1. Introduction

Dental fear is a type of anxiety, is a psychological state that often leads to a perpetuating pattern of avoidance or hesitation in seeking dental care, thus resulting in a negative experience during dental visits [

1]. It often precedes the trustworthy challenge with unsettling stimuli, which can sometimes be challenging to identify. [

2]. For many children, visiting a dentist is considered a fearful and stressful experience.

According to various studies 5-20% of children, experience the fear of visiting the dentist [

3,

4], this fear of dental procedures results in delaying dental treatment which further deteriorates children’s oral health [

5,

6]. The fear of going to the dentist and the difficulty in obtaining regular dental care because of dental anxiety is a prevalent issue that ranks fifth among the most feared experiences for people. [

7]. Among children, dental anxiety can be considered a major barrier in providing proper patient management, can lead to disruptive behavior during treatment, and might manifest as dental avoidance in adult life leading to poor oral health outcomes.

A pediatric dentist is a specialist who has the ability and the techniques required to manage a child with anxiety, to assist children in becoming more lenient toward accepting dental care. Thus Measuring dental anxiety in children is crucial not just for delivering high-quality clinical care, but also for recognizing the anxiety levels before treatment and the factors contributing to it. This will enable the dentist to identify anxious children, ensuring improved management of their anxiety and helping to alter their views of dentists and dental appointments. As a result, behavioral science plays a key role in dentistry, focusing on and measuring patients' behaviors toward dental treatment.

To evaluate dental anxiety, single and multiple-item self-reporting questionnaires are available. A few such popularly used multi-item scales are Corah’s Dental Anxiety Scale (CDAS) [

8], Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) [

9], Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [

10], and many more. Spielberger developed the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children State form (STAIC-S) which contains 20 items and offers high reliability and satisfactory validity [

10]. An anxiety scale is considered ideal when it combines various factors such as ease of use clinically, less time-consuming, and applicability in young children with minimal cognitive and linguistic skills. In the Japanese language emoji means e(picture)+moji(character). The shortened version of the STAI contains six statements. The scoring for this brief STAI varies between 6 and 24 points, with 6 points indicating no anxiety and 24 points signifying the highest level of anxiety. [

11]. The Emojis method was used with the short STAI to more effectively align with the cognitive and communicative abilities and preferences of younger children, allowing them to convey their anxiety on their own.

Frequently, self-reported survey data is sourced from adults, including parents or referring dentists, rather than directly from children themselves. This approach may not accurately represent the children's experiences, as it relies heavily on others' perceptions and predictions [

12]. Children are regarded as capable of expressing their anxieties through questionnaires starting at the age of five; however, healthcare professionals typically rely on parents to offer precise details about their children's dental anxiety. [

13,

14]. Research conducted in the UK, USA, and Europe has evaluated the link between children’s self-reported dental anxiety and the reports provided by their parents or carers, showing a low correlation that tends to favor the children's own assessments [

15,

16]. In Saudi Arabia, there appears to be a lack of studies investigating the relationship between children's self-reported anxiety levels and the anxiety levels reported by their parents regarding dental situations involving their children.

This study aimed to assess dental anxiety among children and parents using the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale and Modified Short STAI (Emoji) scale.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was conducted following approval from the Institutional Review Board at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (Approval No-SCBR-017-2023). Two hundred children visiting the pediatric dental clinics at the College of Dentistry, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, were randomly selected for the study. The age group of children was between 6 – 9 years. The sample size was considered by assuming to detect a simple correlation of at least r = 0.2 using a two-sided test at a 5% significance level test (α=0.05) with a power of 80% (β=0.2), the required sample size was approximate to 194 which was rounded to 200. Healthy children who provided their assent and their parents gave their informed consent to participate in the sutdy were recruited. Children with a previous history of dental experience were excluded hence, it was the first dental visit of the child. The research was conducted following approval from the Institutional Review Board at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (Approval No-SCBR-017-2023).

The current study utilized two anxiety assessment tools: the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) and a revised brief State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). The MDAS consists of five questions (see Table S1). Each question offers five response options, with scores ranging from 1 (not anxious) to 5 (extremely anxious) assigned to each option. The scores from the five questions were totaled to obtain an overall dental anxiety score. A score of 19 or higher indicates extreme dental anxiety, a score between 12 and 19 suggests mild dental anxiety and a score ranging from 5 to 11 denotes no anxiety.

Table 1.

A Modified Dental Anxiety Scale Questions.

Table 1.

A Modified Dental Anxiety Scale Questions.

| Sl no |

Questions |

| 1 |

If you had to go to the dentist for checkup tomorrow, how would you feel? |

| 2 |

If you were sitting in the waiting room, how would you feel? |

| 3 |

If you were about to have a tooth drilled, how would you feel? |

| 4 |

If you were about to have your teeth scaled and polished, how would you feel? |

| 5 |

If you were about to receive local anaesthetic injection in your gum, how would you feel? |

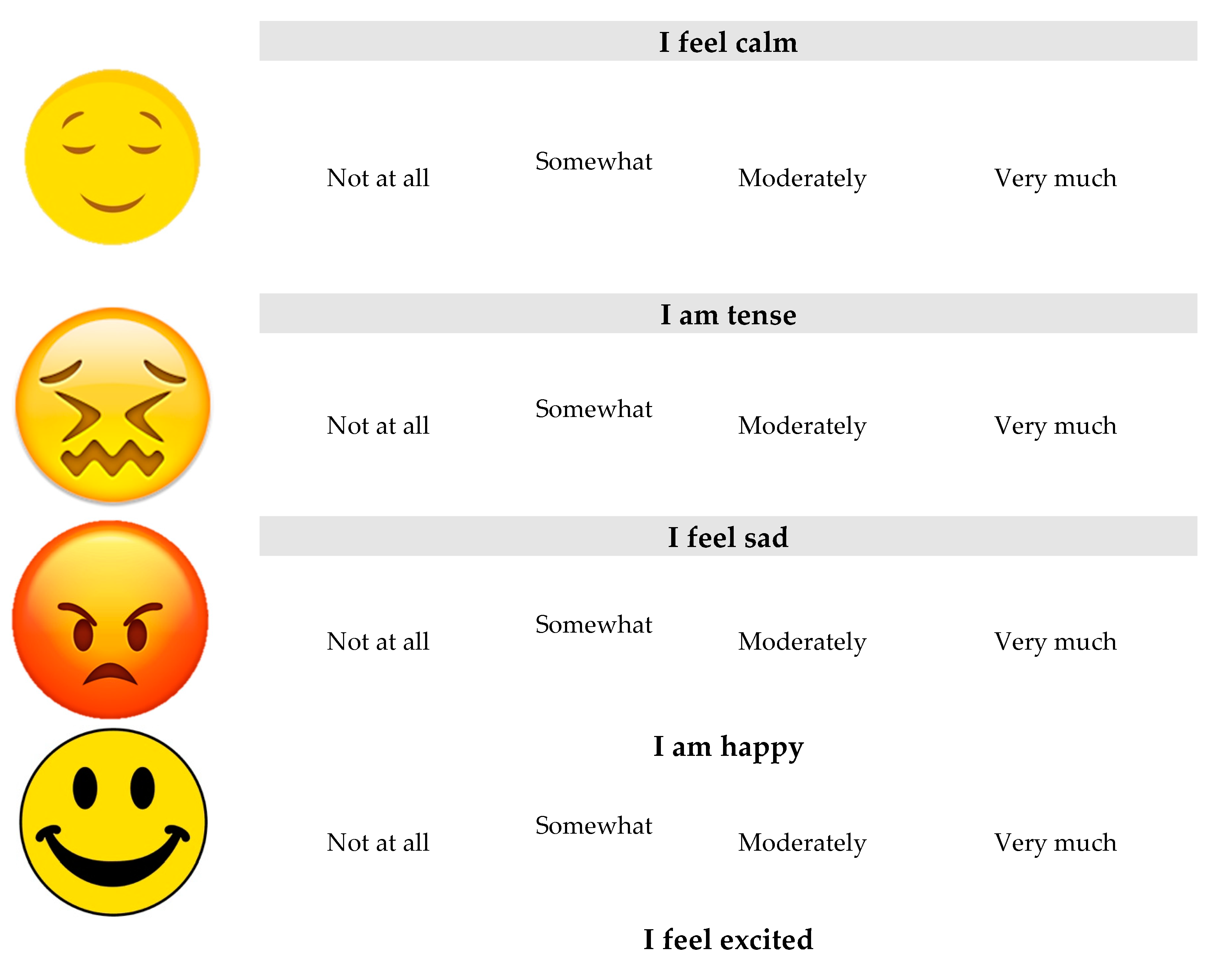

A revised short State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) by Stefan Nilsson et al. involved converting six statements into six emoji faces for use in a study with children. The researchers selected these images to align with the emotions expressed in the original short STAI (Figure S1). Three of the emoji faces express negative emotions, specifically tenseness, sadness, and fear, while the other three exhibit positive emotions, representing calmness, excitement, and happiness. Children can choose from these six emoji faces on an electronic device. This modified and user-friendly approach aims to capture individual feelings and preferences. The children were requested to express their feelings before and after the dental procedure. Each item reflecting their state and traits was provided on a 4-point scale where 1 represents not at all, 2 represents somewhat, 3 represents moderately, and 4 represents very much. The child is presented with facial expression emojis one at a time and is then asked to select each one based on their preference. Ultimately, the tool calculates a score indicating the child’s level of anxiety. The scoring range for this tool is between 6 to 24 points, with 6 points indicating no anxiety and 24 points indicating the highest possible level of anxiety. Every facial expression was captured and analyzed by a single researcher. The parents of all participating children assessed their children's anxiety levels before and after the dental procedure using the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale and a modified short State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) through an emoji method.

Figure 1.

Modified Short STAI (state-trait anxiety inventory).

Figure 1.

Modified Short STAI (state-trait anxiety inventory).

Anxiety scores were evaluated pre- and post-treatment, and a paired t-test was used for comparison. To analyze the relationship between proxy scores and the children's self-reported anxiety, Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted. The data were processed with appropriate statistical methods using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.), applying a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 200 young participants were involved in the study, including 112 boys (56%) and 88 girls (44%).The distribution of study children had a mean age was 7.82 for boys and 8.04 for girls. The mean age was statistically non-significant according to gender.

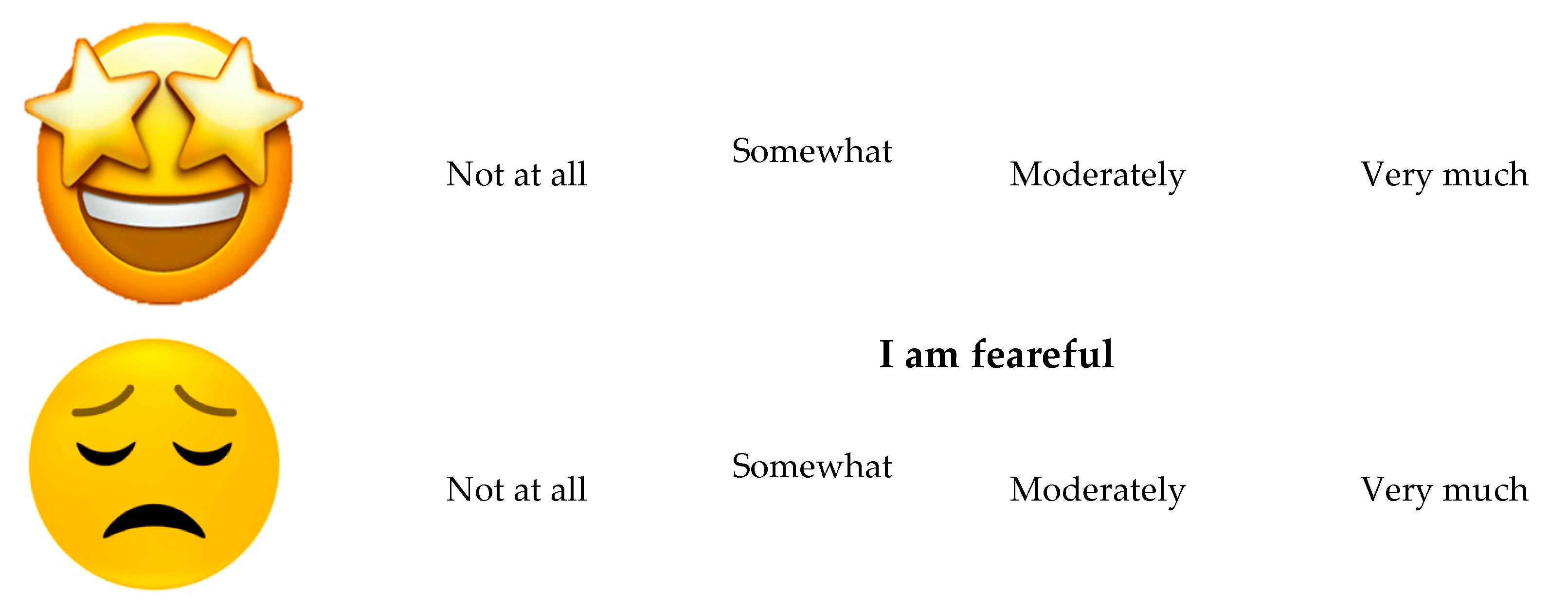

As shown in

Table 2 the perception of children MDAS was found to have a highest mean score of 14.54±3.82 before the dental procedure than compared to the mean score of 9.40 ±2.90 after the dental procedure, this difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). Similarly for the parents the perception of MDAS was higher before treatment (12.84±1.50) compared to after treatment (8.28±2.79). This difference of parental perception was also statistically significant (p<0.001).

Figure 2 shows the modified dental anxiety scores of children and parents before and after the procedure. In both the groups the dental anxiety score was higher before the procedure than that after the procedure.

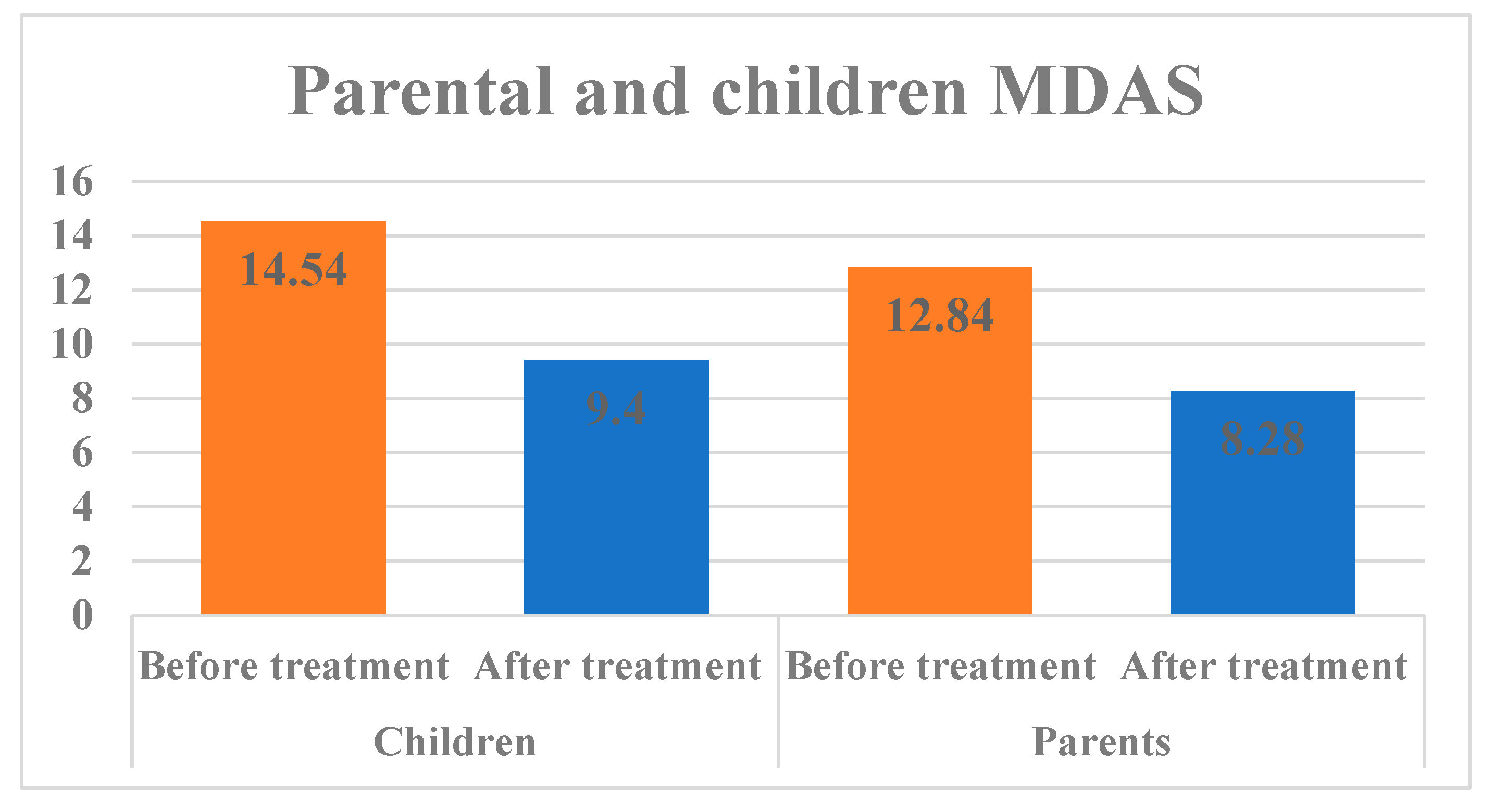

Table 3 shows the modified short STAI scale scores for parents and children. In children, the anxiety rating scores were almost similar before and after treatment this was statistically non-significant (p>0.05) but highlights a slight reduction of anxiety score after the procedure. For parents, the comparison before and after the procedure was found to be statistically significant (p<0.05). When comparing the modified STAI scale scores of children and parents before and after the procedure, the dental anxiety score was higher before the procedure than after the procedure, as shown in

Figure 3. The average anxiety scores of parents based on their education level and socioeconomic status showed no significant differences (refer to

Table 4). Nevertheless, a significant difference was noted in the MDAS when examining the relationship between the anxiety scores of parents and their children post-dental procedure, as well as in the modified STAI scale prior to the dental procedure, as indicated in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

This study investigated dental anxiety among children and parents in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Previous research has shown that dental anxiety is a real phenomenon and is prevalent worldwide among children with the effects of it persisting into adolescence and, in turn, may lead to disruptive behavior during treatment, which can be distressing to the child, parents, and dental practitioner [

18,

19]. Fear and anxiety related to dental procedures can lead both children and their parents to postpone necessary dental care. Numerous studies have investigated levels of dental anxiety in children; however, accurately measuring this anxiety is challenging [

20,

22]. To more effectively evaluate anxiety in children, dentists often employ specially designed scales tailored for pediatric use. This study examined the dental anxiety levels of both children and their parents using the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale and the modified STAI scale, which are among the most commonly utilized tools for assessing dental anxiety and were created to gauge psychological stress [

23]. An important aspect of this study was that the study was conducted in the dental office setting rather than conducted in a school or other more calming environment. In the present study, 38% of children were seen with a score of 15-20 for MDAS before the dental procedure which is considered to be moderately to severely anxious. This finding is more than the anxiety levels observed by Kothari S et al who noted 16.8% of the anxious children in their study [

24]. Dental anxiety arises from multiple factors, and one significant environmental influence is the dental fear exhibited by parents, which closely correlates with that of their children [

25]. A mother’s anxiety during childhood may lead to less cooperative behaviors in her children. Additionally, parental anxiety can affect how well a child is mentally prepared for dental procedures, which may hinder the effectiveness of dental care [

26]. Prior research indicates that anxiety experienced during dental procedures in children is closely linked to traumatic and negative dental experiences [

27,

28]. Therefore, in this study, we focused exclusively on children attending their initial dental appointment. Also in the present study, the type of experience during dental care was not considered to make all the children standardized for the same type of dental procedure. Our results found no relationship observed between the educational and socio-economic status of the parent and the anxiety levels. Research indicates that children from families with lower incomes are more prone to experience anxiety during dental visits compared to those from higher-income families. Additionally, it has been noted that dental anxiety is observed more frequently in women than in men[

29,

30]. Therefore, in this study, we have considered only mothers for proxy evaluation of the anxiety levels of children. When examining the connection between the anxiety levels of parents and their children before and after dental procedures, the findings indicated a positive correlation between the anxiety levels of parents and those of their children at both observed times (p<0.05). The possibility of parents unintentionally passing on their fear of dental procedures to their children in clinical settings is well-established by the results of this study. These findings align with those of Themessl-Huber et al., who conducted a meta-analysis revealing a significant link between parental and child dental anxiety [

31]. Additional research also indicates a connection between the anxiety levels of parents and their children [

32,

33]. Our findings also revealed a notable positive decrease in children's anxiety levels from before the dental procedure to after it. Therefore, it was observed that children's anxiety levels diminished over time, consistent with the work of Oppenheim MN et al., who investigated children's cooperative behavior during dental examinations and subsequent treatment visits, concluding that cooperation improved on the second visit [

34]. Furthermore, another study demonstrated that many children experienced anxiety during their initial dental treatment visit [

35]. In children, the MDAS score was very high before the dental procedure this could be due to the difficulty in rating the scale compared to the modified short STAI (emoji) scale. These findings align with an earlier study in which the researchers observed that all children showed enhanced behavior during later visits. [

36]. However, the literature does lack the relationship of parental anxiety levels as a proxy for child anxiety, hence further research is necessary to explore this aspect.

5. Conclusions

In the current investigation, we assessed how parental anxiety affects children's behavior and examined the levels of children's dental anxiety both before and following a dental procedure. Our results indicate that parents' levels of dental anxiety may impact their children's anxiety levels. Consequently, recognizing the anxiety levels of parents who accompany their children can assist clinicians in customizing behavior management techniques for the child. The majority of children displayed a reduction in dental anxiety levels after the dental procedure. Therefore, with procedural experience, the child's response may be improved, and therefore, the modified short STAI (emoji) scale is fairly ideal for assessing anxiety levels in young children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.S., A.K., A.D., A.A. (Abdulaziz AlMakenzi); methodology, R.B.S., A.A. (AlWaleed Abushanan), A.A. (Abdulfatah Alazmah), A.Q. (Adel S. Alqarni);validation, R.B.S., A.A. (AlWaleed Abushanan), A.A. (Abdulfatah Alazmah); investigation, R.B.S., A.K., A.D., A.A. (Abdulaziz AlMakenzi); resources, A.A. (AlWaleed Abushanan), A.A. (Abdulfatah Alazmah), H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.S., A.A. (AlWaleed Abushanan), A.A. (Abdulfatah Alazmah), A.Q.,A.K., A.D., A.A. (Abdulaziz AlMakenzi); writing—review and editing, A.A. (AlWaleed Abushanan), R.B.S., A.A. (Abdulfatah Alazmah), M.A. (Maram Alagla) ; visualization A.A. (Abdulhamid Al Ghwainem), S.A.( Sara Alghamdi), R.B.S.; The authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2024/R/1446).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of College of Dentistry, at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (Approval No-SCBR-017-2023 and date of approval February 14, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding the study via project number (PSAU/2024/R/1446).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aartman IH1, van Everdingen T, Hoogstraten J, Schuurs AH, Aartman IH, Hoogstraten J, Schuurs AH. Self-report measurement of dental anxiety and fear in children: A critical assessment. ASDC J Dent Child. 1998, 65, 252–258. [Google Scholar]

- Appukuttan, DP. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: literature review. ClinCosmetInvestig Dent. 2016, 8, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra N, Chhabra A, Walia G. Prevalence of dental anxiety and fear among five to ten year old children: a behaviour based cross sectional study. Minerva Stomatol. 2012, 61, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Chang YY, Huang ST. Prevalence of dental anxiety among 5- to 8-year-old Taiwanese children. J Public Health Dent. 2007, 67, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantavuori K, Lahti S, Hausen H, Seppä L, Kärkkäinen S. Dental fear and oral health and family characteristics of Finnish children. ActaOdontol Scand. 2004, 62, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Armfield JM, Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Dental fear and adult oral health in Australia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009, 37, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockerl D, Liddell A, Dempster L, Shapirol D. Age of onset of dental anxiety. J Dent Res. 1999, 78, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corah, NL. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res. 1969, 48, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995, 12, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, CD. Assessment of state and trait anxiety: conceptual and methodological issues. South Psychol. 1985, 2, 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- T. M. Marteau and H. Bekker, “The development of a sixitemshort-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI),” British Journal of Clinical Psychology,vol. 31, part 3, pp. 301–306, 1992.

- Gustafsson A, Arnrup K, Broberg AG, Bodin L, Berggren U. Child dental fear as measured with the Dental Subscale of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule: The impact of referral status and type of informant (child versus parent). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010, 38, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porritt J, Buchanan H, Hall M, Gilchrist F, Marshman Z. Assessing children’s dental anxiety: A systematic review of current measures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013, 41, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard KE, Freeman R. Reliability and validity of a faces version of the modified child dental anxiety scale. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007, 17, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel H, Reid C, Wilson K, Girdler NM. Inter-rater agreement between children’s self-reported and parents’ proxy-reported dental anxiety. Br Dent J. 2015, 218, E6–E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein U, Manangkil R, DeWitt P. Parents’ ability to assess dental fear in their six-to 10-year-old children. Pediatr Dent. 2015, 37, 436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Humphris GM, Dyer TA, Robinson PG. The modified dental anxiety scale: UK general public population norms in 2008 with further psychometrics and effects of age. BMC Oral Health. 2009, 9, 20.

- Klaassen MA, Veerkamp JS, Aartman IH et al. Stressful situations for toddlers: indications for dental anxiety? ASDC J Dent Child. 2002; 69: 306–309.

- Krikken JB, Veerkamp JS. Child rearing styles, dental anxiety and disruptive behaviour; an exploratory study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2008; 9(Suppl. 1): 23–28.

- Afshar H, BaradaranNakhjavani Y, Mahmoudi-Gharaei J, Paryab M, Zadhoosh S. The effect of parental presence on the 5 year-old children’s anxiety and cooperative behavior in the first and second dental visit. Iran J Pediatr. 2011, 21, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara S, Nomura Y, Shingyouchi K, Takase A, Ide M, Moriyasu K et al. Structural relationship of child behavior and its evaluation during dental treatment. J Oral Sci. 2005, 47, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada MK, Tanabe Y, Sano T, Noda T. Cooperation during dental treatment: the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule in Japanese children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002, 12, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönnies S, Mehrstedt M, Eisentraut I. Die Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) und das Dental Fear Survey (DFS) – ZweiMessinstrumentezurErfassung von Zahnbehandlungsängsten. Z Med Psychol. 2002, 11, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari S, Gurunathan D. Factors influencing anxiety levels in children undergoing dental treatment in an undergraduate clinic. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019, 8, 2036–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shindova MP, Belcheva AB. Dental fear and anxiety in children: a review of the environmental factors. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2021, 63, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao X, Hamzah SH, Yiu CK, McGrath C, King NM. Dental fear and anxiety in children and adolescents: qualitative study using YouTube. J Med Internet Res. 2013, 15, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein TO, Akşit-Bıçak D. Management of Post-Traumatic Dental Care Anxiety in Pediatric Dental Practice-A Clinical Study. Children (Basel). 2022, 9, 1146. [Google Scholar]

- Saatchi M, Abtahi M, Mohammadi G, Mirdamadi M, Binandeh ES. The prevalence of dental anxiety and fear in patients referred to Isfahan Dental School, Iran. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2015, 12, 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira MMT, Colares V. The relationship between dental anxiety and dental pain in children aged 18 to 59 months: a study in Recife, Pernambuco state, Brazil. Cad SaudePublica 2009, 25, 743–750. [Google Scholar]

- Soares FC, Lima RA, Santos Cda F, de Barros MV, Colares V. Predictors of dental anxiety in Brazilian 5-7years old children. Compr Psychiatry. 2016, 67, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themessl-Huber M, Freeman R, Humphris G, MacGillivray S, Terzi N. Empirical evidence of the relationship between parental and child dental fear: A structured review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent 2010, 20, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman UW, Lundgren J, Elfström ML, Berggren U. Common use of a fear survey schedule for assessment of dental fear among children and adults. IntJ Paediatr Dent 2008, 18, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee CY, Chang YY, Huang ST. The clinically related predictors of dental fear in Taiwanese children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2008, 18, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim MN, Frankl S. A behavioral analysis of the preschool child when introduced to dentistry by the dentist or hygienist. J Dent Child 1971, 38, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Rayen R, Muthu MS, Chandrasekhar Rao R, Sivakumar N. Evaluation of physiological and behavioral measures in relation to dental anxiety during sequential dental visits in children. Indian J Dent Res 2006, 17, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setty JV, Srinivasan I, Radhakrishna S, Melwani AM, Dr MK. Use of an animated emoji scale as a novel tool for anxiety assessment in children. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2019, 19, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).