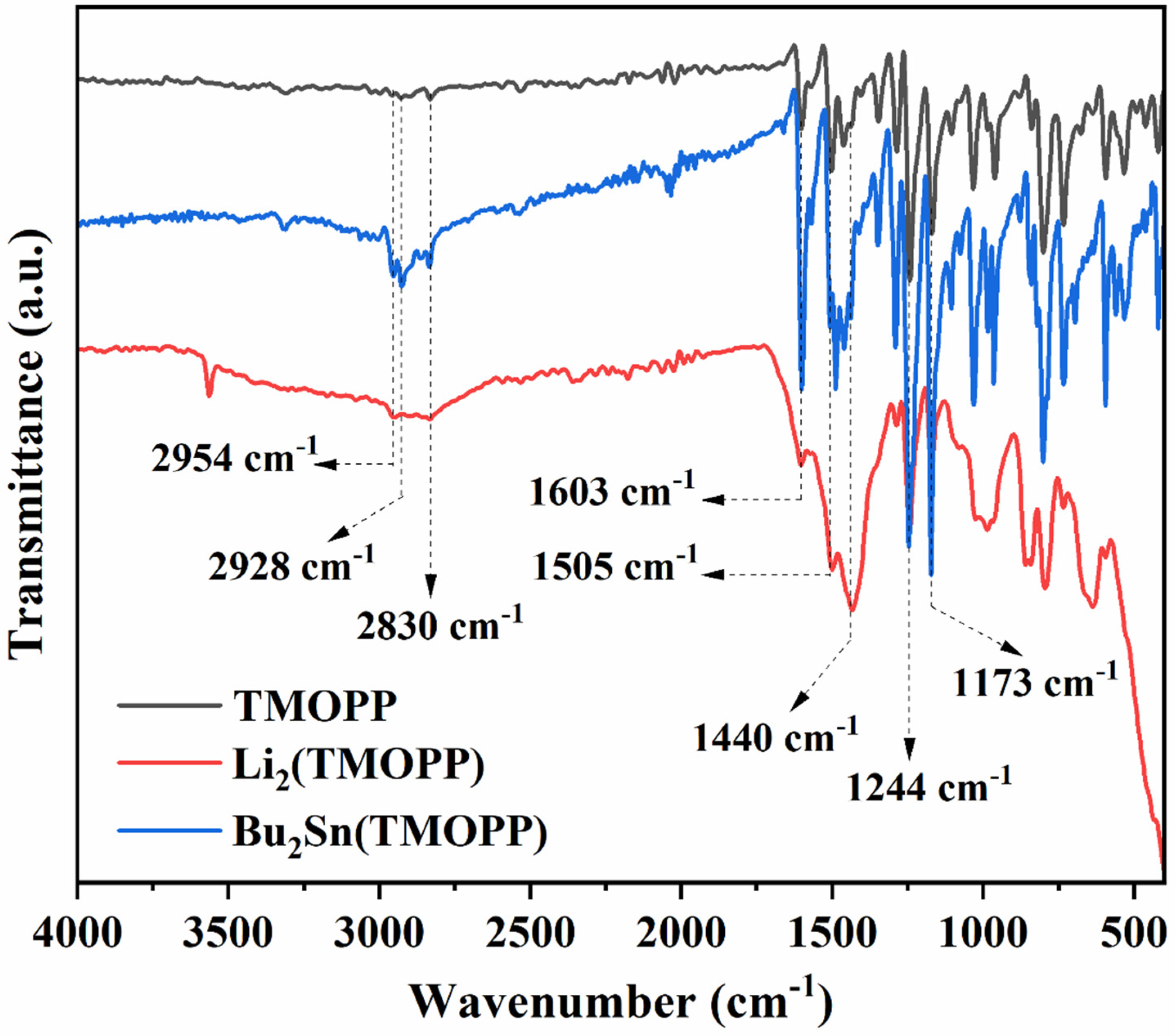

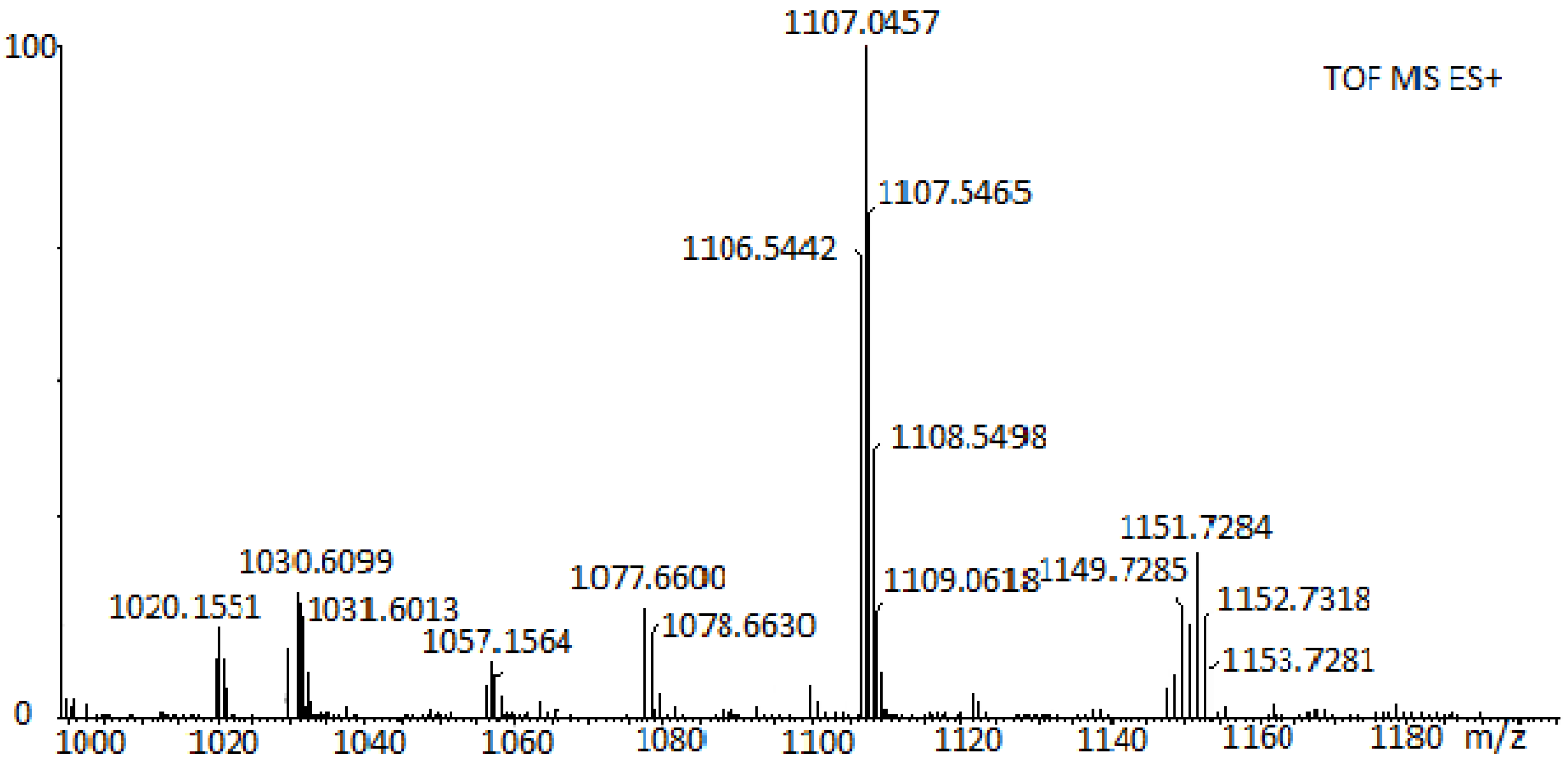

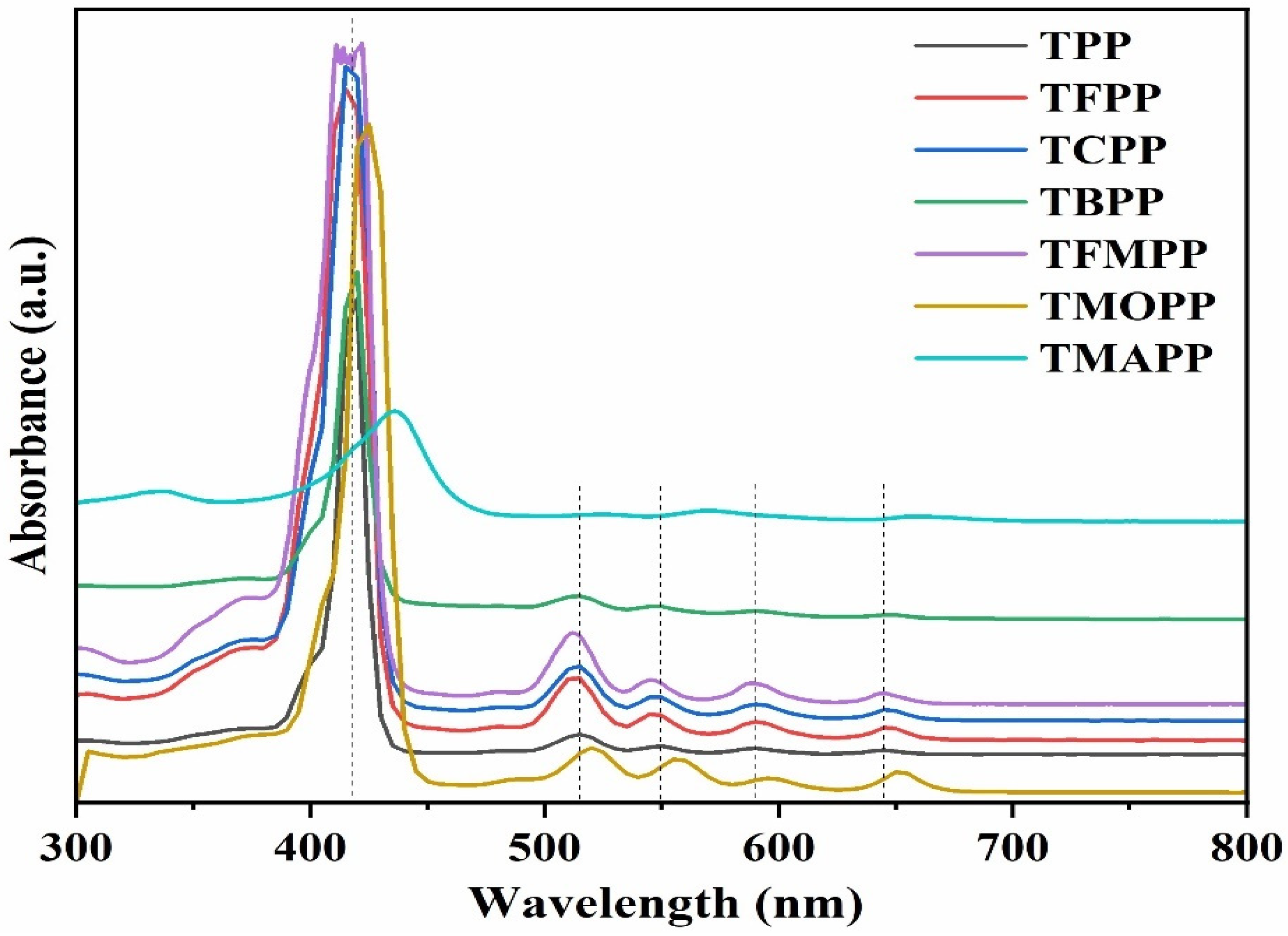

3.1. Characterization of Porphyrin Complexes

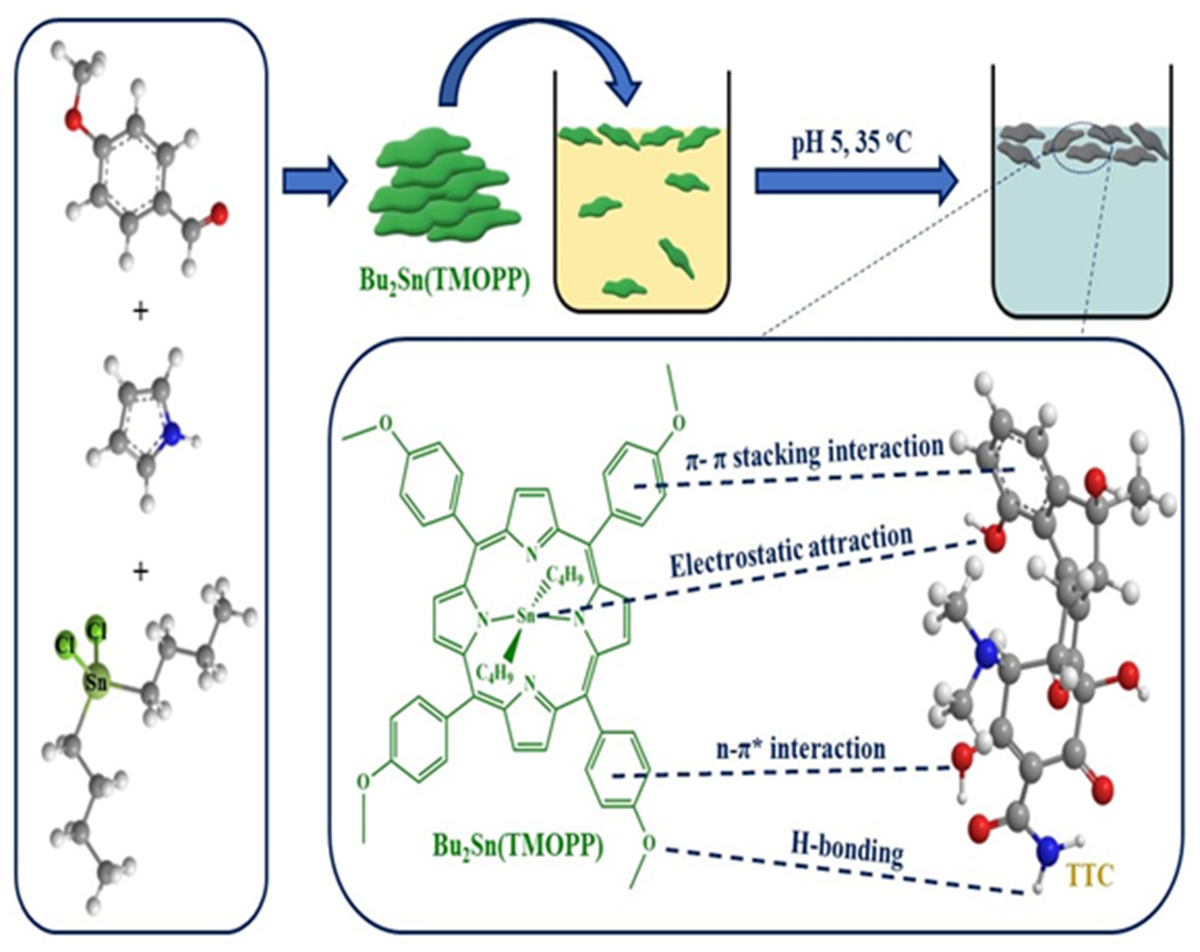

3.2. Adsorption Studies of Tetracycline (TTC) Antibiotic Using Bu2Sn(TMOPP) Compound

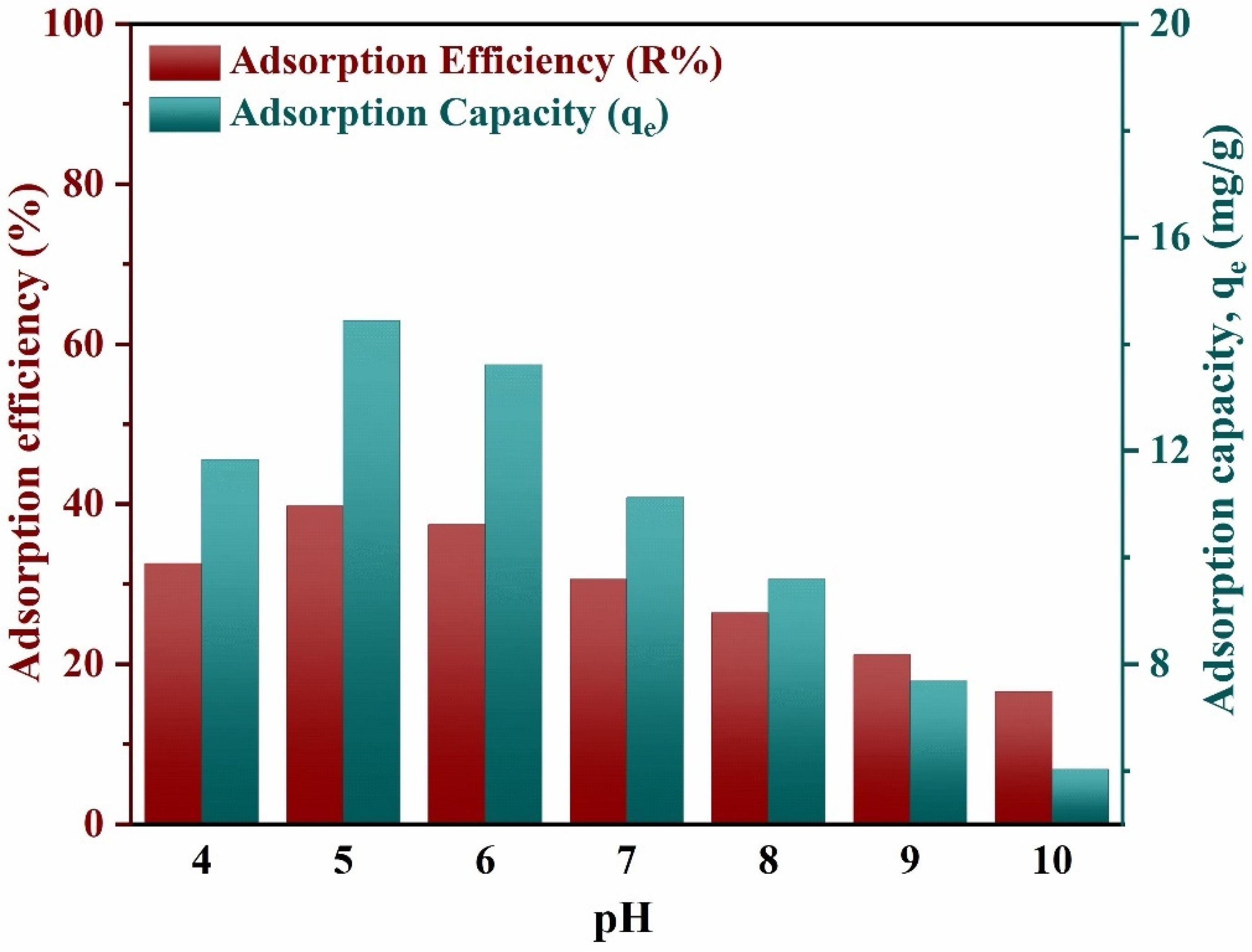

3.2.1. Effect of pH on Adsorption Process

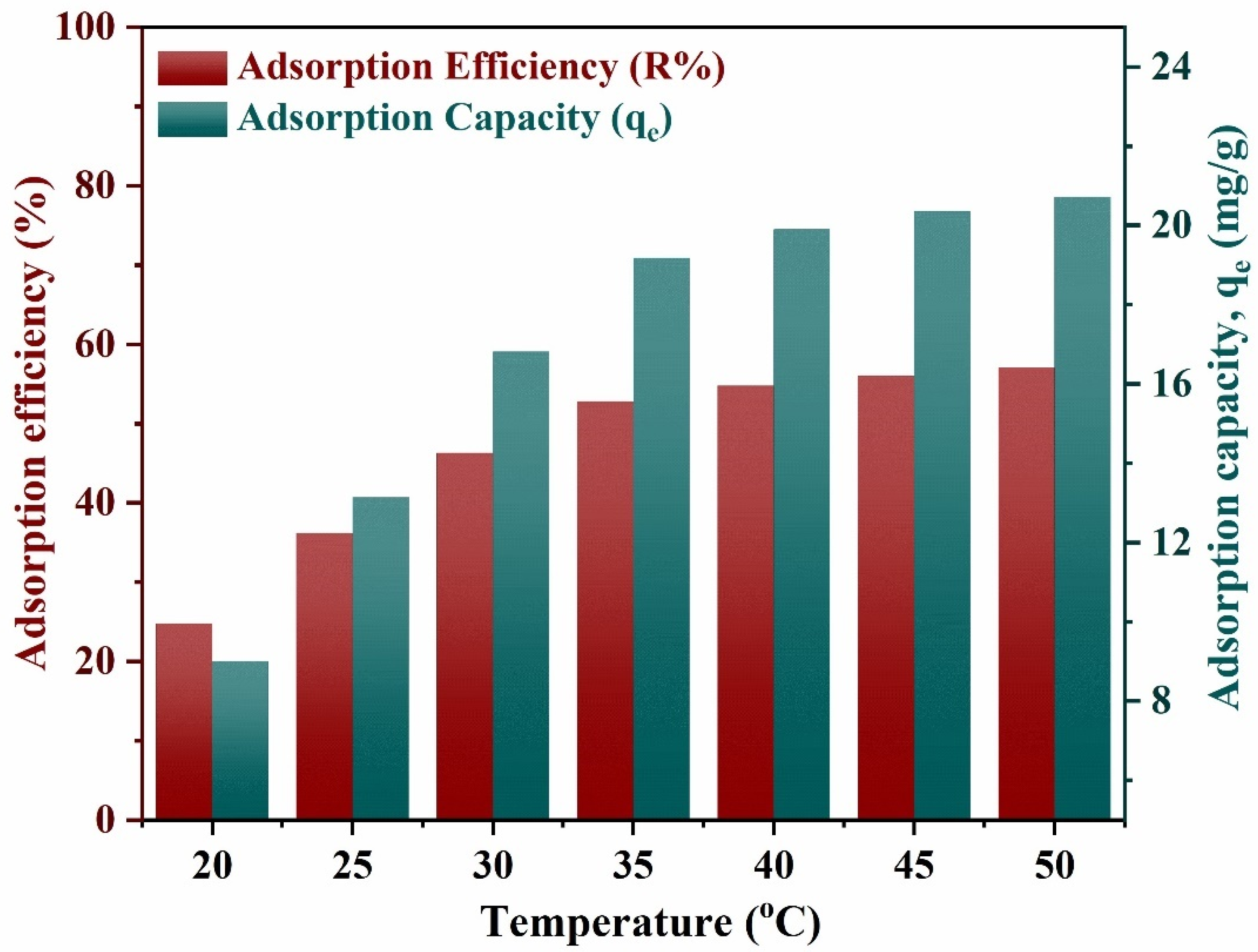

3.2.2. Effect of Temperature on Adsorption Process

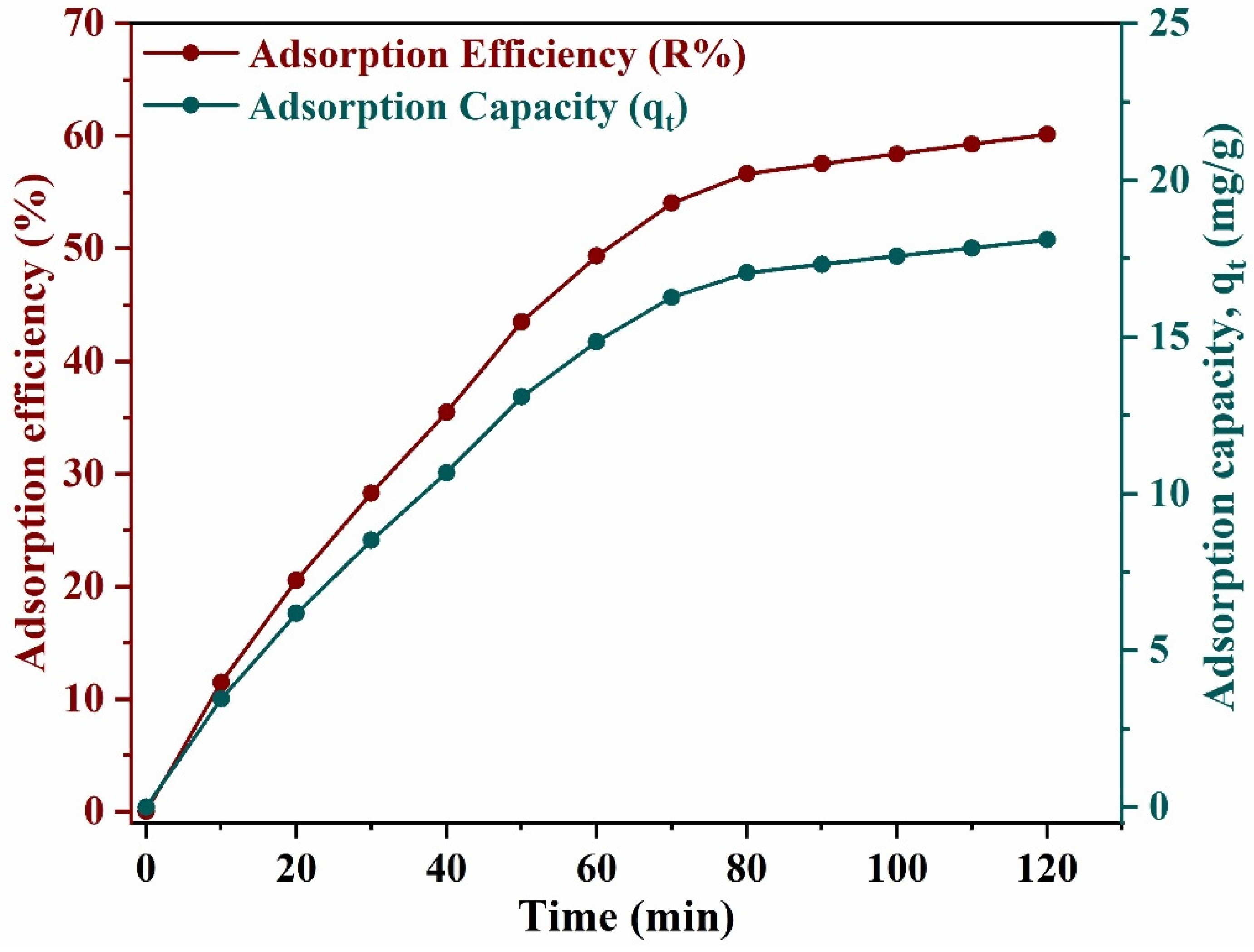

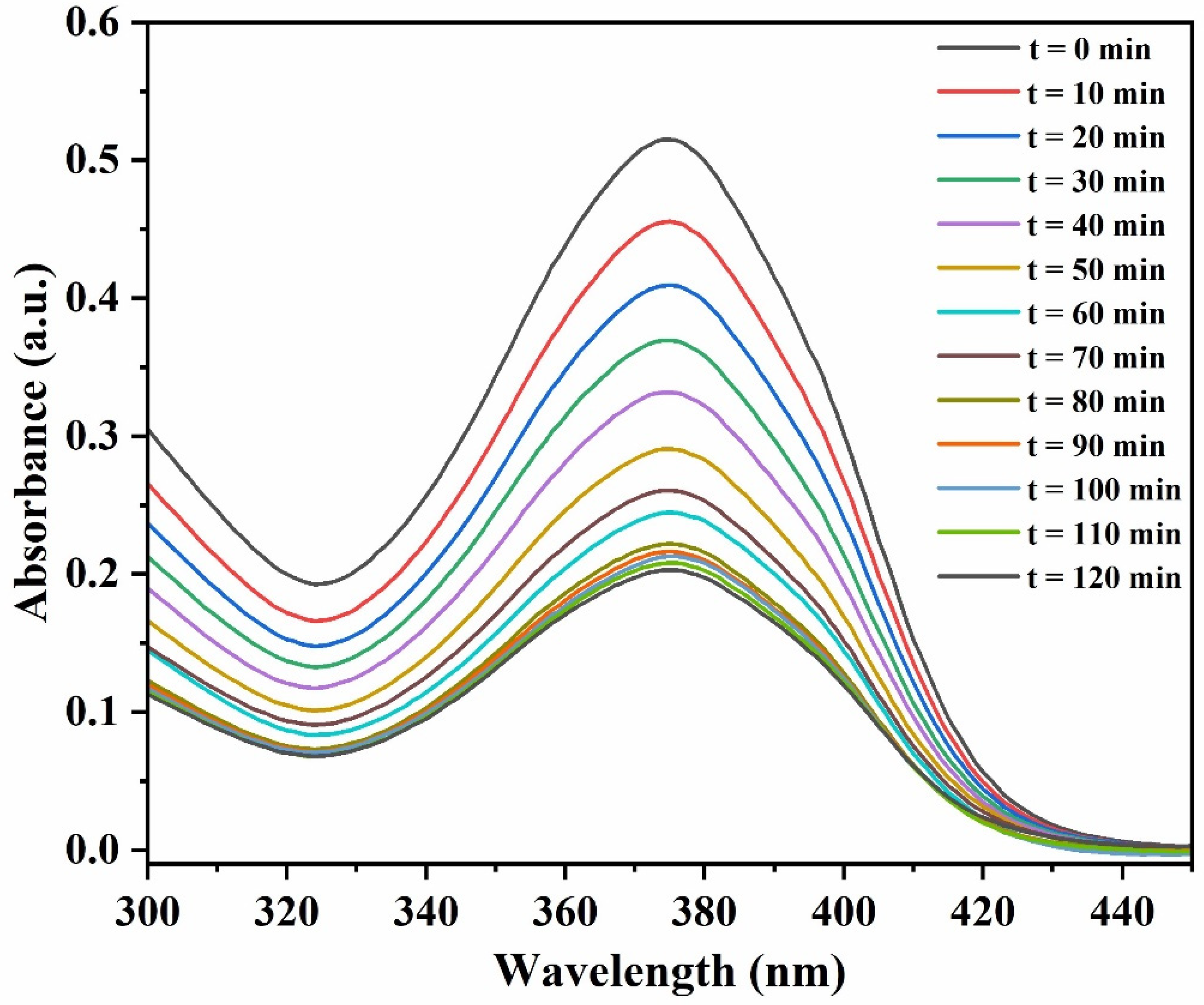

3.2.3. Effect of Time on Adsorption Process

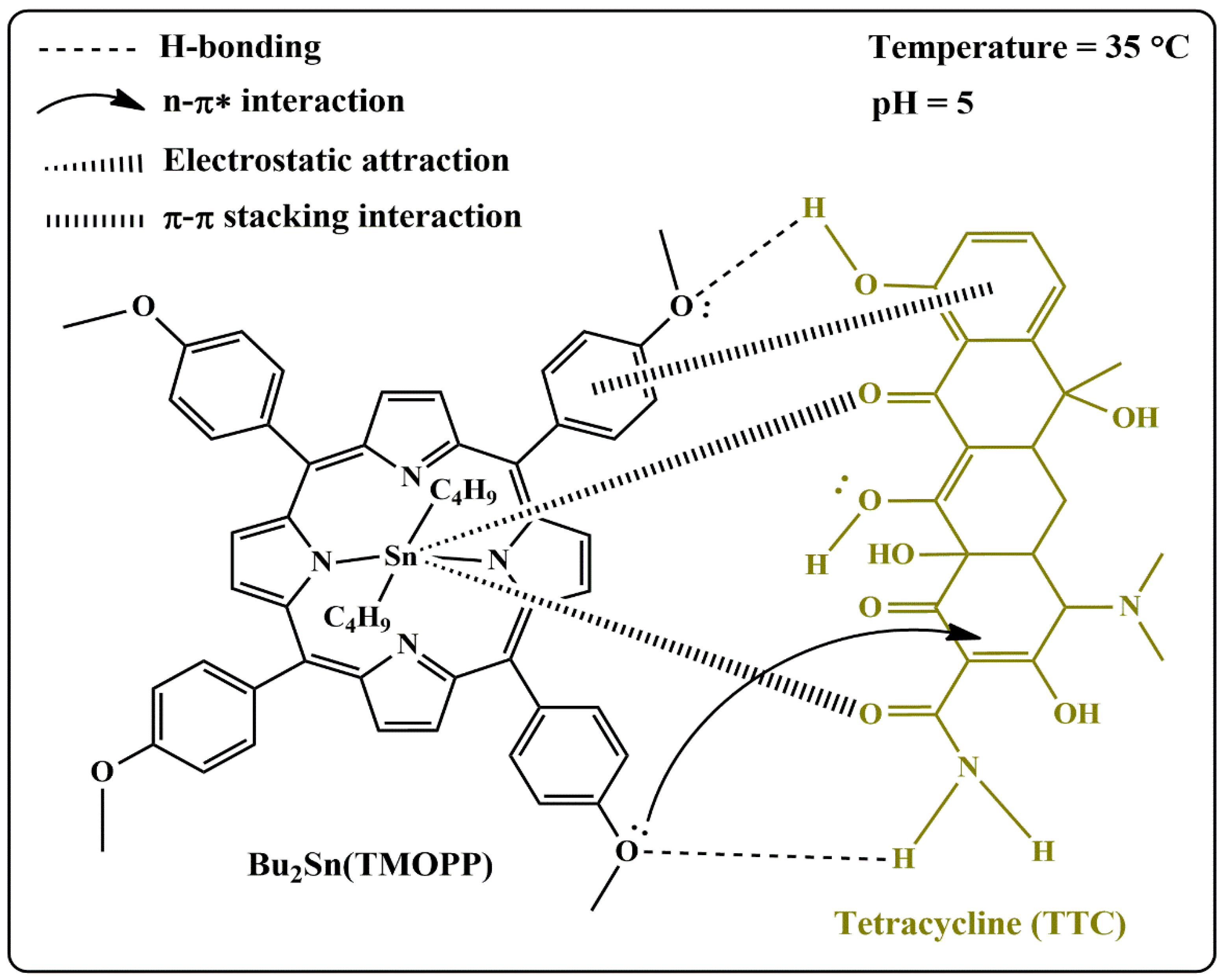

3.2.4. Adsorption Mechanism

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, J.; Zhang, W. Synthesis, self-assembly and applications of functional polymers based on porphyrins. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 95, 65-117. [CrossRef]

- Kayan, A. Polymerization of 3-glycidyloxypropyltrimethoxysilane with different catalysts. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 123, 3527-3534. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, T.; Gayathri, M.P.; Mack, J.; Nyokong, T.; Govindarajan, S.; Babu, B. Blue-Light-Activated Water-Soluble Sn (IV)-Porphyrins for Antibacterial Photodynamic Therapy (aPDT) against Drug-Resistant Bacterial Pathogens. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2024, 21, 2365-2374. [CrossRef]

- Hlabangwane, K.; Matshitse, R.; Managa, M.; Nyokong, T. The application of Sn(IV)Cl2 and In(III)Cl porphyrin-dyed TiO2 nanofibers in photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy for bacterial inactivation in water. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 44, 103795. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, X. Theoretical study of novel porphyrin D-π-A conjugated organic dye sensitizer in solar cells. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 225, 417-425. [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.T.; Karikis, K.; Weber, M.D.; Coto, P.B.; Charisiadis, A.; Charitaki, D.; Costa, R.D. Cunning metal core: efficiency/stability dilemma in metallated porphyrin based light-emitting electrochemical cells. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 13284-13288. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, C.; Roy, S. Ultrafast all-optical universal logic gates with graphene and graphene-oxide metal porphyrin composites. J. Comput. Electron. 2015, 14, 209-213. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.M.; Hong, K.I.; Lee, H.; Jang, W.D. Bioinspired applications of porphyrin derivatives. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2249-2260. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Samanta, D.; Sutar, P.; Kundu, A.; Dasgupta, J.; Maji, T.K. Biomimetic Approach toward Visible Light-Driven Hydrogen Generation Based on a Porphyrin-Based Coordination Polymer Gel. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 15, 25173-25183. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.S.; Hong, Y.; Dogan, N.A.; Yavuz, C.T. Gold Recovery from E-Waste by Porous Porphyrin–Phenazine Network Polymers. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 5343-5349. [CrossRef]

- Radi, S.; El Abiad, C.; Moura, N.M.; Faustino, M.A.; Neves, M.G.P. New hybrid adsorbent based on porphyrin functionalized silica for heavy metals removal: synthesis, characterization, isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamics studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 370, 80-90. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cai, T.; Zhang, S.; Hou, J.; Cheng, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Q. Contamination distribution and non-biological removal pathways of typical tetracycline antibiotics in the environment: a review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132862. [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.T.; Kayan, A. Advanced biopolymer-based Ti/Si-terephthalate hybrid materials for sustainable and efficient adsorption of the tetracycline antibiotic. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135676. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Huang, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Luo, R.; Shang, J. Effects of wind–wave disturbances on adsorption and desorption of tetracycline and sulfadimidine in water–sediment systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 22561–22570. [CrossRef]

- Gao F.; Cui, S.; Li, P.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Song, Y. Ecological toxicological effect of antibiotics in soil. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 186, 012082. [CrossRef]

- Krupka, M.; Piotrowicz-Cie´slak, A.I.; Michalczyk, D.J. Effects of antibiotics on the photosynthetic apparatus of plants. J. Plant Interact. 2022, 17, 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, G.; Wu, H.; Wang, S. A review of metal organic framework (MOFs)-based materials for antibiotics removal via adsorption and photocatalysis, Chemosphere 2021, 272, 129501. [CrossRef]

- Amangelsin, Y.; Semenova, Y.; Dadar, M.; Aljofan, M.; Bjørklund, G. The impact of tetracycline pollution on the aquatic environment and removal strategies, Antibiotics 2023, 12, 440. [CrossRef]

- Mirsoleimani-azizi, S.M.; Setoodeh, P.; Zeinali, S.; Rahimpour, M.R. Tetracycline antibiotic removal from aqueous solutions by MOF-5: adsorption isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 6118–6130. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, W.; Jin, C.; He, Q.; Wang, Y. Fabrication of ZIF-8@TiO2 micron composite via hydrothermal method with enhanced absorption and photocatalytic activities in tetracycline degradation. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 825, 154008. [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Zhao, D.; Shu, M.; Sun, F.; Wang, D.; Chen, C.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, X. Co-doped Fe-MIL-100 as an adsorbent for tetracycline removal from aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2022, 29, 55026–55038. [CrossRef]

- Shee, N.K.; Kim, H.J. Integration of Sn (IV) porphyrin on mesoporous alumina support and visible light catalytic photodegradation of methylene blue. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109033. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Mei, M.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Z. Covalently grafting porphyrin on SnO2 nanorods for hydrogen evolution and tetracycline hydrochloride removal from real pharmaceutical wastewater with significantly improved efficiency. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144859. [CrossRef]

- Shee, N.K.; Kim, H.J. Self-Assembled Nanostructure of Ionic Sn (IV) porphyrin Complex Based on Multivalent Interactions for Photocatalytic Degradation of Water Contaminants. Molecules 2024, 29, 4200. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, W.; Hua, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H. Efficient visual detection and adsorption of tetracyclines using zinc porphyrin-based microporous organic networks. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 339, 126491. [CrossRef]

- Kayan, G.O.; Muhaffel, F.; Kayan, A.; Nofar, M.; Cimenoglu, H. A Study on Tailoring Silver Release from Micro-Arc Oxidation Coating Fabricated on Titanium. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2401129. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D.P.; Blok, J. The coordination chemistry of tin porphyrin complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004, 248, 299-319. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Kuttassery, F.; Mathew, S.; Remello, S.N.; Ohsaki, Y.; Yamamoto, D.; Inoue, H. Protolytic behavior of axially coordinated hydroxy groups of Tin (IV) porphyrins as promising molecular catalysts for water oxidation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2018, 358, 402-410. [CrossRef]

- Dar, U.A.; Shahnawaz, M.; Taneja, P.; Dar, M.A. Recent Advances in Main Group Coordination Driven Porphyrins: A Comprehensive Review. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202304817. [CrossRef]

- Giannoudis, E.; Benazzi, E.; Karlsson, J.; Copley, G.; Panagiotakis, S.; Landrou, G.; Coutsolelos, A.G. Photosensitizers for H2 Evolution Based on Charged or Neutral Zn and Sn Porphyrins. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 1611-1621. [CrossRef]

- Yaman, H.; Kayan, A. Synthesis of novel single site tin porphyrin complexes and the catalytic activity of tin tetrakis (4-fluorophenyl) porphyrin over ε-caprolactone. J. Porphyr. Phthalocya. 2017, 21, 231-237. [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.D.; Sklar, L.; Longo, F.R.; Finarelli, J.D.; Finarelli, M.G. A Mechanistic Study of the Synthesis of meso-Tetraphenylporphin. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1968, 5, 669-678. [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, J.S.; Schreiman, I.C.; Hsu, H.C.; Kearney, P.C.; Marguerettaz, A.M. Rothemund and Adler-Longo reactions revisited: synthesis of tetraphenylporphyrins under equilibrium conditions. J. Organic Chem. 1987, 52, 827-836.

- Cerrahoğlu, E.; Kayan, A.; Bingöl, D. New inorganic–organic hybrid materials and their oxides for removal of heavy metal ions: response surface methodology approach. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2017, 27, 427-435. [CrossRef]

- Mayers, J.M.; Larsen, R.W. Vibrational spectroscopy of Fe tetrakis (4-sulphonatophenyl) porphyrin encapsulated within the metal organic framework HKUST-1. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2019, 107, 107457. [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, K.; Rosiak, N.; Bogucki, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Mizera, M.; Bednarski, W.; Szaciłowski, K. Supramolecular complexes of graphene oxide with porphyrins: An interplay between electronic and magnetic properties. Molecules, 2019, 24, 688. [CrossRef]

- Şen, P.; Hirel, C.; Andraud, C.; Aronica, C.; Bretonnière, Y.; Mohammed, A.; Lindgren, M. Fluorescence and FTIR spectra analysis of trans-A2B2-substituted di-and tetra-phenyl porphyrins. Materials 2010, 3, 4446-4475. [CrossRef]

- Stanisław, O.; Beata, Ł.; Agnieszka, M. Shielding Effects in 1H NMR Spectra of Halogen-Substituted meso-Tetraphenylporphyrin Derivatives. Макрoгетерoциклы, 2019, 12, 17-21. [CrossRef]

- Alka, A.; Pareek, Y.; Shetti, V.S.; Rajeswara Rao, M.; Theophall, G.G.; Lee, W.Z.; Ravikanth, M. Construction of Novel Cyclic Tetrads by Axial Coordination of Thiaporphyrins to Tin (IV) Porphyrin. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 13913-13929. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Gupta, H.; Singh, R.; Kaur, V.; Capalash, N. Benzo-γ-pyrone-based diorganotin (IV) chelates as fluorescent probes for the detection of picric acid from soil and aqueous samples. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2022, 36, e6902. [CrossRef]

- Ohsaki, Y.; Thomas, A.; Kuttassery, F.; Mathew, S.; Remello, S.N.; Nabetani, Y.; Inoue, H. (2018). How does the tin (IV)-insertion to porphyrins proceed in water at ambient temperature?: Re-investigation by time dependent 1H NMR and detection of intermediates. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2018, 482, 914-924. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Guleria, M.; Shelar, S.; Amirdhanayagam, J.; Das, T. Copper metal insertion in porphyrin core compromises the photocytotoxicity of free base porphyrin: Revelation during synthesis of natCu/[64Cu] Cu-porphyrin complex. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2023, 441, 114754. [CrossRef]

- Abdulaeva, I.A.; Birin, K.P.; Polivanovskaia, D.A.; Gorbunova, Y.G.; Tsivadze, A.Y. Functionalized heterocycle-appended porphyrins: catalysis matters. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 42388-42399. [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.; Amuhaya, E.; Oluwole, D.; Prinsloo, E.; Mack, J.; Nyokong, T. Preparation of NIR absorbing axial substituted tin (IV) porphyrins and their photocytotoxic properties. MedChemComm. 2019, 10, 41-48. [CrossRef]

- Gouterman, M.; Wagnière, G.H.; Snyder, L.C. Spectra of porphyrins: Part II. Four orbital model. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1963, 11, 108-127. [CrossRef]

- Oppelt, K.T.; Wöß, E.; Stiftinger, M.; Schöfberger, W.; Buchberger, W.; Knör, G. Photocatalytic reduction of artificial and natural nucleotide co-factors with a chlorophyll-like tin-dihydroporphyrin sensitizer. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 11910-11922. [CrossRef]

- Kayan, A. Recent studies on single site metal alkoxide complexes as catalysts for ring opening polymerization of cyclic compounds. Catal. Surv. Asia 2020, 24, 87-103. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Duan, L.H.; Liu, H.B.; Wu, J.; Gao, L. Mesoporous Silica-Confined MOF-525 for Stable Adsorption of Tetracycline over a Wide pH Application Range. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 3806-3816. [CrossRef]

- Demirci, G.V.; Baig, M.T.; Kayan, A. UiO-66 MOF/Zr-di-terephthalate/cellulose hybrid composite synthesized via sol-gel approach for the efficient removal of methylene blue dye. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137950. [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Ma, S.; Gao, J.; Xu, M.; Xue, J.; Wang, M. Synthesis of porphyrin Zr-MOFs for the adsorption and photodegradation of antibiotics under visible light. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 17228-17238. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, S.; Zhao, Z.; Su, Y.; Long, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z. Microwave-assisted hydrothermal assembly of 2D copper-porphyrin metal-organic frameworks for the removal of dyes and antibiotics from water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 39186-39197. [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.T.; Kayan, A. Eco-friendly novel adsorbents composed of hybrid compounds for efficient adsorption of methylene blue and Congo red dyes: Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 862-883. [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | %C Calcd. | %C Found | %H Calcd. | %H Found | %N Calcd. | %N Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bu(TPP)SnCl | 69.97 | 71.32 | 4.53 | 4.62 | 6.80 | 6.62 |

| Bu(TFPP)SnCl | 64.35 | 64.01 | 3.71 | 4.03 | 6.25 | 6.18 |

| Bu(TCPP)SnCl | 59.82 | 59.94 | 3.66 | 3.46 | 5.81 | 5.83 |

| Bu(TBPP)SnCl | 50.59 | 50.23 | 2.92 | 3.18 | 4.92 | 4.78 |

| Bu(TFMPP)SnCl | 56.99 | 56.43 | 3.03 | 3.18 | 5.11 | 4.88 |

| Bu(TMOPP)SnCl | 66.15 | 65.85 | 4.80 | 4.63 | 5.93 | 5.99 |

| Bu(TMAPP)SnCl | 67.51 | 66.88 | 5.77 | 5.61 | 11.25 | 10.77 |

| Bu2Sn(TPP) | 73.68 | 72.46 | 5.71 | 5.98 | 6.61 | 6.42 |

| Bu2Sn(TFPP) | 67.91 | 66.82 | 4.82 | 5.20 | 6.09 | 5.86 |

| Bu2Sn(TCPP) | 63.38 | 63.02 | 4.50 | 4.67 | 5.69 | 5.57 |

| Bu2Sn(TBPP) | 53.69 | 52.57 | 3.81 | 3.92 | 4.82 | 4.98 |

| Bu2Sn(TFMPP) | 60.07 | 61.30 | 3.96 | 4.11 | 5.00 | 4.96 |

| Bu2Sn(TMOPP) | 69.50 | 68.47 | 5.83 | 5.63 | 5.79 | 5.93 |

| Bu2Sn(TMAPP) | 70.66 | 69.12 | 6.72 | 6.43 | 10.99 | 10.43 |

| Tin Compounds | B-band | Q-bands | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aH2TPP | 415 | 515 | 550 | 590 | 645 |

| aH2TFPP | 415 | 515 | 545 | 590 | 645 |

| aH2TCPP | 415 | 515 | 550 | 590 | 645 |

| aH2TBPP | 420 | 515 | 550 | 590 | 645 |

| aH2TFMPP | 416 | 512 | 545 | 589 | 644 |

| aH2TMOPP | 420 | 515 | 555 | 595 | 650 |

| aH2TMAPP | 436 | 522 | 569 | - | 658 |

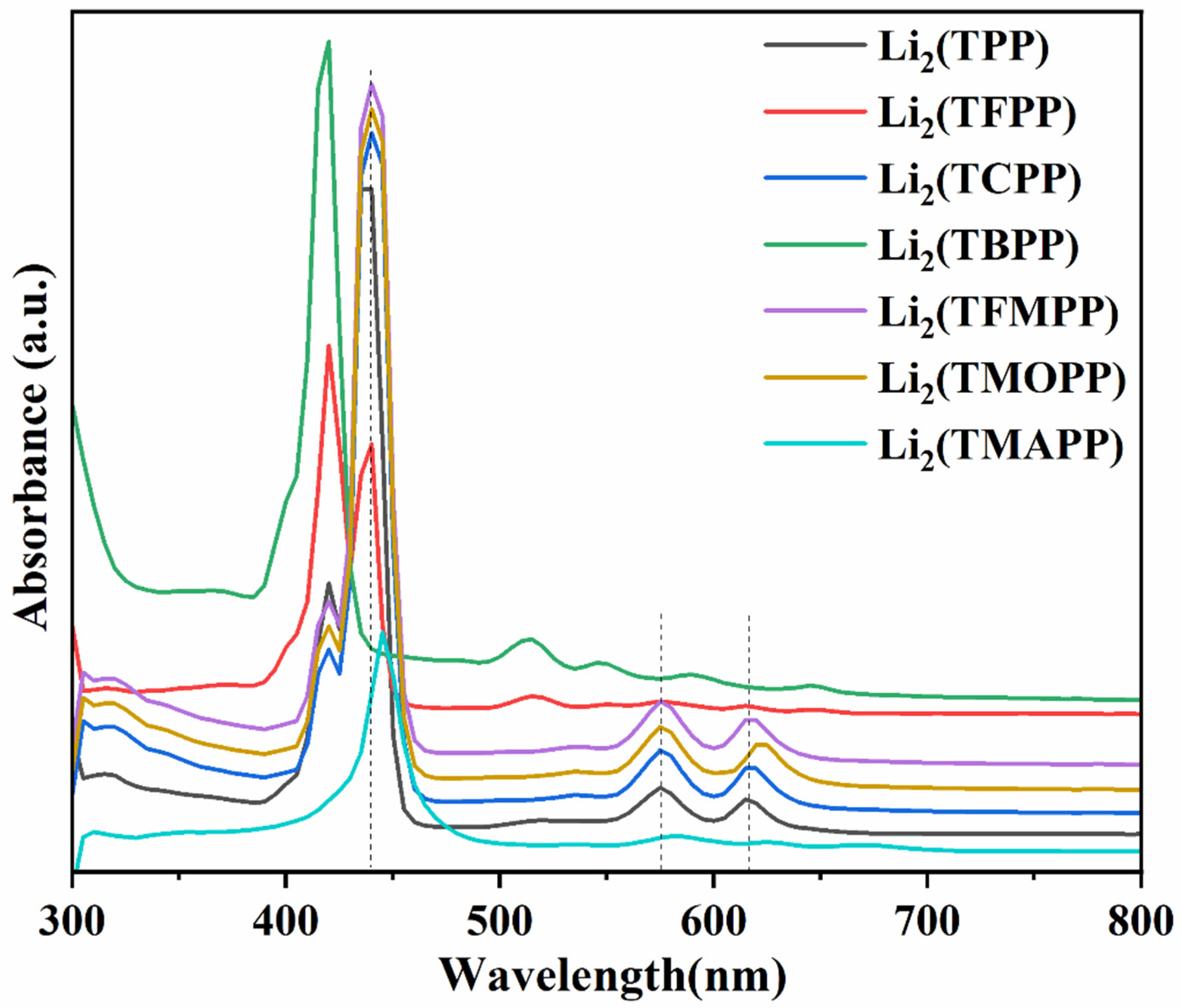

| bLi2TPP | 440 | 576 | 615 | ||

| bLi2TFPP | 440 | 575 | 615 | ||

| bLi2TCPP | 440 | 575 | 615 | ||

| bLi2TBPP | 440 | 525 | 575 | 618 | |

| bLi2TFMPP | 440 | 575 | 615 | ||

| bLi2TMOPP | 440 | 575 | 620 | ||

| bLi2TMAPP | 445 | 582 | 627 | ||

| bBu2(TPP)Sn | 422 | 517 | 551 | 591 | 647 |

| bBu2(TFPP)Sn | 422 | 517 | 551 | 591 | 647 |

| bBu2(TCPP)Sn | 422 | 517 | 551 | 591 | 647 |

| bBu2(TBPP)Sn | 422 | 517 | - | 591 | 647 |

| bBu2(TFMPP)Sn | 422 | 517 | 551 | 591 | 647 |

| bBu2(TMOPP)Sn | 425 | 520 | 558 | 594 | 654 |

| bBu2(TMAPP)Sn | 445 | - | - | 582 | 669 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).