Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Film Age Rating Systems

-

MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) was established in the USA. The MPAA is one of the most well-known film classification system and has been in use since 1968 [8]. The key ratings include:

- -

- G (General Audience): Suitable for all ages.

- -

- PG (Parental Guidance): Some material may not be suitable for children.

- -

- PG-13: Parents are strongly advised that some content may be inappropriate for children under 13 years of age.

- -

- R (Restricted): Viewers under 17 years of age require an accompanying adult.

- -

- NC-17: No one 17 and under admitted.

-

BBFC (British Board of Film Classification) was established in UK [10].The BBFC has been classifying films since 1912, offering ratings that guide the public and protect younger viewers:

- -

- U (Universal): Suitable for all.

- -

- PG (Parental Guidance): General viewing, but some scenes may be unsuitable for young children.

- -

- 12A: Children under 12 years of age must be accompanied by an adult.

- -

- 15: Suitable only for viewers aged 15 and older.

- -

- 18: Suitable only for adults.

-

CNC (Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée) was established in France [11].The French system, managed by the CNC, uses a stricter approach to age ratings, with strong emphasis on protecting minors from harmful content:

- -

- U: Suitable for all.

- -

- 10: Not recommended for children under 10.

- -

- 12: Not recommended for children under 12.

- -

- 16: Not recommended for children under 16.

- -

- 18: Suitable only for adults.

-

FSK (Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle der Filmwirtschaft) was established in Germany [12].The German film classification system is managed by the FSK and offers the following categories:

- -

- 0: Suitable for all.

- -

- 6: Suitable for ages 6 and older.

- -

- 12: Suitable for ages 12 and older.

- -

- 16: Suitable for ages 16 and older.

- -

- 18: Suitable only for adults.

-

ACB (Australian Classification Board) was established in Australia [13] and has been in use since 1968.The Australia’s film rating system offers the following categories:

- -

- G: Suitable for all.

- -

- PG: Parental guidance recommended for viewers under 15.

- -

- M: Recommended for viewers 15 and over.

- -

- MA15+: Restricted to viewers 15 and older unless accompanied by an adult.

- -

- R18+:: Restricted to adult viewers (18+).

- -

- X18+:: Explicit adult content.

2.2. Recommender Systems

- item-to-item correlation, where recommendations are based on item properties, and the association between them;

- user-to-user correlation, where recommendations are obtained based on the demographic information of users;

- user-to-item correlation, where recommendations are obtained based on item preferences of users.

3. Problem Formulation

4. Proposed Methodology

|

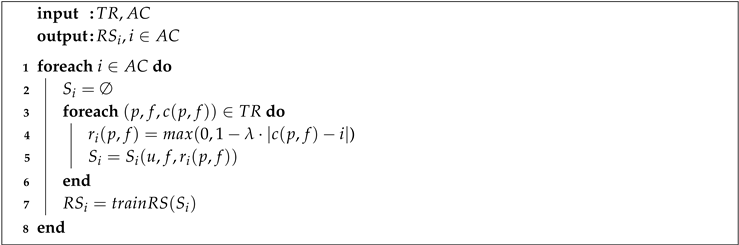

| Algorithm 1: The training phase of the proposed method. |

|

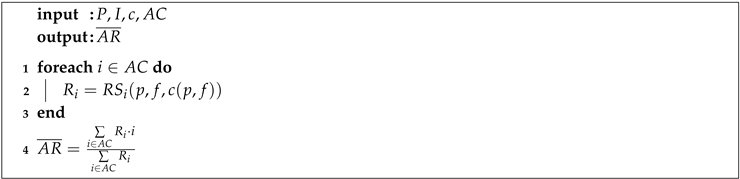

| Algorithm 2: The proposed application method of recommender systems to predict personalized film age ratings of parents. This algorithm shows the testing phase of the proposed method. |

5. Experimental Results

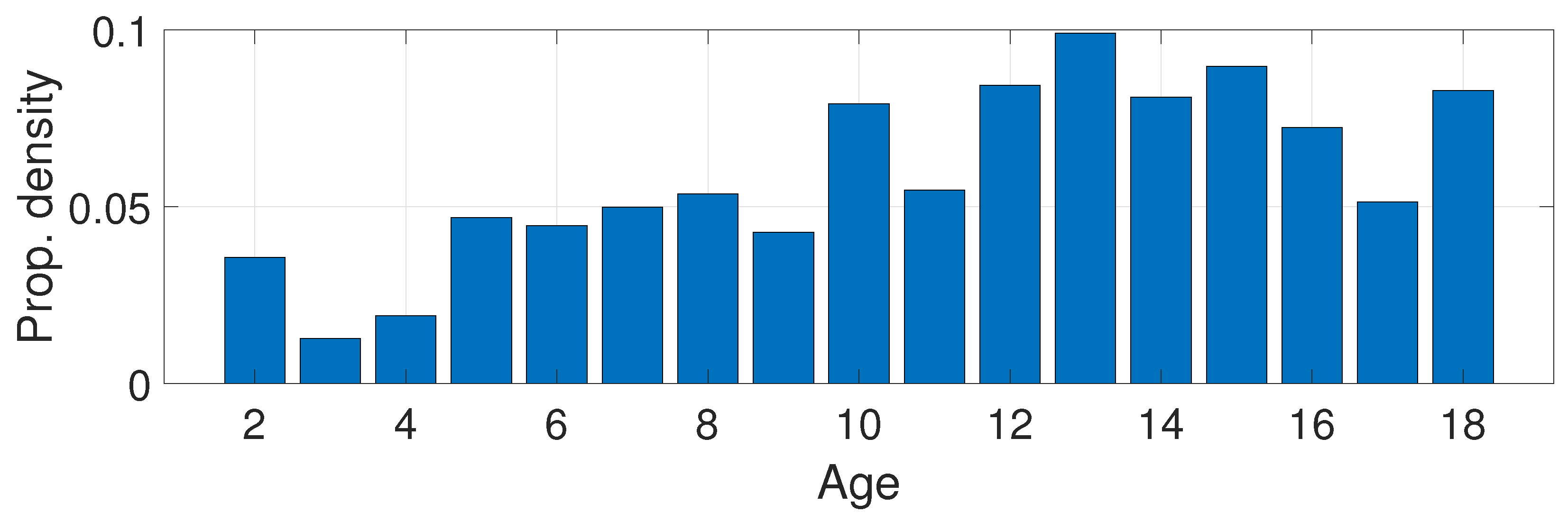

5.1. Dataset

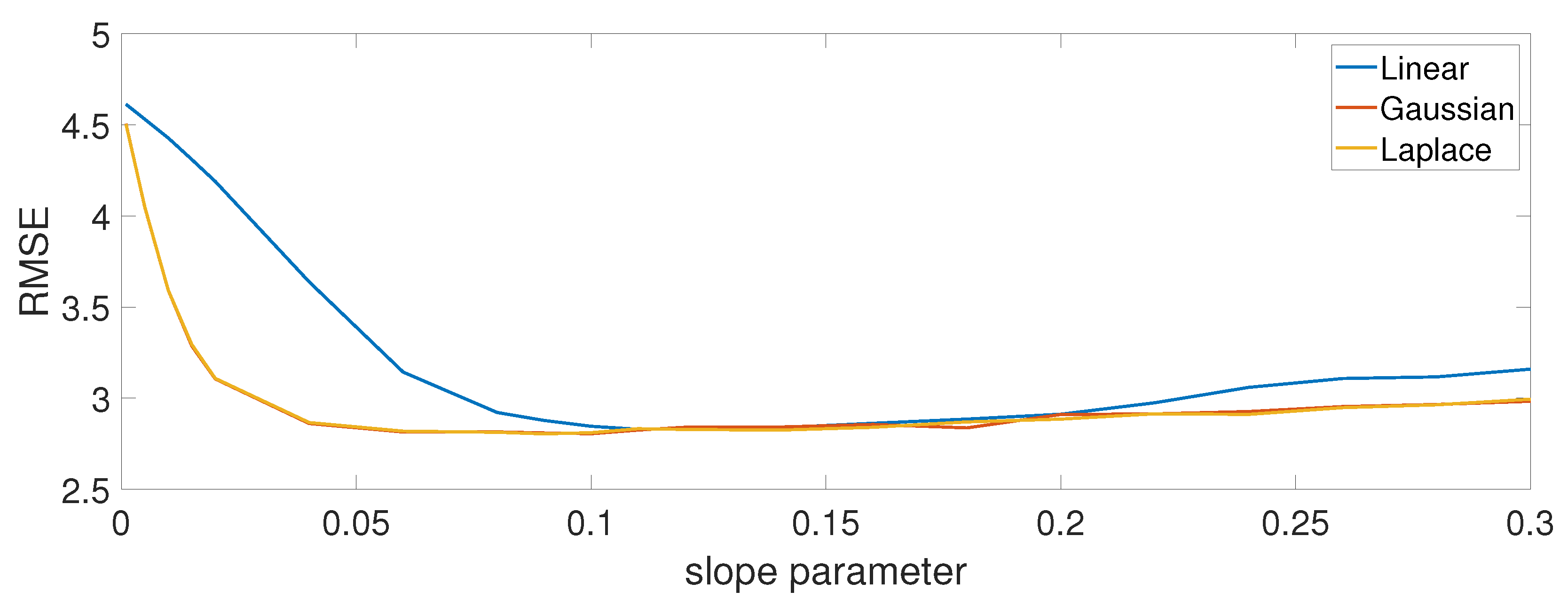

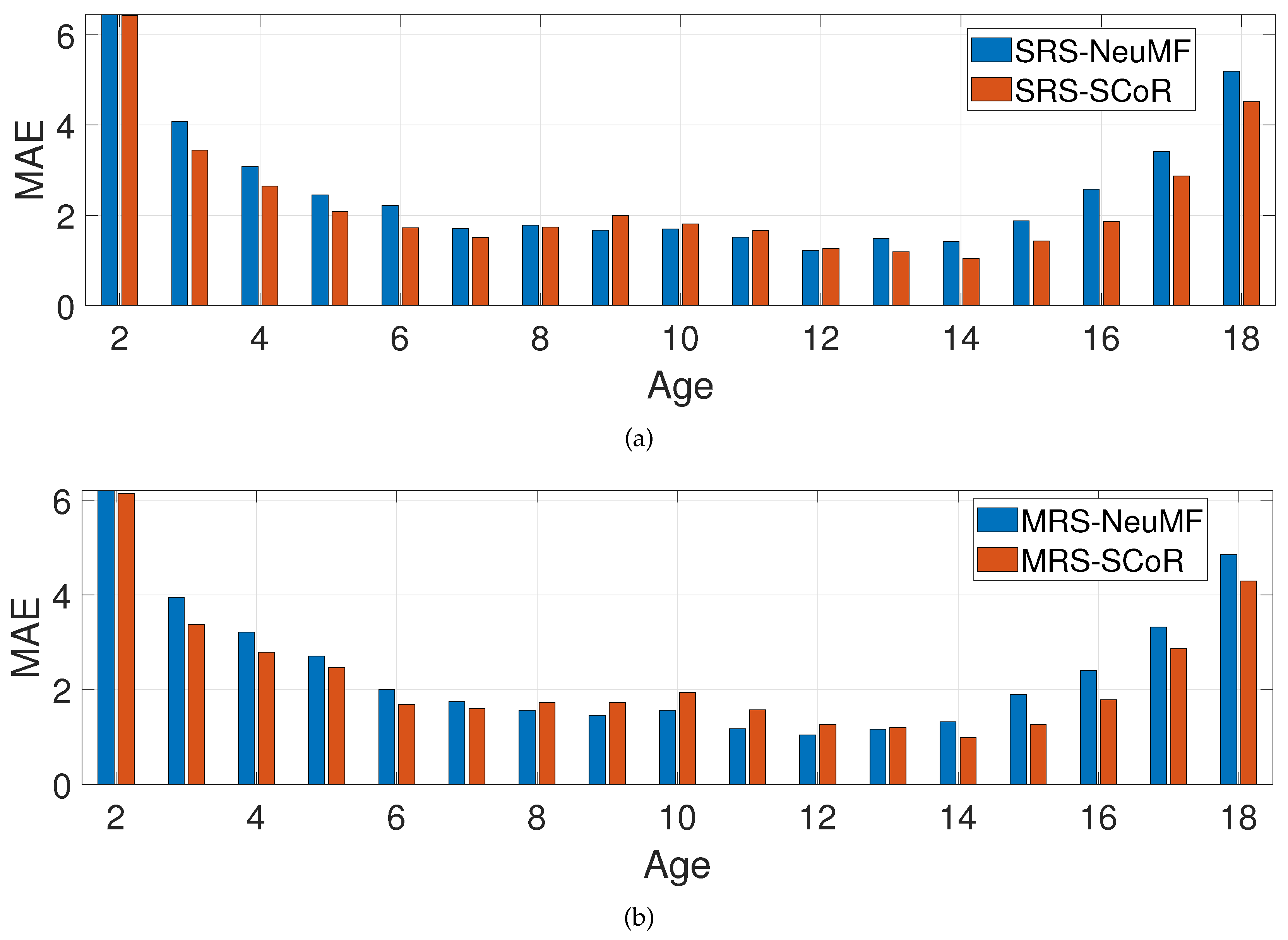

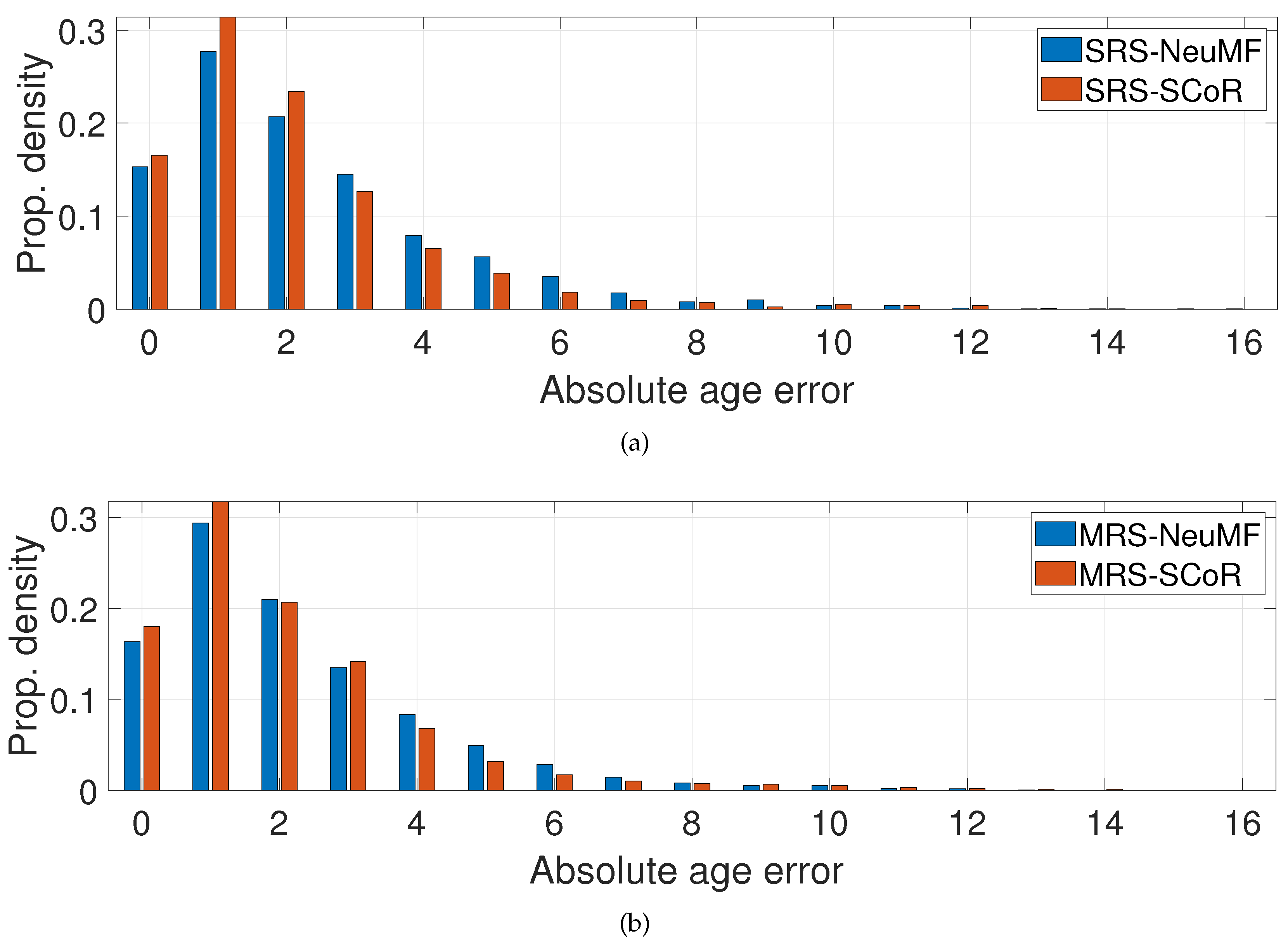

5.2. Performance Evaluation

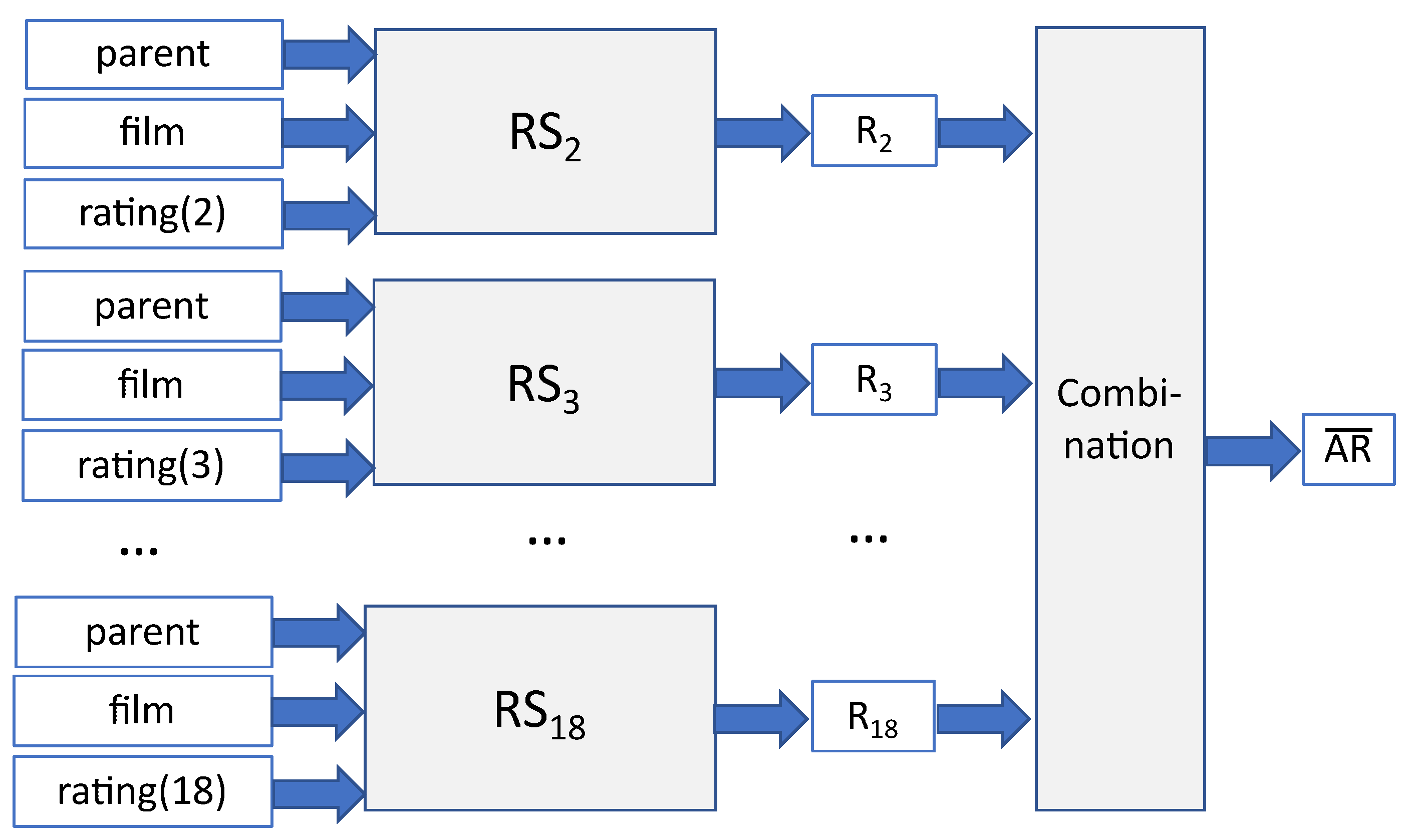

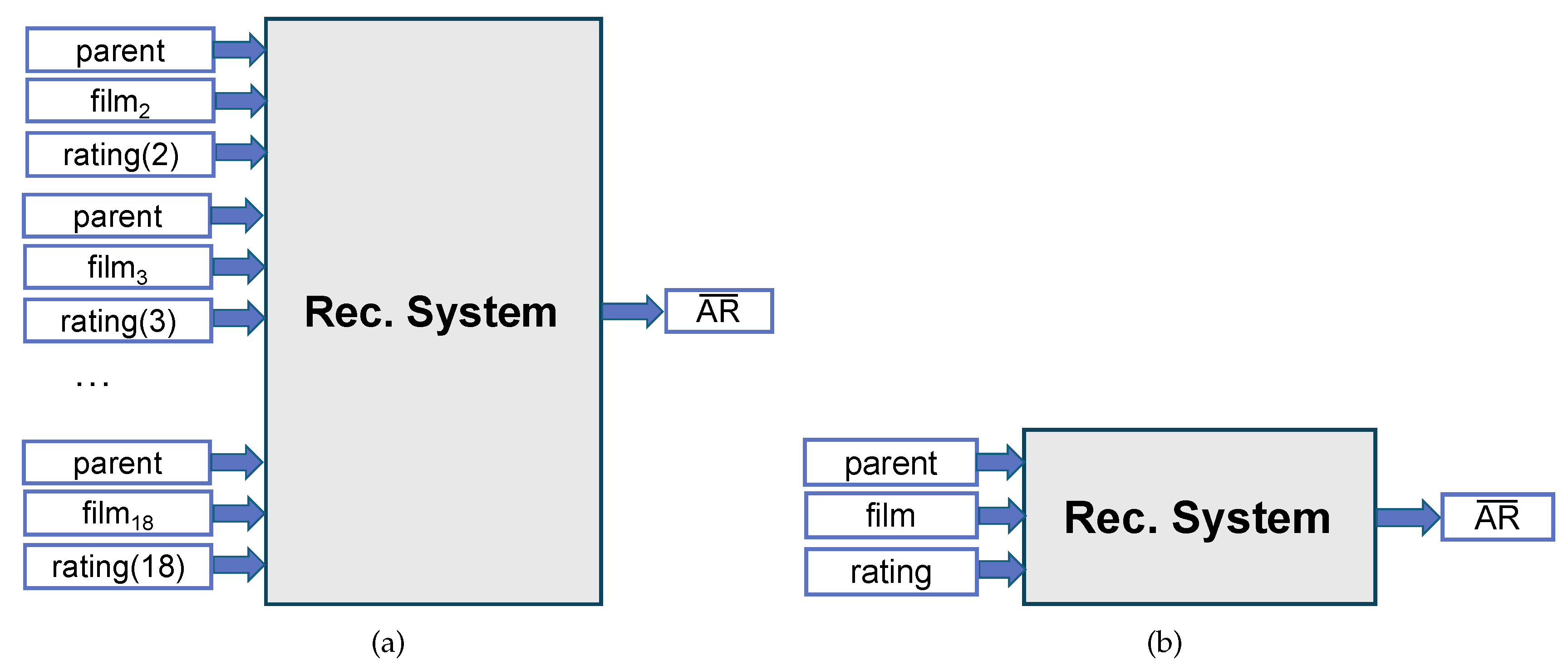

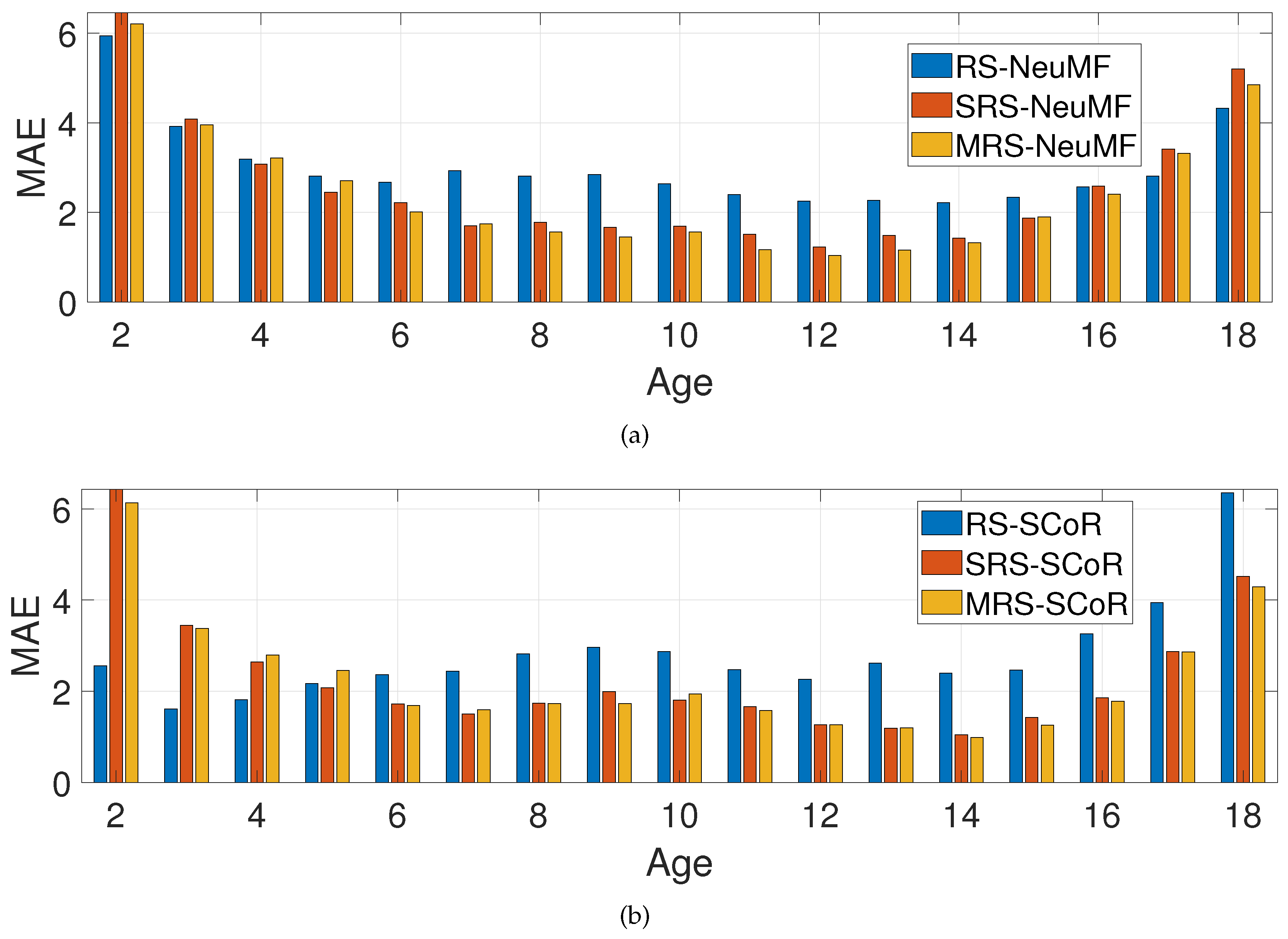

- In the first group (MRS - Multiple Recommender Systems), the approach used is the one described so far in this paper (see Figure 1).

- The second group (SRS - Single Recommender System) is a variation of the first, where only one Recommender System was used, which was trained on the data of all age categories, instead of a separate independent recommender system per age category (see Figure 4a).

- Finally, the "RS" group corresponds to the experiments performed without any dataset transformation, where both recommender systems used (SCoR and NeuMF), were trained on the original age values (see Figure 4b). Those experiments were performed in order to demonstrate the necessity of the data transformation in the first phase.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory (1992). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development 2005, p. 106–173.

- Erikson, E.H. Childhood and Society; W.W. Norton and Company, 1950.

- Kelly, K.; Garbacz, A.; Albers, C. Theories of School Psychology Critical Perspectives; Routledge, 2020; p. 138–151.

- Piotrowski, J.T.; Valkenburg, P.M. Finding Orchids in a Field of Dandelions: Understanding Children’s Differential Susceptibility to Media Effects. American Behavioral Scientist 2015, 59, 1776–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, D.; Bushman, B. Reassessing Media Violence Effects Using a Risk and Resilience Approach to Understanding Aggression; Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2012; p. 138–151.

- Masten, A. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist 2001, 56, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskalaki, E.; Panagiotakis, C.; Papadakis, H.; Fragopoulou, P. Age recommendations for children’s films: associations between advisories on a US site and parents’ ratings. Journal of Children and Media 2022, 16, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motion Picture Association. https://www.motionpictures.org/. Accessed: 26/9/2024.

- Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/. Accessed: 26/9/2024.

- British Board of Film Classification. https://www.bbfc.co.uk/. Accessed: 26/9/2024.

- Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée. https://www.cnc.fr/. Accessed: 26/9/2024.

- Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle der Filmwirtschaft. https://www.fsk.de/. Accessed: 26/9/2024.

- Australian Classification Board. https://www.classification.gov.au/. Accessed: 26/9/2024.

- Bobadilla, J.; Ortega, F.; Hernando, A.; Gutiérrez, A. Recommender systems survey. Knowledge-based systems 2013, 46, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, H.; Panagiotakis, C.; Fragopoulou, P. SCoR: A Synthetic Coordinate based System for Recommendations. Expert Systems with Applications 2017, 79, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Nie, L.; Hu, X.; Chua, T.S. Neural collaborative filtering. Proceedings of the 26th international conference on world wide web, 2017, pp. 173–182.

- Panagiotakis, C.; Papadakis, H.; Papagrigoriou, A.; Fragopoulou, P. Improving recommender systems via a dual training error based correction approach. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 183, 115386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Ouyang, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Rong, W.; Xiong, Z. User occupation aware conditional restricted boltzmann machine based recommendation. Internet of Things (iThings), 2016 IEEE International Conference on. IEEE, 2016, pp. 454–461.

- Guo, G.; Zhang, J.; Thalmann, D. Merging trust in collaborative filtering to alleviate data sparsity and cold start. Knowledge-Based Systems 2014, 57, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wilkinson, D.; Schreiber, R.; Pan, R. Large-Scale Parallel Collaborative Filtering for the Netflix Prize. International conference on algorithmic applications in management. Springer, 2008, pp. 337–348.

- Elahi, M.; Ricci, F.; Rubens, N. A survey of active learning in collaborative filtering recommender systems. Computer Science Review 2016, 20, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, H.; Papagrigoriou, A.; Panagiotakis, C.; Kosmas, E.; Fragopoulou, P. Collaborative filtering recommender systems taxonomy. Knowledge and Information Systems 2022, 64, 35–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, K.; Roeder, T.; Gupta, D.; Perkins, C. Eigentaste: A Constant Time Collaborative Filtering Algorithm. Inf. Retr. 2001, 4, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrell, G. Generalized Hebbian Algorithm for Incremental Singular Value Decomposition in Natural Language Processing. 11st Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2006, pp. 97–104.

- Mobasher, B.; Burke, R.D.; Sandvig, J.J. Model-Based Collaborative Filtering as a Defense against Profil Injection Attacks. The Twenty-First National Conference on Artificial Intelligence and the Eighteenth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference, July 16-20, 2006, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 2006, pp. 1388–1393.

- Koren, Y.; Bell, R.; Volinsky, C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 2009, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabek, F.; Cox, R.; Kaashoek, F.; Morris, R. Vivaldi: A decentralized network coordinate system. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review. ACM, 2004, Vol. 34, pp. 15–26.

- Panagiotakis, C.; Papadakis, H.; Fragopoulou, P. Personalized Video Summarization Based Exclusively on User Preferences. European Conference on Information Retrieval. Springer, 2020, pp. 305–311.

- Panagiotakis, C.; Papadakis, H.; Fragopoulou, P. Detection of hurriedly created abnormal profiles in recommender systems. 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), 2018, pp. 499–506.

- Panagiotakis, C.; Papadakis, H.; Fragopoulou, P. Unsupervised and Supervised Methods for the Detection of Hurriedly Created Profiles in Recommender Systems. Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, H.; Panagiotakis, C.; Fragopoulou, P. Distributed detection of communities in complex networks using synthetic coordinates. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2014, 2014, P03013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakis, C.; Papadakis, H.; Grinias, E.; Komodakis, N.; Fragopoulou, P.; Tziritas, G. Interactive image segmentation based on synthetic graph coordinates. Pattern Recognition 2013, 46, 2940–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Piao, J.; Quan, Y.; Chang, J.; Jin, D.; He, X.; others. A survey of graph neural networks for recommender systems: Challenges, methods, and directions. ACM Transactions on Recommender Systems 2023, 1, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Du, X.; Wang, X.; Tian, F.; Tang, J.; Chua, T.S. Outer Product-based Neural Collaborative Filtering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.03912 2018.

- Berg, R.v.d.; Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Graph convolutional matrix completion. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.02263 2017.

- Papadakis, H.; Papagrigoriou, A.; Kosmas, E.; Panagiotakis, C.; Markaki, S.; Fragopoulou, P. Content-based recommender systems taxonomy. Foundations of Computing and Decision Sciences 2023, 48, 211–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquale Lops, M.d.G.; Semeraro, G. Content-based Recommender Systems: State of the Art and Trends. In Recommender Systems Handbook; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 73–106. [Google Scholar]

- Logesh, R.; Subramaniyaswamy, V. Exploring hybrid recommender systems for personalized travel applications. In Cognitive informatics and soft computing; Springer, 2019; pp. 535–544.

- Adomavicius, G.; Kwon, Y. Improving aggregate recommendation diversity using ranking-based techniques. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2012, 24, 896–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RMSE | RS | SRS | MRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCoR | 3.99 | 2.88 | 2.83 |

| NeuMF | 3.67 | 3.14 | 2.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).