1. Introduction

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health disorders that affect people globally. Long-term depression occurs in approximately 5% of the population, while generalized anxiety occurs in approximately 3-4%. Shorter episodes of the above-mentioned disorders occur in several times higher percentages of people [1-3].

Patients who struggle with degenerative diseases of the joints and tendons and the resulting challenges of pain and mobility impairment are particularly susceptible to the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety [

4]. Injury to the musculoskeletal system is an important factor influencing the level of stress, as well as the severity of depressive disorders [5-7].

Symptoms of depression, in turn, may significantly affect the deterioration of functional results and satisfaction in patients after surgical treatment, although the research results are not clear [8-13]. Yet from another point of view, physical fitness and activity is a known factor that reduces stress and symptoms of depression [

14,

15].

For abovementioned reasons, in the practice of both orthopedic departments and clinics, awareness of the occurrence of depression and generalized anxiety disorder in patients is crucial for optimizing the results and cost-effectiveness of treatment. Despite the universality of the problem, the number of studies describing the frequency and factors influencing the mental state of patients with musculoskeletal disorders seems to be insufficient.

The study aims to provide information on what is the incidence of depressive and anxiety disorders in orthopedic patients and what are the characteristics of orthopedic patients regarding depressive disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

Study was performed over a 12 month period and covered 336 patients that were electively admitted and operated on at the Orthopedic Department of University Clinical Centre in Gdańsk and gave the consent for the study. As the study involved just retrospective medical data of commonly used surveys there was no requirement for the consent of the local Ethical Committee

Patients with multiple organ injuries and severe trauma were excluded from the study due to the possibility of obtaining inadequate answers caused by a sudden and significant change in their life situation. Patients with dementia or mental disability that prevented them from completing the survey on their own were also excluded, as well as those who refused to undergo the examination. Patients were not assisted in filling the questionnaires as they were designed for self-completion. The assessment involved the results of commonly recognized screening forms for depression (PHQ-9) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD-7) [3, 16-18]. The surveys also included questions about depression treatment, type of medications taken, and the level of pain determined by VAS, BMI score as well as site of operation, distinguishing foot and ankle (F&A), lower leg, knee, thigh, hip, pelvis, shoulder, arm, elbow, forearm, hand and wrist (H&W).

The PHQ-9 form consists of 9 questions that determine the severity of depressive symptoms over the last two weeks with a score from 0 to 3 points each. A total score of 10 or more allows for the diagnosis of a moderate depression episode, from 15 to 19 points - moderately severe, and 20 or more indicates severe depression episode. In some studies, with a score of 5 to 9 points, a mild depression episode is also distinguished. The GAD-7 form contains 7 questions that assess the severity of anxiety symptoms on a scale from 0 to 3 points each. A total score of 10 or more indicates features of generalized anxiety disorder. If at least 10 points were obtained on any of the forms, patients were informed about the indications for consulting with a mental health or psychology specialist. The surveys also included pain assessment with VAS from 0 to 10 points.

3. Results

3.1. General Figures

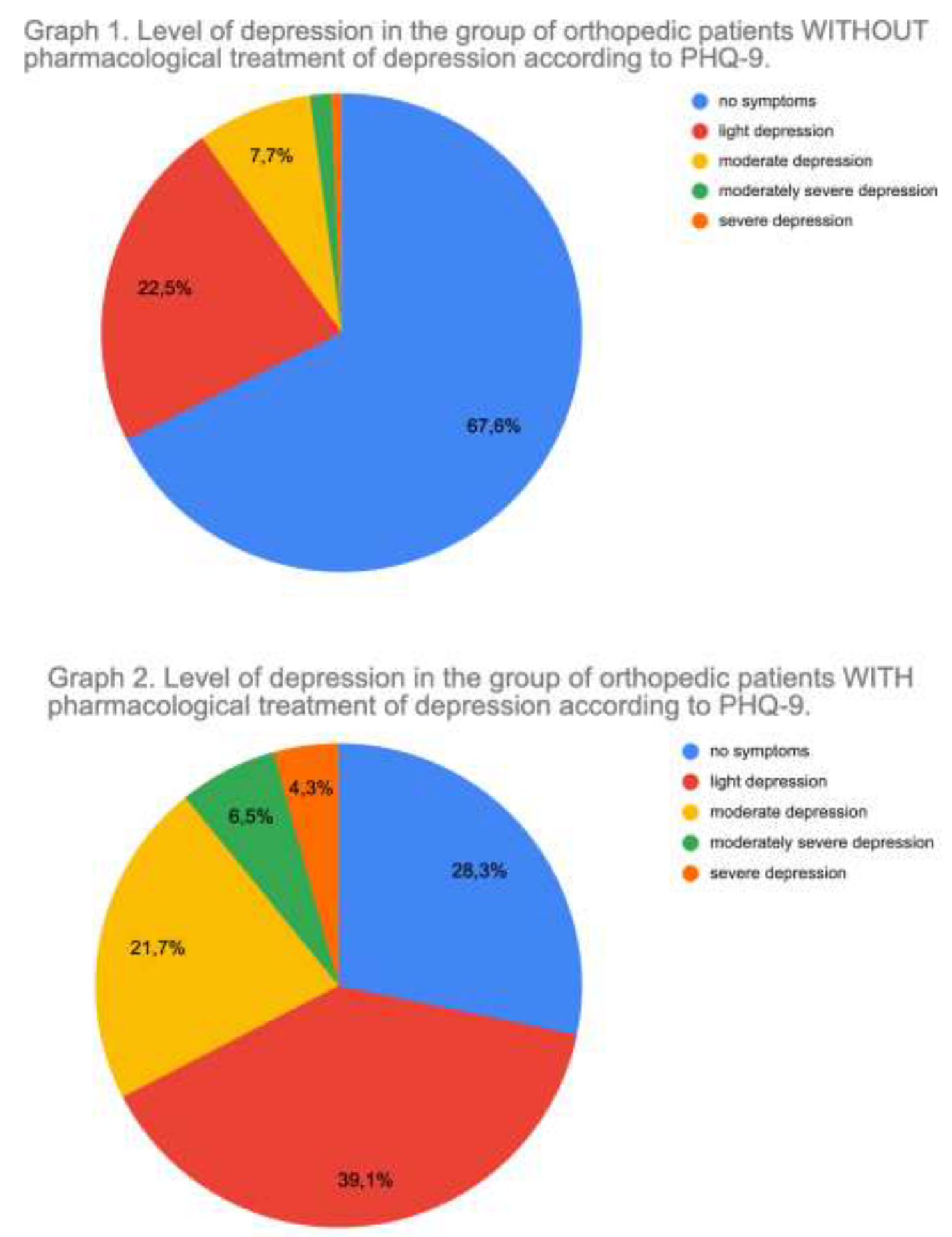

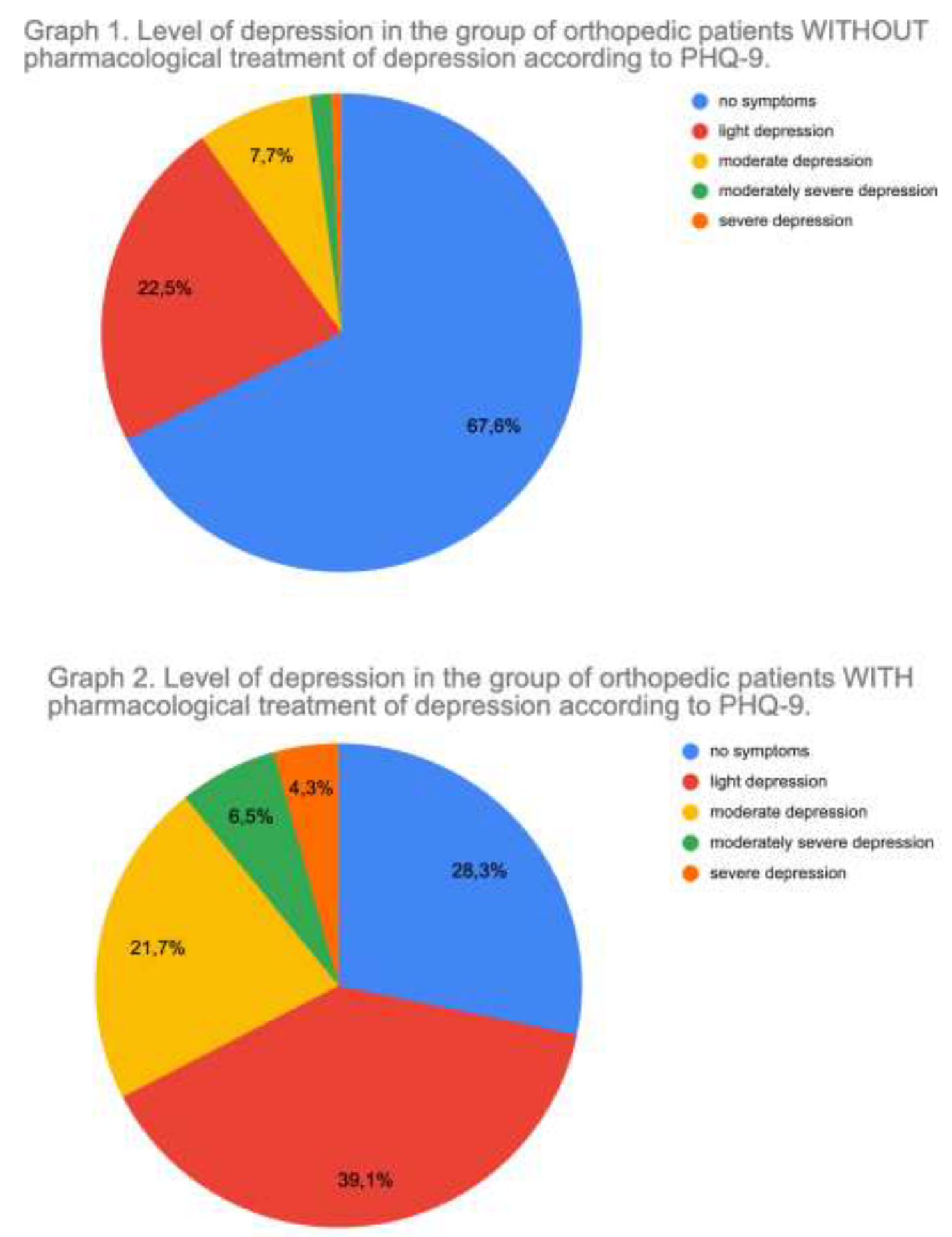

Among the 336 patients examined, there were 193 female (57%) and 143 male (43%). The median age in the entire group was 56 years (41.0, 67.0). Median BMI was 27.1 (24.0, 30.3). The median PHQ-9 score was 3.0 (1.0, 6.0). The median VAS score was 4.00 (2.75, 7.00). The median GAD-7 score was 3.0 (1.0, 6.0). A result indicating active symptoms of mild depression was observed in 87 people (25.9%). Moderate depression was found in 32 people (9.2%). Results for moderately severe and severe depression were found in 11 people (3.0%). Symptoms of generalized anxiety were observed in 38 people (11.3%). Current treatment for depression was reported by 37 women (19%) and 9 men (6%) that gives a total of 13.7% of the entire group. In the group not treated pharmacologically, symptoms of at least mild depression were present in 31.7% of patients. At least moderate depression was present in 10.4%. In the pharmacologically treated group, no symptoms of depression were present in only 28.3%, while symptoms of at least moderate depression were present in 32.3% of patients. The exact distribution is shown in Graph 1 and Graph 2.

Among patients treated for depression 6 (13%) patients were treated with medications only in the case of symptoms, 27 (58,7%) were constantly treated with one drug, 10 (21,7%) were treated with 2 drugs and 3 (6,5%) were treated with 3 drugs. Most commonly used drugs were Serraline and Trazodone (in 8 cases each), Escitalopram (6 cases), Pregabalin and Quetiapine (5 cases each), Duloxetine and Venlafaxine (4 cases each).

3.1. Statistical Analysis

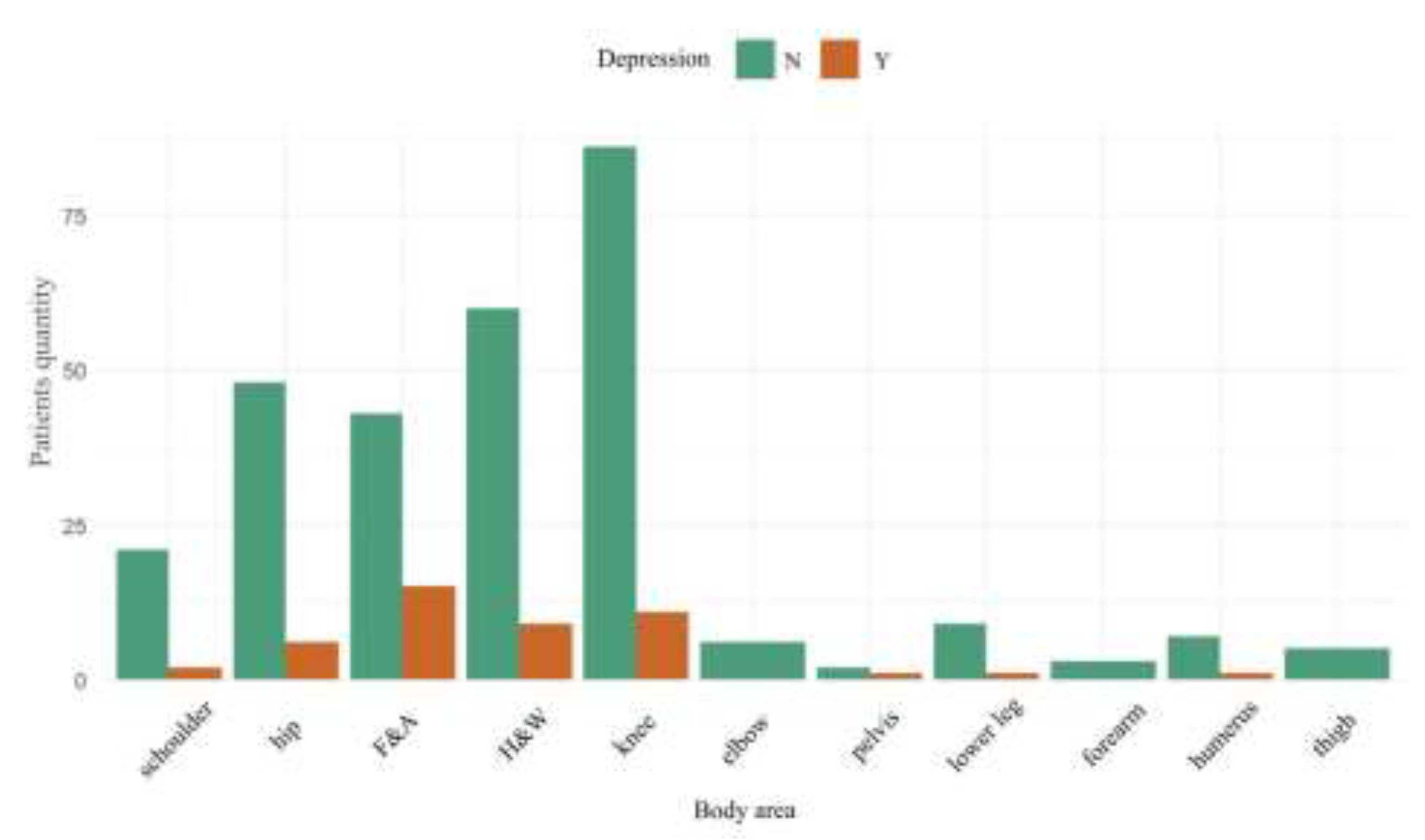

The groups of patients with and without treated depression did not differ significantly in terms of age and BMI. However, noticeable differences appeared in the incidence of depression in subgroups of patients according to the area of the body operated on, as shown in

Figure 1. The highest percentage of patients treated for depression were in the foot and ankle patient subgroup.

Subsequently, the analysis of the influence of independent factors on the occurrence of symptoms and treatment of depression was performed, paying attention to the operated area of the body. The quantitative results are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Statistical Difference Between Subgroups

The one-dimensional ANOVA was performed to verify the hypothesis that there are statistically significant differences in mean age between the subgroups. Significant differences in age were found between groups of patients with diseases of various body areas (p<0.01). Post hoc Tukey's test was then performed to compare all pairs of groups to identify which specific groups differed significantly from each other. It showed that a subgroup of patients with hip diseases were older than F&A patients and knee patients just with slight significance (p<0,03 and <0,06 respectively).

Based on the one-dimensional ANOVA analysis, significant differences in BMI were found between groups of patients with diseases to various parts of the body (p=0.02). However, post-hoc tests did not show any significant differences between specific groups.

Based on Fisher's exact test, there was no significant relationship between the operated body area and the gender predominance (p=0.3).

No significant differences were found of the results of GAD-7 and PHQ-9 tests in body area groups as well.

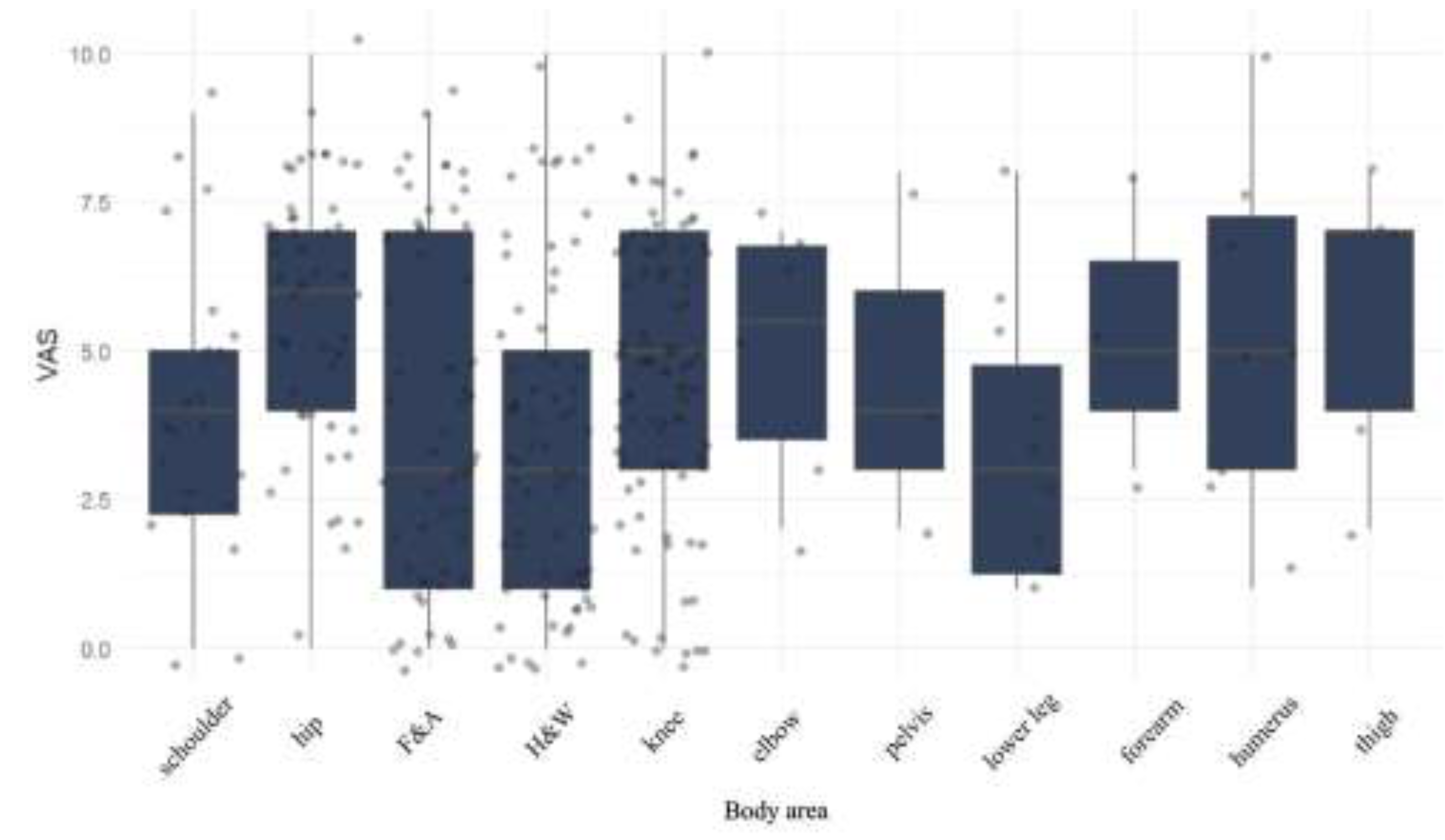

Using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, significant differences in pain VAS scores were found between groups of patients with injuries to various parts of the body (p=0.004). Post-hoc tests (Tukey test) showed that the median pain VAS in patients with hip disorders is statistically significantly higher compared to the one of H&W patients (6 (4-7) vs. 3 (1-5), p=0.0005) and F&A patients (6 (4-7) vs. 3 (1-7), p=0.0277). The detailed distribution is shown in

Figure 2.

3.3. Risk factors

At each point, stepwise estimation of logistic or linear regression models (based on the type of dependent variable) was performed. Additionally, 3-fold cross validation was used on the training set. The explanatory variables were selected from the following variables: gender (F/M), BMI, body region, age range (<20, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, >=70). Of all the estimated models, the best ones were selected based on the AIC criterion (the lower its value, the "better" the model). In each point, only the lowest p values and its parameters are presented in

Table 4. The F&A area surprisingly had a stronger coincidence with depression treatment than gender.

It shows the results of the estimation of the logistic regression model, in which the dependent variable is depression (taking the values yes-1/no-0). The model takes into account variable gender and body area (but only F&A). The reference value for age is people <20 years of age and for body region the reference value is shoulder. These model parameters, except age, are statistically significant (p<0.05).

The accuracy of the model on the test set was 82.5% with a sensitivity of 0.18 and specificity of 0.93. This model is statistically significantly better than the model with one independent variable (LRT test p-value<0.05)

Based on the OR value, it can be concluded that male patients have a 63% lower risk of depression compared to female patients. It was also shown that F&A patients have a more than 3 times higher risk of depression compared to patients from the reference group.

3.4. VAS vs PHQ-9 correlation

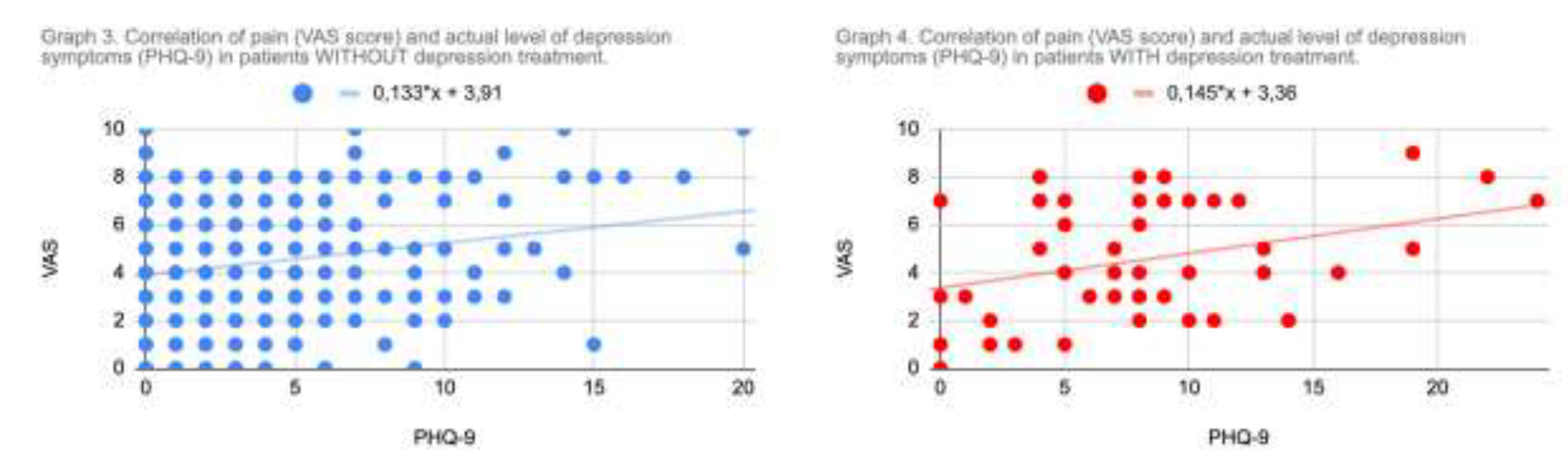

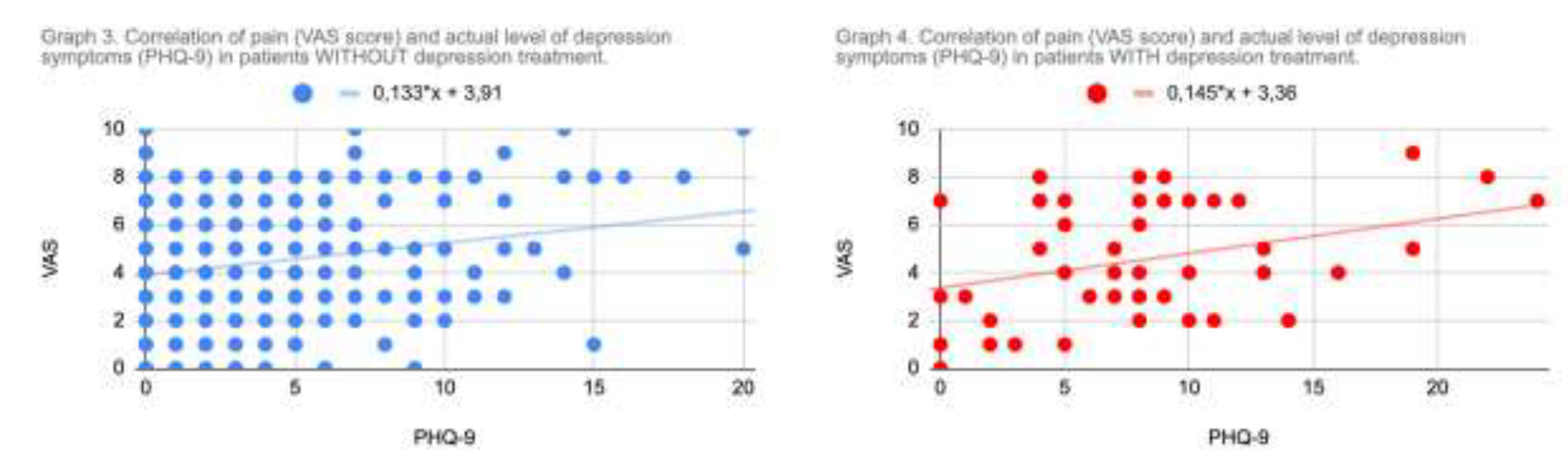

The analysis of covariance performed between VAS and PHQ-9 levels revealed some positive correlation as was visualized in Graph 3 and 4. There was no significant difference in the correlation between patients with and without depression treatment. Analysis of VAS vs anxiety level (GAD-7) did not reveal any correlation.

3.5. Summary

The incidence of depression in orthopedic patients is 13.7% in our group. Even in patients that were never treated for depression at least mild depression were present in 31.7% of cases. Our observations indicate that depression treatment usually reduces depression symptoms by one level according to the PHQ-9, and only 1/3 of patients show no symptoms.

Based on the OR male patients have a 63% lower risk of depression compared to female patients. It was also shown that F&A patients have a more than 3 times higher odds ratio of depression treatment compared to patients from the reference group. The incidence of depression was especially high in women over 40 years old and affected 36% of this group .

Some contradiction is noticeable in the comparison of groups of patients with hip and F&A complaints. The first of these groups is significantly older, reporting the greatest pain, and at the same time has the lowest incidence of depression, while the F&A group, despite average pain and age, has a much higher incidence of depression treatment.

4. Discussion

According to the WHO report, depression affects approximately 5% of the population globally. Javal et al., analyzing recent Global Burden of Disease dataset estimated prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders at 2-3%. In the report of the Polish National Health Fund (NFZ) from the period 2013-2023, the numbers concerning depression treatment correspond to approximately 4% of the population [2, 19, 20].

Muscatelli et al., in the review work on orthopedic trauma, depression and PTSD revealed that the depression prevalence in patients after orthopedic trauma reaches 32.6% after 6 months and 16% after 2 years post incident.

Weekes et al. described that 24% of patients had major depressive disorder at 1 year after the elective operation of the shoulder, while preoperatively the numbers corresponded to over 50% the group [6, 7, 10].

All above mentioned results correspond to the results of our work where 38.7% of patients showed symptoms of at least mild depression, 12.2% of moderate or severe depression and 11.3% showed generalized anxiety symptoms. As much as 13.7% of patients reported currently treated depression. That shows the incidence of generalized anxiety and depression in orthopedic patients several times greater than in the whole population.

Taking into account the operated area of the body, a surprisingly higher rate of treated depression was found in patients with foot and ankle disorders, especially among women over 40. The condition occurred approximately in 36%, i.e. three times more often than in the reference group of orthopedic patients and several times more than in the general population. Although F&A patients in our study did not show higher scores on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 tests, this may be due to the appearance of successfully treated depression.

The NCHS study, which includes an assessment of depression in different age groups, showed the lowest level observed in the age group of 30 to 44 years [

21].

Similarly, according to the report of the Polish National Health Fund (NFZ), the age group where the therapy was most frequent was 65-74 years [

19].

Abovementioned results are not consistent with our observation for F&A patients who were significantly more often treated for depression than patients with hip joint problems, despite their lower VAS pain score and relatively lower age.

Converging results for F&A patients were obtained by Nakagawa et al., where the prevalence of anxiety and depression was 30% and 27% respectively [

22]. Also in the work by Awale et al. strong correlation between foot pain and depression was observed [

23].

Further associations of depression and foot diseases are represented by numerous studies on diabetic foot and related non-healing ulcers [24-26].

Henry et al. described that patients with foot and ankle diseases and with depression have increased expectations regarding the treatment, less postoperative functional improvement and less satisfaction [

9].

Taking into account the above reports it can therefore be inferred that orthopaedic patients, and especially F&A patients may require a more sensitive and gentle approach. Appropriate selection of patients, proper setting of expectations, properly selected treatment of foot diseases and appropriately directed rehabilitation of the foot and ankle joint may have a beneficial impact not only on the general fitness but also on the patient's mental well-being. Regarding rehabilitation as well as non-pharmacological treatment, there is considerable support in the literature for the beneficial effect of foot reflexology on the alleviating symptoms of depression [27, 28].

As Trivedi described in his review, pain and depression share neurologic pathways, and thus physical and mental symptoms are commonly related. This explains the increased incidence of symptoms of depression in orthopedic patients presenting higher pain, yet does not explain such a significant difference in the frequency of depression in patients with foot and ankle diseases [

29].

The neuroanatomical basis of observed differences certainly requires further research.

So far, in the study by Vajapey et. al., it was observed that the patient's depression symptoms improved after orthopedic operative intervention [

13]. Although, there has been no clear confirmation that pharmacological treatment of depression significantly affects the results of surgical treatment of orthopedic diseases [

30].

Nonetheless, it is clear that depression negatively affects the functional results of surgical treatment of patients, increases infections and readmissions rates, worsens the results of rehabilitation and is associated with an increased total cost of treatment [7, 13, 30].

It is safe to assume that the problem of depression in orthopedic patients is not marginal. Unfortunately, orthopedic surgeons do not have sufficient scientific support to assist them in the decision-making process in case of a depressive patient.

In orthopedic practice, the patients who are less compliant and less susceptible to treatment are regularly encountered. There is a high probability that such a patient suffers from depression or generalized anxiety regardless of being aware of it. Of course, it is not the role of an orthopedist to carry out diagnostics or treatment of mental disorders. However, making both the doctor and the patients aware of these conditions and referring the latter to an appropriate specialist can significantly improve cooperation in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders.

Antidepressants and anxiolytics are used in the treatment of chronic pain in diseases such as cancer, where the prevalence of anxiety and depression is also very high. However, as an optional adjuvant pain therapy, these drugs can be administered from the first step of the analgesic ladder, together with simple NSAIDs [31, 32].

Perhaps in cases of milder depression associated with significant functional impairment or significant and chronic pain of the motor organ, it would be justified to use safe adjuvant drugs, such as Tianeptine or Trazodone, more frequently at the level of orthopedic outpatient clinics. However, this requires confirmation in further research.

Our study has several limitations. First of all, our group of 336 patients was relatively small as for population studies. It included approximately 2/3 of elective surgery patients due to many refusals to participate in the study or incorrect completion of questionnaires. Nonetheless, it covers patients from the entire year, which excludes potential seasonal fluctuations of the results. The single-center nature also reduces the power of this study.

Treatment for depression criteria only involved taking any antidepressant medication. The total number or type of medications, duration of therapy and the possible occurrence of psychotherapy were not taken into account. The division into body regions was also rather conventional, the foot and ankle groups as well as the hand and wrist groups were combined due to the organizational method of the department's work.

5. Discussion

Awareness of a patient's depression and anxiety should be considered an integral part of every doctor's practice. It is also a significant problem in orthopedic practice and has an impact on the progress of treatment of musculoskeletal diseases. The incidence of depression and anxiety in orthopedic patients is clearly higher than in the average population. Physical exercises, exceptionally dependent on motor skills, are a recognized element of the treatment of depressive disorders. The clearly increased incidence of treated depression observed in people suffering from foot and ankle disorders provides a basis for further neuroanatomical research and the development of an optimal care for orthopedic patients with depression as well as psychiatric patients with motor organ dispairment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Kuik.; methodology, L.Kuik and P. Łuczkiewicz; software, L.Kuik; validation, L.Kuik; formal analysis L. Kuik; investigation, L.Kuik; resources, L. Kuik and P. Łuczkiewicz; data curation, L.Kuik; writing—original draft preparation, L.Kuik; writing—review and editing, P. Łuczkiewicz; visualization, L.Kuik; supervision, P.Łuczkiewicz; project administration, L.Kuik and P. Łuczkiewicz; funding acquisition, L. Kuik and P.Łuczkiewicz. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The costs of statistical analysis in this research was funded by Medical University of Gdańsk.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to observational character of the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available through a direct contact with corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mr. Maciej Pawlak, BA, for thorough language correction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Muscatelli, S.; Spurr, H.; O’Hara, N.N.; O’Hara, L.M.; Sprague, S.A.; Slobogean, G.P. Prevalence of Depression and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Acute Orthopaedic Trauma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 2017, 31, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawi, M.J.; Gronbeck, C.; Savoy, L.; Cote, M.P.; Lieberman, J.R. Depression Treatment Is Not Associated With Improved Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Total Joint Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2020, 35, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weekes, D.G.; Campbell, R.E.; Shi, W.J.; Giunta, N.; Freedman, K.B.; Pepe, M.D.; Tucker, B.S.; Tjoumakaris, F.P. Prevalence of Clinical Depression Among Patients After Shoulder Stabilization: A Prospective Study. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2019, 101, 1628–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajapey, S.P.; McKeon, J.F.; Krueger, C.A.; Spitzer, A.I. Outcomes of Total Joint Arthroplasty in Patients with Depression: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 2021, 18, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Rief, W.; Klaiberg, A.; Braehler, E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the General Population. General Hospital Psychiatry 2006, 28, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Navarro, R.; Cano-Vindel, A.; Medrano, L.A.; Schmitz, F.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, P.; Abellán-Maeso, C.; Font-Payeras, M.A.; Hermosilla-Pasamar, A.M. Utility of the PHQ-9 to Identify Major Depressive Disorder in Adult Patients in Spanish Primary Care Centres. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Medical Care 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, H.; Suen, Y.N.; Hui, C.L.M.; Wong, S.M.Y.; Chan, S.K.W.; Lee, E.H.M.; Wong, M.T.H.; Chen, E.Y.H. Assessing Anxiety among Adolescents in Hong Kong: Psychometric Properties and Validity of the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) in an Epidemiological Community Sample. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Regular Physical Exercise and Its Association with Depression: A Population-Based Study Short Title: Exercise and Depression. Psychiatry Research 2022, 309, 114406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD Results. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Javaid, S.F.; Hashim, I.J.; Hashim, M.J.; Stip, E.; Samad, M.A.; Ahbabi, A.A. Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders: Global Burden and Sociodemographic Associations. Middle East Current Psychiatry 2023, 30, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Jaime, H.; Sánchez-Salcedo, J.A.; Estevez-Cabrera, M.M.; Molina-Jiménez, T.; Cortes-Altamirano, J.L.; Alfaro-Rodríguez, A. Depression and Pain: Use of Antidepressants. CN 2022, 20, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anekar, A.A.; Hendrix, J.M.; Cascella, M. WHO Analgesic Ladder. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raport: NFZ o Zdrowiu. Depresja.

- Villarroel, M.A.; Terlizzi, E.P. Symptoms of Depression Among Adults: United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, B.M.; Shih, C.-D.; Brooks, B.M.; Tower, D.E.; Tran, T.T.; Simon, J.E.; Armstrong, D.G. The Diabetic Foot-Pain-Depression Cycle. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2023, 113, 22–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.-H.; Liu, X.-M.; Yu, H.-R.; Qian, Y.; Chen, H.-L. The Incidence of Depression in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2022, 21, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maydick, D.R.; Acee, A.M. Comorbid Depression and Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Home Healthc Now 2016, 34, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavipour, F.; Rahemi, Z.; Sadat, Z.; Ajorpaz, N.M. The Effects of Foot Reflexology on Depression during Menopause: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Complement Ther Med 2019, 47, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.K.; Barth, K.; Cororaton, A.; Hummel, A.; Cody, E.A.; Mancuso, C.A.; Ellis, S. Association of Depression and Anxiety With Expectations and Satisfaction in Foot and Ankle Surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2021, 29, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, R.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kimura, S.; Sadamasu, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sato, Y.; Akagi, R.; Sasho, T.; Ohtori, S. Association of Anxiety and Depression With Pain and Quality of Life in Patients With Chronic Foot and Ankle Diseases. Foot Ankle Int 2017, 38, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, R.; Daniel, J.-P.A.; Idarraga, A.J.; Perticone, K.M.; Lin, J.; Holmes, G.B.; Lee, S.; Hamid, K.S.; Bohl, D.D. Depression Following Operative Treatments for Achilles Ruptures and Ankle Fractures. Foot Ankle Int 2021, 42, 1579–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagrave, K.G.; Lewin, A.M.; Harris, I.A.; Badge, H.; Naylor, J. Association between Pre-Operative Anxiety and/or Depression and Outcomes Following Total Hip or Knee Arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2021, 29, 2309499021992605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alattas, S.A.; Smith, T.; Bhatti, M.; Wilson-Nunn, D.; Donell, S. Greater Pre-Operative Anxiety, Pain and Poorer Function Predict a Worse Outcome of a Total Knee Arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017, 25, 3403–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambamoorthi, U.; Shah, D.; Zhao, X. Healthcare Burden of Depression in Adults with Arthritis. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2017, 17, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuillan, T.J.; Bernstein, D.N.; Merchan, N.; Franco, J.; Nessralla, C.J.; Harper, C.M.; Rozental, T.D. The Association Between Depression and Antidepressant Use and Outcomes After Operative Treatment of Distal Radius Fractures at 1 Year. J Hand Surg Am 2022, 47, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crijns, T.J.; Bernstein, D.N.; Gonzalez, R.; Wilbur, D.; Ring, D.; Hammert, W.C. Operative Treatment Is Not Associated with More Relief of Depression Symptoms than Nonoperative Treatment in Patients with Common Hand Illness. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2020, 478, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, D.T.; Gevers Deynoot, B.D.J.; Stufkens, S.A.; Sierevelt, I.N.; Goslings, J.C.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J.; Doornberg, J.N. What Factors Are Associated With Outcomes Scores After Surgical Treatment Of Ankle Fractures With a Posterior Malleolar Fragment? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2019, 477, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awale, A.; Dufour, A.B.; Katz, P.; Menz, H.B.; Hannan, M.T. Link Between Foot Pain Severity and Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016, 68, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, S.; Xu, H.; Peng, J.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, W.; Shi, L.; et al. The Burden of Mental Disorders in Asian Countries, 1990–2019: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, M.H. The Link between Depression and Physical Symptoms. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2004, 6, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.-L.; Hung, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-R.; Chen, K.-H.; Yang, S.-N.; Chu, C.-M.; Chan, Y.-Y. Effect of Foot Reflexology Intervention on Depression, Anxiety, and Sleep Quality in Adults: A Meta-Analysis and Metaregression of Randomized Controlled Trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020, 2020, 2654353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).