Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

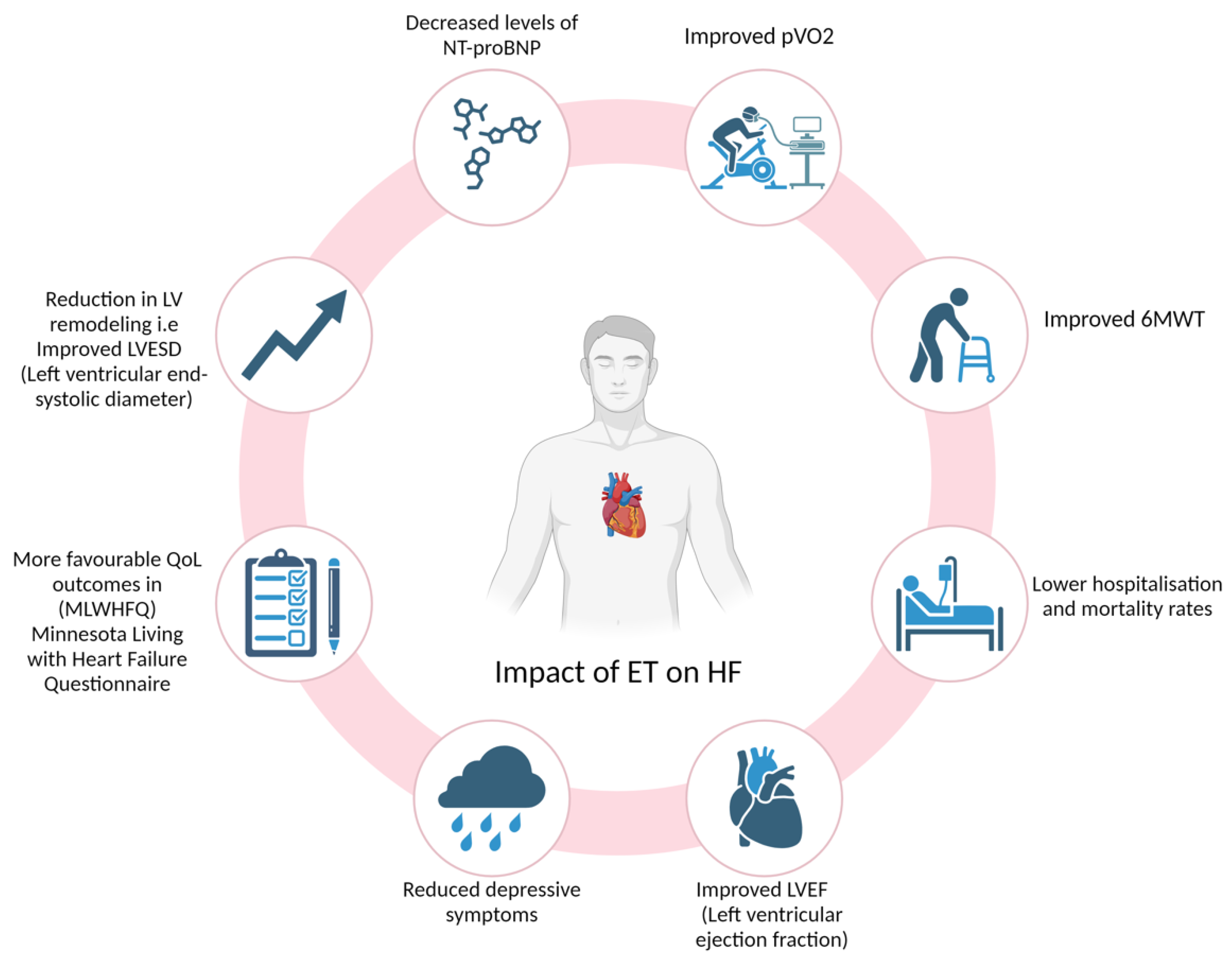

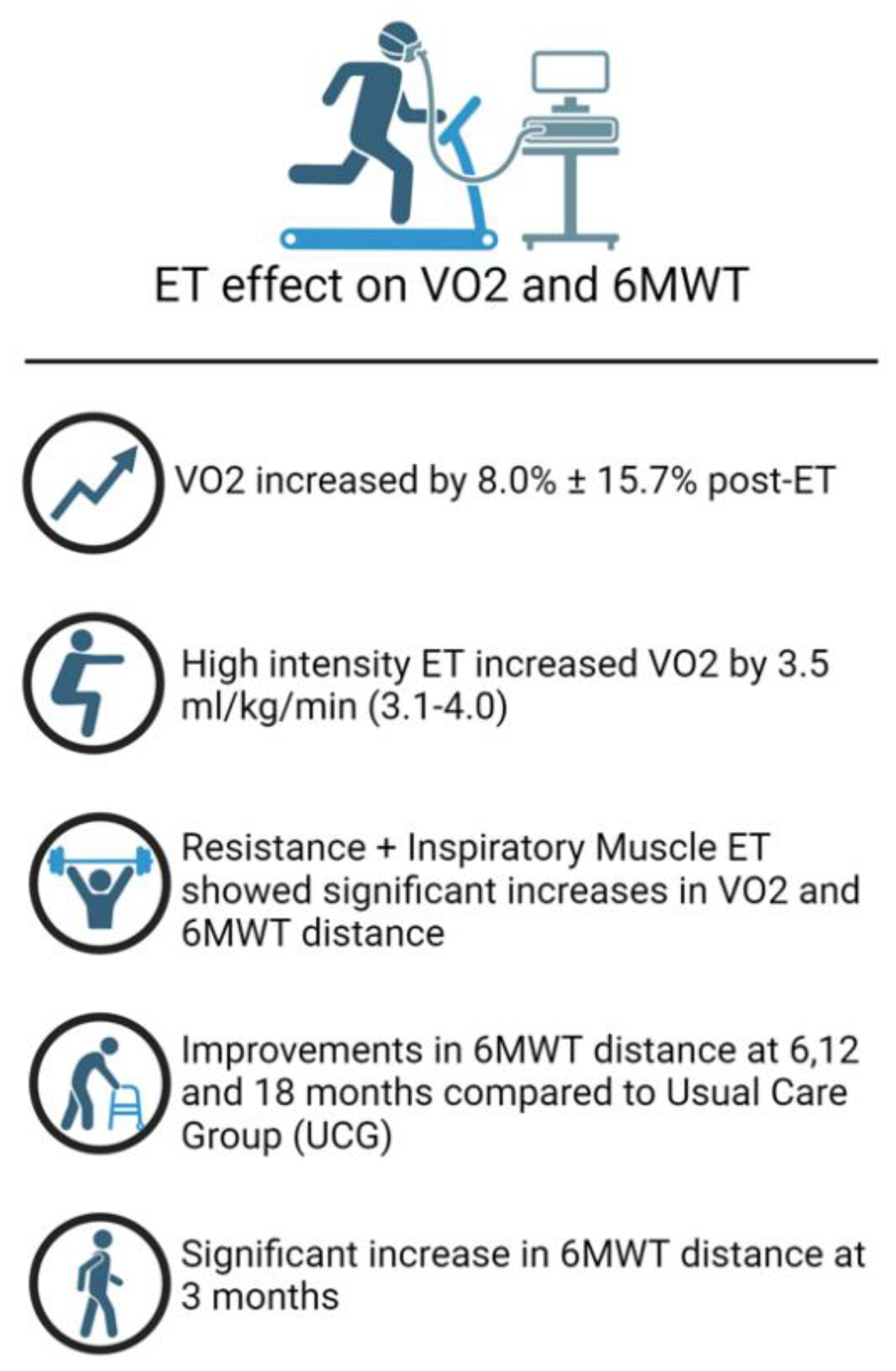

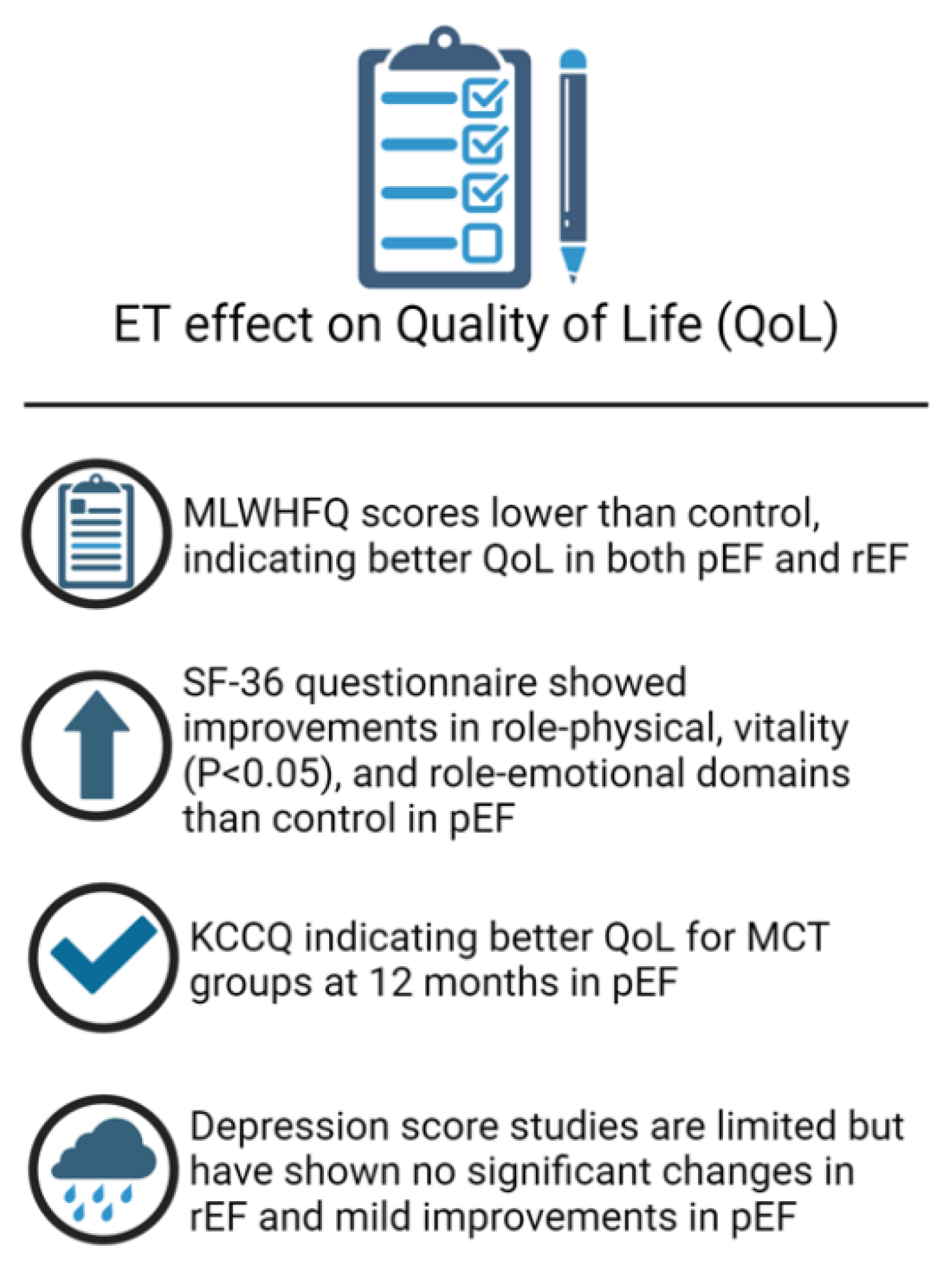

Heart Failure (HF) is a prevalent condition which places a substantial burden on healthcare systems worldwide. Pharmacological therapy structures the cornerstone of management in HF reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), beta blockers (BB), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) and sodium/glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which all improve survival rates. Mortality reduction with pharmacological treatments in HF preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are yet to be established. Cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training can play an important role in both HFrEF and HFpEF. Cardiac rehabilitation significantly improves functional capacity, exercise duration and quality of life. Exercise training has shown beneficial effects on peak oxygen consumption (pVO2) and 6-minute walk test distance in HFrEF and HFpEF patients as well as a reduction in hospitalisation and mortality rates. ET also has been shown to have beneficial effects on depression and anxiety levels. High intensity training and moderate continuous training have both shown benefit, while resistance exercise training and ventilatory assistance may also be beneficial. ET adherence rates are higher when enrolled to a supervised programme but prescription rates remain low worldwide. Further research is required to establish the most efficacious exercise prescriptions in patients with HFrEF and HFpEF, but personalised exercise regimens should be considered as part of HF management.

Keywords:

Introduction

Pathophysiology

Functional Assessment in Heart Failure

Optimising Functional Capacity in Heart Failure

The Role of Cardiac Rehabilitation Programmes

Efficacy of exercise training in HFpEF

Efficacy of exercise training in HFrEF

Resistance exercise training modality

Ventilatory assistance

Exercise Training and Quality of Life in Heart Failure

Studies assessing QOL following ET in HFpEF

Studies assessing QOL following ET in HFrEF

Adherence to Exercise Training

HFpEF

HFrEF

Prescription rates

Conclusions and Recommendations

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano GM, C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovascular research 2023, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, M.; Vaes, B.; Mamouris, P.; Van Den Akker, M.; Van Pottelbergh, G.; Goderis, G. , et al. Burden of heart failure in Flemish general practices: a registry-based study in the Intego database. BMJ open 2019, 9, e022972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Riet, E.E.; Hoes, A.W.; Wagenaar, K.P.; Limburg, A.; Landman, M.A.; Rutten, F.H. Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. European journal of heart failure 2016, 18, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redfield, M.M.; Borlaug, B.A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JAMA 2023, 329, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Gatti, P.; Benson, L.; Adamo, M.; Chioncel, O.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G. , et al. Left ventricular ejection fraction digit bias and reclassification of heart failure with mildly reduced vs reduced ejection fraction based on the 2021 definition and classification of heart failure. American heart journal 2024, 267, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theresa A McDonagh, Marco Metra, Marianna Adamo, Roy S Gardner, Andreas Baumbach, Michael Böhm, Haran Burri, Javed Butler, Jelena Čelutkienė, Ovidiu Chioncel, John G F Cleland, Maria Generosa Crespo-Leiro, Dimitrios Farmakis, Martine Gilard, Stephane Heymans, Arno W Hoes, Tiny Jaarsma, Ewa A Jankowska, Mitja Lainscak, Carolyn S P Lam, Alexander R Lyon, John J V McMurray, Alexandre Mebazaa, Richard Mindham, Claudio Muneretto, Massimo Francesco Piepoli, Susanna Price, Giuseppe M C Rosano, Frank Ruschitzka, Anne Kathrine Skibelund, ESC Scientific Document Group. Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European Heart Journal 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [CrossRef]

- Chioncel, O.; Lainscak, M.; Seferovic, P.M.; Anker, S.D.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Harjola, V.P. , et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. European journal of heart failure 2017, 19, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.; Morley, J.E.; Schols, A.; Ferrucci, L.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dent, E.; Baracos, V.E.; Crawford, J.A.; Doehner, W.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Jatoi, A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Lainscak, M.; Landi, F.; Laviano, A.; Mancuso, M.; Muscaritoli, M.; Prado, C.M.; Strasser, F.; von Haehling, S.; Coats AJ, S.; Anker, S.D. Sarcopenia: A Time for Action. An SCWD Position Paper. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, A.; Saitoh, M.; Valentova, M.; Sandek, A.; Evertz, R.; Ebner, N.; Loncar, G.; Springer, J.; Doehner, W.; Lainscak, M.; Hasenfuß, G; Anker, S. D.; von Haehling, S. Comparison of sarcopenia and cachexia in men with chronic heart failure: results from the Studies Investigating Co-morbidities Aggravating Heart Failure (SICA-HF). Eur J Heart Fail 2018, 20, 1580–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fülster, S.; Tacke, M.; Sandek, A.; Ebner, N.; Tschöpe, C.; Doehner, W.; Anker, S.D.; von Haehling, S. Muscle wasting in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the studies investigating co-morbidities aggravating heart failure (SICA-HF). Eur Heart J 2013, 34, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

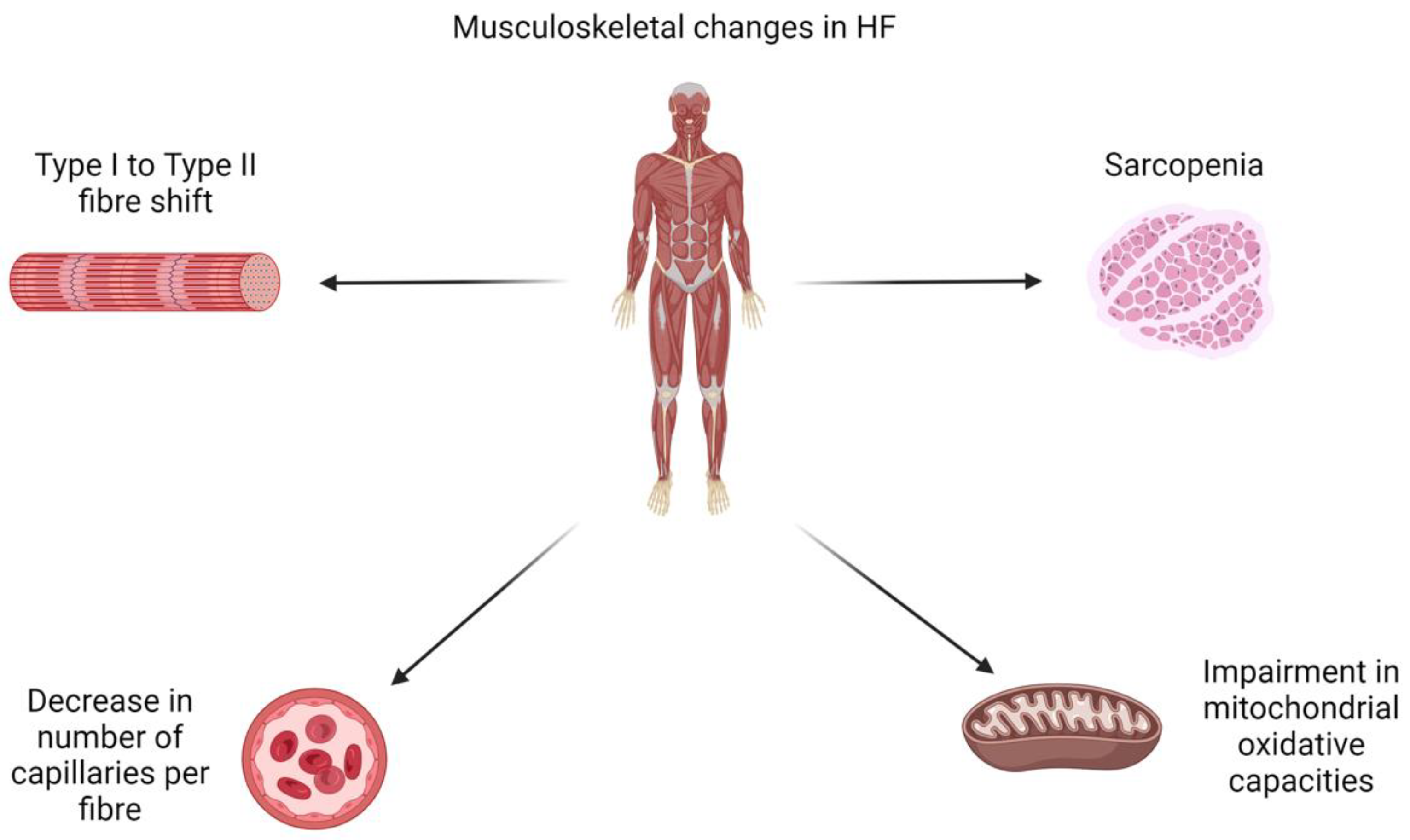

- Adams, V.; Linke, A.; Winzer, E. Skeletal muscle alterations in HFrEF vs. HFpEF. Current heart failure reports 2017, 14, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wing, S.S.; Lecker, S.H.; Jagoe, R.T. Proteolysis in illness-associated skeletal muscle atrophy: from pathways to networks. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences 2011, 48, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadey, C.A.; Barker, A.R.; Stuart, G.; Tran, D.L.; Laohachai, K.; Ayer, J. , et al. Scaling Peak Oxygen Consumption for Body Size and Composition in People With a Fontan Circulation. Journal of the American Heart Association 2022, 11, e026181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, M.; Castillo-Rodriguez, C.; Soliman, D.; Del Rio-Pertuz, G.; Nugent, K. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Heart Failure. Journal of cardiovascular development and disease 2024, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostagno, C.; Gensini, G.F. Six minute walk test: a simple and useful test to evaluate functional capacity in patients with heart failure. Internal and emergency medicine 2008, 3, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L.G.; Swedberg, K.; Clark, A.L.; Witte, K.K.; Cleland, J.G. Six minute corridor walk test as an outcome measure for the assessment of treatment in randomized, blinded intervention trials of chronic heart failure: a systematic review. European heart journal 2005, 26, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opasich, C.; Pinna, G.D.; Mazza, A.; Febo, O.; Riccardi, R.; Riccardi, P.G.; Capomolla, S.; Forni, G.; Cobelli, F.; Tavazzi, L. Six-minute walking performance in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure; is it a useful indicator in clinical practice? European heart journal 2001, 22, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittner, V.; Weiner, D.H.; Yusuf, S.; Rogers, W.J.; McIntyre, K.M.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Kronenberg, M.W.; Kostis, J.B.; Kohn, R.M.; Guillotte, M. Prediction of mortality and morbidity with a 6-minute walk test in 1993. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Denfeld, Q.E.; Winters-Stone, K.; Mudd, J.O.; Gelow, J.M.; Kurdi, S.; Lee, C.S. The prevalence of frailty in heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2017, 236, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecka-Dabrowa, A.; Ebner, N.; Dos Santos, M.R.; Ishida, J.; Hasenfuss, G.; von Haehling, S. Cachexia, muscle wasting, and frailty in cardiovascular disease. Eur J Heart Fail 2020, 22, 2314–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidán, M.T.; Blaya-Novakova, V.; Sánchez, E.; Ortiz, J.; Serra-Rexach, J.A.; Bueno, H. Prevalence and prognostic impact of frailty and its components in non-dependent elderly patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016, 18, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewan, P.; Jackson, A.; Jhund, P.S.; Shen, L.; Ferreira, J.P.; Petrie, M.C.; Abraham, W.T.; Desai, A.S.; Dickstein, K.; Køber, L.; Packer, M.; Rouleau, J.L.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; Zile, M.R.; McMurray JJ, V. The prevalence and importance of frailty in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction - an analysis of PARADIGM-HF and ATMOSPHERE. Eur J Heart Fail 2020, 22, 2123–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, N.A.; Supiano, M.A.; Lewis, E.F.; Liu, J.; Claggett, B.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Desai, A.S.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Solomon, S.D.; Fang, J.C. The frailty syndrome and outcomes in the TOPCAT trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2018, 20, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.P.; Conceição, L.S.; Martins-Filho, P.R.; de Santana Motta, D.R.; Carvalho, V.O. Effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in individuals with heart failure with preserved Ejection Fraction: A systematic review. Journal of Cardiac Failure 2018, 24, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagel, P.S.; Tawil, J.N.; Boettcher, B.T.; Izquierdo, D.A.; Lazicki, T.J.; Crystal, G.J. , et al. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Comprehensive Review and Update of Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Perioperative Implications. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia 2021, 35, 1839–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayat, E.; Arrigo, M.; Littnerova, S.; Sato, N.; Parenica, J.; Ishihara, S.; Spinar, J.; Müller, C.; Harjola, V.P.; Lassus, J.; Miró, Ò; Maggioni, A.P.; AlHabib, K.F.; Choi, D.J.; Park, J.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Januzzi, J.L.; Jr Kajimoto, K.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Mebazaa, A. Heart failure oral therapies at discharge are associated with better outcome in acute heart failure: a propensity-score matched study. Eur J Heart Fail 2018, 20, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Anker, S.D.; Maggioni, A.P.; Coats, A.J.; Filippatos, G.; Ruschitzka, F.; Ferrari, R.; Piepoli, M.F.; Delgado Jimenez, J.F.; Metra, M.; Fonseca, C.; Hradec, J.; Amir, O.; Logeart, D.; Dahlström, U.; Merkely, B.; Drozdz, J.; Goncalvesova, E.; Hassanein, M.; Chioncel, O.; Lainscak, M.; Seferovic, P.M.; Tousoulis, D.; Kavoliuniene, A.; Fruhwald, F.; Fazlibegovic, E.; Temizhan, A.; Gatzov, P.; Erglis, A.; Laroche, C.; Mebazaa, A. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail 2016, 18, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R.; Rouleau, J.L.; Shi, V.C.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; Zile, M.R. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlay, S.; Roger, V.; Redfield, M. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017, 14, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray JJ, V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A. , et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. The New England journal of medicine 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Shi, S.; Xu, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, B.; Song, Q. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial remodeling in heart failure: An update on mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2022, 155, 113833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, H. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on the peripheral circulation in heart failure. The American Journal of Cardiology 1992, 70, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfatto, G.; Ravaro, S.; Caravita, S.; Baratto, C.; Sorropago, A.; Giglio, A.; Villani, A. Improvement of functional capacity in sacubitril-valsartan treated patients assessed by cardiopulmonary exercise test. Acta Cardiologica 2019, 75, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, G.; Vitale, G.; Ajello, L.; Agnese, V.; Bellavia, D.; Caccamo, G.; Corrado, E.; Di Gesaro, G.; Falletta, C.; La Franca, E.; Minà, C; Storniolo, S.A.; Sarullo, F.M.; Clemenza, F. The Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan on Clinical, Biochemical and Echocardiographic Parameters in Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: The "Hemodynamic Recovery". Journal of clinical medicine 2019, 8, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbenetz, N.M.; Mrkobrada, M. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC cardiovascular disorders 2016, 16, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M. , et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Choi, D.J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; Giannetti, N.; Gomez-Mesa, J.E.; Janssens, S.; Januzzi, J.L.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; Merkely, B.; Nicholls, S.J.; Perrone, S.V.; Piña, I.L.; Ponikowski, P. , … EMPEROR-Preserved Trial Investigators Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. The New England journal of medicine 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankowski, R.; Kotwica, T.; Szyszka, A.; Przewłocka-Kosmala, M.; Sacharczuk, W.; Karolko, B.; Kobusiak-Prokopowicz, M.; Mysiak, A.; Kosmala, W. Determinants of the beneficial effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism on exercise capacity in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Kardiologia Polska 2018, 76, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palau, P.; Seller, J.; Domínguez, E.; et al. Effect of β-Blocker Withdrawal on Functional Capacity in Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC 2021, 78, 2042–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, A.K.; Abdelgalil, M.S.; Gonnah, A.R.; Mouffokes, A.; Ahmad, U.; Awad, A.K. , et al. Intravenous Iron for Acute and Chronic Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF) Patients with Iron Deficiency: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical medicine (London, England) Advance online publication. 2024, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pina, I.L.; Apstein, C.S.; Balady, G.J. , et al. Exercise and heart failure: a statement from the American Heart Association Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention.Circulation. 2003, 107, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, C.M.; Whellan, D.J.; Lee, K.L. , et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial.JAMA. 2009, 301, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, D.E.; Sanderson, B.K.; Josephson, R.A. , et al. Heart failure as a newly approved diagnosis for cardiac rehabilitation: challenges and opportunities.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2652–2659. [Google Scholar]

- Hieda, M.; Sarma, S.; Hearon, C.M.; Jr MacNamara, J.P.; Dias, K.A.; Samels, M. , et al. One-Year Committed Exercise Training Reverses Abnormal Left Ventricular Myocardial Stiffness in Patients With Stage B Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2021, 144, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donelli da Silveira, A.; Beust de Lima, J.; da Silva Piardi, D.; Dos Santos Macedo, D.; Zanini, M.; Nery, R. , et al. High-intensity interval training is effective and superior to moderate continuous training in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. European journal of preventive cardiology 2020, 27, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management, NICE guideline [NG106]. 2018. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106.

- Shabeer, H.; Samore, N.; Ahsan, S.; Gondal MU, R.; Shah BU, D.; Ashraf, A. , et al. Safety and Efficacy of Ferric Carboxymaltose in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Iron Deficiency. Current problems in cardiology 2024, 49(1 Pt C), 102125. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, S.; Winzer, E.B.; Duvinage, A.; Gevaert, A.B.; Edelmann, F.; Haller, B. , et al. Effect of High-Intensity Interval Training, Moderate Continuous Training, or Guideline-Based Physical Activity Advice on Peak Oxygen Consumption in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brubaker, P.H.; Avis, T.; Rejeski, W.J.; Mihalko, S.E.; Tucker, W.J.; Kitzman, D.W. Exercise Training Effects on the Relationship of Physical Function and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Older Heart Failure Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention 2020, 40, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, W.W.; Kupzyk, K.A.; Norman, J.F.; Lundgren, S.W.; Fisher, A.; Lindsey, M.L. , et al. The HEART Camp Exercise Intervention Improves Exercise Adherence, Physical Function, and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Adults With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure. Journal of cardiac failure 2022, 28, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Kitzman, D.W.; Brubaker, P.; Haykowsky, M.J.; Morgan, T.; Becton, J.T. , et al. Response to Endurance Exercise Training in Older Adults with Heart Failure with Preserved or Reduced Ejection Fraction. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2017, 65, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska, E.A.; Wegrzynowska, K.; Superlak, M.; Nowakowska, K.; Lazorczyk, M.; Biel, B.; Kustrzycka-Kratochwil, D.; Piotrowska, K.; Banasiak, W.; Wozniewski, M.; Ponikowski, P. The 12-week progressive quadriceps resistance training improves muscle strength, exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2008, 130, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.C.; Smith, K.; Wingham, J.; Eyre, V.; Greaves, C.J.; Warren, F.C. , et al. A randomised controlled trial of a facilitated home-based rehabilitation intervention in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and their caregivers: the REACH-HFpEF Pilot Study. BMJ open 2018, 8, e019649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andryukhin, A.; Frolova, E.; Vaes, B.; Degryse, J. The impact of a nurse-led care programme on events and physical and psychosocial parameters in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial in primary care in Russia. European Journal of General Practice 2010, 16, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connor, C.M.; Whellan, D.J.; Lee, K.L.; Keteyian, S.J.; Cooper, L.S.; Ellis, S.J. , et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 301, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besnier, F.; Labrunée, M.; Richard, L.; Faggianelli, F.; Kerros, H.; Soukarié, L. , et al. Short-term effects of a 3-week interval training program on Heart Rate Variability in chronic heart failure. A randomised controlled trial. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2019, 62, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, Ø.; Halle, M.; Conraads, V.; Støylen, A.; Dalen, H.; Delagardelle, C. , et al. High-Intensity Interval Training in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2017, 135, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laoutaris, I.D.; Piotrowicz, E.; Kallistratos, M.S.; Dritsas, A.; Dimaki, N.; Miliopoulos, D. , et al. Combined aerobic/resistance/inspiratory muscle training as the ‘optimum’ exercise programme for patients with chronic heart failure: Aristos-HF randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2020, 28, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conraads, V.; Beckers, P.; Vaes, J.; Martin, M.; Vanhoof, V.; Demaeyer, C. , et al. Combined endurance/resistance training reduces NT-probnp levels in patients with chronic heart failure. European Heart Journal 2004, 25, 1797–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.W.; Wang, C.Y.; Lai, Y.H.; Liao, Y.C.; Wen, Y.K.; Chang, S.T. , et al. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation improves quality of life, aerobic capacity, and readmission rates in patients with chronic heart failure. Medicine 2018, 97, e9629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tcheugui, J.B.; Zhang, S.; McEvoy, J.W.; Ndumele, C.E.; Hoogeveen, R.C.; Coresh, J.; Selvin, E. Elevated NT-ProBNP as a Cardiovascular Disease Risk Equivalent: Evidence from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. The American journal of medicine 2022, 135, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rørth, R.; Jhund, P.S.; Yilmaz, M.B.; Kristensen, S.L.; Welsh, P.; Desai, A.S.; Køber, L.; Prescott, M.F.; Rouleau, J.L.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; Zile, M.R.; Packer, M.; McMurray, J.J.V. Comparison of BNP and NT-proBNP in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation. Heart failure 2020, 13, e006541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C. NT-ProBNP: the mechanism behind the marker. Journal of cardiac failure 2005, 11(5 Suppl), S81–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zureigat, H.; Osborne, M.; Abohashem, S.; et al. Effect of Stress-Related Neural Pathways on the Cardiovascular Benefit of Physical Activity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024, 83, 1543–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, D.K.; Dickson, V.; Jaarsma, T.; Lee, C.; Stromberg, A.; Riegel, B. Role of self-care in the patient with heart failure. Current cardiology reports 2012, 14, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiatarone, M.A.; O'Neill, E.F.; Ryan, N.D.; Clements, K.M.; Solares, G.R.; Nelson, M.E.; Roberts, S.B.; Kehayias, J.J.; Lipsitz, L.A.; Evans, W.J. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl J Med 1994, 330, 1769–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, B.T.; Bradley, L.A.; Dempsey, T.M.; Puro, A.C.; Adams, J.Y. Management of Mechanical Ventilation in Decompensated Heart Failure. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Donnell, D.E.; D'Arsigny, C.; Raj, S.; Abdollah, H.; Webb, K.A. Ventilatory assistance improves exercise endurance in stable congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999, 160, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraballo, C.; Desai, N.R.; Mulder, H.; Alhanti, B.; Wilson, F.P.; Fiuzat, M.; Felker, G.M.; Piña, I.L.; O'Connor, C.M.; Lindenfeld, J.; Januzzi, J.L.; Cohen, L.S.; Ahmad, T. Clinical Implications of the New York Heart Association Classification. Journal of the American Heart Association 2019, 8, e014240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Minnesota. Minnesota LIVING WITH HEART FAILURE Questionnaire (MLHFQ). Available Technologies. 2024. Available online: https://license.umn.edu/product/minnesota-living-with-heart-failure-questionnaire-mlhfq.

- Spertus, J.A.; Jones, P.G.; Sandhu, A.T.; Arnold, S.V. Interpreting the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in clinical trials and clinical care. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 76, 2379–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual Framework and Item Selection. Medical Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, J.F.; Kupzyk, K.A.; Artinian, N.T.; Keteyian, S.J.; Alonso, W.S.; Bills, S.E.; Pozehl, B.J. The influence of the HEART Camp intervention on physical function, health-related quality of life, depression, anxiety and fatigue in patients with heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 2020, 19, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysohoou, C.; Tsitsinakis, G.; Vogiatzis, I.; Cherouveim, E.; Antoniou, C.; Tsiantilas, A. , et al. High intensity, interval exercise improves quality of life of patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized controlled trial. QJM 2013, 107, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villareal, D.T.; Aguirre, L.; Gurney, A.B.; Waters, D.L.; Sinacore, D.R.; Colombo, E.; Armamento-Villareal, R.; Qualls, C. Aerobic or Resistance Exercise, or Both, in Dieting Obese Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 1943–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brubaker, P.H.; Moore, J.B.; Stewart, K.P.; Wesley, D.J.; Kitzman, D.W. Endurance exercise training in older patients with heart failure: results from a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2009, 57, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha, K.; Allen, C.J.; Chawla, S.; Pryse-Hawkins, H.; Fallon, L.; Chambers, V. , et al. Audit of a tertiary heart failure outpatient service to assess compliance with NICE guidelines. Clinical medicine (London, England) 2016, 16, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Binno, S.; Corrà, U; Seferovic, P.; Conraads, V.; Jaarsma, T. et al. ExtraHF survey: The first european survey on implementation of exercise training in heart failure patients. European Journal of Heart Failure 2015, 17, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keteyian, S.J.; Michaels, A. Heart failure in cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention 2022, 42, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scaling Peak Oxygen Consumption for Body Size and Composition in People With a Fontan Circulation (13) | One-Year Committed Exercise Training Reverses Abnormal Left Ventricular Myocardial Stiffness in Patients With Stage B Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (44) | High-intensity interval training is effective and superior to moderate continuous training in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial (45) | Effect of High-Intensity Interval Training, Moderate Continuous Training, or Guideline-Based Physical Activity Advice on Peak Oxygen Consumption in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Randomized Clinical Trial (48) | |

| Study type | Secondary data analysis | RCT | RCT | RCT |

| Method | Ratio and allometric (log-linear regression) scaling of VO2peak to BM, stature, body surface area and fat free mass (n=89) | High-intensity exercise training HIIT (n=30) or attention control (n=16) | HIIT (n=10) vs MCT (n=9) | Exercise training ET (n=106) vs guideline control CON (n=52) |

| Results | Significant correlation between ratio scaled VO2peak and BM (r=-0.25, p=0.02), stature (r=0.46, p<0.001) and body surface area (r=0.23, p=0.03), and not with fat free mass (r≤0.11; R 2=1%) No significant correlation between allometrically expressed VO2peak and any scaling denominator were not (r≤0.11; R 2=1%) |

Significant increase in VO2 max with HIIT (from 26.0 ±5.3 to 31.3±5.8 mL/min/kg, P<0.0001) and LVEDV (p<0.0001) No significant change in VO2 max (from 24.6±3.4 to 24.1±4.1 mL/min/kg, P=0.986) or LVEDV (p=0.175) in controls Unchanged resting blood pressure in both groups. LV myocardial stiffness was reduced with HIIT (LV chamber stiffness: from 0.060±0.031 to 0.042±0.025; LV myocardial stiffness: from 0.062±0.020 to 0.031±0.009) No significant change in controls (LV chamber stiffness: from 0.041±0.016 to 0.049±0.020; LV myocardial stiffness: from 0.061±0.033 to 0.066±0.031) |

Significant increase in VO2peak in both groups (HIIT 22.7%, MCT 11.3%; p<0.001) Peak oxygen pulse, estimate of stroke volume, increased more favourably in HIIT group First ventilatory threshold (anaerobic threshold) increased similarly in both groups (12.1 ± 0.6 to 13.4 ± 0.7 and 11.5 ± 0.8 to 12.6 ± 0.8 mL·kg−1·min−1, for MCT and HIIT, respectively, p < 0.001 for time comparison) No difference in peak RER between groups |

Relative peak VO2 increased by 8.0 ± 15.7% in the ET group compared with a reduction of −2.0 ± 18.3% in the CON group. The difference in change between groups was primarily mediated by changes in peak O2-pulse (~72%) Mean changes were significantly different between ET and CON for relative peak VO2, absolute peak VO2, peak O2-pulse and weight (P < 0.05) No significant differences have been observed for the change in peak HR, haemoglobin or peak respiratory exchange ratio (RER) |

| Response to Endurance Exercise Training in Older Adults with Heart Failure with Preserved or Reduced Ejection Fraction (51) | Efficacy and Safety of Exercise Training in Patients With Chronic Heart FailureHF-ACTION Randomized Controlled Trial (55) | Short-term effects of a 3-week interval training program on Heart Rate Variability in chronic heart failure. A randomised controlled trialShort-term effects of a 3-week interval training program on Heart Rate Variability in chronic heart failure. A randomised controlled trial (56) | High-Intensity Interval Training in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (57) | Combined aerobic/resistance/inspiratory muscle training as the ‘optimum’ exercise programme for patients with chronic heart failure: Aristos-HF randomized clinical trial (58) | |

| Study type | Secondary analysis of an RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT |

| Method arms | Individuals with HF (24 HFrEF, 24 HFpEF) who underwent supervised exercise training. | Usual care plus aerobic exercise training (n=1159) vs usual care alone (1172) | MICT ( n = 15) vs HIIT ( n = 16) | HIIT, (n=77), MCT (n=65), vs recommendation of regular exercise (RRE) (n=73). | ARIS (19) vs AT/IMT (n=20) vs AT/RT (n=17) vs AT (n=18) |

| Results | Both groups combined, endurance training had 9.2% increase in VO2peak (ml/kg/min) with substantial individual-level variability in the change in response to training. Improvement in VO2peak in response to training was considerably higher in HFpEF vs. HFrEF patients (18.7±17.6 vs. −0.3±15.4%; p<0.001). Similar pattern was observed with absolute VO2peak (ml/min) Training-related increases in other measures of exercise capacity, including exercise time and ventilatory anaerobic threshold, were also greater in HFpEF vs. HFrEF patients, with trends towards statistical significance. No significant difference in change in 6MWT between the two groups |

759 (65%) patients in the exercise group died or were hospitalised, compared with 796 (68%) in the usual care group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.93; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.84–1.02; P = .13) Nonsignificant reductions in the exercise training group for mortality (189 [16%] in the exercise group vs 198 [17%] in the usual care group; HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.79–1.17; P = .70), cardiovascular mortality or cardiovascular hospitalisation (632 [55%] in the exercise group vs 677 [58%] in the usual care group; HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83–1.03; P = .14), and cardiovascular mortality or heart failure hospitalisation (344 [30%] in the exercise group vs 393 [34%] in the usual care group; HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.75–1.00; P = .06) Other adverse events were similar between the groups. |

High-frequency power in normalised units (HFnu%) measured as HRV increased with HIIT (from 21.2% to 26.4%, P < 0.001) but remained unchanged with MICT (from 23.1% to 21.9%, P = 0.444, with a significant intergroup difference, P = 0.003) Resting heart rate decreased significantly for both groups (from 68.2 to 64.6 bpm and 66.0 to 63.5 bpm for MICT and HIIT, respectively, with no intergroup difference, P = 0.578) No difference in premature ventricular contractions Improvement in peak oxygen uptake was greater with HIIT than MICT (+ 21% vs. + 5%, P = 0.009) LVEF improved with only HIIT (from 36.2% to 39.5%, P = 0.034). |

Change in LVED diameter from baseline to 12 weeks was not different between HIIT and MCT (P=0.45); LVED diameter changes compared with RRE were −2.8 mm (−5.2 to −0.4 mm; P=0.02) in HIIT and −1.2 mm (−3.6 to 1.2 mm; P=0.34) in MCT No difference between HIIT and MCT in peak oxygen uptake (P=0.70), but both were superior to RRE. However, none of these changes was maintained at follow-up after 52 weeks. Serious adverse events were not statistically different during supervised intervention or at follow-up at 52 weeks (HIIT, 39%; MCT, 25%; RRE, 34%; P=0.16). |

Between-group analysis showed a trend for increased peakVO2(mL/kg/min) [mean contrasts (95% CI)] in the ARIS group [ARIS vs. AT/RT 1.71 (0.163–3.25), vs. AT/IMT 1.50 (0.0152–2.99), vs. AT 1.38 (−0.142 to 2.9)] Increased LVES diameter (mm) [ARIS vs. AT/RT −2.11 (−3.65 to (−0.561)), vs. AT −2.47 (−4.01 to (−0.929))] 6MWT (m) [ARIS vs. AT/IMT 45.6 (18.3–72.9)**, vs. AT 55.2 (27.6–82.7)] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).