Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Body Composition and Physiological Demands and Performance-Related Variables

2.2.3. Laboratory Tests

2.2.4. On-Field Tests

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Someren, K.A.; Phillips, G.R.; Palmer, G.S. Comparison of physiological responses to open water kayaking and kayak ergometry. Int J Sports Med. 2000, 21, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielik V, Lendvorsky, Vadja M et al.. Comparison of aerobic and muscular power between Junior /U23 slalom and sprint paddlers: an analysis of international medallists and non-medallists. Front Physiol. 2021 11:617041. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues dos Santos, J.A.; Sousa, R.F.S.; Amorim, T.P. Comparison of treadmill and kayak ergometer protocols for evaluating Peak Oxygen Consumption. TOSSJ. 2012, 5, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues dos Santos, J.A.; Viana da Silva, A. Correlation between strength and kayaking performance in water. J Sport Health Res. 2010, 2, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Durnin, J.V.; Womersley, J. Body fat assessment from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: measurements on 481 men and women aged 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr. 1974, 32, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, WE. Body composition from fluid spaces and density: analysis of methods. In: J Brozek & A Henschel (eds). Techniques for Measuring Body Composition. Washington DC: National Academy of Sciences. 1961. pp:223-244.

- Protzner, A.; Szmodis, M.; Udvardy, A.; et al. Hormonal neuroendocrine and vasoconstrictor peptide responses of ball game and cyclic sport elite athletes by treadmill test. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0144691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galán-Rioja, M.A.; González-Mohíno, F.; Danders, D.; Mellado, J.; González-Ravé, J.M. Effects of body weight vs. Lean body mass son Wingate Anaerobic Test performance in endurance athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2020, 41, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues dos Santos, JA. Physiological, anthropometric, and motor comparative study between footballers of different competitive levels and sprinters, middle-distance runners and long-distance runners. PhD final thesis. 1995. Faculty of Sport. University of Porto. Portugal (Thesis in Portuguese).

- Someren, K.A.; Howatson, G. Prediction of flatwater kayaking performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2008, 3, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, C.W.; Nosaka, K.; Zois, J.; et al. Maximal upper-body strength and oxygen uptake are associated with performance in high-level 200-m sprint kayakers. J Strength Cond Res. 2018, 32, 3186–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglione, A.; Lazzer, S.; Colli, R.; Introini, E.; Di Prampero, P.E. Energetics of best performance in elite kayakers and canoeists. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues dos Santos, J.A.; Affonso, H.O.; Boullosa, D.; Pereira, T.M.C.; Fernandes, R.J. Conceição F. Extreme blood lactate rising after very short efforts in top-level track and field male sprinters. Res Sports Med. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamparo, P.; Tomadini, S.; Didonè, F.; Grazzina, F.; Rejc, E.; Capelli, C. Bioenergetics of a slalom kayak (K1) competition. Int J Sports Med. 2006, 27, 546.552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacour, J.R.; Bouvat, E.; Barthélémy, J.C. Post-competition blood lactate concentrations as indicators of anaerobic energy expenditure during 400-m and 800-m races. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1990, 61, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Niessen, M.; Chen, X.; Hartmann, U. Maximal lactate steady state in kayaking. Int J Sports Med. 2014, 35, 939–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, P.; Bhammar, D.M.; Babb, T.G.; Bowen, T.S.; Witte, K.K.; Rossiter, H.B.; Brugniaux, J.V.; Perry, B.D.; Dantas de Lucas, R.; Turnes, T.; Sabino-Carvalho, J.L.; Lopes, T.R.; Zacca, R.; Fernandes, R.J.; McKie, G.L.; Hazell, T.J.; Helal, L.; da Silveira, A.D.; McNulty, C.R.; Roberg, R.A.; Nightingale, T.E.; Alrashidi, A.A.; Mashkovskiy, E.; Krassioukov, A.; Clos, P.; Laroche, D.; Pageaux, B.; Poole, D.C.; Jones, A.M.; Schaun, G.Z.; de Souza, D.S.; de Oliveira Barreto Lopes, T.; Vagula, M.; Zuo, L.; Zhao, T. Commentaries on Viewpoint: V̇o2peak is an acceptable estimate of cardiorespiratory fitness but not V̇o2max. J Appl Physiol (1985). Erratum in: J Appl Physiol (1985). 2018, 125, 970. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.zdg-2795-corr.2018. 2018, 125, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean ± SD | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 23.1 ± 5.6 | 19.3 to 27.0 |

| Body Weight (Kg) | 80.0 ± 8.8 | 73.9 to 86.1 |

| Height (cm) | 177.0 ± 6.9 | 172.2 to 181.8 |

| Arm span (cm) | 183.4 ± 7.4 | 178.3 to 188.5 |

| Data are presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) | ||

| SESSIONS | DAYS OF WEEK | ||||||

| MONDAY | TUESDAY | WEDNESDAY | THURSDAY | FRIDAY | SATURDAY | SUNDAY | |

| Morning Session |

Kayaking 12 km SPM: 60 |

Kayaking 30’ Recovery: 3min SPM: 65 |

Kayaking 14 km SPM: 60 |

Cycling 1h45min |

Kayaking 14 km SPM: 60 |

Kayaking 16 km SPM: 65 |

Cycling 1h45 |

| Morning session volume and intensity description | |||||||

|

Volume (km) |

12 | 15 | 14 | - | 14 | 16 | - |

|

Intensity (km SPM) |

720 | 975 | 840 | - | 840 | 1040 | - |

| Afternoon Session |

Strength ) 12 exercises 25 maximal repetitions Recovery: 3min + Running: 40min |

Swimming 500m Recovery: 2 min |

Strength 6 exercises 12 maximal repetitions 7 sets + Core Exercises |

Rest |

Strength Identical to Monday |

Swimming 500m Recovery: 2min |

Rest |

| Afternoon volume and intensity description | |||||||

|

Volume (km) |

- | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | - |

|

Intensity (km SPM) |

- | 130 | - | - | - | 130 | - |

| Total daily and weekly volume and intensity | |||||||

|

Total Volume per day (km) |

12 | 17 | 14 | - | 14 | 18 | - |

|

Total intensity per day (km SPM) |

720 | 1105 | 840 | - | 840 | 1170 | - |

|

Total Volume per week (km) |

75 | ||||||

|

Total intensity per week (km SPM) |

4675 | ||||||

| SPM: Strokes per minute; -: not applicable All training sessions end with 15’ of passive stretching | |||||||

| SESSIONS | DAYS OF WEEK | ||||||

| MONDAY | TUESDAY | WEDNESDAY | THURSDAY | FRIDAY | SATURDAY | SUNDAY | |

| Morning Session |

Kayaking 18km + 62km Recovery: 3min SPM: 75-80 |

Kayaking 18km SPM: 70-75 |

Kayaking 16km + 61.5km SPM: 0.5km: 75 0.5km: 80 0.5km: 85 … |

Kayaking 12km SPM:65 + 615s Recovery: 1min45s SPM: 120 Boat in movement |

Kayaking 18km + 91.25km Recovery:3min SPM: 100m – 75 250m – 85 … |

Kayaking 18km SPM: 70-75 |

Kayaking 12km SPM: 65 or Cycling 1h10min |

| Morning session volume and intensity description | |||||||

|

Volume (km) |

30 | 18 | 25 | 12 | 29.25 | 18 | 12 |

|

Intensity (km SPM) |

2250 | 1350 | 2000 | 780 | 2340.75 | 1350 | 780 |

| Afternoon Session |

Strength 7 Sets 6 exercises 8 maximal repetitions + Core Exercises |

Kayaking 12km SPM: 65 + Running: 40min |

Strength 5 sets 12 exercises 20 maximal repetitions Recovery: 2 min + Core Exercises |

Rest |

Strength 12km Identical to Monday |

Kayaking 12km SPM: 65 + Running: 40min |

Rest |

| Afternoon volume and intensity description | |||||||

|

Volume (km) |

- | 12 | - | - | - | 12 | - |

|

Intensity (km SPM) |

- | 780 | - | - | - | 780 | - |

| Total daily and weekly volume and intensity | |||||||

|

Total Volume per day (km) |

30 | 30 | 25 | 12 | 29.25 | 30 | 12 |

|

Total intensity per day (km SPM) |

2250 | 2130 | 2000 | 780 | 2340.75 | 2130 | 780 |

|

Total Volume per week (km) |

168.25 | ||||||

|

Total intensity per week (km SPM) |

12410.75 | ||||||

| SPM: Strokes per minute; -: not applicable All training sessions end with 15’ of passive stretching | |||||||

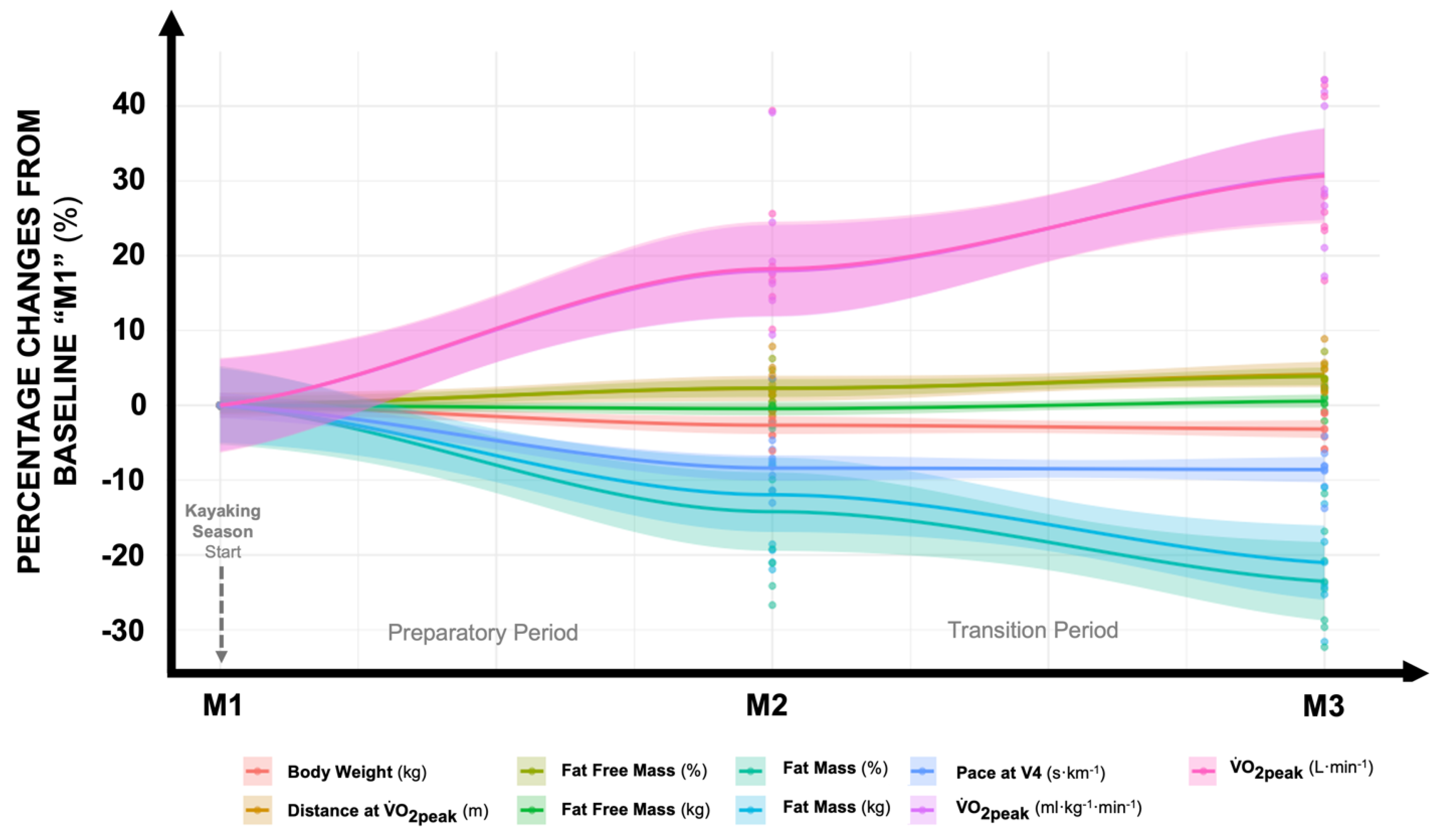

| VARIABLE | M1 | M2 | M3 | TRAINING EFFECT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 VS M2 | M1 VS M3 | M2 VS M3 | ||||

| BODY COMPOSITION | ||||||

| Body weight (kg) | 80.1 (73.2; 87.0) |

77.8 (70.9; 84.7) |

77.2 (70.3; 84.1) |

-2.3 (-3.3; -1.2) p = 0.002; d = -0.27 |

-2.9 (-4.0; -1.7) p < 0.001; d = -0.35 |

-0.6 (-1.7; 0.49) p = 0.881; d = -0.07 |

| Body density | 1.09 (1.07; 1.10) |

1.10 (1.08; 1.12) |

1.10 (1.08; 1.11) |

0.01 (-0.01; 0.03) p = 0.731; d = 0.47 |

0.01 (-0.01; 0.03) p = 0.765; d = 0.56 |

0.0 (-0.02; 0.02) p = 1.000; d = 0.00 |

| Fat Mass (%) | 15.5 (12.7; 18.2) |

13.6 (10.9; 16.4) |

12.4 (9.6; 15.1) |

-1.8 (-2.8; -0.9) p = 0.005; d = -0.58 |

-3.1 (-4.1; -2.1) p < 0.001; d = -0.94 |

-1.2 (-2.2; -0.3) p = 0.065; d = -0.36 |

| Fat Mass (kg) | 12.5 (9.9; 15.1) |

10.7 (8.1; 13.3) |

9.6 (7.0; 12.2) |

-1.8 (-2.8; -0.9) p = 0.006; d = -0.58 |

-2.9 (-3.9; -2.0) p < 0.001; d = -0.94 |

-1.1 (-2.0; -0.1) p = 0.124; d = 0.80 |

| Fat Free Mass (kg) | 67.6 (62.0; 73.2) |

67.2 (61.6; 72.8) |

67.6 (62.1; 73.2) |

-0.4 (-1.1; 0.3) p = 0.718; d = -0.06 |

0.04 (-0.7; 0.8) p = 1.000, d = 0.00 |

0.46 (-0.3; 1.2) p = 0.696; d = 0.06 |

| Fat Free Mass (%) | 84.5 (81.8; 87.3) |

86.4 (83.6; 89.1) |

87.6 (84.9; 90.4) |

1.9 (0.9; 2.8) p = 0.005; d = 0.58 |

3.1 (2.1; 4.1) p < 0.001; d = 0.94 |

1.2 (0.3; 2.2) p = 0.065; d = 0.36 |

| LABORATORY TEST (4-MIN ALL-OUT) | ||||||

| (L·min-1) | 3.9 (3.4; 4.3) |

4.5 (4.1; 5.0) |

5.0 (4.5; 5.4) |

0.7 (0.5; 0.9) p < 0.001; d = 1.11 |

1.1 (0.9; 1.4) p < 0.001; d = 2.04 |

0.5 (0.3; 0.7) p = 0.001; d = 0.93 |

| (ml·kg-1·min-1) | 49.9 (45.5; 54.2) |

58.5 (54.1; 62.9) |

64.9 (60.5; 69.2) |

8.6 (6.0; 11.3) p < 0.001; d = 1.64 |

15.0 (12.4; 17.8) p < 0.001; d = 2.88 |

6.4 (3.7; 9.1) p = 0.001; d = 1.22 |

| Distance at (m) | 939.7 (908.3; 971.2) |

959.7 (928.3; 991.2) |

976.4 (945.0; 1007.9) |

20.0 (3.4; 36.6) p = 0.099; d = 0.53 |

36.7 (19.9; 53.5) p = 0.002; d = 0.98 |

16.7 (0.0; 33.4) p = 0.209; d = 0.44 |

| [La-]peak (mmol·L-1) | 12.7 (10.8; 14.5) |

12.1 (10.2; 14.0) |

11.4 (9.5 13.3) |

0.6 (-0.41; 1.53) p = 0.830; d = 4.65 |

1.3 (0.29; 2.25) p = 0.070; d = 4.33 |

0.7 (-0.27; 1.68) p = 0.530; d = -0.31 |

| HR at (bpm) | 182.8 (174.4; 191.1) |

181.8 (173.5; 190.2) |

180.3 (171.9; 188.7) |

-0.9 (-4.5; 2.6) p = 1.000; d = -0.10 |

-2.5 (-6.1; 1.2) p = 0.610; d = -0.25 |

-1.5 (-5.1; 2.1) p = 1.000; d = -0.15 |

| ON-FIELD TEST (4×1500-M INCREMENTAL) | ||||||

| HR at V4 (bpm) | 158.3 (149.4; 167.2) |

164.3 (155.5; 173.2) |

162.7 (153.9; 171.6) |

6.0 (-1.7; 13.8) p = 0.445; d = 0.57 |

4.4 (-3.4; 12.2) p = 0.850; d = 0.41 |

-1.6 (-9.4; 6.1) p = 1.000; d = -0.15 |

| Pace at V4 (s·km-1) | 297.8 (285.5; 310.1) |

272.6 (260.3; 284.9) |

272.3 (259.9; 284.6) |

-25.2 (-31.2; -19.2) p < 0.001; d = -1.71 |

-25.6 (-31.6; 5.7) p < 0.001; d = -1.73 |

-0.4 (-6.4; 5.7) p = 1.000; d = -0.02 |

|

Notes: Data are presented as EMm and 95%CI. The treatment effect are presented as estimated mean difference (EMD) and 95%CI. Abbreviation: Moment 1 (M1); Moment 2 (M2); Moment 3 (M3); Heart rate (HR); | ||||||

| VARIABLE | M1 | M2 | M3 | TRAINING EFFECT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 VS M2 | M1 VS M3 | M2 VS M3 | ||||

| Tricipital (mm) | 8.7 (5.9; 11.5) |

9.5 (6.7; 12.3) |

8.8 (6.0; 11.6) |

0.8 (-0.1; 1.6) p = 0.299; d = 0.24 |

0.1 (-0.8; 1.0) p = 1.000; d = 0.03 |

-0.7 (-1.6; 0.2) p = 0.415; d = -0.21 |

| Subscapular (mm) | 9.5 (8.2; 11.0) |

8.7 (7.3; 10.1) |

8.9 (7.5; 10.3) |

-0.9 (-1.3; -0.4) p = 0.007; d = -0.48 |

-0.7 (-1.1; -0.2) p = 0.036; d = -0.36 |

0.2 (-0.3; 0.6) p = 1.000; d = 0.12 |

| Bicipital (mm) | 5.5 (4.3; 6.8) |

3.9 (2.6; 5.1) |

3.8 (2.6; 5.1) |

-1.6 (-2.9; 0.3) p = 0.077; d = -1.07 |

-1.7 (-3.0; -0.4) p = 0.064; d =-1.14 |

-0.1 (-0.5; 0.4) p = 1.000; d = -0.07 |

| Suprailiac (mm) | 15.6 (11.7; 19.4) |

11.2 (7.3; 15.0) |

8.4 (4.6; 12.3) |

-4.4 (-7.2; -1.6) p = 0.025; d = -31.44 |

-7.1 (-10.0; -4.3) p < 0.001; d = -32.05 |

-2.7 (-5.6; 0.1) p = 0.238; d = -0.61 |

| Supraspinal (mm) | 11.2 (8.2; 14.3) |

8.8 (5.6; 11.8) |

10.5 (7.5; 13.6) |

-2.4 (-5.4; 0.6) p = 0.408; d = -0.65 |

-0.7 (-.37; 2.3) p = 1.000; d = -0.19 |

1.7 (-1.3; 4.7) p = 0.842; p = 0.46 |

| Abdominal (mm) | 15.7 (10.7; 20.8) |

12.7 (7.6; 17.8) |

11.5 (6.4; 16.5) |

-3.0 (-4.6; -1.5) p = 0.005; d = -0.49 |

-4.3 (-5.9; -2.7) p < 0.001; d = -0.78 |

-1.3 (-2.8; 0.3) p = 0.411; d = -0.28 |

| Crural (mm) | 15.5 (10.7; 20.4) |

13.8 (8.9; 18.6) |

12.8 (7.9; 17.7) |

-1.8 (-3.3; -0.3) p = 0.105; d = -0.29 |

-2.7 (-4.3; -1.2) p = 0.009; d = -0.46 |

-1.0 (-2.5; 0.6) p = 0.705; d = -0.17 |

| Geminal (mm) | 8.7 (4.6; 12.9) |

7.3 (3.1; 11.4) |

7.4 (3.3; 11.5) |

-1.5 (-2.5; -0.5) p = 0.036; d = -0.28 |

-1.3 (-2.4; -0.3) p = 0.075; d = -0.26 |

0.2 (-1.4; 1.7) p = 1.000; d = 0.02 |

|

Notes: Data are presented as estimated marginal means (Emm) and 95%CI. The treatment effect are presented as estimated mean difference (EMD) and 95%CI. Abbreviation: Moment 1 (M1); Moment 2 (M2); Moment 3 (M3); | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).