Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

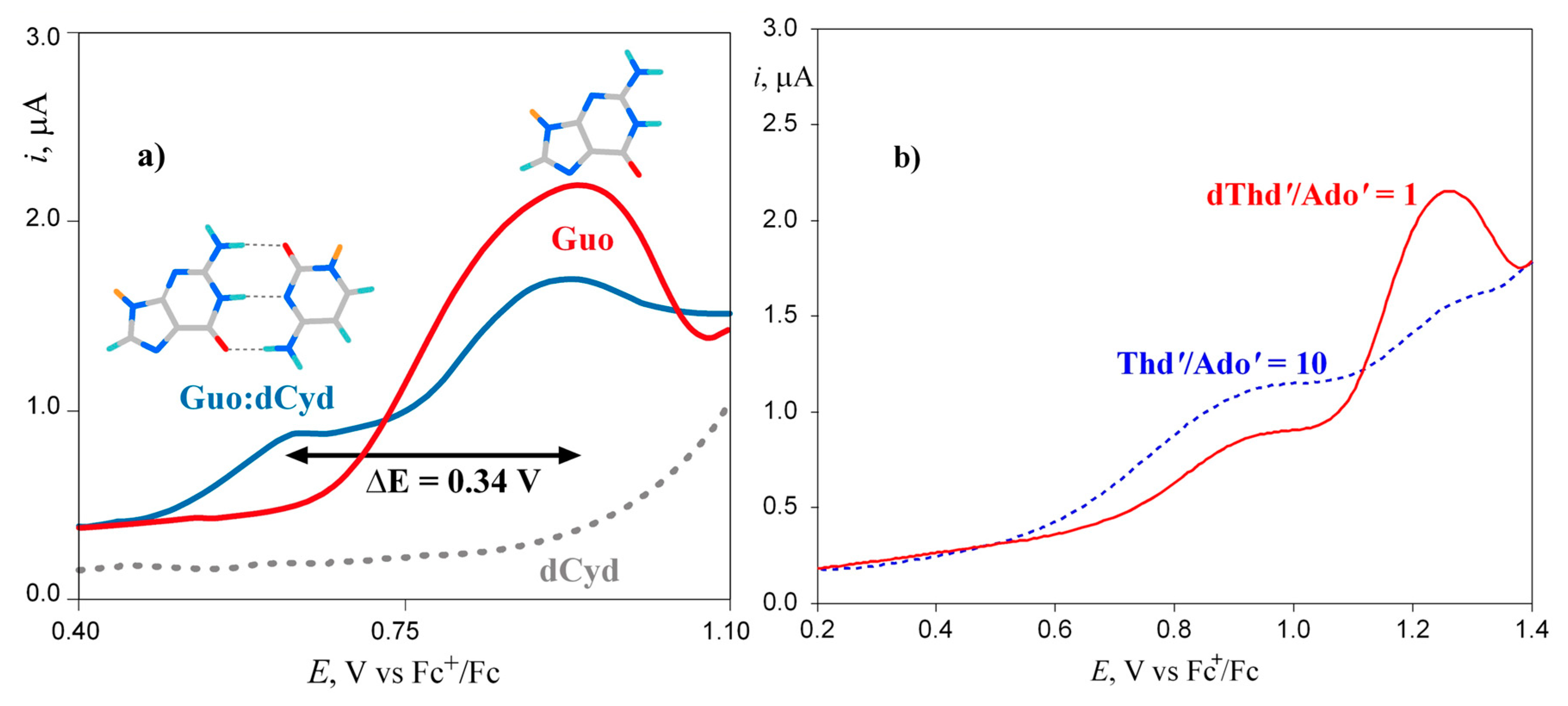

1. Oxidation Free Energy of Nucleobases

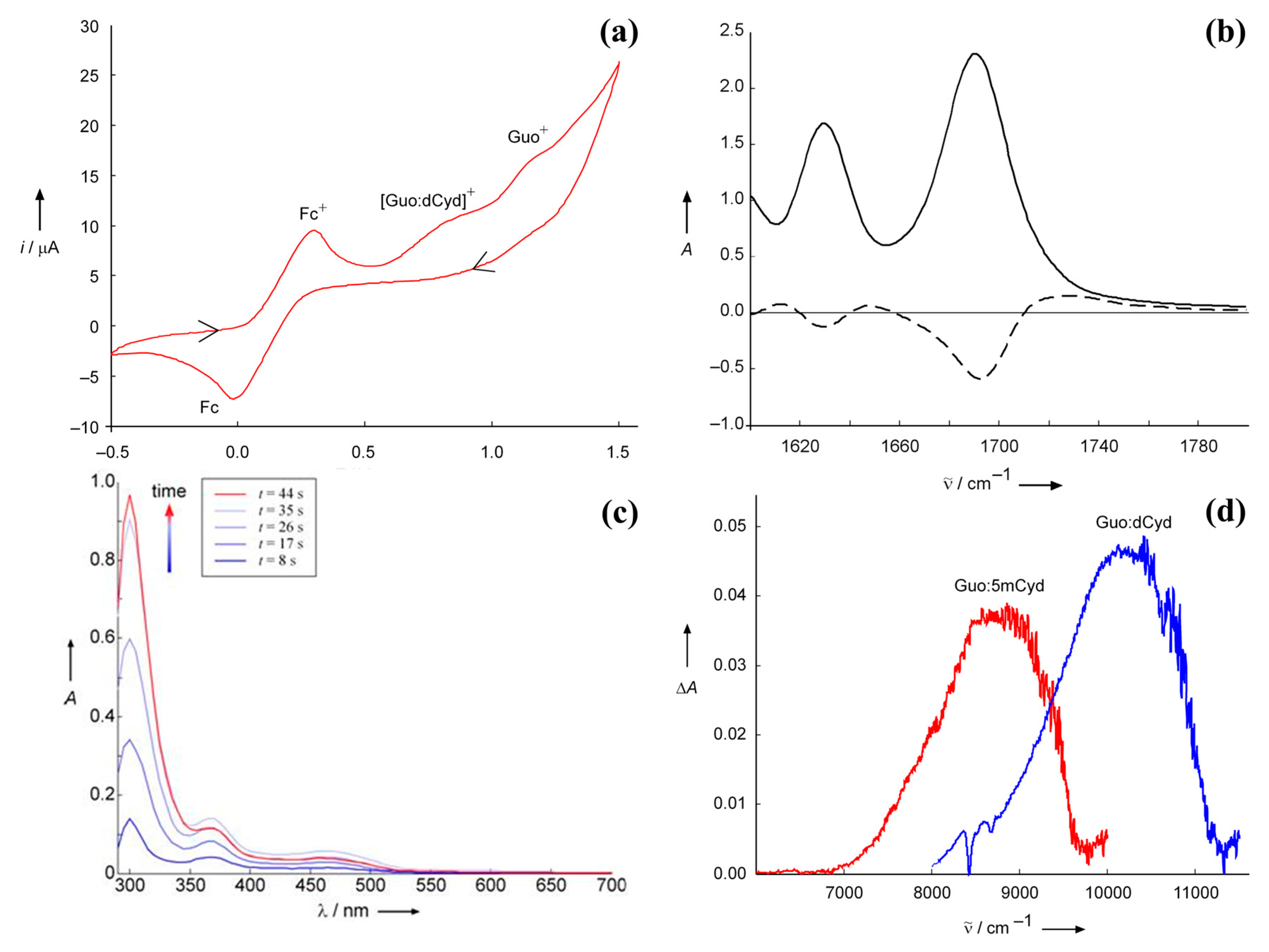

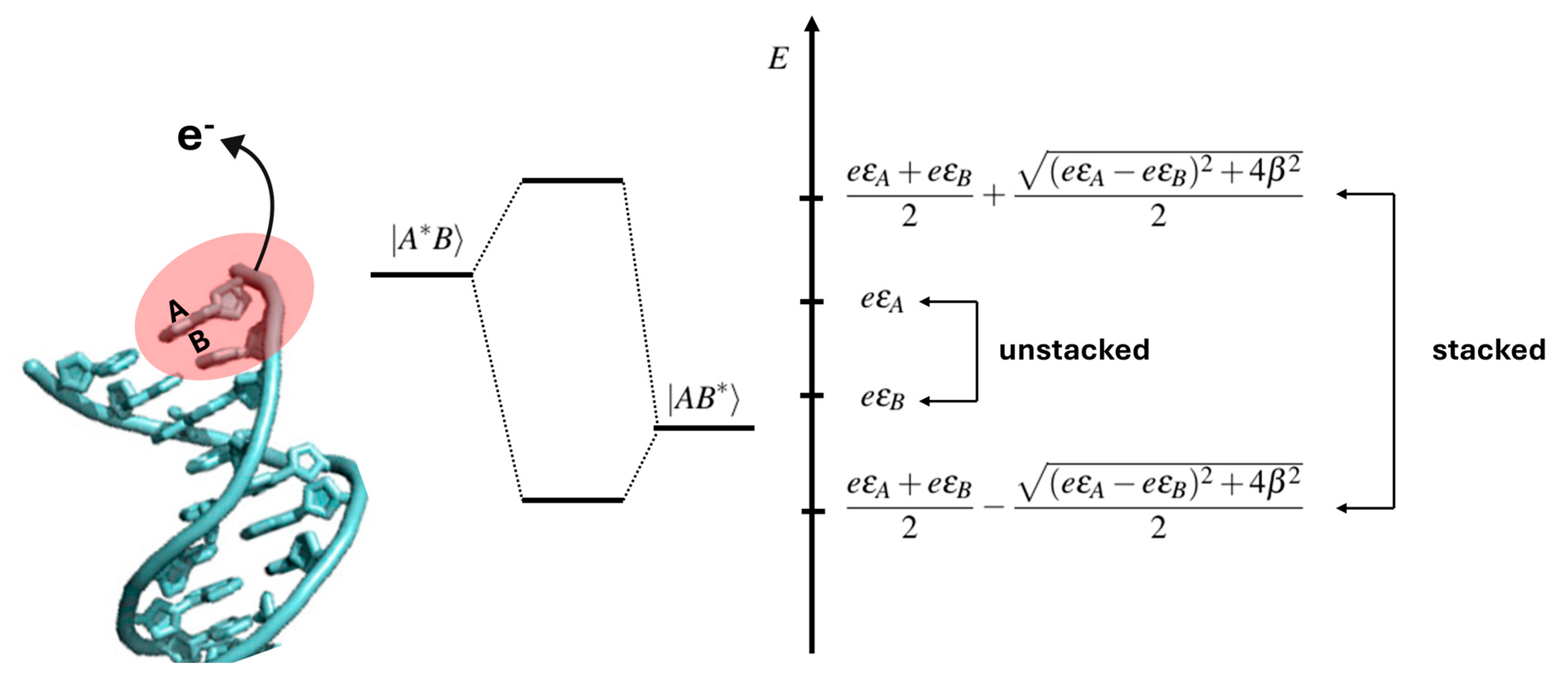

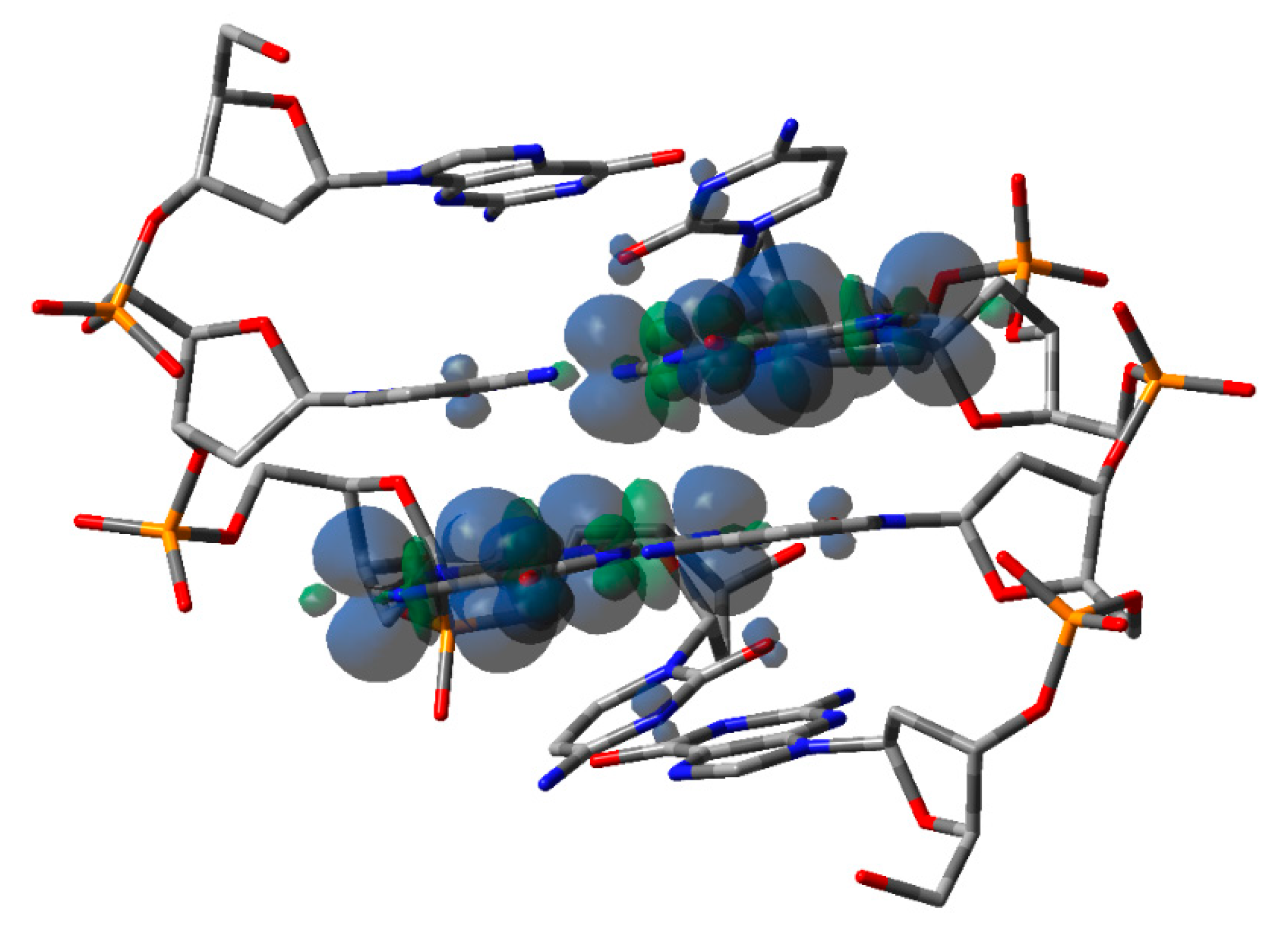

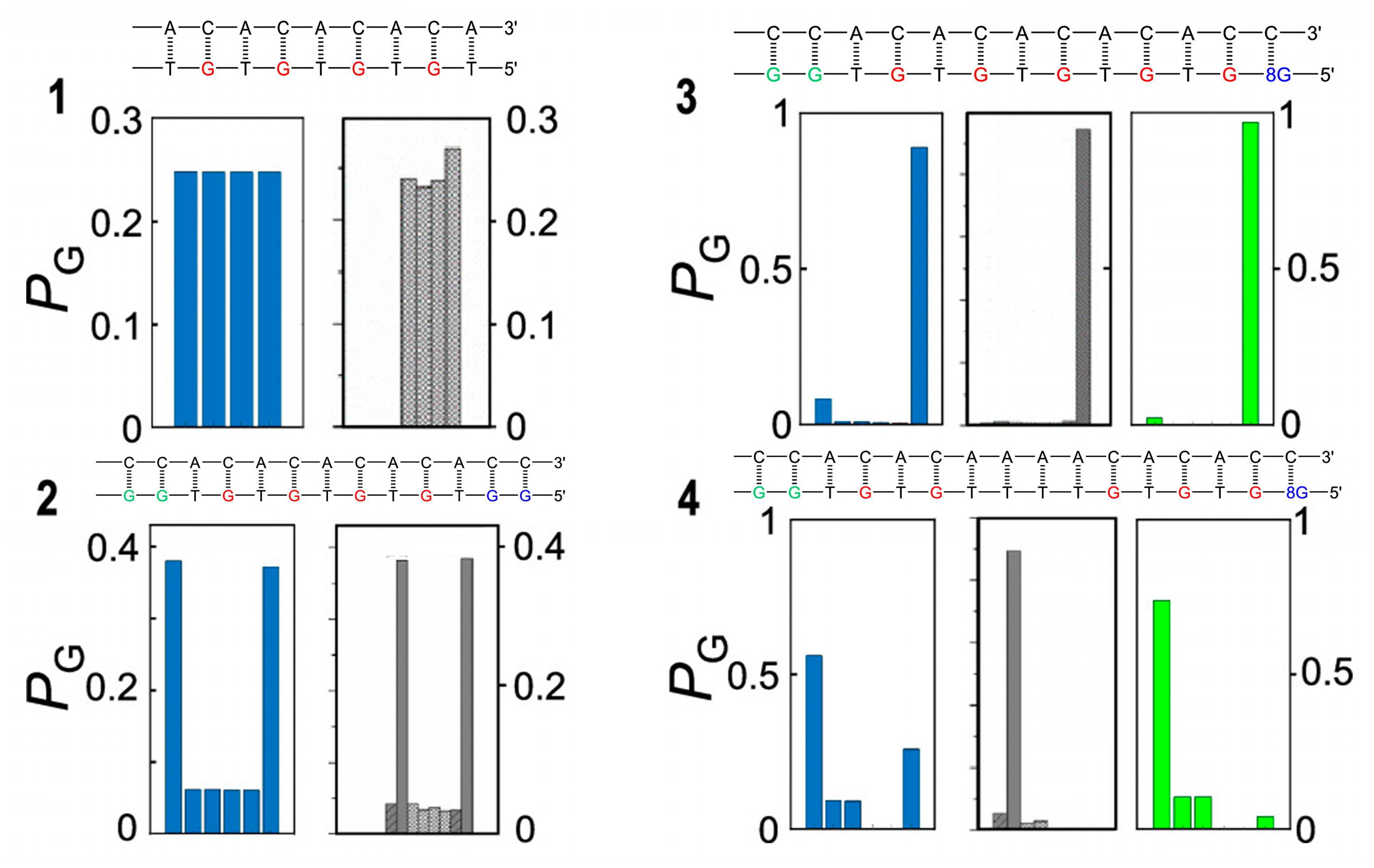

2. In situ Hole Energies in DNA

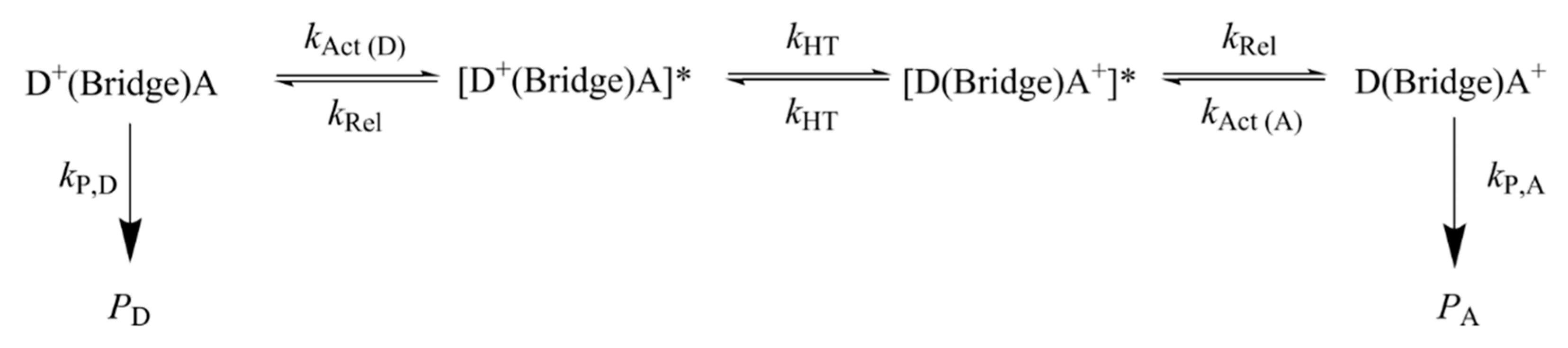

3. Charge Transport

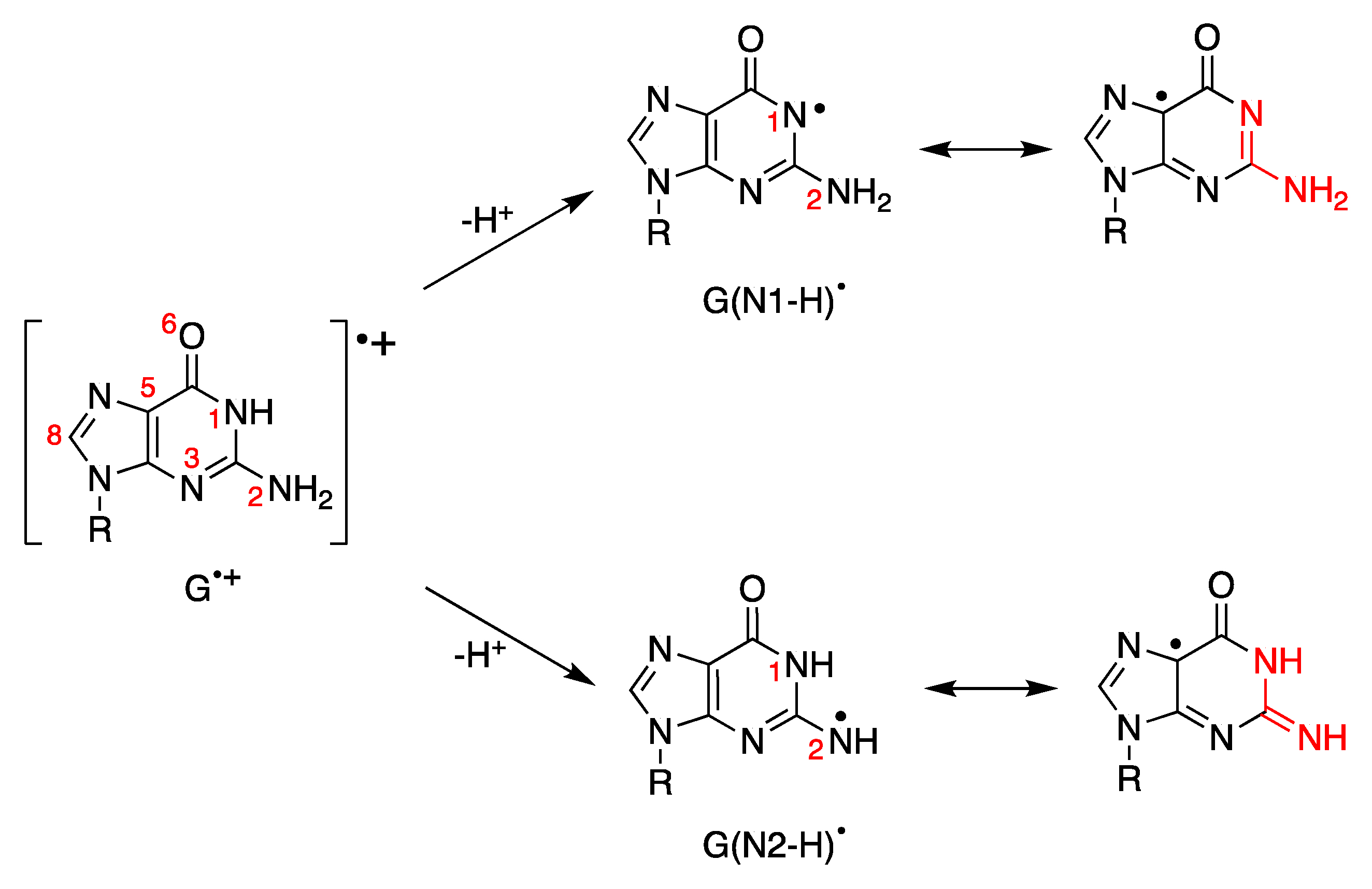

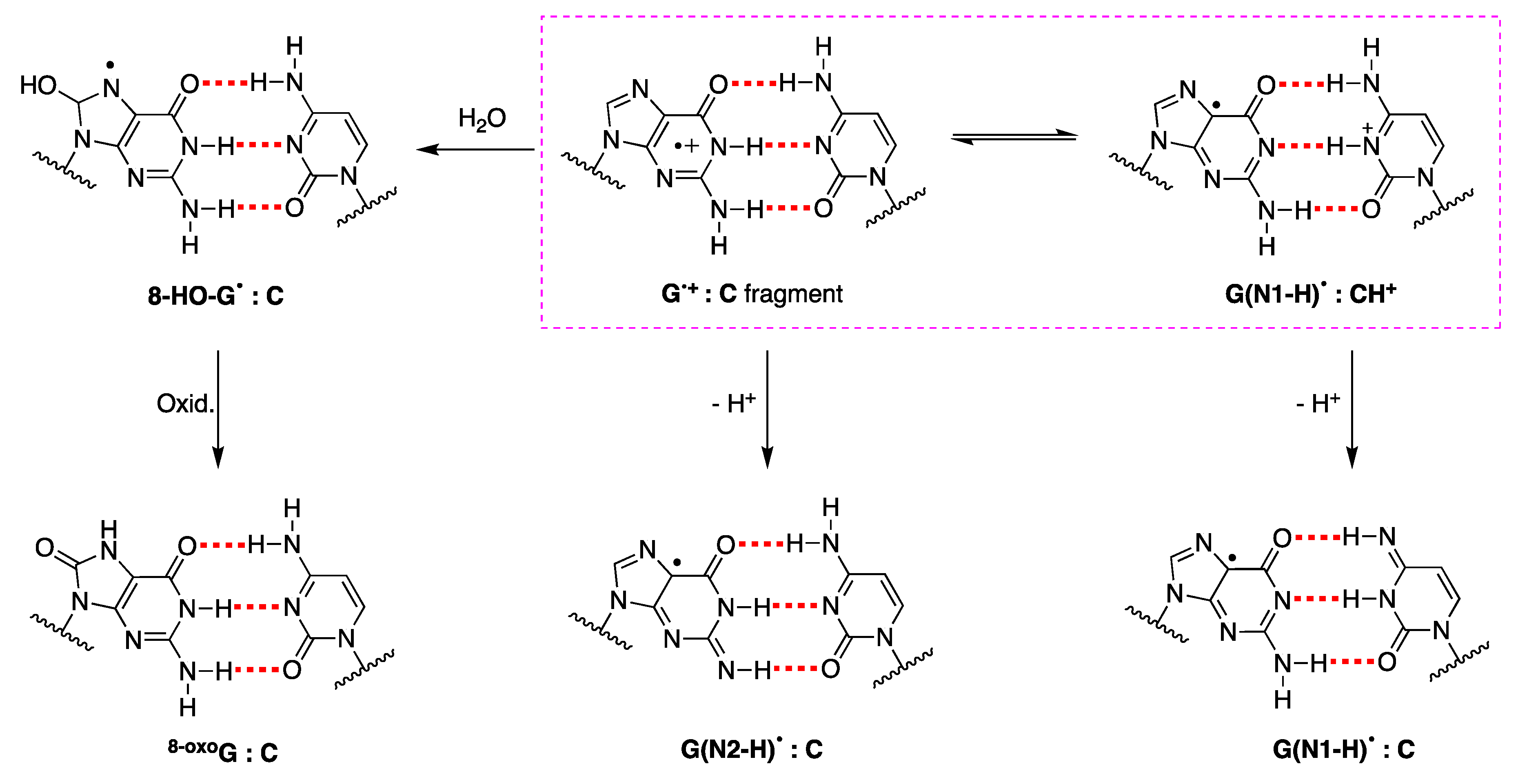

4. Deprotonation vs. Hydrolysis of Guanyl Radical Cation (G•+): From Nucleoside to DNA

5. The Mechanism of the End Products Formation Used as Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paleček, E.; Bartošík, M. Electrochemistry of Nucleic Acids. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3427–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hush, N. S.; Cheung, A. S. Ionization Potentials and Donor Properties of Nucleic Acid Bases and Related Compounds. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1975, 34, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, V.M.; Smirnov, A.N.; Varshavsky, Y.M. Ionization Potentials and Electron-Donor Ability of Nucleic Acid Bases and Their Analogues. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 48, 4377–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, C.A.M.; Schulz, A.; Sauer, M.H.M. Nucleobase-Specific Quenching of Fluorescent Dyes. I. Nucleobase One-Electron Redox Potentials and Their Correlation with Static and Dynamic Quenching Efficiencies. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 5541–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Brett, A.M.; Piedade, J.A.P.; Silva, L.A.; Diculescu, V.C. Voltammetric Determination of All DNA Nucleotides. Anal. Biochem. 2004, 332, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, C. A. ; Pluhařov. , E.; Seidel, R.; Schroeder, W. P.; Faubel, M.; Slav.ček, P.; Winter, B.; Jungwirth, P.; Bradforth, S. E. Oxidation Half-Reaction of Aqueous Nucleosides and Nucleotides via Photoelectron Spectroscopy Augmented by ab Initio Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Slavìček, P.; Winter, B.; Faubel, M.; Bradforth, S. E.; Jungwirth, P. Ionization Energies of Aqueous Nucleic Acids: Photoelectron Spectroscopy of Pyrimidine Nucleosides and ab Initio Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6460–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeias, L. P.; Steenken, S. Structure and acid-base properties of one-electron-oxidized deoxyguanosine, guanosine, and 1-methylguanosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenken, S.; Jovanovic, S.V. How Easily Oxidizable Is DNA? One-Electron Reduction Potentials of Adenosine and Guanosine Radicals in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraggi, M.; Broitman, F.; Trent, J. B.; Klapper, M. H. One-Electron Oxidation Reactions of Some Purine and Pyrimidine Bases in Aqueous Solutions. Electrochemical and Pulse Radiolysis Studies. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 14751–14761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Brett, A. M.; Matysik, J. M. Voltammetric and Sonovoltammetric Studies on the Oxidation of Thymine and Cytosine at a Glassy Carbon Electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1997, 429, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Annibale, V.; Nardi, A. N.; Amadei, A.; D’Abramo, M. Theoretical Characterization of the Reduction Potentials of Nucleic Acids in Solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tòth, Z.; Kubečka, J.; Muchov, E.; Slavìček, P. Ionization Energies in Solution with the QM:QM Approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 10550–10560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, F.; Landi, A; Peluso, A.; Capobianco, A. Quantum Chemical Insights into DNA Nucleobase Oxidation: Bridging Theory and Experiment J. Chem. Theory Comp. 2024, 20, 9708–9719.

- Colson, A.O.; Besler, B.; Sevilla, M.D. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Calculation of DNA Base Pair Radical Ions: Effects of Base Pairing on Proton Transfer Energies, Electron Affinities and Ionization Potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 9787–9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, M.; Clark, T. On the Enhanced Stability of the Guanine−Cytosine Base-Pair Radical Cation J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7574–7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Wata, Y.; Ichinose, N.; Majima, T. Selective Enhancement of the One-Electron Oxidation of Guanine by Base Pairing with Cytosine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 4327–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Wata, Y.; Hara, M.; Toyo, S.; Majima, T. Regulation of One-Electron Oxidation Rate of Guanine by Base Pairing with Cytosine Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3586–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, T.; Carotenuto, M.; Vasca, E.; Peluso, A. Direct Experimental Observation of the Effect of the Base Pairing on the Oxidation Potential of Guanine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15040–15041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, T.; Capobianco, A.; Peluso, A. The Oxidation Potential of Adenosine and Adenosine-Thymidine Base-Pair in Chloroform Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 15347–15353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalsky, O. I.; Panyutin, I. G.; Budowsky, E. I. Sequence-Specificity of Alkali-Sensitive Lesions Induced in DNA by High-Intensity Ultraviolet Laser Radiation. Photochem. Photobiol. 1990, 52, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, I.; Takayama, M.; Sugiyama, H.; Nakatani, K. Photoinduced DNA Cleavage via Electron Transfer: Demonstration That Guanine Residues Located 5′ Guanine Are the Most Electron-Donating Sites. J. Am. Chem.Soc. 1995, 117, 6406–6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J. G.; Hickerson, R. P.; Perez, R. J.; Burrows, C. J. Damage from Sulfite Autoxidation Catalyzed by a Nickel(II) Peptide J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 1501–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, K.; Fujisawa, K.; Dohno, C.; Nakamura, T.; Saito, I. p-Cyano Substituted 5-Benzoyldeoxyuridine as a Novel Electron-Accepting Nucleobase for One-Electron Oxidation of DNA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 5995–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Y.; Kitagawa, Y.; Takano, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nakamura, T.; Saito, I. Experimental and Theoretical Studies on the Selectivity of GGG Triplets toward One-Electron Oxidation in B-Form DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 8712–8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickerson, R. P.; Prat, F.; Muller, J. G.; Foote, C. S.; Burrows, C. J. Sequence and Stacking Dependence of 8-Oxoguanine Oxidation: Comparison of One-Electron vs Singlet Oxygen Mechanisms J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 9423–9428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, K.; Dohno, C.; Saito, I. Modulation of DNA-Mediated Hole-Transport Efficiency by Changing Superexchange Electronic Interaction J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 5893–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanvah, S.; Joseph, J.; Schuster, G. B.; Barnett, R. N.; Cleveland, C. L.; Landman, U. Oxidation of DNA: Damage to Nucleobases. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, A.; Carotenuto, M.; Caruso, T.; Peluso, A. The Charge-Transfer Band of an Oxidized Watson-Crick Guanosine-Cytidine Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9526–9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatgilialoglu, C.; Caminal, C.; Guerra, M.; Mulazzani, Q. G. Tautomers of one-electron oxidized guanosine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 6030–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatgilialoglu, C.; Caminal, C.; Altieri, A.; Vougioukalakis, G. C.; Mulazzani, Q. G.; Gimisis, T.; Guerra, M. Tautomerism in the guanyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13796–13805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S. N.; Davies, R. J. H.; Anderson, D.W.; van Niekerk, J. C.; Nassimbeni, L. R.; MacFarlane, R. D. Photochemical (8→8) coupling of purine nucleosides to guanosine. Nature 1978, 271, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuimova, M. K.; Cowan, A. J.; Matousek, P.; Parker, A.W.; Sun, X. Z.; Towrie, M.; George, M.W. Monitoring the direct and indirect damage of DNA bases and polynucleotides by using time-resolved infrared spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2150–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zundel, G. Hydrogen bonds with large proton polarizability and proton transfer processes in electrochemistry and biology. Adv. Chem. Phys. 2007, 1–217. [Google Scholar]

- Capobianco, A.; Caruso, T.; Celentano, M.; La Rocca, M.V.; Peluso, A. Proton transfer in oxidized adenosine self-aggregates. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 145101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwalb, K.; Temps, F. Base Sequence and Higher-Order Structure Induce the Complex Excited-State Dynamics in DNA. Science 2008, 322, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, A.; Caruso, T.; Celentano, M.; D’Ursi, A.M.; Scrima, M.; Peluso, A. Stacking Interactions between Adenines in Oxidized Oligonucleotides. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 8947–8953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, H.; Saito, I. Theoretical Studies of GG-Specific Photocleavage of DNA via Electron Transfer: Significant Lowering of Ionization Potential and 5′-Localization of HOMO of Stacked GG Bases in B-Form DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7063–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, F.; Houk, K. N.; Foote, C. S. Effect of Guanine Stacking on the Oxidation of 8-Oxoguanine in B-DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 845–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnikov, I. V.; Tong, G. S. M.; Madrid, M.; Beratan, D. N. Hole Size and Energetics in Double Helical DNA: Competition between Quantum Delocalization and Solvation Localization. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F. D.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Hayes, R. T.; Wasielewski, M. R. Dynamics and Equilibria for Oxidation of G, GG, and GGG Sequences in DNA Hairpins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 12037–12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F. D.; Liu, J.; Zuo, Z.; Hayes, R. T.; Wasielewski, M. R. Dynamics and Eergetics of Single-Step Hole Transport in DNA Hairpins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4850–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, C.; Humeniuk, M.; S-Gracz, H.; Marszalek, P. E. Direct Measurements of Base Stacking Interactions in DNA by Single-Molecule Atomic-Force Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 018302–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cysewski, P.; Czyzṅ ikowska, Z.; Zalesń y, R.; Czeleń, P. The Post-SCF Quantum Chemistry Characteristics of the Guanine−Guanine Stacking in B-DNA. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 2665–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, H.; Chang, J.; Abdelwahed, S. H.; Thakur, K.; Rathore, R.; Bard, A. J. Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of π-Stacked Poly(fluorenemethylene) Oligomers. Multiple, Interacting Electron Transfers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16265–16274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, A.; Caruso, T.; Landi, A.; Capobianco, A. The dynamics of hole transfer in DNA. Molecules 2019, 24, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, A.; Caruso, T.; D’Ursi, A. M.; Fusco, S.; Masi, A.; Scrima, M.; Chatgilialoglu, C.; Peluso, A. Delocalized Hole Domains in Guanine-Rich DNA Oligonucleotides. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 5462–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hassan, M.A.; Calladine, C.R. Conformational Characteristics of DNA: Empirical Classifications and a Hypothesis for the Conformational Behaviour of Dinucleotide Steps. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 1997, 355, 43–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calladine, C.R.; Drew, H.; Luisi, B.; Travers, A. Understanding DNA: The Molecule and How it Works, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Sevilla, M. D. Density Functional Theory Studies of the Extent of Hole Delocalization in One-Electron Oxidized Adenine and Guanine Base Stacks. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 4990–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, A.; Caruso, T.; Peluso, A. Hole Delocalization over Adenine Tracts in Single Stranded DNA Oligonucleotides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 4750–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.A.; Mishra, A.K.; Young, R.M.; Brown, K.E.; Wasielewski, M.R.; Lewis, F.D. Direct Observation of the Hole Carriers in DNA Photoinduced Charge Transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5491–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, H.; Saito, I. Theoretical Studies of GG-Specific Photocleavage of DNA via Electron Transfer: Significant Lowering of Ionization Potential and 50-Localization of HOMO of Stacked GG Bases in B-form DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7063–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, K.; Grozema, F.C.; Fonseca Guerra, C.; Bickelhaupt, F.M.; Siebbeles, L.D.A. Mapping the Sites for Selective Oxidation of Guanines in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 13658–13659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sevilla, M.D. Photoexcitation of Dinucleoside Radical Cations: A Time-Dependent Density Functional Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 24181–24188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

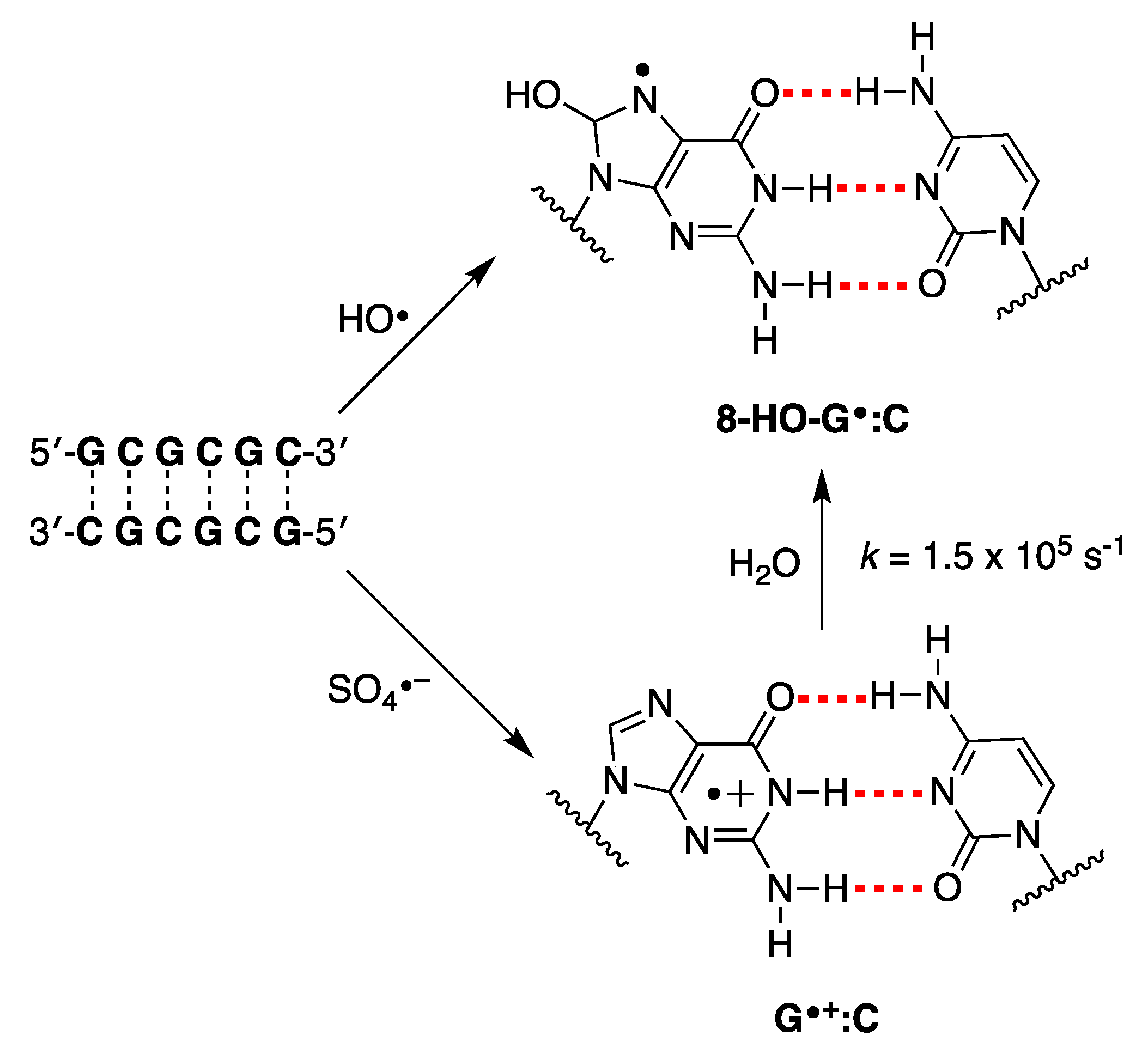

- Masi, A.; Capobianco, A.; Bobrowski, K.; Peluso, A.; Chatgilialoglu, C. Hydroxyl Radical vs. One-Electron Oxidation Reactivities in an Alternating GC Double-Stranded Oligonucleotide: A New Type Electron Hole Stabilization. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Tao, N. Direct Conductance Measurement of Single DNA Molecules in Aqueous Solution. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallajosyula, S.S.; Pati, S.K. Toward DNA Conductivity: A Theoretical Perspective. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 1881–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, A.; Peluso, A. The oxidization potential of AA steps in single strand DNA oligomers. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 47887–47893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basko, D.M.; Conwell, E.M. Effect of Solvation on Hole Motion in DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 098102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conwell, E.M.; Bloch, S.M.; McLaughlin, P.M.; Basko, D.M. Duplex Polarons in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 9175–9181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M.A.; Barton, J.K. DNA Charge Transport: Conformationally Gated Hopping through Stacked Domains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11471–11483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, B.; Amaudrut, J.; Köhler, A.K.; Spormann, M.; Wessely, S. Direct Observation of Hole Transfer through DNA by Hopping between Adenine Bases and by Tunneling. Nature 2001, 412, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eley, D. D.; Spivey, D. I. Semiconductivity of Organic Substances Part 9. Nucleic Acid in Dry State. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1962, 58, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C. J.; Arkin, M. R.; Jenkins, Y.; Ghatlia, N. D.; Bossmann, S. H.; Turro, N. J.; Barton, J. K. Long-Range Photoinduced Electron-Transfer through a DNA Helix. Science 1993, 262, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endres, R.G.; Cox, D.L.; Singh, R.R.P. The Quest for High-Conductance DNA. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2004, 76, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Sariciftci, N.S.; Grote, J.G.; Hopkins, F.K. Bio-Organic-Semiconductor-Field-Effect-Transistor Based on Deoxyribonucleic Acid Gate Dielectric. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100, 024514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalar, P.; Kamkar, D.; Naik, R.; Ouchen, F.; Grote, J.G.; Bazan, G.C.; Nguyen, T.Q. DNA Electron Injection Interlayers for Polymer Light-Emitting Diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11010–11013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zalar, P.; Kim, C.; Collins, S.; Bazan, G.C.; Nguyen, T.Q. DNA Interlayers Enhance Charge Injection in Organic Field-Effect Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 4255–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, E.F.; Venkatraman, V.; Grote, J.G.; Steckl, A.J. Exploring the Potential of Nucleic Acid Bases in Organic Light Emitting Diodes. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7552–7562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, B. Long Distance Electron Transfer through DNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F.D.; Letsinger, R.L.; Wasielewski, M.R. Dynamics of Photoinduced Charge Transfer and Hole Transfer in Synthetic DNA Hairpins. Acc. Chem Res. 2001, 34, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genereux, J.C.; Barton, J.K. Mechanisms for DNA Charge Transport. Chem Rev. 2010, 110, 1642–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, K.; Majima, T. Hole Transfer Kinetics of DNA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2616–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, A.R.; Grodick, M.A.; Barton, J.K. DNA Charge Transport: Principles to the Cell. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, A.; Borrelli, R.; Capobianco, A.; Peluso, A. Transient and Enduring Electronic Resonances Drive Coherent Long Distance Charge Transport in Molecular Wires. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 1845–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, A.; Capobianco, A.; Peluso, A. Coherent Effects in Charge Transport in Molecular Wires: Toward a Unifying Picture of Long-Range Hole Transfer in DNA. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 7769–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixon, M.; Giese, B.; Wessely, S.; Langenbacher, T.; Michel-Beyerle, M.E.; Jortner, J. Long-Range Charge Hopping in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 11713–11716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, N.; Berlin, Y.A.; Lewis, F.D.; Ratner, M.A. Between Superexchange and Hopping: An Intermediate Charge-Transfer Mechanism in polyA-polyT DNA Hairpins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3953–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renger, T.; Marcus, R.A. Variable Range Hopping Electron Transfer Through Disordered Bridge States: Application to DNA. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 8404–8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixon, M.; Jortner, J. Incoherent Charge Hopping and Conduction in DNA and Long Molecular Chains. Chem. Phys. 2005, 319, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozema, F. C.; Tonzani, S.; Berlin, Y. A.; Schatz, G. C.; Siebbeles, L. D. A.; Ratner, M. A. Effect of Structural Dynamics on Charge Transfer in DNA Hairpins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5157−5166.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Balaeff, A.; Skourtis, S. S.; Beratan, D. N. Biological Charge Transfer via Flickering Resonance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10049–10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A. D.; Iv, M.; Peskin, U. Length-Independent Transport Rates in Biomolecules by Quantum Mechanical Unfurling. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo,A.; Peluso, A. Electron Transfer Rates in Polar and Non-Polar Environments: a Generalization of Marcus’ Theory to Include an Effective Treatment of Tunneling Effects. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 9148–9155.

- Borrelli, R.; Capobianco, A.; Landi, A.; Peluso, A. Vibronic couplings and coherent electron transfer in bridged systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 30937–30945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelli, R.; Di Donato, M. Peluso, A. Role of intramolecular vibrations in long-range electron transfer between pheophytin and ubiquinone in bacterial photosynthetic reaction centers. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

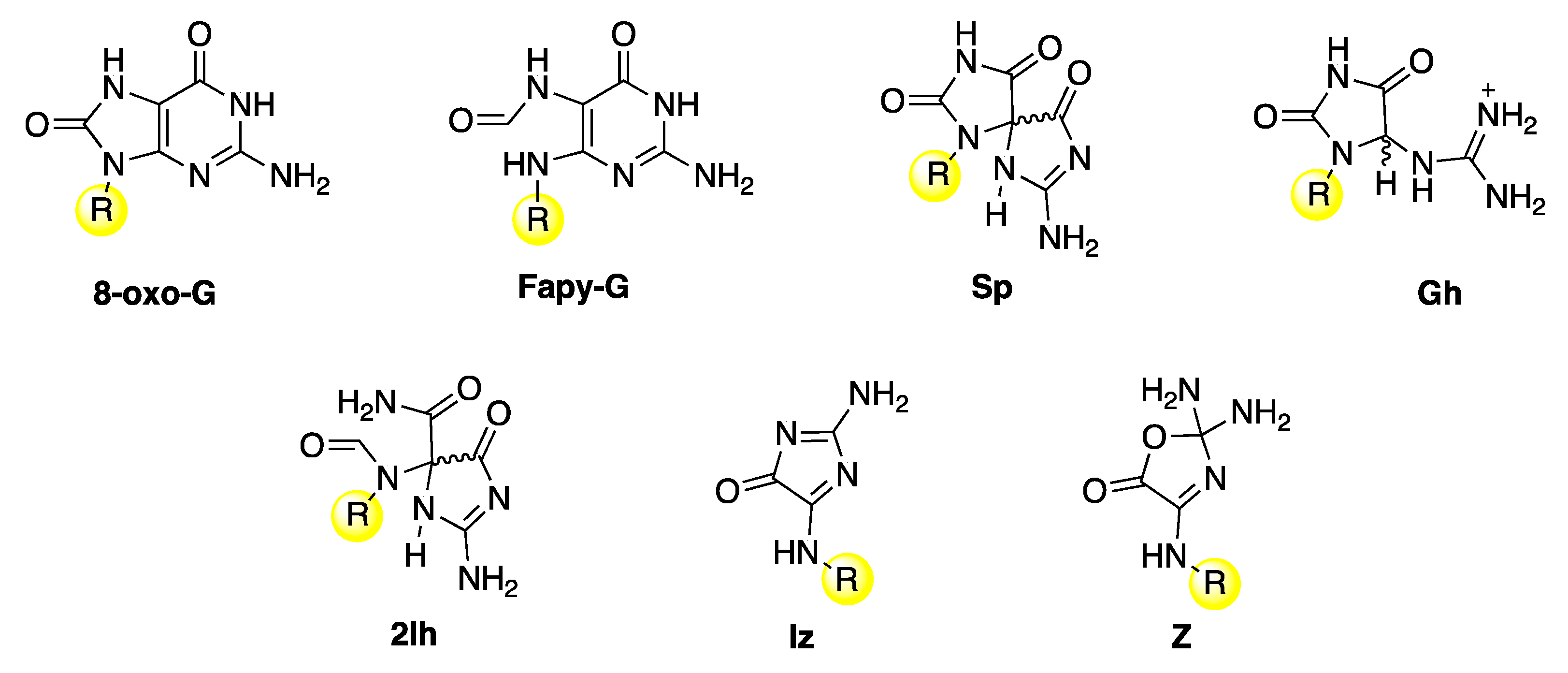

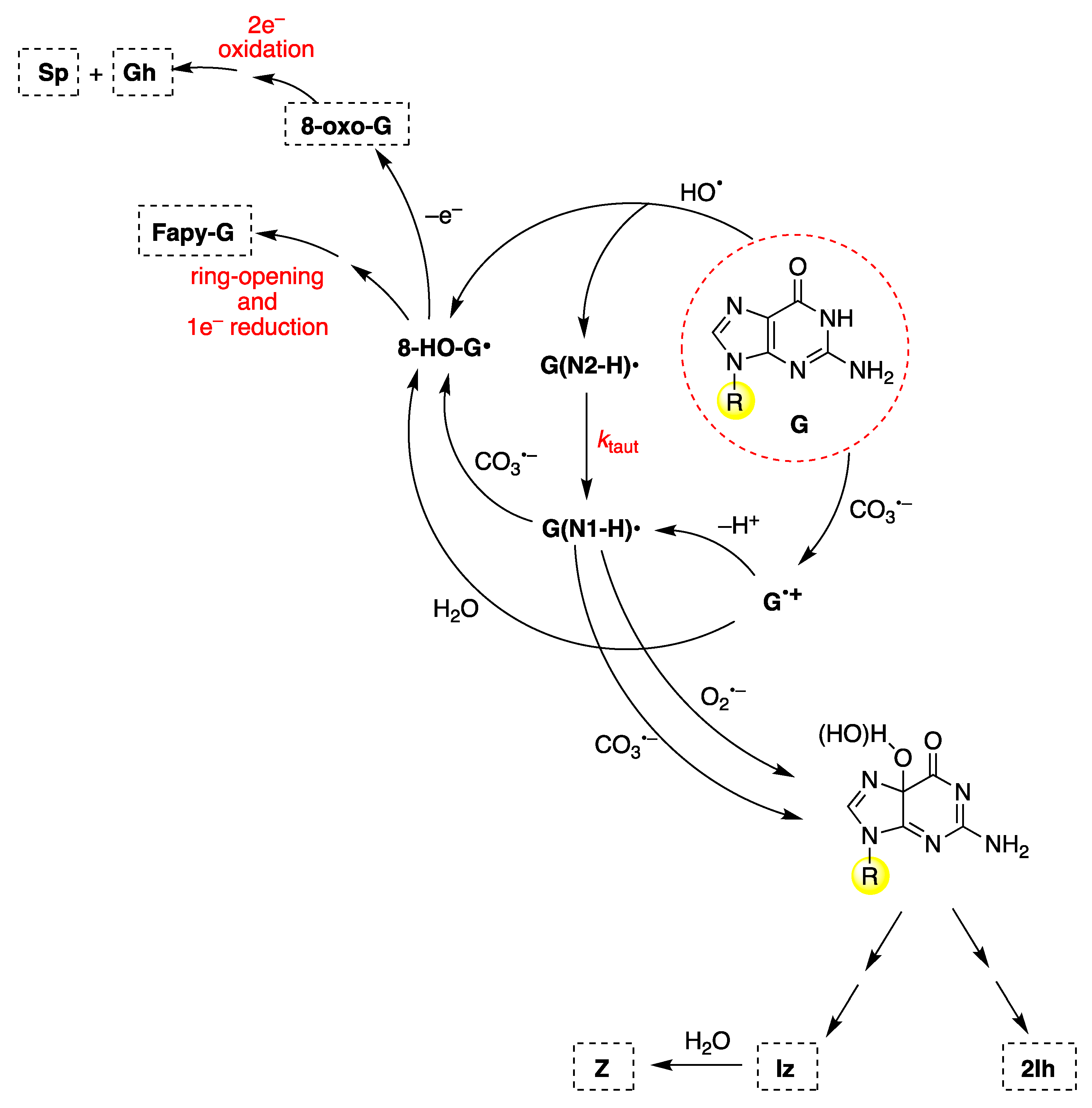

- Chatgilialoglu, C. The Two Faces of the Guanyl Radical: Molecular Context and Behavior. Molecules 2021, 26, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenken, S. Purine bases, nucleosides, and nucleotides: aqueous solution redox chemistry and transformation reactions of their radical cations and e– and OH adducts. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNA Damage, DNA Repair and Disease; Dizdaroglu, M., Lloyd, R. S., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Croydon, UK, 2021.

- Zhang, X.; Jie, J.; Song, D.; Su, H. Deprotonation of Guanine Radical Cation G•+ Mediated by the Protonated Water Cluster. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 6076–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatgilialoglu, C.; D’Angelantonio, M.; Guerra, M.; Kaloudis, P.; Mulazzani, Q. G. A reevaluation of the ambident reactivity of guanine moiety towards hydroxyl radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2214–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatgilialoglu, C.; D’Angelantonio, M.; Kciuk, G.; Bobrowski, K. New insights into the reaction paths of hydroxyl radicals with 2’-deoxyguanosine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 2200–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, A.; Kumar, A.; Becker, D.; Sevilla, M. D. The Guanine Cation Radical: Investigation of Deprotonation States by ESR and DFT. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 24171–24180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, A.; Khanduri, D.; Sevilla, M. D. Direct observation of the hole protonation state and hole localization site in DNA-oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 8614–8619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Yamagami, R.; Tagawa, S. Effect of base sequence and deprotonation of guanine cation radical in DNA. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 10752–10757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokhlenko, Y.; Cadet, J.; Geacintov, N.E.; Shafirovich, V. Mechanistic aspects of hydration of guanine radical cations in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5956–5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banyasz, A.; Martínez-Fernández, L.; Improta, R.; Ketola, T.-M.; Balty, C.; Markovitsi, D. Radicals generated in alternating guanine cytosine duplexes by direct absorption of low-energy UV radiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 21381–21389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balanikas, E.; Banyasz, A.; Baldacchino, G.; Markovitsi, D. Populations and Dynamics of Guanine Radicals in DNA strands— Direct versus Indirect Generation. Molecules 2019, 24, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanikas, E.; Banyasz, A.; Douki, T.; Baldacchino, G.; Markovitsi, D. Guanine Radicals Induced in DNA by Low-Energy Pho- toionization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanikas, E.; Banyasz, A.; Baldacchino, G.; Markovitsi, D. Deprotonation Dynamics of Guanine Radical Cations. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, A.; Kumar, A.; Munafo, S.A.; Khanduri, D.; Sevilla, M.D. Prototropic equilibria in DNA containing one-electron oxidized GC:intra-duplex vs. duplex to solvent deprotonation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 5353–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, J.; Wagner, J.R. Oxidatively generated base damage to cellular DNA by hydroxyl radical and one-electron oxidants: Similarities and differences. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 557, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatgilialoglu, C.; Krokidis, M.G.; Masi, A.; Barata-Vallejo, S.; Ferreri, C.; Terzidis, M.A.; Szreder, T.; Bobrowski, K. New insights into the reaction paths of hydroxyl radicals with purine moieties in DNA and double-stranded oligonucleotides. Molecules 2019, 24, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sevilla, M. D. Influence of Hydration on Proton Transfer in the Guanine—Cytosine Radical Cation (G•+—C) Base P air: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 11359–11361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenken, S.; Reynisson, J. DFT calculations on the deprotonation site of the one-electron oxidised guanine–cytosine base pair. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 9088–9093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Requena, A.; Perpète, E.A.; Michaux, C.; Jacquemin, D. Theoretical Study of the Tautomerism in the One-Electron Oxidized Guanine-Cytosine Base Pair. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 13439–13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sevilla, M. D. Excited States of One-Electron Oxidized Guanine-Cytosine Base Pair Radicals: A Time Dependent Density Functional Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 3098–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Eriksson, L.A. Effects of OH Radical Addition on Proton Transfer in the Guanine-Cytosine Base Pair. J Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 6571–6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Jacquemin, D. Interplay between hydroxyl radical attack and H-bond stability in guanine–cytosine. RCS Adv. 2012, 2, 11867–11875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, S. Influence of hydrogen bonds on the reaction of guanine and hydroxyl radical: DFT calculations in C(H+)GC motif. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 5683–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

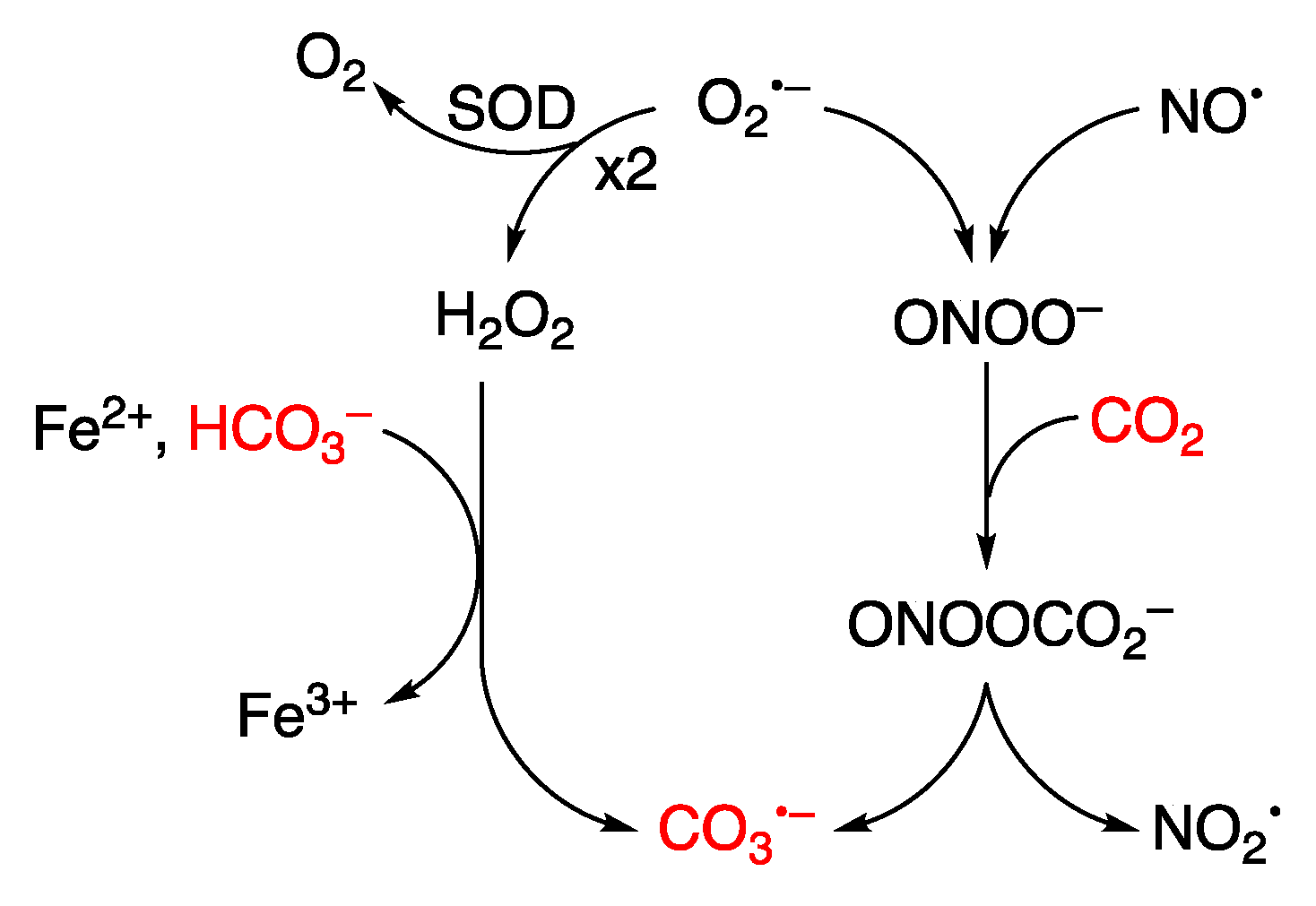

- Pacher, P.; Beckman, J.S.; Liaudet, L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 315–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.N.; Denicola, A. Diffusion of peroxynitrite, its precursors, and derived reactive species, and the effect of cell membranes. Redox Biochem. Chem. 2024, 9, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, E.; Patra, S.G.; Marks, V.; Mizrahi, A.; Meyerstein, D. The FeII(citrate) Fenton reaction under physiological conditions. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 206, 111018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounds, P.L.; Koppenol, W.H. Peroxynitrite: A tale of two radicals, Redox Biochem. Chem. 2024, 10, 100038. [Google Scholar]

- Shafirovich, V.; Dourandin, A.; Huang, W.; Geacintov, N.E. The carbonate radical is a site-selective oxidizing agent of guanine in double-stranded oligonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 24621–24626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crean, C.; E. Geacintov, N.E.; Shafirovich, V. Oxidation of Guanine and 8-oxo-7,8-Dihydroguanine by Carbonate Radical Anions: Insight from Oxygen-18 Labeling Experiments. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5057–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, A.M.; Burrows, C.J. Iron Fenton oxidation of 2′-deoxyguanosine in physiological bicarbonate buffer yields products consistent with the reactive oxygen species carbonate radical anion not hydroxyl radical. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 9779–9782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, A.M.; Burrows, C. Chemistry of ROS-mediated oxidation to the guanine base in DNA and its biological consequences. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2022, 98, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaruga, P.; Kirkali, G.; Dizdaroglu, M. Measurement of formamidopyrimidines in DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizdaroglu, M.; Kirkali, G.; Jaruga, P. Formamidopyrimidines in DNA: mechanisms of formation, repair, and biological effects. Free Radic. Biol Med. 2008, 45, 1610–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizdaroglu, M. Oxidatively induced DNA damage and its repair in cancer. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2015, 763, 212–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M. M. The formamidopyrimidines: purine lesions formed in competition with 8-oxopurines from oxidative stress. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenken, S.; Jovanovic, S. V.; Bietti, M.; Bernhard, K. The trap depth (in DNA) of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’deoxyguanosine as derived from electron-transfer equilibria in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 2373–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A. M.; Muller, J. G.; Dlouhy, A. C.; Burrows, C. J. Structural context effects in the oxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine to hydantoin products: electrostatics, base stacking, and base pairing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15091–15102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, M.B.; Fleming, A.M.; Burrows, C. J. Insights into the 5-carboxamido-5-formamido-2-iminohydantoin structural isomerization equilibria. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 11865–11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, A. M.; Muller, J. G.; Ji, I.; Burrows, C. J. Characterization of 2’-deoxyguanosine oxidation products observed in the Fenton-like system Cu(II)/H2O2/reductant in nucleoside and oligodeoxynucleotide contexts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 3338–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshykhly, O. R.; Fleming, A. M.; Burrows, C. J. 5-Carboxamido-5-formamido-2-iminohydantoin, in Addition to 8-oxo-7,8-Di-hydroguanine, Is the Major Product of the Iron-Fenton or X-ray Radiation-Induced Oxidation of Guanine under Aerobic Reducing Conditions in Nucleoside and DNA Contexts. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 6996–7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; An, P.; Li, S.; Zhou, L. The oxidation mechanism and kinetics of 2′-deoxyguanosine by carbonate radical anion. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 739, 136982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiaszek, R.; Crean, C.; Joffe, A.; Geacintov, N. E.; Shafirovich, V. Oxidative DNA damage associated with combination of guanine and superoxide radicals and repair mechanisms via radical trapping. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 32106–32115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiaszek, R.; Crean, C.; Geacintov, N. E.; Shafirovich, V. Combination of Nitrogen Dioxide Radicals with 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine and Guanine Radicals in DNA: Oxidation and Nitration End-Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, A.; Mock, S.; Yun, B. H.; Kolbanovskiy, A.; Geacintov, N. E.; Shafirovich, V. Oxidative Generation of Guanine Radicals by Carbonate Radicals and Their Reactions with Nitrogen Dioxide to Form Site Specific 5-Guanidino-4-nitroimidazole Lesions in Oligodeoxynucleotides. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003, 16, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, S.P.; Bernhard Schlegel, H.B. Computational Investigation into the Oxidation of Guanine to Form Imidazolone (Iz) and Related Degradation Products. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 1010–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Ye, W.; Prestwich, E.G.; Wishnok, J.S.; Taghizadeh, K.; Dedon, P.C.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Comparative analysis of four oxidized guanine lesions from reactions of DNA with peroxynitrite, single oxygen, and γ-radiation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013, 26, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matter, B.; Seiler, C. L.; Murphy, K.; Ming, X.; Zhao, J.; Lindgren, B.; Jones, R.; Tretyakova, N. Mapping three guanine oxidation products along DNA following exposure to three types of reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 121, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.M.; Burrows, C.J. Formation and processing of DNA damage substrates for the hNEIL enzymes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 107, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatgilialoglu, C.; Eriksson, L.A.; Krokidis, M.G.; Masi, A.; Wang, S.-D.; Zhang, R. Oxygen dependent purine lesions in double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides: Kinetic and computational studies highlight the mechanism for 5’,8-cyplopurine formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5825–5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatgilialoglu, C.; Ferreri, C.; Krokidis, M.G.; Masi, A.; Terzidis, M.A. On the relevance of hydroxyl radical to purine DNA damage. Free Radic. Res. 2021, 55, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergeron, F.; Auvre, F.; Radicella, J.P.; Ravanat, J.-L. HO• radicals induce an unexpected high proportion of tandem base lesions refractory to repair by DNA glycosylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5528–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).