Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Leaf Litter

2. Factors Affecting the Leaf Litter Decomposition Process

3. Role of Saprobes in Leaf Litter Decomposition and Nutrient Recycling

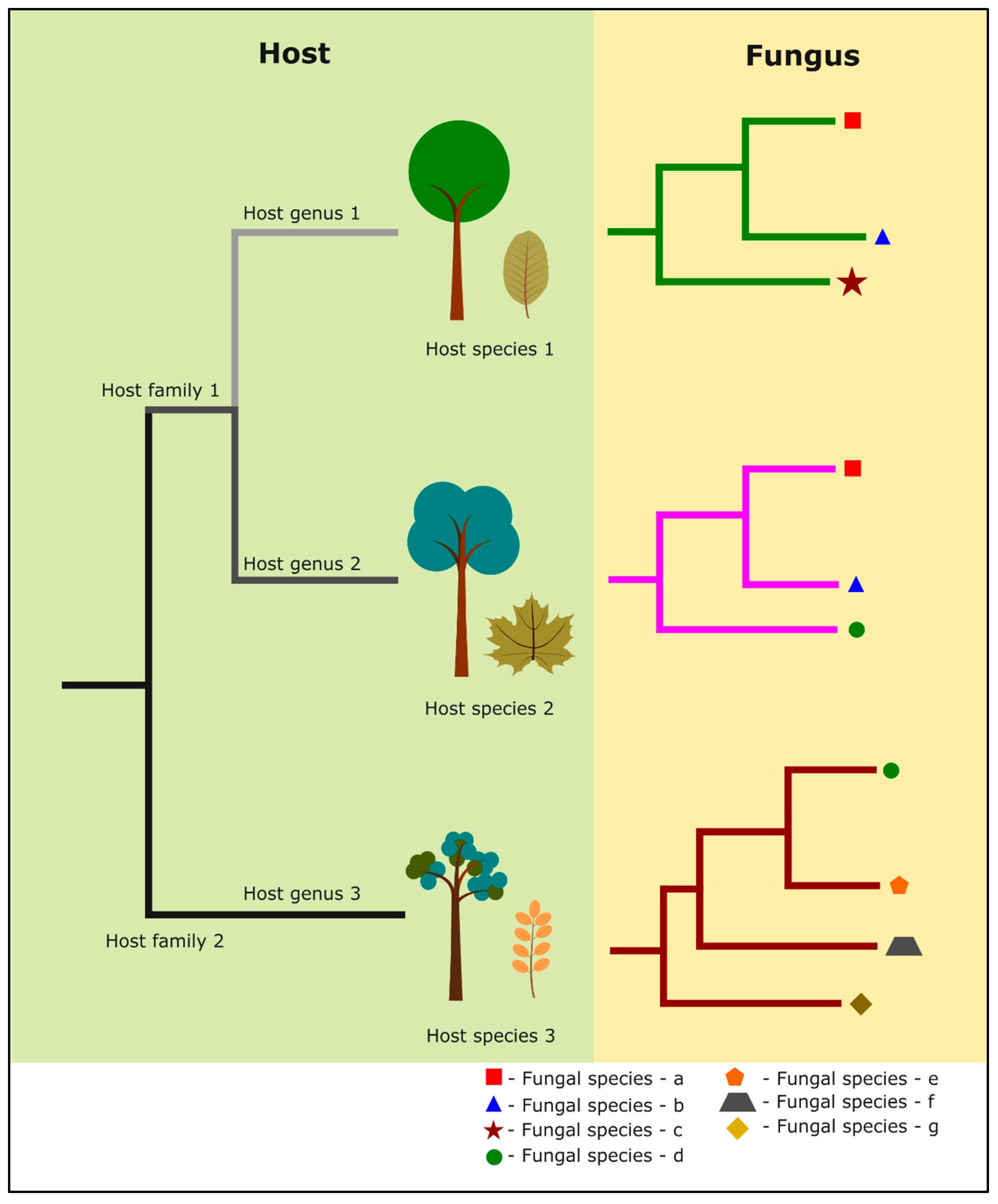

4. Host-Specificity, -Recurrence and -Preference

5. Global Scenario of Leaf Litter-Inhabiting Microfungi

6. Methods of Studying Leaf Litter Inhabiting Microfungi

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, E.A.; Catley, K.M.; Wynne, P.J. Life in the Leaf Litter; American Museum of Natural History,: New York, USA, 2002; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, K.K.; Pyasi, A.V.R. Litter Decomposing Fungi in Sal (Shorea Robusta) Forests of Central India. Nusant. Biosci. 2011, 3, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, D.; Gentekaki, E.; Jeewon, R.; Kuo, C.H.; Promputtha, I.; Hyde, K.D. Life in Leaf Litter: Fungal Community Succession during Decomposition. Mycosphere 2021, 12, 406–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burges, N.A. Microorganism in the Soil; Hutchinson University Library,: Hutchinson, London, 1958; pp. 1–188. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, G.P.; Paul, E. Decomposition and Soil Organic Matter Dynamics. In Methods of ecosystem science; Sala, O.E.; Jackson, R.B.; Mooney, H.A.; Howarth, R., Ed.; Springer, New York, 1999; pp 104–116.

- Hossain, M.; Siddique, M.R.H.; Rahman, M.S.; Hossain, M.Z.; Hasan, M. Nutrient Dynamics Associated with Leaf Litter Decomposition of Three Agroforestry Tree Species (Azadirachta Indica, Dalbergia Sissoo, and Melia Azedarach) of Bangladesh. J. For. Res. 2011, 22, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani, A.; Pioli, S.; Ventura, M.; Panzacchi, P.; Borruso, L.; Tognetti, R.; Tonon, G.; Brusetti, L. The Role of Microbial Community in the Decomposition of Leaf Litter and Deadwood. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 126, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.A.; Covich, A.P.; Finlay, B.J.; Gilbert, J.; Hyde, K.D.; Johnson, R.K.; Kairesala, T.; Lake, P.S.; Lovell, C.R.; Naiman, R.J.; et al. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Processes in Freshwater Sediments. Ambio 1997, 26, 571–577. [Google Scholar]

- Abelho, M. From Litterfall to Breakdown in Streams: A Review. Scientific World Journal. 2001, 1, 656–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H.; Siddique, M.R.H.; Abdullah, S.M.R. Nutrient Dynamics Associated with Leaching and Microbial Decomposition of Four Abundant Mangrove Species Leaf Litter of the Sundarbans, Bangladesh. Wetlands 2014, 34, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Fryar, S.; Tian, Q.; Bahkali, A.H.; Xu, J. Lignicolous Freshwater Fungi along a North-South Latitudinal Gradient in the Asian/Australian Region; Can We Predict the Impact of Global Warming on Biodiversity and Function? Fungal Ecol. 2016, 19, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvadias, V.A.; Alifragis, D.; Tsiontsis, A.; Brofas, G.; Stamatellos, G. Litterfall, Litter Accumulation and Litter Decomposition Rates in Four Forest Ecosystems in Northern Greece. For. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 144, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Trofymow, J.A.; Jackson, R.B.; Porporato, A. Stoichiometric Controls on Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Dynamics in Decomposing Litter. Ecol. Monogr. 2010, 80, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.; Blevins, L.; Staley, C.L. Effects of Clear-Cutting on Decomposition Rates of Litter and Forest Floor in Forests of British Columbia. Can. J. For. Res. 2000, 30, 1751–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.; Zabek, L.; Staley, C.L.; Kabzems, R. Decomposition of Broadleaf and Needle Litter in Forests of British Columbia: Influences of Litter Type, Forest Type, and Litter Mixtures. Can. J. For. Res. 2000, 30, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, E.J. Using Experimental Manipulation to Assess the Roles of Leaf Litter in the Functioning of Forest Ecosystems. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2006, 81, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.M. The Distribution of Leaf Litter Invertebrates along a Neotropical Altitudinal Gradient. J. Trop. Ecol. 1994, 10, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, M.A. The Role of Invertebrates on Leaf Litter Decomposition in Streams. Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 2001, 86, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, H.L.; Laurance, W. Influence of Habitat, Litter Type, and Soil Invertebrates on Leaf-Litter Decomposition in a Fragmented Amazonian Landscape. Oecologia 2005, 144, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghouts, T.; Ernsting, G.; Korthals, G.D.; Vries, T. Litter Fall, Leaf Litter Decomposition and Litter Invertebrates in Primary and Selectively Logged Dipterocarp Forest in Sabah, Malaysia. Philos. Trans. Biol. Sci. 1992, 335, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvet, E.; Giani, N.; Gessner, M. Breakdown and Invertebrate Colonization of Leaf Litter in Two Contrasting Streams, Significance of Oligochaetes in a Large River. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1993, 50, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J.; Weir, I.; Bonnett, S.M.; Maxfield, P.; Ellwood, F. The Relative Importance of Invertebrate and Microbial Decomposition in a Rainforest Restoration Project. Restor. Ecol. 2018, 26, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Bhattacharjya, S.; Mandal, A.; Thakur, J.K.; Atoliya, N.; Sahu, N.; Patra, A. Microbes: A Sustainable Approach for Enhancing Nutrient Availability in Agricultural Soils. Role of Rhizospheric Microbes in Soil. Nutr. Manag. Crop Improv. 2018, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkamp, M. Environmental Effects on Microbial Turnover of Some Mineral Elements. Part II- Biotic Factors. In Soil Biology Biochem; 1969; pp 178–184.

- Hyde, K.D.; Bussaban, B.; Paulus, B.; Crous, P.; Lee, S.; Mckenzie, E.; Nuangmek, W.; Lumyong, S. Diversity of Saprobic Microfungi. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, F.; Leduc, V.; Viotti, C.; Gill, A.; Morin, E.; Reichard, A.; Ziegler-Devin, I.; Zeller, B.; Buée, M. Fungal Communities Mediate but Do Not Control Leaf Litter Chemical Transformation in a Temperate Oak Forest. Plant Soil 2023, 489, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, M.J.; Heal, O.W.; Anderson, M. Decomposition in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 1–272. [Google Scholar]

- Baldrian, P.; Lindahl, B. Decomposition in Forest Ecosystems: After Decades of Research Still Novel Findings. Fungal Ecol. 2011, 4, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tifcakova, L.; Dobiasova, P.; Kolarova, Z.; Koukol, O.; Baldrian, P. Enzyme Activities of Fungi Associated with Picea Abies Needles. Fungal Ecol. 2011, 4, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, D.S.; Kuo, C.-H.; Purahong, W.; Gentekaki, E.; Pumas, C.; Promputtha, I.; Hyde, K.D. Fungal Community Succession on Decomposing Leaf Litter across Five Phylogenetically Related Tree Species in a Subtropical Forest. Fungal Divers. 2022, 115, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankland, J.C. Fungal Succession – Unraveling the Unpredictable. Mycol. Res. 1998, 102, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickie, I.A.; Fukami, T.; Wilkie, J.P.; Allen, R.B.; Buchanan, P.K. Do Assembly History Effects Attenuate from Species to Ecosystem Properties? A Field Test with Wood-inhabiting Fungi. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, B.; Gadek, P.; Hyde, K. Successional Patterns of Microfungi in Fallen Leaves of Ficus Pleurocarpa (Moraceae) in an Australian Tropical Rain Forest 1. Biotropica 2006, 38, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, E. Biological Decomposition of Some Types of Litter from North American Forest. Ecology 1930, 11, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukoura, Z.; Mamolos, A.; Kalburtji, K. Decomposition of Dominant Plant Species Litter in a Semi-Arid Grassland. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2003, 23, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maanen, A.; Debouzie, D.; Gourbiere, F. Distribution of Three Fungi Colonising Fallen Pinus Sylvestris Needles along Altitudinal Transects. Mycol. Res. 2000, 104, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, J.; Demard, J.M.; Bottner, P.J.; Monrozier, J. Decomposition of Mediterranean Leaf Litters: A Microcosm Experiment Investigating Relationships between Decomposition Rates and Litter Quality. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.F.; Sutton, B. Microfungi on Wood and Plant Debris. In Biodiversity of Fungi Inventory and Monitoring Methods; Mueller, G.M., Bills, G.F., Foster, M.S., Ed.; 2004; pp. 217–239. [CrossRef]

- Voriskova, J.; Baldrian, P. Fungal Community on Decomposing Leaf Litter Undergoes Rapid Successional Changes. ISME J. 2013, 7, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, P.K. Litter Decomposition in Tropical Plantation: Impact of Climate and Substrate Quality. Indian For. 1999, 125, 599–608. [Google Scholar]

- Criquet, S.; Farnet, A.; Tagger, S.; Le Petit, J. Annual Variations of Phenoloxidase Activities in an Evergreen Oak Litter: Influence of Certain Biotic and Abiotic Factors. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioretto, A.; Papa, S.; Curcio, E.; Sorrentino, G.; Fuggi, A. Enzyme Dynamics on Decomposing Leaf Litter of Cistus Incanus and Myrtus Communis in a Mediterranean Ecosystem. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioretto, A.; Papa, S.; Sorrentino, G.; Fuggi, A. Decomposition of Cistus Incanus Leaf Litter in a Mediterranean Maquis Ecosystem: Mass Loss, Microbial Enzyme Activities and Nutrient Changes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Aceves, M.; Vera-Aguilar, E.; Bernal, M. Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralization in Soil Amended with Phenanthrene, Anthracene and Irradiated Sewage Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 85, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, K.K.; Jamaluddin. Eucalyptus Litter Decomposition in Tropical Dry Deciduous Forest of Madhya Pradesh. Indian For. 1990, 116, 286–291. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Takeda, H.; Azuma, J. Dynamics of Organic-Chemical Components in Leaf Littersduring a 3.5-Year Decomposition. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2000, 36, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissett, J.; Parkinson, D. Long-Term Effects of Fire on the Composition and Activity of the Soil Micro Flora Of a Subalpine Coniferous Forest. Can. J. Bot. 1980, 58, 1704–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.E.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G. The Biogeographical Distribution of Microfungi Associated with Three Palm Species from Tropical and Temperate Habitats. J. Biogeogr. 2000, 27, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsubo, T.; Uchina, M.; Horikoshi, T.; Nakane, K. Comparative Study of the Mass Loss Rate of Moss Litter in Boreal and Subalpine Forests in Relation to Temperature. Ecol. Res. 1997, 12, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Bednorz, F.; Broll, G.; Kätterer, T. Temperature Dependence of Carbon Mineralisation: Conclusions from a Long-Term Incubation of Subalpine Soil Samples. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, M.; Nakatsubo, T.; Kasai, Y.; Nakane, K.; Horikoshi, T. Altitudinal Differences in Organic Matter Mass Loss and Fungal Biomass in a Subalpine Coniferous Forest, Mt. Fuji, Japan. Arctic, Antarct. Alp. Res. 2000, 32, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, G.; Seastedt, T.R. Soil Fauna and Plant Litter Decomposition in Tropical and Subalpine Forests. Ecology, 2001, 82, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osono, T.; To-Anun, C.; Hagiwara, Y.; Hirose, D. Decomposition of Wood, Petiole and Leaf Litter by Xylaria Species from Northern Thailand. Fungal Ecol. 2011, 4, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M. The Breakdown and Decomposition of Sweet Chestnut (Castanea Sativa Mill.) and Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.) Leaf Litter in Two Deciduous Woodland Soils. Oecologia 1973, 12, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hättenschwiler, S.; Vitousek, P.M. The Role of Polyphenols in Terrestrial Ecosystem Nutrient Cycling. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2000, 15, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidorov, V.; Jdanova, M. Volatile Organic Compounds from Leaves Litter. Chemosphere 2002, 48, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, M.; Baerlocher, F.; Gessner, M. Methods to Study Litter Decomposition; A Practical Guide, 2nd ed.; Bärlocher, F., Gessner, M.O., Graça, M.A.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Dordrecht, 2020; pp. 1–581. [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.-C. L.; Zou, X.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chien, H.-J. Plant Litter Decomposition Influenced by Soil Animals and Disturbance in a Subtropical Rainforest of Taiwan. Pedobiologia (Jena). 2005, 49, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purahong, W.; Kapturska, D.; Pecyna, M.J.; Schulz, E.; Schloter, M.; Buscot, F.; Hofrichter, M.; Krüger, D. Influence of Different Forest System Management Practices on Leaf Litter Decomposition Rates, Nutrient Dynamics and the Activity of Ligninolytic Enzymes: A Case Study from Central European Forests. PLoS One 2014, 9, e93700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osono, T. Leaf Litter Decomposition of 12 Tree Species in a Subtropical Forest in Japan. Ecol. Res. 2017, 32, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; Berg, M.P.; Bottner, P.; Box, E.; Breymeyer, A.; de Anta, R.C.; Couteaux, M.; Escudero, A.; Gallardo, A.; Kratz, W.; et al. Litter Mass Loss Rates in Pine Forests of Europe and Eastern United States: Some Relationships with Climate and Litter Quality. Biogeochemistry 1993, 20, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, B.; Purahong, W.; Wubet, T.; Kahl, T.; Bauhus, J.; Arnstadt, T.; Hofrichter, M.; Buscot, F.; Krüger, D. Linking Molecular Deadwood-Inhabiting Fungal Diversity and Community Dynamics to Ecosystem Functions and Processes in Central European Forests. Fungal Divers. 2016, 77, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, N.; Salcedo, I. Variety of Woody Debris as the Factor Influencing Wood-Inhabiting Fungal Richness and Assemblages: Is It a Question of Quantity or Quality? For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 291, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, T.; Peltoniemi, M.; Pennanen, T.; Mäkipää, R. Fungal Community Dynamics in Relation to Substrate Quality of Decaying Norway Spruce (Picea Abies [L.] Karst.) Logs in Boreal Forests. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 81, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, H.J. The Ecology of Fungi on Plant Remains Above the Soil. New Phytol. 1968, 67, 837–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.N. Studies on Litter Inhabiting Fungi in the Chakia Forest of Varanasi. PhD Dissertation, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India., 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Promputtha, I.; Lumyong, S.; Lumyong, P.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Fungal Succession on Senescent Leaves of Manglietia Garrettii in Doi Suthep-Pui National Park, Northern Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2002, 10, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, S.R.; Gutierrez, A.; Treseder, K.K. Changes in Soil Fungal Communities, Extracellular Enzyme Activities, and Litter Decomposition Across a Fire Chronosequence in Alaskan Boreal Forests. Ecosystems 2013, 16, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, V.V.C.; Pointing, S.B.; Hyde, K.D.; Reddy, C.A. Production of Wood Decay Enzymes, Loss of Mass, and Lignin Solubilization in Wood by Diverse Tropical Freshwater Fungi. Microb. Ecol. 2004, 48, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osono, T. Ecology of Ligninolytic Fungi Associated with Leaf Litter Decomposition. Ecol. Res. 2007, 22, 955–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilly, O.; Bartsch, S.; Rosenbrock, P.; Buscot, F.; Munch, J.C. Shifts in Physiological Capabilities of the Microbiota during the Decomposition of Leaf Litter in a Black Alder ( Alnus Glutinosa (Gaertn.) L.) Forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilly, O.; Bloem, J.; Vos, A.; Munch, J.C. Bacterial Diversity in Agricultural Soils during Litter Decomposition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Wubet, T.; Bruelheide, H.; Liang, Y.; Purahong, W.; Buscot, F.; Ma, K. Tree Species Richness and Fungi in Freshly Fallen Leaf Litter: Unique Patterns of Fungal Species Composition and Their Implications for Enzymatic Decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapook, A.; Hyde, K.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Jones, E.B.G.; Bhat, D.J.; Jeewon, R.; Stadler, M.; Samarakoon, M.C.; Malaithong, M.; Tanunchai, B.; et al. Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Contributions to Fungi Associated with the Invasive Weed Chromolaena Odorata (Siam Weed). Fungal Divers. 2020, 101, 1–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, W. de; Folman, L.B.; Summerbell, R.C.; Boddy, L. Living in a Fungal World: Impact of Fungi on Soil Bacterial Niche Development. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B. Litter Decomposition and Organic Matter Turnover in Northern Forest Soils. For. Ecol. Manage. 2000, 133, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; Weimer, P.J.; van Zyl, W.H.; Pretorius, I.S. Microbial Cellulose Utilization: Fundamentals and Biotechnology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 506–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; McClaugherty, C. Plant Litter; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, M.P.; Mohan, M. Litter Decomposition in Forest Ecosystems: A Review. Energy, Ecol. Environ. 2017, 2, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaní, A.M.; Fischer, H.; Mille-Lindblom, C.T.L. Interactions of Bacteria and Fungi on Decomposing Litter: Differential Extracellular Enzyme Activities. Ecology 2006, 87, 2559–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, C.A.S.; Lesline, J.F.; Schwenk, F. Host Preference Correlated with Chlorate Resistance in Macrophomina phaseolina. Plant Dis. 1987, 71, 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, C.; Ulrich, K.; Ward, E.; Werner, A. RAPD-Based Inter- and Intravarietal Classification of Fungi of the Gaeumannomyces-Phialophora Complex. J. Phytopathol. 1999, 147, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Hyde, K.D. Host-Specificity, Host-Exclusivity, and Host-Recurrence in Saprobic Fungi. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.S. Pathogenesis and Host-Parasite Specificity in Plant Diseases. In Experimental and Conceptual Plant Pathology; Gordon & Breach: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- Shivas, R.G.; Hyde, K.D. Biodiversity of Plant Pathogenic Fungi in the Tropics. In Biodiversity of Tropical Microfungi; K. D. Hyde, E., Ed.; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, 1997; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, L.M.; Lumyong, S.; Hyde, K.D. Fungi on Leaf Litter. In Thai Fungal Diversity; Jones, E.B.G., Tanticharoen, M.H.K., Eds.; Biotec Publishing: Pathum Thani, 2004; pp. 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, B.C.; Kanowski, J.; Gadek, P.A.; Hyde, K.D. Diversity and Distribution of Saprobic Microfungi in Leaf Litter of an Australian Tropical Rainforest. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110, 1441–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Abbott, L.; Werner, D.H.R. Plant Surface Microbiology, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1–663. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, M.E.; Lodge, D.J.; Lebow, P. Relationship of Host Recurrence in Fungi to Rates of Tropical Leaf Decomposition. Pedobiologia (Jena). 2005, 49, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunjun, C.S.; Phukhamsakda, C.; Hyde, K.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Saxena, R.K.; Li, Q. Do All Fungi Have Ancestors with Endophytic Lifestyles? Fungal Divers. 2023, 125, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Bussaban, B.; Paulus, B.; Crous, P.W.; Lee, S.; Mckenzie, E.H.C.; Photita, W.; Lumyong, S. Diversity of Saprobic Microfungi. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promputtha, I.; Hyde, K.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Peberdy, J.F.; Lumyong, S. Can Leaf Degrading Enzymes Provide Evidence That Endophytic Fungi Becoming Saprobes? Fungal Divers. 2010, 41, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegrucci, N.; Bucsinszky, A.M.; Arturi, M.; Cabello, M.N. Communities of Anamorphic Fungi on Green Leaves and Leaf Litter of Native Forests of Scutia buxifolia and Celtis tala: Composition, Diversity, Seasonality and Substrate Specificity. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2015, 32, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterseher, M.; Peršoh, D.; Schnittler, M. Leaf-Inhabiting Endophytic Fungi of European Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.) Co-Occur in Leaf Litter but Are Rare on Decaying Wood of the Same Host. Fungal Divers. 2013, 60, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parungao, M.M.; Fryar, S.C.; Hyde, K.D. Diversity of Fungi on Rainforest Litter in North Queensland, Australia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2002, 11, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promputtha, I.; Lumyong, S.; Dhanasekaran, V.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.A. Phylogenetic Evaluation of Whether Endophytes Become Saprotrophs at Host Senescence. Microb. Ecol. 2007, 53, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promputtha, I.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Tennakoon, D.S.; Lumyong, S.; Hyde, K.D. Succession and Natural Occurrence of Saprobic Fungi on Leaves of Magnolia liliifera in a Tropical Forest. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2017, 38, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, D.S.; Kuo, C.-H.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Thambugala, K.M.; Gentekaki, E.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Bhat, D.J.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; de Silva, N.I.; Promputtha, I.; et al. Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Contributions to Celtis formosana, Ficus ampelas, F. septica, Macaranga tanarius and Morus australis Leaf Litter Inhabiting Microfungi. Fungal Divers. 2021, 108, 1–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Alias, S. Biodiversity and Distribution of Fungi Associated with Decomposing Nypa fruticans. Biodivers. Conserv. 2000, 9, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.D.; Hyde, K.D.; Liew, E.C.Y. A Method to Promote Sporulation in Palm Endophytic Fungi. Fungal Divers. 1998, 1, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.D.; Hyde, K.D.; Liew, E.C.Y. Identification of Endophytic Fungi from Livistona chinensis Based on Morphology and rDNA Sequences. New Phytol. 2000, 147, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polishook, J.D.; Bills, G.F.; Lodge, D.J. Microfungi from Decaying Leaves of Two Rain Forest Trees in Puerto Rico. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1996, 17, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osono, T.; Mori, A. Colonization of Japanese Beech Leaves by Phyllosphere Fungi. Mycoscience 2003, 44, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promputtha, I.; Jeewon, R.; Lumyong, S.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Ribosomal DNA Fingerprinting in the Identification of Non-Sporulating Endophytes from Magnolia liliifera (Magnoliaceae). Fungal Divers. 2005, 20, 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, E.H.C.; Buchanan, P.K.; Johnston, P.R. Checklist of Fungi on Nothofagus Species in New Zealand. New Zeal. J. Bot. 2000, 38, 635–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, E.H.C.; Buchanan, P.K.; Johnston, P.R. Fungi on Pohutukawa and Other Metrosideros Species in New Zealand. New Zeal. J. Bot. 1999, 37, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, E.H.C.; Whitton, S.R.; Hyde, K.D. The Pandanaceae - Does It Have a Diverse and Unique Fungal Biota? In Tropical mycology: volume 2, micromycetes; CABI Publishing: UK, 2002; pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, S.R. Microfungi on the Pandanaceae. PhD Thesis, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton, S.R.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Microfungi on the Pandanaceae: Two New Species of Camposporium, and a Key to the Genus. Fungal Divers. 2002, 11, 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton, S.R.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Microfungi on the Pandanaceae: Paraceratocladium seychellarum Sp. Nov. and a Review of the Genus. Fungal Divers. 2001, 7, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, M.K.M.; Hyde, K.D. Diversity of Fungi on Six Species of Gramineae and One Species of Cyperaceae in Hong Kong. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanna, WH.; Hyde, K.D. Fungal Succession on Fronds of Phoenix hanceana in Hong Kong. Fungal Divers. 2002, 10, 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, PW. Taxonomy and Pathology of Cylindrocladium (Calonectria) and Allied Genera.; The American Phytopathological Society: Minnesota, USA, 2002; pp. 1–294. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Pongpanich, K.; Himaman, W.; Arzanlou, M.W.M. Cryptic Speciation and Host Specificity among Mycosphaerella Spp. Occurring on Australian Acacia Species Grown as Exotics in the Tropics. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 457–469. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, P.W.; Verkley, G.J.M.; Groenewald, J.Z. Eucalyptus Microfungi Known from Culture. 1. Cladoriella and Fulvoflamma Genera Nova, with Notes on Some Other Poorly Known Taxa. Stud. Mycol. 2006, 55, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, B.; Gadek, P.; Hyde, K.D. Estimation of Microfungal Diversity in Tropical Rainforest Leaf Litter Using Particle Filtration: The Effects of Leaf Storage and Surface Treatment. Mycol. Res. 2003, 107, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanna Ho, W.H.; Hyde, K.D. Fungal Communities on Decaying Palm Fronds in Australia, Brunei and Hong Kong. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 1458–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Mel’nik, V.; Taylor, J.E.; Crous, P. Diversity of Saprobic Hyphomycetes on Protaceae and Restionaceae. Fungal Divers. 2004, 17, 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bills, G.F.; Polishook, J.D. Microfungi from Decaying Leaves of Heliconia mariae (Heliconiaceae). Brenesia 1994, 41–42, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bills, G.F.; Polishook, J.D. Abundance and Diversity of Microfungi in Leaf Litter of a Lowland Rain Forest in Costa Rica. Mycologia 1994, 86, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, F.H.; Varela, A.; Wright, S. Tropical Forest Litter Decomposition under Seasonal Drought: Nutrient Release, Fungi and Bacteria. Oikos 1994, 70, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, D.J.; Cantrell, S. Fungal Communities in Wet Tropical Forests: Variation in Time and Space. Can. J. Bot. 1995, 73, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, D.J. Factors Related to Diversity of Decomposer Fungi in Tropical Forests. Biodivers. Conserv. 1997, 6, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G. Forest Endophytes: Pattern and Process. Can. J. Bot. 1995, 73, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G.C. Fungal Endophytes in Stems and Leaves: From Latent Pathogen to Mutualistic Symbiont. Ecology 1988, 69, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Lücking, R. Fungal Diversity Revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 Million Species. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lücking, R.; Aime, M.C.; Robbertse, B.; Miller, A.N.; Aoki, T.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Cardinali, G.; Crous, P.W.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Hawksworth, G.D.L.; et al. Fungal Taxonomy and Sequence-Based Nomenclature. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, C.P.; Thirumalai, E.; Govinda Rajulu, M.B.; Thirunavukkarasu, N.; Suryanarayanan, T.S. Ecology and Diversity of Leaf Litter Fungi during Early-Stage Decomposition in a Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest. Fungal Ecol. 2015, 17, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.A.; Gusmão, L.F.P. Characterization Saprobic Fungi on Leaf Litter of Two Species of Trees in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2015, 46, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purahong, W.; Wubet, T.; Lentendu, G.; Schloter, M.; Pecyna, M.J.; Kapturska, D.; Hofrichter, M.; Krüger, D.; Buscot, F. Life in Leaf Litter: Novel Insights into Community Dynamics of Bacteria and Fungi during Litter Decomposition. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 4059–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.M.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Lumyong, S.; Hyde, K.D. Fungal Succession on Senescent Leaves of Castanopsis diversifolia in Doi Suthep-Pui National Park, Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2008, 30, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kodsueb, R.; Mckenzie, E.; Lumyong, S.; Hyde, K.D. Fungal Succession on Woody Litter of Magnolia Liliifera (Magnoliaceae). Fungal Divers. 2008, 30, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Osono, T.; Ishii, Y.; Takeda, H.; Khamyong, S.; Hirose, D.; Tokumasu, S.; Kakishima, M.; Khamyong, T.H.C. Fungal Succession and Lignin Decomposition on Shorea obtusa Leaves in a Tropical Seasonal Forest in Northern Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2009, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Seephueak, P.; Petcharat, V.; Phongpaichit, S. Fungi Associated with Leaf Litter of Para Rubber (Hevea brasiliensis). Mycology 2010, 1, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthi, S.; Vittal, B. Fungi Associated with Decomposing Leaf Litter of Cashew (Anacardium Occidentale). Mycol. An Int. J. Fungal Biol. 2010, 1, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthi, S.; Vittal, B. Biodiversity of Microfungi Associated with Litter of Pavetta indica. Mycosphere 2010, 1, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shanthi, S.; Vittal, B. . Fungal Diversity and the Pattern of Fungal Colonization of Anacardium occidentale Leaf Litter. Mycology, 2012, 3, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, K.; Osono, T.T.H. Fungal Succession and Decomposition of Camellia Japonica Leaf Litter. Ecol. Res. 2005, 20, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubartová, A.; Ranger, J.; Berthelin, J.B.T. Diversity and Decomposing Ability of Saprophytic Fungi from Temperate Forest Litter. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 58, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. The Biodiversity of Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 1411–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Rong, I.H.; Wood, A.; Lee, S.; Glen, H.; Botha, W.; Slippers, B.; de Beer, W.Z.; Wingfield, M.J.; Hyde, K.D. How Many Species of Fungi Are There at the Tip of Africa? Stud. Mycol. 2006, 55, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M. Pestalotioid Fungi from Restionaceae in the Cape Floral Kingdom. Stud. Mycol. 2006, 55, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Chen, Y.-J.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Calabon, M.S.; Jiang, H.-B.; Lin, C.-G.; Norphanphoun, C.; Sysouphanthong, P.; Pem, D.; et al. The Numbers of Fungi: Is the Descriptive Curve Flattening? Fungal Divers. 2020, 103, 219–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukhamsakda, C.; Nilsson, R.H.; Bhunjun, C.S.; de Farias, A.R.G.; Sun, Y.-R.; Wijesinghe, S.N.; Raza, M.; Bao, D.-F.; Lu, L.; Tibpromma, S.; et al. The Numbers of Fungi: Contributions from Traditional Taxonomic Studies and Challenges of Metabarcoding. Fungal Divers. 2022, 114, 327–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunjun, C.S.; Niskanen, T.; Suwannarach, N.; Wannathes, N.; Chen, Y.-J.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Buyck, B.; Zhao, C.-L.; Fan, Y.-G.; et al. The Numbers of Fungi: Are the Most Speciose Genera Truly Diverse? Fungal Divers. 2022, 114, 387–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth, D.L. The Fungal Dimension of Biodiversity: Magnitude, Significance, and Conservation. Mycol. Res. 1991, 95, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Cheng, J.; Wei, G.; Lin, Y. Temporal and Spatial Succession and Dynamics of Soil Fungal Communities in Restored Grassland on the Loess Plateau in China. L. Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 1273–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivelo, S.; Bhatnagar, J.M. An Evolutionary Signal to Fungal Succession during Plant Litter Decay. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senanayake, I.C.; Rathnayaka, A.R.; Marasinghe, D.S.; Calabon, M.S.; Gentekaki, E.; Lee, H.B.; Hurdeal, V.G.; Pem, D.; Dissanayake, L.S.; Wijesinghe, S.N.; Bundhun, D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Goonasekara, I.D.; et al. Morphological Approaches in Studying Fungi: Collection, Examination, Isolation, Sporulation and Preservation. Mycosphere 2020, 11, 2678–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.Q.; Hyde, K.D. Fungal Succession on Bamboo in Hong Kong. Fungal Divers. 2002, 10, 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Samaradiwakara, N.P.; de Farias, A.R.G.; Tennakoon, D.S.; Aluthmuhandiram, J.V.S.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Kumla, J.; Lumyong, S. Appendage-Bearing Sordariomycetes from Dipterocarpus alatus Leaf Litter in Thailand. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaradiwakara, N.P.; Gomes de Farias, A.R.; Tennakoon, D.S.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Hyde, K.D.; Lumyong, S. Sexual Morph of Allophoma tropica and Didymella coffeae-arabicae (Didymellaceae, Pleosporales, Dothidiomycetes), Including Novel Host Records from Leaf Litter in Thailand. New Zeal. J. Bot. 2024, 62, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, A.J.; Purahong, W.; Wubet, T.; Hyde, K.D.; Zhang, W.; Xu, H.; Zhang, G.; Fu, C.; Liu, M.; Xing, Q.; et al. Direct Comparison of Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Molecular Approaches Reveal the Diversity of Fungal Endophytic Communities in Stems of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera). Fungal Divers. 2018, 90, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayawardene, N.; Boonyuen, N.; Ranaweera, C.; de Zoysa, H.; Padmathilake, R.; Nifla, F.; Dai, D.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; et al. OMICS and Other Advanced Technologies in Mycological Applications. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, G.M.; Bills, G.F.; Foster, M. Biodiversity of Fungi: Inventory and Monitoring Methods.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, 2004; pp. 1–777. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, L.H.S.; Peixoto-Nogueira, S.C.; Michelin, M.; Rizzatti, A.C.S.; Sandrim, V.C.; Zanoelo, F.F.; Aquino, A.C.M.M.; Junior, A.B.; Polizeli, M. de L.T.M. Screening of Filamentous Fungi for Production of Enzymes of Biotechnological Interest. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2006, 37, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, J.; Platas, G.; Paulus, B.; Bills, G.F. High-Throughput Culturing of Fungi from Plant Litter by a Dilution-to-Extinction Technique. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 60, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeewon, R.; Hyde, K.D. Detection and Diversity of Fungi from Environmental Samples: Traditional Versus Molecular Approaches; 2007; pp 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Kaewchai, S.; Soytong, K.; Hyde, K.D. Mycofungicides and Fungal Biofertilizers. Fungal Divers. 2009, 38, 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dorhout, D.L.; Sappington, T.W.; Lewis, L.C.; Rice, M.E. Flight Behaviour of European Corn Borer Infected with Nosema pyrausta. J. Appl. Entomol. 2011, 135, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Zhang, R.; Xue, C.; Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Shen, Q. Application of Bio-Organic Fertilizer Can Control Fusarium Wilt of Cucumber Plants by Regulating Microbial Community of Rhizosphere Soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2012, 48, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Pointing, S.B. Comparison of DNA and RNA, and Cultivation Approaches for the Recovery of Terrestrial and Aquatic Fungi from Environmental Samples. Curr. Microbiol. 2013, 66, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Puusepp, R.; Nilsson, R.H.; James, T.Y. Novel Soil-Inhabiting Clades Fill Gaps in the Fungal Tree of Life. Microbiome 2017, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aime, M.C.; Miller, A.N.; Aoki, T.; Bensch, K.; Cai, L.; Crous, P.W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Hyde, K.D.; Kirk, P.M.; Lücking, R.; et al. Schoch How to Publish a New Fungal Species, or Name, Version 3.0. IMA Fungus 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeewon, R.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Rampadaruth, S.; Puchooa, D.; Li-Gang, Z.; AiRong, L.; Hong-Kai, W. Nomenclatural and Identification Pitfalls of Endophytic Mycota Based on DNA Sequence Analyses of Ribosomal and Protein Genes Phylogenetic Markers: A Taxonomic Dead End? Mycosphere 2017, 8, 1802–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, M.V. Metabarcoding and Metagenomics in Soil Ecology Research: Achievements, Challenges, and Prospects. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2021, 11, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutleben, J.; Chaib De Mares, M.; van Elsas, J.D.; Smidt, H.; Overmann, J.; Sipkema, D. The Multi-Omics Promise in Context: From Sequence to Microbial Isolate. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, H.E.; Parrent, J.L.; Jackson, J.A.; Moncalvo, J.-M.; Vilgalys, R. Fungal Community Analysis by Large-Scale Sequencing of Environmental Samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5544–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalhais, L.C.; Dennis, P.G.; Tyson, G.W.; Schenk, P.M. Application of Metatranscriptomics to Soil Environments. J. Microbiol. Methods 2012, 91, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, P.-A.; Bálint, M.; Greshake, B.; Bandow, C.; Römbke, J.; Schmitt, I. Illumina Metabarcoding of a Soil Fungal Community. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 65, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, H.A.; Miller, A.N.; Pearce, C.J.; Oberlies, N.H. Fungal Identification Using Molecular Tools: A Primer for the Natural Products Research Community. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, N.; Shanmugam, H.; Kumaran, S.; Coelho, A.; Nunes, R.; Carvalho, I.S. Omics Approaches in Fungal Biotechnology. In Omics Technologies and Bio-Engineering; Elsevier, 2018; pp 53–70. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Hussain, M.; Zhang, W.; Stadler, M.; Liu, X.; Xiang, M. Current Insights into Fungal Species Diversity and Perspective on Naming the Environmental DNA Sequences of Fungi. Mycology, 2019, 10, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global Diversity and Geography of Soil Fungi. Science (80-. ). 2014, 346. [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Kõljalg, U.; Abarenkov, K. Identifying the ‘Unidentified’ Fungi: A Global-Scale Long-Read Third-Generation Sequencing Approach. Fungal Divers. 2020, 103, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Mikryukov, V.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Khalid, A.N.; Corrales, A.; Agan, A.; Vasco-Palacios, A.-M.; Saitta, A.; Antonelli, A.; et al. The Global Soil Mycobiome Consortium Dataset for Boosting Fungal Diversity Research. Fungal Divers. 2021, 111, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, N.; Zhang, Y. Soil Aggregates Regulate the Impact of Soil Bacterial and Fungal Communities on Soil Respiration. Geoderma 2019, 337, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivusaari, P.; Tejesvi, M.V.; Tolkkinen, M.; Markkola, A.; Mykrä, H.; Pirttilä, A.M. Fungi Originating From Tree Leaves Contribute to Fungal Diversity of Litter in Streams. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liber, J.A.; Minier, D.H.; Stouffer-Hopkins, A.; Van Wyk, J.; Longley, R.; Bonito, G. Maple and Hickory Leaf Litter Fungal Communities Reflect Pre-Senescent Leaf Communities. PeerJ, 2022, 10, e12701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osono, T. Functional Diversity of Ligninolytic Fungi Associated with Leaf Litter Decomposition. Ecol. Res. 2020, 35, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongsanan, S.; Jeewon, R.; Purahong, W.; Xie, N.; Liu, J.-K.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Ekanayaka, A.H.; Dissanayake, A.; Raspé, O.; Hyde, K.D.; et al. Can We Use Environmental DNA as Holotypes? Fungal Divers. 2018, 92, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, R.S.; Purahong, W.; Zhang, W.; Wubet, T.; Li, X.; Liu, M.; Zhao, W.; Hyde, K.D.; Liu, J.; Yan, J. Biodiversity of Fungi on Vitis vinifera L. Revealed by Traditional and High-Resolution Culture-Independent Approaches. Fungal Divers. 2018, 90, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayer, M.; Wymore, A.S.; Hungate, B.A.; Schwartz, E.; Koch, B.J.; Marks, J.C. Microbes on Decomposing Litter in Streams: Entering on the Leaf or Colonizing in the Water? ISME J. 2022, 16, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osono, T. Role of Phyllosphere Fungi of Forest Trees in the Development of Decomposer Fungal Communities and Decomposition Processes of Leaf Litter. Can. J. Microbiol. 2006, 52, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleklett, K.; Ohlsson, P.; Bengtsson, M.; Hammer, E.C. Fungal Foraging Behaviour and Hyphal Space Exploration in Micro-Structured Soil Chips. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.K.; Verma, R.K.; Avasthi, S.; Sushma; Bohra, Y.; Devadatha, B.; Niranjan, M.; Suwannarach, N. Current Insight into Traditional and Modern Methods in Fungal Diversity Estimates. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Acremonium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Acrocalymma ampeli | ✓ | |||||||||

| Alternaria burnsii | ✓ | |||||||||

| Alternaria pseudoeichhorniae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Anthostomella clypeata | ✓ | |||||||||

| Anthostomella reniformis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Appendiculella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Arthrinium hydei | ✓ | |||||||||

| Arthrinium sacchari | ✓ | |||||||||

| Arthrinium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Arxiella celtidis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Aspergillus sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Asteridiella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Asterina sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Auxarthron sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Backusella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Bartalinia robillardoides | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Beltrania concurvispora | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Beltrania rhombica | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Beltrania sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Beltraniella portoricensis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Beltraniella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Botryodiplodia theobromae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Brooksia tropicalis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Camposporium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Catenosubulispora sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cephalosporiopsis sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Ceramothyrium longivolcaniforme | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cercophora fici | ✓ | |||||||||

| Chaetopsina fulva | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Chaetospermum camelliae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Chaetospermum sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Chaetosphaeria sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Chaetospermum camelliae | ||||||||||

| Chaetospermum sp. | ||||||||||

| Chaetosphaeria sp. | ||||||||||

| Chalara cf.nigricollis | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cylindrocarpon cf.orthosporum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cylindrocladiella elegans | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cylindrocladiella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cylindrocladium colhounii | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cylindrocladium coulhouniivar.coulhounii | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Cylindrocladium floridanum | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cylindrocladium ilicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cylindrocladium retaudii | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cylindrocladium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cylindrosympodium cryptocaryae | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Cylindrosympodium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cylindrosympodium variabile | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Chalara sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Circinotrichum falcatisporum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Circinotrichum maculiforme | ✓ | |||||||||

| Circinotrichum sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cladosporium cladosporoides | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cladosporium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Cladosporium tenuissimum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Coccomyces cf.limitatus | ✓ | |||||||||

| Coelomycete sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Colletotrichum celtidis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Colletotrichum fici | ✓ | |||||||||

| Colletotrichum sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Coniella quercicola | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Conioscypha sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cryptophiale cf.guadalcanensis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cryptophiale kakombensis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Curvularia sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Gnomonia elaeocarpa | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gnomonia queenslandica | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dischloridium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Discosia celtidis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Discosia querci | ✓ | |||||||||

| Meliola sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Memnoniella alishanensis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Myrothecium lachastrae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Parasympodiella laxa | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Paraceratocladium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Parasympodiella elongate | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Phoma sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Phomopsis sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Dematiocladium celtidicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dendrosporium lobatum | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Diaporthe celtidis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Diaporthe limonicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Diaporthe millettiae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Diaporthe pseudophoenicicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Diaporthosporella macarangae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dictyoarthrinium africanum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dictyochaeta cf.novae-guineensis | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dictyochaeta sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Dictyocheirospora garethjonesii | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dictyosporium cf.australiense | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dimorphiseta acuta | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dinemasporium parastrigosum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dinemasporium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Gnomonia sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Goidanichiella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Guignardia sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gyrothrix circinata | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gyrothrix pediculata | ✓ | |||||||||

| Hansfordia pulvinata | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Harpographium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Helicosporium griseum | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Helicosporium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Hermatomyces biconisporus | ✓ | |||||||||

| Hermatomyces sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Hyponectria sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Idriella acerosa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Idriella cagnizarii | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Idriella lunata | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Idriella ramosa | ✓ | |||||||||

| Idriella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Ijuhya sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Discostroma ficusicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Falcocladium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Flabellocladia sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Fusarium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Geotrichum sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gliocephalotrichum simplex | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gliocephalotrichum sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gliocladiopsis sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Gliocladiopsis tenuis | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gliocladium solani | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gliocladium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Gliomastix elasticae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gliomastix murorum | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gliomastix luzulae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gliomastix macrocerealis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gliomastix sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Ijuhya aquifolii | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ijuhya leucocarpa | ✓ | |||||||||

| Iodosphaeria phyllophila | ✓ | |||||||||

| Iodosphaeria sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Isthmolongispora intermedia | ✓ | |||||||||

| Kramasamuha cf. sibika | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kylindria sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lachnum sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Lanceispora amphibia | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Lasiodiplodia thailandica | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lauriomyces helicocephala | ✓ | |||||||||

| Leptospora macarangae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Leptothyrium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Longihyalospora ampeli | ✓ | |||||||||

| Marasmius sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Myrothecium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Neoanthostomella fici | ✓ | |||||||||

| Neodictyosporium macarangae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Neofusicoccum moracearum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Neopestalotiopsis asiatica | ✓ | |||||||||

| Niesslia sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Nigrospora macarangae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Nigrospora panici | ✓ | |||||||||

| Nodulisporium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Oblongihyalospora macarange | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ochroconis humicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Oidiodendron tenuissimum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ophioceras chiangdaoense | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ophiognomonia elasticae | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Ophiognomonia sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Strigula multiformis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Memnoniella celtidis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Memnoniella echinata | ✓ | |||||||||

| Menisporopsis theobromae | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Microdochium phragmites | ✓ | |||||||||

| Microdochium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Micropeltis fici | ✓ | |||||||||

| Micropeltis ficinae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Minimidochium microsporum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mollisia sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mortierella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mucor racemosus | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mucor sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Muyocopron celtidis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Muyocopron dipterocarpi | ✓ | |||||||||

| Muyocopron lithocarpi | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mycena sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Mycosphaerella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Parasympodiella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Parawiesneriomyces chiayiense | ✓ | |||||||||

| Penicillium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Periconia alishanica | ✓ | |||||||||

| Periconia byssoides | ✓ | |||||||||

| Periconia celtidis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Periconia sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Pestalotiopsis versicolor | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pestalotiopsis breviseta | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pestalotiopsis dracaenea | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pestalotiopsis papuana | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pestalotiopsis sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Pestalotiopsis trachycarpicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Phaeoisaria sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Phaeosphaeria ampeli | ✓ | |||||||||

| Phialocephala bactrospora | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Phyllosticta capitalensis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Phyllosticta sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Polyscytalum sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pseudobeltrania sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pseudomicrodochium antillarum | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Pseudoneottiospora cannabina | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pseudopestalotiopsis camelliae-sinensis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pseudopithomyces chartarum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pseudorobillarda phragmitis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pseudospiropes pinarensis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pyricularia sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Rhinocladiella cristaspora | ✓ | |||||||||

| Rhinocladiella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Rhizopus stolonifer | ✓ | |||||||||

| Roumeguerilla sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Scolecobasidium cf.fusiforme | ✓ | |||||||||

| Scolecobasidium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Selenodriella fertilis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Selenodriella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Selenosporella curvispora | ✓ | |||||||||

| Selenosporella cristata | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Selenosporella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Sirastachys pandanicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Speiropsis pedatospora | ✓ | |||||||||

| Speiropsis sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sphaeridium pilosum | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sphaeridium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Spiropes sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sporidesmium cf.ponapense | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sporidesmium sp.nov. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sporodesmiella garciniae | ✓ | |||||||||

| Stachybotrys aloeticola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Stachybotrys cf.parvispora | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Subulispora procurvata | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Thozetella falcata | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Thozetella gigantea | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Thozetella queenslandica | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Thozetella boonjiensis | ✓ | |||||||||

| Thozetella radicata | ✓ | |||||||||

| Thozetella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Thysanophora sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Torula fici | ✓ | |||||||||

| Torula sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Trichoderma sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Trichoderma viride | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Trichothecium sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Verticillium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Verticimonosporium ellipticum | ✓ | |||||||||

| Volutella ramkurii | ✓ | |||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Wiesneriomyces javanicus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Wiesneriomyces laurinus | ✓ | |||||||||

| Wiesneriomyces sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Yunnanomyces pandanicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Zygosporium echinosporium | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Zygosporium mansonii | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Zygosporium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Xylaria sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dactylaria ficusicola | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dictyochaeta simplex | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Dactylaria belliana | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dactylaria section Mirandina sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dactylaria sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Dactylella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cylindrocarpon cf.ianthothele | ✓ | |||||||||

| Stachybotrys sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Stilbella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Taxon name | ND (Lauraceae) |

FP (Moraceae) |

FA (Moraceae) | CF (Lauraceae) | MT (Euphorbiaceae) | CM (Lauraceae) | DF (Proteaceae) | EA (Elaeocarpaceae) | FD (Moraceae) | OH (Proteaceae) |

| Wiesneriomyces javanicus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Wiesneriomyces laurinus | ✓ | |||||||||

| Wiesneriomyces sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Yunnanomyces pandanicola | ✓ | |||||||||

| Zygosporium echinosporium | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Zygosporium mansonii | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Zygosporium sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Xylaria sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dactylaria ficusicola | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dictyochaeta simplex | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Dactylaria belliana | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dactylaria section Mirandina sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dactylaria sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Dactylella sp. | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cylindrocarpon cf.ianthothele | ✓ | |||||||||

| Volutella sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Wardomyces sp. | ✓ |

| Family | Species | Recorded fungal taxa | Country | Number of fungal taxa | References | |

| 1 | Anacardiaceae | Anacardium occidentale | Dactylaria biseptata, Dicyma vesiculifera, Emericella nidulans, Fusarium dimerum, Fusarium oxysporum, Gibberella bacata, Gloeosporium musarum, Glomerella tucumanensis, Gyrothrix circinata, Gyrothrix podosperma, Hansfordia pulvinata, Henicospora coronata, Idriella lunata, Khuskia oryzae, Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Leptosphaerulina chartarum, Meliola sp., Memnoniella echinata, Metulocladosporiella musae, Paecilomyces carneus, Parasympodiella laxa, Penicillium citrinum, Penicillium funiculosum, Penicillium oxalicum, Penicillium verruculosum, Pestalotiopsis theae, Phaeotrichoconis crotalariae, Pithomyces maydicus, Polyscytalum fecundissimum, Pseudobeltrania penzigii, Pseudocochliobolus eragrostidis, Scolecobasidium tshawytschae, Selenodriella fertilis, Selenosporella curvispora, Setosphaeria rostrata, Stachybotrys chartarum, Staphylotrichum coccosporum, Subramaniomyces fusisaprophyticus, Thozetella tocklaiensis, Torula herbarum, Trichoderma harzianum, Trichoderma viride, Trichothecium roseum, Volutella ciliata, Wiesneriomyces laurinus, Zygosporium gibbum, Zygosporium masonii, Zygosporium oscheoides | India | 48 | [135,137 |

| Family | Species | Recorded fungal taxa | Country | Number of fungal taxa | References | |

| 2 | Magnoliaceae | Magnolia liliifera | Albonectria rigidiuscula, Anthostomella monthadoia, Anthostomella tenacis, Bionectria ochroleuca, Bionectria palmicola, Bionectria sp., Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Colletotrichum sp., Corynespora cassiicola, Cylindrocladium floridanum, Dactylaria dimorphospora, Dactylaria longidentata, Dokmaia monthadangii, Fusarium sp., Giugnardia sp., Gliocladium sp., Guignardia mangiferae, Haematonectria haematococca, Hyponectria manglietiae, Hyponectria manglietiagarrettii, Hyponectria sp., Hyponectria suthepensis, Hypoxylon sp., Ijuhya parilis, Leptosphaeria sp., Munkovalsaria appendiculata, Hyponectria manglietiagarrettii, Hyponectria sp., Hyponectria suthepensis, Hypoxylon sp., Ijuhya parilis, Leptosphaeria sp., Munkovalsaria appendiculata, Munkovalsaria magnoliae, Nectria haematococca, Nectria sp., Periconia jabalpurensis, Phaeosphaeria sp., Phoma sp., Phomopsis sp., Phyllosticta capitaliensis, Physalospora sp., Pseudohalonectria suthepensis, Rhytisma sp., Sporidesmium crassisporum, Stachybotrys parvispora, Volutella sp. | Thailand | 47 | [97] |

| Family | Species | Recorded fungal taxa | Country | Number of fungal taxa | References | |

| 3 | Fagaceae | Castanopsis diversifolia | Acremonium sp., Albonectria albosuccinea, Alternaria sp., Annulatascaceae sp., Ardhachandra cristaspora, Arthrinium sp., Aspergillus sp., Asterina sp., Bacillispora aquatica, Beltrania mangiferae, Beltrania rhombica, Beltraniella odinae, Beltraniella portoricensis, Beltraniella sp., Bipolaris cynodontis, Cercosporula sp., Chaetendophragmia triangularia, Chaetosphaeria sp., Chalara pteridina, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium oxysporum, Cladosporium sp., Cladosporium sphaerospermum, Cladosporium tenuissimum, Clonostachys candelabrum, Clonostachys compactiuscula, Coelomycete sp., Cryptophiale udagawae, Cylindrocladium gracile, Cylindrocladium pseudogracile, Cylindrum griseum, Dendrodochium cylindricum, Dictyochaeta cylindrospora, Dictyochaeta heteroderae, Dictyochaeta simplex, Dictyochaeta sp., Dictyochaeta stipiticolla, Emarcea castanopsidicola, Endophragmiella sp., Fusarium sp., Geotrichum candidum, Gnomonia gnomon, Hansfordia sp., Haplographium sp., Helicosporium talbotii, Hyponectria buxi, Idriella fertilis, Idriella sp., Kionochaeta spissa, Kramasamuha sibika, Lachnum sp., Lauriomyces bellulus,Lecanicillium lecanii, Lichenopeltella salicis, Lophodermium australiense, Lophodermium sp., Marasmius sp., Menisporopsis novaezelandiae, Microdochium phragmitis, Microthyrium sp., Monochaetia sp., Mycena sp., Mycosphaerella sp., Oedocephalum sp., Ophioceras commune, Parasympodiella laxa, Penicillium sp., Periconia cookei, Periconia paludosa, Periconia sp., Pestalosphaeria hansenii, Pestalotiopsis tecomicola, Phaeoisaria sp., Phomopsis sp., Pithomyces karoo, Pseudobotrytis terrestris, Pseudohalonectria phialidica, Ramularia gei, Stemonitis sp., Stictis sp., Stomiopeltis sp., Subramaniomyces fusisaprophyticus, Subulispora procurvata Thozetella sp., Thysanophora sp., Tritirachium bulbophorum, Verticillium sp., Wiesneriomyces javanieus, Xenocylindrocladium sp., Zygosporium gibbum, Zygosporium minus | Thailand | 91 | [131] |

| Family | Species | Recorded fungal taxa | Country | Number of fungal taxa | References | |

| 4 | Rubiaceae | Pavetta indica | Acremonium sp., Alternaria alternata, Ardhachandra selenoides, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus japonicus, Bartalinia robillardoides, Beltrania rhombica, Beltraniella portoricensis, Beltraniella sp., Botryodiplodia theobromae, Chaetomium seminudam, Chaetomium spirale, Circinotrichum falcatisporum, Circinotrichum fertile, Circinotrichum maculiforme, Circinotrichum papakurae, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium oxysporum, Colletotrichum falcatum, Corynespora cassiicola, Curvularia brachyspora, Curvularia intermedia, Curvularia lunata, Cylindrocladium parvum, Cylindrocladium quinqueseptatum, Drechslera halodes, Euantennaria sp., Fusarium lateritium, Fusarium oxysporum, Gyrothrix podosperma, Gyrothrix circinata, Harknessia sp., Helicosporium helicosporum, Helicosporium vegetum, Hermatomyces sphaericus, Idriella sp., Leptoxyphium sp., Meliola sp., Penicillium sp., Pestalotiopsis theae, Selenosporella curvispora, Sesquicillium setosum, Stachybotrys parvispora, Thysanophora assymetrica, Torula herbarum, Tretopileus sp., Trichoderma viride, Verticillium sp., Volutella ciliata, Wiesneriomyces javanicus, Zygosporium echinosporum, Zygosporium gibbum, Zygosporium masonii, Zygosporium oscheoides | India | 54 | [136] |

| 5 | Dipterocarpaceae | Shorea obtusa | Amphisphaeriaceae sp., Aspergillus sp., Beltrania rhombica, Beltraniella portoricensis, Chaetomium globosum, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium oxysporum, Clonostachys rosea, Coelomycete sp., Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Eupenicillium cf. senticosum, Eurotium sp., Geniculospolium sp., Geniculosporium sp., Gliocephalotrichum sp., Gliocladium virens, Lachnocladiaceae sp., Mucor sp., Nigrospora sp., Nodulisporium sp., Pestalotiopsis sp., Talaromyces sp., Trichoderma asperellum, Trichoderma hamatum, Xylaria sp. | Thailand | 25 | [133] |

| Family | Species | Recorded fungal taxa | Country | Number of fungal taxa | References | |

| 6 | Lauraceae | Neolitsea dealbata | Acremonium sp., Anthostomella clypeata, Arthrinium sp., Aspergillus sp., Beltrania rhombica, Beltrania sp., Beltraniella portoricensis, Beltraniella sp., Camposporium sp., Chalara sp., Cladosporium cladosporoides, Coelomycete sp., Colletotrichum sp., Cylindrosympodium sp., Dactylaria sp., Dictyoarthrinium africanum, Dictyochaeta sp., Fusarium sp., Geotrichum sp., Gliocephalotrichum sp., Gliocladium sp., Gyrothrix circinata, Gyrothrix pediculata, Helicosporium sp., Idriella sp., Iodosphaeria phyllophila, Menisporopsis theobromae, Mucor sp., Myrothecium sp., Penicillium sp., Periconia sp., Pestalotiopsis versicolor, Pestalotiopsis sp., Phoma sp., Phomopsis sp., Phyllosticta sp., Rhinocladiella sp., Selenosporella curvispora, Speiropsis sp., Stachybotrys sp., Thozetella radicata, Thozetella sp., Thysanophora sp., Torula sp., Trichoderma sp., Wardomyces sp., Wiesneriomyces javanicus, Wiesneriomyces sp. | Australia | 48 | [87] |

| 7 | Moraceae | Ficus ampelas | Acrocalymma ampeli, Aspergillus sp., Backusella sp., Beltrania rhombica, Ceramothyrium longivolcaniforme, Cercophora fici, Colletotrichum fici, Coniella quercicola, Cylindrocladium sp., Diaporthe limonicola, Diaporthe pseudophoenicicola, Discosia querci, Fusarium sp., Lasiodiplodia thailandica, Longihyalospora ampeli, Micropeltis fici, Micropeltis ficinae, Mortierella sp., Mycosphaerella sp., Neoanthostomella fici, Neofusicoccum moracearum, Penicillium sp., Periconia sp., Phaeosphaeria ampeli, Phoma sp., Phyllosticta sp., Pseudopestalotiopsis camelliae-sinensis, Rhizopus stolonifer, Torula fici, Volutella sp., Wiesneriomyces laurinus, Yunnanomyces pandanicola, Zygosporium sp. | China | 34 | [30] |

| 8 | Euphorbiaceae |

Macaranga tanarius |

Alternaria burnsii, Alternaria pseudoeichhorniae, Arthrinium sacchari, Aspergillus sp., Asteridiella sp., Cladosporium sp., Cladosporium tenuissimum, Diaporthosporella macarangae, Dictyocheirospora garethjonesii, Hermatomyces biconisporus, Hermatomyces sp., Idriella sp., Leptospora macarangae, | China | 30 | [30] |

| Family | Species | Recorded fungal taxa | Country | Number of fungal taxa | References | |

| Meliola sp., Memnoniella alishanensis, Memnoniella echinata, Neodictyosporium macarangae, Nigrospora macarangae, Oblongihyalospora macarangae, Parawiesneriomyces chiayiense, Penicillium sp., Periconia alishanica, Periconia byssoides, Periconia celtidis, Phoma sp., Phyllosticta sp., Pseudopithomyces chartarum, Stachybotrys aloeticola, Zygosporium sp. | ||||||

| 9 | Proteaceae | Darlingia ferruginea | Acremonium sp., Beltraniella portoricensis, Botryodiplodia theobromae, Brooksia tropicalis, Chaetospermum sp., Cryptophiale cf.guadalcanensis, Cryptophiale kakombensis, Cylindrocladium coulhouniivar.coulhounii, Dictyochaeta simplex, Gliocladiopsis sp., Harpographium sp., Helicosporium sp., Hyponectria sp., Ijuhya aquifolii, Kramasamuha cf. sibika, Lachnum sp., Marasmius sp., Mycena sp., Ophiognomonia sp., Parasympodiella elongata, Pestalotiopsis sp., Pseudobeltrania sp., Selenosporella cristata, Selenosporella sp., Stilbella sp., Thozetella gigantea, Thozetella sp. | Australia | 27 | [87] |

| 10 | Elaeocarpaceae | Elaeocarpus angustifolius | Acremonium sp., Beltrania rhombica, Beltraniella portoricensis, Cephalosporiopsis sp., Chaetospermum sp., Chalara sp., Cladosporium sp., Coccomyces cf.limitatus, Cylindrocladium coulhouniivar.coulhounii, Cylindrocladium floridanum, Dactylaria sp., Dictyochaeta cf.novae-guineensis, Dictyochaeta simplex, Dictyochaeta sp., Dischloridium sp., Gliocephalotrichum simplex, Gliocladiopsis tenuis, Gnomonia elaeocarpa, Gnomonia queenslandica, Guignardia sp., Hansfordia pulvinata, Harpographium sp., Idriella acerosa, Idriella cagnizarii, Iodosphaeria sp., Kramasamuha cf. sibika, Lauriomyces helicocephala, Parasympodiella elongata, Penicillium sp., Pestalotiopsis sp., Phialocephala bactrospora, Phoma sp., Scolecobasidium cf.fusiforme, Scolecobasidium sp., Selenodriella sp., Selenosporella cristata, Selenosporella sp., Stachybotrys sp., Trichoderma viride | Australia | 39 | [87] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).