Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

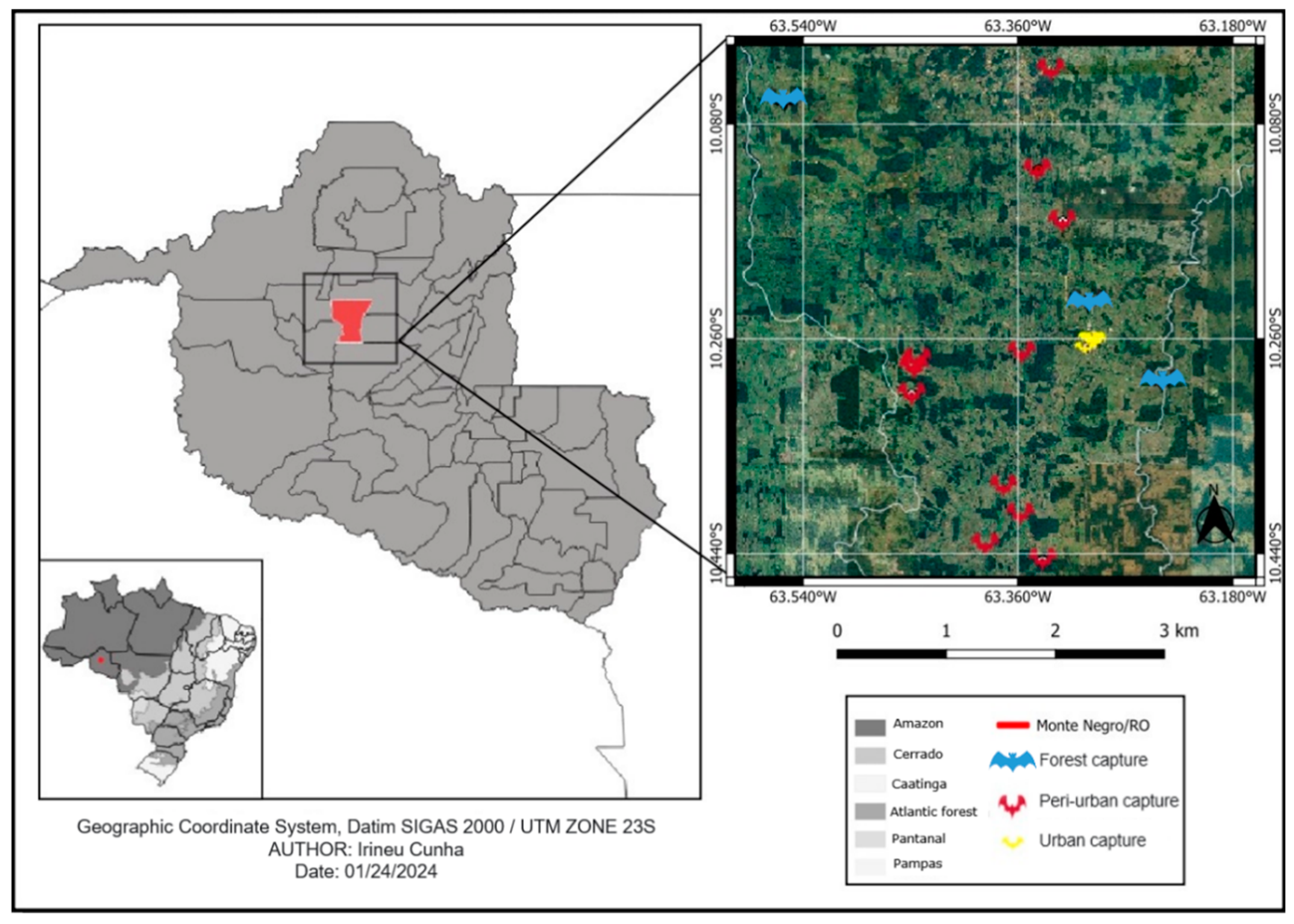

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Bat Capture and Sample Collection

2.3. Ticks, Mites and Flies

2.4. Molecular Detection of Vector-Borne Bacteria

2.5. Ethical Aspects

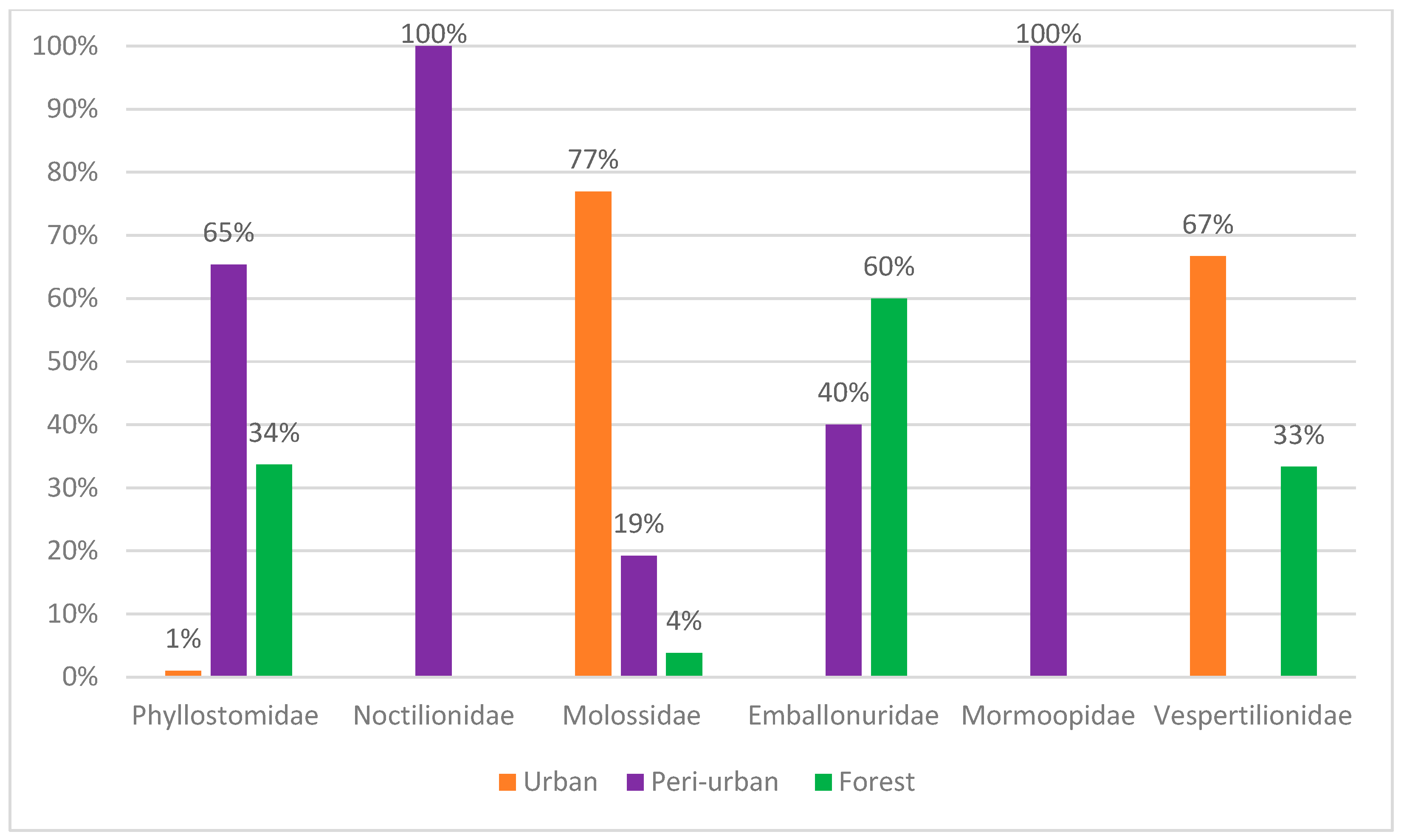

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Ethical Approval

Consent to publication

Competing interests

References

- Burgin CJ, Colella JP, Kahn PL, Upham NS. How many species of mammals are there? Journal of Mammalogy. 2018 Feb 1;99(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Simmons NB. Order chiroptera. Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference / 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press; 2005.

- Fenton MB, Simmons NB. Bats : a world of science and mystery. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2014.

- Tavares VC, Gregorin R, Peracchi AL. Diversidade de Morcegos no Brasil: lista atualizada com comentários sobre distribuição e taxonomia. In: Pacheco, S. M.; Marques, R. V.; Esbérard, C. E. L. (Eds) Morcegos no Brasil: Biologia, Sistemática, Ecologia e Conservação. Armazém Digital, Porto Alegre, 2008. pp. 25–58.

- Bernard E, Tavares V da C, Sampaio E. Compilação atualizada das espécies de morcegos (Chiroptera) para a Amazônia Brasileira. Biota Neotropica [Internet]. 2011 Mar 1 [cited 2023 Jun 27];11:35–46. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/bn/a/LHH9cL5GBnvTb6pZ3LLL6gC/?lang=pt.

- Kelake M, Yanri Rizky Natanael Simangunsong, Susi Soviana, Upik Kesumawati Hadi, Supriyono Supriyono. Diversity of ectoparasites on bats in dramaga, Bogor, Indonesia. Biotropia: The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Biology. 2023 Dec 7;30(3):365–73. [CrossRef]

- Díaz MM, Solari S, Aguirre LF, Aguiar L, Barquez RM. Clave de Identificación de los murciélagos de Sudamérica – Chave de identificação dos morcegos da América do Sul [E-book]. 2. 2nd ed. Tucumãn Argentina: [publisher unknown]; 2016. ISBN: 9789874201102. 160p.

- Reis NR. Morcegos do Brasil. Londrina: Edição Dos Editores; 2007.

- Abreu-JR EF, Casali D, Costa-Araújo R, Garbino GST, Libardi GS, Loretto D, et al. Lista de Mamíferos do Brasil. In: Comitê de Taxonomia da Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia (CT-SBMz). Available online: http://www.sbmz.org/mamiferos-do-brasil (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Luna EJTP, Silva JBA, Pereira G da R, Cunha LP, Souza JLF de. Fauna Phylostomidae da região central do Estado de Rondônia, Brasil. Research, Society and Development. 2022 Jul 1;11(8):e44911830466. [CrossRef]

- Mendez, E. Parasites f Vampire Bats. In: Natural history of vampire bats. CRC Press, 2018.

- Muñoz-Leal S, Barbier E, Soares FAM, Bernard E, Labruna MB, Dantas-Torres F. New records of ticks infesting bats in Brazil, with observations on the first nymphal stage of Ornithodoros hasei. Experimental and Applied Acarology. 2018 Nov 24;76(4):537–49. [CrossRef]

- Almeida JC de. Estudo da preferência dos ácaros (Acari: Spinturnicidae e Macronyssidae) ectoparasitos por regiões anatômicas em morcegos de área de Mata Atlântica, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. tedeufrrjbr [Internet]. 2012 Feb 8 [cited 2024 Mar 6]; Available online: https://tede.ufrrj.br/jspui/handle/jspui/3603.

- Lourenço EC, Pinheiro MC, Faccini JLH, Famadas KM. New record, host and localities of bat mite of genus Chirnyssoides (Acari, Sarcoptiformes, Sarcoptidae). Revista Brasileira De Parasitologia Veterinaria. 2013 Jun 1;22(2):260–4.

- De Castro-Jacinavicius F, Bassini-Silva R, Mendoza-Roldan JA, Pepato AR, Ochoa R, Welbourn C, et al. A checklist of chiggers from Brazil, including new records (Acari: Trombidiformes: Trombiculidae and Leeuwenhoekiidae). ZooKeys. 2018 Mar 14;743:1–41. [CrossRef]

- Minaya D, Mendoza J, Iannacone J. Fauna de ectoparásitos en el vampiro común Desmodus rotundus (Geoffroy, 1810) (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) de Huarochiri, Lima, y una lista de los ectoparásitos en murciélagos del Perú. Graellsia. 2021 May 26;77(1):e135.

- Cepeda-Duque JC, Ruiz-Correa LF, Cardona-Giraldo A, Ossa-López PA, Rivera-Páez FA, Ramírez-Chaves HE. Hectopsylla pulex (Haller, 1880) (Siphonaptera: Tungidae) infestation on Eptesicus furinalis (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in the Central Andes of Colombia. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia. 2021 Mar 31;61:e20216138. [CrossRef]

- Graciolli G, Bernard E. Novos registros de moscas ectoparasitas (Diptera, Streblidae e Nycteribiidae) em morcegos (Mammalia, Chiroptera) do Amazonas e Pará, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia. 2002 Jul 1;19(suppl 1):77–86. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero R. Streblidae (Diptera: Pupipara) de Venezuela: Sistemática, Ecología y Evolución. Editorial Académica Española, 2019.

- De Castro-Jacinavicius F, Bassini-Silva R, Mendoza-Roldan JA, Pepato AR, Ochoa R, Welbourn C, et al. A checklist of chiggers from Brazil, including new records (Acari: Trombidiformes: Trombiculidae and Leeuwenhoekiidae). ZooKeys. 2018 Mar 14;743:1–41. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Leal S, Barbier E, Soares FAM, Bernard E, Labruna MB, Dantas-Torres F. New records of ticks infesting bats in Brazil, with observations on the first nymphal stage of Ornithodoros hasei. Experimental and Applied Acarology. 2018 Nov 24;76(4):537–49. [CrossRef]

- Bassini-Silva R, Jacinavicius FC, Welbourn C, Barros-Battesti DM, Ochoa R. Complete Type Catalog of Trombiculidae sensu lato (Acari: Trombidiformes) of the U.S. National Entomology Collection, Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 2021 Jan 8;(652):2–141. [CrossRef]

- Graciolli G, Linardi PM. Some Streblidae and Nycteribiidae (Diptera: Hippoboscoidea) from Maracá Island, Roraima, Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2002 Jan;97(1):139–41.

- Falcão LAD. Morcegos em florestas tropicais secas brasileiras. repositorioufmgbr [Internet]. 2015 Dec 18 [cited 2024 Mar 6]; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1843/BUBD-A9MGTR.

- Matei IA, Corduneanu A, Sándor AD, IonicăAM, Panait L, Kalmár Z, et al. Rickettsia spp. in bats of Romania: high prevalence of Rickettsia monacensis in two insectivorous bat species. Parasites & Vectors. 2021 Feb 10;14(1). [CrossRef]

- Silva-Ramos CR, Faccini-Martínez ÁA, Pérez-Torres J, Hidalgo M, Cuervo C. First molecular evidence of Coxiella burnetii in bats from Colombia. Research in Veterinary Science. 2022 Dec;150:33–5. [CrossRef]

- Jorge FR, Sebastián Muñoz-Leal, Glauber, Carolina M, Meylling M L Magalhães, Lorena, et al. Novel Borrelia Genotypes from Brazil Indicate a New Group of Borrelia spp. Associated with South American Bats. Journal of Medical Entomology [Internet]. 2022 Oct 21 [cited 2024 Sep 7];60(1):213–7. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jme/article/60/1/213/6767844.

- De Salvo MN, Palmerio A, La Rosa I, Rodriguez A, Beltrán FJ, Gury Dohmen FE, Cicuttin GL. Bartonella spp. in different species of bats from Misiones (Argentina). Rev Argent Microbiol. 2024 Jun 12:S0325-7541(24)00045-2. [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos FCB, Lisboa CV, Xavier SCC, Dario MA, Verde R de S, Calouro AM, et al. Trypanosoma sp. diversity in Amazonian bats (Chiroptera; Mammalia) from Acre State, Brazil. Parasitology. 2017 Nov 16;145(6):828–37.

- Weber MN, Soares M. Corona- and Paramyxoviruses in bats from Brazil: a matter of concern? Animals [Internet]. 2023 Dec 26;14(1):88. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/14/1/88.

- Ludwig L, Muraoka JY, Bonacorsi C, Donofrio FC. Diversity of fungi obtained from bats captured in urban forest fragments in Sinop, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology. 2023;83. [CrossRef]

- Hayman DTS. Bats as Viral Reservoirs. Annual Review of Virology. 2016 Sep 29;3(1):77–99.

- Subudhi S, Rapin N, Misra V. Immune System Modulation and Viral Persistence in Bats: Understanding Viral Spillover. Viruses [Internet]. 2019 Feb 23;11(2). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6410205/.

- Aguiar DM de, Cavalcante GT, Lara M do CC de SH, Villalobos EMC, Cunha EMS, Okuda LH, Stéfano E, et al. Prevalência de anticorpos contra agentes virais e bacterianos em eqüídeos do Município de Monte Negro, Rondônia, Amazônia Ocidental Brasileira [Internet]. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science. 2008 ; 45( 4): 269-276.[citado 2024 mar. 06] Available online: http://www.revistas.usp.br/bjvras/article/view/26685/28468.

- Gardner AL. Mammals of South America, volume 1: marsupials, xenarthrans, shrews, and bats. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Reis NR, Peracchi AL, Batista CB, de Lima IP, Pereira AD. História Natural dos morcegos brasileiros: chave de identificação de espécies. 2017.

- Straube FC, Bianconi GV. Sobre a grandeza e a unidade utilizada para estimar esforço de captura com utilização de redes-de-neblina. Chiroptera Neotropical. 2002.

- Jones EK, Clifford CM. The Systematics of the Subfamily Ornithodorinae (Acarina: Argasidae). V. a Revised Key to Larval Argasidae of the Western Hemisphere and Description of Seven New Species of Ornithodoros. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1972 May 15;65(3):730–40. [CrossRef]

- Labruna MB, Nava S, Terassini FA, Onofrio VC, Barros-Battesti DM, Camargo LM et al. Description of adults and nymph, and redescription of the larva, of Ornithodoros marinkellei (Acari:Argasidae), with data on its phylogenetic position. J. Parasitol. 2011 Apr;97(2):207-17. [CrossRef]

- Sangioni LA, Horta MC, Barreto C, Gennari SM, Soares RM, Galvão MAM, et al. Rickettsial Infection in Animals and Brazilian Spotted Fever Endemicity. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005 Feb 1;11(2):265–70. [CrossRef]

- Mangold AJ, Bargues MD, Mas-Coma S. Mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences and phylogenetic relationships of species of Rhipicephalus and other tick genera among Metastriata (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasitology Research. 1998 Apr 6;84(6):478–84. [CrossRef]

- Rudnick A. A revision of the mites of the family of Spinturnicidae (Acarina). (No Title) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 6]; Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130000798318231424.

- Machado-Allison CE. Las especies Venezolanas del género Periglischrus Kolenati, 1857 (Acarina, Mesostigmata, Spinturnicidae). 1965a.

- Machado-Allison CE. Notas sobre Mesostigmata Neotropicales.III. Cameronieta thomasi; nuevo género y nueva especie parasita de Chiroptera (Acarina, Spinturnicidae). 1965b.

- Herrin CS, Tipton VJ. Spinturnicid mites of Venezuela (Acarina: Spinturnicidae) [Internet]. BYU ScholarsArchive. 2016. Available online: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byuscib/vol20/iss2/1/.

- Carvalho CJB de, Rafael JA, Couri MS, Riccardi PR, Silva VC, Oliveira SS de, et al. Capítulo 36: Diptera Linnaeus, 1758 [Internet]. repositorio.inpa.gov.br. Editora INPA; 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 6]. Available online: https://repositorio.inpa.gov.br/handle/1/40264.

- Guerrero R. Streblidae (Diptera: Pupipara) de Venezuela: Sistemática, Ecología y Evolución. Editorial Académica Española, 2019.

- Labruna MB, Whitworth T, Bouyer DH, McBride J, Camargo LMA, Camargo EP, et al. Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma Ticks from the State of Rondônia, Western Amazon, Brazil. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2004 Nov 1;41(6):1073–81.

- Soares JF, Soares HS, Barbieri AM, Labruna MB. Experimental infection of the tick Amblyomma cajennense, Cayenne tick, with Rickettsia rickettsii, the agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2011 Oct 19;26(2):139–51.

- Parola P, Diatta G, Socolovschi C, Mediannikov O, Tall A, Bassene H, et al. Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever Borreliosis, Rural Senegal. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011 May;17(5):883–5. [CrossRef]

- Willems H, Thiele D, Frölich-Ritter R, Krauss H. Detection of Coxiella burnetii in Cow’s Milk using the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Series B. 1994 Jan 12;41(1-10):580–7. [CrossRef]

- Otto JC, Wilson KJ. Assessment of the usefulness of ribosomal 18S and mitochondrial COI sequences in Prostigmata phylogeny. In: Proctor, H.C., Norton, R.A., Colloff, M.J. 2001.

- Colborn JM, et al. Improved detection of Bartonella DNA in mammalian hosts and arthropod vectors by real-time PCR using the NADH dehydrogenase gamma subunit (nuoG). Journal of clinical microbiology, v. 48, n. 12, p. 4630-4633, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Altschul SF, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology, v. 215, n. 3, p. 403-410, 1990.

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic acids research, v. 22, n. 22, p. 4673-4680, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012 Apr 27;28(12):1647–9. [CrossRef]

- Luz HR, Muñoz-Leal S, Carvalho WD, Castro IJ, Xavier BS, Toledo JJ, et al. Detection of “Candidatus Rickettsia wissemanii” in ticks parasitizing bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in the northern Brazilian Amazon. 2019 Aug 31;118(11):3185–9. [CrossRef]

- Tahir D, Socolovschi C, Marié JL, Ganay G, Berenger JM, Bompar JM, et al. New Rickettsia species in argasid ticks Ornithodoros hasei collected from bats in French Guiana. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 2016 Oct;7(6):1089–96.

- Colombo VC, Montani ME, Romina Pavé, Antoniazzi LR, Gamboa MD, Fasano AA, et al. First detection of “Candidatus Rickettsia wissemanii” in Ornithodoros hasei (Schulze, 1935) (Acari: Argasidae) from Argentina. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 2020 Jul 1;11(4):101442–2.

- Luz HR, Muñoz-Leal S, Almeida JC, Faccini JLH, Labruna MB. Ticks parasitizing bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in the Caatinga Biome, Brazil. Revista Brasileira De Parasitologia Veterinaria. 2016 Dec 8;25(4):484–91. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Leal S, Eriksson A, Santos CF, Fischer E, Almeida JC, Luz HR, Labruna MB. Ticks infesting bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in the Brazilian Pantanal. Experimental and Applied Acarology. 2016 Feb 24;69(1):73–85. [CrossRef]

- Labruna MB, Nava S, Terassini FA, Onofrio VC, Barros-Battesti DM, Camargo LMA, et al. Description of Adults and Nymph, and Redescription of the Larva, of Ornithodoros marinkellei (Acari: Argasidae), with Data on Its Phylogenetic Position. Journal of Parasitology. 2011 Apr 1;97(2):207–17. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Leal S, Faccini-Martínez ÁA, Teixeira BM, Martins MM, Serpa MCA, Oliveira GMB, Jorge FR, Pacheco RC, Costa FB, Luz HR, Labruna MB. Relapsing Fever Group Borreliae in Human-Biting Argasid ticks, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Jan;27(1):322-324. [CrossRef]

- Martins TF, Venzal JM, Terassini FA, Costa FB, Marcili A, Camargo LM, Barros-Battesti DM, Labruna MB. New tick records from the state of Rondônia, western Amazon, Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol. 2014 Jan;62(1):121-8. [CrossRef]

- Damasceno IAM, Guerra RC. Revisão review 4231. Coxiella burnetii e a febre Q no Brasil, uma questão de saúde pública Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v23n12/1413-8123-csc-23-12-4231.pdf.

- Oliveira JMB, Rozental T, de Lemos ERS, Forneas D, Ortega-Mora LM, Porto WJN, et al. Coxiella burnetii in dairy goats with a history of reproductive disorders in Brazil. Acta Tropica [Internet]. 2018 Jul 1 [cited 2022 Dec 9];183:19–22. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29621535/.

- Pacheco RC, Echaide IE, Alves RN, Beletti ME, Nava S, Labruna MB. Coxiella burnetii in ticks, Argentina. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013 Feb;19(2):344-6. [CrossRef]

- Gomes LGO, Gomes GO, Fodra JD. Massabni AC. Zoonoses: as doenças transmitidas por animais | Revista Brasileira Multidisciplinar. revistarebramcom [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1; Available online: https://revistarebram.com/index.php/revistauniara/article/view/1261.

- Ferreira MS. Estudo de Rickettsias lato sensu em amostras de quirópteros de diferentes regiões do Brasil. wwwarcafiocruzbr [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2024 Mar 6]; Available online: https://www.arca.fiocruz.br/handle/icict/16713.

- Braga MSCO, Gonçalves LR, Silva TMVD, Costa FB, Pereira JG, Santos LSD, et al. Occurrence of Bartonella genotypes in bats and associated Streblidae flies from Maranhão state, northeastern Brazil. Revista Brasileira De Parasitologia Veterinaria. 2020 Jan 1;29(4).

- Morse SF, Daszak P, Kosoy M, Billeter SA, Patterson BW, Dick CW, et al. Global distribution and genetic diversity of Bartonella in bat flies (Hippoboscoidea, Streblidae, Nycteribiidae). 2012. [CrossRef]

- Amaral RB. Universidade Estadual Paulista - UNESP campus de Jaboticabal. Detecção e caracterização molecular de Bartonella spp. em moscas Streblidae e ácaros Macronyssidae e Spinturnicidae parasitas de quirópteros [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Mar 6]. Available online: https://repositorio.unesp.br/server/api/core/bitstreams/f24913fd-3635-4051-93f3-6a7ba3036ec9/content.

- Oliveira SV, Bitencourth K, Borsoi ABP, de Freitas FSS, Castelo Branco Coelho G, Amorim M, Gazeta GS. Human parasitism and toxicosis by Ornithodoros rietcorreai (Acari: Argasidae) in an urban area of Northeastern Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018 Sep;9(6):1494-1498. [CrossRef]

- Labruna MB, Marcili A, Ogrzewalska M, Barros-Battesti DM, Dantas-Torres F, Fernandes AA, Leite RC, Venzal JM. New records and human parasitism by Ornithodoros mimon (Acari: Argasidae) in Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2014 Jan;51(1):283-7. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira BCF, Campos AK, Muñoz-Leal S, Pinter A, Martins TF. Soft and hard ticks (Parasitiformes: Ixodida) on humans: A review of Brazilian biomes and the impact of environmental change. Acta Trop. 2022 Oct;234:106598. [CrossRef]

- Simmons NB. The Mammals of Paracou, French Guiana. 1998.

- Bergallo HG, Esbérard CE, Mello MAR, Lins V, Mangolin R, Melo GG, Baptista M, et al. Bat Species Richness in Atlantic Forest: What Is the Minimum Sampling Effort? Biotropica. 2003 Jun 1;35(2):278–88.

- Dixon M, Rodriguez R, Ammerman Source L, Hoyt C, Karges J. Chihuahuan Desert resear Ch institute Comparison of Two Survey Methods Used for Bats Along the Lower Canyons of the Rio Grande and in Big Bend National Park. [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2024 Mar 6] p. 241–249. Available online: http://www.cdri.org/publications/proceedings-of-the-symposium-on-the-natural-resources-of-the-chihuahuan-desert-region/#sympterms.

- Flaquer C, Torre I, Arrizabalaga A. Comparison of Sampling Methods for Inventory of Bat Communities. Journal of Mammalogy [Internet]. 2007 Apr 20;88(2):526–33. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/88/2/526/840471.

- Dornelas Júnior LF, Cunha IN, Camargo LMA. Levantamento bibliográfico: atualização sobre a biodiversidade de morcegos (mammalia; chiroptera) na região central de Rondônia. Revista Científica da Faculdade de Educação e Meio Ambiente [Internet]. 2022 Nov 26 [cited 2024 Mar 6];13(edespccs). Available online: https://revista.unifaema.edu.br/index.php/Revista-FAEMA/article/view/1162/1074.

- Lourenço EC, Famadas KM, Costa A, Bergallo HG. Ticks (Ixodida) associated with bats (Chiroptera): an updated list with new records for Brazil. Parasitology Research. 2023 Aug 19;122(10):2335–52.

- Eriksson A, Filion A, Labruna MB, Muñoz-Leal S, Poulin R, Fischer E, Graciolli G. Effects of forest loss and fragmentation on bat-ectoparasite interactions. Parasitol Res. 2023;122(6):1391-1402. [CrossRef]

- Burazerović J, Orlova M, Obradović M, Ćirović D, Tomanović S. Patterns of abundance and host specificity of bat ectoparasites in the Central Balkans. J Med Entomol. 2018;55(1):20-8. [CrossRef]

| BATS | Number | ECTOPARASITES | Number | Detected bacteria | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | M | F | L | ||||

| Emballonuridae | ||||||||

| Emballonurinae | ||||||||

| Peropteryx kappleri (Peters, 1867) | 3 | 3 | Hooperella sp. | - | - | 56 | - | |

| Rhynchonycteris naso (Wied-Neuwied, 1820) | 7 | 12 | Basilia sp. | 1 | 2 | - | - | |

| Spinturnix sp. | 7 | - | - | - | ||||

| Saccopteryx bilineata (Temminck, 1838) | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Molossidae | ||||||||

| Molossinae | ||||||||

| Molossus Molossus (Pallas, 1766) | 7 | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Eumops perotis (Schinz, 1821) | 2 | 5 | Steatonyssus sp. | - | - | 25 | - | |

| Mormoopidae | ||||||||

| Pteronotus rubiginosus (Wagner, 1843) | 8 | 1 | Trichobius sp. | 9 | 9 | - | - | |

| Paradyschira sp. | - | 1 | - | - | ||||

| Ornithodoros marinkellei | - | - | 6 | - | ||||

| Ornithodoros hasei* | - | - | 10 | - | ||||

| Cameronieta almaensis | 23 | 2 | - | - | ||||

| Noctilionidae | ||||||||

| Noctilio leporinus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 19 | 34 | Ornithodoros hasei* | - | - | 308 | (GenBank No. MH614266) Candidatus Rickettsia wissemanii* | |

| Phyllostomidae | ||||||||

| Carollinae | ||||||||

| Carollia brevicauda (Schinz, 1821) | 13 | 21 | Trichobius joblingi | 11 | 12 | - | (GenBank No. PP445025) Bartonella spp. | |

| Strebla guajiro | 6 | 8 | - | |||||

| Macronyssus sp. | 6 | - | - | - | ||||

| Carollia perspicillata (Linnaeus, 1758) | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Desmodontinae | ||||||||

| Desmodus rotundus (Geoffroy, 1810) | 2 | - | Trombiculidae | - | - | 8 | - | |

| Diphylla ecaudata (Spix, 1823) | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Glossophaginae | ||||||||

| Glossophaga soricina (Pallas, 1766) | 2 | - | Trichobius dugesii | - | 3 | - | - | |

| Periglischrus caligus | 1 | - | - | |||||

| Phyllostominae | ||||||||

| Lophostoma silvícola (d’Orbigny, 1836) | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Phylloderma stenops (Peters, 1865) | 1 | - | Periglischrus torrealbai | 17 | 4 | - | - | |

| Phyllostomus hastatus (Pallas, 1767) | 2 | - | Periglischrus acutisternus | 19 | 4 | - | - | |

| Phyllostomus latifolius (Thomas, 1901) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Trachops cirrhosus (Spix, 1823) | - | 1 | Strebla mirabilis | 4 | 1 | - | (GenBank No. PP445026) Bartonella sp. | |

| Stenodermatinae | - | |||||||

| Artibeus obscurus (Schinz, 1821) | 12 | 33 | Periglischrus iheringi | 13 | 11 | - | - | |

| Vampyrodes caraccioli (Thomas, 1889) | 1 | - | P. iheringi | 2 | 1 | - | - | |

| Sturnira lilium (Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1810) | 1 | - | Periglischrus sp. | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Vespertilionidae | ||||||||

| Myotinae | ||||||||

| Myotis riparius (Handley, 1960) | 1 | - | Macronyssus sp. | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Vespertilioninae | - | |||||||

| Lasiurus villosissimus (Geoffroy St.-Hilaire, 1806) | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Lasiurus sp. (Gray, 1831) | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| TOTAL | 86 | 131 | 121 | 58 | 413 | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).