Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

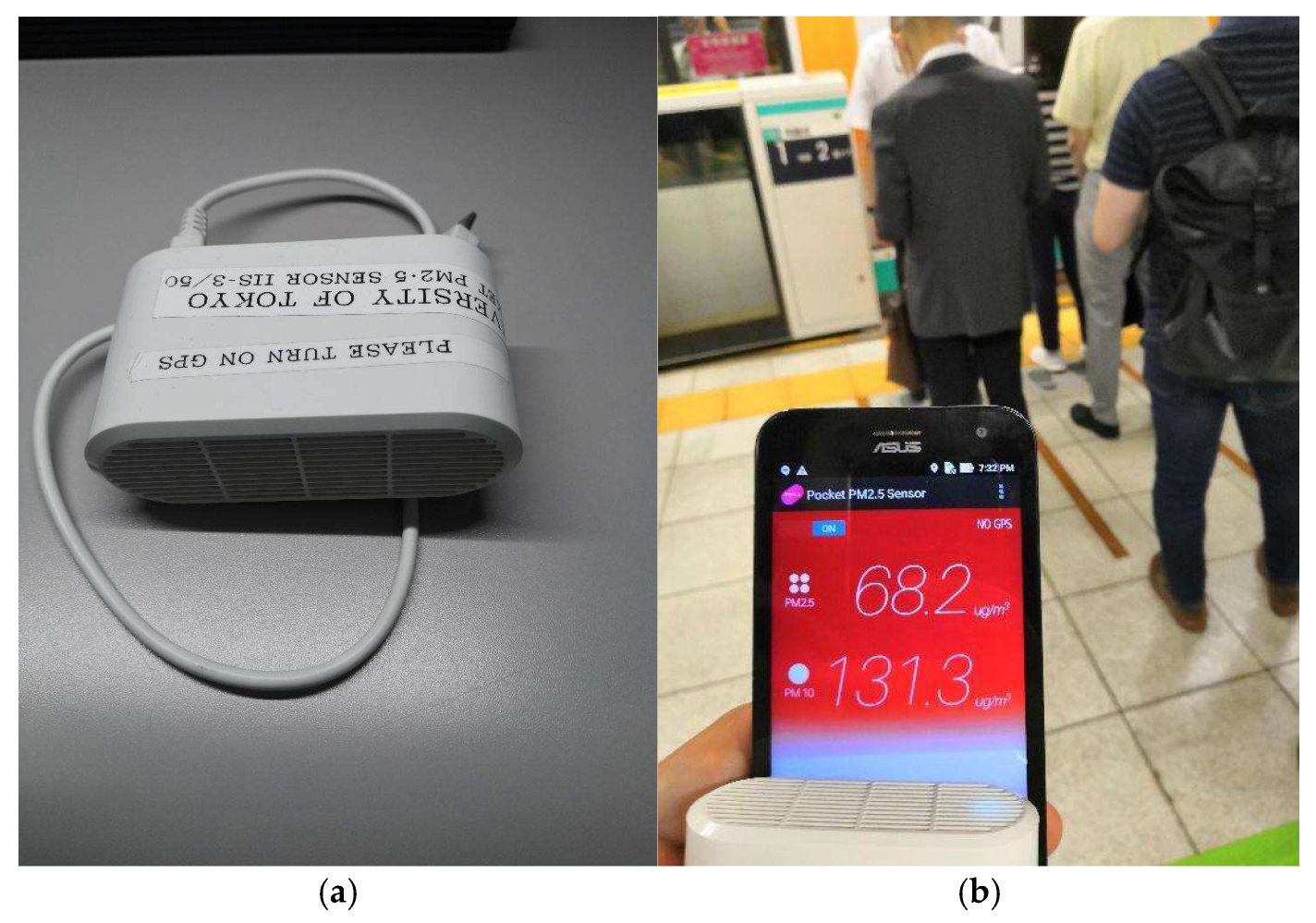

2.1. Measurement Device

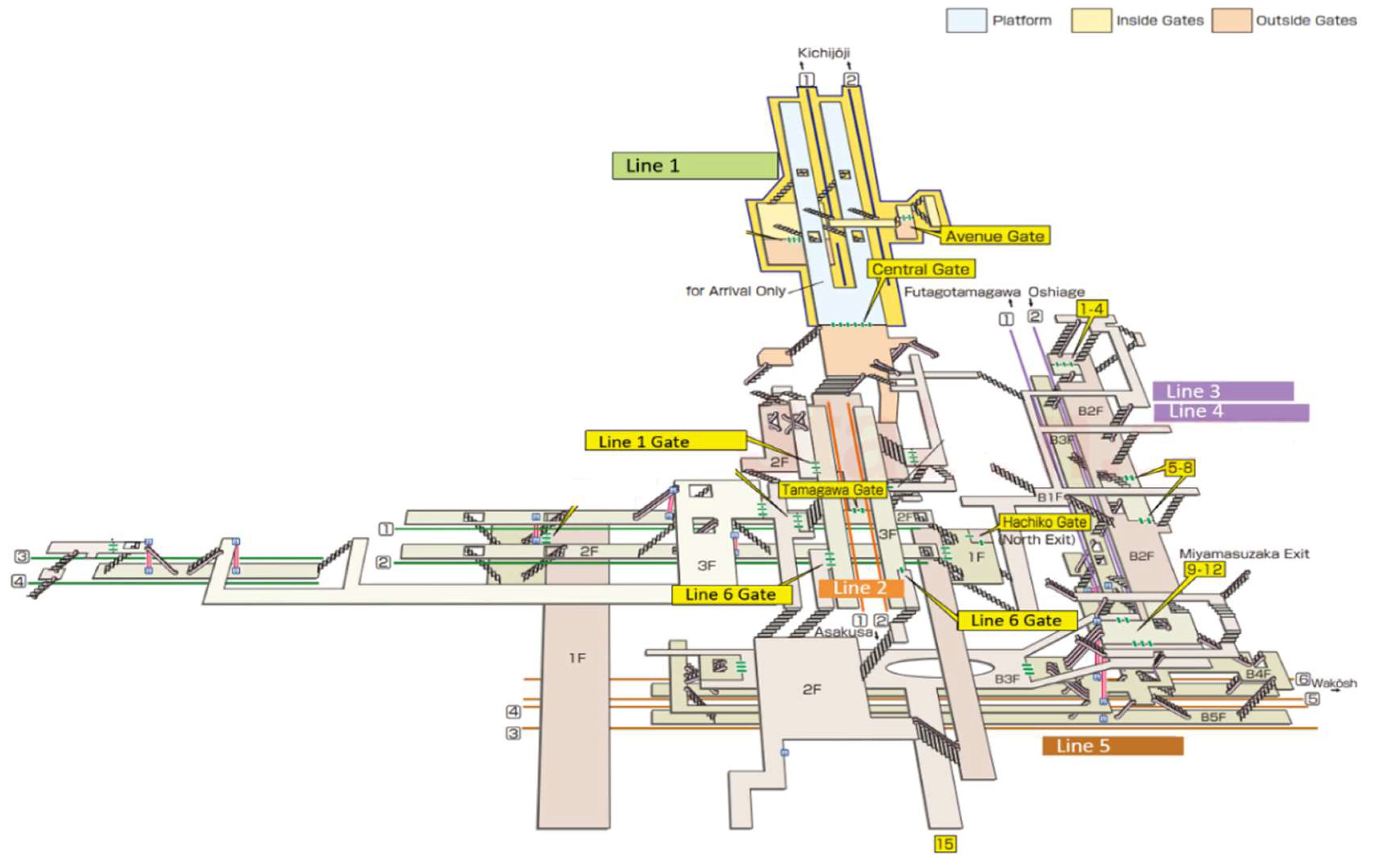

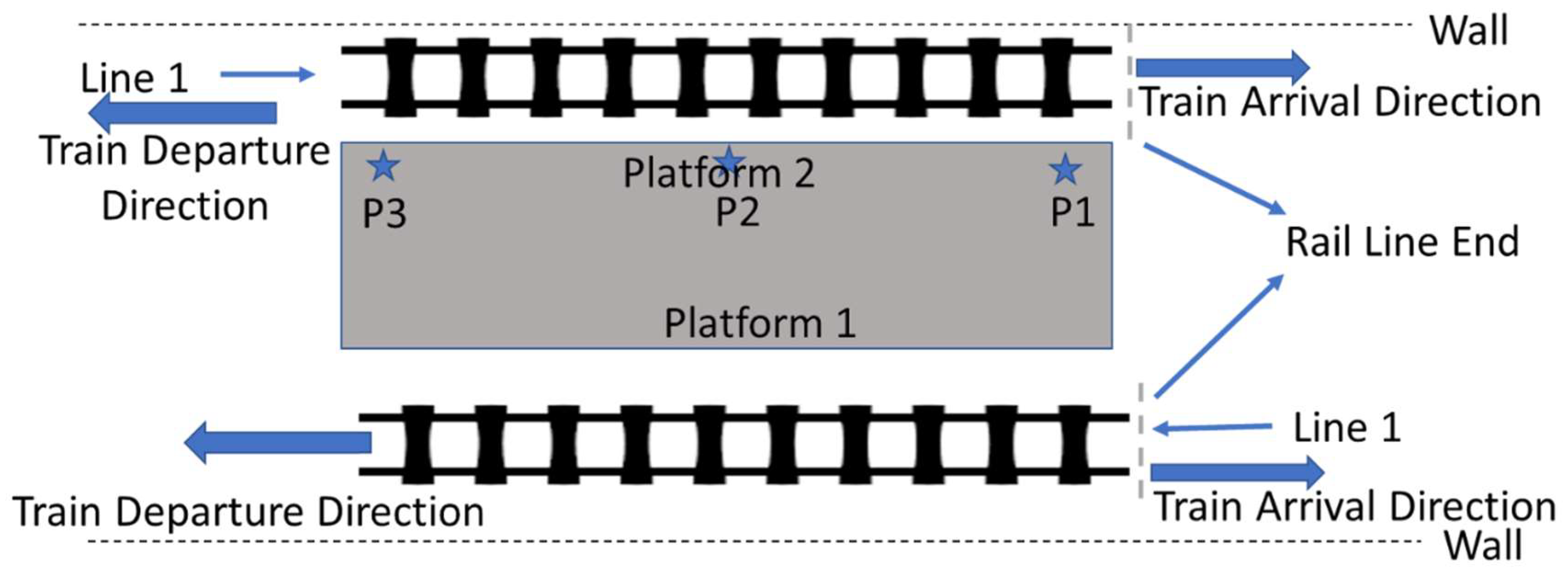

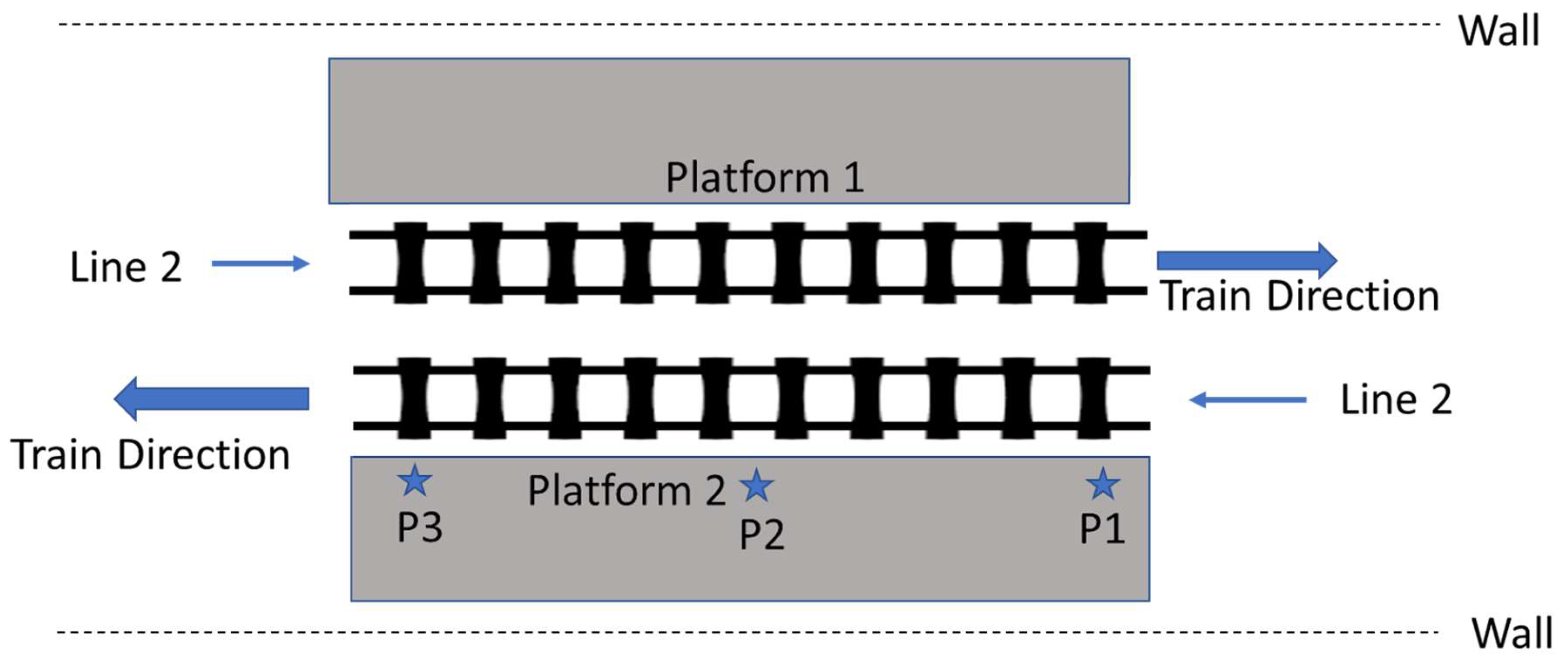

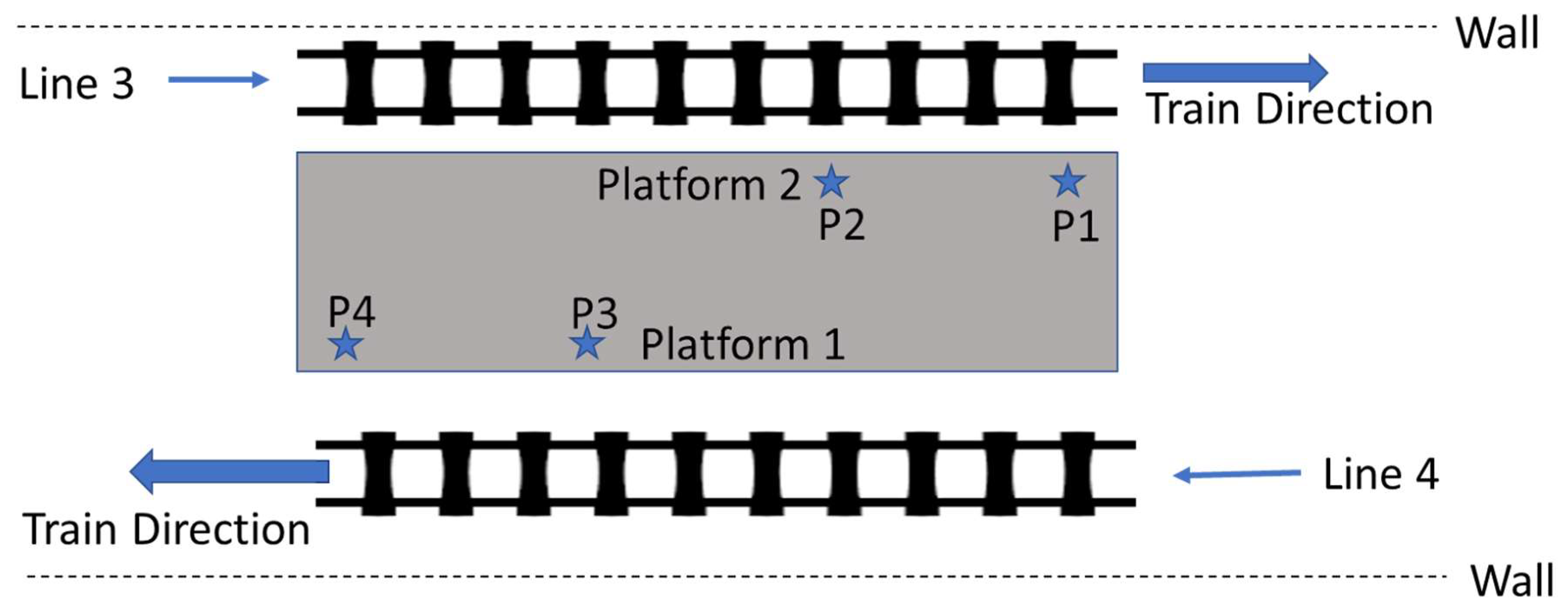

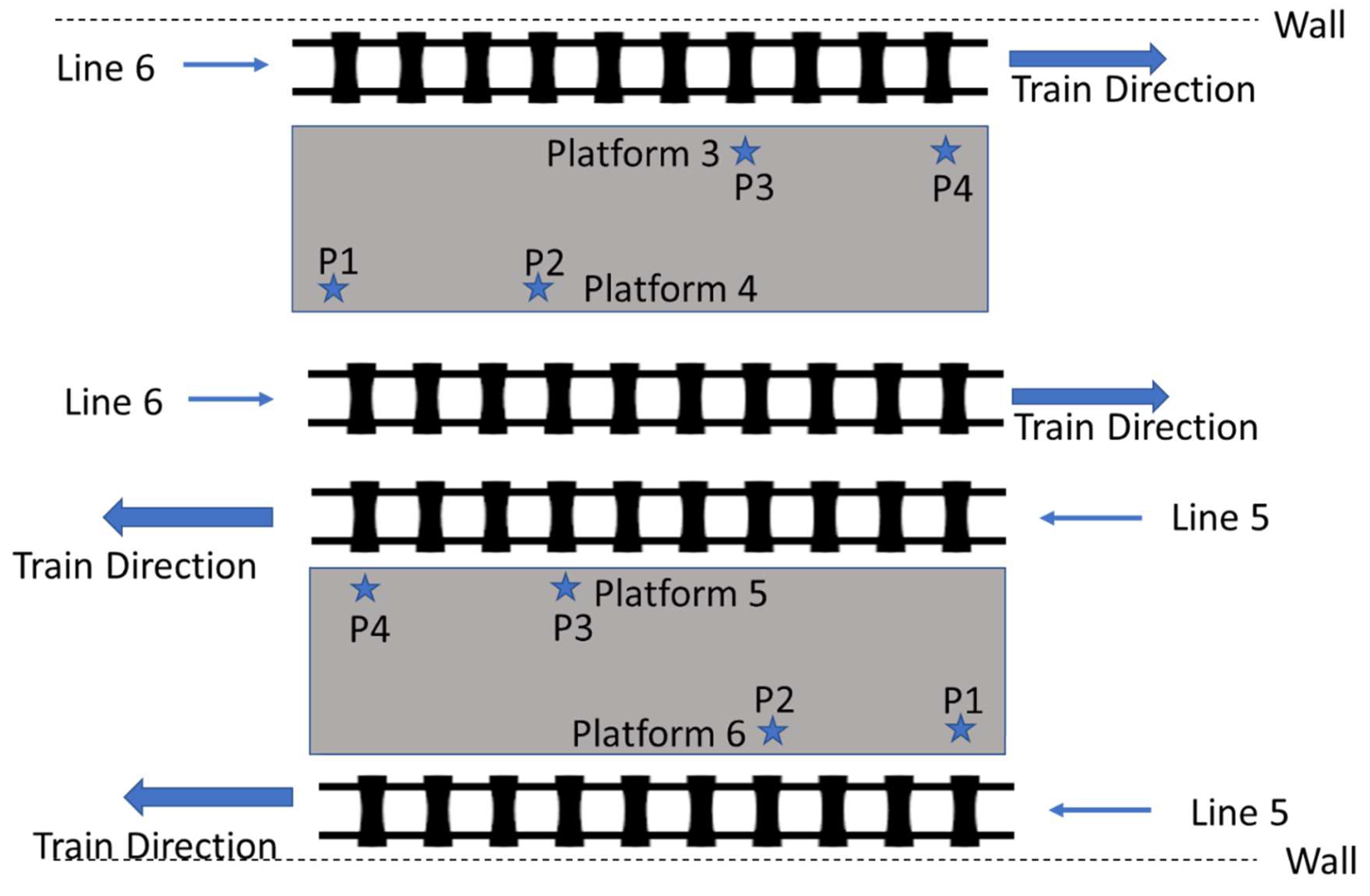

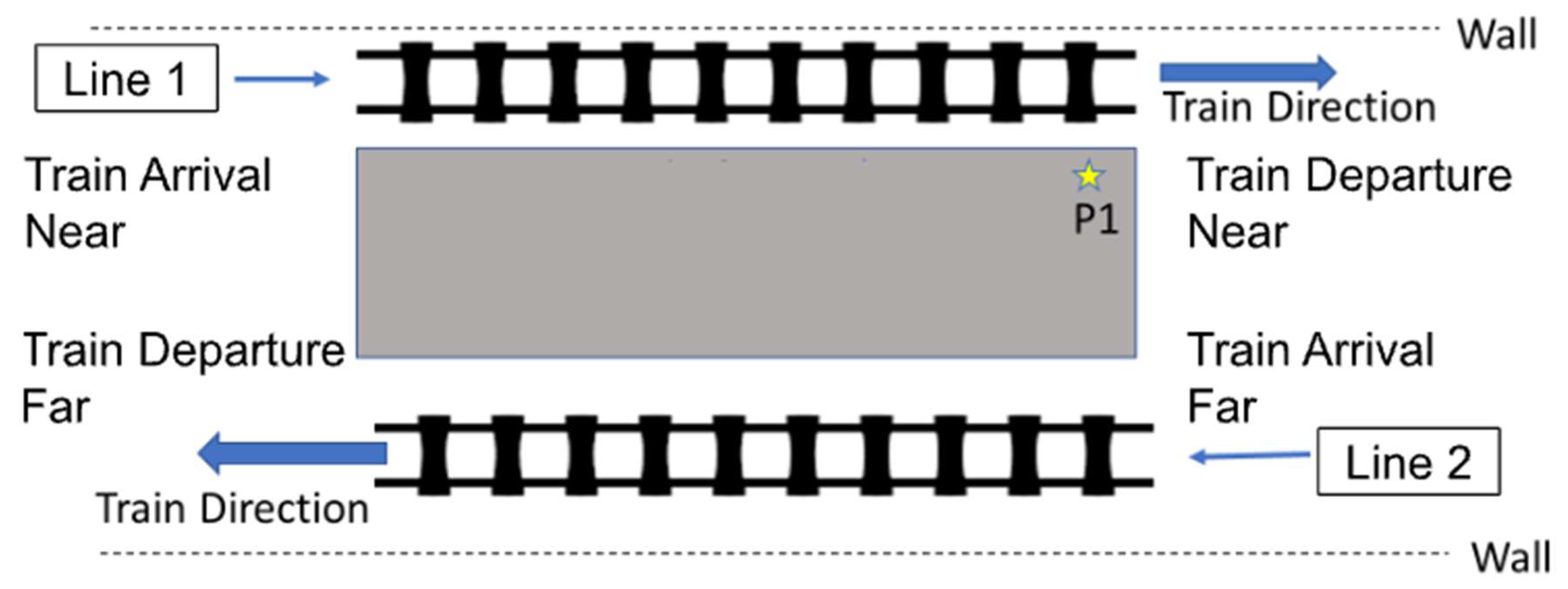

2.2. Description of the Measurement Site and Measurement Setup

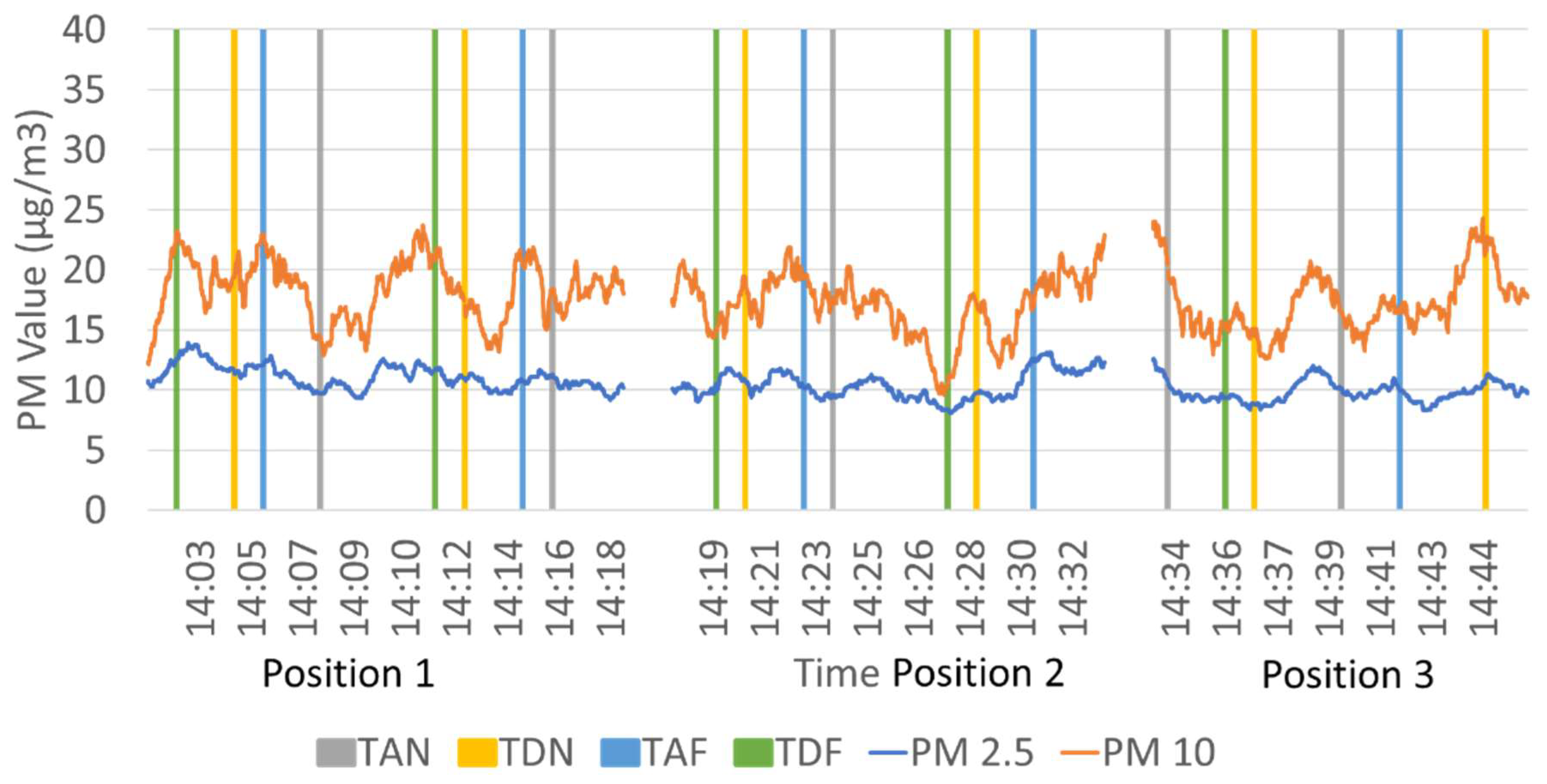

2.3. Parameter Selection

3. Results

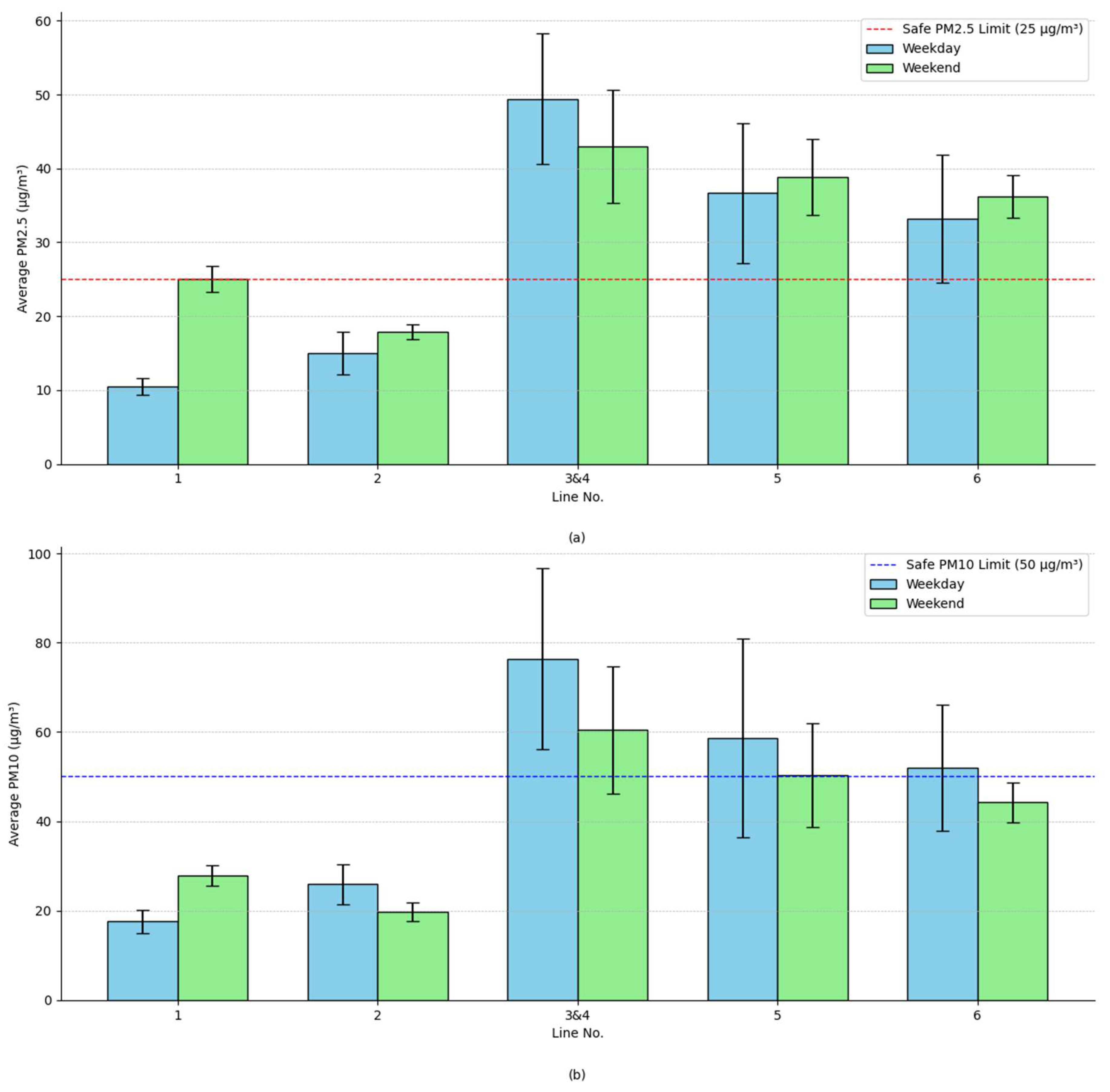

3.1. Comparison of Particulate Matter Measurements Above-Ground and Underground Lines

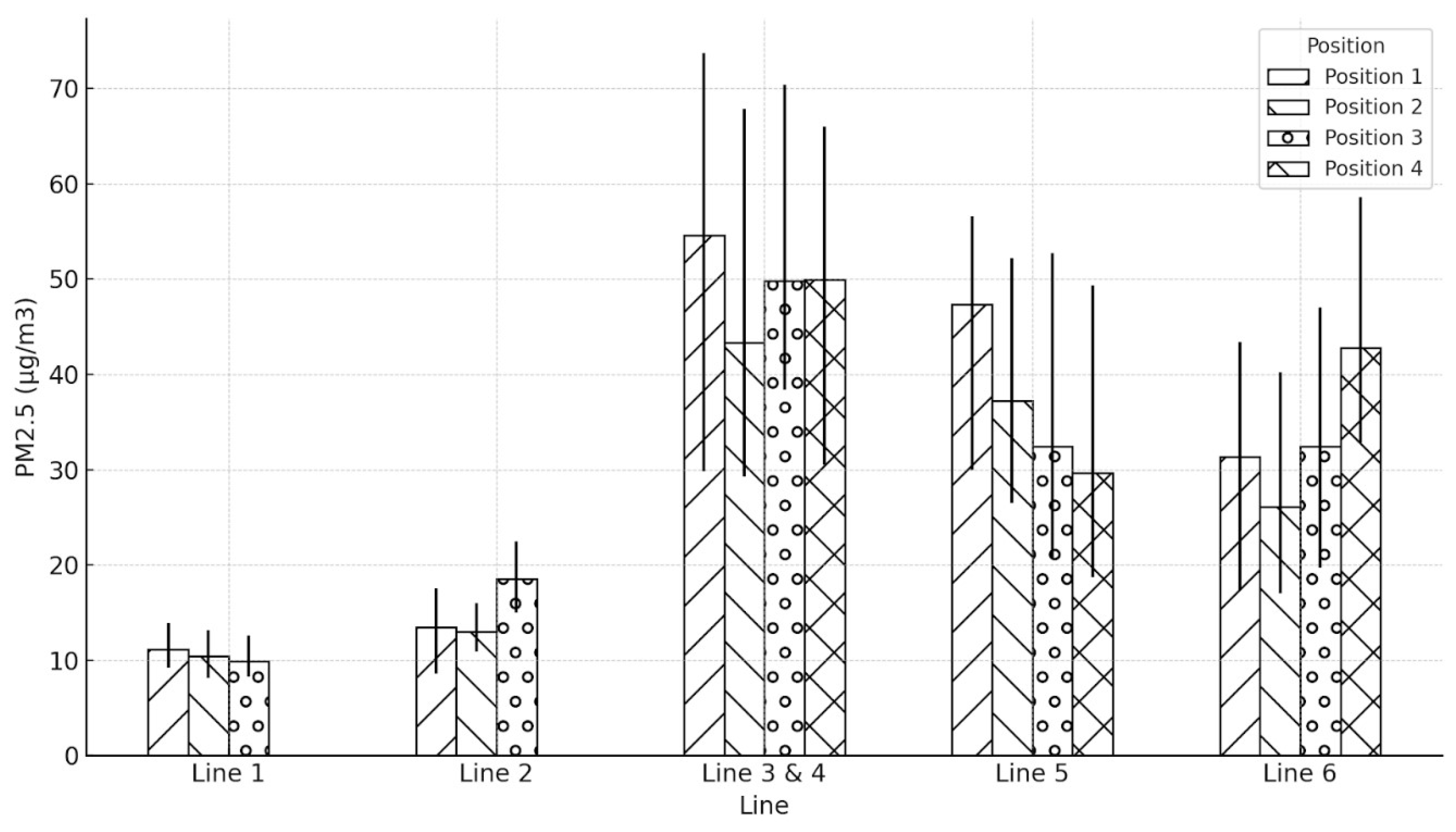

| Line | Position | Average PM2.5 (µg/m3) | Min PM2.5 (µg/m3) | Max PM2.5 (µg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | Position 1 | 11.1 | 9.2 | 13.9 |

| Position 2 | 10.4 | 8.1 | 13.1 | |

| Position 3 | 9.86 | 8.3 | 12.6 | |

| Position 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Line 2 | Position 1 | 13.44 | 8.6 | 17.5 |

| Position 2 | 13 | 10.9 | 16 | |

| Position 3 | 18.55 | 15 | 22.5 | |

| Position 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Line 3 & 4 | Position 1 | 54.61 | 29.8 | 73.7 |

| Position 2 | 43.33 | 29.3 | 67.9 | |

| Position 3 | 49.81 | 38.4 | 70.4 | |

| Position 4 | 49.97 | 30.5 | 66 | |

| Line 5 | Position 1 | 47.36 | 30 | 56.6 |

| Position 2 | 37.25 | 26.5 | 52.2 | |

| Position 3 | 32.41 | 20.8 | 52.7 | |

| Position 4 | 29.62 | 18.7 | 49.3 | |

| Line 6 | Position 1 | 31.34 | 17.4 | 43.4 |

| Position 2 | 26.13 | 17 | 40.2 | |

| Position 3 | 32.41 | 19.7 | 47 | |

| Position 4 | 42.78 | 32.8 | 58.6 |

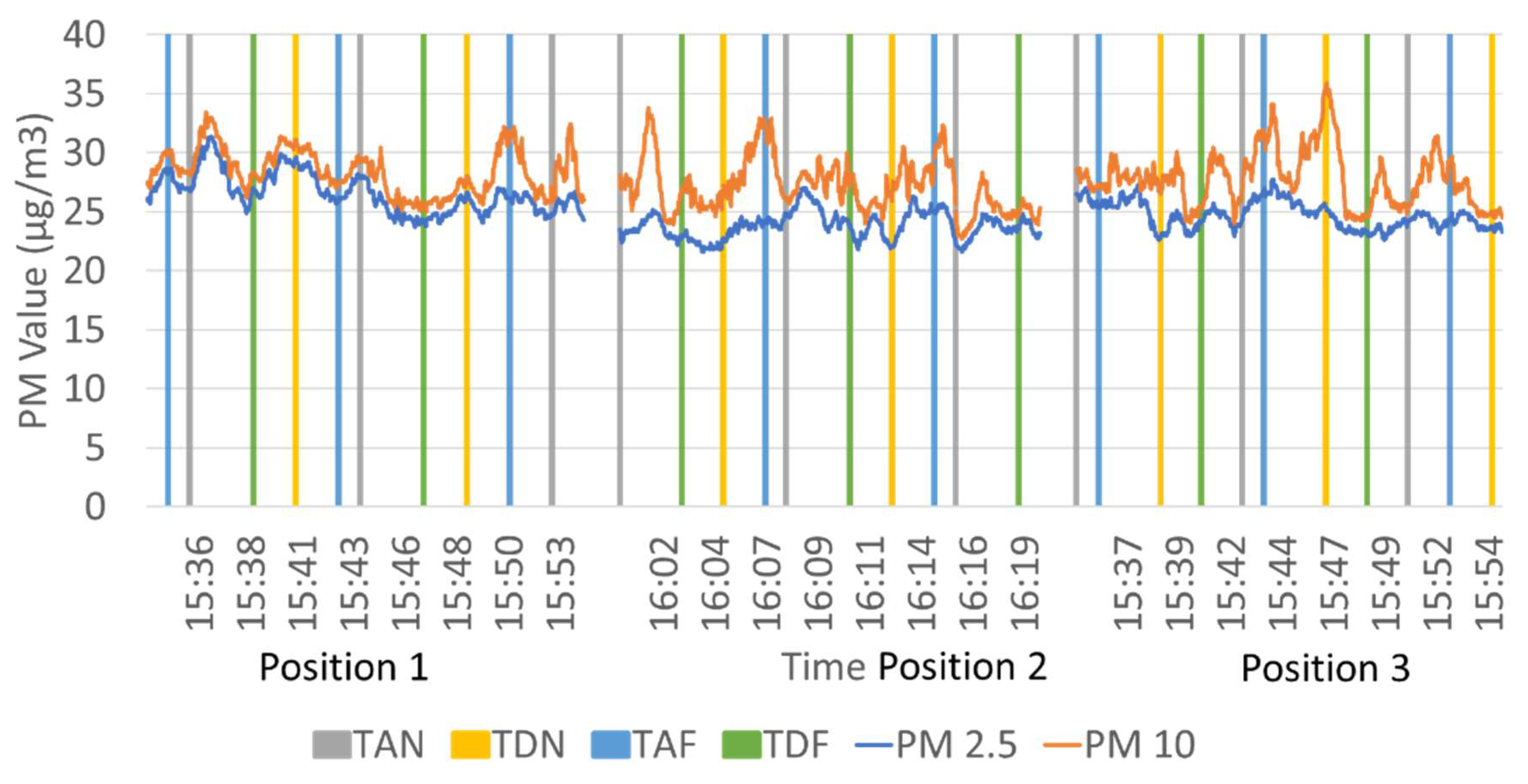

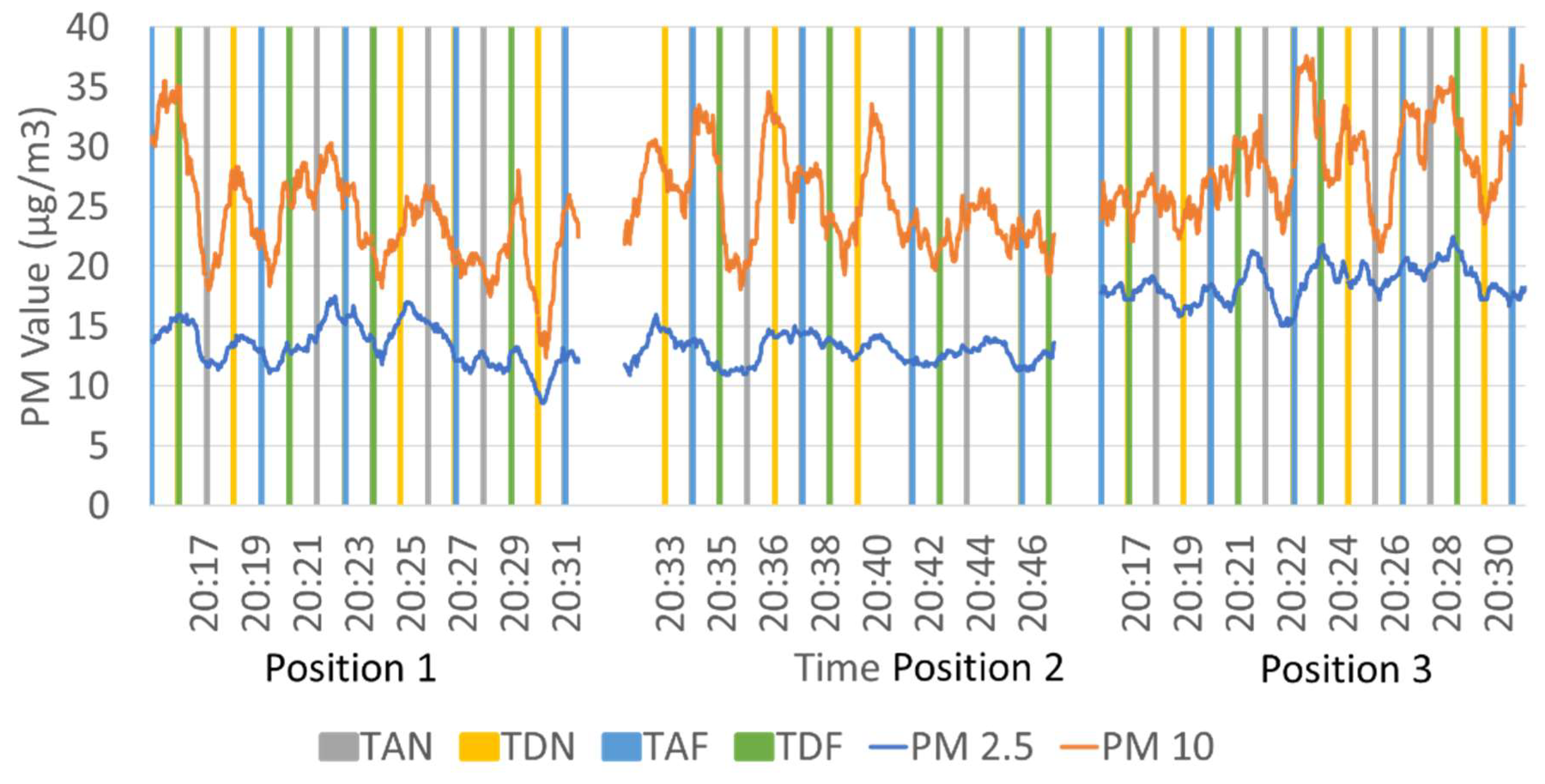

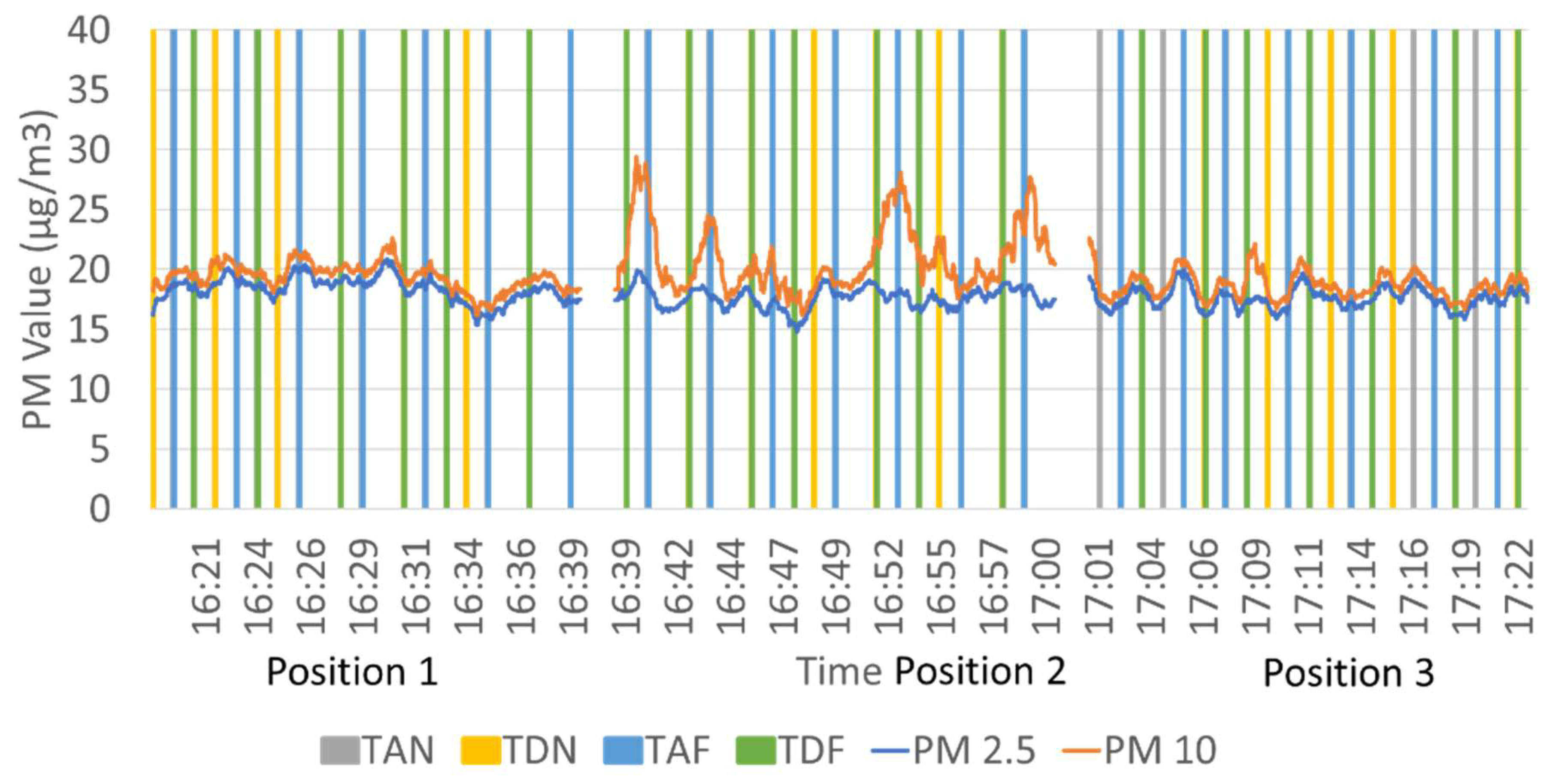

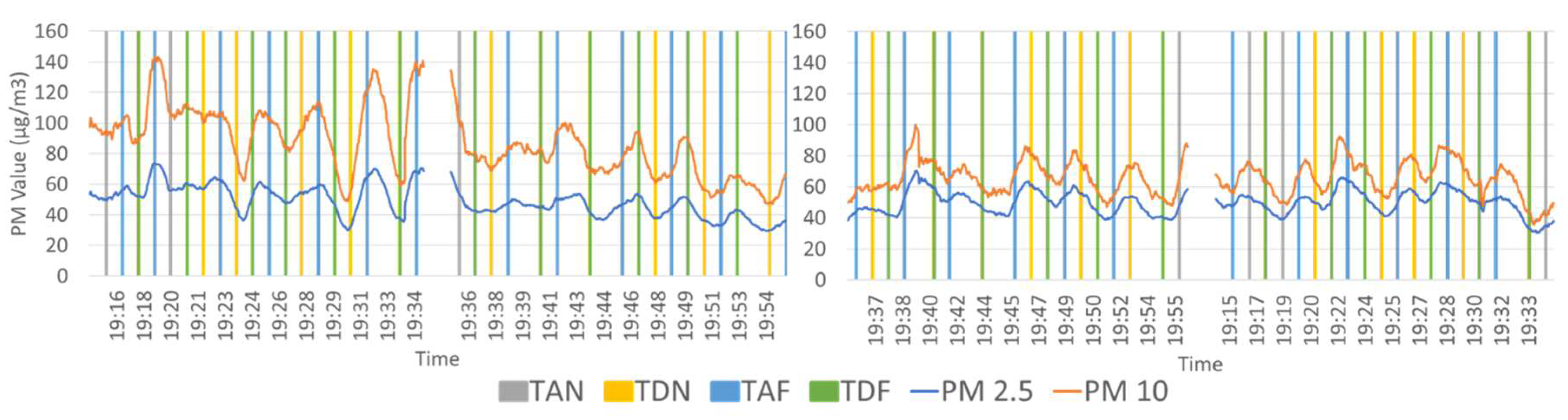

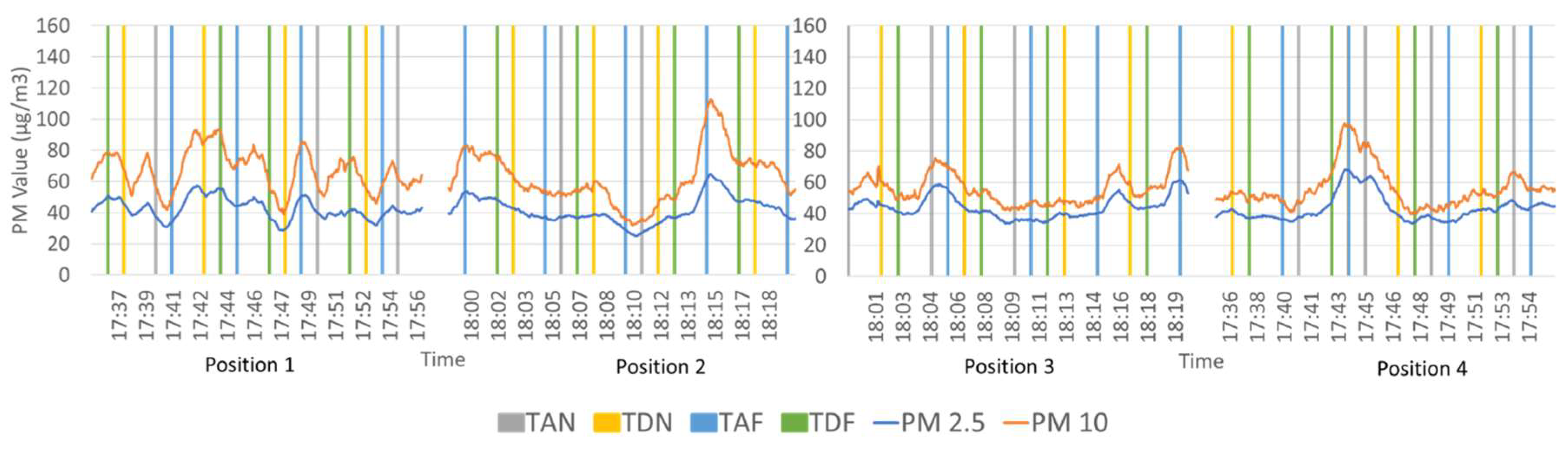

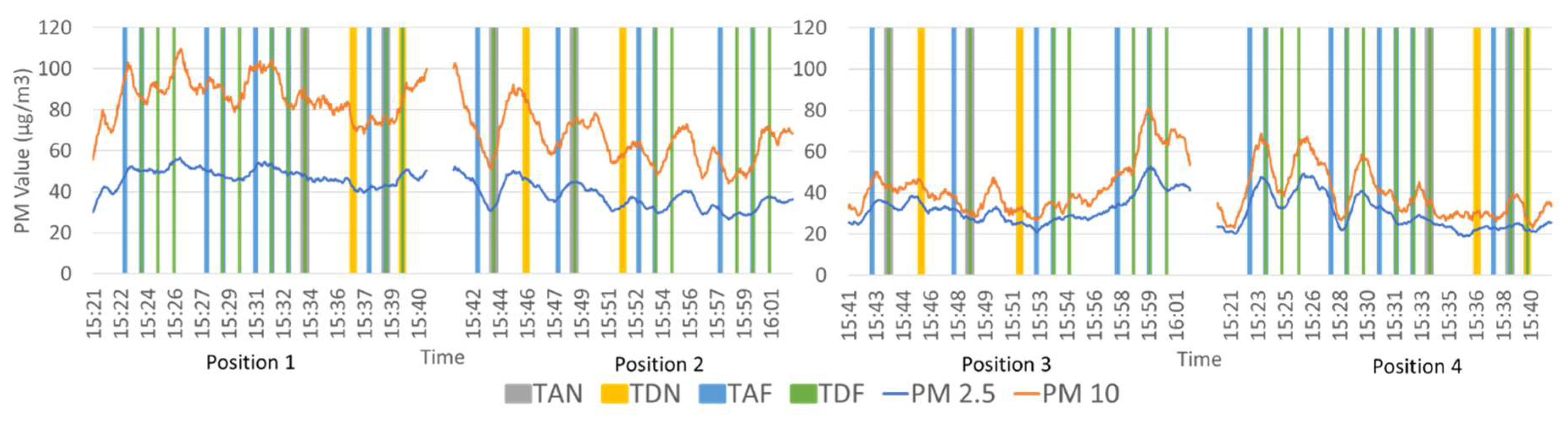

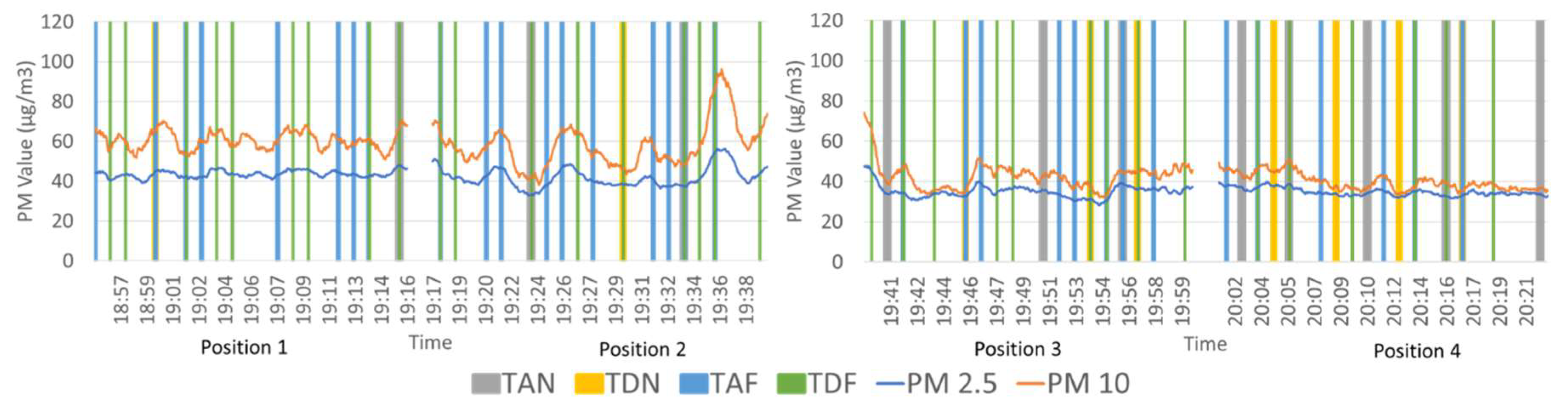

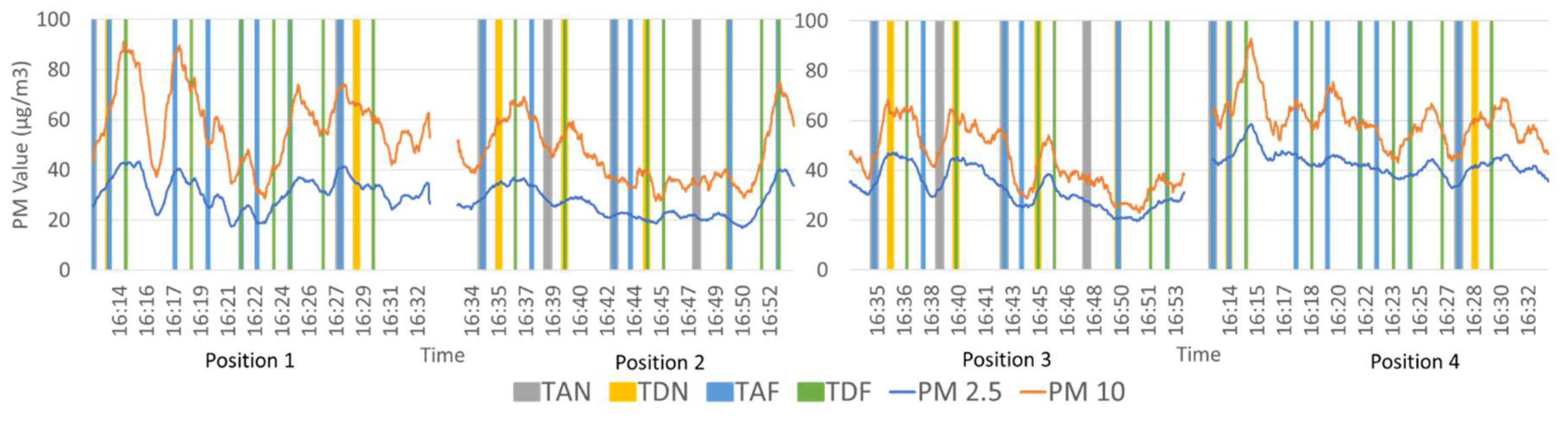

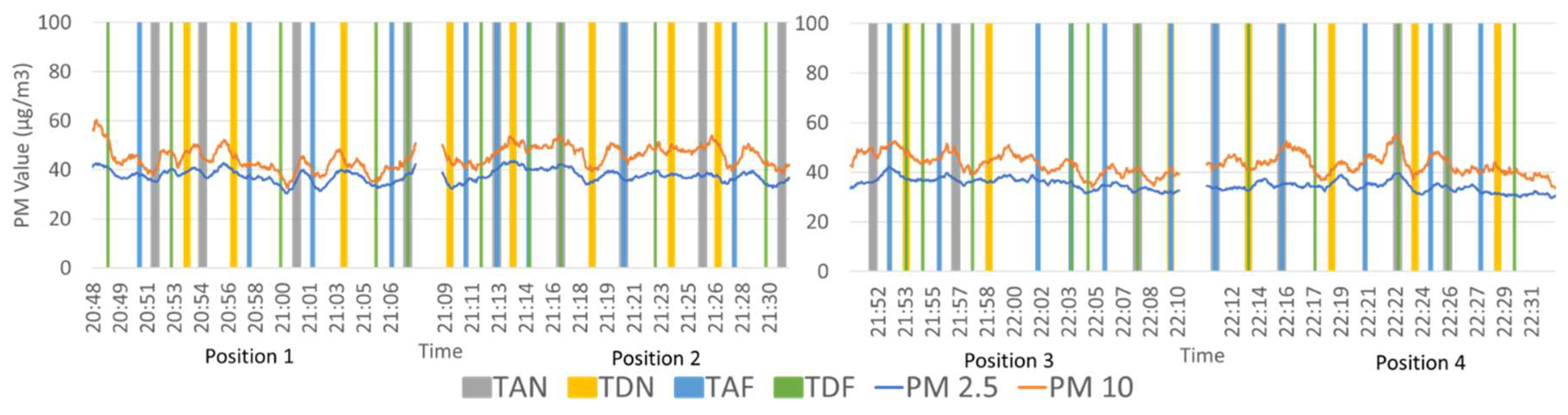

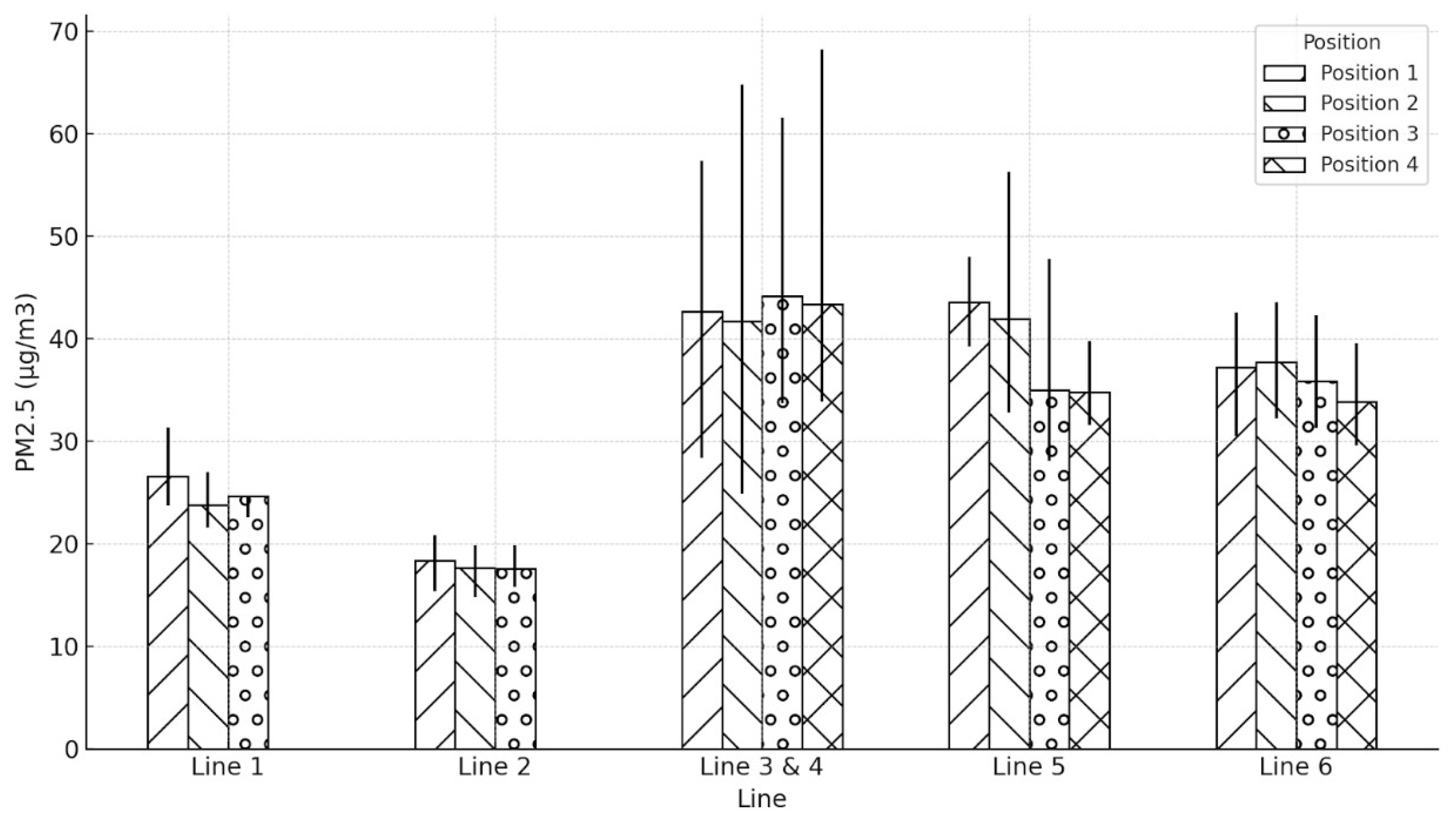

3.2. Comparison of PM Level at Different Positions on the Platform

4. Discussion

4.1. PM2.5 Levels at Different Platforms

| City | Measurement Year | PM₂.₅ (µg/m³) | PM₁₀ (µg/m³) | Platform Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athens [36] | Jun–Aug 2012 | 50.18 | 195.27 | Underground |

| Athens [33] | Apr 2013–Mar 2014 | 68.3 | — | Underground |

| Barcelona [33] | Apr 2013–Mar 2014 | 58.3 | — | Underground |

| Barcelona [31] | Oct-Nov 2014 | 42.7 | — | Underground |

| Beijing [37] | Oct 2016 | 250 | 425 | Underground |

| Frankfurt [38] | August 2013 | 52 | 92 | Underground |

| Helsinki [39] | March 2004 | 60 | — | Underground |

| Hong Kong [40] | May–Sep 2013 | 10.2 | — | Underground |

| Istanbul [41,42] | Sep–Oct 2007 | 105 | 200 | Underground |

| Italian Metro [43] | January 2014 | 52.3 | 195 | Underground |

| Lisbon [44] | Oct 2014–Mar 2015 | 13 | 40 | Underground |

| Los Angeles [22] | May–Aug 2010 | 56.7 | 78 | Underground |

| Los Angeles [22] | May–Aug 2010 | 29.4 | 38.2 | Above ground |

| Mexico City [45] | Apr–Aug 2002 | 106.2 | — | Underground |

| Mexico City [12] | Nov–Dec 2007 | 37 | 44 | Underground |

| Montreal [46] | 2010–2013 | 31.3 | — | Underground |

| Oporto [33] | Apr 2013–Mar 2014 | 83.7 | — | Underground |

| Prague [47] | Mar 2003–Feb 2004 | — | 120.2 | Underground |

| Seoul [18] | Nov 2004–Feb 2005 | 129 | 359 | Underground |

| Seoul [48] | Mar 2008–Feb 2009 | 52.2 | 75.7 | Underground |

| Seoul [19] | Jan 2007 | 115.6 | 129.3 | Underground |

| Shanghai [49] | 2008 | 287 | 366 | Underground |

| Stockholm [50] | Jan–Feb 2000 | 258 | 469 | Underground |

| Sydney [51] | Sep–Nov 2015 | 40.6 | 54.9 | Underground |

| Sydney [52] | June 2015 - June 2016 | 98 | 102 | Underground |

| Taipei [53] | Oct–Dec 2007 | 35 | 51 | Underground |

| Taipei [54] | Aug–Nov 2010 | 28 | 37 | Underground |

| Taipei [55] | 2016 | 75.4 | 97.2 | Underground |

| Toronto [46] | 2010–2013 | 124.6 | — | Underground |

| Vancouver [46] | 2010–2013 | 18.3 | — | Underground |

| Tokyo (this study) | Aug 2019 | 17.09 | 22.73 | Above ground |

| Tokyo (this study) | Aug 2019 | 39.54 | 56.98 | Underground |

4.2. PM2.5 Levels at Different Positions on the Platform

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Sundell, J. On the History of Indoor Air Quality and Health History. Indoor Air 2004, 14, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centnerová, L.H. On the History of Indoor Environment and It’s Relation to Health and Wellbeing. REHVA Journal 2018, 55, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brunekreef, B.; Holgate, S.T. Air Pollution and Health. The Lancet 2002, 360, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, A.; Suresh, R.; Gupta, A.; Singh, D.; Kulshrestha, P. Indoor Air Quality of Non-Residential Urban Buildings in Delhi, India. International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 2017, 6, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.O.; Kim, Y.S.; Perry, R. Indoor Air Quality in Homes, Offices and Restaurants in Korean Urban Areas—Indoor/Outdoor Relationships. Atmos Environ 1997, 31, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Int Panis, L.; de Geus, B.; Vandenbulcke, G.; Willems, H.; Degraeuwe, B.; Bleux, N.; Mishra, V.; Thomas, I.; Meeusen, R. Exposure to Particulate Matter in Traffic: A Comparison of Cyclists and Car Passengers. Atmos Environ 2010, 44, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nazelle, A.; Fruin, S.; Westerdahl, D.; Martinez, D.; Ripoll, A.; Kubesch, N.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. A Travel Mode Comparison of Commuters’ Exposures to Air Pollutants in Barcelona. Atmos Environ 2012, 59, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.; Moreno, T.; Minguillón, M.C.; Amato, F.; de Miguel, E.; Capdevila, M.; Querol, X. Exposure to Airborne Particulate Matter in the Subway System. Science of The Total Environment 2015, 511, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, I.; Kumar, P.; Hagen-Zanker, A. Exposure to Air Pollutants during Commuting in London: Are There Inequalities among Different Socio-Economic Groups? Environ Int 2017, 101, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.S.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Colvile, R.N.; McMullen, M.A.S.; Khandelwal, P. Fine Particle (PM2.5) Personal Exposure Levels in Transport Microenvironments, London, UK. Science of The Total Environment 2001, 279, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Kim, B.W.; Malek, M.A.; Koo, Y.S.; Jung, J.H.; Son, Y.S.; Kim, J.C.; Kim, H.K.; Ro, C.U. Chemical Speciation of Size-Segregated Floor Dusts and Airborne Magnetic Particles Collected at Underground Subway Stations in Seoul, Korea. J Hazard Mater 2012, 213–214, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugica-Álvarez, V.; Figueroa-Lara, J.; Romero-Romo, M.; Sepúlvea-Sánchez, J.; López-Moreno, T. Concentrations and Properties of Airborne Particles in the Mexico City Subway System. Atmos Environ 2012, 49, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.; Moreno, T.; Minguillón, M.C.; Van Drooge, B.L.; Reche, C.; Amato, F.; De Miguel, E.; Capdevila, M.; Centelles, S.; Querol, X. Origin of Inorganic and Organic Components of PM2.5 in Subway Stations of Barcelona, Spain. Environmental Pollution 2016, 208, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitzmann, B.; Kendall, M.; Watt, J.; Williams, I. Characterisation of Airborne Particles in London by Computer-Controlled Scanning Electron Microscopy. Science of The Total Environment 1999, 241, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yu, X.; Gu, H.; Miao, B.; Wang, M.; Huang, H. Commuters’ Exposure to PM2.5 and CO2 in Metro Carriages of Shanghai Metro System. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2016, 47, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T.; Xiu, G.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Huang, Z. Preliminary Investigation of PM1, PM2.5, PM10 and Its Metal Elemental Composition in Tunnels at a Subway Station in Shanghai, China. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2015, 41, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Liu, D.; Zhang, W.; Liu, P.; Fei, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wu, M.; Yu, S.; Yonemochi, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Physico-Chemical Characterization of PM2.5 in the Microenvironment of Shanghai Subway. Atmos Res 2015, 153, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Roh, Y.M.; Lee, C.M.; Kim, C.N. Spatial Distribution of Particulate Matter (PM10 and PM2.5) in Seoul Metropolitan Subway Stations. J Hazard Mater 2008, 154, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.U.; Ha, K.C. Characteristics of PM10, PM2.5, CO2 and CO Monitored in Interiors and Platforms of Subway Train in Seoul, Korea. Environ Int 2008, 34, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilcassim, M.J.R.; Thurston, G.D.; Peltier, R.E.; Gordon, T. Black Carbon and Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Concentrations in New York City’s Subway Stations. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48, 14738–14745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Oliver Gao, H. Exposure to Fine Particle Mass and Number Concentrations in Urban Transportation Environments of New York City. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2011, 16, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, W.; Cheung, K.; Daher, N.; Sioutas, C. Particulate Matter (PM) Concentrations in Underground and Ground-Level Rail Systems of the Los Angeles Metro. Atmos Environ 2011, 45, 1506–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Fan, L.; Liu, J.; Xie, J.; Sun, Y.; Cui, N.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, B. A Review of the Piston Effect in Subway Stations. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/950205 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ishigaki, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Pradana, H.A.; Matsumoto, Y.; Maruo, Y.Y. Citizen Sensing for Environmental Risk Communication. CYBER 2017.

- Keio Corporation Shibuya Station Map.

- Moreno, T.; Reche, C.; Minguillón, M.C.; Capdevila, M.; de Miguel, E.; Querol, X. The Effect of Ventilation Protocols on Airborne Particulate Matter in Subway Systems. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 584–585, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, J. Case Study of Train-Induced Airflow inside Underground Subway Stations with Simplified Field Test Methods. Sustain Cities Soc 2018, 37, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripanucci, G.; Grana, M.; Vicentini, L.; Magrini, A.; Bergamaschi, A. Dust in the Underground Railway Tunnels of an Italian Town. J Occup Environ Hyg 2006, 3, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Gómez-Perales, J.E.; Colvile, R.N. Levels of Particulate Air Pollution, Its Elemental Composition, Determinants and Health Effects in Metro Systems. Atmos Environ 2007, 41, 7995–8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskell, G.; Salmond, J.A.; Williams, D.E. Use of a Handheld Low-Cost Sensor to Explore the Effect of Urban Design Features on Local-Scale Spatial and Temporal Air Quality Variability. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 619–620, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, T.; Pérez, N.; Reche, C.; Martins, V.; de Miguel, E.; Capdevila, M.; Centelles, S.; Minguillón, M.C.; Amato, F.; Alastuey, A.; et al. Subway Platform Air Quality: Assessing the Influences of Tunnel Ventilation, Train Piston Effect and Station Design. Atmos Environ 2014, 92, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.B.; Jeong, W.; Park, D.; Kim, K.T.; Cho, K.H. A Multivariate Study for Characterizing Particulate Matter (PM10, PM2.5, and PM1) in Seoul Metropolitan Subway Stations, Korea. J Hazard Mater 2015, 297, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.; Minguillón, M.C.; Moreno, T.; Mendes, L.; Eleftheriadis, K.; Alves, C.A.; Querol, E. de M. and X.; Martins, V.; Minguillón, M.C.; Moreno, T.; et al. Characterisation of Airborne Particulate Matter in Different European Subway Systems. Urban Transport Systems 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Leng, J.; Shen, X.; Han, G.; Sun, L.; Yu, F. Environmental and Health Effects of Ventilation in Subway Stations: A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, Vol. 17, Page 1084 2020, 17, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q. Urbanization and Global Health: The Role of Air Pollution. Iran J Public Health 2018, 47, 1644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barmparesos, N.; Assimakopoulos, V.D.; Assimakopoulos, M.N.; Tsairidi, E. Particulate Matter Levels and Comfort Conditions in the Trains and Platforms of the Athens Underground Metro. AIMS Environ Sci 2016, 3, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Du, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xia, L.; Liu, J.; Pei, F.; Wei, Y. Analysis and Interpretation of the Particulate Matter (PM10 and PM2.5) Concentrations at the Subway Stations in Beijing, China. Sustain Cities Soc 2019, 45, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A.; Bohn, J.; Groneberg, D.A.; Schulze, J.; Bundschuh, M. Airborne Particulate Matter in Public Transport: A Field Study at Major Intersection Points in Frankfurt Am Main (Germany). Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology 2014, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnio, P.; Yli-Tuomi, T.; Kousa, A.; Mäkelä, T.; Hirsikko, A.; Hämeri, K.; Räisänen, M.; Hillamo, R.; Koskentalo, T.; Jantunen, M. The Concentrations and Composition of and Exposure to Fine Particles (PM2.5) in the Helsinki Subway System. Atmos Environ 2005, 39, 5059–5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Kaul, D.; Wong, K.C.; Westerdahl, D.; Sun, L.; Ho, K.f.; Tian, L.; Brimblecombe, P.; Ning, Z. Heterogeneity of Passenger Exposure to Air Pollutants in Public Transport Microenvironments. Atmos Environ 2015, 109, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Ü.A.; Onat, B.; Stakeeva, B.; Ceran, T.; Karim, P. PM10 Concentrations and the Size Distribution of Cu and Fe-Containing Particles in Istanbul’s Subway System. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2012, 17, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, B.; Stakeeva, B. Assessment of Fine Particulate Matters in the Subway System of Istanbul. Indoor and Built Environment 2014, 23, 574–583, doi:10.1177/1420326X12464507/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_1420326X12464507-FIG8.JPEG.

- Cartenì, A.; Cascetta, F.; Campana, S. Underground and Ground-Level Particulate Matter Concentrations in an Italian Metro System. Atmos Environ 2015, 101, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.J.; Vasconcelos, A.; Faria, M. Comparison of Particulate Matter Inhalation for Users of Different Transport Modes in Lisbon. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier, 2015; Vol. 10, pp. 433–442.

- Vallejo, M.; Lerma, C.; Infante, O.; Hermosillo, A.G.; Riojas-Rodriguez, H.; Cardenas, M. Personal Exposure to Particulate Matter Less than 2.5 Μm in Mexico City: A Pilot Study. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 2004, 14, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryswyk, K.; Anastasopolos, A.T.; Evans, G.; Sun, L.; Sabaliauskas, K.; Kulka, R.; Wallace, L.; Weichenthal, S. Metro Commuter Exposures to Particulate Air Pollution and PM2.5-Associated Elements in Three Canadian Cities: The Urban Transportation Exposure Study. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, 5713–5720, doi:10.1021/ACS.EST.6B05775/ASSET/IMAGES/ES-2016-05775P_M004.GIF.

- Branǐ, M. The Contribution of Ambient Sources to Particulate Pollution in Spaces and Trains of the Prague Underground Transport System. Atmos Environ 2006, 40, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Sankararao, B.; Kang, O.; Kim, J.; Yoo, C. Monitoring and Prediction of Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) in Subway or Metro Systems Using Season Dependent Models. Energy Build 2012, 46, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Lian, Z.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, H. Investigation of Indoor Environmental Quality in Shanghai Metro Stations, China. Environ Monit Assess 2010, 167, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, C.; Johansson, P.Å. Particulate Matter in the Underground of Stockholm. Atmos Environ 2003, 37, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, M.; Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L. Particulate Matter Concentrations and Heavy Metal Contamination Levels in the Railway Transport System of Sydney, Australia. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2018, 62, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolourchi, A.; Atabi, F.; Moattar, F.; Ehyaei, M.A. Experimental and Numerical Analyses of Particulate Matter Concentrations in Underground Subway Station. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2018, 15, 2569–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Lin, Y.L.; Liu, C.C. Levels of PM10 and PM2.5 in Taipei Rapid Transit System. Atmos Environ 2008, 42, 7242–7249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Liu, Z.S.; Yan, J.W. Comparisons of PM10, PM2.5, Particle Number, and CO2 Levels inside Metro Trains between Traveling in Underground Tunnels and on Elevated Tracks. Aerosol Air Qual Res 2012, 12, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Sung, F.C.; Chen, M.L.; Mao, I.F.; Lu, C.Y. Indoor Air Quality in the Metro System in North Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Line No. | Line Location | Number of measurement positions | Measurement Date | Day Type | Measurement Time | Measurement Duration (minutes) | Average intervals between trains (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Above Ground | 3 | 2019/08/15 | Weekday | 14:02 – 14:46 | 45 | 4 |

| 2019/08/17 | Weekend | 15:34 – 16:19 | 45 | 4 | |||

| 2 | Above Ground | 3 | 2019/08/15 | Weekday | 20:17 – 20:46 | 29 | 1.7 |

| 2019/08/18 | Weekend | 16:21 – 17:22 | 61 | 1.5 | |||

| 3 & 4 | Underground (B3F) | 4 | 2019/08/15 | Weekday | 19:16 – 19:54 | 38 | 1.6 |

| 2019/08/18 | Weekend | 17:37 – 18:18 | 41 | 2.3 | |||

| 5 | Underground (B5F) | 4 | 2019/08/15 | Weekday | 15:21 – 16:01 | 40 | 1.9 |

| 2019/08/18 | Weekend | 18:57 – 20:21 | 84 | 1.9 | |||

| 6 | Underground (B5F) | 4 | 2019/08/15 | Weekday | 16:15 – 16:55 | 40 | 1.9 |

| 2019/08/18 | Weekend | 20:45 – 22:35 (with 25 minutes rest) | 85 | 1.9 |

| Line No. | Average PM2.5 levels (µg/m3) | Variance PM2.5 | Average PM10 levels (µg/m3) | Variance PM10 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | Overall | Weekday | Weekend | Weekday | Weekend | Overall | Weekday | Weekend | |

| 1 | 10.45 | 25.03 | 17.74 | 1.28 | 3.14 | 17.57 | 27.79 | 22.68 | 6.91 | 5.03 |

| 2 | 15.00 | 17.87 | 18.10 | 8.58 | 0.98 | 25.89 | 19.66 | 22.78 | 19.34 | 4.25 |

| 3&4 | 49.43 | 42.98 | 46.20 | 78.24 | 58.53 | 76.35 | 60.47 | 68.41 | 410.85 | 203.42 |

| 5 | 36.66 | 38.84 | 37.75 | 89.16 | 26.43 | 58.58 | 50.28 | 54.43 | 494.41 | 134.40 |

| 6 | 33.17 | 36.18 | 34.67 | 74.82 | 8.12 | 51.99 | 44.22 | 48.11 | 197.85 | 19.85 |

| Line | Position | Average PM2.5 (µg/m3) | Min PM2.5 (µg/m3) | Max PM2.5 (µg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | Position 1 | 26.57 | 23.7 | 31.4 |

| Position 2 | 23.83 | 21.6 | 27 | |

| Position 3 | 24.69 | 22.6 | 24.69 | |

| Position 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Line 2 | Position 1 | 18.38 | 15.4 | 20.9 |

| Position 2 | 17.63 | 14.8 | 19.9 | |

| Position 3 | 17.61 | 15.8 | 19.9 | |

| Position 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Line 3 & 4 | Position 1 | 42.65 | 28.4 | 57.4 |

| Position 2 | 41.75 | 24.9 | 64.8 | |

| Position 3 | 44.16 | 33.7 | 61.6 | |

| Position 4 | 43.35 | 33.9 | 68.2 | |

| Line 5 | Position 1 | 43.58 | 39.2 | 48 |

| Position 2 | 41.93 | 32.8 | 56.3 | |

| Position 3 | 35.04 | 28.1 | 47.8 | |

| Position 4 | 34.81 | 31.6 | 39.8 | |

| Line 6 | Position 1 | 37.26 | 30.5 | 42.6 |

| Position 2 | 37.74 | 32.2 | 43.6 | |

| Position 3 | 35.85 | 31.3 | 42.3 | |

| Position 4 | 33.86 | 29.6 | 39.6 |

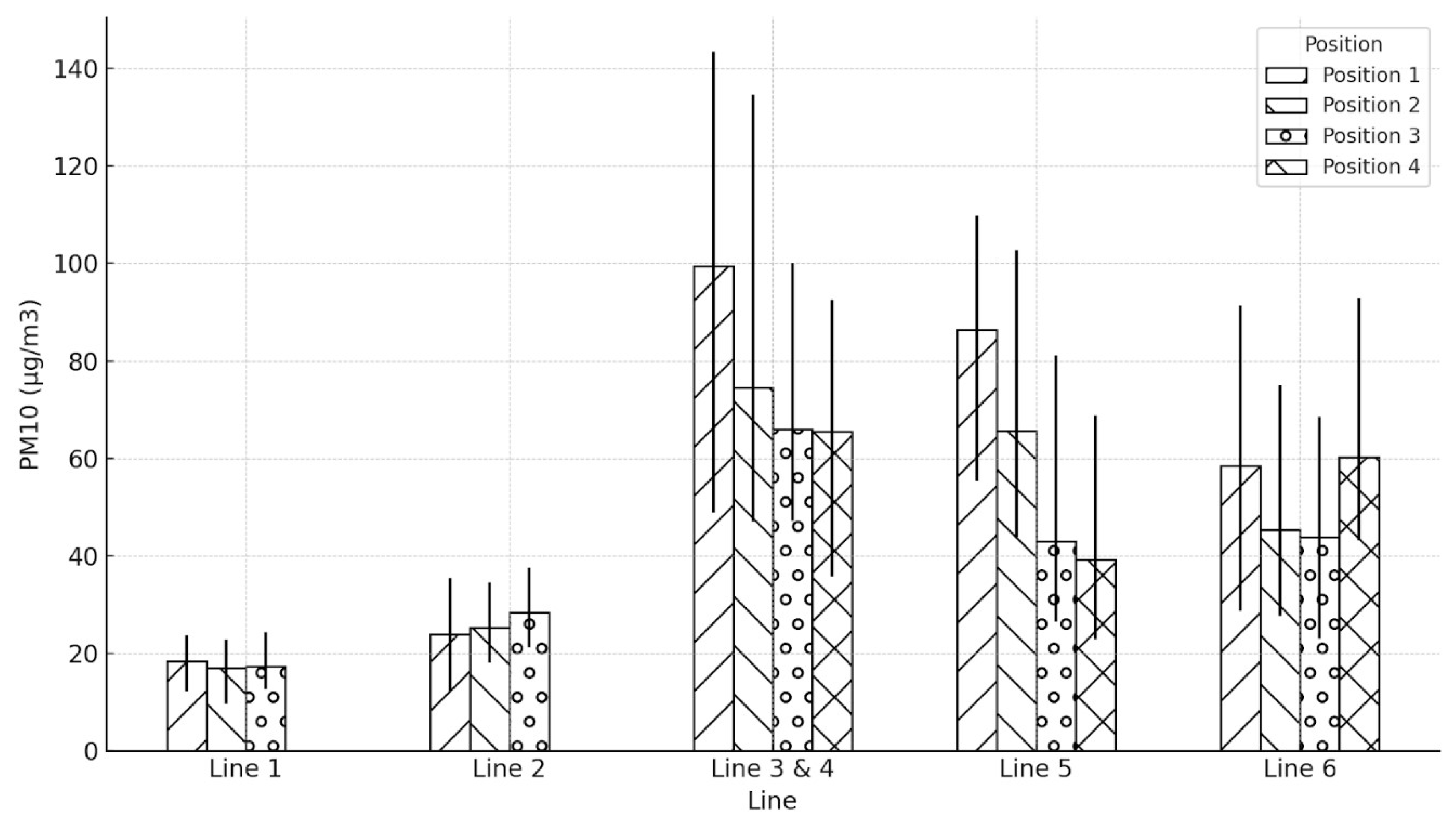

| Line | Position | Average PM10 (µg/m3) | Min PM10 (µg/m3) | Max PM10 (µg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | Position 1 | 18.42 | 12.2 | 23.7 |

| Position 2 | 17.04 | 9.6 | 22.9 | |

| Position 3 | 17.24 | 12.6 | 24.3 | |

| Position 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Line 2 | Position 1 | 23.92 | 12.4 | 35.5 |

| Position 2 | 25.29 | 18.1 | 34.6 | |

| Position 3 | 28.46 | 21.2 | 37.6 | |

| Position 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Line 3 & 4 | Position 1 | 99.39 | 48.9 | 143.4 |

| Position 2 | 74.53 | 47 | 134.6 | |

| Position 3 | 66.01 | 47.2 | 100.1 | |

| Position 4 | 65.45 | 35.7 | 92.5 | |

| Line 5 | Position 1 | 86.44 | 55.5 | 109.8 |

| Position 2 | 65.61 | 43.9 | 102.7 | |

| Position 3 | 43.02 | 26.4 | 81.1 | |

| Position 4 | 39.25 | 22.8 | 68.8 | |

| Line 6 | Position 1 | 58.52 | 28.7 | 91.3 |

| Position 2 | 45.32 | 27.6 | 75 | |

| Position 3 | 43.93 | 23 | 68.5 | |

| Position 4 | 60.2 | 43.1 | 92.9 |

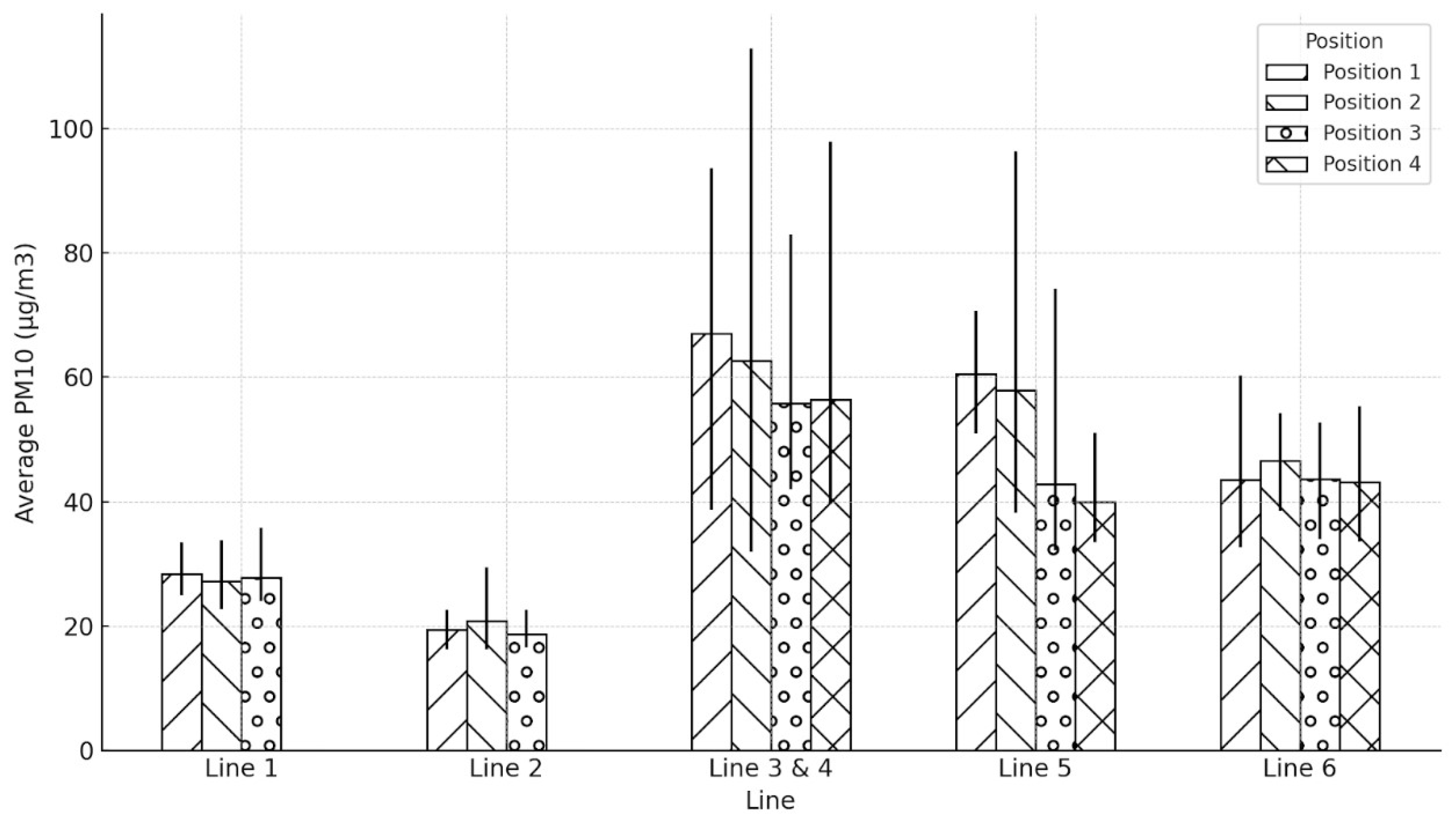

| Line | Position | Average PM10 (µg/m3) | Min PM10 (µg/m3) | Max PM10 (µg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | Position 1 | 28.39 | 25 | 33.4 |

| Position 2 | 27.15 | 22.7 | 33.8 | |

| Position 3 | 27.84 | 24 | 35.8 | |

| Position 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Line 2 | Position 1 | 19.41 | 16.2 | 22.6 |

| Position 2 | 20.87 | 16.2 | 29.4 | |

| Position 3 | 18.69 | 16.6 | 22.6 | |

| Position 4 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Line 3 & 4 | Position 1 | 67.06 | 38.7 | 93.6 |

| Position 2 | 62.59 | 31.9 | 112.8 | |

| Position 3 | 55.84 | 42 | 83 | |

| Position 4 | 56.37 | 39.6 | 97.8 | |

| Line 5 | Position 1 | 60.55 | 50.9 | 70.7 |

| Position 2 | 57.87 | 38.2 | 96.3 | |

| Position 3 | 42.76 | 32.2 | 74.2 | |

| Position 4 | 39.92 | 33.5 | 51 | |

| Line 6 | Position 1 | 43.54 | 32.6 | 60.3 |

| Position 2 | 46.61 | 38.5 | 54.3 | |

| Position 3 | 43.59 | 33.9 | 52.7 | |

| Position 4 | 43.14 | 33.6 | 55.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).