1. Introduction

The significance of sustainable renewable energy is increasing steadily as a substitute for traditional energy sources, owing to its renewable nature, excellent chemical characteristics, and little pollution throughout its life cycle [1]. The current discourse centers around the creation of sustainable and renewable aviation fuel derived from biomass and waste materials. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the yearly financial expenditure on aircraft amounted to approximately 343 billion liters. Out of this total, just 0.015 billion liters were sourced from renewable sources. Under typical business circumstances, the aviation industry's contribution to worldwide greenhouse gas emissions is projected to rise by 5% by the year 2050 [2,3,4,5].

Figure 1.

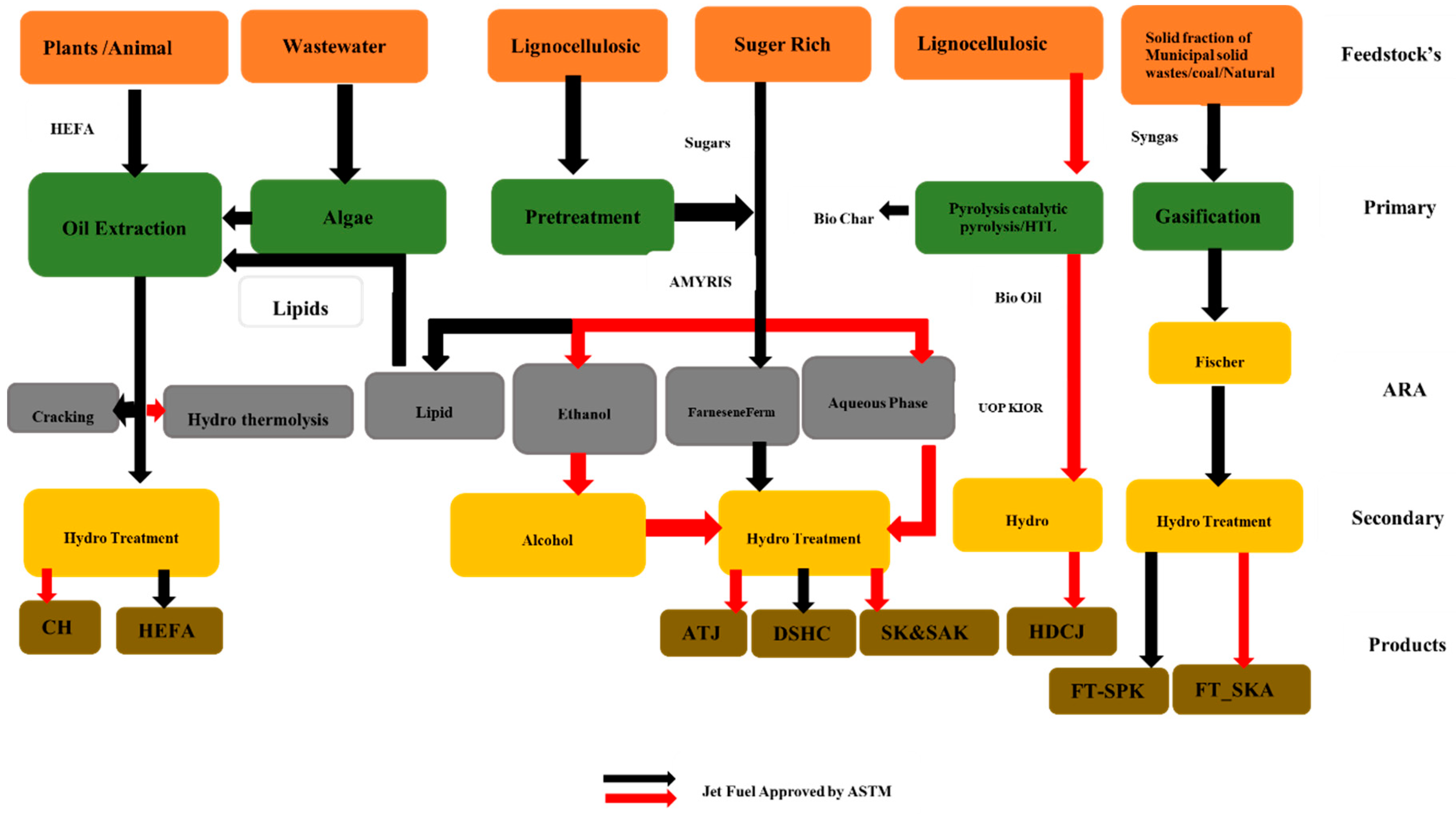

The production pathway for the synthesis of biofuel has been approved and is currently under investigation [6,7,8].

Figure 1.

The production pathway for the synthesis of biofuel has been approved and is currently under investigation [6,7,8].

The International Aviation Authority is dedicated to attaining aggressive climate change objectives, specifically carbon-neutral expansion by 2020 and complete elimination of CO2 emissions by 2050 [9,10,11,12]. The utilization of alternative fuels for the purpose of sustainable development and aviation-fuel aircraft is on the rise to accomplish this objective. Hence, the pursuit of alternative and renewable energy sources is crucial in addressing the profound impact of fossil fuels on climate change. These sources must be capable of satisfying global energy demands, curbing greenhouse gas emissions, mitigating pollution, and preserving natural temperature levels [13,14]. Industrial and thermal applications in agricultural activities can utilize biodegradable organic matter, excluding creatures, animals, plants, or microorganisms. This includes waste sources, non-fossil organic waste products, and municipal trash [15].

2. Pyrolysis Process

Pyrolysis is a chemical process in which organic materials are decomposed by heat in the absence of oxygen, resulting in the production of gas, liquid, and solid byproducts. This process is anaerobic. Combustion requires oxygen. However, in the absence of oxygen, combustion cannot occur. The compound consisting of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose is utilized to convert biomass into coal and combustible gasses.

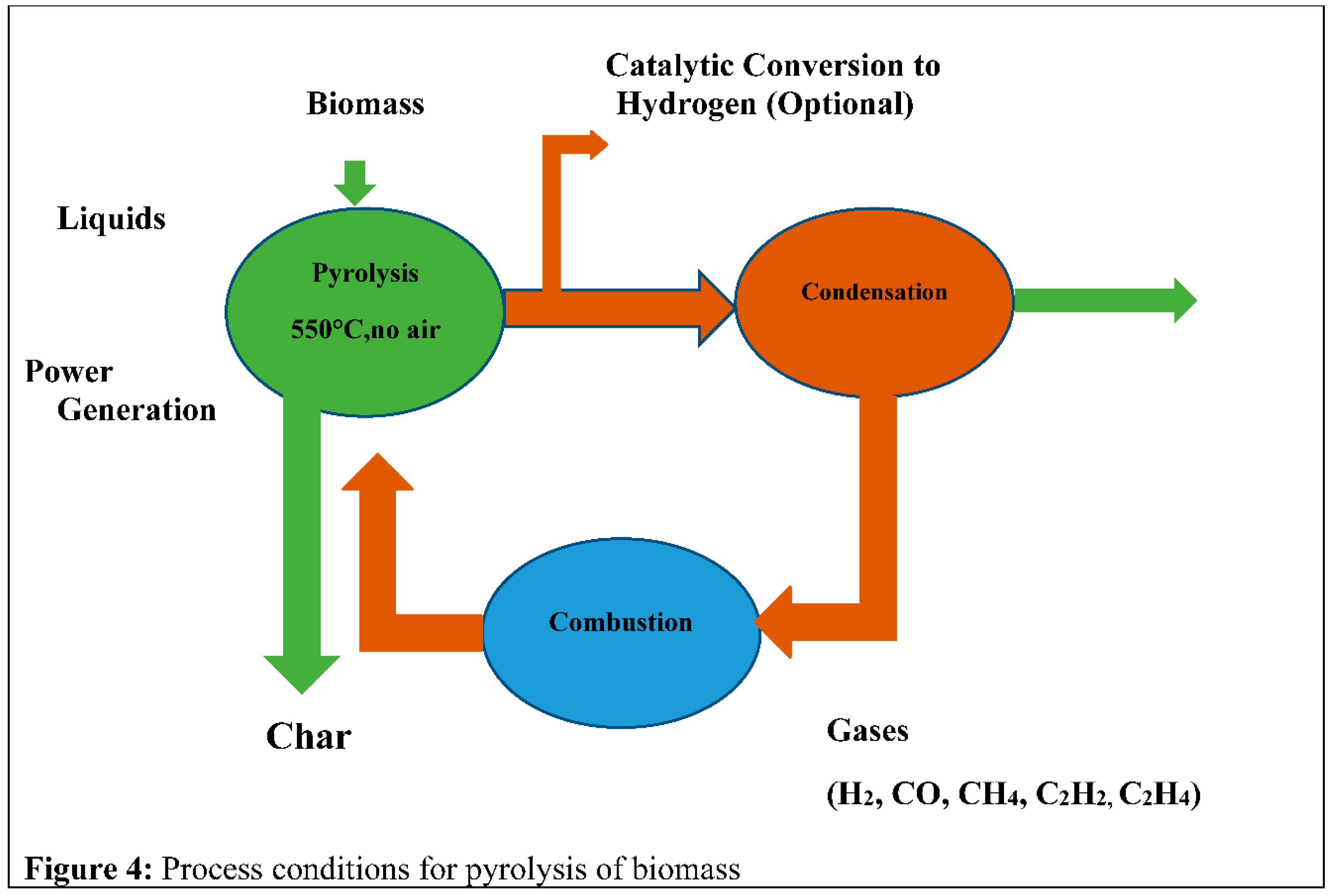

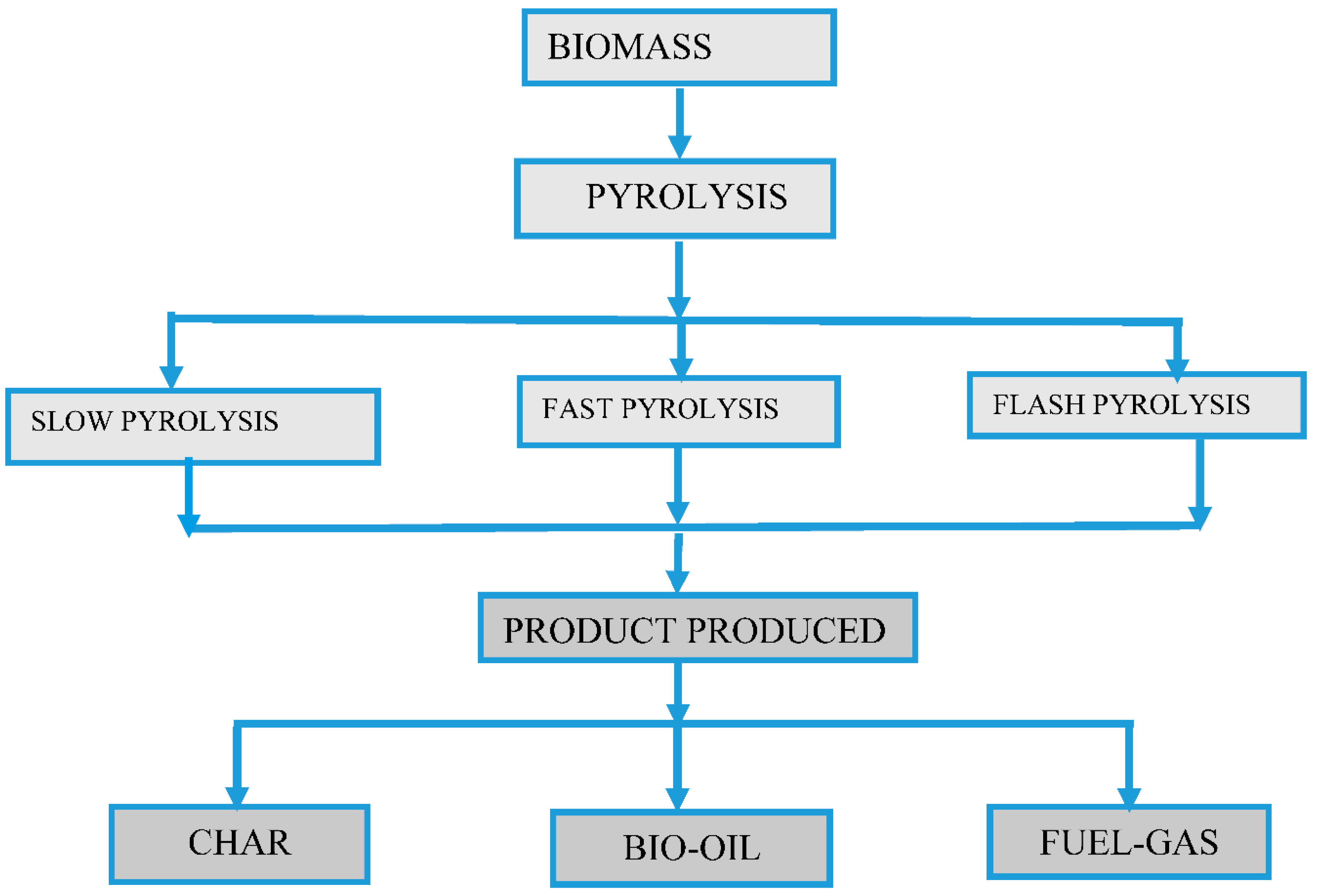

Figure 2 illustrates the pyrolysis system procedure.

Thermal degradation is the commonly acknowledged process for producing solid fuel in a biomass pyrolysis system. Additionally, this process entails the division of carbon-carbon bonds and the formation of carbon-oxygen bonds. Additionally, the crucial criterion for the temperature range is 400°C to 550°C. This system operates effectively when the temperature is elevated [16]. To produce the simulated fuels for the aviation sector, used wastes such as biomass are committed feedstock for its renewability with low CO2, CO, and Carbon emissions. But, some challenges here are a lower density of energy and higher mutability in the formation. Pyrolysis already achieved deliberation in recent years as an applied useful way to transmute biomass to biofuels [17]. Pyrolysis is a part of the gasification and combustion process also which is, the 1st period for the two methods. It also made CO2, CO, and hydrocarbons.

2.1. Types of Pyrolysis

Pyrolysis is categorized into three primary classifications based on its operation. The three types of pyrolysis are slow pyrolysis, fast pyrolysis, and flash pyrolysis. The table displays the classification of pyrolysis, including the relative distribution of products based on its many types and operating conditions.

Table 1.

Typical types and operating conditions for pyrolysis process [18,19,20,21,22].

Table 1.

Typical types and operating conditions for pyrolysis process [18,19,20,21,22].

| Process |

Time (s) |

Heating Value

(K/s) |

Size (mm) |

Temp. (K) |

Yield (%) |

| Oil |

Gas |

Char |

| Slow pyrolysis |

450 to 550 |

0.1 to 1 |

5 to 50 |

550 to 950 |

30 |

35 |

35 |

| Fast pyrolysis |

0.5 to 10 |

10 to 200 |

1 and more |

850 to 1250 |

50 |

30 |

20 |

| Flash pyrolysis |

More than 0.5 |

1000+ |

0.2 and more |

1050 to 1300 |

75 |

13 |

12 |

As per this procedure, the duration for which the steam remains is quite lengthy, ranging from 5 to 30 minutes. Components in the vapor phase undergo continual reactions, resulting in the formation of solid chains and other liquid structures. During Fast pyrolysis, biomass is rapidly degraded at high temperatures and in the absence of O2. During Fast pyrolysis, biomass undergoes rapid decomposition at high temperatures in the absence of oxygen. The Fast Pyrolysis method is characterized by efficient heat transfer and rapid heating rates. It also ensures quick removal of steam and aerosols, resulting in high bio-oil production. Additionally, it allows for precise control of the reaction temperature.

2.2. Syngas Conditioning and Cleaning

Syngas, comprising particulate matter, tannins, CO2, alkaline metals, and sulfur, is a significant byproduct. Slow pyrolysis facilitates the production of approximately 10-35% biogas, resembling char [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The syngas derived from biomass pyrolysis presents itself as a sustainable and renewable energy source, surpassing the environmental benefits of fossil fuels. It proves versatile, finding applications in various sectors, including power generation and transportation, as an alternative fuel in industrial processes. This potential was recognized as early as 1901 and 1920, leading to the development of more economical liquid fuels through steam fuel in internal combustion engines [30,31,32,33]. Currently, IC engines are being considered as fuel for the use of Syngas, which, like Char, has been able to gain interest, the main process of producing about 10% to 35% of biogas, is the slow pyrolysis process. Again flash pyrolysis with high temperature is also capable of giving higher syngas results, for example, investigates the production of Syngas from the pyrolysis of all heatwave MSWs, using dolomite as a catalyst for temperatures ranging from 50°C to 900°C, which is a downstream feed-bed reactor [34,35,36]. This report found the presence of 78.87% gas at 900 ° C as before. A radio frequency plasma pyrolysis furnace once produced Tang and Hang 76.64% Syngas [37]. Pyrolysis temperature affects the results of Syngas very well. Syngas is a mixture of hydrogen (H2) and carbon monoxide (CO). It depends on the biomass feedstock and pyrolysis conditions by hydrocarbons depending on carbon dioxide (CO2), Nitrogen (H2), Methane (CH4), Water, ethylene (C2H4), Ethane (C2h6), ash, tar, etc. Hydro Carbon depends on biomass feedstock and pyrolysis conditions.

2.3. Supercritical Water Pyrolysis

Coal-burning is so complex also it's a very costly process for absorbing indoor sewage sludge (SS). It also can be from the high water content by using the wastes water treatment plant (>85wt% ) as well as burning by MSW/coal, though it's a very complex process and most costly for absorbing the particle content. Usually, that’s always higher output from this method [38,39,40,41]. Whatever, the Main reasons are affecting the output of the products depending on the temperature, the ratio of water to organic matter, and the selection of the catalyst. The actuality of humidity and temperature components for SS (bio-oil, biochar & non –synthetic gas) has been discussed on production and composition. The required temperature is 385°C and humidity is 85 wt.% are the best conditions with the highest bio-oil generation in humidity 37.23 wt.% with a maximum temperature of 31.08 MJ/Kilogram [42,43,44]. At optimal conditions, the yield of aliphatic hydrocarbons and phenols values were respectively around 29.23 watts, and 12.51 wt. Nulls values are in NCGs GC analysis the discovered highest HHV value 13.39 MJ/m3 at the temperature of 445°C and a humidity of 85 wt%. MC's temperature is 550°C, another temperature is 5°C (-1) and 10 % for 45 minutes then constructed the significance to generating the bio-oils to mentioned physic-chemical characteristic output [45,46]. Where the temperature progresses and output to gas growth. The temperature of the pyrolysis range is 300-400 degrees Celsius and can be recommended for sewage pyrolysis [47,48,49,50].

2.4. The Influence of CO2 on Biomass Fast Pyrolysis

For effective economic development by using pyrolysis gas product of CO2 can be recycled the porter gas from biomass using this fast pyrolysis method at moderate temperature [51,52]. This formation and properties from the effects of exploration within five CO2 condensations is (0%, 10%, 20%, 50%, and 100%). The CO2 discovered from the atmospheres results in a produced output from the char & oil since the minor gas supplied. At the atmosphere, situated the carbon dioxide H-containing and O-containing mixed community by reducing from the char to volatiles are responding across char active inside. Carbon dioxide can produce the changeable raising creation of Carbon mono oxide. Phenol is the profuse feature in bio-oil, and the porter gas carbon dioxide could raise much oxygen transmuting into liquid production at the temperature of more than 550°C. Some of the used materials in this process are Wood, straw, and corn stalks, carbon dioxide affects similarly in the pyrolysis method when the Production of char and carbon mono oxide at a time also generated the hydrogen and methane gases [53,54].

2.5. Biomass and Waste Pyrolysis Technology

Such technology can convert biomass very quickly and this heat conversion technology is one of these technologies. It's environmentally friendly and efficient, so it's got everyone's attention. The pyrolysis method is used to convert agricultural waste, scrap tires, recycled plastic municipal waste, etc. into clean energy. An interesting presentation has been made to convert all these wastes into various products that can be used effectively to generate electricity, heat, and chemicals [55].

2.6. Plasma Pyrolysis Technology

Plasma pyrolysis is a process that utilizes heat plasma to convert high-calorie plastic waste into a viable synthesis compound, without the need for inventive methods. This process is a highly effective non-combustible heat treatment in which plastic waste is heated at high temperatures in the presence of oxygen, resulting in the softening of the waste and the production of syngas. The composition primarily consists of common components such as carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and a slightly elevated concentration of hydrocarbons. A local Mechanical Engineering Institute (CSIR), Durgapur, has established a project to extract energy from waste plastics using a plasma Arc pyrolyzer. The pyrolyzer has a capacity of 20 kg/hr. and is specifically developed for treating the current plastic trash. Following the pyrolysis of plasma waste in a plasma arc reactor, the hot gases are quenched using a water scrub to prevent the recombination of gas molecules and interference with the generation of dangerous gas. Mangroves exclusively define the structures of the singer [56,57].

3. The Product of Pyrolysis

Biomass pyrolysis is becoming very popular day by day because of its versatility only with this technology Char, bio-oil, and syngas can be obtained from biomass together. Pyrolysis Thermo Chemicals Conversion process is a process where convergence occurs in the absence of oxidizing agents. This is called the initial stage of decomposition and combustion. The main product of solid is liquid pyrolysis oil, char, and gas biomass pyrolysis. There Charcoal needed less temperature and low heating rate procedure, fuel gas needed huge temperature, and less heat and liquid products needed lighter heating rate and less temperature. This table shows the pyrolysis process at various temperatures.

Table 2.

Pyrolysis processes at various temperature [58]:.

Table 2.

Pyrolysis processes at various temperature [58]:.

| Condition |

Processes |

Products |

| <350 |

Generation of free radicals, removal of water, and breakdown of polymers. |

The process involves the creation of carbonyl and carboxyl groups, the release of carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2), and the formation of a mostly charred residue. |

| 350-450°C |

The cleavage of glycosidic bonds in polysaccharides by substitution. |

The mixture consists of levoglucosan and anhydrides.

Oligosaccharides are targeted as a tar section. |

| 450-500°C |

The processes of dehydration, rearrangement, and fission of sugar units |

Carbonyl compounds are formed through a chemical process. |

| >500 °C |

An amalgamation of all the methods. |

An amalgamation of the products |

| Condensation |

Unsaturated goods undergo shrinkage and splitting, resulting in the formation of char. |

A residue of extremely reactive char containing trapped free radicals |

3.1. Pyrolysis Oil/ (Bio Oil)

Bio-oil is a type of oil that is dark brown which is a biomass of a huge number of chemical compounds formed in a biological stage. It is a classification of many types of chemical compounds, biomass cellulose, at the organic level, hemicellulose, and various basic elements. Bio-oil contains oxygenated organic compounds like acetone, methanol, and acetic acid. Biomass is a method that is a remarkable method for non-focused and organic matter derived from plants. Animals and microorganisms Biomass is very much available Developing countries meet 38 to 40 percent of their initial electricity consumption with this biomass, waste-based feedstock use and biomass sources are most important for research into clean energy production through thermochemical or biochemical. Agriculture, Forest products, and River-drain waste (also waste, reuses, and products) dedicated energy crops, bio –biological fractions of Municipal and industrial wastes, these wastes are primarily included in the biomass organization.

Bio-oil comprises undesirable components, including volatile acids, water, and a significant proportion of highly oxygenated compounds, leading to decreased heat dissipation. Biomass is the primary component of Pyrolysis. Catalytic pyrolysis is a method used to enhance the quality of bio-oils by eliminating oxygenated compounds, enhancing their energy content, reducing their viscosity, and improving their durability. Researchers aim to achieve these improvements in bio-oil to optimize furnace design.

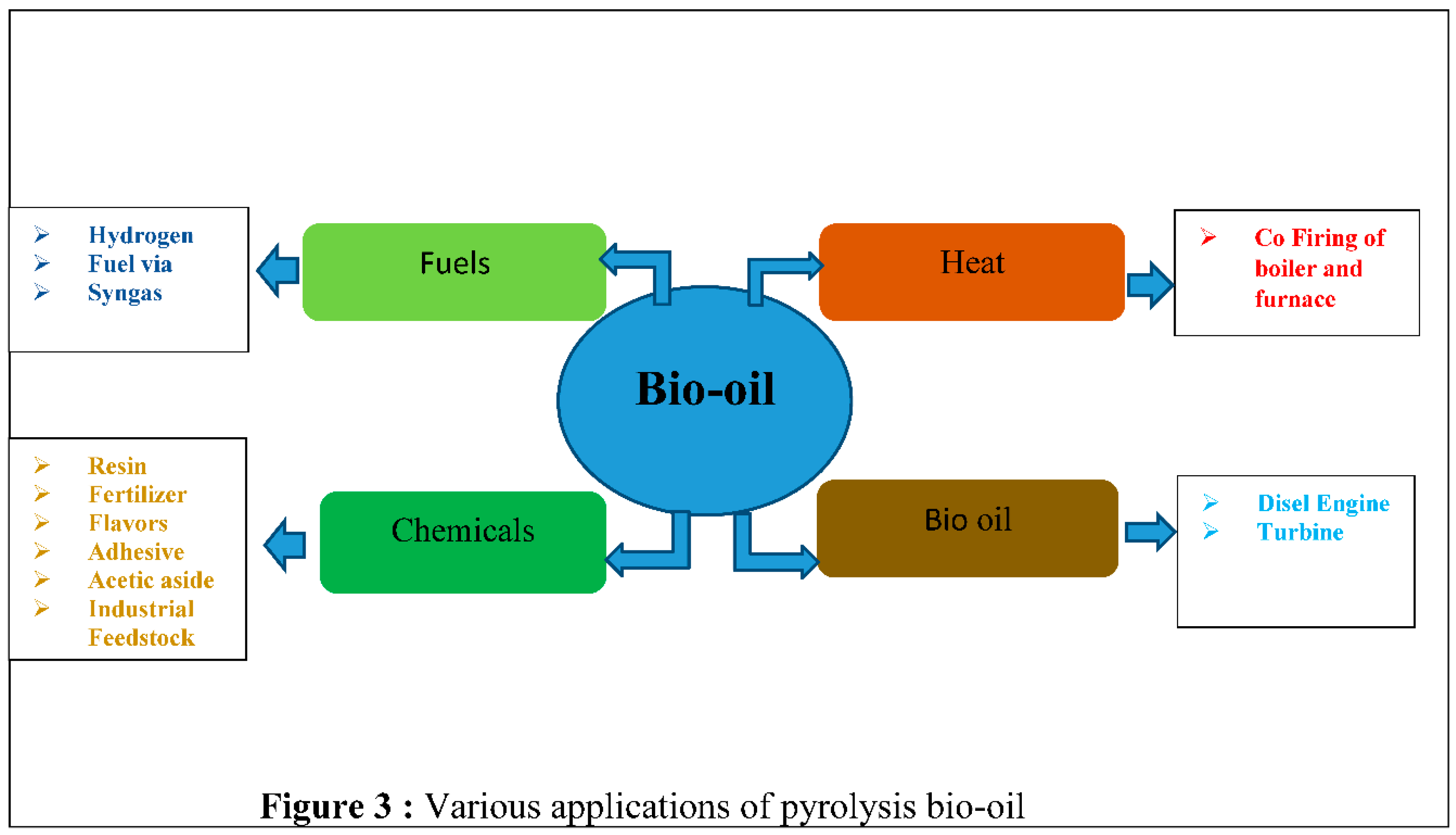

Figure 3 illustrates the various applications of the bio-oil product. It can be utilized as a fuel for transportation or as a chemical compound. Additionally, it can be employed in turbines and electronics that are utilized in power production for the purpose of generating heat engines or boilers.

3.2. Bio-Char

Biochar is a term coined recently with growing interest in renewable energy, soil modification, and carbon exploration. It is a fine-grained, high-carbon this type of pore is often formed by heat decomposition of biomass at lower temperatures than required (Less than 700°C) or under limited oxygen [59,60].

Thermochemical decomposition in biomass is the absence of oxygen in the pyrolysis process at a temperature of 300°C -700 °C. Bio-char production is an emerging technology that improves the food security of countries and also can mitigating climate change. [61,62]. There is a possibility of applying bio-char of late nature because waste management produces bio surgical treatment also soil enrichment has been widely highlighted by addressing the issues of increasing soil fertility by changing soil pH. Retain nutrients through the caption. Decreased absorption of various organic pollutants such as Carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (Ch4), nitrous oxide (N2O), And improved productivity pyrolysis systems of biomass intensity [63]. that also shows the producing system of bio-char.

Sustainable biochar is one of the few fast scalable and applied technologies and is relatively less expensive than other sustainable biochar. There are many types of benefits that are given below:

Decreased nitrogen in ground water.

Potential reduced emission of nitrous oxide.

Increasing the capability of catching-exchange result in better soil fertility.

Soil acidity moderation.

Developed the number of beneficial soil germs.

Retain greater water.

4. Pyrolysis Reactor

The reactor is the main part of a pyrolysis process. Rector is a subject where there is a lot of research, development to improve the required properties of high-temperature rates and innovation, medium temperature for liquid and short vapor product housing time. At 1st the pyrolysis reactor developer assumed that the size of the small biomass atoms is less than 1mm. And high bio-oil yield can be achieved during very shorts stays but subsequent studies have yield different results. Particle size or shape and the presence of vapor have very little effect on time in bio-oil production; these parameters inevitably affect bio-oil synthesis [64]. with the continuation of the pyrolysis technology, several furnace designs have been explored to optimize pyrolysis performance and produce high-quality organic oil.

4.1. Microwave PYROLYSIS Reactor

Pyrolysis with microwave is one of the valuable methods for biomass conversion. There are Innumerable studies in the scientific lesson originally reported for pyrolysis of biomass. Microwave reactors a recent study focus on the pyrolysis application where energy is the molecules are transferred through the action of methane and the microwave uses a heated bed for this. The pyrolysis and drying process of biomass are driven by microwave cavity over electricity. Inert gas is continuously flowed to release O2 (oxygen) to the reactor.

In addition to the atmosphere, it is treated as a carrier gas. Microwave pyrolysis reactor provided many kinds of facilities in slow pyrolysis which make a way to recover effective chemicals from their biomass. Therefore, that’s fully clear and possible to process. Microwave reactors can process a wide range of biomass and desirable products like syngas and bio-oils can be obtained from waste [65]. Using the microwave reactor we can get various desired substances through pyrolysis technology. These biological substances include corn stalk automotive waste oil, wood corn dust, sewage sludge, woodblock, rice straw, and glycerin.

4.2. Fixed Bed Reactor

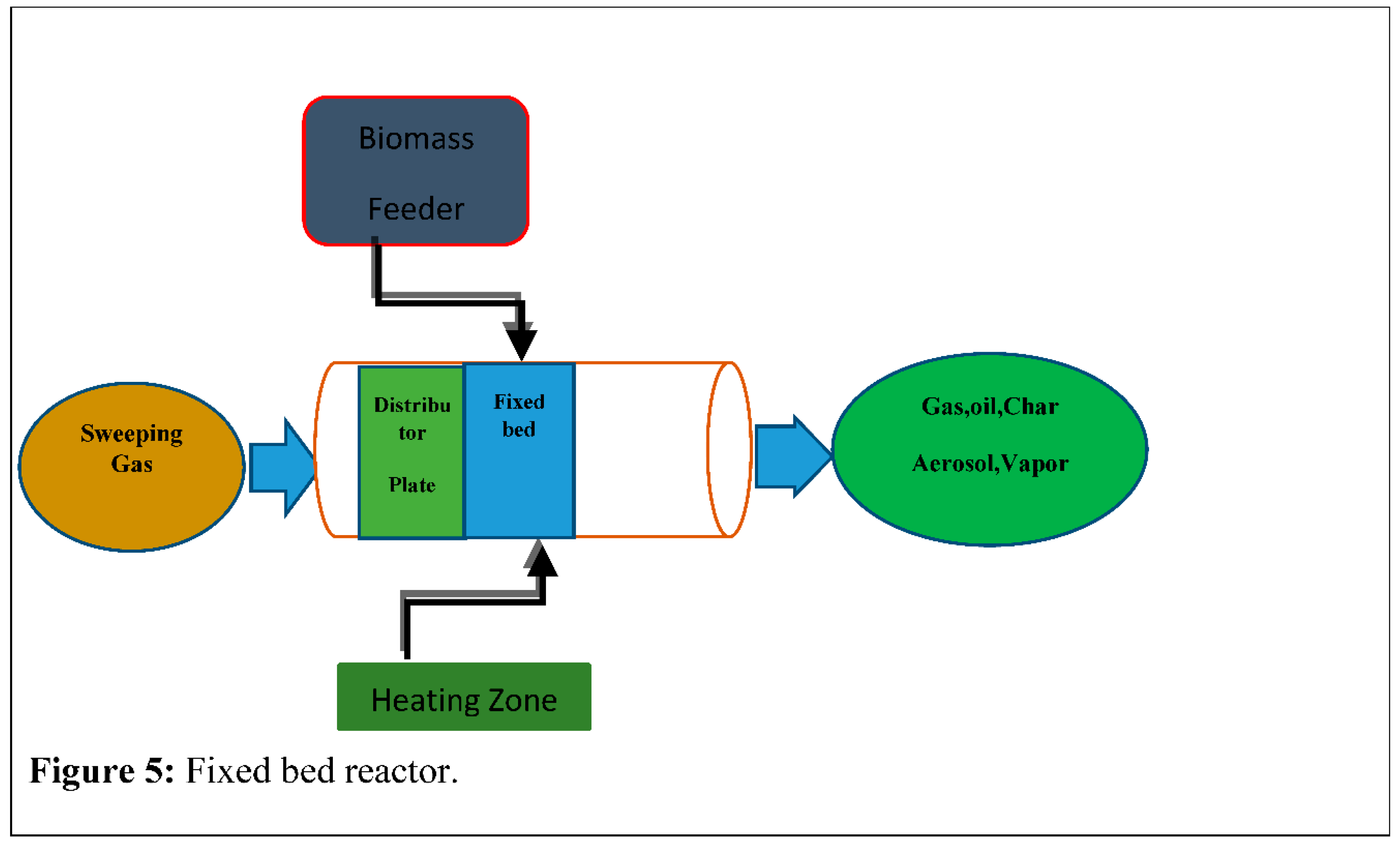

This is another useful method of reactor bed pyrolysis which forms by the furnace with the cleaning and cooling system by gas. This method is very reliable and usual also proved for this type of fuel. The size is comparatively similar and the amount of fires is low [66]. In this kind of furnace, materials are transferred inside the vertical arrow or shaft and connect to the product gas flow running upwards of counter–current. Typically fixed bed reactor (FBR) is made of fireproof bricks, heavy steel or corner, etc. It is also constructed by the feeding unit of fuels, drainage unit of ashes, and exhaust unit of gases. Fixed bed furnace is a common function including high carbon conservation, low gas speed, and long-lasting housing with low residue. A big problem with fixed bed furnace in structure, the tar by the current growth of tar heat and transformation the potential to the seize rate [67]. In Figure-6: Given the stationary bed furnace that's discriminate standard also enrolled usual units absorbing the granulate, heating & cooling. The Cooling method and the gas cleaners include filtration by the Cyclones, a damp washer, and also the dry filters [68,69]. In a fixed bed, the pyrolysis method “temperature” ensures to temperature program elements, such as the rate of heat and it stays the temperature remains under the founded margin by an operator. The ultimate temperature for the pyrolysis method is 450°C-750°C as the heating rate fluctuates among 100°C per minute [70]

4.3. Fluidized Bed Reactor

The Fluidized Bed reactor contains a liquid-liquid mixture that exhibits characteristics of liquids. This is usually achieved by the introduction of a pressurized liquid through solid particulate matter. Fluidized Bed Reactor looks like fast reactor pyrolysis because it transfers heat very quickly, better wide high surface area contacts for pyrolysis reaction and steam retention liquid and hard unit bed volume, this system conducts heat well and creates high relative velocity between solid and liquid phases [71]. Different types of the reactor in there describe below.

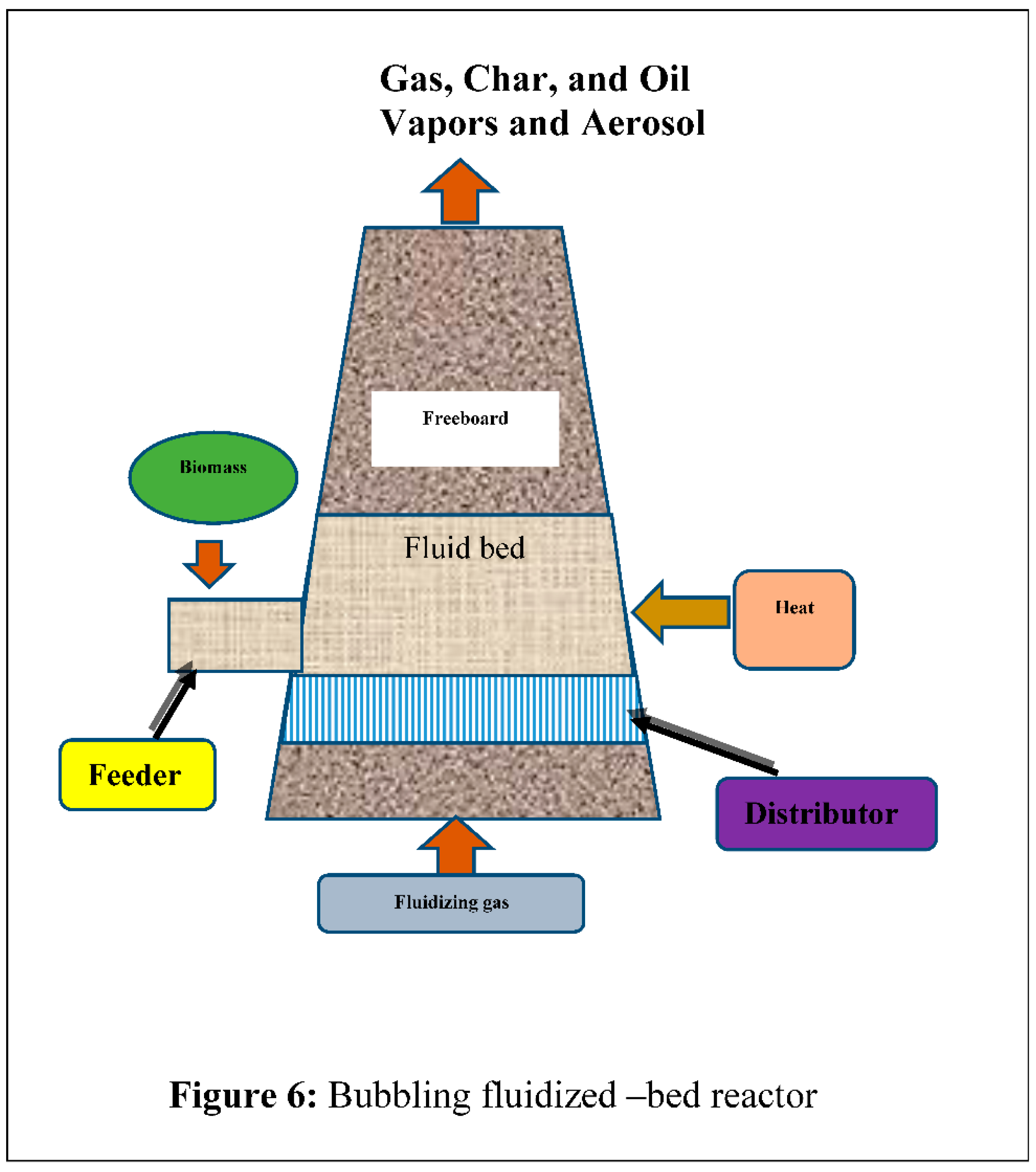

4.4. Bubbling Fluidized –Bed Reactor

Constructing and handling bubble liquid beds is highly manageable. The system offers superior heat regulation, efficient gas interaction for temperature exchange, solid handling, and storage capability due to the higher density of solids in the bed. The heated grit serves as a dense layer that facilitates the rapid thermal decomposition of biomass in an oxygen-free environment, resulting in the formation of chars, aerosols, gases, and vapors. The fluidizing gas flow exhibits the egress of the decomposing biomass material from the furnace, as depicted in

Figure 6 [72]. A bubbling fluidized-bed reactor.Pyrolysis is widely favored because to its ability to generate bio oil of superior quality, with a liquid yield ranging from 70% to 75% by weight of dry biomass.

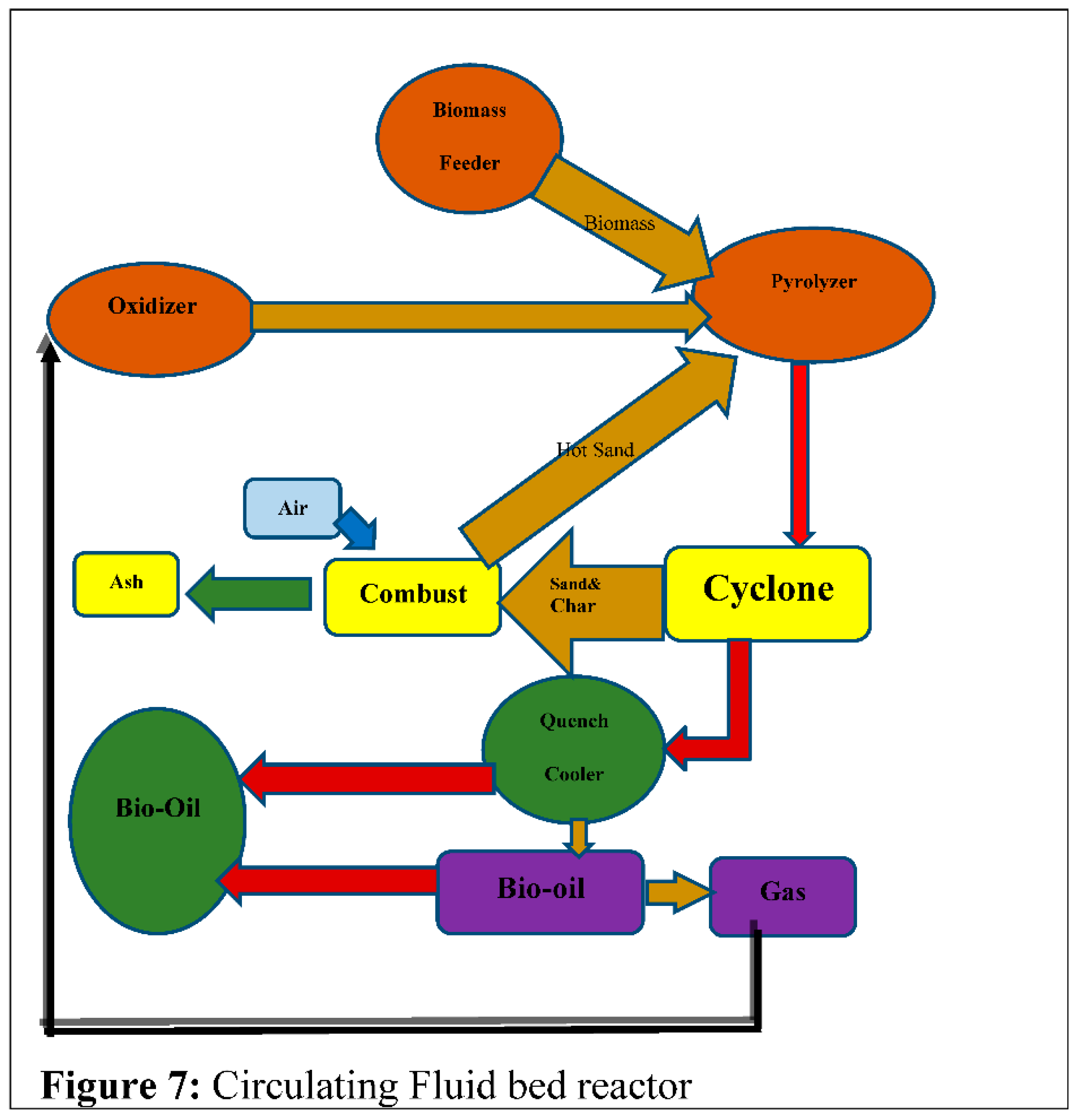

4.5. Circulating Fluidized-Bed Reactors

Circulating Fluidized-Bed Reactors are similar to bubble fluid bed reactors, and this form of reactor is more advantageous (mn113). There are two widely observed forms of Circulating Fluidized-Bed Reactors: single circulation and double circulation [73]. The gasification process in rotating Circulating Fluidized-Bed Reactors has the same properties as a bubble fluidized bed furnace, but with increased gas charges at reduced volumes. The pyrolyzer in the reactor is controlled by the Circulating Fluidized-Bed Reactors.

Figure 7 depicts the circulating liquid bed furnace.

4.6. Vacuum Reactor

Vacuum Reactors perform a slow pyrolysis process with a low heat transfer rate resulting in a 35%-50% reduction in bio-oil yields compared to the 75Wt% reported with bed technologies, which requires huge cost for maintenance of Vacuum Reactors. An induction and combustion heater with fragrant salt is used [74] because of the vacuum function. These types of pyrolysis reactors always needed great solution feeding and discharge devices to maintain a good seal. Continuous operation of the vacuum pyrolizer includes higher feedstock input instruments that discourage dormant investors [75,76]

4.7. Ablative Reactor

Ablative reactor pyrolysis differs fundamentally from the liquid bed method in the lack of liquid gas. Mechanical presses are used to push the heated furnace wall by biomass. The elements closest to the wall are “Melts” and there is no need to grind the feed material too much as it evaporates the remaining oil as pyrolysis vapor [77]. This tie is the advantage of the Ablative reactor, Biomass particles much larger than other processes are allowed here. The science does not have heat and cooling, also has cost and high energy efficiency. Liquid gases are required moreover, they tolerate condensation unit fixing with a small volume, low cost require also less space [78]

4.8. Auger Reactor

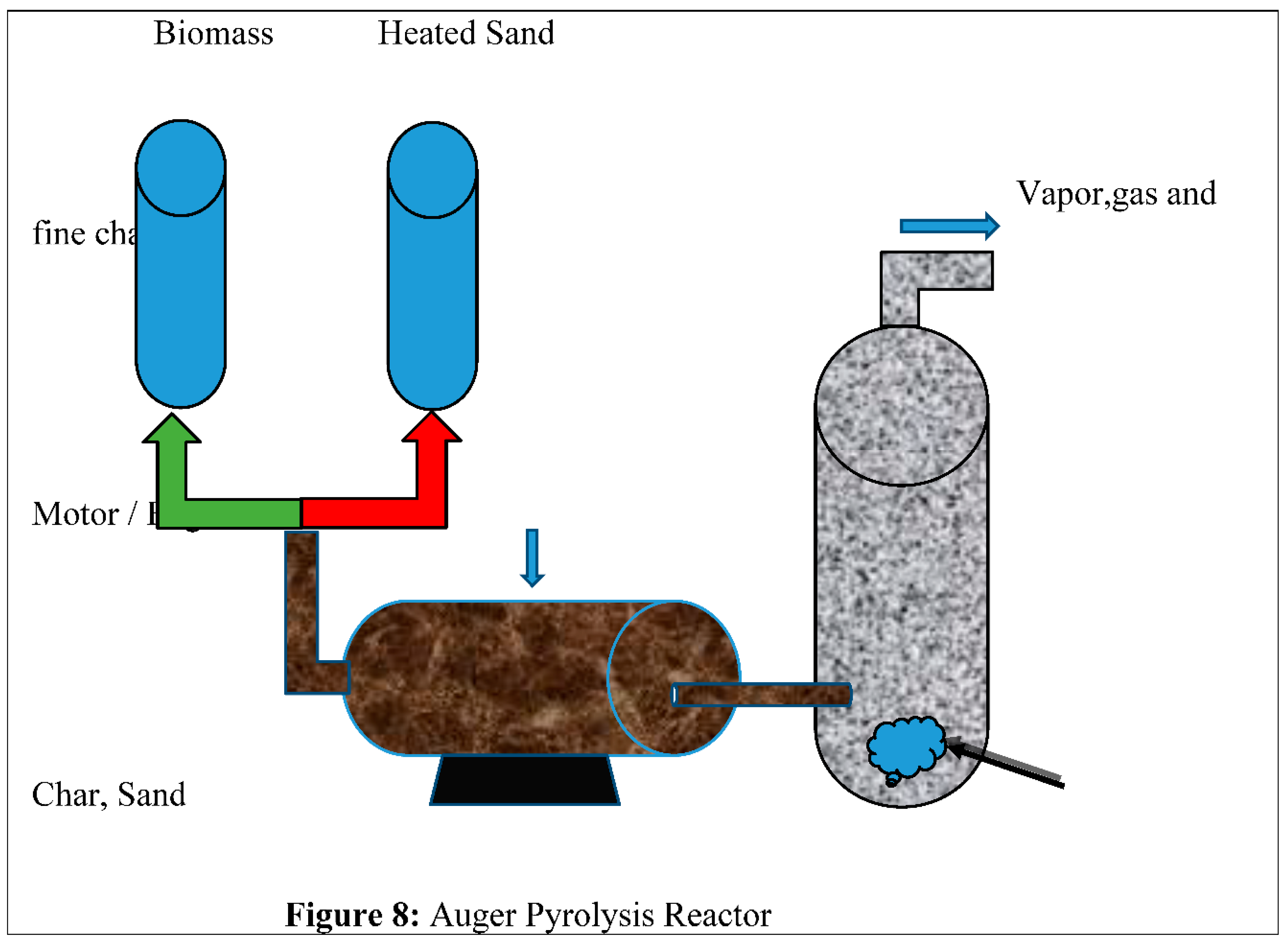

The Auger Reactor utilizes front reactors to facilitate the exchange of biomass feedstock through an Oxygen-free cylindrical tube. The tube facilitates the elevation of the feedstock to the optimal pyrolysis temperature range, ranging from 400 degrees Celsius to 800 degrees Celsius, resulting in its transformation into a gaseous state. The Auger Reactor is gaining increasing attention from numerous medium-sized industries. Includes challenges for annual reactors excessive amount of heat and temperature trigger the transmission in this design the steam time can be adjusted before entering the condenser train by changing the steam heated zone [79]. Figure (8) shows that:

4.9. PyRosReactor

Pyros pyrolysis is usually applied to make caramel-free bio-oil by integrating it into a single unit. For this, a little hot gas filter is used in a cyclone furnace. Inert heat carriers and biomass are converted into cyclone particles and solids are transported from the process through recycled vapors. The concentrated particles are forcibly moved downward into the perimeter of the cyclone. When moving to the bottom of the furnace, all the biomass particles are destroyed, heated, and dried. The average procedure temperature is 400°C-550°C. The furnace is 0’s to 1’s during the normal gas residence, so the second cracking process of tar in the reactor can be reduced. The reactor is comparatively low cost and very compact. It also has a production capacity of 70 to 75 percent [80].

4.10. Rotating Core Reactor

One of the most effective ways to transfer heat to biomass in the pyrolysis process is the Intense mixing of hot purpose particles and biomass. It is a small type of originality pyrolysis reactor for flash pyrolysis with small char formation. Biomass components such as date kernel, rice husk, coffee husk, wood, and other national ingredient rotating core furnace.There are no large commercial applications for rotating core reactors. Even then the high-speed relation induces a dynamic mixture of biomass that progresses rapidly, transferring heat rapidly [81].

5. Various Fuel Project

Over the past few years, energy projects have gained momentum from waste and various reports have been published by various organizations trying to commercialize their process. The process has been given different names in different parts of the world such as demo scale, pilot scale, or commercial scale. There are many types of catalysts employed in the process of plastic pyrolysis. The most used catalysts are Y-zeolite, ZSM-5, FCC, Zeolite, and MCM-11 [82,83]. Plastic waste on solid acid catalysts may be involved in the catalytic process during pyrolysis aromatization, cracking oligomerization, ionization reactions, and cyclization. Many studies have shown that microspores and mesopores are used as catalysts to convert plastic waste into oil and char, such as polyethylene (PE) by HZSM-5 catalyst which is the pyrolysis of the catalyst [84,85,86,87].

5.1. Waste to Fuel

Over time pyrolysis and reporting of plastic waste, including the modified MCM-41 and HZSM-5, is produced using the light hydrocarbon (C3-C4) HZSM-5 with the most fragrant compounds [88]. Various catalysts have been used and reported, even with HZSM-5. Mesopores (CO2-Al 2 and 3) or maximum oil production occurs if MCM-31 is mixed with minimum gas production [11]. The synthesis of aromatic and aliphatic chemicals by mesoporous catalysis involves the utilization of HZSM-5. Decreasing the utilization of Mesopores MCM-11 leads to a decrease in the formation of aromatic compounds resulting from acid catalysis.

5.2. Hydrogen to Jet-A Fuel

Another study seeks to predict the operational and environmental characteristics of compact gas turbine engines operating on alternate fuels. The performance, combustion, and emission aspects of jet fuel with different additives are analyzed. The experimental investigation was conducted on gas turbine engines using Jet A-1 fuel and varying loads. The primary components used in the fuel blends for Jet A-1 are Canola oil and pyrolysis oil derived from solid waste. Next, highly concentrated multiwall carbon nanotubes are subjected to ultrasonic processing utilizing two different fuel blends: the main canola mix consisting of 70% Jet-A, 20% canola, and 10% ethanol, and the P20E blend consisting of 70% Jet-A, 20% PO, and 10% ethanol. Observations - When the mixtures are set to a significantly high static thrust, a considerable amount of fuel is consumed.

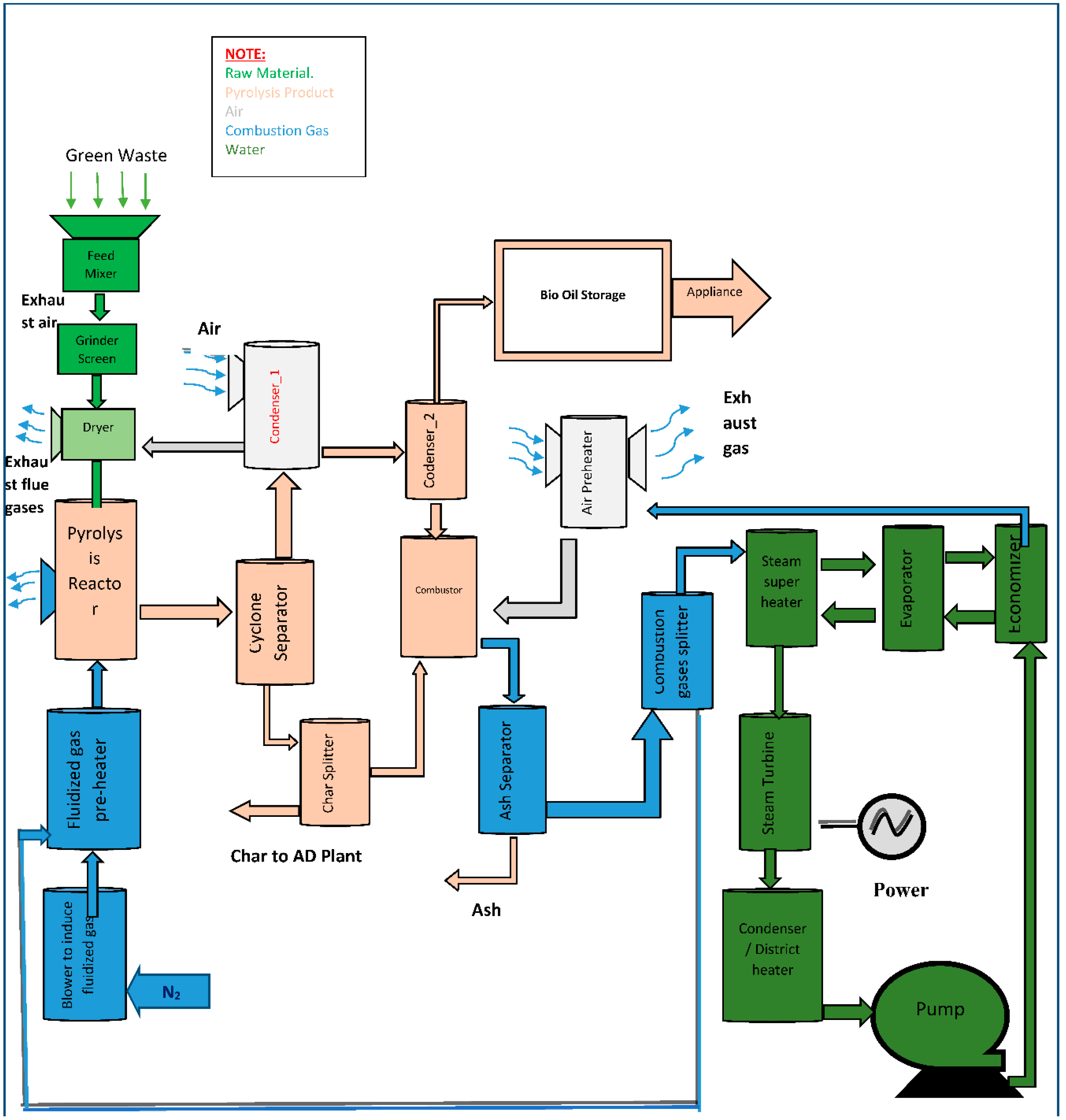

The P20E blend exhibits a significant improvement in fuel efficiency, with a 39% decrease in thrust-specific fuel consumption, as well as a notable increase in static thrust by 32%, when compared to other fuel mixes. Moreover, the blends PO20E and C20E exhibit larger concentrations of ethanol, leading to a significant enhancement of 22% in thermal efficiency and a noteworthy rise of 9% in oxygen content, both of which are observable impacts. Gas turbine engines, through the utilization of fuel blends, emit minimal amounts of CO, CO2, and NOx, hence reducing the allowable thresholds for the utilization of fossil fuels with reduced pollution. Utilizing hydrogen in Jet-A fuel enhances the emissions performance of gas turbine engines. The utilization of hydrogen using nanofluids showed great promise when considering the consequences of replacing fossil fuels [89]. This figure 9 shows the process Biomass to Pyrolysis product produces system:

Figure 9.

Biomass to Pyrolysis product produces system.

Figure 9.

Biomass to Pyrolysis product produces system.

6. SAF Production Through Fast Pyrolysis (FP)

Fast pyrolysis (FP) is a thermochemical approach that transforms biomass into solid, liquid, and gaseous substances through moderate pyrolysis treatment temperatures (400–600 °C), rapid feedstock heating rates (>100 °C/min), and short residence durations (0.5-2 s) [90]. The liquid product of fast pyrolysis, known as bio-oil, can be processed into drop-in fuel; however, due to its oxygenate content, thermal instability, corrosiveness, and low energy density, it cannot directly replace fuel [91]. To align with Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) standards and integrate with advanced aviation systems, further improvements to bio-oil are necessary [92]. The FP pathway involves two main stages: the direct thermochemical conversion of biomass into bio-oil, and the subsequent purification of bio-oil to yield SAF components (hydrocarbons) meeting ASTM standards, suitable for standalone use or blending with other jet fuels like FT-SPK and HEFA fuels [93].

Various research projects have utilized lignocellulosic biomass, such as sugarcane bagasse and straw, for the production of SAF via Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. Strategies include catalytic cracking of bio-oil into lighter olefins, conversion of olefins into aromatic hydrocarbons, and hydrogenation to produce cyclic alkanes [94]. Another approach involves the utilization of rice husk through hydroprocessing, fluidized bed reactor FP, and hydro-isomerization/cracking, resulting in SAF with significant aromatic chemicals and iso- and cyclo-alkanes [95]. Galadima et al. offer a comprehensive review of studies on converting biogenic waste into SAF using the FP method [96]. While certain biogenic feedstocks may be effective in FP, those with high moisture levels, like algae, require drying. Some researchers explore hydrothermal methods as an alternative to rapid pyrolysis, with Van Dyk et al. investigating fast pyrolysis (FP), catalytic fast pyrolysis (CFP), and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), producing distinct biocrudes that, after hydrotreatment, fall short of ASTM standards. Optimization of hydrotreating and additional procedures could address these inconsistencies, and multi-criteria decision analysis is proposed for evaluating SAF production paths [97,98].

6.1. Technoeconomic Assessment (TEA) of Fischer-Tropsch (FT) Process for Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF)

A team of academics conducted a comparative techno-economic assessment of three methods for upgrading bio-oil to produce aviation biofuel [99]. Quick pyrolysis emerges as a promising alternative for aviation biofuel production, involving rapid heating of biomass to approximately 500-600°C in an oxygen-free environment. Rapid pyrolysis typically yields 55% to 70% liquids, 15% to 25% solids (biochar), and 10% to 20% non-condensable gases, depending on biomass characteristics [100]. Optimizing liquid production involves rapid vapor quenching, precise temperature control, moderate temperatures, faster heating rates, and minimized residence periods [101]. Fast pyrolysis, with moderate initial investment and higher thermodynamic efficiency than processes like Fischer-Tropsch (FT), can use lignocellulosic feedstocks. It produces aviation fuel with favorable properties for blending with FT-SPK and HEFA jet fuel, featuring excellent cold flow properties and a high concentration of aromatics and cycloparaffins [102]. However, due to bio-oil's acidity and oxygen content, upgrading is necessary. Hydroprocessing (HP), zeolite cracking (ZC), and gasification followed by FT synthesis (G+FT) are the main upgrading methods [103]. Efficient biofuel value chains are crucial for sustainable biofuel companies, emphasizing the optimization of financial potential through economies of scale [104].

In a separate study, researchers explored bio jet fuels' potential yields and emission reductions, focusing on hydrotreatment of biocrudes from direct thermochemical liquefaction [105]. Catalytic pyrolysis-produced biocrudes, favored for their potentially lower oxygen content, face challenges due to oversimplified oxygen considerations. The use of alcohols and ethers is preferred over carboxylic acids, aldehydes, or ketones. Despite having a lower oxygen content, catalytic pyrolysis biocrude faced challenges in co-hydrotreating due to high viscosities. The rapid pyrolysis biocrude, despite its high initial oxygen content, demonstrated favorable overall yields, potential for significant emission reduction (74.3%), and satisfactory jet fuel production results. Hydrothermal liquefaction biocrude showed the highest yields and emissions reduction (51%) using the PNNL approach. However, technical challenges and higher pressures pose obstacles to the commercialization of hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) [105].

6.2. Conversion of Sewage Sludge into Synthetic Aviation Fuel (SAF) Using Pyrolysis

In Brazil, a pioneering project aimed to achieve a significant breakthrough in sustainable aviation fuel production by utilizing sewage sludge [108]. SABESP, a prominent Brazilian water and waste management company, supplied the sewage sludge for the initiative. The process in Brazil involved naturally drying the sewage sludge in the open air, reducing its initial moisture content from 80% by weight to approximately 20% by weight. Subsequently, at the University of Birmingham in the UK, the dehydrated sewage sludge was transformed into pellets using a DORNTEC PTE 50 pelletizer, resulting in pellets with an average diameter of 0.7 cm and a length of around 1.5 cm. The experiment utilized a 2 kg/h pilot-scale thermocatalytic reformation (TCR) machine at the University of Birmingham. Before initiating the TCR run, optimal process conditions, including constant pyrolysis and reforming temperatures, were established. The TCR rig incorporated essential components such as the hopper and feed tank. The sealed hopper, with a batch feed capacity of 7 kilograms, was thoroughly flushed with nitrogen to create an oxygen-free atmosphere before introducing the tank. The tank was loaded with 5 kilograms of pellets derived from dehydrated sewage sludge. The second reactor, an intermediate pyrolysis screw (auger) reactor, operated at 450°C, generating pyrolysis gas and char. The third reactor, a fixed bed reforming reactor, followed the pyrolysis process. Here, the pyrolysis gas and char underwent reformation at a temperature of 700°C, resulting in a reformed lower molecular weight condensable organic fraction and a syngas rich in H2. A U-tube shell and tube condenser were employed in the cooling system to cool both condensable and incondensable fractions from the reforming reactor. The condenser used a coolant mixture of water and glycol maintained at 5 degrees Celsius to ensure complete condensation of organic vapors. The syngas fraction not evaporated underwent further cooling using an ice-bath cooler, with the condensate collected. A comprehensive cleaning method removed impurities and aerosols, utilizing wash bottles with aqueous solutions for aerosol collection and a bottle with a fibrous filter for gas particle extraction. Post-cleaning, gas analysis using the Pollutek 3100 P gas analyzer detected pollutants before sending the gas to the flare, where it was incinerated with propane [108].

6.3. Conversion of Biomass into Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Using Fluidized Bed Pyrolysis

The research focused on investigating the production and characterization of bio-oil through fluidized bed pyrolysis, employing olive stones, pinewood, and torrefied feedstock [109]. The progress of the broader biorefinery sector, particularly in the aviation fuel industry, hinges on improvements in fluidized bed pyrolysis processes and analytical techniques. Statistical modeling of pyrolysis product yields and composition revealed the benefits of controlling operating temperature and feedstock choices during torrefaction, as well as the influence of catalyst addition in a fluidized bed reactor. The results suggest that pinewood pellets and bio-oil derived from the pyrolysis of olive stones at temperatures of 500 and 600 degrees Celsius, respectively, are optimal for fuel utilization. A comprehensive understanding of pyrolysis bio-oil composition requires the combined use of specific techniques such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, UV fluorescence, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and rheology. Technologically, key attributes of bio-oil included viscosity similar to fossil-derived oil, low levels of oxygen and water, and a well-balanced combination of aliphatic and aromatic compounds. These findings indicate that bio-oil from fluidized bed pyrolysis of biomasses holds significant potential for applications in the aviation industry and energy production [109].

6.4. Conversion of Waste Tyres into Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF)

Exploring discarded tires as a source for renewable and sustainable aircraft biofuels is a potential avenue to enhance sustainability in the aviation transport sector [110]. With fossil fuel resources diminishing and a rising global demand for fuel, the need for sustainable fuel sources is escalating. Waste tires, owing to their high calorific content, present a promising option for alternative fuels. Pyrolysis, an effective method for extracting gasoline or oil from waste tires, facilitates the efficient recycling of the energy contained in these discarded materials. This article delves into tests examining oils produced through pyrolysis from used tires, evaluating their suitability as fuel for airplane gas turbine engines. Gas turbine engines were subjected to tests using fuels derived from waste tires, either in their pure form or blended with base fuel in various ratios. The evaluation encompassed combustion characteristics, pollution, and engine performance, analyzing parameters such as static thrust, thrust-specific fuel consumption, turbine temperatures, air temperature, thrust-specific emission indices (CO, THC, NOx, SO2, and soot), as well as corrosion rate and hot deposit in the fuel injection line. Analysis of the data revealed that the utilization of waste tire pyrolysis oil in small gas turbine engines led to increased fuel consumption. Similar to jet fuel, tire pyrolysis oil releases carbon monoxide (CO) and total hydrocarbons (THC). While the emissions of SO2 were lower than those of jet fuel, there was a significant increase in NOx emissions. Despite these challenges, the high calorific value and favorable combustion properties of tire pyrolysis oil suggest its potential as an alternative fuel for gas turbine engines with minimal modifications [110].

6.5. Production of Very Pure Hydrogen from the Organic Portion of Municipal Solid Waste (OFMSW)

The outlined process integrates anaerobic digestion, pyrolysis, catalytic reforming, water-gas shift, and pressure swing adsorption technologies to generate renewable hydrogen from the organic fraction of municipal solid waste. This carbon-negative concept, detailed in a research paper [111], underwent development, evaluation, and feasibility analysis with a focus on Sweden. Optimal operating parameters, identified through sensitivity analysis, facilitated the processing of 1 ton of dry organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW), resulting in the production of 72.2 kg of hydrogen (H2) and the mitigation of 701.47 kg of negative carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent emissions. The process, requiring 325 kg of steam and 6621.4 MJ of energy, demonstrated economic viability in Stockholm, yielding an internal rate of return of 26% and a discounted payback period of 4.3 years, with negative CO2 equivalent emissions considered as income, as derived from the techno-economic analysis.

7. Upcoming Challenge

Several applications in the field of biology provide challenges that are currently feasible both economically and technically. To fully harness the capabilities of biomass pyrolysis technology and ensure its successful commercialization, further development and research are required. Despite significant advancements in pyrolysis technology in recent decades, it still faces numerous challenges, particularly in terms of commercialization. The technology remains distant and requires the resolution of various technological and economic constraints. The following are some of the significant obstacles that future biomass pyrolysis research must address:

Gaining a comprehensive understanding of the precise process of pyrolysis and the role played by its reactors.

Designing novel, cost-intensive reactors can yield significant gains in efficiency.

Research and create novel catalysts to enhance the quality of bio-oil.

It is necessary to establish a well-designed solar system.

To enhance the characteristics of bio-oil, it is necessary to implement post-pyrolysis processing.

Establish product value criteria derived from biomass pyrolysis, ensuring quality and comprehending potential opportunities.

Pyrolysis and bio-oil upgrading are expedited with a primary focus on efficiently producing and distributing lucrative end products.

8. Conclusions

Biomass pyrolysis is currently focused on cleaning up municipal solid waste with waste disposal and processing in agriculture and converting this waste into energy. This study identifies how pyrolysis can generate aircraft oil, including biofuels, from biomass with operating mode, as well as ways to select reactor containments. This review further shows the recent aviation piracy of energy plans and what could happen in the future, the technology preferred for world planning and its flexibility and large processing capacity has turned into a fluid bed way to further develop pyrolysis technology for future waste disposal. Sustainable aviation fuel production for biomass and waste is a new end ever and pioneering plants may face integration challenges in their design capabilities.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

MNU acknowledges Swinburne University of Technology to carry out the research project.

References

- Howarth, N.A.; Foxall, A. The Veil of Kyoto and the politics of greenhouse gas mitigation in Australia. Politi- Geogr. 2010, 29, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemichi, Y.; Hattori, M.; Itoh, T.; Nakamura, J.; Sugioka, M. Deactivation Behaviors of Zeolite and Silica−Alumina Catalysts in the Degradation of Polyethylene. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahirul,M. I.;Rasul,M.G.;Chowdhury,A.A.;Ashwath,N.Biofuelsproductionthroughbiomasspyrolysis—A technological review. Energies 2012, 5, 4952–5001 [CrossRef].

- Dharma, S.; Masjuki, H.H.; Ong, H.C.; Sebayang, A.H.; Silitonga, A.S.; Kusumo, F.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Optimization of biodiesel production process for mixed jatrophacurcas-ceibapentandra biodiesel using response surface methodology. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 115, 178–190 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumo, F.; Silitonga, A.S.; Masjuki, H.H.; Ong, H.C.; Siswantoro, J.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Optimization of transesterification process for ceibapentandra oil: A comparative study between kernel-based extreme learning machine and artificial neural networks. Energy 2017, 134, 24–34 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 9935.

- Demirbas¸, A. Partly chemical analysis of liquid fraction of flash pyrolysis products from biomass in the presence of sodium carbonate. Energy Convers. Manag. 2002, 43, 1801–1809 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, L.; Gulati, R.; Gupta, P. A comparative evaluation of the performance characteristics of a spark ignition engine using hydrogen and compressed natural gas as alternative fuels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2000, 25, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarelis, E.; Zabaniotou, A. Valorization of cotton stalks by fast pyrolysis and fixed bed air gasification for syngas production as precursor of second generation biofuels and sustainable agriculture. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 100, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Huang, H. Plasma Pyrolysis of Biomass for Production of Syngas and Carbon Adsorbent. Energy Fuels 2005, 19, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Yang, M.-H.; Yeh, T.-F.; Ger, M.-D. Catalytic degradation of high density polyethylene over mesoporous and microporous catalysts in a fluidised-bed reactor. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 86, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mašek, O.; Brownsort, P.; Cross, A.; Sohi, S. Influence of production conditions on the yield and environmental stability of biochar. Fuel 2013, 103, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarelis, E.; Zabaniotou, A. Valorization of cotton stalks by fast pyrolysis and fixed bed air gasification for syngas production as precursor of second generation biofuels and sustainable agriculture. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 100, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Review of fixed bed gasification systems for biomass. Agric. Eng. Int. 2007, 5, 1–23.

- Wang, L.; Weller, C.L.; Jones, D.D.; Hanna, M.A. Contemporary issues in thermal gasification of biomass and its application to electricity and fuel production. Biomass- Bioenergy 2008, 32, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Jain, A. A review of fixed bed gasification systems for biomass. 2007. Available online: https:// ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/10671/Invited?sequence=1 (accessed on 9 November 2018).

- Barker, S. Gasification and pyrolysis - routes to competitive electricity production from biomass in the UK. Energy Convers. Manag. 1996, 37, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippis, P.D.; Borgianni, C.; Paolucci, M.; Pochetti, F. Gasification process of Cuban bagasse in a two-stage reactor. Biomass Bioenergy 2004, 27, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, P.R.R. ConversãoPirolítica de Bagaço Residual da Indústria de Suco de Laranja e CaracterizaçãoQuímica dos Produtos. Ph.D. Thesis, UFSM, Santa Maria, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, P.; Xiong, Z.; Chang, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J. An experimental study on biomass air–steam gasification in a fluidized bed. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 95, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, B.S. Biomass to power rural development. Proceedings of National Seminar on Biomass Based Decentralized Power Generation; Pathak, B.S., Ed.; Sardar Patel Renewable Energy Research Institute: Vallabh Vidyanagar, India, 2005; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Biomass Fast Pyrolysis in a Fluidized Bed. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enscheda, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Biomass Fast Pyrolysis in a Fluidized Bed. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enscheda, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, S.S.; Russell, A.D.; Chase, H.A. Microwave pyrolysis, a novel process for recycling waste automotive engine oil. Energy 2010, 35, 2985–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Review of fixed bed gasification systems for biomass. Agric. Eng. Int. 2007, 5, 1–23.

- Corella, J.; Sanz, A. Modeling circulating fluidized bed biomass gasifiers. A pseudo-rigorous model for stationary state. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86, 1021–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, A.; Corella, J. Modeling circulating fluidized bed biomass gasifiers. Results from a pseudo-rigorous 1-dimensional model for stationary state. Fuel Process. Technol. 2006, 87, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleur, R.; Popovic, N.; Ikura, M.; Stanciulescu, M.; Liu, D. Characterization and potential applications of pyrolytic char from ablative pyrolysis of used tires. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2001, 58-59, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.B.; Snowden-Swan, L.J. Production of Gasoline and Diesel from Biomass via Fast Pyrolysis, Hydrotreating and Hydrocracking: 2012 State of Technology and Projections to 2017; Pacific Northwest National Lab. (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mašek, O.; Brownsort, P.; Cross, A.; Sohi, S. Influence of production conditions on the yield and environmental stability of biochar. Fuel 2013, 103, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corella, J.; Sanz, A. Modeling circulating fluidized bed biomass gasifiers. A pseudo-rigorous model for stationary state. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86, 1021–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, A.; Corella, J. Modeling circulating fluidized bed biomass gasifiers. Results from a pseudo-rigorous 1-dimensional model for stationary state. Fuel Process. Technol. 2006, 87, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U., Jr.; Steele, P.H. Pyrolysis of Wood/Biomass for Bio-oil: A Critical Review. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 848–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, E.A.; Holthuis, M.R. Clean Liquid Fuel through Flash Pyrolysis. In The Development of the PyRos Process; AFTUR Final Report; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, M.; Godbout, S.; Brar, S.K.; Solomatnikova, O.; Lemay, S.P.; Larouche, J.P. Biofuels Production from Biomass by Thermochemical Conversion Technologies. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2012, 2012, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarelis, E.; Zabaniotou, A. Valorization of cotton stalks by fast pyrolysis and fixed bed air gasification for syngas production as precursor of second generation biofuels and sustainable agriculture. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 100, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, T. Pyrolysis of Biomass. IEA Bioenergy: Task 34; Bioenergy Research Group, Aston University: Birmingham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dayton, D.C.; Turk, B.; Gupta, R. Syngas Cleanup, Conditioning, and Utilization. Thermochem. Process. Biomass 2019, 125–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Capareda, S.C.; Ashwath, N.; Kongkasawan, J. Experimental investigation of pyrolysis of rice straw using bench-scale auger, batch and fluidized bed reactors. Energy 2015, 93, 2384–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, B.M.; Duong, L.T.; Nguyen, V.D.; Tran, T.B.; Nguyen, M.H.; Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, D.A.; Luu, L.C. Evaluation of the production potential of bio-oil from Vietnamese biomass resources by fast pyrolysis. Biomass- Bioenergy 2014, 62, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, J.; Valdés, C.; Chejne, F.; Gómez, C.; Blanco, A.; Marrugo, G.; Osorio, J.; Castillo, E.; Aristóbulo, J.; Acero, J. Bio-oil production from Colombian bagasse by fast pyrolysis in a fluidized bed: An experimental study. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 112, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, A.A.; Daugaard, D.E.; Goldberg, N.M.; Hicks, K.B. Bench-Scale Fluidized-Bed Pyrolysis of Switchgrass for Bio-Oil Production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalf, C.; Nowakowski, D.; Harms, A.; Titiloye, J.; Bridgwater, A. A comparative study of straw, perennial grasses and hardwoods in terms of fast pyrolysis products. 108. [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.S.; Majerski, P.; Piskorz, J.; Radlein, D. A second look at fast pyrolysis of biomass—the RTI process. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1999, 51, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Lee, M.; Chang, Y. Fast pyrolysis of rice husk: Product yields and compositions. 98, 28. [CrossRef]

- Garcı̀a-Pèrez, M.; Chaala, A.; Roy, C. Vacuum pyrolysis of sugarcane bagasse. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2002, 65, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Nunez, J.A.; Pelaez-Samaniego, M.R.; Garcia-Perez, M.E.; Fonts, I.; Abrego, J.; Westerhof, R.J.M. Historical Developments of Pyrolysis Reactors: A Review. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 5751–5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Brech, Y.; Jia, L.; Cissé, S.; Mauviel, G.; Brosse, N.; Dufour, A. Mechanisms of biomass pyrolysis studied by combining a fixed bed reactor with advanced gas analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2016, 117, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, T.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, G. Technology of bio-oil preparation by vacuum pyrolysis of pine straw. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2013, 29, 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Schulzke, T.; Conrad, S.; Westermeyer, J. Fractionation of flash pyrolysis condensates by staged condensation. Biomass- Bioenergy 2016, 95, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, E.; Dahmen, N.; Weirich, F.; Reimert, R.; Kornmayer, C. Fast pyrolysis of lignocellulosics in a twin screw mixer reactor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 143, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutio, M.; Lopez, G.; Alvarez, J.; Olazar, M.; Bilbao, J. Fast pyrolysis of eucalyptus waste in a conical spouted bed reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 194, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, J.; Lopez, G.; Amutio, M.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Bio-oil production from rice husk fast pyrolysis in a conical spouted bed reactor. Fuel 2014, 128, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcìa-Pérez, M.; Chaala, A.; Pakdel, H.; Kretschmer, D.; Roy, C. Vacuum pyrolysis of softwood and hardwood biomass: Comparison between product yields and bio-oil properties. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2007, 78, 104–116 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanginés, P.; Domínguez, M.P.; Sánchez, F.; Miguel, G.S. Slow pyrolysis of olive stones in a rotary kiln: Chemical and energy characterization of solid, gas, and condensable products. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2015, 7, 043103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcìa-Pérez, M.; Chaala, A.; Pakdel, H.; Kretschmer, D.; Roy, C. Vacuum pyrolysis of softwood and hardwood biomass: Comparison between product yields and bio-oil properties. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2007, 78, 104–116 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N.MiskolcziaA.AngyalaL.BarthaaI.ValkaibUniversity of Pannonia, Department of Hydrocarbon and Coal Processing, H-8200 Veszprém, Egyetem u.10.

- Laird, D.A.; Brown, R.C.; Amonette, J.E.; Lehmann, J. Review of the pyrolysis platform for coproducing bio-oil and biochar. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefining 2009, 3, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3000; 72.

- Manyà, J.J. Pyrolysis for Biochar Purposes: A Review to Establish Current Knowledge Gaps and Research Needs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 7939–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.iata.

- Uddin, N.; Rashid, M.M.; Rahman, M.T.; Hossain, B.; Salam, S.M.; A Nithe, N. Custom MPPT design of solar power switching network for racing car. 2015 18th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, BangladeshDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 11–16.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., & Mostafa, M. G. (2016). Development of automatic fish feeder. Global Journal of Research In Engineering.

- Uddin, N.; Rashid, M.M.; Rubaiyat, M.; Hossain, B.; Salam, S.M.; A Nithe, N. Comparison of position sensorless control based back-EMF estimators in PMSM. 2015 18th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, BangladeshDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 5–10.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rahman, M. A., & Sir, M. (2016). Reduce generators noise with better performance of a diesel generator set using modified absorption silencer. Global Journal of Research In Engineering.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., Aziz, M. A., & Nithe, N. A. (2016). Maximum Power Point Charge Controller for DC-DC Power Conversionin Solar PV System. Global Journal of Research In Engineering.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. A. ( 1(1), 23–30.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., Mostafa, M. G., Belayet, H., Salam, S. M., & Nithe, N. A. (2016). New Energy Sources: Technological Status and Economic Potentialities. Global Journal of Science Frontier Research, 16(1), 24-37.

- Uddin, M.; Rashid, M.; Tahir, A.M.; Parvez, M.; Elias, M.; Sultan, M. ; Raddadi Hybrid Fuzzy and PID controller based inverter to control speed of AC induction motor. 2015 International Conference on Electrical & Electronic Engineering (ICEEE). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, BangladeshDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 9–12.

- Aziz, M. A. , Shams, F., Rashid, M. M., & Uddin, M. (2015). Design and development of a compressed air machine using a compressed air energy storage system. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 10(23), 17332- 17336.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., & Mostafa, M. G. (2016). Development of Controller for TE in Force Adjustable Damper. Global Journal of Research In Engineering.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., Nithe, N. A., & Rony, J. I. Performance and Cost Analysis of Diesel Engine with Different Mixing Ratio of Raw Vegetable Oil and Diesel Fuel. In Proceedings of the International Conference Biotechnology Engineering, ICBioE (Vol. 16).

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., Mostafa, M. G., & Nayen, M. J. Development of An Absorption Silencer for Generator's Noise Reducing.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., & Nithe, N. A. (2006). Low Voltage Distribution Level three terminal UPFC based voltage Regulator for Solar PV System. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 10(22).

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M., Mostafa, M., Nithe, N., & Rahman, M. (2016). Effects of Energy on Economy, Health and Environment.

- Uddin, N. , Rashid, M. M., Mostafa, M. G., Belayet, H., Salam, S. M., Nithe, N. A.,... & Halder, S. (2016). Development of Voice Recognition for Student Attendance. Global Journal of HumanSocial Science Research: G Linguistics & Education, 16(1), 1-6.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. Z. ( 16(1), 1–9.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., & Mostafa, M. G. (2016). Global energy: need, present status, future trend and key issues. Global Journal of Research In Engineering.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., & Mostafa, M. G. (2016). ECG Arryhthmia Classifier. Global Journal of Research In Engineering.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., Parvez, M., Sultan, M. M., Ahmed, S. Z., Nithe, N. A.,... & Rahman, M. T. (2016). Two Degree-Of-Freedom Camera Support System. Global Journal of Computer Science and Technology.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rashid, M. M., & Mostafa, M. G. (2016). Design & Development of Electric Cable Inspection. Global Journal of Research In Engineering.

- Uddin, M. N. , Rahman, M. A., Rashid, M. M., Nithe, N. A., & Rony, J. I. (2016). A Mechanism Concept and Design of Reconfigurable Robot for Rescue Operation. Global Journal of Research In Engineering.

- Rahman, M. , Rasul, M. G., Hassan, N. M. S., Azad, A. K., & Uddin, M. (2017). Effect of small proportion of butanol additive on the performance, emission, and combustion of Australian native first-and second-generation biodiesel in a diesel engine. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24(28), 22402-22413.

- Ahmed, R.; Haque, A.; Hossain, K.; Uddin, M.N. Development of a Controlled Output Wind Turbine. Saudi J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 7, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Ahmed, R.; Hossain, K.; Haque, A.; Ahmed, R.; Sultana, N.; Uddin, N. Assessment of WDM Based RoF Passive Optical Network. Saudi J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 7, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabuddin, M. , Uddin, M. N., Chowdhury, J. I., Ahmed, S. F., Uddin, M. N., Mofijur, M., & Uddin, M. A. (2022). A review of the recent development, challenges, and opportunities of electronic waste (e-waste). International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 1-8.

- Uddin, M.; Rahman, M.; Taweekun, J.; Techato, K.; Mofijur, M.; Rasul, M. Enhancement of biogas generation in up-flow sludge blanket (UASB) bioreactor from palm oil mill effluent (POME). Energy Procedia 2019, 160, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. , A.; A., K.; C., R.K.; S., R.; T.R., P. Lowest emission sustainable aviation biofuels as the potential replacement for the Jet-A fuels. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2020, 93, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, J.A.; Mukherjee, A.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Kozinski, J.A. Next-generation biofuels and platform biochemicals from lignocellulosic biomass. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 14145–14169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, J.A.; Epelle, E.I.; Tabat, M.E.; Orivri, U.; Amenaghawon, A.N.; Okoye, P.U.; Gunes, B. Waste biomass valorization for the production of biofuels and value-added products: A comprehensive review of thermochemical, biological and integrated processes. 159. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Wu, X. Dynamic growth models for Caragana korshinskii shrub biomass in china. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 269, 110675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, W.; Lei, H.; Villota, E.; Qian, M.; Zhao, Y.; Huo, E.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, X.; Wang, C.; Huang, Z. Synthesis and characterization of sulfonated activated carbon as a catalyst for bio-jet fuel production from biomass and waste plastics. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 297, 122411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. , Li, J., Santana-Santos, L., Shuda, M., Sobol, R.W., Van Houten, B., Qian, W., Wang, T., and Li, Q. (2015). Preparation of jet fuel range hydrocarbons by catalytic transformation of bio-oil derived from fast pyrolysis of straw stalk. Energy 9, 488–502. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Wu, X. Dynamic growth models for Caragana korshinskii shrub biomass in china. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 269, 110675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson, A.G., Jr. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.S.; Sharma, S.; Chaudhary, D.K.; Panthi, P.; Pokhrel, P.; Shrestha, A.; Mandal, P.K. Bacteriological profile of neonatal sepsis and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of isolates admitted at Kanti Children’s Hospital Kathmandu Nepal. BMC Res Notes BioMed Central. 2018, 11, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, J.A.; Awotoye, D.; Tabat, M.E.; Okoye, P.U.; Epelle, E.I.; Ogbaga, C.C.; Güleç, F.; Oboirien, B. Multi-criteria decision analysis for the evaluation and screening of sustainable aviation fuel production pathways. iScience 2023, 26, 106944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailos, S.; Bridgwater, A. A comparative techno-economic assessment of three bio-oil upgrading routes for aviation biofuel production. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 7206–7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, AV. Renewable fuels and chemicals by thermal pro-cessing of biomass.Chem Eng J. 2003;91(2–3):87-102.

- Bridgwater AV, Meier D, Radlein D.Fast pyrolysis of biomass: ahandbook. 1]: [...] Newbury: CPL Press; 2008;30:188.

- Bridgwater, A.V. Upgrading biomass fast pyrolysis liquids. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2012, 31, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonti, D.; Prussi, M.; Buffi, M.; Tacconi, D. Sustainable bio kerosene: Process routes and industrial demonstration activities in aviation biofuels. Appl. Energy 2014, 136, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, WC. Techno-economic analysis of a bio-refinery processfor producing hydro-processed renewable jet fuel from Jatropha.Renew Energy[Internet]. Elsevier Ltd. 2016;95:63-73.

- van Dyk, S.; Su, J.; Ebadian, M.; O’connor, D.; Lakeman, M.; Saddler, J. (. Potential yields and emission reductions of biojet fuels produced via hydrotreatment of biocrudes produced through direct thermochemical liquefaction. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratton, R.W.; Wong, H.M.; Hileman, J.I. Quantifying Variability in Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Inventories of Alternative Middle Distillate Transportation Fuels. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4637–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, G.; Ronsse, F.; van Duren, R.; Prins, W. Challenges in the design and operation of processes for catalytic fast pyrolysis of woody biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1596–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.A.; Lima, S.; Jahangiri, H.; Majewski, A.J.; Hofmann, M.; Hornung, A.; Ouadi, M. A step change towards sustainable aviation fuel from sewage sludge. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 163, 105498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubetskaya, A.; von Berg, L.; Johnson, R.; Moore, S.; Leahy, J.; Han, Y.; Lange, H.; Anca-Couce, A. Production and characterization of bio-oil from fluidized bed pyrolysis of olive stones, pinewood, and torrefied feedstock. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunerhan, A.; Altuntas, O.; Caliskan, H. Utilization of renewable and sustainable aviation biofuels from waste tyres for sustainable aviation transport sector. Energy 2023, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Shi, Z.; Zaini, I.N.; Wen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Jönsson, P.G.; Yang, W. Renewable hydrogen production from the organic fraction of municipal solid waste through a novel carbon-negative process concept. Energy 2022, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).