To predict tool wear accurately, a regression model is essential. For multi-sensor signal data in machine tool processing, the challenge lies in mining temporal data information features and extracting local hidden details. Traditional single deep network models struggle to capture the correlation and important feature information within time-series data, making it difficult to further enhance the prediction effectiveness once a certain accuracy level is achieved.

This chapter introduces a novel deep fusion neural network model, the 1DCNN Informer, designed to predict tool wear by mapping signal features to wear values. Leveraging CNNs’ strong feature extraction capabilities, the model automatically extracts high-level features but faces temporal data processing limitations. Thus, a multi-head probabilistic sparse attention mechanism is employed for deep feature mining, enhancing the model’s global and local feature capture capabilities.

Based on feature extraction, the Informer model is employed to process historical data correlations, enhancing the model’s time-series understanding. This design allows effective feature extraction from sequential data. Data preprocessing includes rigorous cleaning, noise removal, and normalization for accuracy. Processed data is partitioned into training and validation sets, iteratively optimized with training data until preset accuracy is met, then validated on unseen data. Experimental results confirm high accuracy under single operating conditions. Ablation experiments systematically test each neural network module, validating model design. Overall, this chapter’s tool wear prediction technology enhances tool efficiency and provides a foundation for intelligent maintenance in related fields.

3.1. CNN Informer and Encoding Decoding Framework

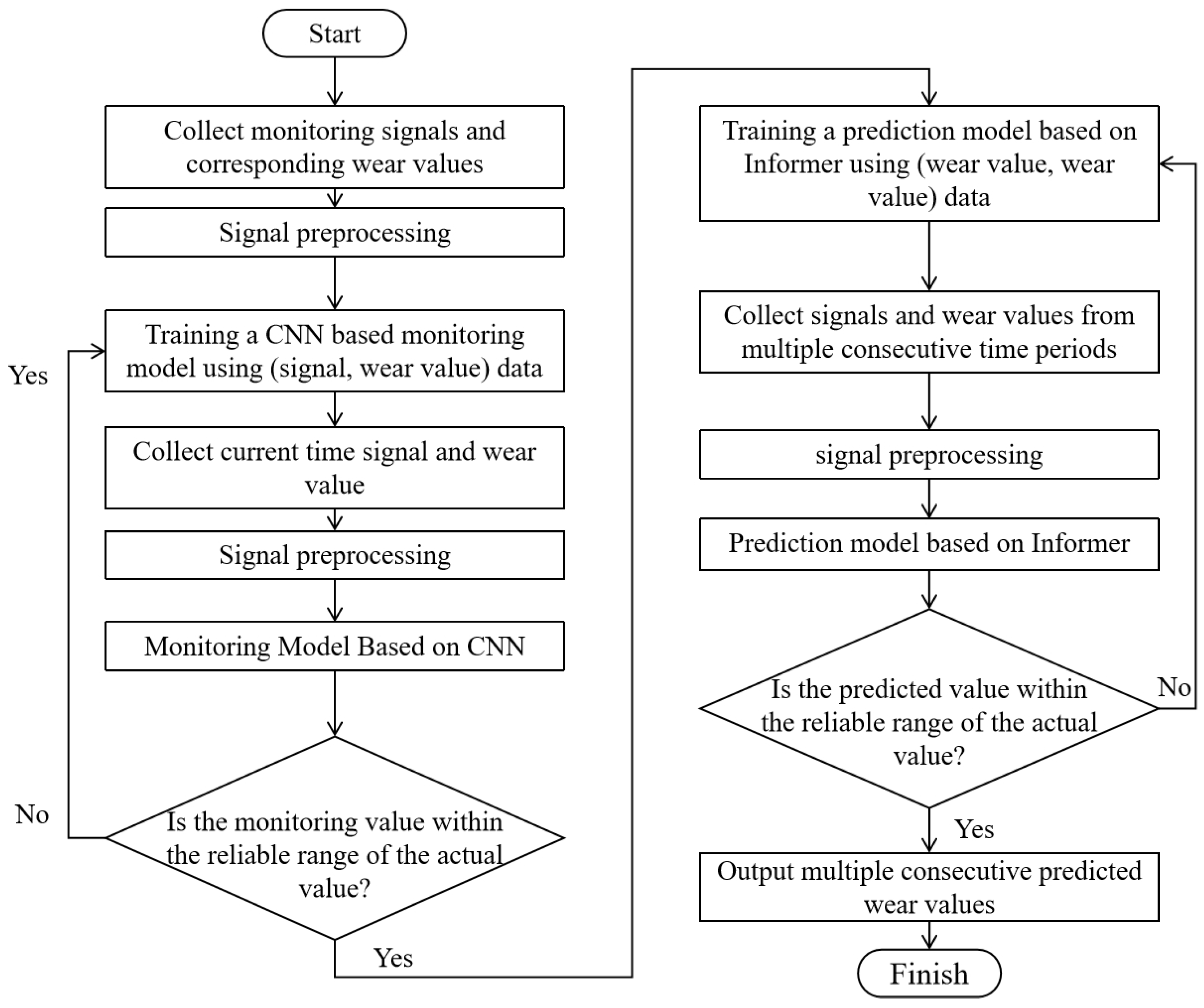

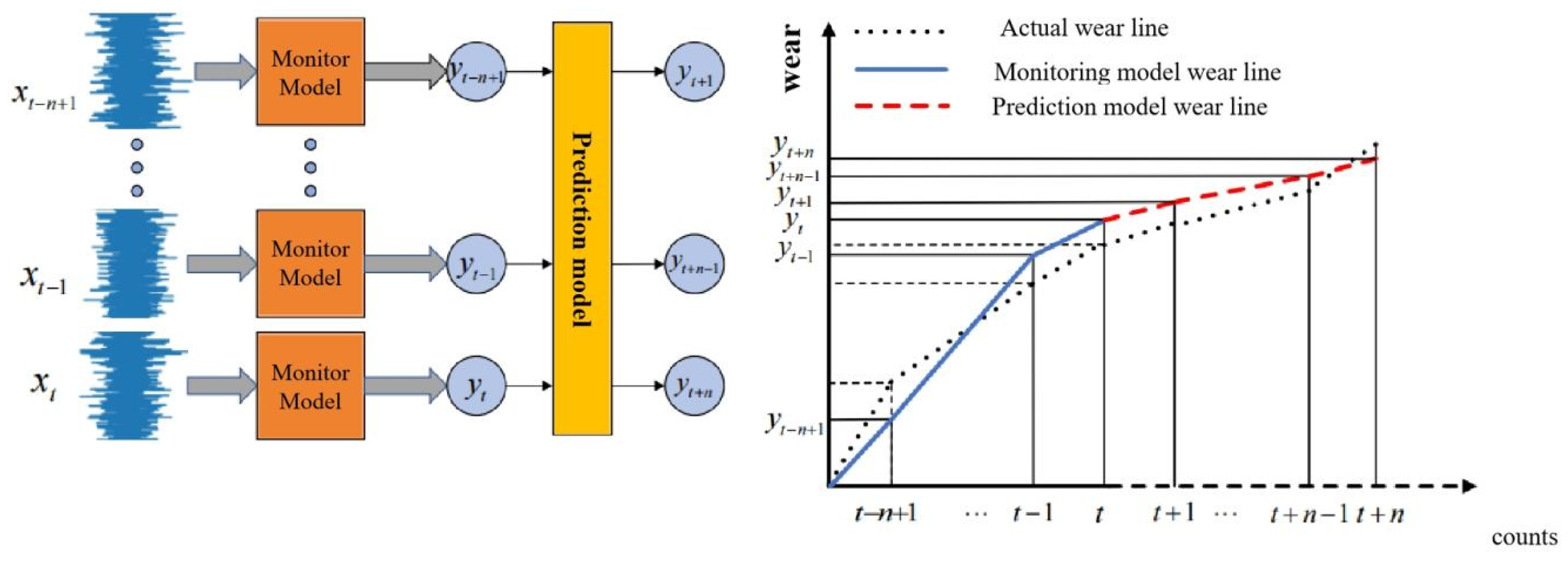

The multi-step prediction process for tool wear based on Informer is shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1.

Flowchart of Multi-step Tool Wear Prediction Based on CNN-Informer.

Figure 3.1.

Flowchart of Multi-step Tool Wear Prediction Based on CNN-Informer.

This chapter mainly designs the Informer structure for wear monitoring, and based on the encoding decoding framework, improves the intermediate layer to achieve wear prediction. The key model structures include Informer and encoding decoding framework, so this section mainly introduces and analyzes them.

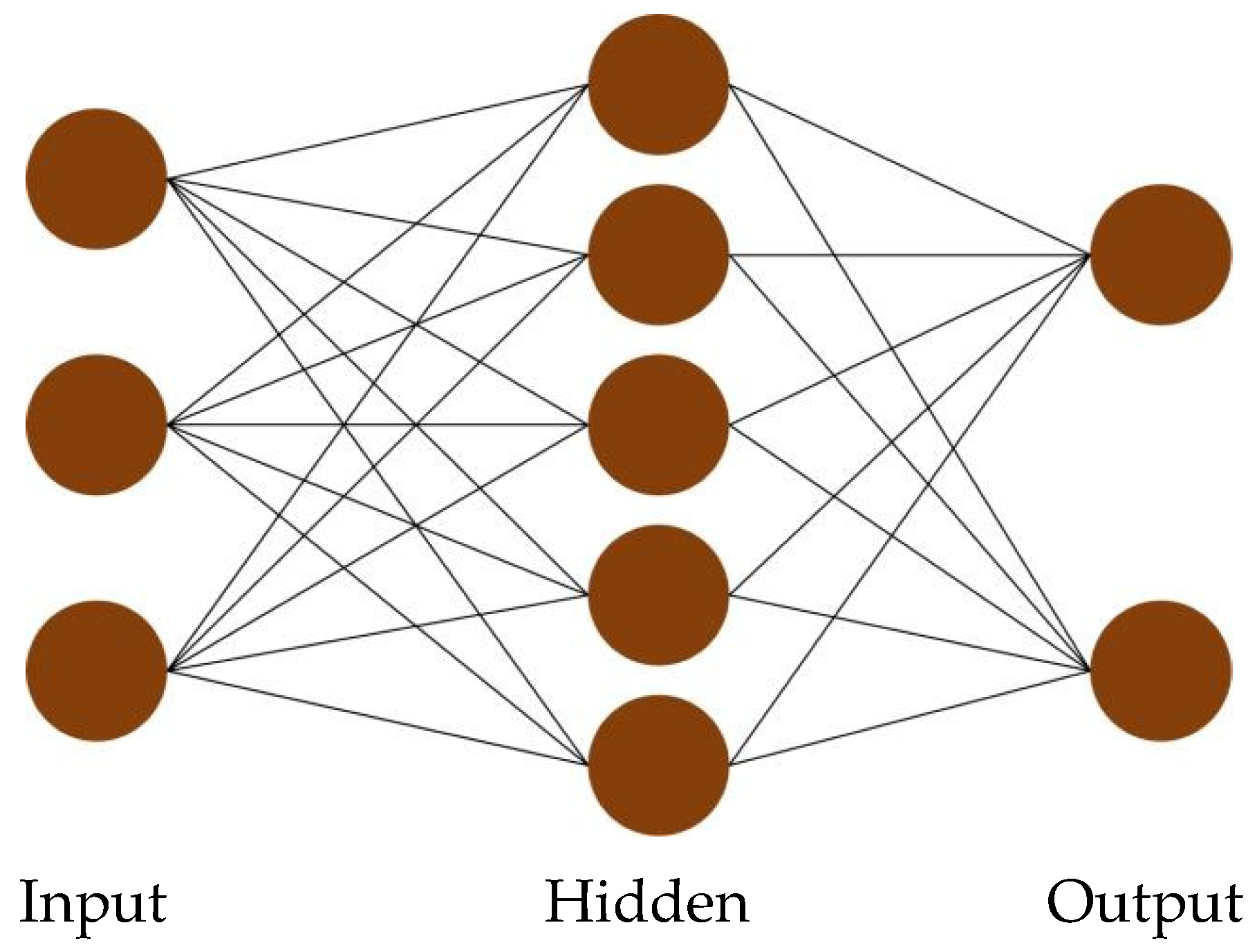

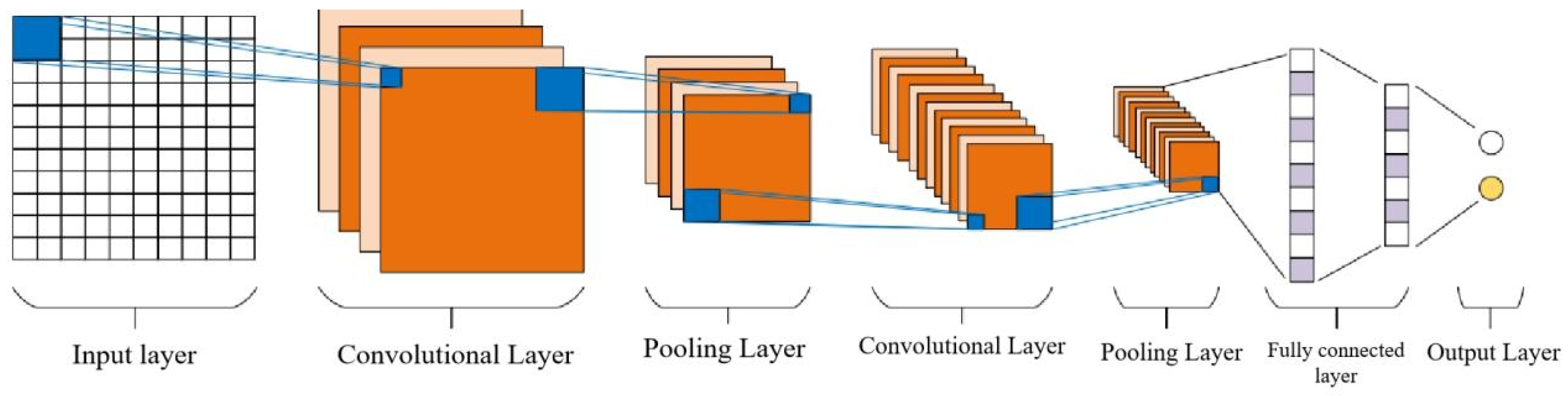

3.1.1. The Principle of Convolutional Neural Network

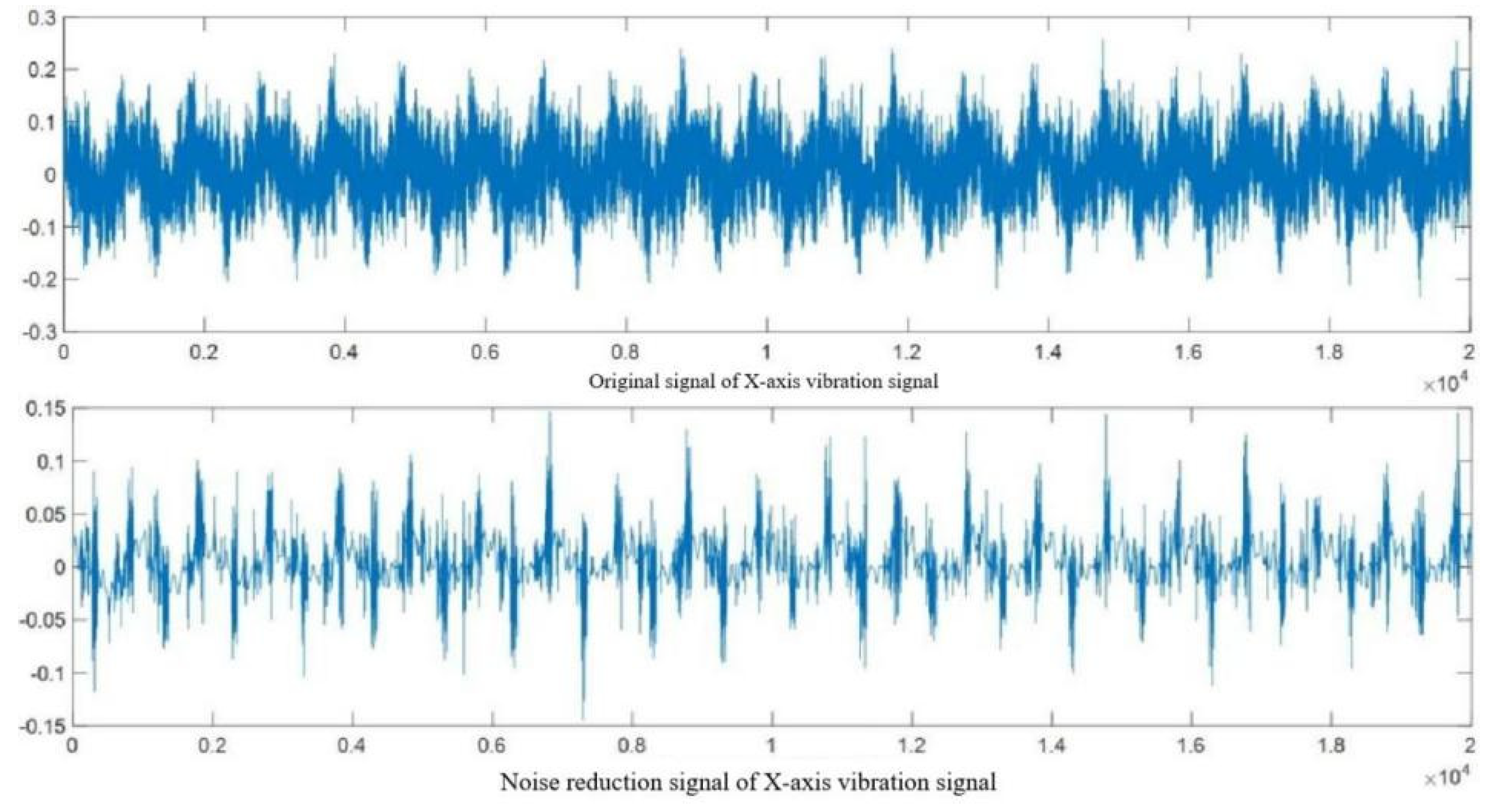

CNN, inspired by biological visual mechanisms, is a widely used deep learning architecture. Through convolution operations, neurons respond within their receptive fields, reducing parameters and complexity, enhancing training efficiency. Design of convolutional kernels allows feature extraction and learning, minimizing manual extraction and enabling deeper feature mining. Pooling layers and nonlinear activation functions further improve generalization and robustness by reducing data dimensions and capturing complex nonlinear relationships. CNN showcases strong potential in image recognition, video analysis, and NLP, automating pattern discovery and significantly enhancing performance in complex tasks. It has achieved notable results in image classification, object detection, video understanding, and biomedical imaging [59].

The typical structure of a convolutional neural network is shown in Figure 3.2, which mainly includes the following structures:

(1) Convolutional Layer

As the core of convolutional neural networks, convolutional layers are generally composed of multiple convolutional kernels. Convolutional kernels extract features from input data through convolution operations, and as the number of convolution layers gradually increases, the extracted features become increasingly abstract. The expression for convolution operation is shown in equation (3.2):

Figure 3.2.

Typical Convolutional Neural Network Structure.

Figure 3.2.

Typical Convolutional Neural Network Structure.

Among them,

represents the jth feature image of the l-th layer,

represents the weight between the j-th feature image in the l-th layer and the i-th feature image in the l-1 layer,

represents its corresponding bias, and f represents the activation function, * represents convolution operation,

represents the set of input graphs.From the above equation, it can be seen that convolution operations are mainly composed of linear operations and nonlinear operations. Among them, linear operations are mainly affected by feature weights and biases, and weight and sum some features of the feature image. Nonlinear operations are based on activation functions to apply influence, so activation functions usually have a significant impact on the performance of convolutional layers. Common activation functions include sigmoid (equation 3.2), tanh (equation 3.3), and relu (equation 3.4). Due to their inherent characteristics, sigmoid and tanh may exhibit overly flat output performance when the input data is very large or very small, which can easily cause gradient vanishing during the training process and ultimately lead to convergence difficulties for deep learning. Therefore, the convolutional layers of convolutional neural networks generally consider using ReLU as their activation function.

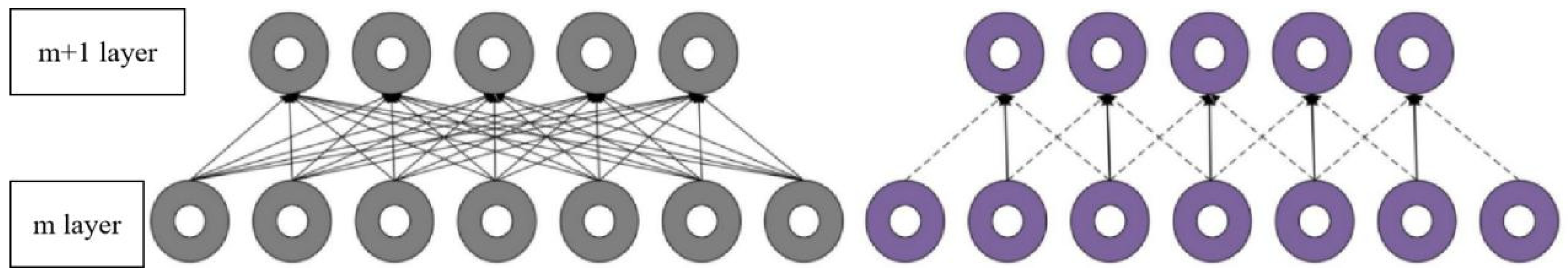

Convolutional layer neurons are sparsely connected, facilitating weight sharing and sparse connections, as depicted in Figure 3.3. Sparse connections limit neuron receptive fields but, in deep networks, deeper neurons still interact with input data. This maintains robustness while reducing model complexity. Weight sharing reduces parameter learning and storage, enhancing computational efficiency by calculating weights on fixed-size kernels.

Figure 3.3.

The Difference Between Full-Connected and Non-Fully Connected.

Figure 3.3.

The Difference Between Full-Connected and Non-Fully Connected.

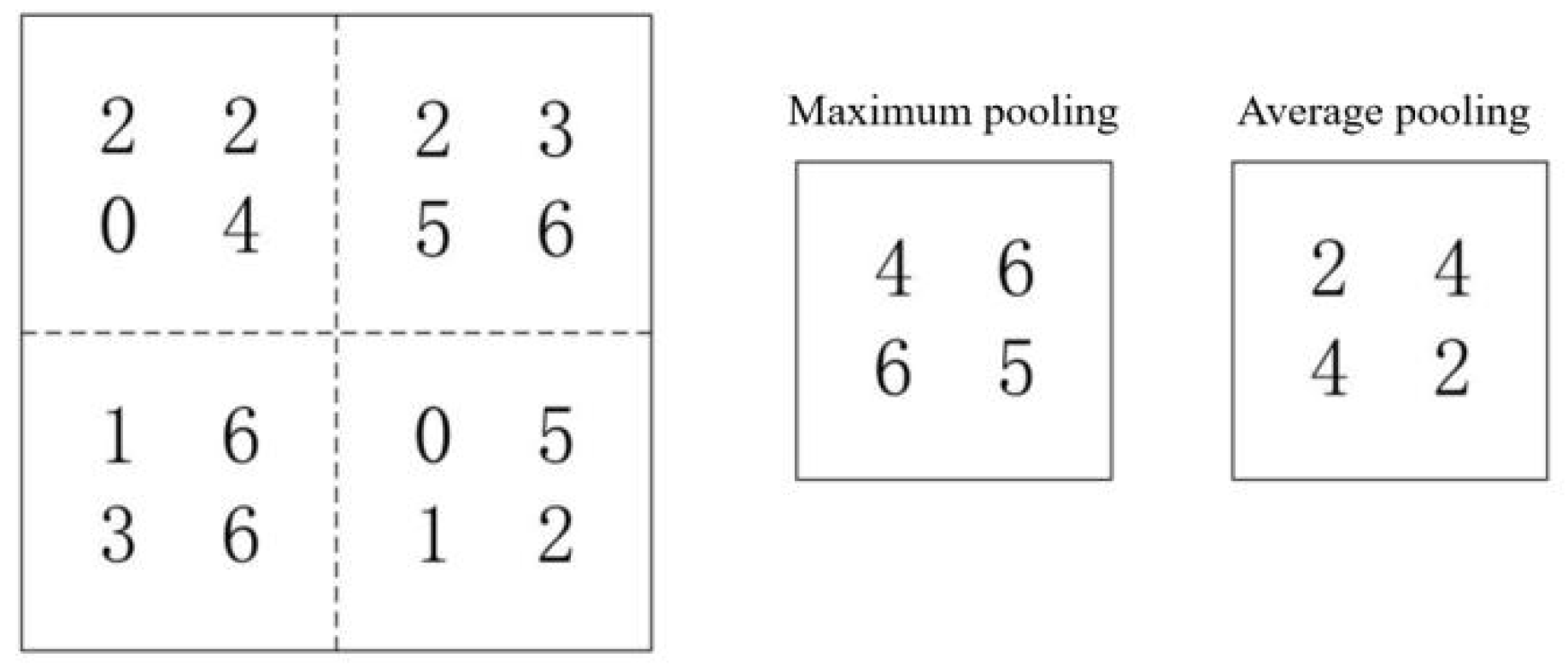

(2) Pooling layer

The pooling layer usually follows the convolutional layer and aggregates the features of adjacent regions in the feature map based on convolution operations, achieving downsampling of the original features. The pooling layer can reduce the size of feature maps while ensuring feature validity, thereby accelerating the training rate of the model. The pooling calculation is shown in equation (3.5):

Among them, down (.) is a pooling function, and each feature map has its own multiplier bias β and additional bias b. The pooling layer mainly includes three pooling methods: max pooling, average pooling, and random pooling. Maximum pooling eliminates some minor features by retaining the maximum value of features within the pooling area, but this may amplify the noise in the features and reduce the generalization ability of the model. Average pooling achieves comprehensive consideration of all features in the pooled area by arithmetic averaging and recording the mean, but it also reduces the strength of typical features in the area. Random pooling uses a random selection method to preserve a feature within the pooling area, and it is precisely the randomness introduced by this method that improves the robustness of the model. As shown in Figure 3.4, the effects of max pooling and average pooling on feature maps are demonstrated.

Figure 3.4.

Max Pooling and Average Pooling.

Figure 3.4.

Max Pooling and Average Pooling.

(3) Fully connected layer

The combination of convolutional layers and pooling layers forms the low hidden layer of a convolutional neural network. The network completes the extraction of local features in the low hidden layer, and then needs to integrate them into global features to achieve comprehensive analysis of global features. The fully connected layer is usually set at the end of the convolutional neural network to summarize and synthesize the previously extracted local features. All neurons in the fully connected layer will be connected to all neurons in the previous layer, including both linear and nonlinear operations. The calculation formula is shown in equation (3.6):

Among them, is the output feature map of layer l-1, is the l-layer feature map connect to the weight, A is the bias coefficient of layer l.

(4) Output layer

The output layer essentially belongs to the fully connected layer, which serves as the end of the entire network to calculate the final output result. The activation functions of the output layer are classified into multiple categories based on their different purposes. For regression problems, the results can be directly calculated and output; For classification problems, softmax is generally used as the activation function (Equation 3.7), and then the classification results are calculated.

Among them, is the output of the previous unit received by the classifier, i represents the category index of the classifier, and C is the number of all categories. represents the ratio of the index of the current element to the sum of the indices of all elements in the classifier.The softmax function can be used to convert the numerical values output by a multi class model into the relative probabilities of each class.

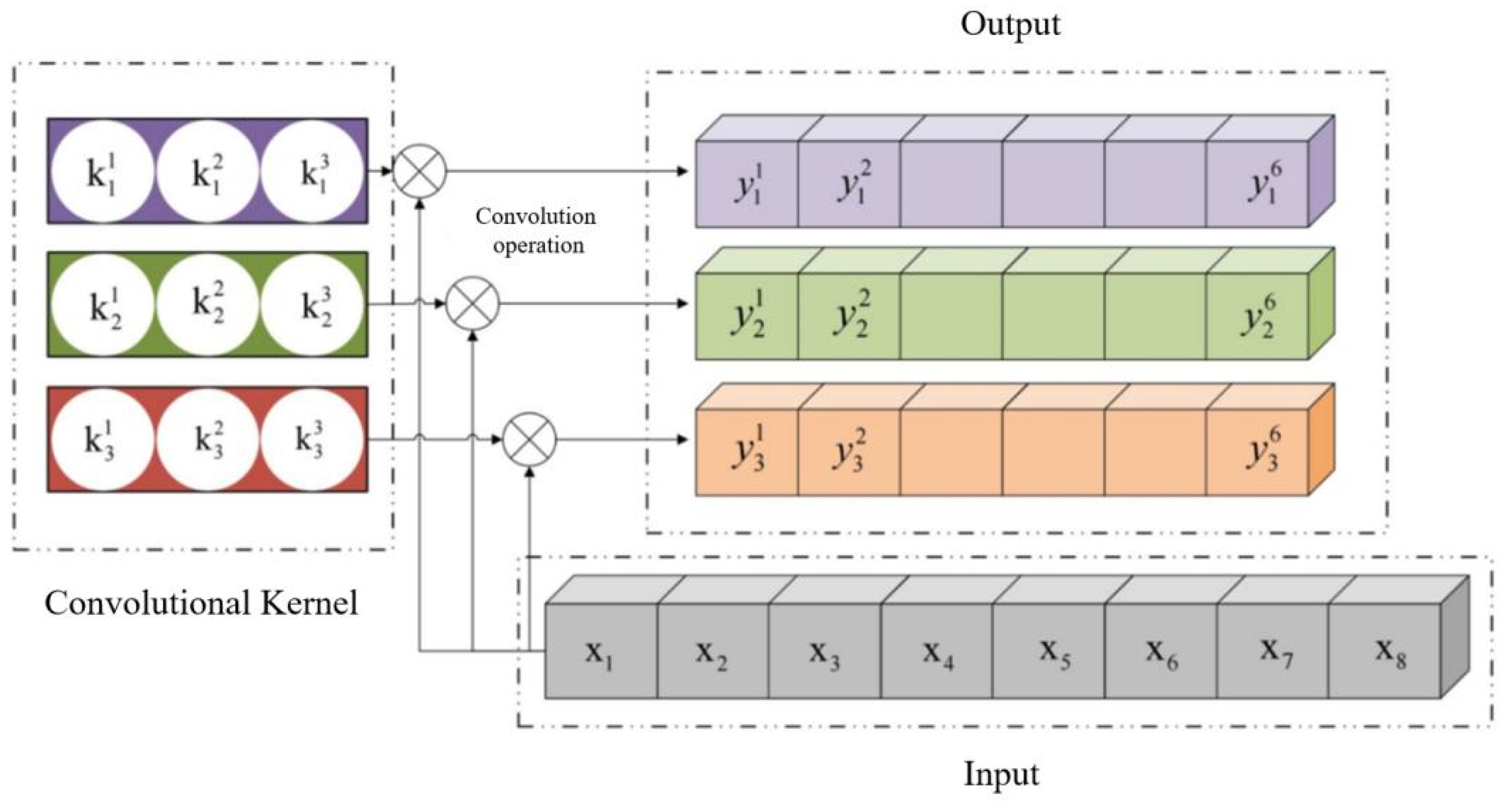

3.1.2. Feature Extraction Based on One-Dimensional Convolution Kernel

In recent years, deep convolutional networks have achieved remarkable success in image processing, sparking interest in applying Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to sensor signal processing. Sensor signals, typically one-dimensional (1D) data like time series, differ from traditional 2D image data. Standard CNNs with 2D convolution kernels aren’t suitable, necessitating the introduction of 1D CNNs. These networks efficiently process time series signals using 1D convolution kernels for feature extraction. With a simpler structure than 2D CNNs, 1D CNNs directly accommodate 1D data characteristics, reducing complexity. Studies show that 1D CNNs excel in temporal signal analysis, automatically extracting features and eliminating the need for manual feature engineering. They also extract higher-level abstract features through layered convolution, often elusive to traditional methods. By stacking multiple convolution layers, 1D CNNs capture temporal dependencies and local signal features, crucial for tasks like signal classification, regression, or anomaly detection. This approach not only simplifies multi-source information fusion but also extracts abstract features beyond traditional methods’ reach. Furthermore, 1D CNNs integrate easily with other modules like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), bolstering their complex temporal data processing capabilities.

The schematic diagram of one-dimensional convolution operation is shown in Figure 3.5. This convolutional layer contains three convolutional kernels, with a kernel size of 3. Each kernel will traverse the input signal once and perform a convolution operation to obtain the feature output after the convolution operation. Taking the first convolution kernel in Figure 3.5 as an example, it has three weights , When using convolution kernels for convolution operations, each weight in the kernel is sequentially multiplied and summed with the corresponding neuron in the convolved region, and the corresponding activation function is applied to the summed value to obtain the output value . Subsequently, the convolution kernel slides through the entire input signal with a step size of 1 and repeats the previous convolution operation until the kernel traverses the entire input signal. At this point, the complete output of the first convolution kernel, , can be obtained.

Figure 3.5.

The Convolution Calculation Process of One-Dimensional Convolution Kernel.

Figure 3.5.

The Convolution Calculation Process of One-Dimensional Convolution Kernel.

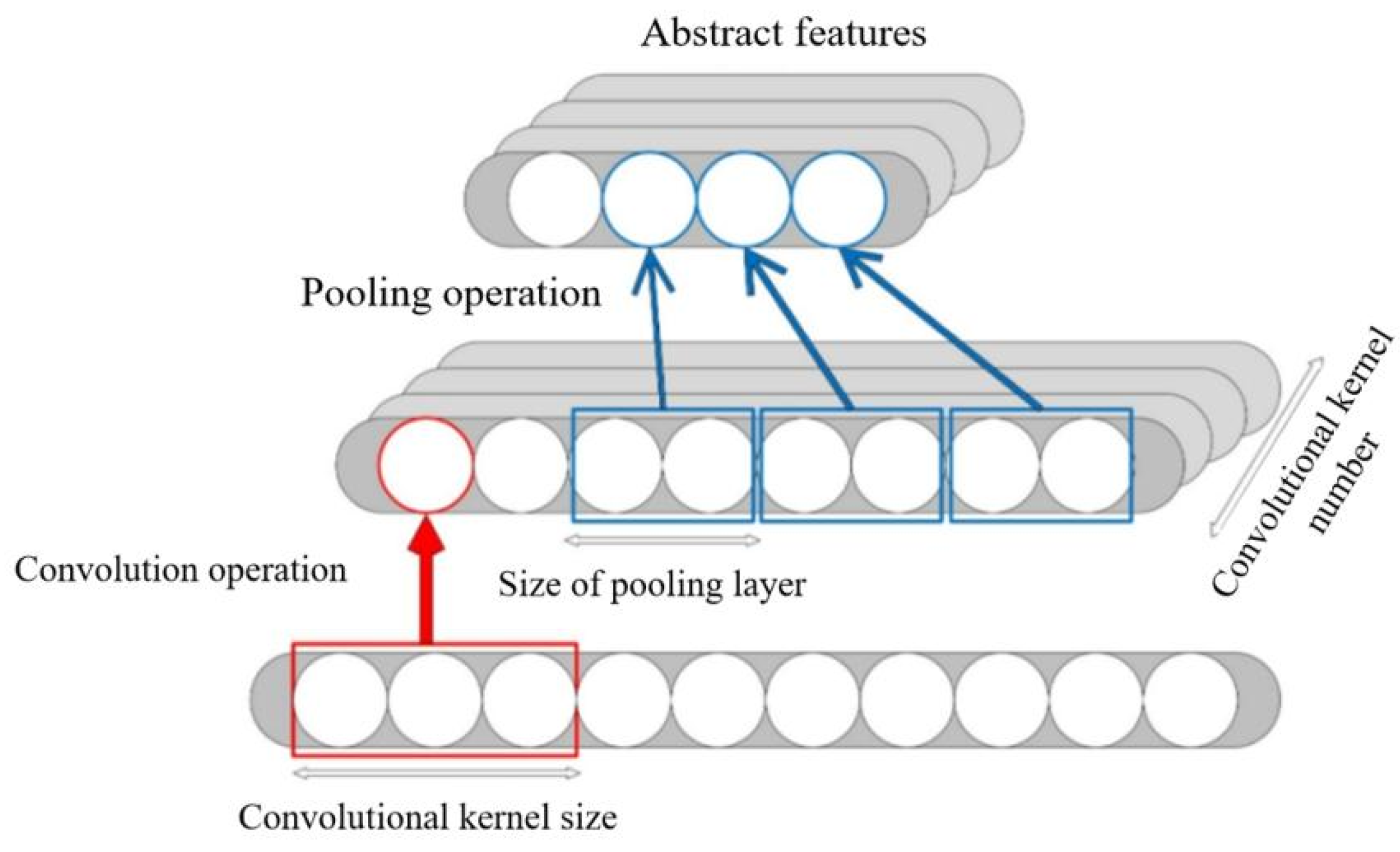

After convolution, a pooling operation is typically performed, as shown in Figure 3.6. Multiple 1D convolution kernels extract multi-dimensional features from the input, while pooling reduces feature map size and accelerates subsequent feature extraction. Through the stacking of multiple convolutional and pooling layers, feature maps derived from the original signal are abstracted from shallow to deep, ultimately yielding abstract features representing the input vector.

Figure 3.6.

Combination of Convolution and Pooling Operations.

Figure 3.6.

Combination of Convolution and Pooling Operations.

3.1.3. The Principle of Informer Model

Before introducing the Informer model, let’s briefly talk about the shortcomings of its predecessor, the Transformer model.The Transformer mechanism was proposed by Vaswani et al [61]. in 2017, and is a neural network model based on attention mechanism proposed by the research team for machine translation tasks, namely the Transformer model.The Transformer model introduces a mechanism called “self attention mechanism” to weight and combine information from different positions when processing input sequences, thereby achieving parallel processing and long-range dependency modeling, greatly improving the efficiency and performance of sequence data processing. However, Transformer has several serious issues, such as not being directly applicable to long-term time series prediction problems, such as quadratic time complexity, high memory usage, and inherent limitations of encoder decoder architecture, with certain restrictions on sequence length, and so on [62].

Position encoding is an important part of Transformer, which is divided into absolute position encoding and relative position encoding. Currently, relative position encoding operates on the attention matrix before softmax, which theoretically has a drawback. The attention matrix with relative positional information is a probability matrix, where the sum of each row is equal to 1. For Transformers, self attention enables interaction between tokens, where the same input indicates that each is the same.That is to say, the difference between the collected data is very small in a short period of time, and due to accuracy issues, the output results of each position of the model are always the same or extremely similar data. Transformers also have the drawbacks of high computational complexity and long training time. Compared with CNN and RNN, Transformer has weaker ability to obtain local information [63].

The Informer mechanism is an innovative approach for time series prediction, emerging around 2017 [64]. Researchers began experimenting with self-attention mechanisms for time series data processing, recognizing the Transformer’s limitations with fixed-size memory, which hinders long sequence handling and remote feature capturing. To address this, Zhou [65] proposed Informer, an efficient model that splits sequences into varying-length subsequences via a hierarchical mechanism, dynamically adjusting processing based on contextual sequence length to better manage long sequences. Compared to Transformers, Informer excels in sequence modeling tasks, especially in predicting future time steps, by better processing temporal information, capturing long-term dependencies, and forecasting future trends [66].

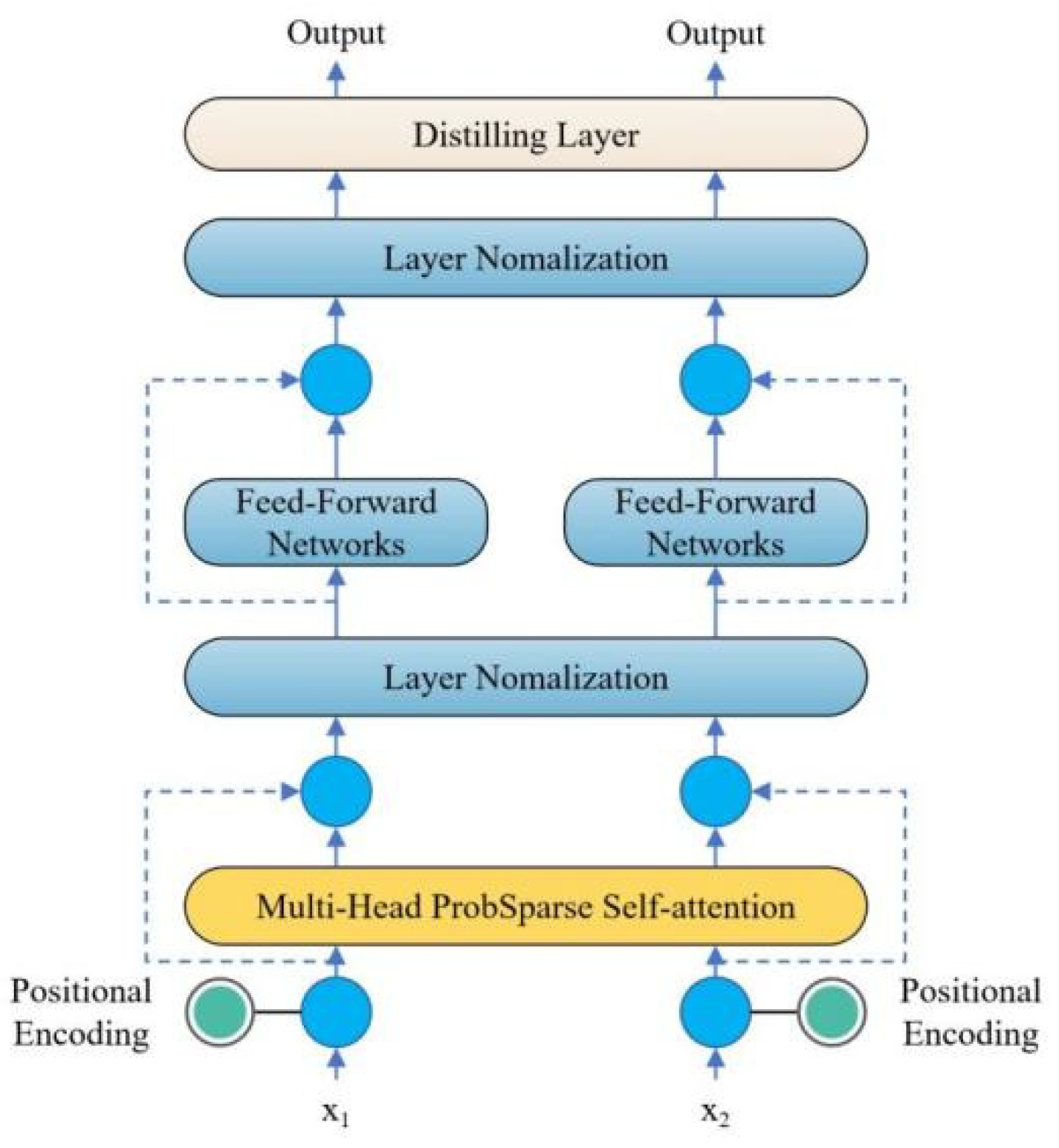

The Informer model based on Transformer design has the following significant features:

(1) A sparse self attention mechanism that can achieve zero time and space complexity (LlogL), with lower complexity than traditional self attention mechanisms.

(2) The optimized multi head attention mechanism highlights dominant attention by halving the input of cascaded layers and effectively handles excessively long input sequences, improving the model’s ability to focus on various regions.

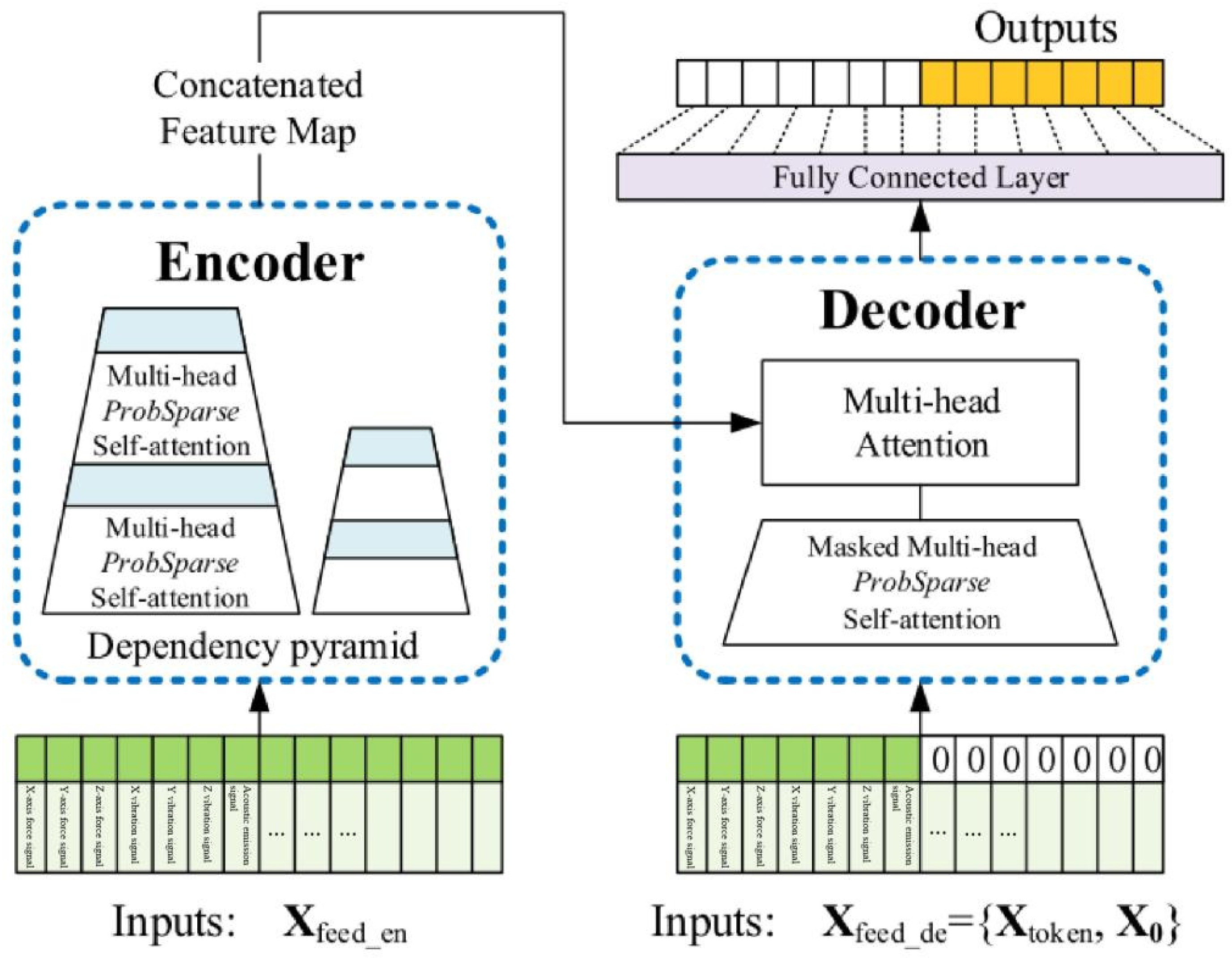

(3) A Transformer based generative decoder performs a forward operation on long time series instead of a step-by-step approach for prediction, greatly improving the inference speed of long sequence prediction. The other features are basically similar to Transformer and will not be further elaborated. The main structure of the Informer mechanism has been redrawn here, as shown in Figure 3.7.

Figure 3.7.

Schematic Diagram of Informer Model Mechanism.

Figure 3.7.

Schematic Diagram of Informer Model Mechanism.

The Informer network consists of two main parts: an encoder and a decoder. In Figure 3.7, the encoder extracts a large number of long sequences (green series) from the input, and the self attention blocks are ProbSparses, which extract dominant attention and reduce network size.The decoder receives a long sequence input (Green part before element 0),The filling element for 0 is ;The connected feature maps and attention combinations are fused to immediately predict long sequence outputs (yellow series). In the prediction of milling cutter wear, Informer adds position encoding to the data input to ensure that the model can capture the correct order of the input sequence.Location encoding is divided into Local Time Stamp and Global Time Stamp. time series ,Using sensor signal data features as inputs to the Informer network, the temporal correlation of the time series by using positional encoding, namely local timestamps and global timestamps, the local and global backward and forward temporal positional relationships of time series can be fully utilized [67].

By utilizing Informer’s multi head attention mechanism, attention is focused on prominent data features to obtain long-term dependencies of evaluation indicators in time series. The decoder input consists of two parts, one is the implicit intermediate feature data about sensor signal risk assessment indicators output by the encoder, and the other part requires the placement of evaluation indicators for predicting milling cutter wear, in order to use predicted 0 occupancy at the input and add masking mechanisms. The data is connected to the multi head attention mechanism, and then connected to the fully connected layer output to achieve the prediction of tool wear. After the encoding step, the input data entering the encoder layer can be obtained, as shown in formula 3.8.

Informer introduced ProbSparse, which first calculates the KL divergence between the i-th query and the uniformly distributed query to obtain the difference, and then calculates the sparsity score. The calculation formula for KL divergence is shown in 3.9.

Among them, P (x) represents the probability distribution of the i-th query, and Q (x) represents the probability distribution of uniformly distributed queries. KL divergence measures the difference between two probability distributions, with larger values indicating that the two distributions are less similar.

Based on the above, the sparse attention mechanism ProbSparse is introduced, and the formula is shown in 3.10.

The Informer encoder is an important component of this model, designed to analyze the input sensor signal data in depth and extract the time series dependence of milling cutter wear through two intricately designed identical operation stacks. Each stack integrates a multi head self attention mechanism, which can process multiple attention heads in parallel, allowing the model to capture multi-level and complex temporal dependencies in the data. In addition, in order to preserve the position information of the time series, the encoder introduces position encoding to ensure that the precise position of each data point on the time axis can be considered when analyzing sensor signals.

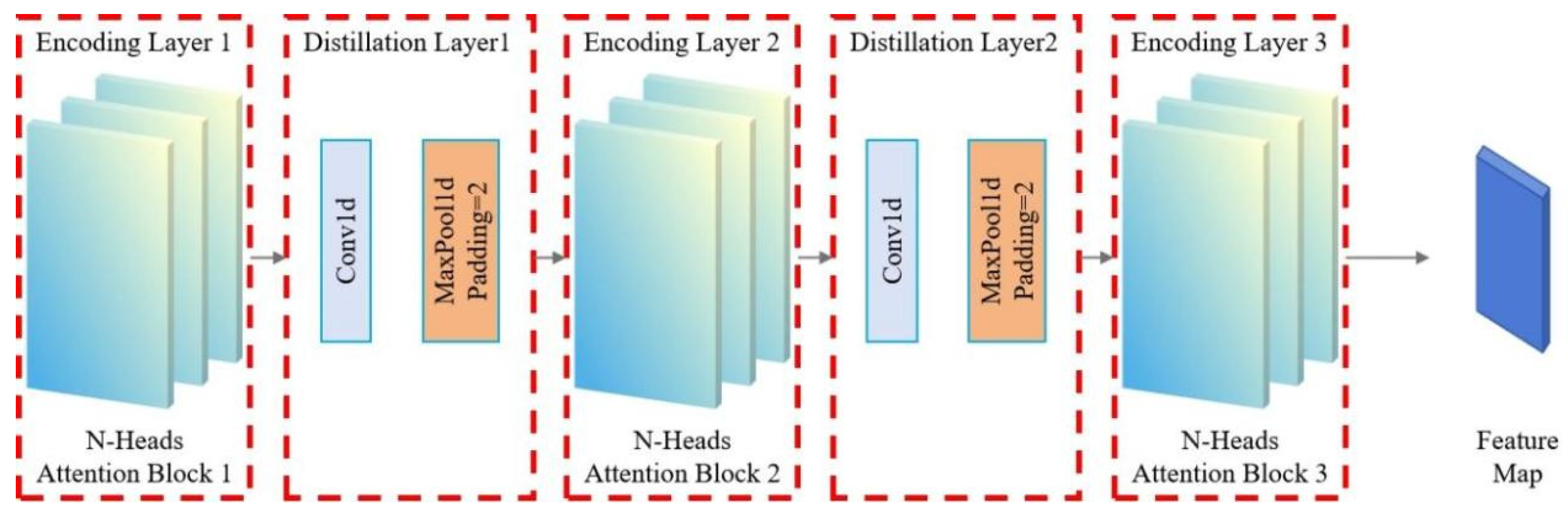

After the self-attention mechanism, the encoder employs a feedforward neural network (FFN) to extract complex patterns through nonlinear transformations on intermediate features. Residual connections and layer normalization enhance training stability and mitigate gradient issues. These technologies enable efficient long time series processing, mapping milling cutter wear information to sensor-reflecting intermediate features. These features underpin the decoder, enhancing milling cutter wear prediction accuracy, vital for industrial predictive maintenance and fault diagnosis, boosting production efficiency and equipment reliability. Informer excels in complex time series handling, shown in Figure 3.8. Stack 1 processes the full input sequence, while Stack 2 handles half, each comprising an encoding layer, distillation layer (including a multi-head probabilistic sparse self-attention layer, FFN, residual connections, and regularization), as detailed in formula 3.11.

The Distillation layer improves the robustness of the network and reduces the memory used by the network. The outputs of all stacks are concatenated to obtain the final hidden representation of the encoder, as shown in Figure 3.7. Among them, Sublayer is a multi head sparse self attention mechanism and forward neural network processing function, while LayerNorm is a regularization function.

Figure 3.8.

Informer Encoder Stack Structure.

Figure 3.8.

Informer Encoder Stack Structure.

3.1.4. Typical Self Attention Mechanism and Improved ProbSparse Self Attention Mechanism

(1) Typical self attention mechanism

A typical attention mechanism is a commonly used mechanism in deep learning to selectively focus on certain positions in an input sequence, thereby achieving weighted processing of different positions. The calculation formula is shown in 3.12.

Calculating weights based on the relationships within the input sequence. In the self attention mechanism, the model calculates the dot product between the query vector (Q) and the key vector (K), and divides it by a scaling factor (usually the square root of the vector dimension) to obtain the weights. Then, by normalizing the weights through a softmax function, the weight distribution is obtained. Finally, multiply the weight distribution with the value vector (V) to obtain the weighted value vector as the final self attention representation. The self attention mechanism can automatically learn the weight distribution based on the dependency relationship between different positions, thus paying more attention to important position information in the encoding process.

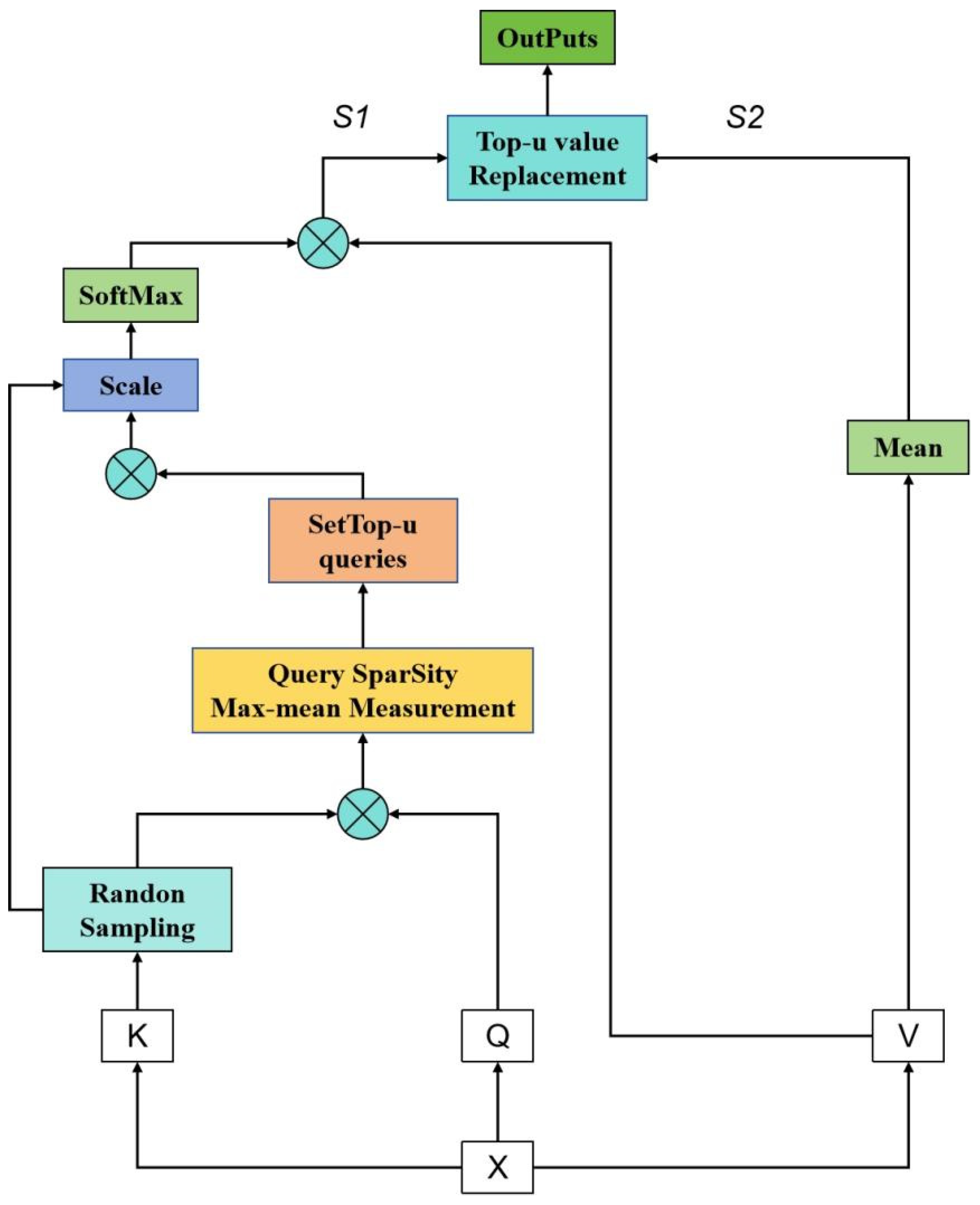

(2) Improving the Prob Sparse self attention mechanism

In order to address the issues of self attention, Zhou et al. proposed an improved Probe Sparse self attention mechanism, whose structure is shown in Figure 3.9 [68].

Prob Sparse Self Attention is a variant of the attention mechanism in deep learning, introducing probabilistic sparsity to limit the attention weight matrix’s sparsity, reducing computational complexity and model parameters. It calculates the dot product between query (Q) and key (K) vectors, applies a softmax function to obtain the initial attention weights, then computes the KL divergence between Q and a uniform distribution to measure dispersion. This divergence penalizes overly concentrated attention weights. By calculating a sparsity score, the difference is scaled to obtain a corrected attention weight matrix. Finally, this matrix is multiplied with the value (V) vector to produce the weighted representation, serving as the final Prob Sparse Self Attention output.

Prob Sparse Self Attention reduces the density of the generated attention weight matrix by introducing probability sparsity, thereby reducing computational complexity and model parameters. This attention mechanism is particularly useful when dealing with long sequence data, as it can improve the computational efficiency and performance of the model. Meanwhile, Probe Sparse Self Attention can also flexibly control the sparsity of attention weights by adjusting the weights of sparsity scores, thus adapting to the needs of different tasks and model structures.

Figure 3.9.

Prob-Sparse Self-attentive structure.

Figure 3.9.

Prob-Sparse Self-attentive structure.

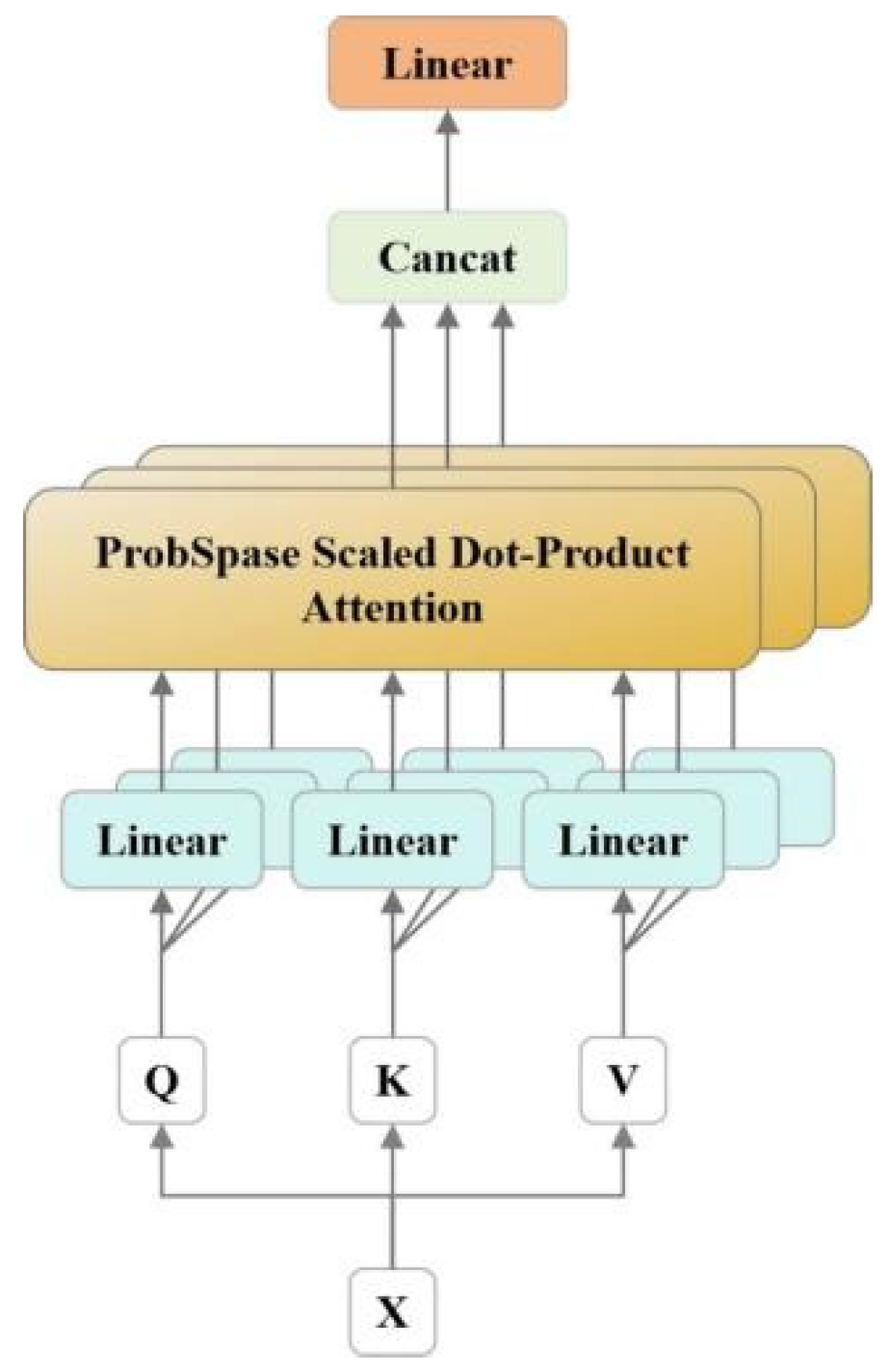

3.1.5. Optimization of Multi Head Attention Mechanism

The optimized multi-head attention enhances the attention layer’s performance by expanding focus areas and providing multiple ‘representation subspaces’. This allows learning from diverse subspaces. Figure 3.10 depicts the structure of the optimized multi-head self-attention module.

Figure 3.10.

Multi-headed attention mechanism structure.

Figure 3.10.

Multi-headed attention mechanism structure.

The Q, K, and V in the linear layer of the figure were initially applied to linear transformations. Then feed back the results of the linear transformation to the self attention layer. The output values are concatenated and then a linear transformation is applied to determine the final result. By using formulas 3.13 and 3.14, the following results can be obtained:

The calculation formula for a single head is as follows:

3.1.6. Encoder and Decoder

(1) The encoder extracts robust long-term dependencies from long sequence inputs, which are shaped into a matrix. Figure 3.11 shows a schematic diagram of the encoder, and the decoder is similar to the encoder diagram and will not be repeated here.

The encoder is responsible for transforming the input sequence into an abstract representation that contains the semantic information of the input sequence. Encoders are typically composed of multiple layers, each containing multiple sub layers such as Self Attention mechanism, Feed Forward Neural Network, and multi head attention module.

Figure 3.11.

Encoder and Decoder structure diagram.

Figure 3.11.

Encoder and Decoder structure diagram.

(2) The decoder is responsible for converting the abstract representation output by the encoder into the target sequence. Its working process is similar to that of the encoder, but it usually includes additional attention mechanisms to handle the relationship between the encoder output and the target sequence [69].The working process of encoders and decoders is usually achieved through the combination of multiple layers and sub layers. Each layer can use different attention mechanisms, feedforward neural networks, etc. for information processing, gradually extracting semantic information from the input sequence and generating the output of the target sequence. The working process is shown in Figure 3.11. This encoder decoder structure has achieved significant performance improvements in many sequence data processing tasks.

3.1.7. Feedforward Network

A Feed Forward Network (FFN) is a fully connected feedforward neural network that is often used as part of attention mechanisms, such as in encoders and decoders. FFN typically consists of two fully connected layers, which introduce nonlinear transformations into the attention mechanism to increase the expressive power of the model. Specifically, FFN takes the output of the attention mechanism as input, processes it through two fully connected layers, and finally generates the output of the encoder or decoder. The calculation formula is shown in 3.15.

In summary, X is the input vector, W1/W2 and b1/b2 are weight matrices and bias vectors of two fully connected layers, and Max(0, x) denotes the ReLU activation function. FFN introduces nonlinearity into the attention mechanism, enhancing model expressiveness. In encoders and decoders, FFN follows attention layers to process outputs, increasing model complexity and performance in sequence data tasks.

3.1.8. Residual Connection and Layer Normalization

In the INFORMER encoder, each sub layer of each encoder - namely the self attention layer and FFN layer - has a residual connection, followed by layer normalization operation, as shown in Figure 3.12.

Figure 3.12.

Residual connectivity and layer normalization.

Figure 3.12.

Residual connectivity and layer normalization.

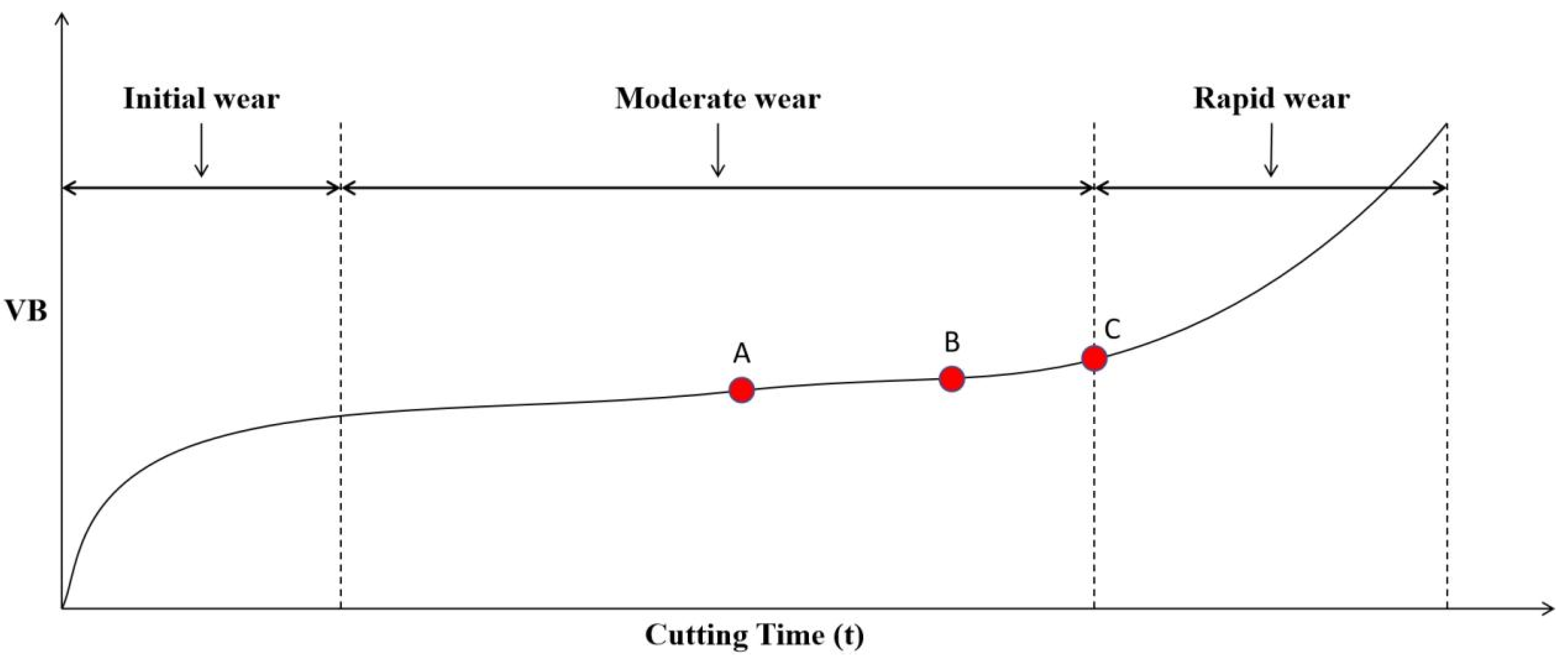

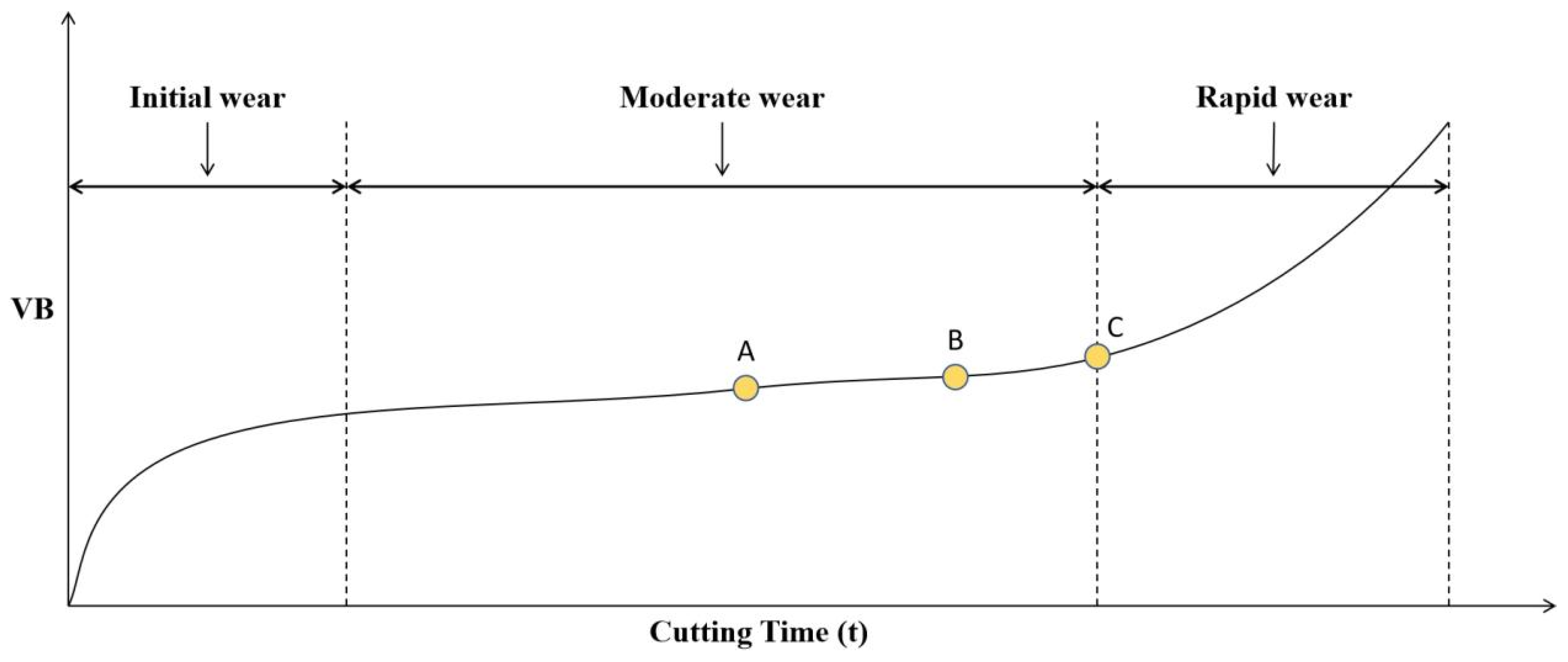

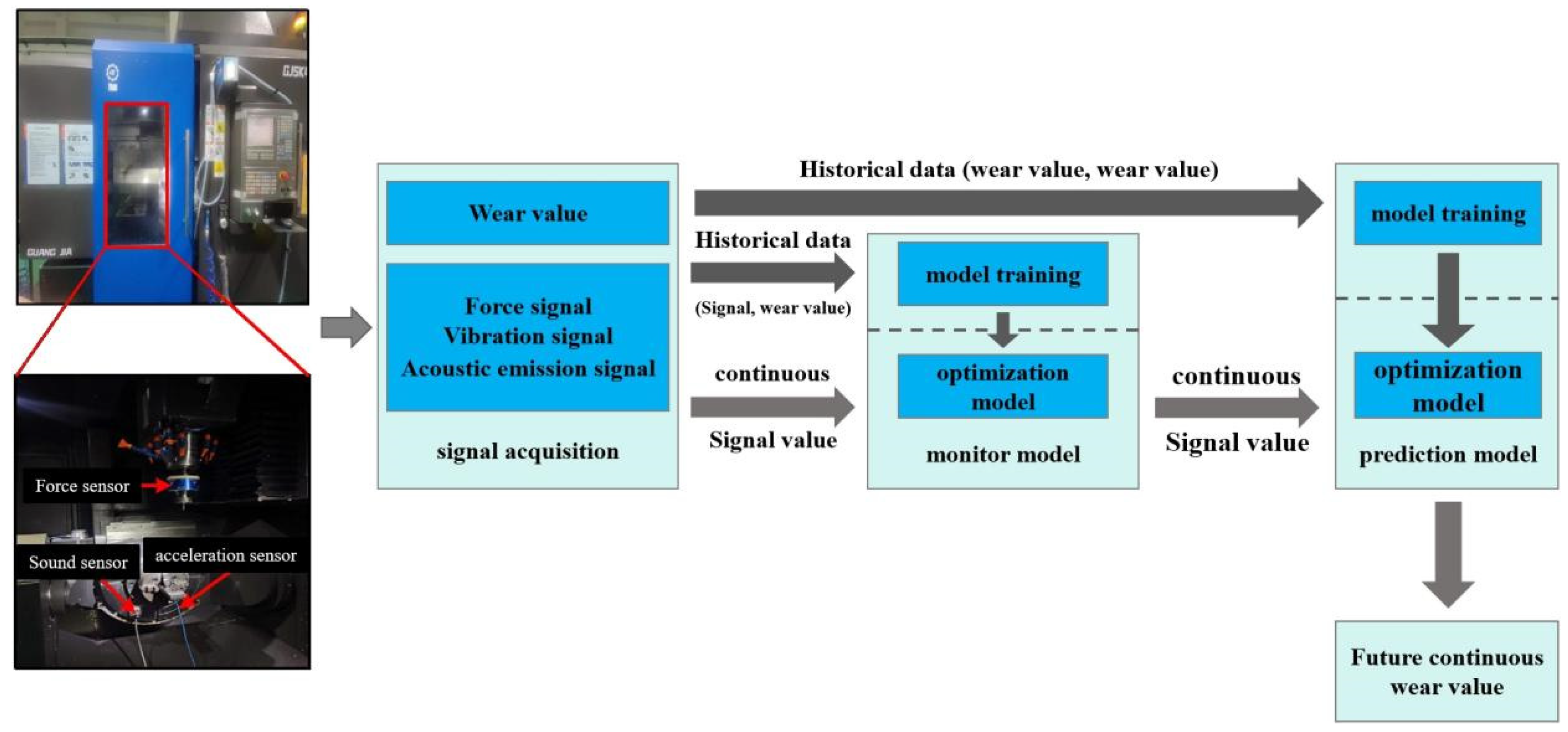

3.2. Multi Step Prediction Framework for Tool Wear

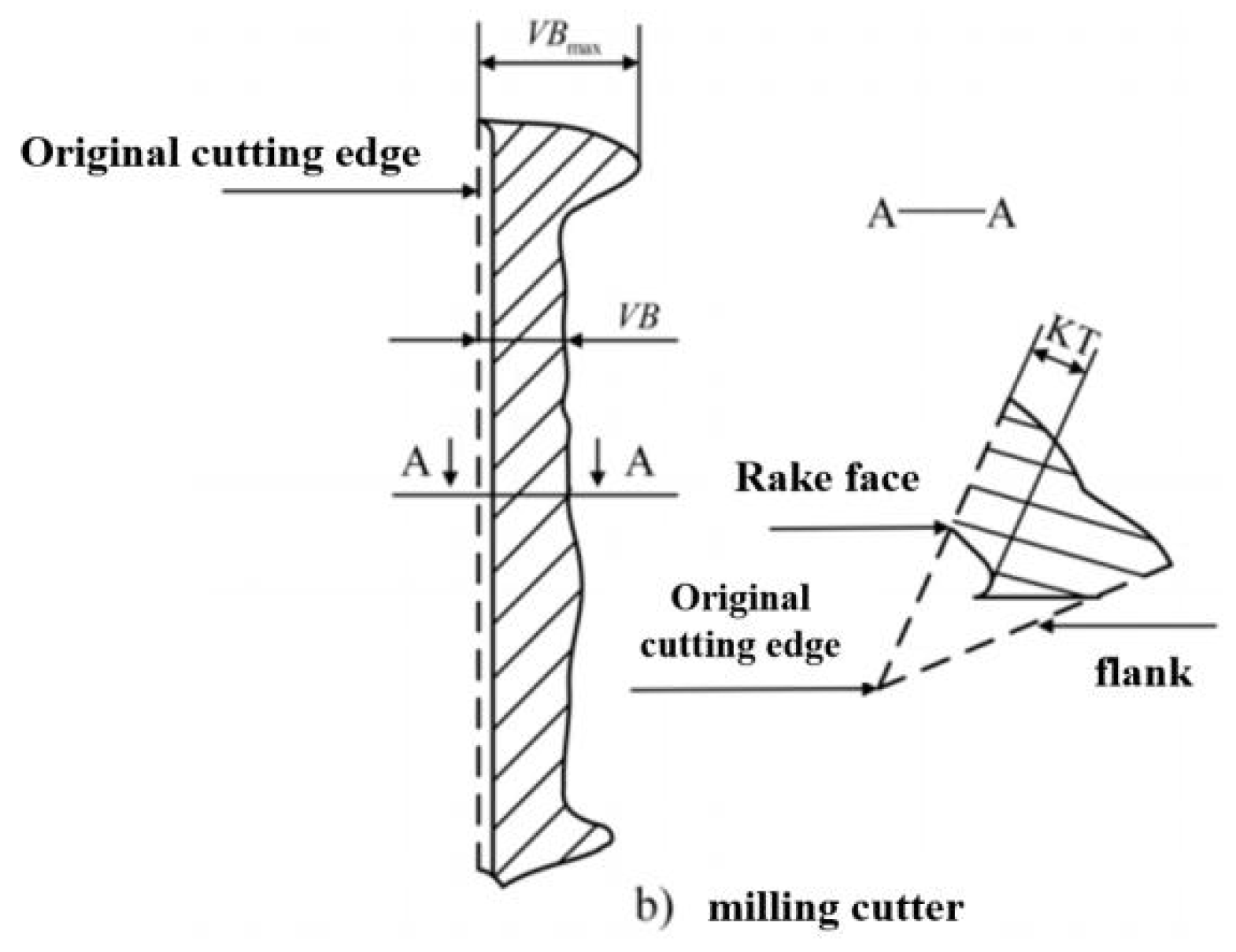

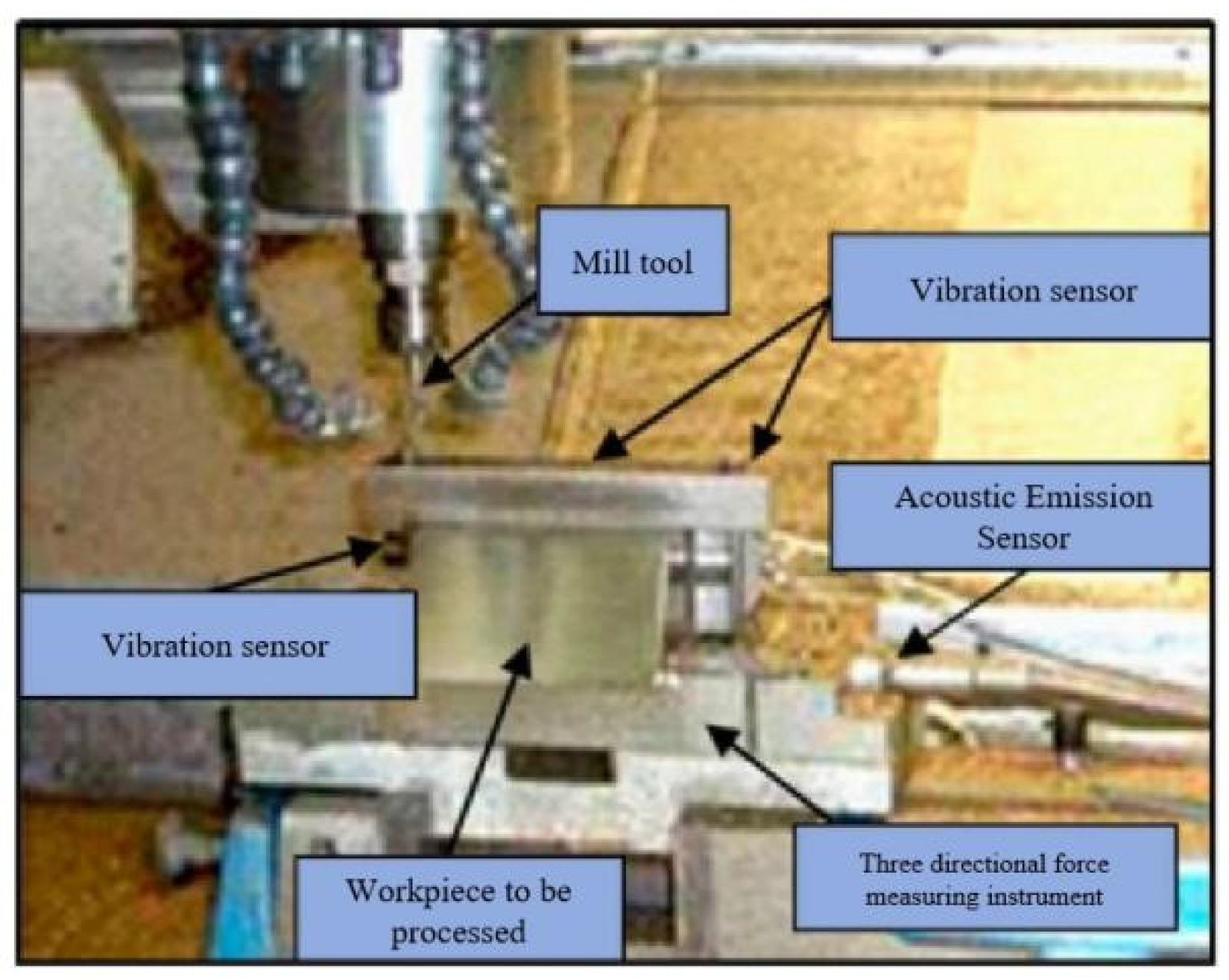

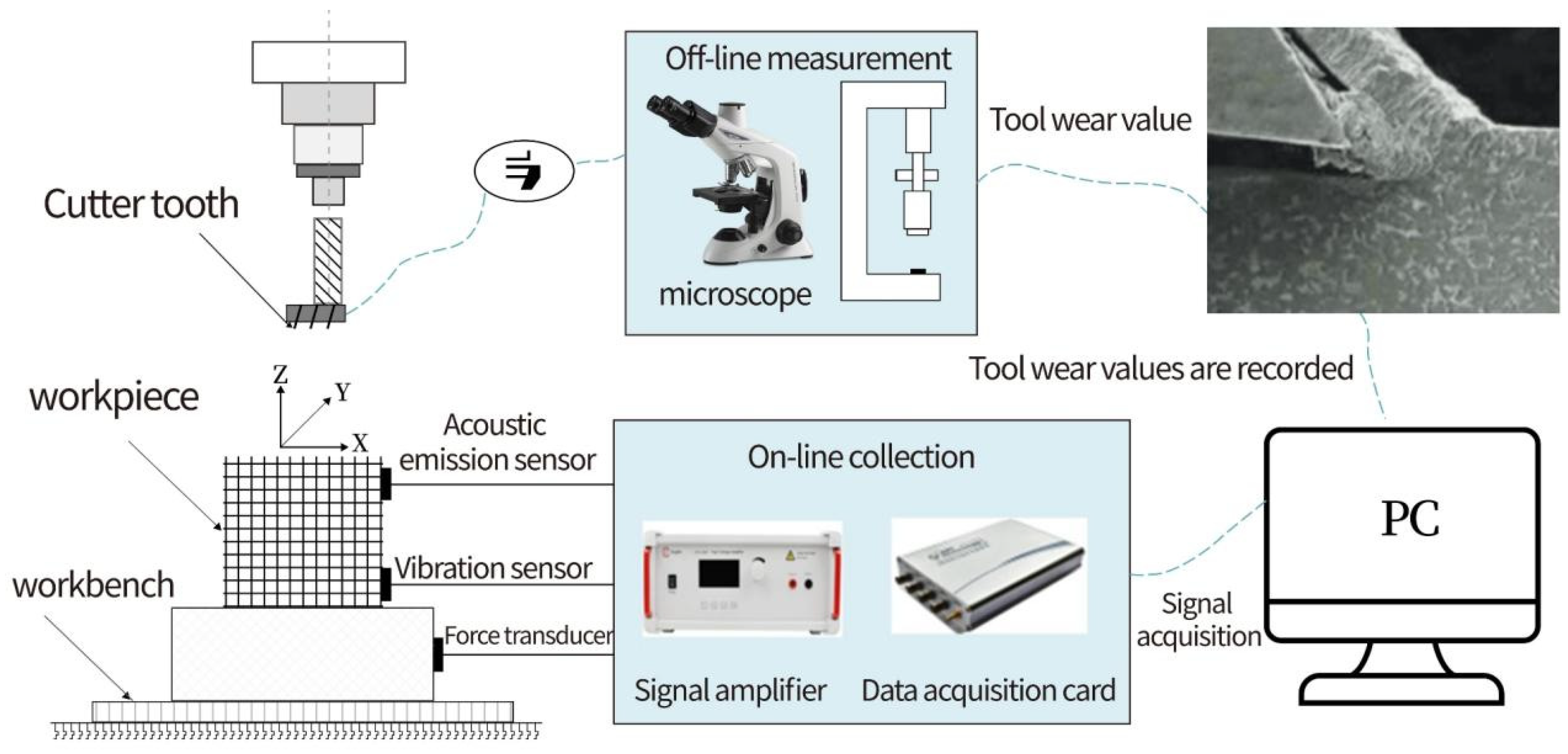

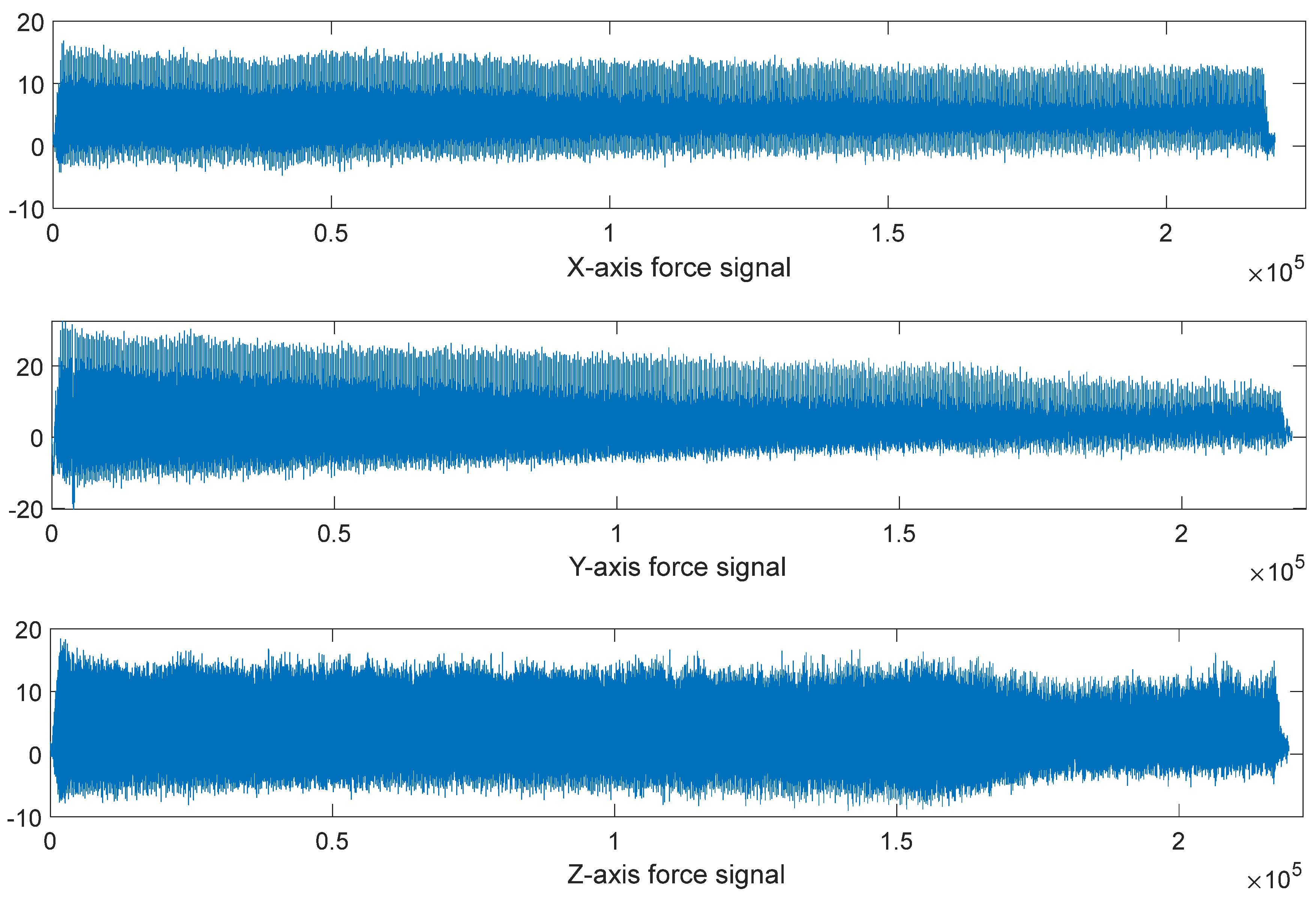

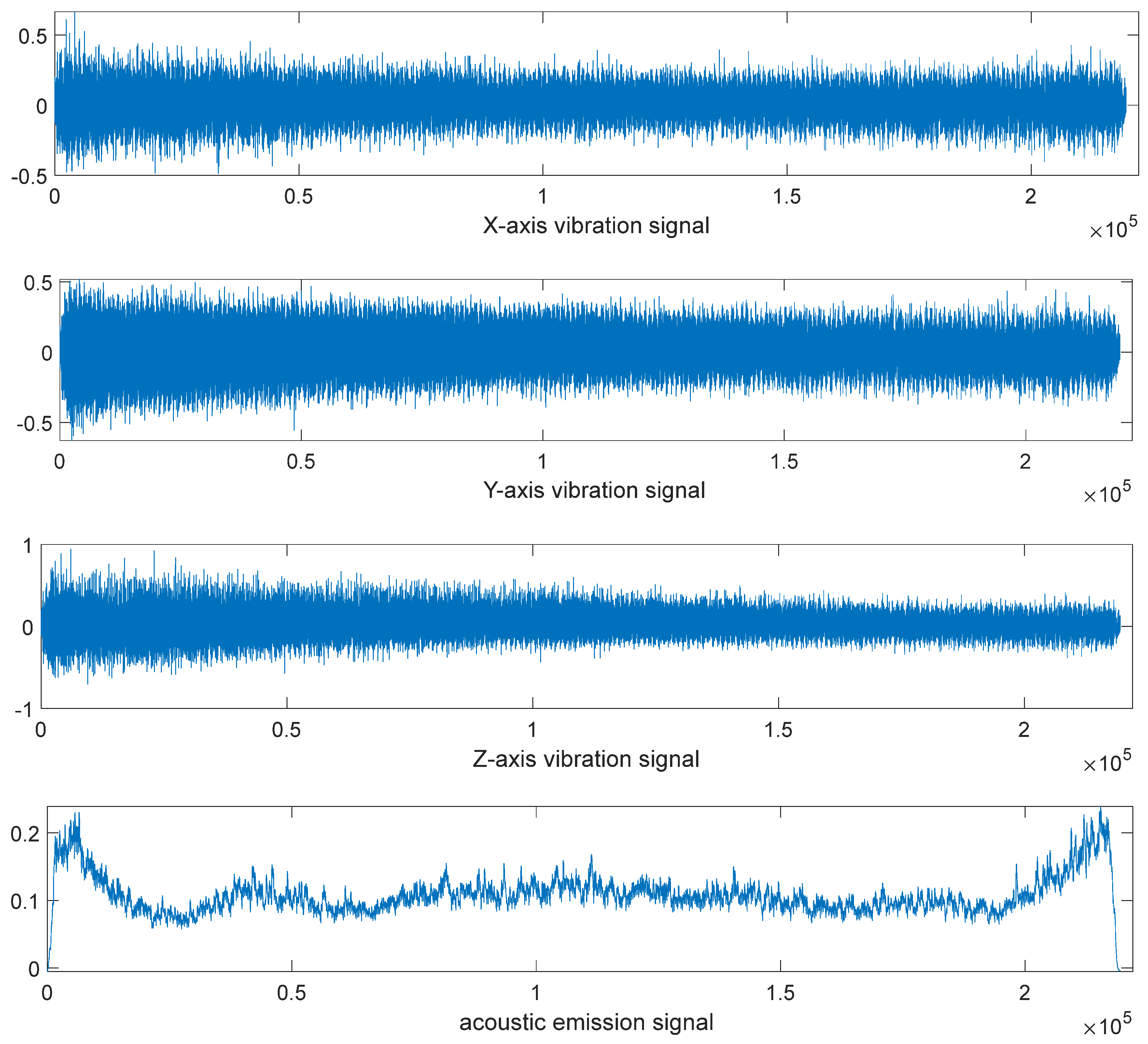

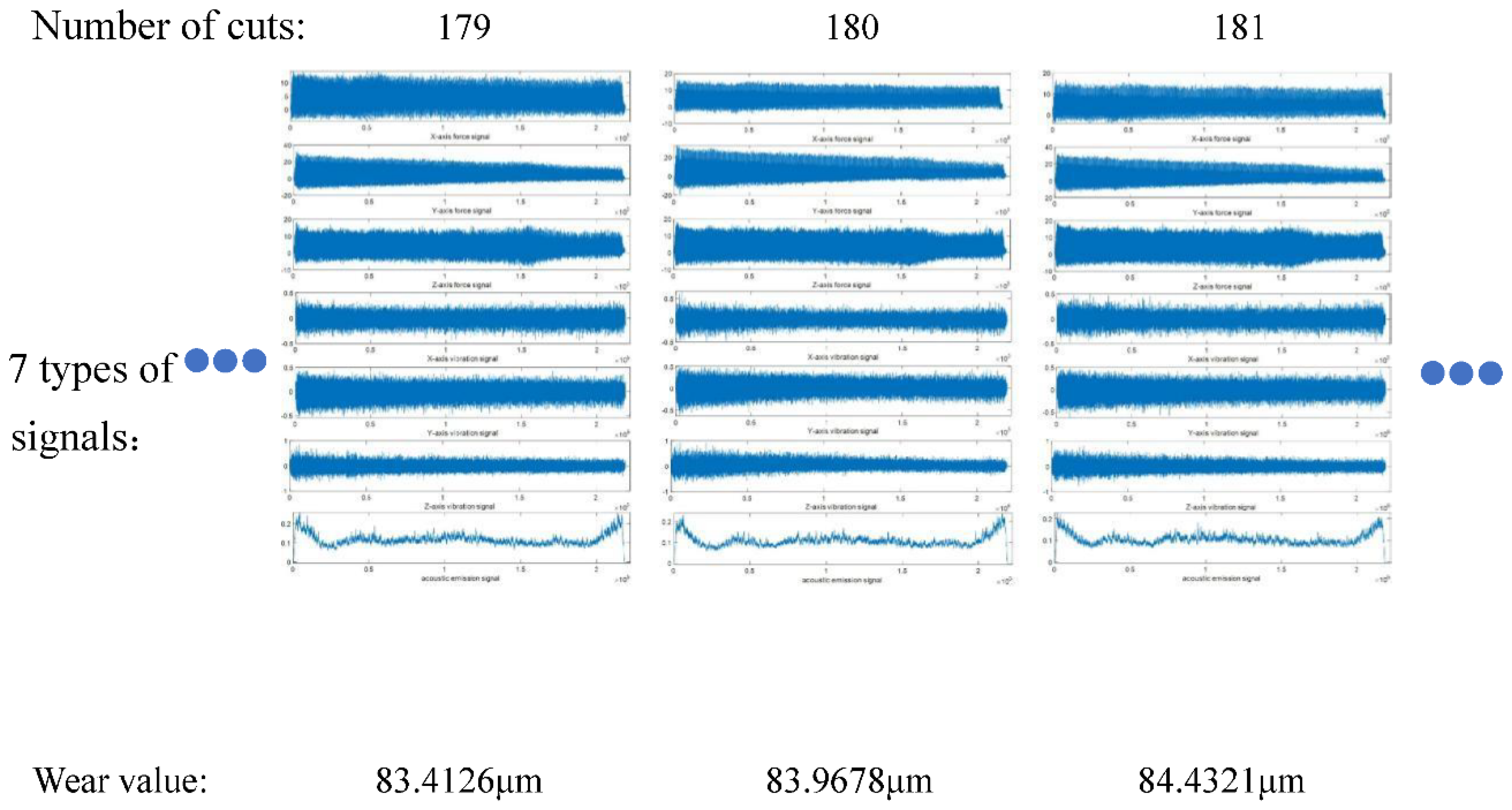

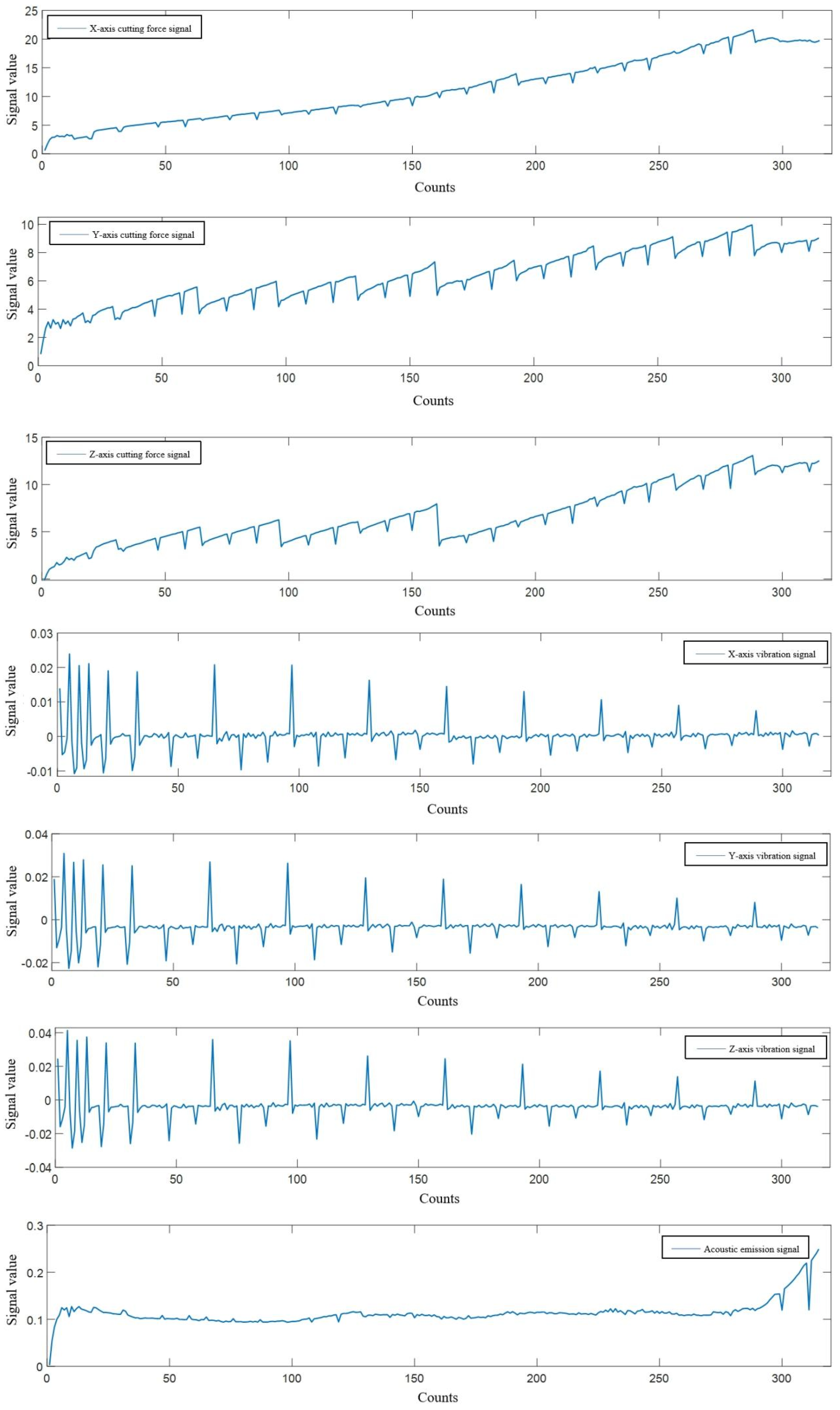

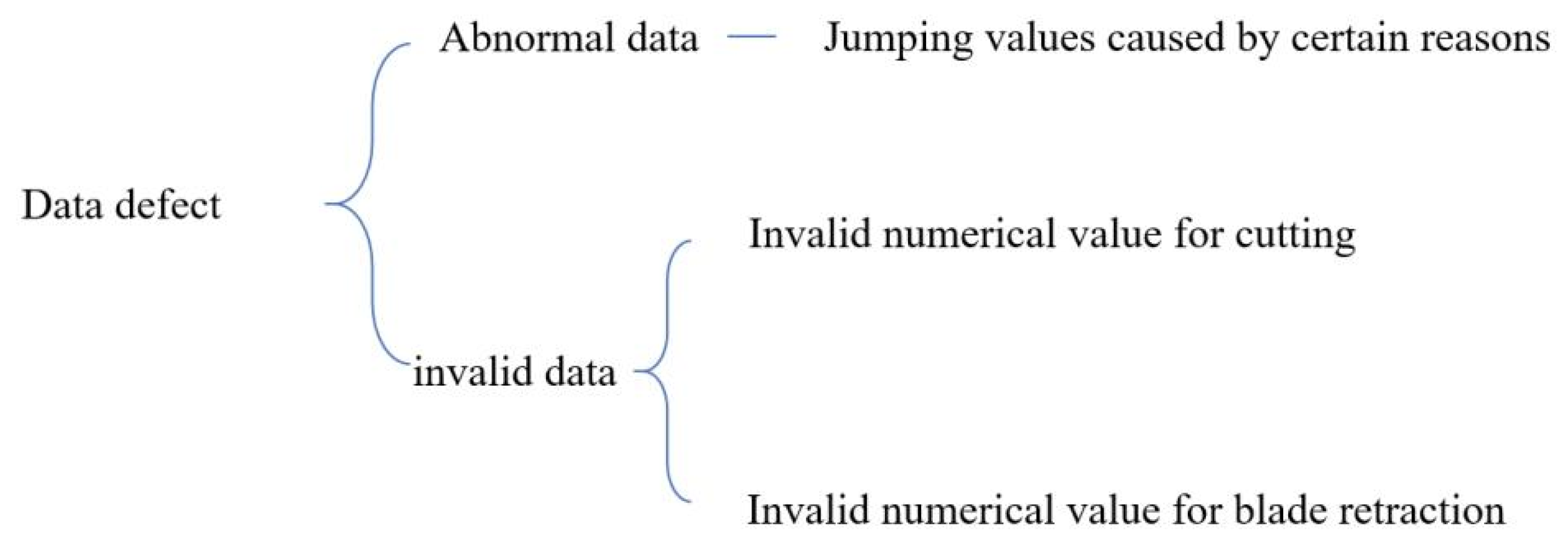

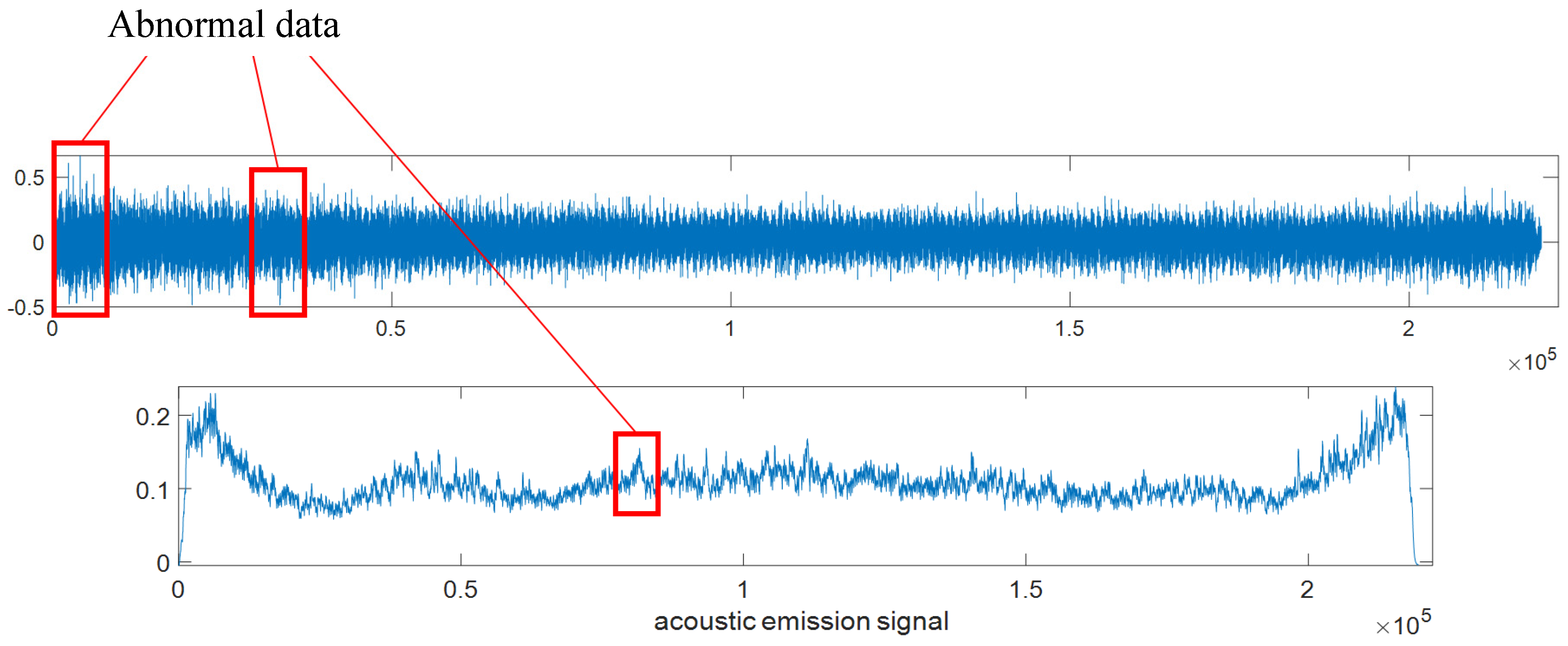

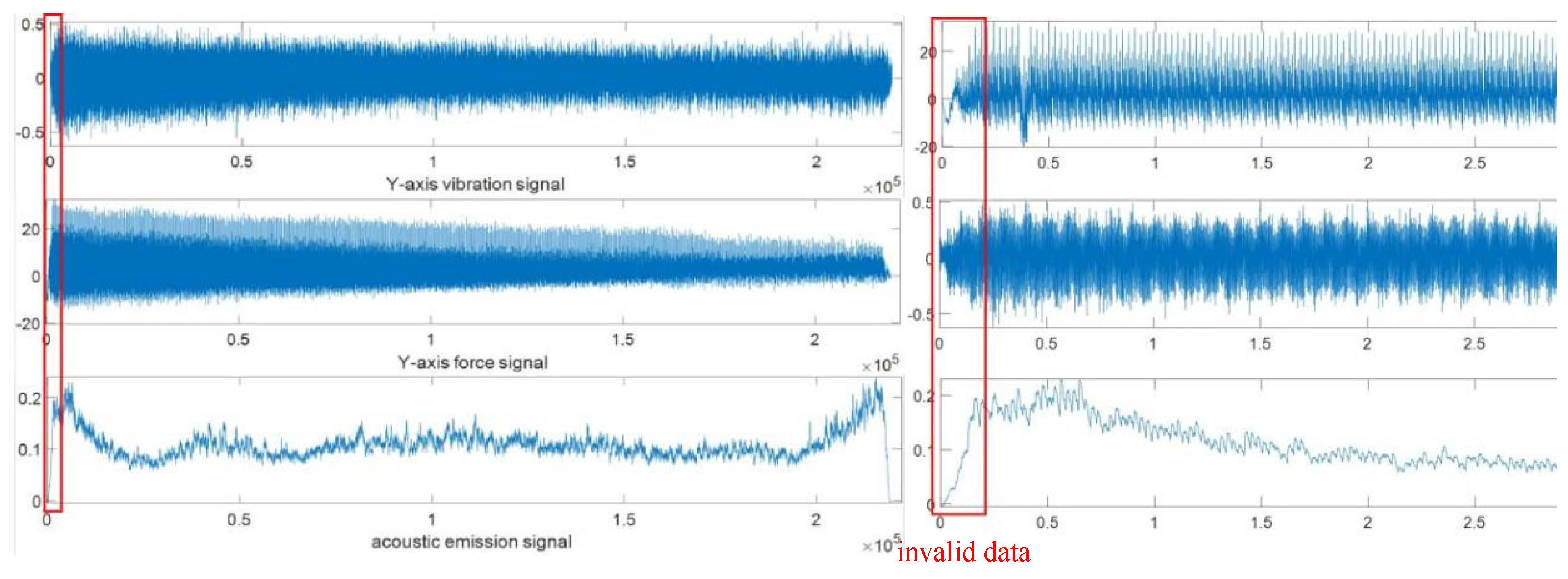

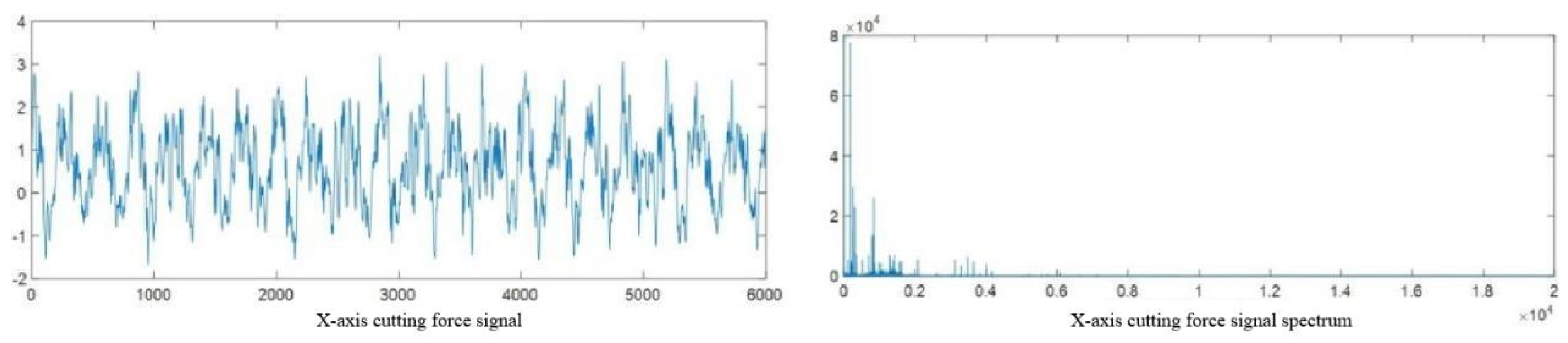

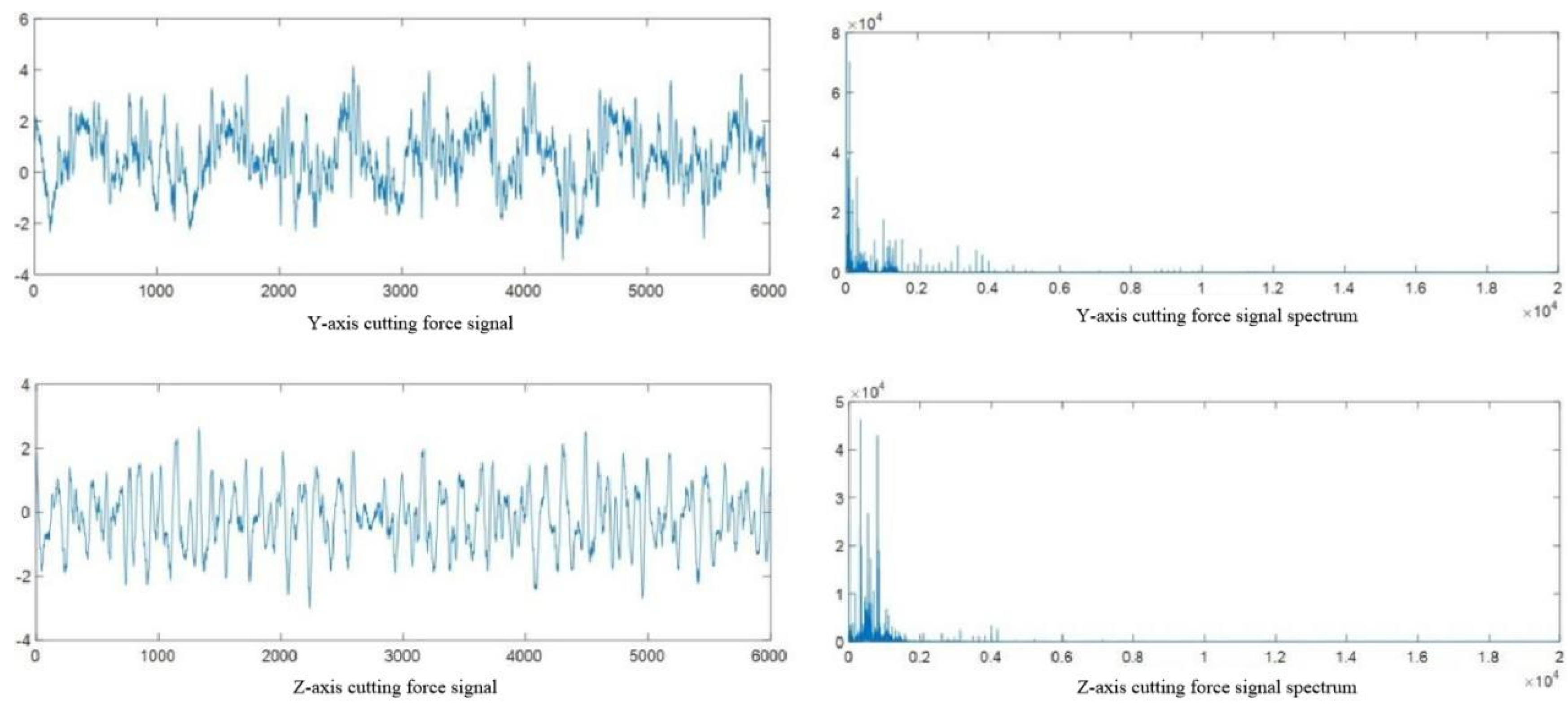

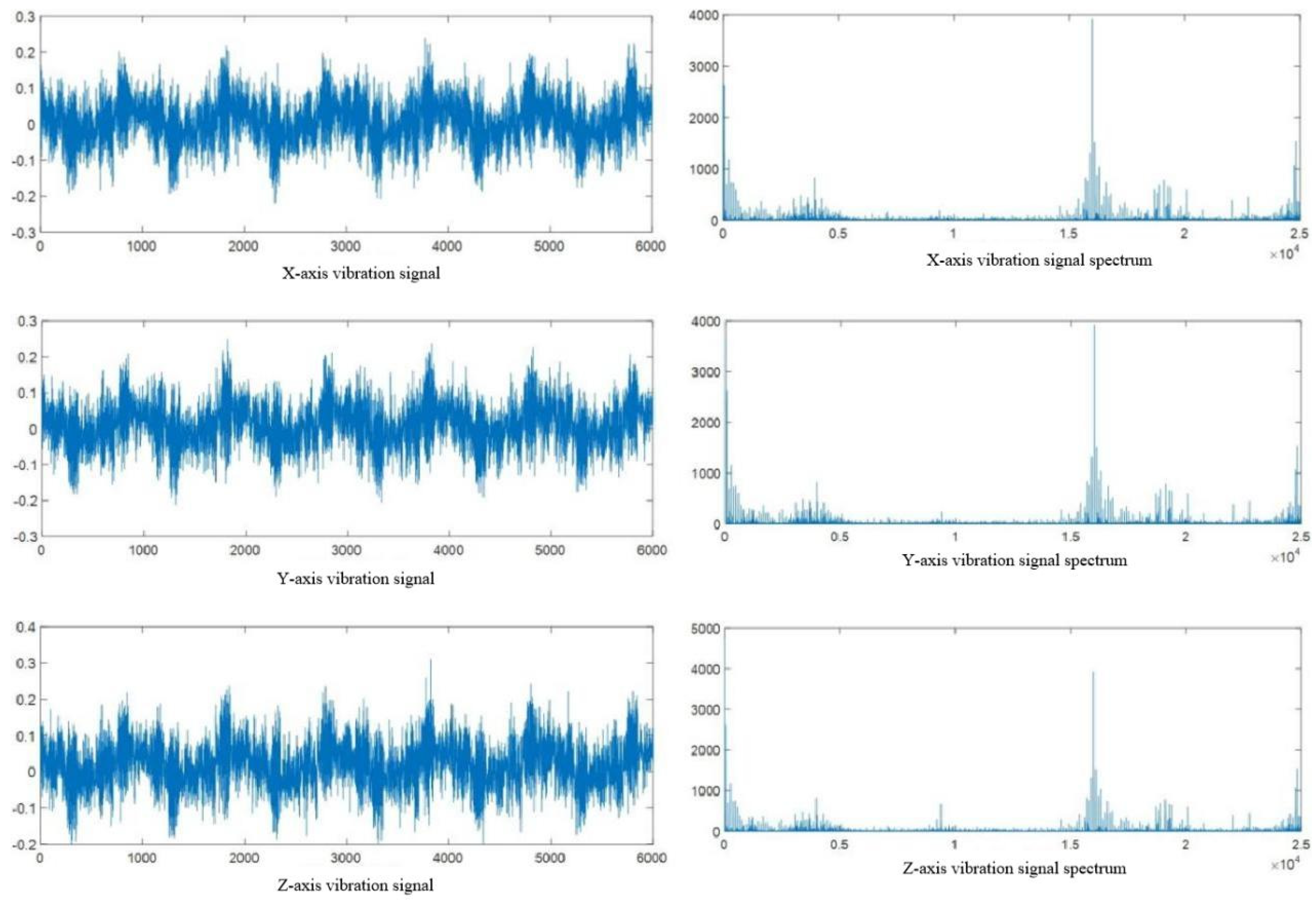

The complete multi-step tool wear prediction framework is illustrated in Figure 3.13. First, during high-speed milling, we collect machine tool status signals via high-precision sensors, including vibration, cutting force, and acoustic emission signals. Simultaneously, we measure the tool’s wear value for each signal, forming a dataset with inputs and corresponding wear values, serving as the basis for future monitoring and prediction models.

Next, the collected signals are input into our pre-established and optimized tool wear monitoring model, based on machine learning or advanced modeling techniques. After training, the model accurately correlates signals with wear values, outputting the current wear value upon input. By continuously inputting signals, we obtain wear values at multiple consecutive time points, reflecting wear changes throughout the machining process.

Finally, these continuous wear values are considered historical data and input into an optimized prediction model, trained to predict future wear based on historical data. This method allows obtaining future wear values at multiple consecutive time points, enabling early prediction of tool wear status.

Figure 3.13.

Multi-step Prediction Framework For Tool Wear.

Figure 3.13.

Multi-step Prediction Framework For Tool Wear.

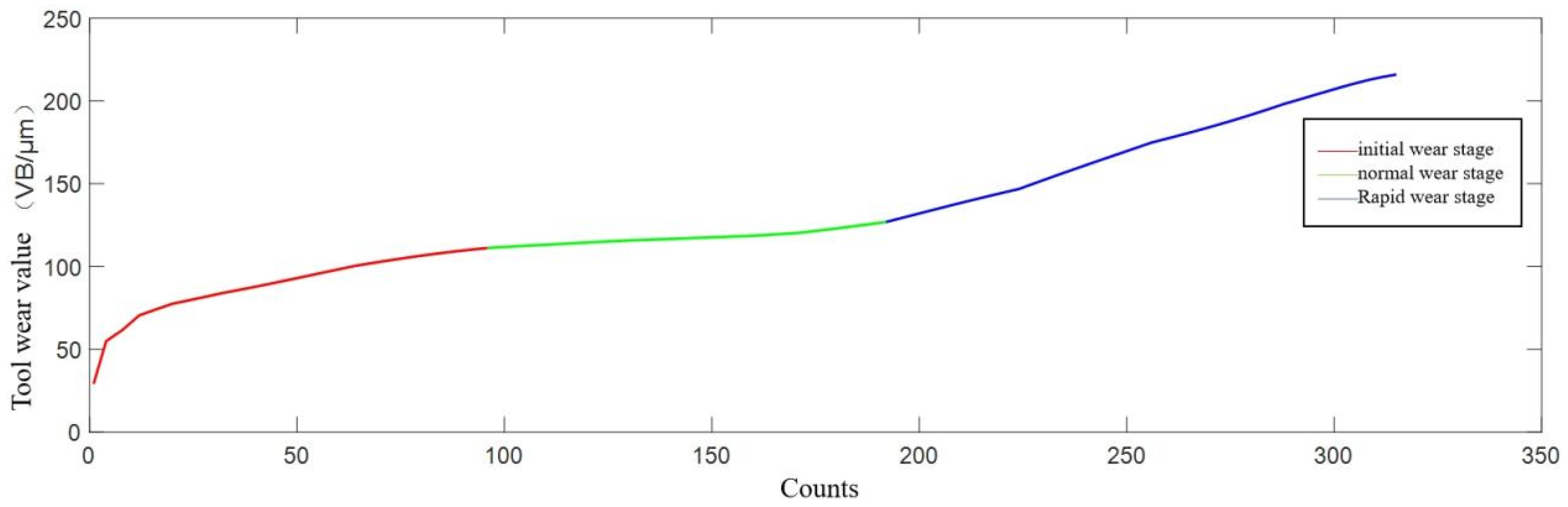

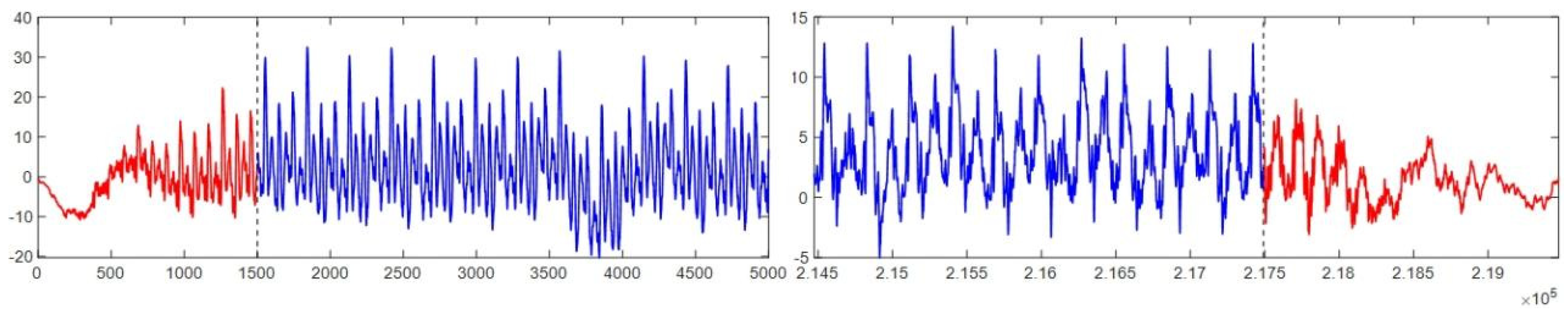

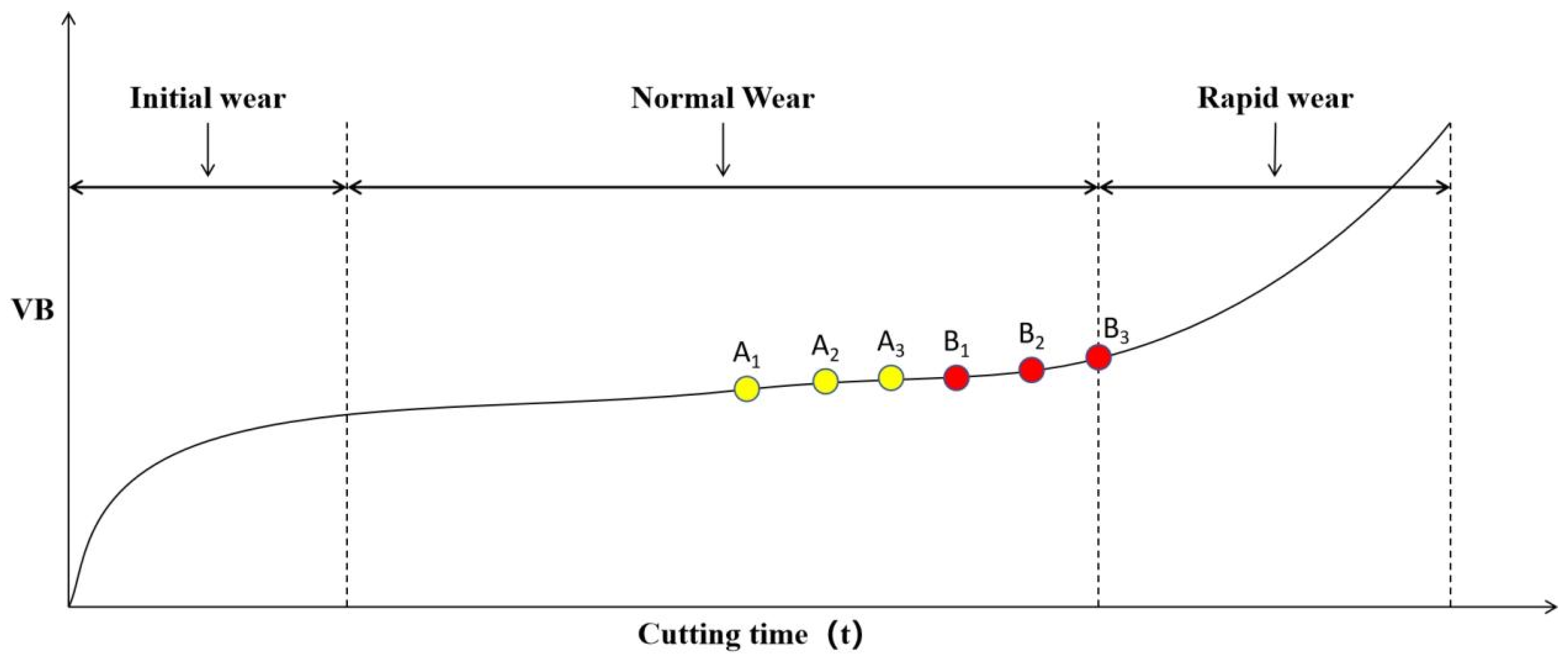

However, in the actual machining process, the machining conditions and tool states at two similar time points will be closer. As shown in Figure 3.14, the tool processing states of A3 and B1 are closer than those of A1 and B1, indicating that the influence of A3 on B1 should be greater than that of A1 on B1. Therefore, continuous multi segment sensor signals are used to monitor the current tool wear values as historical data, namely A1, A2, and A3, and then these historical data are used to predict the tool wear values for a future period of time, namely B1, B2, and B3. The impact of this historical data on the predicted data is different. To address this issue in the future, this chapter introduces the Attention mechanism to assign different weights to different historical input data.

Figure 3.14.

Tool wear curve.

Figure 3.14.

Tool wear curve.

3.3. Multi Step Prediction Comprehensive Model for Tool Wear

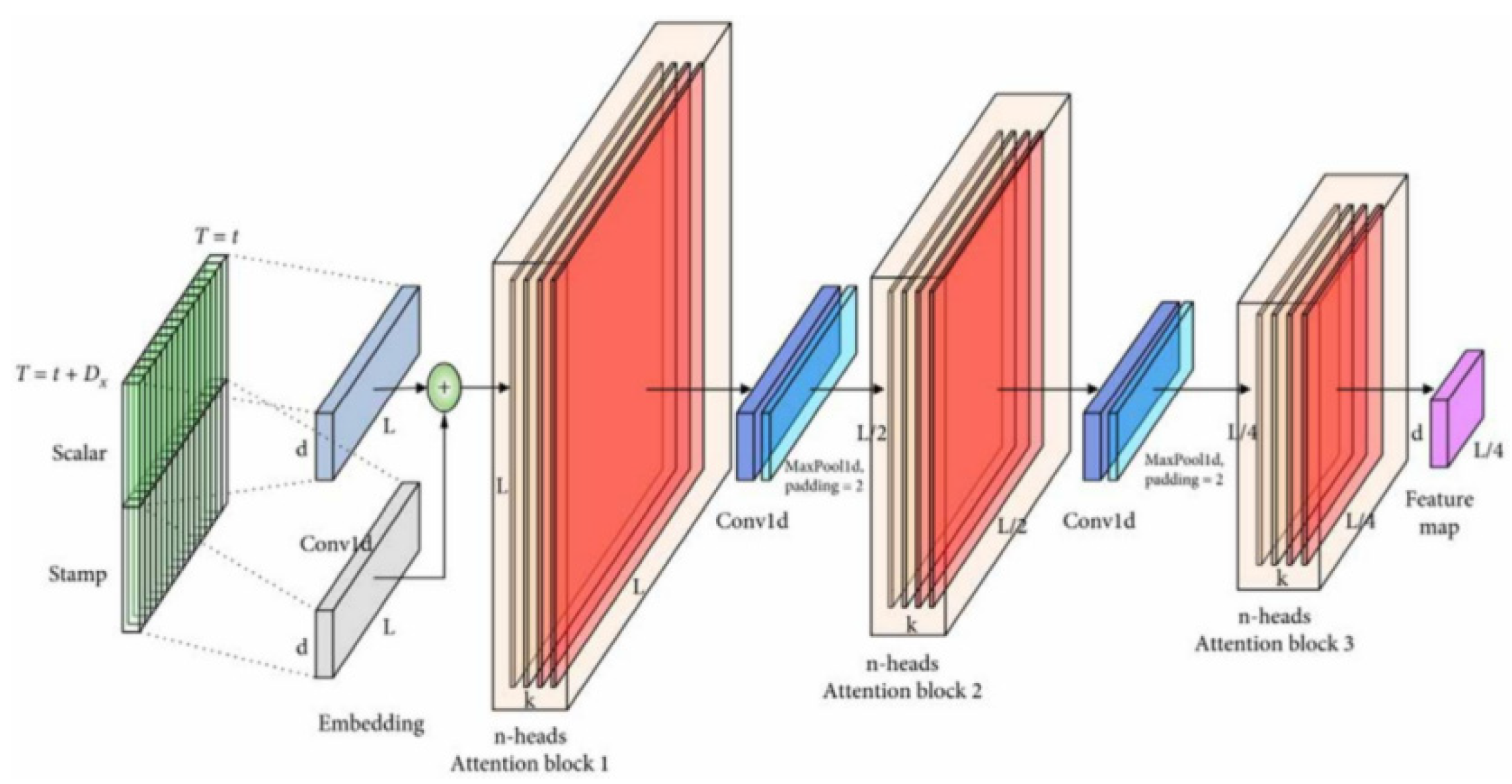

To achieve multi-step advanced prediction of tool wear while accounting for the varying influence of input at different times, we propose a comprehensive model based on the framework above. As shown in Figure 3.15, a tool wear monitoring model using Informer is established to correlate seven signals with wear values via the Informer network, enabling real-time wear monitoring. By inputting consecutive sensor signals, continuous historical wear data is obtained, referring to past wear values. These past wear values are then used to predict future wear.

An Encoder-Decoder framework with the Attention mechanism is adopted for the prediction model, using CNN as a feature extractor to enhance prediction accuracy. The Attention mechanism assigns varying weights to different time inputs, considering the non-uniform impact of past time points on future predictions, aiding in uncovering temporal data dependencies. The comprehensive model can be summarized as:

In the formula, xti - the i-th signal input at time t, i=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7;

Xt - Seven signal inputs at time t;

Yt - wear value at time t;

H - Monitoring model computation;

G - Prediction model operation.

Figure 3.

15. Schematic Diagram of Multi-step Prediction Comprehensive Model for Tool Wear.

Figure 3.

15. Schematic Diagram of Multi-step Prediction Comprehensive Model for Tool Wear.

3.3.1. Monitoring Model Based on Informer

The monitoring model based on Informer is shown in Figure 3.16. The input is a seven dimensional time series signal segment consisting of three-axis force signals, three-axis vibration signals, and acoustic emission signals, and the output is the wear value VB corresponding to the current signal segment.

Figure 3.16.

Monitoring Model Based on Informer.

Figure 3.16.

Monitoring Model Based on Informer.

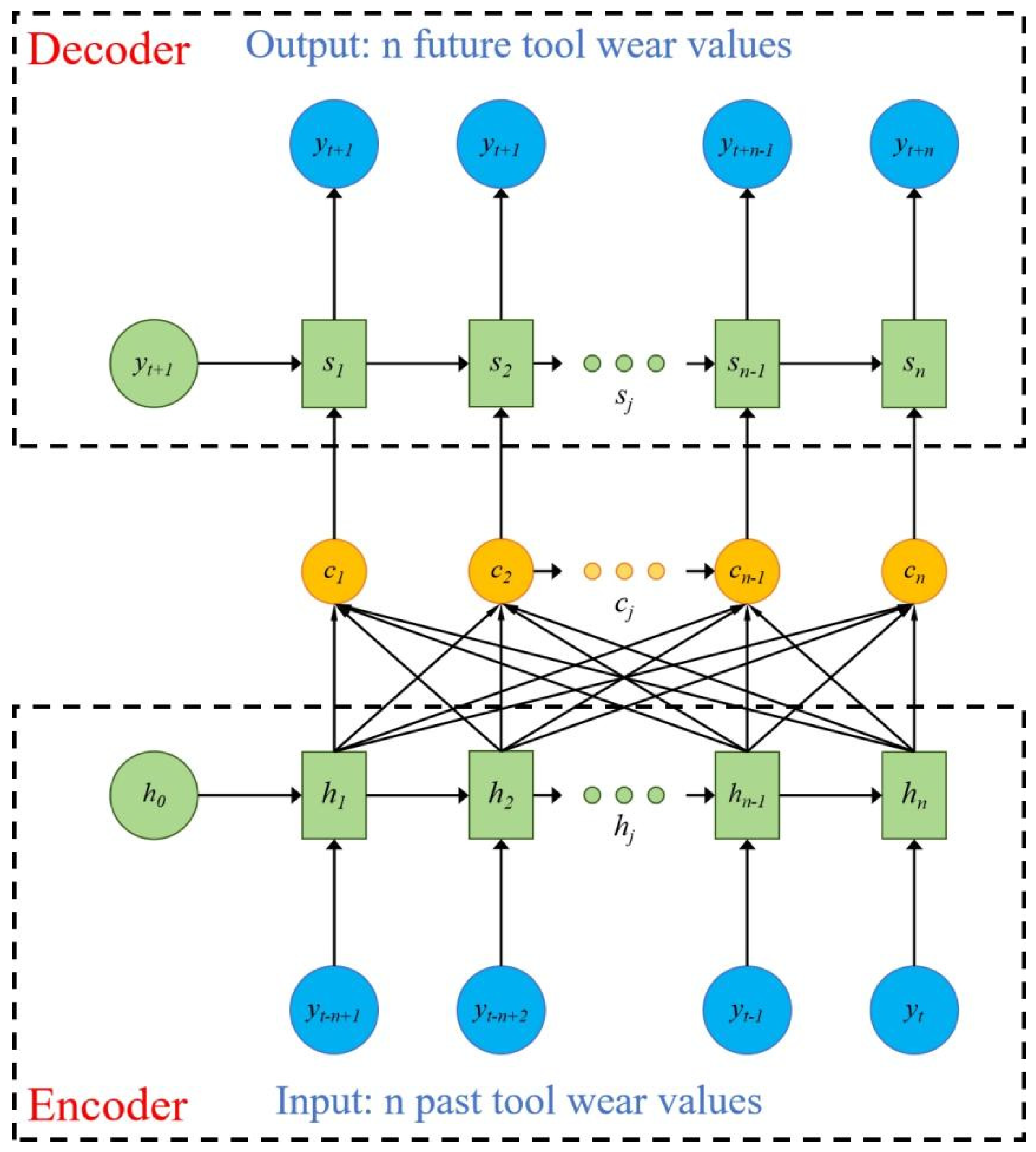

By monitoring the model, the tool wear value corresponding to the current signal segment can be obtained. Monitor the wear values of multiple past signal segments and use them as inputs for a predictive model to predict future tool wear values. As shown in Figure 3.17, the prediction model adopts the sequence to sequence structure in NLP, which connects the encoder and decoder with long and short-term information vectors with attention mechanism. The encoder and decoder both use the same GRU subunit, and each intermediate vector contains varying degrees of long and short-term information, depending on the weight assigned by the Attention mechanism. This mechanism can be represented by the following formula:

In the formula, hi represents the i-th hidden layer of the encoder;

Sj - the jth hidden layer of the decoder;

Eij - the similarity between vectors hi and sj-1, represented by Euclidean distance;

Aij - the weight of the i-th hidden layer in the encoder;

Cj - the jth hidden layer between the encoder and decoder.

Figure 3.17.

Encoder Decoder Prediction Model Based on Attention Mechanism.

Figure 3.17.

Encoder Decoder Prediction Model Based on Attention Mechanism.

Take multiple consecutive VB values measured recently in the past as inputs to the encoder module, represented by

.N represents the number of input data, which is the number of prediction steps. In the decoder module, n consecutive predicted future VB values will be output,represented by x

.Therefore, the model can be represented as:

In the formula, yt represents the wear value at time t;G - Prediction model operation.

3.4. Model Experiment and Result Analysis

3.4.1. Data Settings

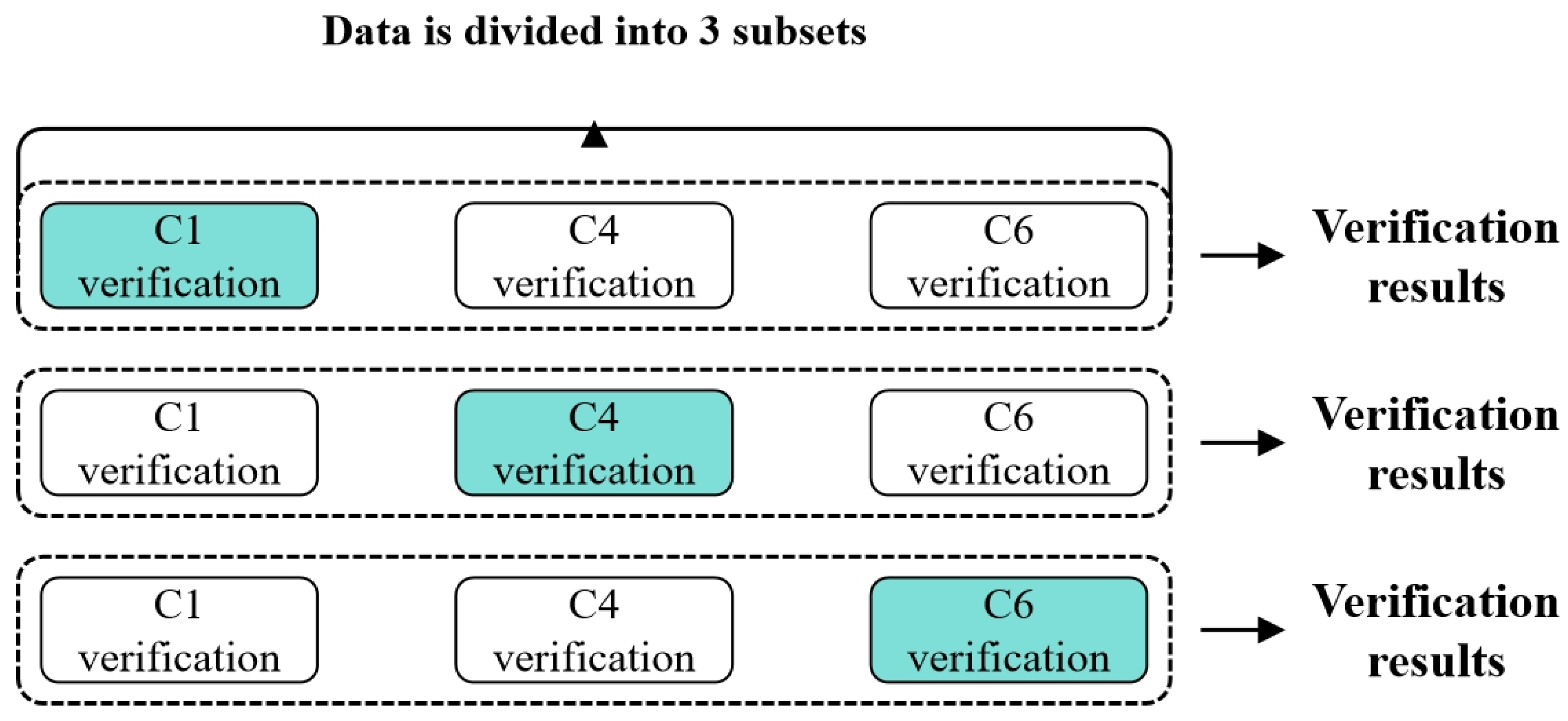

The preprocessed single condition PHM2010 dataset was subjected to three fold cross validation according to C1, C4, and C6, as shown in Figure 3.18. The maximum value of tool wear in three directions was used as a label for model training. The model was updated with weights and bias parameters using a backpropagation algorithm based on the chain rule to minimize the loss function. To validate the predictive performance of the model, the validation set data is input into the trained model to obtain the prediction results of tool wear.

Figure 3.18.

Cross Validation.

Figure 3.18.

Cross Validation.

3.4.2. Evaluation Criteria

In order to more accurately represent the fitting effect of the model on tool wear monitoring values and real values, and verify the accuracy of the prediction model, based on the regression algorithm evaluation system, this paper objectively evaluates the experimental results using four evaluation indicators, namely mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE), R-squared value (R-squared), and mean absolute error (MAE). The above evaluation indicators are widely used in regression problems. For the prediction task of tool wear in this article, the formula for evaluation indicators is as follows:

Among them, N represents the number of samples, i represents the sample number, represents the i-th tool wear prediction value, is the average of the actual values, represents the actual value of tool wear for the i-th tool.The ranges of root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) are both greater than or equal to zero. When the monitored tool wear value matches the actual tool wear value completely, both RMSE and MAE are zero; When the RMSE and MAE values are higher, it indicates that the model’s prediction accuracy is lower and cannot effectively predict tool wear values.

3.4.3. Experimental Setup

This chapter conducts experiments on the Windows 11 operating system, using PyTorch 2.3.1 and Python 3.9 to build a network and conduct experiments. The experimental hardware platform includes AMD Ryzen 7 6800H@3.20 A GHz CPU with a running memory of 32 GB and an NVIDIA RTX3060 acceleration graphics card with a graphics memory size of 12 GB. The specific experimental configuration is shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1.

The experimental environment.

Table 3.1.

The experimental environment.

| Software and Hardware |

Name |

Notes |

| CPU |

AMD Ryzen 7 6800H |

6 cores and 12 threads |

| GPU |

NVIDIA RTX3060 |

12GB video memory |

| operating system |

Windows |

11th generation |

| development language |

Python |

3.9.1 |

| development platform |

Pycharm |

2021.3.2 |

| Deep Learning Framework |

Pytorch |

2.3.1 |

| GPU acceleration component |

CUDA Toolkit |

11.8 |

To enhance model performance and suppress overfitting, a batch strategy is employed for training, expediting the process and improving generalization. Adam optimizer with a step decay strategy for learning rate reduction, coupled with Dropout regularization and early stopping, further prevents overfitting. Hyperparameters are selected via grid search on the validation set, with the optimal combination shown in Table 3.2. This configuration is consistent across comparison and ablation experiments for reliability.

Table 3.2.

Hyperparameter setting.

Table 3.2.

Hyperparameter setting.

| Hyper-Parameters |

Describe |

Numerical/Method |

| Epoch |

Training epochs |

500 |

| Batch size |

batch size |

30 |

| Learning rate |

Learning rate |

0.001 |

| Gamma |

Learning rate adjustment multiplier |

0.5 |

| Step size |

The number of intervals between a decrease in learning rate |

50 |

| Activation Function |

activation function |

ReLU |

| Dropout |

Discard rate |

0.3 |

3.4.4. Model Parameter Determination Experiment

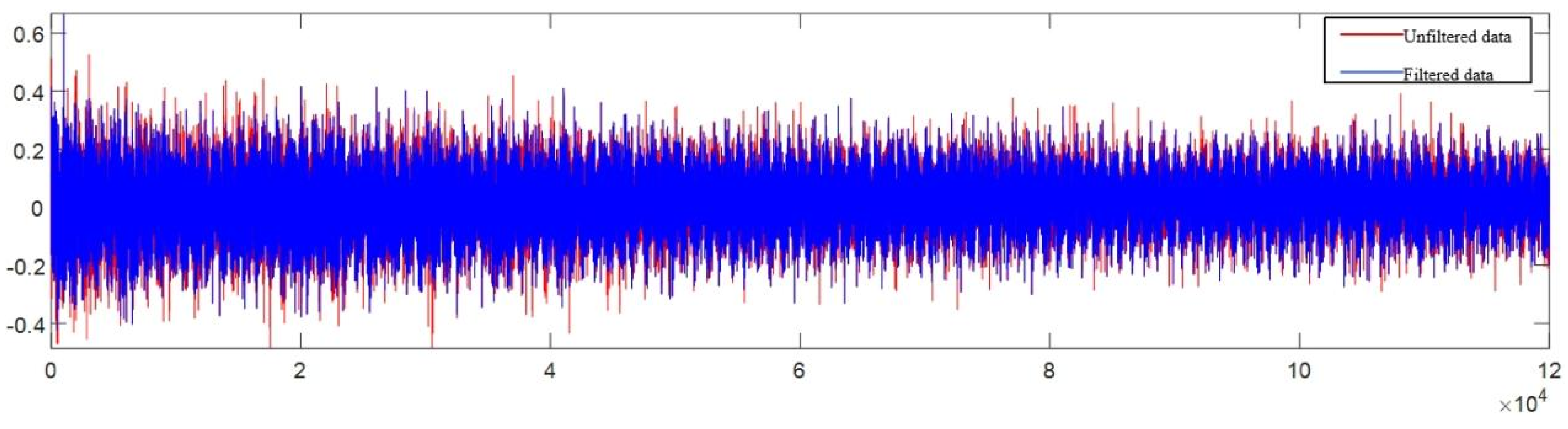

This chapter explores the effects of downsampling on sensor data integrity and how model parameters shape experimental outcomes. Using C1 and C6 as training sets and C4 as the validation set, we assess various factors’ impacts. By analyzing different downsampled time series lengths, we evaluate data loss’s effect on model performance. Table 3.3 shows the results: shorter downsampling lengths lead to significant data loss and model errors during training and testing. To balance information integrity and computational efficiency, we chose 5000 data points as the downsampled length. This approach minimizes information loss, maintains high training and validation accuracy, reduces computational load, prevents overfitting, and enhances the model’s generalization to new data.

Table 3.3.

Comparison of length results after downsampling.

Table 3.3.

Comparison of length results after downsampling.

| Length of Time Series Data After Downsampling |

MSE |

RMSE |

R2

|

MAE |

| 100 |

1,184.942 |

34.423 |

0.874 |

29.687 |

| 500 |

658.230 |

25.656 |

0.882 |

18.334 |

| 1000 |

358.913 |

18.945 |

0.896 |

14.878 |

| 2000 |

264.160 |

16.253 |

0.901 |

10.694 |

| 3000 |

249.293 |

15.789 |

0.940 |

8.687 |

| 4000 |

68.310 |

8.265 |

0.976 |

5.768 |

| 5000 |

5.890 |

2.427 |

0.993 |

2.362 |

| 6000 |

13.323 |

3.650 |

0.983 |

2.679 |

To determine optimal tool wear prediction model parameters, experiments were conducted to confirm neural network layer sizes, including convolutional layer sizes and the sampling factor of the probabilistic sparse self-attention mechanism. In convolutional neural networks, convolution kernel size impacts feature capture range; inappropriate sizes lead to inaccurate feature extraction. Probabilistic sparse self-attention reduces complexity while maintaining performance; sampling factor selection affects long-range dependency capture and efficiency. Table 3.4 illustrates convolution kernel size effects on prediction results, using MSE, RMSE, R-squared, and MAE for evaluation.

Table 3.4.

Effect of convolution kernel size on experimental results.

Table 3.4.

Effect of convolution kernel size on experimental results.

| Convolutional kernel size |

MSE |

RMSE |

R2

|

MAE |

| 1 |

13.609 |

3.689 |

0.891 |

5.014 |

| 2 |

10.081 |

3.175 |

0.928 |

4.785 |

| 3 |

8.738 |

2.956 |

0.956 |

4.598 |

| 4 |

4.951 |

2.225 |

0.994 |

3.254 |

| 5 |

22.043 |

4.695 |

0.986 |

5.201 |

| 6 |

18.931 |

4.351 |

0.975 |

5.469 |

| 7 |

17.986 |

4.241 |

0.981 |

5.954 |

The experimental results indicate that a convolution kernel size of 4 yields the best prediction performance, enabling better local feature capture. Hence, a kernel size of 4 is used in subsequent experiments.

The sampling factor c in probabilistic sparse self-attention significantly impacts model performance. Table 3.5 shows that c=15 offers optimal performance, as it balances the trade-off between computational efficiency and information richness, ensuring efficient sequence data handling.

Table 3.5.

Influence of sampling factor c on experimental results.

Table 3.5.

Influence of sampling factor c on experimental results.

| Sampling Factor Size |

MSE |

RMSE |

R2

|

MAE |

Training time (s) |

| 1 |

36.978 |

6.081 |

0.872 |

7.974 |

668 |

| 3 |

33.651 |

5.801 |

0.897 |

7.161 |

1012 |

| 5 |

27.164 |

5.212 |

0.923 |

6.091 |

1237 |

| 7 |

21.836 |

4.673 |

0.931 |

5.922 |

1453 |

| 9 |

12.996 |

3.605 |

0.955 |

5.687 |

1503 |

| 11 |

6.325 |

2.515 |

0.971 |

4.230 |

1613 |

| 13 |

5.579 |

2.362 |

0.989 |

3.986 |

1527 |

| 15 |

4.674 |

2.162 |

0.991 |

3.636 |

2129 |

| 17 |

9.960 |

3.156 |

0.990 |

4.579 |

2263 |

| 19 |

10.634 |

3.261 |

0.975 |

4.307 |

2372 |

| 21 |

20.277 |

4.503 |

0.971 |

6.079 |

2656 |

After determining the optimal network parameter model, the relevant hyperparameters of each layer for the CNN Informer neural network model proposed in this chapter are shown in Table 3.6.

Table 3.6.

Neural network model hyperparameters.

Table 3.6.

Neural network model hyperparameters.

| Network Layer |

Parameter |

Output Matrix Dimension |

| Input |

- |

(5000, 7) |

| Convolutional Layer |

Kernel=4, Stride=4, output channel=128 |

(1250, 128) |

| Maximum pooling layer |

Kernel=3, Stride=2 |

(624, 128) |

| Probabilistic Sparse Self Attention Mechanism 1 |

Head number=8, c=15 |

(624, 128) |

| Distillation layer 1 |

Conv1d: Kernel=3, Stride=2, channel=128

Maxpooling: Kernel=3, Stride=2 |

(155, 128) |

| Probabilistic Sparse Self Attention Mechanism 2 |

Head number=8, c=15 |

(155, 128) |

| Distillation layer 2 |

Conv1d: Kernel=3, Stride=2, channel=72

Maxpooling:Kernel=3, Stride=2 |

(38, 72) |

| Probability Sparse Self Attention Mechanism 3 |

Head number=8, c=15 |

(38, 72) |

| Distillation layer 3 |

Conv1d: Kernel=3, Stride=1, channel=64

Maxpooling: Kernel=3, Stride=2 |

(18, 64) |

| Fully connected layer |

Output dim = 64 |

(1, 64) |

| Fully connected layer |

Output dim = 16 |

(1, 16) |

| Fully connected layer |

Output dim = 1 |

(1, 1) |

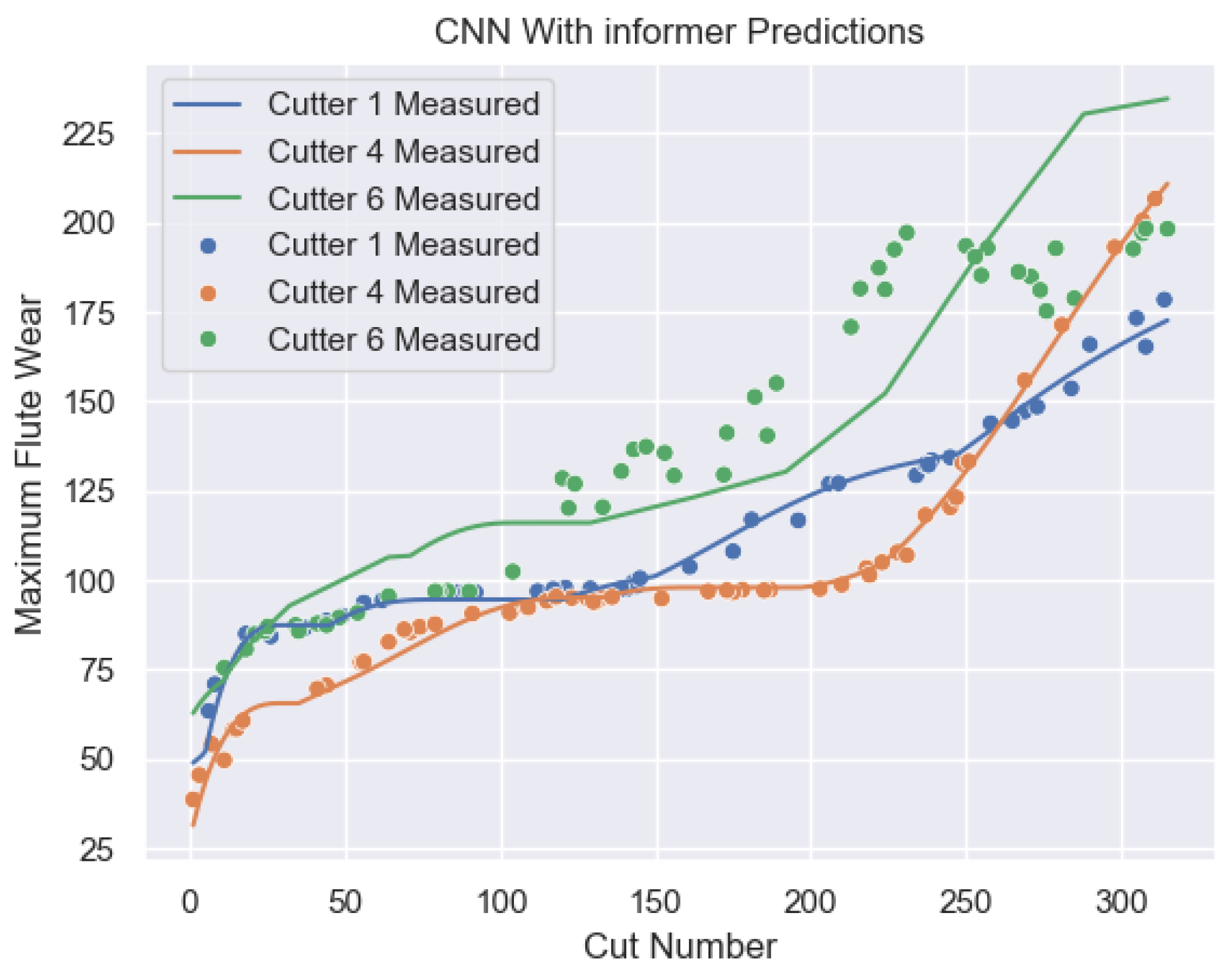

3.4.5. Experimental Result

In addition to training the results of the network model designed in this paper, the experiment also compared with a series of models such as one-dimensional convolutional neural model and Informer model, which verified that the network of a single module could not predict the tool wear accurately. Therefore, the neural network structure was improved by fusing the advantages of each module to obtain more accurate prediction values. The experimental results of the model proposed in this chapter are shown in the blue, orange, and green curves in Figure 3.14, which represent the tool wear prediction results for C1, C4, and C6, respectively.

Figure 3.19.

This paper presents the experimental results of cross-validation of the network model.

Figure 3.19.

This paper presents the experimental results of cross-validation of the network model.

To assess the network’s feature extraction effectiveness, we conducted a feature correlation analysis. We sampled high-dimensional features (dim: 1,64) before the fully connected layer and used Pearson correlation and mutual information to measure their relationship with the maximum tool wear (315 times C1 max). Pearson correlation, ranging from -1 to 1, indicates linear dependence, with higher values suggesting stronger correlation. Mutual information quantifies nonlinear correlations, with larger values indicating stronger dependence. Traditional machine learning sets a Pearson correlation threshold of 0.5 for feature selection. Our analysis (Table 3.9) revealed high Pearson and mutual information values, confirming strong linear and nonlinear correlations between extracted features and max wear.

Specifically, the Pearson correlation coefficients of some features are significantly higher than the threshold of 0.5, and the mutual information values also show significant values, which further confirms the effectiveness of these features. Therefore, these results not only support the effectiveness of network feature extraction, but also provide a strong feature foundation for subsequent model construction. Through this analysis, we can ensure that the features used not only meet traditional correlation standards, but also exhibit excellent performance within the framework of deep networks, providing a reliable basis for practical applications such as tool wear prediction.

Table 3.9.

High dimensional feature correlation.

Table 3.9.

High dimensional feature correlation.

| |

1st dimensional feature |

7th dimensional feature |

42nd dimensional feature |

60th dimensional feature |

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

0.9004 |

0.9273 |

0.8995 |

0.9615 |

| Mutual information |

0.8794 |

0.9864 |

0.8162 |

0.9946 |

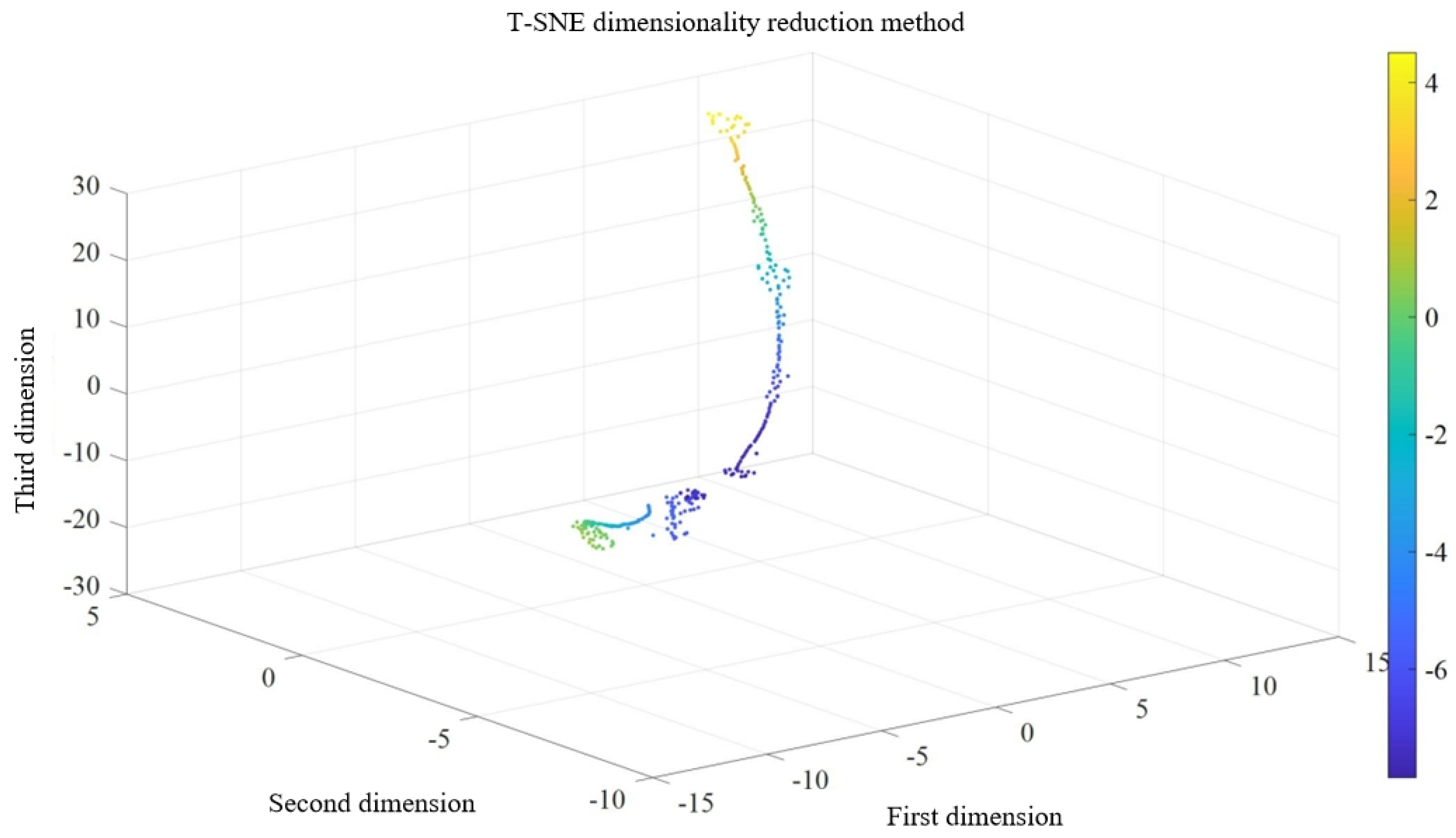

And high-dimensional features were reduced using T-SNE method, and the distribution of each sample’s features in three-dimensional space is shown in Figure 3.20. From the figure, it can be seen that the high-dimensional features extracted by the deep fusion neural network are automatically stacked together and distributed in three-dimensional space after dimensionality reduction. In the t-SNE graph, each data point represents a sample in the original high-dimensional space, and its position under the t-SNE mapping represents its position in the low dimensional space. There are natural clusters in the data points, which are presented in a tightly clustered form. Moreover, the data points are denser within the clusters, and the distance between different clusters is relatively far, which is consistent with the early, middle, and severe wear processes of the tool. This further proves that the network structure proposed in this paper can extract features with strong correlation with tool wear.

Figure 3.20.

t-SEN high dimensional feature distribution map.

Figure 3.20.

t-SEN high dimensional feature distribution map.

3.4.6. Comparative Experiment

To verify the superiority of multi-sensor data fusion (MSDF) technology, this study systematically evaluated the predictive performance of force signal sensors (FS), acceleration sensors (ACC), and acoustic emission sensors (AES) when used independently. The data from each sensor was separately introduced into the prediction model for tool wear detection. Research results (Table 3.8) revealed significant limitations of single sensors in capturing comprehensive tool wear information, leading to substantial deviations from actual wear situations.

Comparative analysis indicates that single sensors offer limited information, unable to cover complex tool wear changes, resulting in inaccurate predictions. Multi-sensor data fusion (MSDF) leverages the strengths of different sensors: force signal sensors track cutting force dynamics, acceleration sensors capture vibration characteristics, and acoustic emission sensors monitor internal stress and crack propagation. Integrating these multi-source data builds a more comprehensive tool wear model, significantly enhancing prediction accuracy and reliability. This validates the efficacy of MSDF in practical applications and provides a theoretical basis and technical pathway for optimizing prediction models and improving tool management efficiency.

Table 3.8.

High dimensional feature correlation.

Table 3.8.

High dimensional feature correlation.

| Types of sensors |

C1 |

C4 |

C6 |

| MAE |

R2

|

RMSE |

MAE |

R2

|

RMSE |

MAE |

R2

|

RMSE |

| Force Signal |

6.155 |

0.953 |

7.246 |

7.834 |

0.934 |

8.451 |

7.021 |

0.955 |

9.076 |

| acceleration signal |

6.795 |

0.941 |

8.314 |

7.596 |

0.952 |

9.772 |

6.750 |

0.975 |

8.312 |

| acoustic emission signal |

9.312 |

0.933 |

10.566 |

9.432 |

0.944 |

10.876 |

8.324 |

0.971 |

9.767 |

| Force and acceleration signals |

6.5 |

0.978 |

5.109 |

6.878 |

0.985 |

6.918 |

4.618 |

0.989 |

4.221 |

| Force, acceleration, and acoustic emission signals |

1.693 |

0.995 |

3.628 |

2.132 |

0.992 |

3.627 |

2.173 |

0.997 |

3.159 |

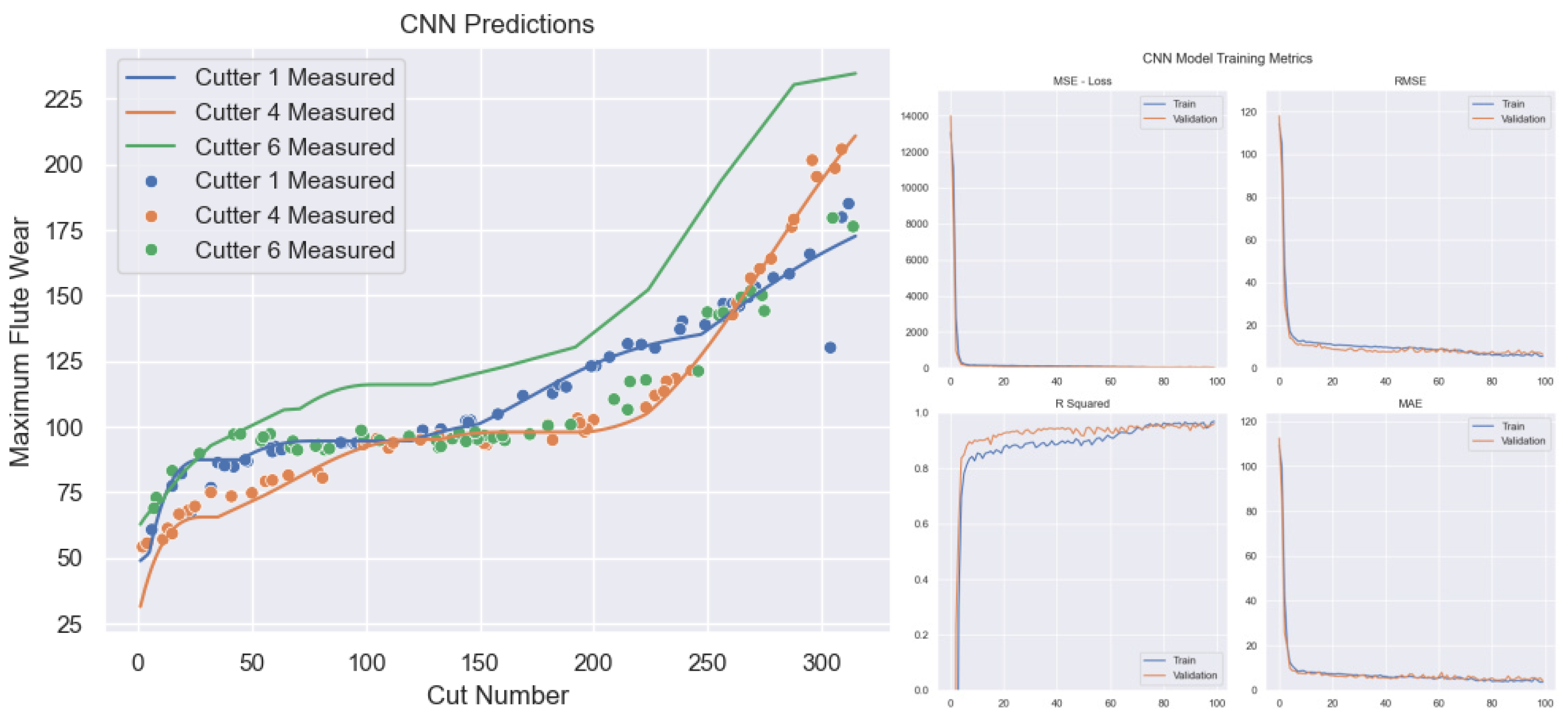

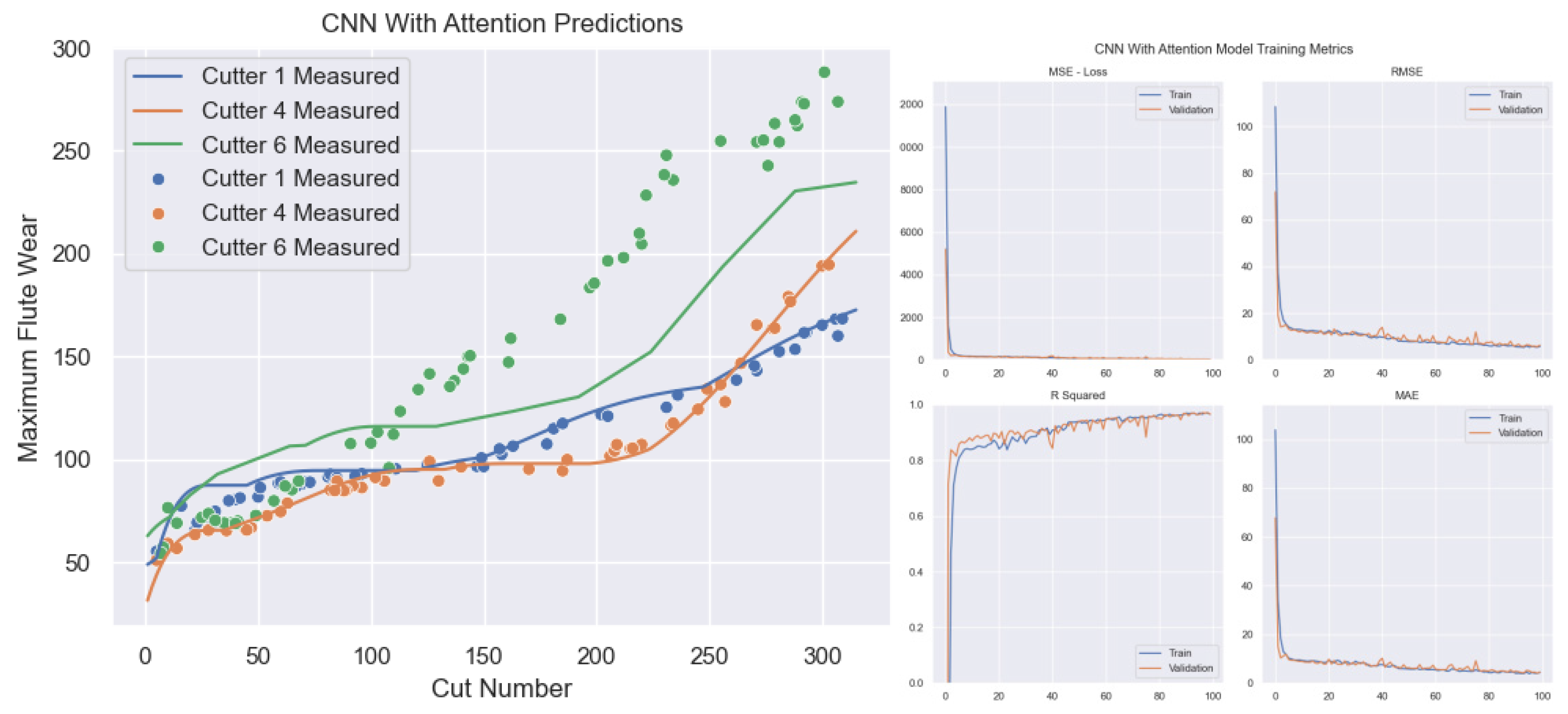

In order to verify that a single network cannot effectively achieve the nonlinear relationship between signal data and wear values, this paper validates the results of three single network models (one-dimensional convolutional neural network model, one-dimensional convolutional neural network attention mechanism model, one-dimensional convolutional neural network Informer model). The one-dimensional convolutional neural network is designed with reference to the Resnet network structure, and the convolution operation is changed to one-dimensional convolution. Other model parameters refer to the convolution module in this article; The parameter settings for the one-dimensional convolutional neural network Attention mechanism model and one-dimensional convolutional neural network Informer model refer to the Informer module parameters used in this article.

The experimental results comparing the predicted and actual tool wear values of the one-dimensional convolutional neural model are shown in Figure 3.21; The experimental results comparing the predicted and actual tool wear values of the one-dimensional convolutional neural network Attention mechanism model are shown in Figure 3.22; The experimental results comparing the predicted and actual tool wear values of the one-dimensional convolutional neural network Informer model are shown in Figure 3.23.

Figure 3.21.

Tool wear prediction of one-dimensional convolutional neural network model.

Figure 3.21.

Tool wear prediction of one-dimensional convolutional neural network model.

Figure 3.22.

One dimensional Convolutional Neural Network Attention Mechanism Model for Predicting Tool Wear.

Figure 3.22.

One dimensional Convolutional Neural Network Attention Mechanism Model for Predicting Tool Wear.

Figure 3.23.

One dimensional Convolutional Neural Network - Informer Model for Predicting Tool Wear.

Figure 3.23.

One dimensional Convolutional Neural Network - Informer Model for Predicting Tool Wear.

Comparing model performance across different wear stages reveals each model’s limitations. Figure 3.21 shows the 1D CNN has significant errors in initial and severe wear stages, indicating difficulty in capturing rapid wear transitions. Figure 3.22 shows the CNN Attention model has small errors on specific sets (C4, C6) but poor cross-validation performance on others (C1), highlighting its limited generalization. Figure 3.23 shows the CNN Informer model’s predictions closely follow the true curve but has jumps and local deviations, making it challenging to perfectly simulate dynamic wear processes.

A single network model struggles to comprehensively extract key features from long-term sensor data. This study proposes a fusion model strategy to leverage different models’ strengths for more comprehensive data interpretation and accurate signal-to-wear mapping. Comparative experiments (Table 3.9) show the proposed model outperforms others in evaluation metrics, effectively learning wear curve patterns.

Table 3.11.

Comparison of experimental results under different methods.

Table 3.11.

Comparison of experimental results under different methods.

| Model name |

C1 |

C4 |

C6 |

| MAE |

R2

|

RMSE |

MAE |

R2

|

RMSE |

MAE |

R2

|

RMSE |

| SVR [38] |

1.56 |

0.871 |

18.5 |

- |

0.882 |

- |

24.9 |

0.892 |

31.5 |

| LSTM [63] |

24.5 |

0.863 |

31.2 |

18 |

0.923 |

20 |

24.8 |

0.845 |

31.4 |

| CNN [64] |

6.57 |

0.928 |

9.46 |

15.75 |

0.918 |

20.63 |

17.68 |

0.899 |

22.34 |

| CNN-LSTM [65] |

8.3 |

0.936 |

12.1 |

- |

0.922 |

- |

15.2 |

0.917 |

18.9 |

| TBNN [38] |

11.18 |

0.897 |

13.77 |

9.39 |

0.954 |

11.85 |

11.34 |

0.936 |

14.33 |

| CTNN [39] |

4.294 |

0.976 |

6.116 |

- |

0.941 |

- |

7.772 |

0.936 |

9.553 |

| IE-SBIGRU [40] |

3.634 |

0.966 |

5.358 |

- |

0.959 |

- |

7.753 |

0.964 |

9.209 |

| Our |

1.693 |

0.995 |

3.628 |

2.132 |

0.992 |

3.627 |

2.173 |

0.997 |

3.159 |