Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

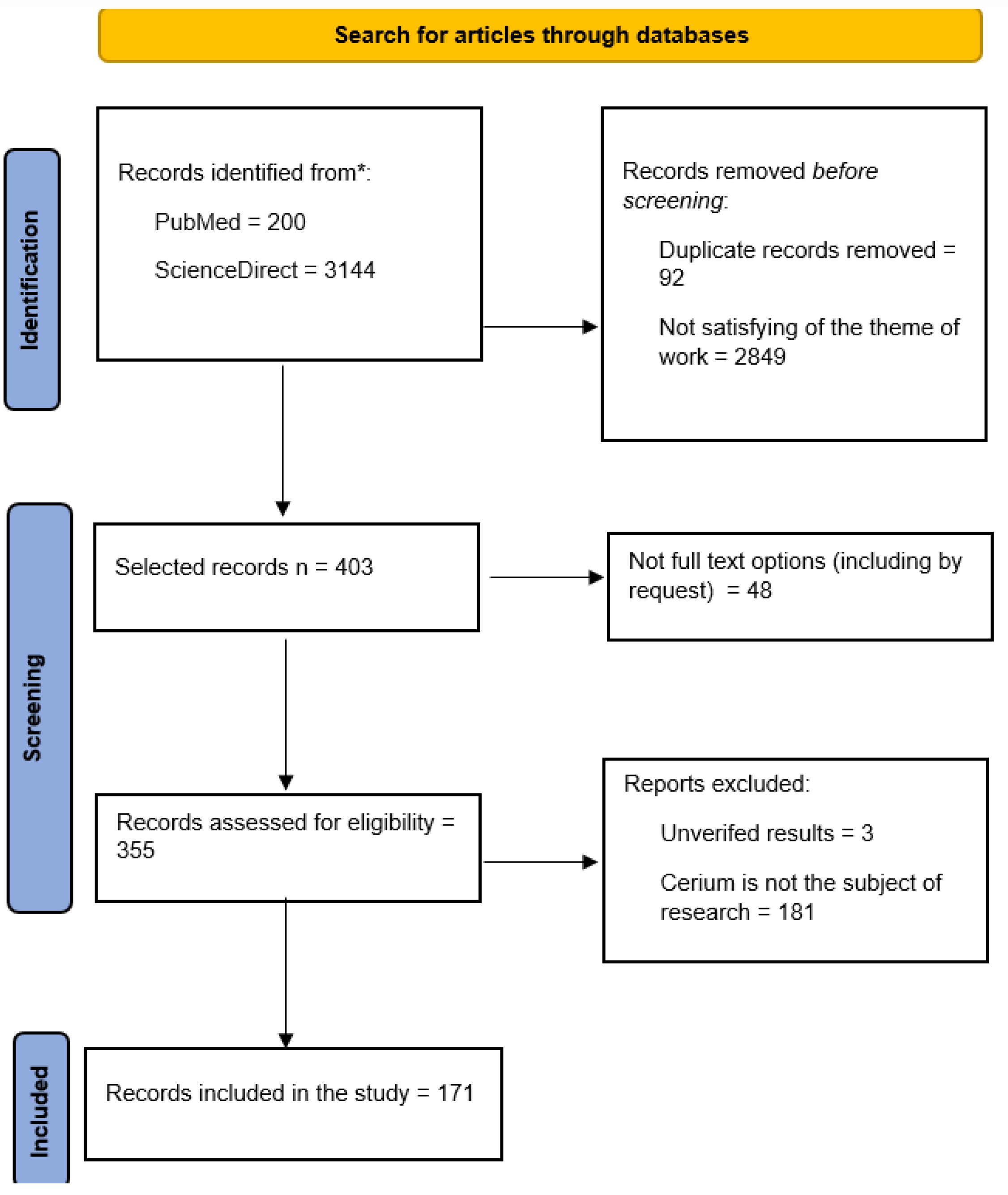

3.1. Results of the Literature Search and the Final Flowchart of the PRISMA Search Strategy

3.2. Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles and Biopolymers

3.3. Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles and Carboxylic Acid Derivatives

3.4. Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles and Liposomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manturova, N.E.; Stupin, V.A.; Silina, E.V. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles for Surgery, Plastic Surgery and Aesthetic Medicine. Plast. khir. 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, S.; Thangaraj, P.; Sengodan, P.; Radhakrishnan, J. Biomimetic Facile Synthesis of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles for Enhanced Degradation of Textile Wastewater and Phytotoxicity Evaluation. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2022, 146, 110037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pešić, M.; Podolski-Renić, A.; Stojković, S.; Matović, B.; Zmejkoski, D.; Kojić, V.; Bogdanović, G.; Pavićević, A.; Mojović, M.; Savić, A.; et al. Anti-Cancer Effects of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles and Its Intracellular Redox Activity. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2015, 232, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Liao, H.; Wang, M.; Feng, L.; Fu, W.; Hu, L. Highly Sensitive Chemiluminescent Sensing of Intracellular Al3+ Based on the Phosphatase Mimetic Activity of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2020, 152, 112027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S Jairam, L.; Chandrashekar, A.; Prabhu, T.N.; Kotha, S.B.; Girish, M.S.; Devraj, I.M.; Dhanya Shri, M.; Prashantha, K. A Review on Biomedical and Dental Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles ― Unearthing the Potential of This Rare Earth Metal. Journal of Rare Earths 2023, 41, 1645–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzini, I.; Marino, A.; Del Turco, S.; Nesti, C.; Doccini, S.; Cappello, V.; Gemmi, M.; Parlanti, P.; Santorelli, F.M.; Mattoli, V.; et al. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: The Regenerative Redox Machine in Bioenergetic Imbalance. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2017, 12, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad; Khan, U.A.; Warsi, M.H.; Alkreathy, H.M.; Karim, S.; Jain, G.K.; Ali, A. Intranasal Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Improves Locomotor Activity and Reduces Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Haloperidol-Induced Parkinsonism in Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1188470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Neal, C.J.; Sakthivel, T.S.; Seal, S.; Kean, T.; Razavi, M.; Coathup, M. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Protect against Irradiation-Induced Cellular Damage While Augmenting Osteogenesis. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 126, 112145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Manturova, N.E.; Erokhina, A.G.; Shatokhina, E.A.; Stupin, V.A. Nanomaterials Based on Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles for Wound Regeneration: A Literature Review. RJTAO 2023, 26, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Wali, R.; Mashwani, Z.-R.; Raja, N.I.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A.; Zaman, S. ; Sohail Nanowarriors from Mentha: Unleashing Nature’s Antimicrobial Arsenal with Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 15449–15462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Bhardwaj, K. Mechanistic Understanding of Green Synthesized Cerium Nanoparticles for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes and Antibiotics from Aqueous Media and Antimicrobial Efficacy: A Review. Environmental Research 2024, 246, 118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, H.-A.; Al-Ansari, M.M.; Al-Dahmash, N.D.; Krishnan, R.; Shanmuganathan, R. In Vitro Analyses of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles in Degrading Anthracene/Fluorene and Revealing the Antibiofilm Activity against Bacteria and Fungi. Chemosphere 2023, 345, 140487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Gutiérrez, R.M.; Rodríguez-Serrano, L.M.; Laguna-Chimal, J.F.; De La Luz Corea, M.; Paredes Carrera, S.P.; Téllez Gomez, J. Geniposide and Harpagoside Functionalized Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles as a Potential Neuroprotective. IJMS 2024, 25, 4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibañez, I.L.; Notcovich, C.; Catalano, P.N.; Bellino, M.G.; Durán, H. The Redox-Active Nanomaterial Toolbox for Cancer Therapy. Cancer Letters 2015, 359, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, F.; Gregori, M.; Masserini, M. Nanotechnology for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Maturitas 2012, 73, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, Y.; Calonge, M. Applications of Nanoparticles in Ophthalmology. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2010, 29, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Stupin, V.A.; Manturova, N.E.; Ivanova, O.S.; Popov, A.L.; Mysina, E.A.; Artyushkova, E.B.; Kryukov, A.A.; Dodonova, S.A.; Kruglova, M.P.; et al. Influence of the Synthesis Scheme of Nanocrystalline Cerium Oxide and Its Concentration on the Biological Activity of Cells Providing Wound Regeneration. IJMS 2023, 24, 14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silina, E.; Stupin, V.; Manturova, N.; Vasin, V.; Koreyba, K.; Litvitskiy, P.; Saltykov, A.; Balkizov, Z. Acute Skin Wounds Treated with Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Biopolymer Compositions Alone and in Combination: Evaluation of Agent Efficacy and Analysis of Healing Mechanisms. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalasz, H.; Antal, I. Drug Excipients. CMC 2006, 13, 2535–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakama, K.A.; Dos Santos, R.B.; Serpa, P.; Maciel, T.R.; Haas, S.E. Organoleptic Excipients Used in Pediatric Antibiotics. Archives de Pédiatrie 2019, 26, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, R.; Bosch, B.; Brune, K.; Patrignani, P.; Young, C. Advances in NSAID Development: Evolution of Diclofenac Products Using Pharmaceutical Technology. Drugs 2015, 75, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markl, D.; Zeitler, J.A. A Review of Disintegration Mechanisms and Measurement Techniques. Pharm Res 2017, 34, 890–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kean, E.A.; Adeleke, O.A. Orally Disintegrating Drug Carriers for Paediatric Pharmacotherapy. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 182, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labetoulle, M.; Benitez-del-Castillo, J.M.; Barabino, S.; Herrero Vanrell, R.; Daull, P.; Garrigue, J.-S.; Rolando, M. Artificial Tears: Biological Role of Their Ingredients in the Management of Dry Eye Disease. IJMS 2022, 23, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajjadi, M.; Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Ghafuri, H. Functionalized Chitosan-Inspired (Nano)Materials Containing Sulfonic Acid Groups: Synthesis and Application. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 343, 122443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonjan, R.; Singh, D. Functional Excipients and Novel Drug Delivery Scenario inSelf-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System: A Critical Note. PNT 2022, 10, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; Waggoner, C.; Boylan, P.M. Commentary: Is Polyethylene Glycol Toxicity From Intravenous Methocarbamol Fact or Fiction? Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy 2024, 38, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfil, C.; Chauchat, L.; Guerin, C.; Rebika, H.; Sahyoun, M.; Schrage, N. Impact of Latanoprost Antiglaucoma Eyedrops and Their Excipients on Toxicity and Healing Characteristics in the Ex Vivo Eye Irritation Test System. Ophthalmol Ther 2023, 12, 2641–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palugan, L.; Filippin, I.; Cirilli, M.; Moutaharrik, S.; Zema, L.; Cerea, M.; Maroni, A.; Foppoli, A.; Gazzaniga, A. Cellulase as an “Active” Excipient in Prolonged-Release HPMC Matrices: A Novel Strategy towards Zero-Order Release Kinetics. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2021, 607, 121005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjar, A.; Wadsworth, I.; Vargis, E.; Britt, D.W. Poloxamer 188 – Quercetin Formulations Amplify in Vitro Ganciclovir Antiviral Activity against Cytomegalovirus. Antiviral Research 2022, 204, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Manturova, N.E.; Ivanova, O.S.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Artyushkova, E.B.; Medvedeva, O.A.; Kryukov, A.A.; Dodonova, S.A.; Gladchenko, M.P.; Vorsina, E.S.; et al. Cerium Dioxide–Dextran Nanocomposites in the Development of a Medical Product for Wound Healing: Physical, Chemical and Biomedical Characteristics. Molecules 2024, 29, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Chamoli, S.; Kumar, P.; Maurya, P.K. Structural and Functional Insights in Polysaccharides Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Potential Biomedical Applications: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 246, 125673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Xu, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, P. Novel Design of Multifunctional Nanozymes Based on Tumor Microenvironment for Diagnosis and Therapy. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 238, 114456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, E.; Jreije, I.; Tetreault, V.; Hauser, C.; Zerges, W.; Wilkinson, K.J. Biological Impacts of Ce Nanoparticles with Different Surface Coatings as Revealed by RNA-Seq in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. NanoImpact 2020, 19, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, A.B. CeO2 Nanoparticles and Cerium Species as Antiviral Agents: Critical Review. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports 2024, 10, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-W.; Cha, B.G.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, W.; Ki, S.K.; Han, J.H.; Cho, H.Y.; Park, E.; Jeon, S.; Lee, S.-H. Ultrasmall Polymer-Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles as a Traumatic Brain Injury Therapy. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 2022, 45, 102586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parimi, D.; Sundararajan, V.; Sadak, O.; Gunasekaran, S.; Mohideen, S.S.; Sundaramurthy, A. Synthesis of Positively and Negatively Charged CeO 2 Nanoparticles: Investigation of the Role of Surface Charge on Growth and Development of Drosophila Melanogaster. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Y.; Ramalingam, M.; Lv, X.; Zeng, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Si, Y.; Pedraz, J.L.; Kim, H.-W.; Hu, J. Recent Advances in Nanomedicine Development for Traumatic Brain Injury. Tissue and Cell 2023, 82, 102087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, H.; Heydari, M.; Khodaei, M. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis Methods and Applications in Wound Healing. Materials Today Bio 2023, 23, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Soo Lee, S.; Savini, M.; Popp, L.; Colvin, V.L.; Segatori, L. Ceria Nanoparticles Stabilized by Organic Surface Coatings Activate the Lysosome-Autophagy System and Enhance Autophagic Clearance. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 10328–10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.D.; Stabler, C.L. Antioxidant Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle Hydrogels for Cellular Encapsulation. Acta Biomaterialia 2015, 16, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, C.; Nica, I.; Dinischiotu, A.; Iconaru, S.; Chapon, P.; Bita, B.; Trusca, R.; Groza, A.; Predoi, D. Novel Dextran Coated Cerium Doped Hydroxyapatite Thin Films. Polymers 2022, 14, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesneau, C.; Pawlak, A.; Hamadi, S.; Leroy, E.; Belbekhouche, S. Cerium Oxide Particles: Coating with Charged Polysaccharides for Limiting the Aggregation State in Biological Media and Potential Application for Antibiotic Delivery. RSC Pharm. 2024, 1, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrabi, S.M.; Singh, P.; Majumder, S.; Kumar, A. A Compositionally Synergistic Approach for the Development of a Multifunctional Bilayer Scaffold with Antibacterial Property for Infected and Chronic Wounds. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 423, 130219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpaslan, E.; Geilich, B.M.; Yazici, H.; Webster, T.J. pH-Controlled Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle Inhibition of Both Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria Growth. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 45859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T. ; Wang; Perez Inhibited Growth of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa by Dextran- and Polyacrylic Acid-Coated Ceria Nanoparticles. IJN 2013, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, Z.; Li, S.; Jiang, J.; Li, M.; Fu, B. Remineralization of Dentin with Cerium Oxide and Its Potential Use for Root Canal Disinfection. IJN 2023, Volume 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, M.; Hosseini, F.; Adli, A.H.; Salmanzadeh, S.; Behboudi, E.; Halvaei, P.; Khosravi, A.; Abbasi, S. State-of-the-Art Cerium Nanoparticles as Promising Agents against Human Viral Infections. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 156, 113868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Chung, B.H. Antioxidant Activity of Levan Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Carbohydrate Polymers 2016, 150, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.S.; Li, T.; Akinade, T.; Zhu, Y.; Leong, K.W. Drug Delivery Carriers with Therapeutic Functions. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2021, 176, 113884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpaslan, E.; Yazici, H.; Golshan, N.H.; Ziemer, K.S.; Webster, T.J. pH-Dependent Activity of Dextran-Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles on Prohibiting Osteosarcoma Cell Proliferation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, L.; Marcos, R.; Hernández, A. Nanoceria Acts as Antioxidant in Tumoral and Transformed Cells. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2018, 291, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashnikova, I.; Mazar, J.; Neal, C.J.; Rosado, A.L.; Das, S.; Westmoreland, T.J.; Seal, S. Nanoparticle Delivery of Curcumin Induces Cellular Hypoxia and ROS-Mediated Apoptosis via Modulation of Bcl-2/Bax in Human Neuroblastoma. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 10375–10387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miletić, M.; Aškrabić, S.; Rüger, J.; Vasić, B.; Korićanac, L.; Mondol, A.S.; Dellith, J.; Popp, J.; Schie, I.W.; Dohčević-Mitrović, Z. Combined Raman and AFM Detection of Changes in HeLa Cervical Cancer Cells Induced by CeO 2 Nanoparticles – Molecular and Morphological Perspectives. Analyst 2020, 145, 3983–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, W.; Liu, B.; Xu, G.; Liu, L.; Lv, H.; Shang, D.; Yang, D.; Damirin, A.; Zhang, J. Cytotoxicity of Ultrafine Monodispersed Nanoceria on Human Gastric Cancer Cells. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2014, 10, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkam, S.; Das, S.; Saraf, S.; McCormack, R.; Richardson, D.; Atencio, L.; Moosavifazel, V.; Seal, S. The Change in Antioxidant Properties of Dextran-Coated Redox Active Nanoparticles Due to Synergetic Photoreduction–Oxidation. Chemistry A European J 2015, 21, 12646–12656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Chen, D.; Tu, J.; Sun, C.; Du, Y. Hyaluronic Acid-Guided Assembly of Ceria Nanozymes as Plaque-Targeting ROS Scavengers for Anti-Atherosclerotic Therapy. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 296, 119940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zou, J.; Chen, B.; Cao, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wen, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, K. Hyaluronic Acid/Serotonin-Decorated Cerium Dioxide Nanomedicine for Targeted Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, M.S.; Farrugia, B.L.; Yan, C.M.Y.; Vassie, J.A.; Whitelock, J.M. Hyaluronan Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Modulate CD44 and Reactive Oxygen Species Expression in Human Fibroblasts. J Biomedical Materials Res 2016, 104, 1736–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, J.; Shen, Y.; Song, Y.; Yang, K.; Pei, P.; Hu, L. Biomaterials-Mediated Radiation-Induced Diseases Treatment and Radiation Protection. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 370, 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Sahu, A.; Jeon, S.H.; Tae, G. Emerging Drug Delivery Systems with Traditional Routes – A Roadmap to Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2023, 203, 115119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-W.; Fang, C.-H.; Meng, F.-Q.; Ke, C.-J.; Lin, F.-H. Hyaluronic Acid Loaded with Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles as Antioxidant in Hydrogen Peroxide Induced Chondrocytes Injury: An In Vitro Osteoarthritis Model. Molecules 2020, 25, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Jin, M.; Yang, H. Remodelers of the Vascular Microenvironment: The Effect of Biopolymeric Hydrogels on Vascular Diseases. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 264, 130764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifi, M.A.; Seal, S.; Godugu, C. Nanoceria, the Versatile Nanoparticles: Promising Biomedical Applications. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 338, 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Feng, Q.; Han, Y.; Chen, M.; Guo, M.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Li, G. Therapeutic Effect on Experimental Acute Cerebral Infarction Is Enhanced after Nanoceria Labeling of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2019, 12, 175628641985972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Cai, D.; Mo, L.; Jing, G.; Zeng, L.; Cheng, H.; Guo, Q.; Dai, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Multifunctional Nanogel Loaded with Cerium Oxide Nanozyme and CX3CL1 Protein: Targeted Immunomodulation and Retinal Protection in Uveitis Rat Model. Biomaterials 2024, 309, 122617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, H.-L.; Wen, C.; Xu, P.; Shen, X.-C.; Gao, C. NIR-II-Responsive CeO 2– x @HA Nanotheranostics for Photoacoustic Imaging-Guided Sonodynamic-Enhanced Synergistic Phototherapy. Langmuir 2022, 38, 5502–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu Varukattu, N.; Lin, W.; Vivek, R.; Rejeeth, C.; Sabarathinam, S.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, H. Targeted and Intrinsic Activity of HA-Functionalized PEI-Nanoceria as a Nano Reactor in Potential Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Treatment. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Rahimizadeh, K.; Shafiee, A.; Rabiee, N.; Iravani, S. Nanozymes and Their Emerging Applications in Biomedicine. Process Biochemistry 2023, 131, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Cheng, H.; Dai, Y.; Su, Z.; Wang, C.; Lei, L.; Lin, D.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Fan, K.; et al. In Vivo Regenerable Cerium Oxide Nanozyme-Loaded pH/H 2 O 2 -Responsive Nanovesicle for Tumor-Targeted Photothermal and Photodynamic Therapies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.R.; Kim, G.G.; Park, S.B.; Kim, S.W. Synthesis of Hyaluronic Acid-Conjugated Fe3O4@CeO2 Composite Nanoparticles for a Target-Oriented Multifunctional Drug Delivery System. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wu, Z.; Pan, B.; Zhang, R.; Golestani, A.; Feng, Z.; Ge, Y.; Yang, H. Functional Biomacromolecules-Based Microneedle Patch for the Treatment of Diabetic Wound. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 267, 131650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, V.A.; Dubashynskaya, N.V.; Gofman, I.V.; Golovkin, A.S.; Mishanin, A.I.; Aquino, A.D.; Mukhametdinova, D.V.; Nikolaeva, A.L.; Ivan’kova, E.M.; Baranchikov, A.E.; et al. Biocomposite Films Based on Chitosan and Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles with Promising Regenerative Potential. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 229, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanzadeh, L.; Kazemi Oskuee, R.; Sadri, K.; Nourmohammadi, E.; Mohajeri, M.; Mardani, Z.; Hashemzadeh, A.; Darroudi, M. Green Synthesis of Labeled CeO2 Nanoparticles with 99mTc and Its Biodistribution Evaluation in Mice. Life Sciences 2018, 212, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H.M.; Abd El-Daim, T.M.; Mohamed, H.A.A.E.N.E.; Mahmoud, E.A.A.E.Q.; Abdallah, E.A.S.; Mahmoud Hassan, F.E.; Maihop, D.I.; Amin, A.E.A.E.; Mustafa, A.B.E.; Hassan, F.M.A.; et al. Multifunctional Nanoparticles in Stem Cell Therapy for Cellular Treating of Kidney and Liver Diseases. Tissue and Cell 2020, 65, 101371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Wang, W.-D.; Li, S.-R.; Sun, Z.-J.; Zhang, L. Harnessing Cerium-Based Biomaterials for the Treatment of Bone Diseases. Acta Biomaterialia 2024, 183, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.N.; Gao, R.; Zheng, M.; Wu, M.-J.; Voinov, M.A.; Smirnov, A.I.; Smirnova, T.I.; Wang, K.; Chavala, S.; Han, Z. Glycol Chitosan Engineered Autoregenerative Antioxidant Significantly Attenuates Pathological Damages in Models of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4669–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Wu, K.; Guo, J. Development of Tannin-Bridged Cerium Oxide Microcubes-Chitosan Cryogel as a Multifunctional Wound Dressing. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2022, 214, 112479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, R.P.; Bhuvaneshwari, V.; Ranjithkumar, R.; Sathiyavimal, S.; Malayaman, V.; Chandarshekar, B. Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Hybrid Chitosan-Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: As a Bionanomaterials. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 104, 1746–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, H.; Heydari, M.; Tootiaei, Z.; Ganjbar, S.; Khodaei, M. Delivery of Antibacterial Agents for Wound Healing Applications Using Polysaccharide-Based Scaffolds. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 84, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Gan, J.; Fakhri, A.; Dizaji, B.F.; Azarbaijan, M.H.; Hosseini, M. Preparation of Ceric Oxide and Cobalt Sulfide-Ceric Oxide/Cellulose-Chitosan Nanocomposites as a Novel Catalyst for Efficient Photocatalysis and Antimicrobial Study. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 143, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, P.; Gupta, M.S.; Jayakumar, R.; Gowda, D.V. Prospection of Chitosan and Its Derivatives in Wound Healing: Proof of Patent Analysis (2010–2020). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 184, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalipooya, S.; Fahimirad, S.; Abtahi, H.; Golmohammadi, M.; Satari, M.; Dadashpour, M.; Nasrabadi, D. Diabetic Wound Healing Function of PCL/Cellulose Acetate Nanofiber Engineered with Chitosan/Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 653, 123880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Singh, S.; Maiti, T.K.; Das, A.; Barui, A.; Chaudhari, L.R.; Joshi, M.G.; Dutt, D. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Disseminated Chitosan Gelatin Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 236, 123813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, R.; Narayan, A.; Bramhecha, I.; Sheikh, J. Development of Multifunctional Linen Fabric Using Chitosan Film as a Template for Immobilization of In-Situ Generated CeO2 Nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 121, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildizbakan, L.; Iqbal, N.; Ganguly, P.; Kumi-Barimah, E.; Do, T.; Jones, E.; Giannoudis, P.V.; Jha, A. Fabrication and Characterisation of the Cytotoxic and Antibacterial Properties of Chitosan-Cerium Oxide Porous Scaffolds. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, V.A.; Gofman, I.V.; Dubashynskaya, N.V.; Golovkin, A.S.; Mishanin, A.I.; Ivan’kova, E.M.; Romanov, D.P.; Khripunov, A.K.; Vlasova, E.N.; Migunova, A.V.; et al. Chitosan Composites with Bacterial Cellulose Nanofibers Doped with Nanosized Cerium Oxide: Characterization and Cytocompatibility Evaluation. IJMS 2023, 24, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.-H.; Yu, C.-H.; Yeh, Y.-C. Engineering Nanocomposite Hydrogels Using Dynamic Bonds. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 130, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Liang, W.; Song, S.; Xue, H.; Fan, T.; Liu, S. Engineering of Cerium Oxide Loaded Chitosan/Polycaprolactone Hydrogels for Wound Healing Management in Model of Cardiovascular Surgery. Process Biochemistry 2021, 106, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, R.; Wang, P.; Fu, J.; Tang, Z.; Xie, J.; Ning, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhong, Q.; Pan, X.; et al. Electrospun Polyvinyl Alcohol-Chitosan Dressing Stimulates Infected Diabetic Wound Healing with Combined Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging and Antibacterial Abilities. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 316, 121050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubair, M.; Hussain, A.; Shahzad, S.; Arshad, M.; Ullah, A. Emerging Trends and Challenges in Polysaccharide Derived Materials for Wound Care Applications: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 270, 132048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.; Mahmoudi, E.; Fauzi, M.B. Applications of Drug Delivery Systems, Organic, and Inorganic Nanomaterials in Wound Healing. Discover Nano 2023, 18, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lu, Y.; Zhan, R.; Qian, W.; Luo, G. Nanomaterials and Nanomaterials-Based Drug Delivery to Promote Cutaneous Wound Healing. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2023, 193, 114670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Zhang, T.; Che, M.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Liu, L.; Lv, Z.; Xiao, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S. Recent Advances in Nanomaterials for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury. Materials Today Bio 2023, 18, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.; Song, H.; Lan Chi, N.T.; Brindhadevi, K. Numerous Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery System to Control Secondary Immune Response and Promote Spinal Cord Injury Regeneration. Process Biochemistry 2022, 112, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Tyeb, S.; Verma, V. Recent Advances on Metal Oxide-Polymer Systems in Targeted Therapy and Diagnosis: Applications and Toxicological Perspective. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2021, 66, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Song, H. Synthesis of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Loaded on Chitosan for Enhanced Auto-Catalytic Regenerative Ability and Biocompatibility for the Spinal Cord Injury Repair. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2019, 191, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen Inbaraj, B.; Chen, B.-H. An Overview on Recent in Vivo Biological Application of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 15, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Malviya, R.; Uniyal, P. Advancements in the Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment of Retinoblastoma. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 2024, 59, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Priyanka Bandi, S.; Colaco, V.; Dhas, N.; Siva Reddy, D.; Vora, L.K. Fostering the Unleashing Potential of Nanocarriers-Mediated Delivery of Ocular Therapeutics. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 658, 124192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, A.B.; Reukov, V.V.; Yakimansky, A.V.; Krasnopeeva, E.L.; Ivanova, O.S.; Popov, A.L.; Ivanov, V.K. CeO2 Nanoparticle-Containing Polymers for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossein Karami, M.; Abdouss, M. Cutting-Edge Tumor Nanotherapy: Advancements in 5-Fluorouracil Drug-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2024, 164, 112430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, B.; Xu, W. Intellective and Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems in Eyes. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2021, 602, 120591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Xu, J.; Heidari, G.; Jiang, H.; Shi, Y.; Wu, A.; Makvandi, P.; Neisiany, R.E.; Zare, E.N.; Shao, M.; et al. Injectable Hydrogels Based on Biopolymers for the Treatment of Ocular Diseases. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 269, 132086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrobaian, M. Pegylated Nanoceria: A Versatile Nanomaterial for Noninvasive Treatment of Retinal Diseases. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2023, 31, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhti, A.; Shokouhi, Z.; Mohammadipanah, F. Modulation of Proteins by Rare Earth Elements as a Biotechnological Tool. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 258, 129072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.S.; Shoari, A.; Salehibakhsh, N.; Aliabadi, H.A.M.; Abolhosseini, M.; Arab, S.S.; Ahmadieh, H.; Kanavi, M.R.; Behdani, M. Anti-Angiogenic Biomolecules in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration; Therapeutics and Drug Delivery Systems. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 659, 124258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Mitra, R.N.; Zheng, M.; Han, Z. Nanoceria-loaded Injectable Hydrogels for Potential Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatment. J Biomedical Materials Res 2018, 106, 2795–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbehdari, S.; Handa, J.T. Oxidative Stress as a Therapeutic Target for the Prevention and Treatment of Early Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Survey of Ophthalmology 2021, 66, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, D.K.; Pradhan, D.; Biswasroy, P.; Kar, B.; Ghosh, G.; Rath, G. Recent Trends in Nanocarrier Based Approach in the Management of Dry Eye Disease. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2021, 66, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Lin, S.; Wu, F.; Liu, J. Nanomaterial-Based Ophthalmic Drug Delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2023, 200, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, R.; Prasher, P.; Sharma, M.; Chellappan, D.K.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Patravale, V.B.; Dua, K. Aminated Polysaccharides: Unveiling a New Frontier for Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 89, 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Hong, J. Nanomedicines for the Treatment of Glaucoma: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 125, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.-J.; Rethi, L.; Ku, M.-Y.; Nguyen, H.T.; Chuang, A.E.-Y. A Review on Revolutionizing Ophthalmic Therapy: Unveiling the Potential of Chitosan, Hyaluronic Acid, Cellulose, Cyclodextrin, and Poloxamer in Eye Disease Treatments. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 273, 132700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, A.Y.; Han, Z. A Cerium Oxide Loaded Glycol Chitosan Nano-System for the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 315, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onugwu, A.L.; Nwagwu, C.S.; Onugwu, O.S.; Echezona, A.C.; Agbo, C.P.; Ihim, S.A.; Emeh, P.; Nnamani, P.O.; Attama, A.A.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Nanotechnology Based Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Anterior Segment Eye Diseases. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 354, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buosi, F.S.; Alaimo, A.; Di Santo, M.C.; Elías, F.; García Liñares, G.; Acebedo, S.L.; Castañeda Cataña, M.A.; Spagnuolo, C.C.; Lizarraga, L.; Martínez, K.D.; et al. Resveratrol Encapsulation in High Molecular Weight Chitosan-Based Nanogels for Applications in Ocular Treatments: Impact on Human ARPE-19 Culture Cells. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 165, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, M.; Rafique, M.; Cui, Y.; Pan, L.; Do, C.-W.; Ho, E.A. An Insight on Ophthalmic Drug Delivery Systems: Focus on Polymeric Biomaterials-Based Carriers. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 362, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Han, F.; Duan, X.; Zheng, D.; Cui, Q.; Liao, W. Advances of Biological Macromolecules Hemostatic Materials: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 269, 131772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farasatkia, A.; Maeso, L.; Gharibi, H.; Dolatshahi-Pirouz, A.; Stojanovic, G.M.; Edmundo Antezana, P.; Jeong, J.-H.; Federico Desimone, M.; Orive, G.; Kharaziha, M. Design of Nanosystems for Melanoma Treatment. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 665, 124701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Dyawanapelly, S. Nanodiagnostics and Nanotherapeutics for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 329, 1262–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, T.; Fan, X.; Chrzanowski, W.; Gillies, M.C.; Zhu, L. Recent Advances and Prospects for Lipid-Based Nanoparticles as Drug Carriers in the Treatment of Human Retinal Diseases. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2023, 199, 114965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thasu Dinakaran, V.; Santhaseelan, H.; Krishnan, M.; Devendiran, V.; Dahms, H.U.; Duraikannu, S.L.; Rathinam, A.J. Gracilaria Salicornia as Potential Substratum for Green Synthesis of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Coupled Hydrogel: An Effective Antimicrobial Thin Film. Microbial Pathogenesis 2023, 184, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-P.J.; Byun, M.J.; Kim, S.-N.; Park, W.; Park, H.H.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, J.S.; Park, C.G. Biomaterials as Therapeutic Drug Carriers for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treatment. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 345, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, H.; Razzaq, A.; Zhou, D.; Lou, J.; Xiao, R.; Lin, F.; Liang, Y. Nanomedicine in Glaucoma Treatment; Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Materials Today Bio 2024, 28, 101229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Song, L.; Li, M.; Peng, H.; Qiu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, B.; Liu, C.; Ren, S.; Miao, L. Injectable CNPs/DMP1-Loaded Self-Assembly Hydrogel Regulating Inflammation of Dental Pulp Stem Cells for Dentin Regeneration. Materials Today Bio 2024, 24, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yan, H.; Wang, S.; Xiao, J. Controlled Release of Ceria and Ferric Oxide Nanoparticles via Collagen Hydrogel for Enhanced Osteoarthritis Therapy. Adv Healthcare Materials 2024, 2401507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-F.; Malacco, C.M.D.S.; Mehmood, R.; Johnson, K.K.; Yang, J.-L.; Sorrell, C.C.; Koshy, P. Impact of Morphology and Collagen-Functionalization on the Redox Equilibria of Nanoceria for Cancer Therapies. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 120, 111663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubairi, W.; Tehseen, S.; Nasir, M.; Anwar Chaudhry, A.; Ur Rehman, I.; Yar, M. A Study of the Comparative Effect of Cerium Oxide and Cerium Peroxide on Stimulation of Angiogenesis: Design and Synthesis of Pro-angiogenic Chitosan/Collagen Hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res 2022, 110, 2751–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, M.B.; Sadeghnia, H.R.; Pasdar, A.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Riahi-Zanjani, B.; Darroudi, M. Role of Pullulan in Preparation of Ceria Nanoparticles and Investigation of Their Biological Activities. Journal of Molecular Structure 2018, 1157, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbasekar, C.; Fathima, N.N. Collagen Stabilization Using Ionic Liquid Functionalised Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 147, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Xu, L. Recent Advancements in Hydrogels as Novel Tissue Engineering Scaffolds for Dental Pulp Regeneration. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 264, 130708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purohit, S.D.; Singh, H.; Bhaskar, R.; Yadav, I.; Chou, C.-F.; Gupta, M.K.; Mishra, N.C. Gelatin—Alginate—Cerium Oxide Nanocomposite Scaffold for Bone Regeneration. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2020, 116, 111111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Li, J.; Song, X.; Sun, T.; Mi, L.; Liu, J.; Xia, X.; Bai, N.; Li, X. Alginate/Gelatin Hydrogel Scaffold Containing nCeO2 as a Potential Osteogenic Nanomaterial for Bone Tissue Engineering. IJN 2022, Volume 17, 6561–6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; Pan, L.; Xiao, J. Greasing Wheels of Cell-Free Therapies for Cardiovascular Diseases: Integrated Devices of Exosomes/Exosome-like Nanovectors with Bioinspired Materials. Extracellular Vesicle 2022, 1, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Behera, M.; Mahapatra, C.; Sundaresan, N.R.; Chatterjee, K. Nanostructured Polymer Scaffold Decorated with Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles toward Engineering an Antioxidant and Anti-Hypertrophic Cardiac Patch. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 118, 111416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivari-Ghader, T.; Rashidi, M.-R.; Mehrali, M. Biological Macromolecule-Based Hydrogels with Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities for Wound Dressing: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 279, 134578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, N.; Pahwa, R.; Thakur, V.K.; Gupta, M. Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogels: New Insights and Futuristic Prospects in Wound Healing. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 223, 1586–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Shi, Z.; Yue, K.; Huang, X.; Xu, Y.; Gao, C.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, Y.S.; Wang, J. Sprayable Hydrogel Dressing Accelerates Wound Healing with Combined Reactive Oxygen Species-Scavenging and Antibacterial Abilities. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 124, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, I.S.; Fathima, N.N. Gelatin–Cerium Oxide Nanocomposite for Enhanced Excisional Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xu, Y.; Sang, X.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ramakrishna, S.; Wang, C.; Hu, P.; Nanda, H.S. PLLA–Gelatin Composite Fiber Membranes Incorporated with Functionalized CeNPs as a Sustainable Wound Dressing Substitute Promoting Skin Regeneration and Scar Remodeling. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, R.; Zahid, A.A.; Hasan, A.; Dalvi, Y.B.; Jacob, J. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle-Loaded Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogel Wound-Healing Patch with Free Radical Scavenging Activity. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, F.; Raza, Z.A.; Batool, S.R.; Zahid, M.; Onder, O.C.; Rafique, A.; Nazeer, M.A. Preparation, Properties, and Applications of Gelatin-Based Hydrogels (GHs) in the Environmental, Technological, and Biomedical Sectors. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 218, 601–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Gui, R. Platelet-Membrane Camouflaged Cerium Nanoparticle-Embedded Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogel for Accelerated Diabetic Wound Healing. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 251, 126393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.U.; Patel, R.J.; Gaur, M.; Parikh, S.; Prajapati, B.G. Metallic and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Treating Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infections. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 91, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, K.; Allah-Bakhshi, N.; Akhavan, F.; Yousefi, M.; Golmoradi, R.; Ramezani, M.; Bach, H.; Razavi, S.; Irajian, G.-R.; Gerami, M.; et al. Antibacterial Effect of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. BMC Biotechnol 2021, 21, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Yadav, I.; Sheikh, W.M.; Dan, A.; Darban, Z.; Shah, S.A.; Mishra, N.C.; Shahabuddin, S.; Hassan, S.; Bashir, S.M.; et al. Dual Cross-Linked Gellan Gum/Gelatin-Based Multifunctional Nanocomposite Hydrogel Scaffold for Full-Thickness Wound Healing. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 251, 126349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramasinghe, A.S.D.; Kalansuriya, P.; Attanayake, A.P. Nanoformulation of Plant-Based Natural Products for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: From Formulation Design to Therapeutic Applications. Current Therapeutic Research 2022, 96, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, N.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; Del Bakhshayesh, A.R.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Davaran, S.; Annabi, N. Multifunctional Hydrogels for Wound Healing: Special Focus on Biomacromolecular Based Hydrogels. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 170, 728–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, N.; Ahmed, S.; Ali, M.A. Chitooligosaccharides and Their Structural-Functional Effect on Hydrogels: A Review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 261, 117882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Tonda-Turo, C.; De Pasquale, D.; Ruini, F.; Genchi, G.; Nitti, S.; Cappello, V.; Gemmi, M.; Mattoli, V.; Ciardelli, G.; et al. Gelatin/Nanoceria Nanocomposite Fibers as Antioxidant Scaffolds for Neuronal Regeneration. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2017, 1861, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.; Bhattacharyya, C.; Sahu, R.; Dua, T.K.; Kandimalla, R.; Dewanjee, S. Polymeric Nanotherapeutics: An Emerging Therapeutic Approach for the Management of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 91, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, B.; Behroozi, Z.; Motamednezhad, A.; Jafarpour, M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Moshiri, A.; Janzadeh, A.; Ramezani, F. Study of Nerve Cell Regeneration on Nanofibers Containing Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles in a Spinal Cord Injury Model in Rats. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2023, 34, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Zhao, T.; Ding, Q.; Ding, C.; Liu, W. Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogel Promotes Skin Wound Repair and Research Progress on Its Repair Mechanism. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 248, 125949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatimoghaddam, S.; Iman, M.; Shahdadi Sardo, H.; Jebali, A. Gelatin Hydrogel Containing Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Covered by Interleukin-17 Aptamar as an Anti- Inflammatory Agent for Brain Inflammation. Journal of Neuroimmunology 2019, 326, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarone, R.; Tisi, A.; Passacantando, M.; Ciancaglini, M. Ophthalmic Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2020, 36, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang Ping Wu; Munakata, M. ; Kuroda-Sowa, T.; Maekawa, M.; Suenaga, Y. Synthesis, Crystal Structures and Magnetic Behavior of Polymeric Lanthanide Complexes with Benzenehexacarboxylic Acid (Mellitic Acid). Inorganica Chimica Acta 1996, 249, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omsk State Medical University; Solonenko, A. P.; Blesman, A.I.; Omsk State Medical University; Polonyankin, D.A.; Omsk State Technical University SYNTHESIS AND PHYSICOCHEMICAL INVESTIGATION OF CALCIUM SILICATE HYDRATE WITH DIFFERENT STOICHIOMETRIC COMPOSITION. DSMM 2018, 6, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atla, S.B.; Wu, M.-N.; Pan, W.; Hsiao, Y.T.; Sun, A.-C.; Tseng, M.-J.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, C.-Y. Characterization of CeO 2 Crystals Synthesized with Different Amino Acids. Materials Characterization 2014, 98, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadam, R.; Easwaran, M.; Rethinam, S.; Madasamy, S.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Kandhaswamy, A.; Venkidasamy, B. Boosting Plant Resilience: The Promise of Rare Earth Nanomaterials in Growth, Physiology, and Stress Mitigation. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 208, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, D.; Dargusch, R.; Raitano, J.; Chan, S.-W. Cerium and Yttrium Oxide Nanoparticles Are Neuroprotective. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2006, 342, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G.; Guo, W.; Han, L.; Chen, E.; Kong, L.; Wang, L.; Ai, W.; Song, N.; Li, H.; Chen, H. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Induce Cytotoxicity in Human Hepatoma SMMC-7721 Cells via Oxidative Stress and the Activation of MAPK Signaling Pathways. Toxicology in Vitro 2013, 27, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; He, J.; Zhang, H.; Chi, H.; Shi, Y.; Xu, X. Recent Advances in the Development of Tumor Microenvironment-Activatable Nanomotors for Deep Tumor Penetration. Materials Today Bio 2024, 27, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasouli, Z.; Yousefi, M.; Torbati, M.B.; Samadi, S.; Kalateh, K. Synthesis and Characterization of Nanoceria-Based Composites and in Vitro Evaluation of Their Cytotoxicity against Colon Cancer. Polyhedron 2020, 176, 114297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, M.L.; Grulke, E.A.; Yokel, R.A. Carboxylic Acids and Light Interact to Affect Nanoceria Stability and Dissolution in Acidic Aqueous Environments. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2023, 14, 762–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Oswalia, J.; Yadav, S.; Vachher, M.; Nigam, A. Recent Trends in Nanozyme Research and Their Potential Therapeutic Applications. Current Research in Biotechnology 2024, 7, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokel, R.A.; Au, T.C.; MacPhail, R.; Hardas, S.S.; Butterfield, D.A.; Sultana, R.; Goodman, M.; Tseng, M.T.; Dan, M.; Haghnazar, H.; et al. Distribution, Elimination, and Biopersistence to 90 Days of a Systemically Introduced 30 Nm Ceria-Engineered Nanomaterial in Rats. Toxicological Sciences 2012, 127, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, L.P.; Manshian, B.B.; De Souza, T.A.J.; Soenen, S.J.; Matsubara, E.Y.; Rosolen, J.M.; Takahashi, C.S. Cyto- and Genotoxic Effects of Metallic Nanoparticles in Untransformed Human Fibroblast. Toxicology in Vitro 2015, 29, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, V.; Ferreira De Oliveira, J.M.P.; Brown, D.; Jonhston, H.; Malheiro, E.; Daniel-da-Silva, A.L.; Duarte, I.F.; Santos, C.; Oliveira, H. The Influence of Citrate or PEG Coating on Silver Nanoparticle Toxicity to a Human Keratinocyte Cell Line. Toxicology Letters 2016, 249, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golyshkin, D.; Kobyliak, N.; Virchenko, O.; Falalyeyeva, T.; Beregova, T.; Ostapchenko, L.; Caprnda, M.; Skladany, L.; Opatrilova, R.; Rodrigo, L.; et al. Nanocrystalline Cerium Dioxide Efficacy for Prophylaxis of Erosive and Ulcerative Lesions in the Gastric Mucosa of Rats Induced by Stress. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2016, 84, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobyliak, N.; Virchenko, O.; Falalyeyeva, T.; Kondro, M.; Beregova, T.; Bodnar, P.; Shcherbakov, O.; Bubnov, R.; Caprnda, M.; Delev, D.; et al. Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles Possess Anti-Inflammatory Properties in the Conditions of the Obesity-Associated NAFLD in Rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 90, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, D.A.; Oostveen, E.K.; Triplett, J.; Butterfield, D.A.; Tsyusko, O.V.; Collin, B.; Starnes, D.L.; Cai, J.; Klein, J.B.; Nass, R.; et al. The Role of Charge in the Toxicity of Polymer-Coated Cerium Oxide Nanomaterials to Caenorhabditis Elegans. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2017, 201, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisichella, M.; Berenguer, F.; Steinmetz, G.; Auffan, M.; Rose, J.; Prat, O. Toxicity Evaluation of Manufactured CeO2 Nanoparticles before and after Alteration: Combined Physicochemical and Whole-Genome Expression Analysis in Caco-2 Cells. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safi, M.; Sarrouj, H.; Sandre, O.; Mignet, N.; Berret, J.-F. Interactions between Sub-10-Nm Iron and Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles and 3T3 Fibroblasts: The Role of the Coating and Aggregation State. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 145103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ould-Moussa, N.; Safi, M.; Guedeau-Boudeville, M.-A.; Montero, D.; Conjeaud, H.; Berret, J.-F. In Vitro Toxicity of Nanoceria: Effect of Coating and Stability in Biofluids. Nanotoxicology 2013, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Manturova, N.E.; Vasin, V.I.; Artyushkova, E.B.; Khokhlov, N.V.; Ivanov, A.V.; Stupin, V.A. Efficacy of A Novel Smart Polymeric Nanodrug in the Treatment of Experimental Wounds in Rats. Polymers 2020, 12, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.L.; Popova, N.R.; Tarakina, N.V.; Ivanova, O.S.; Ermakov, A.M.; Ivanov, V.K.; Sukhorukov, G.B. Intracellular Delivery of Antioxidant CeO 2 Nanoparticles via Polyelectrolyte Microcapsules. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 2453–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Ivanova, O.S.; Manturova, N.E.; Medvedeva, O.A.; Shevchenko, A.V.; Vorsina, E.S.; Achar, R.R.; Parfenov, V.A.; Stupin, V.A. Antimicrobial Activity of Citrate-Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, J.; Zhu, W.; Liu, C.; Gu, J. Bacteriostatic Effects of Cerium-Humic Acid Complex : An Experimental Study. BTER 2000, 73, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardas, S.S.; Butterfield, D.A.; Sultana, R.; Tseng, M.T.; Dan, M.; Florence, R.L.; Unrine, J.M.; Graham, U.M.; Wu, P.; Grulke, E.A.; et al. Brain Distribution and Toxicological Evaluation of a Systemically Delivered Engineered Nanoscale Ceria. Toxicological Sciences 2010, 116, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlander, U.; Moto, T.P.; Desalegn, A.A.; Yokel, R.A.; Johanson, G. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Nanoceria Systemic Distribution in Rats Suggests Dose- and Route-Dependent Biokinetics. IJN 2018, Volume 13, 2631–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zholobak, N.M.; Ivanov, V.K.; Shcherbakov, A.B.; Shaporev, A.S.; Polezhaeva, O.S.; Baranchikov, A.Ye.; Spivak, N.Ya.; Tretyakov, Yu.D. UV-Shielding Property, Photocatalytic Activity and Photocytotoxicity of Ceria Colloid Solutions. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2011, 102, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, K.L.; Estevez, A.Y.; DeCoteau, W.; Vangellow, S.; Ribeiro, S.; Chiarenzelli, J.; Hays-Erlichman, B.; Erlichman, J.S. Variable in Vivo and in Vitro Biological Effects of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle Formulations. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckman, K.L.; DeCoteau, W.; Estevez, A.; Reed, K.J.; Costanzo, W.; Sanford, D.; Leiter, J.C.; Clauss, J.; Knapp, K.; Gomez, C.; et al. Custom Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Protect against a Free Radical Mediated Autoimmune Degenerative Disease in the Brain. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 10582–10596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolati, S.; Babaloo, Z.; Jadidi-Niaragh, F.; Ayromlou, H.; Sadreddini, S.; Yousefi, M. Multiple Sclerosis: Therapeutic Applications of Advancing Drug Delivery Systems. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 86, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobyliak, N.M.; Falalyeyeva, T.M.; Kuryk, O.G.; Beregova, T.V.; Bodnar, P.M.; Zholobak, N.M.; Shcherbakov, O.B.; Bubnov, R.V.; Spivak, M.Y. Antioxidative Effects of Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles Ameliorate Age-Related Male Infertility: Optimistic Results in Rats and the Review of Clinical Clues for Integrative Concept of Men Health and Fertility. EPMA Journal 2015, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardas, S.S.; Sultana, R.; Warrier, G.; Dan, M.; Florence, R.L.; Wu, P.; Grulke, E.A.; Tseng, M.T.; Unrine, J.M.; Graham, U.M.; et al. Rat Brain Pro-Oxidant Effects of Peripherally Administered 5nm Ceria 30 Days after Exposure. NeuroToxicology 2012, 33, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.T.; Lu, X.; Duan, X.; Hardas, S.S.; Sultana, R.; Wu, P.; Unrine, J.M.; Graham, U.; Butterfield, D.A.; Grulke, E.A.; et al. Alteration of Hepatic Structure and Oxidative Stress Induced by Intravenous Nanoceria. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2012, 260, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.Y.; McGee, J.K.; Killius, M.G.; Suarez, D.A.; Blackman, C.F.; DeMarini, D.M.; Simmons, S.O. Investigating Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Responses Elicited by Silver Nanoparticles Using High-Throughput Reporter Genes in HepG2 Cells: Effect of Size, Surface Coating, and Intracellular Uptake. Toxicology in Vitro 2013, 27, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata, M.; Kandasamy, P.; Voelker, D.R. The Anti-inflammatory and Antiviral Properties of Anionic Pulmonary Surfactant Phospholipids. Immunological Reviews 2023, 317, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, F.; Cao, J.; Dou, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, W. Research Advances of Nanomaterials for the Acceleration of Fracture Healing. Bioactive Materials 2024, 31, 368–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Liang, Y.; Han, R.; Lu, W.-L.; Mak, J.C.W.; Zheng, Y. Rational Particle Design to Overcome Pulmonary Barriers for Obstructive Lung Diseases Therapy. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 314, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falchi, L.; Galleri, G.; Dore, G.M.; Zedda, M.T.; Pau, S.; Bogliolo, L.; Ariu, F.; Pinna, A.; Nieddu, S.; Innocenzi, P.; et al. Effect of Exposure to CeO2 Nanoparticles on Ram Spermatozoa during Storage at 4 °C for 96 Hours. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.-Y.; Oca-Cossio, J.; Agering, K.; Simpson, N.E.; Atkinson, M.A.; Wasserfall, C.H.; Constantinidis, I.; Sigmund, W. Novel Synthesis of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles for Free Radical Scavenging. Nanomedicine 2007, 2, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşayan, G.; Nejati, O.; Ceylan, A.F.; Karasu, Ç.; Kelicen Ugur, P.; Bal-Öztürk, A.; Zarepour, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Mostafavi, E. Tackling Chronic Wound Healing Using Nanomaterials: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Applied Materials Today 2023, 32, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Diehn, K.K.; Ko, S.W.; Tung, S.-H.; Raghavan, S.R. Can Simple Salts Influence Self-Assembly in Oil? Multivalent Cations as Efficient Gelators of Lecithin Organosols. Langmuir 2010, 26, 13831–13838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, X.; Song, Y.; Lan, L.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Du, Y. Nano Transdermal System Combining Mitochondria-Targeting Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles with All-Trans Retinoic Acid for Psoriasis. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 18, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassai, M.; Teopipithaporn, R.; Grant, K.B. Hydrolysis of Phosphatidylcholine by Cerium(IV) Releases Significant Amounts of Choline and Inorganic Phosphate at Lysosomal pH. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 2011, 105, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.E.; Basnet, K.; Grant, K.B. Tuning Cerium(IV)-Assisted Hydrolysis of Phosphatidylcholine Liposomes under Mildly Acidic and Neutral Conditions. ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Сlass of excipient | Excipient | Adding excipient before/after synthesis CeO2 | Еffects | Methods | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biopolymers | Polyacrylate | Not synthesized | Growth inhibition | In vitro Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | [34] |

| Polyacrylate | After synthesis | Antiviral | In vitro. L929, EPT and Vero cells | [35] | |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone | Before synthesis | Negative impact on the growth and development of larvae | In vitro. Drosophila melanogaster | [37] |

|

| Antioxidant | U937 cell line. in vivo | [36] |

|||

| Dextran | Before synthesis | High aggregative stability | In vitro | [31] | |

| Antimicrobial |

E. coli P. aeruginosa, S. epidermidis E. faecalis |

[31,45,46,47] |

|||

| Regenerative |

Human fibroblasts | [31] |

|||

| Antioxidant | MIN6, NIH3T3, HEK293T, Osteoblasts |

[41,49,51] | |||

| Biocompatibility |

Human fibroblasts HGF-1 | [42] | |||

| Cytotoxicity to tumor cells |

Osteosarcoma cells MG-63 |

[51] |

|||

| Less absorption by cells compared to other stabilizers | BGC-803 |

[55] |

|||

| photosensitivity | HUVEC, CCL-30 | [56] |

|||

| Dextran | After synthesis | High aggregative stability | In vitro | [43] | |

| Antimicrobial | E. coli, S. aureus | [43,44] | |||

| Regenerative | NIH 3T3, In vivo | [44] |

|||

| Antioxidant |

NIH 3T3, In vivo | [44] |

|||

| Slow release | neuroblastoma cells | [53] |

|||

| Cytotoxicity to tumor cells | neuroblastoma cells, HeLa | [53,54] | |||

| Dextran | Not synthesized | Cytotoxicity to tumor cells |

A549, HCT116, Hep3B, Caco-2 и HeLa | [52] | |

| Hyaluronic acid | Before synthesis | Cytotoxicity to tumor cells |

In vivo, MCF-7 | [70] |

|

| Anti-inflammatory | In vivo, ARPE-19, L929, RAW264.7, BV2 | [66] |

|||

| Anti-atherosclerotic | In vivo, MOVAS, RAW 264.7 | [57] | |||

| Hyaluronic acid | After synthesis | Antioxidant |

In vivo, HucMSC, Chondrocytes, Fibroblasts | [57,59,65] | |

| Cytotoxicity to tumor cells |

Fibroblasts, MDA-MB-231, KB, CT-26, MDA-MB-231 | [59,68,71] | |||

| Chitosan | Before synthesis | Biocompatibility | WEHI 164, ARPE-19 | [74,108] | |

| Cytoprotective |

ARPE-19, umbilical cord endothelium |

[108] |

|||

| Antimicrobial |

S. aureus, E. coli |

[85] |

|||

| Antioxidant | In vivo | [115] | |||

| Chitosan | After synthesis | Antioxidant |

In vivo, in vitro | [78,83,90] |

|

| Antimicrobial | S. aureus, E. coli, B. subtilis, MSSA, MRSA | [78,79,81,83,84,86,90] | |||

| Regenerative |

Fibroblasts, In vivo, human mesenchymal stem cells, ex vivo, L929, MC3T3-E1 cell | [73,78,83,84,90,97] |

|||

| Biocompatibility | In vivo, mesenchymal stem cells, MC3T3-E1 | [73,77,84,87,90] | |||

| Collagen | Before synthesis | Stabilization of collagen fibers | Ex vivo | [131] | |

| Collagen | After synthesis | Antioxidant |

in vivo, Ovarian cancer cells | [127,128] | |

| Regenerative |

hDPSC, in vivo | [126,127] | |||

| Anti-inflammatory | in vivo | [127] | |||

| Acceleration of angiogenesis | in vivo | [129] | |||

| Gelatin | Before synthesis | Antioxidant, antihypertrophic |

ex vivo | [136] | |

| Gelatin | After synthesis | Antioxidant | MC3T3-E1, In-ovo, L929, MG-63, HaCaT | [84,133,139,147] |

|

| Anti-inflammatory | in vivo | [155] | |||

| Antimicrobial | S. Aureus. E. Coli | [84,139,147] | |||

| Regenerative | in vivo, HaCaT, RAW264.7, MG-63, MC3T3-E1 | [133,134,139,141,142,144] | |||

| Gelatin | Not synthesized | Antioxidant | SH-SY5Y | [151] | |

| Regenerative | in vivo |

[153] |

|||

| Antimicrobial | P. aeruginosa | [146] |

|||

| Fatty substances | Lecithin | After synthesis | Biocompatibility | ram sperm | [193] |

| Antioxidant |

ram sperm, HaCat | [193,197] | |||

| Phospholipids | Phosphatidylcholine | Before synthesis | Antioxidant | betaTC-tet | [194] |

| Polycarboxylic acids | Mellitic acid | Before synthesis | Stability | In vitro |

[157] |

| Dicarboxylic acids | Malic acid | After synthesis | Stability | In vitro | [165] |

| Monocarboxylic acids | Acetic acid | After synthesis | Antitumor | DMEM, HT-29, NCBI -C466, HFFF2, NCBI -C163 | [164] |

| Polycarboxylic acids | Citrate | Before synthesis | Antioxidant | In vivo |

[170,176,186] |

| Regenerative |

Fibroblasts, human mesenchymal stem cells, human keratinocytes In vivo |

[17,176] |

|||

| Antimicrobial | B. subtilis, B. cereus, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, P. vulgaris, C. albicans, A. brasielensis | [178] | |||

| Stimulation of bacterial growth |

E. coli, B. pyocyaneus, S. aureus, Leuconostoc, Streptococcus faecalis | [179] |

|||

| Lack of pro- or antioxidant | In vivo | [180] | |||

| Prooxidant | In vivo | [187] | |||

| Cytoprotective | L929, VERO | [182] | |||

| Citrate | After synthesis | High cellular uptake | NIH/3T3 | [174] | |

| Toxicity in high doses |

NIH/3T3 | [175] | |||

| Prooxidant | NIH/3T3, In vivo | [175,188] | |||

| Accumulation in the reticuloendothelial system | In vivo |

[167] |

|||

| Regenerative |

Fibroblasts, human mesenchymal stem cells, human keratinocytes | [17] |

|||

| Antioxidant |

In vivo, RAW264.7, Hippocampal ischemia-based model of oxidative stress ex vivo |

[183,184] | |||

| Antioxidant | In vivo | [171] | |||

| Citrate | Not synthesized | Reduced toxicity | Caco-2 | [173] | |

| Pharmacokinetics dependence on the route of administration and dose | In silico | [181] | |||

| High aggregative stability | In vitro | [34] | |||

| Amino acids | Glutamic acid | After synthesis | Antioxidant | HT22 | [161] |

| Amino acid derivatives | N-acetylcysteine | Not synthesized | Antioxidant | SMMC-7721 | [162] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).