1. Introduction

Gender identification of authors in literary texts is an interesting field of study in computational linguistics. Determining the gender of authors can reveal prejudices and underlying socio-cultural dynamics that were present in the literary world and enhance our understanding of literary works. Historical examples support this endeavor, as women who encountered obstacles to publication and recognition often adopted male pseudonyms in the literary world. For example, George Sand, pseudonym of Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin, Baroness Dudevant, a 19th-century French writer and memoirist with her books [

1,

2]. Vernon Lee, the pseudonym of British writer Violet Paget with [

3,

4]. James Tiptree, Jr., Alice Sheldon pseudonym with books [

5,

6]. An additional example is the Brontë sisters, who adopted male pseudonyms, and Mary Ann Evans, who published as George Eliot, highlighting the systemic barriers that have historically hindered women’s participation and visibility in the literary field.

In this study, we aim to identify the gender of the author from the written texts, with a specific focus on literary works such as books and novels.

Our contributions are two-fold:

We present a thoroughly collected dataset comprising a diverse set of literary works span genres, time periods, and cultural contexts, including historical novels (e.g., Romola by Mary Ann Evans), short novels (e.g., Absalom’s Hair by Bjornstjerne Bjornson), long novels (e.g., Moby-Dick by Herman Melville), science fiction novels (e.g., The Confessions of Artemas Quibble by Arthur Train), dime novels (e.g., The Dock Rats of New York by Harlan Page Halsey), mystery adventure novels (e.g., The Danger Trail by James Oliver Curwood), and children’s fiction novels (e.g., Heidi by Johanna Spyri).

We perform extensive comparative experiments with diverse classifiers and analyze their results. In our experiments, GPT2 and XLNet Model ( XLNet ) emerged as the top-performing models. GPT2 achieved the highest overall accuracy score of 0.930 and excelled in precision, recall, and F1 scores for both female and male categories, indicating robust and consistent performance across metrics. XLNet followed closely with a score of 0.910, also demonstrating strong precision and recall, particularly with F1 average of 0.860. Logistic Regression ( LR ) models with various configurations showed moderate performance, with scores around 0.830 to 0.840. The XGB classifier (XGB), especially when fine-tuned, also performed well, achieving a score of 0.850 and decent F1 scores, making it a solid choice among traditional machine learning methods.

We believe that the compiled dataset and the reported results will help advance the field of literary analysis by providing valuable resources and insights.

2. Related Work

The study of automatic gender identification from textual data has garnered significant interest within the domains of sociolinguistics and natural language processing (NLP). Researchers have employed a variety of approaches and strategies, utilizing different datasets and NLP models to identify and analyze gendered language patterns as they appear in textual compositions. This research area encompasses a wide range of activities, including traditional linguistic analyses, advanced machine learning techniques, and deep learning models. Additionally, ethical considerations and societal biases have become prominent themes in this field, influencing the development and application of these technologies. This section aims to provide a detailed overview of linguistic methods and deep learning techniques, traditional machine learning techniques, and benchmark datasets used in the study of gender identification from textual data. We also overview ethical and societal considerations.

2.1. Linguistic Techniques

Studies using several corpora and linguistic inquiries have yielded important insights into the linguistic patterns associated with gender in various linguistic contexts. For example, gender differences in word choice, syntactic structures, and thematic content were reported in [

7] (LIWC2001 to LIWC-22) through extensive analyses of language use in written texts. These studies offer empirical support for computational models of gender identification and advance our theoretical understanding of gendered language.

Additionally, interdisciplinary research combining computational social science, gender studies, and NLP has enhanced our understanding of gender stereotypes and representation in textual data. For example, [

8] looked into how gender is expressed linguistically in Wikipedia articles. They found differences in how male and female subjects are covered and represented. Through the integration of qualitative and computational methods, these studies provide a more thorough understanding of the intricate interactions among language, gender, and society.

2.2. Deep Learning Techniques

With the development of deep-learning models, researchers have investigated the effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). [

9] demonstrated that deep learning architectures can effectively capture subtle linguistic patterns by using Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory ( LSTM ) networks to predict the gender of authors based on their Twitter posts. [

10] developed a CNN-based model that outperformed conventional machine-learning techniques for gender identification in Chinese microblogs. [

11] demonstrated the usefulness of pre-trained bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) models for gender prediction tasks.

2.3. Traditional Machine Learning Techniques

Several studies utilized traditional machine learning approaches such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), LR [

12], and Naive Bayes for gender identification tasks. [

13] used SVM classifiers to predict the gender of authors based on linguistic features from email messages. Similarly, [?] combined SVM and Naive Bayes classifiers to identify gender in SMS messages.

2.4. Ethical and Societal Considerations

Several studies have explored the societal biases and ethical ramifications of automatically identifying a person’s gender based on textual data. [

14] emphasized the significance of considering cultural and contextual elements when examining gendered language patterns, highlighting the necessity of ethical and open procedures in gender-related NLP research. Ethical issues such as privacy, consent, and representation have gained prominence, compelling researchers to adopt strict methodologies and frameworks for ethical analysis [

15].

In recent years, the application of machine learning and models like GPT for text author gender identification has seen notable advancements. [

16] showed that existing systems, including advanced ones such as Chat Generative Pre-training Transformer (ChatGPT), are biased and need a better configuration of settings. They argued that societal biases could be addressed and alleviated through simple off-the-shelf models like BERT trained on more gender-inclusive datasets. [

17] assessed the classification rate of state-of-the-art transformer-based models (e.g., BERT and FNET [

18]) on the task of gender identification across Community Question Answering (CQA) fellows. Their best transformer models achieved an accuracy of 0.920 by taking full questions and answers into account (i.e., Decoding-enhanced BERT with Disentangled Attention (DeBERTa) and MobileBERT [

19] ). The qualitative results revealed that fine-tuning on user-generated content is affected by pre-training on clean corpora and that this adverse effect can be mitigated by correcting the case of words.

2.5. Benchmark Datasets

Over the years, efforts to improve the generalizability and robustness of automatic gender identification models have led to the development of benchmark datasets and assessment frameworks. Standardized resources for training and assessing gender identification systems include datasets like the PAN 2017 English dataset [

20] and the Kaggle dataset for text-based gender recognition [

21]. The PAN 2017 English dataset is part of the PAN competition series, which focuses on various authorship analysis tasks, including gender identification. This dataset comprises around 300,000 text samples from social media, blogs, and other online platforms. These texts are in English and are labeled with the author’s gender. The dataset is designed to provide a standardized benchmark for evaluating the performance of gender identification systems. The Kaggle dataset for text-based gender recognition includes a variety of text samples, such as social media posts, tweets, or blog entries, which are labeled with the author’s gender. The Kaggle data set contains about 20,000 text samples. Each entry includes the text sample and the corresponding gender label (male or female). Participants in Kaggle competitions use these datasets to develop and test gender identification models, providing a competitive environment to improve gender detection algorithms. Both datasets are instrumental in advancing the field of gender identification from text, offering rich, labeled data for model development and evaluation. The PAN 2017 dataset is primarily used in academic and research settings, while the Kaggle dataset is more diverse in content and often employed in practical, competitive environments.

In this study, we aim to identify the gender of the author from the written texts, with a specific focus on literary works such as books and novels.

2.6. The BookSCE Dataset

For this research, we compiled the new dataset (titled BookSCE), mainly collected from books in the Guttenberg Project [?]. The books were annotated by our research group with meta-data and author-related information, including the gender of the author.

The BookSCE dataset contains 8222 unique books dating from the 16th century to the present day, with varying levels of complexity texts, including archaic language, different writing styles, and diverse genres.

For the experiments, the data set was subdivided into a training set containing 6428 unique books (≈80%), a test set containing 897 (≈10%) unique books, and a validation set containing 898 unique books (≈10%).

Table 1 summarizes the BookSCE dataset.

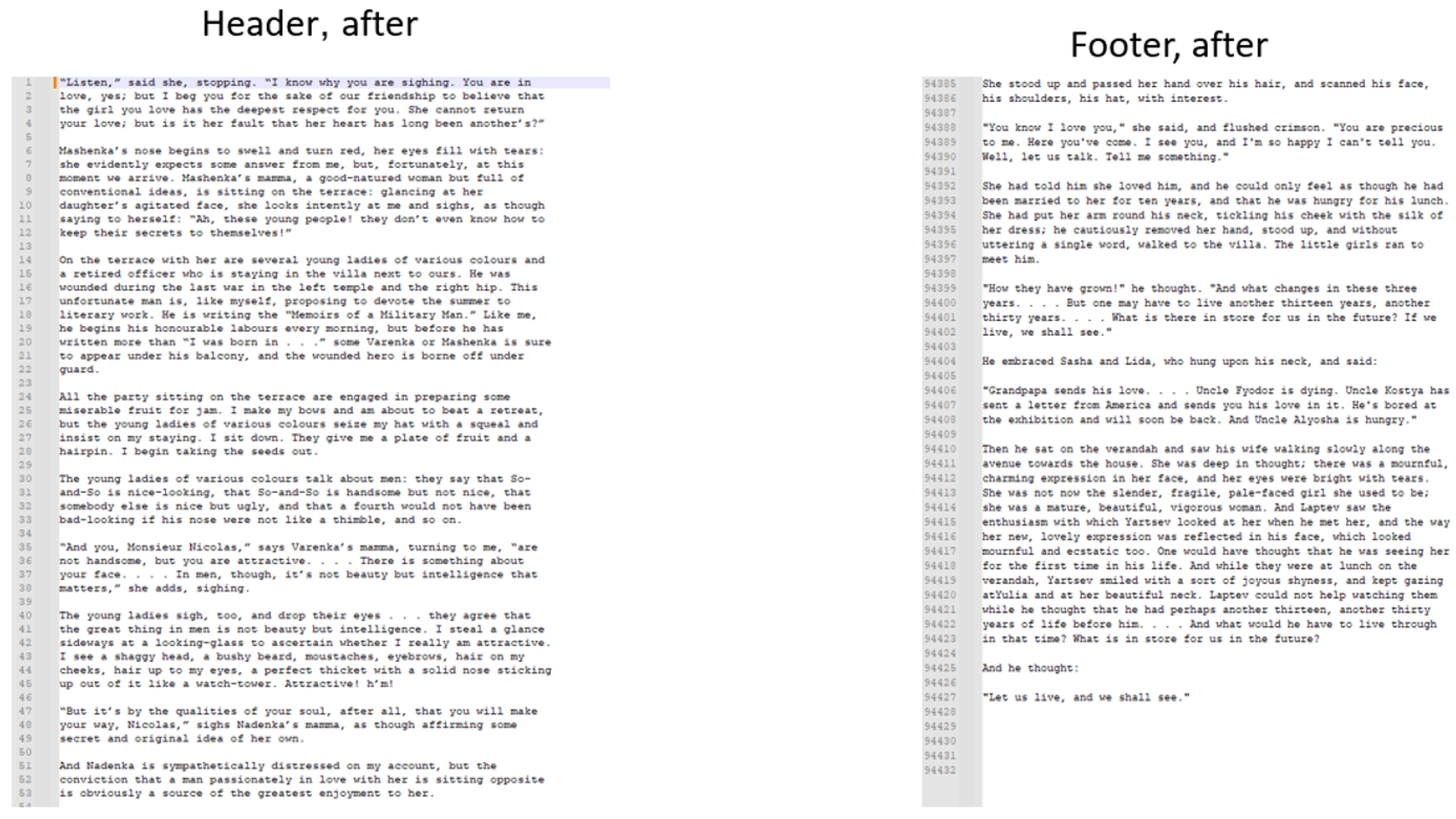

The books were pre-processed as follows. Each book downloaded from the Guttenberg site includes a Gutenberg header and footer. To avoid training our models on the text in the header (our goal is to classify only the text of books), we automatically removed the header and footer. In addition, we removed 10% of the beginning of each book to remove the author’s identification, which is usually mentioned in the first 10% of the book’s text. The samples of the resulting text files are shown in

Figure 1.

2.7. Methodology

We experimented with seven different classifiers. As the baseline, we employed LR [

22] models with different regularization techniques, including L1 and L2 regularization [

23]. Furthermore, we integrated feature selection techniques into our LR models, finding chi-squared (

) [

24] statistics using the SelectKBest method.

In parallel with LR, we explored ensemble methods such as XGBoost [

25], which offer robust performance and scalability. We employed hyperparameter tuning techniques to optimize the performance of the XGBoost model.

To complete the traditional machine learning approaches, we explored the use of SVM [

26], which is particularly well-suited for binary classification.

Recently, transformer-based architectures (aka language models) such as BERT [

11], GPT2 [

27], XLNet [

28], and Robustly optimized BERT approach (RoBERTa) [

29] have significantly advanced natural language processing capabilities. Using the BERT model excels at understanding the context from both directions in a sentence, making it highly effective for tasks like question answering and language inference. The Generative Pre-trained Transformer 2 (GPT2), designed primarily for text generation, performs exceptionally well in creating coherent and contextually relevant text, but its unidirectional approach limits its understanding of full sentence context. XLNet integrates the strengths of both BERT and GPT2 by employing a permutation-based training method, allowing it to capture bidirectional context without the limitations of fixed left-to-right training, making it powerful but computationally intensive. RoBERTa builds on BERT by using more data and longer training periods, resulting in improved performance across various tasks, though at the cost of requiring extensive computational resources. Each model has its strengths: BERT and RoBERTa for comprehension tasks, GPT2 for generation, and XLNet for a balanced approach, with trade-offs in computational demands and task suitability.

All these models leverage pre-trained representations of text data to capture intricate linguistic patterns, providing a robust foundation for gender identification tasks.

We applied all four language models to our data.

2.8. Methodology

We experimented with seven different classifiers. As the baseline, we employed LR [

22] models with different regularization techniques, including L1 and L2 regularization [

23]. Furthermore, we integrated feature selection techniques into our LR models, finding chi-squared (

) [

24] statistics using the SelectKBest method.

In parallel with LR, we explored ensemble methods such as XGBoost [

25], which offer robust performance and scalability. We employed hyperparameter tuning techniques to optimize the performance of the XGBoost model.

To complete the traditional machine learning approaches, we explored the use of SVM [

26], which is particularly well-suited for binary classification.

Recently, transformer-based architectures (aka language models) such as BERT [

11], GPT2 [

27], XLNet [

28], and Robustly optimized BERT approach (RoBERTa) [

29] have significantly advanced natural language processing capabilities. Using the BERT model excels at understanding the context from both directions in a sentence, making it highly effective for tasks like question answering and language inference. The Generative Pre-trained Transformer 2 (GPT2), designed primarily for text generation, performs exceptionally well in creating coherent and contextually relevant text, but its unidirectional approach limits its understanding of full sentence context. XLNet integrates the strengths of both BERT and GPT2 by employing a permutation-based training method, allowing it to capture bidirectional context without the limitations of fixed left-to-right training, making it powerful but computationally intensive. RoBERTa builds on BERT by using more data and longer training periods, resulting in improved performance across various tasks, though at the cost of requiring extensive computational resources. Each model has its strengths: BERT and RoBERTa for comprehension tasks, GPT2 for generation, and XLNet for a balanced approach, with trade-offs in computational demands and task suitability.

All these models leverage pre-trained representations of text data to capture intricate linguistic patterns, providing a robust foundation for gender identification tasks.

We applied all four language models to our data.

3. Experimental Study

The primary purpose of this study is to explore and evaluate various machine learning and deep learning models for the task of gender recognition from book texts. In this context, gender recognition involves identifying the gender of an author of the book. This task presents several challenges due to the nuanced and complex nature of language and the variability in writing styles.

3.1. Experimental Settings

The experiments were conducted using Google Colab with a runtime environment equipped with 32 GB of RAM and a T4 GPU. Python version 3 was utilized for all implementations.

3.1.1. Logistic Regression

The LR models were trained using the a library for the large linear classification, aka a liblinear solver with a maximum of 1000 iterations. The models were evaluated using precision and recall scores. During the experiment, the dataset was split into training and testing sets with a random state value 42. Precision and recall scores were computed for classes ’m’ (male) and ’f’ (female). Each iteration of the model training used 20 books.

Furthermore, we trained the LR classifier with L1 and L2 penalty regularizations using the same evaluation protocol.

3.1.2. Extreme Gradient Boosting Classifier

The Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) model were trained with default parameters for binary classification.

The models were evaluated using accuracy, precision, and recall scores. A confusion matrix and metrics for both classes ’m’ and ’f’ were computed. Each iteration of the model training used 20 books. Additionally, we experimented with an enhanced XGB configuration with specific parameters like gamma, subsample, and colsample bytree.

3.1.3. Support Vector Machine

The SVM models were trained with a linear kernel. An SVM with a linear kernel is used to classify data by finding the hyperplane that best separates different classes in a high-dimensional space. The linear kernel is particularly suited for problems where the classes are linearly separable, meaning they can be separated by a straight line or hyperplane in the feature space.

3.1.4. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers

The BERT model was fine-tuned using the BERTForSequenceClassification model from Hugging Face’s transformers library, using the AdamW optimizer, and a learning rate of 2e-5. The model evaluation included accuracy, precision, and recall scores. Training and testing sets were tokenized using BERTTokenizer.

3.1.5. The Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 2

The GPT2 models were fine-tuned for sequence classification using GPT2ForSequenceClassification from Hugging Face’s transformers library. AdamW optimizer was employed with a learning rate of 5e-5.

3.1.6. XLNet Model

The XLNet model was fine-tuned for sequence classification using XLNetForSequenceClassification from Hugging Face’s transformers library. The AdamW optimizer was used with a learning rate of 5e-5.

3.1.7. RoBERTa

The RoBERTa model was fine-tuned for sequence classification using RoBERTaForSequenceClassification from Hugging Face’s transformers library. The AdamW optimizer was utilized with a learning rate of 5e-5.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

We experimented with the seven architectures described at the beginning of

Section 3. The training data was batched for efficient processing. All models were trained on 90% of the books’ text (after removing the header and the footer as explained in

Section 2.6).

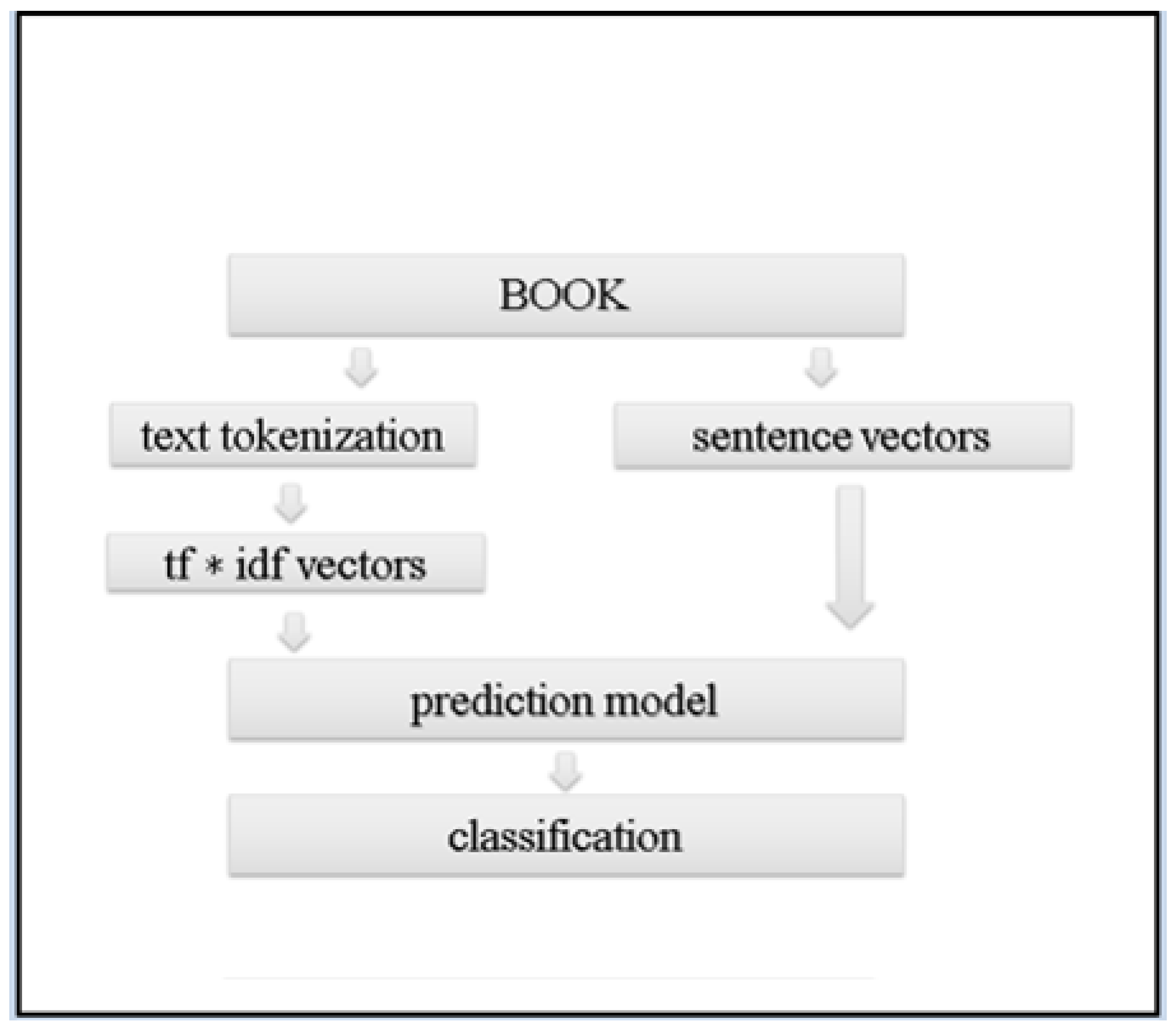

Figure 2 presents the experimental pipeline. We employed different preprocessing and text representation depending on the specific model being used. For LR, XGB, and SVM (left side of the flowchart), the process involved tokenization, converting the input texts into Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectors, and then feeding these vectors into the respective prediction models to train and make predictions.

For transformer-based models BERT, GPT2, XLNet, and RoBERTa (right side of the flowchart), the books were processed to create sentence vectors, which are rich and context-aware representations of the text. For obtaining the sentence vectors and performing the classification tasks, the Hugging Face transformer library was used for all models. The tokenized text is passed through each model: BERT uses the embedding of the [CLS] token, GPT2 uses the final hidden state, XLNet utilizes the embeddings of the final hidden state, and RoBERTa uses the initial special token’s embedding as the sentence vector. These sentence vectors were then fed into the respective transformer models, which subsequently classified the author’s gender based on the features extracted from the sentence vectors.

In the experiments with the LR, SVM, and XGB, we used CountVectorizer to prepare text data for further processing by creating a vocabulary of words. In the experiments with the BERT, GPT2, XLNET, and RoBERTa, we utilized a self-tokenizer. The model was trained on the extracted feature vectors (tokenized or CountVectorizer), using corresponding ground truth labels.

During the training of BERT, GPT2, XLNET, and RoBERTa, we used AdamW [

30,

31] optimizer.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the experiments on the BookSCE dataset. In all the experiments, we followed the settings described in

Section 3.1.

The results are reported in

Table 2. We calculated the overall classification accuracy, the average Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1-score, as well as the Precision, Recall, and F1-score for each class separately (denoted with subscripts ’

m’ and ’

f’ for male and female, respectively). The Acc column of

Table 2 contains the average classification accuracy results for all models on the BookSCE dataset. As can be seen, GPT2 provided the best overall accuracy of 0.925, and XLNet followed with the second-best accuracy score of 0.907

The GPT2 model achieved an impressive accuracy of 0.925 and precision scores of 0.944 for males and 0.851 for females. This model’s success can be attributed to its generative and autoregressive training, which enhances its ability to interpret contextual information. The high performance of GPT2 in binary classification tasks highlights its strong contextual understanding and precise prediction capabilities.

The XLNet model also performed well, with an accuracy of 0.907 and precision scores of 0.931 for males and 0.806 for females. The XLNet’s architecture, which includes autoregressive and permutation-based training, enables it to excel in capturing complex patterns and dependencies in the text. This contributes to its high performance, making it a strong contender in binary classification tasks.

At the bottom of the performance table, BERT and RoBERTa showed significantly lower accuracies of 0.739 and 0.711, respectively. The relatively poor performance of these models may be due to their different architectural designs and the way they handle textual data. The high versatility and variability in book texts can pose a challenge for these models, making it harder to capture consistent patterns, especially when dealing with the nuanced language found in literature.

Interestingly, the simpler LR model demonstrated comparable performance, achieving an overall accuracy of 0.837 and even outperforming some of the more complex models like BERT and RoBERTa. The LR model precision for males was 0.886, and for females it was 0.605. This phenomenon can be explained by the unique nature of book texts, which may exhibit more straightforward correlations between features and the target variable, making simpler models like LR surprisingly effective. Furthermore, adding regularization of L2 marginally improved the accuracy of LR to 0.841, highlighting the impact of regularization techniques on model performance. In summary, the results indicate that sophisticated models like GPT2 and XLNet are particularly well-suited for the binary classification task on the BookSCE dataset, likely due to their advanced architectures and training methods.

5. Case Study

To assess the ability of our classifiers to identify female authors who wrote under male pen names, we conducted an experiment using 12 books from the BookSCE dataset. These books were authored by females using male pseudonyms and are listed in

Table 3. For this experiment, we used a different data split: the training set included all books from the BookSCE dataset except those listed in

Table 3, while the test set comprised only the books listed in

Table 3. For the experiment, we applied three classifiers: GPT2, XLNet and LR. The results showed that GPT2 achieved an accuracy of 0.833, with XLNet accuracy of 0.750. However, the LR model did not perform well for this task, achieving only 0.333 (

Table 3). It is worth noting that "Middlemarch" complex and deeply layered novel, renowned for its exploration of social, political, and personal issues in 19th-century England. George Eliot’s narrative style in this book is intricate, with a focus on psychological depth and realism, which might mirror the writing styles of male authors of the time, which may explain why female recognition was more challenging. "Daniel Deronda" focuses heavily on a male character, making it somewhat difficult for classifiers to correctly identify the author’s gender. Additionally, "Impressions of Theophrastus Such" contains numerous short stories, which complicates the task of gender identification as female author book.

6. Discussion and Future Work

One key finding of our study is the ability to identify an author’s gender, which can be used to explore gender dynamics in literature. By examining how gender identity and expression impact literary themes, writing styles, and narrative tactics, scholars can gain insight into the experiences and viewpoints of both male and female authors. For instance, novels written by women may highlight issues like relationships, identity, and societal expectations, while those written by men may focus on power, masculinity, and societal hierarchy. This critical examination can reveal the intricate relationship between gender, creativity, and cultural creation in literature, as well as how gendered symbols, motifs, and tropes represent wider cultural views on gender and identity.

In future work, we plan to expand the dataset by adding more books written by female authors to improve model performance and fairness. Techniques like grid search [

32], random search [

33], and Bayesian optimization [

34] will be used to optimize hyperparameters. Developing novel techniques for mitigating biases and improving model generalization is essential to ensure the fairness and reliability of gender prediction models. This might involve fairness-aware training objectives and adversarial training methods.

Additionally, incorporating advanced models such as GPT-4 [

35], T5 [

36], and Large Language Models (LLMs) [

37] like Llama 2 [

38] could enhance prediction accuracy and generalization. Fine-tuning these models on gender prediction tasks can take advantage of their rich linguistic representations and contextual understanding to improve performance.

7. Conclusions

The objective of this study is to classify the gender of the author based on the text of the author’s books. For this research, we compiled the BookSCE dataset, collected primarily from books in the Gutenberg Project. The books were annotated by our research group with meta-data and author-related information, including the gender of the author. The BookSCE dataset contains 8222 unique books dating from the 16th century to the present day, with varying levels of complexity, including archaic language, different writing styles, and diverse genres. We believe that the compiled dataset will be valuable for the research community, providing a robust foundation to advance studies and driving further developments in this field. Additionally, the dataset will be valuable for various tasks, e.g., automatic text dating, and it includes a range of annotations beyond gender annotation. The dataset been utilized in the CoLiE: Automatic Classification of Literary Epochs competition [

39] to predict the literary epoch in which the text was written.

We conducted extensive experiments on binary author gender classification using several models: LR, XGBClassifier, SVM, BERT, GPT2, XLNet, and RoBERTa.

The best results were achieved by the GPT2 model, with an overall accuracy of 0.925 and an F1 score of 0.885. The XLNet followed, with second-best scores, including an overall score of 0.907 and an average F1 score of 0.856. The LR model, known for its straightforward and understandable nature, not only provided good results but also demonstrated its effectiveness in book author gender classification. This highlights its suitability for scenarios requiring transparency and simplicity. Additionally, it remains a viable option in resource-constrained environments.

In future research, we plan to focus on enhancing gender prediction models by incorporating advanced techniques and models such as GPT-4, T5, and other LLMs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.Y., M.L., and I.R.; methodology, M.L., and I.R.; software, V.Y.; validation, V.Y.; formal analysis, V.Y., M.L., and I.R..; investigation, V.Y., M.L., and I.R.; resources, V.Y., M.L., and I.R.; writing—original draft preparation, V.Y.; writing—V.Y., M.L., and I.R.; supervision, M.L., and I.R.; project administration, M.L., and I.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sand, G. Indiana; None, Chicago Review Press, Incorporated, 2000.

- Sand, G. Valentine; Chicago Review Press, 2005.

- Lee, V. The Tower of the Mirrors and Other Essays on the Spirit of Places (1914). By: Vernon Lee: Vernon Lee Was the Pseudonym of the British Writer Violet Paget (14 October 1856 - 13 February 1935).; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017.

- Paget, V. A phantom lover, by Vernon Lee; IndyPublish. com, 1886.

- Tiptree, J. Her Smoke Rose Up Forever; S.F. MASTERWORKS, Orion, 2014.

- Tiptree, J. The Starry Rift; Orion, 2015.

- Boyd, R.L.; Ashokkumar, A.; Seraj, S.; Pennebaker, J.W., Eds. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC-22; This article is published by LIWC.net, Austin, Texas 78703 USA in conjunction with the LIWC2022 software program.: New York, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bamman, D.; Smith, N.A. Unsupervised Discovery of Biographical Structure from Text. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2 2014, pp. 363–375. [CrossRef]

- Bsir, B.; Zrigui, M. Bidirectional LSTM for Author GenderIdentification. 10th International Conference, ICCCI 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Ke, Z.; Cui, J.; Yu, H.; Liu, G. The construction of Chinese microblog gender-specific thesauruses and user gender classification. Applied Network Science 2018, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.04577 2019, [arXiv:cs.CL/1810.04805]. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Chandramouli, R.; Subbalakshmi, K. Author gender identification from text. Digital Investigation 2011, 8, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Chen, X.; Chandramouli, R.; Subbalakshmi, K. Gender Identification from E-mails. 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Data Mining, 2009, pp. 154 – 158. [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, A.; Hovy, D.; Søgaard, A. Cross-lingual syntactic variation over age and gender. Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning 2015, pp. 104–110. [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.; Shepherd, S.; Jones, K.; Hassan, L. Toward an Ethical Framework for the Text Mining of Social Media for Health Research: A Systematic Review. Sec. Health Informatics Volume 2 - 2020 2021, [2020.592237]. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Verma, A.K.; Mukherjee, A. Auditing Gender Analyzers on Text Data. Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; p. 108–115. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenberg, P.; Figueroa, A.R. Textual Pre-Trained Models for Gender Identification Across Community Question-Answering Members. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 3983–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Thorp, J.; Ainslie, J.; Eckstein, I.; Ontanon, S. FNet: Mixing Tokens with Fourier Transforms, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CL/2105.03824]. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yu, H.; Song, X.; Liu, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, D. MobileBERT: a Compact Task-Agnostic BERT for Resource-Limited Devices, 2020, [arXiv:cs.CL/2004.02984]. [CrossRef]

- PAN. Author Profiling. 2017. Available online: https://pan.webis.de/clef17/pan17-web/author-profiling.html. [CrossRef]

- Pritom, R.R. Gender Recognition Dataset. 2021. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rashikrahmanpritom/gender-recognition-dataset.

- Bisong, E., Ed. Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform; Apress Berkeley, CA: OTTAWA, ON, Canada, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Demir-Kavuk, O.; Akutsu, M.K.T.; Knapp, E.W. Prediction using step-wise L1, L2 regularization and feature selection for small data sets with large number of features. 2011 10th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications 2011. [CrossRef]

- Oakes, M.; Gaizauskas, R.; Fowkes, H. A Method Based on the Chi-Square Test for Document Classification. TConference: SIGIR 2001: Proceedings of the 24th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, September 9-13, 2001, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA 2001.

- Bentéjac, C.; Csörgő, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, G. A Comparative Analysis of XGBoost. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid November 2019. [CrossRef]

- CORTES, C.; VAPNIK, V. Support-Vector Networks. 1995 Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston. Manufactured in The Netherlands. 1995. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; others. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9.

- Yang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Le, Q.V. XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.08237 2019, [arXiv:cs.CL/1907.11692]. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Duand, J.; Joshi†, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 2020, [arXiv:cs.CL/1906.08237]. [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. (No Title) 2017, [arXiv:cs.LG/1412.6980]. [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101 2019, [arXiv:cs.LG/1711.05101]. [CrossRef]

- Pontes, F.; Amorim, G.; Balestrassi, P.; Paiva, A.; Ferreira, J. Design of experiments and focused grid search for neural network parameter optimization. Neurocomputing 2016, 186, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random Search for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research 13 2012.

- Garrido-Merchán, E.C.; Gozalo-Brizuela, R.; González-Carvajal, S. Comparing BERT against Traditional Machine Learning Models in Text Classification. Journal of Computational and Cognitive Engineering 2023, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI.; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; Avila, R.; Babuschkin, I.; Balaji, S.; Balcom, V.; Baltescu, P.; Bao, H.; Bavarian, M.; Belgum, J.; Bello, I.; Berdine, J.; Bernadett-Shapiro, G.; Berner, C.; Bogdonoff, L.; Boiko, O.; Boyd, M.; Brakman, A.L.; Brockman, G.; Brooks, T.; Brundage, M.; Button, K.; Cai, T.; Campbell, R.; Cann, A.; Carey, B.; Carlson, C.; Carmichael, R.; Chan, B.; Chang, C.; Chantzis, F.; Chen, D.; Chen, S.; Chen, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Chess, B.; Cho, C.; Chu, C.; Chung, H.W.; Cummings, D.; Currier, J.; Dai, Y.; Decareaux, C.; Degry, T.; Deutsch, N.; Deville, D.; Dhar, A.; Dohan, D.; Dowling, S.; Dunning, S.; Ecoffet, A.; Eleti, A.; Eloundou, T.; Farhi, D.; Fedus, L.; Felix, N.; Fishman, S.P.; Forte, J.; Fulford, I.; Gao, L.; Georges, E.; Gibson, C.; Goel, V.; Gogineni, T.; Goh, G.; Gontijo-Lopes, R.; Gordon, J.; Grafstein, M.; Gray, S.; Greene, R.; Gross, J.; Gu, S.S.; Guo, Y.; Hallacy, C.; Han, J.; Harris, J.; He, Y.; Heaton, M.; Heidecke, J.; Hesse, C.; Hickey, A.; Hickey, W.; Hoeschele, P.; Houghton, B.; Hsu, K.; Hu, S.; Hu, X.; Huizinga, J.; Jain, S.; Jain, S.; Jang, J.; Jiang, A.; Jiang, R.; Jin, H.; Jin, D.; Jomoto, S.; Jonn, B.; Jun, H.; Kaftan, T.; Łukasz Kaiser.; Kamali, A.; Kanitscheider, I.; Keskar, N.S.; Khan, T.; Kilpatrick, L.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, C.; Kim, Y.; Kirchner, J.H.; Kiros, J.; Knight, M.; Kokotajlo, D.; Łukasz Kondraciuk.; Kondrich, A.; Konstantinidis, A.; Kosic, K.; Krueger, G.; Kuo, V.; Lampe, M.; Lan, I.; Lee, T.; Leike, J.; Leung, J.; Levy, D.; Li, C.M.; Lim, R.; Lin, M.; Lin, S.; Litwin, M.; Lopez, T.; Lowe, R.; Lue, P.; Makanju, A.; Malfacini, K.; Manning, S.; Markov, T.; Markovski, Y.; Martin, B.; Mayer, K.; Mayne, A.; McGrew, B.; McKinney, S.M.; McLeavey, C.; McMillan, P.; McNeil, J.; Medina, D.; Mehta, A.; Menick, J.; Metz, L.; Mishchenko, A.; Mishkin, P.; Monaco, V.; Morikawa, E.; Mossing, D.; Mu, T.; Murati, M.; Murk, O.; Mély, D.; Nair, A.; Nakano, R.; Nayak, R.; Neelakantan, A.; Ngo, R.; Noh, H.; Ouyang, L.; O’Keefe, C.; Pachocki, J.; Paino, A.; Palermo, J.; Pantuliano, A.; Parascandolo, G.; Parish, J.; Parparita, E.; Passos, A.; Pavlov, M.; Peng, A.; Perelman, A.; de Avila Belbute Peres, F.; Petrov, M.; de Oliveira Pinto, H.P.; Michael.; Pokorny.; Pokrass, M.; Pong, V.H.; Powell, T.; Power, A.; Power, B.; Proehl, E.; Puri, R.; Radford, A.; Rae, J.; Ramesh, A.; Raymond, C.; Real, F.; Rimbach, K.; Ross, C.; Rotsted, B.; Roussez, H.; Ryder, N.; Saltarelli, M.; Sanders, T.; Santurkar, S.; Sastry, G.; Schmidt, H.; Schnurr, D.; Schulman, J.; Selsam, D.; Sheppard, K.; Sherbakov, T.; Shieh, J.; Shoker, S.; Shyam, P.; Sidor, S.; Sigler, E.; Simens, M.; Sitkin, J.; Slama, K.; Sohl, I.; Sokolowsky, B.; Song, Y.; Staudacher, N.; Such, F.P.; Summers, N.; Sutskever, I.; Tang, J.; Tezak, N.; Thompson, M.B.; Tillet, P.; Tootoonchian, A.; Tseng, E.; Tuggle, P.; Turley, N.; Tworek, J.; Uribe, J.F.C.; Vallone, A.; Vijayvergiya, A.; Voss, C.; Wainwright, C.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, A.; Wang, B.; Ward, J.; Wei, J.; Weinmann, C.; Welihinda, A.; Welinder, P.; Weng, J.; Weng, L.; Wiethoff, M.; Willner, D.; Winter, C.; Wolrich, S.; Wong, H.; Workman, L.; Wu, S.; Wu, J.; Wu, M.; Xiao, K.; Xu, T.; Yoo, S.; Yu, K.; Yuan, Q.; Zaremba, W.; Zellers, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, T.; Zhuang, J.; Zhuk, W.; Zoph, B. GPT-4 Technical Report, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2303.08774]. [CrossRef]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer, 2023, [arXiv:cs.LG/1910.10683]. [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J. A Review of Transformer Models, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; Bikel, D.; Blecher, L.; Ferrer, C.C.; Chen, M.; Cucurull, G.; Esiobu, D.; Fernandes, J.; Fu, J.; Fu, W.; Fuller, B.; Gao, C.; Goswami, V.; Goyal, N.; Hartshorn, A.; Hosseini, S.; Hou, R.; Inan, H.; Kardas, M.; Kerkez, V.; Khabsa, M.; Kloumann, I.; Korenev, A.; Koura, P.S.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lavril, T.; Lee, J.; Liskovich, D.; Lu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Martinet, X.; Mihaylov, T.; Mishra, P.; Molybog, I.; Nie, Y.; Poulton, A.; Reizenstein, J.; Rungta, R.; Saladi, K.; Schelten, A.; Silva, R.; Smith, E.M.; Subramanian, R.; Tan, X.E.; Tang, B.; Taylor, R.; Williams, A.; Kuan, J.X.; Xu, P.; Yan, Z.; Zarov, I.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, A.; Kambadur, M.; Narang, S.; Rodriguez, A.; Stojnic, R.; Edunov, S.; Scialom, T. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2307.09288]. [CrossRef]

- Rabaev, I.; Litvak, M.; Younkin, V.; Campos, R.; Jorge, A.M.; Jatowt, A. The Competition on Automatic Classification of Literary Epochs, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).