Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has become an invaluable tool for elucidating the structural, dynamic, and compositional properties of chemical compounds across various fields, from organic and inorganic chemistry to materials science. This review summarizes recent advancements in solid-state NMR techniques, including high-field NMR, magic-angle spinning (MAS), and multidimensional approaches, which have significantly enhanced spectral resolution and sensitivity. The review explores applications in studying crystalline and amorphous compounds, probing atomic-level structure, and investigating molecular dynamics critical to catalysts, polymers, pharmaceuticals, and complex hybrid materials. Additionally, it highlights the synergy between solid-state NMR and other characterization methods, such as X-ray diffraction and electron microscopy, which together provide a comprehensive understanding of material properties. Concluding with an outlook on future developments, this review underscores solid-state NMR’s growing impact on molecular and materials characterization.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. NMR Techniques

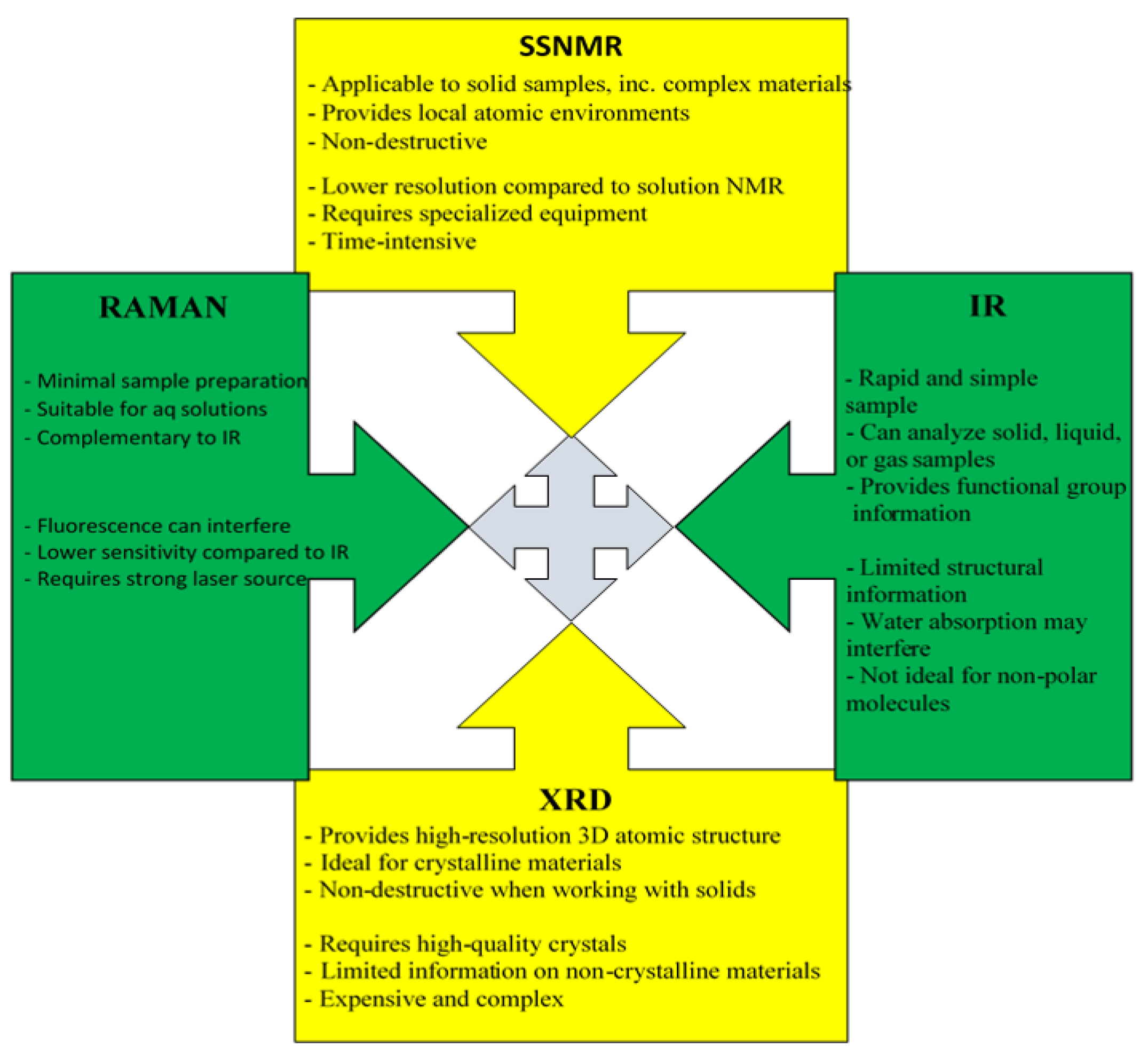

In-Depth Analysis of NMR, Solid-State NMR, IR, Raman, and X-Ray Diffraction Techniques

IR Spectroscopy

Raman Spectroscopy

X-Ray Diffraction

3. Results and Discussion

Inorganic and Organic Compounds

5. Future Directions and Structure-Property Relationship:

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yeongseo An, Sergey L. Sedinkin and Vincenzo Venditti. Solution NMR methods for structural and thermodynamic investigation of nanoparticle adsorption equilibria. Nanoscale Adv., 2022, 4, 2583-2607. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohan, A. B. A. Andersen, J. Mareš, N. D. Jensen, U. G. Nielsen, J. Vaara. Unravelling the effect of paramagnetic Ni²⁺ on the ¹³C NMR shift tensor for carbonate in Mg₂₋ₓNiₓ Al layered double hydroxides by quantum-chemical computations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Uzal-Varela, F. Lucio-Martínez, A. Nucera, M. Botta, D. Esteban-Gómez, L. Valencia, A. Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C. Platas-Iglesias. A systematic investigation of the NMR relaxation properties of Fe(III)-EDTA derivatives and their potential as MRI contrast agents. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ö. Üngör, S. Sanchez, T. M. Ozvat, J. M. Zadrozny. Asymmetry-enhanced 59Co NMR thermometry in Co(III) complexes. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, H. T. Fei, G. T. Liu, W. Wang, Y. J. Sun, C. J. Wu. Exploring paramagnetic NMR and EPR for studying the bonding in actinide complexes. Dalton Transactions, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Göthner, K. Lehmann, D. Grote, A. L. Spek, J. P. Hill, M. Ikeda. NMR studies on manganese(II) complexes for enhanced relaxivity in MRI applications. Inorg. Chem., 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Shin, S. J. Lee, T. J. Kim, K. G. Lee, D. H. Kang, J. T. Son. Analyzing 31P NMR shifts in molybdenum phosphide nanoclusters. J. Mol.Str., 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Adams, C. J. Hines, M. L. Rodriguez. Utilizing high-field NMR for detection of low-spin iron(III) centers in bioinorganic complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Bai, A. Y. Lee, J. Chen, Z. Ma. Coordination dynamics in copper(I) complexes: A study through variable-temperature NMR. Inorg. Chem. Commun., 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. L. Brett, R. D. Armstrong, S. P. Thomas, C. J. McQueen. Exploring transition metal complex environments via 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopy. Chemistry - A European Journal, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Middleton, D.A., Griffin, J., Esmann, M., Fedosova, N.U. Solid-state NMR chemical shift analysis for determining the conformation of ATP bound to Na,K-ATPase in its native membrane. RSC Advances, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E., et al. Recent progress in solid-state NMR of spin-½ low-γ nuclei applied to inorganic materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., et al. Advanced Solid-State NMR Studies of Transition Metal Complexes. J. Americ. Chem.l Soc., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sahoo, S. K. Structural insights into metallocomplexes via SSNMR and DFT. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pyykkö, P., et al. Analyzing the crystal lattice effects in inorganic complexes by MAS SSNMR. Dalton Transactions, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Saito, T. Exploring ligand field environments in metal complexes by SSNMR. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M., et al. Solid-state NMR of paramagnetic inorganic materials. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., et al. Applications of solid-state NMR in transition metal coordination complexes. Chemical Society Reviews, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, M.; et al. Insights into metal-oxo complexes via SSNMR. Chemistry - A European Journal, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.F.; et al. High-resolution SSNMR for probing zeolite frameworks and associated metals. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; et al. SSNMR in elucidating bimetallic complex structures. Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; et al. Computational solid-state NMR on organometallic systems. Computational Chemistry, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.E.; et al. Dynamic nuclear polarization in SSNMR for metal complexes. J. Americ. Chem. Soc., 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ivanchikova, I.D.; et al. SSNMR insights into catalytic active sites in complex oxides. Catalysis Today, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, H.; et al. Metal-organic frameworks studied by SSNMR. Chemical Reviews, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.R.; et al. SSNMR computational methods for inorganic complexes. J. Chem. Phys., 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ashbrook, S.E.; Wimperis, S. Exploring quadrupolar nuclei in inorganic systems using SSNMR. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mason, H.E.; et al. Applications of SSNMR in porous and microporous materials. Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; et al. Advanced SSNMR for characterizing complex inorganic networks. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Feyrer, F.; et al. NMR crystallography applications in metal complex structures. Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.; et al. SSNMR characterization of metal-ligand coordination frameworks. Dalton Transactions, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, M.; et al. SSNMR of metal oxides in catalysis.Topics in Catalysis, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.; et al. Developments in SSNMR techniques for coordination chemistry. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.B.; et al. Solid-state 15N NMR of nitrogen-rich complexes. Inorg. Chem., 2010. [CrossRef]

- Kaupp, M.; et al. Computational SSNMR approaches in metallocomplexes. Chem. Phys. Lett., 2010. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Reguant, A., Reis, H., Medveď, M., Luis, J. M., & Zaleśny, R. A New Computational Tool for Interpreting the Infrared Spectra of Molecular Complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 11658-11664. [CrossRef]

- Golea, C. M.; Codină, G. G.; Oroian, M. Prediction of Wheat Flours Composition Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry (FT-IR). Food Control 2023, 143, 109318. [CrossRef]

- Yaman, H.; Aykas, D. P.; Rodriguez-Saona, L. E. Monitoring Turkish White Cheese Ripening by Portable FT-IR Spectroscopy. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1107491. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Peng, H.; Li, L.;Wen, L.; Chen, X.; Zong, X. FT-IR Combined with Chemometrics in the Quality Evaluation of Nongxiangxing Baijiu. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2023, 284, 121790. [CrossRef]

- Laouni, A.; El Orche, A.; Elhamdaoui, O.; Karrouchi, K.; El Karbane, M.; Bouatia, M. A. Preliminary Study on the Potential of FT-IR Spectroscopy and Chemometrics for Tracing the Geographical Origin of Moroccan Virgin Olive Oils. J. AOAC Int. 2023, 106 (3), 804–812. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Tirado, J. P.; de Franca, R. L.; Tumbajulca, M.; Barraza-Jauregui, G.; Barbin, D. F. Detection of Cumin Powder Adulteration with Allergenic Nutshells Using FT-IR and Portable NIRS Coupled with Chemometrics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 116, 105044. [CrossRef]

- Hajiseyedrazi, Z. S.; Khorrami, M. K.; Mohammadi, M. Alternating Conditional Expectation (ACE) Algorithm and Supervised Classification Models for Rapid Determination and Classification of Adulterated Cinnamon Samples Using Diffuse Reflectance FT-IR Spectroscopy. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 131, 106226. [CrossRef]

- Reale, S.; Biancolillo, A.; Foschi, M.; Di Donato, F.; Di Censo, E.; D’Archivio, A. A. Geographical Discrimination of Italian Carrot (Daucus carota L.) Varieties: A Comparison Between ATR FT-IR Fingerprinting and HS-SPME/GC-MS Volatile Profiling. Food Control 2023, 146, 109508. [CrossRef]

- Sari, N.; Widiastuti, E. L.; Pratami, G. D. Microplastic Analysis at Seawater and Sediment in the Mahitam Island Lampung Bay Using FT-IR. J. Biol. Exp. Biodivers. 2023, 10 (1), 7–13. [CrossRef]

- El Orche, A.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Olive Oil Polyphenols Using FT-IR and GC-MS. Anal. Chem. Insights 2022, 14, 43–57. [CrossRef]

- Koubaa, Z.; Rouatbi, L.; Marrakchi, F.; Salih, B. Infrared Spectroscopic Study on Coordination in Metal Complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1185, 132-145. [CrossRef]

- Ben Brahim, K.; Ben Gzaiel, M.; Oueslati, A.; Khirouni, K..; Gargouri, M.; Corbel, G.; Bardeau, J.-F. Organic–inorganic interactions revealed by Raman spectroscopy during reversible phase transitions in semiconducting [(C₂H₅)₄N]FeCl₄. RSC Advances 2021, 11, 18651-18660. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhai, Y.; Cui, X.; Liu, J. Raman spectroscopy for in situ monitoring of reactions and phase transitions in metal–organic frameworks. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers 2020, 7(14), 2713-2720. [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, X.; Li, G. Raman spectroscopic investigation of the structural changes in rare earth–metal phosphates. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 2019, 50(3), 524-533. [CrossRef]

- Kocak, Y.; Orhan, H. E.; Saka, E. T.; Demirbas, U. Insights into the structure of oxalate-based metal complexes using Raman and IR spectroscopy. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2018, 202, 268-275. [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Das, S.; Sen, P. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering study of transition metal complexes in inorganic matrices. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2017, 5(14), 6694-6703. [CrossRef]

- Green, V.; Baxter, E. Raman spectroscopy of vanadyl–phosphate complexes: Implications for structural characterization. Inorganic Chemistry 2016, 55(7), 3156-3162. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. M.; Ellis, A. Using Raman and IR spectroscopy to monitor hydrolysis reactions in titanium complexes. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2015, 426, 145-152. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.: Patra, A. Metal-ligand vibrations in coordination compounds: Raman and IR spectroscopic analysis. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2013, 257(3-4), 579-591. [CrossRef]

- Sekine, Y.; Nihei, M.; Kumai, R.; Nakao, H.; Murakami, Y.; Oshio, H. Investigation of the light-induced electron-transfer-coupled spin transition in a cyanide-bridged [Co₂Fe₂] complex by X-ray diffraction and absorption measurements. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2014, 1(4), 540-543. [CrossRef]

- Matteppanavar, S.; Rayaprol, S.; Singh, K.; Raghavendra Reddy, V.; Angadi, B. Structural, magnetic, and dielectric properties of perovskite-type complex oxides La₃FeMnO₇ studied using X-ray diffraction. J. Mater. Sci., 2015, 50(13), 4980-4993. [CrossRef]

- Mustafin, E.S.; Mataev, M.M.; Kasenov, R.Z.; Pudov, A.M.; Kaykenov, D.A. Synthesis and X-ray diffraction studies of a new pyrochlore oxide (Tl₂Pb)(MgW)O₇. Inorganic Materials, 2014, 50(5), 672-675. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.; Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nature Materials, 2007, 6(1), 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Valencia, S.; Konstantinovic, Z.; Schmitz, D.; Gaupp, A. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism study of cobalt-doped ZnO. Physical Review B, 2011, 84, 024413. [CrossRef]

- Harder, R.; Robinson, I.K. Three-dimensional mapping of strain in nanomaterials using X-ray diffraction microscopy. New Journal of Physics, 2010, 12, 035019. [CrossRef]

- Newton, M.C.; Leake, S.J.; Harder, R.; Robinson, I.K. Three-dimensional imaging of strain in ZnO nanorods using coherent X-ray diffraction. Nature Materials 2010, 9, 120-125. [CrossRef]

- Cha, W.; Ulvestad, A.; Kim, J.W. Coherent diffraction imaging of crystal strains and phase transitions in complex oxide nanocrystals. Nature Communic. 2018, 9, 3422. [CrossRef]

- Diao, J.; Ulvestad, A. In situ study of ferroelastic domain wall dynamics in BaTiO₃ nanoparticles by X-ray diffraction microscopy. Physical Review Materials, 2020, 4, 053601. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Robinson, I.K. Real-time observation of defect dynamics during oxidation in Pt nanoparticles using coherent X-ray diffraction imaging. Nano Letters 2015, 15(7), 5044-5051. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M.A.; Williams, G.J.; Vartanyants, I.A.; Harder, R.; Robinson, I.K. Three-dimensional mapping of a deformation field inside a nanocrystal using coherent X-ray diffraction. Nature 2006, 442, 63-66. [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Nam, D. Quantitative imaging of single, unstained viruses with coherent X-rays. Physical Review Letters, 2014, 101, 158101. [CrossRef]

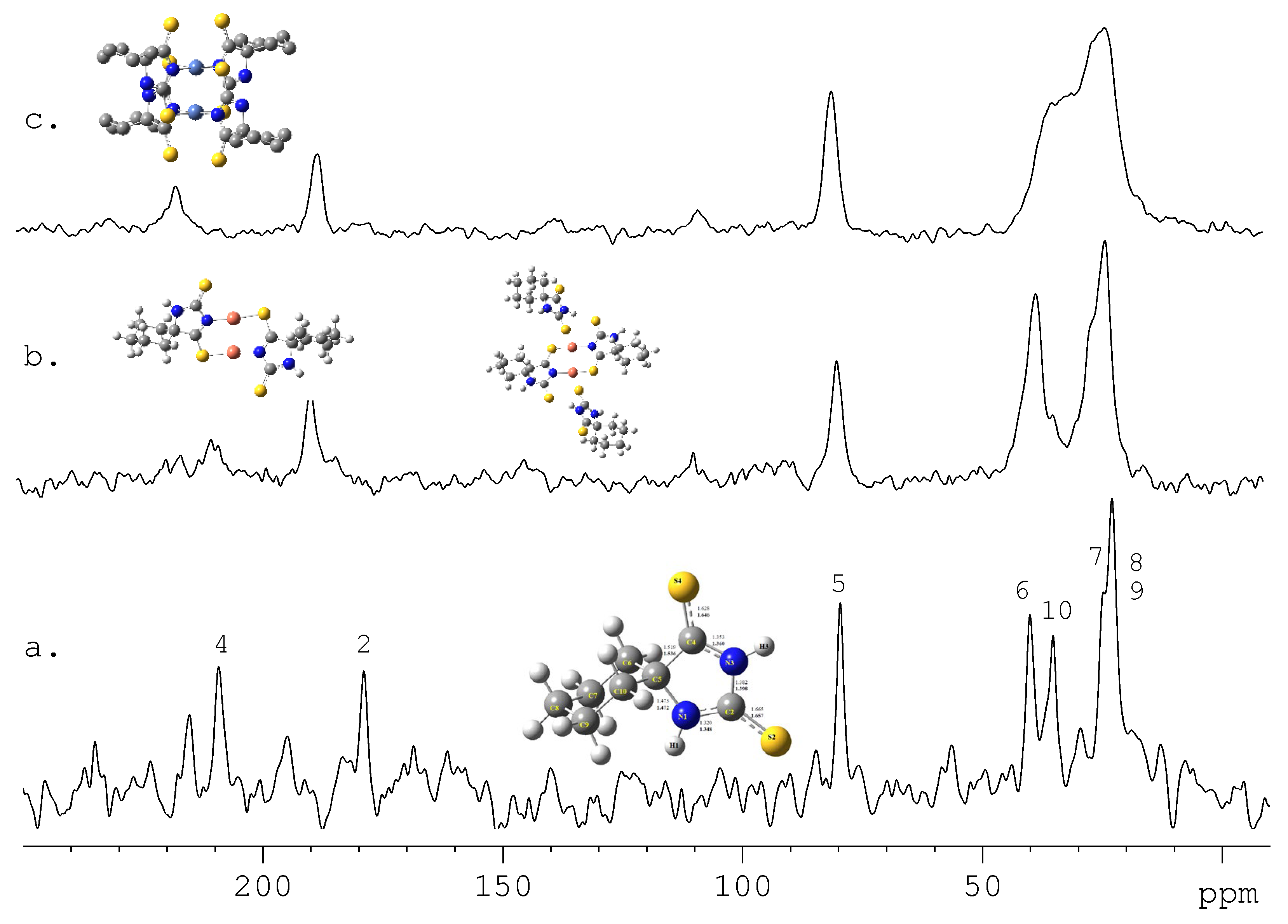

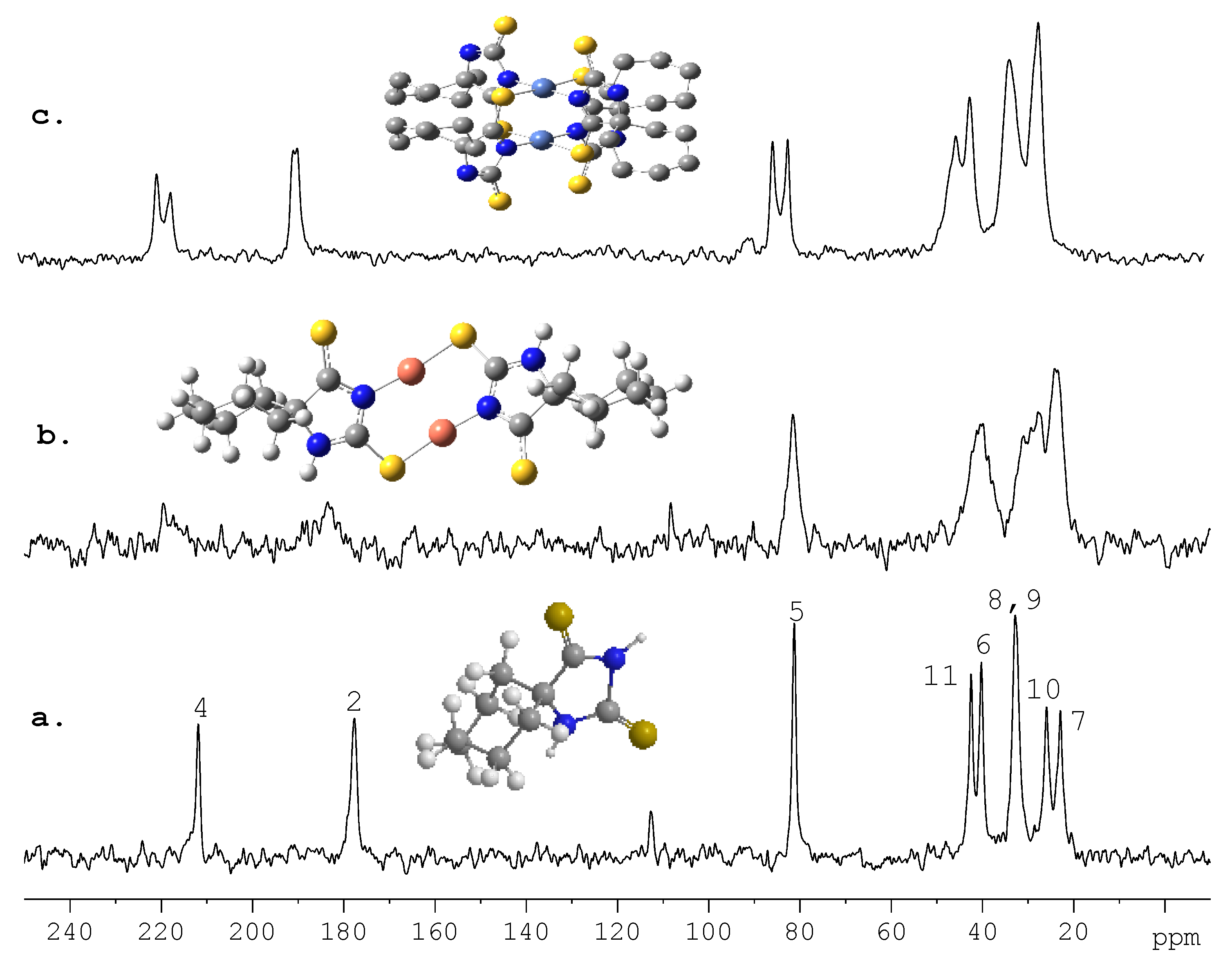

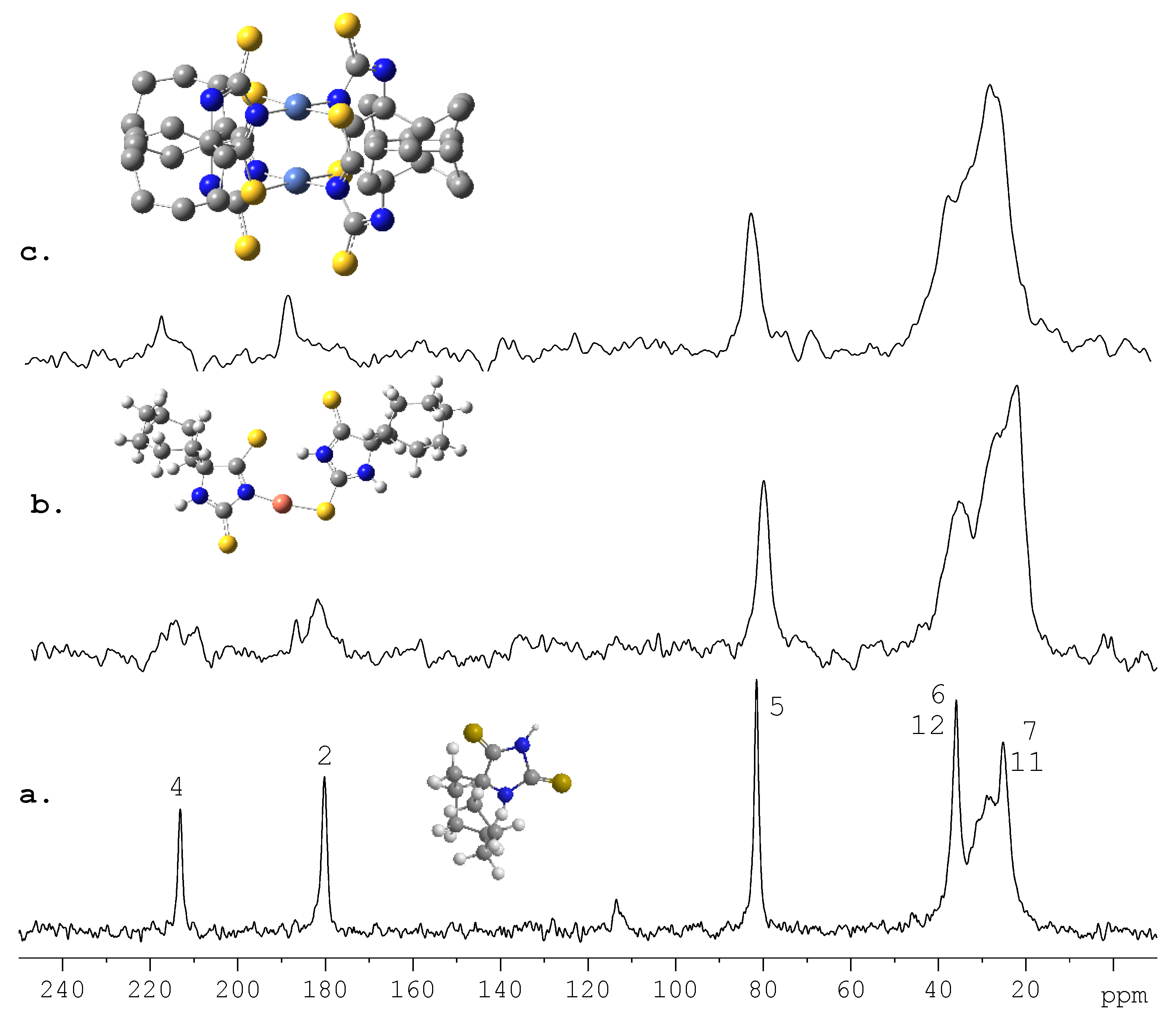

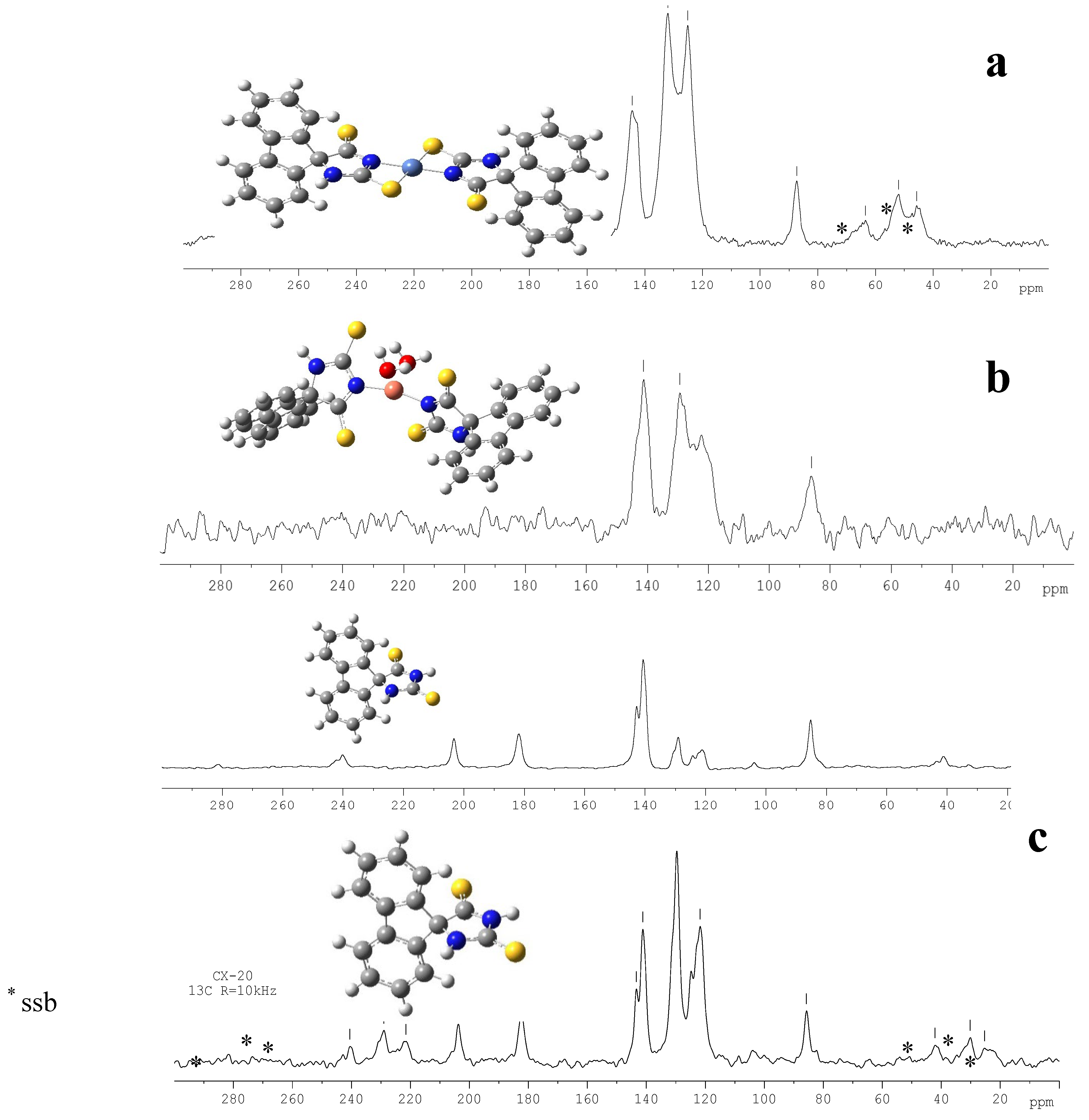

- Ahmedova, A.; Marinova, P.; Paradowska, K.; Stoyanov, N.; Wawer, I.; Mitewa, M. Spectroscopic aspects of the coordination modes of 2,4-dithiohydantoins: Experimental and theoretical study on copper and nickel complexes of cyclohexanespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoin), Inorg. Chim. Acta 2010, 363, 3919-3925. [CrossRef]

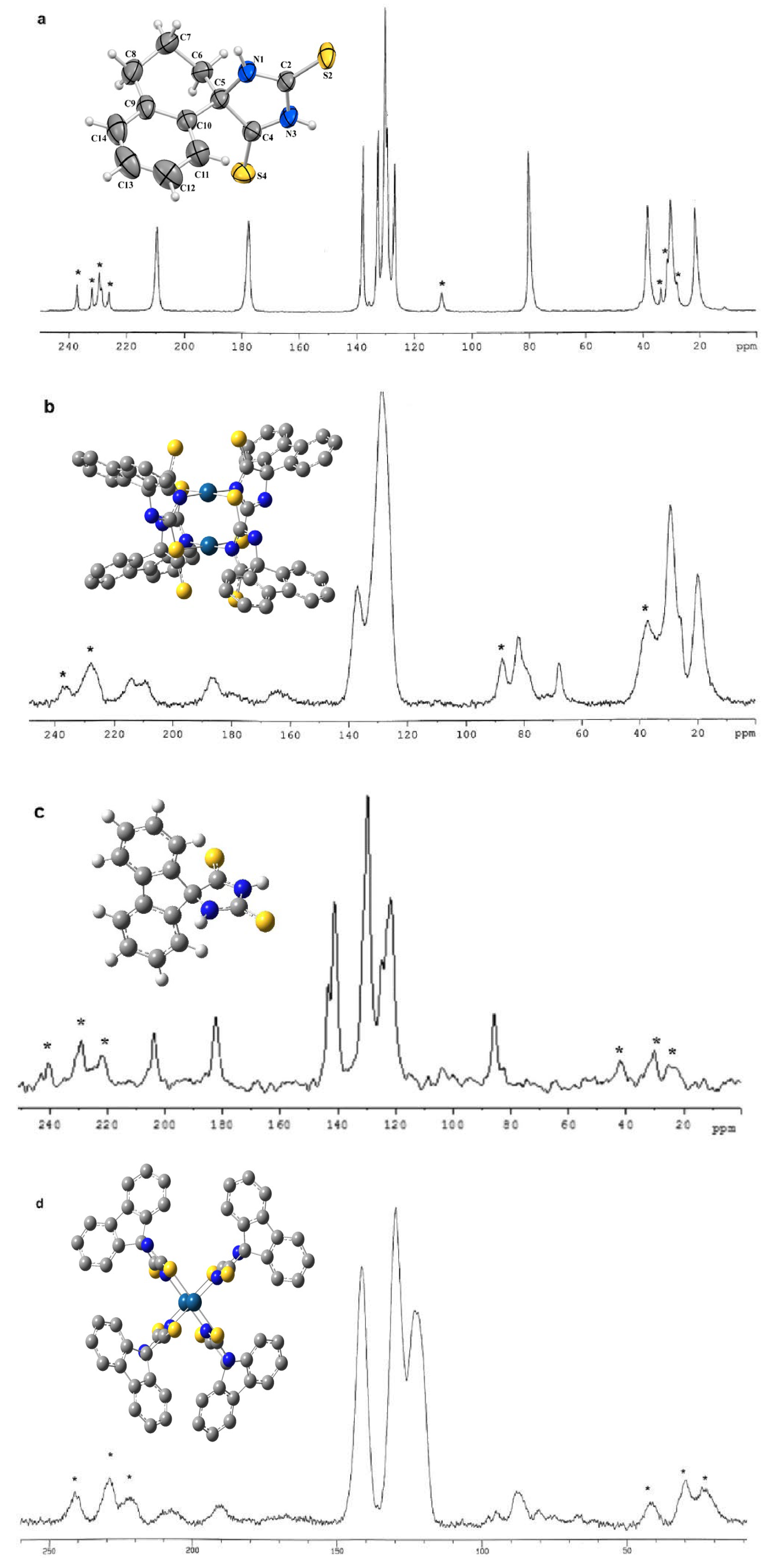

- Ahmedova, A.; Marinova, P.; Paradowska, K.; Marinov, M.; Wawer, I.; Mitewa, M. Structure of 2,4-dithiohydantoin complexes with copper and nickel – Solid-state NMR as verification method, Polyhedron 2010, 29, 1639-1645. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedova, A.; Pavlović, G.; Marinov, M.; Marinova, P.; Momekov, G.; Paradowska, K.; Yordanova, S.; Stoyanov, S.; Vassilev, N.; Stoyanov N. Synthesis and anticancer activity of Pt(II) complexes of spiro-5-substituted 2,4-dithiohydantoins”, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 528, Article number 120605. doi.org/10.1016/j.ica.2021.120605.

- Ahmedova, A.; Marinova, P.; Paradowska, K.; Marinov, M.; Mitewa, M. Synthesis and characterization of Copper(II) and Ni(II) complexes of (9’-fluorene)-spiro-5-dithiohidantoin, J.Mol.Str. 2008, 892, 13-19. [CrossRef]

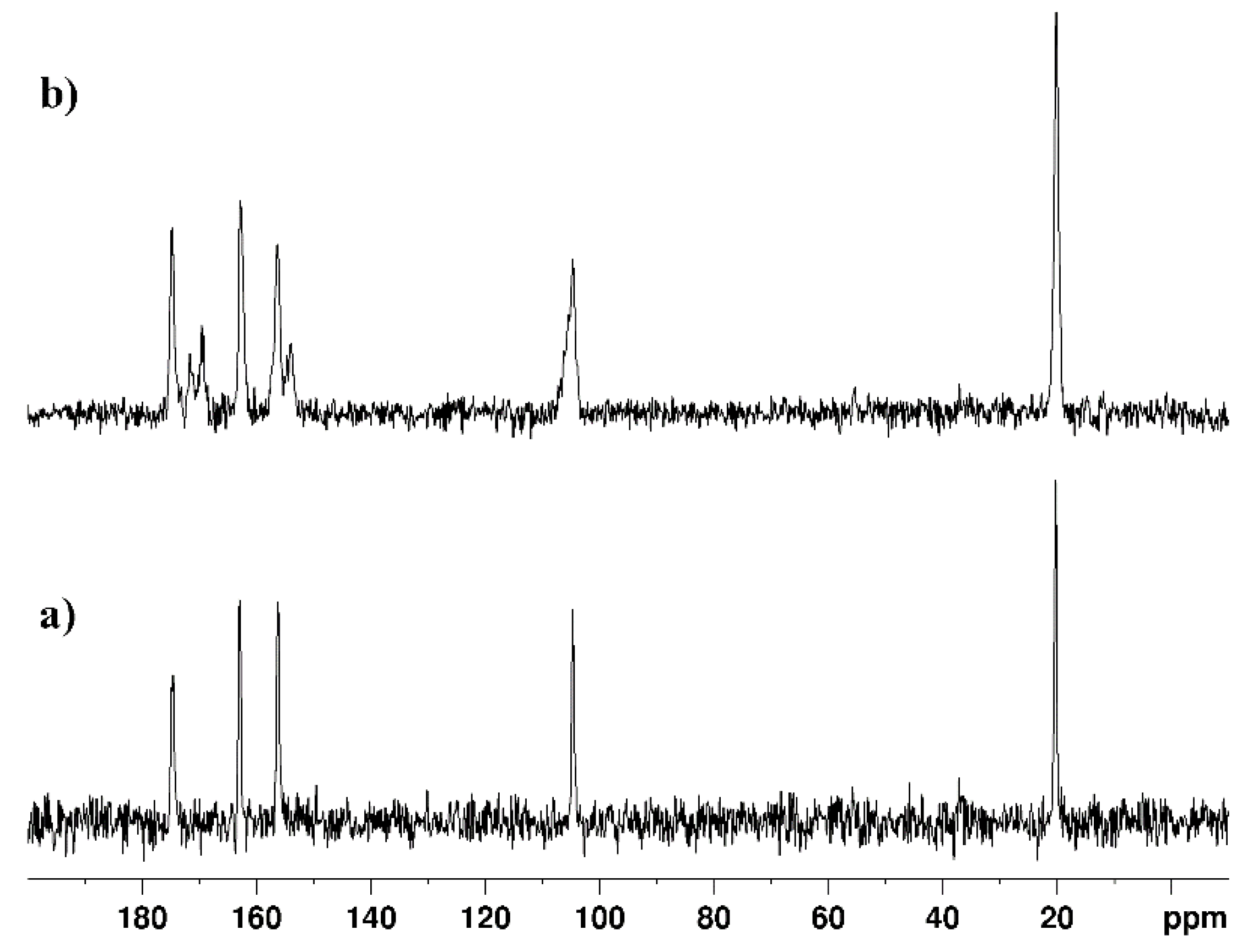

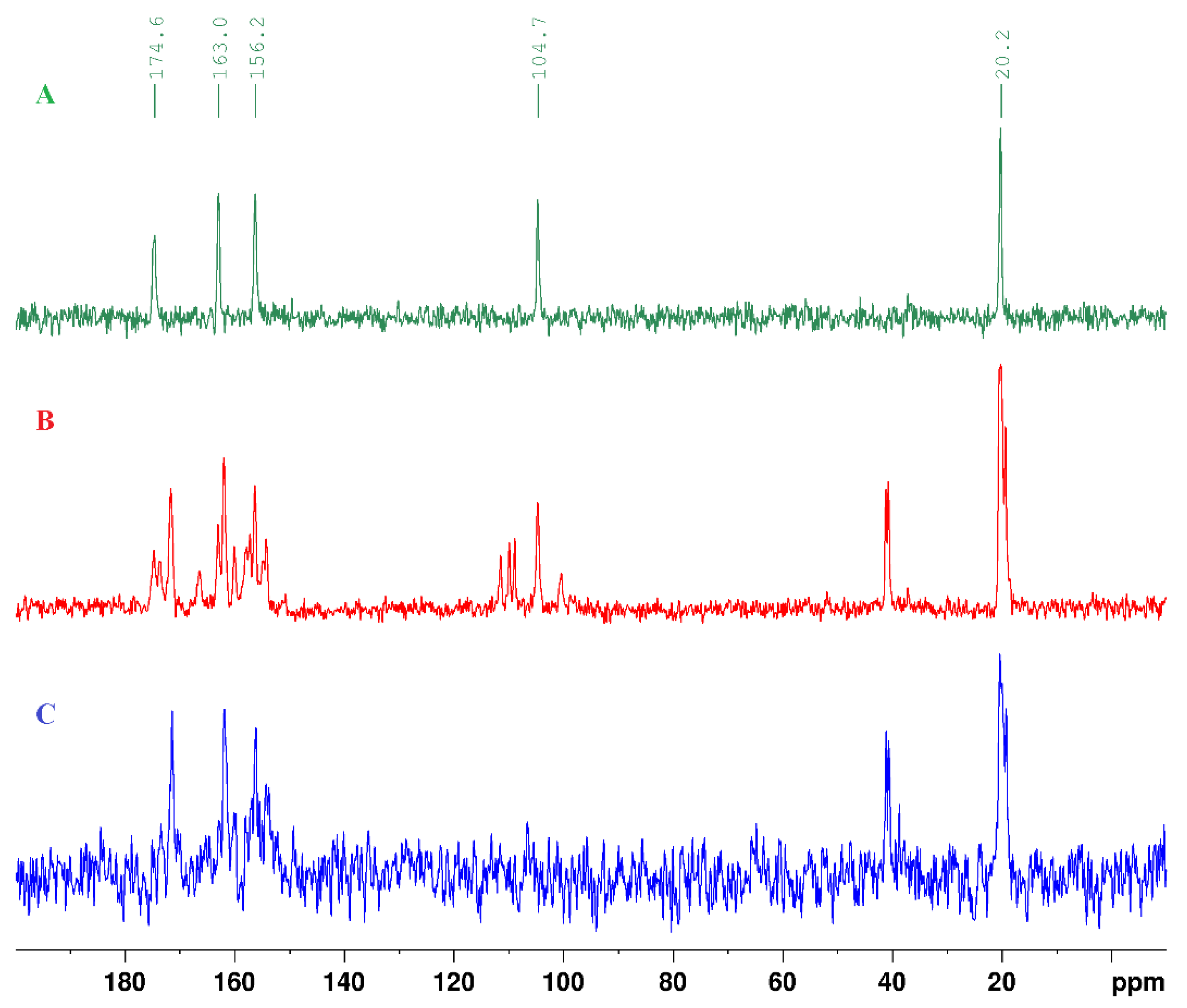

- Ahmedova, A.; Paradowska, K.; Wawer I. 1H, 13C MAS NMR and DFT GIAO study of quercetin and its complex with Al(III) in solid state, J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 110, 27-35. [CrossRef]

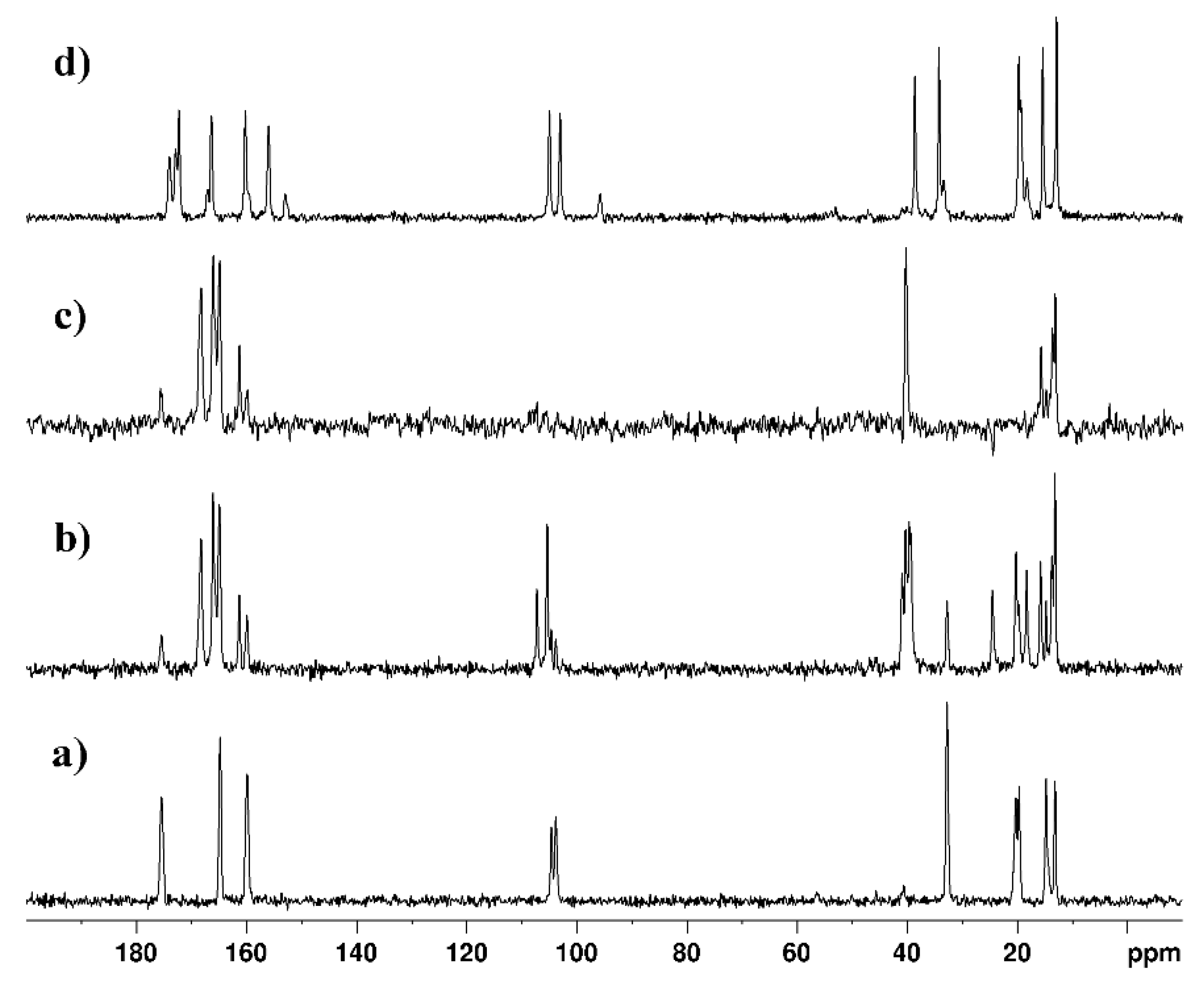

- Marinova, P.; Hristov,M.; Tsoneva, S.; Burdzhiev,N.; Blazheva, D.; Slavchev, A.; Varbanova, E.; Penchev, P. Synthesis, Characterization, and Antibacterial Studies of New Cu(II) and Pd(II) Complexes with 6-Methyl-2-Thiouracil and 6-Propyl-2-Thiouracil. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13150-13168. [CrossRef]

- Marinova, P.; Stoitsov, D.; Burdzhiev, N.; Tsoneva, S.; Blazheva, D.; Slavchev, A.; Varbanova, E.; Penchev, P. Investigation of the Complexation Activity of 2,4-Dithiouracil with Au(III) and Cu(II) and Biological Activity of the Newly Formed Complexes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6601. [CrossRef]

- Marinova, P.; Burdzhiev, N.; Blazheva, D.; Slavchev, A. Synthesis and Antibacterial Studies of a New Au(III) Complex with 6-Methyl-2-Thioxo-2,3-Dihydropyrimidin-4(1H)-One. Molbank 2024, 2024, M1827. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedova, A.; Marinova, P.; Paradowska, K.; Tyuliev, G.; Marinov, M.; Stoyanov, N. Spectroscopic study on the solid state structure of Pt(II) complexes of cycloalkanespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoins), Bulg. Chem. Communic., 2024, Vol. 56, Special Issue C, 89-95. [CrossRef]

- Gup, R.; Gokce, C. Coordination Chemistry of Schiff Bases and their Metal Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 296, 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovi’c, M.G.; Radnovi’c, N.D.; Barta Holló, B. Radanovi’c, M.M.; Kordi’c, B.B.; Raiˇcevi’c, V.N.; Vojinovi’c-Ješi’c, L.S.; Rodi’c, M.V. Polymeric Copper(II) Complexes with a Newly Synthesized Biphenyldicarboxylic Acid Schiff Base Ligand—Synthesis, Structural and Thermal Characterization. Inorganics 2022, 10, 261. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Mirza, Z. Schiff Base Complexes as Antimicrobial Agents. J. Mol. Str. 2017, 1154, 187-201. [CrossRef]

- Altowyan, M.S.; Soliman, S.M.; Al-Wahaib, D.; Barakat, A.; Ali, A.E.; Elbadawy, H.A. Synthesis of a New Dinuclear Ag(I) Complex with Asymmetric Azine Type Ligand: X-ray Structure and Biological Studies. Inorganics 2022, 10, 209. [CrossRef]

- Jevtovic, V.; Golubovi’c, L.; Alshammari, O.A.O.; Alhar, M.S.; Alanazi, T.Y.A.; Rad-ulovi’c, A.; Nakarada, Ð.; Dimitri’c Markovi’c, J.; Raki’c, A.; Dimi’c, D. Structural, Antioxidant, and Protein/DNA-Binding Properties of Sul-fate-Coordinated Ni(II) Complex with Pyridox-al-Semicarbazone (PLSC) Ligand. Inorganics 2024, 12, 280. [CrossRef]

- Sinicropi, M.S.; Ceramella,J.; Iacopetta, D.; Catalano, A.; Mariconda, A.; Rosano, C.; Saturnino, C.; El-Kashef, H.; Longo, P. Metal Complexes with Schiff Bases: Data Collection and Recent Studies on Biological Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14840. [CrossRef]

- Fathalla, E.M.; Abu-Youssef, M.A.M.; Sharaf, M.M.; El-Faham, A.; Barakat, A.; Haukka, M.; Soliman, S.M. Synthesis, X-ray Structure of Two Hexa-Coordinated Ni(II) Complexes with s-Triazine Hydrazine Schiff Base Ligand. Inorganics 2023, 11, 222. https:// doi.org/10.3390/inorganics11050222.

- Kargar, H.; Meybodi, F.A.; Ardakani, R.B.; Elahifard, M.R.; Torabi, V.; Mehrjardi, M.F.; Tahir, M.N.; Ashfaq, M.; Munaware, K.S. Synthesis, crystal structure, theoretical calculation, spectroscopic and antibacterial activity studies of copper (II) complexes bearing bidentate Schiff base ligands derived from 4-aminoantipyrine: Influence of substitutions on antibacterial activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1230, 129908. [CrossRef]

- Kargar, H.; Nateghi-Jahromi, M.; Fallah-Mehrjardi, M.; Behjatmanesh-Ardakani, R.; Munawar, K.S.; Ali, S.; Ashfaq, M.; Tahir, M.N. Synthesis, spectral characterization, crystal structure and catalytic activity of a novel dioxomolybdenum Schiff base complex containing 4-aminobenzhydrazone ligand: A combined experimental and theoretical study. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1249, 131645. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shboul, T.M.A.; El-khateeb, M.; Obeidat, Z.H.; Ababneh, T.S.; Al-Tarawneh, S.S.; Al Zoubi, M.S.; Alshaer,W.; Abu Seni, A.; Qasem, T.; Moriyama, H.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, Computational and Biological Activity of Some Schiff Bases and Their Fe, Cu and Zn Complexes. Inorganics 2022, 10, 112. [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.N.R.; Nayak, B. Photoluminescent Metal-Organic Complexes with Schiff Bases for Optoelectronics. J. Phys. Chem. 2018, 122(4), 432-442. [CrossRef]

- Zimina, A.M.; Somov, N.V.; Malysheva, Y.B.; Knyazeva, N.A.; Piskunov, A.V.; Grishin, I.D. 12-Vertex clo-so-3,1,2- Ruthenadicarba-dodecaboranes with Chelate POP-Ligands: Synthesis, X-ray Study and Electrochemical Properties. Inorganics 2022, 10, 206. [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, E.; Ankudinov, A.; Chepurnaya, I.; Ti-monov, A.; Karushev, M. In-Situ EC-AFM Study of Electrochemical P-Doping of Polymeric Nickel(II) Com-plexes with Schiff base Lig-ands. Inorganics 2023, 11, 41. [CrossRef]

- Vladimirova, K. G.; Freidzon, A. Ya.; Kotova, O. V.; Vaschenko, A. A.; Lepnev, L. S.; Bagatur’yants, A. A.; Vitukhnovskiy, A. G.; Stepanov, N. F.; Alfimov M. V. Theoretical Study of Structure and Electronic Absorption Spectra of Some Schiff Bases and Their Zinc Complexes, Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 23, 11123–11130. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Applications of Schiff Base Complexes in Solar Cells. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 2020, 210, 110550. [CrossRef]

- M. Radanović, Mirjana, and Marijana S. Kostić. Schiff Bases and Their Metal Complexes in Solar Cells. Advances in Analytical Chemistry - Applications and Innovations [Working Title] 2024. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, D. Structure-Property Relationships in Schiff Base-Metal Complexes for Advanced Functional Materials. Advanced Materials 2021, 33(5), 2100035. [CrossRef]

- Berkson Z, Björgvinsdóttir S, Yakimov A, Gioffrè D, Korzyński M, Barnes A, et al. Solid-state NMR spectra of protons and quadrupolar nuclei at 28.2 T: resolving signatures of surface sites with fast magic angle spinning. ChemRxiv. 2022;. [CrossRef]

- Sai S. H. Dintakurti, David Walker, Tobias A. Bird, Yanan Fang, Tim Whited and John V. Hanna. A powder XRD, solid state NMR and calorimetric study of the phase evolution in mechanochemically synthesized dual cation (Csx(CH3NH3)1-x)PbX3 lead halide perovskite systems, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2022, 24, 18004-18021. [CrossRef]

- Altenhof, A. R.; Jaroszewicz, M. J.; Frydman L.; Schurko, R. W. 3D relaxation-assisted separation of wideline solid-state NMR patterns for achieving site resolution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 22792-22805. [CrossRef]

- Cano, A. Faz.; Mermut, A. R.; Ortiz, R.; Benke, M. B.; Chatson B. 13C CP/MAS-NMR spectra of organic matter as influenced by vegetation, climate, and soil characteristics in soils from Murcia, Spain. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2002, 82(4), 403-411. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, P.T.; Hult, E.L.; Wickholm, K.; Pettersson, E.; Iversen, T. CP/MAS 13C-NMR spectroscopy applied to structure and interaction studies on cellulose I. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 1999, 15(1), 31-40. [CrossRef]

- Etsuko Katoh, Katsuyoshi Murata, Naoko Fujita. 13C CP/MAS NMR Can Discriminate Genetic Backgrounds of Rice Starch. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 38, 24592–24600. [CrossRef]

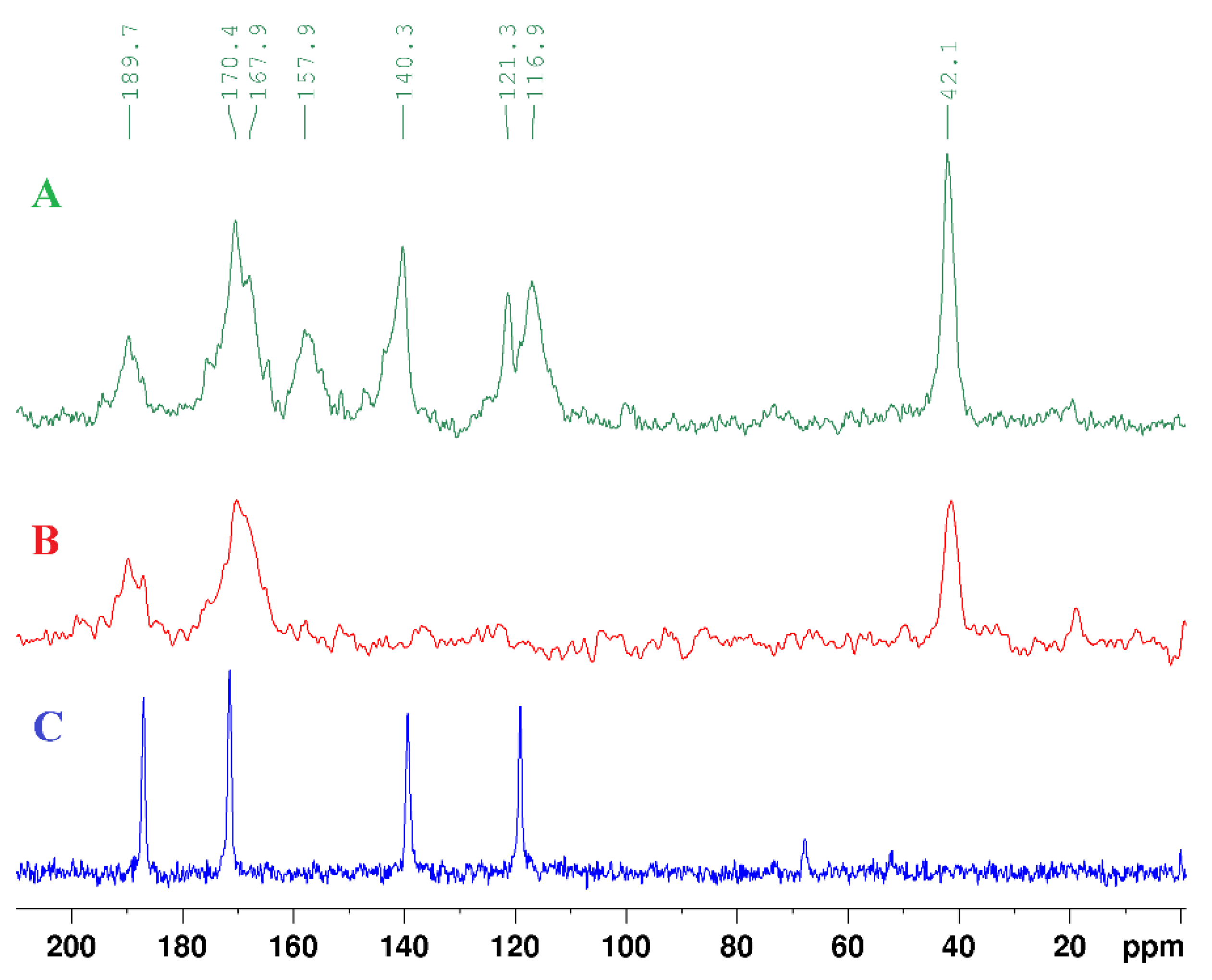

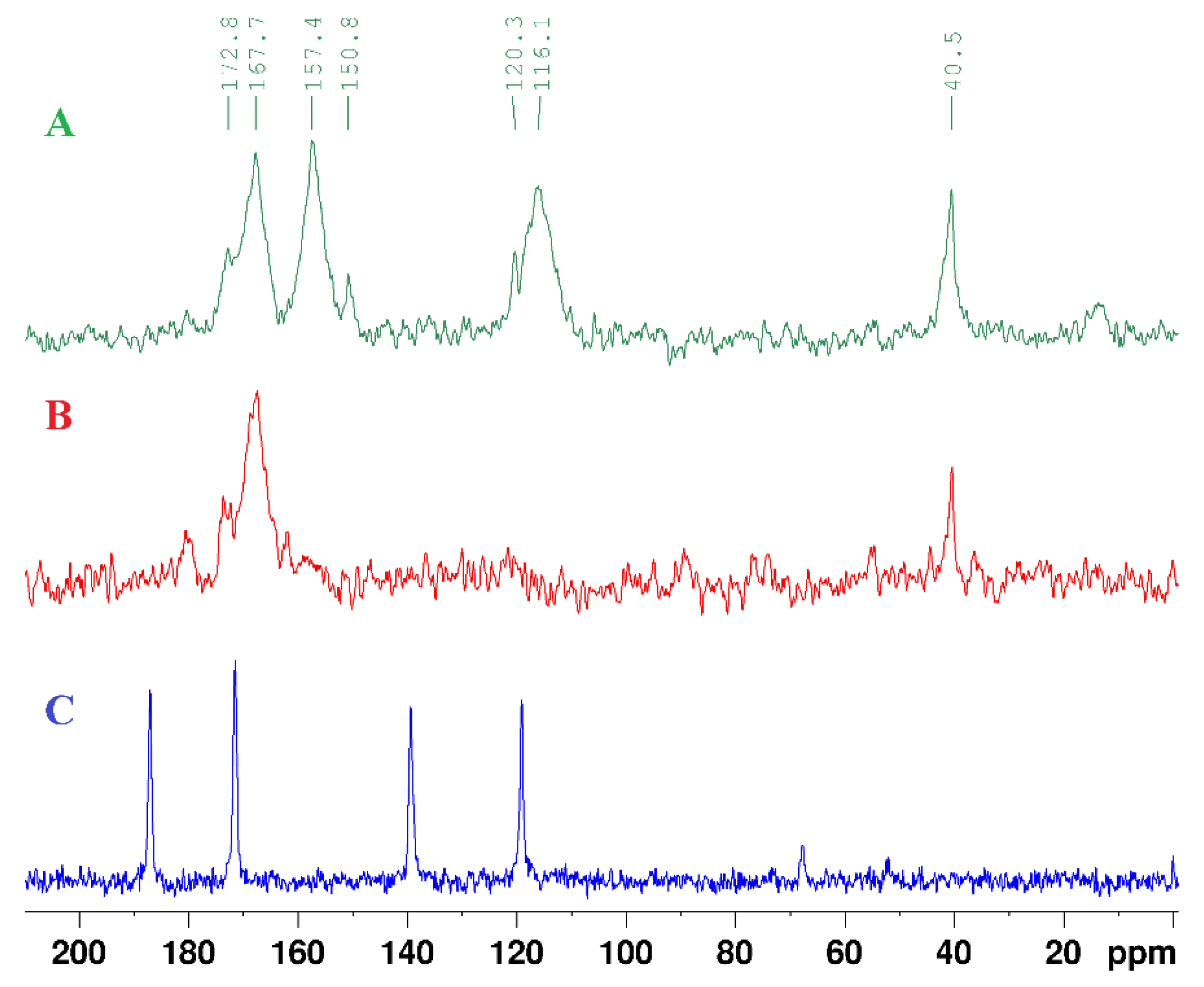

- Burdzhiev, N.; Ahmedova, A.; Borrisov, B.; Graf R. Molecules 2020, 25, 3770-3790. [CrossRef]

- Antonov, V.; Nedyalkova, M.; Tzvetkova, P.; Ahmedova, A. Solid State Structure Prediction Through DFT Calculations and 13C NMR Measurements: Case Study of Spiro-2,4-dithiohydantoins, Z. für. Phys. Chem. 2016, 230, 909–930. [CrossRef]

| technique | donor atom | metal | structure | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C CPMAS NMR, IR and FAB-MS and theoretical DFT studies | N3^S4-bridging coordination | Cu(I) and Ni(II) | dimeric structures | [67] |

| 13C CPMAS NMR and theoretical DFT studies | N3^S2-bridging coordination for L1 with Cu(I); monodentate coordination (N3- and S2- ) of two non-equivalent ligand molecules for L2 with Cu(I); N3^S4- bridging way for Ni(II) |

Cu(I) and Ni(II) | dimeric structure for Cu(I) with L1; square planar for Ni(II) with L1 and L2 |

[68] |

| IR and 13C CPMAS NMR and theoretical DFT studies | N and S | Pt(II) | square planar | [69] |

|

13C-NMR-CP-MAS, EPR, IR and quantum-chemical (DFT/B3LYP-6-31G (d,p)) methods |

N for Cu(II) and N3 and S2 for Ni(II) | Cu(II) and Ni(II) | distorted tetrahedral for Cu(II) and square planar for Ni(II) | [70] |

| 13C CPMAS NMR and theoretical DFT studies, X-ray | O, Cl | Al(III) | six-membered chelate rings | [71] |

| melting point analysis, MP-AES for Cu and Pd, UV-Vis, IR, ATR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and Raman, Solid-state NMR spectroscopy | O,S for L1 and S for L2 with Cu(II); N, S, O with Pd(II) |

Cu(II) and Pd(II) | tetrahedral for Cu(II) with L1 and octahedral for L2; chelate for Pd(II) with L1 and L2 | [72] |

| MP-AES for Cu and Au, ICP-OES for S, ATR, solution and solid-state NMR, and Raman spectroscopy |

N,S for Au(III) and O,S for Cu(II) | Au(III) and Cu(II) | chelate structure | [73] |

| UV-Vis, IR, ATR, 1H NMR, HSQC, and Raman, solid-state NMR spectroscopy | O, S | Au(III) | tetrahedral | [74] |

| IR, FAB-MS, XPS, solid-state NMR spectroscopy and theoretical DFT studies | N, S | Pt(II) | dimer, chelate structure | [75] |

| X-ray | neutral tridentate NNN-chelate | Ni(II) | distorted octahedral geometry |

[82] |

| X-ray | bis-N,O-bidentate Schiff base ligands | Cu(II) | distorted tetrahedral geometry |

[83] |

| X-ray and FT-IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and elemental analysis | tridentate ONO-donor Schiff base ligand | Mo(VI) | distorted octahedral coordination geometry |

[84] |

| X-ray and 1H-, 13C-NMR, IR and UV-Vis spectroscopy and elemental analysis and theoretical DFT studies | O, N | Cu(II), Fe(II) and Zn(II) | chelate structure | [85] |

| X-ray | O, N | Ag(I) | dinuclear complex, chelate structure | [79] |

| X-ray, ESR, MALDI mass-spectrometry, NMR spectroscopy | P, O, P | Ru(II) and Ru(III) | chelate structure | [87] |

| X-ray crystallographic analysis, FTIR, EPR and UV-VIS spectroscopy theoretical DFT studies | O, N | Ni(II) | distorted octahedral coordination geometry |

[80] |

| electrochemical quartz crystal microgravimetry (EQCM) coupled with cyclic voltammetry (CV). |

O, N | Ni(II) | tetrahedral geometry, polymer |

[88] |

| SC-XRD, IR, 1H-, 13C-NMR, TG–MS, X-ray for free ligand |

O, N | Cu(II) | coordination number of Cu(II) is five, polymeric chains | [77] |

| elemental analysis, IR spectroscopy, laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (LDI MS), and X-ray diffraction, theoretical analysis of electronic absorption spectra by the quantum-chemical TD DFT method | O,N | Zn(II) | binuclear complex | [89] |

| technique | compounds | reference |

|---|---|---|

| powder XRD, solid state NMR and calorimetric study | (Csx(CH3NH3)1-x)PbX3 | [94] |

| 13C CP/MAS-NMR spectra | organic matter | [96] |

| CP/MAS 13C-NMR spectroscopy | cellulose I | [97] |

| 13C CP/MAS NMR | Rice Starch | [98] |

| 13C CPMAS NMR, Cross-polarization/polarization-inversion (CPPI), 1H-13C HETCOR MAS NMR spectra | (2-Phenyl-1H-imidazol-4(5)-yl)methanol; (2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1H-imidazol-4(5)-yl)methanol; -(4-(hydroxymethyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)benzonitrile; 2-Phenyl-1H-imidazole-4(5)-carbaldehyde; 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-imidazole-4(5)-carbaldehyde; 4-(4-formyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)benzonitrile; 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1H-imidazole-4(5)-carbaldehyde | [99] |

| 13C CPMAS NMR and theoretical DFT studies | cyclopentanespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoin); cyclohexanespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoin); cycloheptanespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoin); cyclooctanespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoin); 9’-fluorenespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoin) | [100] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).