1. The Function of the Endothelium

The endothelium is a monolayer of cobblestone-shaped cells that covers the inner wall of blood vessels. It is a crucial regulator of vascular homeostasis that acts as a barrier between the blood and blood vessels and serves as a signaling activator that modifies the phenotype of the endothelial wall through changes in permeability, inflammation, vascular tone, and injury repair [

1]. The endothelium is <0.2 µm thick and weighs approximately 1kg in an average-sized human, covering a total surface area of 4000 to 7000 m

2 [

2].

1.1. Endothelial Glycocalyx

The endothelium contains a glycocalyx, which is a complex gel between flowing blood and the endothelial wall [

3]. Its composition and dimensions fluctuate as it continuously replaces material sheared by flowing plasma [

4]. Primarily, the endothelial glycocalyx (EG) is composed of proteoglycans (PGs), glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and glycoproteins (GPs). These result in a negative charge, which acts as a physical barrier that prevents direct contact between cells and molecules on the endothelial surface [

5]. PGs are key components of the EG, consisting of a core protein attached to GAG chains. The two main types of PGs in the EG are syndecans and glypicans [

6].

Syndecans are transmembrane proteins present on the surface of most cells in the body. There are four known syndecans in vertebrates, but the EG primarily contains syndecan-1 (SDC1), featuring extracellular, transmembrane, and cytosolic domains [

7], which allow them to bind GAGs and respond to external signals like shear stress, which are transduced into the intracellular environment [

8]. On the other hand, glypicans are not transmembrane proteins; nevertheless, they are attached to the luminal membrane of endothelial cells by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor [

9]. There are six known glyplicans in mammals, with glyplican-1 being the only one expressed in the endothelium that specifically binds to GAGs [

10]. Its ectodomain specifically binds to GAG heparan sulfate, and its anchor molecule is believed to be positioned near lipid rafts and caveolae. Caveolae are membrane structures abundant in signaling molecules that act as communication centers in the cell membrane. This positioning enables glypicans to engage in various signaling pathways with cytokines and other substances, including the vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) [

8]).

For their part, GAGs are linear polysaccharides that do not branch, consisting of 20 to 200 repeating disaccharide units. They represent the most abundant component of the extracellular matrix (ECM) [

7]. The five primary types of GAGs are heparan sulfate (HS), chondroitin sulfate (CS), dermatan sulfate (DS), keratan sulfate, and hyaluronan (HA). While all five GAGs are found in the ECM, they are not evenly distributed. HS is the most abundant, accounting for 50–90% and appearing in a 4:1 ratio with CS, the second most common GAG [

11].

The biosynthesis of the core proteins syndecan and glypican occurs on ribosomes attached to the membrane. After synthesis, the core protein is moved into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum then to the Golgi apparatus, where GAG side chains are attached, polymerized, and sulfated. The core protein, along with the GAGs, is subsequently transported to the cell surface, where it is either integrated into the cell membrane, as seen with syndecans, or linked to the surface via an anchor molecule, such as in the case of glypican. Unlike other GAGs, HA is synthesized directly on the cell membrane and does not attach to a core protein [

12].

Finally, GP is situated on the surface of endothelial cells and is covered by the extracellular glycocalyx in healthy conditions. In contrast to PGs, GPs do not interact with long-chain GAGs; instead, they feature short, branched oligosaccharide units that are covalently bonded [

13]. Endothelial GPs function as membrane-bound cell adhesion molecules and are classified into three families based on their structural and functional attributes: selectins, immunoglobulins, and integrins [

14]. Integrins facilitate the interaction between platelets and endothelial cells (ECs) by binding to collagen and laminin in the subendothelial matrix [

15]. Immunoglobulins, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and -2 (ICAM-1,-2), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, primarily mediate inflammatory cell adhesion to the endothelium by binding to the target cell’s integrins [

16].

These GPs are vital for the proper recruitment of leukocytes, which involves a sequence of regulated steps: rolling, adhesion, and transmigration. This process allows neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, and some lymphocytes to move through the endothelium by binding to their respective integrins [

17].

The key selectins in the extracellular glycocalyx are P-selectin and E-selectin. Both are important for the initial adhesion of leukocytes and platelets to activated ECs [

14]. E-selectin is exclusively found on the endothelium and binds to interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor-α, or lipopolysaccharides; meanwhile, P-selectin is present on both ECs and platelets and binds to histamine or thrombin. However, unlike P-selectin, which is stored, E-selectin is inducible and requires transcription, translation, and movement to the cell surface for its function [

18]).

The functions of these proteins, in addition to providing a negative charge to repel molecules, also include regulating vascular permeability, hemostasis, blood viscosity, and the inflammatory response [

19]. The glycocalyx itself is physiologically inert; however, the addition of both plasma-derived and endothelial-derived soluble factors makes it physiologically active. The interaction between ECs and coagulation factors, plasma molecules, and inflammatory cells through various adhesion molecules within the glycocalyx is essential for the proper functioning of hemostasis, blood viscosity, and inflammatory responses [

13].

1.2. Endothelial Functions

In healthy blood vessels, the interaction between ECs and blood will not induce platelet adherence and clot formation, as this is an active process. Platelets circulate in a quiescent state throughout the vascular system until required. As a result, ECs create a protective anticoagulant and antithrombogenic layer, actively producing substances that modulate platelet behavior [

20]. One key substance is NO, which ECs continuously synthesize from L-arginine using the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in its membrane-bound form [

21]. NO can easily diffuse across cell membranes and enter nearby platelets, activating guanylate cyclase (GC). This activation transforms guanosine triphosphate (GTP) into cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). The increase in cGMP results in vasodilatation, which interferes with the release of stored intracellular calcium (Ca²+). This suppression reduces platelet activation and aggregation [

22], inhibiting the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth cells, preventing leukocyte adhesion, and limiting oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria [

5].

Various metabolic changes may disrupt the delicate balance of endothelial mediators, leading to endothelial dysfunction (ED); this condition can be defined as an imbalance in the bioavailability of active substances originating from the endothelium. This leads to a predisposition to inflammation, increased vascular permeability, and can facilitate the development of arteriosclerosis, platelet aggregation, and thrombosis [

23]. Conditions such as hyperglycemia and insulin resistance initiate molecular interactions that compromise endothelial function. These interactions lead to increased vascular tone, enhanced vascular permeability, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses, resulting in greater arterial stiffness, impaired vascular remodeling, endothelial activation, and, ultimately, the development of atherosclerosis [

24].

Key physiological features for ED include the reduced availability of endothelial NO, decreased endothelium-mediated vasodilation, dysregulation of hemodynamics, impaired fibrinolytic activity, increased expression of adhesion molecules and inflammatory genes, heightened oxidative stress, and greater endothelial permeability [

25].

2. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Endothelial Dysfunction

2.1. MASLD Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Some years ago, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) became the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide; it now currently affects 38% of the adult population [

26]. This disorder is expected to become the leading cause of liver transplantation worldwide by 2030 [

27]. The prevalence of NAFLD is expected to rise over the next decade, paralleling the global epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus [

28]. Significant progress has been made in the past 10 years in understanding the complex pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this widespread liver condition. NAFLD has been recognized as a multisystem disease where insulin resistance and associated metabolic dysfunction contribute to its development and serious liver-related complications, including cirrhosis, liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, and extrahepatic issues such as cardiovascular disease [

29].

Later, in 2020, international experts proposed a change in terminology for NAFLD to metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) [

30]. However, in 2023, three multinational liver associations proposed renaming it again, this time from MAFLD to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [

31] to emphasize the disease as an independent entity without exclusion criteria, highlighting that MASLD can coexist with other chronic liver diseases [

30]. MASLD is defined by metabolic dysfunction as its foundation, underlining its significant impact on disease and its reduced heterogeneity. Key criteria include being overweight or obese and having type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [

32]. In this context, chronic inflammation plays a central role and is marked by the accumulation of bioactive lipids, lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and the secretion of proinflammatory molecules [

33]. This diagnosis is evaluated via either imaging or liver biopsy in patients presenting one of the following five cardiovascular risk factors: arterial hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, low plasma HDL cholesterol, increased body mass index (BMI) or waist circumference, and increased fasting serum glucose levels. Other causes of chronic liver disease like viral hepatitis or excessive alcohol consumption (>30 or 20g per day for men and women, respectively) are absent [

34]. The most common exogenic trigger of MASLD is overnutrition, expanding adipose tissues, and driving ectopic fat deposits, which cause changes in tissue metabolism and dysregulation

, for example, insulin resistance in hepatocytes [

35].

The accumulation of fat is considered an early step in the origin of the disease [

36]. With dietary constituents acting as pivotal drivers of the disorder, the overconsumption of nutrients crucially involves weight gain, disruption of the gut microbiome, and metabolic dysregulation as early steps and risk factors of MASLD [

37]. The increased consumption of sugars, especially fructose, which is added as a sweetener to beverages and processed foods [

38], induces lipogenesis in hepatocytes and fatty acid synthesis. This occurs by providing essential substrates and regulating the expression of key enzymes involved in lipid metabolism via the transcription factors sterol response element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1) and carbohydrate-responsive element binding protein (ChREBP) [

39]. The accumulation of lipids, predominantly triglycerides, impairs fatty acid oxidation. Altered lipid export from the liver will initiate a series of harmful effects known as lipotoxicity, which fuels inflammatory processes and the progression of MASLD [

40]. Hepatic free cholesterol interacts with a transcriptional regulator that induces cell proliferation and reprogramming called yes-associated protein (YAP) and the transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), also known as YAP-TAZ. Through interaction with YAP-TAZ, free cholesterol will facilitate the lipotoxic effects of this transcriptional regulator, promoting tissue inflammation [

41].

2.2. The Participation of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in MASLD

As previously mentioned, the vascular endothelium participates in multiple physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms, such as vascular tone, inflammation, and platelet function, among others [

42]. Nonetheless, there is a specialized and phenotypically differentiated endothelium with a distinctive anatomical location and structure called liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) [

43]. LSECs represent 20% of the total number of hepatic cells from the non-parenchymal group of cells placed in an interface between the hepatic parenchyma and the blood from the hepatic artery and portal vein [

44]. In response to liver injury, LSECs respond by regenerating and balancing fibrosis through the secretion of angiocrine factors [

45]. In chronic liver diseases, such as MASLD, LSECs undergo a process known as capillarization, where the fenestrae disappear, leading to the formation of a continuous endothelial layer, which is a common indicator of chronic liver disease and is hypothesized to be the first stage in liver fibrosis [

46]. In addition, it can directly contribute to increased hepatic vascular resistance through the enhanced activation of the cyclooxygenase-1-thromboxane vasoconstrictor pathway [

47].

2.3. The Relationship Between Endothelial Dysfunction and MASLD

Capillarization commonly coexists with cardiovascular risk factors, such as dyslipidemia, obesity, and T2DM, all of which are related to the presence of insulin resistance (IR) [

24]. Thus, the underlying pathology in cardiovascular disease is ED [

48]; this process also involves several key cellular mechanisms. Initially, under typical conditions, human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) remain quiescent [

49]. However, chronic inflammation can activate these cells, leading to the excessive production of collagen type 1, which contributes to liver damage [

14,

50]. As HSCs become activated and contribute to liver damage, LSECs act as a barrier that separates hepatocytes and the space of Disse from the sinusoidal lumen. Moreover, they play an important role in delivering nutrients to hepatocytes and removing waste products from the sinusoidal lumen and bloodstream [

52].

Clinical evidence has proposed that there is a synergistic effect between fatty liver and overweight conditions in the development of ischemic heart disease [

48,

53]. This is characterized by endothelial injury, which leads to dysfunction and serves as the initiating event in atherosclerosis. This dysfunction plays an important role in the ischemic manifestations associated with coronary disease [

54]. ED in MASLD can result from IR, which disrupts multiple pathways involving the stimulation of NO production from the endothelium, leading to vasodilation and increased blood. This ultimately causes damage to the vascular endothelium and atherosclerosis. Also, the secretion of endothelin-1 which serves as a vasoconstrictor, is a key factor contributing to both IR and ED [

55]. Indeed, ED is commonly observed in patients with conventional cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, and smoking; it is significantly correlated with the development and progression of atherosclerosis [

56].

According to clinical studies, a meta-analysis involving 34,043 patients reported that patients with MASLD have a 64% higher risk of developing major cardiovascular events compared to patients without MASLD [

57]. Since the protective effects of the endothelium may be lost, this leads to a negative prognosis for patients with cardiovascular disease [

58].

An inverse mechanism has also been suggested, where pre-existing ED may contribute to MASLD due to reduced NO availability leading to the activation of HSCs [

59]; however, the exact cellular and molecular mechanism is still unknown. Moreover, although various non-invasive methods have been used to detect hepatic fatty infiltration, liver biopsy is still considered the gold standard for diagnosing MASLD [

60]. The search for several targets with potential diagnostic and therapeutic effects has been extensive, as nuclear receptors are considered eminent regulators of energy metabolism and inflammation in several pathologies.

3. Nuclear receptors: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are a family of transcription factors that belong to the superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors and consist of three isoforms: PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ [

61]. These receptors significantly influence the gut–liver–adipose axis, upregulating β-oxidation and cholesterol elimination.

PPARα is expressed in tissues with a high rate of acid oxidation—predominantly the liver, skeletal muscle, heart, and brown adipose tissue—with the main function of managing energy metabolism based on nutritional conditions such as fasting and feeding [

62]. Notably, in the liver, its expression has also been documented in sinusoidal endothelial cells at a lower level in mice and HSCs [

63]. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that oleoylethanolamide, an endocannabinoid-like molecule, attenuates the progress of liver fibrosis by blocking HSC activation through PPARα activation [

64]. Moreover, hepatic fibrosis caused by arsenic trioxide induces the activation of HSCs through PPARα activation and autophagy, where taurine supplementation alleviates this response [

65].

Saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, eicosanoids, and leukotriene B4 are primary endogenous ligands for PPARα. The fatty acid derivative, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine, has been recognized as an endogenous ligand for PPARα, which plays a protective role against hepatic steatosis [

66]. The role of PPARα in the liver can be understood through both short-term and long-term regulatory functions; in the short term, it initiates early under fasting conditions to facilitate free fatty acid oxidation for cellular energy requirements; meanwhile, in the long term, it addresses excessive oxidation and the increased production of ketone bodies by regulating lipoprotein and lipogenesis metabolism through PPARα itself and its ligands. The metabolic pathway depends on the free fatty acid levels in the liver [

67].

On the other hand, PPARβ/δ is found in skeletal muscle and has been widely studied both in vivo and in vitro. It acts as a major regulator of glucose metabolism and a promoter of lipid uptake as an energy source for ATP production during fasting and exercise through the mitochondrial β-oxidation pathway [

68]. Also, PPARβ/δ influences plasma lipid levels by regulating fatty acid oxidation and overseeing the handling of glucose in the muscle and liver. Saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, 15-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, and components of VLDL are endogenous ligands for PPARβ/δ [

69]. One of the functions of PPARβ/δ is angiogenesis; it regulates both physiologically and pathological angiogenesis, where PPARβ/δ encodes angioprotein-like 4 (ANGPTL4), a secretory protein that participates in angiogenesis, cancer progression, and metastasis [

70]. When PPARβ/δ is activated by natural ligands, such as prostacyclin I2, or exogenous synthetic ligands like GW501516, it induces EC proliferation and angiogenesis, inhibits EC apoptosis, and stimulates the proliferation of human breast and prostate cancer cell lines [

71].

Meanwhile, regarding PPARγ, PPARγ1 is expressed in a variety of cells, including immune cells and brain cells, while PPARγ2 is specifically abundant in brown and white adipose tissue, regulating adipocyte differentiation and lipid metabolism [

72]. Unsaturated fatty acids, prostaglandin J2, and multiple metabolites serve as endogenous ligands for PPARγ [

73]. Specifically in the liver, PPARγ promotes the fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) mediated by free fatty acid (FFA) uptake, which increases the expression of fatty acid synthase and enhances triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes [

74]. Also, PPARγ increases the transcription of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), which activates other adipogenic genes and converts pyruvate to fatty acids [

75].

Among these isoforms, PPARα could be considered the main key regulator of lipid metabolism. It governs a range of processes, including numerous genes involved in fatty acid uptake and activation, mitochondrial and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation, ketogenesis, lipid droplet biology, and triglyceride turnover. Additionally, it plays a role in glucose metabolism, homeostasis, and managing glycerol for gluconeogenesis [

76]. These receptors have pleiotropic actions that make them critical regulators not only in glucose and fatty acid metabolism but also in inflammation and fibrogenesis [

77]. Due to these effects, dual PPARα/δ agonists have been used, demonstrating potent impacts on IR, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia in patients with obesity, which will be discussed later.

The clinical efficacy and development of selective PPARβ/δ have been insufficiently researched. Current evidence suggests that the activation of PPARβ/δ may have oncogenic potential, raising concerns about the clinical development and safety of PPARβ/δ agonists. Two phase II trials were initiated to investigate the effects of GW677954 in patients with diabetes; however, due to the carcinogenicity of the drugs in animal studies, the trials were prematurely terminated, leading to the discontinuation of the development of PPARβ/δ agonists [

78].

In terms of PPARγ, it has been demonstrated that uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) transcription is induced through catecholamine-induced cAMP signaling and PPARγ activation in brown/beige adipocytes, thus demonstrating its role in lipid metabolism [

79]. In general, the use of PPARγ agonists over type 2 diabetes has been one of the earliest applications built upon the discovery and knowledge of PPARγ with clinical evidence as an antidiabetic agent, with approved experimental agonists including pioglitazone, rosiglitazone, and rivoglitazone [

80].

3.1. PPARs and Inflammation

All PPARs are crucial regulators of inflammation, with existing evidence demonstrating that PPARα plays a key role in controlling hepatic inflammation [

81]. One of the main anti-inflammatory mechanisms of PPARα is the downregulation of acute-phase genes, including IL-1 receptor agonists (IL-Ra) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) inhibitors [

82]. PPARα primarily regulates inflammation through the transrepression mechanism, binding to NF-kB components and thereby suppressing their transcriptional activity. A study conducted by Pawlak et al. revealed that mice with a mutation in the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of PPARα, which limits its transcriptional activity to transrepression, are protected from liver inflammation and do not develop liver fibrosis in a dietary-induced metabolic-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) model [

83]. Additionally, PPARα modulates the duration of inflammation by regulating the catabolism of its ligand leukotriene B4, a chemotactic agent involved in the inflammatory response [

84].

In relation to the anti-inflammatory effects of PPARβ/δ, it plays a role in regulating the activation of Kupffer cells (KCs). In the presence of IL-4 and IL-13 stimulation, PPARβ/δ is essential for activating these cells into the macrophage type 2 subtype, which exhibits anti-inflammatory activity. Also, it is involved in HSC activation through a signal-transducing factor, leading to HSC proliferation in an acute and chronic liver inflammation event and the expression of CD36, which codes for a membrane receptor that facilitates fatty acid uptake [

85]. PPARβ/δ conduces mono-unsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) production by stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (Scd1) upregulation. This process will avoid lipotoxicity by increasing fatty acid oxidation, inhibiting fatty acid-induced cytotoxicity in hepatocytes [

86]. Furthermore, anti-apoptotic effects have been shown in a hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury model through the inhibition of the NF-κβ pathway in hepatocytes and KCs [

87].

On the other hand, PPARγ is considered a potent anti-inflammatory agent. It participates in inflammatory signaling by interacting with inflammatory transcription factors, such as NF-κβ, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), and AP-1; with this activation, it reduces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [

74]. In addition to PPARβ/δ, PPARγ can induce macrophage type 2 polarization [

88] and inhibit genes encoding inflammatory molecules while activating the expression of anti-inflammatory mediators to promote anti-inflammatory effects [

89].

PPARα and γ are beneficial in medical conditions where inflammation is a major driving force of disease exacerbation, such as MASH [

78]. Furthermore, PPARγ’s anti-inflammatory role has been demonstrated in several diseases. For example, it acts as a protector against renal inflammation [

90]; in neuronal intoxication with the aid of a neuroprotective flavonoid, diosmin, which has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects mediated through PPARγ upregulation [

91]; and in chronic inflammation diseases such as atherosclerosis through monocyte inflammation modulation [

92].

3.2. PPARs and Endothelium

All three PPAR subtypes can promote eNOS activation. For example, fibrates boost nitric oxide synthesis by increasing eNOS expression, stabilizing its mRNA, and activating eNOS through the PI3K, MAPK, and AMPK pathways [

93]. PPAR β/δ and PPARγ also play a role in modulating eNOS activity via the PI3K-Akt pathway [

94]. The enhancement of eNOS activation and stability via PPARγ is also supported by various intermediates, including heat shock protein 90, adiponectin, and Src homology region 2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 [

95]. Collectively, the influence of PPARs on eNOS and nitric oxide production provides a foundation for using PPAR agonists in clinical settings for cardiovascular disease and hypertension (

Figure 1).

LSECs communicate closely with HSCs through NO synthesis to regulate intrahepatic blood and subsequently induce vasodilation. In chronic liver diseases, LSECs lose their specialized phenotype, and their ability to produce NO decreases; meanwhile, HSCs reduce their sensitivity, leading to microvascular dysfunction. All of these events promote intrahepatic vascular liver resistance, which results in portal hypertension development [

96]. Furthermore, factors secreted by HSCs influence phenotypic LSEC alterations. These changes in LSECs occur in the early stages of the development of MASLD, often preceding the activation of KCs and HSCs [

97].

It has been seen that PPAR agonists may prevent the recruitment and activation of immune cells and confer a vasoprotective phenotype to endothelial cells [

96]. It has been reported that PPARα and LSECs also help keep HSCs quiescent through extracellular vesicle secretion [

50,

51]. PPARγ is essential in preventing endothelial dysfunction associated with aging [

98], as impaired endothelial PPARγ causes age-related vascular dysfunction [

99].

PPARγ activation can contribute to regulating endothelial activation, NO activity, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. To improve endothelial dysfunction, PPARα and PPARγ activation suppresses activator protein-1 (AP-1), which is responsible for increasing the expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in endothelial cells [

100]. By inhibiting AP-1, PPARs can decrease the expression of endothelin-1 [

101], a powerful vasoconstrictor peptide released by endothelial cells with a proinflammatory effect. This affects cell proliferation and migration due to the activation of PPARα; as a result, endothelin-1 secretion is reduced, decreasing the release of adhesion molecules and reducing monocyte chemotaxis [

102].

PPARα receptors can also be activated by a variety of natural and synthetic ligands, including fibrates [

103]. The beneficial impact of fenofibrate on vascular function might be partly attributed to enhanced endothelial NO availability since PPARα activation has been shown to increase NO production in endothelial cells [

93].

PPARs have been identified as playing an important role in lipid and glucose metabolism and being key regulators in metabolic diseases, inflammation, and fibrosis [

74]; as a result, they may be a promising pharmacological target in MASLD. In this respect, it is important to mention that the crosstalk between the different PPAR isotypes has been poorly reported. Wahli et al. proposed that the presence of compensatory mechanisms between PPAR isotypes may be an important issue to consider when PPAR agonists are tested. Furthermore, although all three PPAR isotypes are involved in lipid and glucose metabolism, PPARα is considered the master regulator of hepatic lipid catabolism. PPARγ promotes IR, while PPARβ/δ’s role is still unclear; however, it is well known to promote hepatic glucose and fatty acid synthesis [

104].

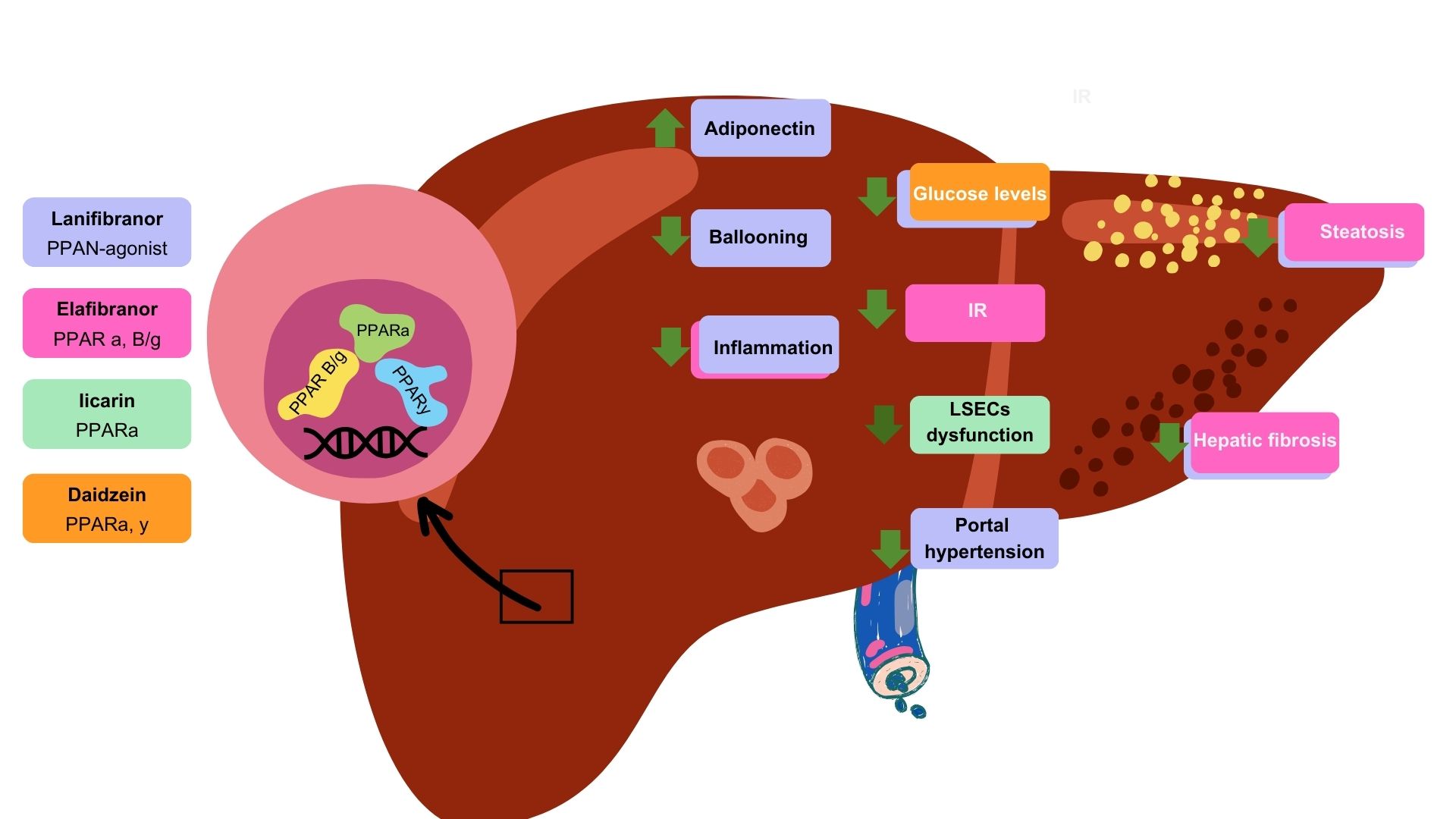

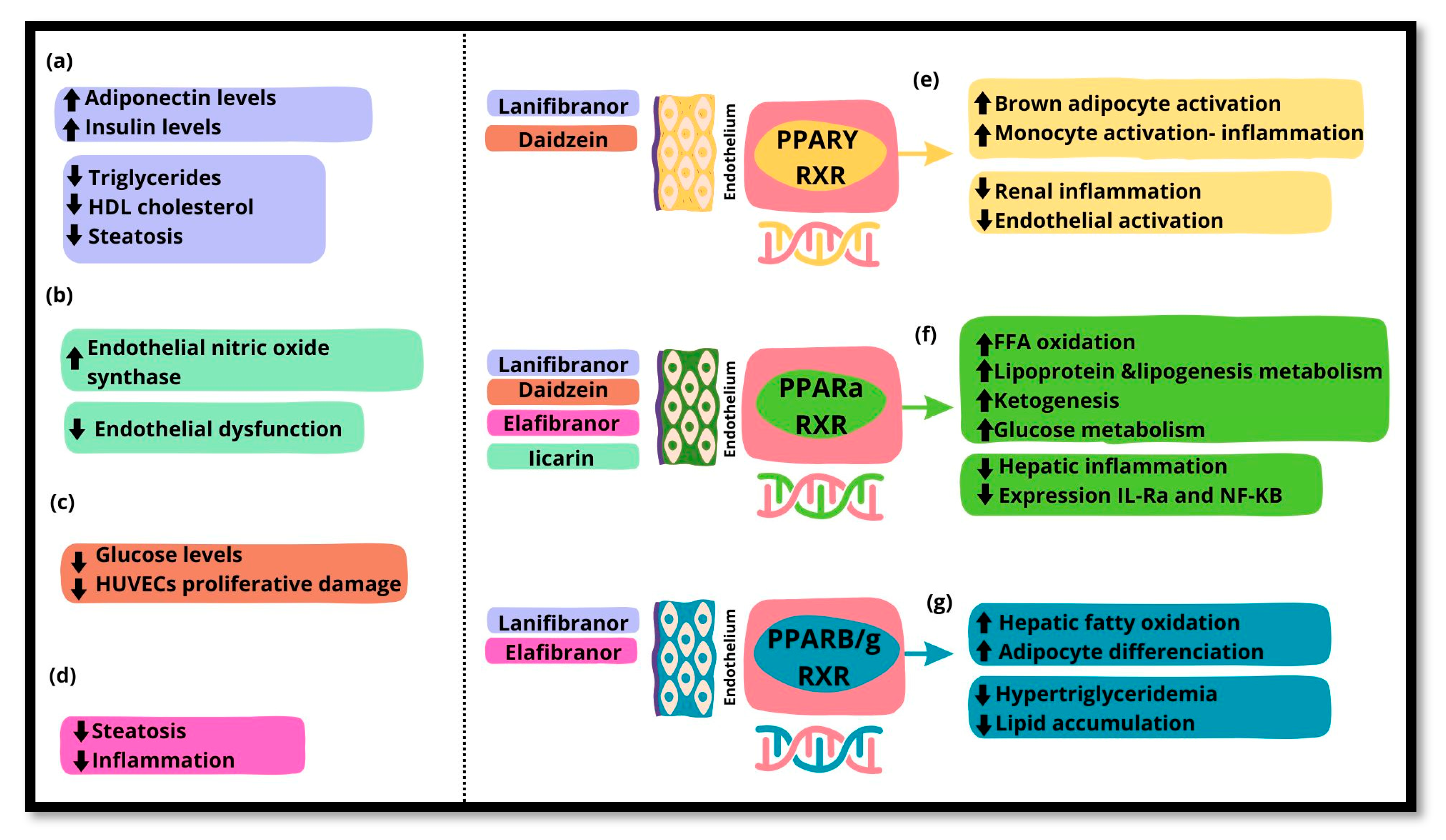

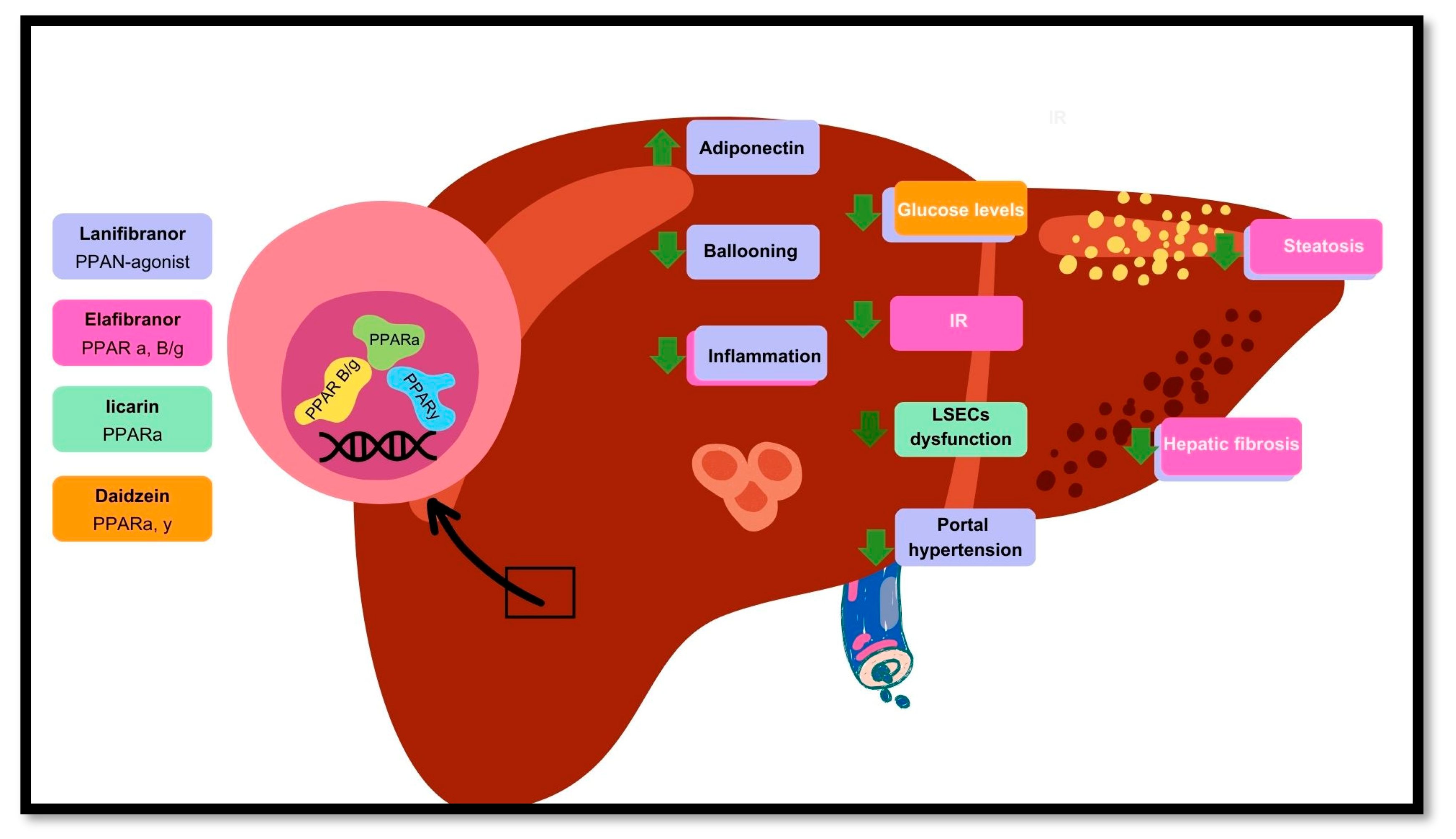

Several PPAR agonists are used as pharmacological targets. The main biological actions of lanifibranor are the improvement in triglycerides, HDL cholesterol levels, and steatosis in addition to the increase in adiponectin and insulin levels (a). Icariin, a PPARα agonist, promotes endothelial nitric oxide synthase and improves endothelial dysfunction (b). Daidzein, a PPARα and PPARγ agonist, contributes to reducing high glucose levels and ameliorating proliferative damage in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (c). Elafibranor, a PPARα and PPARβ/δ agonist, improves steatosis and inflammation (d). The biological effects of PPAR isotypes are as follows: PPARγ is responsible for the activation of brown adipose tissue and monocytes in response to inflammation, contrary to the prevention of renal inflammation and endothelial activation (e). PPARα is principally involved in various liver functions, such as the promotion of free fatty acid oxidation, lipogenesis, and glucose metabolism, but it decreases inflammation and the expression of IL-1 receptor agonists (IL-Ra) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) (f). PPARβ/δ promotes the increase in hepatic fatty acid oxidation and adipocyte differentiation while reducing hypertriglyceridemia and lipid accumulation (g).

4. PPARs as Pharmacological Targets

The significant role of PPAR and other PPAR isoforms underscores the potential of PPARs as pharmacological targets in MASLD (

Table 1). Targeting all three PPAR isoforms to address the full spectrum of MASLD, ranging from insulin resistance to liver fibrosis, holds promise [

105]. One approach has been demonstrated in Phase II clinical trials by Francque et al. using the pan-PPAR agonist

lanifibranor, which has shown potential in improving both metabolic and hepatic health in MASLD via significant improvements in triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, insulin levels, and steatosis, regardless of the diabetes status of the patient [

106]. A more recent research study by Cooreman et al. focused on improving cardiometabolic health in patients with MASH. In the original analysis, hepatic steatosis was assessed using both imaging and histological analysis for all patients. The improvement in liver histological endpoints included the resolution of MASH, which was defined as a ballooning grade of 0 and lobular inflammation <1. Additionally, imaging was performed using elastography with a Fibroscan device to ensure that there was no worsening of fibrosis. Also, with the improvement in portal hypertension, most individuals with prediabetes, defined as fasting glucose levels between 5.6 and 6.9 mmol (100 to 125 mg/dl), achieved normal glucose levels (70 to 90 mg/dl). Additionally, there was a significant improvement in cardiometabolic markers, which include adiponectin levels, lipid profile, glycemic control, blood pressure, and systemic inflammation, associated with an improvement in hepatic and cardiovascular metabolic health. The patients experienced an average weight gain of 2.5 kg; however, it was observed that the increase was related to diet failure and that 51% of patients had stable weight. Furthermore, the therapeutic benefits were noted irrespective of weight changes. These findings indicate that the effect of

lanifibranor in MASH is also linked to improved cardiovascular health [

107].

According to a study by Yao et al., the activation of PPARα enhanced vascular endothelial function by decreasing endoplasmic reticulum stress and stimulating endothelial NO synthase in a murine model with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Their study suggested that a flavonoid glycoside known as

icariin could achieve these effects by normalizing endoplasmic reticulum stress and regulating the PPARα/Sirt1/AMPKα pathway [

108].

One drug studied for its wide range of health benefits is

daidzein, a primary isoflavone. Das et al. reported that

daidzein had a positive effect on T2DM-related dyslipidemia and vascular inflammation [

109]. In 2024, Yang et al. also explored the efficacy of

daidzein against high levels of glucose in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, demonstrating that

daidzein could ameliorate the proliferative damage in human umbilical vein endothelial cells induced by high glucose levels. This was mediated by the activation of PPARα and PPARγ, suggesting that they might act as dual agonists [

110].

Furthermore, a Phase III clinical trial for MASLD treatment is underway, focusing on a dual agonist of PPARα and β/δ called

elafibranor. This study investigates its effects in mice fed a choline-deficient high-fat diet characterized by obesity and insulin resistance. An improvement in liver steatosis, inflammation, and fibrogenesis has been demonstrated in this mice model, associated with the following: a decrease in alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and collagen type I alpha 1 (COL1A1) expression; elevated levels of epithelial–mesenchymal transition [EMT)-promoting protein calcium-binding protein A4 (S100A4). These changes are linked to PPARβ/δ activation and decreased cytokine signaling box containing protein 2 (ASB2) levels. This is a protein that regulates the degradation of S100A4 [

111]. (

Figure 2,

Table 1).

Through PPAR agonist drugs, there are different beneficial actions at the liver level for MASLD pathology. Lanifibranor, a PPAR agonist, reduces glucose levels and steatosis and improves portal hypertension and fibrosis; additionally, it increases adiponectin levels, which reduces hepatocyte ballooning and, consequently, inflammation. Elafibranor is a PPAR α-β/γ agonist that decreases inflammation and insulin resistance (IR), which synchronously slows down steatosis and fibrosis progression. Licarin, a PPARα agonist, reduces endothelial dysfunction, thereby affecting liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs). Finally, Daidzein, a PPARα,γ agonist, promotes decreased levels of glucose.

5. Discussion

Endothelial activation in MASLD involves the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules; this activation shifts the endothelial cells from a quiescent to an active state, promoting inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.

PPARs are pivotal in modulating inflammation, particularly within the hepatic context. Specifically, PPARα exerts significant control over hepatic inflammation since it is predominantly abundant in the liver. The anti-inflammatory mechanisms include downregulating acute-phase genes, including IL-Ra and NF-kB inhibitors, through transrepression, which in turn inhibits their transcriptional activity. This regulatory action is crucial for maintaining hepatic homeostasis. Notably, murine model research has demonstrated the DNA-binding domain mutations present in PPARα that limit its transcriptional activity and exhibit protection against liver inflammation and progression to fibrosis. This suggests that PPARα is capable of controlling both the initiation and resolution of hepatic inflammation. Furthermore, the activation of PPARα by synthetic fibrates has been shown to have a beneficial impact on vascular function. For instance, fenofibrate, a PPARα agonist, enhances endothelial NO availability, which is crucial for vascular health. This effect underscores the potential therapeutic effects of PPARα activation in managing the endothelial dysfunction associated with MASLD.

Regarding PPARβ/δ, evidence suggests that it has an influence on lipid and fatty acid regulation and glucose metabolism. The study of PPARβ/δ agonists demonstrates their role in obesity and IR diseases, such as hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury through NF-κβ pathway inhibition, lipid adipocyte accumulation, and diabetic osteoporosis.

Meanwhile, PPARγ plays a role in regulating endothelial activation through the modulation of NO activity, oxidative stress, and apoptosis by suppressing AP-1. PPARγ reduces the expression of VCAM-1, thereby mitigating endothelial activation. Additionally, PPARα and PPARγ activation suppresses endothelin-1, reducing chemotaxis and improving vascular function.

The significant role of PPARα, along with other PPAR isoforms, highlights the potential of PPARs as pharmacological targets in MASLD. All three PPAR isoforms may represent a promising approach for addressing the full spectrum of MASLD, from IR to liver fibrosis. This potential has been studied by Francque et al. with the pan-PPAR agonist lanifibranor, which led to improvements in both the metabolic and hepatic health aspects of MASLD patients. Additionally, its role in cardiovascular health amelioration has been demonstrated [107).

Moreover, there are several ongoing clinical trials focusing on novel therapeutics. Iicarin modulation in endoplasmic reticulum stress and the stimulation of NO synthase through the PPARα/Sirt1/AMPKα pathway can significantly improve vascular endothelial function in diabetes, which seems to be a key mechanism of IR [110). On the other hand, daidzein, through its dual agonist activity on PPARα and PPARγ, could address T2DM-related dyslipidemia and vascular inflammation and mitigate glucose-induced damage in endothelial cells. Moreover, using elafibranor for treating MASLD by influencing EMT-related proteins, such as S100a4 and ASB2, could be possible via fibrogenic processes.

6. Conclusions

The presence of ED in MASLD is an underlying pathological consequence that needs to be considered. PPARs are potential regulators of metabolism and inflammation, where the isoform PPARα is indispensable in the regulation of hepatic inflammation and is considered a key molecule for addressing metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease pathogenesis. However, compensatory mechanisms among PPAR isotypes should be considered. PPARs highlight their promise as potential therapeutic targets in the development of pharmacological agents for managing MASLD and associated vascular complications. Future research should continue to explore this potential and the underlying mechanisms to optimize treatment strategies for MASLD and related metabolic disorders.

Author Contributions

APMT: design concept, acquisition of information, and writing of the manuscript; MU: critical revision; VJBB: guidance in the design, critical revision, and correction of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Clyne, A.M. Endothelial response to glucose: dysfunction, metabolism, and transport. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolinsky, H. A proposal linking clearance of circulating lipoproteins to tissue metabolic activity as a basis for understanding atherogenesis. Circ. Res. 1980, 47, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouverneur, M.; Spaan, J.A.E.; Pannekoek, H.; Fontijn, R.D.; Vink, H. Fluid shear stress stimulates incorporation of hyaluronan into endothelial cell glycocalyx. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H458–H452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipowsky, H.H. Microvascular Rheology and Hemodynamics. Microcirculation 2005, 12, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugusman, A.; Kumar, J.; Aminuddin, A. Endothelial function and dysfunction: Impact of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 224, 107832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, S.; Jalkanen, M.; O'Farrell, S.; Bernfield, M. Molecular cloning of syndecan, an integral membrane proteoglycan. J. Cell Biol. 1989, 108, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonova, E.I.; Galzitskaya, O.V. Structure and functions of syndecans in vertebrates. Biochemistry 2013, 78, 1071–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahakis MY, Kosky JR, Dull RO, Tarbell JM. The role of endothelial glycocalyx components in mechanotransduction of fluid shear stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 30 de marzo de 2007;355(1):228-33.

- Rosenberg RD, Shworak NW, Liu J, Schwartz JJ, Zhang L. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans of the cardiovascular system. Specific structures emerge but how is synthesis regulated? J Clin Invest. 1 de mayo de 1997;99(9):2062-70.

- Filmus J, Selleck SB. Glypicans: proteoglycans with a surprise. J Clin Invest. agosto de 2001;108(4):497-501.

- Reitsma, S.; Slaaf, D.W.; Vink, H.; van Zandvoort, M.A.M.J.; Oude Egbrink, M.G. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflug. Arch.-Eur J Physiol. 2007, 454, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.B.S.; Duling, B.R. Permeation of the luminal capillary glycocalyx is determined by hyaluronan. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 1999, 277, H508–H514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudette, S.; Hughes, D.; Boller, M. The endothelial glycocalyx: Structure and function in health and critical illness. J. Veter- Emerg. Crit. Care 2020, 30, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, M.P.; Nelson, R.M.; Mannori, G.; Cecconi, M.O. Endothelial–leukocyte adhesion molecules in human disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 1994, 45, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmeier, W.; Hynes, R.O. Extracellular Matrix Proteins in Hemostasis and Thrombosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 4, a005132–a005132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, W.A. Getting Leukocytes to the Site of Inflammation. Veter- Pathol. 2013, 50, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolaczkowska, E.; Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthel SR, Gavino JD, Descheny L, Dimitroff CJ. Targeting selectins and selectin ligands in inflammation and cancer. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. noviembre de 2007;11(11):1473-91.

- Kayal, S.; Jaïs, J.-P.; Aguini, N.; Chaudière, J.; Labrousse, J. Elevated Circulating E-Selectin, Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1, and von Willebrand Factor in Patients with Severe Infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 157, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomski, M.W.; Palmer, R.M.J.; Moncada, S. Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits human platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium. Lancet 1987, 330, 1057–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.K.; Salerno, J.C. Nitric oxide synthases domain structure and alignment in enzyme function and control. Front. Biosci. 2003, 8, d193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, K.; Zieger, B. Endothelial cells and coagulation. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 387, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badimón L, Martínez-González J. Disfunción endotelial. Revista Española de Cardiología Suplementos. enero de 2006;6(1):21A-30A.

- Lin, P.J.; Chang, C.H. Endothelium dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi 1994, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Widlansky, M.E.; Gokce, N.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Vita, J.A. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.-S.; Ekstedt, M.; Wong, G.L.-H.; Hagström, H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quek, J.; Chan, K.E.; Wong, Z.Y.; Tan, C.; Tan, B.; Lim, W.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Tang, A.S.P.; Tay, P.; Xiao, J.; et al. Global prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in the overweight and obese population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Gastroenterology Hepatology 2022, 8, 20–30. [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, T.H.; Sheron, N.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Carrieri, P.; Dusheiko, G.; Bugianesi, E.; Pryke, R.; Hutchinson, S.J.; Sangro, B.; Martin, N.K.; et al. The EASL–Lancet Liver Commission: protecting the next generation of Europeans against liver disease complications and premature mortality. Lancet 2021, 399, 61–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. NAFLD: A multisystem disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S47–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; Newsome, P.N.; Sarin, S.K.; Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Dufour, J.-F.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. Journal of Hepatology 2020, 73, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tilg, H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut 2024, 73, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado-Rojas, A.d.C.; Zuarth-Vázquez, J.M.; Uribe, M.; Barbero-Becerra, V.J. Insulin resistance and Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Pathways of action of hypoglycemic agents. Ann. Hepatol. 2023, 29, 101182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koek, G.; Liedorp, P.; Bast, A. The role of oxidative stress in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2011, 412, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multi-society Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Rinella, M.; Sanyal, A.J. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 908–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease as a Nexus of Metabolic and Hepatic Diseases. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, M.H.; Zyriax, B.-C.; Jagemann, B.; Roth, E.; Windler, E.; Wiesch, J.S.Z.; Lohse, A.W.; Kluwe, J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with excessive calorie intake rather than a distinctive dietary pattern. Medicine 2016, 95, e3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, M.B.; Lavine, J.E. Dietary fructose in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2525–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, M.A.; Samuel, V.T. The Sweet Path to Metabolic Demise: Fructose and Lipid Synthesis. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2016, 27, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwärzler, J.; Grabherr, F.; Grander, C.; Adolph, T.E.; Tilg, H. The pathophysiology of MASLD: an immunometabolic perspective. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 20, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panciera, T.; Azzolin, L.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. Mechanobiology of YAP and TAZ in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-K.; Peng, Z.-G. Targeting Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells: An Attractive Therapeutic Strategy to Control Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri-Ansari, N.; Androutsakos, T.; Flessa, C.-M.; Kyrou, I.; Siasos, G.; Randeva, H.S.; Kassi, E.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): A Concise Review. Cells 2022, 11, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poisson, J.; Lemoinne, S.; Boulanger, C.; Durand, F.; Moreau, R.; Valla, D.; Rautou, P.-E. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells: Physiology and role in liver diseases. Journal of Hepatology 2016, 66, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, B.-S.; Cao, Z.; Lis, R.; Nolan, D.J.; Guo, P.; Simons, M.; Penfold, M.E.; Shido, K.; Rabbany, S.Y.; Rafii, S. Divergent angiocrine signals from vascular niche balance liver regeneration and fibrosis. Nature 2013, 505, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeve, L.D. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology 2014, 61, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupera, M.; March, S.; Engel, P.; Rodés, J.; Bosch, J.; García-Pagán, J.-C. Sinusoidal endothelial COX-1-derived prostanoids modulate the hepatic vascular tone of cirrhotic rat livers. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2005, 288, G763–G770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Yadav, D.; Gupta, M.; Mishra, H.; Sharma, P. A Study of Carotid Atherosclerosis in Patients with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2012, 28, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber R, Taschler U, Preiss-Landl K, Wongsiriroj N, Zimmermann R, Lass A. Retinyl ester hydrolases and their roles in vitamin A homeostasis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. enero de 2012;1821(1):113-23.

- Tardelli, M.; Claudel, T.; Bruschi, F.V.; Moreno-Viedma, V.; Trauner, M. Adiponectin regulates AQP3 via PPARα in human hepatic stellate cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 490, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Xia, M.; Salas, S.S.; Ospina, J.A.; Buist-Homan, M.; Harmsen, M.C.; Moshage, H. Extracellular vesicles derived from liver sinusoidal endothelial cells inhibit the activation of hepatic stellate cells and Kupffer cells in vitro. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibert-Ramos, A.; Sanfeliu-Redondo, D.; Aristu-Zabalza, P.; Martínez-Alcocer, A.; Gracia-Sancho, J.; Guixé-Muntet, S.; Fernández-Iglesias, A. The Hepatic Sinusoid in Chronic Liver Disease: The Optimal Milieu for Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin YC, Lo HM, Chen JD. Sonographic fatty liver, overweight and ischemic heart disease. World J Gastroenterol. 21 de agosto de 2005;11(31):4838-42.

- Anderson, T.J. Assessment and treatment of endothelial dysfunction in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999, 34, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim J a, Montagnani M, Koh KK, Quon MJ. Reciprocal Relationships Between Insulin Resistance and Endothelial Dysfunction: Molecular and Pathophysiological Mechanisms. Circulation. 18 de abril de 2006;113(15):1888-904.

- Hadi, H.A.R.; Carr, C.S.; Al Suwaidi, J. Endothelial Dysfunction: Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Therapy, and Outcome. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2005, 1, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Lonardo, A.; Zoppini, G.; Barbui, C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hepatology 2016, 65, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa Y, Kwon T, Lennon RJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Prognostic Value of Flow-Mediated Vasodilation in Brachial Artery and Fingertip Artery for Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAHA. 29 de octubre de 2015;4(11):e002270.

- Federico, A.; Dallio, M.; Masarone, M.; Persico, M.; Loguercio, C. The epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its connection with cardiovascular disease: role of endothelial dysfunction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016, 20, 4731–4741. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, F.-Y.; Zhu, Y.Z. Roles of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 192, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear Receptors, RXR, and the Big Bang. Cell. marzo de 2014;157(1):255-66.

- Tontonoz, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Fat and Beyond: The Diverse Biology of PPARγ. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francque, S.; Szabo, G.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Byrne, C.D.; Cusi, K.; Dufour, J.-F.; Roden, M.; Sacks, F.; Tacke, F. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Zheng, Z.; Ren, J.; Qiu, Y. Oleoylethanolamide, an endogenous PPAR-α ligand, attenuates liver fibrosis targeting hepatic stellate cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 42530–42540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Tao Y, Qiu T, Yao X, Jiang L, Wang N, et al. Taurine protected As2O3-induced the activation of hepatic stellate cells through inhibiting PPARα-autophagy pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 25 de febrero de 2019;300:123-30.

- Chakravarthy MV, Lodhi IJ, Yin L, Malapaka RRV, Xu HE, Turk J, et al. Identification of a Physiologically Relevant Endogenous Ligand for PPARα in Liver. Cell. agosto de 2009;138(3):476-88.

- Todisco, S.; Santarsiero, A.; Convertini, P.; De Stefano, G.; Gilio, M.; Iacobazzi, V.; Infantino, V. PPAR Alpha as a Metabolic Modulator of the Liver: Role in the Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Biology 2022, 11, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickam, R.; Duszka, K.; Wahli, W. PPARs and Microbiota in Skeletal Muscle Health and Wasting. IJMS 2020, 21, 8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naruhn, S.; Meissner, W.; Adhikary, T.; Kaddatz, K.; Klein, T.; Watzer, B.; Müller-Brüsselbach, S.; Müller, R. 15-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid Is a Preferential Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor β/δ Agonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 77, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Paglia, L.; Listì, A.; Caruso, S.; Amodeo, V.; Passiglia, F.; Bazan, V.; Fanale, D. Potential Role of ANGPTL4 in the Cross Talk between Metabolism and Cancer through PPAR Signaling Pathway. PPAR Res. 2017, 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone P, Solimando AG, Prete M, Malerba E, Susca N, Derakhshani A, et al. Unraveling the Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor β/Δ (PPAR β/Δ) in Angiogenesis Associated with Multiple Myeloma. Cells. 25 de marzo de 2023;12(7):1011.

- Takada, I.; Makishima, M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists and antagonists: A patent review (2014-present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Leibowitz, M.D.; Doebber, T.W.; Elbrecht, A.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, G.; Biswas, C.; Cullinan, C.A.; Hayes, N.S.; Li, Y.; et al. Novel Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor (PPAR) γ and PPARδ Ligands Produce Distinct Biological Effects. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 6718–6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tan, H.; Wan, J.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Lu, X. PPAR-γ signaling in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 245, 108391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, D.C.; Bargut, T.C.L.; de Carvalho, S.N.; Aguila, M.B.; Mandarim-De-Lacerda, C.A.; Souza-Mello, V. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors-Alpha and Gamma Are Targets to Treat Offspring from Maternal Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e64258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsouris D, Mandard S, Voshol PJ, Escher P, Tan NS, Havekes LM, et al. PPARα governs glycerol metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1 de julio de 2004;114(1):94-103.

- Dreyer, C.; Krey, G.; Keller, H.; Givel, F.; Helftenbein, G.; Wahli, W. Control of the peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway by a novel family of nuclear hormone receptors. Cell 1992, 68, 879–887. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.S.; Tan, W.R.; Low, Z.S.; Marvalim, C.; Lee, J.Y.H.; Tan, N.S. Exploration and Development of PPAR Modulators in Health and Disease: An Update of Clinical Evidence. IJMS 2019, 20, 5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai A, Yang Loureiro Z, DeSouza T, Yang Q, Solivan-Rivera J, Corvera S. PPARγ activation by lipolysis-generated ligands is required for cAMP dependent UCP1 induction in human thermogenic adipocytes. bioRxiv. 11 de agosto de 2024;2024.08.10.607465.

- Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Kwong, J.S.W.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. Efficacy and safety of thiazolidinediones in diabetes patients with renal impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougarne, N.; Weyers, B.; Desmet, S.J.; Deckers, J.; Ray, D.W.; Staels, B.; De Bosscher, K. Molecular actions of PPARα in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 760–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stienstra, R.; Mandard, S.; Tan, N.S.; Wahli, W.; Trautwein, C.; Richardson, T.A.; Lichtenauer-Kaligis, E.; Kersten, S.; Müller, M. The Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist is a direct target gene of PPARα in liver. J. Hepatol. 2006, 46, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.; Baugé, E.; Bourguet, W.; De Bosscher, K.; Lalloyer, F.; Tailleux, A.; Lebherz, C.; Lefebvre, P.; Staels, B. The transrepressive activity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha is necessary and sufficient to prevent liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 2014, 60, 1593–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devchand PR, Keller H, Peters JM, Vazquez M, Gonzalez FJ, Wahli W. The PPARα–leukotriene B4 pathway to inflammation control. Nature. noviembre de 1996;384(6604):39-43.

- Chen, J.; Montagner, A.; Tan, N.S.; Wahli, W. Insights into the Role of PPARβ/δ in NAFLD. IJMS 2018, 19, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Brown, J.D.; Stanya, K.J.; Homan, E.; Leidl, M.; Inouye, K.; Bhargava, P.; Gangl, M.R.; Dai, L.; Hatano, B.; et al. A diurnal serum lipid integrates hepatic lipogenesis and peripheral fatty acid use. Nature 2013, 502, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian B, Wang C, Li X, Ma P, Dong L, Shen B, et al. PPARβ/δ activation protects against hepatic ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Liver Int. diciembre de 2023;43(12):2808-23.

- Morán-Salvador E, López-Parra M, García-Alonso V, Titos E, Martínez-Clemente M, González-Périz A, et al. Role for PPARγ in obesity-induced hepatic steatosis as determined by hepatocyte- and macrophage-specific conditional knockouts. FASEB j. agosto de 2011;25(8):2538-50.

- Ahmadian M, Suh JM, Hah N, Liddle C, Atkins AR, Downes M, et al. PPARγ signaling and metabolism: the good, the bad and the future. Nat Med. mayo de 2013;19(5):557-66.

- Huang S, Jin Y, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Chen N, Wang W. PPAR gamma and PGC-1alpha activators protect against diabetic nephropathy by suppressing the inflammation and NF-kappaB activation. Nephrology (Carlton). 4 de septiembre de 2024.

- Abd-Elhamid TH, Althumairy D, Bani Ismail M, Abu Zahra H, Seleem HS, Hassanein EHM, et al. Neuroprotective effect of diosmin against chlorpyrifos-induced brain intoxication was mediated by regulating PPAR-γ and NF-κB/AP-1 signals. Food Chem Toxicol. 27 de agosto de 2024;193:114967.

- Geng, S.; Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xie, L.; Caldwell, B.A.; Pradhan, K.; Yi, Z.; Hou, J.; Xu, F.; et al. Monocytes Reprogrammed by 4-PBA Potently Contribute to the Resolution of Inflammation and Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 856–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okayasu T, Tomizawa A, Suzuki K, Manaka K ichi, Hattori Y. PPARα activators upregulate eNOS activity and inhibit cytokine-induced NF-κB activation through AMP-activated protein kinase activation. Life Sciences. abril de 2008;82(15-16):884-91.

- Quintela AM, Jiménez R, Piqueras L, Gómez-Guzmán M, Haro J, Zarzuelo MJ, et al. PPAR β activation restores the high glucose-induced impairment of insulin signalling in endothelial cells. British J Pharmacology. junio de 2014;171(12):3089-102.

- Wakino, S.; Hayashi, K.; Kanda, T.; Tatematsu, S.; Homma, K.; Yoshioka, K.; Takamatsu, I.; Saruta, T. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Ligands Inhibit Rho/Rho Kinase Pathway by Inducing Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase SHP-2. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, e45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guixé-Muntet, S.; Biquard, L.; Szabo, G.; Dufour, J.; Tacke, F.; Francque, S.; Rautou, P.; Gracia-Sancho, J. Review article: vascular effects of PPARs in the context of NASH. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 56, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Atkinson, R.D.; Kanel, G.C.; Gaarde, W.A.; DeLeve, L.D. Role of Differentiation of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in Progression and Regression of Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 918–927.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva TM, Li Y, Kinzenbaw DA, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Endothelial PPARγ (Peroxisome Proliferator–Activated Receptor-γ) Is Essential for Preventing Endothelial Dysfunction With Aging. Hypertension. julio de 2018;72(1):227-34.

- Gui, F.; You, Z.; Fu, S.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y. Endothelial Dysfunction in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Verna, L.; Chen, N.-G.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Forman, B.M.; Stemerman, M.B. Constitutive Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor-γ Suppresses Pro-inflammatory Adhesion Molecules in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. 277, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delerive, P.; Martin-Nizard, F.; Chinetti, G.; Trottein, F.; Fruchart, J.-C.; Najib, J.; Duriez, P.; Staels, B. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Activators Inhibit Thrombin-Induced Endothelin-1 Production in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells by Inhibiting the Activator Protein-1 Signaling Pathway. Circ. Res. 1999, 85, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Nizard F, Furman C, Delerive P, Kandoussi A, Fruchart JC, Staels B, et al. Peroxisome Proliferator–activated Receptor Activators Inhibit Oxidized Low-density Lipoprotein–induced Endothelin-1 Secretion in Endothelial Cells: Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. diciembre de 2002;40(6):822-31.

- Berger, J.; Moller, D.E. The Mechanisms of Action of PPARs. Annu. Rev. Med. 2002, 53, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fougerat, A.; Montagner, A.; Loiseau, N.; Guillou, H.; Wahli, W. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors and Their Novel Ligands as Candidates for the Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooreman, M.P.; Vonghia, L.; Francque, S.M. MASLD/MASH and type 2 diabetes: Two sides of the same coin? From single PPAR to pan-PPAR agonists. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2024, 212, 111688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francque, S.M.; Bedossa, P.; Ratziu, V.; Anstee, Q.M.; Bugianesi, E.; Sanyal, A.J.; Loomba, R.; Harrison, S.A.; Balabanska, R.; Mateva, L.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Pan-PPAR Agonist Lanifibranor in NASH. New Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooreman, M.P.; Butler, J.; Giugliano, R.P.; Zannad, F.; Dzen, L.; Huot-Marchand, P.; Baudin, M.; Beard, D.R.; Junien, J.-L.; Broqua, P.; et al. The pan-PPAR agonist lanifibranor improves cardiometabolic health in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao W, Wang K, Wang X, Li X, Dong J, Zhang Y, et al. Icariin ameliorates endothelial dysfunction in type 1 diabetic rats by suppressing ER stress via the PPARα/Sirt1/AMPKα pathway. Journal Cellular Physiology. marzo de 2021;236(3):1889-902.

- Das, D.; Sarkar, S.; Bordoloi, J.; Wann, S.B.; Kalita, J.; Manna, P. Daidzein, its effects on impaired glucose and lipid metabolism and vascular inflammation associated with type 2 diabetes. BioFactors 2018, 44, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, C.; Yao, S.; Qiu, H.; Yang, J.; Wu, K.; Liao, H.; Jiang, Q. Daidzein protects endothelial cells against high glucose-induced injury through the dual-activation of PPARα and PPARγ. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2024, 43, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang M, Barroso E, Ruart M, Peña L, Peyman M, Aguilar-Recarte D, et al. Elafibranor upregulates the EMT-inducer S100A4 via PPARβ/δ. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. noviembre de 2023;167:115623.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).