Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

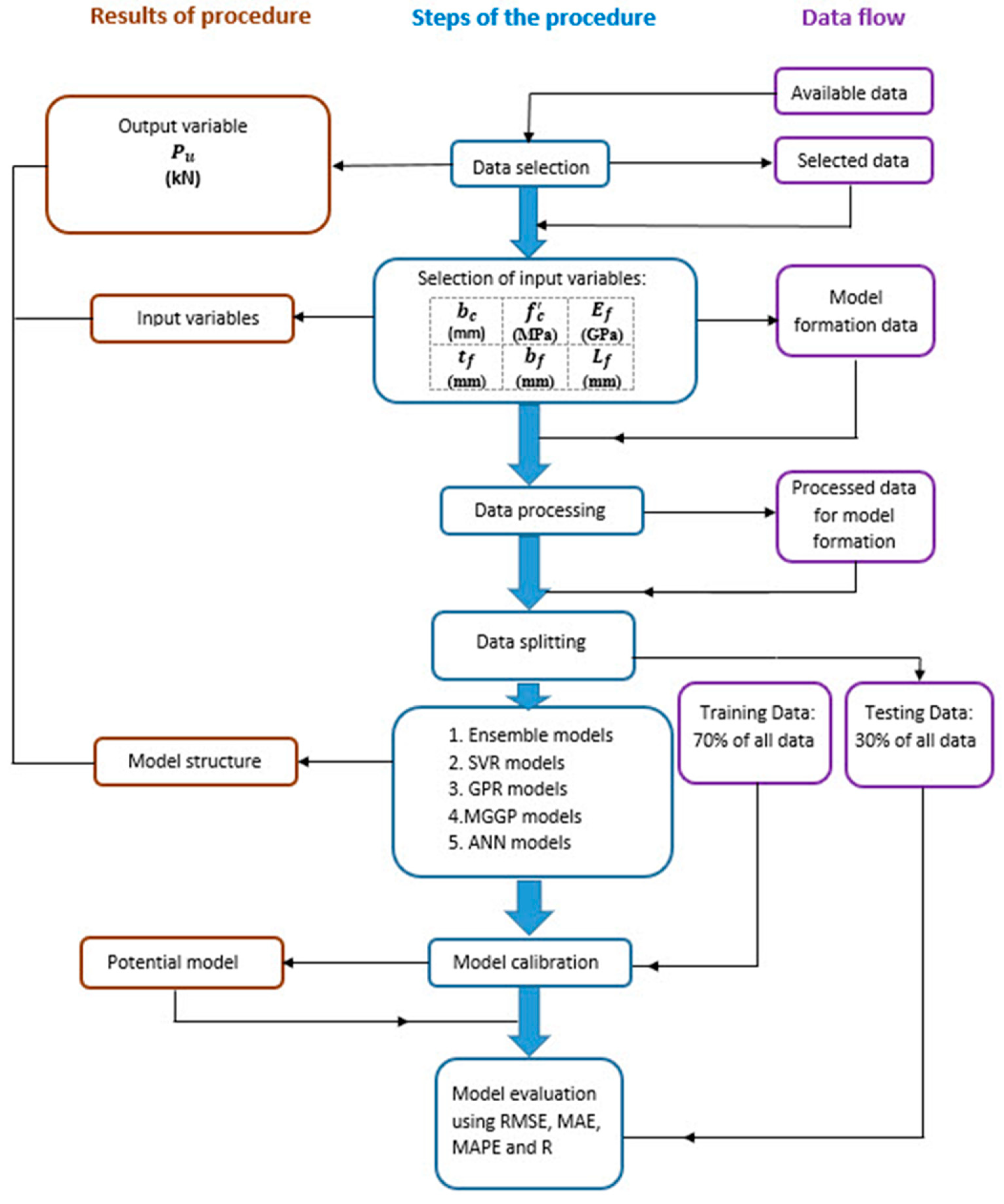

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Multiple Linear Regression

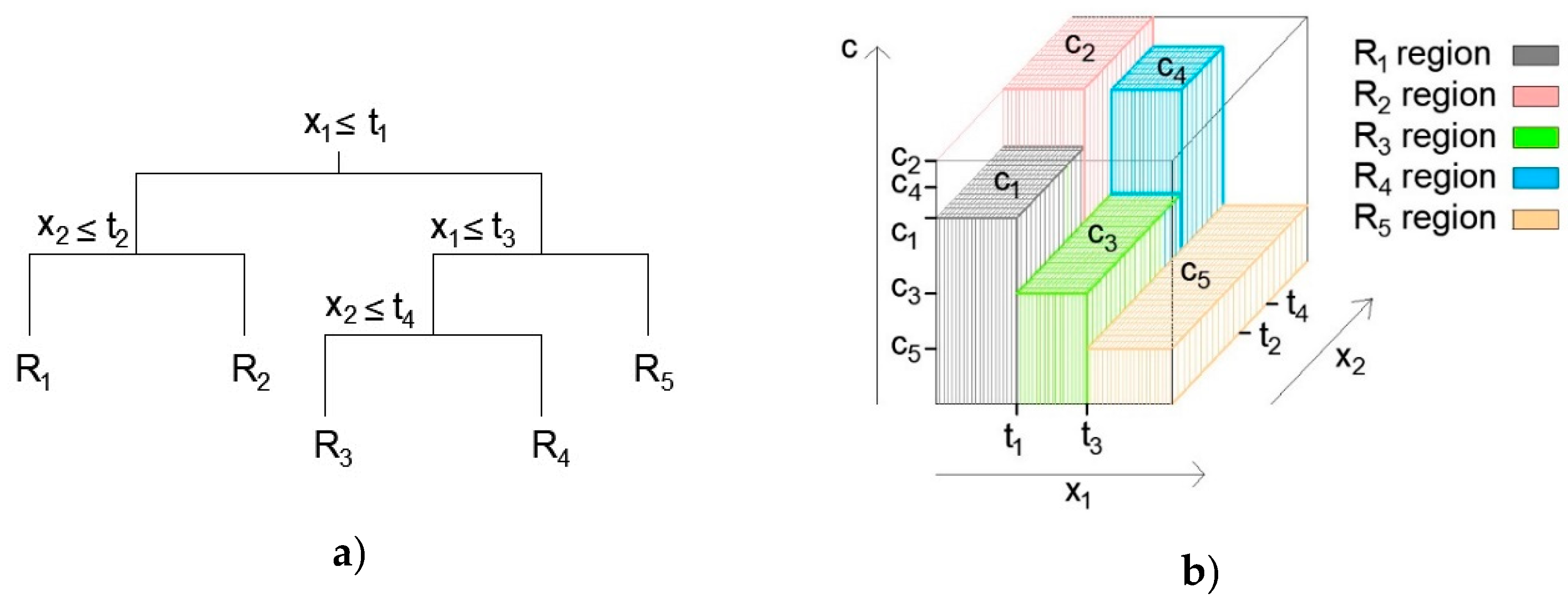

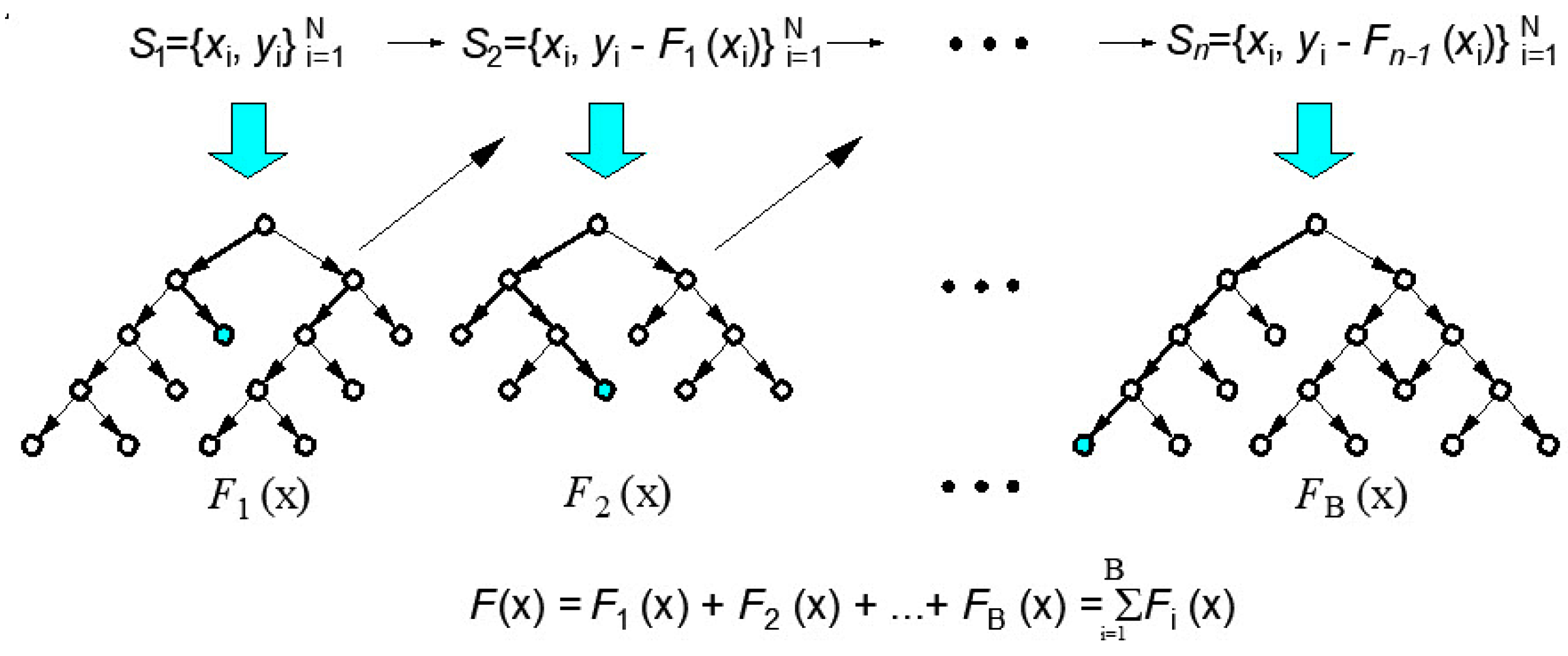

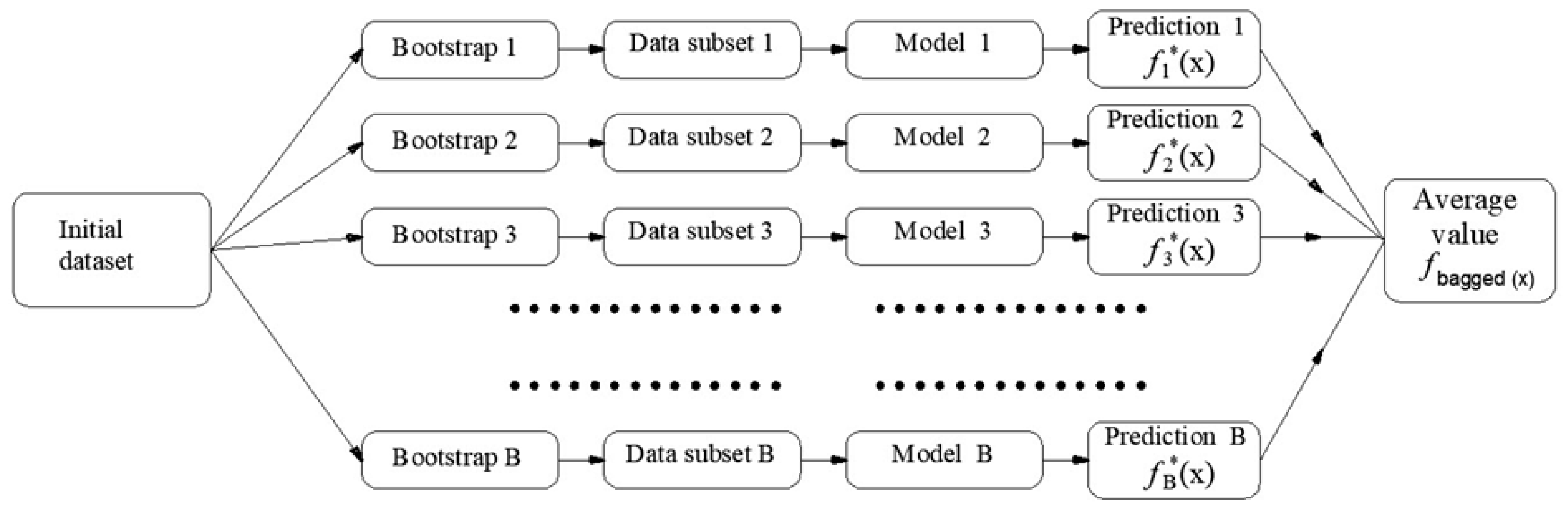

2.2. Regression Trees Ensembles: Boosted Trees, Bagging and Random Forest

2.2.1. Boosting Methodology

2.2.2. Bagging and Random Forest (RF) Methodology

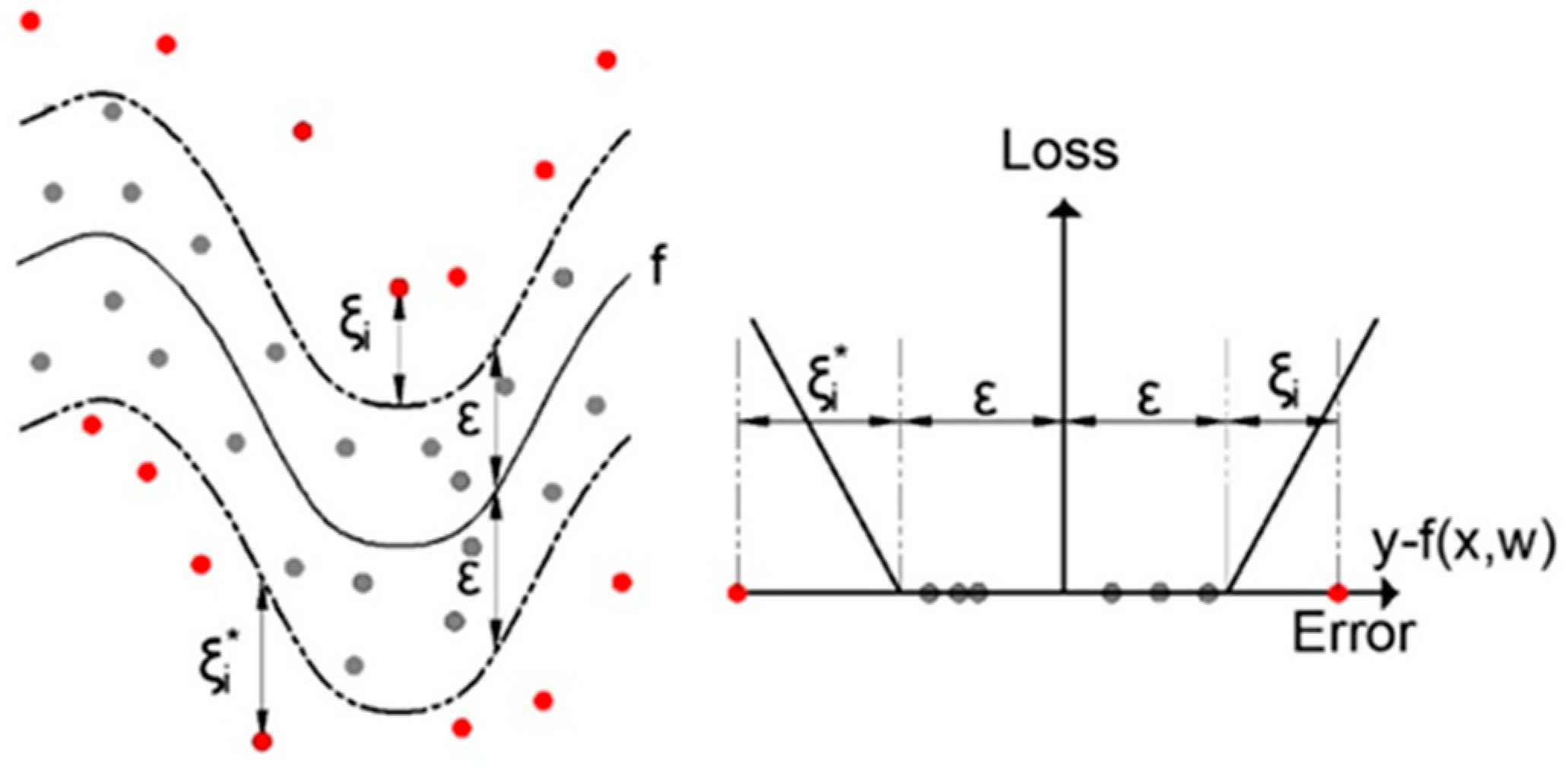

2.3. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

- Linear kernel

- Sigmoid kernel:

- Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel .

2.4. Gaussian Process Regression (GPR)

- is the mean vector.

- is the covariance matrix, which can be divided into blocks (19):

- is the covariance between the test point and training points.

- is the variance at the test point.

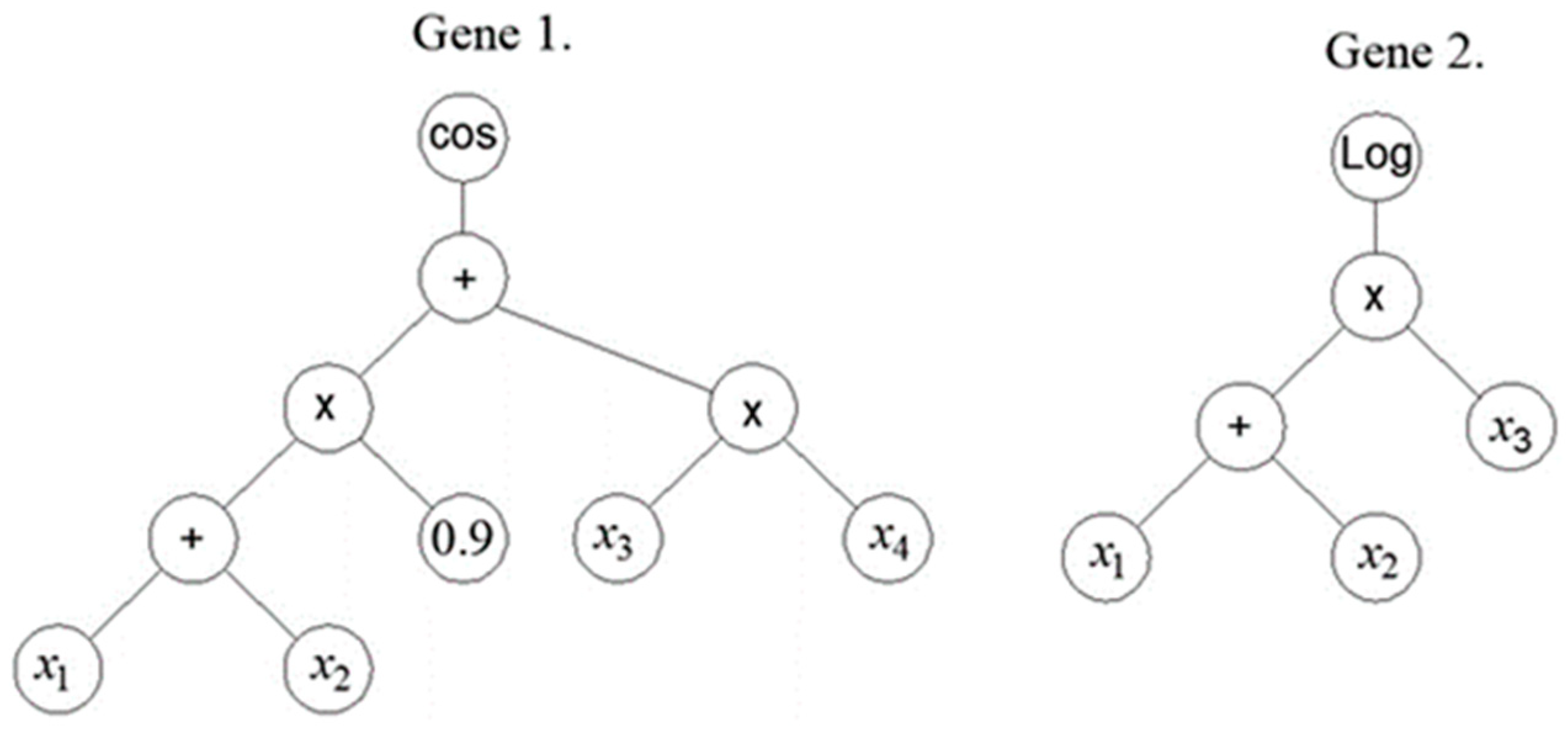

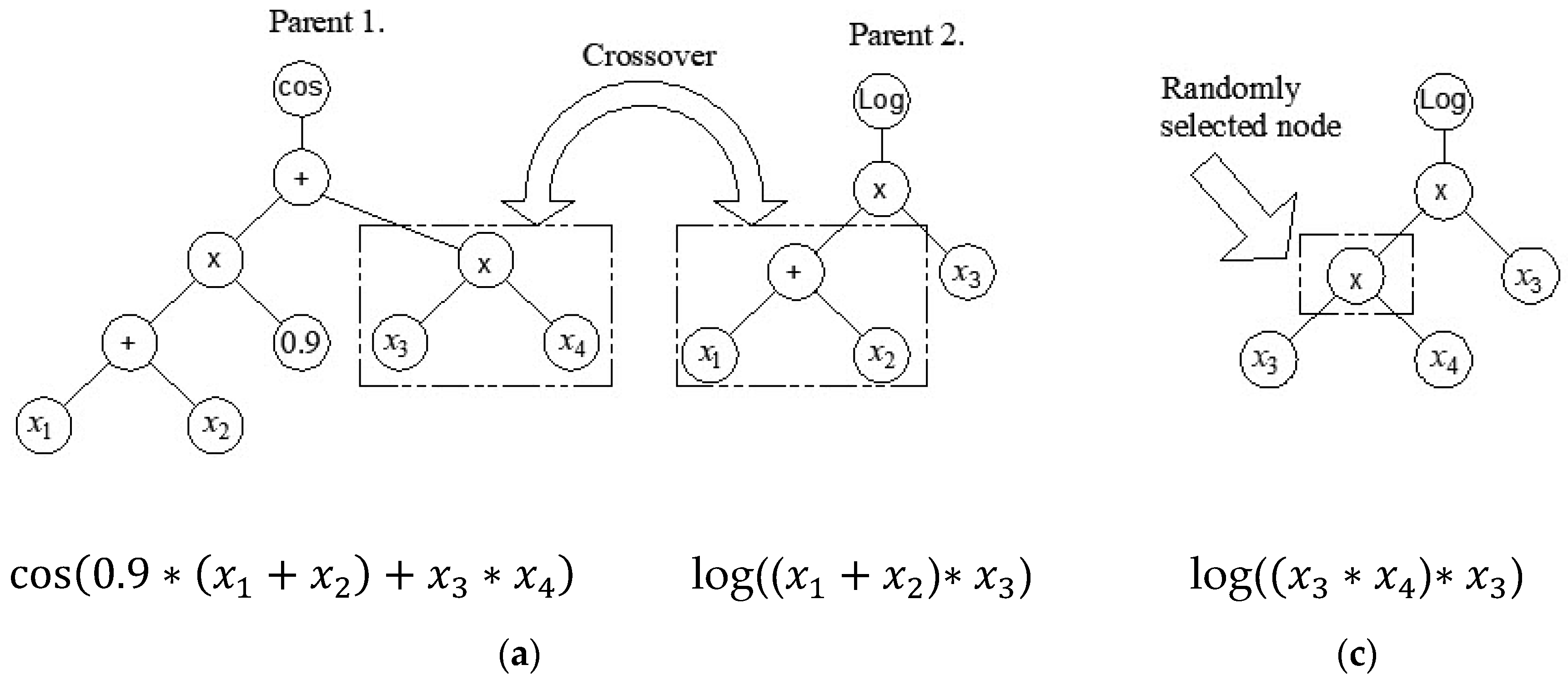

2.5. Multi Gene Genetic Programming

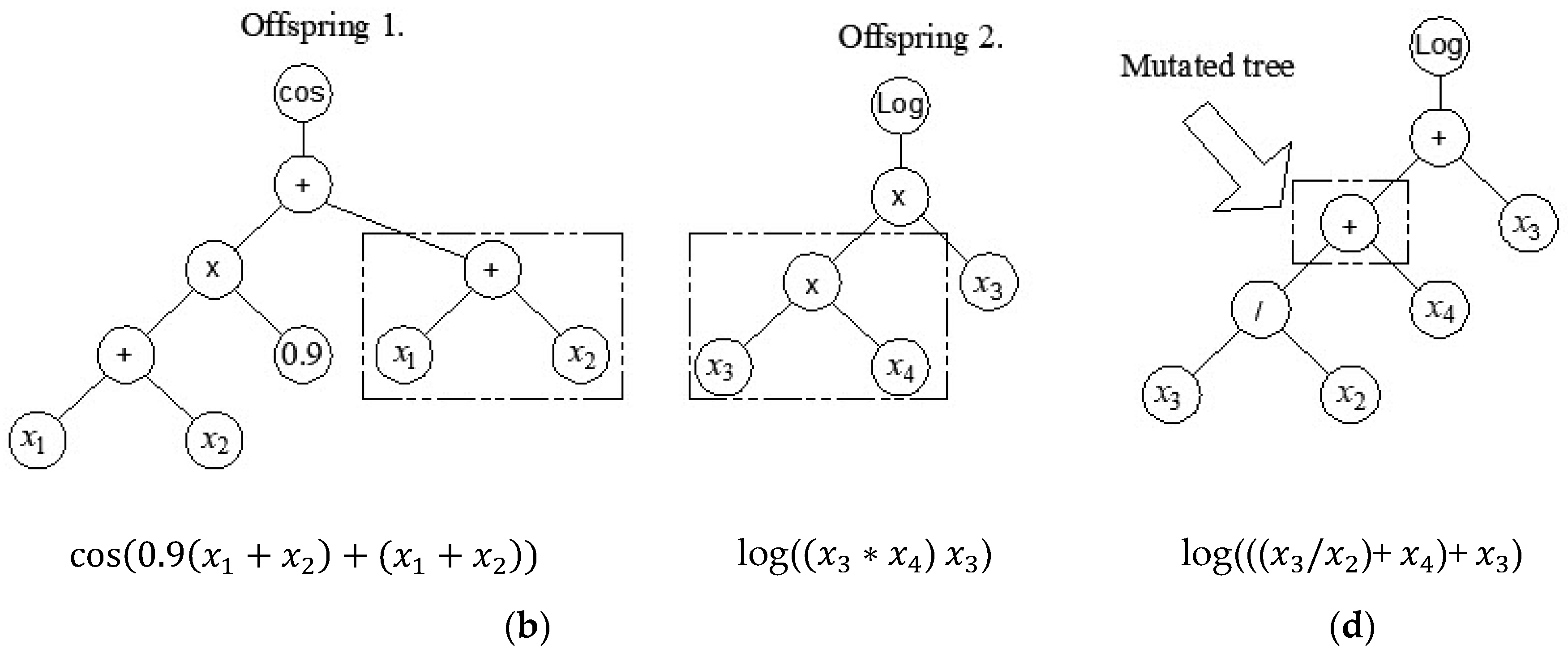

2.6. Artificial Neural Networks

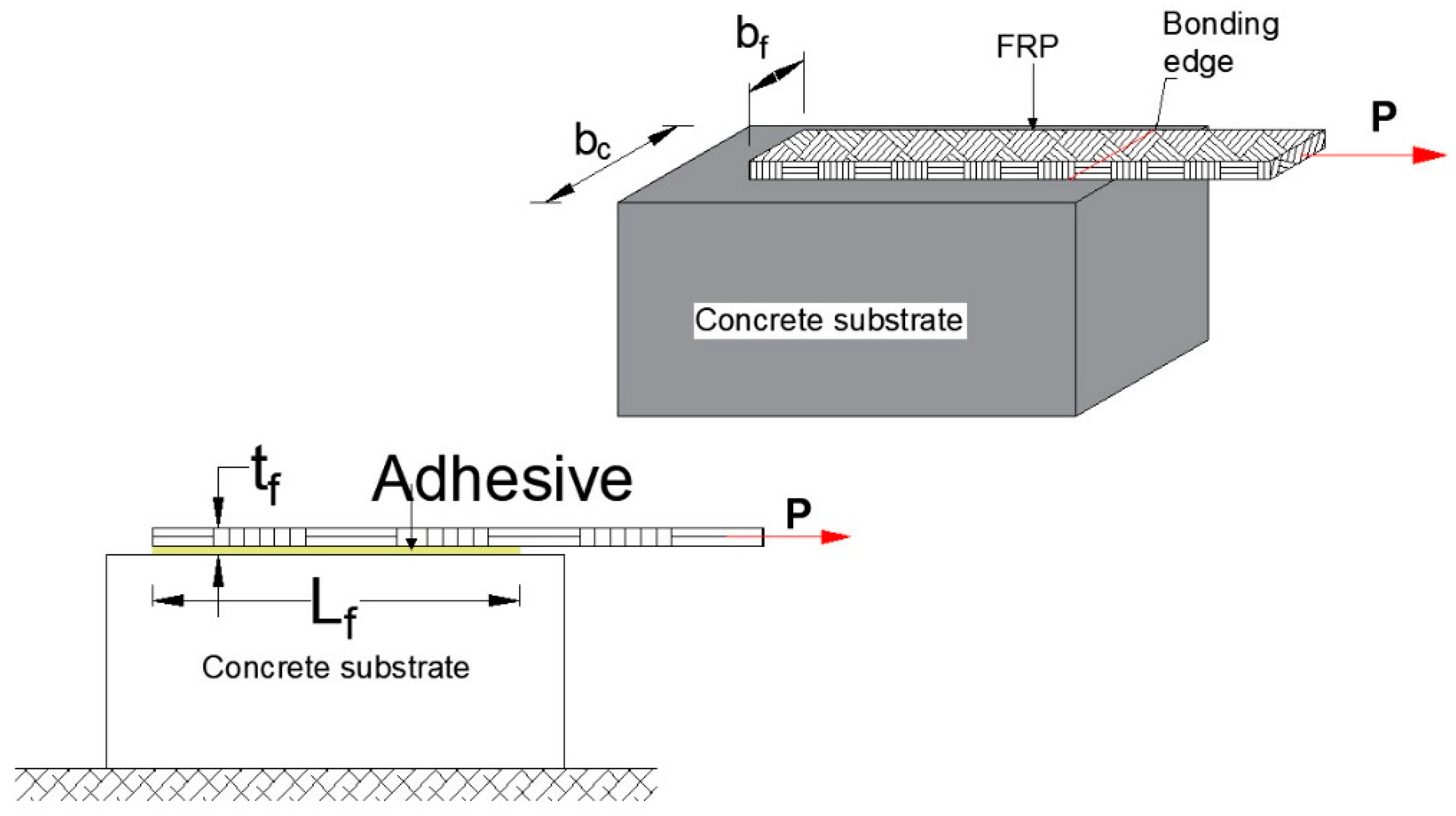

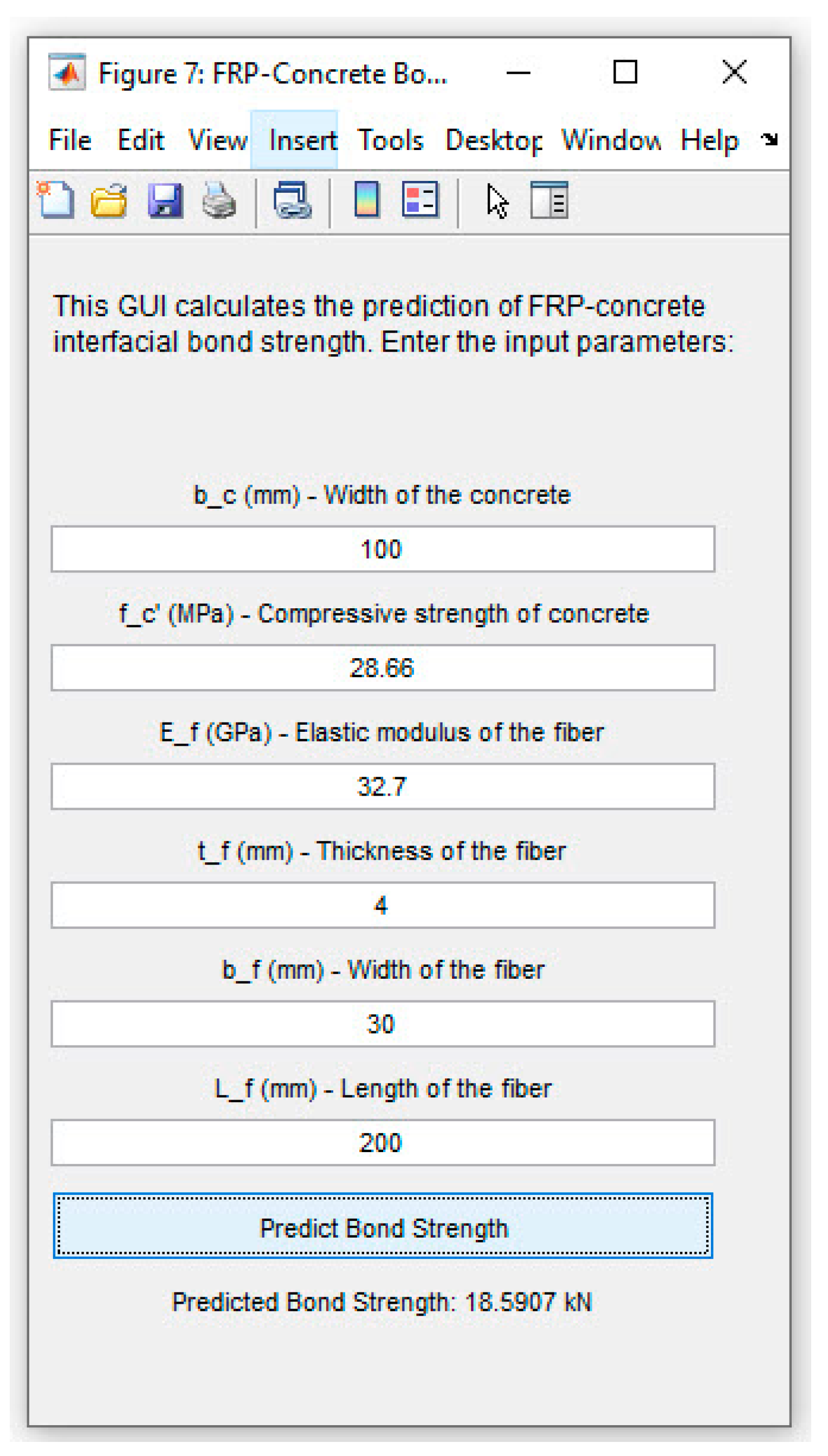

3. Dataset

4. Results and Discussion

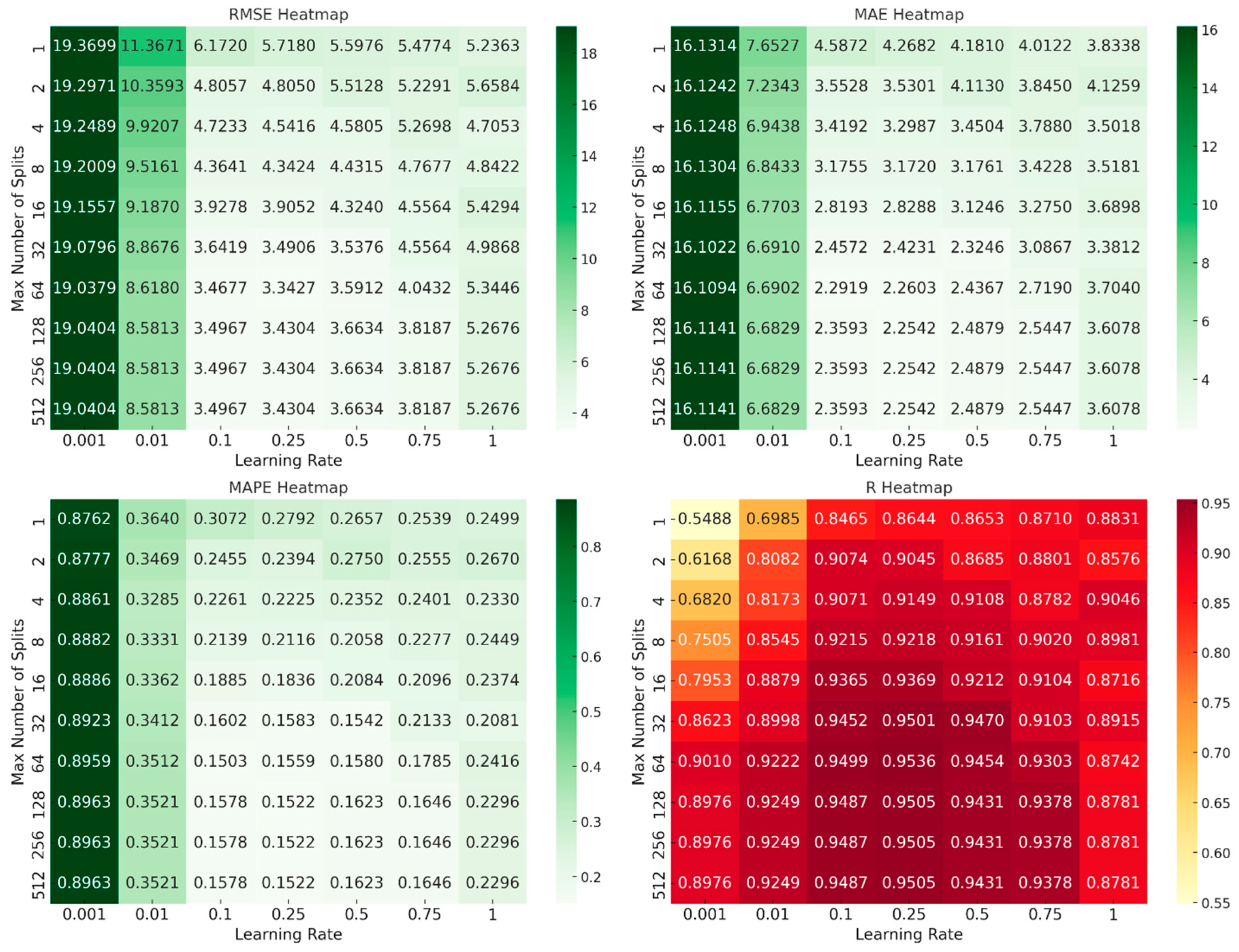

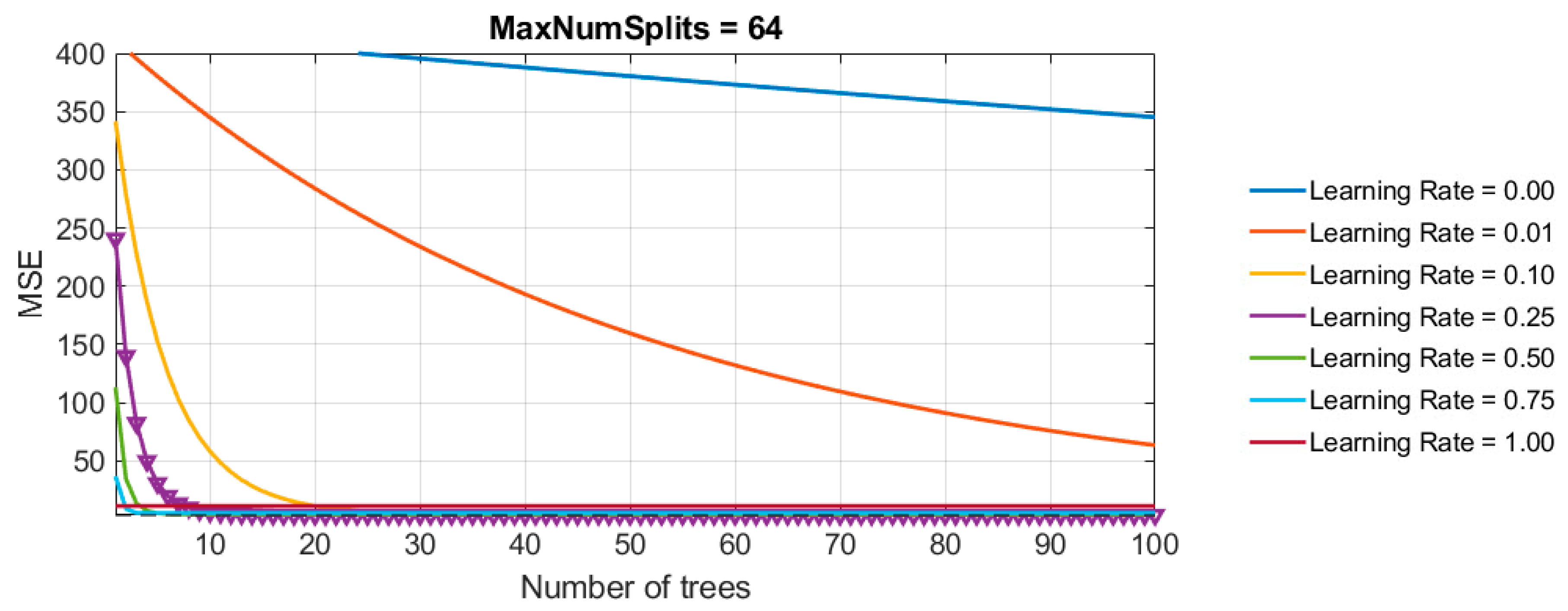

- Number of Generated Trees (NumLearningCycles = 100): The ensemble was limited to 100 trees to balance model complexity and prevent overfitting. This parameter was kept constant during the grid search to evaluate the impact of the learning rate and tree depth more precisely.

- Learning Rate (λ): Grid search was used to explore learning rates ranging from 0.001 to 1.0. The search revealed that a learning rate of 0.1 provided the best trade-off between fast convergence and error minimization.

- Number of Splits (MaxNumSplits): Tree depth, represented by the maximum number of splits, was also varied in the grid search. The search evaluated depths ranging from 1 split (shallow trees) to 512 splits (deep trees). Tree complexity was controlled by adjusting the maximum number of splits (MaxNumSplits), calculated in relation to dataset size. The maximum depth of the trees was determined using the formula , where n is the number of data points and rounded to a whole number. The term n - 1 is used because the number of possible splits equals n - 1, which considers the total number of internal nodes required to split between adjacent points. Taking the logarithm of n−1 for base 2 helps determine the approximate number of splits required for full separation of the dataset. This value is then rounded to the nearest whole number to represent the maximum depth of the decision tree in terms of the number of splits. This depth calculation ensures that the trees are not too deep relative to the dataset size, which helps prevent overfitting.

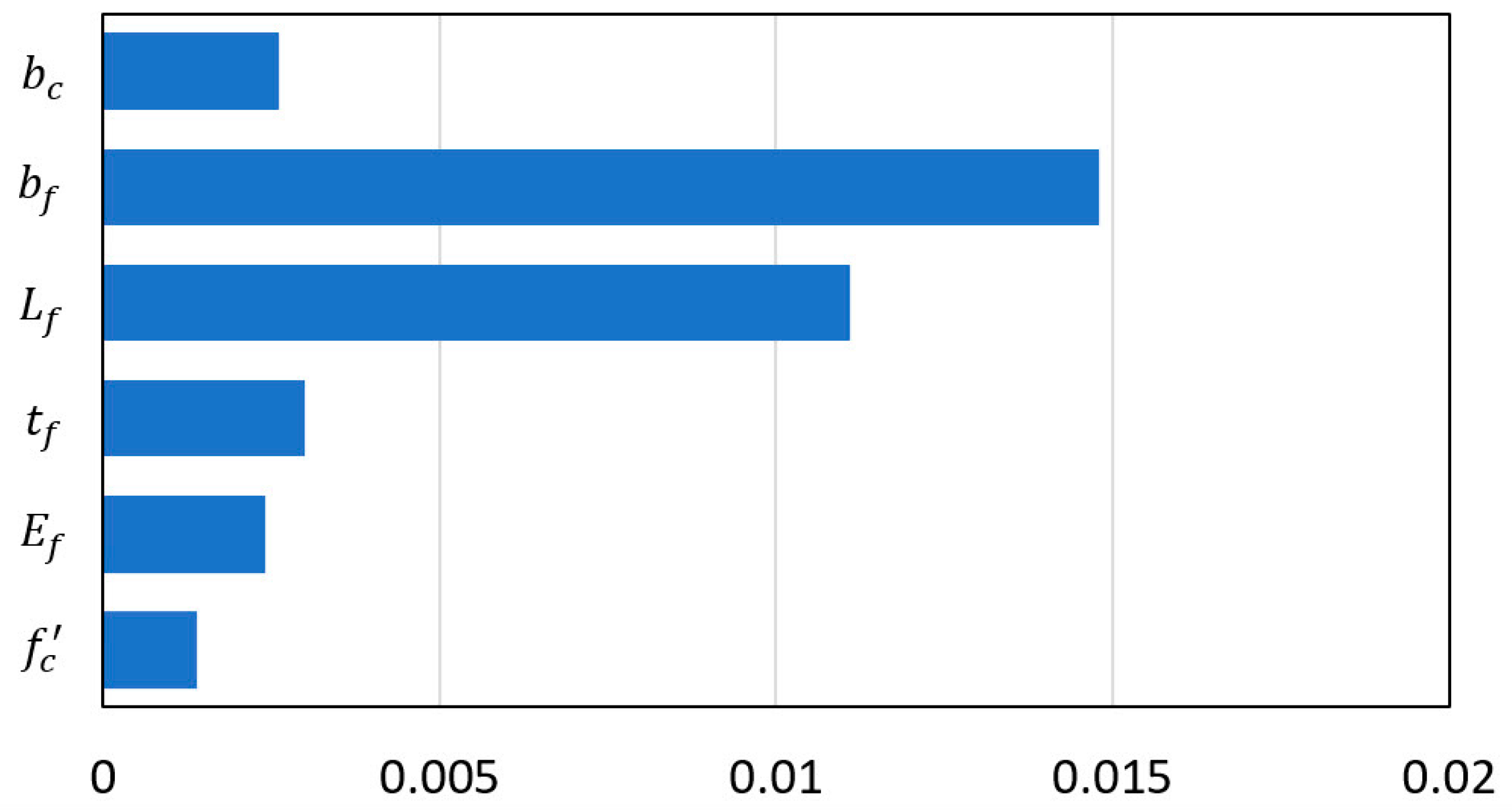

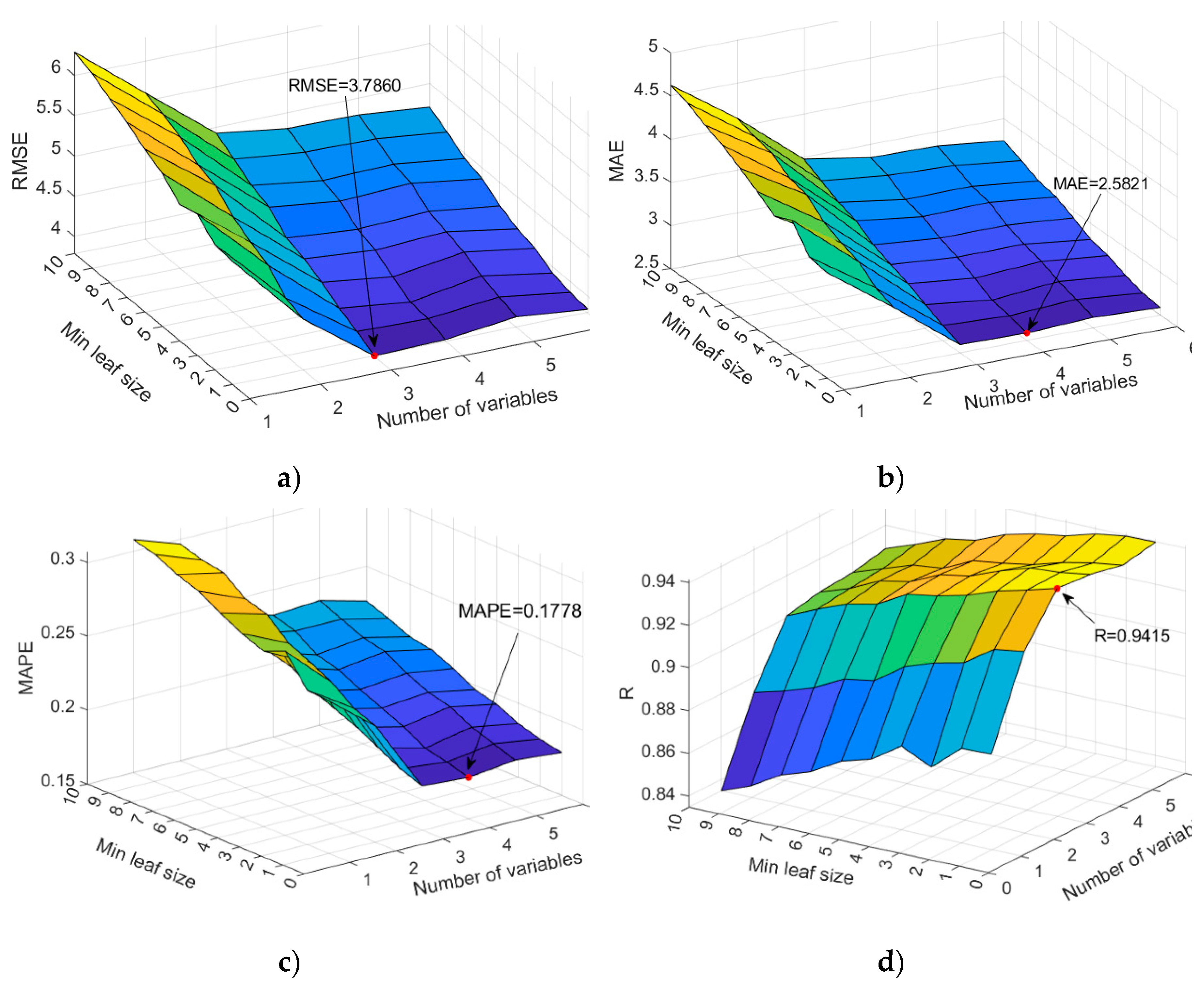

- Min Leaf Size: This parameter controls the minimum number of observations required to form a leaf in a decision tree. Smaller leaf sizes result in deeper trees, allowing the model to capture more detailed patterns in the data but also increasing the risk of overfitting. In this implementation, Min Leaf Size is varied from 1 to 10.

- Number of Variables to Sample: At each split in a decision tree, a subset of predictor variables is randomly selected for consideration. The number of variables sampled at each split (NumVariablesToSample) is varied from 1 to 6.

- Best RMSE: 3.7860, with Min Leaf Size = 1 and Number of Variables = 3.

- Best MAE: 2.5821, with Min Leaf Size = 1 and Number of Variables = 4.

- Best MAPE: 0.1778, with Min Leaf Size = 1 and Number of Variables = 4.

- Best R-squared: 0.9415, with Min Leaf Size = 1 and Number of Variables = 3.

- C (cost/regularization): This controls the trade-off between allowing slack variables (errors) and forcing the decision boundary to be as tight as possible. A higher C makes the model focus more on correctly classifying all training points but risks overfitting.

- Gamma (γ): This defines the influence of individual training examples. Smaller values of gamma imply that each training point has a far-reaching influence, while higher values imply more localized influence.

- Epsilon (ε): This defines a margin of tolerance where no penalty is given to errors within a certain range. Epsilon controls the sensitivity of the model to prediction errors.

- C = 1.4513; ε = 0.0043; γ = 20.7363 for the RBF kernel;

- C = 0.3208 and ε = 0.0432 for the linear kernel;

- C = 23.6326; ε = 0.0521; γ = 0.0118 for sigmoid kernel.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Čolak, S.; Bulajić, B.Đ.; Ademović, N. Assessment of Selected Models for FRP-Retrofitted URM Walls under In-Plane Loads. Buildings 2021, 11, 559. [CrossRef]

- Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Ademović, N.; Pavić, G.; Kalman Šipoš, T. Strengthening techniques for masonry structures of cultural heritage according to recent Croatian provisions. Earthquakes and Structures 2018, 15, 473–485. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, C. Quantification of Bond-Slip Relationship for Externally Bonded FRP-to-Concrete Joints. J. Compos. Constr. 2013, 17, 673–686. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, S.; Huang, Z.; Sui, L.; Chen, Y. Explicit Neural Network Model for Predicting FRP-Concrete Interfacial Bond Strength Based on a Large Database. Compos. Struct. 2020, 240, 111998. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gravina, R. J.; Smith, S. T.; Visintin, P. Bond Strength and Bond Stress-Slip Analysis of FRP Bar to Concrete Incorporating Environmental Durability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 119860. [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Zhong, Q.; Peng, H.; Li, S. Selected Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting the Interfacial Bond Strength between FRPs and Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121456. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.; Haddad, M. Predicting FRP-concrete bond strength using artificial neural networks: A comparative analysis study. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, 38-49.

- Chen, S.-Z.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Han, W.-S.; Wu, G. Ensemble Learning Based Approach for FRP-Concrete Bond Strength Prediction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124230. [CrossRef]

- Barkhordari, M.S.; Armaghani, D.J.; Sabri, M.M.S.; Ulrikh, D.V.; Ahmad, M. The Efficiency of Hybrid Intelligent Models in Predicting Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Concrete Interfacial-Bond Strength. Materials 2022, 15, 3019. [CrossRef]

- Alabdullh, A.A.; Biswas, R.; Gudainiyan, J.; Khan, K.; Bujbarah, A.H.; Alabdulwahab, Q.A.; Amin, M.N.; Iqbal, M. Hybrid Ensemble Model for Predicting the Strength of FRP Laminates Bonded to the Concrete. Polymers 2022, 14, 3505. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Lee, D.-E.; Hu, G.; Natarajan, Y.; Preethaa, S.; Rathinakumar, A.P. Ensemble Machine Learning-Based Approach for Predicting of FRP–Concrete Interfacial Bonding. Mathematics 2022, 10, 231. [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R.; Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol., 2008, 77, 802–813. [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibsirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009.

- Kovačević, M.; Ivanišević, N.; Petronijević, P.; Despotović, V. Construction cost estimation of reinforced and prestressed concrete bridges using machine learning. Građevinar, 2021, 73, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, H.; Olsen, R.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Wadsworth, OH, USA, 1984.

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci., 1997, 55, 119–139. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232.

- Vapnik, V. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995.

- Kecman, V. Learning and Soft Computing: Support. In Vector Machines, Neural Networks, and Fuzzy Logic Models; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001.

- Smola, A.J.; Sholkopf, B. A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat. Comput. 2004, 14, 199–222.

- Rasmussen, C.E.; Williams, C.K. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006.

- Searson, D.P.; Leahy, D. E.; Willis , M.J. GPTIPS: An Open Source Genetic Programming Toolbox For Multigene Symbolic Regression, Proceeding of International MultiConference of Engineers and Computer Scieintist Vol. I, IMECS 2010, March 17 – 19, 2010, Hong Kong.

- Kovačević, M.; Lozančić, S.; Nyarko, E.K.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M. Application of Artificial Intelligence Methods for Predicting the Compressive Strength of Self-Compacting Concrete with Class F Fly Ash. Materials 2022, 15, 4191. [CrossRef]

- Hagan, M.T.; Menhaj, M.B., Training Feedforward Networks with Marquardt Algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks,1994, 5(6), 989-993.

- Adhikary, B.; Mutsuyoshi, H. Study on the Bond between Concrete and Externally Bonded CFRP Sheet. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Concrete Structures (FRPRCS-5); Thomas Telford Publishing: London, 2001; pp. 371–378.

- Bilotta, A.; Di Ludovico, M.; Nigro, E. FRP-to-Concrete Interface Debonding: Experimental Calibration of a Capacity Model. Compos. Part B Eng. 2011, 42, 1539–1553. [CrossRef]

- Bilotta, A.; Ceroni, F.; Di Ludovico, M.; Nigro, E.; Pecce, M.; Manfredi, G. Bond Efficiency of EBR and NSM FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Members. J. Compos. Constr. 2011, 15, 629–638. [CrossRef]

- Bimal, B.A.; Hiroshi, M. Study on the Bond Between Concrete and Externally Bonded CFRP Sheet. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on FRP Reinforcement for Concrete Structures; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, 2001; pp. 371–378.

- Pellegrino, C.; Tinazzi, D.; Modena, C. Experimental Study on Bond Behavior Between Concrete and FRP Reinforcement. J. Compos. Constr. 2008, 12, 180–188. [CrossRef]

- Chajes, M.J.; Finch, W.W., Jr.; Januszka, T.F.; Thomson, T.A., Jr. Bond and Force Transfer of Composite-Material Plates Bonded to Concrete. Struct. J. 1996, 93, 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Czaderski, C.; Olia, S. EN-Core Round Robin Testing Program – Contribution of Empa. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on FRP Composites in Civil Engineering (CICE 2012); Rome, Italy, June 13–15, 2012; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.dora.lib4ri.ch/empa/islandora/object/empa:9237.

- Dai, J.-G.; Sato, Y.; Ueda, T. Improving the load transfer and effective bond length for FRP composites bonded to concrete. Proc. Jpn. Concr. Inst. 2002, 24(1), 1423–1428.

- Faella, C.; Nigro, E.; Martinelli, E.; Sabatino, M.; Salerno, N.; Mantegazza, G. Aderenza tra calcestruzzo e Lamine di FRP utilizzate come placcaggio di elementi inflessi. Parte I: Risultati sperimentali. In Proceedings of the XIV Congresso C.T.E., Mantova, Italy, 2002; pp. 7–8.

- Fen, Z.L.; Gu, X.L.; Zhang, W.P.; Liu, L.M. Experimental study on bond behavior between carbon fiber reinforced polymer and concrete. Structural Engineering 2008, 24(4).

- Hosseini, A.; Mostofinejad, D. Effective Bond Length of FRP-to-Concrete Adhesively-Bonded Joints: Experimental Evaluation of Existing Models. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2014, 48, 150–158. [CrossRef]

- Kanakubo, T.; Nakaba, K.; Yoshida, T.; Yoshizawa, H. A Proposal for the Local Bond Stress–Slip Relationship between Continuous Fiber Sheets and Concrete. Concrete Research and Technology 2001, 12(1), 33–43. [In Japanese. [CrossRef]

- Kamiharako, A.; Shimomura, T.; Maruyama, K. The Influence of the Substrate on the Bond Behavior of Continuous Fiber Sheet. Proc. Jpn. Concr. Inst. 2003, 25(3), 1735–1740.

- Ko, H.; Matthys, S.; Palmieri, A.; Sato, Y. Development of a simplified bond stress–slip model for bonded FRP–concrete interfaces. Construction and Building Materials 2014, 68, 142–157. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Effect of Concrete Strength on Interfacial Bond Behavior of CFRP–Concrete; Ph.D. Thesis, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China, 2012. [In Chinese.].

- Lu, X.Z.; Ye, L.P.; Teng, J.G.; Jiang, J.J. Meso-Scale Finite Element Model for FRP Sheets/Plates Bonded to Concrete. Engineering Structures 2005, 27(4), 564–575. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Asano, Y.; Sato, Y.; Ueda, T.; Kakuta, Y. A study on bond mechanism of carbon fiber sheet. Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Non-Metallic (FRP) Reinforcement for Concrete Structures, Japan, 1997; pp. 279–285.

- Nakaba, K.; Kanakubo, T.; Furuta, T.; Yoshizawa, H. Bond behavior between fiber-reinforced polymer laminates and concrete. ACI Struct. J. 2001, 98(3), 359–367.

- Pham, H.B.; Al-Mahaidi, R. Modelling of CFRP–Concrete Shear-Lap Tests. Construction and Building Materials 2007, 21(4), 727–735. [CrossRef]

- Ren, H. Study on Basic Mechanical Properties and Long-Term Mechanical Properties of Concrete Structures Strengthened with Fiber Reinforced Polymer; Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2003. [In Chinese.].

- Savoia, M.; Ferracuti, B. Strengthening of RC Structure by FRP: Experimental Analyses and Numerical Modelling; Ph.D. Thesis, DISTART, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2006.

- Savoia, M.; Bilotta, A.; Ceroni, F.; Di Ludovico, M.; Fava, G.; Ferracuti, B.; et al. Experimental Round Robin Test on FRP–Concrete Bonding. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Polymer Reinforcement for Concrete Structures (FRPRCS-9); Sydney, Australia, 13–15 July 2009.

- Sharma, S.K.; Mohamed Ali, M.S.; Goldar, D.; Sikdar, P.K. Plate–Concrete Interfacial Bond Strength of FRP and Metallic Plated Concrete Specimens. Composites Part B: Engineering 2006, 37(1), 54–63. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z. Experimental Study on the Performance of Concrete Beams Strengthened with GFRP; Master's Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2002. [In Chinese.].

- Taljsten, B. Plate Bonding: Strengthening of Existing Concrete Structures with Epoxy Bonded Plates of Steel or Fibre Reinforced Plastics; Ph.D. Thesis, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 1994.

- Takeo, M.; Tanaka, T. Analytical solution for bond-slip behavior in FRP-concrete systems. Compos. Struct. 2020, 240, 111998.

- Toutanji, H.; Saxena, P.; Zhao, L.; Ooi, T. Prediction of Interfacial Bond Failure of FRP–Concrete Surface. J. Compos. Constr. 2007, 11(4), 427–436. [CrossRef]

- Ueda, T.; Sato, Y.; Asano, Y. Experimental Study on Bond Strength of Continuous Carbon Fiber Sheet. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Polymer Reinforcement for Reinforced Concrete Structures; ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1999; pp. 407–416.

- Ueno, S.; Toutanji, H.; Vuddandam, R. Introduction of a Stress State Criterion to Predict Bond Strength between FRP and Concrete Substrate. Journal of Composites for Construction 2015, 19(1), 04014028. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Jiang, C. Quantification of Bond-Slip Relationship for Externally Bonded FRP-to-Concrete Joints. Journal of Composites for Construction 2013, 17(5), 673–686. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.S.; Yuan, H.; Yoshizawa, H.; Kanakubo, T. Experimental/Analytical Study on Interfacial Fracture Energy and Fracture Propagation Along FRP–Concrete Interface. In Fracture Mechanics for Concrete Materials: Testing and Applications; SP-201; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2001.

- Woo, H.; Lee, H. Bond strength degradation in FRP-strengthened concrete under cyclic loads. Compos. Struct. 2004, 64, 7–16.

- Fu, Q.; Xu, J.; Jian, G.G.; Yu, C. Bond Strength between CFRP Sheets and Concrete. In FRP Composites in Civil Engineering; Teng, J.G., Ed.; Proceedings of the International Conference on FRP Composites in Civil Engineering (CICE 2001), Hong Kong, China, 12–15 December 2001; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 357–364.

- Yao, J. Debonding in FRP-Strengthened RC Structures; Ph.D. Thesis, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China, 2004.

- Yuan, H.; Wu, Z.S.; Yoshizawa, H. Theoretical solutions on interfacial stress transfer of externally bonded steel/composite laminates. JSCE 2001, 18, 27–39.

- Zhang, H.; Smith, S.T. Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (FRP)-to-Concrete Joints Anchored with FRP Anchors: Tests and Experimental Trends. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2013, 40(8), 731–742. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M. Study on Bond Behavior of Carbon Fiber Sheet and Concrete Base. In Proceedings of the First Chinese Academic Conference on FRP-Concrete Structures; Building Research Institute of Ministry of Metallurgical Industry: Beijing, China, 2000. [In Chinese.].

- Zhou, Y.W. Analytical and Experimental Study on the Strength and Ductility of FRP–Reinforced High Strength Concrete Beam; Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China. [In Chinese.].

- Searson, D.P. GPTIPS 2: An Open-Source Software Platform for Symbolic Data Mining. In Handbook of Genetic Programming Applications; Gandomi, A.H., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Chapter 22.

| Reference | Num.of tests |

(MPa) |

GPa) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(kN) |

| Adhikary and Mutsuyoshi [27] | 7 | 24-36.5 | 230 | 0.11-0.33 | 100-150 | 100 | 150 | 16.75-28.25 |

| Bilotta et al. [28] | 29 | 21.46-26 | 170-241 | 0.166-1.4 | 100-400 | 50-100 | 150 | 17.24-33.56 |

| Bilotta et al. [29] | 13 | 19 | 109-221 | 1.2-1.7 | 300 | 60-100 | 160 | 29.86-54.79 |

| Bimal and Hiroshi [30] | 7 | 24-36.5 | 230 | 0.111-0.334 | 100-150 | 100 | 150 | 16.8-28.3 |

| Carlo et al. [31] | 14 | 58-63 | 230-390 | 0.165-0.495 | 65-130 | 50 | 100 | 12.1-29.8 |

| Chajes et al. [32] | 15 | 24-48.87 | 108.48 | 1.016 | 51-203 | 25.4 | 152.4-228.6 | 8.09-12.81 |

| Czaderski and Olia [33] | 8 | 32-33 | 165-175 | 1.23-1.68 | 300 | 100 | 150 | 43.5-56.1 |

| Dai et al. [34] | 19 | 33.1-35 | 74-230 | 0.11-0.59 | 210-330 | 100 | 400 | 15.6-51 |

| Faella et al. [35] | 3 | 32.78-37.55 | 140 | 1.4 | 200-250 | 50 | 150 | 31-39.78 |

| Fen et al. [36] | 11 | 8-36 | 240.72-356.75 | 0.111 | 50-120 | 50-100 | 150 | 7.13-17.34 |

| Hoseini and Mostofinejad [37] | 22 | 36.5-41.1 | 238 | 0.131 | 20-250 | 48 | 150 | 7.58-10.12 |

| Kanakubo et al. [38] | 12 | 23.8-57.6 | 252.2-425.1 | 0.083-0.334 | 300 | 50 | 100 | 7-25.6 |

| Kamiharako et al. [39] | 17 | 34.9-75.5 | 270 | 0.111-0.222 | 100-250 | 10-90 | 100 | 3.1-14.9 |

| Ko et al. [40] | 13 | 27.7-31.4 | 165-210 | 1-1.4 | 300 | 60-100 | 150 | 27.5-56.5 |

| Liu [41] | 57 | 16-51.6 | 272.66 | 0.167 | 50-300 | 50 | 100 | 10.97-23.87 |

| Lu et al. [42] | 3 | 47.64-64.08 | 230-390 | 0.22-0.501 | 200-250 | 40-100 | 100-500 | 14.1-38 |

| Maeda et al. [43] | 5 | 40.8-44.91 | 230 | 0.11-0.22 | 65-300 | 50 | 100 | 5.8-16.25 |

| Nakaba et al. [44] | 41 | 24.41-65.73 | 124.5-425 | 0.167-2 | 250-300 | 40-50 | 100 | 8.73-27.24 |

| Pham and Al-Mahaidi [45] | 23 | 44.57 | 209 | 0.176 | 60-220 | 70-100 | 140 | 18.8-42.8 |

| Ren [46] | 28 | 22.96-46.07 | 83.03-207 | 0.33-0.507 | 60-150 | 20-80 | 150 | 4.61-22.8 |

| Savoia and Ferracuti [47] | 14 | 52.6 | 165-291.02 | 0.13-1.2 | 200-400 | 50-80 | 150 | 14.4-41 |

| Savoia et al. [48] | 20 | 26 | 180-241 | 0.166-1.2 | 100-400 | 80-100 | 150 | 18.97-40 |

| Sharma et al. [49] | 24 | 23.76-28.66 | 32.7-300 | 1.2-4 | 100-300 | 30-50 | 100 | 12.5-46.35 |

| Tan [50] | 6 | 30.8 | 97-235 | 0.111-0.169 | 70-130 | 50 | 100 | 6.46-11.43 |

| Täljsten [51] | 5 | 41.2-68.33 | 162-170 | 1.2-1.25 | 100-300 | 50 | 200 | 17.3-35.1 |

| Takeo et al. [52] | 25 | 24.7-29.25 | 230-373 | 0.111-0.501 | 100-300 | 40 | 100 | 6.75-14.35 |

| Toutanji et al. [53] | 10 | 17.0-61.5 | 110 | 0.495-0.99 | 100 | 50 | 200 | 11.64-19.03 |

| Ueda et al. [54] | 15 | 23.79-48.85 | 230-372 | 0.11-0.55 | 65-300 | 10-100 | 100-500 | 2.4-38 |

| Ueno et al. [55] | 40 | 23-74.5 | 42.625-43.537 | 1.03-1.8 | 200-230 | 40 | 80 | 9.52-18.29 |

| Wu and Jiang [56] | 65 | 25.3-59.02 | 238.1-248.3 | 0.167 | 30-400 | 50 | 150 | 7.38-30.15 |

| Wu et al. [57] | 22 | 65.73 | 23.9-390 | 0.083-1 | 250-300 | 40-100 | 100 | 11.8-27.25 |

| Woo and Lee [58] | 51 | 24-40 | 152.2 | 1.4 | 50-300 | 10-50 | 200 | 4.55-27.8 |

| Xu et al. [59] | 24 | 24.1-70 | 230 | 0.17-0.84 | 50-300 | 30-70 | 100 | 7.8-31.13 |

| Yao [60] | 59 | 19.12-27.44 | 22.5-256 | 0.165-1.27 | 75-240 | 25-100 | 100-150 | 4.75-19.07 |

| Yuan et al. [61] | 1 | 23.79 | 256 | 0.165 | 190 | 25 | 150 | 5.74 |

| Zhang et al. [62] | 20 | 38.9-43.5 | 94-227 | 0.262-0.655 | 250 | 50-150 | 200-250 | 13.03-52.49 |

| Zhao et al. [63] | 5 | 16.4-29.36 | 240 | 0.083 | 100-150 | 100 | 150 | 11-12.75 |

| Zhou [64] | 102 | 48.56-74.67 | 71-237 | 0.111-0.341 | 20-200 | 15-150 | 150 | 3.75-28 |

|

(mm) |

(MPa) |

(GPa) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(kN) |

|

| min | 80.00 | 8.00 | 22.50 | 0.08 | 10.00 | 20.00 | 2.40 |

| max | 500.00 | 74.67 | 425.10 | 4.00 | 150.00 | 400.00 | 56.50 |

| average | 144.31 | 39.38 | 203.66 | 0.50 | 57.62 | 175.42 | 17.80 |

| mode | 150.00 | 48.56 | 230.00 | 0.17 | 50.00 | 100.00 | 11.90 |

| median | 150.00 | 36.50 | 230.00 | 0.17 | 50.00 | 150.00 | 15.73 |

| std | 56.93 | 15.23 | 77.97 | 0.53 | 26.57 | 102.31 | 10.13 |

|

(mm) |

(MPa) |

(GPa) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(kN) |

|

| min | 56.93 | 8.00 | 22.50 | 0.08 | 10.00 | 20.00 | 2.40 |

| max | 500.00 | 74.67 | 425.10 | 4.00 | 150.00 | 400.00 | 56.50 |

| average | 144.84 | 38.94 | 208.34 | 0.53 | 57.50 | 180.23 | 18.55 |

| mode | 150.00 | 65.73 | 230.00 | 0.17 | 50.00 | 100.00 | 12.75 |

| median | 150.00 | 36.27 | 230.00 | 0.17 | 50.00 | 162.50 | 16.47 |

| std | 68.25 | 15.03 | 75.95 | 0.58 | 25.21 | 105.20 | 9.85 |

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | tStat | pValue |

| (Intercept) | -15.9200 | 2.8688 | -5.5492 | 4.3568× |

| -0.0393 | 0.0138 | -2.8525 | 0.0045 | |

| 0.3682 | 0.0702 | 5.2473 | 2.1625× | |

| 0.0695 | 0.0098 | 7.0878 | 3.9461× | |

| 0.0654 | 0.0476 | 1.3739 | 0.1700 | |

| 0.0574 | 0.0112 | 5.1353 | 3.8429× | |

| 0.0443 | 0.0054 | 8.2612 | 9.6963× | |

| 0.0014 | 0.0002 | 6.0212 | 3.0620× | |

| 0.1313 | 0.0145 | 9.0761 | 1.7139× | |

| -0.0005 | 0.0001 | -3.9565 | 8.5421× | |

| -0.0001 | 0.0001 | -2.4285 | 0.0155 | |

| -0.0025 | 0.0007 | -3.3629 | 8.2189× | |

| -0.0001 | 0.0000 | -4.3966 | 1.3068× | |

| -0.0009 | 0.0002 | -3.8854 | 1.1386× | |

| -0.00007 | 0.0000 | -3.4915 | 5.1660× |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE/100 | R |

| Lin. kernel | 8.7154 | 6.6468 | 0.2105 | 0.7751 |

| RBF kernel | 4.9646 | 3.5352 | 0.1171 | 0.9332 |

| Sig. kernel | 8.7104 | 6.6094 | 0.2073 | 0.7718 |

| GP Model Covariance Function | Covariance Function Parameters | |||

| Exponential | ||||

| 48.8828 | 35.9025 | |||

| Squared Exponential | ||||

| 1.1564 | 11.6670 | |||

| Matern 3/2 | ||||

| 1.9430 | 12.5620 | |||

| Matern 5/2 | ||||

| 1.6073 | 12.0472 | |||

| Rational Quadratic | ||||

| 1.9747 | 0.0057 | 39.8560 | ||

| Covariance Function Parameters | |||||

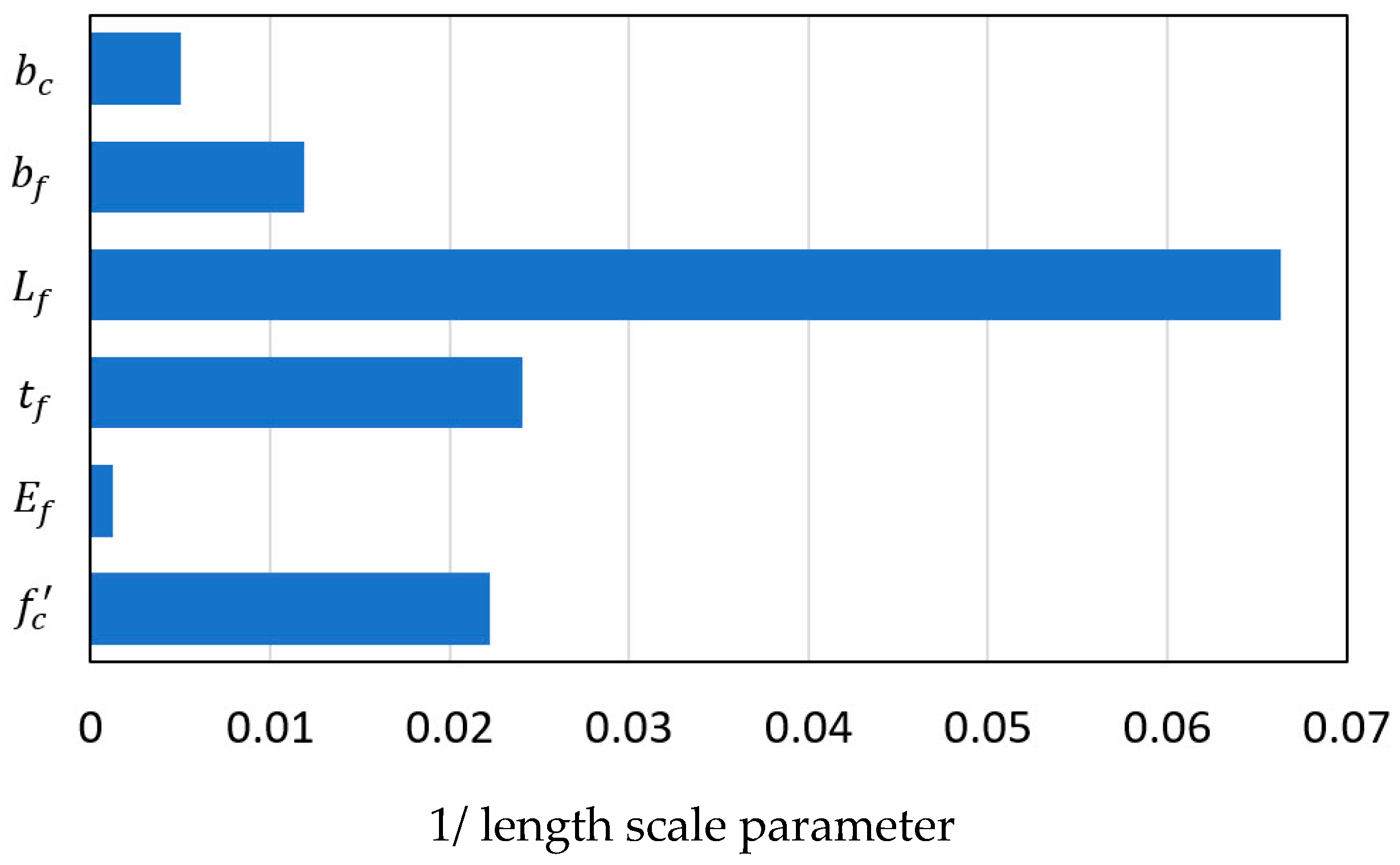

| ARD Exponential: ;=44.4870; =0.8339 | |||||

| 45.0052 | 813.3275 | 41.5953 | 15.0703 | 83.9007 | 199.8780 |

| ARD Squared exponential: =13.0762 | |||||

| 0.1181 | 6.1165 | 0.1452 | 0.3453 | 2.0239 | 1.5321 |

| ARD Matern 3/2: =11.8722 | |||||

| 0.4342 | 10.3369 | 0.8032 | 0.2128 | 1.7551 | 3.0059 |

| ARD Matern 5/2: =11.2938 | |||||

| 0.2738 | 8.1979 | 0.6294 | 0.1177 | 1.1174 | 2.2108 |

| ARD Rational quadratic: =0.0082; =40.2700 | |||||

| 1.2252 | 23.3200 | 1.2758 | 0.3892 | 2.1230 | 5.8575 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE/100 | R |

| Exp. | 3.2790 | 2.1928 | 0.1498 | 0.9558 |

| Sq.Exp. | 3.8110 | 2.6042 | 0.1794 | 0.9395 |

| Mattern 3/2 | 3.5651 | 2.3879 | 0.1632 | 0.9475 |

| Mattern 5/2 | 3.6651 | 2.4752 | 0.1697 | 0.9443 |

| Rat.Quadratic | 3.3152 | 2.2421 | 0.1593 | 0.9551 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE/100 | R |

| ARD Exp. | 2.9039 | 1.8953 | 0.1257 | 0.9650 |

| ARD Sq.Exp. | 3.4447 | 2.3562 | 0.1590 | 0.9511 |

| ARD Mattern 3/2 | 2.8671 | 1.9319 | 0.1329 | 0.9658 |

| ARD Mattern 5/2 | 3.0073 | 2.0360 | 0.1410 | 0.9623 |

| ARD Rat.Quadratic | 2.9167 | 1.9377 | 0.1323 | 0.9647 |

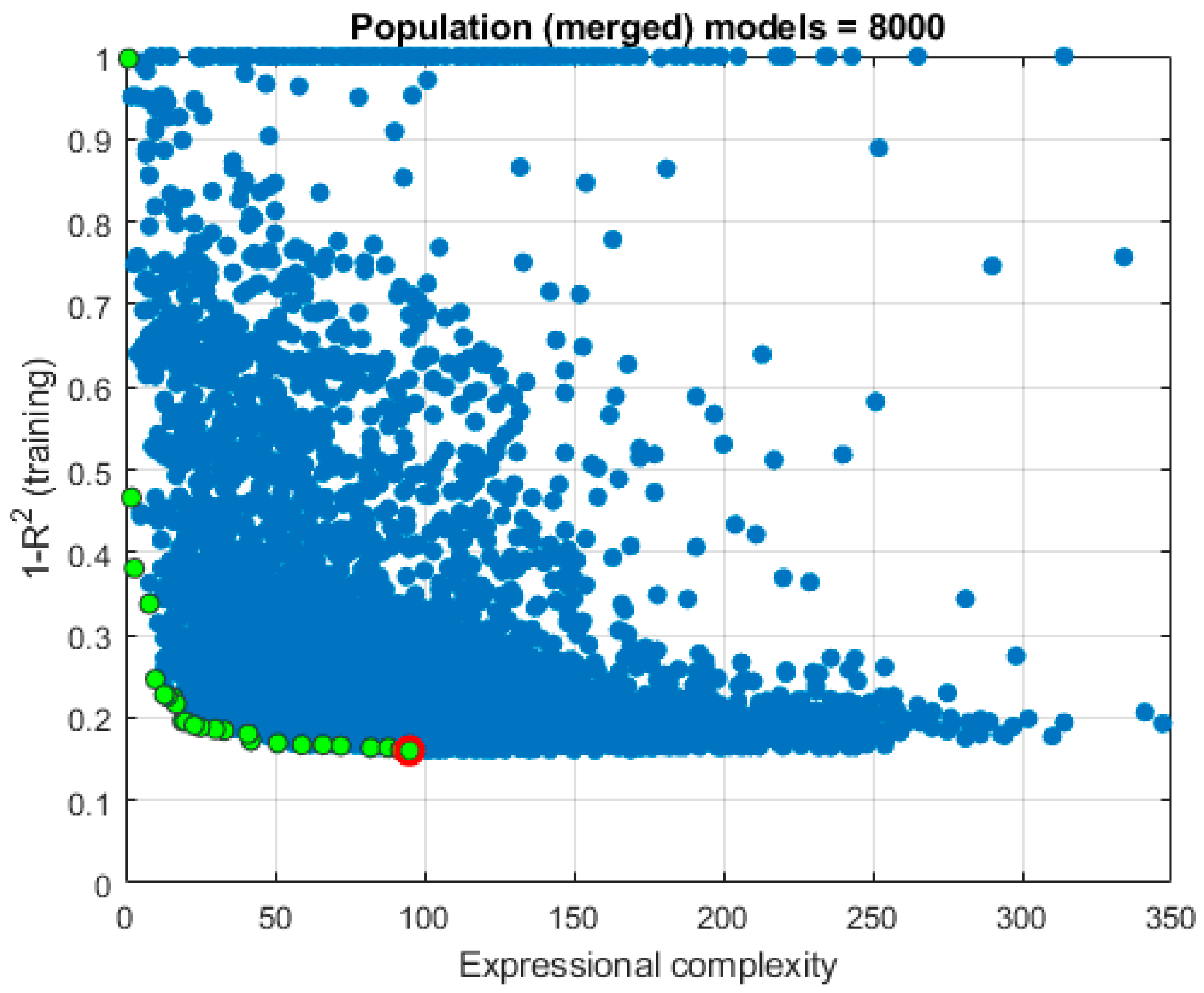

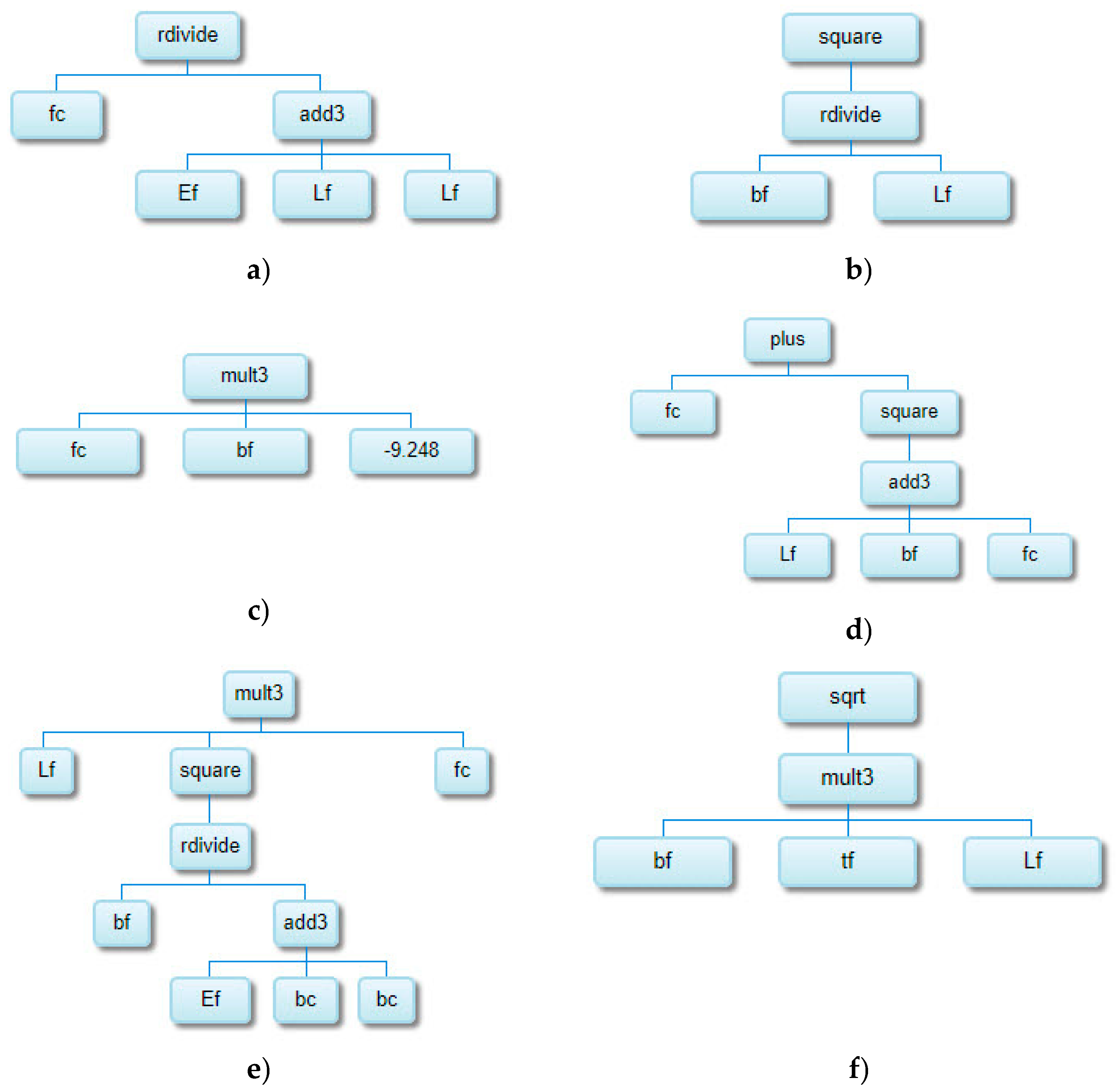

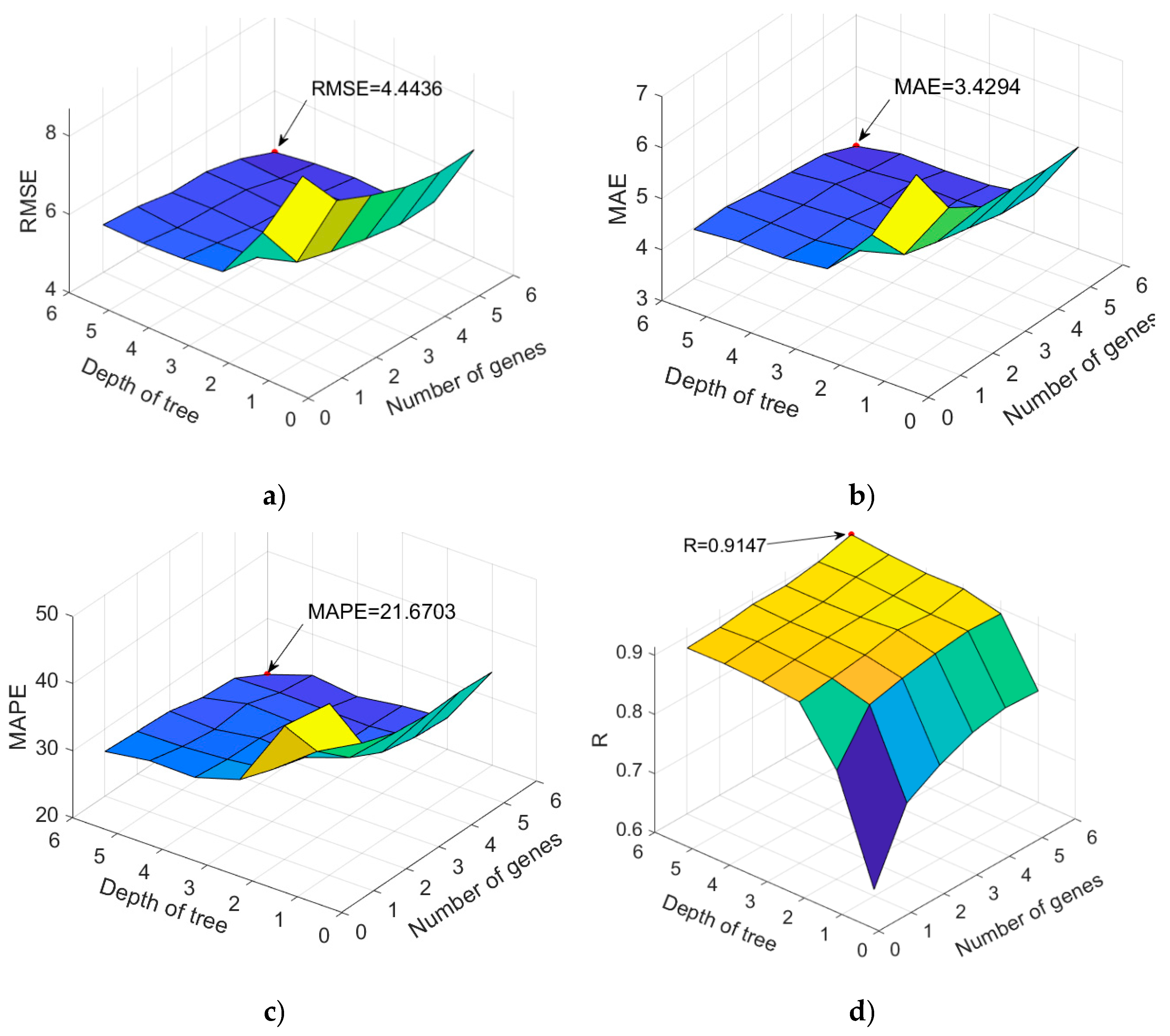

| Parameter | Setting |

| Function set | times, minus, plus, rdivide, square, exp, log, mult3, sqrt, cube, power |

| Population size | From 100 to 1000 with step 100 |

| Number of generations | 1000 |

| Max number of genes | 6 |

| Max tree depth | 6 |

| Tournament size | 2 |

| Elitism | 0.05% of population |

| Crossover probability | 0.84 |

| Mutation probability | 0.14 |

| Probability of Pareto tournament | 0.70 |

| Model ID | Model complexity |

RMSE | MAE | MAPE/100 | R |

| 7961 | 95 | 4.4436 | 3.4294 | 0.2167 | 0.9147 |

| 7570 | 92 | 4.6349 | 3.6170 | 0.2417 | 0.9079 |

| 1766 | 82 | 4.8264 | 3.7418 | 0.2456 | 0.9004 |

| 3867 | 88 | 4.8137 | 3.7101 | 0.2404 | 0.9004 |

| 7161 | 72 | 4.5985 | 3.5375 | 0.2362 | 0.9095 |

| 7164 | 66 | 4.6936 | 3.6328 | 0.2407 | 0.9056 |

| 7167 | 59 | 4.6545 | 3.5922 | 0.2383 | 0.9056 |

| 6726 | 51 | 4.6894 | 3.5855 | 0.2383 | 0.9059 |

| 6959 | 42 | 4.6829 | 3.5373 | 0.2292 | 0.9061 |

| 7292 | 41 | 4.9642 | 3.7915 | 0.2514 | 0.8941 |

|

|

|

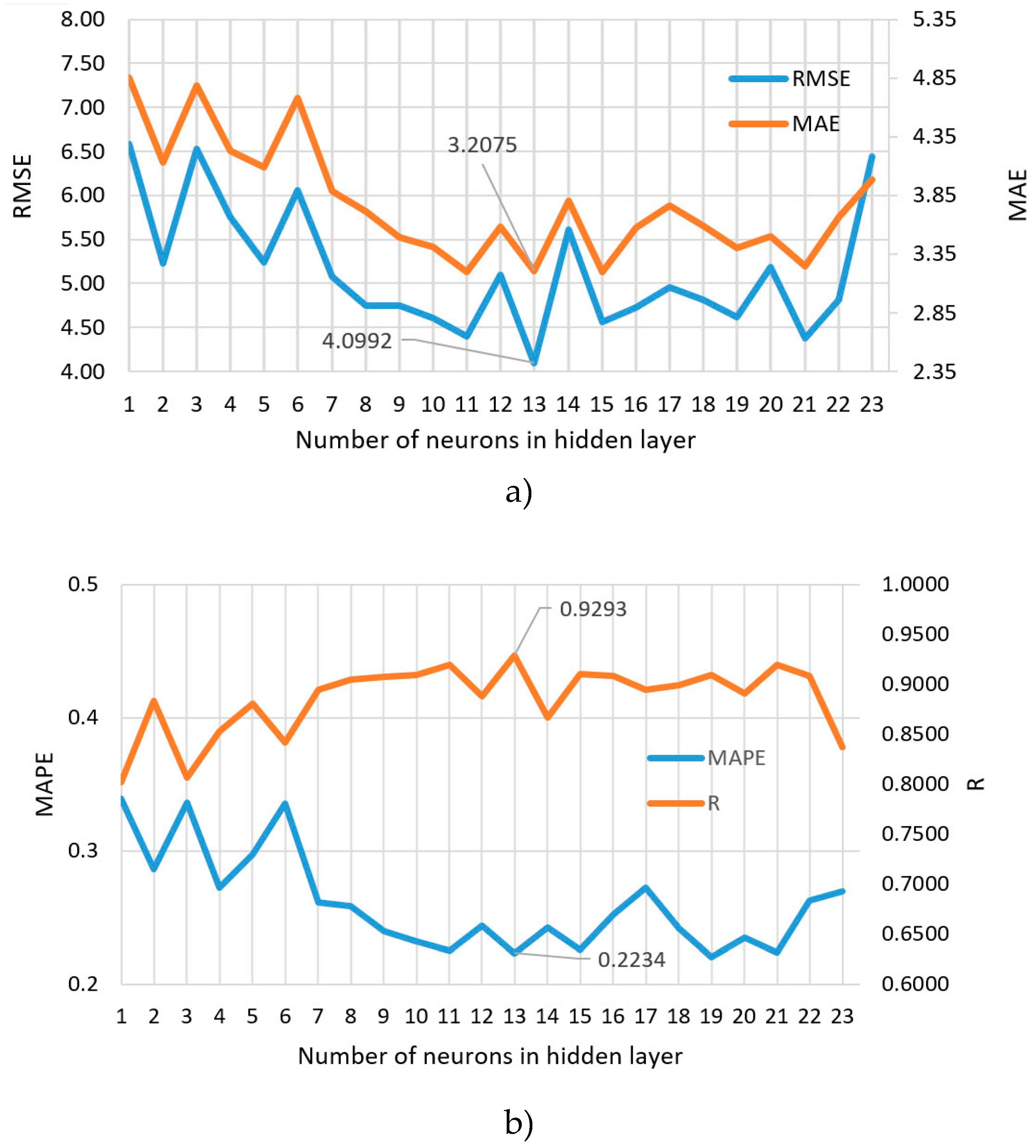

| Parameter | Value |

| Epoch limit | 1000 |

| MSE target (performance) | 0 |

| Gradient limit | 1.00 × |

| Mu value | Range from 0.005 to 1.00 × |

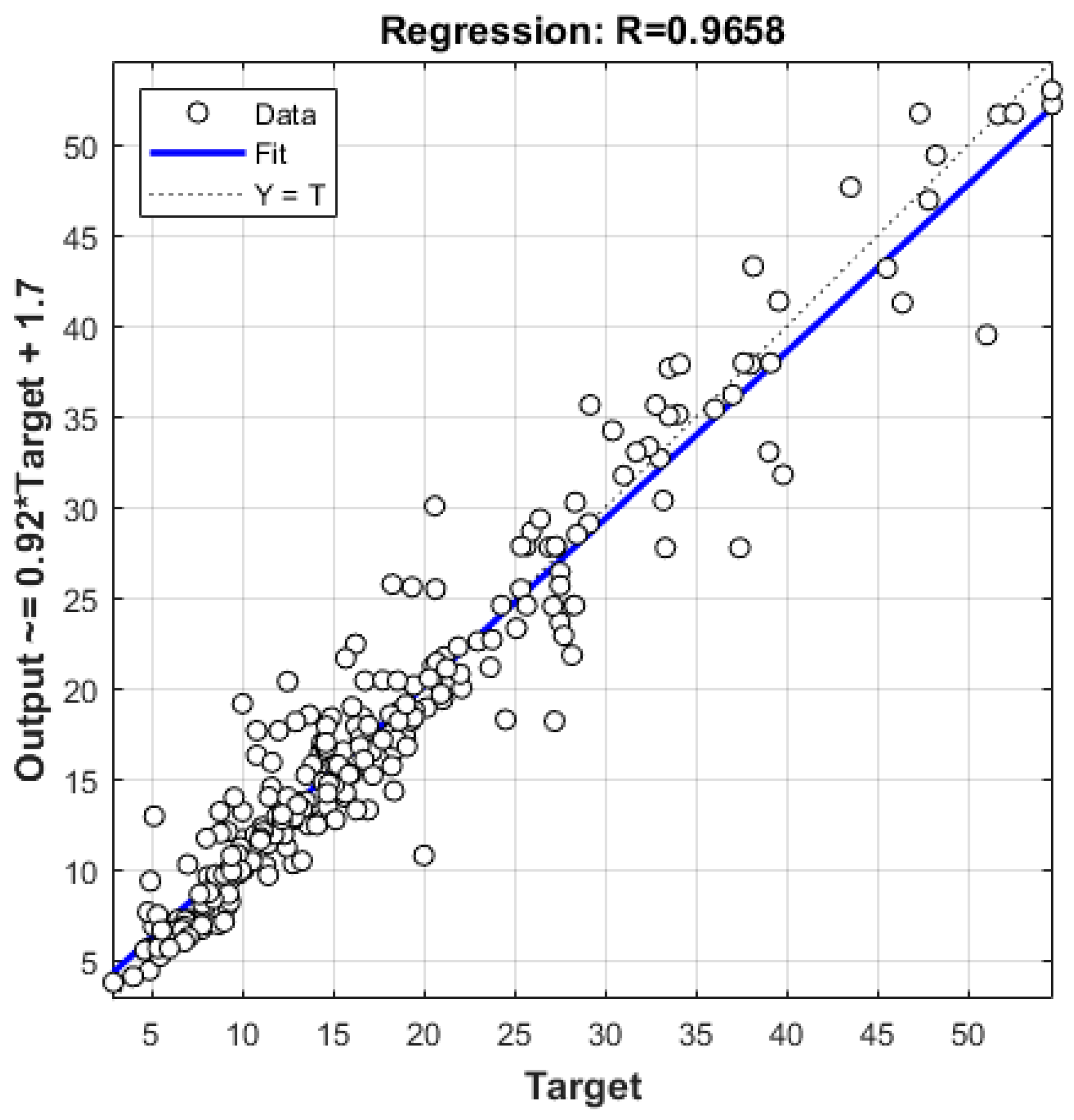

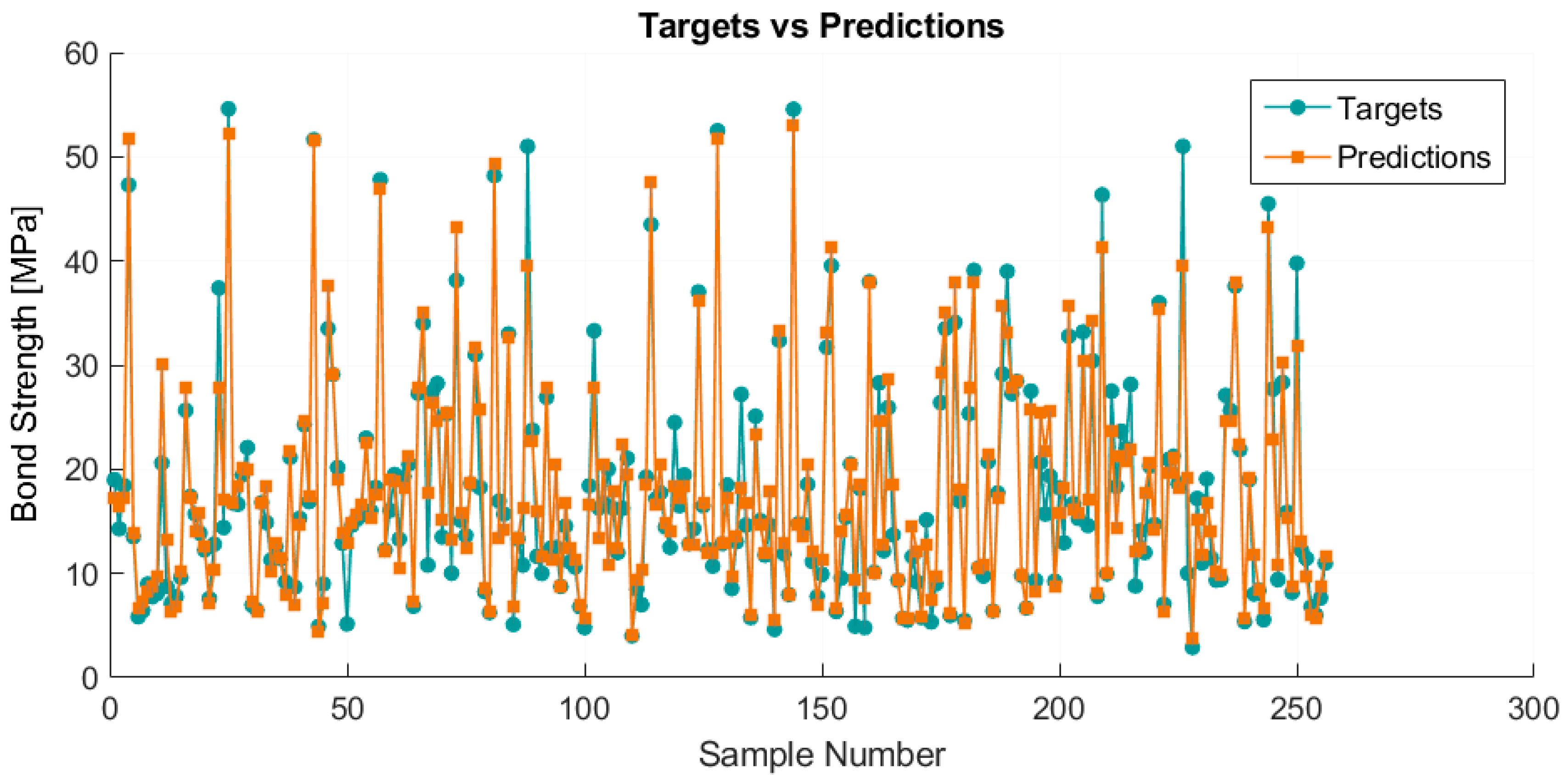

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE/100 | R |

| Linear with interaction | 4.9278 | 3.8491 | 0.2748 | 0.8955 |

| Gradient Boosted | 3.3427 | 2.2603 | 0.1559 | 0.9536 |

| Random Forest (64 splits) | 3.7860 | 2.5821 | 0.1778 | 0.9415 |

| TreeBagger | 3.8302 | 2.5847 | 0.1790 | 0.9399 |

| SVR RBF | 4.9646 | 3.5352 | 0.1171 | 0.9332 |

| GPR Exponential | 3.2790 | 2.1928 | 0.1498 | 0.9558 |

| GPR ARD Exponential | 2.8671 | 1.9319 | 0.1329 | 0.9658 |

| MGGP | 4.4436 | 3.4294 | 0.2167 | 0.9147 |

| MGGP simplified | 4.6829 | 3.5373 | 0.2292 | 0.9061 |

| NN 6-13-1 | 4.0992 | 3.2075 | 0.2234 | 0.9293 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).