Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Nanos, initially identified in Drosophila melanogaster (fly) as a morphogen essential for body patterning and germ cell development, is a highly conserved RNA-binding protein critical for germ cell formation across species. Nanos dysfunction leads to infertility from flies to humans. While Drosophila has a single nanos gene, paralogs (nanos1-3) exist in species like Danio rerio (zebrafish), Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm), Xenopus laevis (frog), and mammals, each with distinct reproductive roles. Animal germ cells contain a characteristic perinuclear structure called nuage built of RNAs and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), with nanos as one of its most conserved components. Nuage is essential for germ cell specification, development, maintenance, and integrity across species, exhibiting variable cytoplasmic sub-localizations, structure and shape depending on the sex and developmental stage. It gives rise to cytoplasmic germ granules, basic ribonucleoprotein (RNP) condensates unique to germ cells. This review examines nanos' role within nuage and germ granules across model organisms and highlights key questions regarding its biological significance, particularly in human reproduction.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Nanos’ Structure and Function in Germ Cells

2. Nanos, a Component of Nuage—A Hallmark Structure of Germ Cells Across Animal Species

2.1. Nanos Implication in the Nuage Life Cycle in D. melanogaster

2.2. C. elegans nanos2-Containing Germ Granules Associates with Nuclear Pores

2.3. Xenopus nanos1 Activity within the Oocyte’s Balbiani Body

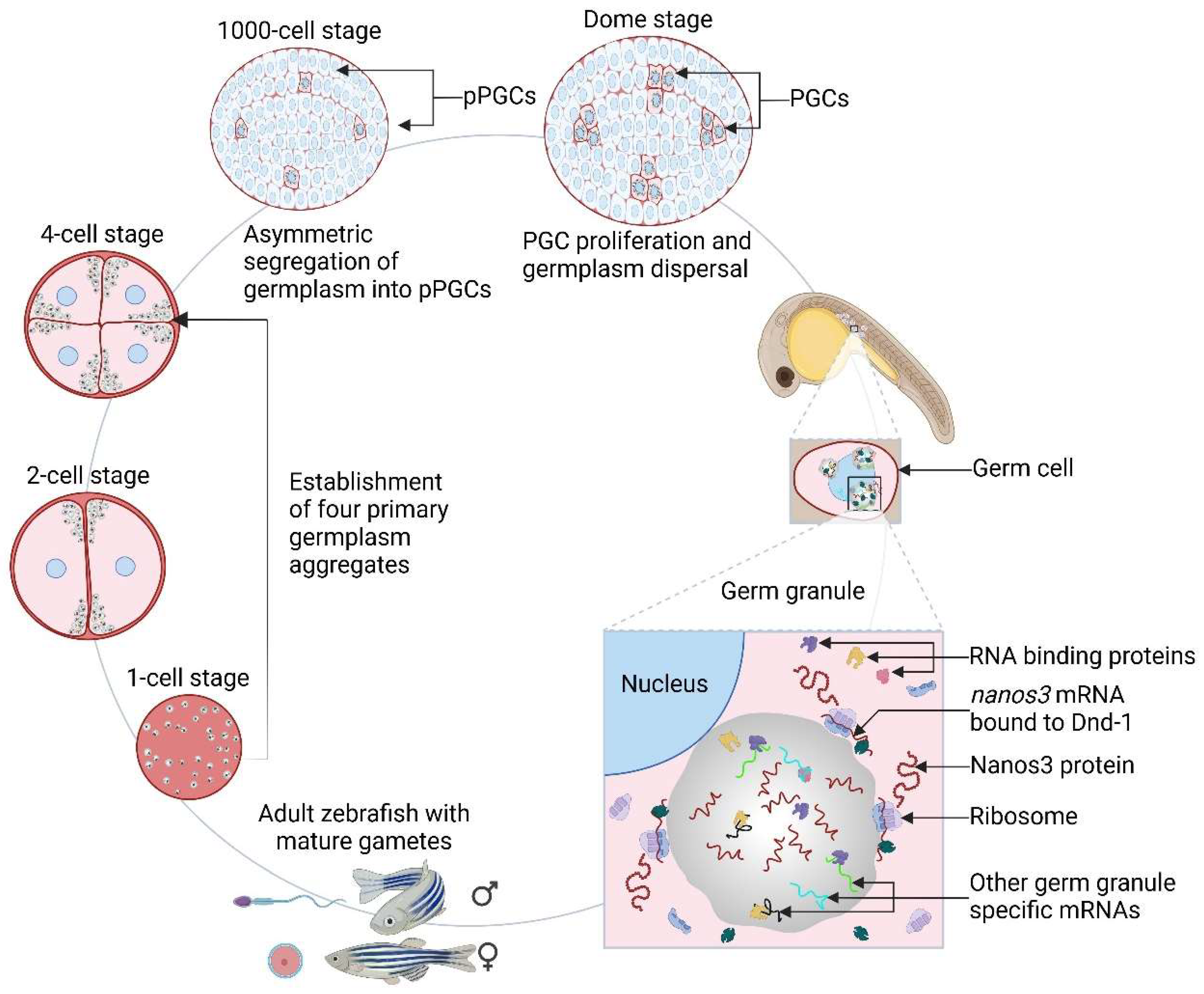

2.4. Nanos1 mRNA Localization and Post-Transcriptional Regulation in D. rerio Germ Cell Development

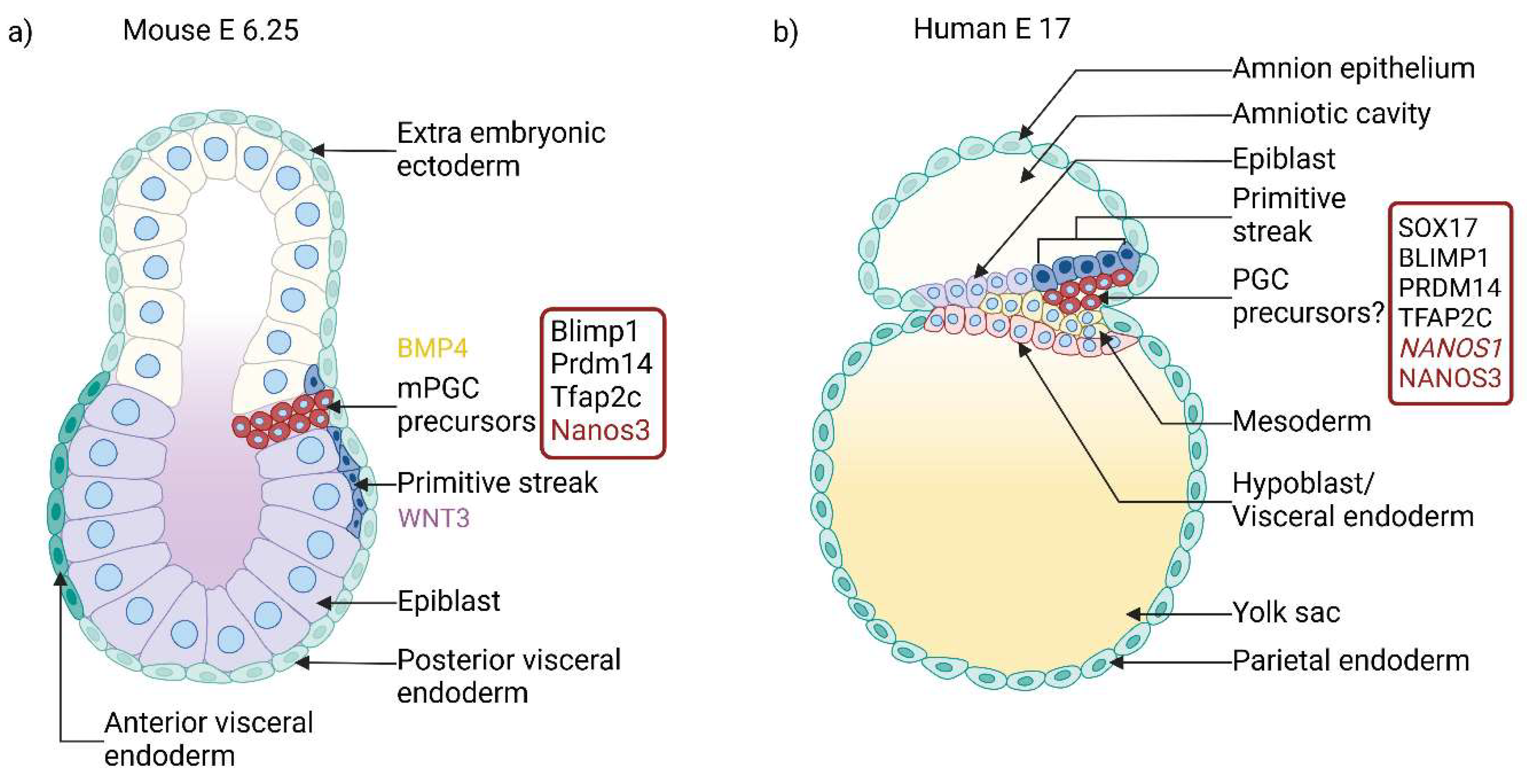

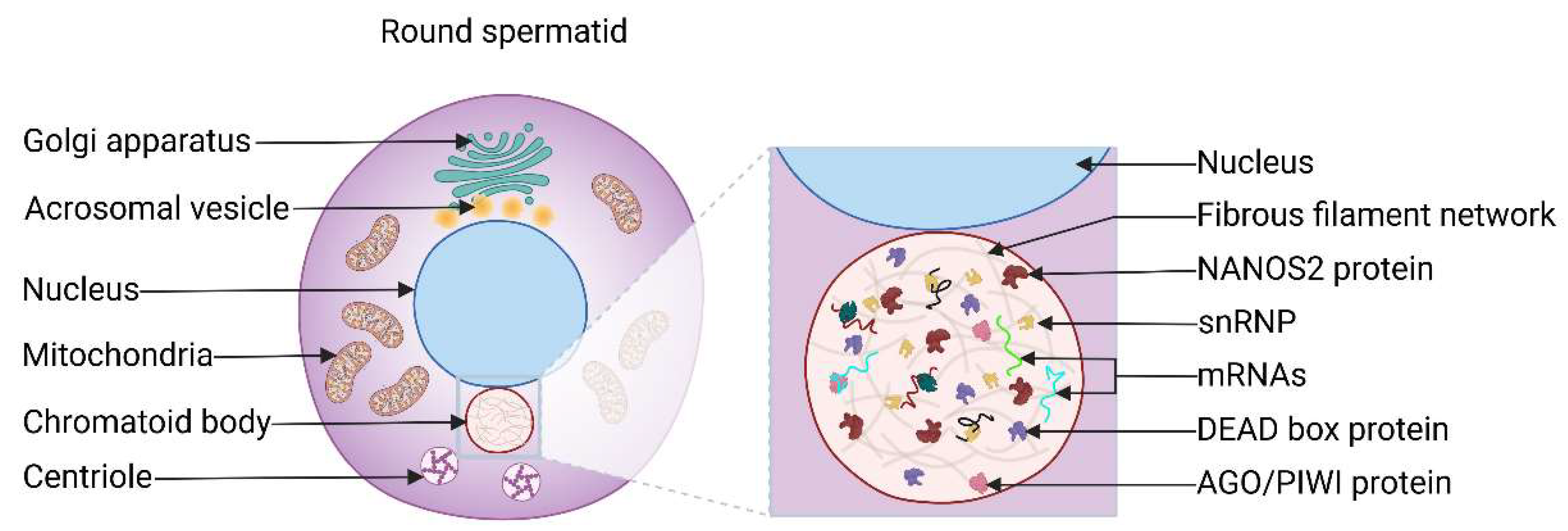

2.5. Mammalian Nanos Homologues Are Also Present in Nuage

3. The Ubiquitous Cytoplasmic Granules—Their Role in Germ Cells

3.1. Processing Bodies

3.2. Stress Granules

4. Significance of 3’UTR Mediated Post-Transcriptional Regulation in Germ Cell Granules

5. Germ Granules and Nanos: Dynamic Hubs of Post-Transcriptional Regulation and Germline Integrity

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- White, J.A.; Heasman, J. , Maternal control of pattern formation in Xenopus laevis. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol 2008, 310, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatarama, T.; Lai, F.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Newman, K.; King, M.L. , Repression of zygotic gene expression in the Xenopus germline. Development 2010, 137, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.L.; DeFalco, T. , Of Mice and Men: In Vivo and In Vitro Studies of Primordial Germ Cell Specification. Semin Reprod Med 2017, 35, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Surani, M.A. , On the origin of the human germline. Development 2018, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, I.; Nakagawa, Y.; Ohtsu, Y.; Hamano, K.; Medina, J.; Nagasawa, M. , Return of the glucoreceptor: Glucose activates the glucose-sensing receptor T1R3 and facilitates metabolism in pancreatic beta-cells. J Diabetes Investig 2015, 6, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusdottir, E.; Surani, M.A. , How to make a primordial germ cell. Development 2014, 141, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sybirna, A.; Tang, W.W.C.; Pierson Smela, M.; Dietmann, S.; Gruhn, W.H.; Brosh, R.; Surani, M.A. , A critical role of PRDM14 in human primordial germ cell fate revealed by inducible degrons. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Zhang, H.; Tang, W.W.C.; Irie, N.; Withey, S.; Klisch, D.; Sybirna, A.; Dietmann, S.; Contreras, D.A.; Webb, R.; Allegrucci, C.; Alberio, R.; Surani, M.A. Principles of early human development and germ cell program from conserved model systems. Nature 2017, 546, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Chuma, S.; Nakatsuji, N.; Suemori, H. , In vitro germ cell differentiation from cynomolgus monkey embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.L.; Pelegri, F. , Primordial Germ Cell Specification in Vertebrate Embryos: Phylogenetic Distribution and Conserved Molecular Features of Preformation and Induction. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 730332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strome, S.; Updike, D. , Specifying and protecting germ cell fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstberger, S.; Hafner, M.; Tuschl, T. , A census of human RNA-binding proteins. Nat Rev Genet 2014, 15, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ephrussi, A.; Dickinson, L.K.; Lehmann, R. , Oskar organizes the germ plasm and directs localization of the posterior determinant nanos. Cell 1991, 66, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Lehmann, R. , Nanos is the localized posterior determinant in Drosophila. Cell 1991, 66, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extavour, C.G.; Pang, K.; Matus, D.Q.; Martindale, M.Q. , vasa and nanos expression patterns in a sea anemone and the evolution of bilaterian germ cell specification mechanisms. Evol Dev 2005, 7, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, K.; Seydoux, G. , nos-1 and nos-2, two genes related to Drosophila nanos, regulate primordial germ cell development and survival in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 1999, 126, 4861–4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zayas, R.M.; Guo, T.; Newmark, P.A. , nanos function is essential for development and regeneration of planarian germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 5901–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, C.E.; Yajima, M.; Wessel, G.M. , Nanos functions to maintain the fate of the small micromere lineage in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol 2010, 337, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Singh, A.; King, M.L. , Xenopus Nanos1 is required to prevent endoderm gene expression and apoptosis in primordial germ cells. Development 2012, 139, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprunner, M.; Thisse, C.; Thisse, B.; Raz, E. , A zebrafish nanos-related gene is essential for the development of primordial germ cells. Genes Dev 2001, 15, 2877–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saga, Y. , Mouse germ cell development during embryogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2008, 18, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saga, Y. , Sexual development of mouse germ cells: Nanos2 promotes the male germ cell fate by suppressing the female pathway. Dev Growth Differ 2008, 50 Suppl 1, S141–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaruzelska, J.; Kotecki, M.; Kusz, K.; Spik, A.; Firpo, M.; Reijo Pera, R.A. , Conservation of a Pumilio-Nanos complex from Drosophila germ plasm to human germ cells. Dev Genes Evol 2003, 213, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Keuckelaere, E.; Hulpiau, P.; Saeys, Y.; Berx, G.; van Roy, F. , Nanos genes and their role in development and beyond. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018, 75, 1929–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, D.; Raisch, T.; Weichenrieder, O.; Jonas, S.; Izaurralde, E. , Structural basis for the Nanos-mediated recruitment of the CCR4-NOT complex and translational repression. Genes Dev 2014, 28, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Saba, R.; Miyoshi, K.; Morita, Y.; Saga, Y. , Interaction between NANOS2 and the CCR4-NOT deadenylation complex is essential for male germ cell development in mouse. PLoS One 2012, 7, e33558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.K.; Moore-Jarrett, T.; Ruley, H.E. , PUM2, a novel murine puf protein, and its consensus RNA-binding site. RNA 2001, 7, 1855–1866. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; McLachlan, J.; Zamore, P.D.; Hall, T.M. , Modular recognition of RNA by a human pumilio-homology domain. Cell 2002, 110, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilaslan, E.; Kwiatkowska, K.; Smialek, M.J.; Sajek, M.P.; Lemanska, Z.; Alla, M.; Janecki, D.M.; Jaruzelska, J.; Kusz-Zamelczyk, K. , Distinct Roles of NANOS1 and NANOS3 in the Cell Cycle and NANOS3-PUM1-FOXM1 Axis to Control G2/M Phase in a Human Primordial Germ Cell Model. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; King, M.L. , Repressive translational control in germ cells. Mol Reprod Dev 2013, 80, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Kobayashi, S. , Nanos suppresses somatic cell fate in Drosophila germ line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 10338–10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, R.L.; Draper, B.W. , nanos3 maintains germline stem cells and expression of the conserved germline stem cell gene nanos2 in the zebrafish ovary. Dev Biol 2013, 374, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuda, M.; Sasaoka, Y.; Kiso, M.; Abe, K.; Haraguchi, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Saga, Y. , Conserved role of nanos proteins in germ cell development. Science 2003, 301, 1239–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusz-Zamelczyk, K.; Sajek, M.; Spik, A.; Glazar, R.; Jedrzejczak, P.; Latos-Bielenska, A.; Kotecki, M.; Pawelczyk, L.; Jaruzelska, J. , Mutations of NANOS1, a human homologue of the Drosophila morphogen, are associated with a lack of germ cells in testes or severe oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia. J Med Genet 2013, 50, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, B.; Dong, Z.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Z.; Shi, G.; Cao, Y.; Xu, Y. , A NANOS3 mutation linked to protein degradation causes premature ovarian insufficiency. Cell Death Dis 2013, 4, e825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilaslan, E.; Sajek, M.P.; Jaruzelska, J.; Kusz-Zamelczyk, K. , Emerging Roles of NANOS RNA-Binding Proteins in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P.L.; Soderstrom, K.O. , Occurrence of nuage in fetal human germ cells. Cell Tissue Res 1978, 194, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, E.M. , Germ plasm and the differentiation of the germ cell line. Int Rev Cytol 1975, 43, 229–280. [Google Scholar]

- Voronina, E.; Seydoux, G.; Sassone-Corsi, P.; Nagamori, I. , RNA granules in germ cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.P.T.; Seydoux, G. , Nuage condensates: accelerators or circuit breakers for sRNA silencing pathways? RNA 2022, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amigo, I.; Traba, J.; Satrustegui, J.; del Arco, A. , SCaMC-1Like a member of the mitochondrial carrier (MC) family preferentially expressed in testis and localized in mitochondria and chromatoid body. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, D.; Houston, D.W. , RNA Localization in the Vertebrate Oocyte: Establishment of Oocyte Polarity and Localized mRNA Assemblages. Results Probl Cell Differ 2017, 63, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pepling, M.E.; Wilhelm, J.E.; O'Hara, A.L.; Gephardt, G.W.; Spradling, A.C. , Mouse oocytes within germ cell cysts and primordial follicles contain a Balbiani body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, R.A.; Selman, K. , Ultrastructural aspects of oogenesis and oocyte growth in fish and amphibians. J Electron Microsc Tech 1990, 16, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrest, K.M.; Gavis, E.R. , Live imaging of endogenous RNA reveals a diffusion and entrapment mechanism for nanos mRNA localization in Drosophila. Curr Biol 2003, 13, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, H. , Nanos maintains germline stem cell self-renewal by preventing differentiation. Science 2004, 303, 2016–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavis, E.R.; Lehmann, R. , Translational regulation of nanos by RNA localization. Nature 1994, 369, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ephrussi, A.; Lehmann, R. , Induction of germ cell formation by oskar. Nature 1992, 358, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekovic, F.; Rammelt, C.; Kubikova, J.; Metz, J.; Jeske, M.; Wahle, E. , RNA binding proteins Smaug and Cup induce CCR4-NOT-dependent deadenylation of the nanos mRNA in a reconstituted system. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 3950–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavis, E.R.; Lunsford, L.; Bergsten, S.E.; Lehmann, R. , A conserved 90 nucleotide element mediates translational repression of nanos RNA. Development 1996, 122, 2791–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramat, A.; Garcia-Silva, M.R.; Jahan, C.; Nait-Saidi, R.; Dufourt, J.; Garret, C.; Chartier, A.; Cremaschi, J.; Patel, V.; Decourcelle, M.; Bastide, A.; Juge, F.; Simonelig, M. , The PIWI protein Aubergine recruits eIF3 to activate translation in the germ plasm. Cell Res 2020, 30, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, O.; Lasko, P. , Translational regulation and RNA localization in Drosophila oocytes and embryos. Annu Rev Genet 2001, 35, 365–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Dickinson, L.K.; Lehmann, R. , Genetics of nanos localization in Drosophila. Dev Dyn 1994, 199, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavis, E.R.; Curtis, D.; Lehmann, R. , Identification of cis-acting sequences that control nanos RNA localization. Dev Biol 1996, 176, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curnutte, H.A.; Lan, X.; Sargen, M.; Ao Ieong, S.M.; Campbell, D.; Kim, H.; Liao, Y.; Lazar, S.B.; Trcek, T. , Proteins rather than mRNAs regulate nucleation and persistence of Oskar germ granules in Drosophila. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 112723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappetta, A.; Liao, J.; Tian, S.; Trcek, T. , Structural and functional organization of germ plasm condensates. Biochem J 2022, 479, 2477–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.C.; Sinsimer, K.S.; Lee, J.J.; Wieschaus, E.F.; Gavis, E.R. , Independent and coordinate trafficking of single Drosophila germ plasm mRNAs. Nat Cell Biol 2015, 17, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.M.; Updike, D.L. , Germ granules and gene regulation in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Genetics 2022, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, J.N.; Schisa, J.A.; Priess, J.R. , P granules in the germ cells of Caenorhabditis elegans adults are associated with clusters of nuclear pores and contain RNA. Dev Biol 2000, 219, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, E.M.; Ito, S. , Fine structural and radioautographic observations on dense perinuclear cytoplasmic material in tadpole oocytes. J Cell Biol 1971, 49, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, B.; Ackerman, L.; Barbel, S.; Jan, L.Y.; Jan, Y.N. , Identification of a component of Drosophila polar granules. Development 1988, 103, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Updike, D.; Strome, S. , P granule assembly and function in Caenorhabditis elegans germ cells. J Androl 2010, 31, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, U.; Pitt, J.; Dennis, S.; Priess, J.R. , Perinuclear P granules are the principal sites of mRNA export in adult C. elegans germ cells. Development 2010, 137, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, S.; Rana, M.; Subramaniam, K. , Multiple maternal proteins coordinate to restrict the translation of C. elegans nanos-2 to primordial germ cells. Development 2008, 135, 1803–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voronina, E.; Seydoux, G. , The C. elegans homolog of nucleoporin Nup98 is required for the integrity and function of germline P granules. Development 2010, 137, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelson, M.; Hetzer, M.W. , The role of nuclear pores in gene regulation, development and disease. EMBO Rep 2009, 10, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brangwynne, C.P.; Eckmann, C.R.; Courson, D.S.; Rybarska, A.; Hoege, C.; Gharakhani, J.; Julicher, F.; Hyman, A.A. , Germline P granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation. Science 2009, 324, 1729–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, B.; Crittenden, S.; Gallegos, M.; Moulder, G.; Barstead, R.; Kimble, J.; Wickens, M. , NANOS-3 and FBF proteins physically interact to control the sperm-oocyte switch in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol 1999, 9, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijjar, S.; Woodland, H.R. , Protein interactions in Xenopus germ plasm RNP particles. PLoS One 2013, 8, e80077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, L.; Forristall, C.; Zhou, Y.; King, M.L. , A mRNA localized to the vegetal cortex of Xenopus oocytes encodes a protein with a nanos-like zinc finger domain. Development 1993, 117, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roovers, E.F.; Kaaij, L.J.T.; Redl, S.; Bronkhorst, A.W.; Wiebrands, K.; de Jesus Domingues, A.M.; Huang, H.Y.; Han, C.T.; Riemer, S.; Dosch, R.; Salvenmoser, W.; Grun, D.; Butter, F.; van Oudenaarden, A.; Ketting, R.F. , Tdrd6a Regulates the Aggregation of Buc into Functional Subcellular Compartments that Drive Germ Cell Specification. Dev Cell 2018, 46, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, B.; Deshler, J.O. , RNA localization to the Balbiani body in Xenopus oocytes is regulated by the energy state of the cell and is facilitated by kinesin II. RNA 2009, 15, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.; Torres, J.; Lewis, R.A.; Mowry, K.L.; Houliston, E.; King, M.L. , Localization of RNAs to the mitochondrial cloud in Xenopus oocytes through entrapment and association with endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell 2004, 15, 4669–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloc, M.; Bilinski, S.; Pui-Yee Chan, A.; Etkin, L.D. , The targeting of Xcat2 mRNA to the germinal granules depends on a cis-acting germinal granule localization element within the 3'UTR. Dev Biol 2000, 217, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; King, M.L. , RNA transport to the vegetal cortex of Xenopus oocytes. Dev Biol 1996, 179, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.L.; Messitt, T.J.; Mowry, K.L. , Putting RNAs in the right place at the right time: RNA localization in the frog oocyte. Biol Cell 2005, 97, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forristall, C.; Pondel, M.; Chen, L.; King, M.L. , Patterns of localization and cytoskeletal association of two vegetally localized RNAs, Vg1 and Xcat-2. Development 1995, 121, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguero, T.; Zhou, Y.; Kloc, M.; Chang, P.; Houliston, E.; King, M.L. , Hermes (Rbpms) is a Critical Component of RNP Complexes that Sequester Germline RNAs during Oogenesis. J Dev Biol 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.W.; Cauffman, K.; Chan, A.P.; Zhou, Y.; King, M.L.; Etkin, L.D.; Kloc, M. , Hermes RNA-binding protein targets RNAs-encoding proteins involved in meiotic maturation, early cleavage, and germline development. Differentiation 2007, 75, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.J.; Moore, W.; Hames, R.; Houliston, E.; Chang, P.; King, M.L.; Woodland, H.R. , Xenopus Xpat protein is a major component of germ plasm and may function in its organisation and positioning. Dev Biol 2005, 287, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahanukar, A.; Wharton, R.P. , The Nanos gradient in Drosophila embryos is generated by translational regulation. Genes Dev 1996, 10, 2610–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Nerlick, S.; An, W.; King, M.L. , Xenopus germline nanos1 is translationally repressed by a novel structure-based mechanism. Development 2011, 138, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur, H.; Bubunenko, M.; Houston, D.W.; King, M.L. , Xcat2 RNA is a translationally sequestered germ plasm component in Xenopus. Mech Dev 1999, 84, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Igarashi, K.; Aisaki, K.; Kanno, J.; Saga, Y. , NANOS2 interacts with the CCR4-NOT deadenylation complex and leads to suppression of specific RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 3594–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvay, K.; Claussen, M.; Katzer, M.; Landgrebe, J.; Pieler, T. , Xenopus Dead end mRNA is a localized maternal determinant that serves a conserved function in germ cell development. Dev Biol 2006, 291, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidinger, G.; Stebler, J.; Slanchev, K.; Dumstrei, K.; Wise, C.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Thisse, C.; Thisse, B.; Raz, E. , dead end, a novel vertebrate germ plasm component, is required for zebrafish primordial germ cell migration and survival. Curr Biol 2003, 13, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguero, T.; Jin, Z.; Chorghade, S.; Kalsotra, A.; King, M.L.; Yang, J. , Maternal Dead-end 1 promotes translation of nanos1 by binding the eIF3 complex. Development 2017, 144, 3755–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Xu, S.; Ma, D.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Xiao, Y.; Chi, L.; Liu, Q.; Li, J. , Germ line specific expression of a vasa homologue gene in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus): evidence for vasa localization at cleavage furrows in euteleostei. Mol Reprod Dev 2012, 79, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, K.; Fernandes, J.M.; Yoshizaki, G.; Miwa, M.; Babiak, I. , Identification and migration of primordial germ cells in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar: characterization of vasa, dead end, and lymphocyte antigen 75 genes. Mol Reprod Dev 2013, 80, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presslauer, C.; Nagasawa, K.; Fernandes, J.M.; Babiak, I. , Expression of vasa and nanos3 during primordial germ cell formation and migration in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.). Theriogenology 2012, 78, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, K.; Kawakami, K.; Sakamoto, H.; Inoue, K. , Spatiotemporal localization of germ plasm RNAs during zebrafish oogenesis. Mech Dev 2007, 124, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, B.W.; McCallum, C.M.; Moens, C.B. , nanos1 is required to maintain oocyte production in adult zebrafish. Dev Biol 2007, 305, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Otani, S.; Fujimoto, T.; Suzuki, T.; Nakatsuji, T.; Arai, K.; Yamaha, E. , The germ line lineage in ukigori, Gymnogobius species (Teleostei: Gobiidae) during embryonic development. Int J Dev Biol 2004, 48, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herpin, A.; Rohr, S.; Riedel, D.; Kluever, N.; Raz, E.; Schartl, M. , Specification of primordial germ cells in medaka (Oryzias latipes). BMC Dev Biol 2007, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skugor, A.; Tveiten, H.; Johnsen, H.; Andersen, O. , Multiplicity of Buc copies in Atlantic salmon contrasts with loss of the germ cell determinant in primates, rodents and axolotl. BMC Evol Biol 2016, 16, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eno, C.; Gomez, T.; Slusarski, D.C.; Pelegri, F. , Slow calcium waves mediate furrow microtubule reorganization and germ plasm compaction in the early zebrafish embryo. Development 2018, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Rodriguez, J.R.; Salas-Vidal, E.; Lomeli, H.; Zurita, M.; Schnabel, D. , RhoA/ROCK pathway activity is essential for the correct localization of the germ plasm mRNAs in zebrafish embryos. Dev Biol 2017, 421, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegri, F.; Knaut, H.; Maischein, H.M.; Schulte-Merker, S.; Nusslein-Volhard, C. , A mutation in the zebrafish maternal-effect gene nebel affects furrow formation and vasa RNA localization. Curr Biol 1999, 9, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, C.E.; Pelegri, F. , The role of the cytoskeleton in germ plasm aggregation and compaction in the zebrafish embryo. Curr Top Dev Biol 2020, 140, 145–179. [Google Scholar]

- Braat, A.K.; Speksnijder, J.E.; Zivkovic, D. , Germ line development in fishes. Int J Dev Biol 1999, 43, 745–760. [Google Scholar]

- Knaut, H.; Pelegri, F.; Bohmann, K.; Schwarz, H.; Nusslein-Volhard, C. , Zebrafish vasa RNA but not its protein is a component of the germ plasm and segregates asymmetrically before germline specification. J Cell Biol 2000, 149, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashirullah, A.; Halsell, S.R.; Cooperstock, R.L.; Kloc, M.; Karaiskakis, A.; Fisher, W.W.; Fu, W.; Hamilton, J.K.; Etkin, L.D.; Lipshitz, H.D. , Joint action of two RNA degradation pathways controls the timing of maternal transcript elimination at the midblastula transition in Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J 1999, 18, 2610–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishima, Y.; Giraldez, A.J.; Takeda, Y.; Fujiwara, T.; Sakamoto, H.; Schier, A.F.; Inoue, K. , Differential regulation of germline mRNAs in soma and germ cells by zebrafish miR-430. Curr Biol 2006, 16, 2135–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Tani-Matsuhana, S.; Ohkawa, Y.; Sakamoto, H.; Inoue, K. , DND protein functions as a translation repressor during zebrafish embryogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 484, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedde, M.; Strasser, M.J.; Boldajipour, B.; Oude Vrielink, J.A.; Slanchev, K.; le Sage, C.; Nagel, R.; Voorhoeve, P.M.; van Duijse, J.; Orom, U.A.; Lund, A.H.; Perrakis, A.; Raz, E.; Agami, R. , RNA-binding protein Dnd1 inhibits microRNA access to target mRNA. Cell 2007, 131, 1273–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betley, J.N.; Frith, M.C.; Graber, J.H.; Choo, S.; Deshler, J.O. , A ubiquitous and conserved signal for RNA localization in chordates. Curr Biol 2002, 12, 1756–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontems, F.; Stein, A.; Marlow, F.; Lyautey, J.; Gupta, T.; Mullins, M.C.; Dosch, R. , Bucky ball organizes germ plasm assembly in zebrafish. Curr Biol 2009, 19, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, P.; Riemer, S.; Perera, R.; Lingner, T.; Goloborodko, A.; Khalifa, H.; Bontems, F.; Kaufholz, F.; El-Brolosy, M.A.; Dosch, R. , Functional equivalence of germ plasm organizers. PLoS Genet 2018, 14, e1007696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Miao, R.; Xiao, R.; Mei, J. , m(6)A reader Igf2bp3 enables germ plasm assembly by m(6)A-dependent regulation of gene expression in zebrafish. Sci Bull (Beijing) 2021, 66, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.; Kawakami, K.; Hopkins, N. , Zebrafish vasa homologue RNA is localized to the cleavage planes of 2- and 4-cell-stage embryos and is expressed in the primordial germ cells. Development 1997, 124, 3157–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, C.; Ho, R.K. , mRNA localization patterns in zebrafish oocytes. Mech Dev 2000, 92, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Maegawa, S.; Nagai, T.; Yamaha, E.; Suzuki, H.; Yasuda, K.; Inoue, K. , Localized maternal factors are required for zebrafish germ cell formation. Dev Biol 2004, 268, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theusch, E.V.; Brown, K.J.; Pelegri, F. , Separate pathways of RNA recruitment lead to the compartmentalization of the zebrafish germ plasm. Dev Biol 2006, 292, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eno, C.; Hansen, C.L.; Pelegri, F. , Aggregation, segregation, and dispersal of homotypic germ plasm RNPs in the early zebrafish embryo. Dev Dyn 2019, 248, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trcek, T.; Grosch, M.; York, A.; Shroff, H.; Lionnet, T.; Lehmann, R. , Drosophila germ granules are structured and contain homotypic mRNA clusters. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niepielko, M.G.; Eagle, W.V.I.; Gavis, E.R. , Stochastic Seeding Coupled with mRNA Self-Recruitment Generates Heterogeneous Drosophila Germ Granules. Curr Biol 2018, 28, 1872–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Vale, R.D. , RNA phase transitions in repeat expansion disorders. Nature 2017, 546, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Treeck, B.; Protter, D.S.W.; Matheny, T.; Khong, A.; Link, C.D.; Parker, R. , RNA self-assembly contributes to stress granule formation and defining the stress granule transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 2734–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, S.; Bontems, F.; Krishnakumar, P.; Gomann, J.; Dosch, R. , A functional Bucky ball-GFP transgene visualizes germ plasm in living zebrafish. Gene Expr Patterns 2015, 18, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boke, E.; Ruer, M.; Wuhr, M.; Coughlin, M.; Lemaitre, R.; Gygi, S.P.; Alberti, S.; Drechsel, D.; Hyman, A.A.; Mitchison, T.J. , Amyloid-like Self-Assembly of a Cellular Compartment. Cell 2016, 166, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross-Thebing, T.; Yigit, S.; Pfeiffer, J.; Reichman-Fried, M.; Bandemer, J.; Ruckert, C.; Rathmer, C.; Goudarzi, M.; Stehling, M.; Tarbashevich, K.; Seggewiss, J.; Raz, E. , The Vertebrate Protein Dead End Maintains Primordial Germ Cell Fate by Inhibiting Somatic Differentiation. Dev Cell 2017, 43, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilboa, L.; Lehmann, R. , Repression of primordial germ cell differentiation parallels germ line stem cell maintenance. Curr Biol 2004, 14, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerich, K.J.; Tarbashevich, K.; Schick, J.; Gupta, A.; Zhu, M.; Hull, K.; Romo, D.; Zeuschner, D.; Goudarzi, M.; Gross-Thebing, T.; Raz, E. , Spatial organization and function of RNA molecules within phase-separated condensates in zebrafish are controlled by Dnd1. Dev Cell 2023, 58, 1578–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amikura, R.; Kashikawa, M.; Nakamura, A.; Kobayashi, S. , Presence of mitochondria-type ribosomes outside mitochondria in germ plasm of Drosophila embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 9133–9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.S.; Putnam, A.; Lu, T.; He, S.; Ouyang, J.P.T.; Seydoux, G. , Recruitment of mRNAs to P granules by condensation with intrinsically-disordered proteins. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.M.; Winkenbach, L.P.; Boyson, S.; Saxton, M.N.; Daidone, C.; Al-Mazaydeh, Z.A.; Nishimura, M.T.; Mueller, F.; Osborne Nishimura, E. , mRNA localization is linked to translation regulation in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ lineage. Development 2020, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, E.M. , Fine structural observations on the form and distribution of nuage in germ cells of the rat. Anat Rec 1974, 178, 731–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morroni, M.; Cangiotti, A.M.; Marzioni, D.; D'Angelo, A.; Gesuita, R.; De Nictolis, M. , Intermitochondrial cement (nuage) in a spermatocytic seminoma: comparison with classical seminoma and normal testis. Virchows Arch 2008, 453, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Venzor, A.; Penfold, C.A.; Morgan, M.D.; Tang, W.W.; Kobayashi, T.; Wong, F.C.; Bergmann, S.; Slatery, E.; Boroviak, T.E.; Marioni, J.C.; Surani, M.A. , Origin and segregation of the human germline. Life Sci Alliance 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, R.; Nistal, M.; Amat, P.; Rodriguez, M.C. , Presence of ribonucleoproteins and basic proteins in the nuage and intermitochondrial bars of human spermatogonia. J Anat 1985, 143, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi, S.; Tsuda, M.; Kitajima, S.; Sasaoka, Y.; Nomura-Kitabayashid, A.; Kurokawa, K.; Saga, Y. , nanos1: a mouse nanos gene expressed in the central nervous system is dispensable for normal development. Mech Dev 2003, 120, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, B.L.; Nishi, M.Y.; Santos, M.G.; Brito, V.N.; Domenice, S.; Mendonca, B.B. , Mutation analysis of NANOS3 in Brazilian women with primary ovarian failure. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2016, 71, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkouby, Y.M.; Mullins, M.C. , Coordination of cellular differentiation, polarity, mitosis and meiosis - New findings from early vertebrate oogenesis. Dev Biol 2017, 430, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meikar, O.; Vagin, V.V.; Chalmel, F.; Sostar, K.; Lardenois, A.; Hammell, M.; Jin, Y.; Da Ros, M.; Wasik, K.A.; Toppari, J.; Hannon, G.J.; Kotaja, N. , An atlas of chromatoid body components. RNA 2014, 20, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.S.; Toyooka, Y.; Akasu, R.; Katoh-Fukui, Y.; Nakahara, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Yokoyama, M.; Noce, T. , The mouse homolog of Drosophila Vasa is required for the development of male germ cells. Genes Dev 2000, 14, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotaja, N.; Sassone-Corsi, P. , The chromatoid body: a germ-cell-specific RNA-processing centre. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007, 8, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassani, M.; Seydoux, G. , P-body-like condensates in the germline. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2024, 157, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginter-Matuszewska, B.; Kusz, K.; Spik, A.; Grzeszkowiak, D.; Rembiszewska, A.; Kupryjanczyk, J.; Jaruzelska, J. , NANOS1 and PUMILIO2 bind microRNA biogenesis factor GEMIN3, within chromatoid body in human germ cells. Histochem Cell Biol 2011, 136, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janecki, D.M.; Ilaslan, E.; Smialek, M.J.; Sajek, M.P.; Kotecki, M.; Ginter-Matuszewska, B.; Krainski, P.; Jaruzelska, J.; Kusz-Zamelczyk, K. , Human NANOS1 Represses Apoptosis by Downregulating Pro-Apoptotic Genes in the Male Germ Cell Line. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubstenberger, A.; Noble, S.L.; Cameron, C.; Evans, T.C. , Translation repressors, an RNA helicase, and developmental cues control RNP phase transitions during early development. Dev Cell 2013, 27, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, T.; Ninomiya, K.; Nakagawa, S.; Yamazaki, T. , A guide to membraneless organelles and their various roles in gene regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023, 24, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, R.; Kiso, M.; Saga, Y. , ES-mediated chimera analysis revealed requirement of DDX6 for NANOS2 localization and function in mouse germ cells. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Niimi, Y.; Shinmyozu, K.; Zhou, Z.; Kiso, M.; Saga, Y. , Dead end1 is an essential partner of NANOS2 for selective binding of target RNAs in male germ cell development. EMBO Rep 2016, 17, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T.; Wright, D.; Suzuki, A.; Saga, Y. , A cooperative mechanism of target RNA selection via germ-cell-specific RNA-binding proteins NANOS2 and DND1. Cell Rep 2022, 39, 110894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaji, M.; Tanaka, T.; Shigeta, M.; Chuma, S.; Saga, Y.; Saitou, M. , Functional reconstruction of NANOS3 expression in the germ cell lineage by a novel transgenic reporter reveals distinct subcellular localizations of NANOS3. Reproduction 2010, 139, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Niimi, Y.; Saga, Y. , Interaction of NANOS2 and NANOS3 with different components of the CNOT complex may contribute to the functional differences in mouse male germ cells. Biol Open 2014, 3, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Tang, F.; Yu, M.; Zhu, H.; Chu, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, W.; Hua, J.; Peng, S. , Expression profile of Nanos2 gene in dairy goat and its inhibitory effect on Stra8 during meiosis. Cell Prolif 2014, 47, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.; Kedersha, N. , RNA granules. J Cell Biol 2006, 172, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.; Kedersha, N. , Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends Biochem Sci 2008, 33, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bish, R.; Cuevas-Polo, N.; Cheng, Z.; Hambardzumyan, D.; Munschauer, M.; Landthaler, M.; Vogel, C. , Comprehensive Protein Interactome Analysis of a Key RNA Helicase: Detection of Novel Stress Granule Proteins. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1441–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.R.; Miller, I.J.; Anderson, P.; Streuli, M. , RNA-binding protein TIAR is essential for primordial germ cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 2331–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Shirakawa, T.; Ohbo, K.; Sada, A.; Wu, Q.; Hasegawa, K.; Saba, R.; Saga, Y. , RNA Binding Protein Nanos2 Organizes Post-transcriptional Buffering System to Retain Primitive State of Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cells. Dev Cell 2015, 34, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Brangwynne, C.P. , Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 2017, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. , Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struhl, K. , Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs): A vague and confusing concept for protein function. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 1186–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemke, E.A.; Babu, M.M.; Kriwacki, R.W.; Mittag, T.; Pappu, R.V.; Wright, P.E.; Forman-Kay, J.D. , Intrinsic disorder: A term to define the specific physicochemical characteristic of protein conformational heterogeneity. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, S.F.; Rice, A.M.; Peeples, W.B.; Lin, Y.; Jain, S.; Parker, R.; Rosen, M.K. , Compositional Control of Phase-Separated Cellular Bodies. Cell 2016, 166, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, C.; Cheng, S.; Schuh, M. , Phase Separation during Germline Development. Trends Cell Biol 2021, 31, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, D.W.; King, M.L. , Germ plasm and molecular determinants of germ cell fate. Curr Top Dev Biol 2000, 50, 155–181. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Stainier, W.; Dufourt, J.; Lagha, M.; Lehmann, R. , Direct observation of translational activation by a ribonucleoprotein granule. Nat Cell Biol 2024, 26, 1322–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, R. , Germ Plasm Biogenesis--An Oskar-Centric Perspective. Curr Top Dev Biol 2016, 116, 679–707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Doenier, J.; Lynch, T.R.; Kimble, J.; Aoki, S.T. , An improved in vivo tethering assay with single molecule FISH reveals that a nematode Nanos enhances reporter expression and mRNA stability. RNA 2021, 27, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Ma, W.; Yang, B.; Lu, H.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, L. , Post-translational modifications in liquid-liquid phase separation: a comprehensive review. Mol Biomed 2022, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cech, T.R. , RNA in biological condensates. RNA 2022, 28, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.S.; Wang, X.; Beadell, A.V.; Lu, Z.; Shi, H.; Kuuspalu, A.; Ho, R.K.; He, C. , m(6)A-dependent maternal mRNA clearance facilitates zebrafish maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nature 2017, 542, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; Hu, Y.C.; Huttelmaier, S.; Skibbe, J.R.; Su, R.; Deng, X.; Dong, L.; Sun, M.; Li, C.; Nachtergaele, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Ferchen, K.; Greis, K.D.; Jiang, X.; Wei, M.; Qu, L.; Guan, J.L.; He, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, J. , Author Correction: Recognition of RNA N(6)-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; Hu, Y.C.; Huttelmaier, S.; Skibbe, J.R.; Su, R.; Deng, X.; Dong, L.; Sun, M.; Li, C.; Nachtergaele, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Ferchen, K.; Greis, K.D.; Jiang, X.; Wei, M.; Qu, L.; Guan, J.L.; He, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, J. , Recognition of RNA N(6)-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).