Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

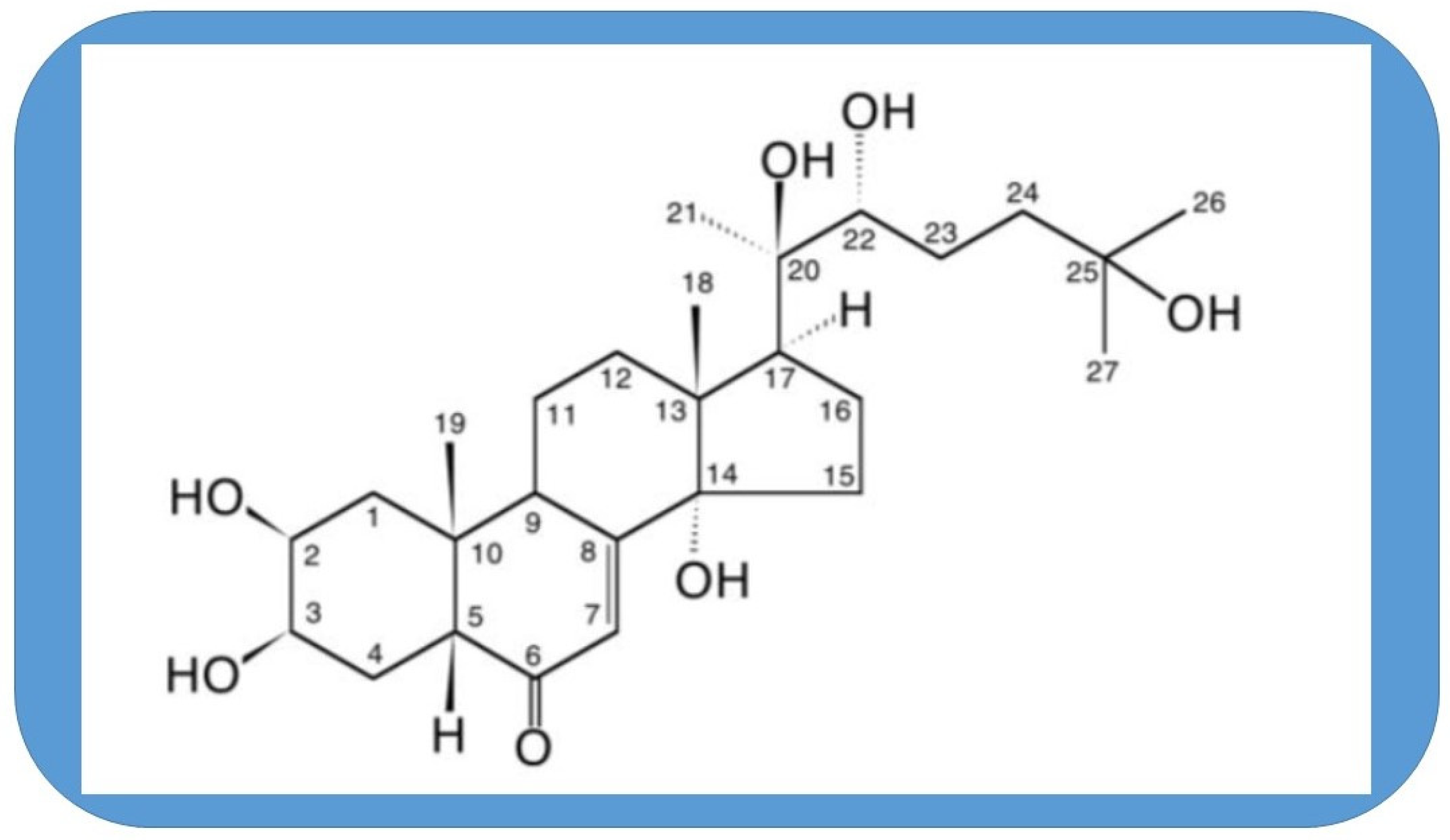

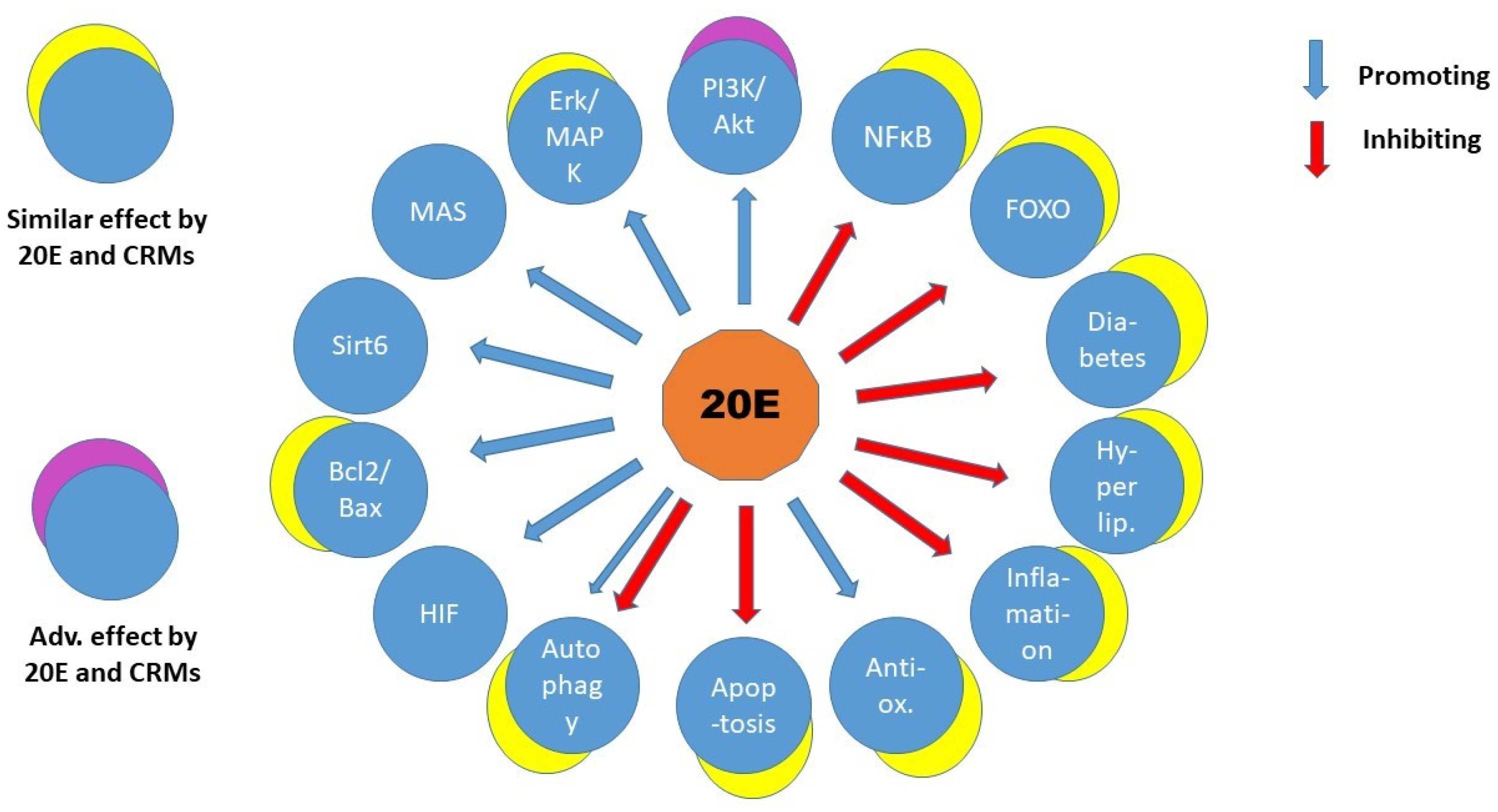

The 20-hydroryecdysone (20E) has been used in traditional medicine for a long time and acquired attention in the last decade as a food supplement and stimulant in phys-ical activities. This polyhydroxylated cholesterol is found in the highest concentration in plants and it is one of the secondary plant products that has a real hormonal influ-ence in arthropods. Various beneficial effects have been reported in vivo and in vitro for 20E and its related compounds in mammals. Trials for safety of clinical application showed a remarkable high tolerance in human. This review aims to assess the latest development in the involvement of various pathways in tissues and organs and look if it is plausible to find a single primary target of this compound. The similarities with agens mimicking calorie restriction and anti-aging effects are also elucidated and discussed.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cell, Tissue and Systematic Action

2.1. Effects on Skeletal Muscle

2.2. Effect on Skin, Bone and Cartilage

2.3. Influence on Nerve System

2.4. Actions on Inflammation and Apoptosis

2.5. Impact on Liver and Adipose Tissue

2.6. Calorie Restriction Mimetics and 20E

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dinan, L.; Dioh, W.; Veillet, S.; Lafont, R. 20-Hydroxyecdysone, from Plant Extracts to Clinical Use: Therapeutic Potential for the Treatment of Neuromuscular, Cardio-Metabolic and Respiratory Diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dioh, W.; Tourette, C.; Del Signore, S.; Daudigny, L.; Dupont, P.; Balducci, C. et al. Dilda PJ, Lafont R, Veillet S. A Phase 1 study for safety and pharmacokinetics of BIO101 (20-hydroxyecdysone) in healthy young and older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1259-1273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, S.M.; Plantefève, G.; Nair, G.; Joaquim Cavalcante, A.; Franzin de Moraes, N. et al. Efficacy of oral 20-hydroxyecdysone (BIO101), a MAS receptor activator, in adults with severe COVID-19 (COVA): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 68, 102383. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Báthori, M.; Tóth, N.; Hunyadi, A.; Márki, A.; Zádor, E. Phytoecdysteroids and anabolic-androgenic steroids--structure and effects on humans. Current medicinal chemistry 2008, 15, 75–91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, N.; Hunyadi, A.; Báthori, M.; Zádor, E. Phytoecdysteroids and vitamin D analogues--similarities in structure and mode of action. Current medicinal chemistry, 2010, 17, 1974–1994. [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Schiefner, F.; Rudolf, M.; Awiszus, F.; Junne, F.; Vogel, M.; Lohmann, C.H. Long-term effects of doping with anabolic steroids during adolescence on physical and mental health. Orthopadie 2024, 53, 608-616. [CrossRef]

- Lafont, R.; Balducci, C.; Dinan, L. Ecdysteroids. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 1267-1302. [CrossRef]

- Arif, Y.; Singh, P.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Phytoecdysteroids: Distribution, Structural Diversity, Biosynthesis, Activity, and Crosstalk with Phytohormones. In J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 8664. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinan, L.; Dioh, W.; Veillet, S.; Lafont, R. 20-Hydroxyecdysone, from Plant Extracts to Clinical Use: Therapeutic Potential for the Treatment of Neuromuscular, Cardio-Metabolic and Respiratory Diseases. Biomedicines, 2021, 9, 492. [CrossRef]

- Gorelick-Feldman, J.; Cohick, W.; Raskin, I. Ecdysteroids elicit a rapid Ca2+ flux leading to Akt activation and increased protein synthesis in skeletal muscle cells. Steroids 2010, 75, 632-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.F. G protein-coupled receptors function as cell membrane receptors for the steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone. Cell Commun Signal 2020, 18, 146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parr, M.K.; Zhao, P.; Haupt, O.; Ngueu, S.T.; Hengevoss. J. Fritzemeier, K.H. et al. Estrogen receptor beta is involved in skeletal muscle hypertrophy induced by the phytoecdysteroid ecdysterone. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014, 58, 1861-72. [CrossRef]

- Lafont, R.; Serova, M.; Didry-Barca, B.; Raynal, S.; Guibout, L.; Dinan, L. et al. 20-Hydroxyecdysone activates the protective arm of the RAAS via the MAS receptor. J Mol Endocrinol. 2021, 68, 77-87. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, B.; Ren, L.; Yang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Yao, F. et al. 20-Hydroxyecdysone inhibits inflammation via SIRT6-mediated NF-κB signaling in endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2023, 1870, 119460. [CrossRef]

- Gorelick-Feldman, J.; Maclean, D.; Ilic, N.; Poulev, A, Lila, M.A.; Cheng, D.; Raskin, I. Phytoecdysteroids increase protein synthesis in skeletal muscle cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3532-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirunsai, M.; Yimlamai, T.; Suksamrarn, A. Effect of 20-Hydroxyecdysone on Proteolytic Regulation in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. In Vivo 2016, 30, 869-877. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, T.G.; Mirek, E.T.; Bargoud, A.R.; Phillipson-Weiner, L.; DeOliveira, C.M.; Wetstein, B. et al. Evaluating the effect of 20-hydroxyecdysone (20HE) on mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling in the skeletal muscle and liver of rats. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2015, 40, 1324-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, N.; Szabó, A.; Kacsala, P.; Héger, J.; Zádor, E. 20-Hydroxyecdysone increases fibre size in a muscle-specific fashion in rat. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 691-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csábi, J.; Rafai, T.; Hunyadi, A.; Zádor, E. Poststerone increases muscle fibre size partly similar to its metabolically parent compound, 20-hydroxyecdysone. Fitoterapia, 2019, 134, 459–464. [CrossRef]

- Isenmann, E.; Ambrosio, G.; Joseph, J.F.; Mazzarino, M.; de la Torre, X.; Zimmer, P. et al. Ecdysteroids as non-conventional anabolic agent: performance enhancement by ecdysterone supplementation in humans. Arch Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1807-1816. [CrossRef]

- The WADA 2020 Monitoring Program. [(accessed on 3 May 2023)]. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/wada_2020_english_monitorin.

- Zwetsloot, K.A.; Shanely, R.A.; Godwin, J.S.; Hodgman, C.F. Phytoecdysteroids Accelerate Recovery of Skeletal Muscle Function Following in vivo Eccentric Contraction-Induced Injury in Adult and Old Mice. Front Rehabil Sci. 2021, 2, 757789. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.M.; Zwetsloot, K.A.; Arthur, S.T.; Sherman, C.A.; Huot, J.R.; Badmaev, V.; et al. Phytoecdysteroids Do Not Have Anabolic Effects in Skeletal Muscle in Sedentary Aging Mice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 370. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.M.; Kutzler, L.W.; Boler, D.D.; Drnevich, J.; Killefer, J.; Lila, M.A. et al. Continuous infusion of 20-hydroxyecdysone increased mass of triceps brachii in C57BL/6 mice. Phytother Res. 2013, 27, 107-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serova, M.; Didry-Barca. B.; Deloux, R.; Foucault, A. S.; Veillet, S.; Lafont, R. et al. BIO101 stimulates myoblast differentiation and improves muscle function in adult and old mice. J Cachexia, Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 55–66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, V.; Ivanova, S.; Chakarov, D.; Kraev, K.; Ivanov, K. Ecdysterone and Turkesterone-Compounds with Prominent Potential in Sport and Healthy Nutrition. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 1382. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afsar, B.; Afsar, R.E.; Caliskan, Y.; Lentine, K.L.; Edwards, J.C. Renin angiotensin system-induced muscle wasting: putative mechanisms and implications for clinicians. Mol Cell Biochem. 2024, May 29. doi: 10.1007/s11010-024-05043-8. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Cai, G.; Shi, X. Beta-ecdysterone induces osteogenic differentiation in mouse mesenchymal stem cells and relieves osteoporosis. Biol pharm bull. 2008, 31, 2245–2249. [CrossRef]

- Seidlova-Wuttke, D.; Christel, D.; Kapur, P.; Nguyen, B.T.; Jarry, H.; Wuttke, W. Beta-ecdysone has bone protective but no estrogenic effects in ovariectomized rats. Phytomedicine 2010, 17,884-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, P.; Wuttke, W.; Jarry, H.; Seidlova-Wuttke, D. Beneficial effects of beta-Ecdysone on the joint, epiphyseal cartilage tissue and trabecular bone in ovariectomized rats. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 350-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrhardt, C.; Wessels, J.T.; Wuttke, W. .; Seidlová-Wuttke, D. The effects of 20-hydroxyecdysone and 17β-estradiol on the skin of ovariectomized rats. Menopause 2011, 18, 323-7. [CrossRef]

- Jian, C.X.; Liu, X.F.; Hu, J.; Li, C.J.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y. et al. 20-Hydroxyecdysone-induced bone morphogenetic protein-2-dependent osteogenic differentiation through the ERK pathway in human periodontal ligament stem cells. Eur J Pharmacol 2013, 698, 48-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Jiang, L.; Lay, Y.A.; Chen, H.; Jin, G.; Zhang, H. et al. Prevention of glucocorticoid induced bone changes with beta-ecdysone. Bone 2015, 74, 48-57. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, Z.A.; Jiang, L.; Chen, H.; Lay, Y.A. et al. β-Ecdysone Augments Peak Bone Mass in Mice of Both Sexes. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015, 473, 2495-504. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.W.; Wang, L.B.; Jin, G.Q.; Wu, H.J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.L. et al. Beta-Ecdysone Protects Mouse Osteoblasts from Glucocorticoid-Induced Apoptosis In Vitro. Planta Med 2017, 83, 888-894. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.H.; Yue, Z.S.; Xin, D.W.; Zeng, L.R.; Xiong, Z.F.; Hu, Z.Q.; Xu, C.D. β-Ecdysterone promotes autophagy and inhibits apoptosis in osteoporotic rats. Mol Med Rep. 2018, 17, 1591-1598. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, S. Y.; Ho, SR.; Sun, J.S.; Chen, C.Y.; Ke, C.J. Arthropod steroid hormone (20-Hydroxyecdysone) suppresses IL-1β-induced catabolic gene expression in cartilage. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015, 15, 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, W.L.; Xu, Z.L. β-ecdysone promotes osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J Gene Med 2020, 22, e3207. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Guan, J.; Zhu, X. β-Ecdysone attenuates cartilage damage in a mouse model of collagenase-induced osteoarthritis via mediating FOXO1/ADAMTS-4/5 signaling axis. Histol Histopathol 2021, 36, 785-794.

- Yan, C.P.; Wang, X.K.; Jiang, K.; Yin, C.; Xiang, C.; Wang, Y. et al. β-Ecdysterone Enhanced Bone Regeneration Through the BMP-2/SMAD/RUNX2/Osterix Signaling Pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 883228. [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.H.; Yoon, W.J.; Seo, S.B.; Woo, K.M.; Kim, G.S.; Ryoo, H.M.; Baek, J.H. BMP2-activated Erk/MAP kinase stabilizes Runx2 by increasing p300 levels and histone acetyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 36410-9. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.H.; Xi, G.; Feng, H. The effect of ecdysterone on cerebral vasospasm following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in vitro and in vivo. Neurol Res 2008, 30, 571-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, T.Z.; Chu, W.H.; Luo, C.X.; Tang, W.H.; Yi, L.; Feng H. Protective effects of 20-hydroxyecdysone on CoCl(2)-induced cell injury in PC12 cells. J Cell Biochem 2010, 111, 1512-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Yi, B.; Fan, W.; Chen, K.; Gui, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, L. et al. Enhanced angiogenesis and astrocyte activation by ecdysterone treatment in a focal cerebral ischemia rat model. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2011, 110, 151-5. [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Luo, C.X.; Chu, W.H.; Shan, Y.A.; Qian, Z.M.; Zhu, G. et al. 20-Hydroxyecdysone protects against oxidative stress-induced neuronal injury by scavenging free radicals and modulating NF-κB and JNK pathways. PLoS One 2012, 7, e50764. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Tang, N.; Liu, F. et al. Effects of 20-hydroxyecdysone on improving memory deficits in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus in rat. Eur J Pharmacol 2014, 740, 45-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trillo, L.; Das, D.; Hsieh, W.; Medina, B.; Moghadam, S.; Lin, B. et al. Ascending monoaminergic systems alterations in Alzheimer's disease. translating basic science into clinical care. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013, 37, 1363-79. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H. S.; Moon, B. C.; Lee, J.; Choi, G .; Park, G. The insect molting hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone protects dopaminergic neurons against MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2020, 159, 23–36.

- Zou ,Y.; Wang, R.; Guo, H.; Dong, M. Phytoestrogen β-Ecdysterone Protects PC12 Cells Against MPP+-Induced Neurotoxicity In Vitro: Involvement of PI3K-Nrf2-Regulated Pathway. Toxicol Sci 2015, 147, 28-38. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gao, L.; Shang, L.; Wang, G.; Wei, N.; Chu, T. et al. Ecdysterones from Rhaponticum carthamoides (Willd.) Iljin reduce hippocampal excitotoxic cell loss and upregulate mTOR signaling in rats. Fitoterapia 2017, 119, 158-167. [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.R.; de Almeida Takata, L.; Chagas, K.; Justino, A.B.; Saraiva, A.L.; Goulart, L.R. et al. A 20-hydroxyecdysone-enriched fraction from Pfaffia glomerata (Spreng.) pedersen roots alleviates stress, anxiety, and depression in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 267, 113599.

- Gholipour, P.; Komaki, A.; Ramezani, M.; Parsa, H. Effects of the combination of high-intensity interval training and Ecdysterone on learning and memory abilities, antioxidant enzyme activities, and neuronal population in an Amyloid-beta-induced rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Physiol Behav 2022, 251, 113817. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, V.; Ivanova, S.; Yotov, V.; Zaytseva, E.; Ardasheva, R.; Turiyski, V.; Prissadova, N.; Ivanov, K. Phytoecdysteroids: Quantification in Selected Plant Species and Evaluation of Some Effects on Gastric Smooth Muscles. Molecules 2024, 29, 5145. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, T.; Qin, S. β-Ecdysterone suppresses interleukin-1β-induced apoptosis and inflammation in rat chondrocytes via inhibition of NF-κB signaling pathway. Drug Dev Res 2014, 75, 195-201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posey, K.L. Curcumin and Resveratrol: Nutraceuticals with so Much Potential for Pseudoachondroplasia and Other ER-Stress Conditions. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 154. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, K.; El-Mekawey, D.; Elmasry, A.E.; Refaey, M.S.; El-Sayed Ghoneim, M.; Elshaier, Y.A.M.M. The significance of caloric restriction mimetics as anti-aging drugs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2024, 692, 149354. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Niu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, M. β-Ecdysterone Protects SH-SY5Y Cells Against 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Apoptosis via Mitochondria-Dependent Mechanism: Involvement of p38(MAPK)-p53 Signaling Pathway. Neurotox Res 2016, 30, 453-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, D.L.; Liu, Z.X.; Sun, X.H.; Li, Y. Beneficial effect of 20-hydroxyecdysone exerted by modulating antioxidants and inflammatory cytokine levels in collagen-induced arthritis: A model for rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Med Rep 2017, 16, 6162-6169. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Hui, A.; Jian, P. Ecdysterone Accelerates Healing of Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Rats by Increasing Matrix Cell Proliferation. Radiat Res 2019, 191, 237-244.

- Yang, L.; Pan, J. Therapeutic Effect of Ecdysterone Combine Paeonol Oral Cavity Direct Administered on Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 3800. [CrossRef]

- Romaniuk-Drapała, A.; Lisiak, N.; Totoń, E.; Matysiak, A.; Nawrot, J.; Nowak G. et al. Proapoptotic and proautophagic activity of 20-hydroxyecdysone in breast cancer cells in vitro. Chem Biol Interact 2021, 342, 109479. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Friedemann, T.; Pan, J. Ecdysterone Attenuates the Development of Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Rats at Early Stage. Radiat Res 2021, 196, 366-374. [CrossRef]

- Kizelsztein, P.; Govorko, D.; Komarnytsky, S.; Evans, A.; Wang, Z.; Cefalu, W.T.; Raskin, I. 20-Hydroxyecdysone decreases weight and hyperglycemia in a diet-induced obesity mice model. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2009, 296, E433-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, R.; Naresh, R.; Shanthi, P.; Sachdanandam, P. Efficacy of 20-OH-ecdysone on hepatic key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 725-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naresh Kumar, R.; Sundaram, R.; Shanthi, P.; Sachdanandam, P. Protective role of 20-OH ecdysone on lipid profile and tissue fatty acid changes in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2013, 698, 489-98. [CrossRef]

- Semiane, N.; Foufelle, F.; Ferré, P.; Hainault, I.; Ameddah, S.; Mallek, A. et al.. High carbohydrate diet induces nonalcoholic steato-hepatitis (NASH) in a desert gerbil. C R Biol 2017, 340, 25-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallek, A.; Movassat, J.; Ameddah, S.; Liu, J.; Semiane, N.; Khalkhal, A.; Dahmani, Y. Experimental diabetes induced by streptozotocin in the desert gerbil, Gerbillus gerbillus, and the effects of short-term 20-hydroxyecdysone administration. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 102, 354-361. [CrossRef]

- Agoun, H.; Semiane, N.; Mallek, A.; Bellahreche, Z.; Hammadi, S.; Madjerab, M. et al. High-carbohydrate diet-induced metabolic disorders in Gerbillus tarabuli (a new model of non-alcoholic fatty-liver disease). Protective effects of 20-hydroxyecdysone. Arch Physiol Biochem 2021,127, 127-135. [CrossRef]

- Bellahreche, Z.; Dahmani, Y. 20-Hydroxyecdysone bioavailability and pharmacokinetics in Gerbillus tarabuli, a gerbil model for metabolic syndrome studies. Steroids 2023, 198, 109262. [CrossRef]

- Foucault, A.S.; Mathé, V.; Lafont, R.; Even, P.; Dioh, W.; Veillet, S. et al. Quinoa extract enriched in 20-hydroxyecdysone protects mice from diet-induced obesity and modulates adipokines expression. Obesity 2012, 20, 270-7. [CrossRef]

- Graf, B.L.; Poulev, A.; Kuhn, P.; Grace, M.H.; Lila, M.A.; Raskin, I. Quinoa seeds leach phytoecdysteroids and other compounds with anti-diabetic properties. Food Chem 2014, 163, 178-85. [CrossRef]

- Foucault, A.S.; Even, P.; Lafont, R.; Dioh, W.; Veillet, S.; Tomé, D. et al. Quinoa extract enriched in 20-hydroxyecdysone affects energy homeostasis and intestinal fat absorption in mice fed a high-fat diet. Physiol Behav 2014, 128, 226-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merenda, T.; Juszczak, F.; Ferier, E.; Duez, P.; Patris, S.; Declèves, A. É.; Nachtergael, A. Natural compounds proposed for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Natural products and bioprospecting 2024, 14, 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.J.; Jin, H.; Zheng, S.L.; Xia, P.; Cai, Y.; Ni, X.J. Phytoecdysteroids from Ajuga iva act as potential antidiabetic agent against alloxan-induced diabetic male albino rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 96, 480-488. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.J.; Madrigal-Matute, J, .; Scheibye-Knudsen M, Fang E, Aon M, González-Reyes JA, et al.. Effects of sex, strain, and energy intake on hallmarks of aging in mice. Cell Metab 2016, 23, 1093–112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Min, K.J. Caloric restriction and its mimetics. BMB Rep. 2013, 46, 181-7. [CrossRef]

- Mattison, J.A.; Colman, R.J.; Beasley, T.M.; Allison, D.B.; Kemnitz, J.W.; Roth GS. et al. Caloric restriction improves health and survival of rhesus monkeys. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14063. [CrossRef]

- Most, J.; Tosti, V.; Redman, L.M.; Fontana, L. Calorie restriction in humans: An update. Ageing Res Rev 2017, 39, 36-45. [CrossRef]

- Ravussin, E.; Redman, L. M.; Rochon, J.; Das, S. K.; Fontana, L.; Kraus, W. E.; … CALERIE Study Group. A 2-year randomized controlled trial of human caloric restriction: Feasibility and effects on predictors of health span and longevity. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2015, 70, 1097–1104. [CrossRef]

- Das, S. K.; Balasubramanian, P.; Weerasekara, Y. K. Nutrition modulation of human aging: The calorie restriction paradigm. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2017, 455, 148–157. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Silver, R.E.; Senior, A.; Gilhooly, C.H.; Bhapkar, M.; Le Couteur, D. Diet composition, adherence to calorie restriction, and cardiometabolic disease risk modification. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e14018. [CrossRef]

- Waziry, R.; Ryan, C.P.; Corcoran, D.L.; Huffman, K.M.; Kobor, M.S.; Kothari, M.; et al. Effect of long-term caloric restriction on DNA methylation measures of biological aging in healthy adults from the CALERIE trial. Nat Aging 2023, 3, 248-257. Erratum in: Nat Aging. 2023, 3, 753. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, W.J.; Ye, Q.; Wolf, S.E.; Ryan, C.P.; Das, S.K.; Huffman, K.M.; Kobor MS, et al. Effect of long-term caloric restriction on telomere length in healthy adults: CALERIE™ 2 trial analysis. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14149. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, R. Cut Calories, Lengthen Life Span? Randomized Trial Uncovers Evidence That Calorie Restriction Might Slow Aging, but Questions Remain. JAMA 2023, 329, 1049-1050. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekmekcioglu, C. Nutrition and longevity - From mechanisms to uncertainties. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020, 60, 3063-3082. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, S.J.; Davinelli, S.; Bergmann, M.; Scapagnini, G.; Madeo, F. Caloric Restriction Mimetics in Nutrition and Clinical Trials. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 717343. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, I.; Hollenberg, M.D.; Ding, H.; Triggle, C.R. A Critical Review of the Evidence That Metformin Is a Putative Anti-Aging Drug That Enhances Healthspan and Extends Lifespan. Front Endocrinol 2021, 12, 718942. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buniam, J.; Chansela, P.; Weerachayaphorn, J.; Saengsirisuwan, V. Dietary Supplementation with 20-Hydroxyecdysone Ameliorates Hepatic Steatosis and Reduces White Adipose Tissue Mass in Ovariectomized Rats Fed a High-Fat, High-Fructose Diet. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2071. [CrossRef]

- Guru, B.; Tamrakar, A. K.; Manjula, S. N.; Prashantha Kumar, B. R. Novel dual PPARα/γ agonists protect against liver steatosis and improve insulin sensitivity while avoiding side effects. European journal of pharmacology 2022, 935, 175322. [CrossRef]

- Shuvalov, O.; Kirdeeva, Y.; Fefilova, E.; Daks, A.; Fedorova, O.; Parfenyev, S.; Nazarov, A.; Vlasova, Y.; Krasnov, G.S.; Barlev, N.A. 20-Hydroxyecdysone Boosts Energy Production and Biosynthetic Processes in Non-Transformed Mouse Cells. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1349. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das S.; Morvan, F.; Jourde, B.; Meier, V.; Kahle, P.; Brebbia, P. et al. ATP citrate lyase improves mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle. Cell metabolism, 2015, 21, 868–876. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Morvan, F.; Morozzi, G.; Jourde, B.; Minetti, G. C.; Kahle, P. et al. ATP Citrate Lyase Regulates Myofibre Differentiation and Increases Regeneration by Altering Histone Acetylation. Cell reports, 2017, 21, 3003–3011. [CrossRef]

- Espino-Gonzalez, E.; Tickle, P.G.; Altara R.; Gallagher, H.; Cheng, C. W.; Engman, V. et al. Caloric restriction rejuvenates skeletal muscle growth in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science 2024, 9, 223–240. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zádor E. Paradoxical Effect of Caloric Restriction on Overload-Induced Muscle Growth in Diastolic Heart Failure., J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science 2024, 9, 241–243. [CrossRef]

- Tarkowská, D.; Strnad, M. Plant ecdysteroids: plant sterols with intriguing distributions, biological effects and relations to plant hormones. Planta, 2016, 244, 545–555. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, E.; Titova, M.; Tynykulov, M.; Zakirova, R. P.; Kulichenko, I.; Prudnikova, O.; Nosov, A. Sustainable Production of Ajuga Bioactive Metabolites Using Cell Culture Technologies: A Review. Nutrients, 2023, 15, 1246. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuvalov, O.; Kirdeeva, Y.; Fefilova, E.; Netsvetay, S.; Zorin, M.; Vlasova, Y. et al. 20-Hydroxyecdysone Confers Antioxidant and Antineoplastic Properties in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Metabolites, 2023, 13, 656. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, K. W.; Fung, T. S.; Baker, D. C.; Saoi, M .;Park, J.; Febres-Aldana, C. A.; et al. Cellular ATP demand creates metabolically distinct subpopulations of mitochondria. Nature 2024,. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.J.; Kahn, C.R. Endocrine regulation of ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007, 8, 681–91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, Y.; Atzmon, G.; Cho, M.O.; Hwang, D .; Liu, B.; Leahy, D.J. et al. Functionally significant insulin-like growth factor I receptor mutations in centenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2008, 105, 3438–3442. [CrossRef]

- Giacomozzi, C.; Martin, A.; Fernández, M.C.; Gutiérrez, M.; Iascone, M.; Domené, H.M. et al. Novel Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Gene Mutation: Broadening of the Phenotype and Implications for Insulin Resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023, 108, 1355–1369. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).