1. Introduction

Present fuel system infrastructure sustainment efforts require frequent fuel quality and contaminant testing, to prevent clogging of fuel lines and replacement of fuel system parts that are affected by biofouling and bio-based corrosion [

1,

2,

3]. The identification of specialized microbes that that can use jet fuel hydrocarbons as a substrate and the study microbial metabolism and biofilm formation has given insight into potential antimicrobial treatment options [

3,

4,

5,

6]. For instance, microbes can achieve antimicrobial resistance via multiple biochemical pathways, that include activation of solvent tolerance

via activating efflux pumps as well as biofilm formation [

5,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In previous efforts, our group tested the use of small-molecule efflux pump blockers in the treatment of fuel microbial contamination. This research effort tries to identify natural biocontrol compounds that are intrinsically produced by microbes that can be applied along with efflux pump inhibitors as a combinatorial strategy to overcome microbial resistance in fuel tanks.

Laboratory screening for novel antimicrobials has utilized the competitive nature of environmental consortium microbes where nutrient-competing strains produce inhibitory compounds to block other competitors [

11,

12,

13,

14]. One class of bacterial and fungal biocides, with relatively higher stability includes antimicrobial peptides (AMP) [

13,

15]. The mechanism of action of most AMP is either through inhibition of cell division by causing intracellular toxicity or through exterior membrane permeabilization [

13]. Recently, our group demonstrated the application of sheep myeloid antimicrobial peptide (SMAP-18) and synthetic pyochelin in treatment of fuel biocontamination [

16].

In this study, 493 microbial fuel isolates from our in-house repository were tested for antimicrobials activity against target microbes by agar plug screening to identify potential biocontrol compounds that are naturally produced and target other fuel system microorganisms. Agar plug diffusion screening represents a common and well-established method to screen for antimicrobials activity throughout the microbiology community [

17,

18]. To distinguish between potential cell-to-cell interactions and compound-dependent antimicrobial growth inhibition, we established a liquid culture screening assay to confirm production of soluble biocontrol compounds in microbial culture filtrates. Using these methods, two fuel-isolate strains

Pseudomonas protegens #133 and

Bacillus subtilis #232 demonstrated promising biocontrol activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, yeast and filamentous fungi. According to previous studies,

B. subtilis is known to produce over 200 antimicrobial compounds including bacillaene, bacilysin, surfactin [

19], and lipopeptides such as gageostatins and gageopeptins [

20,

21,

22] iturins and fengycins [

19,

23], polyketide macrolactins [

20,

24,

25], and volatile organic compounds (VOG) with antifungal properties [

23,

26,

27]. In contrast, most of the antimicrobial compounds produced by

P. protegens include small molecules and lipid compounds such as rhamnolipids and quorum sensing molecules including pyoverdine, pyocyanin, and pyochelin [

28].

To identify potential compounds contained within #133 and #232 culture filtrates, this study used high performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry with an Agilent 6546 Q-TOF mass analyzer. Our selection criteria for antimicrobial compound screening included good molecular stability in the fuel phase with semi-polar characteristics allowing diffusion in the water/biofilm phase, without producing fuel emulsification. To better characterize compounds that match these criteria, two different culture filtrate purification methods were used including ethyl acetate liquid/liquid extraction for purification of semi-polar compounds such as lipids and lipopeptides and semi-preparative HPLC for purification of lipopeptide compounds. Crude culture filtrates and extracts of purified compounds were further tested using liquid culture screening assays and Jet A fuel microbial consortium culture testing. To further assess the mode of actions of the identified antimicrobials, flow cytometry (FCM) was used to detect cellular viability and structural morphology for determination of cell death [

29,

30,

31]. Knowing the mode of action of these antimicrobials is helpful for designing future combinatorial mitigation strategy. Using FCM as a tool, we were able to estimate live/dead, and viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells after microbes were exposed to the novel antimicrobial compounds and made assumptions about the underlying mechanism of action of the identified biocontrol agents. The subsequent findings show promising results for the use of #133 crude culture filtrate as a biocontrol agent for Gram-positive bacteria with notable bactericidal efficacy against the fuel contaminant

Gordonia sp.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

Pyochelin I/II (Cat#sc-506665 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA). The filamentous fungi Hormoconis resinae (ATCC 22711), yeast Yarrowia lipolytica (ATCC 20496), and Gram-positive bacterium Gordonia sp. (ATCC BAA-559) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). The Pseudomonas putida bacteria and Meyerozyma guilliermondii were obtained from AFRL microbial repository, isolated from bio-contaminated fuel samples). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 bacteria represent a laboratory strain (taxonomy ID 208964.1).

2.2. Colony Forming Unit Determination

For colony forming units (CFU)/mL determination, 200 µL of culture samples were collected, serial diluted and plated onto agar media. Plates were incubated at 28 °C overnight followed by CFU counting. Three replicates of different dilutions were either plated manually or by using an easySpiral Pro Plater (Interscience, Woburn, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. CFU/mL was either determined by counting colonies on manually spread plates or by using the automatic plate reader Scan 1200 Colony Counter (Interscience, Woburn, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.3. Agar Plug Diffusion Testing

Donor and recipient test microbes were plated on agar culture plates with growth medium e.g., Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA, REF 236950, Difco), or Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, REF 213400, Difco) and incubated at 28 °C for 1-3 days. To generate plates, bacterial cells or fungal spores were directly suspended into the 50% agar medium at 1 x 106 fungal spores or bacteria cells/mL as the final concentration to allow for evenly distribution of microbes throughout the dried plate. Donor plates were punched with 5 mm sterile cork borers that were excised to produce agar plate plugs. The excised donor plugs were placed onto the recipient plate containing the test microbes. Following addition of plugs, plates were incubated at 28 °C overnight. Control plates only received non-inoculated plugs. After incubation, radius of inhibition zones from control and treatment are measured in mm at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after incubation. Following live (SYTO 9; green)/dead (Propidium iodide; red) cell staining with BacLight (Molecular probes) fluorescence microscope images, including phase-contrast images and SEM microscopic images were taken from the agar plug edges.

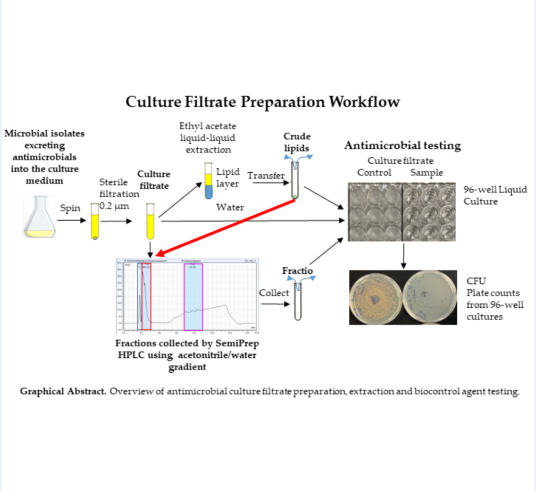

2.4. Purification of Culture Filtrates for Antimicrobial Testing

Isolates were pre-cultured from frozen stock and grown overnight at 28 °C on either Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) for bacterial or Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) for fungal cultures. The next day, one colony was transferred to 20 mL liquid culture containing Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) and incubated overnight under agitation (200 revolutions per minute, (RPM)) at 28 °C. For fungal cultures, the spores were scraped off at 72 hours incubation and filtered with a 0.2 µm filter to only collect the spores, then steps were continued in a similar fashion. The next day, liquid cultures were washed 3x with Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by serial dilution and incubation over-night at 28 °C for CFU determination. According to the CFU, 3 x 107 cells/ mL of isolate were added to 25 mL of M9 minimum medium supplemented with 0.5% glycerol. Samples were placed in a 28 °C shaking incubator at 200 rpm for 24-72 hours. 1 mL of liquid culture was diluted and plated to get the CFU count of the isolate. To generate culture filtrates, cultures were spun down at 8500 RPM for 10 min and filtered with 0.2 µm nylon filters (Corning Cat. # 431224). The absorbance of culture filtrates was read at 205 and 254 nm in a Nanodrop (Nanodrop 2000c, Thermo Scientific) instrument to obtain the protein, peptide and lipid concentration. Prior to use in experiments, an aliquot of culture filtrates was plated to assure complete removal of microbial cells. For 96-well liquid culture testing, and fuel consortium culture testing, the #232 and #133 crude culture filtrates were dried down by nitrogen evaporation and re-diluted in the assay buffers with a stock concentration of 1 mg/mL. The reconstituted crude filtrate stock solutions were sterile filtered with a 0.2 µm filter and added to the experiments according to the given final concentrations at 25, 50, 100 or 500 µg/mL.

2.5. Antimicrobial Liquid Culture Screening Assay

Liquid media culture studies were performed in 96-well plates with 200 µL total volume using either M9 minimum medium/0.5% glycerol (bacteria) or yeast nitrogen basewithout amino acids (YNB)/0.5% glycerol (fungi), followed by inoculation with or without (medium control) the test microbial strains Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi at a final concentration of 1 x 104 cells/mL with at least three replicates. Cultures were supplemented with the corresponding test culture filtrate at 1:1 v/v e.g. 100 µl containing a concentration of 1.38 mg/mL of isolate #133 dry weight or 1.96 mg/mL dry weight for isolate #232 over a course of 14 days. To account for enhanced evaporation on the plate edge, samples were plated in the middle of the 96-well plate by leaving the edges unfilled prior to addition of the clear sterile plate sealing membrane. Prior to and after sample collection at the corresponding time points, plates were spun for 10 min at 3,000 RPM to remove condensation. Serial dilutions were made prior to CFU culture plating.

2.6. Fuel Microbial Consortium Culture Assay

Fuel microbial consortium culture was performed in a 40 mL glass vials using 20 mL Jet A fuel as a carbon source underlain with 5 mL water bottom containing minimal growth media in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of M9 medium/YNB. Fuel cultures were inoculated with a microbial consortium of gram-negative bacteria: P. putida, Gram-positive bacteria: Gordonia sp., yeast: Y. lipolytica, and filamentous fungi: H. resinae at a final concentration of 1 x 104 cells/mL containing an equal amount of each microbe. Cultures were supplemented with the chosen antimicrobials, e.g., crude culture filtrate at doses of 0.0 µg/mL (microbial growth control) administered at 100 µl (1.38 mg/mL), 1 mL (13.8 mg/mL) and 2.5 mL (34.5 mg/mL) total volume followed by incubation at 28 ºC without agitation. Samples were taken over a course of 29 days. 200 µL of each sample was collected across different time points and serial dilutions were made for CFU culture plating. Three technical samples were collected from each bottle for CFU culture plating on TSA plates (bacteria) and PDA supplemented with ampicillin, kanamycin, and spectinomycin at 50 µg/mL (fungi).

2.7. Culture Filtrate Compound Purification by Ethyl Acetate Lipid Extraction

For lipid extraction, microbes were grown for three days at a staring concentration of 3 x 107 cells/mL in M9 minimum medium supplemented with 0.5% glycerol prior to sterile filtration with a 0.2 µm filter to obtain crude culture filtrates. For ethyl acetate lipid extraction, crude culture filtrates were acidified with 10 µL 1N HCl followed by an over-night incubation. In brief, ethyl acetate liquid-liquid extractions were done in Corning Falcon (Cat. #1495949A, Thermo Fisher) 50 mL vials using a 1:1 (v/v) ethyl acetate to culture filtrate ratio followed by vortexing for 30 s and incubation for 5 min to accomplish phase separation. The upper organic ethyl acetate phase was carefully removed by not disturbing the interphase or the lower water phase using a serological pipet. Following replenishment of the upper phase with fresh ethyl acetate, the extraction was repeated two more times. The resulting ethyl acetate extracts were combined and evaporated to dryness under nitrogen to obtain lipid extracts and re-diluted in the assay buffers with a stock concentration of 1 mg/mL. The reconstituted crude filtrate stock solutions were to the experiments according to the given final concentrations at 25, 50, 100 or 500 µg/mL. Lipid extracts were either analyzed directly by Liquid Chromatography (LC) Q-TOF mass spectrometry or fractionated by Semi-Preparative High Performance Liquid Chromatography (Semi-Prep HPLC).

2.8. Culture Filtrate Compound Purification by Fractionation using Semi-Prep High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

For Semi-Prep HPLC, culture filtrates or ethyl acetate lipid extracts were taken up at 1 mg/mL concentration in 60% LC-MS grade water and 40% Acetonitrile (Optima Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 0.1% Formic Acid. The column separation was done on a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18, 95Å, 4.6 x 250 mm, 5 µm, 400 bar pressure limit (cat. 959990-902, Agilent, CA) by applying an acetonitrile/water gradient at 1.2 mL/min flow rate, and a temperature of 60 °C. The mobile phase consisted of water, 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile 0.1% formic acid (B). The following gradient conditions were used: from 0 min at 5% B ramped up to 40% B at 15 min ramped up to 90% B at 18 min which was ramped down to 5% B at 23 min and kept at this concentration for 1 min post-run. Fractions were collected either at the corresponding VWD peak for the pyochelin compound at 254 nm (proportional at 2 min retention time) or at the corresponding peak for peptides at 205 nm (proportional 4 min). The resulting fractions were evaporated to dryness under nitrogen to obtain purified extracts and re-diluted in the assay buffers with a stock concentration of 1 mg/mL and analyzed directly by Liquid Chromatography (LC) Q-TOF mass spectrometry.

2.9. Compound Profiling by LC-QTOF Analysis

Samples obtained from culture filtrate fractionation, or ethyl acetate extractions or sample standards (i.e., pyochelin) were loaded at 0.1 µg/µl with a 10 µl total load onto an Agilent 1290 Infinity II HPLC. A ZORBAX RRHD Eclipse Plus C18, 95Å, 2.1 x 50 mm, 1.8 µm, 1200 bar pressure limit (cat. 959757-902, Agilent, CA) was used for separation with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min, and a temperature of 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of water, 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile 0.1% formic acid (B). The following gradient conditions were used: 0.5 min 40% B ramped up to 95% B at 25 min which was kept at this concentration for 5 min post-run. Following HPLC separation samples were analyzed in an Agilent 6546 Q-TOF LC-MS-MS at positive ion electrospray mode, acquisition range 100–1700 amu, scan rate of 3 spectra/s, source 225 °C with a gas flow of 12 L/min, sheath gas temperature of 300 °C and sheath gas flow of 11 L/min. The VCap was set at 3500, the nozzle voltage at 1000 V, fragmentor at 150, skimmer 65 V, and octopole RF peak 750. MS/MS fragmentation was done at 20, 40, and 70 eV. Data acquisition was performed using Agilent MassHunter LC-MS Data Acquisition Software (version 10.0). Data analysis was performed using Agilent Profinder for raw file spectrum alignment followed by Mass Profiler Professional statistical analysis including identification of unique compounds by subtracting compounds present in the M9 minimum medium control followed by compound identification with established PCDL libraries from Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and the METLIN 3.1.5 lipid library. MassHunter Qualitative Analysis Software was used to generate base peak chromatograms and compound mass-specific extracted ion chromatograms including METLIN library alignment of compounds by using the “Find by Formula” function for compound identification.

2.10. Fluorescence Microscopy

The LIVE/DEAD® BacLightTM Bacterial Viability Kit (BacLight; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Waltham, MA) was utilized to differentiate between live and dead cells according to the manufacture’s recommendations. Samples were spotted onto glass slides prior to analysis by fluorescence microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse Fluorescence Microscope with an X-Cite 120Q fluorescence illumination system with a DS Qi2 monochrome microscope camera under 100x objective in oil and green or red fluorescence wave filter.

2.11. Flow Cytometry

Fuel microbial cultures were set-up in 40 mL glass vials containing 5 mL water bottom (1x M9 minimal media) overlaid with 20 mL filter sterilized Jet-A fuel as a carbon source. Fuel cultures were inoculated with Gram-positive bacterium Gordonia sp. at a final concentration of 1 x 105 cells/mL. Cultures were supplemented with the chosen antimicrobials, e.g., crude culture filtrate at doses of 0.0 µl (microbial growth control) and administered at 100 µl (proportional 1.38 mg compound mixture dry weight), 500 µl, 1 mL, and 2.5 mL followed by incubation at 28 ºC with agitation. Samples were taken over a course of 7 days and 1 mL of each sample was collected across different time points. Serial dilutions were made for CFU culture plating to confirm the number of viable culturable cells. A negative control with M9 + 0.5% glycerol with 1 x 105 cells/mL Gordonia sp. without any fuel to confirm only the filtrate was the reason for an antimicrobial effect and not the fuel itself. In addition, the cells were stained with live (0.5 µm SYTO 9; green)/ dead (0.25 µm Propidium iodide; red), and analyzed by flow cytometry (Attune, NxT Invitrogen) including determination of live-, and dead and total cell number as well as adjustment of side scatter and forward scatter to determine appearance of cells and cellular debris. Detection thresholds were set using green and yellow fluorescence, and live and dead cells were gated on dot plots.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis for growth experiments included consideration of number of independent samples (n) that included the average of at least triplicates of colony forming units (CFU) plating. Two-way ANOVA was done for multiple dose comparisons with Dunnet’s post-test using GraphPad Prism 10.0 software (Dotmatics, Boston, MA).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to identify novel naturally produced antimicrobial compounds for control of biocontamination in hydrocarbon fuels. Initial antimicrobial activity testing of 493 microbial fuel isolates from our in-house repository by the commonly used agar plug screening method [

17,

33,

34] resulted in several promising candidates. To exclude fuel isolates with false-positive antimicrobial activity resulting from cell-to cell interactions in the agar plug screening method, further testing included fluorescence and SEM microscopy. In addition, we carefully developed liquid assay for assurance of soluble biocontrol compounds. As a result, two fuel-isolate strains,

P. protegens #133 and

B. subtilis # 232 demonstrated promising biocontrol activity against bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi.

Antimicrobials from

Bacillus species are well-known and have been proposed for use in agricultural applications and clinical settings including the production of biosurfactants [

35,

36,

37,

38]. According to the agar plug screening, the isolate #232 had the biggest inhibition cycles against other Gram-positive bacteria

Gordonia sp. and

B. atrophaeus; Gram-negative bacterium

P. putida and

H. effusa yeasts

Y. lipolytica, M. guilliermondii,

S. pombe, and filamentous fungi

H. resinae, A. versicolor, and

F. oxysporum. Liquid culture assay demonstrated similar #232 culture filtrate biocontrol efficiency for most of the above tested microbes, yet lacked agar plug testing observed efficacy against yeast

Y. lipolytica,

M. guilliermondii, and

S. pombe, and filamentous fungi

A. versicolor, and

F. oxysporum. This can have several reasons, including stability of some of the compounds, and the lack of cell-to-cell interactions. For instance, some of the

Bacillus may regulate the activation of cellular envelope-localized stress sensing receptors were demonstrated to be essential for initiation of production of different antimicrobials [

39]. In addition,

Bacillus is known to produce volatile organic compounds with antifungal properties [

23,

26,

27] that can be retained in the agar test plate but might evaporate during liquid testing.

According to the mass spectrometry analysis of

B. subtilis #232 lipid extracts, one of the detected antifungal compounds, i.e., the hyphae and spore lysing antifungal lipopeptide fengycin C [

40,

41] was abundantly present, yet chemical instability of fengycins has been previously observed by other investigators [

42]. Also, mass spectrometry detected the lipopeptide biosurfactant surfactin that is known to cause osmotic pressure imbalance in fungi and bacteria [

43,

44]. When looking at potential active compounds that might be relevant for the observed inhibition of fungi and bacteria, gageostatin C was detected at high abundance [

45] together with zoospore motility inhibitor gageopeptin B [

21]. Mass spectrometry also detected a number of abundant compounds of the macrolactin family including 7-O-Malonyl macrolactin, macrolactin F, and macrolactin B that have been demonstrated to exhibit antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

46,

47]. Unfortunately, our efforts of targeted compound purification from #232 culture filtrate yielded variable results although growth conditions and purification protocols were meticulously performed. The variable metabolic compound production of

Bacillus has been observed by other investigators [

48,

49], and was previously discussed as a result of “bacterial cannibalism” or cross- feeding where a differentiated subpopulation harvests nutrients from their genetically identical siblings through intra- and interspecies metabolic exchange.

When focusing on the #133

P. protegens strain, it seemed to have much higher antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in agar plug testing with radius of inhibition zones starting above 20 mm for most of the tested bacteria. While #133 also demonstrated efficacy against all the tested fungi with radius of inhibition zones smaller than 20 mm. Compared to assays using the #232 isolate, liquid culture assays of #133 lacked antimicrobial activity against yeast

Y. lipolytica,

M. guilliermondii, and

S. pombe and filamentous fungi

A. versicolor, and

F. oxysporum. Similar to

Bacillus species,

Pseudomonas species produce volatile organic compounds (VOG) [

50], and phenolic compounds [

51] with antimicrobial activity that might be inactive in liquid culture assays. In contrast to

Bacillus, most of the antimicrobial compounds produced by

P. protegens include small molecules and lipid compounds such as rhamnolipids and quorum sensing molecules including pyoverdine, pyocyanin, and phenzine [

52]. Analysis of lipid extracts from #133 culture filtrate by mass spectrometry detected common molecules contained in the biofilm of other

Pseudomonads such as quorum-sensors 3-oxo-C12-HSL (N-3-Oxo-Dodecanoyl-L-Homoserine Lactone), NQNO (Nonyl-4-Hydroxyquiniline-N-oxide) and rhamnolipids Rha-C10:1-C8, Rha-C10-C10-CH3, Rha-Rha-C12-C10, Rha-C12:1-C10 and Rha Rha-Rha-C14-C14. In addition, the siderophore pyochelin [

28] was identified as one of the most abundant compounds in #133 lipid extracts.

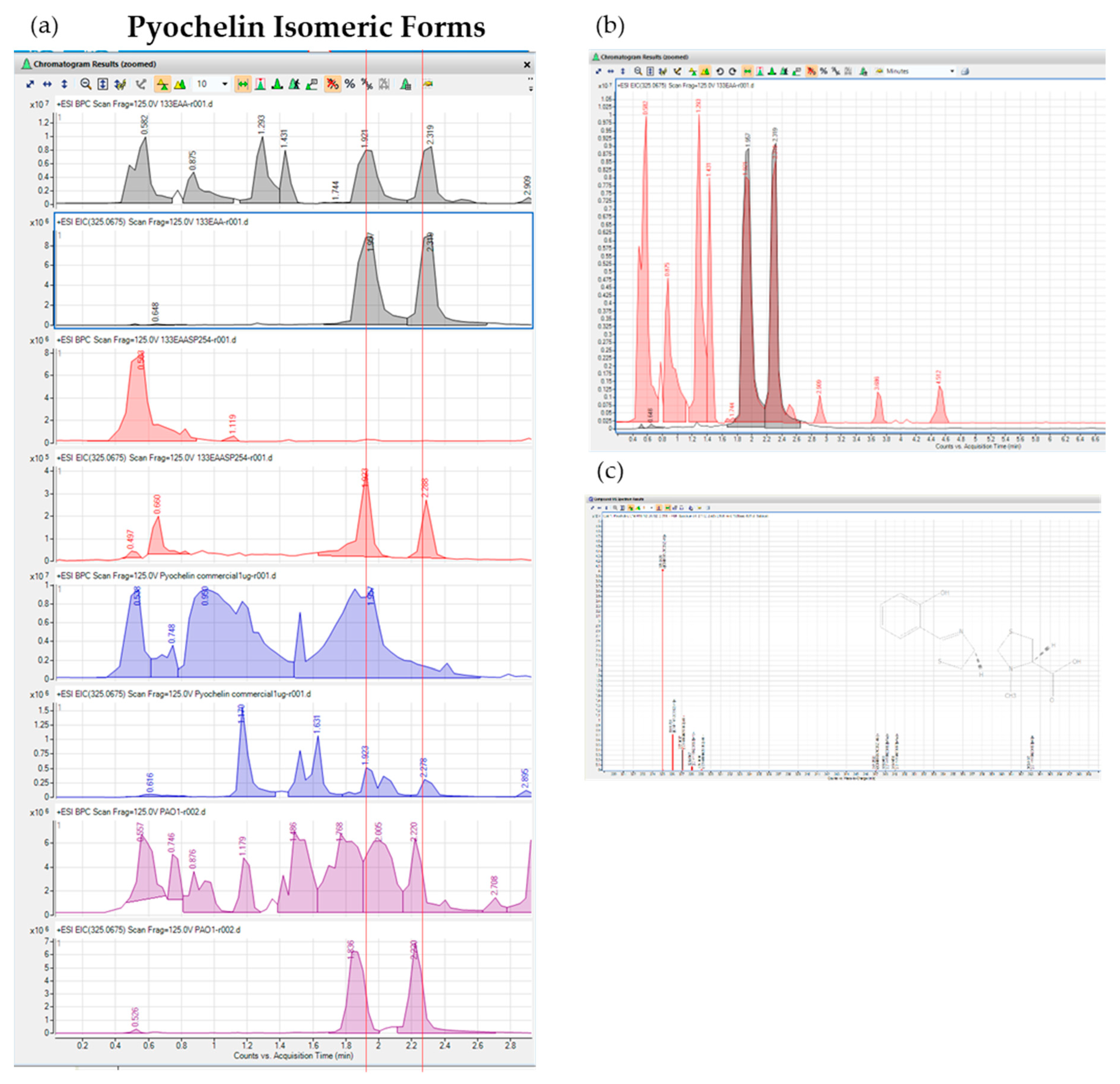

The compound trace for #133 extracted pyochelin differed from that of

P. aeruginosa PAO1 by displaying two unique peaks at retention times 1.89 and 2.3 min with practically no surrounding contaminating compounds while

P. aeruginosa had much lower pyochelin compound abundance with several other surrounding compound ions present. While the pyochelin iron chelating and associated antimicrobial action through metal ion depletion has been well-characterized [

28,

32], pyochelin was also suggested to cause cell death by bacterial membrane disruption [

53]. When testing the antimicrobial actions of #133 purified pyochelin, the tested dose had some partial fungistatic effects on the tested microbes

Y. lipolytica, and

H. resinae but lacked antimicrobial efficiency against

Gordonia sp. In contrast, the purchased synthetic pyochelin standard lacked inhibition of

Y. lipolytica but showed a similar fungistatic effect against

H. resinae with a significant bactericidal effect on

Gordonia sp. Potential issues with #133 pyochelin compound purity versus additional contaminants within the synthesized pyochelin product at a marketed 96% purity might affect the dose determinations explaining potential differences in compound activity.

For our Jet A fuel microbial inhibition assay, we developed a microbial consortia of major fuel contaminants, including,

Gordonia sp.,

P. putida,

Y. lipolytica,

and H. resinae that are often found in a fuel tank environment. In contrast to liquid culture assays, Jet A fuel culture testing of same-dose commercial pyochelin standard (20 µg/mL) lacked effective inhibition of bacterial growth. The observed effect was similar to the lowest #133 culture filtrate dose of 100 µL; a dose that was only bacteriostatic. When the dose of #133 was increased to 1 mL, bacterial growth stalled for 10 days while it was completely eliminated at 2.5 mL. In contrast, fungal growth seemed to rise in the presence of bacterial inhibition. This observation suggests that the presence of bacteria in the consortium inherently exerts a growth inhibitory effect over the fungi, and when this effect is eliminated, fungal growth is enhanced. The equilibrium between growth-inhibitory and stimulatory effects of bacterial and fungal consortia is a phenomenon commonly observed in various co-culture scenarios [

54,

55].

While the Jet A fuel consortium culture was set up to test #133 culture filtrate efficiently against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, our observations conclude that #133 culture filtrate is highly efficient of killing

Gordonia sp.. Several species of

Gordonia have been identified in hydrocarbon fuels with ability to survive and proliferate in the toxic fuel environment by forming micelles [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Accordingly, the identified rhamnolipid compounds Rha-C10:1-C8, Rha-C10-C10-CH3, Rha-Rha-C12-C10, Rha-C12:1-C10 and Rha Rha-Rha-C14-C14 that are known surfactants might interfere with potential antimicrobial activity of other compounds contained in #133 culture filtrate in fuel by assisting micelle formation [

5,

60,

61]. Yet, small molecules such as pyochelin and other compounds contained in #133 culture filtrate might act on destabilizing the cell membrane of these Gram-positive bacteria [

62], and the mass spectrometry detected quorum-sensing molecules 3-oxo-C12-HSL [

63], and NQNO might further assist in inhibiting bacterial growth [

64]. It remains to be determined which compound in #133 culture filtrate is responsible for the observed antimicrobial action against Gram-positive bacteria.

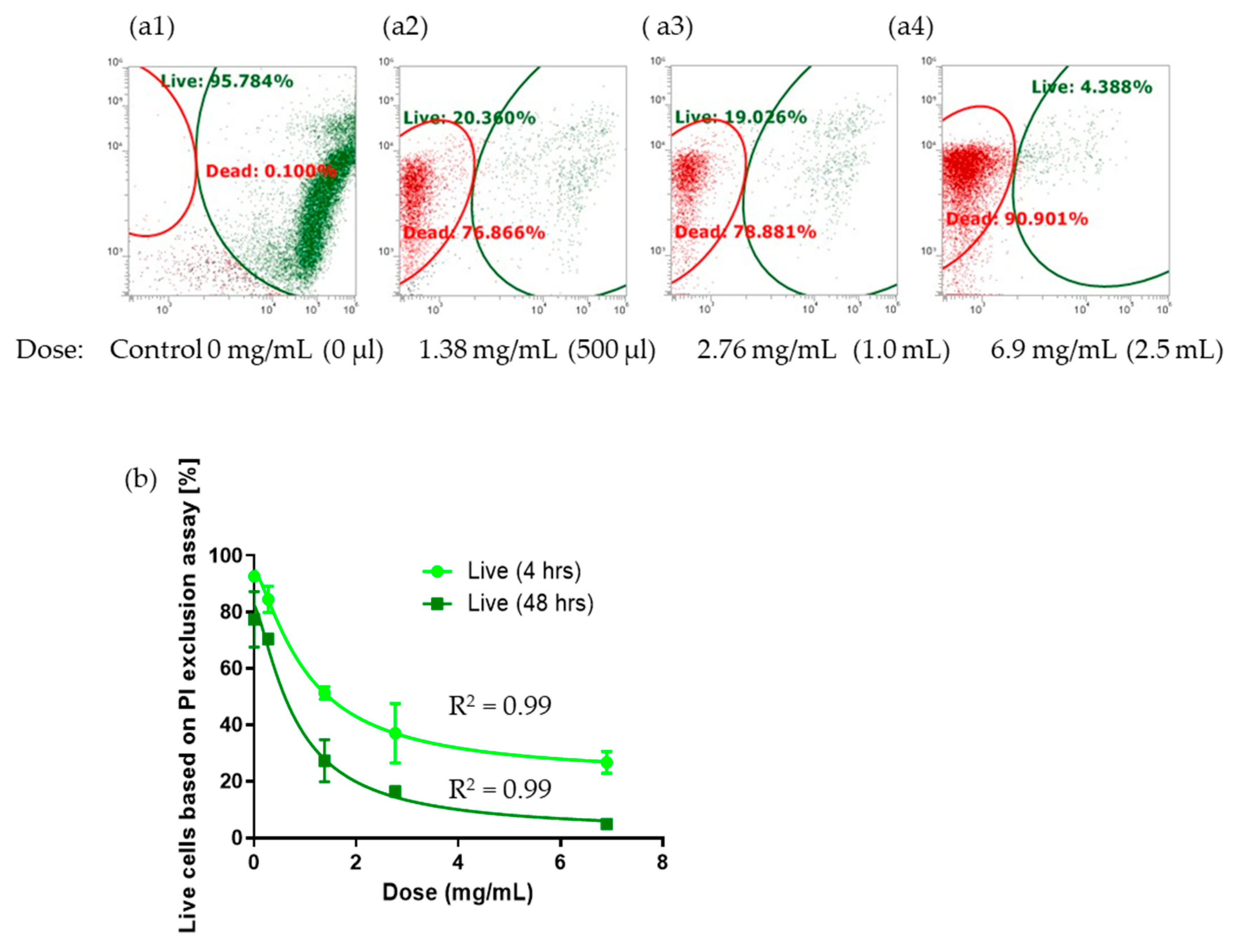

To determine the antimicrobial mechanism of action of #133 culture filtrate on Gram-positive bacteria, pure culture of

Gordonia sp. in Jet A fuel culture was further analyzed by flow-cytometry (FCM) in combination with CFU culture plating to assess viable, dead, viable none culturable cells (VBNC), and lysed bacterial cells. A major disadvantage of using plate count method for antimicrobial screening is its difficulty to identify whether bacteria are killed (bactericidal) or prevented from replicating (bacteriostatic). FCM in conjunction with functional fluorescent staining allows real-time assessment of cell viability by simultaneous counting live and dead cells. Through adjustment of light scattering parameters, an assessment can be made about the quantity of cellular debris from lysed cell bodies. The corresponding results from live/dead cell analysis confirmed that antimicrobial compounds contained in #133 culture filtrate exhibit a bactericidal effect against

Gordonia sp. killing the cells through bacterial lysis and membrane damage. The biocontrol activity of #133 culture filtrate seems to be unique in its capability to lyse the thick peptidoglycan containing bacterial cell wall [

65] of

Gordonia sp., and even shows efficacy even in the presence of a hydrocarbon.

Investigating the antimicrobial mode of action is crucial because it provides deeper understanding of how the antimicrobials work against the targeted microorganisms and how they could be optimized to improve the antimicrobial activity for the development of suitable commercial biocides. Real-time monitoring of individual cell counts by FCM allows assessment of live and dead cells simultaneously [

29,

30,

31]. Therefore, we established a rapid and simple assay to screen the crude extract of

P. protegens #133 on fuel bio contaminants using flow cytometry. Using the live SYTO 9/dead PI cellular exclusion assay provides a straight-forward methods to identify cell membrane integrity and cell death [

31,

66,

67]. In this study, FCM analysis demonstrated the time-dependent mode of antimicrobial action of #133 culture filtrate on

Gordonia sp. cell viability when monitored at 4 hours and 48 hours after antimicrobial exposure. According to the decrease in IC50 from 1.031 mg/mL at 4 hours versus an IC50 of 0.8019 mg/mL after 48 hours, exposure time played an important role in the percent viability dose response assessment of

Gordonia sp. While the effective dose of #133 culture filtrate is relatively high with an IC50 of 0.8 mg/mL, it needs to be considered that the culture filtrate is composed of a multitude of compounds that when purified might result in much lower IC50 for individual compounds. By modulating changes in detection in the according settings for forward/side scatter plots we were able to detect evidence of cell lysis as the antimicrobial mode of action and further confirmed by fluorescence microscopy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Osman Radwan, Oscar Ruiz, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Data curation, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Adam Reed, Osman Radwan, Loryn Bowen, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Formal analysis, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Adam Reed, Osman Radwan, Loryn Bowen, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Funding acquisition, Oscar Ruiz and Thusitha Gunasekera; Investigation, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Adam Reed, Loryn Bowen, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Methodology, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Adam Reed, Osman Radwan, Loryn Bowen, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Project administration, Oscar Ruiz, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Supervision, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Validation, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Adam Reed, Loryn Bowen, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Visualization, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Osman Radwan and Thusitha Gunasekera; Writing – original draft, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann; Writing – review & editing, Amanda Barry Schroeder, Adam Reed, Oscar Ruiz, Thusitha Gunasekera and Andrea Hoffmann.

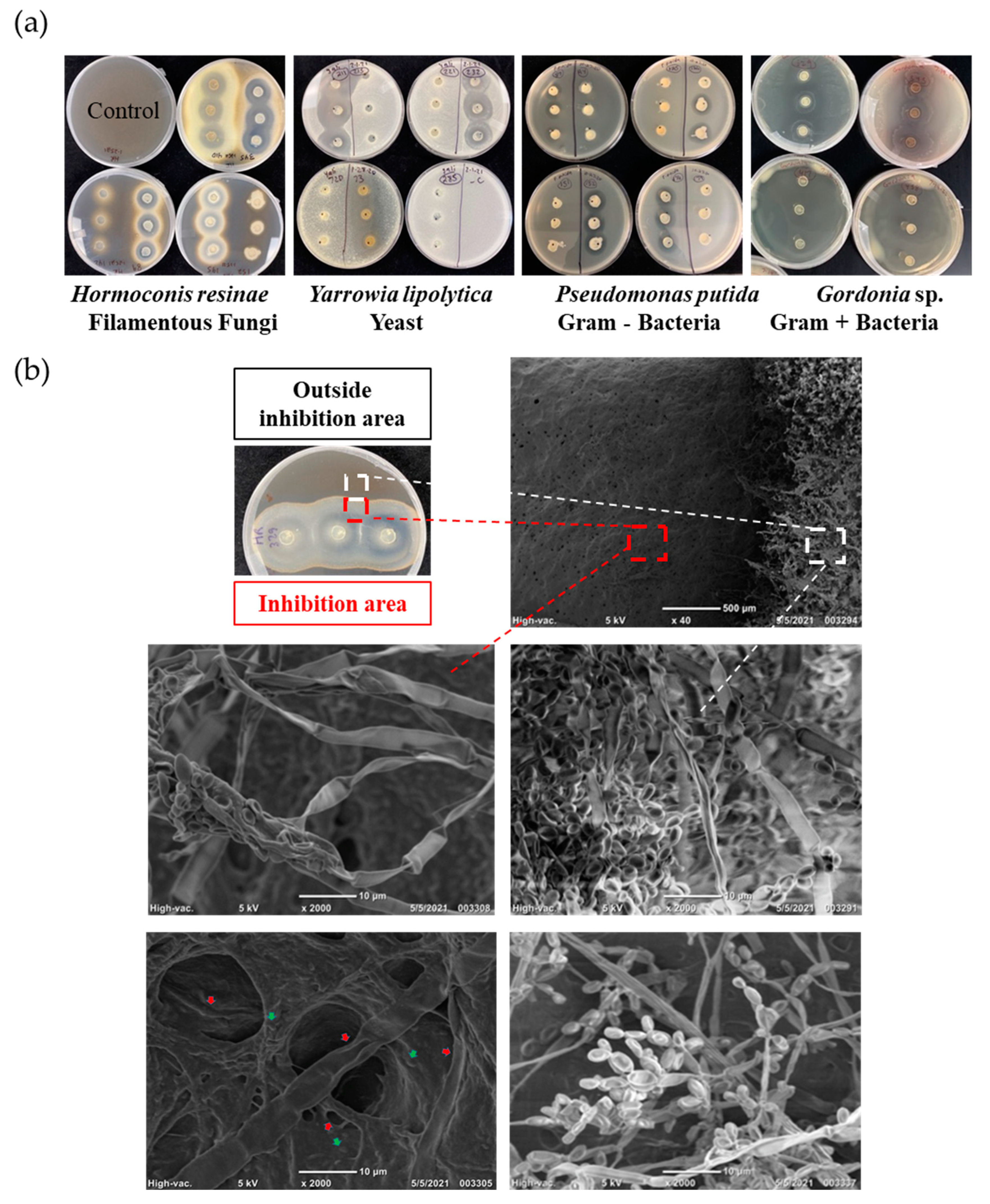

Figure 1.

Agar Plug Screening of Biocontrol Producing Microbes. (a) Agar plug screening of fuel isolate repository with selected target microbes P. putida, Gordonia sp., Y. lipolytica, and H. resinae. (b) Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images show Hormoconis resinae fungal mycelium and spores. Images show shrinking fungal mycelium and spores from the inhibited fungal growth area (red dashed square) compared to intact fungal mycelium and spores from outside inhibition area (white dashed square). Red arrows point to ultrastructure damages in both fungal mycelium and spores while green arrows point to biocontrol Delftia sp. #329 bacteria.

Figure 1.

Agar Plug Screening of Biocontrol Producing Microbes. (a) Agar plug screening of fuel isolate repository with selected target microbes P. putida, Gordonia sp., Y. lipolytica, and H. resinae. (b) Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images show Hormoconis resinae fungal mycelium and spores. Images show shrinking fungal mycelium and spores from the inhibited fungal growth area (red dashed square) compared to intact fungal mycelium and spores from outside inhibition area (white dashed square). Red arrows point to ultrastructure damages in both fungal mycelium and spores while green arrows point to biocontrol Delftia sp. #329 bacteria.

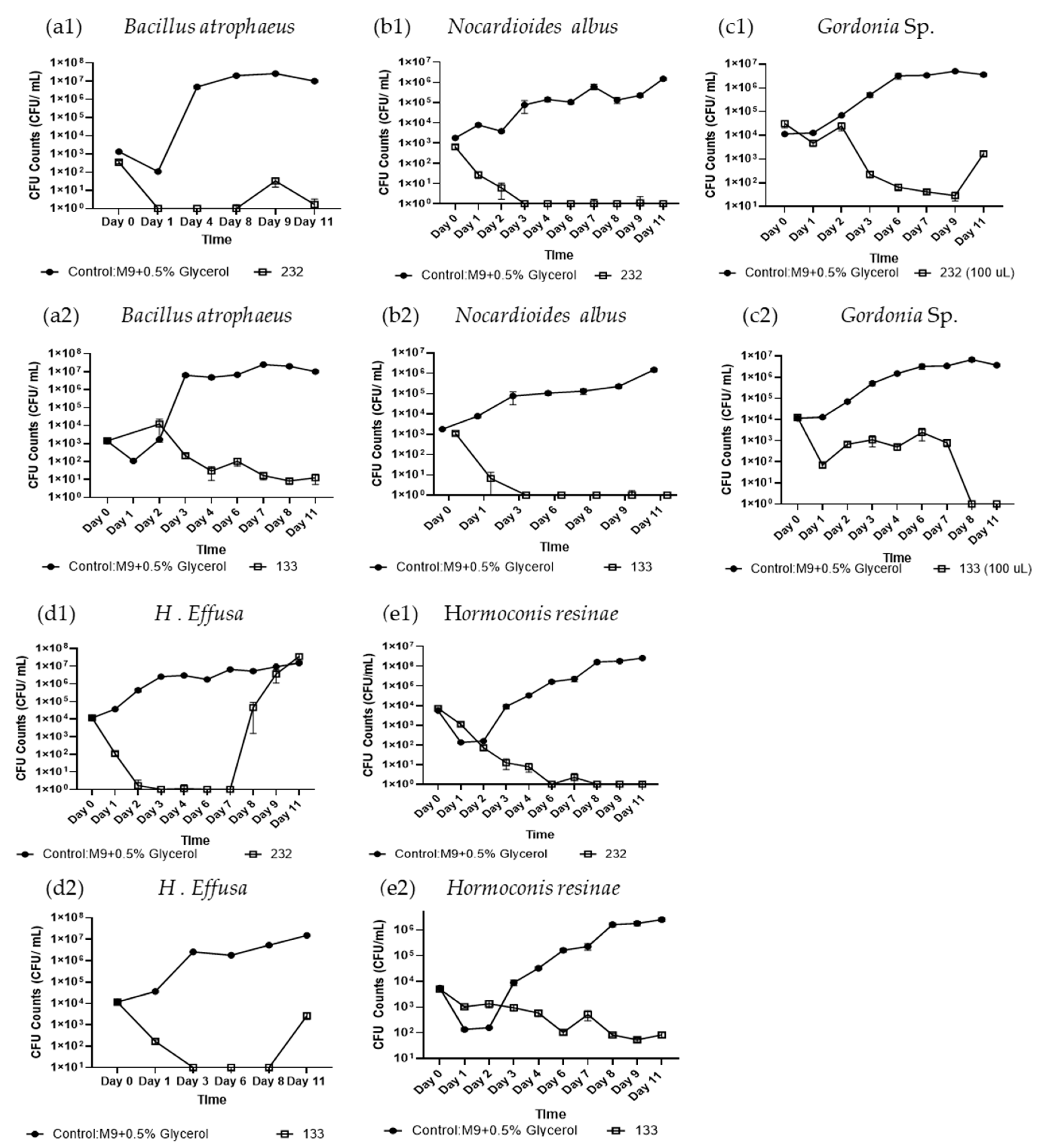

Figure 2.

Biocontrol Activity Screening of Isolate B. subtilis #232 and P. protegens #133 Crude Culture Filtrate in Liquid Culture. Biocontrol activity of crude culture filtrates from isolate B. subtilis #232 (1) and P. protegens #133 (2) was tested against (a) B. atrophaeus, (b) N. albus, (c) Gordonia sp., (d) H. effusa, and (e) H. resinae over 11 days using CFU evaluation. Control shown in circles, and test samples in square. Two-sample student’s t-test was applied by taking the averages of each condition and combining all the control data across experiments. Error bars represent standard error, sample size n = 6 and above.

Figure 2.

Biocontrol Activity Screening of Isolate B. subtilis #232 and P. protegens #133 Crude Culture Filtrate in Liquid Culture. Biocontrol activity of crude culture filtrates from isolate B. subtilis #232 (1) and P. protegens #133 (2) was tested against (a) B. atrophaeus, (b) N. albus, (c) Gordonia sp., (d) H. effusa, and (e) H. resinae over 11 days using CFU evaluation. Control shown in circles, and test samples in square. Two-sample student’s t-test was applied by taking the averages of each condition and combining all the control data across experiments. Error bars represent standard error, sample size n = 6 and above.

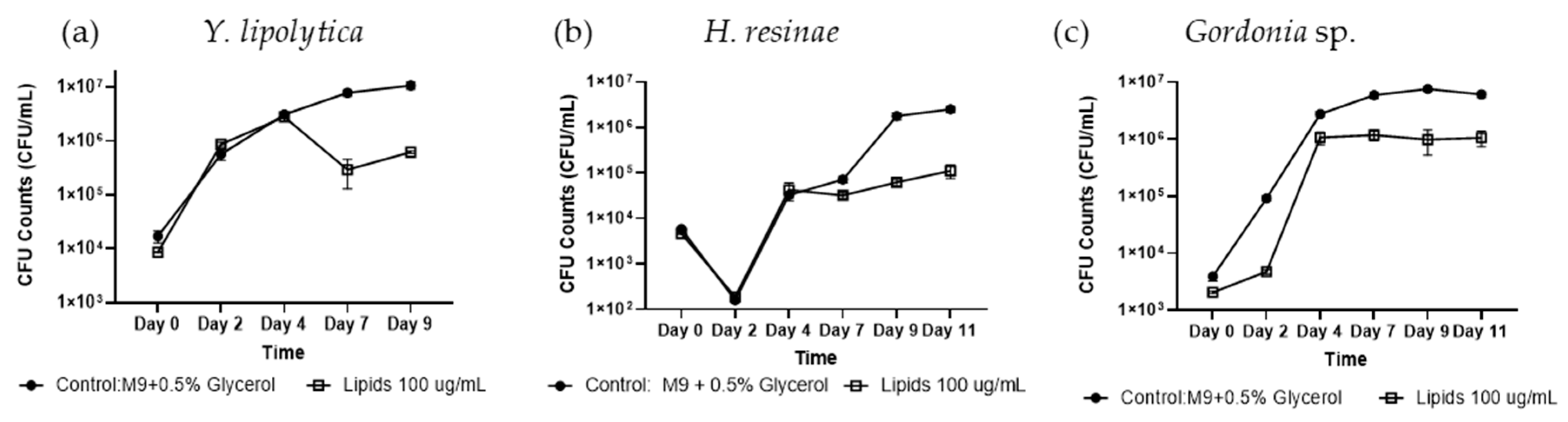

Figure 3.

Biocontrol Activity Screening of Isolate B. subtilis #232 Lipid Extracts in Liquid Culture. Biocontrol activity of Isolate #232 lipid extracts at a concentration of 100 µg/mL was tested on (a) Y. lipolytica, (b) H. resinae, and (c) Gordonia sp. for 11 days using CFU evaluation. Two-sample student’s t-test was applied by taking the averages of each condition and combining all the control data across experiments. Error bars represent standard error, sample size n = 3.

Figure 3.

Biocontrol Activity Screening of Isolate B. subtilis #232 Lipid Extracts in Liquid Culture. Biocontrol activity of Isolate #232 lipid extracts at a concentration of 100 µg/mL was tested on (a) Y. lipolytica, (b) H. resinae, and (c) Gordonia sp. for 11 days using CFU evaluation. Two-sample student’s t-test was applied by taking the averages of each condition and combining all the control data across experiments. Error bars represent standard error, sample size n = 3.

Figure 4.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Isolate #133 Culture Filtrate Contained Compounds Purified by Ethyl-Acetate Liquid Extraction and Semi-preparative HPLC Fractionation. (a) LC-QTOF Mass spectrometry analysis of #133 culture filtrate ethyl acetate lipid extracts (133 EAA, grey trace) and targeted pyochelin compound fractionation at 254 nm by semi-preparative HPLC (13 3EAA SP 254, red trace). For comparison, commercial pyochelin standard was analyzed by LC-QTOF (blue trace) together with ethyl acetate lipid extracts from culture filtrate of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (PAO1, purple trace) with known production of pyochelin. Base Peak Chromatograms (BPC) and extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) for pyochelin compound at a mass of 325.0625 Da are shown with isomeric form of pyochelin indicated by red lines at retention times of approximately 1.89 and 2.3 min. (b) BPC for isolate #133 EAA lipid extraction (red trace) overlaid with two extracted ion chromatogram isomeric peaks for pyochelin (grey trace). (c) Ion spectrum with predicted adducts and compound formulas EAA purified pyochelin.

Figure 4.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Isolate #133 Culture Filtrate Contained Compounds Purified by Ethyl-Acetate Liquid Extraction and Semi-preparative HPLC Fractionation. (a) LC-QTOF Mass spectrometry analysis of #133 culture filtrate ethyl acetate lipid extracts (133 EAA, grey trace) and targeted pyochelin compound fractionation at 254 nm by semi-preparative HPLC (13 3EAA SP 254, red trace). For comparison, commercial pyochelin standard was analyzed by LC-QTOF (blue trace) together with ethyl acetate lipid extracts from culture filtrate of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (PAO1, purple trace) with known production of pyochelin. Base Peak Chromatograms (BPC) and extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) for pyochelin compound at a mass of 325.0625 Da are shown with isomeric form of pyochelin indicated by red lines at retention times of approximately 1.89 and 2.3 min. (b) BPC for isolate #133 EAA lipid extraction (red trace) overlaid with two extracted ion chromatogram isomeric peaks for pyochelin (grey trace). (c) Ion spectrum with predicted adducts and compound formulas EAA purified pyochelin.

Figure 5.

Biocontrol Activity Screening of P. protegens #133 Pyochelin Extract in Liquid Culture. Biocontrol activity of Isolate #133 pyochelin extracts (1), and commercial pyochelin standard (2) at a concentration of 25 and 50 µg/mL was tested on (a) Y. lipolytica, (b) H. resinae, and (c) Gordonia sp. over 11 days using CFU evaluation. Two-sample student’s t-test was applied by taking the averages of each condition and combining all the control data across experiments. Error bars represent standard error, sample size n = 3.

Figure 5.

Biocontrol Activity Screening of P. protegens #133 Pyochelin Extract in Liquid Culture. Biocontrol activity of Isolate #133 pyochelin extracts (1), and commercial pyochelin standard (2) at a concentration of 25 and 50 µg/mL was tested on (a) Y. lipolytica, (b) H. resinae, and (c) Gordonia sp. over 11 days using CFU evaluation. Two-sample student’s t-test was applied by taking the averages of each condition and combining all the control data across experiments. Error bars represent standard error, sample size n = 3.

Figure 6.

Microbial Consortium Growth inhibition Dynamics after Treatment with Isolate P. protegens #133 Crude Culture Filtrate in Fuel Culture. Biocontrol activity of #133 crude culture filtrate (#133 crude) and pyochelin administered at different doses to fuel consortium cultures containing P. putida, Gordonia sp. Y. lipolytica and H resinae. Graphs display CFU/mL determined for (a) total bacteria (P. putida and Gordonia sp.); (b) total fungi (Y. lipolytica and H resinae); (c) total microbial load (bacteria plus fungi), across different time points (day 0 to day 29). Testing included triplicate CFU plating of each sample pictured. (d) Consortium growth over the course of 29 days. Control (inoculated microbial consortium without antimicrobial treatment), pyochelin (20 µg/mL), and isolate #133 crude culture filtrate supplemented at different doses of 100 µl, 1 mL and 2.5 mL. Red line indicates interphase between fuel phase and water bottom.

Figure 6.

Microbial Consortium Growth inhibition Dynamics after Treatment with Isolate P. protegens #133 Crude Culture Filtrate in Fuel Culture. Biocontrol activity of #133 crude culture filtrate (#133 crude) and pyochelin administered at different doses to fuel consortium cultures containing P. putida, Gordonia sp. Y. lipolytica and H resinae. Graphs display CFU/mL determined for (a) total bacteria (P. putida and Gordonia sp.); (b) total fungi (Y. lipolytica and H resinae); (c) total microbial load (bacteria plus fungi), across different time points (day 0 to day 29). Testing included triplicate CFU plating of each sample pictured. (d) Consortium growth over the course of 29 days. Control (inoculated microbial consortium without antimicrobial treatment), pyochelin (20 µg/mL), and isolate #133 crude culture filtrate supplemented at different doses of 100 µl, 1 mL and 2.5 mL. Red line indicates interphase between fuel phase and water bottom.

Figure 7.

Antimicrobial Cytotoxicity Effect of P. protegens #133 Culture Filtrate Against Gordonia sp. in Jet A Fuel Culture using Live/Dead Flow Cytometry. Gordonia sp. growth in the presence of different doses of biocontrol #133 culture filtrate in Jet A fuel cultures determined by Live/Dead Flow Cytometry over 7 days. Control (M9 minimal medium) and isolate #133 crude culture filtrate were tested at different doses of 100 µL (1.38 mg dry weight), 500 µL, 1000 µL, and 2500 µL. (a) Example of FCM live (SYTO 9, green)/dead (PI, red) cellular detection 48 hours after exposure to #133 culture filtrate at different calculated doses considering a total volume of 5 mL aqueous bottom: (a1) Control, 0 mg/mL (0 µL), (a2) 1.38 mg/mL (500 µL), (a3) 2.76 mg/mL (100 µL), and (a4) 6.9 mg/mL (2500 µL). Green= live; Red= dead. (b) Cell viability dose-response curve after 4 hours and 48 hours of exposure to different doses of #133 culture filtrate with calculated concentrations given in (mg/mL). Error bars represent standard error, sample size n = 3.

Figure 7.

Antimicrobial Cytotoxicity Effect of P. protegens #133 Culture Filtrate Against Gordonia sp. in Jet A Fuel Culture using Live/Dead Flow Cytometry. Gordonia sp. growth in the presence of different doses of biocontrol #133 culture filtrate in Jet A fuel cultures determined by Live/Dead Flow Cytometry over 7 days. Control (M9 minimal medium) and isolate #133 crude culture filtrate were tested at different doses of 100 µL (1.38 mg dry weight), 500 µL, 1000 µL, and 2500 µL. (a) Example of FCM live (SYTO 9, green)/dead (PI, red) cellular detection 48 hours after exposure to #133 culture filtrate at different calculated doses considering a total volume of 5 mL aqueous bottom: (a1) Control, 0 mg/mL (0 µL), (a2) 1.38 mg/mL (500 µL), (a3) 2.76 mg/mL (100 µL), and (a4) 6.9 mg/mL (2500 µL). Green= live; Red= dead. (b) Cell viability dose-response curve after 4 hours and 48 hours of exposure to different doses of #133 culture filtrate with calculated concentrations given in (mg/mL). Error bars represent standard error, sample size n = 3.

Table 1.

Agar Plug Screening of Selected High Efficiency Biocontrol Microbes Pseudomonas protegens #133 and Bacillus subtilis #232 against 16 target strains. Radius of inhibition zones in [mm]. Darker green color in gradient indicates largest inhibition zones observed in the presence of biocontrol isolates #133 or #232. Gram-negative bacteria included P. putida, A. venetianus, H. effusa, and Jm109 E. coli. Gram-positive bacteria included Gordonia sp., R. equi N. albus, and B. atrophaeus. Yeast included Y. lipolytica, M. guilliermondii and C. ethanolica. Filamentous fungi included H. resinae, A. versicolor and F. oxysporum. ± stands for standard deviation of listed sample size n. Days are listed where diffusion assay had the largest inhibition zone which was different due to high variability in growth behavior of tested bacteria, yeast, and fungal strains.

Table 1.

Agar Plug Screening of Selected High Efficiency Biocontrol Microbes Pseudomonas protegens #133 and Bacillus subtilis #232 against 16 target strains. Radius of inhibition zones in [mm]. Darker green color in gradient indicates largest inhibition zones observed in the presence of biocontrol isolates #133 or #232. Gram-negative bacteria included P. putida, A. venetianus, H. effusa, and Jm109 E. coli. Gram-positive bacteria included Gordonia sp., R. equi N. albus, and B. atrophaeus. Yeast included Y. lipolytica, M. guilliermondii and C. ethanolica. Filamentous fungi included H. resinae, A. versicolor and F. oxysporum. ± stands for standard deviation of listed sample size n. Days are listed where diffusion assay had the largest inhibition zone which was different due to high variability in growth behavior of tested bacteria, yeast, and fungal strains.

| |

|

Pseudomonas protegens #133 (Gram- Negative) |

Bacillus subtilis #232

(Gram- Positive) |

| Target Microbes |

Classification |

Inhibition Zone Radius [mm] |

Time [days] |

n = |

Inhibition Zone Radius [mm] |

Time [days] |

n = |

| Pseudomonas putida |

Gram-Negative |

30.17 ± 5.11 |

6 |

6 |

7.75 ± 14.31 |

7 |

12 |

| Acinetobacter venetianus |

Gram-Negative |

20.61 ± 14.48 |

7 |

18 |

3.17 ± 3.99 |

1 |

18 |

| Hydrocarboniphaga effusa |

Gram-Negative |

32.50 ± 4.51 |

7 |

6 |

3.83 ± 1.72 |

4 |

6 |

| Jm109 Escherichia coli

|

Gram-Negative |

23.67 ± 2.31 |

3 |

3 |

0.00 ± 0 |

5 |

3 |

|

Gordonia sp. |

Gram-Positive |

30.33 ± 3.88 |

6 |

6 |

7.50 ± 11.8 |

6 |

12 |

| Rhodococcus equi |

Gram-Positive |

28.00 ± 2.00 |

3 |

3 |

2.67 ± 0.58 |

7 |

3 |

| Nocardioides albus |

Gram-Positive |

32.00 ± 6.48 |

6 |

9 |

4.22 ± 3.46 |

6 |

9 |

| Bacillus atrophaeus |

Gram-Positive |

16.83 ± 6.70 |

2 |

6 |

4.17 ± 2.79 |

1 |

6 |

| Yarrowia lipolytica |

Yeast |

9.17 ± 5.92 |

4 |

12 |

20.50 ± 8.62 |

5 |

6 |

| Meyerozyma guilliermondii |

Yeast |

17.33 ± 1.53 |

5 |

3 |

5.17 ± 1.80 |

3 |

12 |

| Candida ethanolica |

Yeast |

3.61 ± 3.5 |

1 |

18 |

11.67 ± 5.16 |

3 |

18 |

| Hormoconis resinae |

Fungus |

13.17 ± 5.14 |

4 |

24 |

26.33 ± 3.05 |

6 |

3 |

| Aspergillus Versicolor |

Fungus |

10.89 ± 3.23 |

3 |

18 |

20.33 ± 9.23 |

2 |

21 |

| Fusarium oxysporum |

Fungus |

11.56 ± 4.85 |

2 |

18 |

19.71 ± 4.29 |

2 |

21 |

Table 2.

Summary Table of Biocontrol Activity. Antimicrobial Activity of Crude Culture Filtrates #133 and #232, purified HPLC fractions #133 EAA SP F2 (#133 ethyl-acetate extractions then Semi-prep Fraction 2) and #232 SP F1 (#232 Semi-prep Fraction 1) and commercial pyochelin. Calculated concentrations from total volume of culture are given in mg/mL or µg/mL. Log-fold change on day 11, bold• represents day 9, and underlined represents day 7 as not all testing ended on day 11. Representative P values are displayed as* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.0001.

Table 2.

Summary Table of Biocontrol Activity. Antimicrobial Activity of Crude Culture Filtrates #133 and #232, purified HPLC fractions #133 EAA SP F2 (#133 ethyl-acetate extractions then Semi-prep Fraction 2) and #232 SP F1 (#232 Semi-prep Fraction 1) and commercial pyochelin. Calculated concentrations from total volume of culture are given in mg/mL or µg/mL. Log-fold change on day 11, bold• represents day 9, and underlined represents day 7 as not all testing ended on day 11. Representative P values are displayed as* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.0001.

| Classification |

Microbe |

Growth Effect |

Log Fold Change on Day 11

(Efficient grown inhibition in blue)

(Bold is Day 9 & Underline is Day 7) |

133 Crude

(6.9 mg/mL)

|

232 Crude

(9.8 mg/mL)

|

133 Crude

(6.9 mg/mL)

|

232 Crude

(9.8 mg/mL)

|

Commercial Pyochelin

(50 µg/mL)

|

133 EAA SP F1

(100 µg/mL)

|

232 SP F2

(100 µg/mL)

|

| Gram-Positive |

Gordonia sp. |

Kills |

Kills |

-6.57** |

-3.34* |

-6.57** |

0.07• |

-0.05 |

| Gram-Positive |

Rhodococcus equi |

Reduces |

No Effect |

-2.09 |

0.95 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Gram-Positive |

Nocardioides albus |

Kills |

Kills |

-6.17** |

-6.17*** |

not tested |

not tested |

0.33• |

| Gram-Positive |

Bacillus Atrophaeus |

Kills |

Kills |

-5.91*** |

-6.78** |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Gram-Negative |

Pseudomonas putida |

Enhances |

No Effect |

0.39 |

-0.25 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Gram-Negative |

Acinetobacter venetianus |

No Effect |

Reduces |

0.13 |

-1.02 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Gram-Negative |

Hydrocarboniphaga effusa |

Kills |

No Effect |

-3.75*** |

0.36 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Gram-Negative |

Jm109 Escherichia coli

|

No Effect |

Reduces |

-0.54 |

-3.16** |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Fungus |

Hormoconis resinae |

Kills |

Kills |

-4.48** |

-6.58** |

-1.5 |

-0.77 |

-0.84 |

| Fungus |

Aspergillus versicolor |

No Effect |

No Effect |

-1.93• |

-1.52 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Fungus |

Fusarium oxysporum |

No Effect |

No Effect |

-0.42 |

-0.05 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Yeast |

Meyerozyma guilliermondii |

No Effect |

No Effect |

0.14 |

0.03 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Yeast |

Candida ethanolica |

No Effect |

Enhances |

-0.32• |

2.48 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

| Yeast |

Yarrowia lipolytica |

No Effect |

Reduces |

-0.47 |

-0.9 |

-1.09 |

-0.48 |

-0.35 |

| Yeast |

Candida albicans |

No Effect |

No Effect |

-0.85 |

1.2 |

not tested |

not tested |

not tested |

Table 3.

Day 7 Antimicrobial Cytotoxicity Effect of P. protegens #133 Culture Filtrate Against Gordonia sp. in Jet A Fuel Culture using Live/Dead Flow Cytometry. Gordonia sp. growth in the presence of different doses of biocontrol #133 culture filtrate in Jet A fuel cultures determined by Live (SYTO 9)/Dead (propidium iodide (PI)) Flow Cytometry over 7 days. Control (M9 minimal medium) and isolate #133 crude culture filtrate were tested different doses of 500 µL, 1000 µL and 2500 µL with calculated doses of culture filtrate given in mg/mL considering a total volume of 5 mL water bottom. Table displays CFU plate counts, percent dead cells as determined by PI staining versus lysed cells (side scatter determination) and percent viable but non-culturable (VBNC, SYTO 9 stained compared to CFU plated cells). Percentages were calculated based on day 0 inoculum. Error is given as standard error, sample size n = 3.

Table 3.

Day 7 Antimicrobial Cytotoxicity Effect of P. protegens #133 Culture Filtrate Against Gordonia sp. in Jet A Fuel Culture using Live/Dead Flow Cytometry. Gordonia sp. growth in the presence of different doses of biocontrol #133 culture filtrate in Jet A fuel cultures determined by Live (SYTO 9)/Dead (propidium iodide (PI)) Flow Cytometry over 7 days. Control (M9 minimal medium) and isolate #133 crude culture filtrate were tested different doses of 500 µL, 1000 µL and 2500 µL with calculated doses of culture filtrate given in mg/mL considering a total volume of 5 mL water bottom. Table displays CFU plate counts, percent dead cells as determined by PI staining versus lysed cells (side scatter determination) and percent viable but non-culturable (VBNC, SYTO 9 stained compared to CFU plated cells). Percentages were calculated based on day 0 inoculum. Error is given as standard error, sample size n = 3.

Dose

#133 Culture Filtrate |

% CFUs |

% Dead

(PI-stained cells) |

% Dead

(Lysed cells) |

% VBNC

(STYO9-stained cells) |

Total

Percent |

500 µl

(1.38 mg/mL) |

0 |

0.99 ± 0.27 |

94.90 ± 1.24 |

4.11 ± 0.97 |

100.00 |

1000 µl

(2.76 mg/mL) |

0 |

1.12 ± 0.18 |

96.15 ± 1.14 |

2.73 ± 0.98 |

100.00 |

2500 µl

(6.9 mg/mL) |

0 |

2.12 ± 0.35 |

96.80 ± 0.31 |

1.08 ± 0.12 |

100.00 |