1. Introduction

Student Industry 5.0 emphasizes a human-centered approach to technological innovation, integrating advanced technologies like robotics with sustainability (Carayannis, 2022) and meaningful performance indicators. An important method to evaluate the performance of complex industry developments is based on the definition and calculus of specific key performance indicators (Tieber, 2019; Gheorghe, 2019). Industry 5.0 is a new paradigm that aims to humanize green technological innovation, social resilience, and sustainable industrial ecosystem development. It emphasizes supplier-customer interaction and knowledge spillovers along the sustainable supply chain. GTI indicators are classified into three levels: substantial, non-substantial, and overall (Chen, 2024). In this context, directional and applicative elements play critical roles, guiding and applying principles in specific, impactful ways. Industry 5.0 focuses on sustainability beyond environmental goals, incorporating social and economic aspects. It aims to optimize resource efficiency, circularity (Payer, 2024, Babkin, 2024), and social responsibility (Vukelić, 2024; Pereira, 2024) through ethical labor practices and community involvement. Sustainable supply chains prioritize local sourcing, reducing emissions, and using renewable resources. Application elements include closed-loop systems (Nikseresht, 2024), smart energy management (Sun, 2024), and eco-design (Beigizadeh, 2022), which use robotics, AI, and digital twins (Donmezer, 2023) to manage waste, monitor energy consumption, and minimize environmental impact in products throughout their lifecycle.

Robotics in Industry 5.0 focuses on collaborative automation, enhancing capabilities, safety, and productivity without replacing the human workforce. Robots are designed to assist humans in challenging tasks, fostering a more skilled workforce. They are versatile and adaptable, capable of performing customized production tasks with minimal downtime (Lou, 2023). Cobots, designed to work closely with humans in manufacturing, reduce ergonomic strain and increase output without extensive safety barriers (Pizoń, 2022). Autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) assist with internal logistics and robotic quality control, using AI-driven machine vision systems to inspect products in real time (Farooq, 2023). Industry 5.0 also focuses on performance indicators (KPIs) that capture social, environmental, and human-centric performance alongside traditional productivity measures. These include evaluating the triple bottom line, tracking employee well-being, and assessing adaptability and resilience (Varriale, 2023; Waheed, 2022).

Technological advances in robotics, within the framework of Industry 4.0, are transforming agriculture by streamlining processes and enhancing sustainability in agriculture. (Haloui et al., 2024; Ferreira et al., 2022; Milburn et al., 2023). However, this transition faces economic, climatic, and social challenges that require innovative solutions to ensure community acceptance and integration. (Oliveira et al., 2020; Ravankar et. Al, 2021; Lytridis et al., 2022; Droukas et al., 2023).

Romania and Portugal’s wine industry can benefit from integrating organic agriculture standards and robotics to improve production quality, sustainability, and efficiency. This will meet consumer demand for organic and environmentally responsible products. The European Green Deal and Farm2Fork strategy aim to develop ecological agriculture, focusing on environmental performance, water quality, and emissions reduction. Development of a larger database (Baisan, 2014; Dijmarescu, 2015; Gheorghe, 2018) dedicated to the wine industry, which includes specific taxonomy, production volume, markets, etc. could provide extremely useful information for wine-producing companies, customers, students or professionals in the field, institutions, etc.

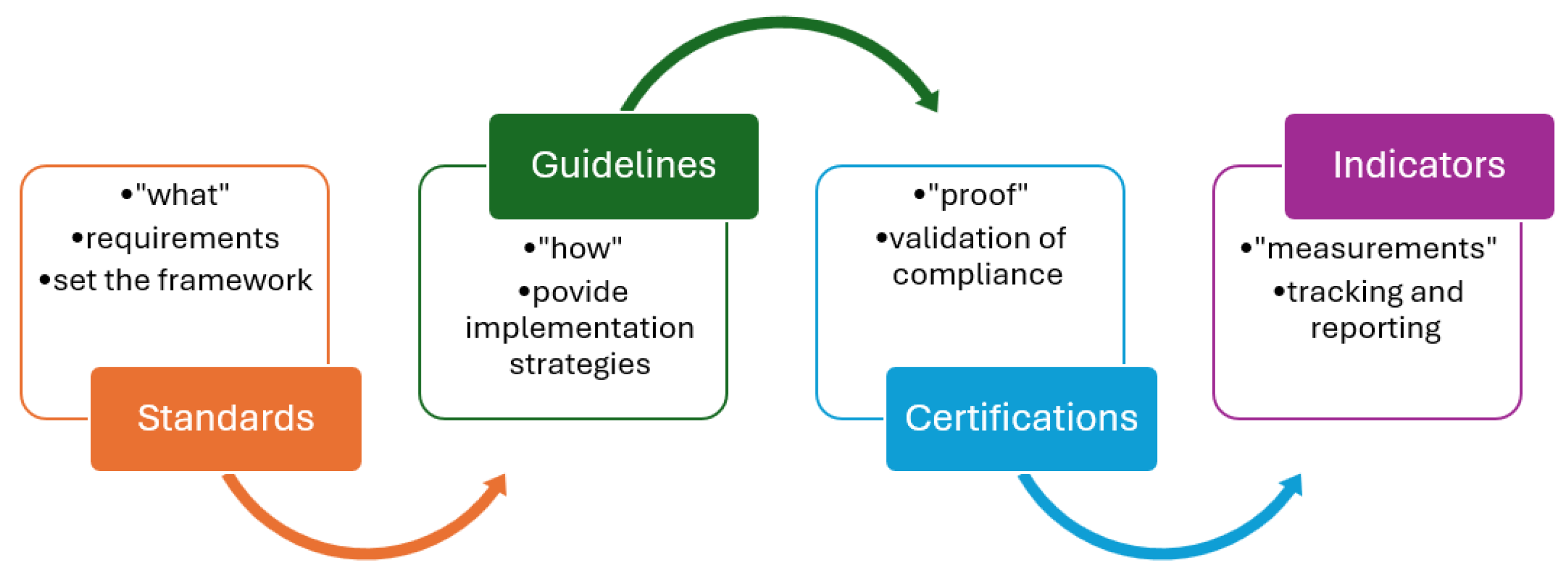

Sustainability models provide a strategic vision for sustainability practices, guiding the development of standards, guidelines, and indicators. Holistic approaches, such as the Triple Bottom Line and Doughnut Economics, encourage a holistic approach to sustainability, driving innovation and leadership. (

Figure 1).

Sustainability models guide the development of standards, guidelines, and indicators for sustainable practices. Holistic approaches like Triple Bottom Line and Doughnut Economics encourage innovation. ISO 14000 Series and ISO 26000 are standards organizations must meet for sustainability. ISO 26000:2010 and GRI Standards help organizations report their impacts. Sustainability certifications build trust and provide practical advice. Sustainability indicators measure performance, and different models may be relevant to specific sectors.

Implementing international standards in the agri-food sector enhances production, processing, quality assurance, and profitability. These standards benefit farmers, processors, government decision-makers, and operators by providing market demand information and quality assurance. Different models may be more relevant to specific sectors. A wine company can adopt a sustainability model, such as ISO 14001, ISO 26000, or GRI, to address environmental management issues. The company will also focus on Human Rights, Labor Standards, Community Engagement, Diversity and Inclusion, Sustainability Reporting, Sustainable Leadership, and Risk Management. This approach will help monitor environmental performance and ensure compliance with the standard (

Figure 2).

Sustainability standards provide the “what” (requirements), guidelines offer the “how” (implementation strategies), certifications provide the “proof” (validation of compliance), and indicators supply the “measurements” (tracking and reporting). Together, they create a robust framework for promoting and achieving sustainability (

Figure 2).

For our research, we chose Bottom Line (TBL) which refers to the idea that businesses should focus on three key areas: profit (economic), people (social), and planet (environmental). It emphasizes that companies should not only aim for financial success but also consider their social and environmental impact.

The literature highlights the connection between business sustainability, the triple bottom line, and responsible leadership. These structures emphasize the three characteristics of economic, social, and environmental sustainability. Responsible leadership influences stakeholders to create beneficial outcomes for the organization and society (Abraham, 2024). The triple bottom line emphasizes a company’s value creation for all stakeholders affected by business actions, emphasizing the company’s commitment to people (Pasamar, 2023). Purpose-driven leaders are needed to lead programs that encourage good change and make a genuine, quantifiable difference. Institutional incentives for sustainability contribute to organizations’ engagement with economic, social, and environmental issues (Nogueira, 2023). However, the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) philosophy is criticized for its practicality and validity. Achieving sustainable development goals by 2030 requires significant efforts from the public, corporate, and social sectors. Education is crucial for enabling the private sector to successfully implement SDGs, providing students with the skills and knowledge needed to identify sustainable development prospects (Srivastava, 2022; Palau, 2023; Linder, 2018).

The social component of the model will be achieved through Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education (SEE). SEE is a model that aims to improve entrepreneurial knowledge, capacities, attitudes, outcomes, and performance in developed contexts. However, providing EE alone is insufficient to achieve its objectives. To effectively provide SEE, current educational approaches must be modified. Research on sustainable entrepreneurship can provide insights into developing competencies and skills essential for sustainable entrepreneurship (Moore, 2020; Ahmad, 2022; Gyimah, 2023; Rosário, 2024). Co-creation is an approach that fosters creative solutions through stakeholder involvement. Teachers play a crucial role in promoting cooperation and supporting co-creation initiatives. The SEE program aims for participants, including young college students and senior adults, to co-create knowledge (Diepolder, 2024; Johnson, 2021; Kumari, 2019; Orazbayeva, 2021).

Considering all this context we have to offer sustainable entrepreneurial education, to meet sustainable standards, and obtain adequate values for specific indicators. In this regard, we intend to study if SEE offered by us within different hubs has a positive impact on the implementation of TBL, and Ago-ecology standards and which is the impact on Romania’s economy.

Figure 1.

Sustainability Models Categories. Note; own source.

Figure 1.

Sustainability Models Categories. Note; own source.

Figure 2.

The interconnection process of becoming sustainable. Note; own source.

Figure 2.

The interconnection process of becoming sustainable. Note; own source.

1.1. Romania, a profile of the country and its wine industry

Romania, a member of the European Union since 2007, has seen improved social and economic conditions, with GDP per capita increasing from 43% to 64% between 2007 and 2019. However, progress in the agricultural sector is less visible, with agriculture employing 22.3% of the active population and accounting for almost 4.4% of GDP.

Romania, known for its vineyards and the birthplace of Dionysus, has experienced a winemaking revival after Carol I brought in French experts. However, phylloxera destroyed vineyards between 1881 and 1910. Despite this, nurseries and research stations have emerged to save vineyards and introduce new varieties. Romania’s natural conditions and diverse actors have preserved traditions and kept wines competitive in international competitions. The wine market in Romania is around 500 million euros, with over 1,300 companies growing grapes and producing wine.

Romania’s wine industry is primarily dominated by medium-sized companies, with 61% of the market generated by these companies. The vineyards are distributed geographically in eight major wine-growing regions, with a high proportion of hybrid vine areas. Romanian wine comes from 168 grape varieties and is mainly sold domestically in supermarkets. The industry has been heavily supported by EU financial support through various funding programs, such as the Pre-Accession Fund (SAPARD), the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF), and the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD). Between 2002 and 2018, around 450 million euros were allocated for vineyard support and winery modernization. EU funding has helped replant or redevelop 42,000 hectares of vineyards and facilitated the reorientation of producers towards high-quality production. However, the sector’s restructuring problems persist despite external aid and are disproportionately borne by SMEs. The solution lies in a more involved role for public authorities and related institutions, but the limited ability to compete in high-end segments limits the sector’s competitive update.

1.2. Portugal, conditions, and development of the wine industry

Portugal’s wine industry has been underdeveloped since the eighth century, with viticulture and winemaking being underdeveloped in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1992, Harvard Business School Professor Michael E. Porter identified the wine industry as one of the strategic groups to increase competitiveness in the Portuguese economy. In 1984, an enology course was created at UTAD University to help young, educated people understand technical problems and make the transition between idea and innovation quickly and efficiently. Private research institutions like ADVID focus on promoting the Wines of Portugal brand as an international reference and increasing the competitiveness of the wine sector through investments in research and development. (ECCP, 2024)

Portugal is promoted through joint strategies and actions with the Wines of Portugal brand and the promotion of wines from the Douro Region, which contributes to efficiency in the effort to promote Portuguese wine tourism. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, Portugal remains a net exporter of wine, with exports up five percent and valued at $936 million in 2019/20. The renewed interest of Portuguese consumers in high-quality wines continues to create opportunities for wine imports. Portugal has 14 main wine regions, all producing high-quality wines. The area planted with wine grapes in Portugal was 192,743 hectares (ha), down 9% from the average of the last ten years. The Portuguese wine sector estimates that wine production in the 2020/21 marketing year will fall by three percent to 6.3 million hectoliters (MHl).

The research questions are: What is the European wine context/ current state of art? What are the main factors that affect the economic value collected from wine production? How can countries benefit from the sustainable TBL model, as well as the current and future standards, guidelines, and indicators? Do robots facilitate agroecology?

2. Methodology

Data on the area under vine, consumption, and production for Romania and Portugal were sourced from the International Vine and Wine Organization (OIV). Additionally, data on wine exports, including the value of these exports, were extracted from the World Trade Map. This export data is particularly significant in a benchmark analysis, as it reflects the external demand for Romanian and Portuguese wines and offers insights into their market performance on a global scale. The integration of these datasets serves multiple purposes: it allows for a comparative evaluation of production capabilities, domestic consumption dynamics, and export competitiveness between Romania and Portugal. Furthermore, by analyzing these variables over time, this study can identify trends and shifts in the wine industry, offering a more nuanced understanding of how both countries perform.

Data collected has been analyzed with descriptive (graphs and mean) and inferential statistics (ANOVA – variance analysis) realized with IBM SPSS version 22. We also considered it important to forecast values for all variables analyzed so as to be able to propose possible strategies to meet sustainable goals, integrated into the TBL model. Our variables are Consumption, representing wine consumption in both countries, Area, representing the area under vine, Volume, representing wine production and Export value, representing the value collected from export. In the second phase of the research, we have designed a factor analysis, using Smart PLS version 3.2.9. Our Structured Equation Model (SEM) intends to measure the weight of each factor that influences the Export value.

We also did literature research regarding the TBL model of suitability and how it is applied in Romania and Portugal and the standards, certifications, indicators, and guidelines available in the field of agroecology.

The research hypotheses resulting from context analysis are:

H1. There is a significant difference between Romania and Portugal regarding wine consumption, cultivated vineyard area, grape production, the volume of wine produced, and the value collected from wine export

H2. The main factors that influence the value collected from wine export are consumption, volume of wine produced, and vineyard area

3. Results

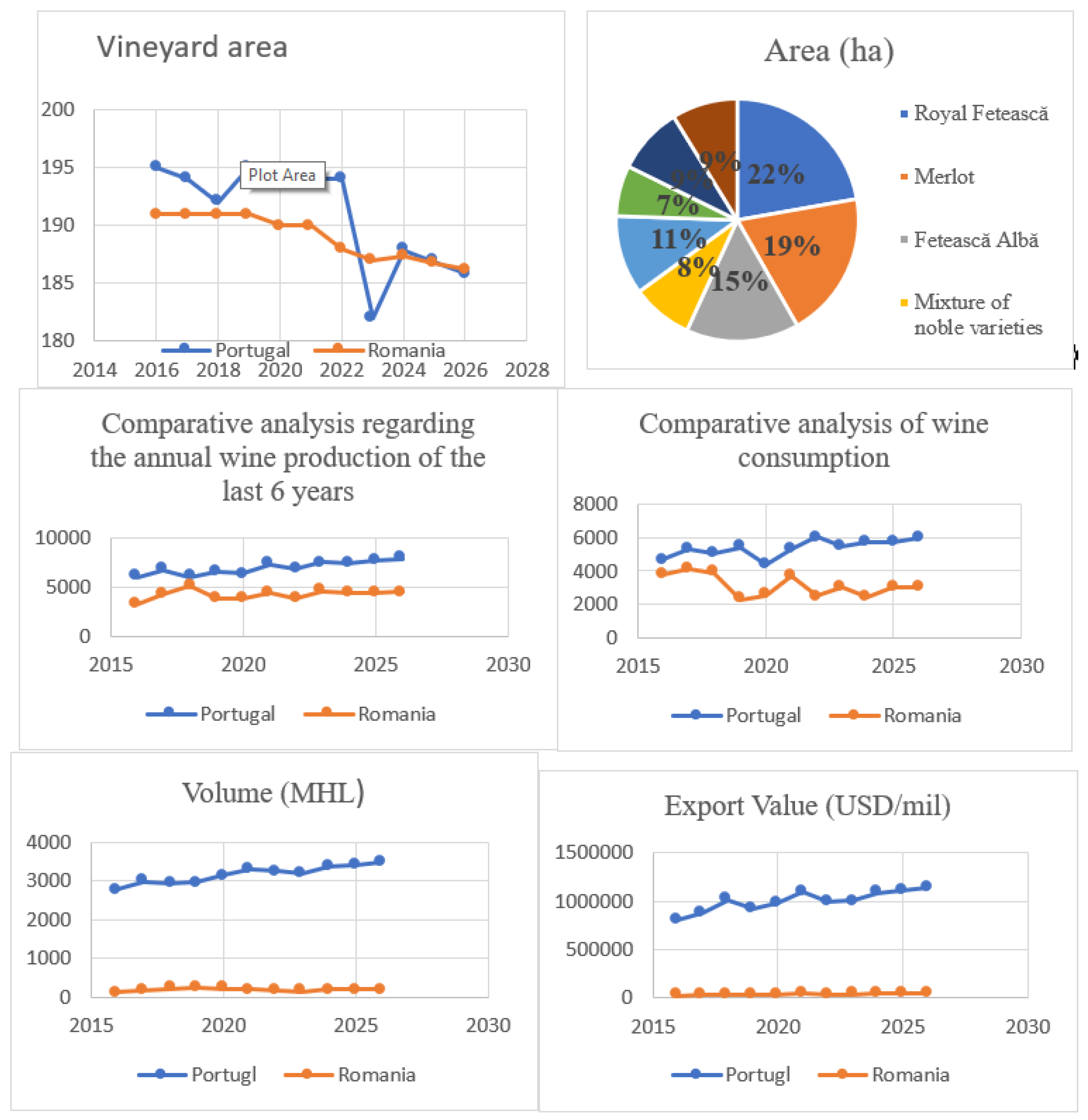

To make a statical comparison between Romania and Portugal we apply the One-way ANOVA analysis, the Welch’s test assuming unequal variances. In our analysis, we included 5 variables: Consumption (wine consumption), Area (cultivated vineyard area), Production (Grape production), Volume (wine production), and Export value (the value collected from export). The F high values prove that there is statistically significant difference between 2 countries regarding the Consumption (µP=5366, µRo= 3122), Production (µP=6951, µRo= 4227), Volume (µP=3168, µRo= 184), Export value (µP=1000000, µRo= 37211) with a very high significant level (p-value < 0.001). Hence, regarding the cultivated vineyard area (µP=191, µRo= 189), the difference is not statistically significant as the F value is even lower the 1.96 at a very low significance level (p-value = 0.197, higher than the 0.05 threshold), as might be observed in

Table 1 and Annex1 and

Figure 3. These results are confirmed by the graphical analysis presented in

Figure 5.

The study compares vineyard areas in Portugal and Romania, revealing Romania’s smaller area for vine cultivation. In 2020, Portugal’s vineyard area decreased by -0.4% compared to 2019, while Romania’s decreased by -0.2%. Portugal’s cultivated area represented 2.7% of the global total, while Romania’s was 2.6% (

Figure 3a,b). From

Figure 3b above, we identify that the largest area is cultivated with the Fetească Regală variety, respectively 13.634 ha with a share of 15.52%, followed by Merlot with 12.010 ha and 13.68% share, Fetească Albă with 9.241 ha and 10.52% share, Italian Riesling with 6.488 ha and 7.39% share and Sauvignon with 5.478 ha and 6.24% share.

Portugal produced a slight reduction in wine production in 2020 compared to 2019, but a larger quantity in 2020 (

Figure 3c). Romania’s wine consumption remained steady in 2020, while in 2021, Portugal maintained its consumption, while Romania increased. The study highlights the differences in wine production and consumption between the two countries (

Figure 3d).

Romania has exported wine in the last six years, with the smallest amount being 12,890 tons worth 22,716 million dollars in 2016. The quantity increased until 2019 when it exported 21,820 tons worth 34,531 million dollars. However, the quantity began to decrease to 17,282 tons in 2021, worth 40,405 million dollars. Portugal exported 328,963 tons worth 1,094,800 million dollars in 2021 (

Figure 3e,f).

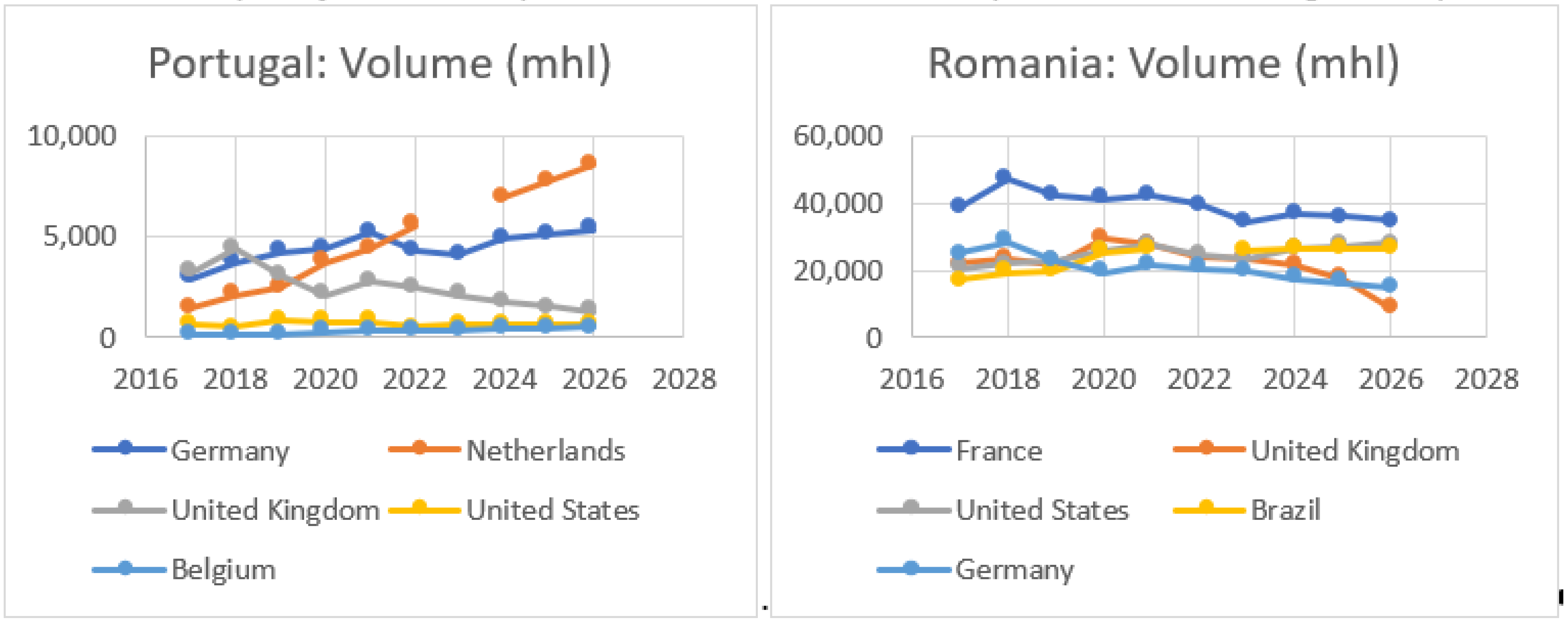

Germany is the first partner to which Romania exports the largest amount of wine, with Germany in first position, exporting wine worth 9.482 million dollars in 2021. The Netherlands followed with 4,361 tons in 2021, followed by the United Kingdom with 4,439 tons in 2018. The United States imported from Romania in 2019 with 810 tons, and Belgium imported 348 tons in 2021 (

Figure 4).

Portugal’s main partners to which it exported the largest quantity of wine are France, the United Kingdom, the United States, Brazil, and Germany. France exported the largest quantity to France in 2018, followed by the United Kingdom, the United States, Brazil, and Germany. Portugal’s main partners to which it exported the largest amount of wine are France, the United States, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Germany (Annex 2).

Romania’s wine production in 2021 increased to 173.7 thousand hectares, but production decreased to 3.959.7 thousand hl compared to 2017 and 2018. White wine accounted for 1,385.89 thousand hl, followed by red wine at 751.10 thousand hl and rosé wine at 245.04 thousand hl. The largest area cultivated was Fetească Regală, with 13.634 ha of 15.52% share. Romania’s wine sector development differs from countries like Italy and Spain, but Portugal’s example is easier to follow. A realistic assessment of the sector and implementing a strategy for the sector can help develop competitiveness (Annex 3).

We can say that Romania has distanced itself quite a lot from countries like Italy and Spain in terms of the development of the wine sector, given that the two countries recognized the importance of the sector and took steps in this regard many years ago. But Portugal’s example seems to be easier to follow. The key to success seems to start from a realistic assessment of the sector and its recognition as an essential part of the development of the agricultural sector and the country’s economy. Building a strategy for the wine sector, which includes key points of action and is meant to be put into practice by industry players capable of understanding their importance, seems to be a successful way of developing competitiveness and implicitly of the sector.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of Romania vs Portugal regarding Consumption, Area, Production, Volume, and Export value. Note; own source.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of Romania vs Portugal regarding Consumption, Area, Production, Volume, and Export value. Note; own source.

Table 1.

Variance Analysis Portugal vs Romania on 5 wine indicators.

Table 1.

Variance Analysis Portugal vs Romania on 5 wine indicators.

| One-way ANOVA (Welch’s) |

F |

df1 |

df2 |

p |

| Consumption |

78.41 |

1 |

18.8 |

< .001 |

| Area |

1.83 |

1 |

13.8 |

0.197 |

| Production |

119.96 |

1 |

18.8 |

< .001 |

| Volume |

1911.25 |

1 |

10.3 |

< .001 |

| Export value |

937.2 |

1 |

10.1 |

< .001 |

3.1. TBL – Romanian wine industry

For the Romanian wine producers, the implementation of the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) strategy — which integrates economic, social, and environmental performance — is essential for the long-term sustainability of the wine industry. This approach enables winemakers to balance financial objectives with stringent environmental protection and social responsibility requirements, all within the context of progressive integration into European and international markets.

a. The economic pillar of the TBL strategy focuses on increasing competitiveness and improving operational efficiency. Romanian wine producers have accessed European funds to modernize winemaking infrastructure and improve the quality of their products. These investments have enabled them to produce higher-quality wines, thereby strengthening their presence in international markets. Special attention is given to the promotion of indigenous grape varieties, such as Fetească Neagră and Fetească Albă, to differentiate Romanian wines globally and meet the growing demand for authentic, premium products. These strategies contribute to enhancing the value-added of Romanian wines and expanding their presence in foreign markets (Mihalache, 2020).

b. Environmental pillar: Romanian wine producers face significant environmental sustainability challenges, particularly in relation to climate change and natural resource management. Many wineries have thus adopted sustainable practices, including the reduction of pesticide and chemical fertilizer use, as well as water conservation measures. Organic agriculture is gaining ground, with an increasing number of producers shifting their operations toward organic viticulture, maintaining biodiversity, and preserving soil health. Additionally, some producers are beginning to adopt renewable energy sources and innovative waste management practices, such as reusing by-products from the winemaking process (Hospido, Rivela, Gazulla, 2022). These efforts are essential for reducing the carbon footprint and strengthening Romania’s role in sustainable wine production. The organic framework for producing organic wines in Romania is regulated by both European Union legislation and national standards, ensuring that wine production adheres to strict sustainability practices. Organic wine production in Romania is aligned with EU organic farming legislation, particularly Regulation (EU) No. 2018/848, which sets out the criteria for organic agricultural practices. Key components of this framework include:

- Vineyards must be certified by accredited bodies such as ECOCERT or Austria Bio Garantie, which are responsible for ensuring compliance with EU organic standards. Vineyards undergo a three-year conversion period before achieving full organic certification. During this time, synthetic chemicals such as pesticides, herbicides, and chemical fertilizers are prohibited and replaced with natural alternatives (MI, 2020).

- Soil health is a central concern in organic viticulture, with a focus on enhancing biodiversity and maintaining soil fertility. Organic vineyards in Romania use natural composts, organic fertilizers, and cover crops to manage soil quality. The use of synthetic chemical inputs is strictly prohibited, and organic producers employ natural pest control methods, such as introducing natural predators and using plant-based treatments to prevent vine diseases.

- The use of additives in organic winemaking is strictly regulated. Organic wine production minimizes the use of sulfur dioxide (SO2) and avoids additives such as enzymes and flavor enhancers. Fermentation is often conducted with natural yeasts, which enhances the authentic characteristics of the wine. Filtration and clarification must also be done with natural materials. (Giacosa, S., Segade, SG., Cagnasso, E., Caudana, A., Rolle, L., Gerbi, V., 2019).

- Organic wine production in Romania places strong emphasis on water conservation, reducing energy consumption, and minimizing the carbon footprint of wine production. Some producers have adopted biodynamic practices, which go beyond organic standards, following the natural cycles of the moon and planetary movements to optimize vine growth and wine quality. (Tancelov, Dobre Gudei, 2024).

- Organic wine production in Romania focuses not only on compliance but also on meeting the growing consumer demand for sustainable and eco-friendly products. Organic certifications, as well as biodynamic labels, serve as important marketing tools, giving wines a competitive edge on the international market.

This framework, driven by both European regulations and growing consumer interest in sustainability, positions Romanian organic wines competitively on the international market, while ensuring that environmental and health standards are upheld. As of the latest available data, Romania has a significant number of wineries certified by ECOCERT, though the exact number fluctuates due to the ongoing certification process. ECOCERT certification, which guarantees adherence to organic farming principles, is widely recognized in the Romanian wine industry, particularly among premium producers. Key players such as Domeniul Bogdan, Crama Delta Dunării - La Săpata, and Domeniile Franco-Române are among the notable wineries with ECOCERT certification, known for their commitment to organic and biodynamic practices. (Jităreanu, Mihăilă, Robu , Lipșa, and Costuleanu CL, 2022).

c. The social pillar of the TBL strategy focuses on responsibility toward local communities and the preservation of viticultural traditions. The wine industry plays a vital role in rural areas of Romania, providing jobs and contributing to local economic development. Many producers invest in improving working conditions and training their employees, thereby ensuring social sustainability and providing fair and safe working conditions. At the same time, wine tourism is an important component of the economic strategy of Romanian wineries, attracting international visitors and promoting wine regions such as Dealu Mare and Murfatlar as recognized tourist destinations. This tourism contributes to both economic development and the preservation of cultural traditions.

In a nutshell, the adoption of the Triple Bottom Line strategy by Romanian wine producers represents an integrated approach that supports not only economic development but also environmental protection and the well-being of local communities. By implementing sustainable practices, Romanian producers are enhancing their international competitiveness and contributing to the preservation of the country’s viticultural traditions, while simultaneously meeting the increasingly strict global sustainability requirements (European Union, 2020). Furthermore, the development of wine tourism has become an important part of their strategy, attracting visitors from around the world and promoting traditional wine regions, such as Dealu Mare and Murfatlar, as renowned tourist destinations (European Union, 2020).

3.2. TBL – Portugal wine industry

The adoption of the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) strategy in the Portuguese wine industry is crucial for ensuring the long-term sustainability of this key economic sector. TBL emphasizes the need for wine producers to balance economic growth, environmental responsibility, and social impact, positioning Portugal as a competitive and sustainable player in the global wine market.

a. The economic sustainability of the Portuguese wine industry is driven by its contribution to the country’s GDP and its robust export market. Wine exports, particularly from regions like the Douro Valley, Alentejo, and Vinho Verde, have been steadily growing, reaching €925 million in 2021 (IVV, 2021). To maintain this momentum, Portuguese wineries are focusing on producing high-quality wines, diversifying into organic and premium wine markets, and increasing value-added through branding and international market access. Additionally, the Portuguese wine sector benefits from EU funds, which support the modernization of winemaking processes and infrastructure, ensuring that wineries can continue to meet global demand while maintaining efficiency (Cunha, Serpa, Marques et.al., 2023).

b. Sustainability in the Portuguese wine industry is closely tied to environmental practices that preserve the natural resources vital to viticulture. Key environmental strategies include:

- Many wineries, such as those in Alentejo and Douro, have embraced organic and biodynamic farming practices. These approaches reduce the use of synthetic chemicals, improve soil health, and promote biodiversity (CVRA, 2021).

- Efficient water usage is critical in regions affected by climate change, particularly in the hotter areas of Alentejo. Vineyards are employing water conservation techniques like drip irrigation and rainwater harvesting to reduce their environmental impact (Trigo, Fragoso, and Marta-Costa, 2022).

- Several wineries have integrated solar panels and other renewable energy sources to lower their carbon footprint, while also adopting sustainable packaging to further reduce environmental impact (Martinis, 2019).

- In regions like Alentejo, biodynamic viticulture goes beyond organic farming by aligning vineyard activities with lunar cycles and natural ecosystems to enhance both the environmental and qualitative aspects of wine production (Swiatkiewicz, 2021).

Approximately 2.2% of Portuguese vineyards are certified organic, with the Douro and Alentejo regions being major contributors to organic wine production. The northern region of Trás-os-Montes leads with 36% of total organic wine production in the country, followed by Alentejo with 28%. Despite this, in terms of planted acreage, Alentejo has a larger area dedicated to organic viticulture, although its yields are typically lower due to the challenging soil conditions.

Portugal has a growing number of organic wineries, with organic wine becoming an increasingly important sector within the Portuguese wine industry, supported by both regional practices and EU regulations that ensure organic certification. However, organic wine still represents a relatively small but expanding portion of the market, driven by both domestic and international demand for sustainably produced wines (Da Silva, da Silva, 2022)

3. The social impact of the Portuguese wine industry is rooted in its role as a key contributor to rural development and employment. The sector provides jobs for thousands of people, particularly in rural regions where other economic opportunities may be limited. Key social sustainability initiatives include:

- fair labor practices: many wineries are committed to ensuring fair wages, safe working conditions, and long-term employment for vineyard workers, particularly during the grape harvest season (Fragoso, Figueira, 2020)

- cultural preservation: the Portuguese wine industry plays a critical role in preserving traditional wine-making practices and protecting indigenous grape varieties, such as Touriga Nacional and Arinto, which contribute to the country’s unique wine identity. Wine tourism has become a significant factor in sustaining local communities, attracting visitors to experience Portuguese wine culture in regions like Douro and Alentejo (Dinis et al., 2019).

In addition to boosting local economies, wine tourism in Portugal preserves the cultural and historical significance of wine regions by promoting their heritage. It also generates additional revenue streams for winemakers and supports the local hospitality industry (Trigo, Ana, and Paula Silva. 2022)

In a nutshell, the adoption of the Triple Bottom Line strategy in the Portuguese wine industry enhances its resilience and global competitiveness. By focusing on the economic, environmental, and social pillars, Portuguese wineries are positioning themselves not only as major players in the global wine market but also as leaders in sustainable and responsible wine production. This integrated approach ensures that the industry contributes to the country’s economic growth, protects its environmental resources, and supports the well-being of local communities.

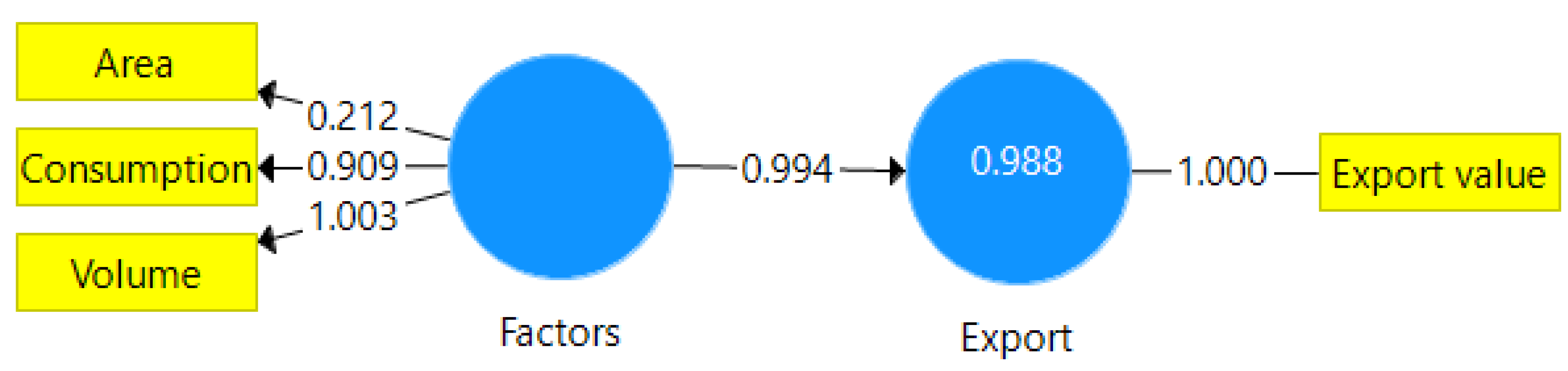

To verify the importance of each factor that influences the Export value we designed an SEM in Smart PLS. SmartPLS provides a range of tests to guarantee the correctness and dependability of data.

Table 2 presents the validation protocols that were employed in this investigation by Vinzi et al.‘s guidelines. Excellent composite reliability, Cronbach Alpha (CA), rho_A (>0.7), and Average Variance Extracted (>0.5) values were shown by all variables, indicating that the model was consistent. This model proves that the factors that positively influence the Export value are Area, Consumption, and Volume (

Figure 4). These 3 factors form a consistent variable, Factors, with CA =0.709 > 0.7. Between variables Factor and Export, there is a very strong positive correlation as Spearman coefficient rho_A (0.951) shows, meaning that an increased value of Factors will be associated with an increased value for Export. The model presents a very high composite reliability (CR=0.801 > 0.7) and the variance meets the criterion of being higher than 0.5 (AVE= 0.625). The huge value of R square and F Square prove that almost 100 % of the variance of the independent variable (Area, Consumption, and Volume) explains the variance of the dependent variable, Export (

Table 2,

Figure 5). The loading factors show that the most important factor that influences the Export value is Volume (LF=1.003) and Consumption (LF=0.909). We can affirm that a higher level of consumption will ask for more exports and a high volume of wine obtained would be associated with higher export values. These 2 factors present an acceptable grade of multicollinearity as their VIF is 5. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) has the threshold 5. The cultivated area has a low LF=0.212, meaning that with a small surface cultivated area, as in Portugal, the grape production and wine volume can reach very high values if adequate methods.

With an SRMR of 0.009, which indicates good model fit, the estimated model outfits the saturated model. The substantially smaller Chi-Square for the estimated model (our model) is equal to the saturated model. The estimated value should be greater or equal to the saturated value. Additionally, an NFI of 0.971, very close to the maxim value 1, indicates an excellent overall model fit (

Table 3).

Figure 4.

EU context – Analysis of the 5 main partners to which Romania exports wine according to USD/mil Value. Source: TM202.

Figure 4.

EU context – Analysis of the 5 main partners to which Romania exports wine according to USD/mil Value. Source: TM202.

Figure 5.

Structured Equation Model: Factors that influence Wine Export. Note; Reprinted from SmartPLS 3.2.9, free version.

Figure 5.

Structured Equation Model: Factors that influence Wine Export. Note; Reprinted from SmartPLS 3.2.9, free version.

Table 2.

SEM validation steps.

Table 2.

SEM validation steps.

| |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

rho_A |

Composite Reliability |

AVE |

R Square |

F Square |

| Threshold |

CA >0.7 |

r> 0.5 |

CR > 0.7 |

AVE> 0.5 |

Max 1 |

F>1.96 |

| Factors |

0.709 |

0.951 |

0.801 |

0.625 |

|

85.69 |

| Export |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1 |

0.988 |

|

Table 3.

Fit model summary.

Table 3.

Fit model summary.

| Indicators |

Saturated Model |

Estimated Model |

| SRMR |

0.009 |

0.009 |

| d_ULS |

0.001 |

0.001 |

| d_G |

0.040 |

0.040 |

| Chi-Square |

4.421 |

4.421 |

| NFI |

0.971 |

0.971 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Economic Impact

Romania, a member of the European Union since 2007, has seen improvements in social and economic conditions due to its EU membership. GDP per capita increased from 43% to 64% between 2007 and 2019, with the economy shifting to capital-based industries. However, progress in the agricultural sector is less visible, with agriculture employing 22.3% of the active population and accounting for almost 4.4% of GDP. The wine sector is expected to suffer due to losses in agricultural occupation efficiency.

Romania’s wine industry is primarily dominated by medium-sized companies, with 61% of the market generated by these companies. The region is known for its vineyards, which were short-lived due to phylloxera. Despite this, nurseries and research stations have emerged to save vineyards and introduce new varieties like Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, Chardonnay, and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Portugal’s wine industry has been underdeveloped since the eighth century, but the natural conditions for producing high-quality wines have long been recognized in traditional wine-growing regions like the Douro Valley. Private research institutions have been created to promote the Wines of Portugal brand and increase competitiveness through investments in research and development.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, Portugal remains a net exporter of wine, with exports up 5% and valued at $936 million in 2019/20. The renewed interest of Portuguese consumers in high-quality wines continues to create opportunities for wine imports. Portugal has 14 main wine regions, all producing high-quality wines.

The study compares vineyard areas in Portugal and Romania, revealing Romania’s smaller area for vine cultivation. In 2020, Portugal’s vineyard area decreased by -0.4% compared to 2019, while Romania’s decreased by -0.2%. Portugal produced a slight reduction in wine production in 2020 but a larger quantity in 2020. Romania’s wine consumption remained steady in 2020, while Portugal maintained its consumption in 2021. Romania has exported wine in the last six years, with Germany being the first partner. Portugal’s main partners are France, the United Kingdom, the United States, Brazil, and Germany. Romania’s wine production in 2021 increased to 173.7 thousand hectares, but production decreased to 3.959.7 thousand hl compared to 2017 and 2018.

The significant differences in the value of exports and in wine production between Romania and Portugal are influenced by factors such as the perceived quality of wine, international marketing strategies, processing infrastructure, and access to foreign markets, Portugal has a competitive advantage in these areas, which adds a higher added value to exported wines.

The substantial differences in the value of exports and in wine production between Romania and Portugal can be explained by factors such as the superior perception of the quality of Portuguese wine, the use of more effective international marketing strategies, a better-developed processing infrastructure, and easier access to markets external, thus giving Portugal a competitive advantage and a higher added value of exported wines:

1. Lack of strong associations to negotiate serious contracts and enter the external value chain (supermarkets, specialized stores);

2. The lack of wine (country brand) such as Bordeaux, Chianti, Portuguese Porto, and more recently Mateus, which attracts buyers to other products of the country;

3. Non-synchronization of producers in promoting themselves properly. I do different campaigns, the messages are often different, you don’t go united, on a country brand;

4. Lack of export strategy at the level of authorities.

Thus, the answer to our research question is: Wine has been a part of the European way of life for centuries. The European Union is the world’s largest producer, consumer, and exporter of wine. According to Eurostat, in 2020 the total area under vines in the EU was 3.2 million hectares, accounting for 2% of the utilized agricultural area in the EU and 45 % of all vine-growing areas in the world. Most EU production takes place in Spain, France, and Italy, which together account for three-quarters of the EU area planted with vines. The EU had 2.2 million vineyard holdings in 2020, varying in size from an average of 0.2 hectares in Romania to 10.5 hectares in France. The EU also accounted for 48% of global wine consumption in 2021, with the largest overall consumption recorded in France, Italy, and Germany. Globally, only the United States consumed more wine than any of these three countries. Nevertheless, the industry is currently experiencing some distress, facing headwinds from rising costs and changes in the drinking habits of consumers at home and abroad. The leading countries in Europe for wine are also some of the leaders in global production so their status affects the market as a whole. In 2023, the size of the European wine market reached nearly 75 billion U.S. dollars and is expected to remain largely flat in the coming years. (Statista Research Department, 2024). To face the challenges ahead there is also a growing emphasis on sustainable viticulture in the European Union, with many producers adopting organic and biodynamic farming practices to meet consumer demand for environmentally friendly products. Also, innovations in viticulture and vinification, such as precision agriculture and advanced fermentation techniques, are enhancing quality and efficiency in production.

For both Romania and Portugal, the implementation of the TBL strategy in the wine sector could contribute to increasing market competitiveness by offering high-quality products and services that meet customers’ requirements. Adopting sustainable practices and reducing environmental impact will have the medium and long-term effect of protecting natural resources and improving quality of life. TBL also supports the development of a culture of social responsibility and can contribute to increased international cooperation by promoting the exchange of experience and knowledge between countries and organizations. The implementation of the model will lead to increased confidence in the two countries as producers and exporters by demonstrating commitment to sustainable development and social responsibility.

In terms of current and future standards, guidelines, and indicators, countries can draw on a number of resources, including: the European Code of Environmental and Social Responsibility (CSR) [Sternberg, E., 2009], a common basis for reporting on corporate and country environmental and social responsibility; the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) [Dissanayake, D., 2021], an international standard for environmental and social responsibility reporting, which provides a structure and set of indicators for reporting performance. In Romania, there is a centralized national set of SDGs indicators for public authorities involved in the monitoring and reporting process of the National Strategy for Sustainable Development of Romania 2030, for which the National Institute of Statistics has developed a guide describing what needs to be done, who the main actors are, their roles in monitoring the SDGs and opportunities for cooperation. This guide includes concrete actions, priorities, and recommendations. It also helps stakeholders understand their role in achieving the SDGs (INS, 2018)

In conclusion, these standards and certifications provide a reference framework for organizations that want to develop business strategies that take into account financial, environmental, and social aspects. A vision for human-centered, flexible, and sustainable production systems is provided by directional elements in Industry 5.0. In the meantime, applicative components offer tangible, quantifiable means of accomplishing these objectives by utilizing data-driven performance indicators and robotics improvements. By combining these components, a manufacturing ecosystem is created that is not only adaptable and efficient but also socially and environmentally conscious. In this regard, we contribute to the design Romanian Standard for Organic Agriculture and assumptions in robotics innovation in the wine industry.

4.2. Environmental Issues – personal contribution

The standard designed by us outlines criteria and recommendations for sustainable ecological products, including documentation, good practices, transparency, and sustainability.

The Romanian Standard for Organic Agriculture - SR 13595:2022 Ecologic farming. Requirements and recommendations for sustainable ecological products - specifies requirements and recommendations for sustainable organic products, considering the importance of increasing efficiency and transparency in agriculture. The standard is intended for certified organic organizations that want to apply the principles of agroecology and obtain certification according to this standard. It includes a normative annex with forms and indicators for recording evidence of compliance with the requirements, which simplifies the implementation work and establishes a minimum level of evidence necessary to meet the requirements. The standard includes a number of requirements and recommendations.

Certified organic organizations must:

- adhere to the principles of agroecology, including basic principles, objectives, and recommendations;

- document and implement good practices in agriculture, including soil, water, and biodiversity conservation practices;

- ensure transparency and traceability in the production, processing, and marketing of products;

- obtain organic certification before applying the standard.

Our standard is a step forward in national standardization for organic farming because it supports the European Union in achieving the objectives contained in the European Green Deal. Given that the European Green Deal has as its main objective the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and pollution, as well as the promotion of a green and sustainable economy, the SR 13595:2022 Standard contributes directly to these objectives by specifying requirements and recommendations for sustainable organic products. This standard is also a concrete achievement of the standardization community and is in line with the London Declaration, which has undertaken to develop standards to support the fight against climate change. SR 13595:2022 is a concrete example of this commitment, providing a solid basis for the production and marketing of sustainable organic products.

The SR 13595:2022 standard offers the following benefits:

- simplifies the implementation work and establishes a minimum level of evidence necessary to meet the requirements;

- ensures transparency and traceability in the production, processing, and marketing of products;

- provides the guarantee that the products are produced in accordance with the principles of agroecology and the requirements of the standard.

4.3. Techno- social implications

Agriculture advancements are linked to industrial sectors, with Industry 4.0 focusing on intelligence, cloud communication, and autonomous decision-making. This fourth smart industry revolution enhances efficiency and competitiveness (Haloui et al., 2024). All these developments are happening with the help of several key technologies such as the Internet of Things, AI, Robotics, and Big Data Analytics. The newer advances in terms of human-robot cooperation, cognitive systems, and product mass customization are facing us to the next level of the industrial revolution - Industry 5.0.

Industry 4.0 technologies have accelerated the Agriculture 4.0 revolution, enhancing farming efficiency and sustainability through real-time data, intelligent machines, and digitalization. Combining intelligent machines and systems in Agriculture 5.0 the focus is on higher yields, sustainability, and environmental conservation through AI, robotics, and machine learning.

Robotics have become widely embraced in agricultural production as a necessity for reducing the impact of repetitive tasks on humans. Robots in agricultural applications are broadly classified based on locomotion and the way it is controlled. Based on locomotion, robots are classified as stationary and mobile. Mobile robots can move from one place to another following a predefined pathway. Based on the environment they work, can be land robots, flying, e.g., drones, or aquatic robots. Land-based robots can perform movements using different types of wheels or tracks for hard and uneven surfaces. Legged robot locomotion is obtained with a number of articulated and orientable legs, 4 legs simulating animal locomotion and 6 legs simulating insect locomotion. The legged design, even if more challenging and difficult in terms of design and controlling (Milburn et al., 2023), could facilitate access to more complex agricultural lands (Ferreira et al., 2022).

Robots and advanced tractors are revolutionizing autonomous farming and agricultural output, being used more and more in notable applications (Oliveira et al., 2020). Research and commercial projects have been developed and implemented robotic solutions for different specific agricultural applications such as harvesting, weeding, spraying cultivation areas, pruning and monitoring for yield estimation, and identifying possible diseases on the plantation.

While conducting a task, the robot should generate efficient operating movements and paths and autonomously navigate around barriers in the field (Ravankar et. Al, 2021). Also, it is necessary to prioritize to avoid damaging the crop and to consider the safety of farms and workers. Autonomous navigation requires perception of the environment and navigation algorithms. Perception of robots in space involves a variety of sensors, including computer vision, Light-detecting and ranging (LiDAR) sensors - commonly used for the navigation of robotic systems because of their accuracy and the range of measurements, satellite positioning systems (GPS) sensors, inertial measurement units (IMU) (Lytridis et al., 2022).

Vineyards, a particularly high-value field of agriculture, are using automated agricultural technologies. Even if the vineyard environment presents lots of challenges (e.g., types of orchards, soil, and general terrain morphology, different research projects have been funded by the EU such as VINEROBOT, VINBOT, GRAPE - Ground Robot for vineyard monitoring and ProtEction, VineScout, BACCHUS (Droukas et al., 2023). Developed robotic solutions through research and commercial projects are presented in Annex 4.

Advancements in agriculture face economic, climate, technological, and social challenges due to higher robotic costs, technical complexity, and the need for innovative decision-making systems.

Romania’s organic agriculture standards emphasize sustainable farming methods, including soil health, biodiversity, and the prohibition of synthetic chemicals. Compliance with these standards in vineyards means chemical-free farming, sustainable soil management, and obtaining organic certification, which boosts market appeal, especially in Europe. Adopting organic practices aligned with Romania’s standards strengthens the industry’s position in international markets, attracting eco-conscious consumers and potentially allowing higher pricing for premium, certified organic wines.

Robotic development in the wine industry can improve vineyard management, soil monitoring, pest detection, and harvest efficiency, promoting sustainability, reducing environmental impact, and data-driven quality control.

Product quality and certification compliance are key performance indicators and market impacts. Robotics allow wine producers to maintain meticulous standards required for organic certification, ensuring high-quality output that meets regulatory and consumer expectations. Cost-effectiveness and profitability can offset initial investments in robotics, as long-term benefits in labor savings, improved grape yield, and reduced manual intervention offset these costs.

Market differentiation is possible as Romania builds a reputation for high-quality, organic wines produced sustainably, giving wineries that integrate robotics a competitive edge in the international market. This could attract environmentally conscious consumers and position Romania as a leader in tech-enabled organic viticulture.