Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Method

Results

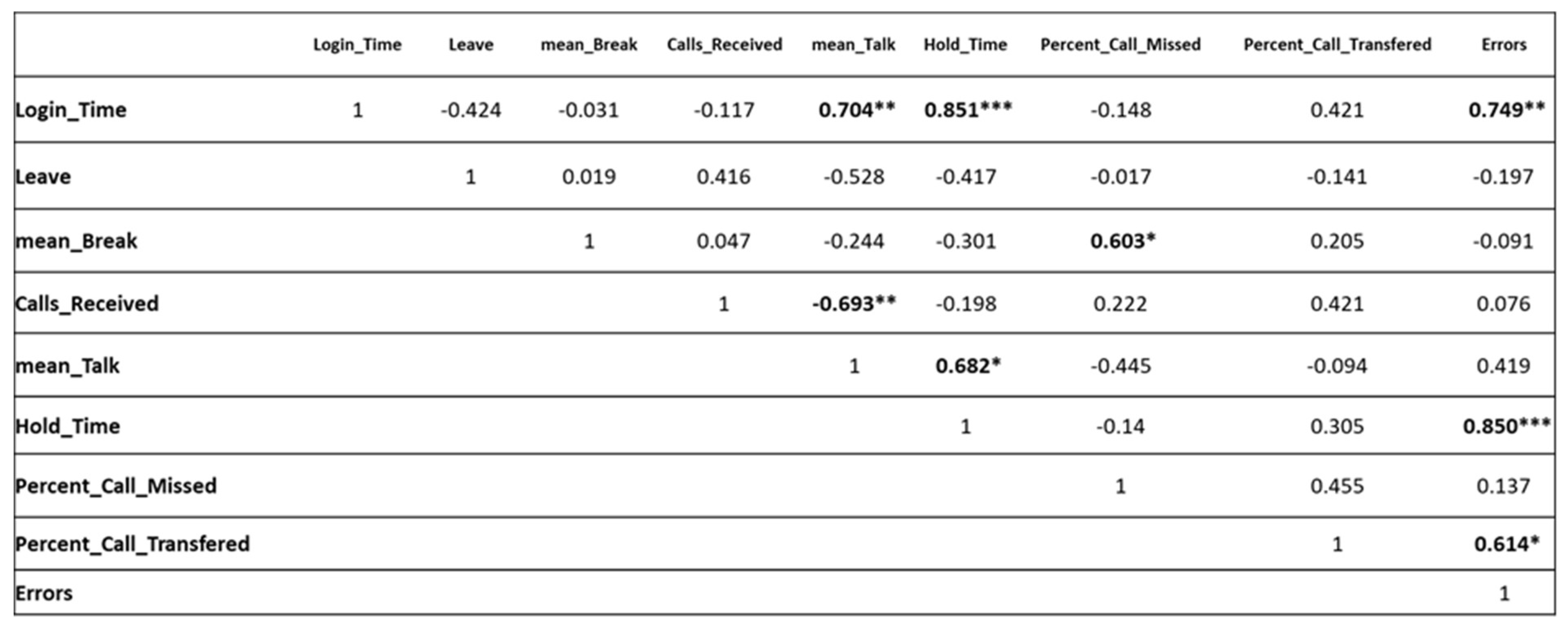

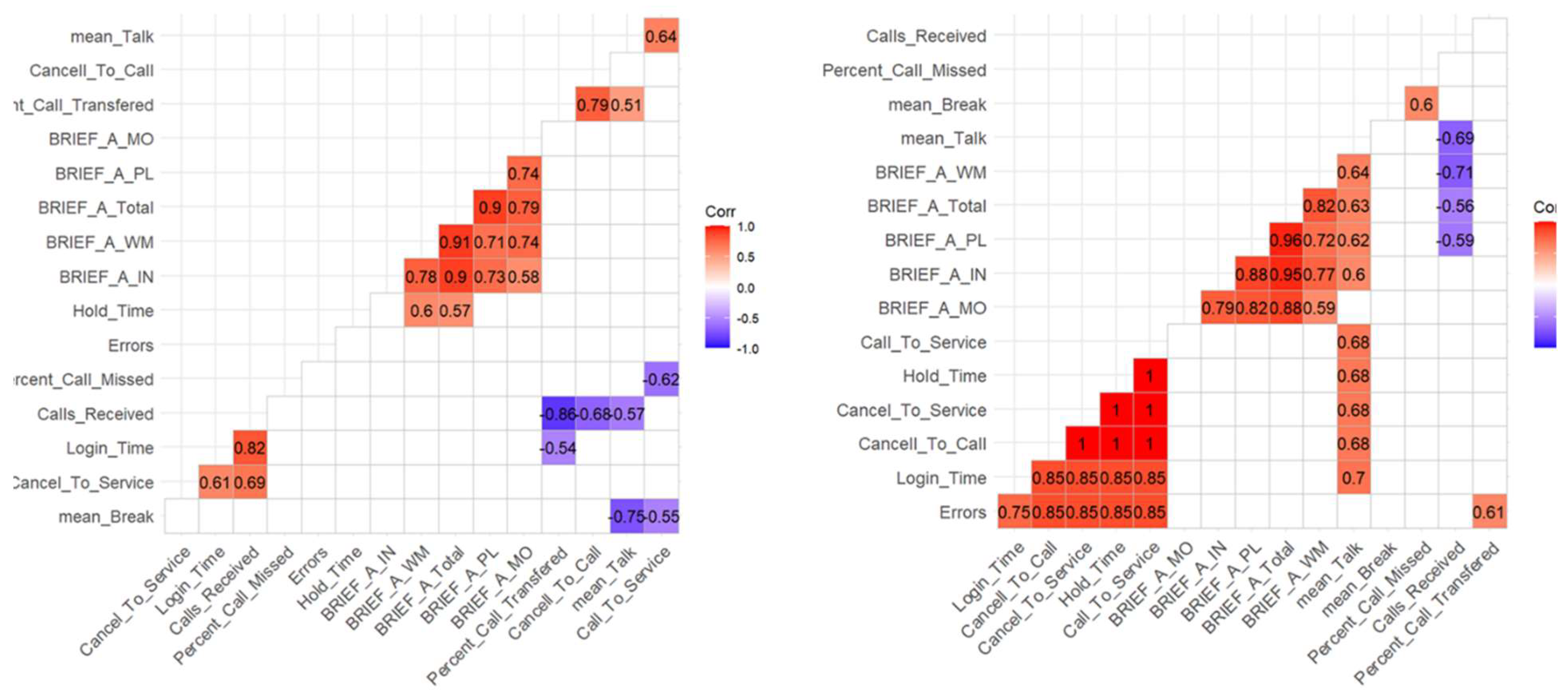

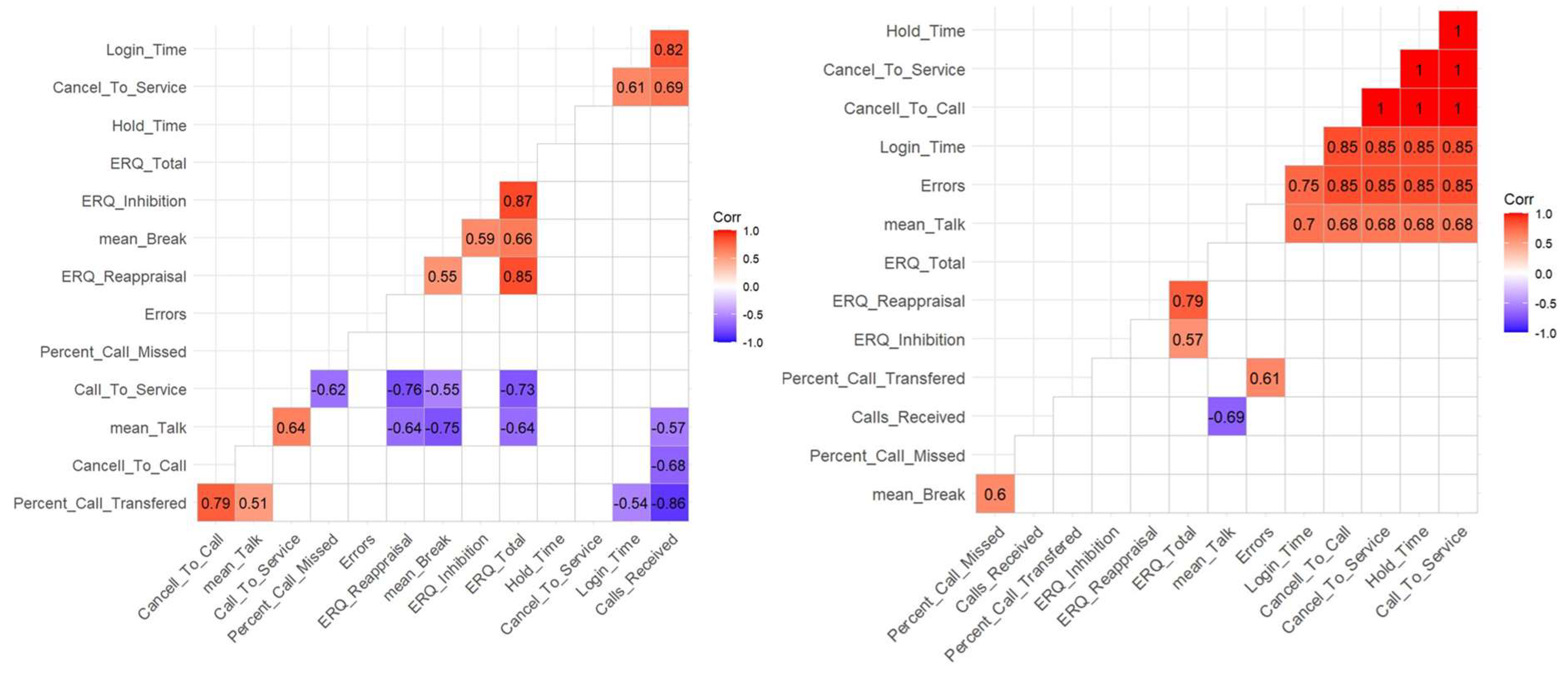

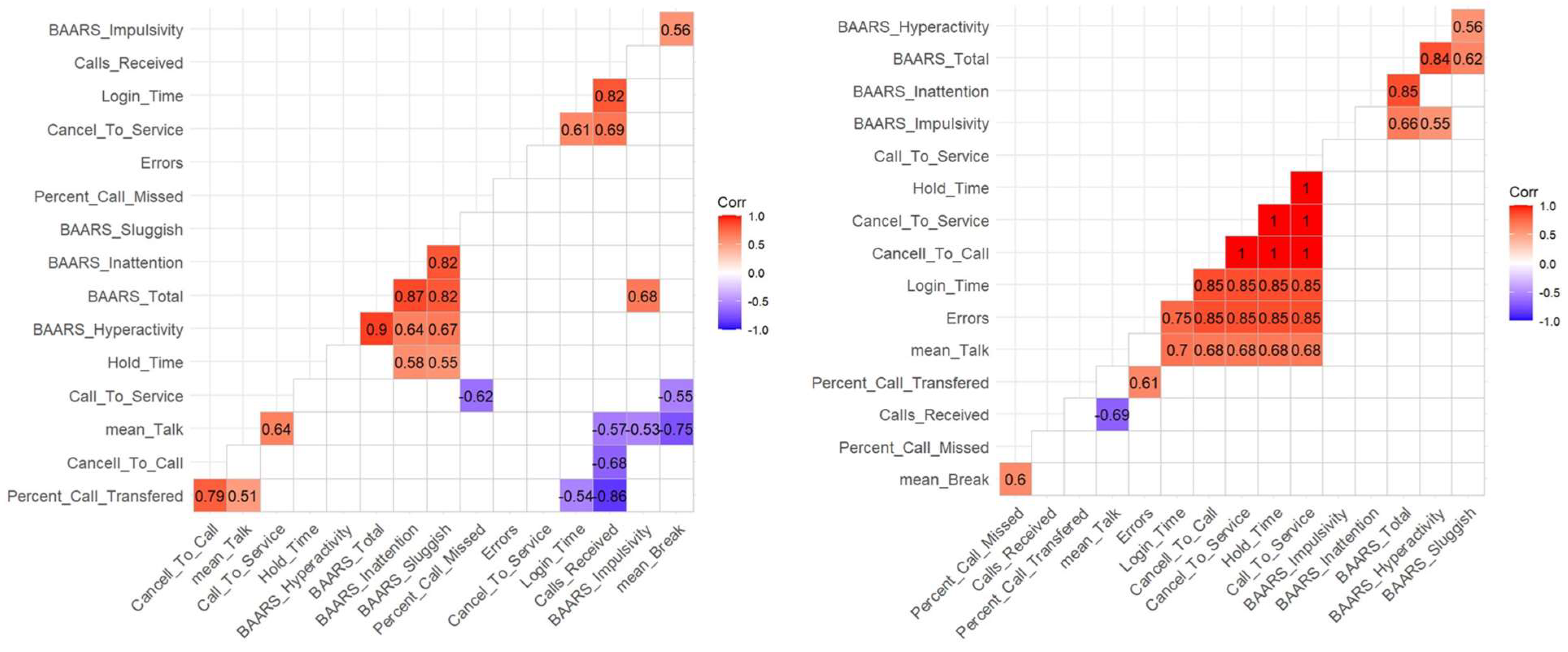

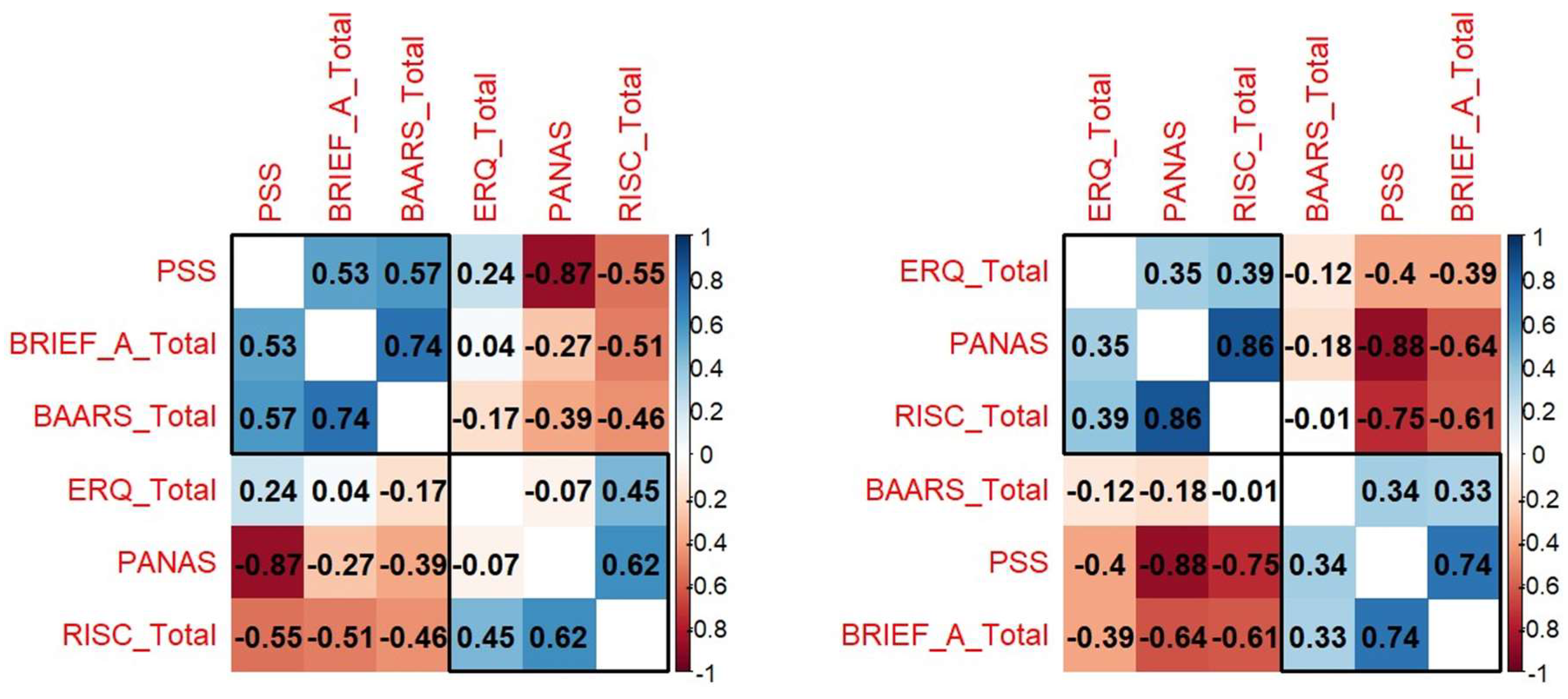

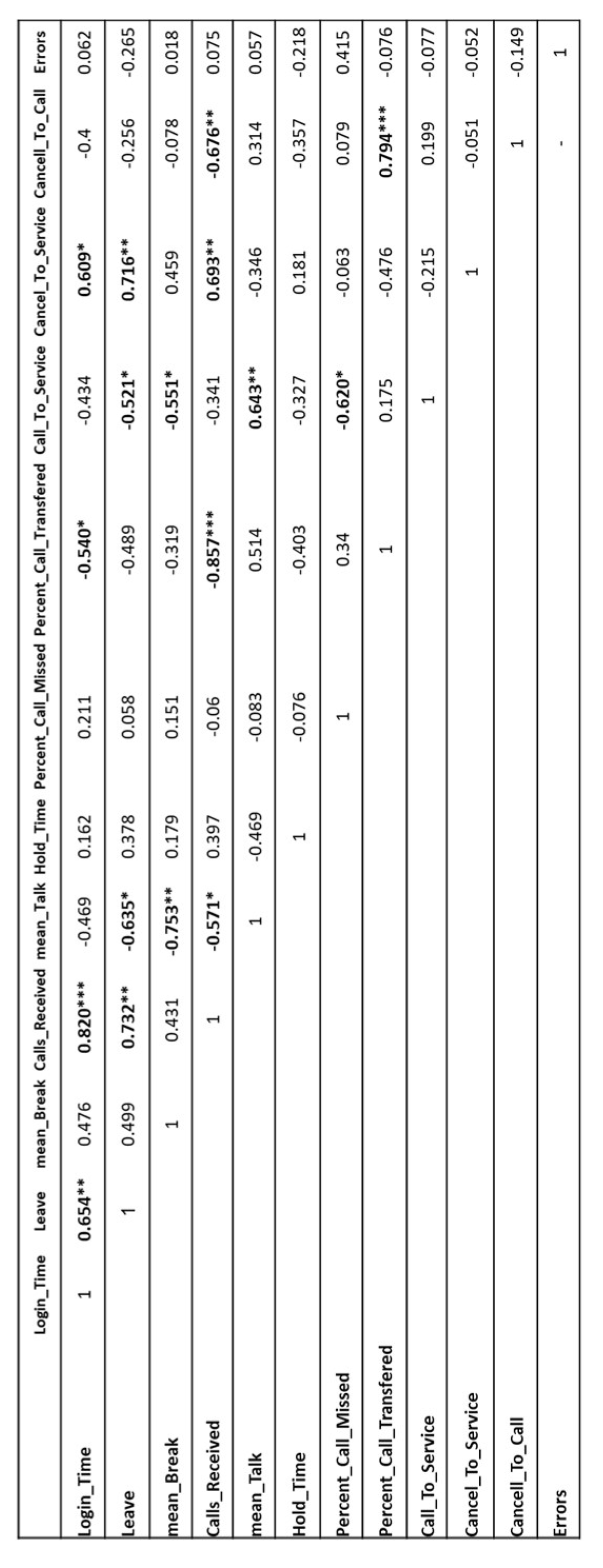

Correlation Between Performance Components

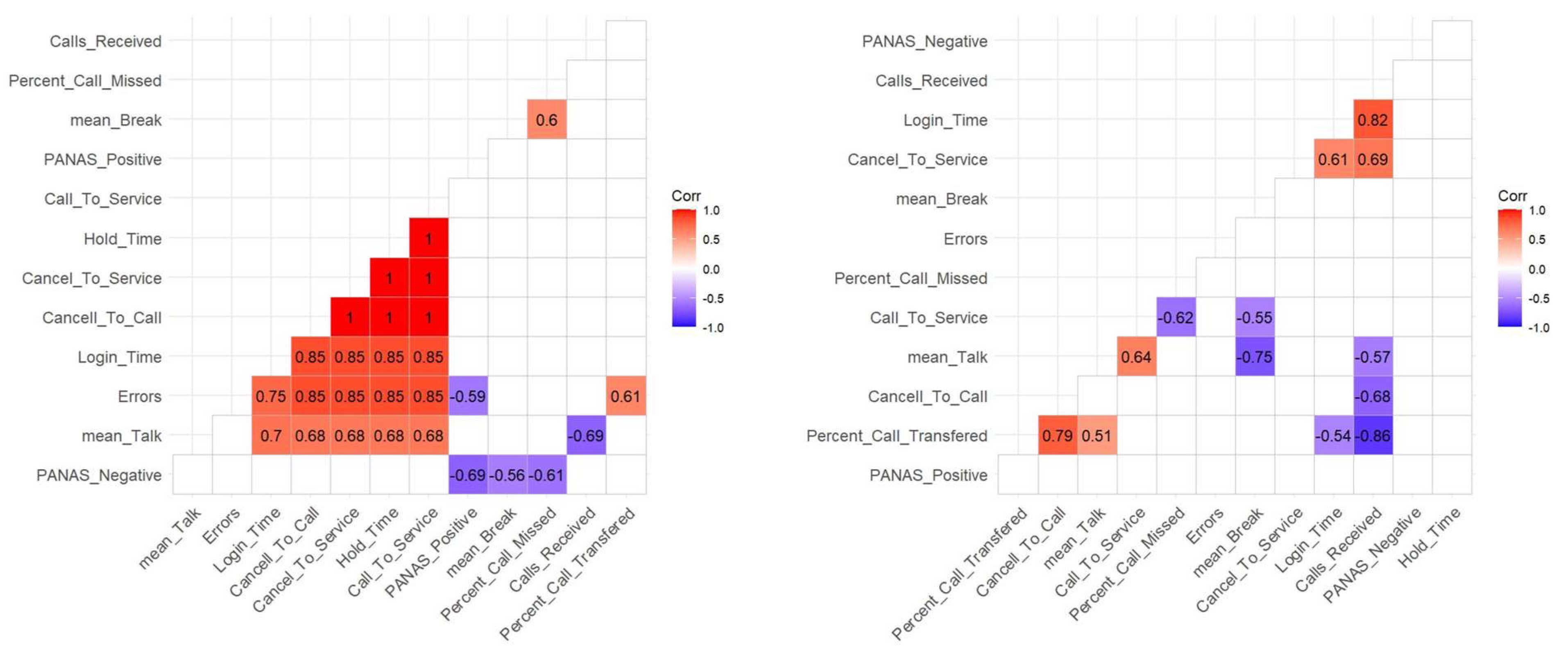

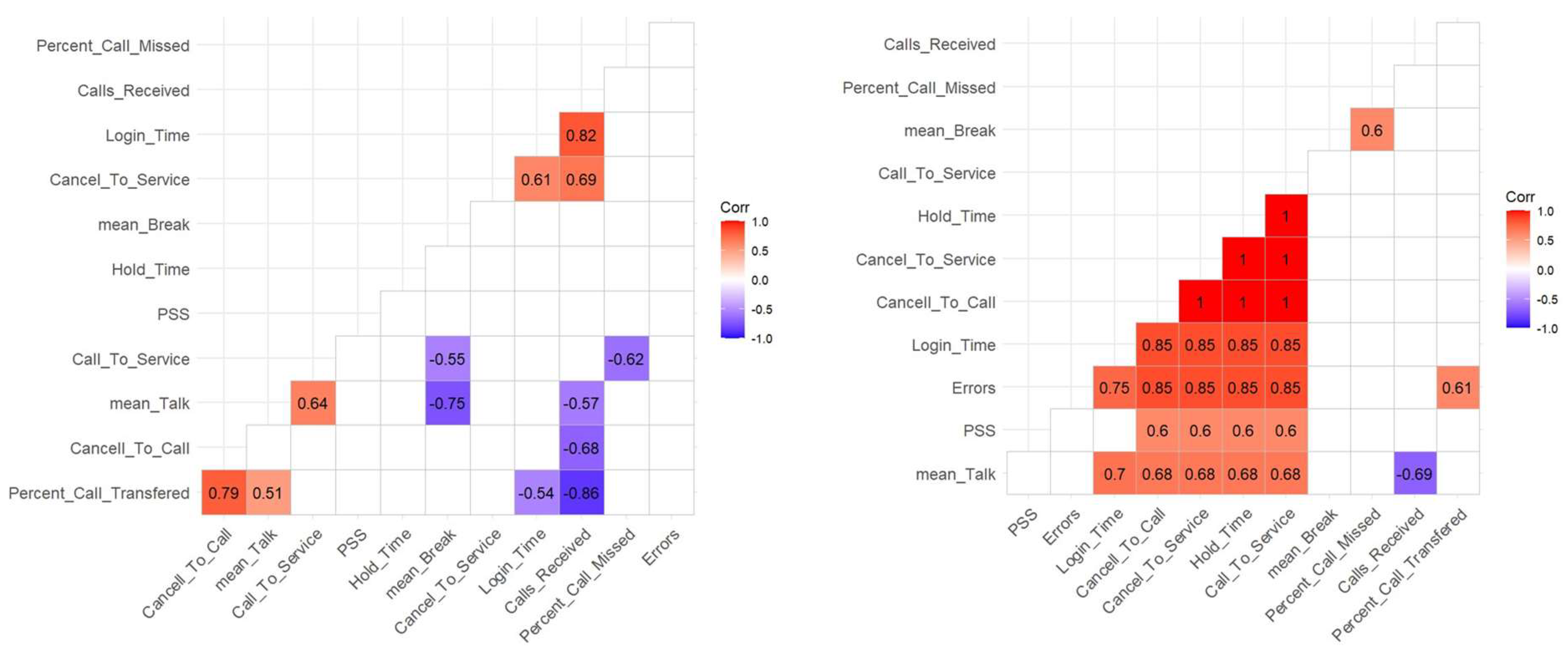

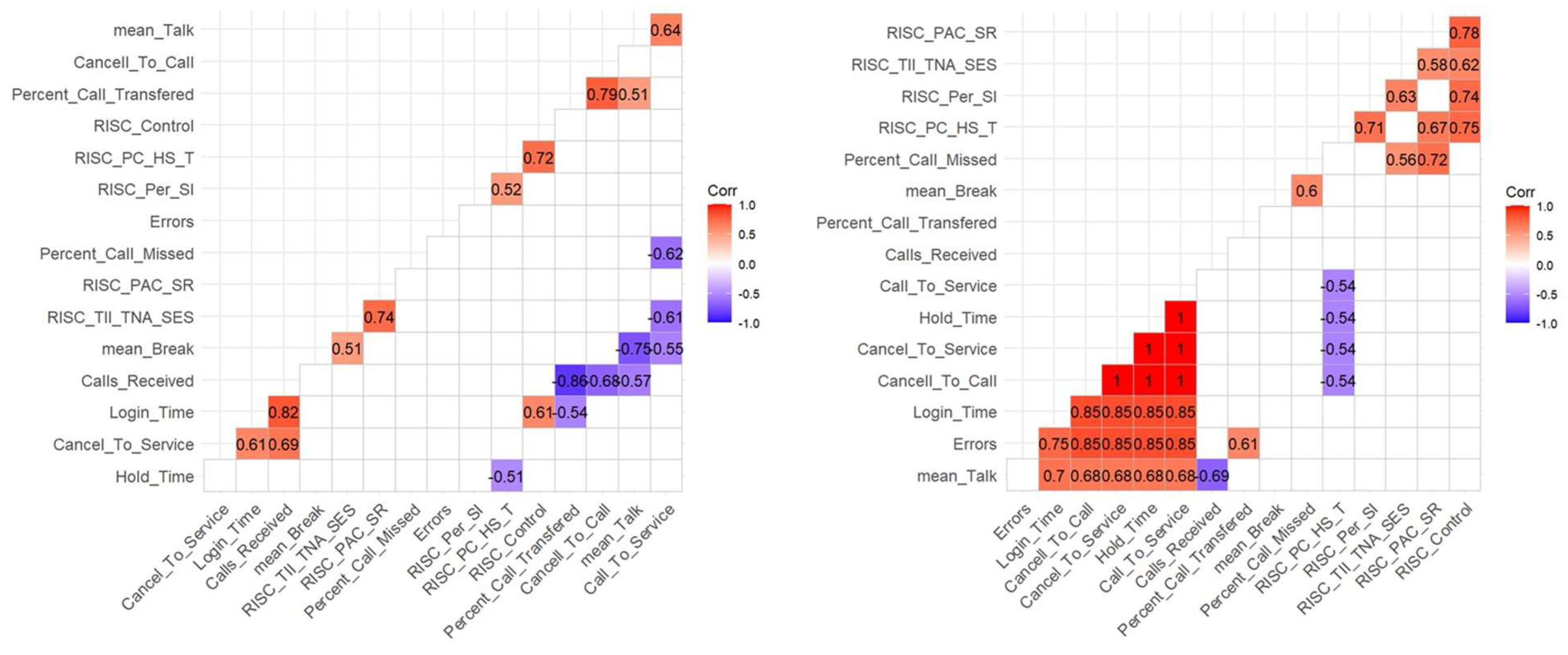

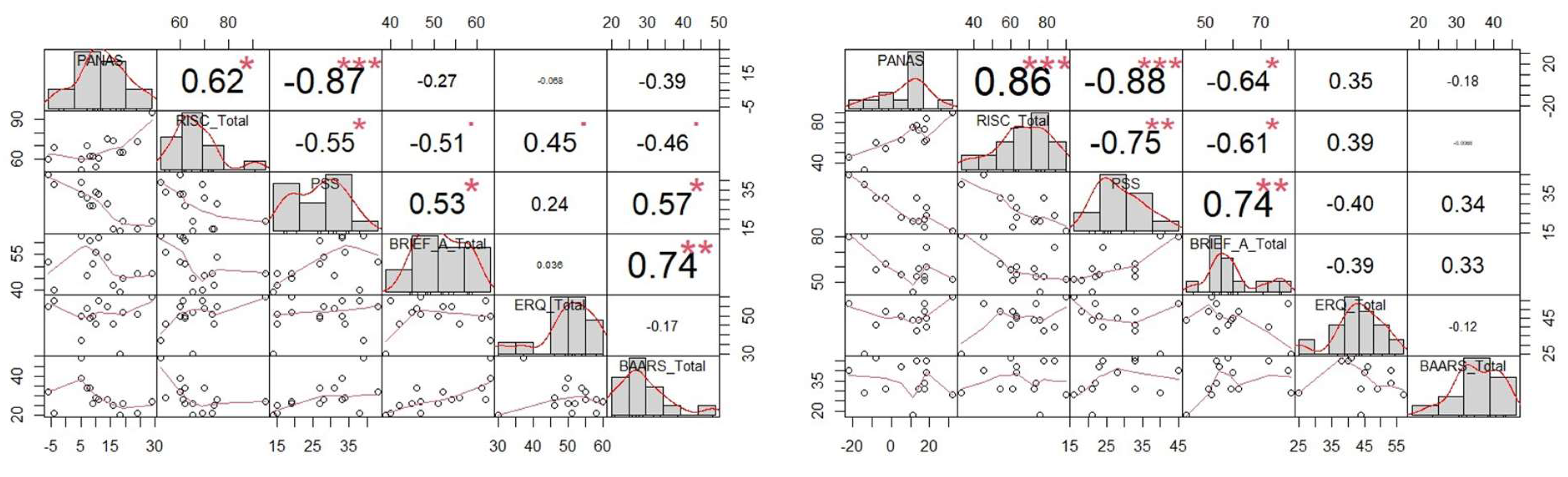

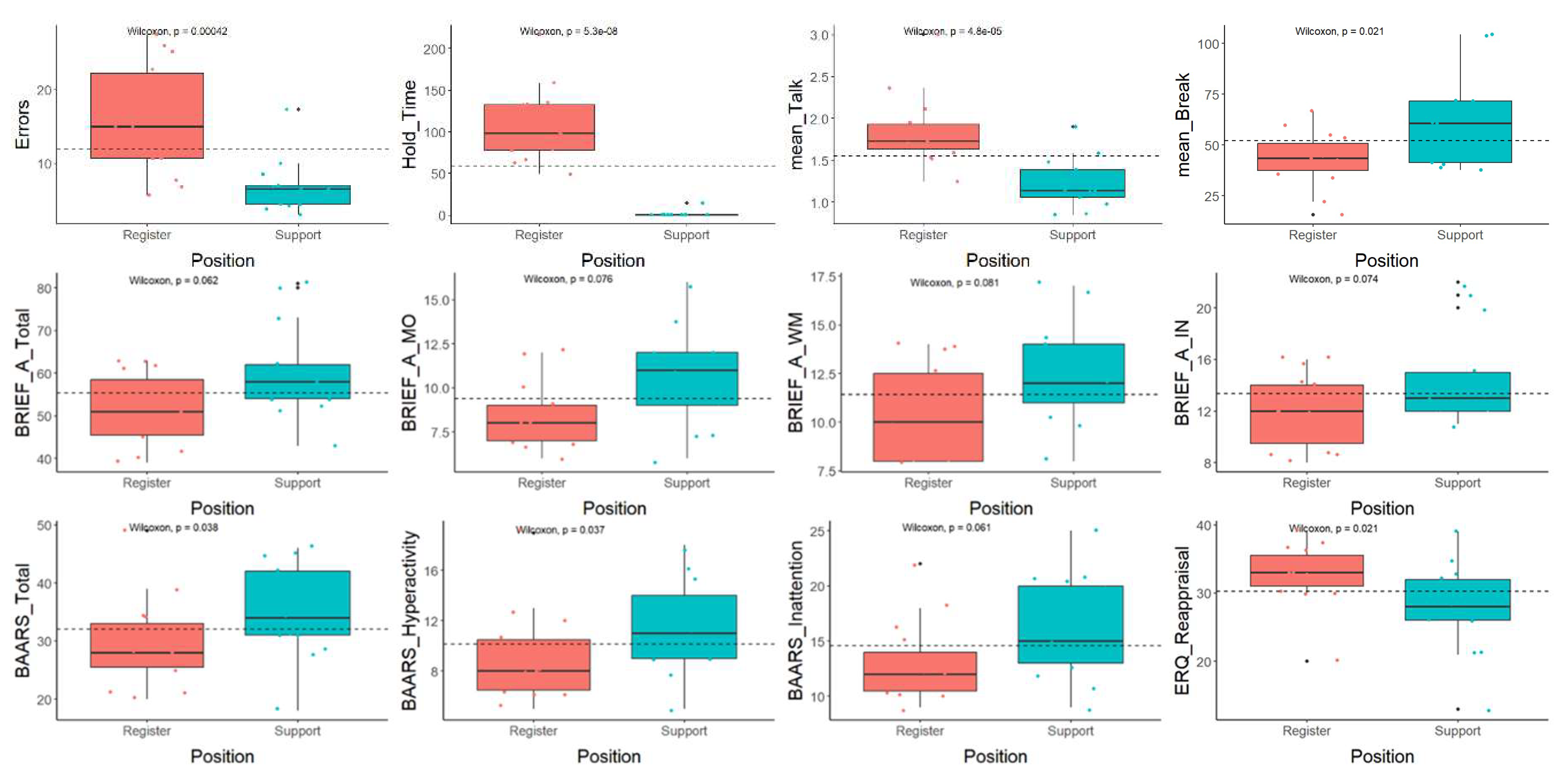

Cognitive Skills and Performance Components

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Alyahya, M. A. , Mohamed, E., Akamavi, R., Elshaer, I. A., & Azzaz, A. M. S. Can cognitive capital sustain customer satisfaction? The mediating effects of employee self-efficacy. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2020, 6, 191. [Google Scholar]

- Ayele, B. (2022). Factors affecting call center agentsperformance: the case of ethiopian electric utility (eeu). ST. MARY’S UNIVERSITY.

- Barkley, R. A. (2011). Barkley adult ADHD rating scale-iv (BAARS-IV). Guilford Press.

- Berardi, A. , Panuccio, F., Pilli, L., Tofani, M., Valente, D., & Galeoto, G. Evaluation instruments for executive functions in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 2021, 21, 885–896. [Google Scholar]

- Breslin, F. C. , & Pole, J. D. Work injury risk among young people with learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Canada. American Journal of Public Health 2009, 99, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cai, H. , & Lin, Y. Modeling of operators' emotion and task performance in a virtual driving environment. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2011, 69, 571–586. [Google Scholar]

- Canits, I. , Bernoster, I., Mukerjee, J., Bonnet, J., Rizzo, U., & Rosique-Blasco, M. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and academic entrepreneurial preference: is there an association? Small Business Economics 2019, 53, 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Charoensukmongkol, P. , & Puyod, J. V. Mindfulness and emotional exhaustion in call center agents in the Philippines: Moderating roles of work and personal characteristics. The Journal of General Psychology 2022, 149, 72–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, S. , Nasir, N., ur Rahman, S., & Sheikh, S. M. Impact of Work Load and Stress in Call Center Employees: Evidence from Call Center Employees. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 2023, 11, 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. , Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1983, 385–396. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K. M. , & Davidson, J. R. T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cristofori, I. , Cohen-Zimerman, S., & Grafman, J. Executive functions. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 2019, 163, 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyre, H. A. , Ayadi, R., Ellsworth, W., Aragam, G., Smith, E., Dawson, W. D., Ibanez, A., Altimus, C., Berk, M., & Manji, H. K. Building brain capital. Neuron 2021, 109, 1430–1432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fantinelli, S. , Galanti, T., Guidetti, G., Conserva, F., Giffi, V., Cortini, M., & Di Fiore, T. Psychological contracts and organizational commitment: the positive impact of relational contracts on call center operators. Administrative Sciences 2023, 13, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J. J. , & John, O. P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2003, 85, 348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gu, M. , Li Tan, J. H., Amin, M., Mostafiz, M. I., & Yeoh, K. K. Revisiting the moderating role of culture between job characteristics and job satisfaction: a multilevel analysis of 33 countries. Employee Relations: The International Journal 2022, 44, 70–93. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, A. , Forte, G., Giovannoli, J., & Casagrande, M. Executive functions in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review on motor and cognitive inhibition, conflict control and cognitive flexibility. Aging & Mental Health 2020, 24, 1028–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Gül, A. , Gül, H., Özkal, U. C., Kıncır, Z., Gültekin, G., & Emul, H. M. The relationship between sluggish cognitive tempo and burnout symptoms in psychiatrists with different therapeutic approaches. Psychiatry Research 2017, 252, 284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hafiza, N. S. , Manzoor, M., Fatima, K., Sheikh, S. M., Rahman, S. U., & Qureshi, G. K. MOTIVES OF CUSTOMER’S E-LOYALTY TOWARDS E-BANKING SERVICES: A STUDY IN PAKISTAN. PalArch's Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 2022, 19, 1599–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayah Ibrahim, S. N. , Suan, C. L., & Karatepe, O. M. The effects of supervisor support and self-efficacy on call center employees’ work engagement and quitting intentions. International Journal of Manpower 2019, 40, 688–703. [Google Scholar]

- Hülsheger, U. R. , & Schewe, A. F. On the costs and benefits of emotional labor: a meta-analysis of three decades of research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2011, 16, 361. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, M.-K. , Yoon, H., & Yang, Y. Emotional dissonance, job stress, and intrinsic motivation of married women working in call centers: The roles of work overload and work-family conflict. Administrative Sciences 2022, 12, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaasinen, E. , Schmalfuß, F., Özturk, C., Aromaa, S., Boubekeur, M., Heilala, J., Heikkilä, P., Kuula, T., Liinasuo, M., & Mach, S. Empowering and engaging industrial workers with Operator 4.0 solutions. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 139, 105678. [Google Scholar]

- Khattak, S. A. Role of ergonomics in re-designing job design in call centres. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics 2021, 27, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, G. M. , & Li, S. A practice-oriented overview of call center workforce planning. Stochastic Systems 2023, 13, 479–495. [Google Scholar]

- Körner, U. , Müller-Thur, K., Lunau, T., Dragano, N., Angerer, P., & Buchner, A. Perceived stress in human–machine interaction in modern manufacturing environments—Results of a qualitative interview study. Stress and Health 2019, 35, 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Koskina, A. , & Keithley, D. Emotion in a call centre SME: A case study of positive emotion management. European Management Journal 2010, 28, 208–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kujala, T. , & Lappi, O. Inattention and uncertainty in the predictive brain. Frontiers in Neuroergonomics 2021, 2, 718699. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N. Determinants of stress and well-being in call centre employees. Journal of Management 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonaki, R. , Xanthopoulou, D., Bardos, A. N., Karademas, E. C., & Simos, P. G. Burnout and job performance: a two-wave study on the mediating role of employee cognitive functioning. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2021, 30, 692–704. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-B. , an Yang, Dou, K., & Cheung, R. Y. M. Self-control moderates the association between perceived severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health problems among the Chinese public. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 4820. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, S. , Nima, A. A., Rapp Ricciardi, M., Archer, T., & Garcia, D. Exercise, character strengths, well-being, and learning climate in the prediction of performance over a 6-month period at a call center. Frontiers in Psychology 2014, 5, 497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murthy, N. N. , Challagalla, G. N., Vincent, L. H., & Shervani, T. A. The impact of simulation training on call center agent performance: A field-based investigation. Management Science 2008, 54, 384–399. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, M. , Nagata, T., Inoue, A., Mori, K., & Matsuda, S. Effect modification by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms on the association of psychosocial work environments with psychological distress and work engagement. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2019, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nye, C. D. , Ma, J., & Wee, S. Cognitive ability and job performance: Meta-analytic evidence for the validity of narrow cognitive abilities. Journal of Business and Psychology 2022, 37, 1119–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Nyongesa, M. K. , Ssewanyana, D., Mutua, A. M., Chongwo, E., Scerif, G., Newton, C. R., & Abubakar, A. Assessing executive function in adolescence: A scoping review of existing measures and their psychometric robustness. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10, 423374. [Google Scholar]

- Peruzzini, M. , Grandi, F., & Pellicciari, M. Exploring the potential of Operator 4.0 interface and monitoring. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 139, 105600. [Google Scholar]

- Poncet, F. , Swaine, B., Dutil, E., Chevignard, M., & Pradat-Diehl, P. How do assessments of activities of daily living address executive functions: a scoping review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 2017, 27, 618–666. [Google Scholar]

- Quintano, R. J. KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF CALL CENTER INDUSTRY IN DAVAO CITY. Ignatian International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research 2024, 2, 639–655. [Google Scholar]

- Riepenhausen, A. , Wackerhagen, C., Reppmann, Z. C., Deter, H.-C., Kalisch, R., Veer, I. M., & Walter, H. Positive cognitive reappraisal in stress resilience, mental health, and well-being: A comprehensive systematic review. Emotion Review 2022, 14, 310–331. [Google Scholar]

- Rindermann, H. , Kodila-Tedika, O., & Christainsen, G. Cognitive capital, good governance, and the wealth of nations. Intelligence 2015, 51, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, R. M. , Isquith, P. K., & Gioia, G. A. (2005). Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function®--Adult Version. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology.

- Saha, R. Mapping competence requirements for future shore control center operators. Maritime Policy & Management 2023, 50, 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E. , Ali, D., Wilkerson, B., Dawson, W. D., Sobowale, K., Reynolds III, C., Berk, M., Lavretsky, H., Jeste, D., & Ng, C. H. A brain capital grand strategy: toward economic reimagination. Molecular Psychiatry 2021, 26, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spencer, J. P. The development of working memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2020, 29, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprang, G. , Ford, J., Kerig, P., & Bride, B. Defining secondary traumatic stress and developing targeted assessments and interventions: Lessons learned from research and leading experts. Traumatology 2019, 25, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Tessitore, F. , Caffieri, A., Parola, A., Cozzolino, M., & Margherita, G. The role of emotion regulation as a potential mediator between secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in professionals working in the forced migration field. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 2266. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D. , Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54, 1063. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. , Guo, T., Tang, T., Shi, B., & Luo, J. Role of creativity in the effectiveness of cognitive reappraisal. Frontiers in Psychology 2017, 8, 1598. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H. , Huang, S., & Lv, L. A multilevel analysis of job characteristics, emotion regulation, and teacher well-being: a job demands-resources model. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 2395. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D. , Isic, A., Bechtoldt, M., & Blau, P. What is typical for call centre jobs? Job characteristics, and service interactions in different call centres. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2003, 12, 311–340. [Google Scholar]

- Zito, M. , Emanuel, F., Molino, M., Cortese, C. G., Ghislieri, C., & Colombo, L. Turnover intentions in a call center: The role of emotional dissonance, job resources, and job satisfaction. PloS One 2018, 13, e0192126. [Google Scholar]

| Researcher(s) | Theoretical Contribution | Related Cognitive Skill |

|---|---|---|

| (Koskina & Keithley, 2010) | Exploration of the role of emotions and emotional experiences of individuals in call centers of small and medium enterprises | Emotions and Affects |

| (Cai & Lin, 2011) | Examination of the relationship between call center operators' emotions and their performance | |

| (Saha, 2023) | Identification of the skills required for coastal control operators in the future | Cognitive Resilience |

| (Kaasinen et al., 2020) (Peruzzini et al., 2020) | Clarification of the role of coping with negative job conditions on operators' performance | |

| (Koole & Li, 2023) | Exploration of the role of adaptability skills in difficult working conditions for operators | |

| (Li et al., 2020) | Clarification of the role of self-control on mental health and performance of hospital operators during the COVID-19 pandemic | |

| (Fantinelli et al., 2023) (Körner et al., 2019) | Explanation of the impact of perceived stress on the performance of call center operators and the need to train operators in stress-reduction skills | Perceived Stress |

| (Berardi et al., 2021) | Systematic review of tools for measuring executive functions in children and adults | Weakness in Executive Functions |

| (Poncet et al., 2017) | Scoping review of the role of daily activity assessments on executive functions | |

| (Nyongesa et al., 2019) | Scoping review identifying dimensions of executive functions and their assessments in adults | |

| (Spencer, 2020) (Lemonaki et al., 2021) | Development of the concept of working memory and its impact on employee performance | |

| (Cristofori et al., 2019) | Identification of dimensions of executive functions and clarification of the role of planning in performance | |

| (Tessitore et al., 2023) | Impact of training emotion regulation skills on operators' stress, mental pressure, and performance | Emotion Regulation |

| (Guarino et al., 2020) | Introduction of cognitive control skills as an executive function dimension and its role in employee performance | |

| (Riepenhausen et al., 2022) | Systematic review clarifying the role of positive cognitive reappraisal on resilience, mental health, and employee wellness | |

| (Wu et al., 2017) | Clarification of the role of cognitive reappraisal skills on creativity and individual performance | |

| (Kujala & Lappi, 2021) | Explanation of the impact of attention and concentration disorders on employees' performance in complex and challenging work conditions | Lack of Attention and Concentration |

| (Nagata et al., 2019) | Identification of dimensions of attention and concentration disorders and their effects on work engagement, psychological work environment, and employees' psychological distress | |

| (Gül et al., 2017) | Clarification of the relationship between cognitive slowing and mental fatigue in employees under challenging working conditions |

| Performance Components | Description | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Daily Break Time | Average time spent by each operator on breaks per day | MeanBreak |

| Leave Count | Number of days each operator took off in a month | Leave |

| Received Calls | Number of calls answered by each operator during their shift in a month | Calls_Received |

| Average Talk Time | Average duration of each call | Mean_Talk |

| Successful Call Percentage | Ratio of calls converted to services out of total calls | Call_To_Service |

| Working Days | Days the operator completed their shifts | Days_In |

| Active Login Time | Time the operator is logged in and ready to take calls | Login_Time |

| Number of Errors | Number of errors (e.g., improper referrals, failed calls) each operator had over a specified period (month) | Errors |

| Transferred Call Percentage | Percentage of calls that the operator could not answer and transferred to another operator, relative to total received calls | Percent_Call_Transferred |

| Missed Call Percentage | Percentage of calls that an operator was unable to answer compared to total received calls | Percent_Call_Missed |

| Hold Time | Duration that the operator kept a call on hold | Hold_Time |

| Average Talk Duration | Average time spent by each operator on each call | Mean_Talk |

| Cancellation Ratio to Service | Ratio of the number of canceled services by the operator to successful services | Cancel_To_Service |

| Cancellation Ratio to Call | Ratio of the number of canceled services by the operator to total received calls | Cancel_To_Call |

| Cognitive Skill | Sub-dimensions | Measurement Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Emotions and Feelings: Encompasses a range of pleasant (e.g., joy) and unpleasant (e.g., stress) emotions that impact performance. | Positive emotions: Experience of pleasant feelings like joy and compassion. | PANAS Questionnaire (Watson et al., 1988) |

| Negative Emotions: Experience of unpleasant emotions like stress and anger. | ||

| Perceived Stress: Assesses the stress-inducing nature of life situations, focusing on the frequency and intensity of stress-related thoughts | PSS Questionnaire (Cohen et al., 1983) |

|

| Cognitive Resilience: Refers to the ability to adapt and recover from challenges, evaluating stress tolerance and emotional stability. | Personal Competencies: Belief in one's capacity to manage challenges effectively. | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (RISC) (Connor & Davidson, 2003) |

| Adaptability and Tolerance to Negative Effects: Capacity to adjust to changing environments and uncertainties. | ||

| Positive Acceptance of Changes: Mindset towards change and uncertainty. | ||

| Control and Regulation: Ability to regulate thoughts and emotions in response to challenges. | ||

| Spiritual Impact: Sense of meaning and connection to something greater. | ||

| Executive Functions: Addresses cognitive processes enabling planning, organizing, and problem-solving; covers a range from self-control to self-regulation. | Initiation: Ability to independently undertake tasks without procrastination. | Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) (Roth et al., 2005) |

| Working Memory: Temporary storage for retaining and manipulating information. | ||

| Planning and Organization: Ability to structure plans and set priorities effectively. | ||

| Activity Monitoring: Ability to evaluate performance and progress towards goals | ||

| Emotion Regulation: This skill assesses an individual's strategies for managing and effectively changing their emotional experiences and expressions in various situations. | Cognitive Reappraisal: Reframing situations to modify emotional impact. | Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) (Gross & John, 2003) |

| Cognitive Suppression: Suppression of external emotional expressions. | ||

| Attention and Concentration: Evaluated through inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and cognitive slowing, all of which impact individual and organizational performance. | Inattention: Difficulties in maintaining attention and organization. | Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (BAARS) (Barkley, 2011) |

| Hyperactivity: Excessive motor activity and inner restlessness affecting focus. | ||

| Impulsivity: Acting without consideration of consequences or inability to delay gratification. | ||

| Cognitive Sluggish: Experiences of mental fatigue and sluggishness in cognitive processes. |

| Variable | Registration Operators (n = 15) |

Support Operators (n = 13) |

Total (n = 28) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean Age | 30 | 29.5 | 30.2 | 0.668 |

| Age Range | 22 to 46 | 19 to 46 | 19 to 46 | |

| Gender (n) | 0.274 | |||

| Female | 5 | 7 | 12 | |

| Male | 10 | 6 | 16 | |

| Marital Status (n) | 0.934 | |||

| Married | 6 | 5 | 11 | |

| Single | 9 | 8 | 17 | |

| Education (n) | - | |||

| High School Diploma | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 11 | 9 | 20 | |

| Work Experience (years) | ||||

| Mean Experience | 2.96 | 2.03 | 2.53 | 0.412 |

| Experience Range | 1 to 16 | 1 to 5 | 1 to 16 |

| Skill | Skill Dimension | Relationship with Registration Operator Performance | Relationship with Support Operator Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | Positive Emotion Experience | No relationship observed | Fewer errors (59%) / Less active presence time (51%) - not significant |

| Negative Emotion Experience | No relationship observed | Less break time (56%) / Fewer missed calls (61%) | |

| Balance of Positive and Negative Emotions | No relationship observed | Fewer errors (56%) | |

| Cognitive Resilience | Competence and Individual Ability | Less waiting time (51%) | Fewer errors (53%) - not significant |

| Individual Instincts and Tolerance of Negative Impacts | More break time (51%) | More missed calls (56%) | |

| Positive Acceptance of Change and Strong Relationships | Fewer calls to service ratio (61%) | More missed calls (72%) | |

| Control and Restraint | More active presence time (61%) | No relationship observed | |

| Spiritual Influence | No relationship observed | No relationship observed | |

| Total Cognitive Resilience Score | No relationship observed | More missed calls (54%) - not significant | |

| Perceived Stress | Perceived Stress | No relationship observed | No relationship observed |

| Executive Function Weakness | Initiative | Fewer errors (50%) - not significant | More average talk time (60%) |

| Working Memory | More waiting time (60%) | Fewer calls received (71%) / More average talk time (64%) | |

| Planning and Organizing | No relationship observed | Fewer calls received (59%) / More average talk time (62%) | |

| Task and Activity Monitoring | No relationship observed | No relationship observed | |

| Total Executive Function Weakness Score | More waiting time (57%) | Fewer calls received (59%) / More average talk time (62%) | |

| Emotion Regulation | Cognitive Reappraisal | Less talk time (64%) / Fewer calls to service ratio (76%) / More break time (55%) | No relationship observed |

| Cognitive Restraint | Fewer calls to service ratio (50%) - not significant / More break time (59%) | No relationship observed | |

| Total Emotion Regulation Score | Less talk time (64%) / Fewer calls to service ratio (73%) / More break time (66%) | No relationship observed | |

| Attention Deficit and Focus | Attention Deficit | More waiting time (58%) | No relationship observed |

| Hyperactivity | No relationship observed | No relationship observed | |

| Impulsivity | Less talk time (53%) | No relationship observed | |

| Cognitive Sluggishness | More waiting time (55%) | Fewer missed calls (52%) - not significant / Fewer transferred calls (51%) - not significant | |

| Total Attention Deficit and Focus Score | No relationship observed | No relationship observed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).