Introduction

Drug repurposing has multiple advantages over drug discovery, including saving time (~10+ years), cutting costs ($1 billion+) (Chong and Sullivan 2007; Scannell et al. 2012; Nosengo 2016), and increasing patient safety by including drugs that have already completed the extensive FDA-approval safety requirements. Additionally, this approach addresses the unmet need to treat conditions without currently approved and targeted therapeutics by leveraging existing therapies for new applications, particularly useful for rare diseases without financial support for novel drug discovery (Roessler et al. 2021). Here, we refer to drug repurposing as determining potential novel therapeutic uses for previously FDA-approved compounds and medications. While there are impediments to overcome with respect to drug repurposing for patented drugs (e.g., market exclusivity), pharmaceutical companies may need additional incentives to repurpose existing drugs (Breckenridge and Jacob 2019; Begley et al. 2021). While some previous studies may also describe this process as repositioning and/or prioritizing drugs, for clarity, we will consistently use the term “repurposing” to refer to identifying already approved drugs for new indications and the term “prioritization” to describe a major step in this repurposing process where investigators select the most promising drugs for follow-up experiments. Specifically, here, prioritization refers to the step after candidate drugs or targets are identified by any one of various drug repurposing techniques, where the list of potential candidates is further refined to identify those with the greatest potential for clinical translation.

Several helpful reviews have already underscored the utility of drug repurposing (Oprea et al. 2011; Pushpakom et al. 2019; Parvathaneni et al. 2019), exemplifying how to apply drug repurposing methods (Jin and Wong 2014) and describing current techniques for repurposing using computational and transcriptomic data (Park 2019; Kwon et al. 2019). However, high attrition rates during clinical trials are a known issue in drug development for multiple reasons, including negative drug safety profiles, lack of efficacy, and poor pharmacokinetic profiles (e.g., lipophilicity) (Waring et al. 2015). However, due to the growth and popularity of drug repurposing – the number of publications in PubMed for "drug repurposing" increased from 0 in 2003 to 237 in 2023 (Pubmed, accessed October 2024) and 30-35% of new FDA approvals are because a compound was repurposed (Krishnamurthy et al. 2022) – there is a need for a review to optimize target prioritization using considerations that address current drug attrition rates and common pitfalls (Pushpakom et al. 2019; Palve et al. 2021), so that is our goal here.

There are multiple advantages to enhancing drug target prioritization in the context of drug repurposing. Here, “targets” refer to the proteins or molecules (e.g., genes/nucleic acids, proteins, metabolites) a drug acts on for the intended therapeutic effect(s). Depending on how the drug was discovered or designed, it could interact with a specific molecular target (i.e., the intended drug target) or have unintended effects (i.e., off-targets) throughout the body that can serve as valuable mechanisms to treat different conditions or to understand adverse events. For example, statins are known to target and inhibit one specific protein, HMG-CoA reductase (Sirtori 2014). In turn, statins reduce the production of cholesterol, leading to downstream changes in the expression of dozens to hundreds of genes and proteins to treat high blood pressure and other cardiovascular conditions (Sirtori 2014). Notably, this class of drugs has also been repurposed to treat cancer through many potential downstream mechanisms of action (Jiang et al. 2021). Another example is metformin, the first-line drug for treating diabetes mellitus (Foretz et al. 2019, 2023), which has multiple known targets that it either activates and/or inhibits (Zhou et al. 2022), affecting many downstream genes, proteins, and pathways. As nothing in biology acts in isolation, some of these downstream effects could potentially alleviate the molecular consequences of other disease conditions (e.g., metformin is in clinical trials to treat Fanconi anemia in children (Pollard et al. 2022), making metformin a promising drug candidate for many repurposing applications. Therefore, it is pivotal to differentiate between these known, unintended, and downstream targets (i.e., target modalities). Some drug discovery philosophies aim to avoid drugs with multiple targets or off-target effects (polypharmacology) because they may increase the potential for unintended adverse events (Palve et al. 2021). However, drugs with more off-target effects may be leveraged for these same properties, as they modify different pathways, making them helpful for repurposing in conditions like cancer where it may be critical to target many pathways (Palve et al. 2021). For example, midostaurin was designed as a PKC inhibitor and FDA-approved for acute myeloid leukemia and systemic mastocytosis, but it has also been shown to be effective in non-small cell lung cancer cells due to its off-target effects on TBK1, PDPK1, and AURKA (Ctortecka et al. 2018). Some pathogen-targeting drugs also affect human intracellular gene products and can treat non-pathogenic conditions (Correia et al. 2021; Behroozi and Dehghanian 2024), like the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, which is commonly used for treating rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (Al-Bari 2015). While many investigators advance repurposing efforts for infectious diseases, this review will focus exclusively on non-pathogenic conditions.

Serendipitous findings (i.e., findings by chance) are responsible for many instances of drug repurposing, such as sildenafil (Viagra), a drug designed to treat cardiovascular disease, being repurposed to treat erectile dysfunction after its observed erectile side effects (Boolell et al. 1996). Additionally, the diabetes drug metformin has also been repurposed for cancer (Evans et al. 2005) and is now still being repurposed for new conditions through its inclusion in FDA-approved compound libraries. More recent approaches have leveraged high-throughput cell line drug screens with thousands of FDA-approved compounds to measure a specific impact (e.g., cell viability). Though these screening methods have historically still produced candidates with high failure rates in late-stage clinical trials (Astashkina et al. 2012), they also allowed programs such as PRISM to discover anticancer properties of non-oncology drugs (Corsello et al. 2020). The advent of omics (e.g., microarray, RNA-Seq, ATAC-Seq, mass spectrometry) has further propelled generating rich data facilitating more agnostic explorations of drug repurposing candidates because potential mechanisms do not need to be identified a priori (Park 2019; Kwon et al. 2019).

Further, using publicly available data to perform comprehensive analyses allows for the broader application of drug repurposing for diseases without an available therapy or needing improved therapies. In particular, because omics data captures the complexity of biological processes beyond traditional drug screening (e.g., cell death assays alone) and can capture drug perturbations in several metabolic and signaling pathways beyond hypothesis-driven targeted experimental designs. However, some notable resources exist for using omics data for drug repurposing, such as the Library of Integrated Network-Based Cellular Signatures (LINCS), a large-scale resource designed to understand how compounds can change gene expression across cell lines (Wang et al. 2016). Other newer gene-expression-based drug repurposing approaches frequently use hundreds to thousands of genes to develop drug and disease "signatures," which is beneficial because it presents a more holistic picture of a cellular phenotype (Lamb et al. 2006; Zhang and Gant 2009; Setoain et al. 2015; Jia et al. 2016; Chan et al. 2019; Duan et al. 2020; He et al. 2023; Wilk et al. 2023; Fisher et al. 2024b). These signatures, consisting of many representative genes for a condition, can help inform putative mechanisms of why a repurposed drug candidate may be effective. However, interpreting drug repurposing results from these signatures can be difficult. Methods that group similar genes, such as pathway analysis, may be helpful, but examining which genes are most weighted (i.e., which differentially expressed genes are most significant) in these signatures can also be beneficial. Still, systematically assessing the function and impact of these individual genes as inferred therapeutic targets is challenging for multiple reasons, including 1) these genes could be indirect targets (i.e., secondary, tertiary), 2) manual curation and interpretation of dozens to thousands of genes contributing to these signatures may be impractical due to time and other resource constraints, 3) a therapeutic effect could be the result of genes acting together in concert (e.g., a drug alters multiple targets/pathways or polypharmacology), and 4) signature gene lists vary in size depending on the dataset, condition, and computational parameters which may make manual assessment more challenging (Chan et al. 2019).

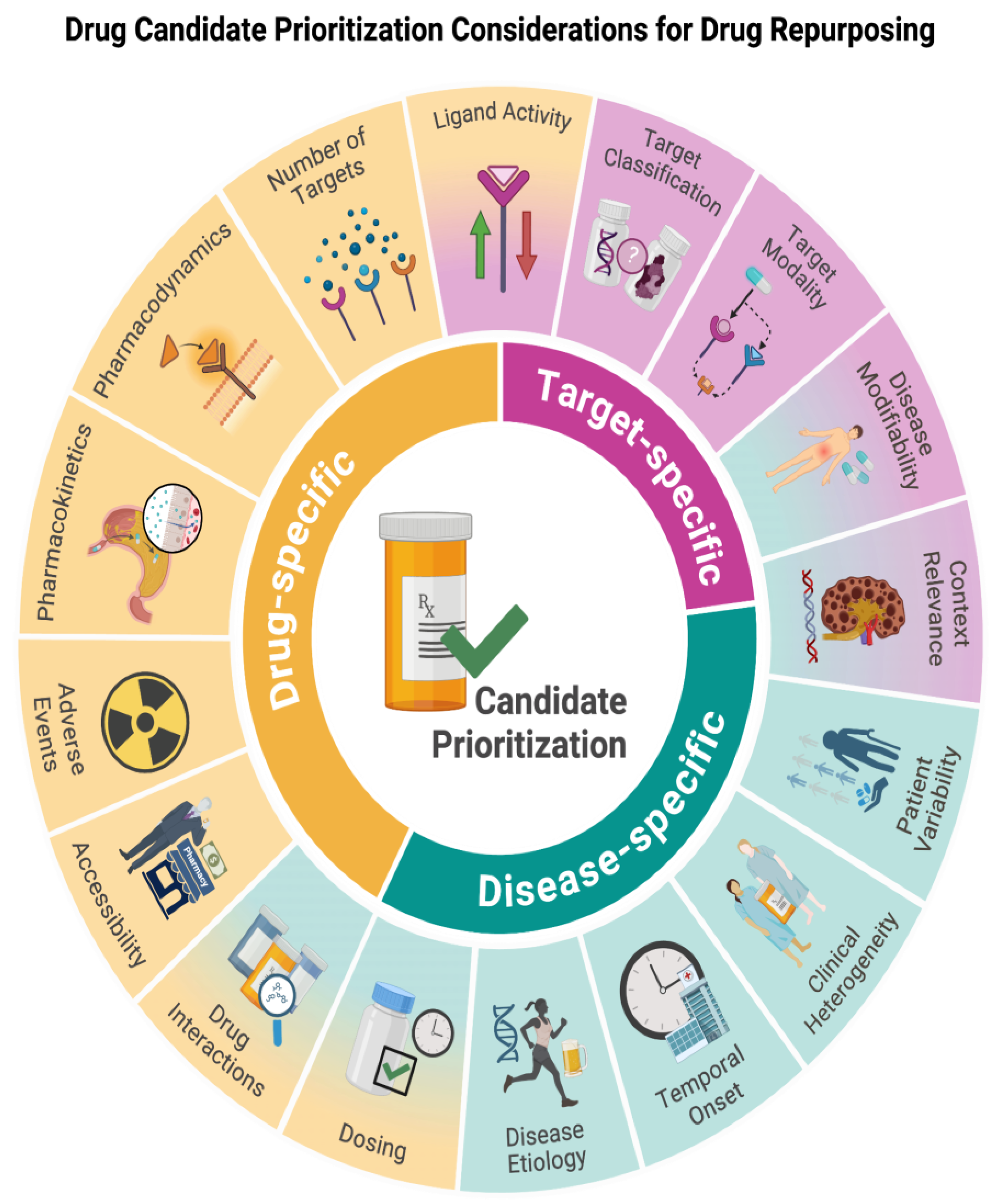

In this review, we survey and then recommend considering 1) drug-specific, 2) drug target/effector-specific, and 3) disease-specific (

Figure 1) features for prioritizing drug repurposing candidates and propose a workflow incorporating these principles. Currently, there is no standard workflow for assessing drugs and their targets after investigators have identified them through various drug repurposing identification methods. However, having a comprehensive workflow for preclinical and clinical trial prioritization is essential to minimize attrition rates, expedite the clinical adoption of novel therapies, and compare findings across contexts. Therefore, we propose a workflow the community can build on that incorporates all of these considerations for researchers to improve drug repurposing efforts and outcomes (

Discussion). Finally, we will discuss why this workflow matters and how this prioritization process parallels clinical considerations that medical prescribers evaluate. We will also discuss limitations and future directions, including with respect to rapidly developing technologies (e.g., machine learning for drug repurposing).

This figure overviews the three categories of considerations for prioritizing candidate drugs and their targets when drug repurposing. The background color indicates whether considerations belong to drug-, target-, or disease-specific categories.

Drug-Specific Considerations

When selecting drug targets for clinical reuse, it is helpful to remember considerations used in modern drug discovery. Many excellent reviews and tools have outlined some of these processes and considerations for identifying novel drug targets and candidate molecules (Drews 2000; Hughes et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2019; Emmerich et al. 2021). For example, an earlier review compiled pertinent considerations into the “Guidelines On Target Assessment for Innovative Therapeutics (GOT-IT)” recommendations (Emmerich et al. 2021). The GOT-IT recommendations are grouped into five assessment blocks that cover target-disease linkage, safety aspects, microbial/non-human targets, strategic issues, and technical feasibility. Considering these considerations when re-evaluating drugs for new disorders is critical, as various aspects of treatment (e.g., therapeutic concentration, duration of treatment, and target tissue specificity) may vastly differ between diseases/disorders. Here, we review the current state of the field and further build upon this framework to include information available once a drug has gone to market, such as drug interactions and side effects, and adapt drug discovery principles to drug repurposing candidates identified through omics approaches in our workflow of considerations (

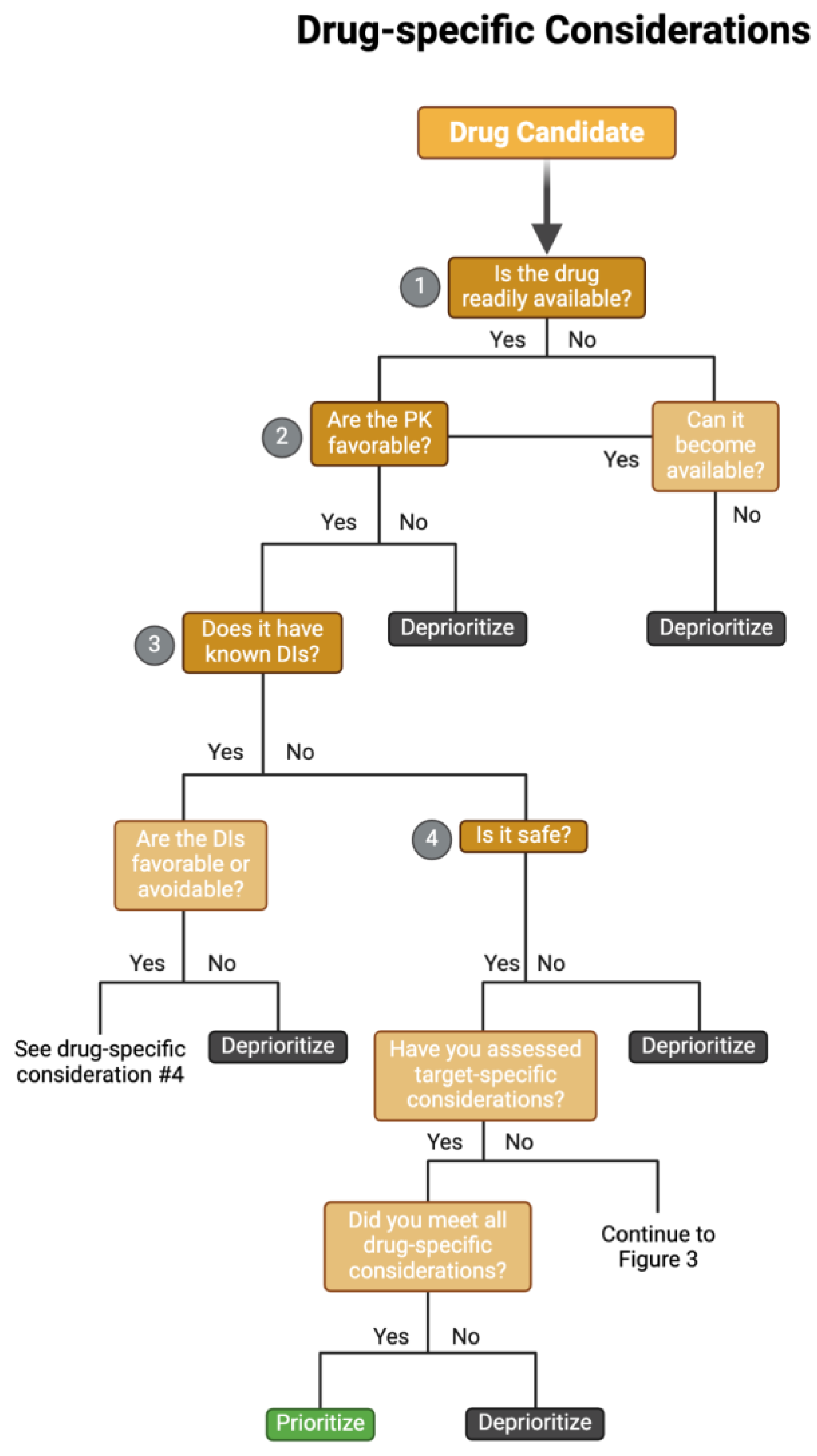

Figure 2).

A schematic overflow for prioritizing and de-prioritizing drugs and their targets for each drug-specific consideration. Please note: We have curated this workflow for simplicity, but investigators should refer to prior research and domain-specific knowledge to identify the nuances of their specific case. Abbreviations: PK = pharmacokinetics, DI = drug-drug interactions.

Evaluating Drug Safety

Drug safety is potentially the most critical consideration when prioritizing candidates, though investigations can evaluate it from various perspectives. Information concerning a drug's intended clinical use, class, pharmacokinetics (including bioavailability), documented adverse events, and mechanism of action factor into a drug’s safety profile. Prior studies have also reported successful predictions of adverse effects and complications using gene expression data (Wang et al. 2016) and from manual drug label curation and a natural language processing model (OnSIDES (Tanaka et al. 2024). An additional consideration concerning safety profiles for drug repurposing candidates is to avoid negative drug-drug interactions, discussed below in “Patient variability.”

A significant benefit of repurposing known drugs and drug targets is that FDA-approved (or other regulatory agency-approved) drugs have more information than novel compounds (i.e., they have preclinical and clinical trial documentation), and ongoing market presence also enables continued safety data collection (Krishnamurthy et al. 2022). Using FDA-approved drugs allows investigators to access publicly available data regarding a drug’s pharmacology, efficacy, and safety by leveraging previous data from successful and failed clinical trials, even if previous works have not tested that drug in a particular disease of interest. Despite this data accessibility, prioritizing candidates still has several challenges (Pushpakom et al. 2019), including collecting and interpreting the collected data across sources. For prioritizing drug-specific safety, much of the FDA-approved drug safety profile information comes from a combination of phase II-IV clinical trial data (each trial includes dozens to thousands of human subjects; available on ClinicalTrials.gov, and from reports of adverse events in the public (available in FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)). Additionally, some groupings of adverse events of drugs are more frequent with certain classes of therapeutic indications, presenting an opportunity for drug repurposing by examining which adverse events could be of benefit for other therapeutic indications (Zhang et al. 2013; Palve et al. 2021) or avoiding side effects (Morris et al. 2024).

Candidate Drug Accessibility

Practical access to a drug refers to both if it is readily available (i.e., over-the-counter, prescription, if it has controlled access) and its financial cost, with more accessible drugs often being favored for treatment (Gronde et al. 2017). Accessibility for drugs ranges from over-the-counter (unregulated usage) to prescription-based (approved by FDA, EMA, etc.) to controlled substances (schedules I-V) to non-approved. Likewise, if two drugs are comparable (e.g., in their predicted efficacy for a particular condition and safety profile), it is more prudent to prioritize the less expensive drug for downstream preclinical and clinical trials. Additionally, candidate drugs that have a higher likelihood of substance use disorder (e.g., schedule I and II controlled substances) may be de-prioritized compared to candidates that are less likely to be misused recreationally. However, some scheduled drugs have been successfully repurposed, such as ketamine (originally an anesthetic) being approved for major depressive disorder (MDD) in 2019 (Shin and Kim 2020). While databases must be frequently updated (e.g., when drugs are withdrawn from the market), resources such as Epocrates, a paid clinician-focused software started in 1998 that is available through most academic research institutions (Bhanot and Sharma 2017), help guide prioritizations concerning access since they can provide information about drug cost and availability. Governing bodies can also regulate the price of specific medications, increasing accessibility by easing patients' financial burden (Gronde et al. 2017). For example, insulin, a drug essential for diabetes mellitus that had steeply rising costs (Tseng et al. 2020), had out-of-pocket costs capped at $35 USD for seniors on Medicare in the United States in 2023, helping millions of Americans (The White House 2023).

Determining Drug Targets

Determining and evaluating drug targets for a given drug is an intricate process, as drug targets are not always known, and additional targets can also be found after a drug goes to market. Identifying the existence and multitude of targets can be complex, as some drugs have only one known target (e.g., statins), and other drugs have multiple targets (e.g., NSAIDs) (Zhou et al. 2022). Further, 18% of FDA-approved drugs are without a well-documented mechanism of action (e.g., acetaminophen/paracetamol, metformin) for a given indication, and 7% have no known primary target (e.g., lithium) (Gregori-Puigjané et al. 2012), though with further research scientists may be able to determine more therapeutic mechanisms. Many experimental approaches identify drug targets during the drug development stage, including direct biochemical methods (e.g., affinity purification, affinity chromatography, metabolic labeling, chemical labeling), genetic interactions, or computational inference (Schenone et al. 2013). Investigators can query this collected information (i.e., prior drug development research, clinical trial data, prior databases) in various databases and literature searches to determine if a drug has any known targets with databases such as DrugBank (Wishart et al. 2018), PHAROS (Sheils et al. 2021), SmartGraph (Zahoránszky-Kőhalmi et al. 2020), and The Therapeutic Target Database (Zhou et al. 2022). For example, PHAROS is an excellent web interface that facilitates browsing the Target Central Resource Database (Sheils et al. 2021). It contains multitudes of information about known and predicted targets for FDA-approved drugs and other relevant details, such as ligand activity (e.g., IC50, Ki, EC50, and Kd), for each target, if available (Sheils et al. 2021). Other resources, such as the Broad Institute’s Drug Repurposing Hub (Corsello et al. 2017), also provide a database of thousands of drugs with information, including their statuses in clinical trials, mechanisms of action, and known targets. Literature searches on PubMed or Google Scholar can also identify targets for more obscure or novel medicines that large databases may not have included or find newly identified targets after a drug has had an extended market presence. Finally, some drugs do not have known targets or mechanisms of action. If there are no known drug targets for a drug of interest, one can skip direct target identification and examine the biological properties (i.e., protein type, pathways involved) of genes most perturbed in omics experiments following drug treatment, such as RNA-seq (Kwon et al. 2019). Studying the known properties of some of these highly differentially expressed effectors can give insights into how the drug acts within the body or if any drug targets can be inferred.

Target-Specific Considerations

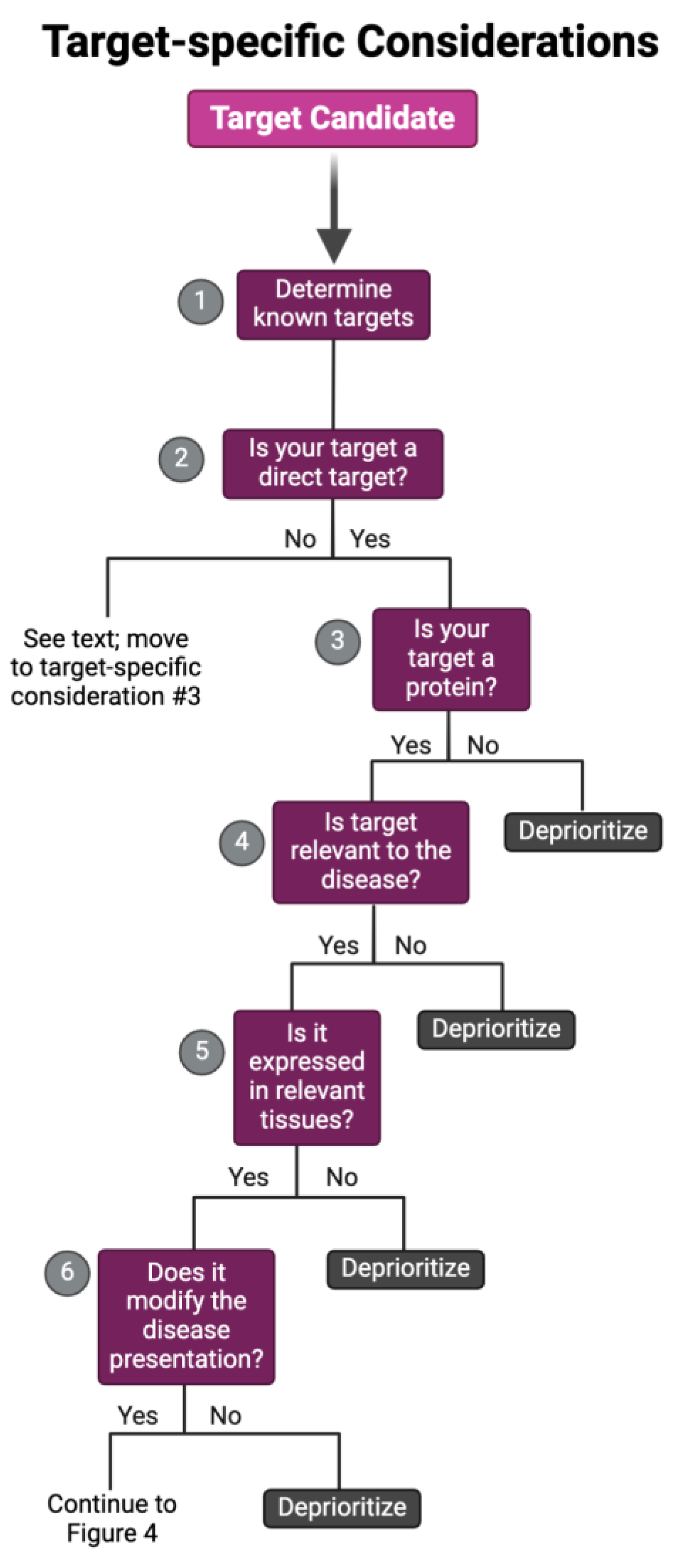

The specific target that a repurposing candidate binds to achieve a therapeutic response can be characterized by two main factors: target classification and target modality. Target classification refers to the type of biological molecule a drug candidate binds (e.g., nucleic acid, protein, etc.). In contrast, target modality defines the mode of action a target elicits for a therapeutic response (e.g., direct target, off-target, or downstream effector). Each of these distinctions influences the drug’s metabolic, safety, and efficacy profiles (Palve et al. 2021; Behroozi and Dehghanian 2024; Debisschop et al. 2024), which can lead to the deprioritization of candidates, especially in instances where combination therapy may be required. For example, a candidate that produces its therapeutic effect via an off-target mechanism may have reduced potency compared to its direct one, requiring a dosage beyond its FDA-approved range (Palve et al. 2021; Xia et al. 2024). In such cases, the candidate might require pairing with another drug targeting the same disease mechanism to achieve a synergistic effect via combination therapy (Jia et al. 2009; Ayoub 2021; Flanary et al. 2023; Xia et al. 2024; Kandasamy et al. 2024), which may lead to deprioritization after considering other candidates and available resources. Thus, we recommend investigators analyze these target-specific characteristics, as outlined in the following sections, to aid in further categorization, enabling efficient prioritization of candidates that align optimally with their study objectives (

Figure 3).

A schematic overflow for prioritizing and de-prioritizing drugs and their targets for each target-specific consideration. Please note: We have curated this workflow for simplicity, but investigators should refer to prior research and domain-specific knowledge to identify the nuances of their specific case.

Target Classification

This review primarily classifies drug targets into two categories: nucleic acids and proteins. While drugs target other classes, such as metabolites or metals, drug repurposing studies mainly include medications that target nucleic acids or proteins (Oprea et al. 2011; Pushpakom et al. 2019; Pantziarka et al. 2021; Pascual-Gilabert et al. 2023). Further, nucleic acid- and protein-targeting drugs report distinct characteristics that affect drug activity (i.e., pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics) and response (i.e., safety and efficacy) (Buddolla and Kim 2018; Tan et al. 2020; Palve et al. 2021; Perez et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2022), which can affect the candidate prioritization process as shown in

Figure 3.

Candidates targeting nucleic acids (e.g., antisense oligonucleotides or ASOs) are known to directly modulate gene expression, mRNA splicing, and transcriptional and epigenetic regulation to produce a therapeutic response (Tan et al. 2020; Kulkarni et al. 2021). The benefits of nucleic acid-targeting drugs stem primarily from their capacity to precisely bind causal targets of disease pathogenesis, even targets that were once considered “undruggable” (Buddolla and Kim 2018; Tan et al. 2020). For instance, ASOs use oligonucleotides to directly bind RNA to knock down, upregulate, or modify the expression of pathogenic RNAs. In various cancers, microRNAs (miRNAs), short regulatory RNAs, are reported to be dysregulated, and ASOs provide the opportunity to target them (e.g., Cobomarsen inhibits miR-155, found to be elevated in leukemias and lymphomas) and other targets that were previously identified as “undruggable” (Hammond 2015; Bartolucci et al. 2022). This is an exciting avenue in therapeutics, but ASOs’ target precision can make it difficult to identify uses outside of its original indication. The potential repurposed indication must have similar pathways involved in pathogenesis as its original indication (e.g., repurposing an ASO initially indicated for T-cell lymphoma for B cell-lymphoma) (Bartolucci et al. 2022; Lauffer et al. 2024). Further, several challenges remain when using nucleic acid-targeting drugs, including poor bioavailability, lack of in vivo stability, unpredictable off-targets, and high immunogenicity (Buddolla and Kim 2018; Ingle and Fang 2023). These drugs may not exhibit beneficial drug response profiles (i.e., high efficacy, low safety concerns) compared to current FDA-approved protein-targeted drugs (Meng and Lu 2017; Buddolla and Kim 2018; Tan et al. 2020; Andreana et al. 2021). In addition, given their recent development, ongoing studies are still exploring their application and addressing concerns regarding the delivery system to prevent early degradation, unintended immune activation, and toxic off-target effects (Jackson and Linsley 2010; Buddolla and Kim 2018).

Nucleic acid-targeting drugs are more commonly investigated in drug discovery projects than in repurposing studies. As such, there are limited resources to guide researchers in evaluating this class of medications for repurposing studies. However, the precision of nucleic acid-targeting drugs still holds promise for future repurposing efforts, particularly for conditions still needing disease-modifying therapy (i.e., monogenic, cancerous, and autoimmune conditions). Current repurposing studies for nucleic acid-targeting drugs are primarily in the exploratory phase, especially for ASOs, and the pre-clinical phase for nucleic acid-targeting antimicrobials (Andreana et al. 2021; McDowall et al. 2024; Evans et al. 2024). For example, furamidine, a diamine compound indicated for parasitic infections (i.e., an antimicrobial), was evaluated as a repurposing candidate for myotonic dystrophy type 1 in in vivo (i.e., mouse models and patient-derived myotubes) and in vitro analyses, rescuing the mis-splicing events event pivotal for disease pathogenesis (Jenquin et al. 2018, 2019; Andreana et al. 2021, 2022). Furamidine’s ability to bind the CTG•CAG repeat expansion, the leading cause of myotonic dystrophy type 1, with favorable safety profiles compared to other repurposing candidates, such as pentamidine (i.e., the parent drug of furamidine), positions it as a promising candidate for treating this rare monogenetic disease (Jenquin et al. 2018, 2019; Andreana et al. 2021, 2022; Hicks et al. 2024). Though this example implies a favorable outcome, the nuances associated with this target classification (i.e., nucleic acid-targeting drugs) implicate several challenges, as outlined here. Hence, we recommend deprioritizing nucleic acid-targeting drugs unless all other candidates are known to be less safe and efficacious after evaluating them using our proposed framework (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Protein-targeting drugs typically bind and modulate the activity of proteins involved in the biological pathways associated with their original indications (Bakheet and Doig 2009). However, drugs may perturb more pathways outside of that indication. While most drug discoveries are made to target a specific protein, the target protein or biological pathway in which it acts may not exclusively cause the therapeutic effect (i.e., off-targets and downstream effectors may also contribute) (Feng et al. 2017). Each target protein potentially perturbs relevant biological pathways, contributing to the drug’s therapeutic response (Yu et al. 2020; Palve et al. 2021). Given their long history in therapeutic management, protein-targeted drugs are often preferred in repurposing studies over nucleic acid-targeted ones (Oprea et al. 2011; Pushpakom et al. 2019; Pantziarka et al. 2021; Pascual-Gilabert et al. 2023). Thus, there are several resources to guide investigators in identifying and prioritizing candidates with this target classification (i.e., protein-targeting drugs) (

Table 1).

Table of considerations one should make when repurposing FDA-approved drugs. We have denoted resources requiring login credentials or a subscription with asterisks.

To assist in repurposing protein-targeted drugs, we recommend using resources like The SIGnaling Network Open Resource (Signor), which integrates information from numerous other databases (e.g., pathway commons, DrugBank) between pathways, proteins, drug molecules, stimuli, and phenotypes to infer putative directionality and causality (Lo Surdo et al. 2023). Thus, Signor and similar resources can further enable investigators to identify the molecular mechanisms potentially driving a therapeutic effect. With their extensive documentation, increasingly growing body of work, and greater generalizability across conditions, we recommend protein-targeted over nucleic-targeted drugs for repurposing efforts.

Target Modality

For drug candidates with a well-defined mechanism of action, there could also be several targets beyond its documented or primary mechanism (Schenone et al. 2013; Jenquin et al. 2018; Kuenzi et al. 2019; Palve et al. 2021). In drug repurposing, the ability to use these indirect targets (i.e., off-targets and downstream effectors) for therapeutic management is increasingly being studied (Palve et al. 2021); however, compared to direct targets, off-targets and downstream effectors may exhibit less favorable safety-efficacy profiles (Chartier et al. 2017; Palve et al. 2021), which may require additional validation analyses or downstream deprioritization if that is the case (

Figure 3). Here, we explore how defining a repurposing candidate’s target modality as a direct target, off-target, or downstream effector can guide investigators in further refining their drug candidate list.

Drug discovery initiatives typically design their drugs to bind direct targets to produce a therapeutic effect; though not explicitly, these drugs can also modulate off-targets and downstream effectors through pleiotropy, gene-gene interactions, or cellular perturbations ((Cichonska et al. 2015; Palve et al. 2021). Given the indirect mechanisms influencing the effects of off-targets and downstream effectors, their use in repurposing candidates requires additional analyses to ensure the target candidate is not a product of technical noise (Polamreddy and Gattu 2019; Aittokallio 2022). Prior works began identifying off-target effects through drug repurposing analyses to reveal promising candidates (Talevi and Bellera 2020; Palve et al. 2021; Begley et al. 2021). Specifically, targeting off-targets for drug repurposing has been incredibly beneficial, especially for multifactorial and multi-systemic conditions, such as cancer. For example, midostaurin – initially indicated as a protein kinase C inhibitor for solid tumors – has been approved to be repurposed for its off-target FLT3 in FLT3 mutated acute myeloid leukemia and for its off-target KIT in systemic mastocytosis and mantle cell lymphoma (Palve et al. 2021). In addition, imatinib, developed initially to inhibit BCR-ABL in chronic myeloid leukemia, was also clinically approved to be repurposed for its off-target KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (Palve et al. 2021).

Employing off-targets for repurposing could also be applied to other heterogenous disorders (Kuenzi et al. 2019; Palve et al. 2021; Xia et al. 2024). Though, repurposing studies using off-targets have also reported reduced efficacy at the FDA-approved dosage range; thus, combination therapies that produce a synergistic effect, especially for cancer studies, have been recommended (Kuenzi et al. 2019; Palve et al. 2021; Flanary et al. 2023). Without the inclusion of combination therapies, the low efficacies associated with indirect therapeutic targets at current FDA-approved dosages may not be sufficient for researchers to prioritize a given drug candidate. Accordingly, distinguishing between these target modalities (when possible) will help investigators determine whether pursuing molecules are appropriate for their disease of interest.

Target- and Disease-Specific Considerations

Reported attrition in drug repurposing trials is primarily due to safety and/or efficacy concerns (Pushpakom et al. 2019). While we discussed above how investigators can evaluate the safety of their target candidates (

Figure 2), this section will emphasize how investigators can ensure their target is efficacious. Several works have identified repurposing candidates at the pre-clinical level (Palve et al. 2021; Lago and Bahn 2022; Doshi and Chepuri 2022; Duan et al. 2024; Huang et al. 2024); however, efficacy (i.e., how well a drug elicits its therapeutic effect) remains a concern when assessing candidates during clinical trials (Pushpakom et al. 2019). While attrition in clinical trials may be due to insufficient statistical power from limited sample sizes (Ng et al. 2024), we recommend investigators further explore the target-disease interactions (i.e., how the target can modulate disease-specific pathways) to lower that attrition and better prioritize promising candidates for subsequent clinical studies (Greene and Voight 2016; Issa et al. 2021; Mottini et al. 2021; Lago and Bahn 2022). To further streamline this process, we describe a candidate’s target-disease interactions by its context relevance (i.e., a target’s reported involvement in the investigated disease’s pathogenesis and pathophysiology) and its disease-modifying ability (i.e., the extent to which a target’s modulation produces its therapeutic effect). Accordingly, researchers should take caution in deprioritizing candidate drugs that do not produce favorable target-disease interactions.

Context Relevance

Context relevance refers to the biological factors and interactions pertinent for ameliorating pathogenesis and pathophysiology, resulting in the observed phenotype (e.g., variants producing an underexpression or overexpression of proteins, enzymes involved in disease-specific pathways, interactions between pathways yielding a syndromic presentation, etc.). Determining the context relevance of a target through prior works, publicly available resources, and evidence-based hypotheses can minimize the gap between experimental findings and clinical outcomes (Oprea and Mestres 2012). Essential resources include UniProt (UniProt Consortium 2023) and the Human Protein Atlas’ Druggable Proteome, which assess a protein’s expression and druggability, respectively (Uhlén et al. 2015). Further, there are resources to identify which pathways a specific gene and/or its products are involved in (e.g., Pathway Commons compiles and integrates information from various sources (Rodchenkov et al. 2020). In addition to these, there are numerous resources to assist investigators in ensuring their repurposing candidates’ targets have context relevance, which we have curated into a list in

Table 1. Here, we continue to highlight the importance of assessing context relevance for repurposing efforts and provide solutions to potential challenges that one may encounter when doing so (i.e., working with rare diseases and/or isoform targets).

Prior repurposing studies have typically ensured a target’s context relevance by evaluating whether their candidate is perturbing disease-relevant pathways (Correia et al. 2021; Palve et al. 2021). GWAS and resources alike (

Table 1) have been repeatedly used throughout in silico repurposing studies to identify novel targets, which provides excellent opportunities, especially for conditions without treatment. For example, a recent repurposing study that identified potential repurposing candidates for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a rare neurodegenerative disease, used GWAS data to identify “druggable” genes that contained variants associated with developing ALS, including TBK1, TNFSF12, and GPX3. Though they identified multiple genes beyond these three, this study only reported that fostamatinib, amlexanox, BIIB-023, RG-7212, and glutathione were associated with those specific three genes (Duan et al. 2024). This study exemplifies how context relevance can enable the identification of potential candidates; however, pre-clinical analyses warrant further validation via in vivo and in vitro studies to validate its candidacy for subsequent phases. Further, resources such as varsome (Kopanos et al. 2019), gnomAD (Karczewski et al. 2020), ClinVar (Landrum et al. 2014), and GWAS Catalog (Sollis et al. 2023) contain information about a putative drug target’s known variants, and disease associations to ensure its disease relevance

(Table 1). Drugs chosen for repurposing clinical trials have gone through robust pre-clinical experimentation and exhibit meaningful evidence to confirm their promising candidacy (Pantziarka et al. 2021). Hence, we recommend that researchers first evaluate target-disease interactions and then add disease-specific clinical information (described below in

Disease-specific considerations) to facilitate clinical adoption (i.e., FDA approval for the new indication).

Rare diseases, however, may have limited scientific findings regarding prominent targets involved in pathogenesis and pathophysiology (Polamreddy and Gattu 2019; Huang et al. 2024; Ng et al. 2024). When resources specific to the investigated disease are available, it would be best for repurposing efforts to use them in their analyses to ensure a candidate’s context relevance (

Table 1). As demonstrated by Huang et al., including relevant pathophysiological information from conditions similar to ones with limited data in a drug repurposing model enhances repurposing efforts for rare and ultra-rare conditions. Thus, to overcome challenges due to lack of data/information (e.g., ultra-rare diseases and diseases without identified causative genes), we recommend researchers investigate conditions with similar phenotypic presentations, those involved in similar pathways, and/or those with similar physiologic behavior (Huang et al. 2024).

Furthermore, a repurposing candidate’s ability to target various isoforms of the same gene or protein also applies to a target’s context relevance. Information about the number of annotated isoforms for a given gene can be accessed with resources such as Ensembl (Harrison et al. 2024) and GENCODE (Frankish et al. 2019). However, the specific isoform a target binds to may vary depending on drug dosage or target tissue specificity. For example, the effectiveness of the cancer drug bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A) antibody, in colorectal carcinoma, can be inhibited by the VEGF-A isoform VEGF165b through competitive binding (Varey et al. 2008). Both VEGF165 and VEGF165b isoforms can be found in colorectal cancer (i.e., VEGF165 is found in rapidly growing colonic cells and VEGF165b slow-growing colonic cells); however, tumors with upregulated VEGF165b expression and down-regulated VEGF165 exhibit reduced efficacy profiles when treated with bevacizumab, indicating that differences in isoform expression can affect drug response) (Varey et al. 2008). Therefore, we recommend researchers determine whether they can obtain and integrate any isoform-specific information (e.g., identifying whether a candidate’s binding affinity changes with different isoforms) through literature searches or in vitro experimentation to improve their repurposing analyses. For example, a prior study leveraged isoform coexpression networks and gene perturbation signatures from LINCS to identify promising drug targets for breast cancer (Ma et al. 2019). In addition, to further assist with this effort, we have provided isoform-relevant resources in

Table 1.

Disease-Modifying Effect

For repurposing studies seeking to identify drug candidates with therapeutic potential, analyses should confirm that the candidate modulates the target-disease interaction to produce a disease-modifying effect (Pushpakom et al. 2019). Determining the mechanism behind the drug target’s disease-modifying effect demonstrates its capability to counteract disease pathogenesis, thus predicting a repurposing candidate's therapeutic and preventative potential (i.e., efficacy). We recommend that investigators evaluate a repurposing candidate’s target-disease interaction to confirm that it produces the desired therapeutic effect by analyzing the disease-relevant pathway and signature modulation data through publicly available resources (

Table 1). Pathway Commons (Rodchenkov et al. 2020) and Gene Ontologies (Harris et al. 2004), when combined with rigorous validation analyses, are examples of resources one can use to ensure a candidate drug modifies the desired disease mechanisms. We advise investigators to deprioritize a candidate whose target does not have sufficient evidence of disease-specific modifying effects. Further, to predict a candidate’s ability to elicit a disease-modifying effect, investigators should explicitly identify cell types and tissues involved in disease progression (Floris et al. 2018; Begley et al. 2021). Prior studies have used cell-type and tissue-specific specificity to identify novel biomarkers (Zhou et al. 2018; van Dam et al. 2018; Zhao et al. 2020; Yuhan et al. 2022; Qiu et al. 2023; Shao et al. 2023), essential for identifying disease mechanisms responsible for pathogenesis. In addition, investigations should provide evidence that their candidates have the appropriate chemical composition to reach the relevant cell types and tissues (e.g., the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier for neurological conditions).

Identifying relevant cell types may require referring to data from prior available studies if it is not apparent from the phenotypic presentation alone. For example, cardiac diseases (e.g., heart failure) cause several phenotypic and physiologic changes across organ systems involved in fluid balance (e.g., kidneys), and, therefore, many therapies are designed to manage symptoms and fluid balance (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers, etc.) (Castiglione et al. 2022). However, recent studies highlighting approaches for identifying novel biomarkers in cardiac disease report major cell types involved in key disease mechanisms include cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, pericytes, immune cells, neuronal and glial cells, and adipocytes (Miranda et al. 2023). By recognizing cell types involved in disease pathogenesis, one can identify the most specific “druggable” biomarkers (Miranda et al. 2023). In this case, repurposing efforts for cardiac disease should ensure their candidate causes a favorable disease-modifying effect in the particular cell types involved in pathogenesis and pathophysiology (e.g., cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts), ultimately preventing the presence and/or progression of clinically presented fluid imbalance.

Tissue-specific effects for the investigated disease should also be accounted for when prioritizing candidates. When included in repurposing analyses, tissue-specific effects, in addition to cell type effects, provide evidence a candidate can manipulate disease-relevant pathways that can be used to predict efficacy (Floris et al. 2018); thus, those candidates should be prioritized. Investigators can evaluate tissue-specific relevancy of targets via expression in non-diseased tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project (GTEx Consortium 2013), the Human Protein Atlas (Uhlén et al. 2015), and the Chan Zuckerberg CellxGene Discover platform, which allows users to access numerous gene expression datasets across organs and cell types with an easy-to-use data portal (CZI Single-Cell Biology Program et al. 2023). Organ system-specific resources include the Allen Brain Cell Atlas (Yao et al. 2023), which consists of human and mouse brain data in a user-friendly portal that can be explored, queried, and analyzed. Further, to evaluate a repurposing candidate’s ability to modify the disease, researchers have also integrated information from 20 datasets, biorepositories, and ontologies into the Precision Medicine Knowledge Graph (PrimeKG), which includes diseases, drugs, genes, proteins, exposures, phenotypes, drug side effects, molecular functions, cellular components, biological processes, anatomical regions, and pathways (Chandak et al. 2023). PrimeKG has also been leveraged by researchers to power drug repurposing models such as TxGNN, which improves prediction accuracy for indication by almost 50% compared to eight other methods (Huang et al. 2024).

Disease-Specific Considerations

Repurposing candidates identified using biological signatures has proven efficacious in in silico and in vivo preclinical testing (Alavi and Ebrahimi Shahmabadi 2021; Baek et al. 2022; Gaber et al. 2024; Ng et al. 2024); however, several repurposing candidates have failed in clinical trials due to decreased therapeutic efficacy and severe adverse effects (Polamreddy and Gattu 2019; Begley et al. 2021; Aittokallio 2022; Pinzi et al. 2024). While we have previously discussed how attrition could be due to insufficient sample sizes, there are also clinical drivers (e.g., disease heterogeneity, population variability, etc.) that can play a role in downstream clinical attrition of promising pre-clinical candidates (Masnoon et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2022; Fisher et al. 2024a; Huang et al. 2024; Ng et al. 2024).

While biological signatures and predictive models are representative of a condition, they cannot fully recapitulate the disease phenotype and context (Huang et al. 2024), contributing to increased attrition rates in clinical trials. For instance, a clinical condition’s disease phenotype may be localized to the brain. Still, many drug repurposing approaches do not discern if a repurposed drug compound can cross the blood-brain barrier. Therefore, if the condition’s tissue of interest differs from a drug candidate’s initially indicated disease tissue of interest, extra care must be taken to ensure that the drug can properly travel to the new tissue and, if not, be deprioritized. Further, FDA-approved drugs possess appropriate safety-efficacy profiles for their indication. Yet, several drug repurposing candidates currently indicated for a specific type of disease (e.g., neurological conditions) are reported to be promising in pre-clinical studies (i.e., in vivo, in vitro, and/or in silico studies) in another type of disease (e.g., gastrointestinal disorder) have failed downstream (e.g., validation analyses, clinical data evaluations, clinical trials) (Krishnamurthy et al. 2022). For example, in an in silico repurposing study, topiramate, an anticonvulsant, was identified as a promising repurposing candidate via signature reversion (i.e., an in silico approach) for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Dudley et al. 2011; Pushpakom et al. 2019). To support topiramate’s relevance to IBD, the researcher identified gene sets through their functional enrichment analysis related to the pathophysiology of IBD (e.g., nuclear factor KB (NF-KB) signaling, inflammation, and antigen presentation) (Dudley et al. 2011). Further, rat models validated its ability to treat IBD-damaged colons (Dudley et al. 2011; Pushpakom et al. 2019; Silva et al. 2022). However, a large retrospective cohort study (n=1731) using clinical data (i.e., diagnoses, prescription records, demographics, reported procedures, hospitalizations, etc.) to evaluate the effects of topiramate on patients with IBD, revealed that topiramate, in combination with established IBD therapy (e.g., methotrexate), did not benefit patients (i.e., they did not experience fewer diseases flares, hospitalizations, and surgeries compared to those who did not take it)(Crockett et al. 2014). This finding does not negate topiramate’s ability to combat inflammatory conditions, as a prior study reported its neuroprotective effects against neuroinflammation (Bai et al. 2022). However, it suggests that there may be clinical drivers, in addition to biological drivers (described above in the “Context relevance” section), resulting in the discrepancy between a drug's original use and the current condition under study. Thus, we recommend that investigations consider all the disease-specific considerations, as outlined in this section, when prioritizing candidates.

In addition, as an effort to include clinically representative information relevant to their studied disease, repurposing studies are increasingly leveraging publicly available clinical data (

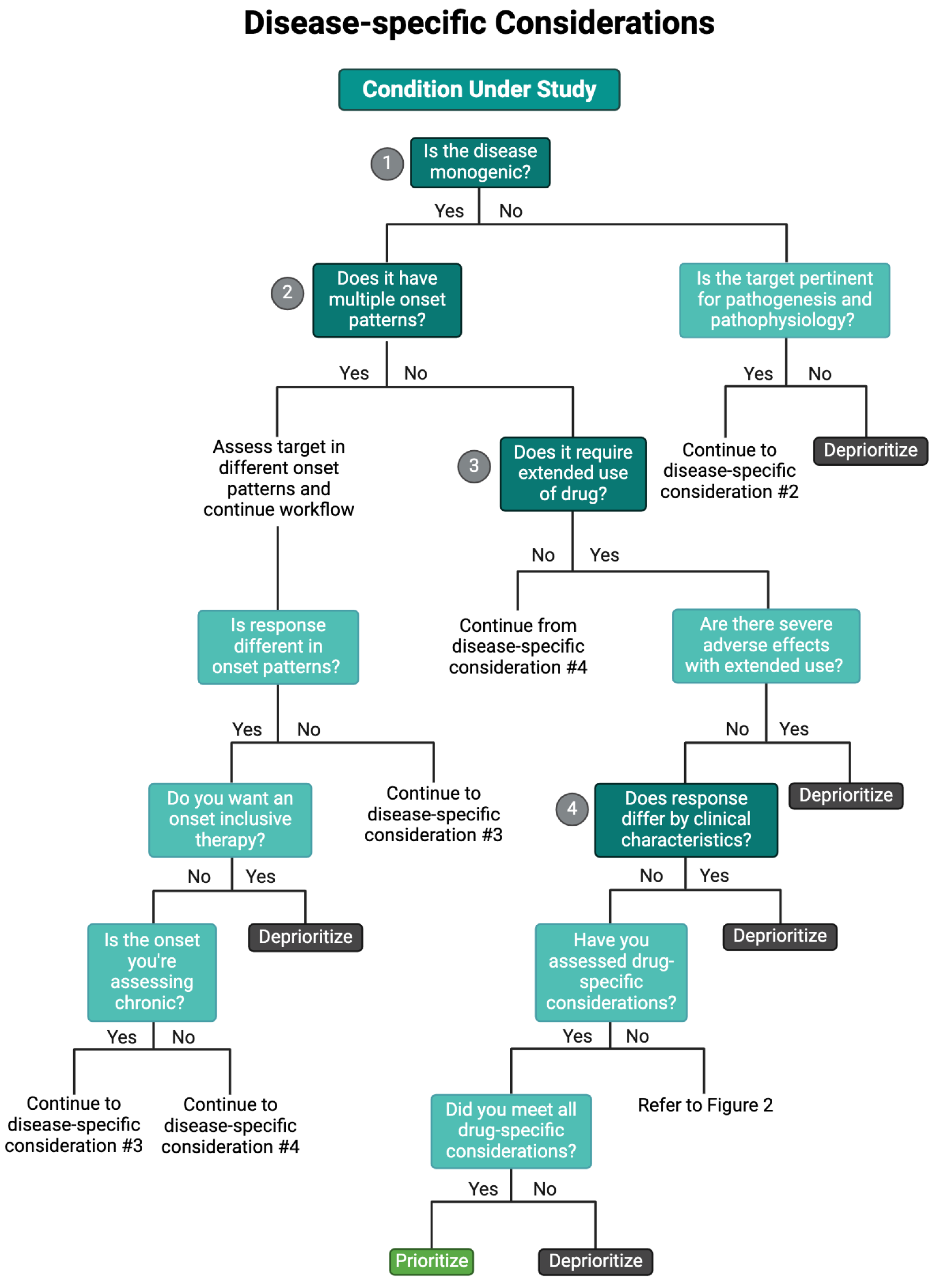

Table 1) when prioritizing candidates (Issa et al. 2021; Tan et al. 2023). As such, we recommend investigators apply our proposed disease-specific considerations when prioritizing candidates, as they are representative of the clinical factors affecting the disease pathogenesis and pathophysiology at the biomolecular level (Huang et al. 2024); some of these considerations have even reported distinguishing between favorable and non-favorable safety-efficacy profiles in drug discovery and/or repurposing efforts (Fisher et al. 2022; Lago and Bahn 2022). Specifically, we recommend evaluating the disease etiology, temporal onset, clinical heterogeneity (i.e., the variation in processes, responses, or outcomes in a condition’s phenotype and common comorbidities), pertinent clinical variables, potential polypharmacy interactions, and predicted dosing for their condition under study (

Figure 3). Further, we recommend applying these key clinical considerations using our workflow to prioritize candidates identified by pre-clinical repurposing analyses subsequent to evaluating candidates in our Target-specific Considerations workflow (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

A schematic overflow for prioritizing and de-prioritizing drugs and their targets for each of the disease-specific considerations. Please note: We have curated this workflow for simplicity, but investigators should refer to prior research and domain-specific knowledge to identify the nuances of their specific case.

Disease Etiology

Often, conditions are distinguished by their etiology as monogenic (i.e., Mendelian diseases) or multifactorial (i.e., polygenic and complex diseases). Monogenic conditions typically have a well-defined genetic basis (even when the mechanism is unknown) where variants can lead to protein dysfunction (altering its regulation and/or activity, leading to pathogenic accumulation, insufficient production, or altered activity), manifesting the observed phenotype. Therefore, for monogenetic conditions, investigators should consider prioritizing candidates that target the specific pathogenic pathway. However, when repurposing drugs for monogenetic diseases, investigations may face challenges in finding databases with sufficient information to effectively evaluate candidates, especially concerning monogenetic conditions that exhibit clinical heterogeneity (discussed below in “Clinical heterogeneity”) with multiple comorbidities that can differ amongst patients with the disease (e.g., polycystic kidney disease). For example, ultra-rare Mendelian conditions like Schinzel Gideon Syndrome have limited knowledge of the full scope of the pathophysiological variant effects, posing unique challenges (Crooke 2021; Whitlock et al. 2023; Jones et al. 2024). These conditions may necessitate larger patient cohorts for clinical trials as described for multifactorial conditions, though acquiring the required cohort size poses a greater challenge and may not be possible.

Compared to monogenic conditions, multifactorial/polygenic conditions arise from a complex interplay between genetic, epigenetic, and/or environmental factors (e.g., anxiety disorders) (Meier and Deckert 2019). This complexity can complicate target prioritization as target candidates may fail to address all integral mechanisms involved, rendering them less efficacious in clinical trials (Ng et al. 2024). Additionally, multifactorial disorders generally have more mixed treatment responses, as patients may be responders or non-responders (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) resistance in major depressive disorder) (Xu et al. 2024; Ng et al. 2024). Accordingly, multifactorial conditions often necessitate larger sample sizes and data that include clinical information (described below in the “Clinical heterogeneity” and “Patient variability” sections) to further prioritize candidates. However, this presents an even bigger challenge for diseases that are both rare and multifactorial, especially those with complex pathogenicity and clinical heterogeneity (e.g., IgA Nephropathy) (Ng et al. 2024).

Temporal Onset

Temporal onset differences can influence therapeutic effectiveness and toxicity, making onset a principal consideration when selecting targets for personalized interventions. We describe temporal onset as the temporal dynamics of pathogenesis (e.g., acute, chronic) as opposed to age of onset, which falls under clinical specificity. Although onset variability is a clinical feature, it can reveal significant biological consequences related to pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and complications. In addition, both types of onset may manifest within the studied conditions, and clinical trials have shown that patient responses vary based on presentation onset (Lago and Bahn 2022). For instance, drugs like verapamil, nilvadipine, and nifedipine were tested on patients with acute and chronic schizophrenia (a multifactorial disorder), revealing that chronic patients often displayed inconsistent therapeutic responses (Lago and Bahn 2022). Presentation onset can also guide investigators in predicting complications that occur with short or long-term use, deprioritizing those drugs unfavorable for their studied disease’s presentation.

Acute illness presentation studies should also determine whether candidates require tapering dosage before stopping treatment by referring to prior identified safety characteristics (

Table 1). Abrupt discontinuation can pose a risk for downstream complications if the patient does not adhere to the therapeutic plan diligently (e.g., corticosteroids causing adrenal insufficiency). Cases where patient compliance is unsuccessful, potentially causing adverse reactions, can be alleviated by monitoring and ensuring patient compliance. Likewise, patients have also demonstrated sudden cessation due to financial barriers or physical barriers hindering them from receiving their medication such as lack of transportation – a challenge for both acute and chronic onsets. Chronic presentations requiring extended use of drugs face particular challenges with side effects because they may become more likely with extended usage. For example, in drug repurposing initiatives for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), researchers may deprioritize candidates with risks of hepatotoxicity (e.g., valproic acid, methotrexate, azathioprine, etc.), as liver dysfunction is a known complication of ADPKD (Cnossen and Drenth 2014; Wilk et al. 2023). However, extended-use hepatotoxic candidates for conditions requiring acute management, such as cancers, might still be considered, as the therapeutic benefit may outweigh the risk.

Clinical Heterogeneity

Here, we define clinical heterogeneity as the variation in processes, responses, or outcomes in a specific condition’s phenotype and common comorbidities, which is known to complicate therapeutic intervention. This variation (i.e., associated comorbidities, phenotype, temporal onset, etc.) has been reported to cause difficulty for drug discovery and repurposing initiatives due to potential candidates failing to exhibit desired safety-efficacy profiles. In addition, clinical heterogeneity differs from population variability regarding the differences seen amongst the patient population with the studied disease. In contrast, we define population variability as the general population's characteristics (i.e., not for a specific condition) that can lead to differences in drug response, which we discuss in the subsequent section.

Clinical heterogeneity is a concern for most conditions; however, rare conditions with well-documented clinical heterogeneity (e.g., autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, IgA Nephropathy, etc.) exacerbate issues in obtaining sufficient data to evaluate repurposing candidates. However, these rare, clinically heterogeneous conditions also represent those with the greatest need for personalized therapies, as current management is generally geared toward symptomatic relief. For example, IgA Nephropathy, an autoimmune glomerulonephritis disease with familial and/or sporadic origin, is known to exhibit clinical heterogeneity (e.g., variable presence of recurrent macroscopic hematuria, hypertension, older age, etc.), complicating the identification of potential repurposing candidates (Yu and Chiang 2014; Cheung and Barratt 2016; Ng et al. 2024). When mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), an immunosuppressant indicated for multiple autoimmune conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic sclerosis, etc.), was evaluated in clinical trials to be repurposed for IgA Nephropathy (Ng et al. 2024), there were conflicting results. Specifically, a clinical trial repurposing MMF in IgA Nephropathy with 170 participants (85 that received MMF and 85 that did not) revealed that the patients that were administered MMF (1.5 g/d for 12 months and subsequent 0.75-1.0 g/d for at least 6 months) exhibited reduced disease progression (i.e., decreased annual loss in eGFR) in comparison to the participants that did not receive it (Hou et al. 2023; Ng et al. 2024). However, other clinical trials with smaller participant sizes (i.e., 34 and 44 participants) reported MMF did not benefit renal function/outcome (i.e. eGFR) and proteinuria (Maes et al. 2004; Hogg et al. 2015; Ng et al. 2024). Though participant cohort size is a concern for the latter trials mentioned, the associated clinical heterogeneity with IgA Nephropathy complicates the identification of potential treatments (Ng et al. 2024). Thus, if available, we advise investigations to obtain sufficient data (i.e., larger sample sizes, inclusion of relevant clinical information, etc.) to identify promising candidates, prioritizing those predicted to be most inclusive in effectively treating patients with that disease.

Clinical heterogeneity is not unique to rare Mendelian diseases. Notably, cancer is incredibly heterogeneous at the clinical level; however, many successful repurposing candidates exist (Sleire et al. 2017; Palve et al. 2021; Pantziarka et al. 2021). This success can primarily be due to several initiatives geared toward explicitly identifying the shared foundational mechanisms (e.g., uncontrolled cell growth) that lead to its phenotypic presentation (Hanahan and Weinberg 2000, 2011; Hanahan 2022). Keeping this in mind, we recommend that investigations confirm that a candidate’s target exhibits context relevance, as described previously, and that the necessary data and information via the literature be obtained to account for clinical heterogeneity.

Patient Variability

Repurposing studies should consider relevant patient variables, specifically clinical characteristics and potential polypharmacy usage, and then prioritize candidates with decreased biases or drug interactions. Clinical factors such as sex, patient age, comorbidities, and drug-relevant metabolic enzymes affect drug efficacy and toxicity. For example, sex biases in efficacy and adverse events emphasize the need for prioritized candidates to be effective in both sexes (Yu et al. 2016; Watson et al. 2019; Fisher et al. 2022; Unger et al. 2022). To determine if a targeted gene is sex-biased in expression, one can use the publicly available GTEx resource (GTEx Consortium 2013) or the list of sex-biased genes from Oliva et al.’s GTEx-based work (Oliva et al. 2020), as well as assess disease-specific datasets. Our group, for example, has also identified sex-biased gene expression and regulation of sex-biased adverse event-associated drug targets by leveraging the FAERS and GTEx databases (Fisher et al. 2024a), potentially revealing molecular mechanisms driving sex-biased adverse drug events.

Likewise, age implicates pharmacokinetic alterations in behavior due to physiologic changes such as decreased body water, muscle mass, and serum albumin, typically in older individuals (Volpi et al. 2004; Jéquier and Constant 2010; Cabrerizo et al. 2015; Manirajan and Sivanandy 2024). Across development and aging, resources exist to determine when a gene is expressed, such as the BrainSpan Atlas of Developing Human Brain (Miller et al. 2014) and Open Genes, which is a searchable list of aging and longevity-associated genes (Rafikova et al. 2024). Comorbidities often contraindicate several potential drugs, making it necessary to assess drug candidates' safety in patient populations. For instance, conditions with comorbidities, such as liver and kidney disease, are contraindications for several drugs, including acetaminophen and ACE Inhibitors/ARBs, respectively (Kuan et al. 2023). Furthermore, polymorphisms in relevant drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYP450 family) are common (Preissner et al. 2013) and complicate target prioritization. These polymorphisms can reduce efficacy or increase toxicity, requiring specific dosage requirements. Thus, candidates known to be metabolized by common polymorphic enzymes should be deprioritized. Advantageously, researchers have developed resources such as PharmVar, PharmGKB, and PharmCAT to annotate the associations with variants in drug-metabolizing genes and drug responses (Sangkuhl et al. 2020; Gaedigk et al. 2021; Whirl-Carrillo et al. 2021). These variables can alter the response to target candidates, and investigators should deprioritize drugs that do not include the general patient population.

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy, while not a patient characteristic, contributes to patient variability, as it may result in adverse drug interactions and influence safety (Masnoon et al. 2017). Specifically, polypharmacy describes a patient's concurrent use of multiple (5 or more) medications (Novak et al. 2022). As the risk of developing medical conditions requiring pharmaceutical treatment increases with age, elderly patients are more at risk of being victims of polypharmacy-caused interactions (Masnoon et al. 2017; Novak et al. 2022). For instance, AD is overwhelmingly more common in older patients. Hence, the likelihood of AD patients taking multiple drugs is much higher, and polypharmacy-caused drug interactions are more critical to consider. Pharmacodynamic interactions can lead to synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effects (Chou 2022), while pharmacokinetic factors can alter absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion, all of which directly influence drug response (Takimoto 2001). For example, the simultaneous administration of NSAIDs with ACE Inhibitors causes antagonistic effects, reducing the ability of ACE Inhibitors to lower blood pressure effectively (Ishiguro et al. 2008; Fournier et al. 2012; Albishri and MBCh 2013). One strength of repurposing FDA-approved drugs is the catalog of known drug interactions and documentation of adverse events (

Table 1). This principle can benefit the patient, as some drug combinations are synergistic and can be computationally predicted (Sun et al. 2016; Cheng et al. 2019; Flanary et al. 2023). However, predicting synergistic drug-drug interactions can be difficult before clinical administration (Aittokallio 2022; Weth et al. 2024). Investigators with a comprehensive understanding of patient variability can predict the optimal balance between repurposing candidates' safety, efficacy, and applicability for the best clinical outcomes.

Dosing

We recommend that pre-clinical analyses take further initiatives to capture the optimum dosage or administration (e.g., oral, injection) to achieve the necessary therapeutic effect (Begley et al. 2021; Huang et al. 2024). Additional measures to predict and validate the required dosage or administration before clinical trials highlight the greater effort to provide clinical trial initiatives with invaluable results to select those drugs, making candidates more reputable compared to others for selection. This information will also allow refinement of prioritization for candidates whose dosages or administrations are intolerable, ineffective, or not clinically available (Emmerich et al. 2021; Begley et al. 2021; Xia et al. 2024). For example, repurposing drugs with highly severe side effects, like cancer drugs, for non-terminal conditions (e.g., neurodevelopmental disorders, rheumatoid arthritis) would offer little benefit because the side effects would cause more significant impairments than the condition itself. In light of the extensive progress prior works have made regarding the availability and feasibility of retrospective clinical data (e.g., electronic health records, clinical trial data, and drug databases), investigators can extract relevant information, especially off-label indications and safety profiles of repurposing candidates, for repurposing studies (Tan et al. 2023; Huang et al. 2024; Debisschop et al. 2024; Ng et al. 2024).

Discussion

Applying a structured workflow for candidate and target prioritization will streamline drug repurposing efforts and further bridge the gap between promising preclinical candidates and successful clinical adoption. Here, we have reviewed and categorized these considerations for target prioritization as 1) drug-, 2) target-, and 3) disease-specific (

Figure 1). Additionally, we developed a comprehensive workflow (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) to address challenges and reduce attrition as previously documented (Cha et al. 2018; Pushpakom et al. 2019; Polamreddy and Gattu 2019; Pantziarka et al. 2021; Huang et al. 2024). This workflow has two main starting points: starting with a candidate drug identified through drug repurposing or starting with a potential therapeutic target identified through other experiments. From there, we suggest the researcher move through each step carefully and refer to our Table of Resources (

Table 1) to answer each specific question (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) before moving on to the next category of considerations. Finally, we encourage all researchers to examine the disease-specific considerations to ensure the candidate drug and/or its targets are a worthwhile path forward for further testing and validation. These considerations and structured workflow will guide investigators in making sound decisions to identify promising and robust candidates for their studied condition.

We have also developed this workflow to parallel the clinician decision-making process when prescribing therapeutic management. Specifically, a clinician’s decision-making process for management carefully adheres to drug safety, efficacy, affordability, relevance to the condition, and patient-specific variables. These factors have been historically used for clinical therapeutic management (Keijsers et al. 2015). If candidate prioritization aligns with these factors driving clinical therapeutic management and selection, discrepancies between pre-clinical results and clinical utility can be minimized (Begley et al. 2021; Huang et al. 2024). In addition to candidate prioritization, our workflow guides researchers when deprioritization would be appropriate. We define deprioritization as the process of assigning lower priority to a candidate that does not meet crucial criteria, without excluding them entirely. This process allows investigations to favor candidates that better align with the criteria outlined in our proposed considerations (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Further, this workflow may also be useful for drug discovery projects to ensure the selection of robust candidates that can successfully progress to clinical trials (Begley et al. 2021). Maybe here for a sentence or two about what deprioritization means and doesn’t?

Drug repurposing includes in vivo, in vitro, in silico, and real-world data-driven approaches. Integrating these approaches could further lead to identifying robust targets and promising candidates (Aittokallio 2022; Talevi and Bellera 2020; Iwata et al. 2015). Previous studies have found that the failure of repurposing efforts is often due to decreased safety and efficacy profiles observed during clinical trials (Polamreddy and Gattu 2019). As a result, studies also strongly recommended that researchers rigorously validate their findings to ensure a repurposing candidate's clinical adoption (Begley et al. 2021), though validation processes are outside our scope.

Off-label use – prescribing therapies for non-FDA-approved indications (Saiyed et al. 2017) – is frequently mentioned in the context of drug repurposing efforts (Pushpakom et al. 2019; Begley et al. 2021; Huang et al. 2024). Clinicians typically refrain from prescribing medications off-label due to a lack of safety-efficacy profiles outside of FDA-approved indications and increased patient out-of-pocket costs (Saiyed et al. 2017; Pantziarka et al. 2021; Begley et al. 2021). However, patients or parents with children who have conditions without curative or preventative treatments may advocate clinicians to prematurely prescribe repurposing candidates before they have undergone rigorous testing, especially because the information is readily available on sources such as PubMed (Begley et al. 2021). While drug repurposing initiatives offer great potential, we recommend that investigators exercise diligence and prudence when performing and interpreting drug repurposing analyses and especially when publicly reporting their results. Further, compared to off-label use, drug repurposing enables existing drugs to be marked for multiple indications, increasing the likelihood that clinicians may prescribe that medication. FDA approval and evidence-based support remain essential in solidifying public trust in a given therapy (Pantziarka et al. 2021). Still, applying clinician reasoning, as used with off-label use, may benefit current drug repurposing models (Huang et al. 2024). Thus, we have devised our workflow to align with physician decision-making for administering treatment.

Advances in drug repurposing highlight the need to ensure and prioritize optimal drugs and targets. The application of machine learning (e.g., non-negative matrix factorization, neural networks, large language models, virtual gene knockout simulation) exhibits excellent promise for leveraging large datasets to find novel candidates for drug repurposing (Gimeno et al. 2019; Aittokallio 2022; Doshi and Chepuri 2022; Del Hoyo et al. 2023; Jonker et al. 2024; Yan et al. 2024; Pinzi et al. 2024; Messa et al. 2024; Huang et al. 2024; Qi et al. 2024) and to develop and refine automated prioritization. For example, ceSAR is a newly developed drug discovery and repurposing technique that uses machine learning to combine LINCS transcriptomic data with molecular docking simulations was able to identify novel inhibitors of the antiapoptotic target BCL2A1 (Thorman et al. 2024). However, there may be barriers regarding limited storage for massive model-training data, and these models may become more challenging to interpret. In addition, researchers are increasingly incorporating patient characteristics (e.g., age, sex, comorbidities, etc.) into public databases that can be leveraged in drug repurposing studies.

Drug repurposing exhibits excellent promise for researchers and clinicians to expand the therapeutic capabilities of FDA-approved drugs, saving billions of taxpayer dollars and time. Even so, the field must navigate adversities in limited accessibility to current drug databases requiring high subscription costs, non-reproducible models, and inaccessible tools for navigating retrospective clinical data (Pushpakom et al. 2019; Polamreddy and Gattu 2019; Begley et al. 2021; Aittokallio 2022). While we list many resources to help address drug-, target-, and disease-specific considerations when prioritizing candidates, we are still in the beginning stages of weighing, interpreting, and evaluating these massive amounts of data. Further, drug companies must continue to be incentivized (e.g., the Orphan Drug Act) to encourage research for repurposing already-successful drugs for rare diseases. For instance, business strategy reasons cause 46% of preclinical drugs to become shelved (Krishnamurthy et al. 2022), not biological reasons, exhibiting that researchers, clinicians, pharmaceutical companies, and regulatory officials must work together to promote rigorous drug research to improve drug repurposing efforts overall. Given these constraints, following the drug-, target-, and disease-specific considerations outlined here in combination with novel high-throughput data-based approaches will help address limitations in drug repurposing and identify efficacious and safe drug candidates for clinical reuse.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all members of the Lasseigne Lab for their thoughtful feedback. We would also like to acknowledge our funding sources: R01DK134310, U54OD030167, R01AG077536, and the PKD Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aittokallio, T. What are the current challenges for machine learning in drug discovery and repurposing? Expert Opin Drug Discov 2022, 17, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, S.E.; Shahmabadi, H.E. Anthelmintics for drug repurposing: Opportunities and challenges. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bari, M.A.A. Chloroquine analogues in drug discovery: new directions of uses, mechanisms of actions and toxic manifestations from malaria to multifarious diseases. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015, 70, 1608–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albishri, J.; MBCh, B. NSAIDs and hypertension. 2024. Available online: https://applications.emro.who.int/imemrf/Anaesth_Pain_Intensive_Care/Anaesth_Pain_Intensive_Care_2013_17_2_171_173.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Andreana, I.; Bincoletto, V.; Milla, P.; Dosio, F.; Stella, B.; Arpicco, S. Nanotechnological approaches for pentamidine delivery. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 1911–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreana, I.; Repellin, M.; Carton, F.; Kryza, D.; Briançon, S.; Chazaud, B.; Mounier, R.; Arpicco, S.; Malatesta, M.; Stella, B.; et al. Nanomedicine for Gene Delivery and Drug Repurposing in the Treatment of Muscular Dystrophies. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astashkina, A.; Mann, B.; Grainger, D.W. A critical evaluation of in vitro cell culture models for high-throughput drug screening and toxicity. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 134, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, N.M. Editorial: Novel Combination Therapies for the Treatment of Solid Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Kwon, S.H.; Jeon, J.Y.; Lee, G.Y.; Ju, H.S.; Yun, H.J.; Cho, D.J.; Lee, K.P.; Nam, M.H. Radotinib attenuates TGFβ -mediated pulmonary fibrosis in vitro and in vivo: exploring the potential of drug repurposing. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2022, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.-F.; Zeng, C.; Jia, M.; Xiao, B. Molecular mechanisms of topiramate and its clinical value in epilepsy. 2022, 98, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakheet, T.M.; Doig, A.J. Properties and identification of human protein drug targets. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, D.; Pession, A.; Hrelia, P.; Tonelli, R. Precision Anti-Cancer Medicines by Oligonucleotide Therapeutics in Clinical Research Targeting Undruggable Proteins and Non-Coding RNAs. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begley, C.G.; Ashton, M.; Baell, J.; Bettess, M.; Brown, M.P.; Carter, B.; Charman, W.N.; Davis, C.; Fisher, S.; Frazer, I.; et al. Drug repurposing: Misconceptions, challenges, and opportunities for academic researchers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabd5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behroozi, R.; Dehghanian, E. Drug repurposing study of levofloxacin: Structural properties, lipophilicity along with experimental and computational DNA binding. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, S.; Sharma, A. App Review Series: Epocrates. J. Digit. Imaging 2017, 30, 534–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boolell, M.; Allen, M.J.; Ballard, S.A.; Gepi-Attee, S.; Muirhead, G.J.; Naylor, A.M.; Osterloh, I.H.; Gingell, C. Sildenafil: An orally active type 5 cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. Int. J. Impot. Res. 1996, 8, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge, A.; Jacob, R. Overcoming the legal and regulatory barriers to drug repurposing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 18, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddolla, A.L.; Kim, S. Recent insights into the development of nucleic acid-based nanoparticles for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2018, 172, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrerizo, S.; Cuadras, D.; Gomez-Busto, F.; Artaza-Artabe, I.; Marín-Ciancas, F.; Malafarina, V. Serum albumin and health in older people: Review and meta analysis. Maturitas 2015, 81, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Collisson, E.A.; Mills, G.B.; Shaw, K.R.M.; Ozenberger, B.A.; Ellrott, K.; Shmulevich, I.; Sander, C.; Stuart, J.M.; The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglione, V.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Saccaro, L.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandak, P.; Huang, K.; Zitnik, M. Building a knowledge graph to enable precision medicine. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Wang, X.; A Turner, J.; E Baldwin, N.; Gu, J. Breaking the paradigm: Dr Insight empowers signature-free, enhanced drug repurposing. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2818–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartier, M.; Morency, L.-P.; Zylber, M.I.; Najmanovich, R.J. Large-scale detection of drug off-targets: hypotheses for drug repurposing and understanding side-effects. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha Y, Erez T, Reynolds IJ, et al (2018) Drug repurposing from the perspective of pharmaceutical companies: Drug repurposing in pharmaceutical companies. Br J Pharmacol 175:168–180.

- Cheng, F.; Kovacs, I.A.; Barabási, A.-L. Network-based prediction of drug combinations. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-A.; Yogo, E.; Kurihara, N.; Ohno, T.; Higuchi, C.; Rokushima, M.; Mizuguchi, K. Assessing drug target suitability using TargetMine. F1000Research 2019, 8, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung CK, Barratt J (2016) Is IgA Nephropathy a Single Disease? In: Pathogenesis and Treatment in IgA Nephropathy. Springer Japan, Tokyo, pp 3–17.

- Chong CR, Sullivan DJ Jr (2007) New uses for old drugs. Nature 448:645–646.

- Chou, T. Mathematical definitions of “additive effect of two (or more) drugs” and their synergism and/or antagonism based on mass-action law (MAL) algorithms for pharmacodynamics (PD), biodynamics (BD) and bioinformatics (BI) simulations. FASEB J. 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]