1. Introduction

Real estate is at the center of contemporary life. This essay focuses on three of these events – the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) triggered by the U.S. mortgage bubble, the COVID-19 pandemic and its urban roots, and the penetration of news techno-economic paradigms into our urban daily lives – to illuminate and unravel the centrality of real estate in our societies.

The land, construction, and real estate sector corresponds to more than half of the global wealth, and only the real estate sector provides 5 to 10% of employment and generates 5 to 15% of GDP in developed countries. At the same time, the environmental impact caused by real estate goods represents about 30% of polluting emissions and 40% of energy consumption globally [

1].

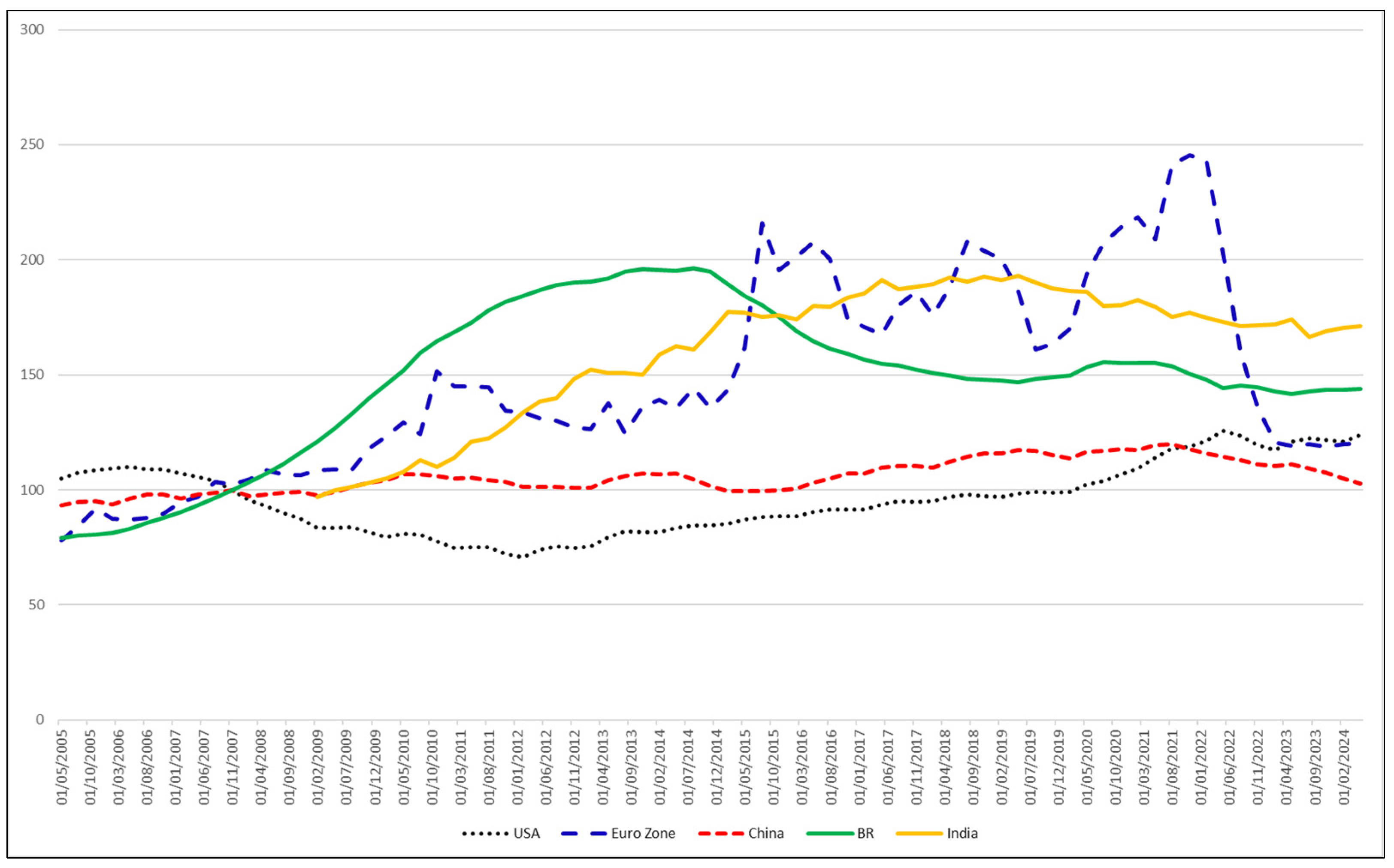

The first two decades of the 21st century saw massive growth in real estate prices across the globe, particularly in emerging or BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa).

Figure 1 depicts this cycle – housing price indexes, all CPI deflated values from 2007’s 2nd quarter to 2024’s 1st quarter – for the three world’s largest economies (US, Euro Zone, China) plus India (fifth largest) and Brazil (seventh largest). It shows a global trend of real estate price uplifts and how it was more pronounced in Brazil and India. China’s housing prices had an almost constant growth up to 2021. It is well-known that real estate is a pillar of the Chinese economy [

2], which, in turn, implies large-scale exports of iron ore from Brazil (and Australia). The massive Chinese urbanization is changing the world’s economy and real estate markets, as one viral statistic showed recently - China used as much cement in two years as the US did over the entire 20th century [

3].

Solid empirical evidence shows that current accounts deficits, real interest rates, and per capita GDP growth are the main drives of real estate appreciation in the OECD countries [

4]. The US housing market suffered the effects of the 2007-2008 crisis, which resulted in a 30% real devaluation until 2012, and after that exhibits a constant growth trend. It only reached December 2007 levels in May 2020. The Euro Zone housing index suffered more from the effect of inflation and that is the main explanation for its volatility. Still, Europe’s housing prices had a significant growth period (2015-2021) after the end of the euro crisis and before the pandemic’s and Ukraine war’s inflations, followed by a sharp real decline after that.

Interestingly, there is cutting-edge evidence showing that real estate is not only a reflection of global economic cycles but acts as a propulsor of these cycles, opening up growth cycles as a key autonomous component of the aggregate demand [

2,

5]. The study of real estate cycles has been of great importance in the real estate literature, although some important research papers in the field have not been updated [

6,

7,

8].

This essay proceeds as follows. First, I detail the relationship between real estate markets and the GFC. Secondly, I present the urban roots of the COVID-19 pandemic and its implications for real estate markets. Then, I explore the interconnection between real estate, cities, and technological revolutions, to finally conclude with some ideas on the frontiers of real estate research.

2. Real Estate and the Global Financial Crisis

First, the acknowledgment of the real estate markets’ role in the GFC is well-known both in academia and in the general public [

1,

2,

9,

10]. Much less attention has been devoted to the causes of it, given that simply blaming low-income households who engaged in subprime mortgages is certainly a misguided explanation. The lack of financial regulation created a tremendous amount of liquidity, and virtually all the American consumers ride the wave of excessive banking lending and securitization, making this crisis as more of a prime, rather than a subprime, borrower issue [

4,

11]. The end of the Glass-Steagall Act in the US in 1999, which was enacted after the 1929 Great Depression to prevent commercial banks from joining investment banks, led to the emergence of financial conglomerates. It created a mass of liquidity that flew to Internet firms’ stocks, later bursting in the 2001 dot.com bubble, which in turn made the Federal Reserve (FED) cut interest rates. Historically low levels of interest rates, securitization, and the heyday of the “Ownership Society” boomed the US housing market [

9,

10,

12].

It is worth noting that the “US housing boom” was indeed geographically concentrated. It took place mostly in the West Coast, New England, and Florida, while Rust Belt cities and the interior markets never boomed in that way [

13]. Similar subnational heterogeneity is reported in the Panic of 1873 and the subsequent Long Depression [

10]. Zhang et al. (2016) [

14] showed that real estate cycles and their determinants vary within mainland China, and Lewis (2023) [

15] brings this same question to Brazil, where Almeida et al. (2022) [

16] have shown that real estate markets are segmented across the urban hierarchy.

More importantly, though, is that the knowledge on real estate must be consolidated about the lessons the world could learn from this crisis [

17]. The pervasive effects of the GFC damaged our economies, jobs, and homes, and opened the doors to fiscal austerity and several extremist political leaderships in the ten years of its aftermath [

5,

18]. The literature points to the necessity of more regulation, combat speculation, and solid housing financial institutions to prevent future real estate bubbles and their contagion effects on the entire economy.

Some structural characteristics of the US society and real estate markets seem to be crisis-prone. It is staggering the number of real estate crises the US had in the last two centuries, from the railroad and gold rush booms and their associated land speculation crisis to the recent GFC [

7,

10]. Chicago had a well-described real estate bubble in the 1830s, during which time the per acre prices (in current US dollars) in the future Chicago Loop increased from

$800 in 1830 to

$327,000 in 1836, before falling to

$38,000 per acre by 1841. Perhaps due to this American characteristic, the US researchers developed really long-run time series to account for real estate price variations, such as the classical Homer Hoyt’s (1933) [

6] thesis published in 1933 – “One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago” –, and the Nobel Prize-winner Robert Shiller [

9], who built a national housing index beginning in 1890.

Kaiser (1997) [

7] offers a deep study of the long cycle in real estate, based on historical data from the US commercial and housing markets. He concluded that prior to the real estate boom, there is an unusually large spike in inflation, which triggers an initially rapid rise in net operating income. According to him, rising incomes and rising prices attract a large amount of investment capital, resulting in a disastrously large overdevelopment boom. Resulting vacancy problems drive net operating incomes back down to levels approximating those prior to the boom. Nonetheless, he cites Hoyt’s mature work (1960), in which the expert had said the real estate cycles are a result of the optimism and depression of masses of people rather than inflationary shocks.

Finally, literature has increasingly recognized the role of cycles in real estate, including their psychological, irrational, and “conventional” (as post-Keynesian economics puts it) determinants [

9,

19,

20]. This recognition brings a serious barrier to real estate valuation since much of the price variation is not explained by “market fundamentals” but by cyclic variables [

21]. Interesting hypotheses have been raised in the face of these challenges to real estate appraisal [

22]. The ship of the real estate appraisal might be losing its anchor – it means, suffering a disruption.

2. Real Estate and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Second, there is cutting-edge research showing that the COVID-19 pandemic has its roots in the extended urbanization process [

6] [

23], a term coined [

7] [

24] to describe the process by which a city expands its tentacles to far-reaching regions, increasing the connectivity of cities, its hinterlands, and the global urban network. Allegedly, the SARS-CoV-2 virus crossed the animal-human divide at a seafood market in Wuhan, a Chinese metropolis and a major transportation node with national and international connections. The emergence of COVID-19, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and H1N1 suggests that zoonotic pathogen transmission is a hallmark of 21st-century urbanization and globalization.

Commercial real estate and massive suburbanization are closely related to it. After the COVID-19 outbreak, real estate sat in the spotlight once again. The public health calls for “stay at home” contrasts with the reality of those who do not have a home (housing affordability crisis). Home-office work became a global trend and those who had means hid themselves far from agglomerations in countryside second residences. All these changes made significant impacts on real estate demand across the globe.

During the pandemic, governments responded to it by using fiscal policy (e.g., Corona vouchers) and monetary policy (cuts in basic interest rates). These policies led to real estate market reactions, as they have positive impacts on real estate prices. The “cheap money” years of COVID-19 provided considerable stimulus to real estate, as

Figure 1 suggests.

After the pandemic, a supposedly “new normal” emerged, an expression that curiously was popularized by Bill Gross (PIMCO) in 2009 to describe the aftermath of the GFC [

9]. Many workers are still working remotely, and many in-person activities have been substituted by online alternatives. These trends have spread the demand for housing away from metropolises with high-level rents and congestion, emptied commercial real estate in city centers, and boomed warehouses of Internet shopping companies.

4. Real Estate and Technological Revolutions

Each Industrial Revolution requires a set of specific infrastructures and types of external economies, which are provided by cities, implying the emergence of new paradigmatic cities. In this sense, there was “Manufacturing cities” at the 19th century, “Fordist cities” at the 20th century, and now we see the emergence of a third wave of urbanization, with global-city regions and smart-cities, characterized by ‘knowledge economy’. This argument contains a bidirectional causal relationship between innovations and cities. In one direction, Technological Revolutions gradually lead cities to adapt to the demands of new technologies [

8]. New firms and sectors emerge, and even the

modus operandi of firms previously established in the markets are affected. The structure of demand is also affected, either with the emergence of new products or with new forms of consumption of products that already existed previously. On the other side of the causal relationship, for a Technological Revolution to occur and spread, a set of requirements is necessary that only cities can offer – interaction, dissemination of knowledge, transport infrastructure, housing, and sanitation, among others. Furthermore, innovation takes place in the city, depending fundamentally on the set of social relations and knowledge exchanges that are established in the territory – cross-fertilization of ideas, as Jane Jacobs wrote [

9,

10,

11,

25,

26,

27].

Thence, the techno-economic paradigms of information and communication technologies, and Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Big Data, robotics, and automation emerged through the frequent interaction of researchers that can only take place in cities and their built environment and, at the same time, are reshaping cities and their real estate stock. Platform firms such as Amazon, Uber, and delivery apps have changed the way consumers access markets, having deep impacts on centrally located commercial real estate and warehouses. Internet broadband has paved the way for remote working and has fed the search for housing in amenity rich places far from the polluted and expensive central cities. Airbnb obviously has been changing hoteling and lifting local dwellers’ concerns about touristic sites. All these changes rely on the real estate market’s functioning. At the same time, they are disrupting the way real estate markets operate.

5. Conclusions

This short essay aimed to address some key events of the world’s contemporary lives. Namely, the GFC, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the emergence of new techno-economic paradigms affect mankind in a way that does not allow come backs. In all these events, real estate is at the center of the transformations.

Real estate literature may benefit from the many research avenues this paper mentions. The careful study of real estate cycles and its relationships with the macroeconomic cycles is worth paying great attention to. Detailing real estate cycles in subnational and intra-urban is still a task to be further developed. The novelty of the COVID-19 pandemic still requires much more research to understand its impacts on housing conditions, commercial real estate vacancies, and economic opportunities. In the other way around, the study of real estate markets’ behavior and the urbanization processes is relevant to produce public health guidance to prevent the emergence of pandemics, and to avoid pandemics dispersion. Finally, Industry 4.0 and the emergence of new city-forms, such as the smart-city, will certainly attract much attention in the coming years.

Beyond these keys events, real estate literature is starting to address climate change [

28,

29,

30]. Climate change certainly affects real estate appraisal, by affecting both amenities and expectations on the future. In turn, “Green land tax” depends on reassessments on land value [

31]. More importantly, real estate literature must consider progressive proposals, housing affordability, intergenerational equity, and regional justice.

Funding

The author are grateful the Nacional Council for Scientific Research (Cnpq) – Universal Demand Grant 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- De Paola, P. Real Estate: Discovering the Developments in the Real Estate Sector Using the Current Research Challenges. Real Estate 2023, 1, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.X.; Zhan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Pan, W. How big is China’s real estate bubble and why hasn’t it burst yet?. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 153–162. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H. China Uses as Much Cement in Two Years as the US Did over the Entire 20th Century. Sustainability by Numbers 2023. Available at: https://www.sustainabilitybynumbers.com/p/china-us-cement (Accessed on 11/07/2024).

- Aizenman, J.; Jinjarak, Y. Current account patterns and national real estate markets. J. Urban Econ. 2009, 66, 75–89. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Montiel, J.A.; Pariboni, R. Housing is NOT ONLY the Business Cycle: A Luxemburg-Kalecki External Market Empirical Investigation for the United States. Rev. Politi- Econ. 2022, 34, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Quaife, M.M.; Hoyt, H. One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago: The Relationship of the Growth of Chicago to the Rise in Its Land Values, 1830-1933. Miss. Val. Hist. Rev. 1934, 21, 108–108. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R. The Long Cycle in Real Estate. J. Real Estate Res. 1997, 14, 233–257. [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, W.C. Real Estate “Cycles”: Some Fundamentals. Real Estate Econ. 1999, 27, 209–230. [CrossRef]

- Shiller, R.J. Irrational Exuberance; 3rd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey, 2014.

- Edelstein, M.D.; Edelstein, R.H. Crashes, Contagion, Cygnus, and Complexities: Global Economic Crises and Real Estate. International Real Estate Review 2020, 23, 311–336.

- Ferreira, F.; Gyourko, J. A New Look at the U.S. Foreclosure Crisis: Panel Data Evidence of Prime and Subprime Borrowers from 1997 to 2012; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, 2015; p. w21261.

- Brandão, M. de B. Ensaios Sobre Capital Fictício, Renda Da Terra e Financeirização No Brasil. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Centro de Desenvolvimento e Planejamento Regional: Belo Horizonte, 2022.

- DeFusco, A.; Ding, W.; Ferreira, F.; Gyourko, J. The role of price spillovers in the American housing boom. J. Urban Econ. 2018, 108, 72–84. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Hui, E.C.-M.; Li, V. Comparisons of the relations between housing prices and the macroeconomy in China’s first-, second- and third-tier cities. Habitat Int. 2016, 57, 24–42. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. Ciclo Macroeconômico e Dinâmica Imobiliária: Uma Análise Comparativa Entre o Local e o Nacional Entre 2009-2020. Undergraduate monograph, Universidade Federal de São João del Rei: São João del Rei, 2023.

- Almeida, R.P.; Amano, F.H.F.; Tupy, I.S. Real estate markets and urban networks in Brazil. Rev. Bras. de Estud. Urbanos e Reg. 2022, 24, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, P. Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown; 1st ed.; Verso: London; New York, 2013.

- Theodore, N. Governing through austerity: (Il)logics of neoliberal urbanism after the global financial crisis. J. Urban Aff. 2020, 42, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Abramo, P. A Cidade Caleidoscópica: Coordenação Espacial e Convenção Urbana: Uma Perspectiva Heterodoxa Para a Economia Urbana; 1st ed.; Bertrand do Brasil: Rio de Janeiro, 2007.

- Abramo, P. Le marché, l’ordre-désordre et la coodination spatiale: I’incertitude et la convention urbaines. Ph.D. Dissertation, Ecole des Haustes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS): Paris, 1994.

- Almeida, R.; Brandão, M.; Torres, R.; Patrício, P.; Amaral, P. An assessment of the impacts of large-scale urban projects on land values: The case of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2020, 100, 517–560. [CrossRef]

- Morano, P.; Salvo, F.; De Ruggiero, M.; Tajani, F.; Tavano, D. Oligopsony Hypothesis in the Real Estate Market. Supply Fragmentation and Demand Reduction in the Economic Crisis. In Science of Valuations: Natural Structures, Technological Infrastructures, Cultural Superstructures; Giuffrida, S., Trovato, M.R., Rosato, P., Fattinnanzi, E., Oppio, A., Chiodo, S., Eds.; Green Energy and Technology; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024 ISBN 978-3-031-53708-0.

- Connolly, C.; Ali, S.H.; Keil, R. On the relationships between COVID-19 and extended urbanization. Dialog- Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 213–216. [CrossRef]

- Monte-Mór, R.L. What is the urban in the contemporary world?. Cad. de Saude publica 2005, 21, 942–948. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Economy of Cities; Random House: New York, 1969.

- Storper, M. Keys to the City; Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey, 2013; ISBN 978-0-691-14311-8.

- Scott, A.; Storper, M. Regions, Globalization, Development. Reg. Stud. 2003, 37, 579–593. [CrossRef]

- Drumond, R.A.S.; Almeida, R.P.; Nascimento, N.d.O. Climate change and Master Plan: flood mitigation in Belo Horizonte. 2023, 25, 899–922. [CrossRef]

- Kiel, K.A. Climate Change Adaptation and Property Values: A Survey of the Literature. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Papers Series 2021, 33.

- Nascimento, N. Using Green and Blue Infrastructure for Urban Flood Mitigation: Simulating Scenarios for Climate Change, GBI Technologies, and Land Policy. 84.

- OECD; Korea Institute of Public Finance Bricks, Taxes and Spending: Solutions for Housing Equity across Levels of Government; Dougherty, S., Kim, H.-A., Eds.; OECD Fiscal Federalism Studies; OECD, 2023; ISBN 978-92-64-73536-1.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).