Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Thrust Faults Used for the Analysis

4. HPEs Abundances and Heat Production

5. Crustal Model

6. Regional Heat Flows and Crustal HPEs Abundances at the Noachian-Hesperian Boundary

7. Building a Global Heat Flow Model for 3.7 Ga

7.1. Heat Flow Model Based on Thrust Fault Depths (Mars “Without Plumes”)

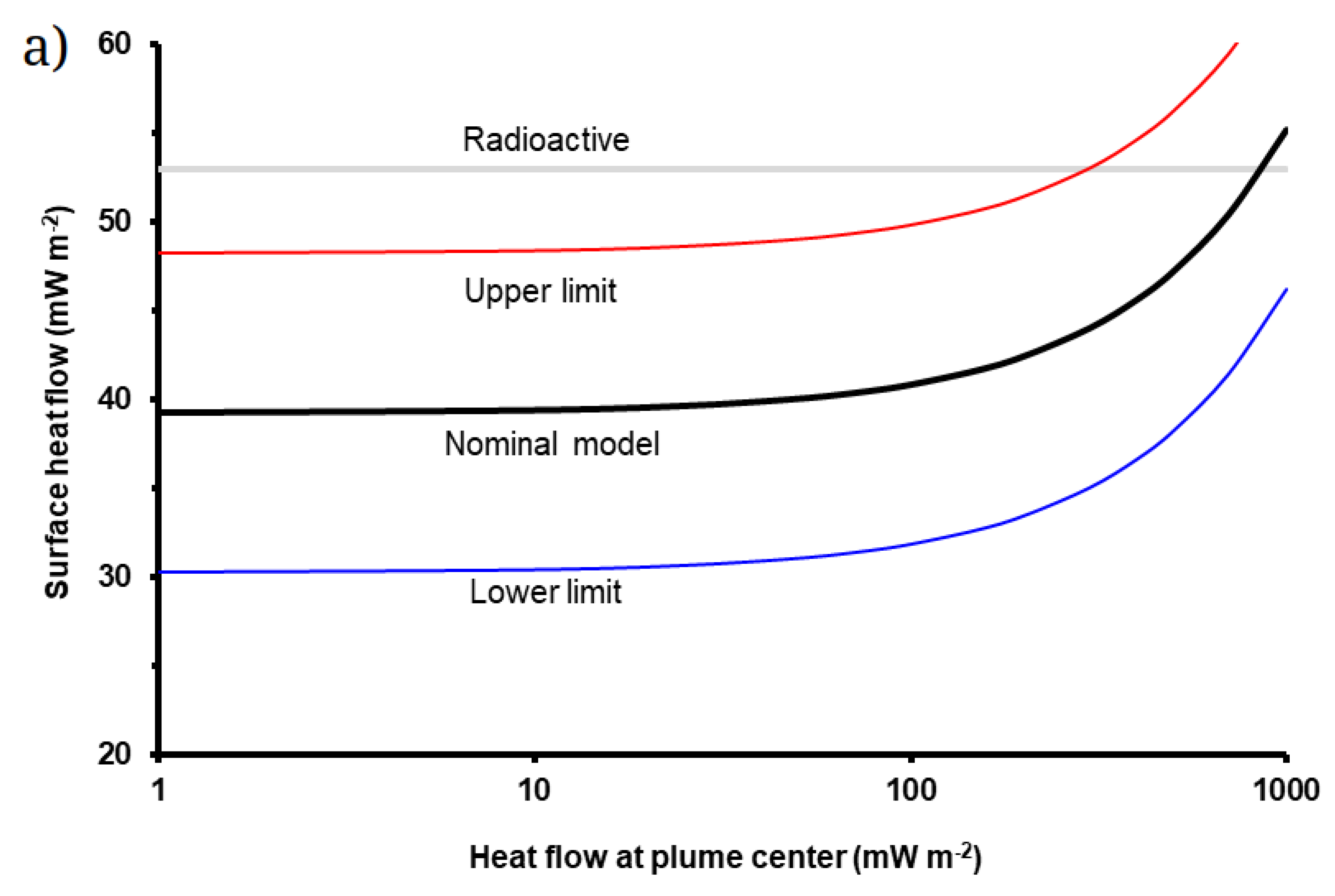

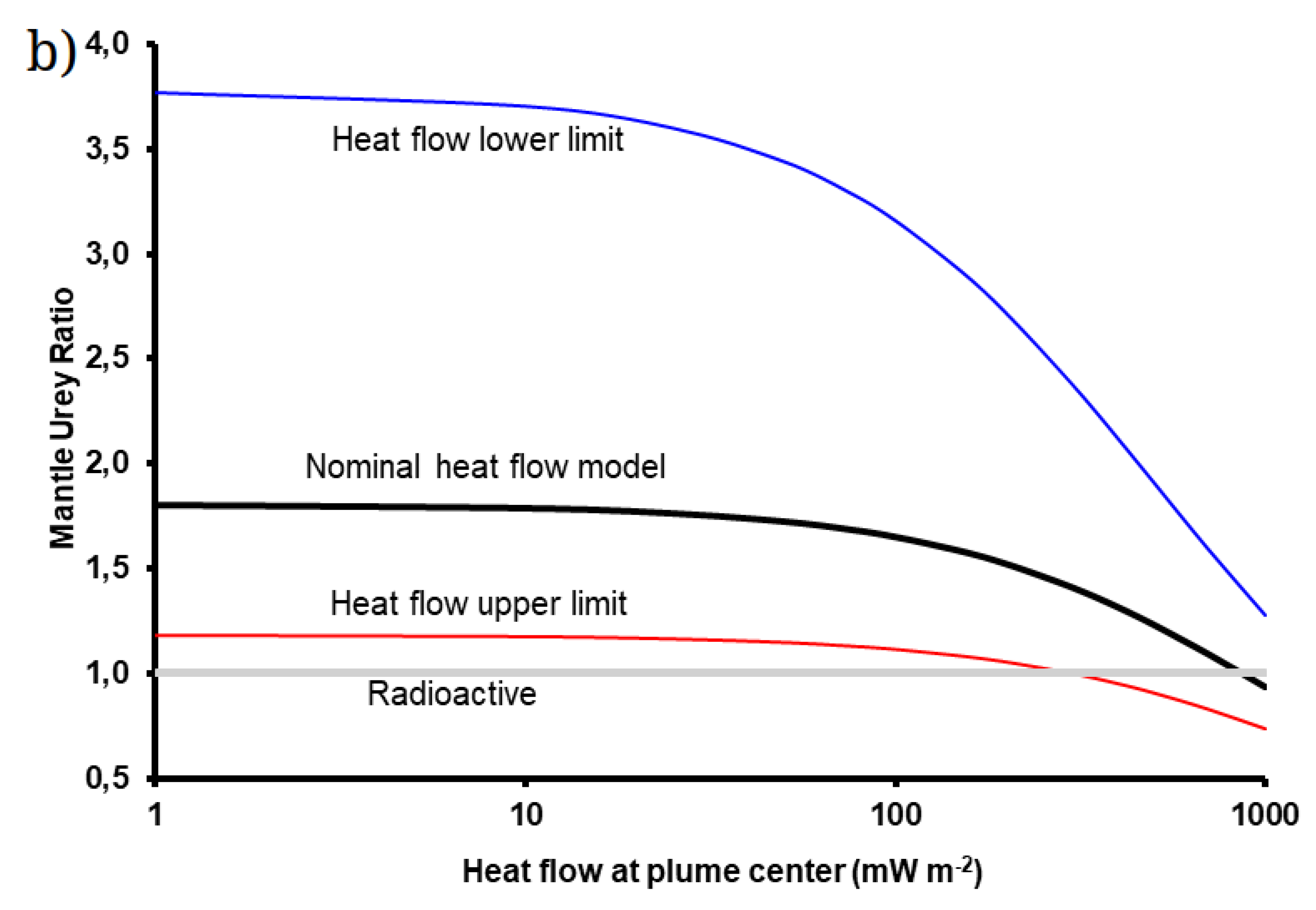

7.2. Global Heat Flow Model with Large Plumes

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

10. Acknowledgments, Samples, and Data

References

- Solomon, S.C. et al. New perspectives on ancient Mars. Science 2005, 307, 1214-1220.

- Carr, M.H. & Head, J.W. Geologic history of Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 294, 185-203.

- Fassett, C. I. & Head, J. W. Sequence and timing of conditions on early Mars. The timing of martian valley network activity: constraints from buffered crater counting. Icarus 2011, 211, 1204-1214.

- Ramirez, R. M. & Craddock, R. A. The geological and climatological case for a warmer and wetter early Mars. Nature Geoscience 2018, 11, 230-237.

- Mangold, N., Adeli, S., Conway, S., Ansan, V. & Langlais, B. A chronology of early Mars climatic evolution from impact crater degradation. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, E04003.

- Bibring, J. P. et al. Global mineralogical and aqueous Mars history derived from OMEGA/Mars express data. Science 2006, 312, 400–404.

- Ehlmann, B. L. et al. Subsurface water and clay mineral formation during the early history of Mars. Nature 2011, 479, 53–60.

- Baratoux, D., Toplis, M. J., Monnereau, M. & Sautter, V. The petrological expression of early Mars volcanism. J. Geophys. Res. 2013, 118, 59–64.

- Wilson, J. H. & Mustard, J. F. Exposures of olivine-rich rocks in the vicinity of Ares Vallis: implications for Noachian and Hesperian volcanism. J. Geophys. Res. 2013, 118, 916–929.

- McSween, H. Y. Petrology on Mars. American Mineralogist 2015, 100, 2380-2395.

- Citron, R. I., Manga, M., & Hemingway, D. J. Timing of oceans on Mars from shoreline deformation. Nature 2018, 555, 643-646.

- Ruiz, J. The early heat loss evolution of Mars and their implications for internal and environmental history. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4338.

- Milbury, C., Schubert, G., Raymond, C. A., Smrekar, S. E. & Langlais, B. The history of Mars’ dynamo as revealed by modelling magnetic anomalies near Tyrrhenus Mons and Syrtis Major. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, E10007.

- Langlais, B., The´bault, E. Y., Quesnel, Y. & Mangold, N. A. Late Martian Dynamo Cessation Time 3.77 Gy Ago. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2012, 43, 1231.

- Steele, S.C., Fu, R.R., Muxworthy, A.R., Volk, M.W.R., Collins, G.S., North, T.L., Davison, T.M. Taleomagnetic evidence for a long-lived, potentially reversing martian dynamo at 3.9 Ga. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade9071.

- Ehlmann, B. L., et al. The sustainability of habitability on terrestrial planets: Insights, questions, and needed measurements from Mars for understanding the evolution of Earth-like worlds, J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2016, 121, 1927–1961.

- Solomon, S. C. & Head, J. W. Heterogeneities in the thickness of the elastic lithosphere of Mars: Constraints on heat flow and internal dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 11073–11083.

- Anderson, S. & Grimm, R.E. Rift processes at the Valles Marineris, Mars: Constraints from gravity on necking and rate-depending strength evolution. J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103, 11113–11124.

- McGovern, P. J. et al. Correction to Localized gravity/topography admittance and correlation spectra on Mars: implications for regional and global evolution. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109, E07007.

- Grott, M., Hauber, E., Werner, S. C., Kronberg, P. & Neukum, G. High heat flux on ancient Mars: Evidence from rift flank uplift at Coracis Fossae. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L21201.

- Ruiz, J., McGovern, P. J. & Tejero, R. The early thermal and magnetic state of the cratered highlands of Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 241, 2–10.

- Ruiz, J. et al. The thermal evolution of Mars as constrained by paleo-heat flows. Icarus 2011, 15, 508–517.

- Schultz, R. A. & Watters, T. R. Forward mechanical modeling of the Amenthes Rupes thrust fault on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 4659–4662.

- Grott, M., Hauber, E., Werner, S.C., Kronberg, P., Neukum, G. Mechanical mod- eling of thrust faults in the Thaumasia region, Mars, and implications for the Noachian heat flux. Icarus 2007, 186, 517–526.

- Ruiz, J. et al. Ancient heat flow, crustal thickness, and lithospheric mantle rheology in the Amenthes region, Mars. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2008, 270, 1–12.

- Ruiz, J. et al. Ancient heat flows and crustal thickness at Warrego rise, Thaumasia Highlands, Mars: Implications for a stratified crust. Icarus 2009, 203, 47–57.

- Mueller, K., Vida, A., Robbins, S., Golombek, M., & West, C. Fault and fold growth of the Amenthes uplift: implications for Late Noachian crustal rheology and heat flow on Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014, 408, 100–109.

- Egea-González, I., Jiménez-Díaz, A., Parro, L.M., Lopez, V., Williams, J.P., & Ruiz, J. Thrust fault modeling and Late-Noachian lithospheric structure of the circum-Hellas region, Mars. Icarus 2017, 288, 53–68.

- Herrero-Gil, A., Egea-González, I., Ruiz, J., & Romeo, I. Structural modeling of lobate scarps in the NW margin of Argyre impact basin, Mars. Icarus 2019, 319, 367-380.

- Smith, D. et al. Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter: Experiment summary after the first year of global mapping of Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 23,689-23,722.

- Gwinner, K., Scholten, F., Preusker, F., Elgner, S., Roatsch, T., Spiegel, M., Schmidt, R., Oberst, J., Jaumann, R., Heipke, C. Topography of Mars from global mapping by HRSC high-resolution digital terrain models and orthoimages: Characteristics and performance. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 294, 506-519.

- Watters, T.R., & Robinson, M.S. Lobate scarps and the Martian crustal dichotomy. J. Geophys. Res. 1999, 104, 18981–18990.

- Tanaka, K.L., et al. The digital global geologic map of Mars: Chronostratigraphic ages, topographic and crater morphologic characteristics, and updated resurfacing history. Planet. Space Sci. 2014, 95, 11–24.

- Herrero-Gil, A., I. Egea-González, A. Jiménez-Díaz, S. Rivas-Dorado, L.M. Parro, C. Fernández, J. Ruiz, I. Romeo. Lithospheric contraction concentric to Tharsis: structural modeling of large thrust faults between Thaumasia highlands and Aonia Terra, Mars. Journal of Structural Geology 2023, 177, 104983, 1-15.

- Atkins, R. M., Byrne, P. L., & Wegmann, K. W. Morphometry and timing of major crustal shortening structures on Mars, Lunar Planet. Sci. 2019, 50, Abstract 2132.

- Parro, L. M., Jiménez-Díaz, A., Mansilla, F., & Ruiz, J. Present-day heat flow model of Mars. Nature Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 45629.

- Boynton, W.V., et al. Concentration of H, Si, Cl, K, Fe, and Th in the low and mid latitude regions of Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, E12S99.

- Hahn, B. C., McLennan, S. M., & Klein, E. C. Martian surface heat production and crustal heat flow from Mars Odyssey gamma-ray spectrometry. Geophysical Research Letters 2011, 38, L14203.

- Rani, A., Basu Sarbadhikari, A., Hood, D. R., Gasnault, O., Nambiar, S., & Karunatillake, S. Consolidated chemical provinces on Mars: Implications for geologic interpretations. Geophysical Research Letters 2022, 49, e2022GL099235.

- Meyer, C. Mars Meteorite Compendium. Lyndon B. Johnson Space Cent. 2003, NASA, Houston, Tex.

- Herrero-Gil, A., Ruiz, J., Romeo, I. 3D modeling of planetary lobate scarps: the case of Ogygis Rupes, Mars. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 2020a, 532, 116004.

- Herrero-Gil, A., Ruiz, J., Romeo, I. Lithospheric contraction on Mars: a 3D model of the Amenthes thrust fault system. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 2020b, 125, e2019JE006201.

- Taylor, G.J., et al. Bulk composition and early differ- entiation of Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, E03S10.

- Wieczorek, M. A., Broquet, A., McLennan, S. M., Rivoldini, A., Golombek, M., Antonangeli, D., et al. InSight constraints on the global character of the Martian crust. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2022, 127, e2022JE007298.

- Jellinek, A. M., Johnson, C. L., & Schubert, G. Constraints on the elastic thickness, heat flow, and melt production at early Tharsis from topography and magnetic field observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, E09004.

- Ranalli, G. Rheology of the lithosphere in space and time. Geol. Soc. Spec. Pub. 1997, 121, 19–37.

- Frey, H.V. Impact constraints on, and a chronology for, major events in early Mars history. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, E08S91.

- Broquet, A., & Wieczorek, M. A. The gravitational signature of Martian volcanoes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2019, 124, 2054–2086.

- Watters, T. R., Schultz, R. A., Robinson, M. S., & Cook, A. C. The mechanical and thermal structure of Mercury’s early lithosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29, 37-1.

- Taylor, S.R., McLennan, S.M. Planetary Crusts: Their Composition, Origin and Evolution. Cambridge Univ. Press 2009.

- Rani, A., Basu Sarbadhikari, A., Hood, D.R., Gasnault, O., Nambiar, S., Karunatillake, S. Consolidated chemical provinces on Mars: Implications for geologic interpretations. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 49, e2022GL099235.

- Boynton, W.V., et al. Concentration of H, Si, Cl, K, Fe, and Th in the low and mid latitude regions of Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, E12S99.

- McLennan, S.M. Large-ion lithophile element fractionation during the early differentiation of Mars and the composition of the Martian primitive mantle. Meteor. Planet. Sci. 2003, 38, 895-904.

- Van Schmus, W. R. Natural radioactivity of the crust and mantle. In: Ahrens, T.J. (Ed.), Global Earth Physics: A Handbook of Physical constants. AGU Reference Shelf 1. American Geophysical Union, Washington, DC 1995, 283–291.

- Zuber, M.T., et al. nternal structure and early thermal evolution of Mars from Mars Global Surveyor. Science 2000, 287, 1788-1793.

- Neumann, G.A., Zuber, M.T., Wieczorek, M.A., McGovern, P.J., Lemoine, F.G. & Smith, D.E. The crustal structure of Mars from gravity and topography. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109, E08002.

- Genova, A., Goossens, S., Lemoine, F.G., Mazarico, E., Neumann, G.A., Smith, D.E., & Zuber, M.T. Seasonal and static gravity field of Mars from MGS, Mars Odyssey and MRO radio science. Icarus 2016, 272, 228-245.

- Wieczorek, M. A., Beuthe, M., Rivoldini, A., & Van Hoolst, T. Hydrostatic interfaces in bodies with nonhydrostatic lithospheres. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2019, 124.

- Caristan, Y. he transition from high temperature creep to fracture in Mary- land diabase. J. Geophys. Res. 1982, 87, 6781–6790.

- Parmentier, E. M., & Zuber, M. T. Early evolution of Mars with mantle compositional stratification or hydrothermal crustal cooling, J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, E02007.

- Andrews-Hanna, J. C., Phillips R. J., & Zuber, M. T. Meridiani Planum and the global hydrology of Mars. Nature 2007, 446, 163–165.

- Beardsmore, G.R., & Cull, J.P. Crustal Heat Flow: A Guide to Measurement and Modelling. Cambridge University Press 2001, 324.

- Kieffer, H.H., et al. Thermal and albedo mapping of Mars during the Viking primary mission. J. Geophys. Res. 1977, 82, 4249–4291.

- Norman, M.D. The composition and thickness of the crust of Mars estimated from rare Earth elements and neodymium-isotopic compositions of martian meteorites. Meteor. Planet. Sci. 1999, 34, 439–449.

- Norman, M. D. hickness and composition of the martian crust revisited: Implications of an ultradepleted mantle with Nd isotopic composition like that of QUE94201. Lunar Planet. Sci. 2002, 33, Abstract 1175.

- Grott, M. Late crustal growth on Mars: Evidence from lithospheric extension. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L23201.

- Werner, S. C. The global martian volcanic evolutionary history. Icarus 2009, 201, 44–68.

- Carr, M. H. Volcanism on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 1973, 78, 4049 – 4062.

- McKenzie, D., Barnett, D. & Yuan, D.-N. The relationship between martian gravity and topography. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002, 195, 1–16.

- Wenzel, M. J., Manga, M., & Jellinek, M. Tharsis as a consequence of Mars’ dichotomy and layered mantle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L04702.

- Belleguic, V., Lognonne, P. & Wieczorek, M. Constraints on the martian lithosphere from gravity and topography data. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, E11005.

- Cohen, B. E. et al. Taking the pulse of Mars via dating of a plume-fed volcano. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 640.

- Day, J. M. D., et al. Martian magmatism from plume metasomatized mantle. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4799.

- Grott, M., & Breuer, D. On the spatial variability of the martian elastic lithosphere thickness: evidence for mantle plumes? J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 115, E03005.

- Wänke, H., Dreibus, G. Chemical composition and accretion history of terrestrial planets. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1988, A 325, 545–557.

- Drilleau, M., Samuel, H., Garcia, R.F., Rivoldini, A., Perrin, C., Michaut, C., et al. Marsquake locations and 1-D seismic models for Mars from InSight data. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2022, 127, e2021JE007067.

- Samuel., H., et al. Geophysical evidence for an enriched molten silicate layer above Mars’s core. Nature 2023, 622, 717-718.

- Khan, A., Huang, D., Durán, C., Sossi, P.A., Giardini, D., & Murakami M. Evidence for a liquid silicate layer atop the Martian core. Nature 2023, 622, 718-723.

- McGovern, P.J., Schubert, G. Thermal evolution of the Earth: effects of volatile exchange between atmosphere and interior. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1989, 96, 27-37.

- Sandu, C., Kiefer, W.S. Degassing history of Mars and the lifespan of its magnetic dynamo. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L03201.

- Wessel, P., Luis, J. F., Uieda, L., Scharroo, R., Wobbe, F., Smith, W. H. F., & Tian, D. The Generic Mapping Tools version 6. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2019, 20, 5556–5564.

- Watters, T.R., & Robinson, M.S. Lobate scarps and the Martian crustal dichotomy. J. Geophys. Res. 1999, 104, 18981–18990.

| Thrust | BDT depth (km)a | H (W )b | F (mW ) | b (km)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Warrego W | 17-21 | 0.46 | 53.1-43.9 | 98.78 | 1.18-0.98 |

| 2. Warrego E | 21-27 | 0.45 | 43.8-35.8 | 94.56 | 1.04-0.85 |

| 3. Amenthes Rupes | 20-24 | 0.45 | 45.8-35.2 | 58.03 | 1.76-1.35 |

| 4. Ogygis Rupes | 17-18 | 0.39 | 52.6-49.8 | 73.48 | 1.82-1.72 |

| 5. Phrixi Rupes | 16-19 | 0.43 | 56.0-47.7 | 78.58 | 1.67-1.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).