Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scientometric Approach to the Study Topic

2.2. Ingredients and Microorganisms Used in the Formulation

2.3. Nutritional Characterization of the Formulation

2.4. Assessment of Antioxidant Potential, Content of Total Phenolic Compounds, and Lipid Peroxidation

2.5. Evaluation of Viable Probiotic Cell Content, Analysis of Resistance to Simulated Gastric and Intestinal Conditions, and Resistance to Heat Treatment

2.6. Morphological Aspects and Zeta Potential of Food Supplement

2.7. Microbiological Quality of Food Supplement

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

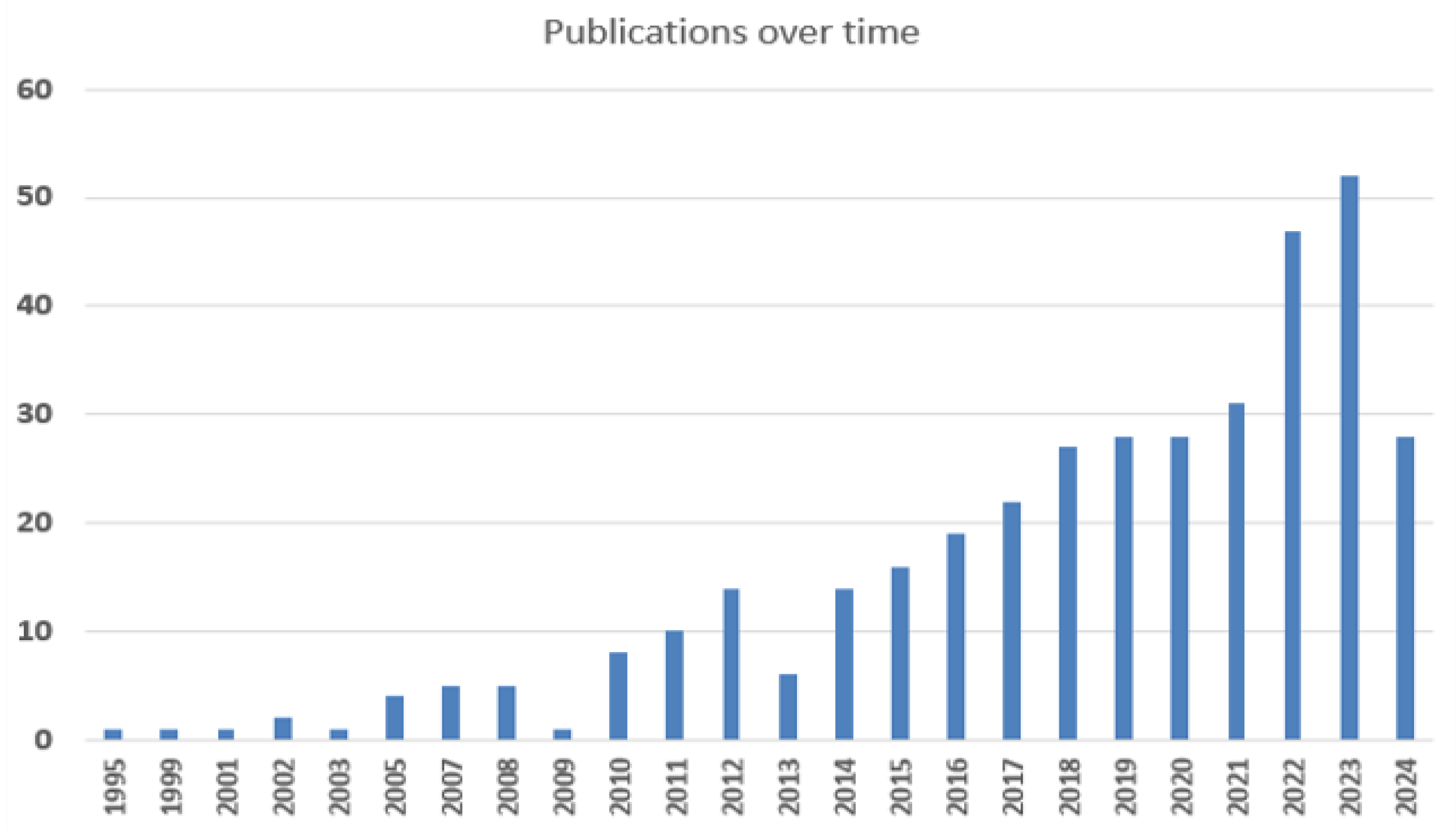

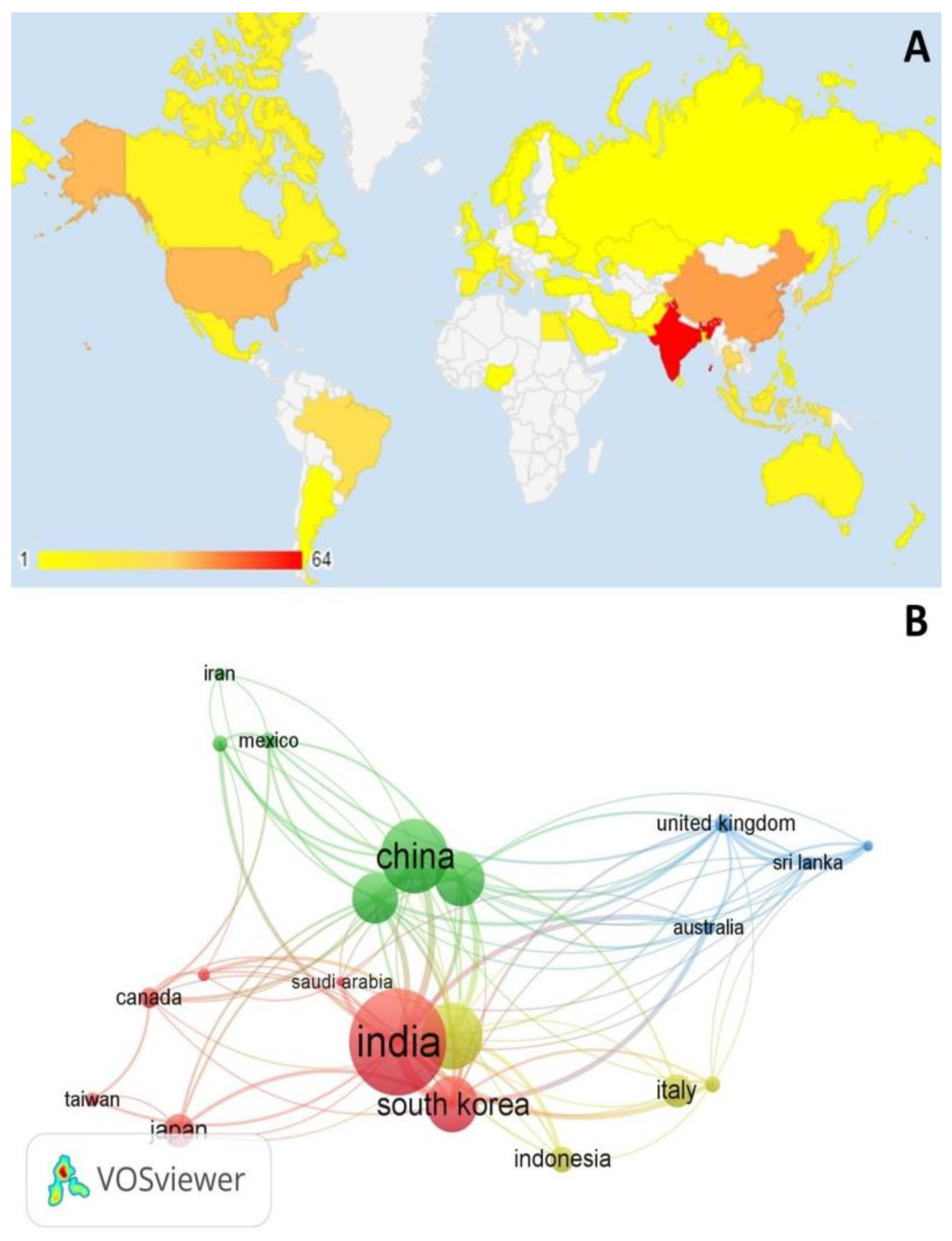

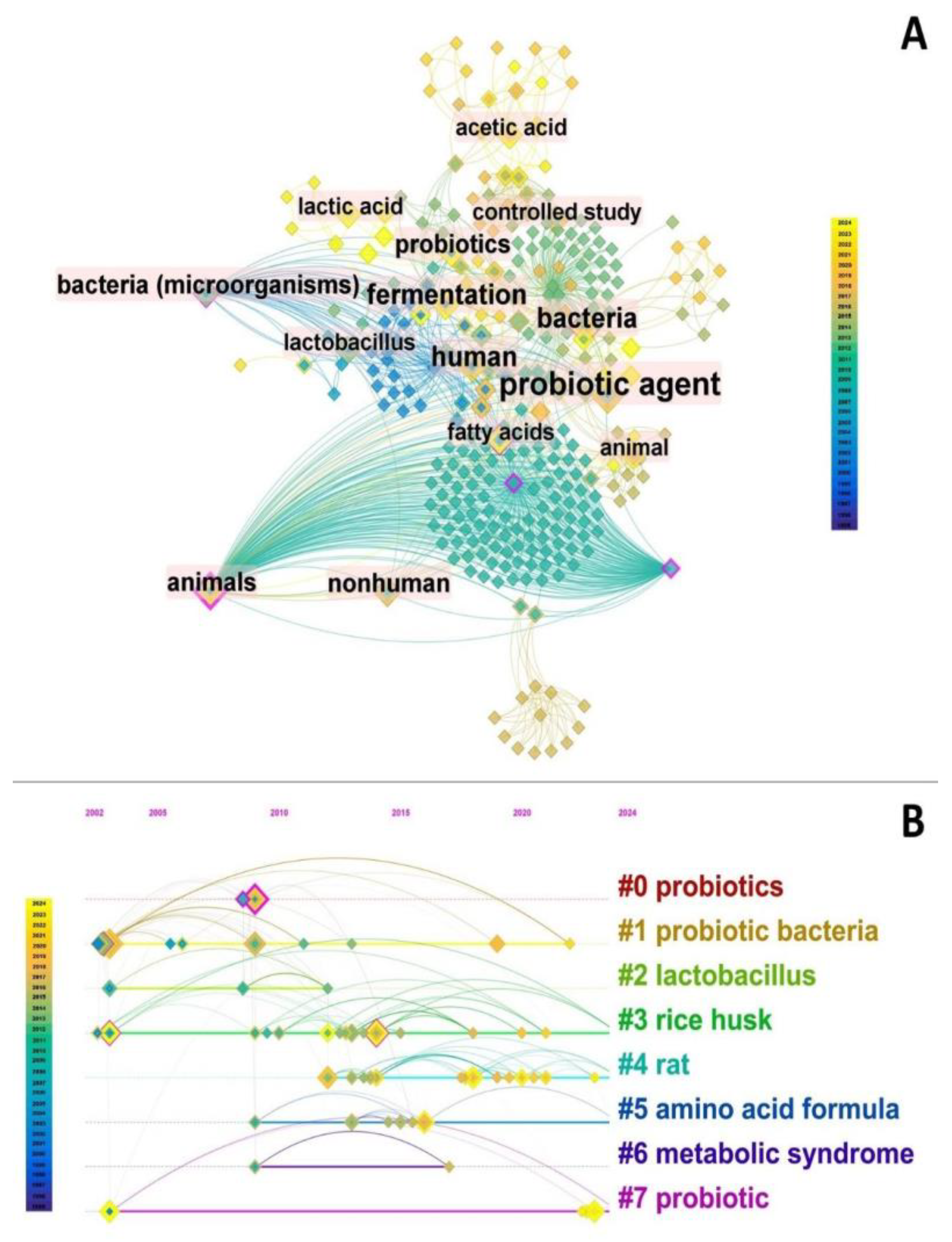

3.1. Scientometric Assessment

3.2. Nutritional and Microbiological Quality of Food Supplement Formulation

3.3. Antioxidant Potential and Lipid Peroxidation

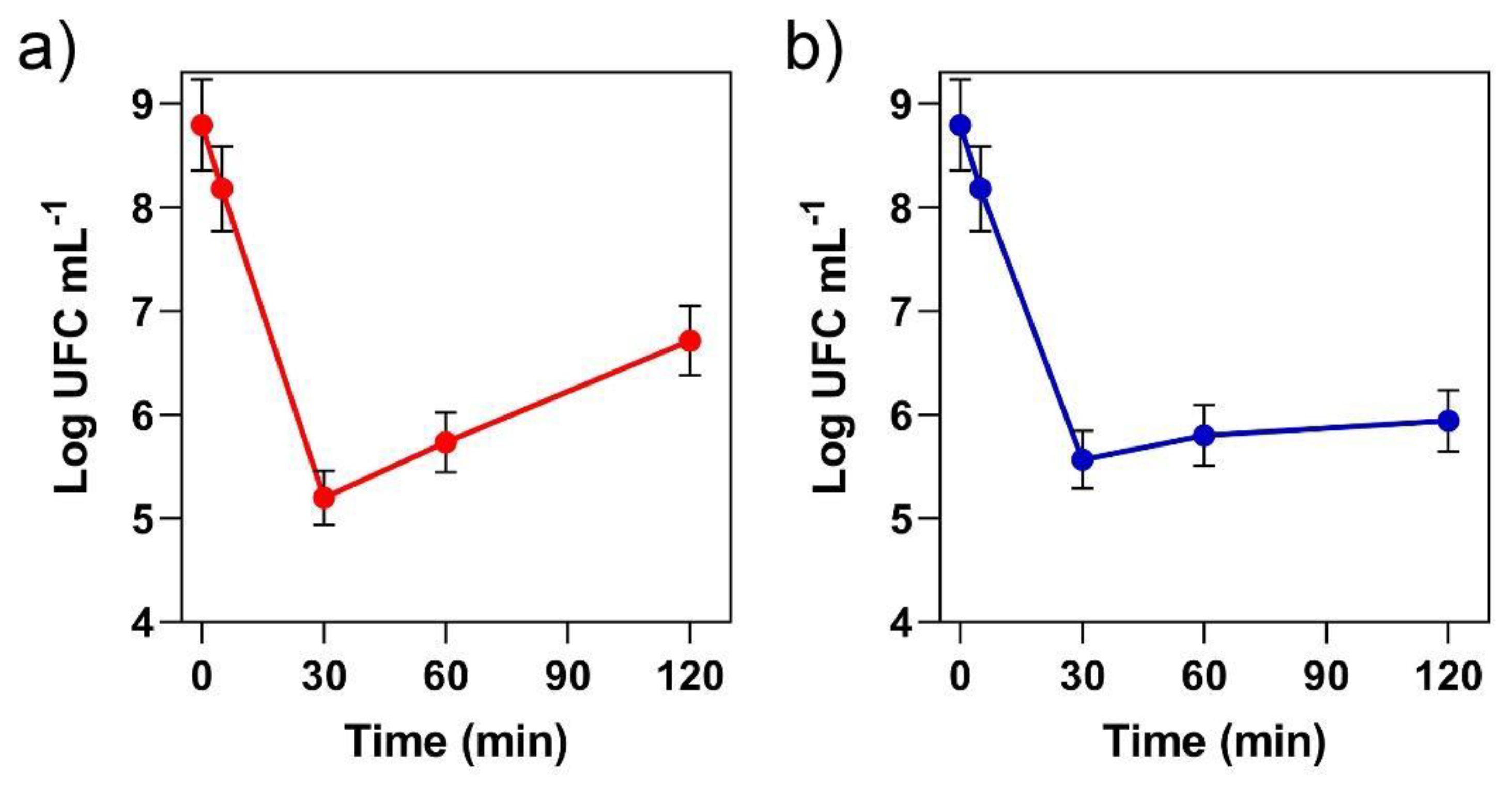

3.4. Resistance of Probiotic Cells to Simulated Gastric and Intestinal Conditions and Heat Stability

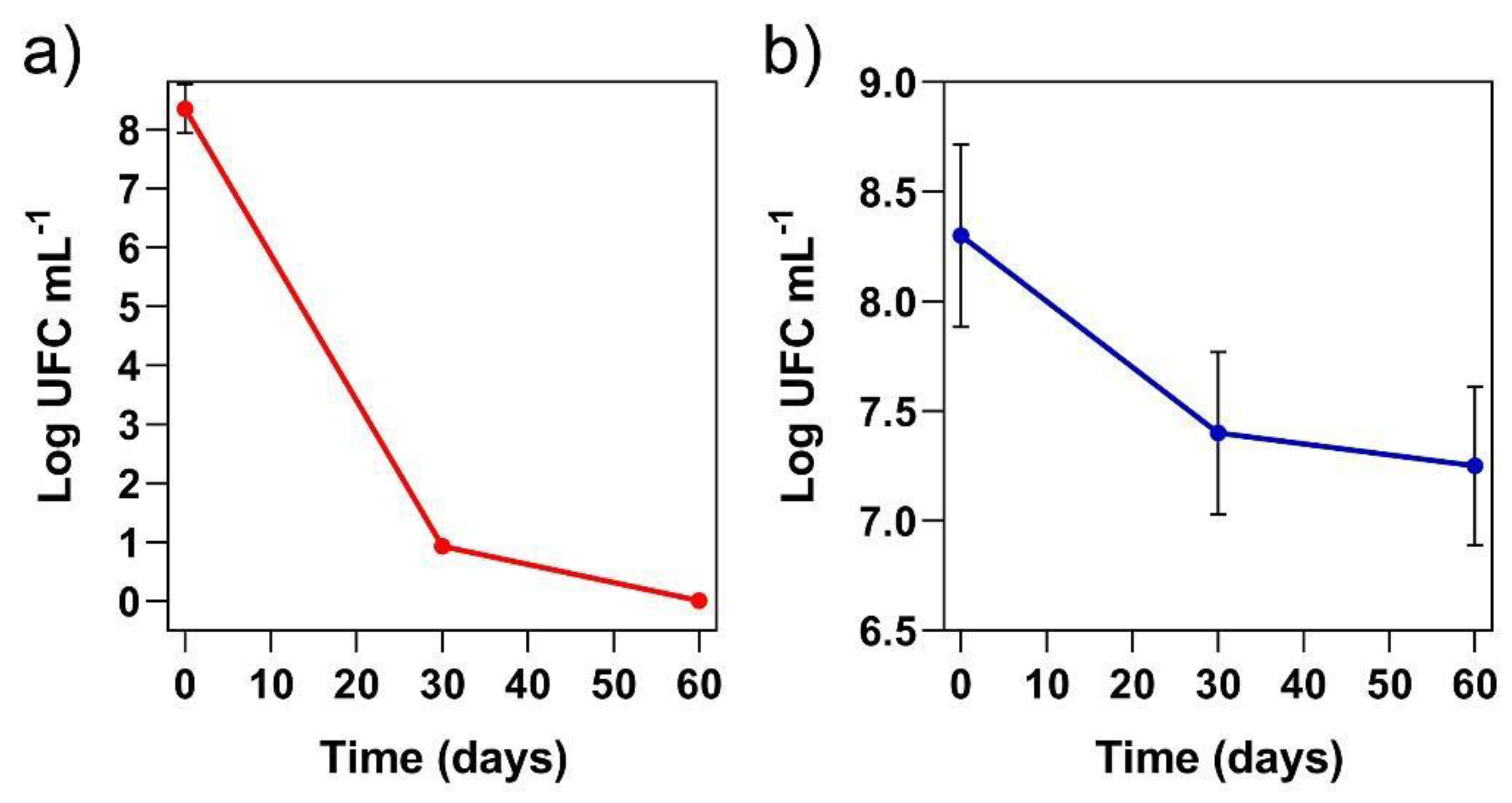

3.5. Cell Viability During the Storage Period at Room Temperature and Under Freezing Conditions

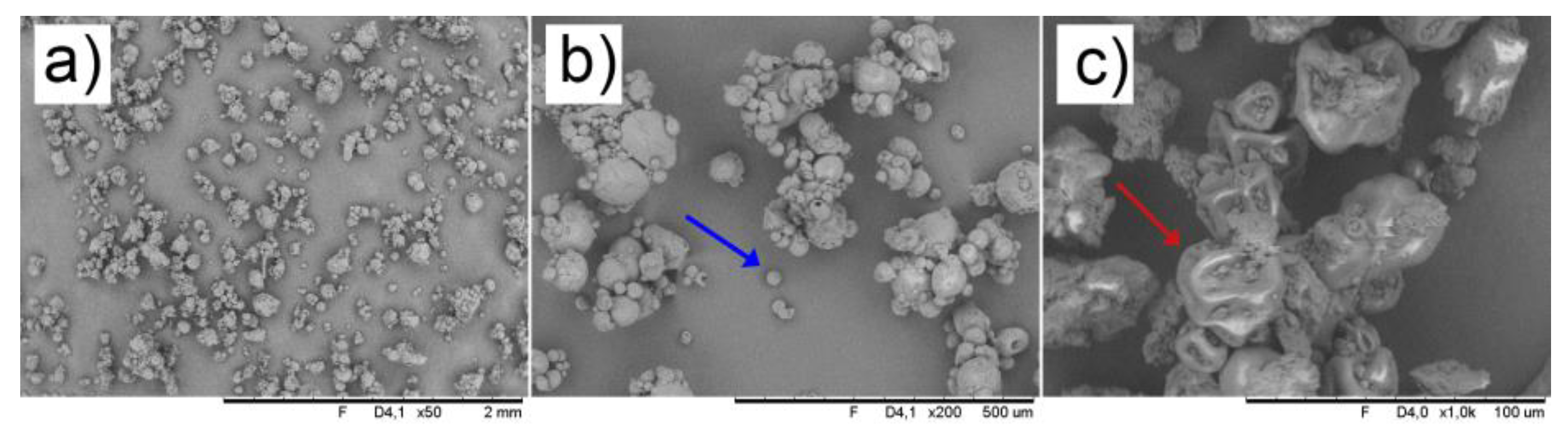

3.6. Morphological Aspects and Zeta Potential

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christiansen, B.; Yıldız, S.; Yıldız, E. (Eds.) Transcultural Marketing for Incremental and Radical Innovation; 1st ed.; Business Science Reference: Hershey, 2013; ISBN 1466647493. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav, H.B. Functional Triacylglycerols from Microalgae and Their Use in the Formulation of Functional Foods—Review. Food Chemistry Advances 2024, 4, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.K. (Ed.) Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Fruits and Vegetables; 1st Editio.; Elsevier: London, 2020; ISBN 9780128127803. [Google Scholar]

- Abuajah, C.I.; Ogbonna, A.C.; Osuji, C.M. Functional Components and Medicinal Properties of Food: A Review. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2015, 52, 2522–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mileriene, J.; Serniene, L.; Kondrotiene, K.; Lauciene, L.; Kasetiene, N.; Sekmokiene, D.; Andruleviciute, V.; Malakauskas, M. Quality and Nutritional Characteristics of Traditional Curd Cheese Enriched with Thermo-coagulated Acid Whey Protein and Indigenous Lactococcus Lactis Strain. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2021, 56, 2853–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, M.; Kodama, K.; Arato, T.; Okazaki, T.; Oda, T.; Ikeda, H.; Sengoku, S. Comparative Study of Functional Food Regulations in Japan and Globally. Global Journal of Health Science 2019, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Someko, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Ito, T.; Suzuki, T.; Tsuge, T.; Yabuzaki, H.; Dohi, E.; Kataoka, Y. Misleading Presentations in Functional Food Trials Led by Contract Research Organizations Were Frequently Observed in Japan: Meta-Epidemiological Study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2024, 169, 111302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringel, A. Complexo Industrial Da Yakult Completa 20 Anos. Available online: https://www.yakult.com.br/noticias/complexo- industrial-da-yakult-completa-20-anos/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Sgroi, F.; Sciortino, C.; Baviera-Puig, A.; Modica, F. Analyzing Consumer Trends in Functional Foods: A Cluster Analysis Approach. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2024, 15, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, D.; Reichert, J.L.; Koschutnig, K.; Aigner, C.S.; Holzer, P.; Koskinen, K.; Moissl-Eichinger, C.; Schöpf, V. Probiotics Drive Gut Microbiome Triggering Emotional Brain Signatures. Gut Microbes 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani, K.; Falah, F.; Vasiee, A.; Yazdi, F.T.; Behbahani, B.A.; Zanganeh, H. Effects of Incorporation of Echinops Setifer Extract on Quality, Functionality, and Viability of Strains in Probiotic Yogurt. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2022, 16, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Huys, G.; Daube, G. Probiotics: An Update. Jornal de Pediatria 2015, 91, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyashree, S.; Ramu, R.; Sreenivasa, M.Y. Evaluation of New Candidate Probiotic Lactobacillus Strains Isolated from a Traditional Fermented Food- Multigrain-Millet Dosa Batter. Food Bioscience 2024, 57, 103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrezenmeir, J.; de Vrese, M. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics—Approaching a Definition. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2001, 73, 361s–364s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, E.M.M. Prebiotics and Probiotics in Digestive Health. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019, 17, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cupertino, M.D.C.; Resende, M.B.; Veloso, I.D.F.; Carvalho, C.A. de; Duarte, V.F.; Ramos, G.A. Transtorno Do Espectro Autista: Uma Revisão Sistemática Sobre Aspectos Nutricionais e Eixo Intestino-Cérebro. ABCS Health Sciences 2019, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Bakian, A. V.; Bilder, D.A.; Durkin, M.S.; Esler, A.; Furnier, S.M.; Hallas, L.; Hall-Lande, J.; Hudson, A.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 2021, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.K.H.; Tong, V.J.W.; Syn, N.; Nagarajan, N.; Tham, E.H.; Tay, S.K.; Shorey, S.; Tambyah, P.A.; Law, E.C.N. Gut Microbiota Changes in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Gut Pathogens 2020, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, L.; Dooling, S.W.; Volpe, E.; Uljarević, M.; Waters, J.L.; Sabatini, A.; Arturi, L.; Abate, R.; Riccioni, A.; Siracusano, M.; et al. Precision Microbial Intervention Improves Social Behavior but Not Autism Severity: A Pilot Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Cell Host & Microbe 2024, 32, 106–116.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.-J.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Kwong, K.; Koh, M.; Sukijthamapan, P.; Guo, J.J.; Sun, Z.J.; Song, Y. Probiotics and Oxytocin Nasal Spray as Neuro-Social-Behavioral Interventions for Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 2020, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Koh, G. Clinical Evidence and Mechanisms of High-Protein Diet-Induced Weight Loss. Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome 2020, 29, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C. da C.; Flor, K. de O.; Zago, L.; Miyahira, R.F. Estratégias Gastronômicas Para Melhorar a Aceitabilidade de Dietas Hospitalares: Uma Breve Revisão. Research, Society and Development 2021, 10, e42510515138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendia, J.R.; Bradlee, M.L.; Singer, M.R.; Moore, L.L. Diets Higher in Protein Predict Lower High Blood Pressure Risk in Framingham Offspring Study Adults. American Journal of Hypertension 2015, 28, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertzler, S.R.; Lieblein-Boff, J.C.; Weiler, M.; Allgeier, C. Plant Proteins: Assessing Their Nutritional Quality and Effects on Health and Physical Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Cruz Ferraz Dutra, J.; Passos, M.F.; García, G.J.Y.; Gomes, R.F.; Magalhães, T.A.; dos Santos Freitas, A.; Laguna, J.G.; da Costa, F.M.R.; da Silva, T.F.; Rodrigues, L.S.; et al. Anaerobic Digestion Using Cocoa Residues as Substrate: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Energy for Sustainable Development 2023, 72, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, J.; Gomes, R.; Yupanqui García, G.J.; Romero-Cale, D.X.; Santos Cardoso, M.; Waldow, V.; Groposo, C.; Akamine, R.N.; Sousa, M.; Figueiredo, H.; et al. Corrosion-Influencing Microorganisms in Petroliferous Regions on a Global Scale: Systematic Review, Analysis, and Scientific Synthesis of 16S Amplicon Metagenomic Studies. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International Official Methods of Analysis; Latimer Jr, G., Ed.; 20th ed.; AOAC INTERNATIONAL: Rockville, MD, 2016; Vol. 52; ISBN 0935584870.

- Lasta, E.L.; da Silva Pereira Ronning, E.; Dekker, R.F.H.; da Cunha, M.A.A. Encapsulation and Dispersion of Lactobacillus Acidophilus in a Chocolate Coating as a Strategy for Maintaining Cell Viability in Cereal Bars. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 20550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.A.; Hart, R.J.; Fry, J.C. An Evaluation of the Waters Pico-Tag System for the Amino-acid Analysis of Food Materials. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 1986, 8, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesler, R.; Malta, L.G.; Carrasco, L.C.; Holanda, R.B.; Sousa, C.A.S.; Pastore, G.M. Atividade Antioxidante de Frutas Do Cerrado. Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos 2007, 27, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhao, M.; Sun, W. Effect of Protein Oxidation on the in Vitro Digestibility of Soy Protein Isolate. Food Chemistry 2013, 141, 3224–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi, A.; Calegari, M.A.; Calegari, G.C.; Santos, V.A.Q.; Wermuth, D.; Cunha, M.A.A. da; Oldoni, T.L.C. Bioactive Compounds from Syzygium Malaccense Leaves: Optimization of the Extraction Process, Biological and Chemical Characterization. Acta Scientiarum. Technology 2020, 42, e46773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenales-Sierra, I.M.; Lobato-Calleros, C.; Vernon-Carter, E.J.; Hernández-Rodríguez, L.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J. Calcium Alginate Beads Loaded with Mg(OH)2 Improve L. Casei Viability under Simulated Gastric Condition. LWT 2019, 112, 108220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, S.A.; Akhter, R.; Masoodi, F.A.; Gani, A.; Wani, S.M. Effect of Double Alginate Microencapsulation on in Vitro Digestibility and Thermal Tolerance of Lactobacillus Plantarum NCDC201 and L. Casei NCDC297. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2017, 83, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization ISO 7932:2004 - Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs — Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Presumptive Bacillus Cereus — Colony-Count Technique at 30 Degrees C; 2004; Vol. 2004, p. 13.

- Djaoudene, O.; Romano, A.; Bradai, Y.D.; Zebiri, F.; Ouchene, A.; Yousfi, Y.; Amrane-Abider, M.; Sahraoui-Remini, Y.; Madani, K. A Global Overview of Dietary Supplements: Regulation, Market Trends, Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and Health Effects. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Mithul Aravind, S.; Charpe, P.; Ajlouni, S.; Ranadheera, C.S.; Chakkaravarthi, S. Traditional Rice-Based Fermented Products: Insight into Their Probiotic Diversity and Probable Health Benefits. Food Bioscience 2022, 50, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Barnard, A.; Benoit, V.; Grimaldi, R.; Guyonnet, D.; Holscher, H.D.; Hunter, K.; Manurung, S.; Obis, D.; et al. Shaping the Future of Probiotics and Prebiotics. Trends in Microbiology 2021, 29, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, B.; McCarron, P.; Hong, Y.; Birse, N.; Wu, D.; Elliott, C.T.; Ch, R. Elementomics Combined with Dd-SIMCA and K-NN to Identify the Geographical Origin of Rice Samples from China, India, and Vietnam. Food Chemistry 2022, 386, 132738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuneu-Corral, C.; Puig-Montserrat, X.; Flaquer, C.; Mata, V.A.; Rebelo, H.; Cabeza, M.; López-Baucells, A. Bats and Rice: Quantifying the Role of Insectivorous Bats as Agricultural Pest Suppressors in Rice Fields. Ecosystem Services 2024, 66, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longvah, T.; Bhargavi, I.; Sharma, P.; Hiese, Z.; Ananthan, R. Nutrient Variability and Food Potential of Indigenous Rice Landraces (Oryza Sativa L.) from Northeast India. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 114, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Choudhary, M.; Sharma, V.; Kant, A.; Vashistt, J.; Garlapati, V.K.; Simal-Gandara, J. Exploration of Indian Traditional Recipe “Tarvaani” from the Drained Rice Gruel for Nutritional and Probiotic Potential. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 2023, 31, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A.; Pandey, V.K.; Dar, A.H.; Fayaz, U.; Dash, K.K.; Shams, R.; Ahmad, S.; Bashir, I.; Fayaz, J.; Singh, P.; et al. Rice Bran: Nutritional, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Profile and Its Contribution to Human Health Promotion. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 2, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, I.; Durand-Morat, A.; Nalley, L.L.; Alam, M.J.; Nayga, R. Rice Quality and Its Impacts on Food Security and Sustainability in Bangladesh. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0261118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.W.; Kobayashi, K.; Shen, L.; Inagaki, J.; Ide, M.; Hwang, S.S.; Matsuura, E. Antioxidative Attributes of Rice Bran Extracts in Ameliorative Effects of Atherosclerosis-Associated Risk Factors. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Science and Technology; Campbell-Platt, G., Ed.; 2nd editio.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, 2017; ISBN 978047706734423. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, M.A. Nanotechnology in Food and Plant Science: Challenges and Future Prospects. Plants 2023, 12, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkir, P.; Kemahlioglu, K.; Yucel, U. Foodomics: A New Approach in Food Quality and Safety. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 108, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikord, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Kamankesh, M.; Shariatifar, N. Food Safety and Quality Assessment: Comprehensive Review and Recent Trends in the Applications of Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS). Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 62, 4833–4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.Y.; Jeong, J.K.; Lee, Y.E.; Daily, J.W. Health Benefits of Kimchi (Korean Fermented Vegetables) as a Probiotic Food. Journal of Medicinal Food 2014, 17, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.D.; Jha, A.; Sabikhi, L.; Singh, A.K. Significance of Coarse Cereals in Health and Nutrition: A Review. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2014, 51, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, P.M.; Hegele, R.A. Functional Foods and Dietary Supplements for the Management of Dyslipidaemia. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2017, 13, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murooka, Y.; Yamshita, M. Traditional Healthful Fermented Products of Japan. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2008, 35, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullón, P.; Moura, P.; Esteves, M.P.; Girio, F.M.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J.C. Assessment on the Fermentability of Xylooligosaccharides from Rice Husks by Probiotic Bacteria. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2008, 56, 7482–7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Reyes, S. V.; Garcia-Suarez, F.J.; Jiménez, M.T.; San Martín-Gonzalez, M.F.; Bello-Perez, L.A. Protection of L. Rhamnosus by Spray-Drying Using Two Prebiotics Colloids to Enhance the Viability. Carbohydrate Polymers 2014, 102, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwar, B.A.; Gani, A.; Gani, A.; Shah, A.; Masoodi, F.A. Production of RS4 from Rice Starch and Its Utilization as an Encapsulating Agent for Targeted Delivery of Probiotics. Food Chemistry 2018, 239, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, M.; Nakano, M. The Effect of a Probiotic on Faecal and Liver Lipid Classes in Rats. British Journal of Nutrition 1995, 73, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias-Martins, A.M.; Pessanha, K.L.F.; Pacheco, S.; Rodrigues, J.A.S.; Carvalho, C.W.P. Potential Use of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum Glaucum (L.) R. Br.) in Brazil: Food Security, Processing, Health Benefits and Nutritional Products. Food Research International 2018, 109, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K.; Ray, M.; Adak, A.; Halder, S.K.; Das, A.; Jana, A.; Parua (Mondal), S.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Das Mohapatra, P.K.; Pati, B.R.; et al. Role of Probiotic Lactobacillus Fermentum KKL1 in the Preparation of a Rice Based Fermented Beverage. Bioresource Technology 2015, 188, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.; Ghosh, K.; Singh, S.; Chandra Mondal, K. Folk to Functional: An Explorative Overview of Rice-Based Fermented Foods and Beverages in India. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2016, 3, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodzi, N.A.R.M.; Lee, L.K. Traditional Fermented Foods as Vehicle of Non-Dairy Probiotics: Perspectives in South East Asia Countries. Food Research International 2021, 150, 110814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuloria, S.; Mehta, J.; Talukdar, M.P.; Sekar, M.; Gan, S.H.; Subramaniyan, V.; Rani, N.N.I.M.; Begum, M.Y.; Chidambaram, K.; Nordin, R.; et al. Synbiotic Effects of Fermented Rice on Human Health and Wellness: A Natural Beverage That Boosts Immunity. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemarie, Y.B.; Milanda, T.; Barliana, M.I. Fermented Foods as Probiotics. Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research 2021, 12, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anee, I.J.; Alam, S.; Begum, R.A.; Shahjahan, R.M.; Khandaker, A.M. The Role of Probiotics on Animal Health and Nutrition. The Journal of Basic and Applied Zoology 2021, 82, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogoju, S.; Nahashon, S. Recent Advances in Probiotic Application in Animal Health and Nutrition: A Review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhounde, S.; Adéoti, K.; Mounir, M.; Giusti, A.; Refinetti, P.; Otu, A.; Effa, E.; Ebenso, B.; Adetimirin, V.O.; Barceló, J.M.; et al. Applications of Probiotic-Based Multi-Components to Human, Animal and Ecosystem Health: Concepts, Methodologies, and Action Mechanisms. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S.; Yang, Z.; Yan, F.; Xue, X.; Lu, J. Preparation of Xylooligosaccharides from Rice Husks and Their Structural Characterization, Antioxidant Activity, and Probiotic Properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 271, 132575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordi, M.; Farrokhi, N.; Pech-Canul, M.I.; Ahmadikhah, A. Rice Husk at a Glance: From Agro-Industrial to Modern Applications. Rice Science 2024, 31, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivanoğlu, H.; Bardakçi, H.F.; Yaman, M. Protein Quality Assessment of Commercial Whey Protein Supplements Commonly Consumed in Turkey by in Vitro Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS). Food Science and Technology 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorissen, S.H.M.; Crombag, J.J.R.; Senden, J.M.G.; Waterval, W.A.H.; Bierau, J.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J.C. Protein Content and Amino Acid Composition of Commercially Available Plant-Based Protein Isolates. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerksick, C.M.; Wilborn, C.D.; Roberts, M.D.; Smith-Ryan, A.; Kleiner, S.M.; Jäger, R.; Collins, R.; Cooke, M.; Davis, J.N.; Galvan, E.; et al. ISSN Exercise & Sports Nutrition Review Update: Research & Recommendations. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.R.; Falvo, M.J. Protein - Which Is Best? Journal of sports science & medicine 2004, 3, 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut Microbiota, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology 2016, 16, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervik, A.K.; Svihus, B. The Role of Fiber in Energy Balance. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2019, 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Carmo, M.; Walker, J.; Novello, D.; Caselato, V.; Sgarbieri, V.; Ouwehand, A.; Andreollo, N.; Hiane, P.; Dos Santos, E. Polydextrose: Physiological Function, and Effects on Health. Nutrients 2016, 8, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, Z.; Bang-yao, L.; Ming-jie, X.; Hai-wei, L.; Zu-kang, Z.; Ting-song, W.; Craig, S.A. Studies on the Effects of Polydextrose Intake on Physiologic Functions in Chinese People. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000, 72, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röytiö, H.; Ouwehand, A.C. The Fermentation of Polydextrose in the Large Intestine and Its Beneficial Effects. Beneficial Microbes 2014, 5, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA) Instrução Normativa - IN N° 75, de 8 de Outubro de 2020, Que Estabelece Os Requisitos Técnicos Para Declaração Da Rotulagem Nutricional Nos Alimentos Embalados; Brasil, 2020; p. 53;

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) - World Health Organization (WHO) Food-Based Dietary Guidelines - United States of America. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/united-states-of-america/en/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA) Resolução - RDC No 331, de 23 de Dezembro de 2019, Que Dispõe Sobre Os Padrões Microbiológicos de Alimentos e Sua Aplicação.; Brasil, 2019; p. 1;

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA) Instrução Normativa No. 60, Que Estabelece as Listas de Padrões Microbiológicos Para Alimentos.; Brasil, 2019; p. 41;

- Asomaning, J.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Lewis, E.D.; Wu, J.; Jacobs, R.L.; Field, C.J.; Curtis, J.M. The Development of a Choline Rich Cereal Based Functional Food: Effect of Processing and Storage. LWT 2017, 75, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossa, M. de A.V.; Bilck, A.P.; Yamashita, F.; Mitterer-Daltoé, M.L. Biodegradable Packaging as a Suitable Protectant for the Conservation of Frozen Pacu ( Piaractus Mesopotamicus ) for 360 Days of Storage at −18°C. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, E. Lipid Oxidation That Is, and Is Not, Inhibited by Vitamin E: Consideration about Physiological Functions of Vitamin E. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2021, 176, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-H.; He, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, C.-H.; Jong, A. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG Suppresses Meningitic E. Coli K1 Penetration across Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells In Vitro and Protects Neonatal Rats against Experimental Hematogenous Meningitis. International Journal of Microbiology 2009, 2009, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Gil-Campos, M.; Gil, A. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics. Advances in Nutrition 2019, 10, S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak-Różańska, L.; Berthold-Pluta, A.; Pluta, A.S.; Dasiewicz, K.; Garbowska, M. Effect of Simulated Gastrointestinal Tract Conditions on Survivability of Probiotic Bacteria Present in Commercial Preparations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Haq, S.F.; Samant, S.; Sukumaran, S. Adaptation of Lactobacillus Acidophilus to Thermal Stress Yields a Thermotolerant Variant Which Also Exhibits Improved Survival at PH 2. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2018, 10, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Palencia, P.; López, P.; Corbí, A.L.; Peláez, C.; Requena, T. Probiotic Strains: Survival under Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions, in Vitro Adhesion to Caco-2 Cells and Effect on Cytokine Secretion. European Food Research and Technology 2008, 227, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, A.; Gänzle, M.G.; Wu, J. Cruciferin Improves Stress Resistance and Simulated Gastrointestinal Survival of Probiotic Limosilactobacillus Reuteri in the Model Encapsulation System. Food Hydrocolloids for Health 2023, 3, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño-Vásquez, I.A.; Muñiz-Márquez, D.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Co-Microencapsulation: A Promising Multi-Approach Technique for Enhancement of Functional Properties. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 5168–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Sarmiento, C.; Téllez-Medina, D.I.; Viveros-Contreras, R.; Cornejo-Mazón, M.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.Y.; García-Armenta, E.; Alamilla-Beltrán, L.; García, H.S.; Gutiérrez-López, G.F. Zeta Potential of Food Matrices. Food Engineering Reviews 2018, 10, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurckevicz, G.; Dahmer, D.; Q. Santos, V.A.; Vetvicka, V.; M. Barbosa-Dekker, A.; F. H. Dekker, R.; Maneck Malfatti, C.R.; A. da Cunha, M.A. Encapsulated Microparticles of (1→6)-β-d-Glucan Containing Extract of Baccharis Dracunculifolia: Production and Characterization. Molecules 2019, 24, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Giottonini, K.Y.; Rodríguez-Córdova, R.J.; Gutiérrez-Valenzuela, C.A.; Peñuñuri-Miranda, O.; Zavala-Rivera, P.; Guerrero-Germán, P.; Lucero-Acuña, A. PLGA Nanoparticle Preparations by Emulsification and Nanoprecipitation Techniques: Effects of Formulation Parameters. RSC Advances 2020, 10, 4218–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, L.; Almeida, A.; Gonçalves, L. Effect of Experimental Parameters on Alginate/Chitosan Microparticles for BCG Encapsulation. Marine Drugs 2016, 14, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Zuo, F. Effect of Particle Size on Physicochemical Properties and in Vitro Hypoglycemic Ability of Insoluble Dietary Fiber From Corn Bran. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Published article | Year | Journal Impact Factor (2023) | Citations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Health benefits of kimchi (Korean fermented vegetables) as a probiotic food [52] | 2014 | Journal of Medicinal Food (IF: 1.7) | 263 |

| 2nd | Significance of coarse cereals in health and nutrition: a review [53] | 2014 | Journal of Food Science and Technology-Mysore (IF: 3.1) | 160 |

| 3rd | Functional foods and dietary supplements for the management of dyslipidemia [54] | 2017 | Nature Reviews Endocrinology (IF: 31.0) | 146 |

| 4th | Traditional healthful fermented products of Japan [55] | 2008 | Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology (IF: 3.2) | 141 |

| 5th | Assessment on the fermentability of xylooligosaccharides from rice husks by probiotic bacteria [56] | 2008 | Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (IF: 5.7) | 125 |

| 6th | Protection of L. rhamnosus by spray-drying using two prebiotics colloids to enhance the viability [57] | 2014 | Carbohydrate Polymers (IF: 10.7) | 111 |

| 7th | Production of RS4 from rice starch and its utilization as an encapsulating agent for targeted delivery of probiotics [58] | 2018 | Food Chemistry (IF: 8.5) | 110 |

| 8th | The effect of a probiotic on fecal and liver lipid classes in rats [59] | 1995 | British Journal of Nutrition (IF: 3.0) | 101 |

| 9th | Potential use of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) in Brazil: Food security, processing, health benefits and nutritional products [60] | 2018 | Food Research International (IF: 7.0) | 97 |

| 10th | Role of probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum KKL1 in the preparation of a rice based fermented beverage [61] | 2015 | Bioresource Technology (IF: 9.7) | 83 |

| Proximal Composition* | ||||||||||||||

| Moisture at 105 ºC | 7.43 ± 0.068 | Total fats | 8.82 ± 0.21 | |||||||||||

| Carbohydrate | 25.56 ± 0.05 | Mineral residue | 9.41 ± 0.17 | |||||||||||

| Total protein | 48.78 ± 0.10 | Dietary fiber | 6.49 ± 0.52 | |||||||||||

| Calorifc value: 376,74 kcal 100g-1 or 1576.28 kj | ||||||||||||||

| Essential Amino Acids** | Non-essential amino acids** | |||||||||||||

| FAO/WHO*** | Aspartic Acid | 94.1 ± 1.18 | ||||||||||||

| Phenylalanine | 53.30 ± 2.67 | - | Glutamic Acid | 157.48 ± 1.33 | ||||||||||

| Histidine | 21.53 ± 0,55 | 15.0 | Alanine | 47.56 ± 0.59 | ||||||||||

| Isoleucine | 46.74 ± 1.17 | 30.0 | Arginine | 74.83 ± 0.94 | ||||||||||

| Leucine | 79.54 ± 1.09 | 59.0 | Cystine | 13.94 ± 0.18 | ||||||||||

| Lysine | 47.15 ± 1.18 | 45.0 | Glycine | 39.36 ± 0.49 | ||||||||||

| Methionine | 15.38 ± 0.38 | - | Hydroxy proline | 0.41 ± 0.05 | ||||||||||

| Threonine | 35.67 ± 0.89 | 23.0 | Proline | 42.03 ± 0.52 | ||||||||||

| Tryptophan | 5.76 ± 0.07 | 6.0 | Serine | 45.31 ± 0.23 | ||||||||||

| Valine | 55.97 ± 1.33 | 39.0 | Tyrosine | 39.77 ± 0.50 | ||||||||||

| Sulfur-containing Amino Acids | Aromatic Amino Acids | |||||||||||||

| FAO/WHO** | FAO/WHO** | |||||||||||||

| Methionine + Cystine: 28.91 ± 0.36 | 22.0 | Phenylalanine + Tyrosine: 93.07 ±1.16 | 38.0 | |||||||||||

| Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MFA)* | ||||||||||||||

| Capric Acid C16: 1n7 (ω-7) |

0.46 | Oleic Acid C18:1n9c (ω-9) |

1.18 | |||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PFA)* | ||||||||||||||

| Linoleic Acid C18:2n6c (ω-6) |

1.420 | α-Linolenic Acid C18:3n3 (ω-3) |

0.150 | |||||||||||

| Minerals# | ||||||||||||||

| DRI& | DRI& | |||||||||||||

| Sodium (Na) | 530.0 | 2000.0 | Zinc (Zn) | 6244.0 | 11.0 | |||||||||

| Calcium (Ca) | 200.0 | 1000.0 | Phosphorus (P) | 390.0 | 700.0 | |||||||||

| Iron (Fe) | 10.0 | 14.0 | Magnesium (Mg) | 70.0 | 420.0 | |||||||||

| Selenium (Se) | 0.06 | 60.0 | ||||||||||||

| Total Lipids* | ||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 1.64 | Unsaturated | 2.79 | |||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 1.57 | Saturated | 3.24 | |||||||||||

| Microorganism | Brazilian standards* (CFU g-1) | Results (CFU g-1) |

| Salmonella spp. | Absence in 25 g | Absence in 25 g |

| Thermotolerant coliforms (at 45 ºC) | 5.0 x 103 | < 1.0 x 101 |

| Total coliforms (at 35 ºC) | 1.0 x 101 | < 1.0 x 101 |

| Coagulase-positive Staphylococcus | 1.0 x 102 | < 1.0 x 101 |

| Bacillus cereus | 5.0 x 102 | < 3.0 x 102 |

| Mold and yeast | 1.0 x 103 | < 1.0 x 101 |

| ABTS (mM Trolox equivalent g-1) | ||

| Storage period (days) |

Storage temperature | |

| 25 ºC | - 18ºC | |

| 0 | 86.53 ±0.31a | 86.53 ±0.31a |

| 30 | 56.96 ±0.72b | 56.22 ±0.37b |

| 60 | 37.93 ±0.79c | 40.27 ±0.09c |

| 90 | 35.58 ±0.73d | 39.52 ±1.05c |

| DPPH (mM Trolox equivalent g-1) | ||

| Storage period (days) |

Storage temperature | |

| 25 ºC | - 18ºC | |

| 0 | 7.60 ±0.06a | 7.60 ±0.06a |

| 30 | 6.80 ±0.09b | 7.24 ±0.02b |

| 60 | 6.50 ±0.06c | 6.73 ±0.10c |

| 90 | 6.41 ±0.01c | 6.71 ±0.09c |

| FRAP (mM Fe+2 g-1) | ||

| Storage period (days) |

Storage temperature | |

| 25 ºC | - 18ºC | |

| 0 | 24.96 ±0.54a | 24.96 ±0.54a |

| 30 | 21.21 ±0.31b | 22.74 ±0.20b |

| 60 | 20.94 ±0.18b | 22.34 ±0.70b |

| 90 | 19.29 ±0.57c | 21.75 ±0.26b |

| TBARS (mg MDA kg-1) | ||

| Storage period (days) |

Storage temperature | |

| 25 ºC | - 18ºC | |

| 0 | 2.54 ±0.23d | 2.52 ±0.21c |

| 30 | 2.96 ±0.12b | 2.93 ±0.11b |

| 60 | 3.44 ±0.11a | 3.48 ±0.10a |

| 90 | 3.48 ±0.11a | 3.45 ±0.10a |

| Time (minutes) |

Temperature (°C) |

Probiotic cells (log CFU mL-1) |

Reduction in cell viability (%) |

| 0 | 25 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | - |

| 1 | 55 | 6.7 ± 0.3 | 22.04 |

| 1 | 65 | 5.87 ± 0.3 | 31.72 |

| 1 | 75 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 93.55 |

| 10 | 55 | 1.92 ± 0.0 | 77.69 |

| 10 | 65 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 92.47 |

| 10 | 75 | 0 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).