Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

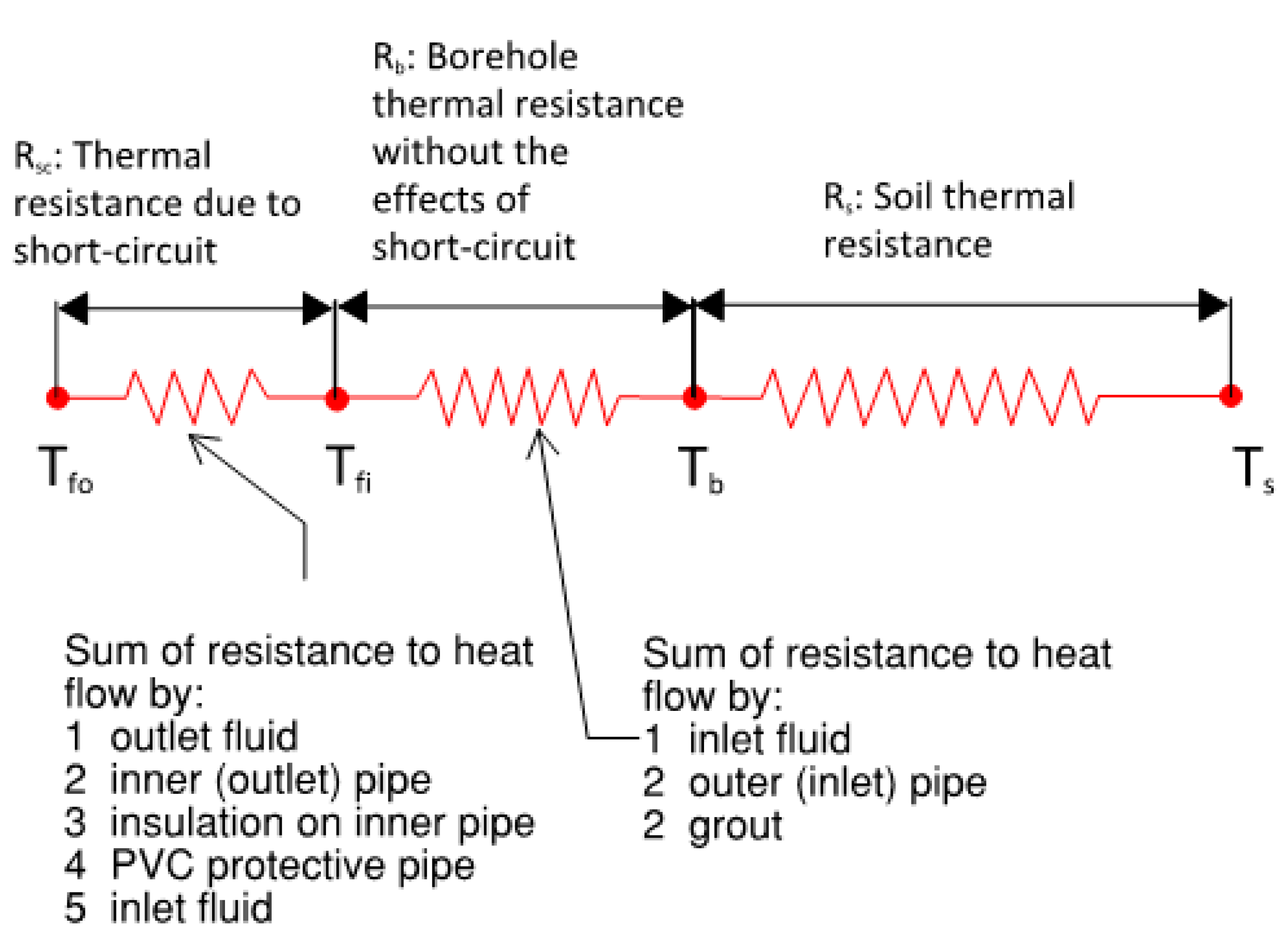

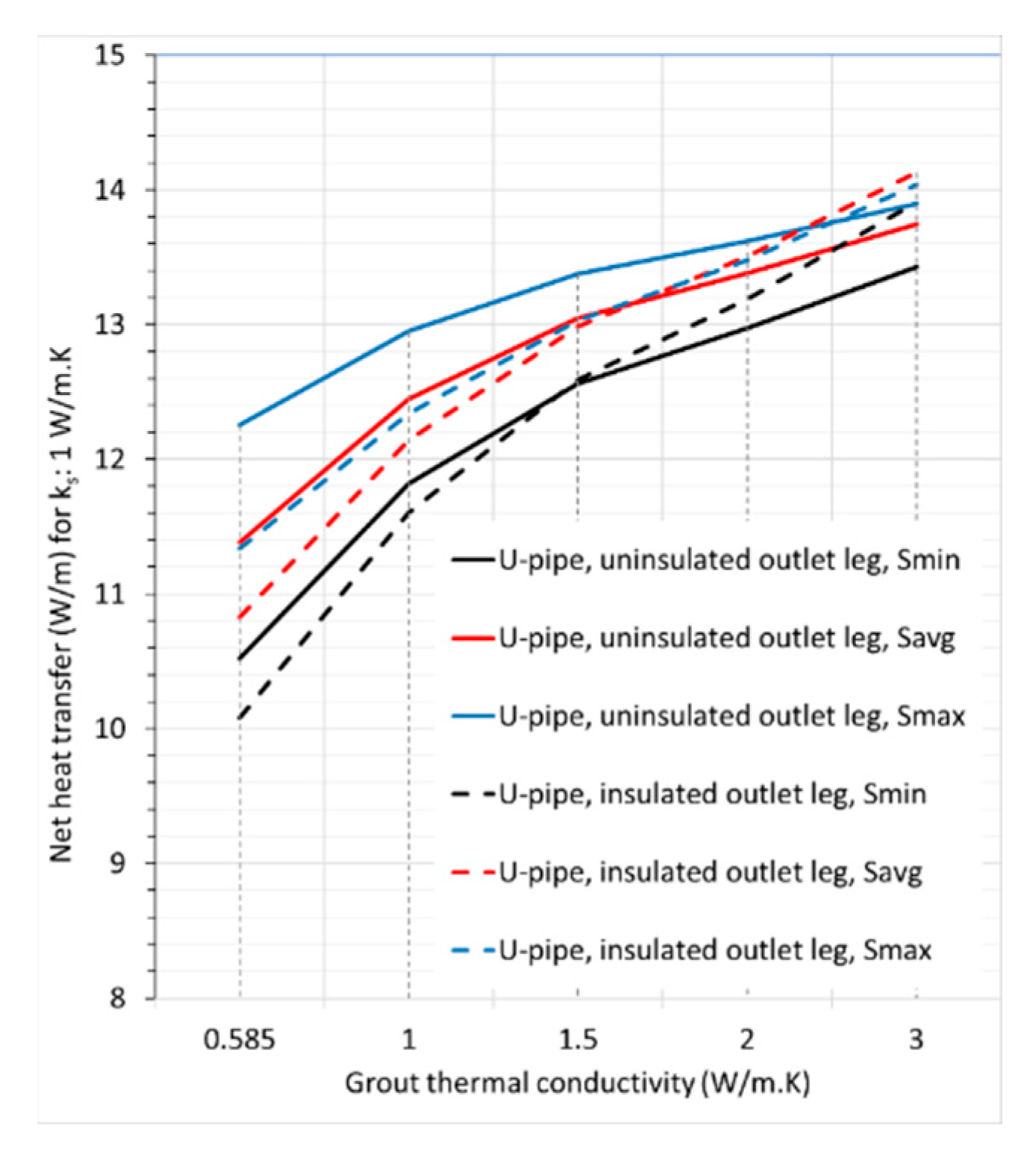

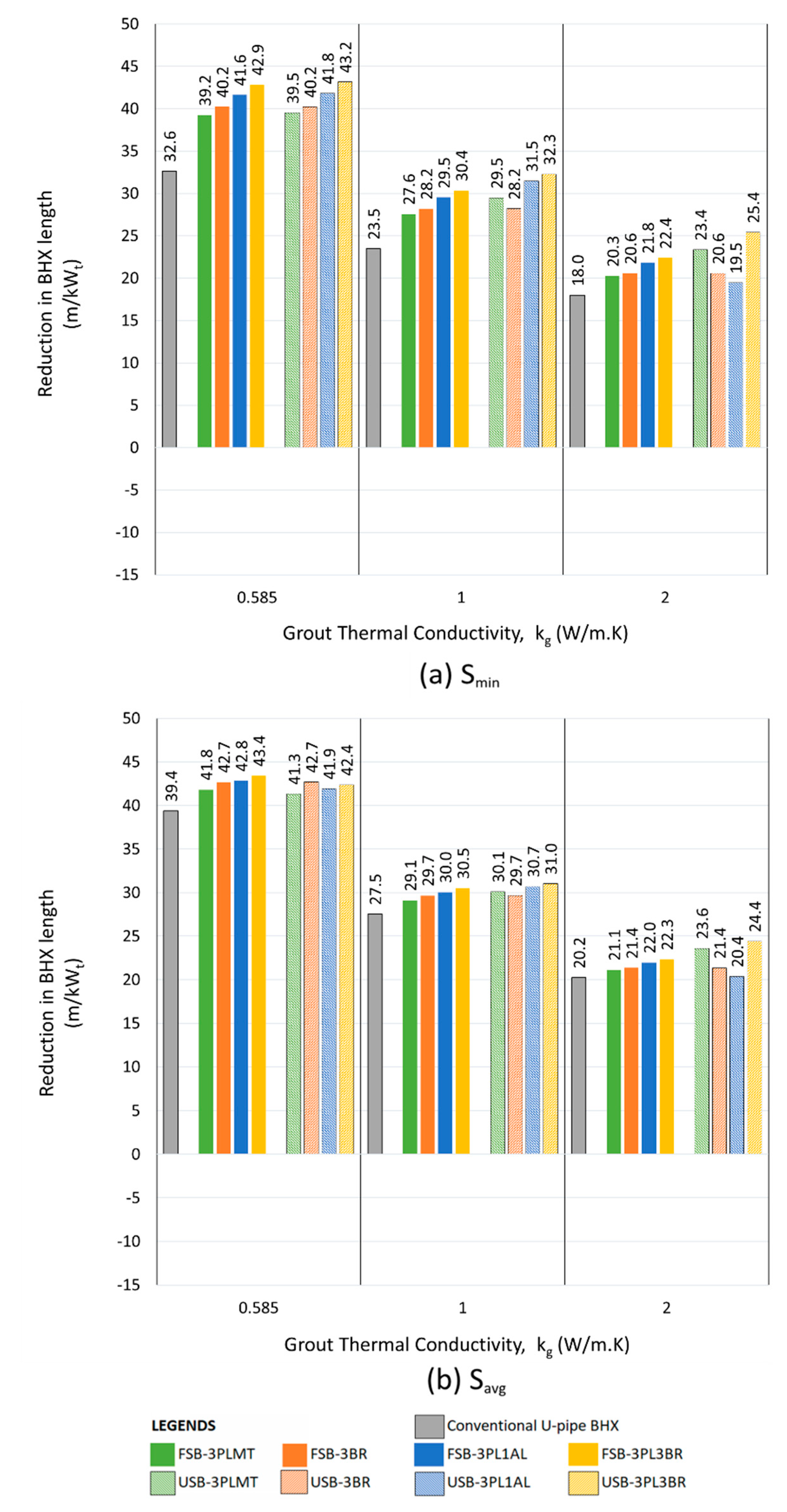

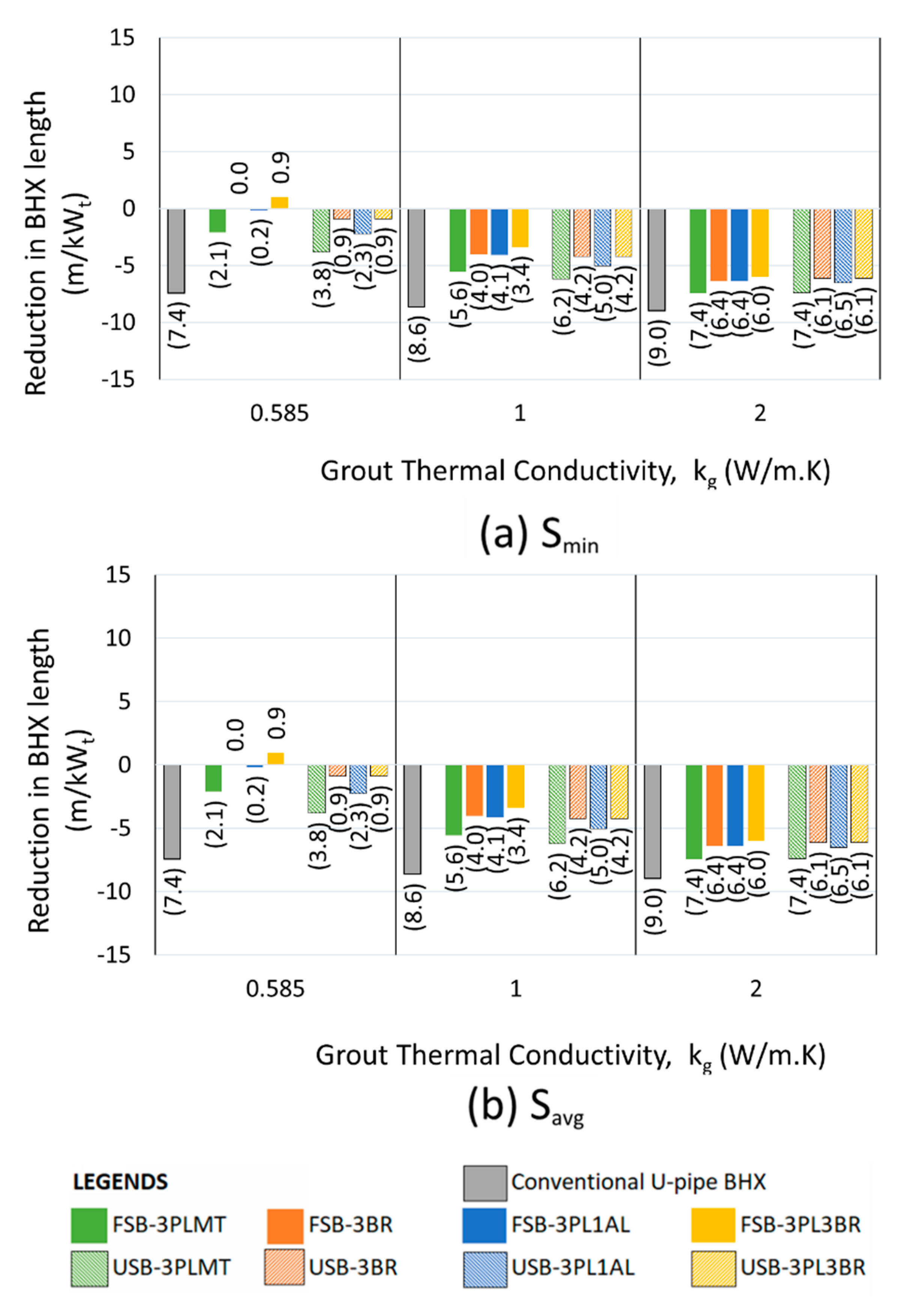

The efficiency of heat transfer through borehole heat exchangers is influenced by the thermal resistances of both the borehole and the surrounding soil. Optimizing these resistances can improve the heat transfer performance and reduce system costs. Soil thermal resistance is geographically specific and challenging to reduce, according to previous research. In contrast, borehole resistance can be minimized through practical approaches, such as increasing the thermal conductivity of the grout or adjusting the shank spacing in the U-tube configuration. Previous literature also suggests coaxial pipes as a more efficient design than single U-tube borehole heat exchanger. A novel approach involves inserting a physical barrier between the U-tube’s inlet and outlet legs to reduce the thermal short-circuiting and/or to improve the temperature distribution from the inlet leg in a U-tube borehole. A limited literature exists on the barrier technique and their contribution to reduce thermal resistance. The effects of two different barrier geometries of flat plate and U-shape of different materials, with various grout and soil thermal conductivities as well as shank spacing configurations have been considered in this study. Using FlexPDE software, the study numerically assesses thermal resistances through the borehole. The study focusses on the sole contribution of barrier in mitigating thermal resistance of U-tube borehole heat exchanger. The study suggests that the barrier technique is an effective solution for optimizing heat transfer through U-tube borehole heat exchangers, especially with reduced shank spacing and lower thermal conductivity soil. It can reduce the length of a U-tube borehole by up to 8.1m/kW of heat transfer offering a viable alternative to increasing shank spacing in the U-tube borehole or enhancing thermal conductivity of the grout. Moreover, under specific conditions of soil and grout with low to medium thermal conductivity, U-tube borehole heat exchanger with a barrier between the legs demonstrates a reduction of up to 43.4m per kW heat transfer (22.7%) in overall length compared to coaxial pipes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Model Assumptions and Governing Equation:

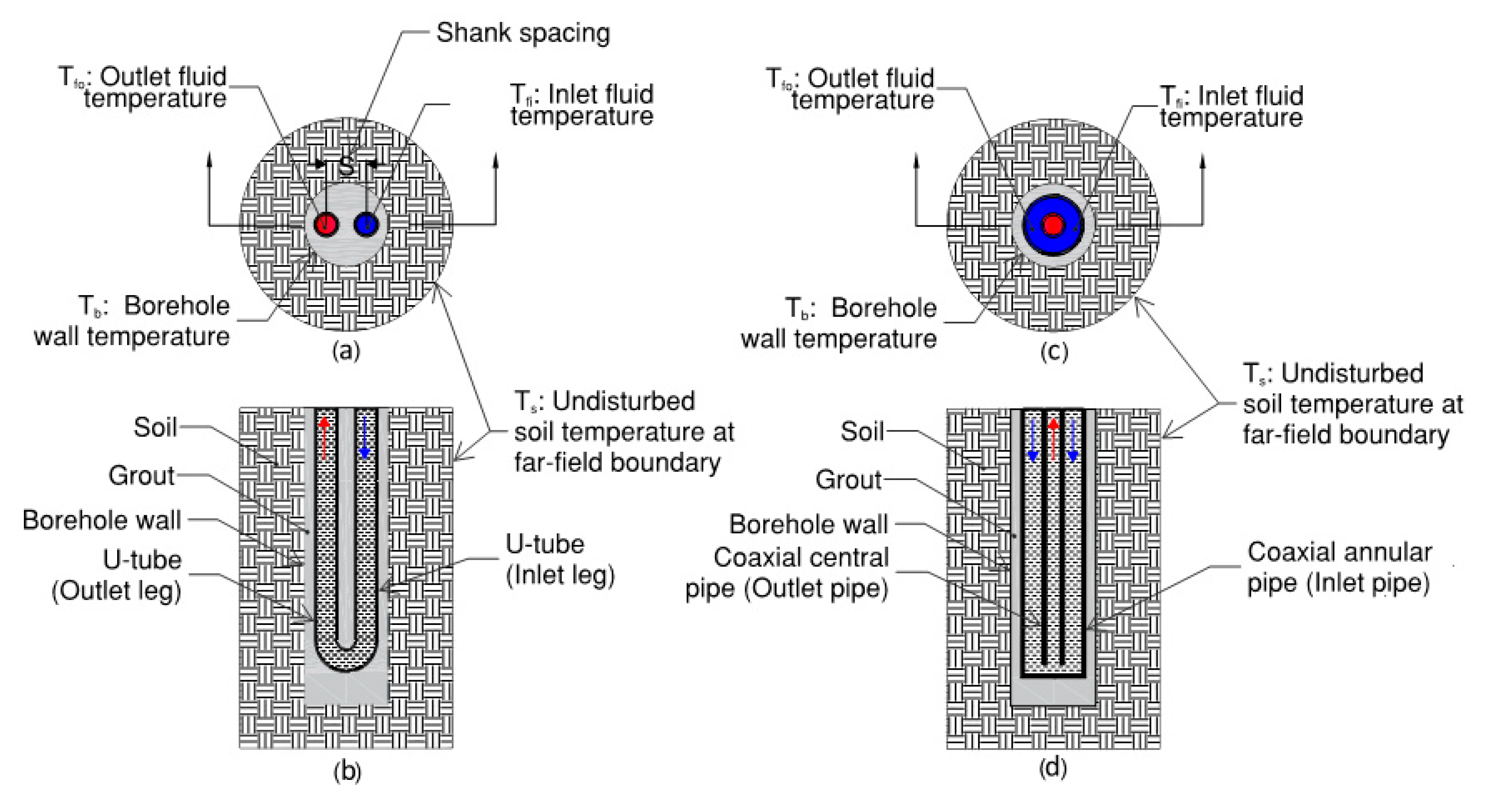

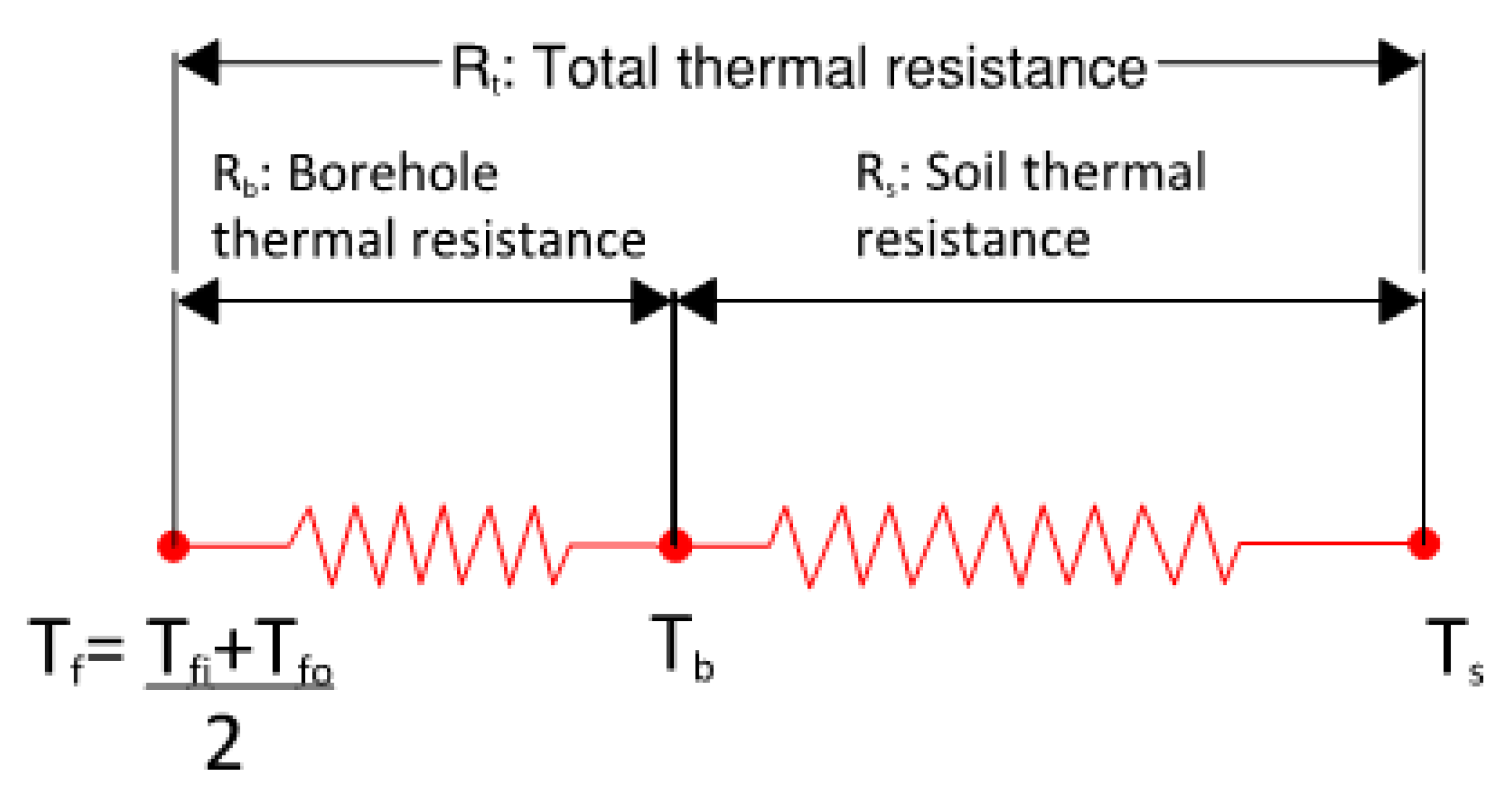

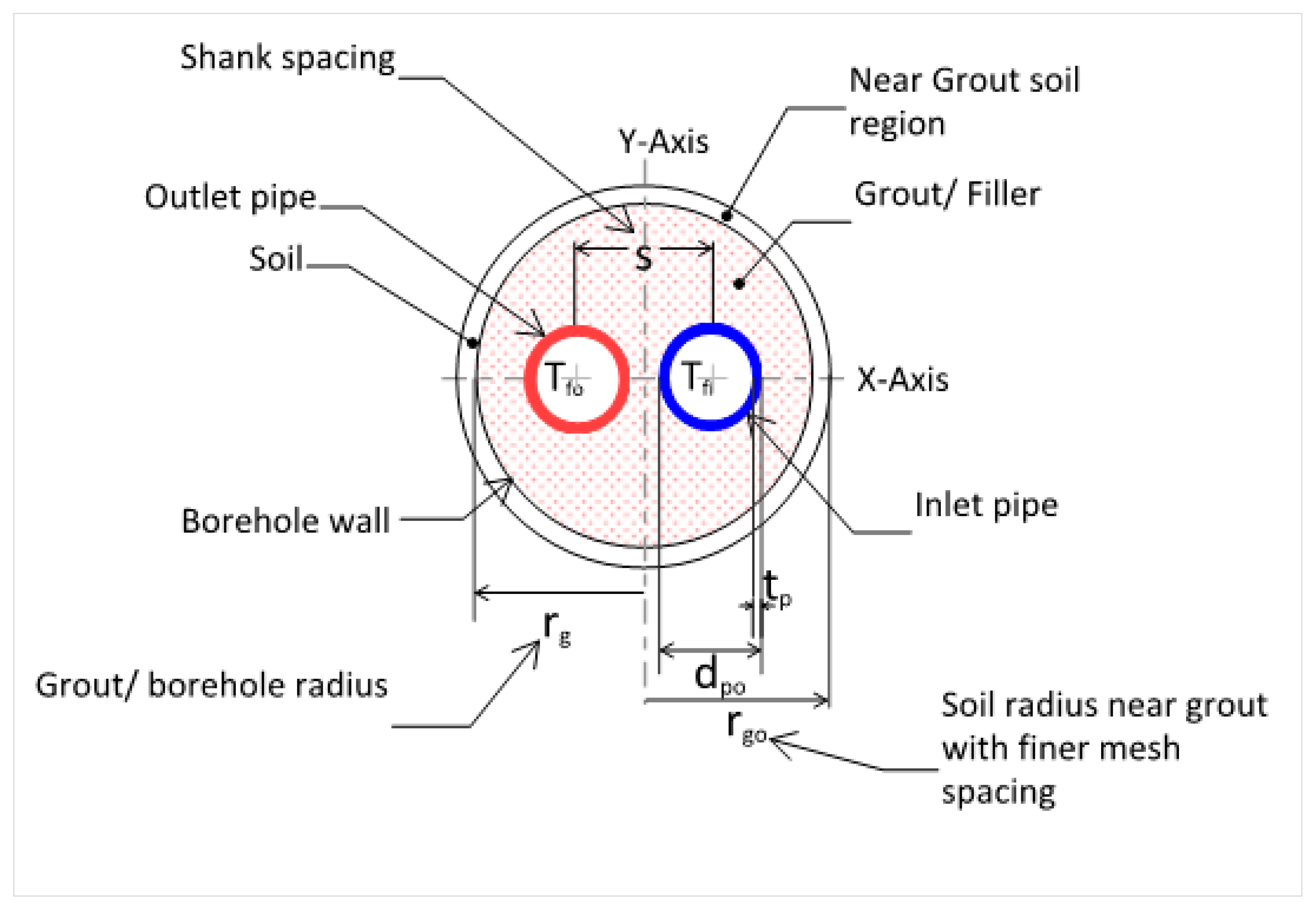

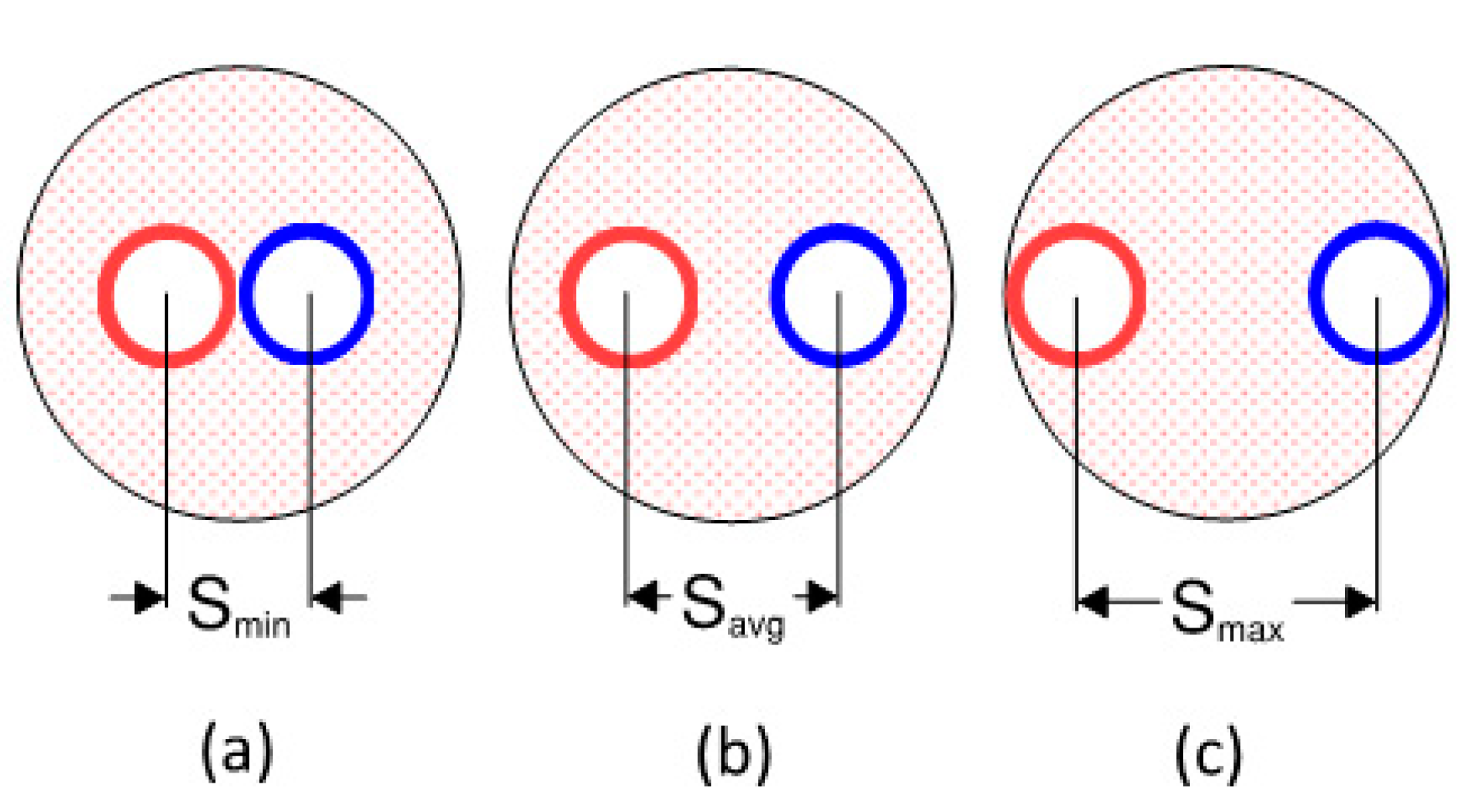

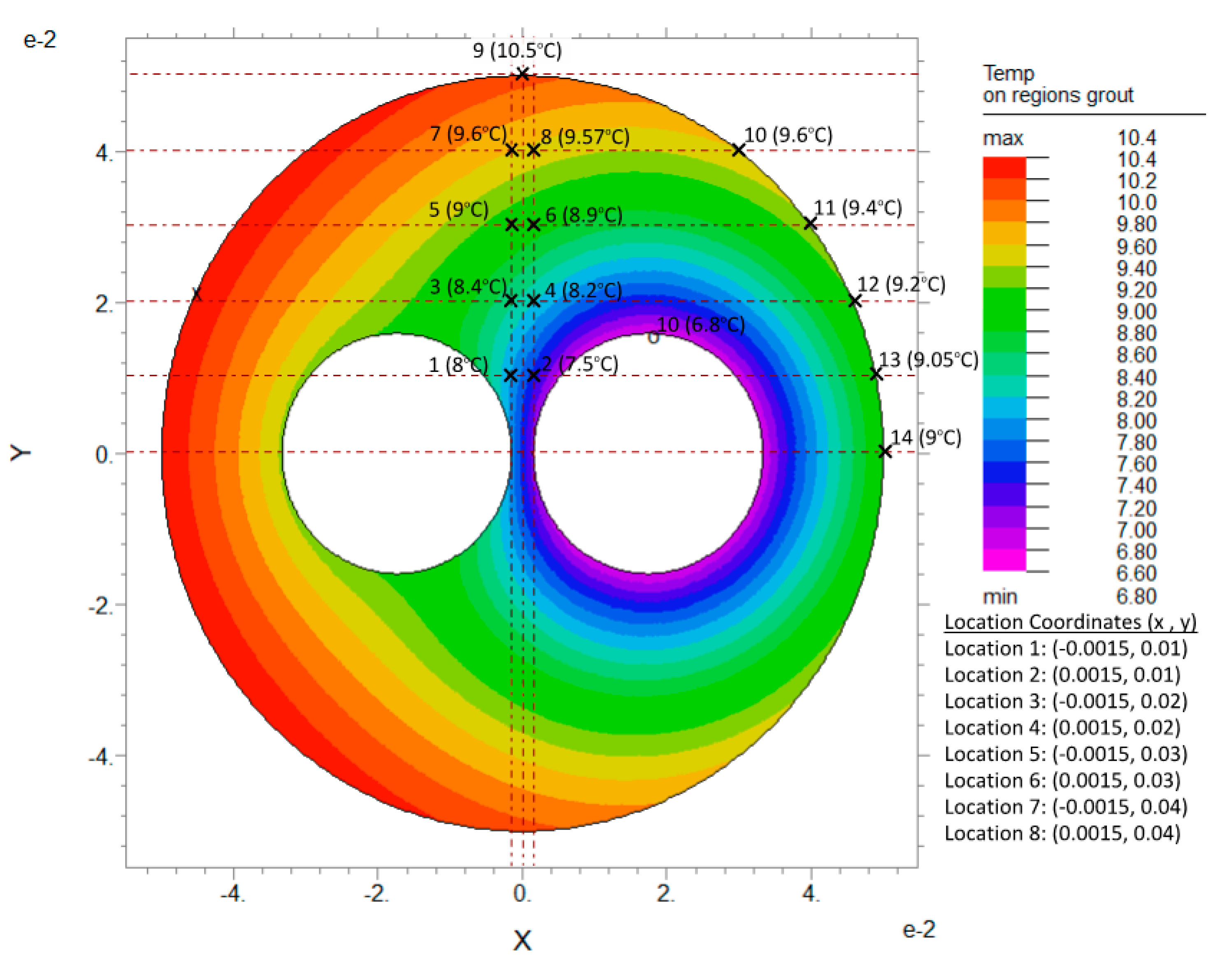

2.2. Analysis for Traditional Single U-Tube Borehole heat Exchanger:

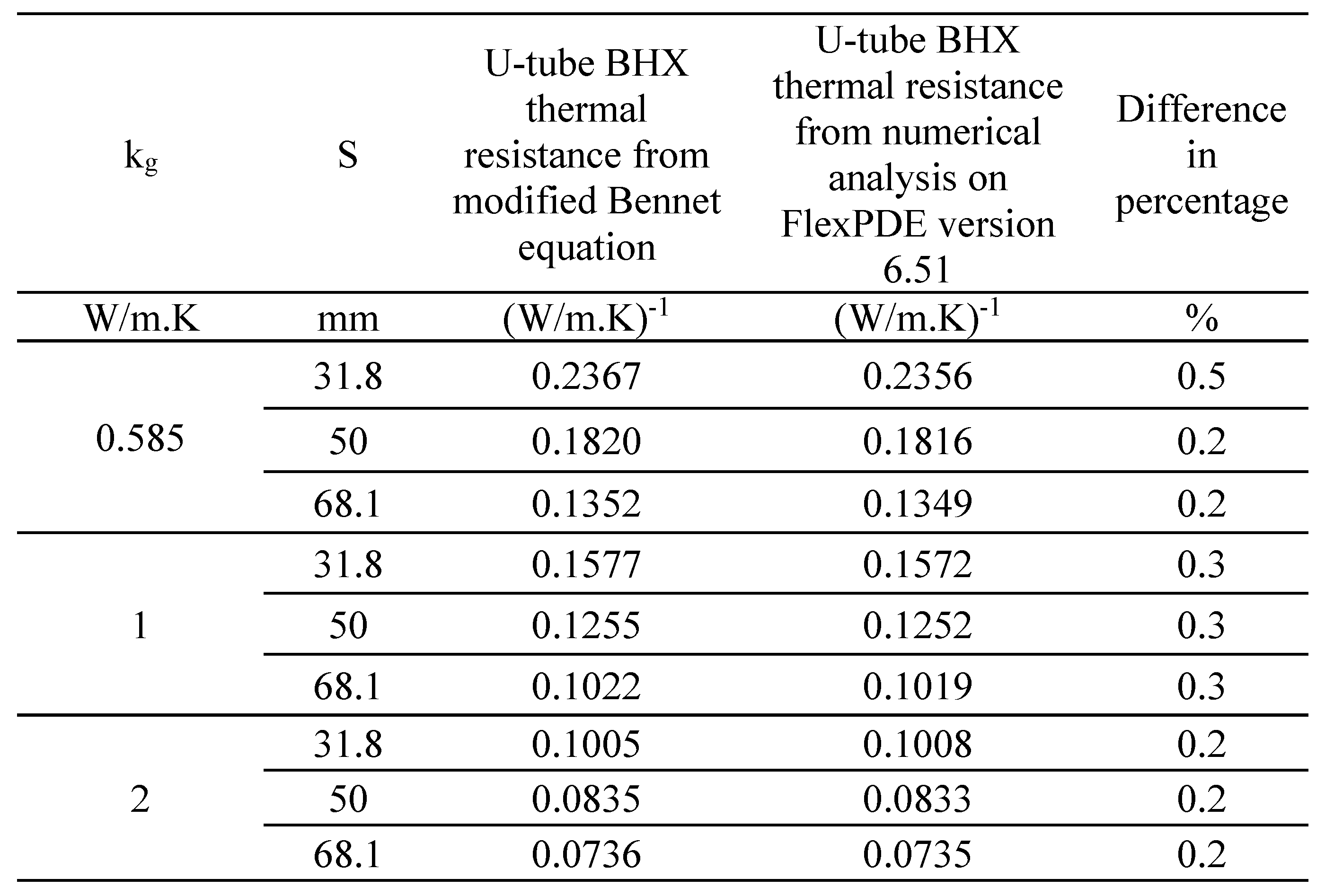

2.3. Validation of the Results of the Numerical Model:

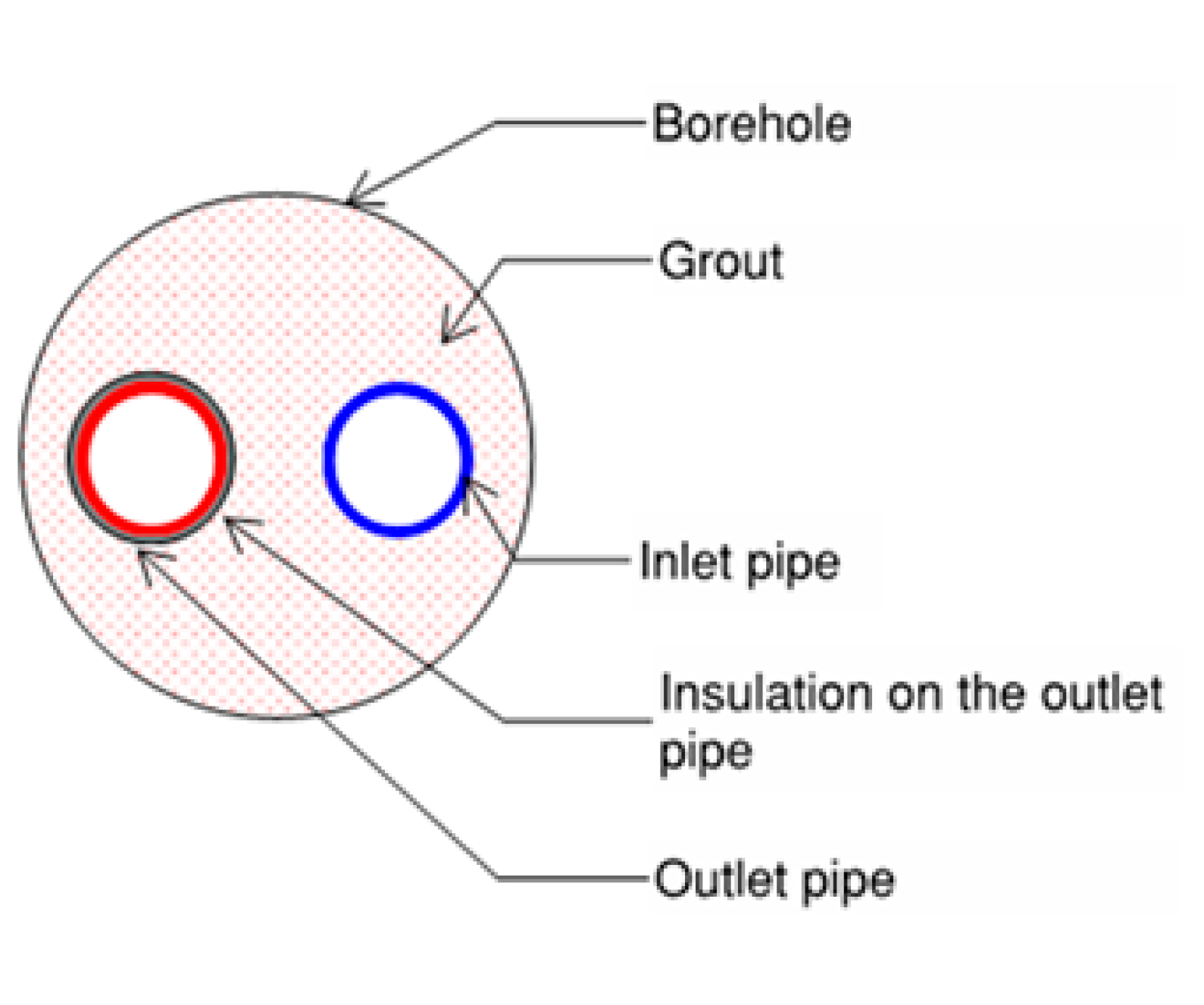

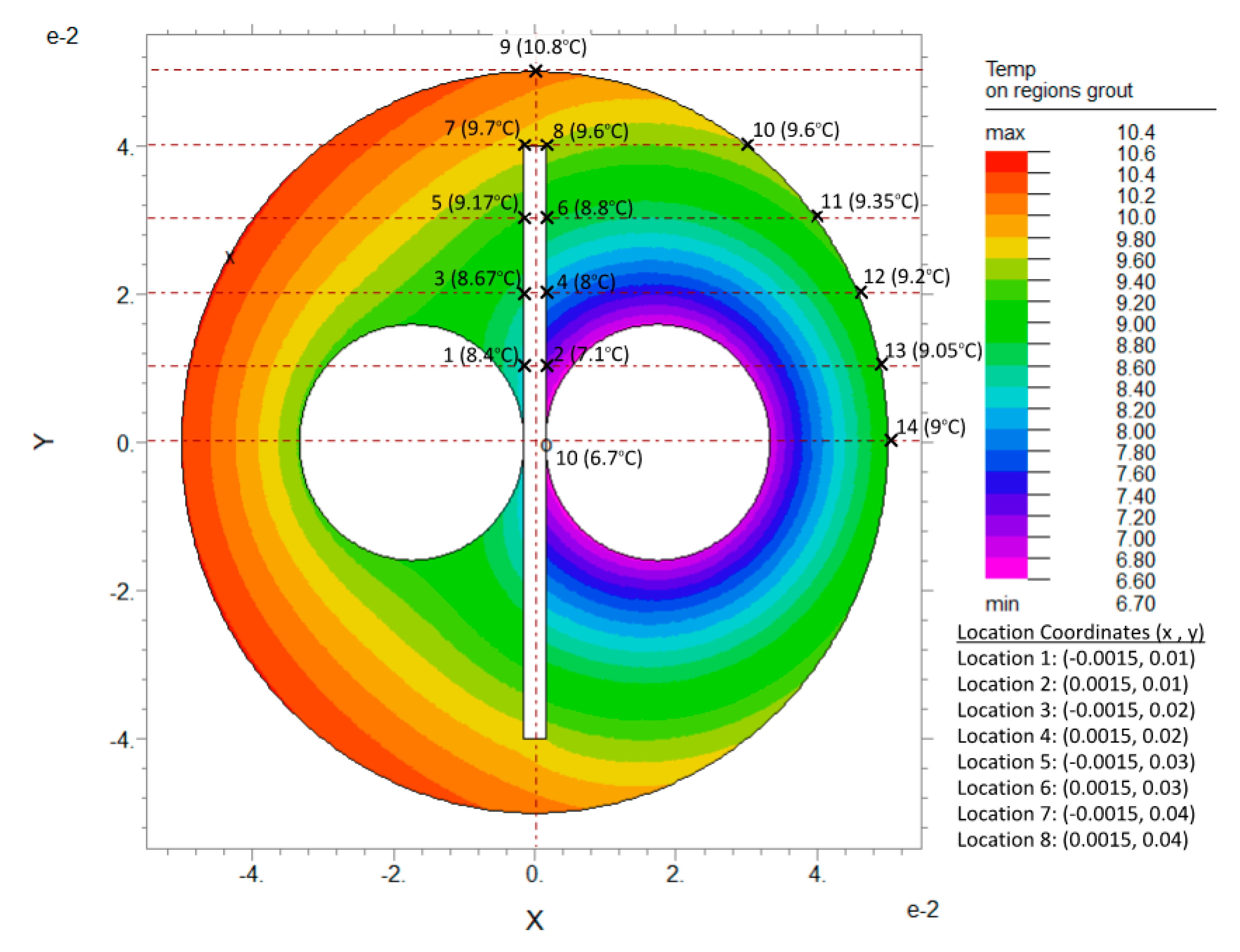

2.4. Analysis for Insulated Outlet Leg in a Conventional U-Tube Arrangement:

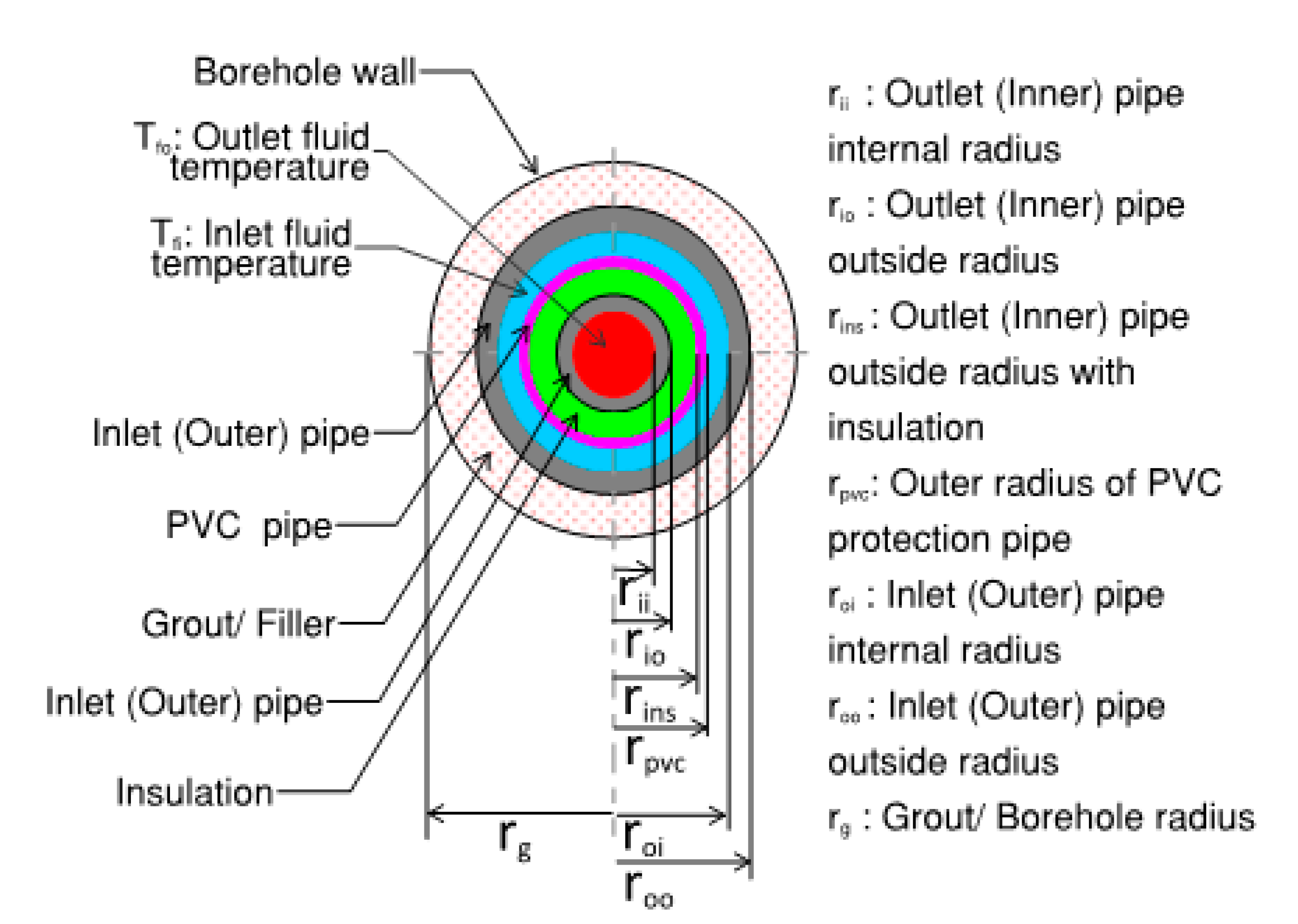

2.5. Analysis for Coaxial Pipe Arrangement:

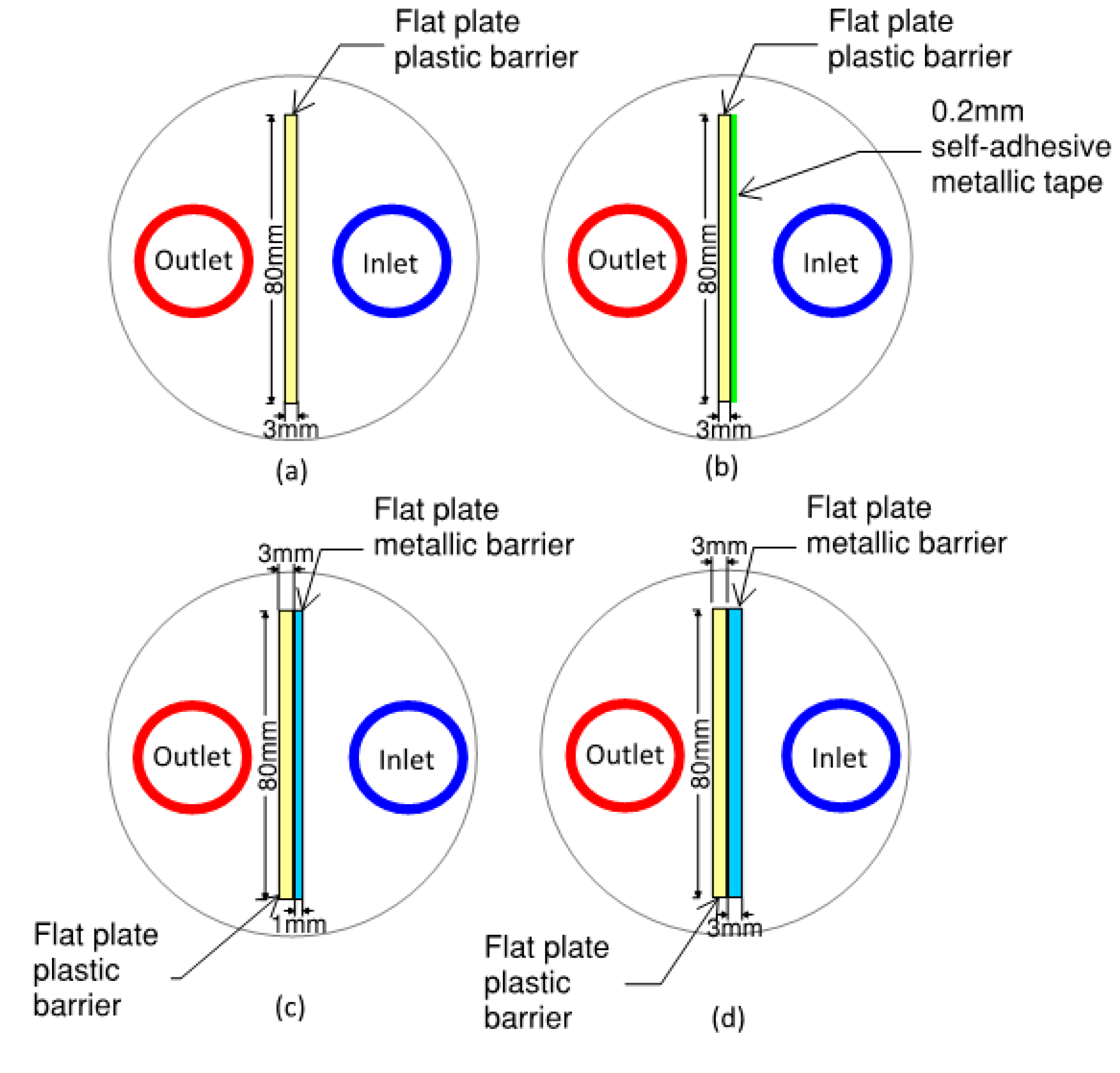

2.6. Analysis for Flat Plate Barrier Arrangement between the Inlet & Outlet Legs of The U-Tube:

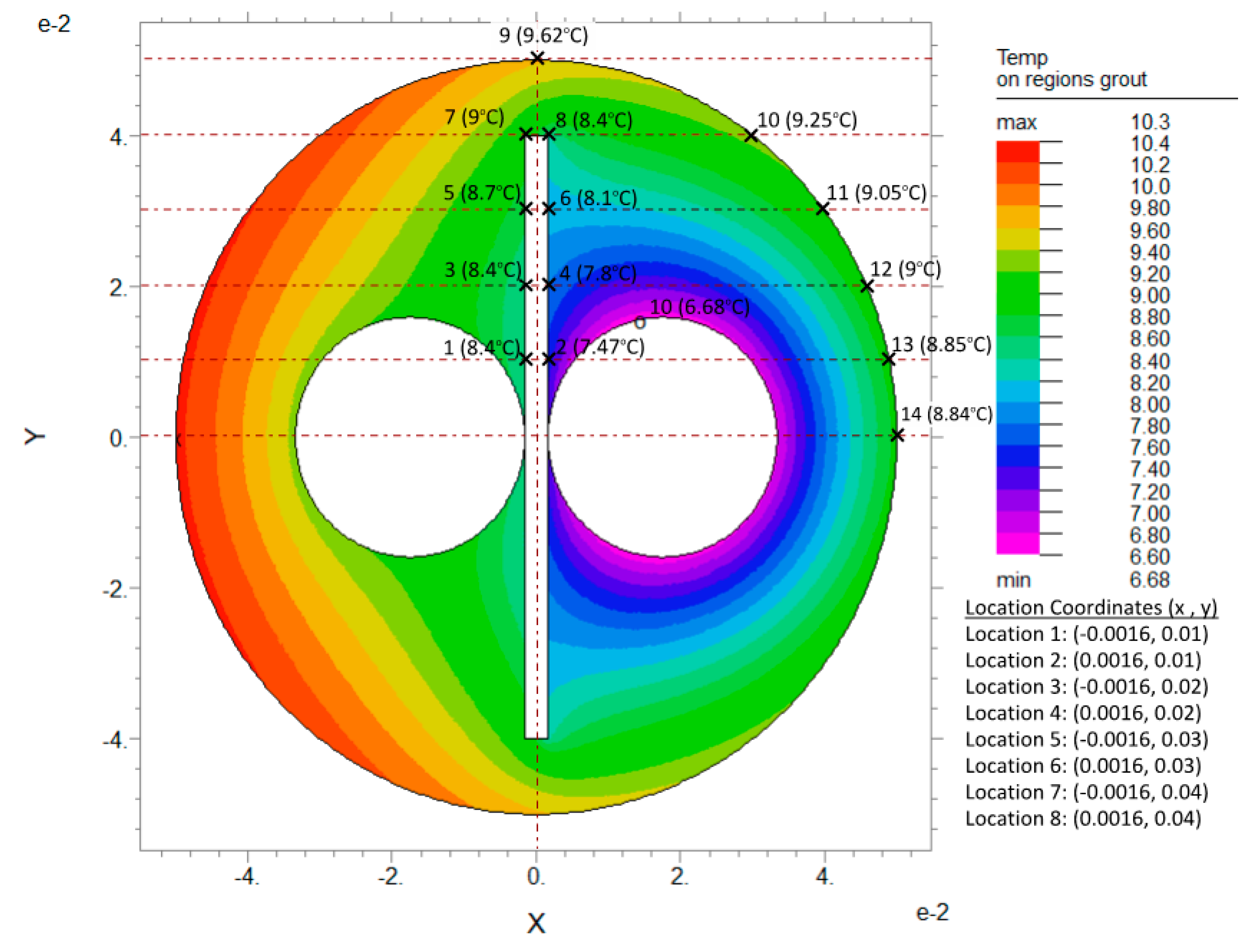

2.6.1. Flat plate Plastic Barrier:

- Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL1: 3mm flat plate shape plastic barrier of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K. This may be an unplasticized polyvinyl chloride pipe (uPVC) material which is commonly available [54].

- Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL2: 3mm flat plate shape plastic barrier of thermal conductivity 0.5 W/m.K. This may be a specialized rigid plastic material [55].

- Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL3: 3mm flat plate shape plastic barrier of thermal conductivity 2 W/m.K. This may be a specialized rigid plastic material [55].

2.6.2. Flat Plate Plastic Barrier with Metallic Tape:

2.6.3. Flat Plate Metallic Barrier:

2.6.4. Flat Plate Double Barrier:

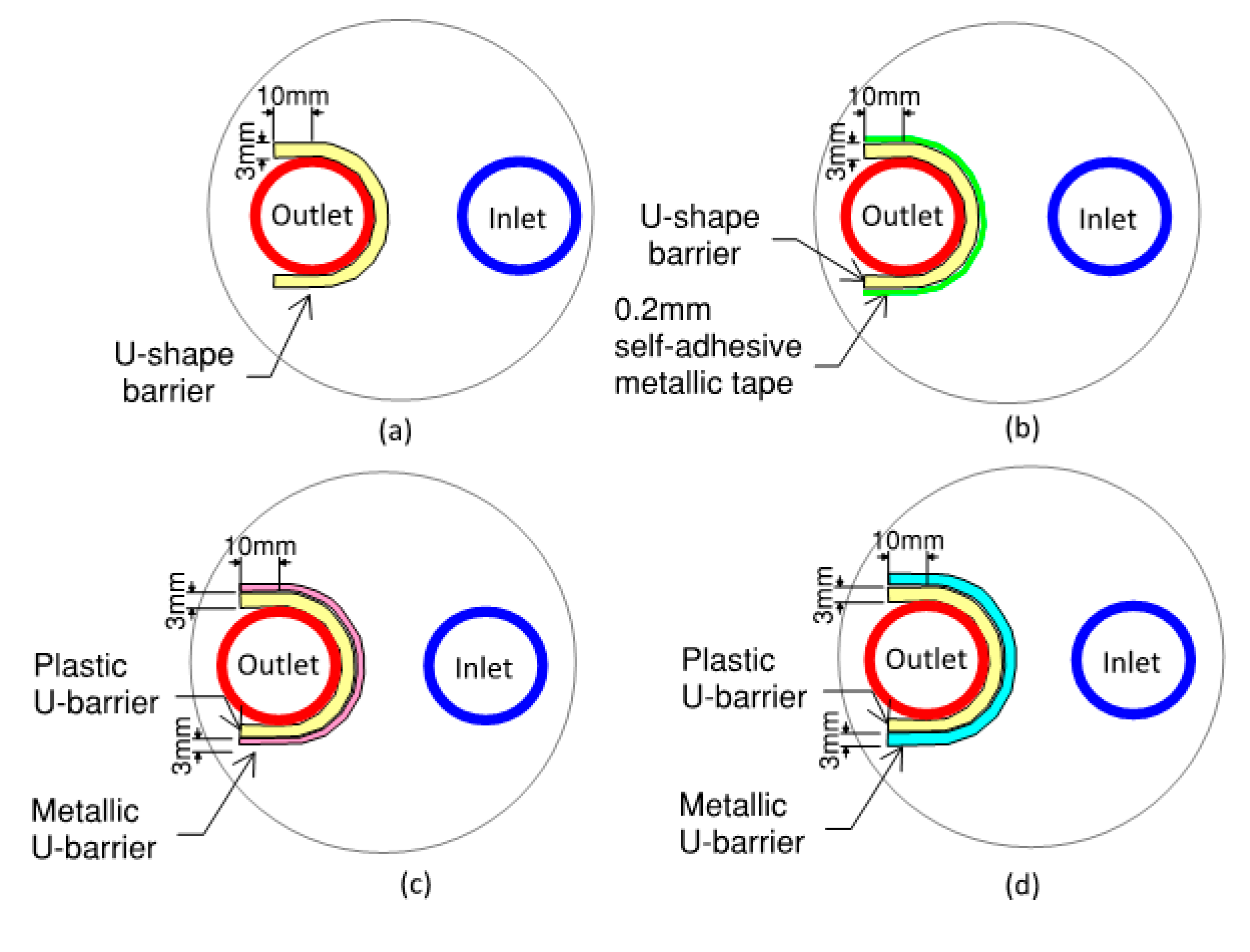

2.7. Analysis of U Shape Barrier Arrangement between the Inlet & OUTLET legs:

3. Results

3.2. Analysis for U-Tube BHX Having Insulated Outlet Leg:

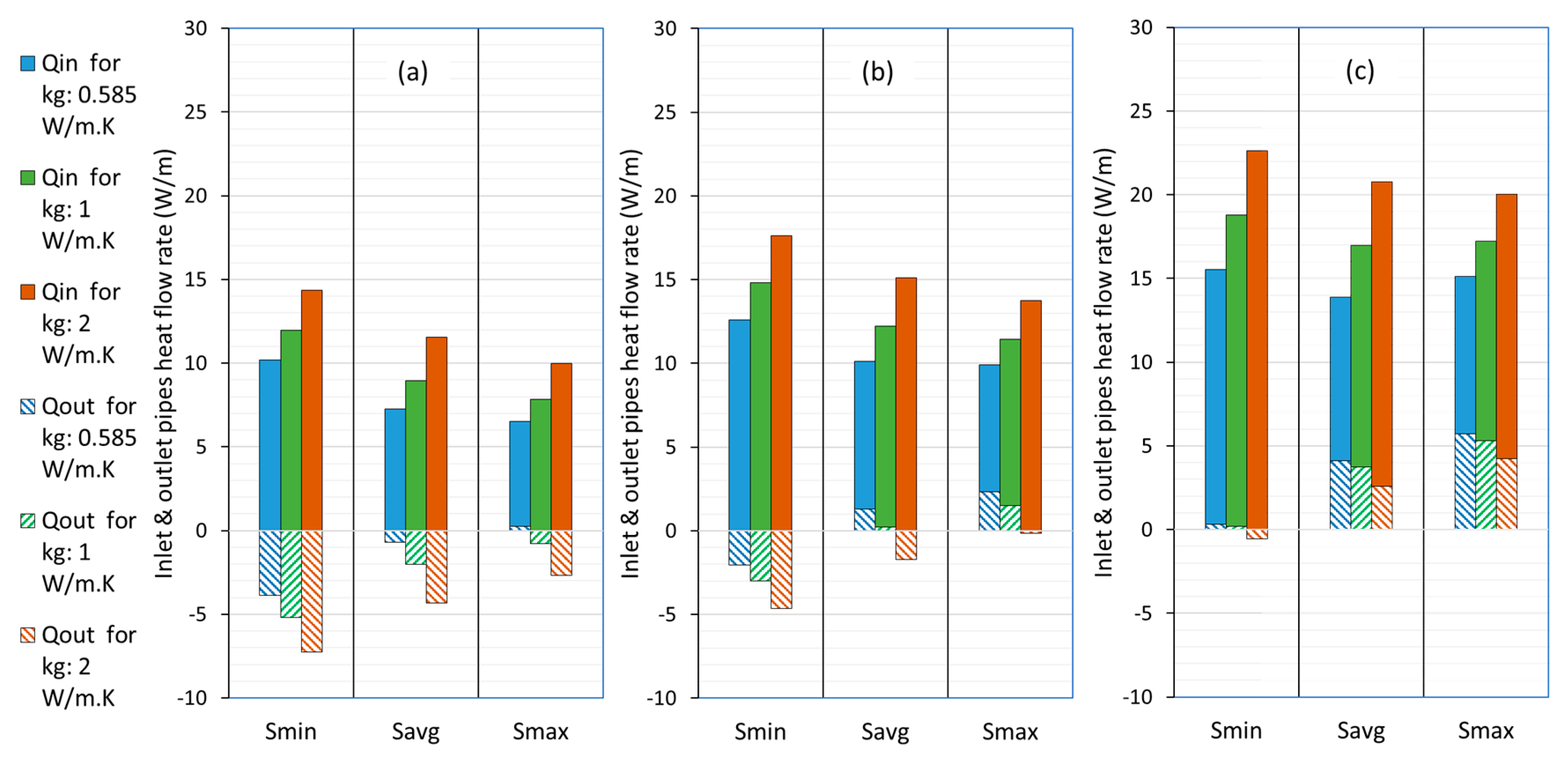

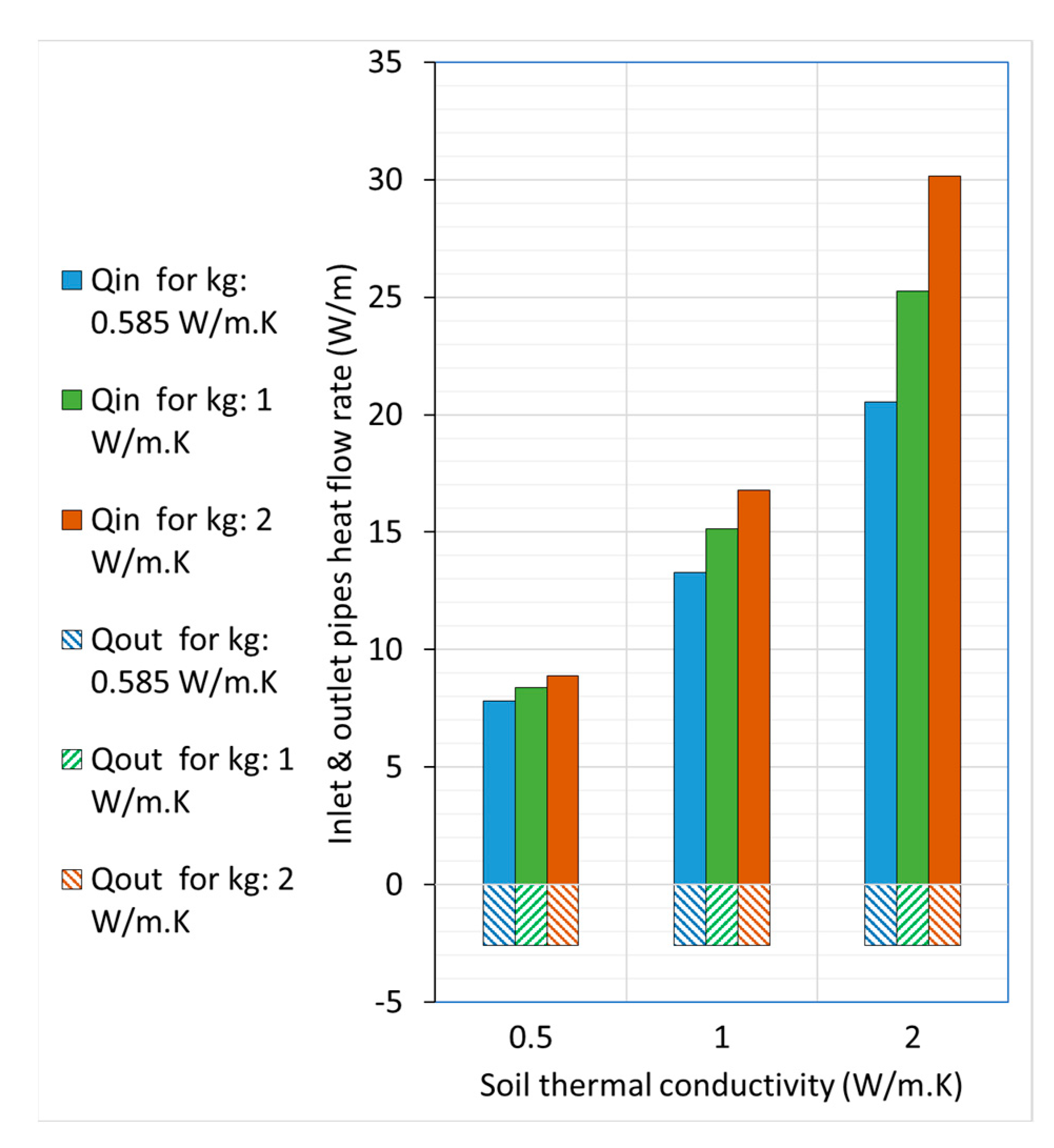

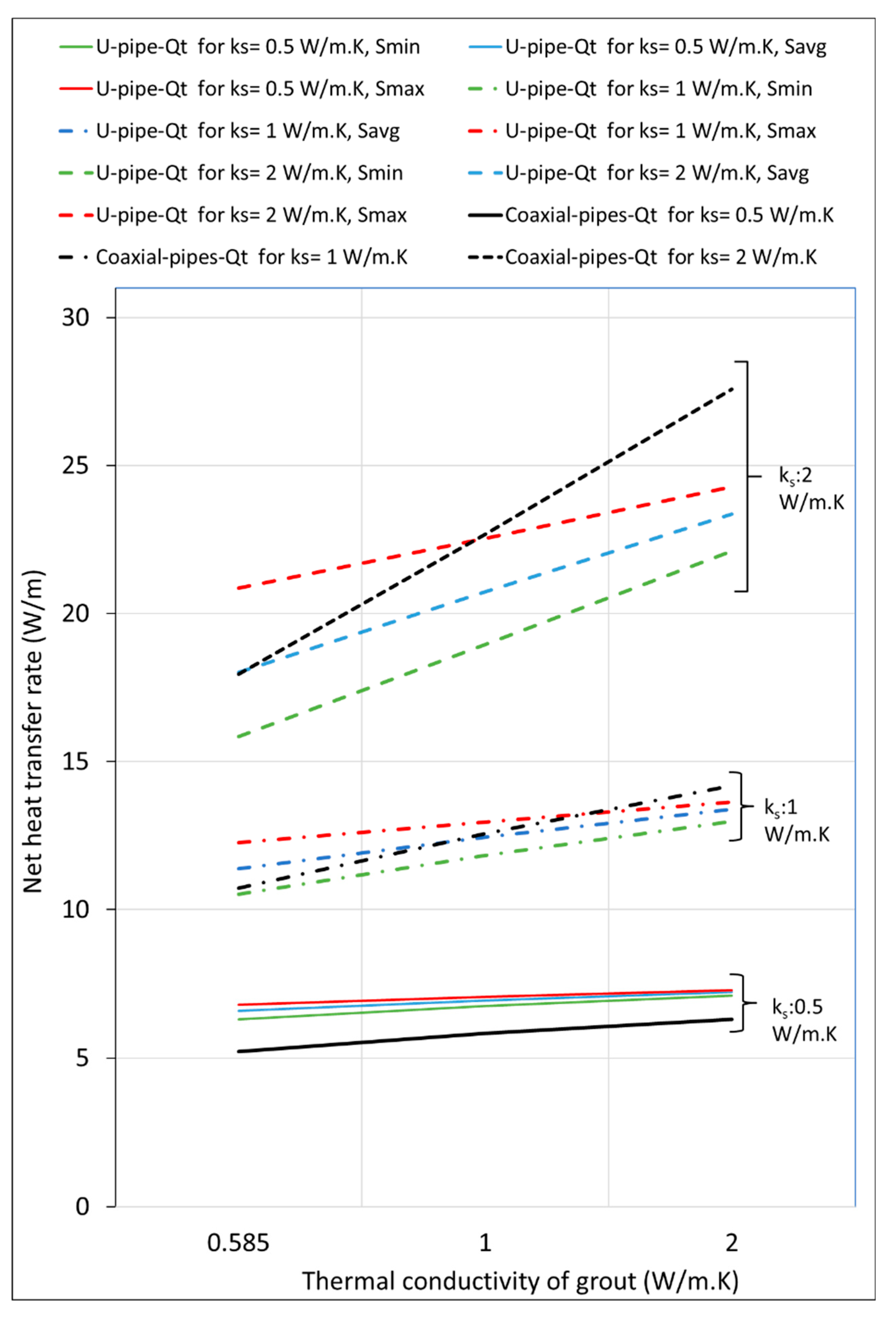

3.3. Analysis for Coaxial Pipes:

3.4. Single Flat Plate Barrier Arrangement for U-Tube BHX:

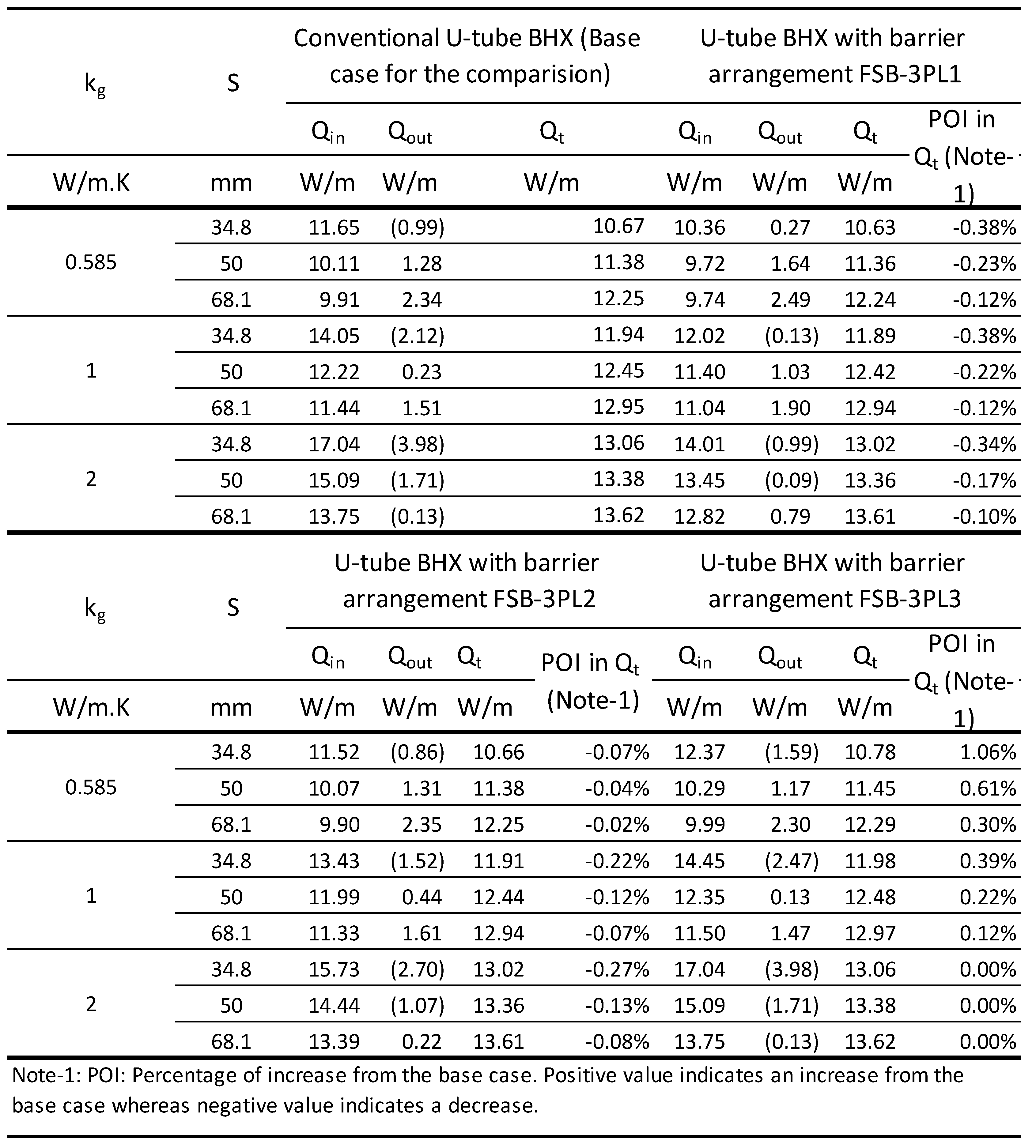

3.4.1. Flat Plate Plastic Barrier:

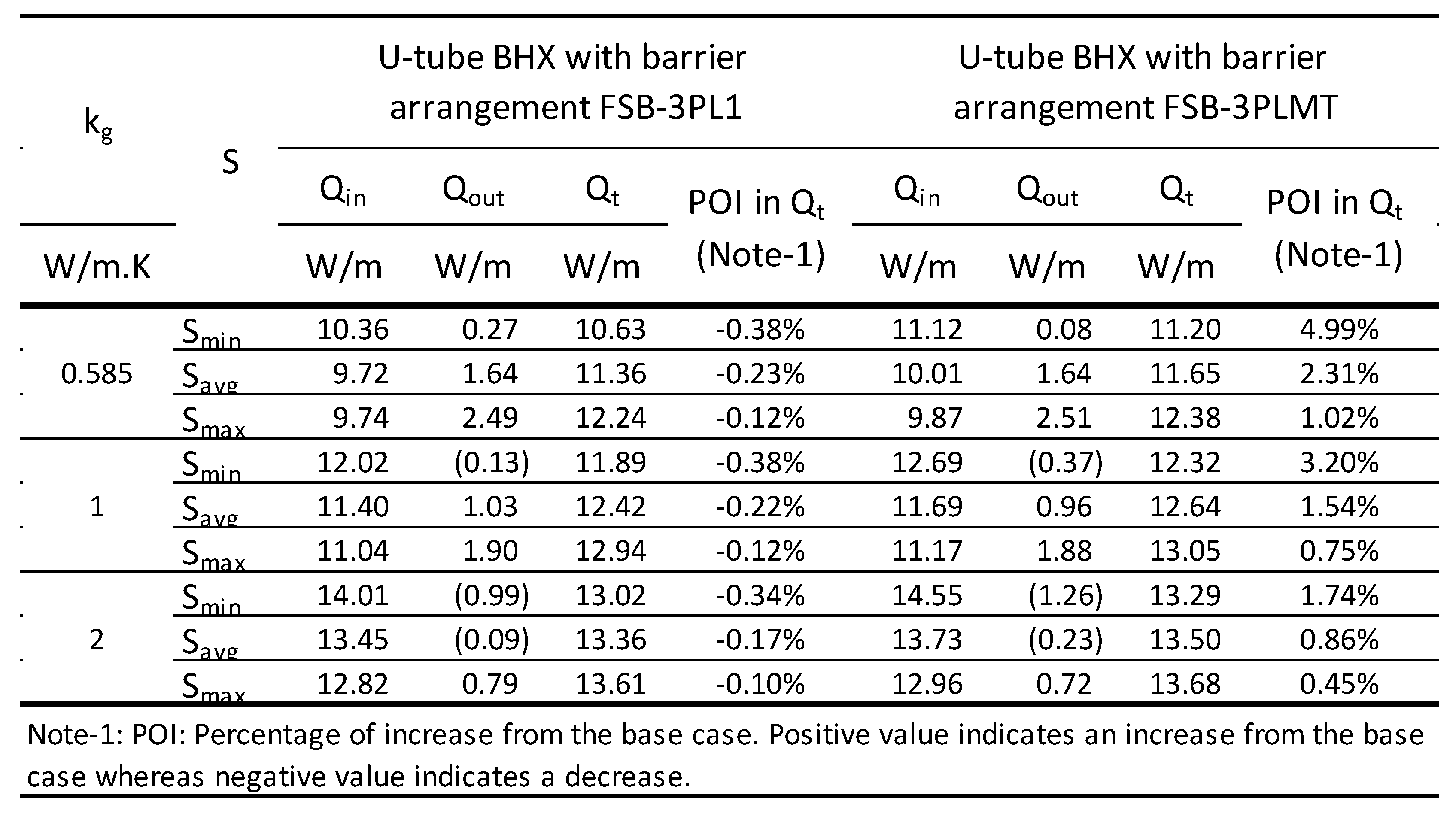

3.4.2. Flat Plate Plastic Barrier with self-Adhesive Metallic Tape:

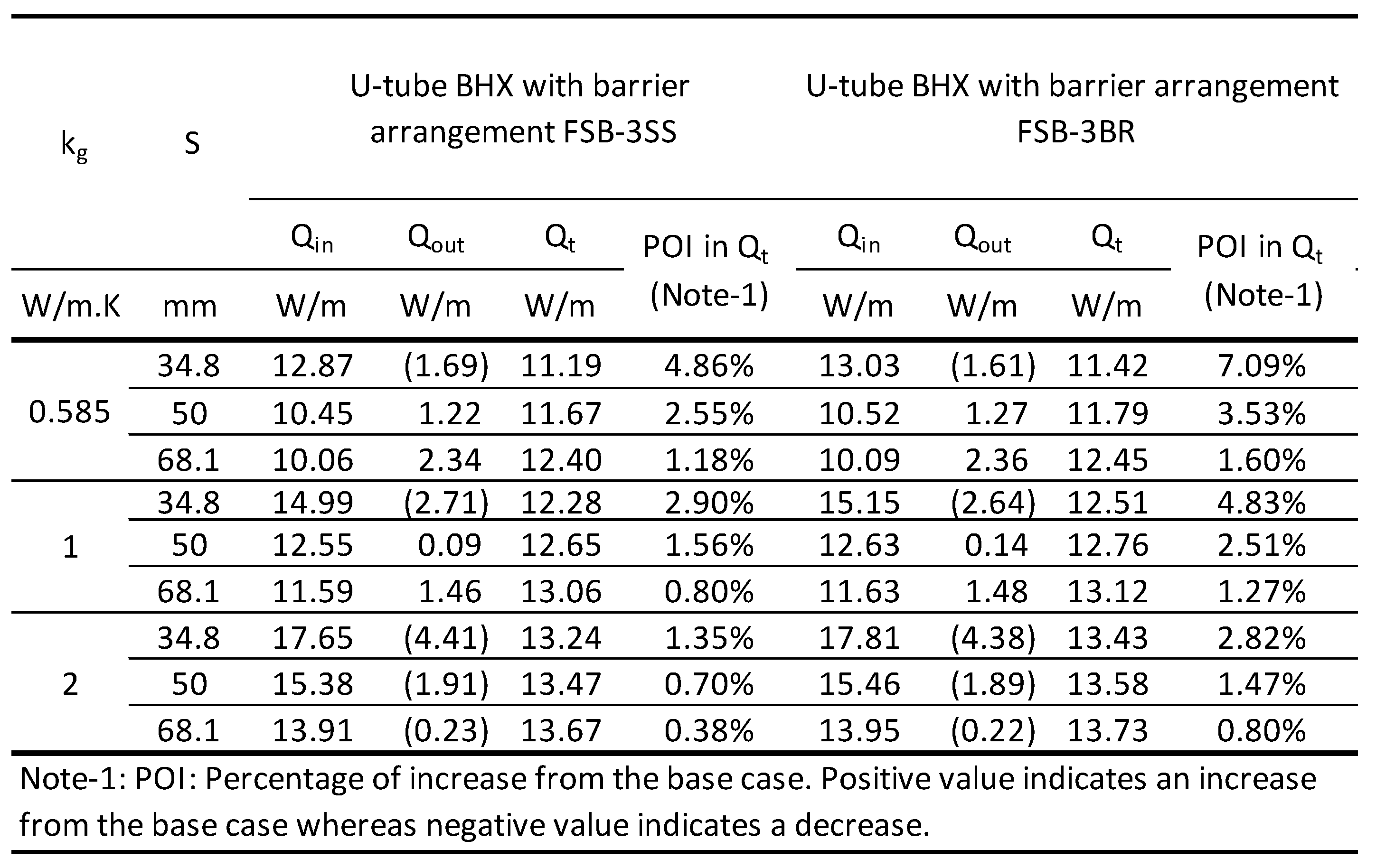

3.4.3. Flat plate Metallic Barrier:

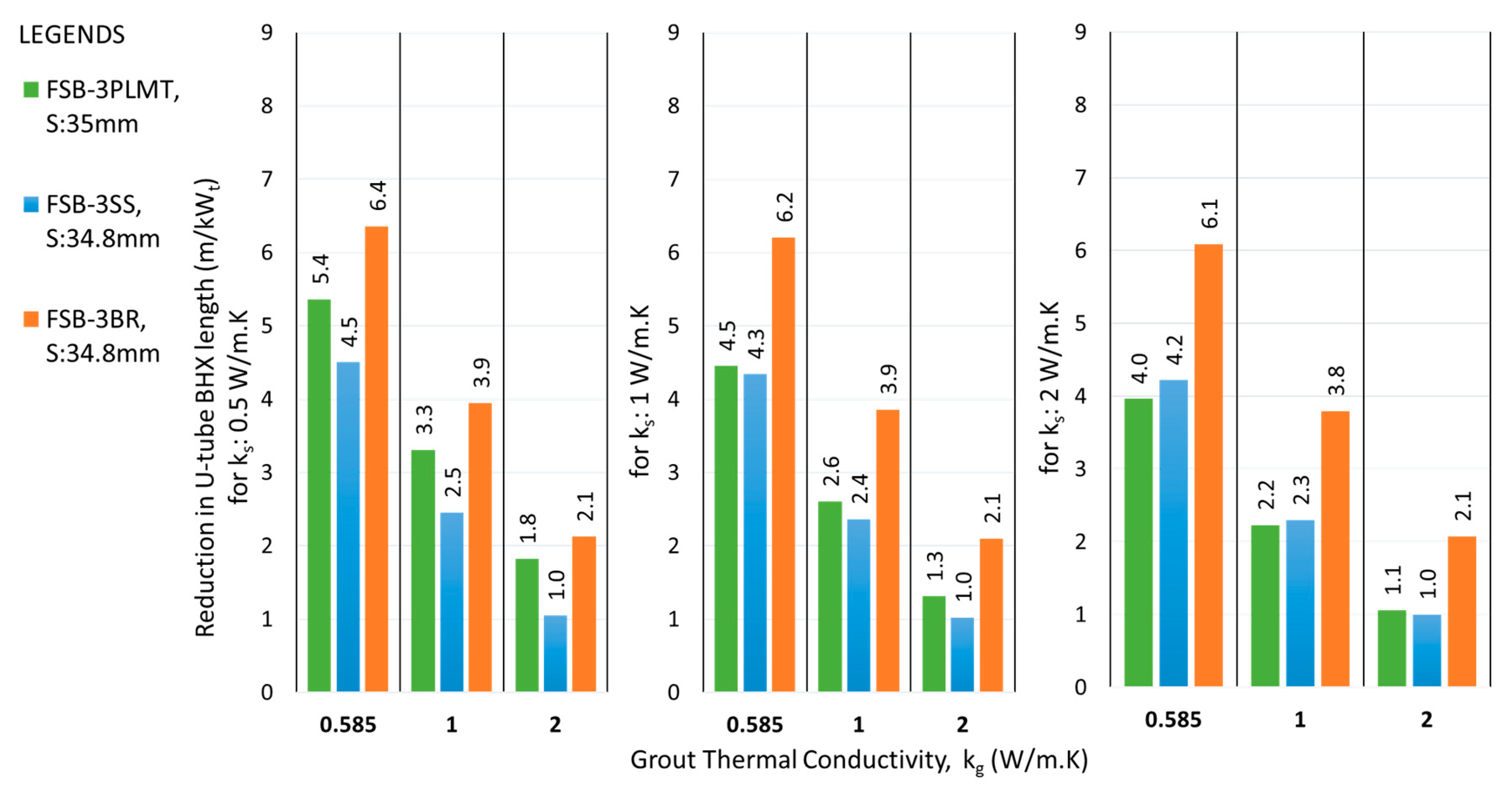

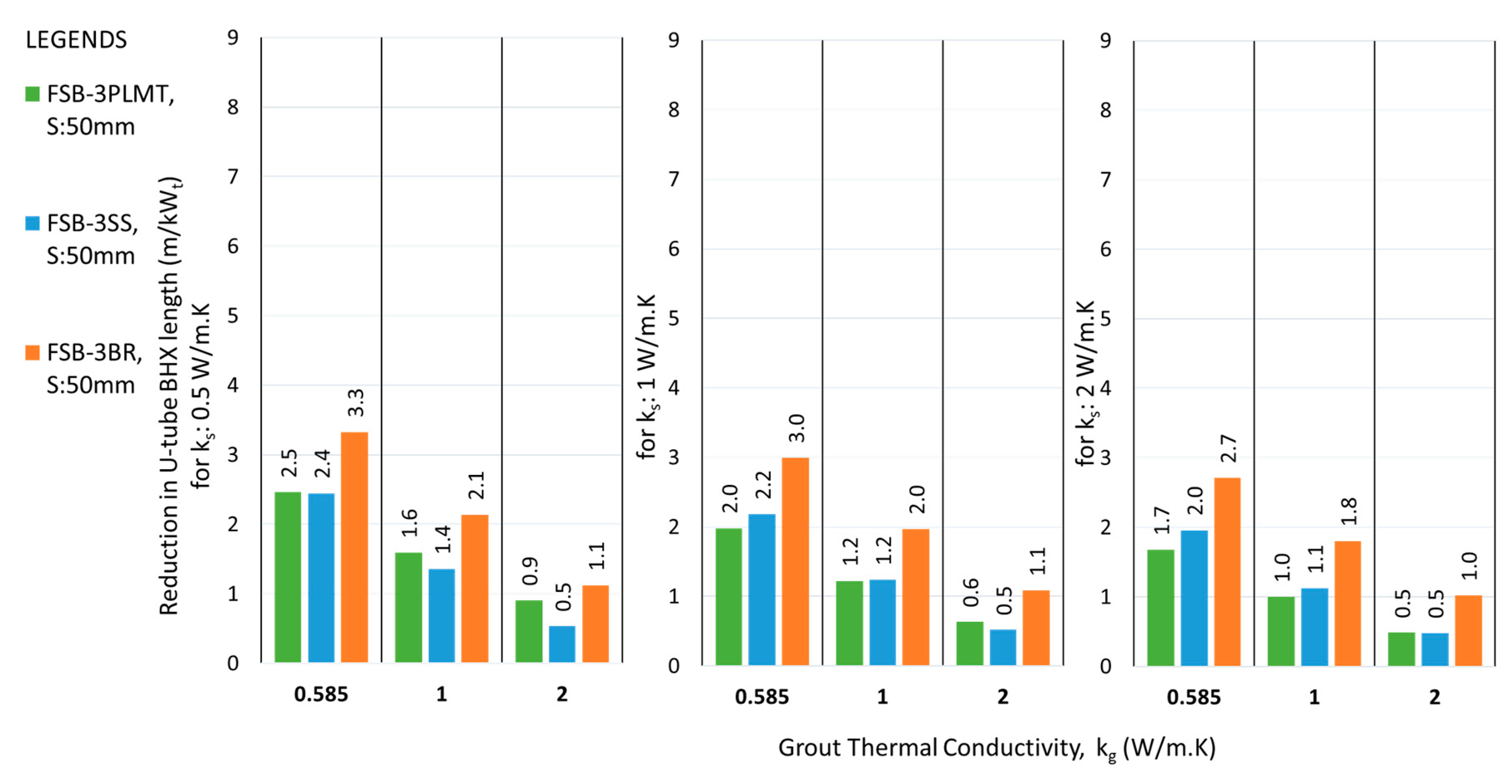

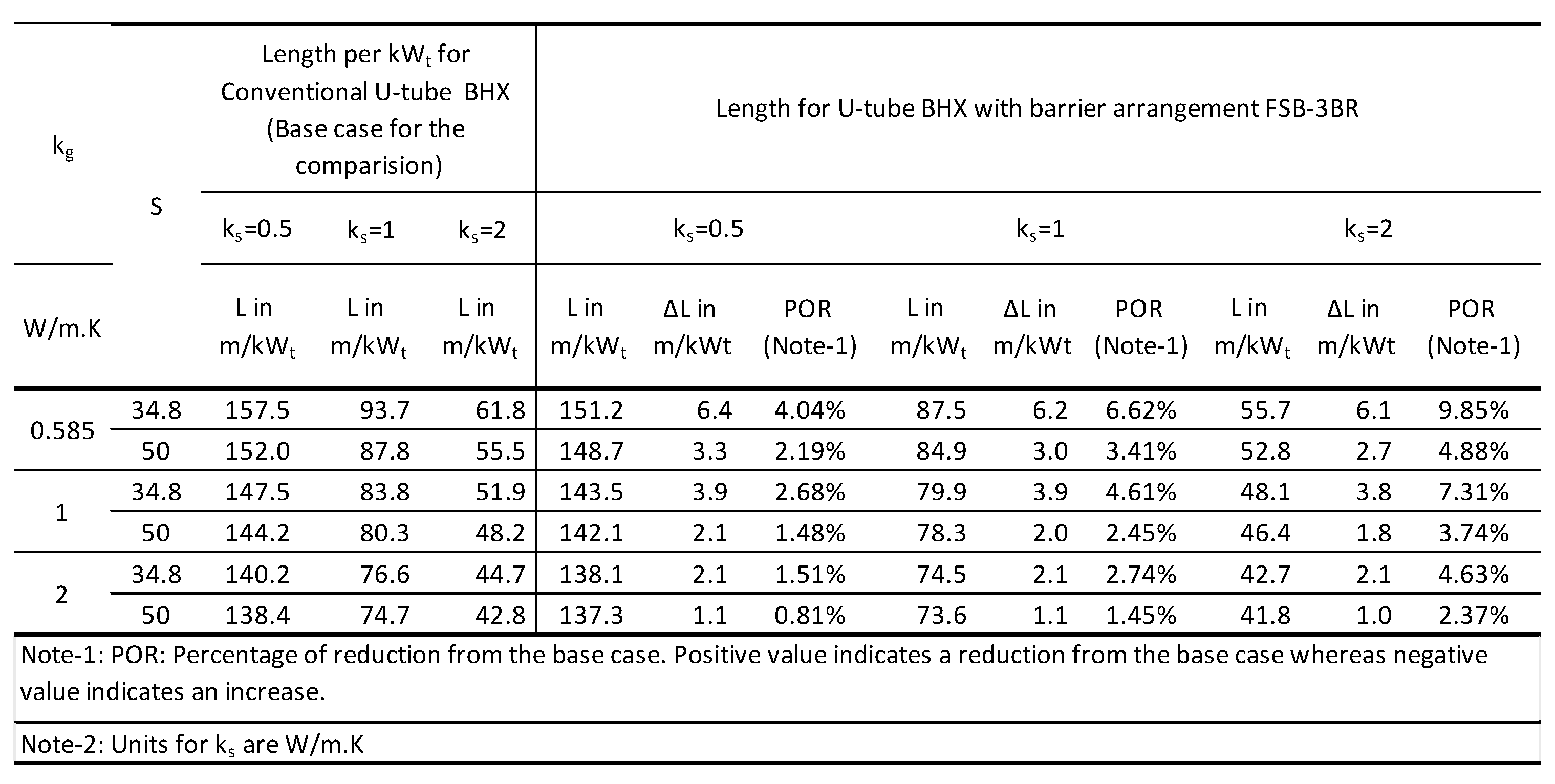

3.4.4. Impact of Single Flat Plate Barrier on BHX Length:

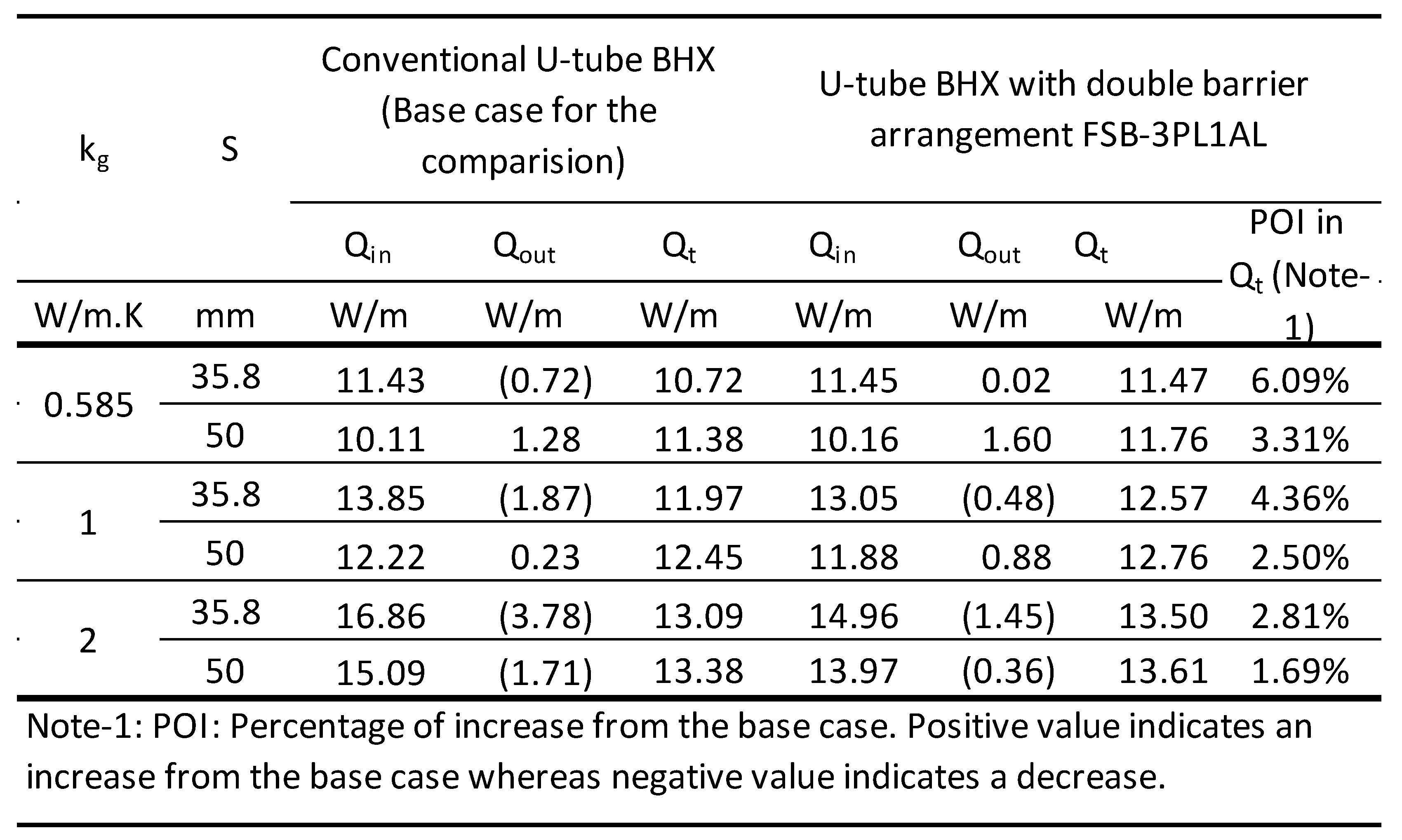

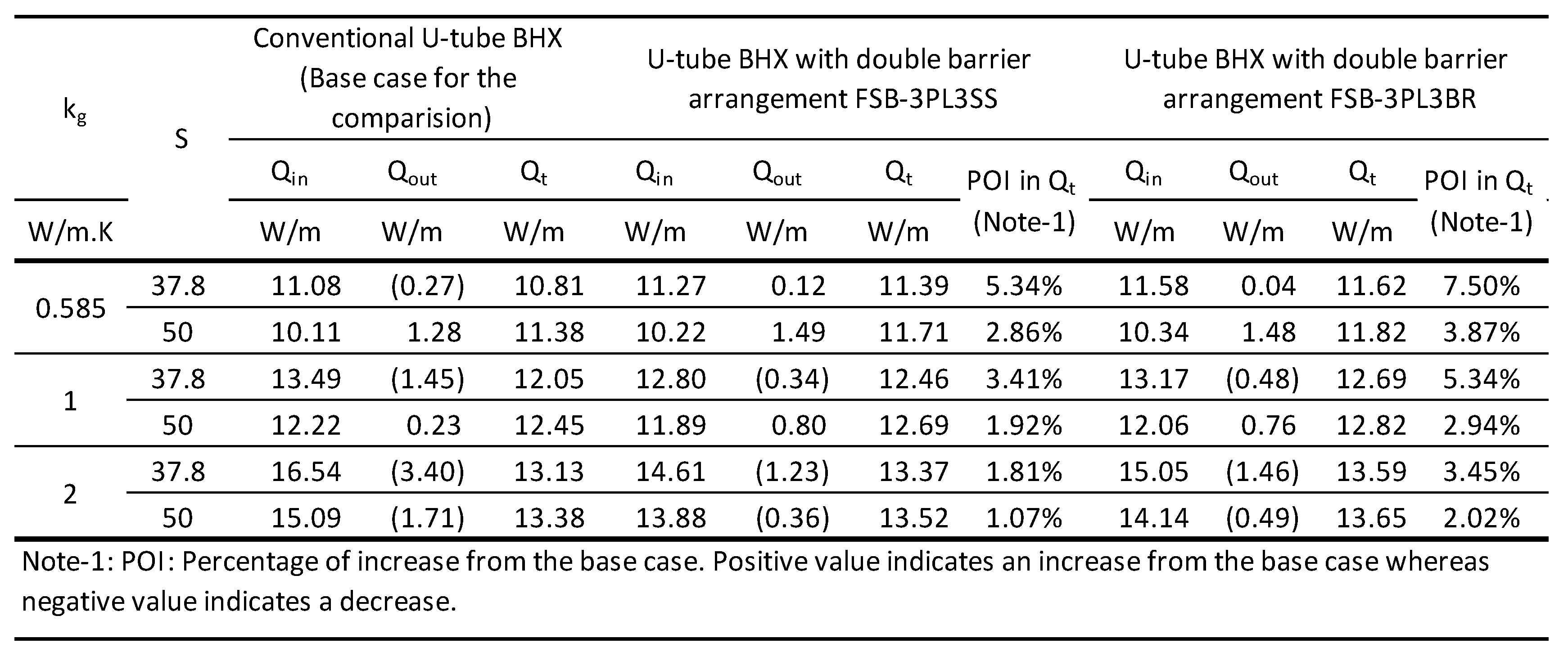

3.5. Double Flat Plate Barrier Arrangement for U-Tube BHX:

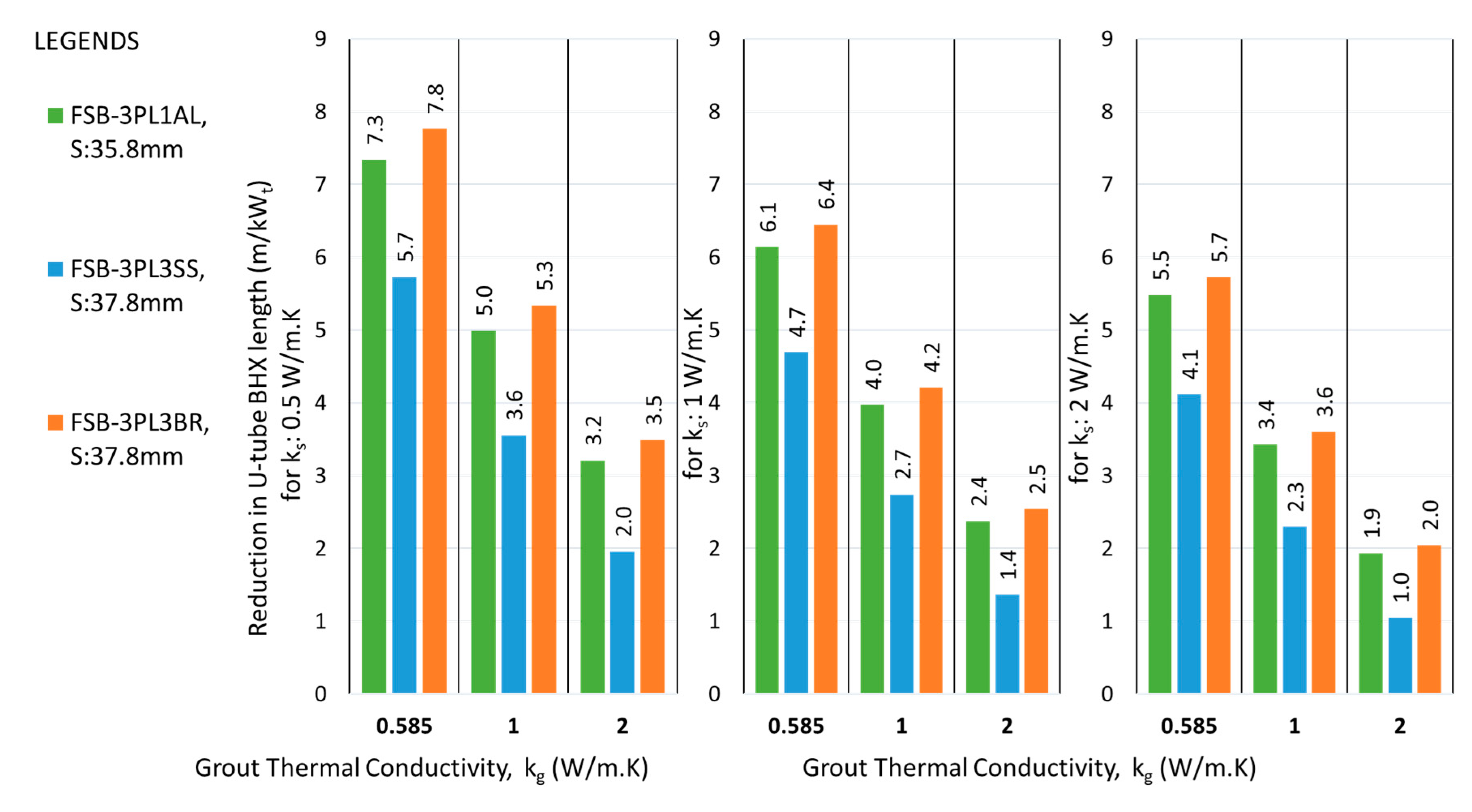

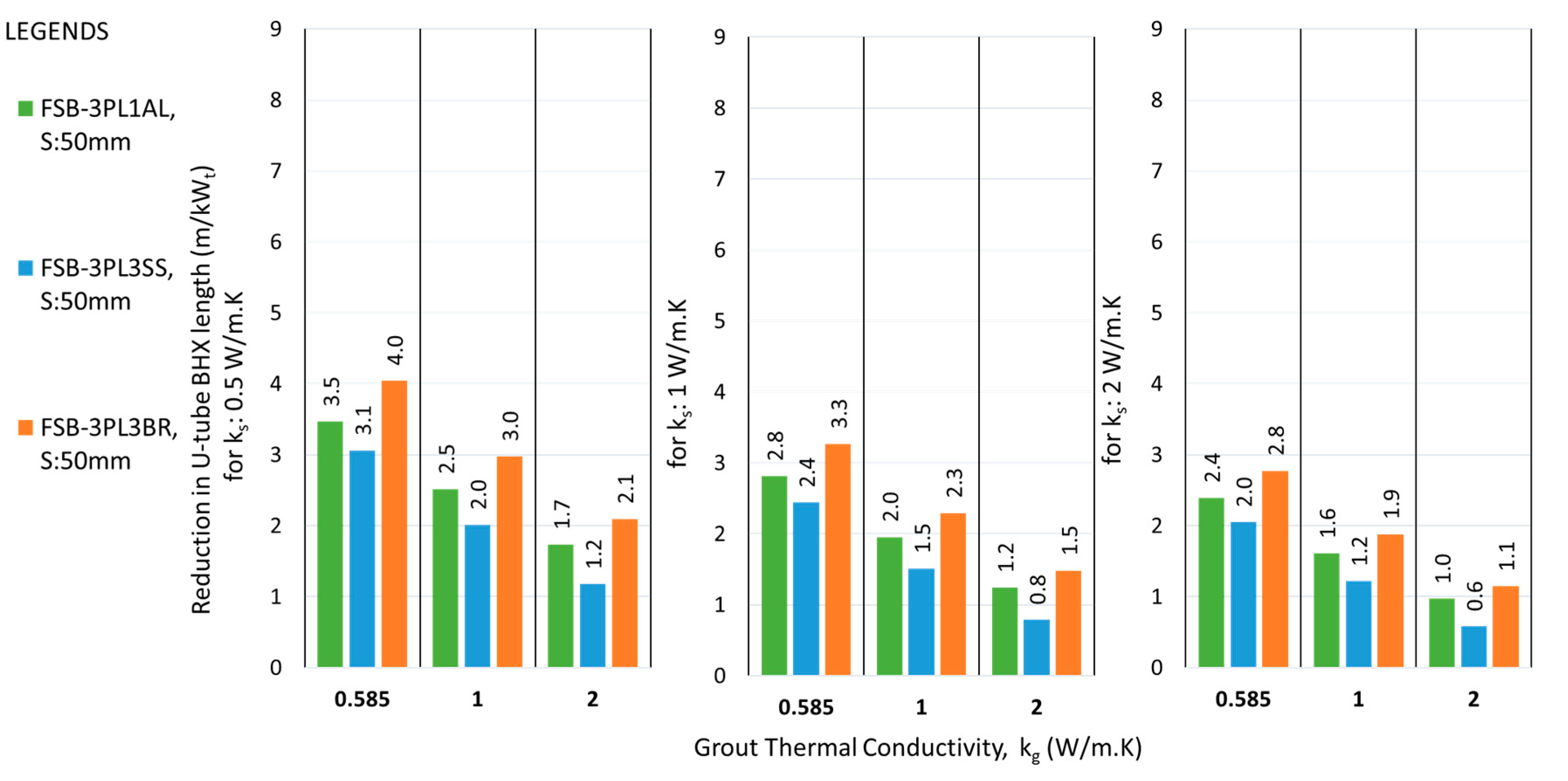

3.5.3. Impact of Double Flat Plate Barrier on BHX Length:

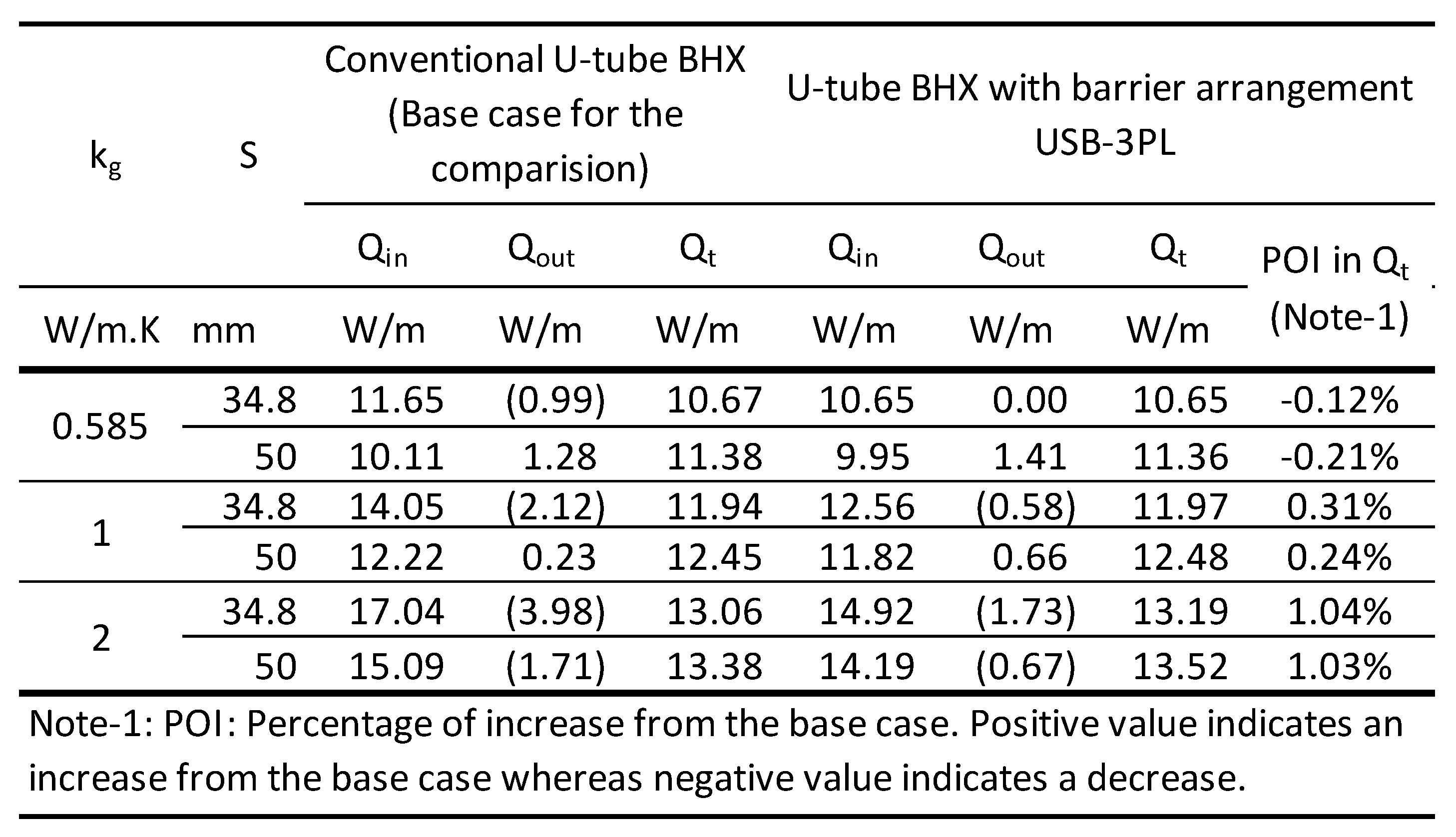

3.6.1. U-Shape Plastic Barrier:

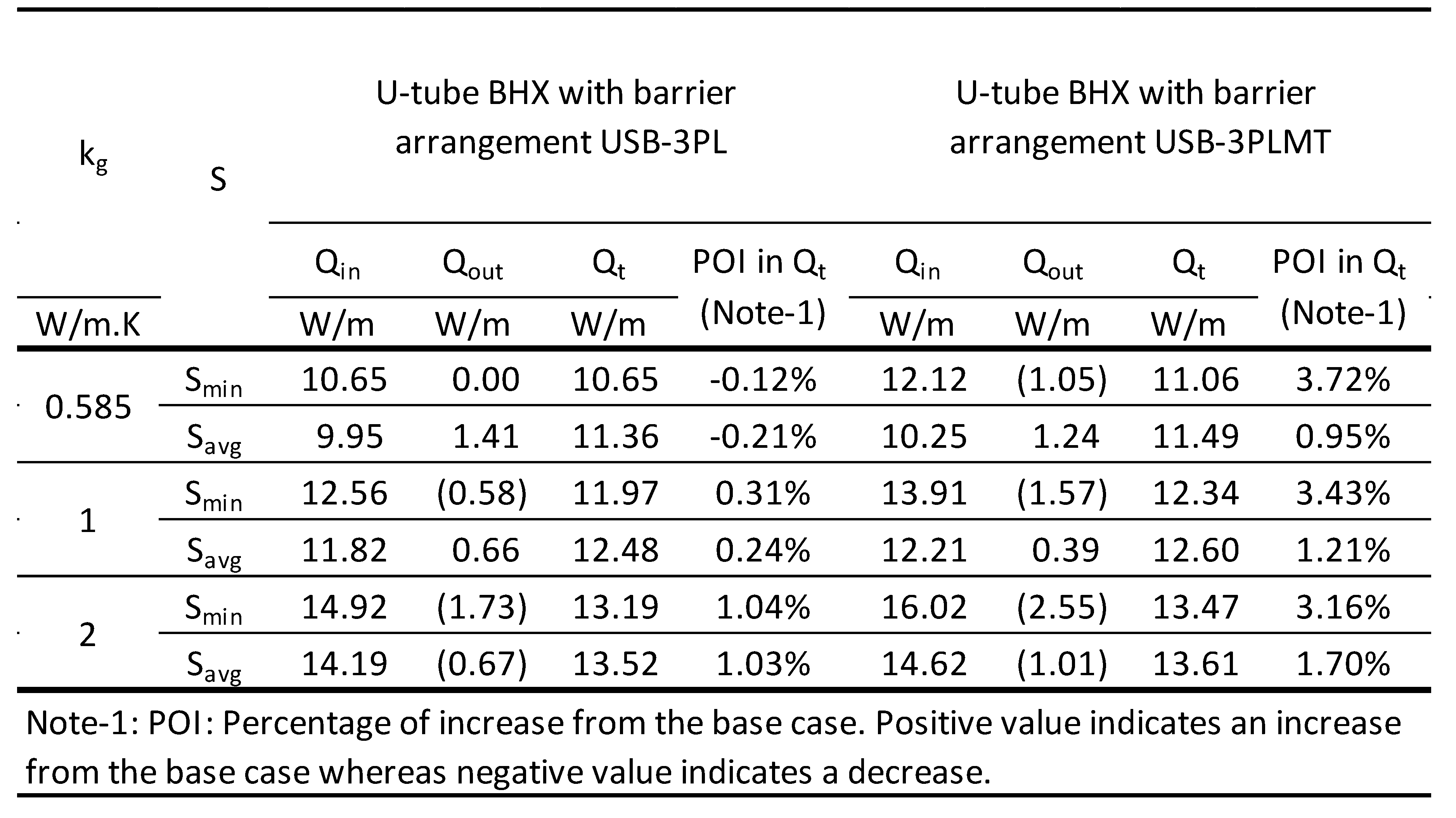

3.6.2. U-Shape Plastic Barrier with Self-Adhesive Metallic Tape:

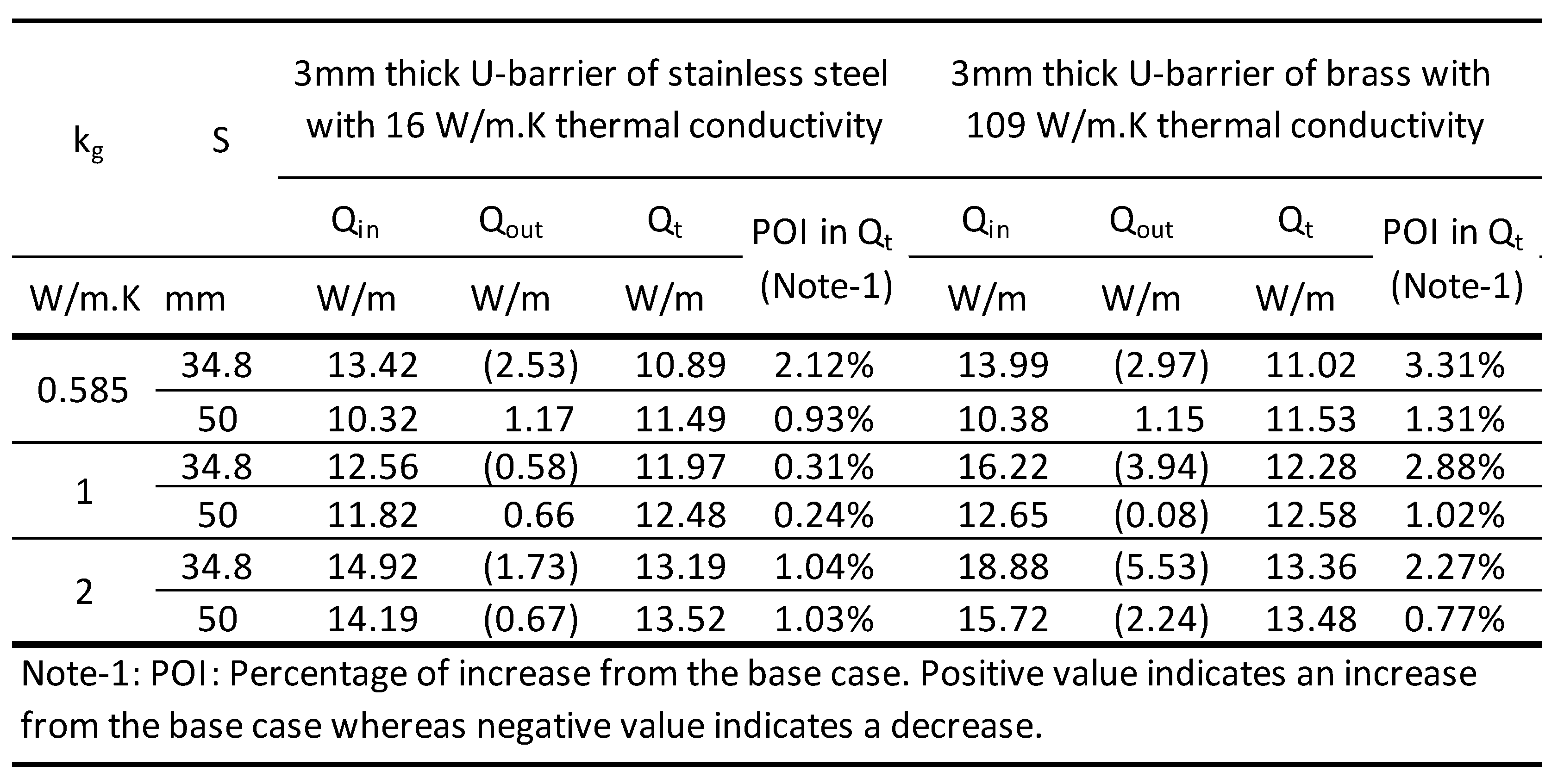

3.6.3. U-Shape Metallic Barrier:

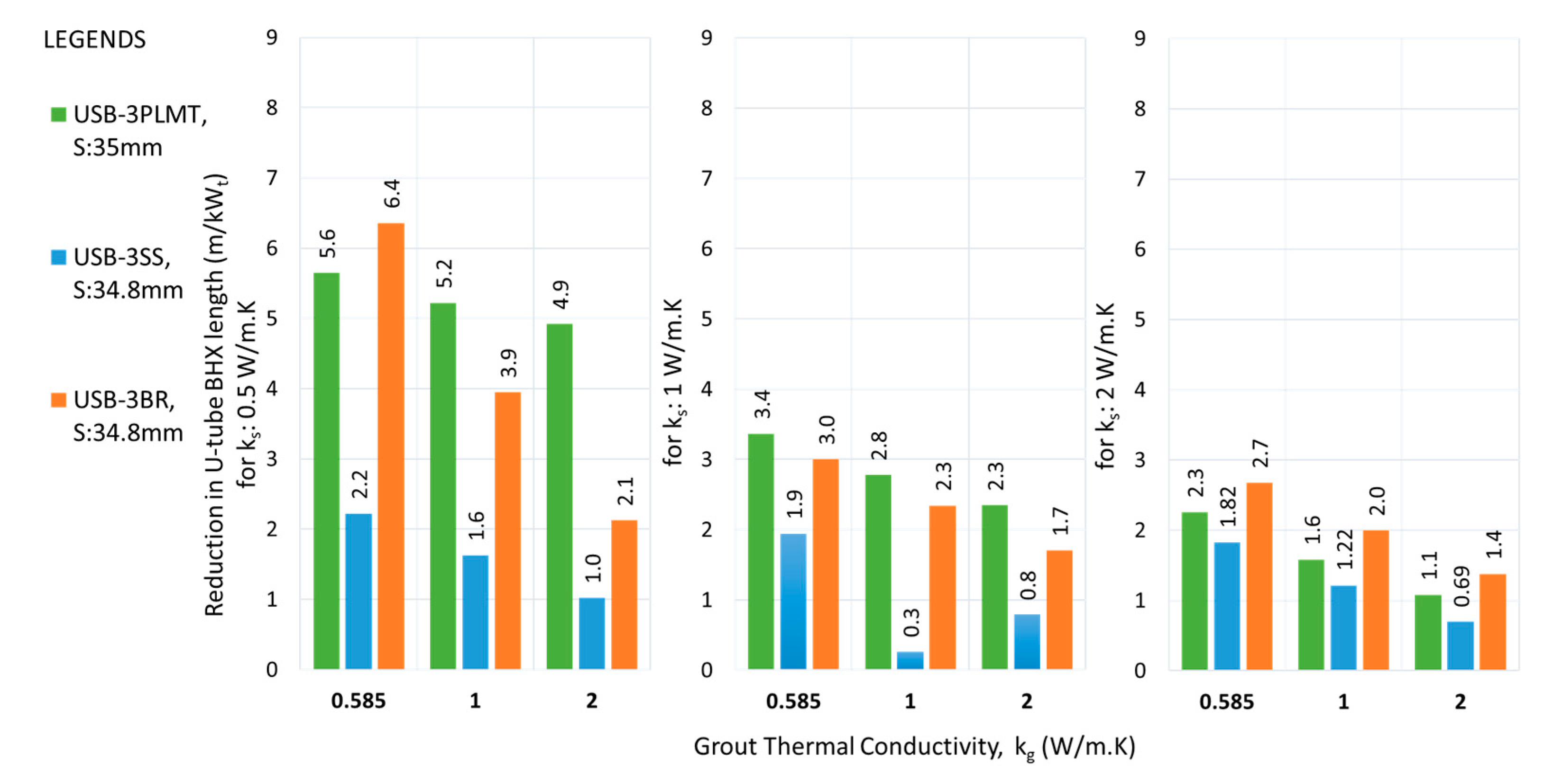

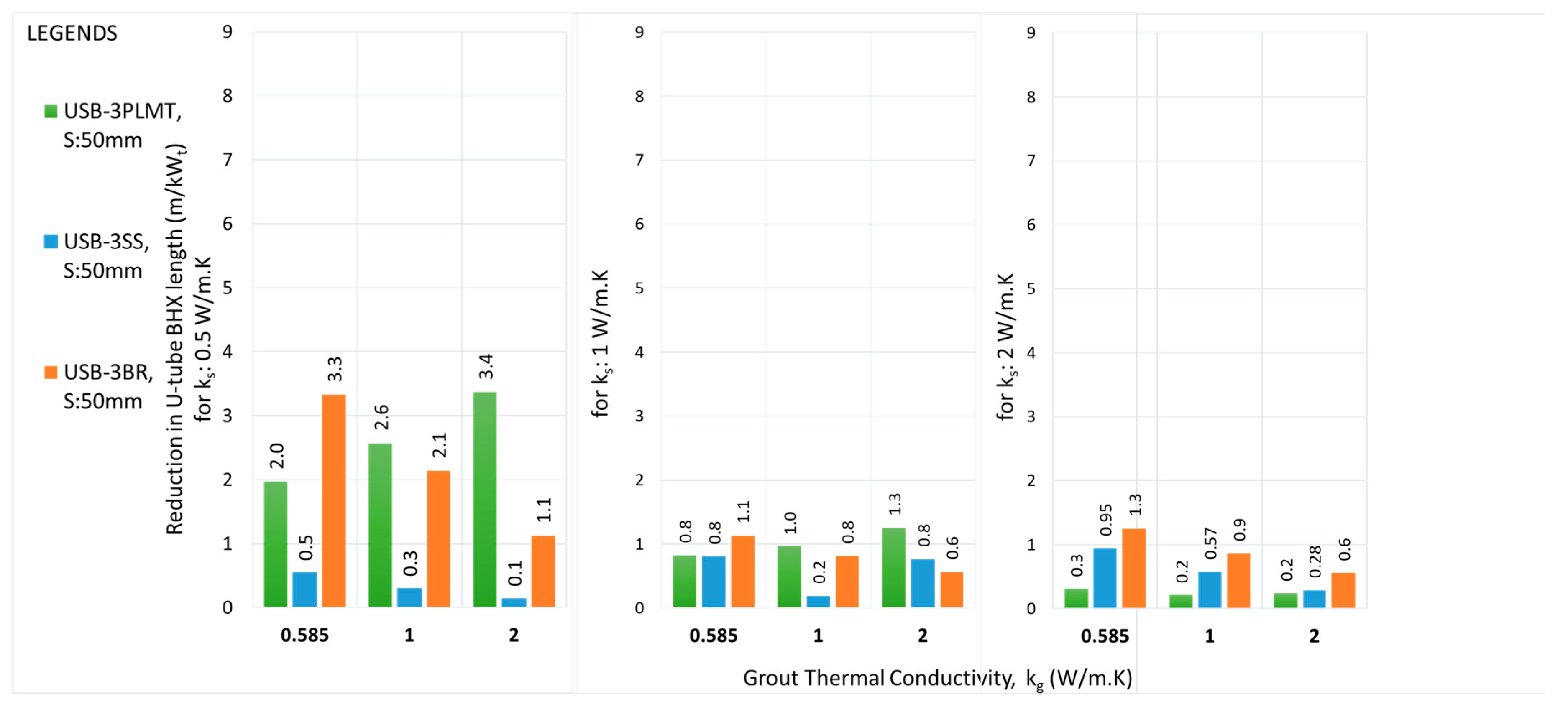

3.6.4. Impact of U-Shape Barrier on BHX Length:

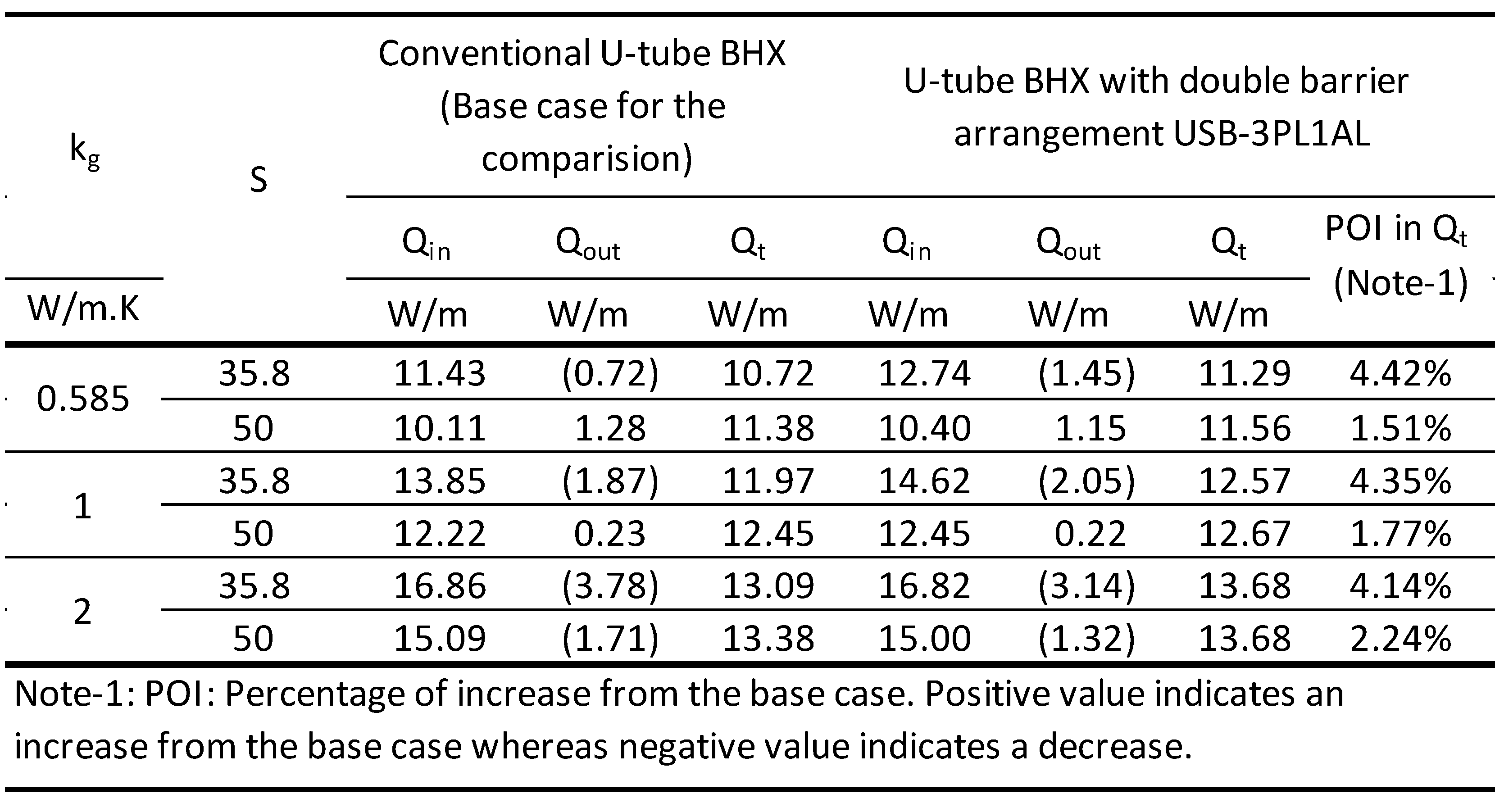

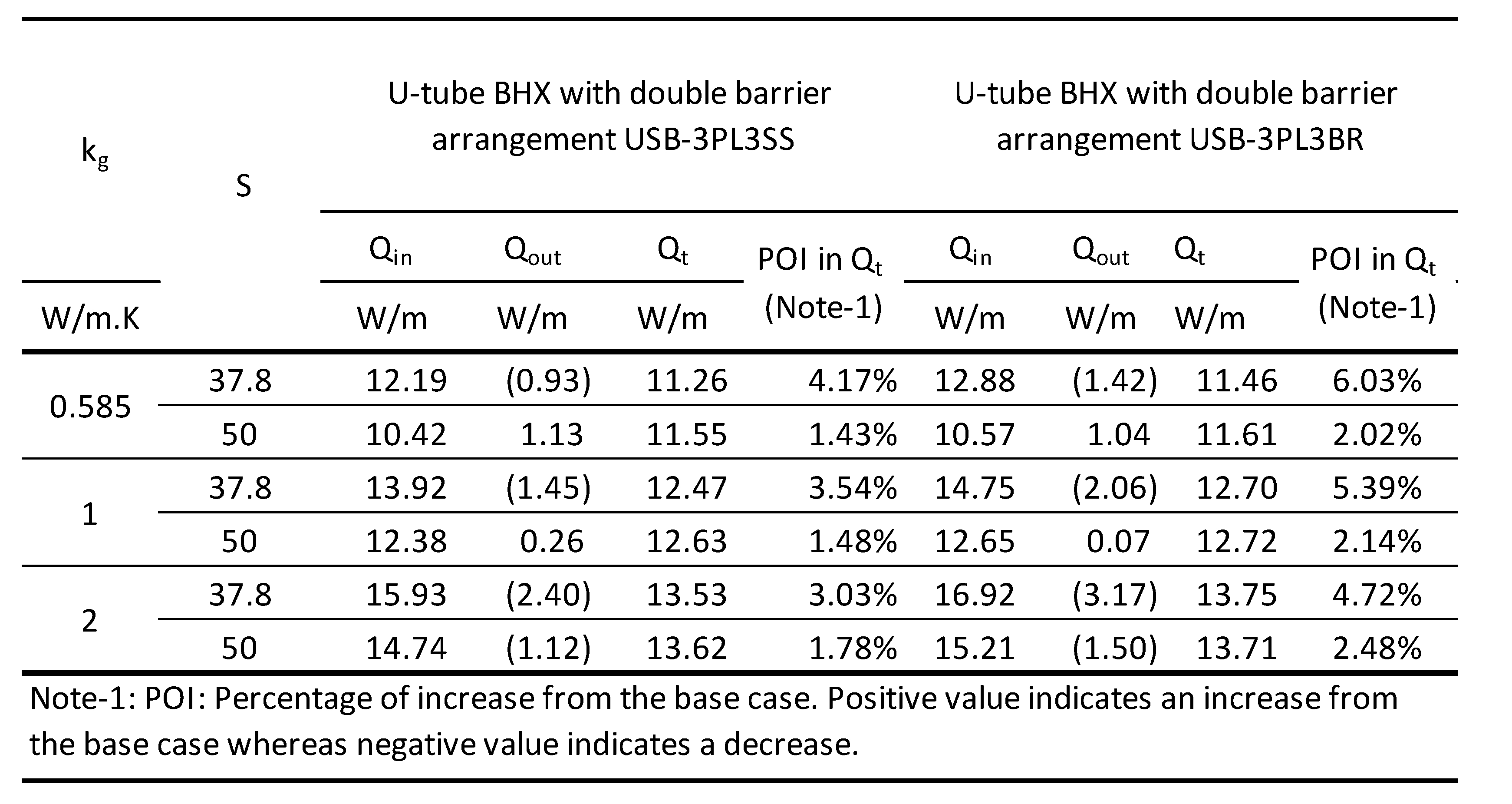

3.7. Double Flat Plate Barrier Arrangement for U-Tube BHX:

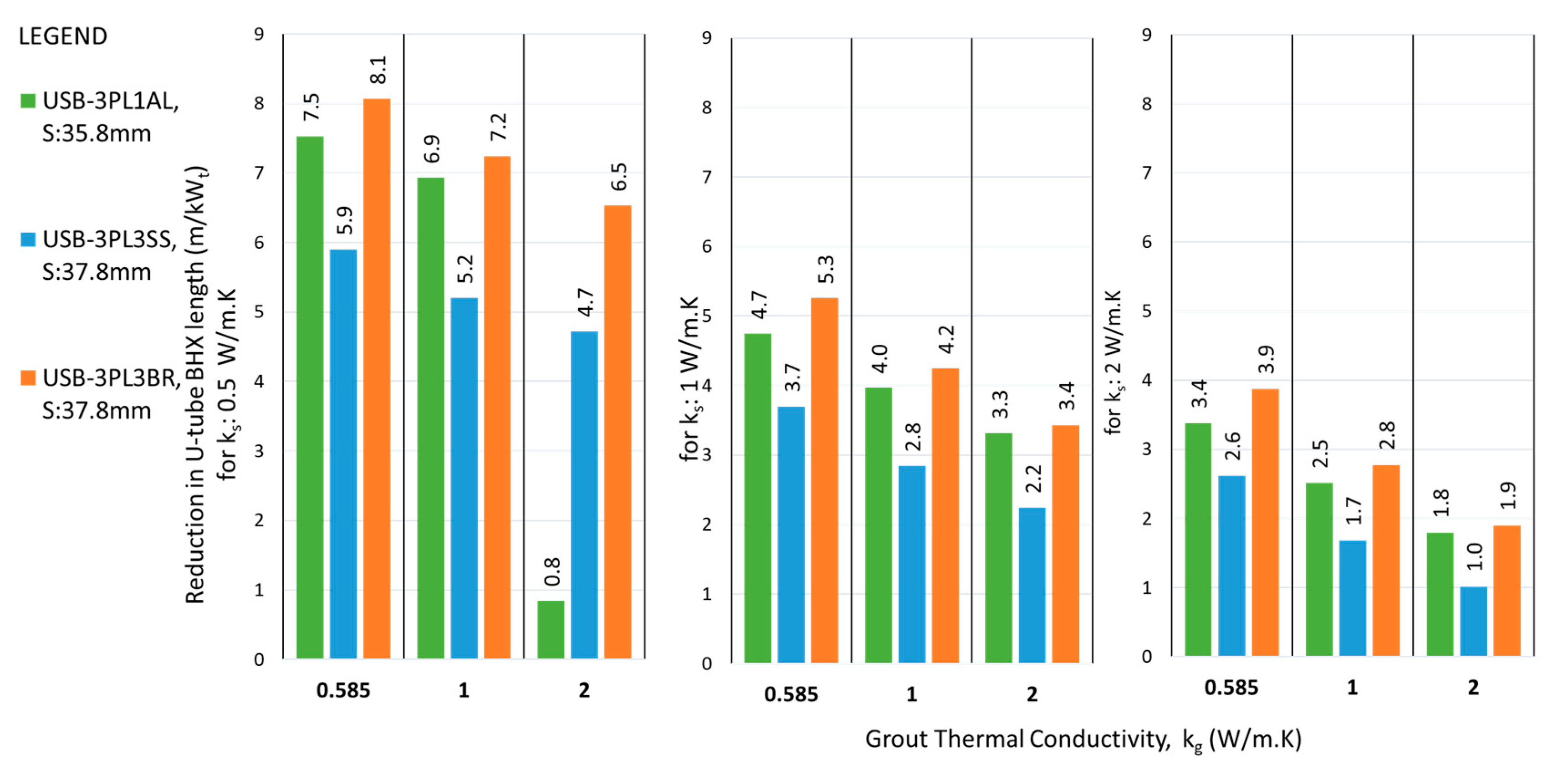

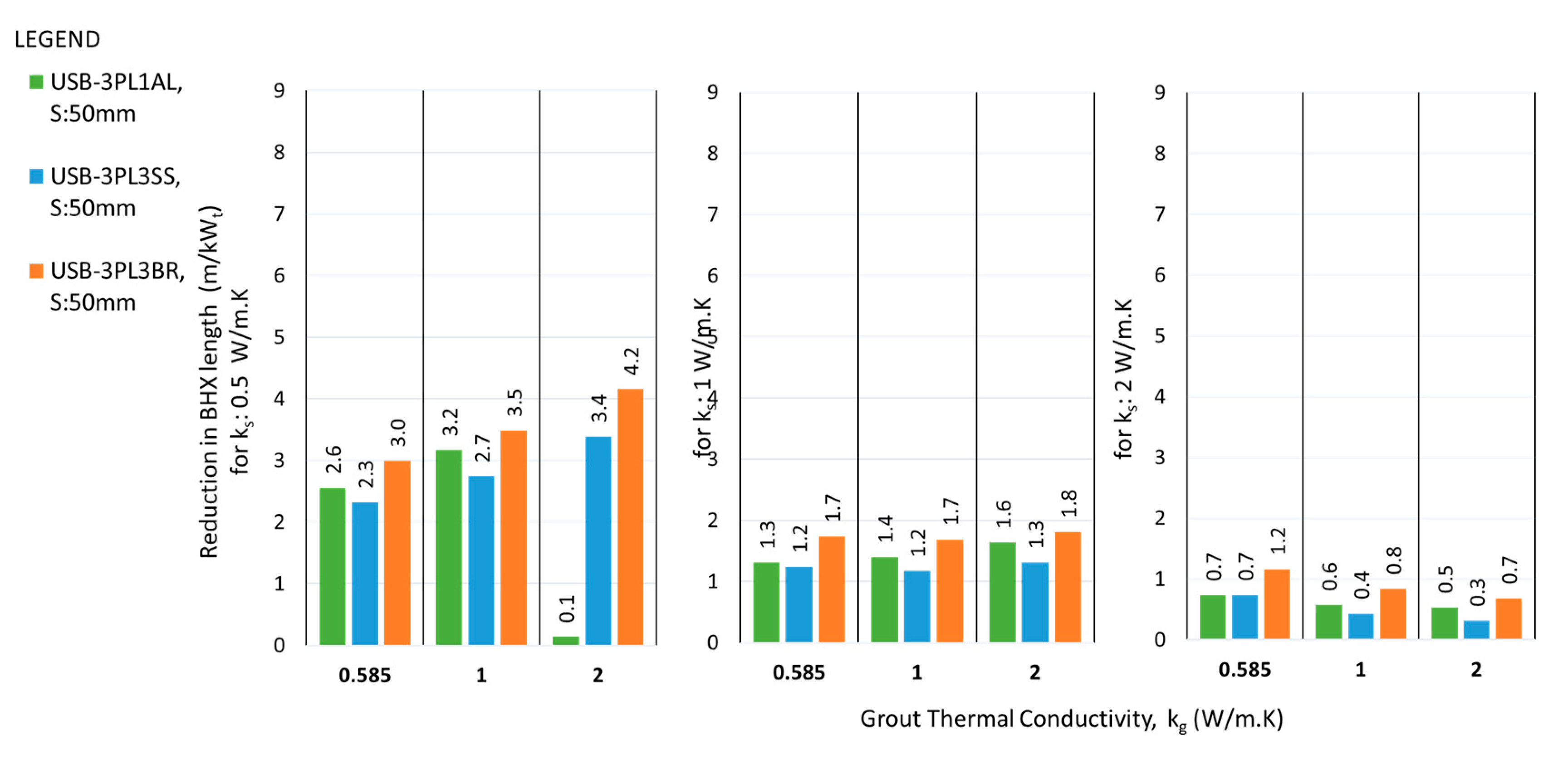

3.7.3. Impact of Double U-Shape Barrier on BHX Length:

4. Discussion

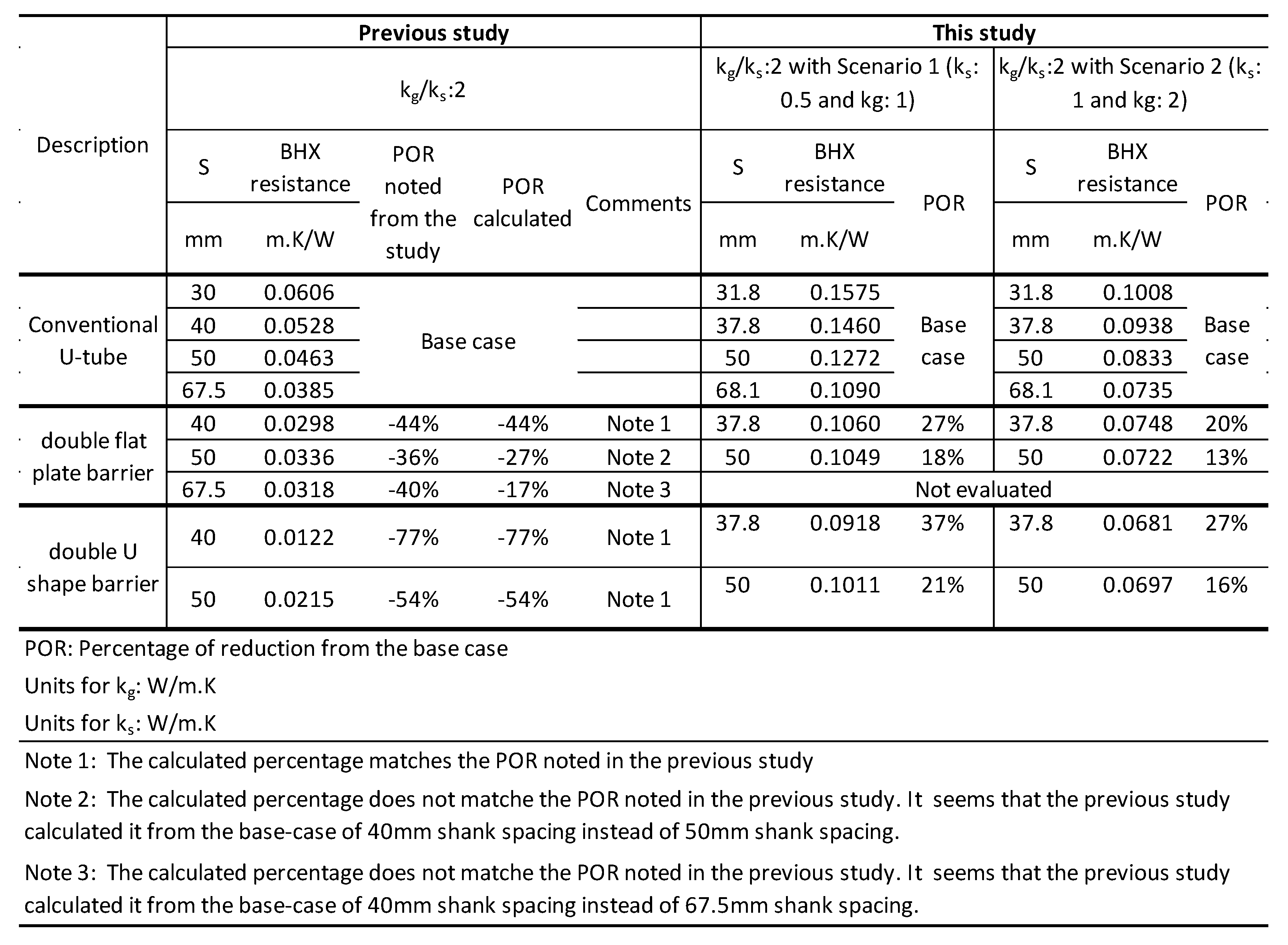

4.1. Comparision of this Study with the Previous Studies:

- ks of 0.5 W/m.K & kg of 1 W/m.K

- ks of 1 W/m.K & kg of 2 W/m.K

4.2. Ccomparision of Different Barriers with Conventional U-Tube:

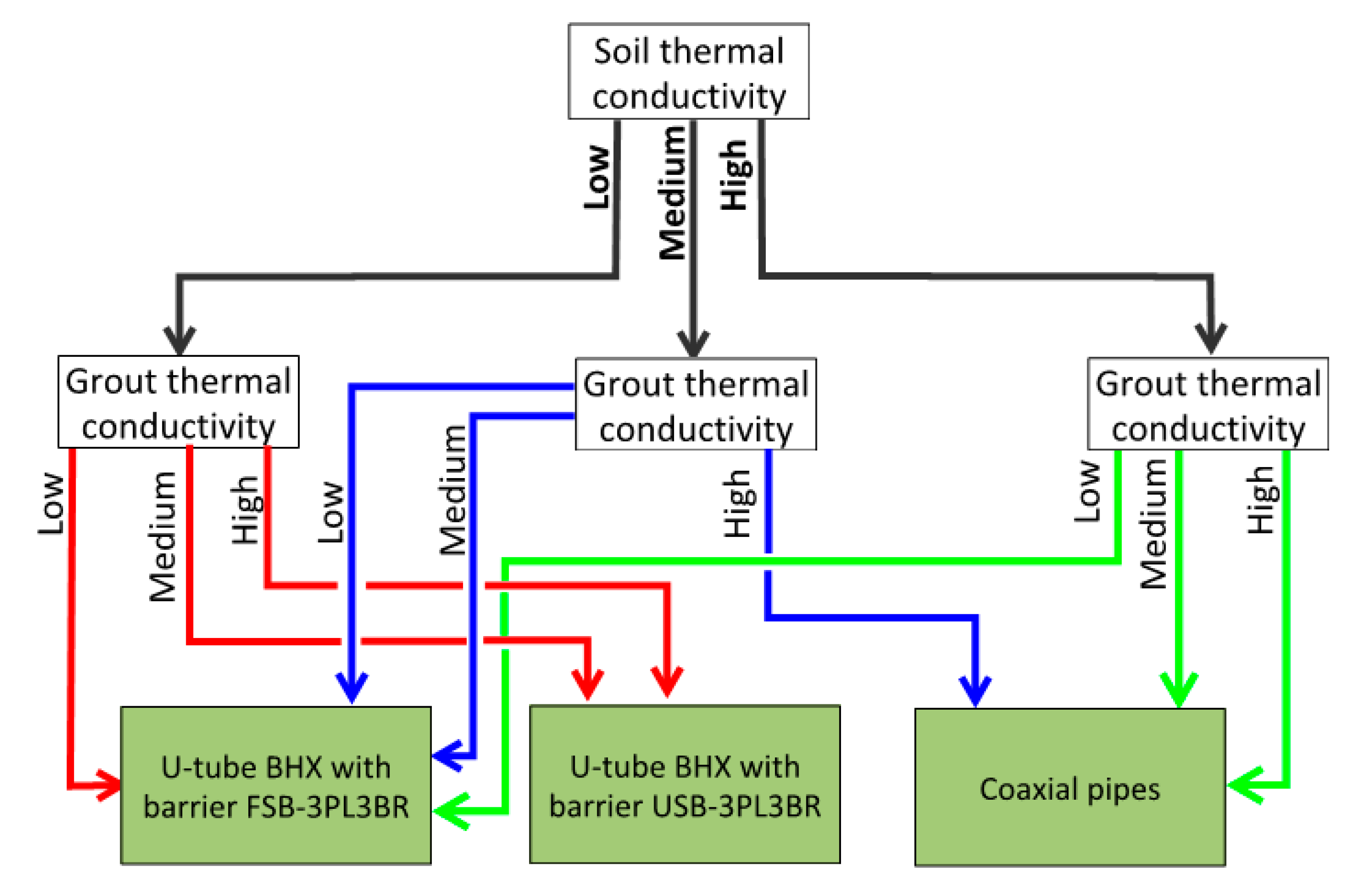

4.3. Overall Comparision of Different Ground Heat Exchange Systems Discussed in this Study:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Nomenclature

| FSB-3PL1 | Flat plate shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K |

| FSB-3PL2 | Flat plate shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.5 W/m.K |

| FSB-3PL3 | Flat plate shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 2 W/m.K |

| FSB-3PLMT | Flat plate shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K & 0.2mm metal tape of thermal conductivity 200 W/m.K |

| FSB-3SS | Flat plate shape barrier- 3mm stainless steel of thermal conductivity 16 W/m.K |

| FSB-3BR | Flat plate shape barrier- 3mm brass of thermal conductivity 109 W/m.K |

| FSB-3PL1AL | Double flat plate shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K & 1mm aluminum of thermal conductivity 237 W/m.K |

| FSB-3PL3SS | Double flat plate shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K & 3mm stainless steel of thermal conductivity 16 W/m.K |

| FSB-3PL3BR | Double flat plate shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K & 3mm brass of thermal conductivity 109 W/m.K |

| USB-3PL | U-shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K |

| USB-3PLMT | U-shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K & 0.2mm metal tape of thermal conductivity 200 W/m.K |

| USB-3SS | U-shape barrier- 3mm stainless steel of thermal conductivity 16 W/m.K |

| USB-3BR | U-shape barrier- 3mm brass of thermal conductivity 109 W/m.K |

| USB-3PL1AL | Double U-shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K & 1mm aluminum of thermal conductivity 237 W/m.K |

| USB-3PL3SS | Double U-shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K & 3mm stainless steel of thermal conductivity 16 W/m.K |

| USB-3PL3BR | Double U-shape barrier- 3mm plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K & 3mm brass of thermal conductivity 109 W/m.K |

| Ac | Area of cross-section in m2 |

| BHX | Borehole heat exchanger |

| BHXs | Borehole heat exchangers |

| Cp | Specific heat at constant pressure in kJ/kg.K |

| ΔT | Temperature difference |

| Db | Borehole diameter in mm or m |

| Dh | Hydraulic diameter in mm or m |

| Dp | Pipe external diameter in mm or m |

| h | Convective heat transfer coefficient of the fluid in W/m2K |

| kg | Grout thermal conductivity in W/m.K |

| kp | Pipe thermal conductivity in W/m.K |

| ks | soil thermal conductivity in W/m.K |

| kWt | kilo-watt thermal |

| L | Length of U tube pipe |

| mf | Mass flow rate of fluid |

| Nu | Nusselt number |

| Pr | Prandtl number |

| Q or q | Heat flow rate in W/m |

| Qin | Heat transfer rate in the inlet pipe in W/m |

| Qout | Heat transfer rate in the outlet pipe in W/m |

| qgen | Heat generated in W |

| r1 | Pipe internal radius in mm or m |

| rb | Borehole radius in mm or m |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| Rb | Thermal resistance of borehole in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rfo | Thermal resistance of fluid in the inside pipe for coaxial pipes in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rfo | Thermal resistance of fluid in the outside pipe for coaxial pipes in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rg | Thermal resistance of grout in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rins | Thermal resistance of insulation for coaxial pipes in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rp | Thermal resistance of pipe for U-tube BHX in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rpi | Thermal resistance of inside pipe for coaxial pipes in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rpo | Thermal resistance of outside pipe for coaxial pipes in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rpvc | Thermal resistance of PVC protective pipe for coaxial pipes in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rs | Thermal resistance of soil in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rsc | Thermal resistance due to short-circuit between inlet & outlet pipes in (W/m.K)-1

|

| Rt | Total thermal resistance of BHX in (W/m.K)-1

|

| S or s | Shank spacing in mm or m |

| Smax | Maximum Shank spacing in mm or m |

| Savg | Average Shank spacing in mm or m |

| Smin | Minimum Shank spacing in mm or m |

| Ts | undisturbed soil temperature at far-field boundary in °C |

| Tbhw | temperature of borehole wall in °C |

| Tf | Average Fluid Temperature of inlet and outlet pipe of U tube heat exchanger in °C |

| Tfi | Average Fluid Temperature of inlet pipe of U tube heat exchanger in °C |

| Tfo | Average Fluid Temperature of outlet pipe of U tube heat exchanger in °C |

| Vavg | Average velocity of fluid in m/s |

| α | Thermal diffusivity in m2/s |

| ρ | Density in kg/m3

|

| τ | Time |

| γ | Euler's constant = 0.5772 |

| ASHRAE | American Society of Heating, Refrigeration & Air-conditioning Engineers |

| GSHP | Ground source heat pump |

| HDPE | High density polyethylene |

| PDE | Partial differential equation |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| TRT | Thermal response test |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| uPVC | Un-plasticized polyvinyl chloride |

References

- Sarbu, I. and C. Sebarchievici, Using Ground-Source Heat Pump Systems for Heating/Cooling of Buildings, in Advances in Geothermal Energy. 2016. p. 17.

- Kavanaugh, S. and K. Rafferty, Geothermal heating and Cooling, Design of Ground Source heat Pump systems. 2014: W. Stephen Comstock.

- ASHRAE-Applications, ed. ASHRAE Handbook, Applications, SI Edition 2023. ed. A.T. Committees. 2023.

- Yoon, S., S. Lee, and G. Go, A numerical and experimental approach to the estimation of borehole thermal resistance in ground heat exchangers. Energy 2014, 71, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, L., Fundamentals of Geothermal Heat Pump Systems, Design and Application. 2020: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Al-Chalabi, R. , Thermal Resistance of U-tube Borehole Heat Exchanger System: Numerical Study, Thesis for Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering, University of Manchester., in School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering, University of Manchester. 2013.

- Kerme, E.D., A. S. Fung, and W.H. Leong, Analysis of the Combined Effect of Major Influencing Parameters for Designing High-Performance Single (sBHE) and Double (dBHE) U-Tube Borehole Heat Exchangers. Energies 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J., et al., Comprehensive thermal performance analysis and optimization study on U-type deep borehole ground source heat pump systems based on a new analytical model. Energy 2023, 274.

- Erol, S. and B. François, Efficiency of various grouting materials for borehole heat exchangers. Applied Thermal Engineering 2014, 70, 788–799. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, M. , et al. , A review of grout materials in geothermal energy applications. International Journal of Thermofluids 2021, 10, 100070. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. , et al. An Analysis on Cost Reduction Potential of Vertical Bore Ground Heat Exchangers Used for Ground Source Heat Pump Systems. in Stanford Geothermal Workshop 44th Annual Conference. 2019. Stanford, California, United States of America.

- Zanchini, E. , et al., Effects of flow direction and thermal short-circuiting on the performance of coaxial ground heat exchangers in International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ’09) 2009: Valencia, Spain.

- Brown, C.S. , et al., Comparison of the thermal and hydraulic performance of single U-tube, double U-tube and coaxial medium-to-deep borehole heat exchangers. Geothermics, 2024. Volume 117.

- Harris, B.E. , et al., Analysis of the transient performance of coaxial and u-tube borehole heat exchangers. Geothermics 2022 101.

- Chen, J. , et al. , Research on ground-coupled heat exchangers. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies 2010, 5, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. and I. Tomac, Technical review on coaxial deep borehole heat exchanger. Geomechanics and Geophysics for Geo-Energy and Geo-Resources 2023, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, I.L. and V.H. Ngo, A new design of ground heat exchanger with insulation plate for effectively geothermal management. Geothermics 2022, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE-Fundamentals, ASHRAE Handbook, Fundamentals, SI Edision, 2021, ed. A.T. Committees. 2021: ASHRAE.

- Javadi, H. , et al., Performance of ground heat exchangers: A comprehensive review of recent advances. Energy 2019, 178, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdic, L., T. Zakula, and L. Boban, Improved Analysis of Borehole Heat Exchanger Performance. Energies 2023, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Mendrinos, D., S. Katsantonis, and C. Karytsas, Pipe materials for borehole heat exchangers, in European Geothermal Congress.

- 2016: Strasbourg, France.

- Eskilson, P. , Thermal Analysis of Heat Extraction Boreholes, in Department of Mathematical Physics. 1987, University of Lund, Sweden.

- Ruan, W. and W.T. Horton, Model-Based Performance Analysis of a Single Borehole in Ground Heat Exchanger, in International High Performance Buildings Conference. 2010: Purdue.

- Zhou, K. , et al., Prediction and parametric analysis of 3D borehole and total internal thermal resistance of single U-tube borehole heat exchanger for ground source heat pumps. Energy and Built Environment 2023, 4, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Naterer, G. F. Naterer, G., Advanced Heat Transfer. 2021, Milton, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Faizal, M., A. Bouazza, and R. M. Singh, Heat transfer enhancement of geothermal energy piles. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 57, 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, H. and R. M. Singh, Driven precast concrete geothermal energy piles: Current state of knowledge. Building and Environment 2023, 228, 109790. [Google Scholar]

- https://toyesi.com.au/, Are Geothermal Heat Pumps for Me. 2024, Toyesi.

- Barry-Macaulay, D. , et al., Thermal conductivity of soils and rocks from the Melbourne (Australia) region. Engineering geology 2013, 164, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usowicz, B. , et al., Thermal properties of soil in the Murrumbidgee River Catchment (Australia). International journal of heat and mass transfer 2017, 115, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M.L. and S.P. Kavanaugh, Thermal Conductivity of Cementitious Grouts and Impact On Heat Exchanger Length Design for Ground Source Heat Pumps. HVAC&R Research 2011, 5, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Holman, J.P. , Heat Transfer, Tenth Edition. 2010: McGraw Hill.

- https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com, Thermal Conductivity of common Materials and Gases. n.d.

- Olam, M. , Mechanical and Thermal Properties of HDPE/PET Microplastics, Applications, and Impact on Environment and Life. IntechOpen, 2023.

- acu-tech.com.au, HDPE Pipe Systems, Product Catalogue. Acu-Tech Piping systems.

- Sharqawy, M.H., E. M. Mokheimer, and H.M. Badr, Effective pipe-to-borehole thermal resistance for vertical ground heat exchangers. Geothermics 2009, 38, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, L., S. Kajl, and B. Beauchamp, A review of methods to evaluate borehole thermal resistances in geothermal heat-pump systems. Geothermics 2010, 39, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q. , et al., Effective Borehole Thermal Resistance of A Single U-Tube Ground Heat Exchanger. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications 2012, 62, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuel-Naga, H. and R. Al-Chalabi, Borehole thermal resistance of U-tube borehole heat exchanger. Géotechnique Letters 2016, 6, 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, N.D. , The Effect of Grout Thermal Conductivity on Vertical Geothermal Heat Exchanger Design and Performance. 1996, South Dakota University, Vermillion, SD, USA: USA.

- Bennet, J., J. Claesson, and G. Hellström, Multipole method to compute the conductive heat transfer to and between pipes in a composite cylinder. Notes on heat transfer 3-1987., in Department of Building Physics. 1987, Lund Institute of Technology, Lund,Sweden.

- Gu, Y. and D.L. O'Neal, Development of an equivalent diameter expression for vertical U-tubes used in ground-coupled heat pumps. ASHRAE Transactions 1998, 104, 347. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, G. , Ground heat storage,thermal analyses of duct storage systems, part I: Theory, in MathematicalPhysics. 1991, University of Lund, Lund, Sweden: Sweden.

- Shonder, J.A. and J.V. Beck, Field test of a new method for determining soil formation thermal conductivity and borehole resistance / Discussion. ASHRAE Transactions 2000, 106, 843. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, S. and J.D. Spitler, Calculation of borehole thermal resistance, in Advances in Ground-Source Heat Pump Systems, S. Rees, Editor. 2016, Elsevier Science & Technology.

- http://www.aeroflexusa.com, EPDM Sheet and Roll insulation Data Sheet 062424. 2024, Aeroflex.

- Luo, Y., G. Xu, and T. Yan, Performance evaluation and optimization design of deep ground source heat pump with non-uniform internal insulation based on analytical solutions. Energy and Buildings 2020, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzturk, C., Modelling of vertical ground loop heat exchangers for ground source heat pump systems, in Faculty of the Graduate College 1999, Oklahoma State University.

- Pan, A. , et al., A new analytical heat transfer model for deep borehole heat exchangers with coaxial tubes. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2019, 141, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnielinski, V. , Turbulent Heat Transfer in Annular Spaces—A New Comprehensive Correlation. Heat Transfer Engineering 2015, 36, 787–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, A., Pipe Dimensions chart Rev Jan 2012.

- Box, T.E.T. , ANSI Schedule 40 Steel Pipes - Dimensions. n.d.

- www.iplex.com.au, Iplex PVC U Pressure Series-1 Pipe-Dimensions. n.d.

- https://www.professionalplastics.com, Professional Plastics Thermal Properties of Plastic Materials n.d.

- Patti, A. and D. Acierno, Thermal Conductivity of Polypropylene-Based Materials. 2019.

- www.3M.com/electronics, 3M(TM) Thermally Conductive Heat Spreading Tape 9876.

- Thyssenkrupp, Stainless Steel 304 - 1. 4301 Data Sheet thyssenkrupp Materials (UK). 2024.

- Zhang, A. and Y. Li, Thermal Conductivity of Aluminum Alloys-A Review. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar]

| S. No. | Model Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Un-disturbed soil temperature Ts | 15 | °C |

| 2 | Temperature of the outlet pipe of U-tube, Tfi | 9 | °C |

| 3 | Temperature of the inlet pipe of U-tube, Tfo | 6 | °C |

| 4 | 7.5 | °C | |

| 5 | Borehole Diameter, Db | 100 | mm |

| 6 | Various soils thermal conductivity, ks, considered in the analysis are: | 0.5 | W/m.K |

| 1 | W/m.K | ||

| 2 | W/m.K | ||

| 7 | Various grouts thermal conductivity, kg, considered in the analysis are: | 0.585 | W/m.K |

| 1 | W/m.K | ||

| 2 | W/m.K | ||

| 8 | Various shank spacing options, S, considered in the analysis are: | 31.8 | mm |

| 50 | mm | ||

| 68.1 | mm | ||

| 9 | U-tube pipe material | High density polyethylene (HDPE) | - |

| 10 | Pipe thermal conductivity [33, 34] | 0.45 | W/m.K |

| 11 | Pipe outer diameter, dpo [35] | 31.8 | mm |

| 12 | Pipe thickness, tp [35] | 2.9 | mm |

| 13 | Fluid (water) density [32] | 999.5 | kg/m3 |

| 14 | Fluid (water) dynamic viscosity [32] | 0.001418 | kg/m.s |

| 15 | Fluid Prandtl number [32] | 10.2768 | - |

| 16 | Calculated Reynolds number for fluid | 22,164 | - |

| 17 | Calculated Nusselt number for fluid | 174.98 | - |

| 18 | Calculated Convective heat transfer coefficient of fluid, h | 3,907 | W/m2.K |

| S. No. | Model Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | °C | |

| 2 | Inlet (Outer) pipe material | Black steel | - |

| 3 | Inlet (Outer) pipe thermal conductivity [33] | 43 | W/m.K |

| 4 | Inlet (Outer) pipe diameter (external) [51, 52] | 48.3 | mm |

| 5 | Inlet (Outer) pipe thickness [51, 52] | 3.68 | mm |

| 6 | Outlet (Inner) pipe material | HDPE | - |

| 7 | Outlet (Inner) pipe thermal conductivity [33, 34] | 0.45 | W/m.K |

| 8 | Outlet (Inner) pipe diameter (external) [35] | 25 | mm |

| 9 | Outlet (Inner) pipe thickness [35] | 2.3 | mm |

| 10 | Thickness of insulation on outlet (inner) pipe | 3 | mm |

| 11 | Thermal conductivity of insulation [46] | 0.0342 | W/m.K |

| 12 | Thickness of uPVC protective pipe [53] | 1.5 | mm |

| 13 | Thermal conductivity of uPVC protective pipe [54] | 0.17 | W/m.K |

| 14 | Inlet fluid (Water at 6⁰C): | ||

|

999.6 | kg/m3 | |

|

0.001483 | kg/m.s | |

|

10.8029 | ||

|

55.66 | ||

|

7,355 | ||

|

0.0378 | ||

|

4,634 | W/m2.K | |

| 15 | Outlet fluid (Water at 9⁰C): | ||

|

999.3 | kg/m3 | |

|

0.00135 | kg/m.s | |

|

9.7507 | ||

|

23,276 | ||

|

215.94 | ||

|

6,173 | W/m2.K |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).