Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

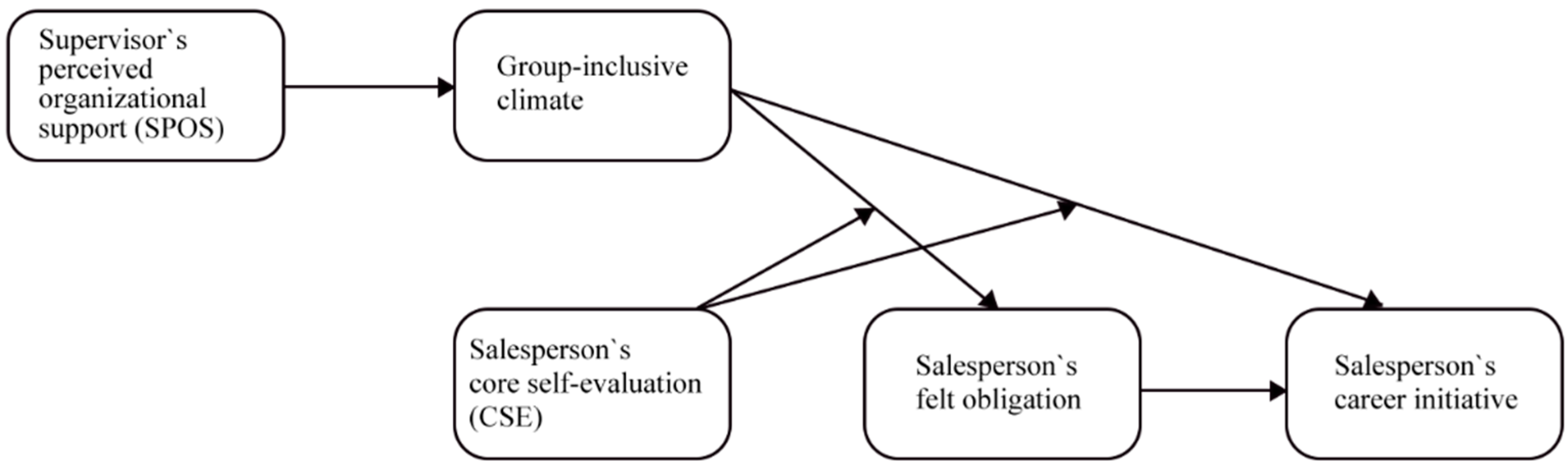

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Supervisor Perceived Organizational Support and Group-Inclusive Climate

2.2. Group-Inclusive Climate, Salesperson's Felt Obligation and Career Initiative

2.3. Salesperson's Core Self-Evaluation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Limits and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables |

|---|

| Supervisor`s perceived organizational support |

| - The organization values my contribution to its well-being. - The organization strongly considers my goals and values. - The organization really cares about my well-being. - The organization is willing to help me when I need a special favor. - The organization shows very little concern for me. (-) - The organization cares about my opinions. - The organization takes pride in my accomplishments at work. |

| Group-inclusive climate |

| - I am treated as a valued member of my work group. - I belong in my work group. - I am connected to my work group. - I believe that my work group is where I am meant to be. - I feel that people really care about me in my work group. - I can bring aspects of myself to this work group that others in the group don’t have in common with me. - People in my work group listen to me even when my views are dissimilar. - While at work, I am comfortable expressing opinions that diverge from my group. - I can share a perspective on work issues that is different from my group members. - When my group’s perspective becomes too narrow, I am able to bring up a new point of view. |

| Salesperson`s Felt obligation |

| - I feel a personal obligation to do whatever I can to help my organization achieve its goals. - I owe it to the organization to give 100% of my energy to organization’s goals while I am at work. - I have an obligation to the organization to ensure that I produce high-quality work. - I owe it to the organization to do what I can to ensure that customers are well-served and satisfied. - I would feel an obligation to take time from my personal schedule to help the organization if it needed my help - I would feel guilty if I did not meet the organization’s performance standards |

| Salesperson`s career initiative |

| - In my work, I set challenging goals. - In my work, I keep trying to learn new things. - With regard to my skills and knowledge, I see to it that I can cope with changes in my work. - I think about how I can keep doing a good job in the future. - In my work, I search for people from whom I can learn something |

| Salesperson`s core self-evaluation |

| - I am confident I will get the success I deserve in life. - Sometimes I feel depressed. (-) - When I try, I generally succeed. - Sometimes when I fail I feel worthless. (-) - I complete tasks successfully. - Sometimes, I do not feel in control of my work. (-) - Overall, I am satisfied with myself. - I am filled with doubts about my competence. (-) - I determine what will happen in my life. - I do not feel in control of my success in my career. (-) - I am capable of coping with most of my problems. - There are times when things look pretty bleak and hopeless to me. (-) |

References

- Shanock, L.; Eisenberger, R. When Supervisors Feel Supported: Relationships with Subordinates' Perceived Supervisor Support, Perceived Organizational Support, and Performance. J. Appl Psychol. 2006, 91, 689-695. [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J. N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M. T.; Buffardi, L. C.; Stewart, K. A.; Adis, C. S. Perceived Organizational Support: A Meta-Analytic Evaluation of Organizational Support Theory. J. Manage. 2017, 43, 1854-1884. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Shoss, M. K.; Karagonlar, G.; Gonzalez-Morales, M. G.; Wickham, R. E.; Buffardi, L. C. The Supervisor Pos-Lmx-Subordinate Pos Chain: Moderation by Reciprocation Wariness and Supervisor's Organizational Embodiment. J. Organ Behav. 2014, 35, 635-656. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S.; Rexwinkel, B.; Lynch, P.; Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl Psychol. 2001, 86, 42-51. [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.; Abuliezi, Z. Leader-Member Exchange and Employee Creativity: Test of a Multilevel Moderated Mediation Model. Hum Perform. 2012, 25, 432-451. [CrossRef]

- Vadera, A. K.; Pratt, M. G.; Mishra, P. Constructive Deviance in Organizations: Integrating and Moving Forward. J. Manage. 2013, 39, 1221-1276. [CrossRef]

- Shore, L. M.; Chung, B. G. Inclusion as a Multi-Level Concept. Curr Opin Psychol. 2024, 60. [CrossRef]

- Randel, A. E.; Galvin, B. M.; Shore, L. M.; Ehrhart, K. H.; Chung, B. G.; Dean, M. A., et al. Inclusive Leadership: Realizing Positive Outcomes through Belongingness and Being Valued for Uniqueness. Hum Resour Manage R. 2018, 28, 190-203. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, W. S.; Otten, S.; van der Zee, K. I.; Jans, L. Inclusion: Conceptualization and Measurement. Eur J. Soc Psychol. 2014, 44, 370-385. [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Do, N. K.; Le, P. B. Arousing a Positive Climate for Knowledge Sharing through Moral Lens: The Mediating Roles of Knowledge-Centered and Collaborative Culture. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1586-1604. [CrossRef]

- Shore, L. M.; Randel, A. E.; Chung, B. G.; Dean, M. A.; Ehrhart, K. H.; Singh, G. Inclusion and Diversity in Work Groups: A Review and Model for Future Research. J. Manage. 2011, 37, 1262-1289. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Connell, J.; Ryan, R. Self-Determination in a Work Organization. J. Appl Psychol. 1989, 74, 580-590. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P. S.; Bergeron, D. M.; Bolino, M. C. No Obligation? How Gender Influences the Relationship Between Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Appl Psychol. 2020, 11, 1338-1350. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Ashill, N.; Lages, C. R.; Homayounfard, A. Understanding the Role of Frontline Employee Felt Obligation in Services. Serv Ind J. 2022, 42, 843-871. [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M.; Ashford, S. J. The Dynamics of Proactivity at Work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3-34. [CrossRef]

- Lyngdoh, T.; Chefor, E.; Lussier, B. Exploring the Influence of Supervisor and Family Work Support on Salespeople's Engagement and Unethical Behaviors. J. Bus Ind Mark. 2023, 38, 1880-1898. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Ding, M. The Influence of Paradoxical Leadership on Adaptive Performance of New-Generation Employees in the Post-Pandemic Era: The Role of Harmonious Work Passion and Core Self-Evaluation. Sustainability-Basel. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhao, G. When Does Newcomer Get Feedback? Relationship Between Supervisor Perceived Organizational Support and Supervisor Developmental Feedback. J. Organ Change Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sears, G. J.; Han, Y. Do Employee Responses to Organizational Support Depend On their Personality? The Joint Moderating Role of Conscientiousness and Emotional Stability. Empl Relat. 2021, 43, 1130-1146. [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.; Locke, E.; Durham, C.; Kluger, A. Dispositional Effects on Job and Life Satisfaction: The Role of Core Evaluations. J. Appl Psychol. 1998, 83, 17-34. [CrossRef]

- Boshoff, C.; Allen, J. The Influence of Selected Antecedents on Frontline Staff's Perceptions of Service Recovery Performance. Int J Inf Syst Serv. 2000, 11, 63-90. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Ferris, D. L.; Johnson, R. E.; Rosen, C. C.; Tan, J. A. Core Self-Evaluations: A Review and Evaluation of the Literature. J. Manage. 2012, 38, 81-128. [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manage. 2005, 31, 874-900. [CrossRef]

- Alghofeli, M.; Bajaba, S.; Alsabban, A.; Basahal, A. Mediating Role of High-Performance Practices and the Moderating Role of Climate for Inclusion. Employ Responsib Rig. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Xu, Z.; Abuliezi, Z.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, Q. Paradoxical Leadership, Team Adaptation and Team Performance: The Mediating Role of Inclusive Climate. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C. Perceived Supervisor Support: Contributions to Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Retention. J. Appl Psychol. 2002, 87, 565-573. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Karagonlar, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Neves, P.; Becker, T. E.; Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., et al. Leader–Member Exchange and Affective Organizational Commitment: The Contribution of Supervisor`S Organizational Embodiment. J. Appl Psychol. 2010, 95, 1085-1103. [CrossRef]

- DeConinck, J. B. The Effect of Organizational Justice, Perceived Organizational Support, and Perceived Supervisor Support on Marketing Employees' Level of Trust. J. Bus Res. 2010, 63, 1349-1355. [CrossRef]

- Puah, L. N.; Ong, L. D.; Chong, W. Y. The Effects of Perceived Organizational Support, Perceived Supervisor Support and Perceived Co-Worker Support on Safety and Health Compliance. Int J Occup Saf Ergo. 2016, 22, 333-339. [CrossRef]

- Cancela, D.; Hulsheger, U. R.; Stutterheim, S. E. The Role of Support for Transgender and Nonbinary Employees: Perceived Co-Worker and Organizational Support's Associations with Job Attitudes and Work Behavior. Psychol Sex Orientat. 2022, 9, 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Ashikali, T.; Groeneveld, S. Diversity Management in Public Organizations and its Effect On Employees` Affective Commitment: The Role of Transformational Leadership and the Inclusiveness of the Organizational Culture. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2015, 35, 146-168. [CrossRef]

- Stamper, C.; Masterson, S. Insider or Outsider? How Employee Perceptions of Insider Status Affect their Work Behavior. J. Organ Behav. 2002, 23, 875-894. [CrossRef]

- Nembhard, I. M.; Edmondson, A. C. Making It Safe: The Effects of Leader Inclusiveness and Professional Status on Psychological Safety and Improvement Efforts in Health Care Teams. J. Organ Behav. 2006, 27, 941-966. [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive Leadership and Employee Involvement in Creative Tasks in the Workplace: The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety. Creativity Res J. 2010, 22, 250-260. [CrossRef]

- Settoon, R.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R. Social Exchange in Organizations: Perceived Organizational Support, Leader-Member Exchange, and Employee Reciprocity. J. Appl Psychol. 1996, 81, 219-227. [CrossRef]

- Mossholder, K.; Settoon, R.; Henagan, S. A Relational Perspective on Turnover: Examining Structural, Attitudinal, and Behavioral Predictors. Acad Manage J. 2005, 48, 607-618. [CrossRef]

- Hacker, W. Activity: A Fruitful Concept in Industrial Psychology. In Goal directed behaviour: The concept of action in psychology, 1st ed.; Frese, M., Sabini, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK; 1985; Chapter 18, pp. 262-284.

- Norton, T. A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N. M. Organisational Sustainability Policies and Employee Green Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Work Climate Perceptions. J. Environ Psychol. 2014, 38, 49-54. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. B.; Tran, T. B. H.; Park, B. Inclusive Leadership and Work Engagement: Mediating Roles of Affective Organizational Commitment and Creativity. Soc Behav Personal. 2015, 43, 931-944. [CrossRef]

- Van Veldhoven, M.; Dorenbosch, L.; Breugelmans, A.; Van De Voorde, K. Exploring the Relationship Between Job Quality, Performance Management, and Career Initiative: A Two-Level, Two-Actor Study. SAGE OPEN. 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Soens, N. Protean Attitude and Career Success: The Mediating Role of Self-Management. J. Vocat Behav. 2008, 73, 449-456. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Frenkel, S. J. Explaining Task Performance and Creativity from Perceived Organizational Support Theory: Which Mechanisms are More Important? J. Organ Behav. 2013, 34, 1165-1181. [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.; Morrow, P. C.; Kessler, I. Serving Two Organizations: Exploring the Employment Relationship of Contracted Employees. Hum Resour Manage-Us. 2006, 45, 561-583. [CrossRef]

- Frese, M.; Fay, D. Personal Initiative: An Active Performance Concept for Work in the 21St Century. Res. Organ. Behav. 2001, 23, 133-187. [CrossRef]

- Santuzzi, A. M.; Martinez, J. J.; Keating, R. T. The Benefits of Inclusion for Disability Measurement in the Workplace. Equal Divers Incl. 2022, 41, 474-490. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shin, H. Effects of Inclusive Leadership on the Diversity Climate and Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Behavioral Sciences. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.; Thoresen, C. The Core Self-Evaluations Scale: Development of a Measure. Pers Psychol. 2003, 56, 303-331. [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E. Self-Determination Theory and Work Motivation. J. Organ Behav. 2005, 26, 331-362. [CrossRef]

- Akosile, A. L.; Ekemen, M. A. The Impact of Core Self-Evaluations on Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention Among Higher Education Academic Staff: Mediating Roles of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Behavioral Sciences. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D. L.; Rosen, C. R.; Johnson, R. E.; Brown, D. J.; Risavy, S. D.; Heller, D. Approach or Avoidance (or Both?): Integrating Core Self-Evaluations within an Approach/Avoidance Framework. Pers Psychol. 2011, 64, 137-161. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, Z.; Su, J.; Luo, Z. Relationship Between Core Self-Evaluations and Team Identification: The Perception of Abusive Supervision and Work Engagement. Curr Psychol. 2020, 39, 121-127. [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T. A.; Jr. Drexler, J. A. Social Support, Autonomy, and Hierarchical Level as Moderators of the Role Characteristics-Outcome Relationship. J. Organ Behav. 1986, 7, 207-214. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl Psychol. 1986, 71, 500-507. [CrossRef]

- Chung, B. G.; Ehrhart, K. H.; Shore, L. M.; Randel, A. E.; Dean, M. A.; Kedharnath, U. Work Group Inclusion: Test of a Scale and Model. Group Organ Manage. 2020, 45, 75-102. [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J.; Curran, P. J.; Bauer, D. J. Computational Tools for Probing Interactions in Multiple Linear Regression, Multilevel Modeling, and Latent Curve Analysis. J. Educ Behav Stat. 2006, 31, 437-448. [CrossRef]

- Chung, B. G.; Shore, L. M.; Wiegand, J. P.; Xu, J. The Effects of Inclusive Psychological Climate, Leader Inclusion, and Workgroup Inclusion on Trust and Organizational Identification. Equal Divers Incl. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kalra, A.; Singh, R.; Badrinarayanan, V.; Gupta, A. How Ethical Leadership and Ethical Self-Leadership Enhance the Effects of Idiosyncratic Deals On Salesperson Work Engagement and Performance. J. Bus Ethics. 2024. [CrossRef]

| Measurement Model | df | /df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized 5-factor model | 769 | 1134.877 | 1.476 | .959 | .957 | .040 |

| M1 4-factor model (combined SPOS and GIC1) | 773 | 2102.931 | 2.720 | .853 | .844 | .076 |

| M2 4-factor model (combined GIC and FO2) | 773 | 2412.591 | 3.121 | .818 | .807 | .084 |

| M3 4-factor model (combined GIC and CI3) | 773 | 2176.510 | 2.816 | .845 | .835 | .078 |

| M4 4-factor model (combined FO and CI) | 773 | 2155.260 | 2.788 | .847 | .838 | .077 |

| Factor | SPOS | GIC | FO | CI | CSE | Mean | S.D. | C.R. | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPOS | (.746)4 | 3.73 | .72 | .909 | .556 | .887 | ||||

| GIC1 | .152**5 | (.759) | 3.33 | .81 | .931 | .576 | .930 | |||

| FO2 | .017 | .489** | (.764) | 3.25 | .94 | .893 | .584 | .937 | ||

| CI3 | -.007 | .407** | .651** | (.716) | 3.09 | .96 | .840 | .512 | .938 | |

| CSE | -.071 | .060 | .474** | .459** | (.756) | 3.44 | .83 | .941 | .572 | .959 |

| Direct Effect | Estimate | S.E. | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPOS → GIC(Hypothesis 1)1 | .171** | .067 | (.057, .278) |

| SPOS → FO2 | -.076 | .066 | (-.183, .039) |

| SPOS → CI3 | -.100 | .054 | (-.201, .002) |

| GIC → FO (Hypothesis 2) | .576*** | .054 | (.477, .660) |

| GIC → CI (Hypothesis 3) | .466*** | .055 | (.372, .556) |

| FO → CI (Hypothesis 4) | .472*** | .048 | (.396, .550) |

| Indirect Effect | Estimate | S.E. | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPOS → GIC1 → FO2 | .098* | .041 | (.032, .169) |

| SPOS → GIC → CI3 | .080* | .032 | (.028, .134) |

| WGIC → FO → CI | .272*** | .038 | (.213, .338) |

| SPOS → GIC → FO → CI (Hypothesis 5) | .046* | .020 | (.017, .081) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FO2 | CI3 | |||||

| Beta | S.E. | 95% C.I. | Beta | S.E. | 95% C.I. | |

| GIC1 | .530*** | .050 | (.432, .628) | .683*** | .045 | (.594, .772) |

| CSE | .516*** | .049 | (.419, .613) | .505*** | .044 | (.418, .593) |

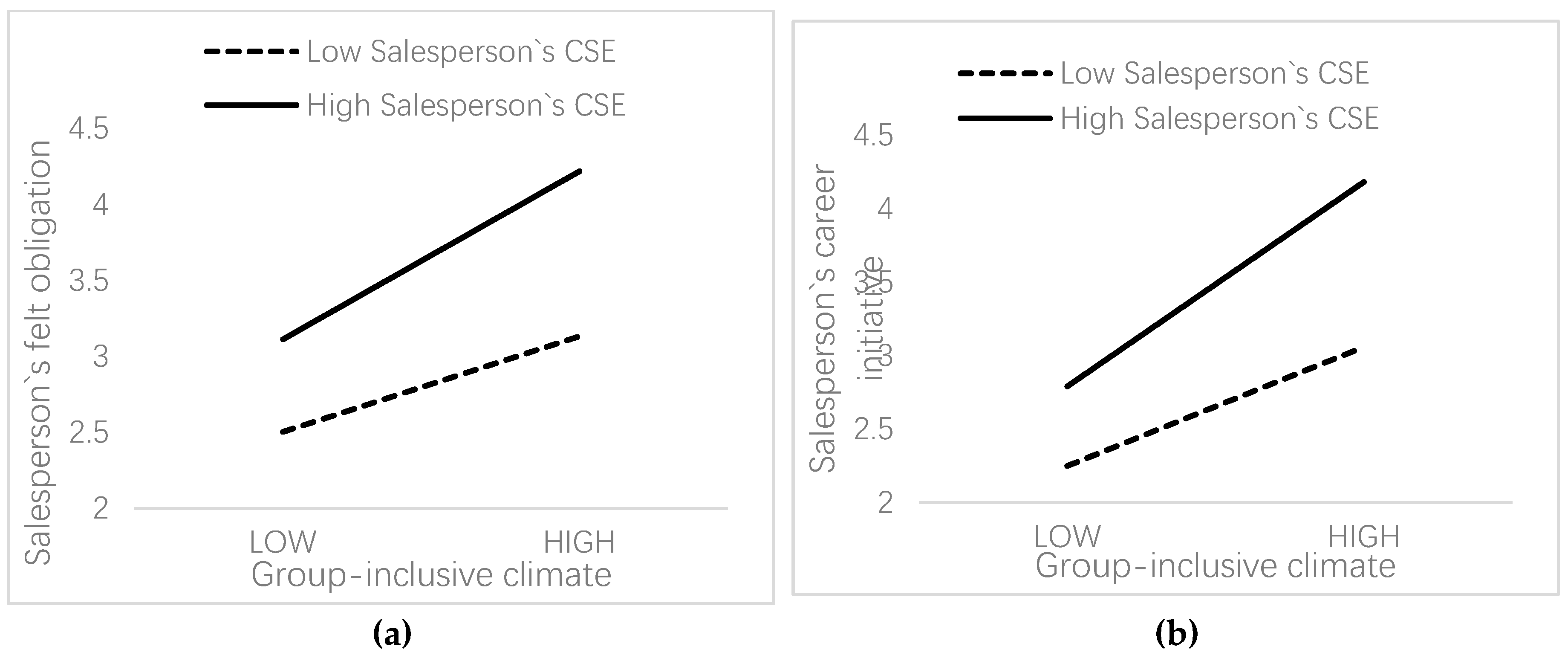

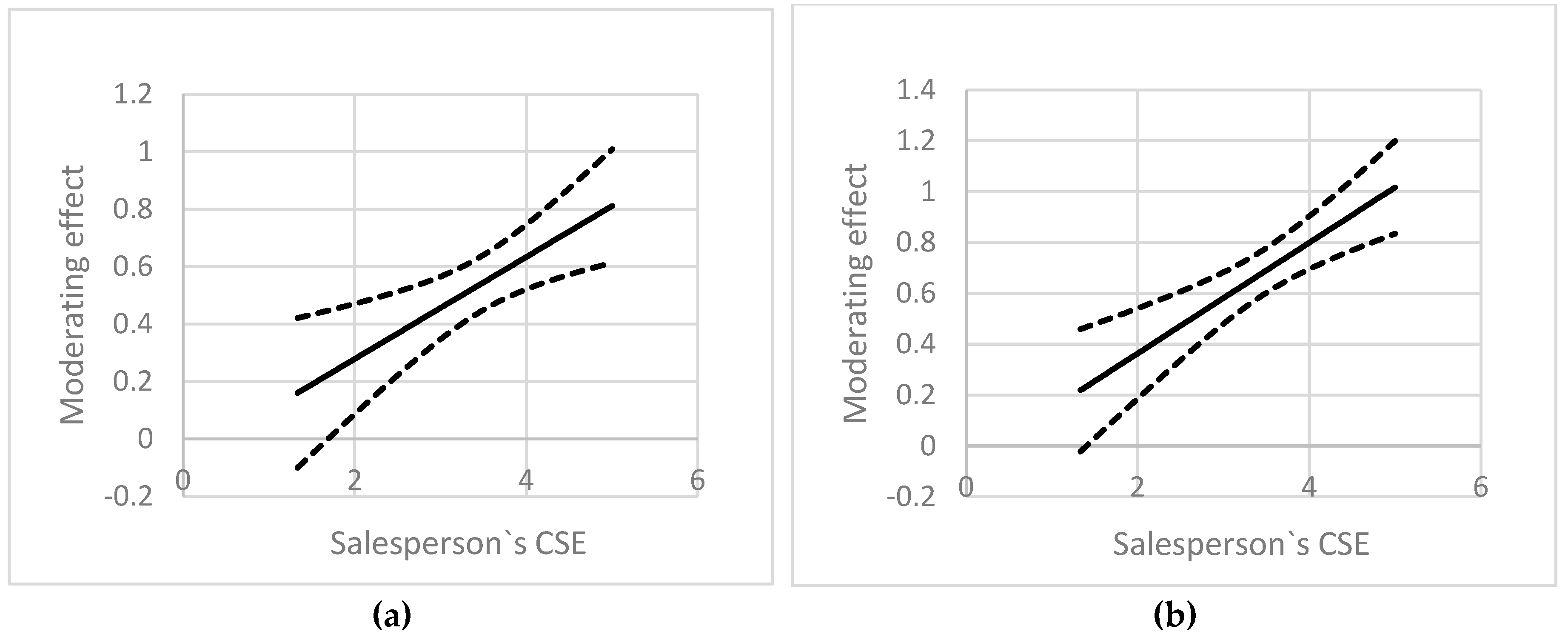

| GIC×CSE (Hypothesis 6) | .174** | .059 | (.058, .291) | .218*** | .054 | (.112, .323) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).