Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

In recent years, deep network-based hashing has emerged as a prominent technique, especially within image retrieval by generating compact and efficient binary representations. However, many existing methods tend to solely focus on extracting semantic information from the final layer, neglecting valuable structural details that encode crucial semantic information. As structural information plays a pivotal role in capturing spatial relationships within images, we propose the enhanced image retrieval using Multiscale Deep Feature Fusion in Supervised Hashing (MDFF-SH), a novel approach that leverages multiscale feature fusion for supervised hashing. The balance between structural information and image retrieval accuracy is pivotal in image hashing and retrieval. Striking this balance ensures both precise retrieval outcomes and meaningful depiction of image structure. Our method leverages multiscale features from multiple convolutional layers, synthesizing them to create robust representations conducive to efficient image retrieval. By combining features from multiple convolutional layers, MDFF-SH captures both local structural information and global semantic context, leading to more robust and accurate image representations. Our model significantly improves retrieval accuracy, achieving higher Mean Average Precision (MAP) than current leading methods on benchmark datasets such as CIFAR-10, NUS-WIDE and MS-COCO with observed gains of 9.5%, 5% and 11.5%, respectively. This study highlights the effectiveness of multiscale feature fusion for high-precision image retrieval.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Dual-Scale Approach: We propose a dual-scale approach that considers both feature and image sizes to preserve semantic and spatial details. Moreover that compensates for the loss of high-level features and ensures the generated hash codes are more discriminative and informative.

- Multi-Scale Feature Fusion: MDFF-SH learns hash codes across multiple feature scales and fuses them to generate final binary codes, enhancing retrieval performance.

- End-to-End Learning: Our MDFF-SH model integrates joint optimization for feature representation and binary code learning within a unified deep framework.

- Superior Performance: Extensive experiments on three well-known datasets demonstrate that MDFF-SH surpasses state-of-the-art approaches in retrieval performance.

2. Related works

2.1. Problem Definition

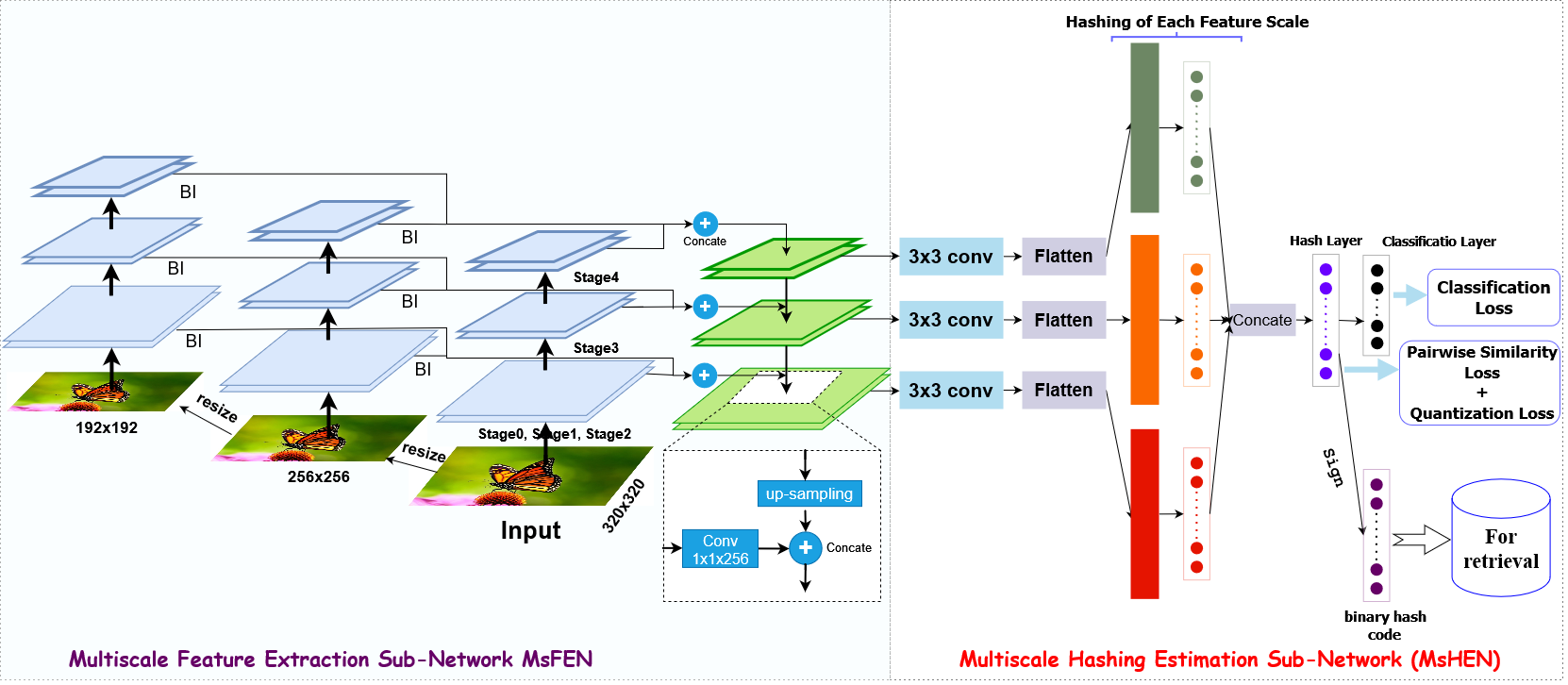

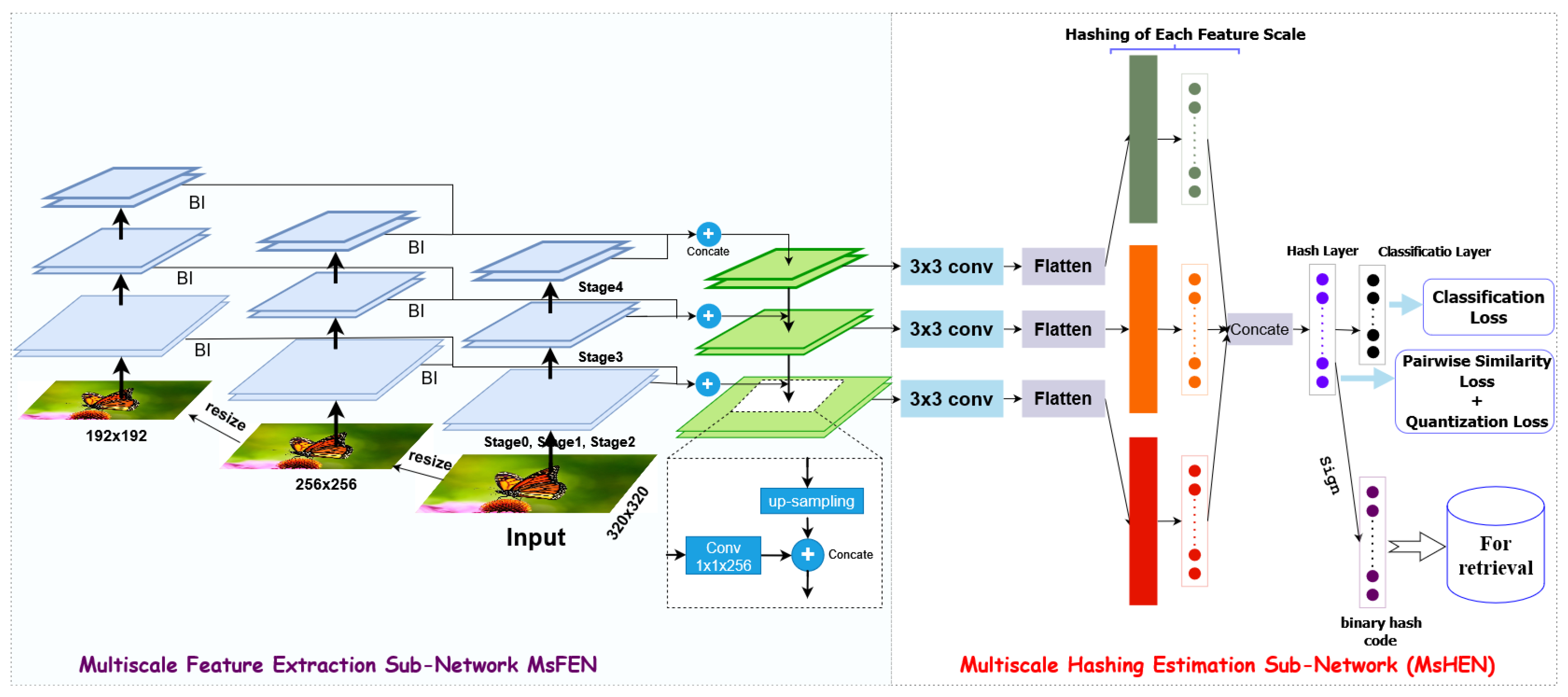

2.2. Model Architecture

-

Feature Extraction: The initial feature extraction stage is crucial for gathering informative details from the input image. In MDFF-SH, the ResNet50 network serves as the backbone due to its capability to capture complex and distinguishing image features. Each layer in ResNet50 is designed to capture image details at increasing levels of abstraction, making it an ideal foundation for extracting both structural and semantic features.MDFF-SH systematically collects features from distinct levels of ResNet50. This includes low-level features, capturing fine details such as edges and textures, and high-level features, encapsulating semantic attributes. This multi-level approach ensures that the image representation integrates both granular details and overall semantic meaning.

- Multiscale Feature Focus: The model’s multiscale feature extraction focuses on layers from several convolutional blocks—specifically, the final layers of ‘conv3’, ‘conv4’, and ‘conv5’ blocks, along with the fully connected layer fc1. Lower-level layers like ‘conv1’ and ‘conv2’ are excluded to optimize memory usage, as their semantic contribution is limited. The selected layers effectively capture a balanced mix of structural and semantic information, providing a comprehensive representation of the image that includes both low- and high-level characteristics.

- Feature Reduction: After extraction, the dimensionality of the multiscale features is reduced to retain discriminative power without excessive computational overhead. Using a 1x1 convolutional kernel, the model combines features across levels in a linear manner, creating a streamlined yet rich representation. This step enhances the depth and robustness of the features while minimizing redundancy.

- Feature Fusion: In the fusion stage, the reduced features from different levels are combined to produce a unified representation. By merging both low- and high-level information, the fusion layer enables the model to construct an image representation that captures local structures alongside global context. This fusion provides a robust basis for generating binary codes that reflect a detailed and semantically rich image profile.

- Hash Coding: To generate the final hash codes, the fused feature representation undergoes nonlinear transformations through hash layers, each of which outputs binary codes of the desired length L. This transformation ensures that the binary codes retain the core characteristics of the images in a compact and retrieval-optimized format.

-

Classification: The classification layer, which corresponds to the number of classes in the dataset, assigns the generated hash codes to specific image categories. This final component allows MDFF-SH to distinguish among classes based on learned binary representations, reinforcing the network’s retrieval effectiveness.Through this structured architecture presented in Table 1, MDFF-SH captures both local and global image information, resulting in a powerful and compact feature representation that is tailored to high-precision image retrieval.

2.3. Loss Functions and Learning Rule

2.3.1. Pairwise Similarity Loss

2.3.2. Quantization Loss

2.3.3. Classification Loss

3. Experiments

3.1. Datasets

3.2. Experimental Settings

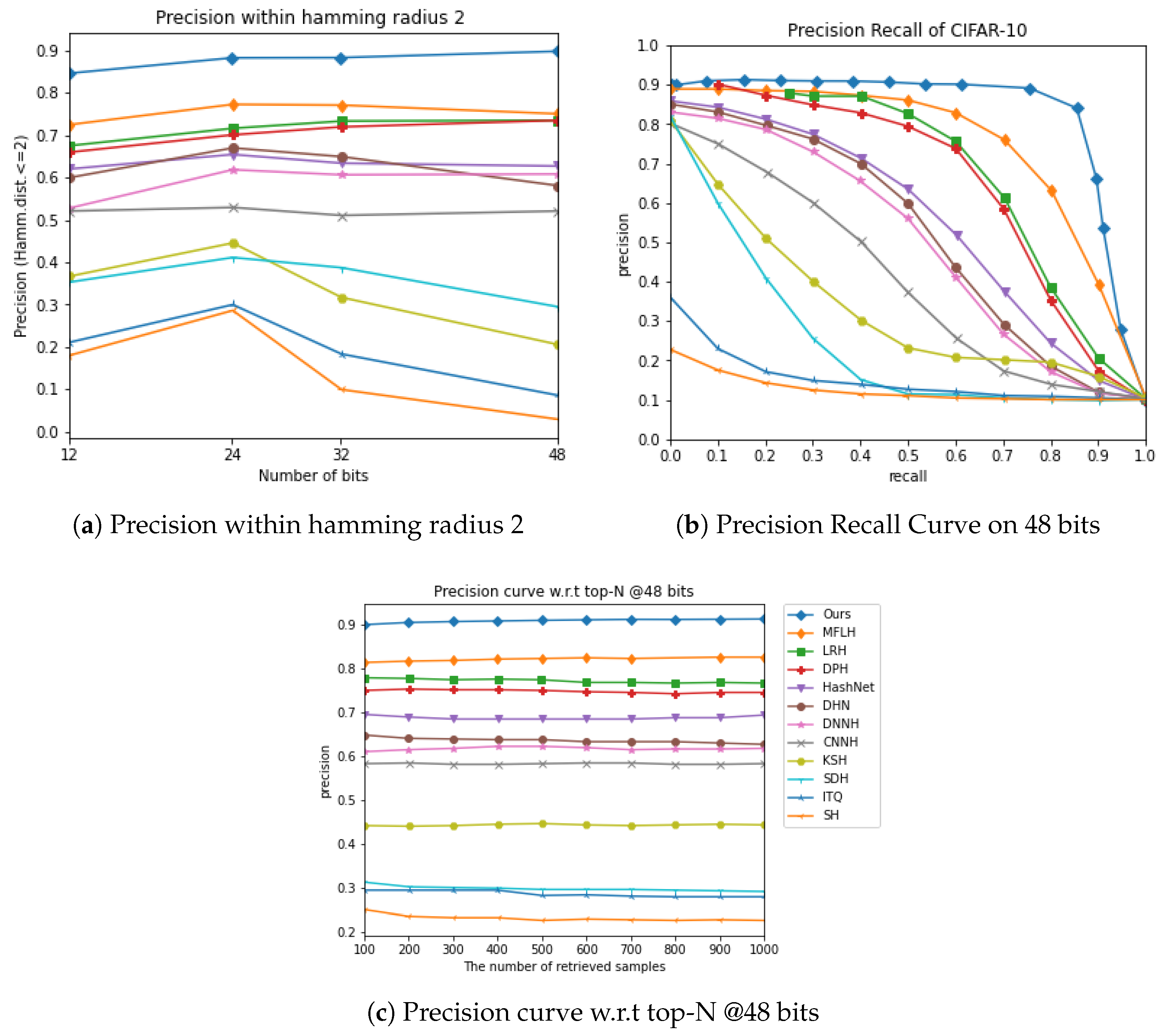

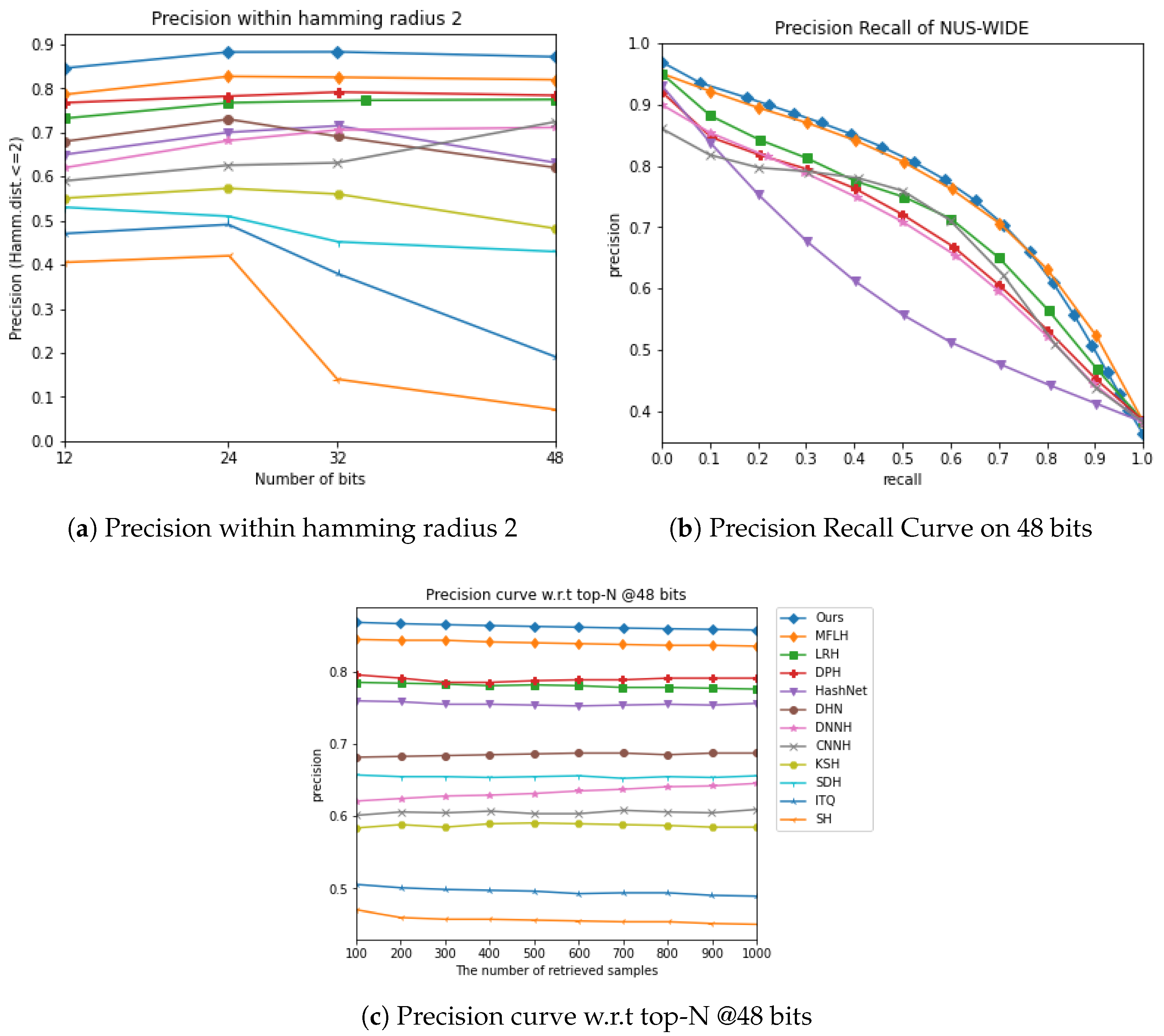

3.3. Evaluation Metrics and Baselines

- Mean Average Precision (MAP) results,

- Precision-Recall (PR) curves,

- Precision at top retrieval levels (P@N), and

- Precision within a Hamming radius of 2 (P@H ≤ 2).

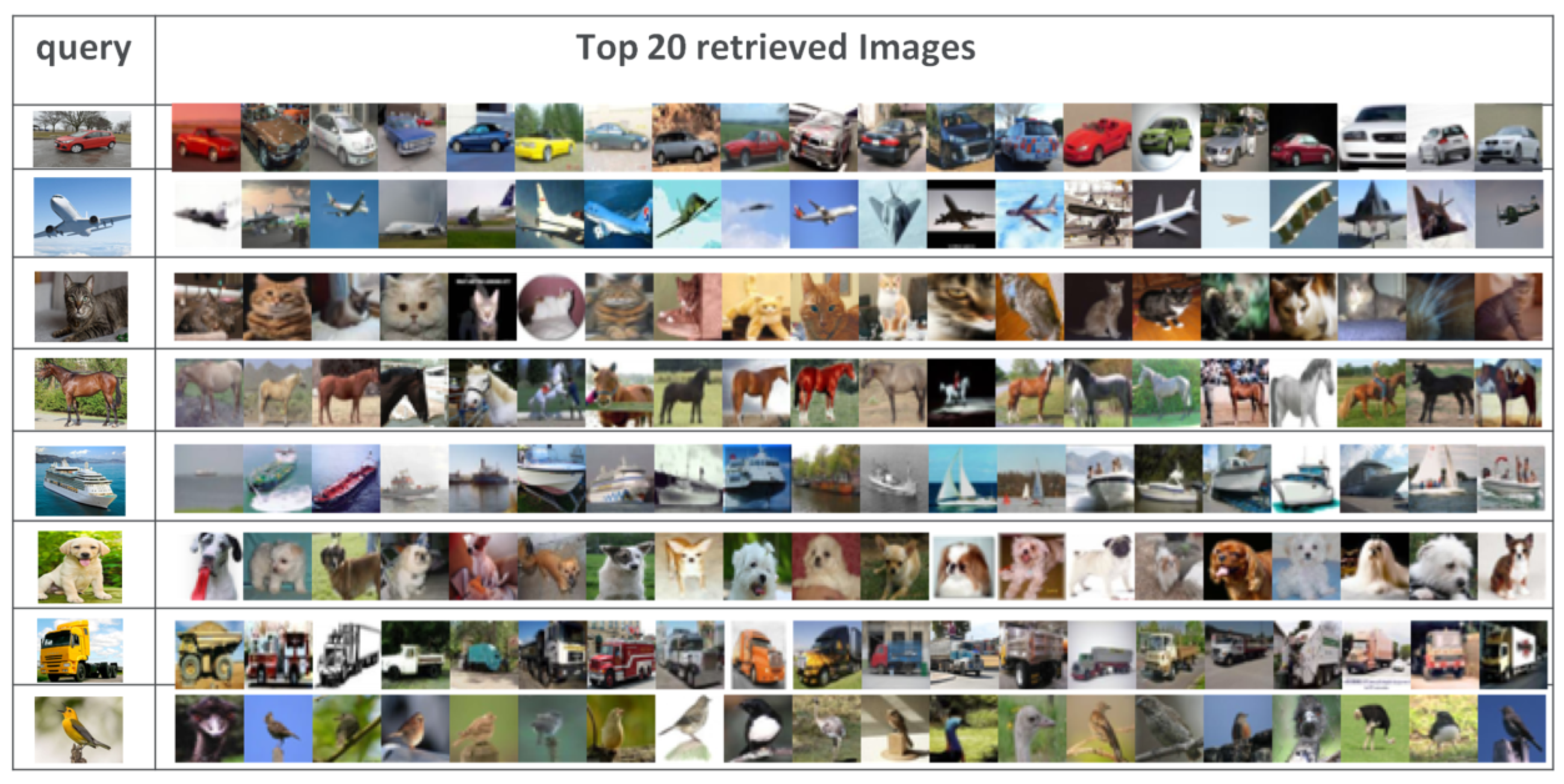

3.4. Results

3.5. Ablation Studies

- (1)

-

Ablation Studies on Multi-Level Image Representations for Enhanced Hash Learning: To investigate the impact of multi-level image representations on hash learning, we conducted ablation studies. Unlike many existing methods that primarily focus on semantic information extracted from the final fully connected layers, we explored the contribution of structural information from various network layers.Table 4 presents the retrieval performance on the CIFAR-10 dataset using different feature maps. We observed that features from the fc1 layer yielded the highest mAP of 75.8%, emphasizing the importance of high-level semantic information. However, using features from Conv 3-5 resulted in an average mAP of 62.5%, highlighting the significance of low-level structural details. Our proposed MDFF-SH approach outperformed all other configurations, achieving an average mAP of 85.5%, demonstrating the effectiveness of combining multi-scale features for enhanced retrieval performance.

- (2)

- Ablation Studies on the Objective Function: To assess the impact of different loss components in our objective function, we conducted ablation studies on the CIFAR-10 dataset using the MDFF-SH model. We evaluated the performance of the model when either the Pairwise Quantization Loss (, MDFF-SH-J3) or the Classification Loss (, MDFF-SH-J2) was excluded. As shown in Table 5, the inclusion of both J2 and J3 resulted in an 8.55% performance improvement. This finding highlights the importance of both quantization loss, which minimizes quantization error, and classification loss, which preserves semantic information, for generating high-quality hash codes.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDFF-SH | Multiscale Deep Feature Fusion for High-Precision Image Retrieval through Supervised Hashing |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DCNN | Deep Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Yan, C.; Shao, B.; Zhao, H.; Ning, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, F. 3D room layout estimation from a single RGB image. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2020, 22, 3014–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y. Depth image denoising using nuclear norm and learning graph model. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMM) 2020, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. Unsupervised variational video hashing with 1d-cnn-lstm networks. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2019, 22, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gionis, A.; Indyk, P.; Motwani, R. ; others. Similarity search in high dimensions via hashing. Vldb, 1999, Vol. 99, pp. 518–529.

- Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Sebe, N.; Shen, H.T.; et al. A survey on learning to hash. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2017, 40, 769–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin Liong, V.; Lu, J.; Wang, G.; Moulin, P.; Zhou, J. Deep hashing for compact binary codes learning. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 2475–2483.

- Zhu, H.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y. Deep hashing network for efficient similarity retrieval. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2016, Vol. 30.

- Lai, H.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yan, S. Simultaneous feature learning and hash coding with deep neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 3270–3278.

- Cakir, F.; He, K.; Bargal, S.A.; Sclaroff, S. Hashing with mutual information. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2019, 41, 2424–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Sun, Z.; He, R.; Tan, T. Deep supervised discrete hashing. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, C.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Han, Z.; Wen, Q. Deep quantization network for efficient image retrieval. Proc. 13th AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., 2016, pp. 3457–3463.

- Li, W.J.; Wang, S.; Kang, W.C. Feature learning based deep supervised hashing with pairwise labels. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.03855. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Liong, V.E.; Zhou, J. Deep hashing for scalable image search. IEEE transactions on image processing 2017, 26, 2352–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, Z.; Tang, J. Discriminative Deep Hashing for Scalable Face Image Retrieval. IJCAI, 2017, pp. 2266–2272.

- Jiang, Q.Y.; Li, W.J. Asymmetric deep supervised hashing. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2018, Vol. 32.

- Xia, R.; Pan, Y.; Lai, H.; Liu, C.; Yan, S. Supervised hashing for image retrieval via image representation learning. Twenty-eighth AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2014.

- Shen, F.; Gao, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Shen, H.T. Deep asymmetric pairwise hashing. Proceedings of the 25th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 2017, pp. 1522–1530.

- Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Ms-rmac: Multiscale regional maximum activation of convolutions for image retrieval. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2017, 24, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolias, G.; Sicre, R.; Jégou, H. Particular object retrieval with integral max-pooling of CNN activations. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.05879. [Google Scholar]

- Seddati, O.; Dupont, S.; Mahmoudi, S.; Parian, M. Towards good practices for image retrieval based on CNN features. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision workshops, 2017, pp. 1246–1255.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 770–778. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Han, R.; Rao, Y. A new feature pyramid network for object detection. 2019 International Conference on Virtual Reality and Intelligent Systems (ICVRIS). IEEE, 2019, pp. 428–431.

- Jin, Z.; Li, C.; Lin, Y.; Cai, D. Density sensitive hashing. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2013, 44, 1362–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andoni, A.; Indyk, P. Near-optimal hashing algorithms for near neighbor problem in high dimension. Communications of the ACM 2008, 51, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis, B.; Darrell, T. Learning to hash with binary reconstructive embeddings. Advances in neural information processing systems 2009, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Ji, R.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W. Towards optimal binary code learning via ordinal embedding. Thirtieth AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2016.

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, N.; Li, S. Order preserving hashing for approximate nearest neighbor search. Proceedings of the 21st ACM international conference on Multimedia, 2013, pp. 133–142.

- Shen, F.; Shen, C.; Liu, W.; Tao Shen, H. Supervised discrete hashing. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 37–45.

- Salakhutdinov, R.; Hinton, G. Semantic hashing. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning 2009, 50, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Jiang, M.; Yuan, P.; Zhang, B. Scalable discrete supervised multimedia hash learning with clustering. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2017, 28, 2716–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Ji, R.; Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Y. Towards optimal discrete online hashing with balanced similarity. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 8722–8729.

- Jegou, H.; Douze, M.; Schmid, C. Product quantization for nearest neighbor search. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2010, 33, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Y.; Torralba, A.; Fergus, R. Spectral hashing. Advances in neural information processing systems 2008, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Lazebnik, S.; Gordo, A.; Perronnin, F. Iterative quantization: A procrustean approach to learning binary codes for large-scale image retrieval. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2012, 35, 2916–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Kumar, S.; Chang, S.F. Hashing with graphs. Icml, 2011.

- Datar, M.; Immorlica, N.; Indyk, P.; Mirrokni, V.S. Locality-sensitive hashing scheme based on p-stable distributions. Proceedings of the twentieth annual symposium on Computational geometry, 2004, pp. 253–262.

- Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Ji, R.; Jiang, Y.G.; Chang, S.F. Supervised hashing with kernels. 2012 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. IEEE, 2012, pp. 2074–2081.

- Norouzi, M.; Fleet, D.J. Minimal loss hashing for compact binary codes. ICML, 2011.

- Cao, Y.; Liu, B.; Long, M.; Wang, J. Hashgan: Deep learning to hash with pair conditional wasserstein gan. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 1287–1296.

- Zhuang, B.; Lin, G.; Shen, C.; Reid, I. Fast training of triplet-based deep binary embedding networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 5955–5964.

- Liu, B.; Cao, Y.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Deep triplet quantization. Proceedings of the 26th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 2018, pp. 755–763.

- Yang, H.F.; Lin, K.; Chen, C.S. Supervised learning of semantics-preserving hash via deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2017, 40, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, W.; Tian, Q.; Li, H. A general framework for linear distance preserving hashing. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2017, 27, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Shen, H.T. Unsupervised deep hashing with similarity-adaptive and discrete optimization. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2018, 40, 3034–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Geng, L.; Lai, H.; Pan, Y.; Yin, J. Feature pyramid hashing. Proceedings of the 2019 on International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, 2019, pp. 114–122.

- Redaoui, A.; Belloulata, K. Deep Feature Pyramid Hashing for Efficient Image Retrieval. Information 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaoui, A.; Belalia, A.; Belloulata, K. Deep Supervised Hashing by Fusing Multiscale Deep Features for Image Retrieval. Information 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.W.; Li, J.; Tian, X.; Wang, H.; Kwong, S.; Wallace, J. Multi-level supervised hashing with deep features for efficient image retrieval. Neurocomputing 2020, 399, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G.; et al. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images 2009.

- Bai, J.; Li, Z.; Ni, B.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Hu, C.; Gao, W. Loopy residual hashing: Filling the quantization gap for image retrieval. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2019, 22, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, T.S.; Tang, J.; Hong, R.; Li, H.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, Y. Nus-wide: a real-world web image database from national university of singapore. Proceedings of the ACM international conference on image and video retrieval, 2009, pp. 1–9.

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755.

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. International journal of computer vision 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G Hinton, N.S.; Swersky, K. Overview of Mini Batch Gradient Descent. Computer Science Department, University of Toronto, 2015.

- Jiang, Q.Y.; Li, W.J. Scalable graph hashing with feature transformation. Twenty-fourth international joint conference on artificial intelligence, 2015.

- Wang, J.; Kumar, S.; Chang, S.F. Semi-supervised hashing for large-scale search. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2012, 34, 2393–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Long, M.; Liu, B.; Wang, J. Deep cauchy hashing for hamming space retrieval. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 1229–1237.

- Cao, Z.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Yu, P.S. Hashnet: Deep learning to hash by continuation. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 5608–5617.

- Sun, Y.; Yu, S. Deep Supervised Hashing with Dynamic Weighting Scheme. 2020 5th IEEE International Conference on Big Data Analytics (ICBDA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 57–62.

- Bai, J.; Ni, B.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Cheng, S.; Yang, X.; Hu, C.; Gao, W. Deep progressive hashing for image retrieval. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2019, 21, 3178–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, N.; Tang, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, F. Multi-granularity feature learning network for deep hashing. Neurocomputing 2021, 423, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Conv Block | Layers | Kernel Sizes | Feature Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conv2D, Conv2D#, MaxPooling | , | |

| 2 | Conv2D, Conv2D#, MaxPooling | , | |

| 3 | Conv2D, Conv2D, Conv2D, Conv2D#, MaxPooling | , , , | |

| 4 | Conv2D, Conv2D, Conv2D, Conv2D#, MaxPooling | , , , | |

| 5 | Conv2D, Conv2D, Conv2D, Conv2D#, MaxPooling | , , , |

| CIFAR-10 (MAP) | NUS-WIDE (MAP) | |||||||

| Method | 12 bits | 24 bits | 32 bits | 48 bits | 12 bits | 24 bits | 32 bits | 48 bits |

| SH [33] | 0.127 | 0.128 | 0.126 | 0.129 | 0.454 | 0.406 | 0.405 | 0.400 |

| ITQ [34] | 0.162 | 0.169 | 0.172 | 0.175 | 0.452 | 0.468 | 0.472 | 0.477 |

| KSH [37] | 0.303 | 0.337 | 0.346 | 0.356 | 0.556 | 0.572 | 0.581 | 0.588 |

| SDH [28] | 0.285 | 0.329 | 0.341 | 0.356 | 0.568 | 0.600 | 0.608 | 0.637 |

| CNNH [16] | 0.439 | 0.511 | 0.509 | 0.522 | 0.611 | 0.618 | 0.625 | 0.608 |

| DNNH [8] | 0.552 | 0.566 | 0.558 | 0.581 | 0.674 | 0.697 | 0.713 | 0.715 |

| DHN [7] | 0.555 | 0.594 | 0.603 | 0.621 | 0.708 | 0.735 | 0.748 | 0.758 |

| HashNet [58] | 0.609 | 0.644 | 0.632 | 0.646 | 0.643 | 0.694 | 0.737 | 0.750 |

| DPH [60] | 0.698 | 0.729 | 0.749 | 0.755 | 0.770 | 0.784 | 0.790 | 0.786 |

| LRH [50] | 0.684 | 0.700 | 0.727 | 0.730 | 0.726 | 0.775 | 0.774 | 0.780 |

| MFLH [61] | 0.726 | 0.758 | 0.771 | 0.781 | 0.782 | 0.814 | 0.817 | 0.824 |

| MDFF-SH | 0.811 | 0.854 | 0.874 | 0.880 | 0.828 | 0.854 | 0.866 | 0.887 |

| MS-COCO (MAP) | ||||

| Method | 16 bits | 32 bits | 48 bits | 64 bits |

| SGH [55] | 0.362 | 0.368 | 0.375 | 0.384 |

| SH [33] | 0.494 | 0.525 | 0.539 | 0.547 |

| PCAH [56] | 0.559 | 0.573 | 0.582 | 0.588 |

| LSH [4] | 0.406 | 0.440 | 0.486 | 0.517 |

| ITQ [34] | 0.613 | 0.649 | 0.671 | 0.680 |

| DHN [7] | 0.608 | 0.640 | 0.661 | 0.678 |

| HashNet [58] | 0.642 | 0.671 | 0.683 | 0.689 |

| DCH [57] | 0.652 | 0.680 | 0.689 | 0.690 |

| DHDW [59] | 0.655 | 0.681 | 0.695 | 0.702 |

| MDFF-SH | 0.726 | 0.797 | 0.830 | 0.842 |

| Method | CIFAR-10 (MAP) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 Bits | 24 Bits | 32 Bits | 48 Bits | |

| 0.710 | 0.761 | 0.775 | 0.788 | |

| –5 | 0.580 | 0.595 | 0.639 | 0.688 |

| MDFF-SH | 0.811 | 0.854 | 0.874 | 0.880 |

| Method | CIFAR-10 (MAP) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 Bits | 24 Bits | 32 Bits | 48 Bits | |

| MDFF-SH-J2 | 0.667 | 0.812 | 0.830 | 0.852 |

| MDFF-SH-J3 | 0.656 | 0.742 | 0.785 | 0.796 |

| MDFF-SH | 0.811 | 0.854 | 0.874 | 0.880 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).