1. Introduction

Various attempts have been made to increase the solubility and bioavailability of drug candidates, including methods employing nanotechnology. The first FDA approved medication using nanotechnology was Rapamune (sirolimus), which was solubilized through wet milling method [

1]. Since then, a variety of nanotechnology has been developed, including solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, which require solid or solid/liquid fats as carriers. Advanced nanotechnology such as supercritical antisolvent (SAS) methods can increase the solubility of certain molecules, but it is a complicated process with limited use. Other nanotechnology methods include nano emulsions, nanogels, with either oil and surfactant, or crosslinked polymers. In addition, engineered nanoparticles can be made through metal organic frameworks, carbon nanotubes, mesoporous silica [2, 3]. In summary, current nanotechnology is involved in other ingredients/components and/or specific engineering methods.

In our previous research on the use of lipid-soluble green tea polyphenols, we invented technology to convert these lipid-soluble compounds to nanoparticles readily suspended in aqueous formulations. This technology is referred to as Facilitated Self-assembling Technology (FAST), which is simple and easy to perform, and has been used to generate nanoparticles comprised of epigallacatechin-3-gallate-palmitates (EC16) with consistent size range, and high stability [4, 5]. The FAST was developed in a project using an EC16 nanoformulation for nasal application against human coronavirus. We were able to prepare nasal nanoformulations with high efficacy against human coronavirus without mucociliary toxicity [4, 5]. The virucidal efficacy of EC16 nanoparticles is more than 100-fold than EGCG dissolved in DMSO [4, 6, 7]. These particles can be seen under electron microscopes as tightly packed self-assembled structures [

8].

Methods derived from FAST are easy, economical, and rapid, with self-assembled nanoparticles consist of identical hydrophobic molecules with a hydrophilic (negatively charged) moiety facing the aqueous phase. These nanoparticles are easy to suspend in water and other aqueous solutions and are stable in room temperature. The major advantage of this method is that it is not engineered or associated with another component. The nanoparticles can be dried or in liquid form. For example, EC16 nanoparticles can be used in various formulations, drugs, and consumer products for antiviral/virucidal, anti-biofilm, anti-inflammatory, anti-neurodegeneration, antiaging, and sporicidal purposes.

Based on the data generated from our laboratories, we hypothesize that FAST can be applied to many hydrophobic compounds with poor water solubility and/or bioavailability, to generate nanoparticles in stable aqueous nanosuspension or dry form to improve effectiveness and/or delivery efficiency.

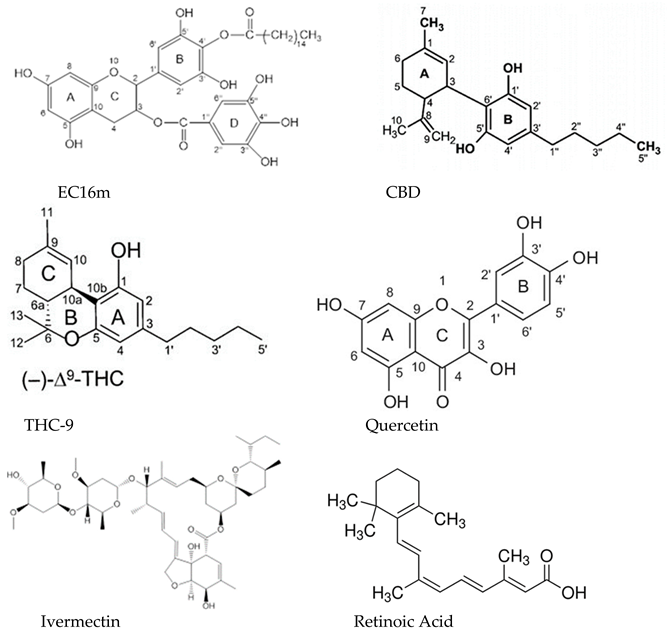

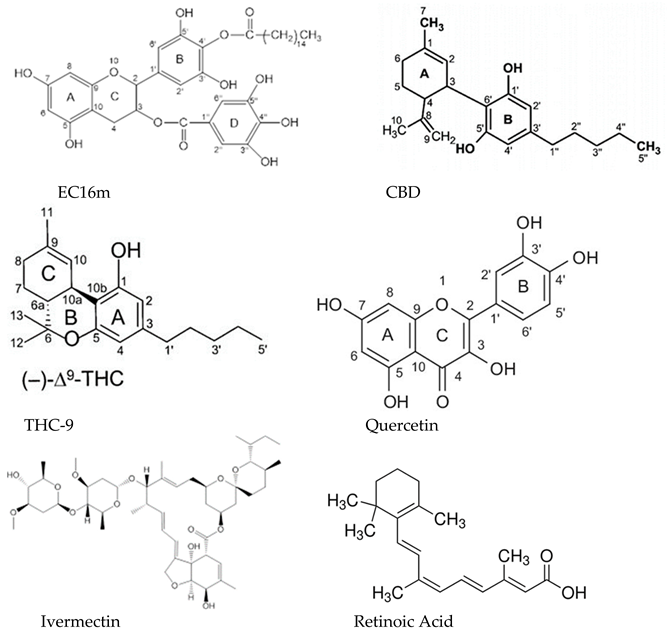

The current study is aimed to test our hypothesis by generating nanoparticles of Cannabidiol (CBD), Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC-9), quercetin, ivermectin, and retinoic acid (see structures of these hydrophobic compounds below, obtained from internet). If successful, FAST could lead to a wide range of applications for hydrophobic compounds to be developed for effective delivery to specific targets by oral, topical, nasal, inhalational, injectable, and other applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compounds and Oral Rinse

Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate-Palmitates (EC16) and Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate-Mono-Palmitate (EC16m) were obtained from Camellix, LLC (Evans, GA, USA). Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC-9, 06-722-453), Quercetin hydrate, 95% (AC174070100), Ivermectin (AAJ6277703), and Retinoic Acid, All Trans Isomer (MP021902695) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). Cannabidiol (CBD) powder was purchased from Amazon.com. Both unflavored and peppermint flavored oral rinse were provided by International Nutrition, Inc. (Middle River, MD, USA).

2.2. Preparation of Nanoparticles

The nanoparticles of the compounds were prepared using FAST (proprietary, patent pending) with three specific practical methods (I, II and III). Methods I and II were used for EC16 nanoparticle preparation and Method III were used in EC16m and other nanoparticle preparations. All nanoparticle stocks at 1% were stabilized in pure glycerol for further dilution with sterilized double stilled water. In addition, a food grade dispersing agent was used in the water nanosuspensions of some nanoparticles as described. The oral rinse formulations were mixed directly with the EC16 nanoparticle stock to 0.01%. EC16 nanoparticle powder was obtained by centrifugation of 0.1% EC16 water nanosuspension at 13,400 RPM for 45 minutes, followed by washing with purified water twice before final centrifugation. Subsequently, pellets were collected and dried. The EC16 nanoparticle powder was then reconstituted with water for analysis.

2.3. Evaluation of Particle Size Distribution

ZetaView nanoparticle tracking analysis was performed according to a method described previously [

4,

5]. The particle size distribution and concentration were measured using the ZetaView ×20 (Particle Metrix, Meerbusch, Germany) and corresponding software. The measuring range for particle diameter is 10–2000 nm. All samples were diluted by the same volume of 1× PBS and then loaded into the cell. Particle information was collected from the instrument at 11 different positions across the cell, with two cycles of readings. Standard operating procedure was set to a temperature of 23 °C, a sensitivity of 70, a frame rate of 30 frames per second, and a shutter speed of 100. The post-acquisition parameters were set to a minimum brightness of 20, a maximum area of 1000, a minimum area of 10, and a trace length of 15 [

4,

5].

2.4. Electron microscopy imaging of EC16 nanoparticles.

The 1% EC16 nanoparticle stock was diluted with PBS to 0.01% and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde. After mixing, 5 µl of the sample was removed and transferred to a Formvar/Copper 200 mesh grid and allowed to dry for 15 minutes. Excess solution was then removed using filter paper particles and was negatively stained by addition of 5 µl of 2% aqueous uranyl acetate. Multiple images were captured from each sample in a JEM 1400Flash Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL, Peabody, MA) at 120kV, using a Gatan OneView Digital Camera (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA).

3. Results

3.1. EC16 and EC16m Nanoparticles

Three different methods based on FAST were used for preparing the nanoparticles. Methods I and II were used in EC16 nanoparticle preparation and Method III were used in EC16m and other nanoparticle preparations. In addition, a food grade dispersing agent was used in the water nanosuspensions of some nanoparticles as described.

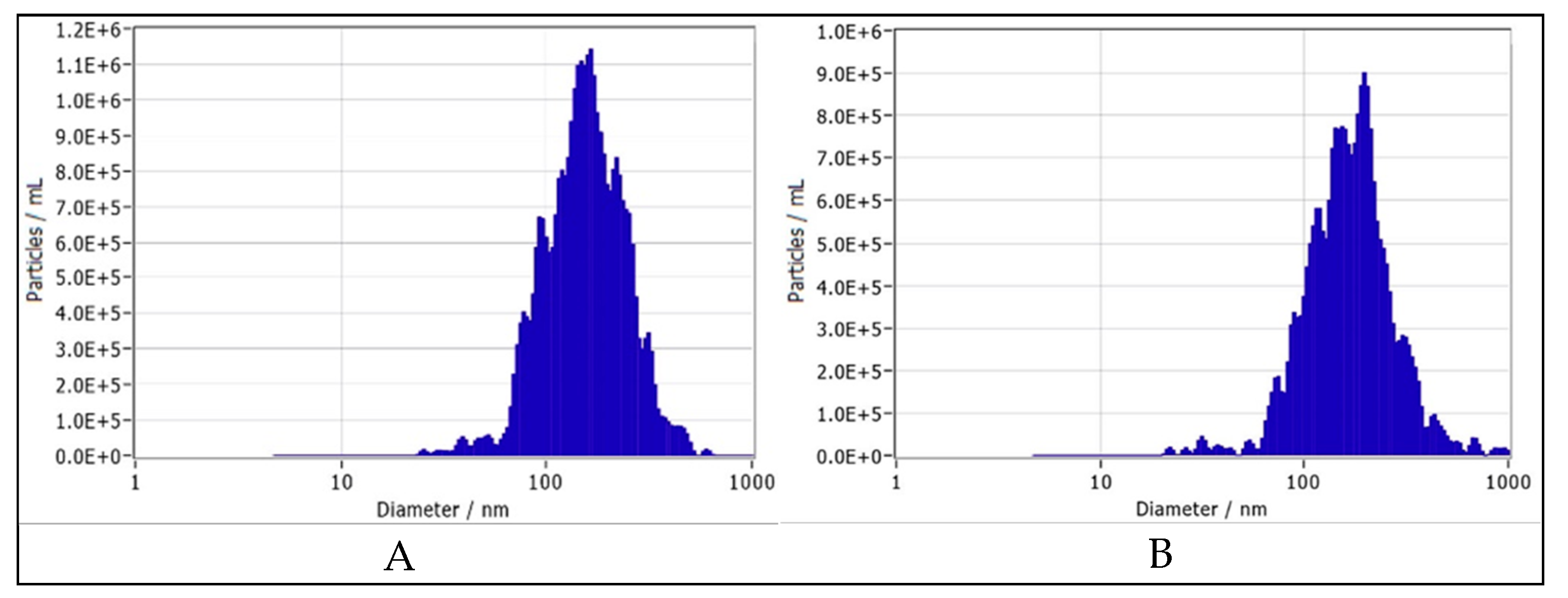

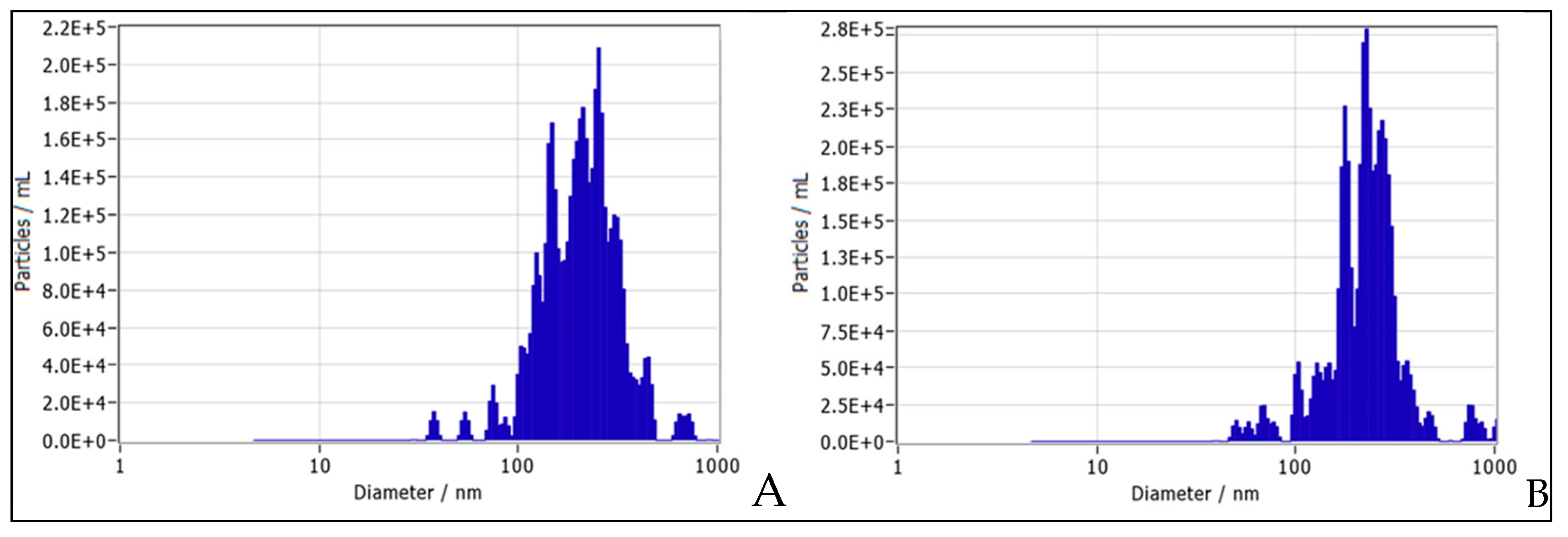

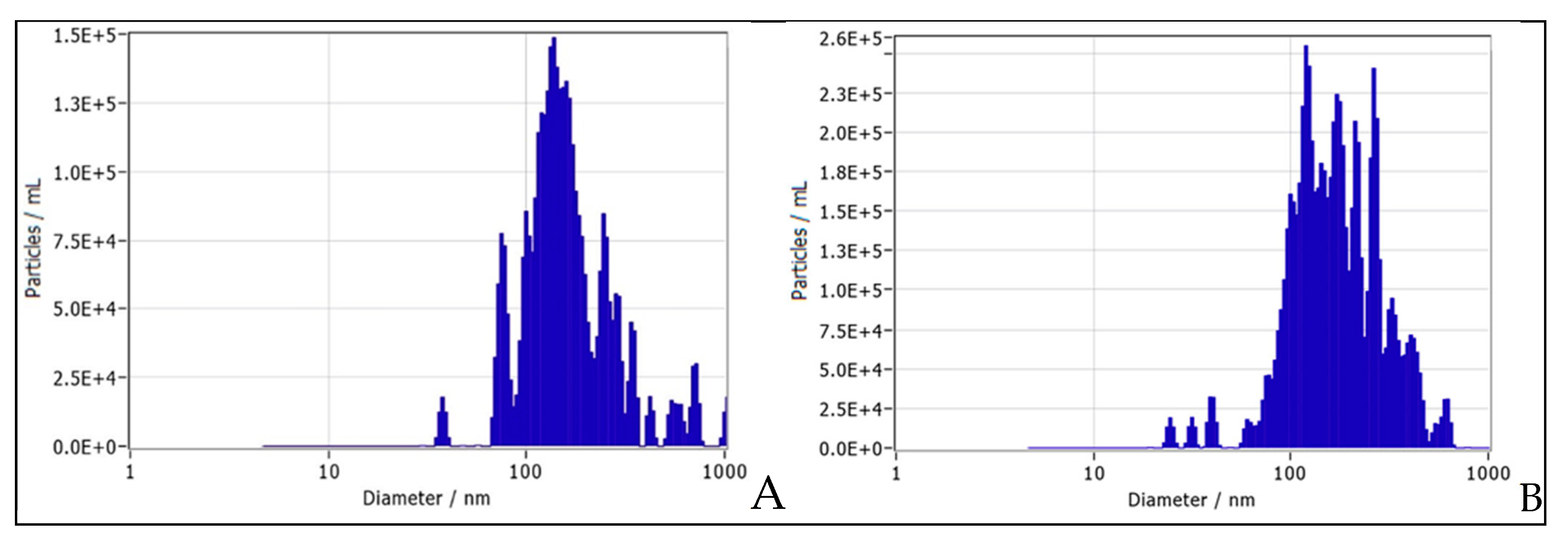

Figure 1 shows the size distribution of EC16 nanosuspensions prepared using Method I and with a food grade dispersing agent. The median size of the EC16 nanoparticles was152.5 + 78.8 nm, with a range of 95 to 218 nm. At 0.01% w/v EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 3.2x109 particles/ml, and the Zeta potential was -60.11 ± 0.59 mV (Fig 1A). When the dispersing agent was added to the water suspension, the median size of the nanoparticles became 163.8 ± 104.2 nm, ranging from 74 to 435 nm. At 0.01% w/v EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 2.4x109 particles/ml, and the Zeta potential was -58.08 + 0.55 mV (Fig 1B).

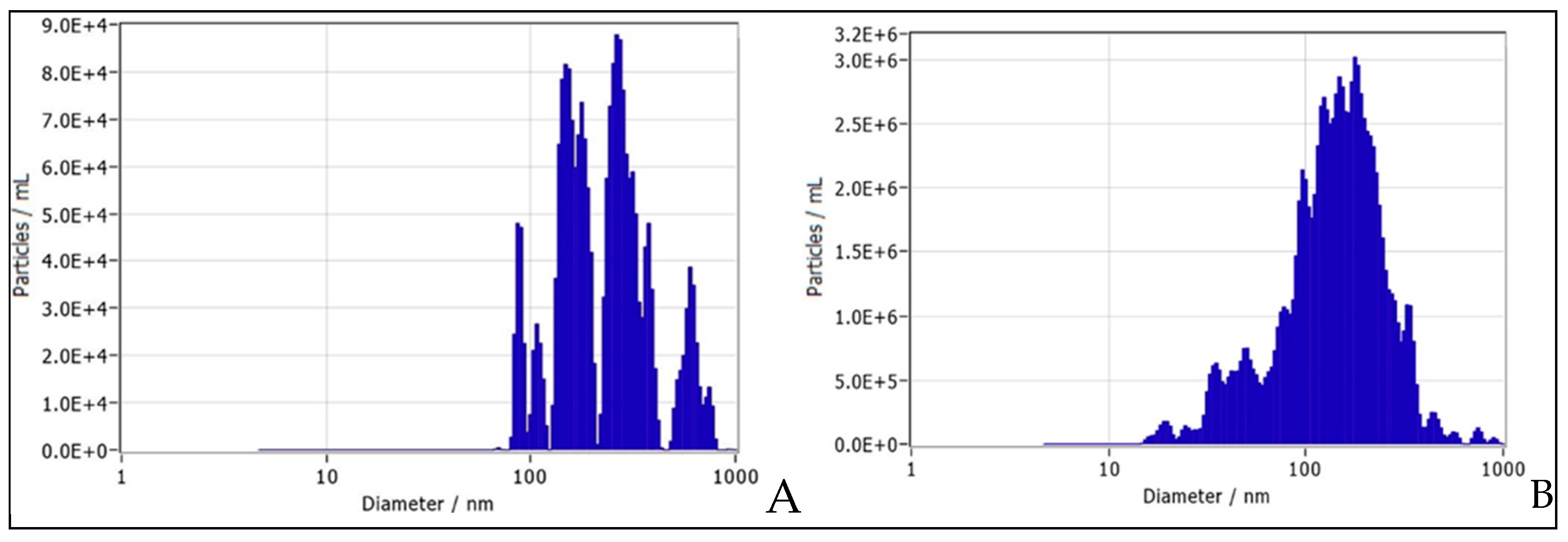

When EC16 nanoparticles were prepared by Method II, the median size of the nanoparticles was 128.1 nm, ranging from 66 to 143.9 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles is 1x1010 particles/ml and the Zeta potential was -56.65 mV (Fig 2A). With the addition of the dispersing agent, the median size of the nanoparticles was 147.7 nm, ranging from 57.8 to 162.1 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles is 6.5x109 particles/ml, and the Zeta potential was -55.22 mV (Fig 2B).

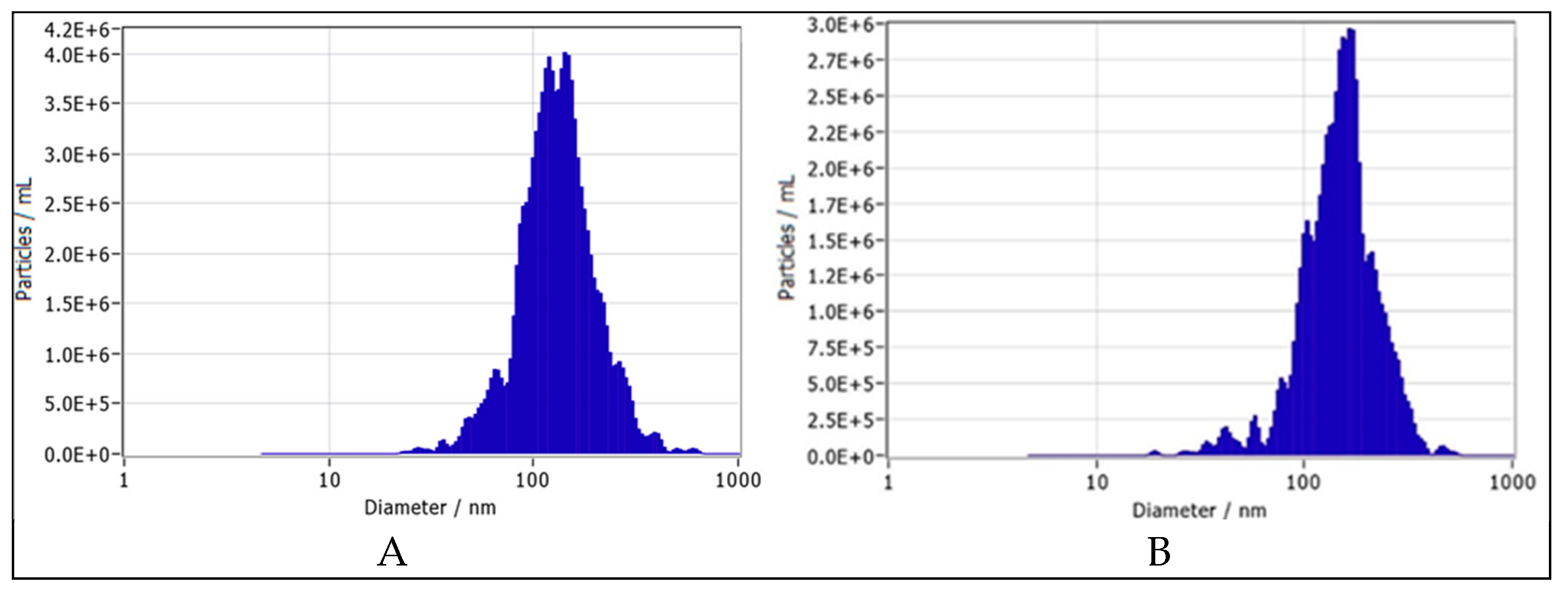

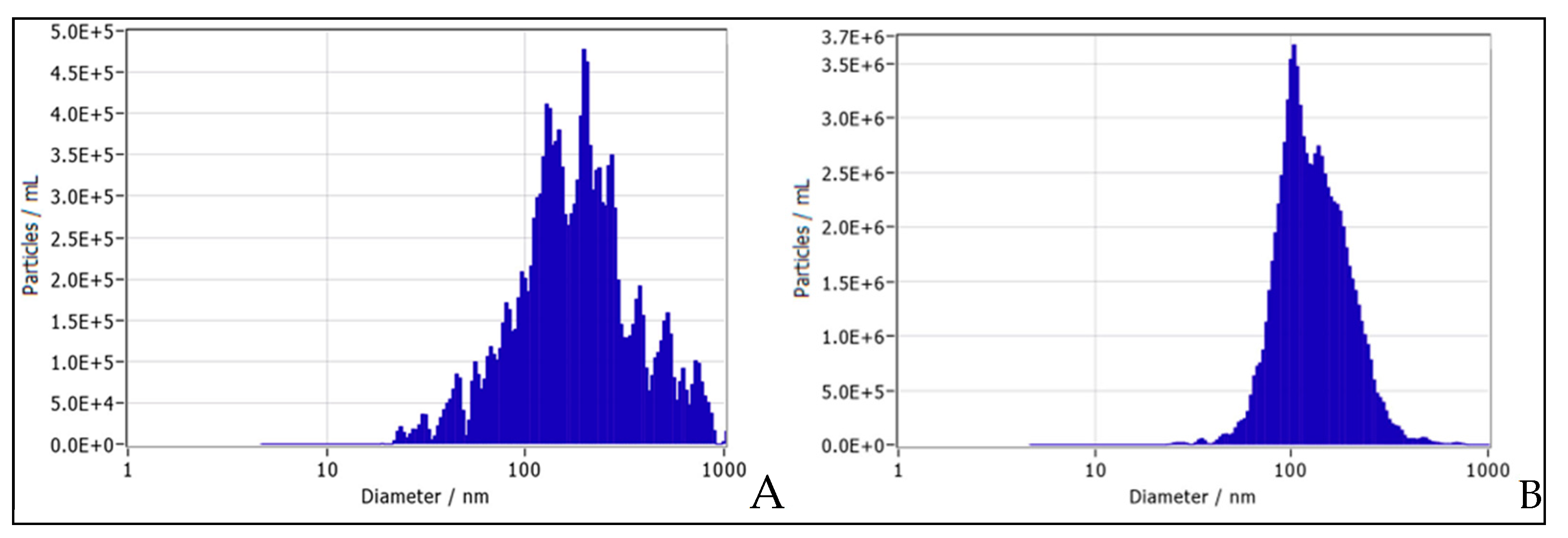

Method III was used in all previously published data and for EC16m preparation (Fig 3). The median size of EC16m nanoparticles was 115.9 nm, ranging from 30 to 120.9 nm. At 0.02% EC16m, the density of the nanoparticles was 2.3x1010 particles/ml, with Zeta potential of -50.33 mV (Fig 3A). With the addition of the dispersing agent, the median size of the nanoparticles was 154.9 nm, ranging from 65 to 182.5 nm. At 0.03% EC16m, the density of nanoparticles was 4.8x109 particles/ml, and the Zeta potential was -60.56 mV (Fig 3B).

3.2. CBD Nanoparticles

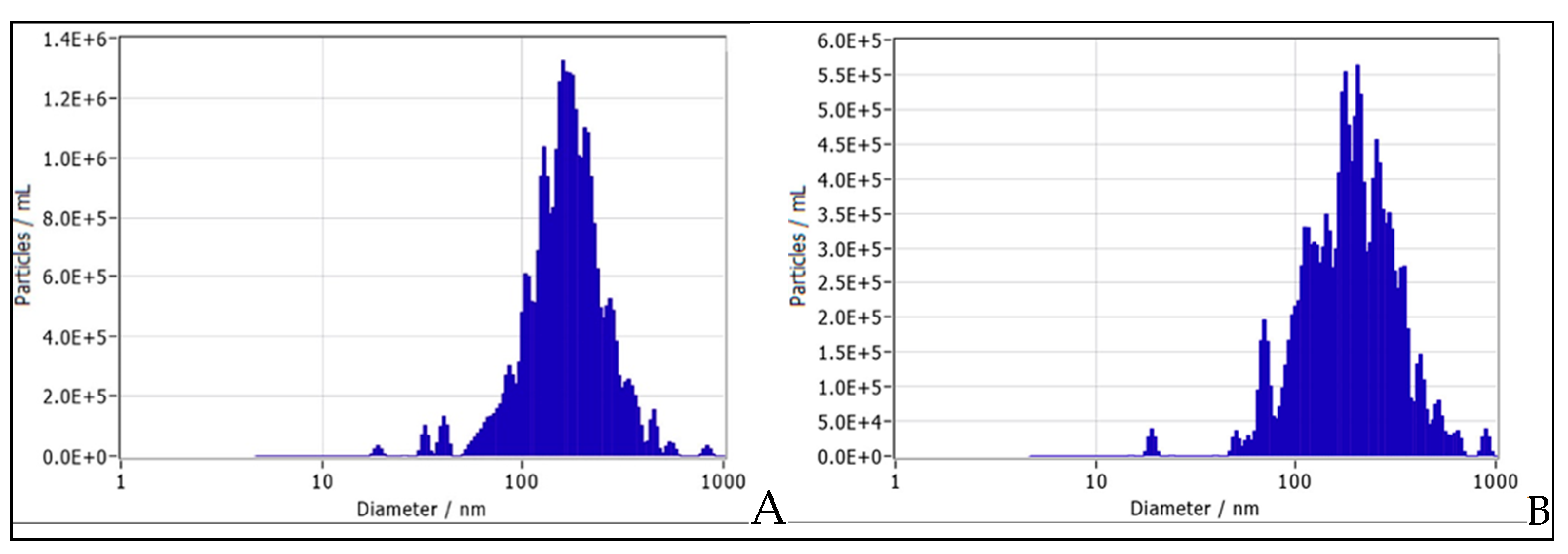

The median size of CBD nanoparticles is 206 nm, ranging from 147 to 438 nm. At 0.06% CBD, the density of the nanoparticles was 4.7x108 particles/ml and the Zeta potential was -51 mV (Fig 4A). With inclusion of 1% w/v of the dispersing agent, the median size of nanoparticles was 232.3 nm, ranging from 69 to 271.9 nm. At 0.06% CBD, the density of nanoparticles was 4.7x108 particles/ml and the Zeta potential was -48.09 mV (Fig 4B).

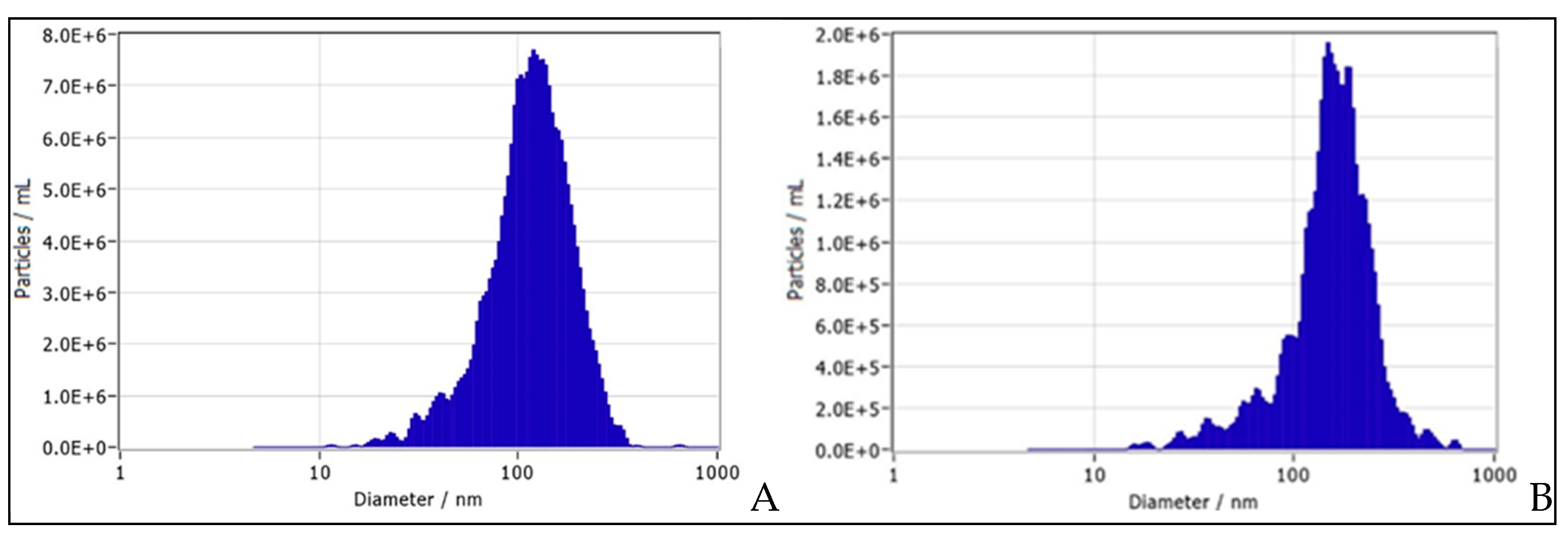

3.3. THC-9 and Reconstituted EC16 Nanoparticles

The median size of the THC-9 nanoparticles was 232.3 nm, ranging from 149 to 605 nm. At 0.01% CBD the density of the nanoparticles is 2.2x108 particles/ml, and the Zeta potential was -38 mV (Fig 5A). The median size of the water-reconstituted EC16 nanoparticles was 141.4 nm, ranging from 49 to 178.9 nm. At 0.01% EC16 the density of nanoparticles was 1010 particles/ml and Zeta potential was -56 mV (Fig 5B).

3.4. Size and Distribution of Quercetin Nanoparticles

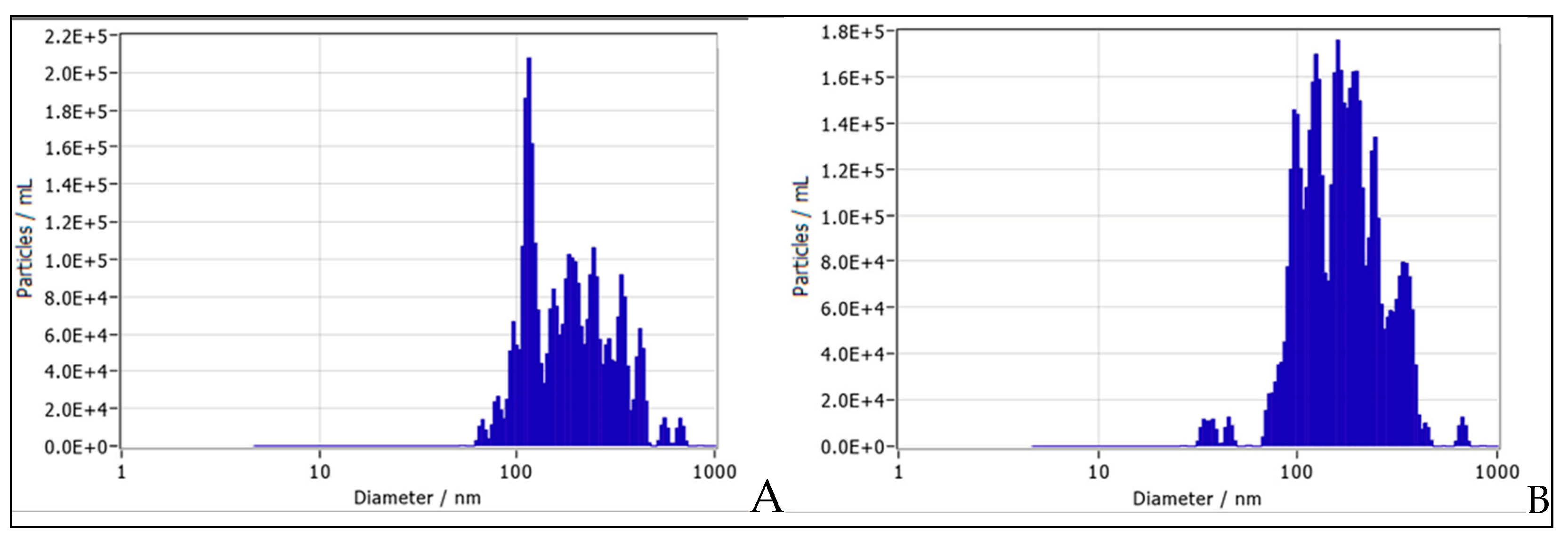

The median size of quercetin nanoparticles was 163.8 nm, ranging from 40 to 269.8 nm. At 0.02% w/v quercetin the density of the nanoparticles was 3.2x109 particles/ml, and the Zeta potential was -62 mV (Fig 6A). With 1% w/v of the dispersing agent the median size of nanoparticles was 184.9 nm, ranging from 69.6 to 256 nm. At 0.02% w/v quercetin the density of nanoparticles was 1.9x109 particles/ml and the Zeta potential was -38.4 mV (Fig 6B).

3.5. Size and Distribution of IVERMECTIN Nanoparticles

The median size of ivermectin nanoparticles was 176 nm, ranging from 115 to 420.7 nm. At 0.02% w/v ivermectin the density of the nanoparticles is 3.5x108 particles/ml with Zeta potential of -52.32 mV (Fig 7A). With 1% w/v of the dispersing agent the median size of nanoparticles was 160.6 nm, ranging from 98 to 344.5 nm. At 0.02% w/v ivermectin, the density of nanoparticles was 5x108 particles/ml and the Zeta potential was -53.92 mV (Fig 7B).

3.6. Size and Distribution of Retinoic Acid Nanoparticles

The median size of retinoic acid nanoparticles was 147 nm, ranging from 75.5 to 341.5 nm. At 0.02% w/v retinoic acid, the density of nanoparticles was 3.7x108 particles/ml, and the Zeta potential was -48.34 mV (Fig 8A). With 1% w/v of the dispersing agent the median size of nanoparticles was 162.8 nm, ranging from 120.3 to 407.3 nm. At 0.02% w/v retinoic acid the density of nanoparticles was 7.2x108 particles/ml and the Zeta potential was -53.99 mV (Fig 8B).

3.7. Size and Distribution of EC16 Nanoparticles in Two Water-Based Oral Rinse Formulations

The median size of the nanoparticles in unflavored oral rinse formulation was 176.7 nm, ranging from 81 to 268 nm. At 0.01% w/v EC16 the density of the nanoparticles is 1.6x109 particles/ml and the Zeta potential was -39 mV (Fig 9A). In the peppermint flavored oral rinse formulation, the median size of nanoparticles was 121.6 nm, ranging from 103 to 126.9 nm. At 0.01% w/v EC16, the density of nanoparticles was 8.6E+8.0 particles/ml with Zeta potential of -51.54 mV.

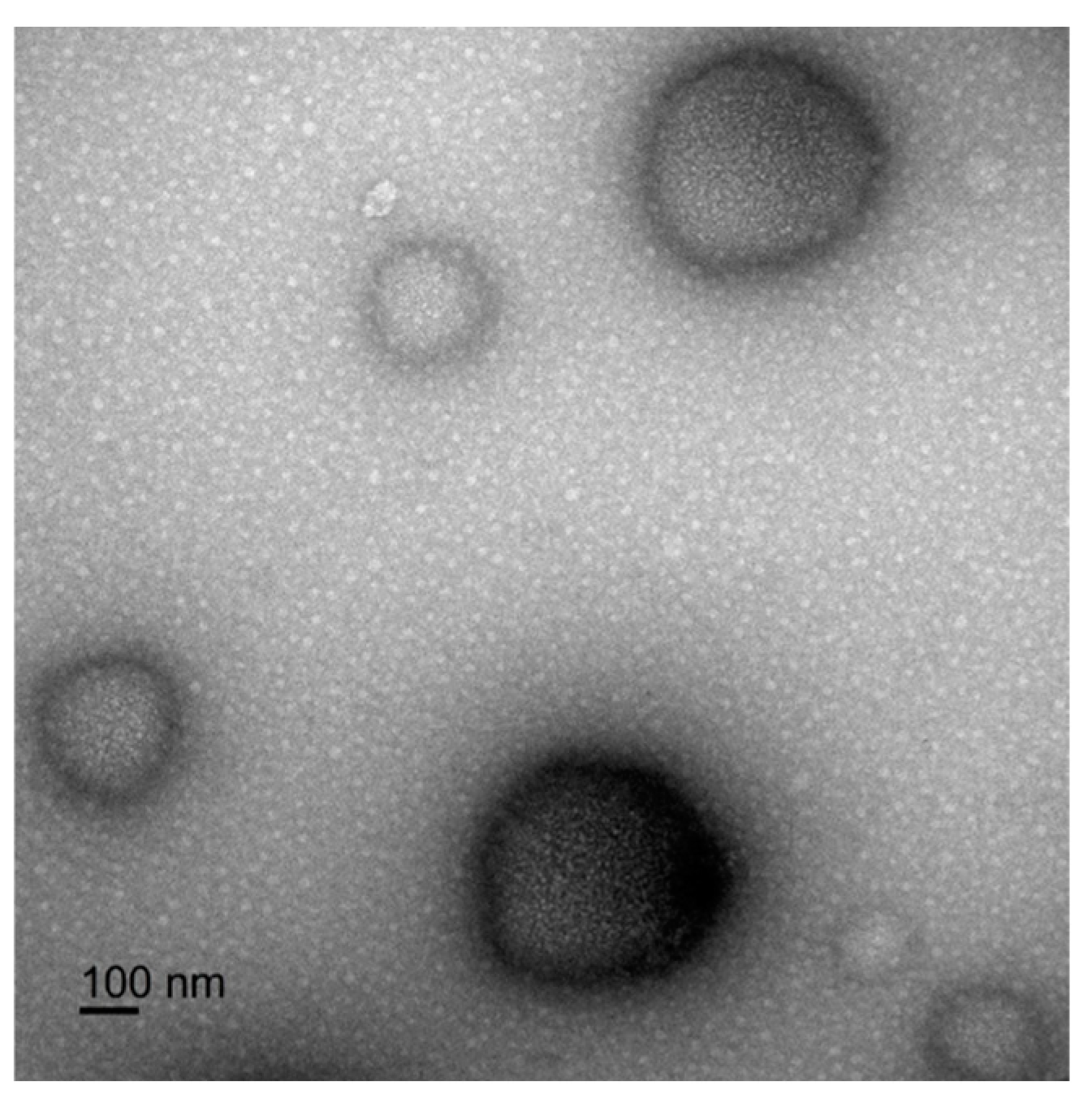

3.8. Transmission Electron Microscopy Image of EC16 Nanoparticles

Figure 10 shows a representative TEM image of an EC16 nanoparticle suspension fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde. The particle sizes ranged from approximately 100 nm to >300 nm, which is consistent with the EC16 nanoparticles prepared by Method III [4-6].

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

Figure 1.

Size and distribution of EC16 nanoparticles. A. Preparation method I. The median size of the nanoparticles was 152.5 nm, with a range from 95 to 218 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 3.2x 109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -60.11 mV. B. Preparation method I with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 163.8 nm, with a range from 74 to 435 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 2.4x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -58.08 mV.

Figure 1.

Size and distribution of EC16 nanoparticles. A. Preparation method I. The median size of the nanoparticles was 152.5 nm, with a range from 95 to 218 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 3.2x 109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -60.11 mV. B. Preparation method I with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 163.8 nm, with a range from 74 to 435 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 2.4x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -58.08 mV.

Figure 2.

Size and distribution of EC16 nanoparticles. A. Preparation method II. The median size of the nanoparticles was 128.1 nm, with a range from 66 to 143.9 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 1x1010 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -56.65 mV. B. Preparation method II with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 147.7 nm, with a range from 57.8 to 162.1 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 6.5x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -55.22 mV.

Figure 2.

Size and distribution of EC16 nanoparticles. A. Preparation method II. The median size of the nanoparticles was 128.1 nm, with a range from 66 to 143.9 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 1x1010 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -56.65 mV. B. Preparation method II with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 147.7 nm, with a range from 57.8 to 162.1 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the nanoparticles was 6.5x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -55.22 mV.

Figure 3.

Size and distribution of EC16m nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles was 115.9 nm, ranging from 30 to 120.9 nm. At 0.02% EC16m, the density of the nanoparticles was 2.3x1010 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -50.33 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 154.9 nm, ranging from 65 to 182.5 nm. At 0.03% EC16m, the density of nanoparticles was 4.8x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -60.56 mV.

Figure 3.

Size and distribution of EC16m nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles was 115.9 nm, ranging from 30 to 120.9 nm. At 0.02% EC16m, the density of the nanoparticles was 2.3x1010 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -50.33 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 154.9 nm, ranging from 65 to 182.5 nm. At 0.03% EC16m, the density of nanoparticles was 4.8x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -60.56 mV.

Figure 4.

Size and distribution of CBD nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles was 206 nm, ranging from 147 to 438 nm. At 0.06% CBD, the density of the nanoparticles was 4.7x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -51 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 232.3 nm, ranging from 69 to 271.9 nm. At 0.06% CBD, the density of nanoparticles was 4.7x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -48.09 mV.

Figure 4.

Size and distribution of CBD nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles was 206 nm, ranging from 147 to 438 nm. At 0.06% CBD, the density of the nanoparticles was 4.7x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -51 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 232.3 nm, ranging from 69 to 271.9 nm. At 0.06% CBD, the density of nanoparticles was 4.7x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -48.09 mV.

Figure 5.

Size and distribution of THC-9 nanoparticles and EC16 nanoparticles reconstituted from died powder. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the THC-9 nanoparticles was 232.3 nm, ranging from 149 to 605 nm. At 0.01% w/v THC-9, the density of the nanoparticles was 2.2x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -38 mV. B. Preparation method III. The median size of the water-reconstituted EC16 nanoparticles was 141.4 nm, ranging from 49 to 178.9 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of nanoparticles was 1x1010 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -56 mV.

Figure 5.

Size and distribution of THC-9 nanoparticles and EC16 nanoparticles reconstituted from died powder. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the THC-9 nanoparticles was 232.3 nm, ranging from 149 to 605 nm. At 0.01% w/v THC-9, the density of the nanoparticles was 2.2x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -38 mV. B. Preparation method III. The median size of the water-reconstituted EC16 nanoparticles was 141.4 nm, ranging from 49 to 178.9 nm. At 0.01% EC16, the density of nanoparticles was 1x1010 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -56 mV.

Figure 6.

Size and distribution of quercetin nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles was 163.8 nm, ranging from 40 to 269.8 nm. At 0.02% quercetin, the density of the nanoparticles was 3.2x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -62 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 184.9 nm, ranging from 69.6 to 256 nm. At 0.02% quercetin, the density of nanoparticles was 1.9x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -38.4 mV.

Figure 6.

Size and distribution of quercetin nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles was 163.8 nm, ranging from 40 to 269.8 nm. At 0.02% quercetin, the density of the nanoparticles was 3.2x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -62 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 184.9 nm, ranging from 69.6 to 256 nm. At 0.02% quercetin, the density of nanoparticles was 1.9x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -38.4 mV.

Figure 7.

Size and distribution of Ivermectin nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles is 176 nm, ranging from 115 to 420.7 nm. At 0.02% ivermectin, the density of the nanoparticles is 3.5x108 particles/ml. Zeta potential is -52.32 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of nanoparticles is 160.6 nm, ranging from 98 to 344.5 nm. At 0.02% ivermectin, the density of nanoparticles is 5x108 particles/ml. Zeta potential is -53.92 mV.

Figure 7.

Size and distribution of Ivermectin nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles is 176 nm, ranging from 115 to 420.7 nm. At 0.02% ivermectin, the density of the nanoparticles is 3.5x108 particles/ml. Zeta potential is -52.32 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of nanoparticles is 160.6 nm, ranging from 98 to 344.5 nm. At 0.02% ivermectin, the density of nanoparticles is 5x108 particles/ml. Zeta potential is -53.92 mV.

Figure 8.

Size and distribution of retinoic acid nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles was 147 nm, ranging from 75.5 to 341.5 nm. At 0.02% ivermectin, the density of the nanoparticles was 3.7x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -48.34 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 162.8 nm, ranging from 120.3 to 407.3 nm. At 0.02% ivermectin, the density of the nanoparticles was 7.2x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -53.99 mV.

Figure 8.

Size and distribution of retinoic acid nanoparticles. A. Preparation method III. The median size of the nanoparticles was 147 nm, ranging from 75.5 to 341.5 nm. At 0.02% ivermectin, the density of the nanoparticles was 3.7x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -48.34 mV. B. Preparation method III with addition of a food-grade dispersing agent. The median size of the nanoparticles was 162.8 nm, ranging from 120.3 to 407.3 nm. At 0.02% ivermectin, the density of the nanoparticles was 7.2x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -53.99 mV.

Figure 9.

Size and distribution of EC16 nanoparticles in two water-based oral rinse formulations. A. Unflavored oral rinse. The median size of the nanoparticles was 176.7 nm, ranging from 81 to 268 nm. At 0.01% EC16 w/v, the density of the nanoparticles was 1.6x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -39 mV. B. Peppermint oral rinse. The median size of nanoparticles was 121.6 nm, ranging from 103 to 126.9 nm. At 0.01% EC16 nanoparticles, the density of nanoparticles was 8.6x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -51.54 mV.

Figure 9.

Size and distribution of EC16 nanoparticles in two water-based oral rinse formulations. A. Unflavored oral rinse. The median size of the nanoparticles was 176.7 nm, ranging from 81 to 268 nm. At 0.01% EC16 w/v, the density of the nanoparticles was 1.6x109 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -39 mV. B. Peppermint oral rinse. The median size of nanoparticles was 121.6 nm, ranging from 103 to 126.9 nm. At 0.01% EC16 nanoparticles, the density of nanoparticles was 8.6x108 particles/ml. The Zeta potential was -51.54 mV.

Figure 10.

Representative transmission electron microscopy image of EC16 nanoparticles.

Figure 10.

Representative transmission electron microscopy image of EC16 nanoparticles.

4. Discussion

We previously reported that FAST Method III was used to produce EC16 and EC16m nanoparticles for nasal formulations [4-6]. To further explore other options to simplify the method, specific proprietary Methods I and II were used for EC16 nanoparticle preparation. In addition, an FDA approved, commonly used food additive dispersing agent was tested (proprietary, patent pending). Fig 1A shows the size distribution of EC16 nanoparticles in water suspension; Fig 1B is the size distribution of the water suspension with the dispersing agent at 1% w/v. There was no statistical difference in median size between the two formulations, but the dispersing agent altered the size range and resulted in smaller particles around 74 nm (10.1%) and 3.6% of larger particles around 435 nm; compared to the EC16 nanosuspension without the dispersing agent, which is ranging from 95 to 218 nm. Both nanosuspensions had excellent stability with Zeta potentials at about -60 mV (a Zeta Potential value above +30 mV or below −30 mV is generally considered stable). Therefore, FAST Method I was a suitable method to prepare EC16 nanoparticles.

Method II is another simplified method derived from Method III. As shown in Fig 2, the EC16 nanoparticles have a median size of 128.1 ± 65.9 nm, with a range of 66 to 143.9 nm (Fig 2A). while the dispersing agent resulted in a slightly larger median size of 147.7 + 63.8 nm, with similar size range 57.8 to 162.1 nm (Fig 2B). It appears that the dispersing agent had little effect on the nanoparticle size, and the charges measured by Zeta potentials were similar to each other (-56.65 ± 0.65 mV vs. -55.22 ± 0.88 mV), although slightly lower than those for particles produced by Method I. Also, both Method II suspensions had a narrower size range than that of EC16 nanosuspensions made with Method I (Fig 1), suggesting Method II can be used for producing EC16 nanoparticles with smaller range in size.

In summary, both Methods I and II simplified versions of Method III, are capable of producing EC16 nanoparticles with high stability, consistent with previously published data using Method III. It is important to note that all three methods are simple, economical, require a short time (<30 min), and little equipment.

Method III was used to prepare EC16m nanoparticles, as well nanosuspensions for all other compounds. As shown in Fig 3, Method III was able to produce EC16m nanoparticles with a narrow range (30 to 120.9 nm) (Fig 3A), compared to the nanoparticles in dispersing agent suspension (65 to 182.5 nm) (Fig 3B). The median size of particles was smaller in the suspension without dispersing agent (115.9 ± 57.5 nm) in comparison to the suspension with the dispersing agent (154.9 ± 77.7 nm). Interestingly, the EC16 nanosuspension without dispersing agent has significantly more nanoparticles than the nanosuspension with the dispersing agent (2.3x10

10 vs. 4.6x10

9/ml). However, it appears that the EC16 nanosuspension with the dispersing agent was potentially more stable, a with Zeta potential exceeding 60 mV. On the other hand, both nanosuspensions were potentially very stable, with Zeta potentials greater than 50 mV. We chose 0.02% EC16m and EC16 based on the previously tested nasal application formulations [

5], and two ongoing animal studies, all of which have this concentration of EC16m or EC16, and which did not show mucociliary toxicity [

5] of adverse effect.

For CBD nanoparticles (Fig 4), the dispersing agent reduced the range of particle size (69 to 271 nm vs. 147 to 438 nm) but increased the median size (232.3 ± 135.3 vs. 206 ± 103.4 nm) without statistical differences. Interestingly, the two CBD nanosuspensions with 0.06% CBD have identical particle density of 4.7x108 particles/ml, and a potentially high stability with a Zeta potential around -50 mV (Fig 4). Comparing to the EC16 nanoparticles, the CBD nanoparticles were larger in diameter, leading to a lower particle density. The stability of the two compounds in the nanosuspensions are similarly high.

A noticeable difference was found in the nanosuspension of THC-9 without the dispersing agent. As shown in Fig 5A, the median size of the particles (232.3 ± 151.3 nm) was similar to that of CBD. However, unlike the other compounds tested, the size distribution was discontinued, with four discrete subpopulations (Fig 5A). Although the nanosuspension was stable with a Zeta potential at -38 ± 0.51, this charge was significantly lower than that of other compounds. However, it is important to note that the THC-9 sample was in a methanol solution at a very low concentration, which was different from other compounds that were obtained in powdered form.

Different nanotechnology methods have been used to produce nanoparticles of both CBD and THC [

9]. The FAST-generated nanoparticles will provide an alternative approach.

To test if the nanoparticle powder produced by a FAST method can be easily reconstituted in water, an EC16 nanosuspension at 0.1% was condensed and dried, producing a white powder. The dry EC16 nanoparticles were then reconstituted in double distilled water as a nanosuspension. At 0.01% EC16, the density of the particles reached 1x1010 particles/ml, with median size of 141.4 ± 105.4 nm and size range from 49 to 178.9 nm (Fig 5B). The size distribution was comparable to that of EC16 nanoparticles prepared by Method II (Fig 2), as was the Zeta potential. This result demonstrates that EC16 nanoparticles can be condensed to a powder form and reconstituted in aqueous suspensions or in dry delivery forms. This process could be used for other compounds if dry powder form is needed.

A number of nanotechnologies have been applied to generate nanoparticles of quercetin, a flavonoid with poor solubility but the potential to benefit human health. Previous studies used lipid-based nanocarriers, polymer-based nanocarriers, micelles and hydrogels composed of natural or synthetic polymers to produce nanoparticles of quercetin [

10]. Fig 6 demonstrates that quercetin is suitable for nanosuspension preparation using Method III. The results from the two nanosuspensions indicate that the dispersing agent caused the suspension to have a less negative charge, potentially reducing stability (Zeta potential of -38.4 mV vs. -62 mV) and associated with decreased particle density (1.9x10

9 vs. 3.2x10

9/ml at 0.02%) in comparison to the nanosuspension without the dispersing agent. These differences suggest that the dispersing agent should not be used for quercetin nanosuspensions.

Ivermectin was initially used as a veterinary medicine for treating parasite infections, but consistently faced limitations due to its poor water solubility and low bioavailability. Various strategies have been applied to increase the solubility of this drug, including lipid-based, polymer-based, drug-loaded nanoparticles, and nanostructured carriers [

11].

In the current study, the results demonstrate that both tested nanosuspensions of ivermectin had identical Zeta potentials (Fig 7). The particle size distributions were different. In the nanosuspension with the dispersing agent only 14.2% of particles had diameters greater than 200 nm, while the counterpart has more than 35% particles with diameters greater than 200 nm. This effect of the dispersing agent resulted in significantly more particles (5x108/ml) in the presence of the dispersing agent compared to the suspension without the agent (3.5x108/ml) at 0.02% w/v ivermectin (Fig 7). Therefore, the addition of the dispersing agent is dependent on the specific compound for its benefit.

Retinoids present considerable potential to treat multiple conditions, but one of the major challenges is their low solubility. Attempts were made to produce nanoparticles of retinoic acid, including encapsulation in other nanoparticles, micelles, liposomes, films, or by attaching to a carrier [

12]. Retinoic acid has a hydrocarbon chain and 6-carbin ring, similar to EC16, EC16m, CBD, and THC. Despite the carboxylic acid group is charged at pH 7, retinoic acid is hydrophobic with poor water solubility. The current study demonstrates that these chemical properties did not prevent retinoic acid from being self-assembled into nanoparticles using FAST Method III (Fig 8). The dispersing agent gave a similar Zeta potential (-54 mV) to that of nanosuspension without the dispersing agent (-48.34 mV). Another advantage of using the dispersing agent is that the particle density almost doubled (7.2x10

8 vs. 3.7x10

8/ml) at 0.02% concentration. By shifting the distribution from larger to smaller particles as seen in Fig 8.

To determine the feasibility of using EC16 nanoparticles in oral care products we initially tested 0.05% and 0.005% w/v of EC16 nanoparticles in an unflavored oral rinse product containing erythritol, provided by International Nutrition, Inc. Both concentrations were stable and compatible with the oral rinse with particle size range of 40.7 to 251.4 nm, and median size of 170.6 ± 97.3 nm (data not shown). To further investigate the feasibility of EC16 nanoparticles, the 1% stock was directly added to two oral rinse products containing xylitol. One oral rinse also contains natural peppermint flavor. As shown in Fig 9A, the unflavored oral rinse with EC16 nanoparticles has a similar size distribution with the previously tested unflavored product, with more than 60% particles under 200 nm, resulting in a high density of 1.6x109 particles/ml at 0.01% EC16. In contrast, the peppermint oral rinse with EC16 nanoparticles is highly stable with Zeta potential of -51.54 mV. In addition, the particle range is narrow, with most particles at around 100 to 130 nm range. These results demonstrate that EC16 nanoparticles can be easily incorporated into aqueous products with high stability.

To investigate the EC16 nanoparticle structure after the self-assembling process, transmission electron microscopy was performed after EC16 nanoparticles in suspension was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde. Fig 10 shows seven nanoparticles with high polydispersity, with diameters ranging from approximately 100 nm to >300 nm. The characters of EC16 nanoparticles were described in a recent publication [

8]. It is postulated that other compounds in the current study would have similar particle structures and characteristics, pending future studies. The limitations of FAST include 1: It is only for hydrophobic and poorly soluble molecules; 2: it may not be suitable for large compounds.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the invention of the Facilitated Self-assembling Technology (FAST) would allow compounds with poor solubility and bioavailability to form nanoparticles by themselves to either suspend in an aqueous formulation or in a dried powder form for a variety of delivery methods such as oral, nasal, topical, injectable, etc. Methods based on FAST can be used in drug development and drug improvement, as well as for healthcare, disease control and prevention, cosmetic, and consumer products, pending future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., D.D.; methodology, S.H., N.F., Zeta View validation, Y.L., H.Y., J.C. and N.F.; data analysis, S.H., D.D., N.F.; investigation, N.F., D.D., and S.H.; re-sources, Y.L.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, N.F.; D.D.; visualization, N.F.; supervision, S.H. and D.D.; project administration, S.H.; funding acquisition, S.H., D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) (1R41DC020678-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dr. Brenden Marshal for TEM work and support from Augusta University Research Institute and Office of Innovation Commercialization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ogden, J.; Parry-Billings, M. Nanotechnology approaches to solving the problems of poorly water-soluble drugs. Drug Discov 2005, 6:71–76.

- Kumari, L.; Choudhari, Y.; Patel, P.; Gupta, G.D.; Singh, D.; Rosenholm, J.M.; Bansal, K.K.; Kurmi, B.D. . Advancement in Solubilization Approaches: A Step towards Bioavailability Enhancement of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Life (Basel) 2023, 13:1099.

- Bhalani, D.V.; Nutan, B.; Kumar, A.; Chandel, A.K.S. Bioavailability Enhancement Techniques for Poorly Aqueous Soluble Drugs and Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022, 10:2055.

- Frank, N.; Dickinson, D.; Garcia, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Cai, J.; Patel, S.; Yao, B.; Jiang, X.; Hsu, S. . Feasibility Study of Developing a Saline-Based Antiviral Nanoformulation Containing Lipid-Soluble EGCG: A Potential Nasal Drug to Treat Long COVID. Viruses 2024, 16:196.

- Frank, N.; Dickinson, D.; Lovett, G.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Cai, J.; Yao, B.; Jiang, X.; Hsu, S. Evaluation of Novel Nasal Mucoadhesive Nanoformulations Containing Lipid-Soluble EGCG for Long COVID Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16:791.

- Frank, N.; Dickinson, D.; Garcia, W.; Xiao, L.; Xayaraj, A.; Lee, L.; Chu, T.; Kumar, M.; Stone, S.; Hsu, S. Evaluation of Aqueous Nanoformulations of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate-Palmitate (EC16) Against Human Coronavirus as a Potential Intervention Drug. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res 2023, 50:2023.

- Hurst, B.L.; Dickinson, D.; Hsu, S. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) Inhibits Sars-Cov-2 Infection in Primate Epithelial Cells. Microbiol Infect Dis 2021, 5: 1-6.

- Frank, N.; Dickinson, D.; Dudish, D.; James, W.; Lovett, G.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Cai, J.; Yao, B.; Jiang, X.; Hsu, S. Potential Therapeutic Use of EGCG-Palmitate Nanoparticles for Norovirus Infection. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res 2024, 59:2024.

- Rebelatto, E.R.L.; Rauber, G.S.; Caon, T. An update of nano-based drug delivery systems for cannabinoids: Biopharmaceutical aspects & therapeutic applications. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 635:122727.

- Tomou, E.M.; Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Elmina-Marina Saitani, E.M.; Georgia Valsami, G.; Pippa, N.; Skaltsa, H. Recent Advances in Nanoformulations for Quercetin Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15:1656.

- Maiara Callegaro Velho, M.C.; Funk, N.L.; Deon, M.; Benvenutti, E.V.; Buchner, S.; Hinrichs, R.; Diogo André Pilger, D.A.; Ruy Carlos Ruver Beck, R.C.R. Ivermectin-Loaded Mesoporous Silica and Polymeric Nanocapsules: Impact on Drug Loading, In Vitro Solubility Enhancement, and Release Performance. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16:325.

- Napoli, R.F.J. ; Tariq Enver, Liliana Bernardino, L.; Ferreira, L. Advances and challenges in retinoid delivery systems in regenerative and therapeutic medicine. Nature Communications 2020, 11: 4265.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).