1. Introduction

With big data, personalized recommendation systems are essential for optimizing user experiences and improving business outcomes, particularly in e-commerce and finance. These systems rely on analyzing vast amounts of data to predict user preferences and behaviors, ultimately providing tailored recommendations that meet individual needs. However, as data grows in volume and complexity, traditional recommendation models face significant challenges in effectively modeling user behavior, especially in environments where transaction data is both high-dimensional and temporally dynamic.

Collaborative filtering and matrix factorization have long been the backbone of recommendation systems, offering a solid foundation for predicting user preferences based on historical interactions. However, collaborative filtering often struggles with data sparsity and lacks scalability, making it less effective when applied to large, sparse datasets typical of financial transactions. While matrix factorization reduces dimensionality, it struggles to capture complex, non-linear relationships between users and items, especially as interactions change over time.

To address these limitations, this research proposes a hybrid model combining LightGBM, DeepFM, and DIN to predict user purchasing behavior using the Elo payment dataset. LightGBM, a highly efficient gradient boosting framework, is well-suited for handling large-scale datasets and complex feature interactions due to its tree-based structure. Its ability to process large volumes of data quickly and accurately makes it a powerful tool for baseline predictions. However, LightGBM’s tree-based approach is inherently limited in capturing intricate higher-order interactions, which are essential for understanding nuanced user behaviors and improving recommendation accuracy.

To bridge this gap, we integrate DeepFM, which combines factorization machines (FM) with deep neural networks (DNN). This approach enables DeepFM to capture both low-order linear interactions through FM and complex non-linear relationships via DNN. This dual capability enables DeepFM to better understand and predict user preferences, making it particularly effective for tasks involving personalized recommendations.

Moreover, to enhance the model’s ability to handle sequential data, we integrate the Deep Interest Network (DIN). DIN introduces an attention mechanism that selectively activates relevant user behaviors based on the specific context of each prediction. By focusing on the most pertinent aspects of a user’s historical actions, DIN significantly enhances the model’s predictive power, especially in scenarios where understanding the sequence and context of user actions is crucial. However, the sensitivity of DIN to noisy or sparse data necessitates careful model training to avoid overfitting and ensure robust predictions.

The significance of this research lies in its ability to integrate these advanced techniques into a cohesive hybrid model that addresses the inherent limitations of traditional recommendation systems. By combining LightGBM, DeepFM, and DIN, and employing sophisticated training methods, we achieve a model that not only improves prediction accuracy but also offers scalability and adaptability for real-world applications. This approach signifies a significant step forward in personalized recommendation systems, especially in the context of payment data, where precision and reliability are essential.

2. Related Work

The development of personalized recommendation systems has advanced significantly, driven by both traditional machine learning and deep learning techniques.Early methods like collaborative filtering and matrix factorization provided a foundation but faced challenges with scalability and data sparsity. He et al. [

1] addressed these issues by introducing Neural Collaborative Filtering (NCF), which utilized neural networks to capture non-linear user-item interactions, though it required extensive hyperparameter tuning.

Deep learning models, including Wide Deep [

2] and DeepFM [

3] , marked a major shift in the field. Wide Deep combines linear and deep neural models to balance memorization and generalization, while DeepFM integrates factorization machines with deep learning to automate feature interaction modeling. Despite their success, these models increase computational complexity and training time.

Attention mechanisms have further enhanced recommendation systems. The Deep Interest Evolution Network (DIEN) by Li et al. [

4] builds on this by modeling interest evolution over time, addressing some of DIN’s limitations.

He et al. [

5] provide optimization techniques that we use to enhance clustering and temporal feature extraction, improving our model’s preprocessing efficiency and prediction accuracy.

Yu et al. [

6] discuss fine-tuning strategies for domain-specific models, which inform our use of pseudo-labeling to improve the model’s learning from unlabeled data, boosting AUC and NDCG metrics.

Integrating external knowledge has also proven effective. Wang et al. [

7] developed the Deep Knowledge-Aware Network (DKN), merging knowledge graphs with deep learning to improve the precision of news recommendation systems. However, this approach introduces additional complexity.

Gradient boosting machines like LightGBM [

8] are popular for their efficiency in handling large datasets, though they struggle with higher-order interactions.

Robust training strategies, including adversarial training [

9] and adversarial weight perturbation [

10], have been critical in enhancing model generalization. Additionally, pseudo-labeling, as discussed by

Tang et al. [

11] highlight the growing impact of deep learning on recommendation systems, noting the need for ongoing research to tackle scalability and interpretability challenges. Further work by Zhang et al. [

12] and He et al. [

13] demonstrate the effectiveness of deep learning and matrix factorization in improving recommendation accuracy.

Finally, large-scale applications of deep learning in recommendation systems have proven highly effective. Covington et al. [

14] showcased the power of deep neural networks for personalized video recommendations on YouTube, managing vast amounts of user data to generate precise and scalable recommendations. This work exemplifies the success of deep learning in handling real-world recommendation tasks, paving the way for future innovations in the field.

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in developing models that are not only accurate but also interpretable and efficient. As personalized recommendation systems continue to evolve, integrating more sophisticated models with robust training strategies will be crucial. This involves exploring hybrid models and developing methods to ensure transparency and fairness in recommendations. The ongoing research in this domain underscores the importance of balancing innovation with practical considerations to build systems that can meet the diverse needs of users in increasingly complex environments.

3. Data Preprocessing

We will create a personalized recommendation system in this section, utilizing the dataset from Elo, one of Brazil’s major payment brands, and its associated merchants. In the recommendation system, the features determine the upper limit of the effect. Data preprocessing is essential to address missing values and enhance data richness.

3.1. Feature Clustering

We clustered user behaviors and imputed missing values with the cluster’s mean or median. Historical and new data were sorted by timestamps to create various datasets for different features.

This normalization technique ensures all features are on a similar scale.

3.2. Temporal Features

Temporal features are critical in understanding user behavior patterns over time. One of the primary temporal features we consider is the time gap between consecutive purchases. This feature measures the time gap, in days, between the current purchase date and the next one. By studying these gaps, we can uncover patterns in user purchasing cycles, enabling us to predict future buying behavior more accurately. To compute the time gap feature, we use the following equation:

where

represents the gap between the

i-th and

-th purchase dates. This feature helps in identifying patterns such as frequent buyers, seasonal buyers, and occasional buyers. Additionally, we create aggregated statistics of these time gaps, such as the mean, median, standard deviation, and maximum time gap for each user. These aggregated features provide a summary of the user’s purchasing behavior over the observed period.

By incorporating these temporal features into our models, we enhance the predictive power by capturing the temporal dynamics of user behavior.

3.3. Dimensionality Reduction

Dimensionality reduction techniques are essential for managing high-dimensional data and improving model performance. This study uses Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to reduce the dimensionality of merchant transaction sequences for each card ID. SVD transforms high-dimensional transaction data into a lower-dimensional space, retaining most of the variance. The SVD process is mathematically expressed as:

where

X is the original data matrix,

U and

V are orthogonal matrices, and

is a diagonal matrix containing the singular values. By selecting the top

k singular values, we can approximate

X with a reduced representation:

In our case, we reduce the transaction sequences to a 5-dimensional space. This reduction simplifies the complexity of the data and enhances the efficiency of the subsequent machine learning models. To validate the effectiveness of SVD, we perform cross-validation and monitor performance metrics such as RMSE and MAE. The reduced dimensions not only improve computational efficiency but also mitigate the risk of overfitting by removing noise and redundant information.

3.4. Word2Vec Embeddings

Word2Vec embeddings are a powerful tool for capturing semantic relationships between entities in a dataset. In this study, we apply Word2Vec to create dense vector representations for merchant IDs, merchant category IDs, and purchase dates. These embeddings are useful for identifying contextual similarities between entities, based on how frequently they co-occur in transaction sequences. The Word2Vec model is trained using Skip-gram to predict context words from a target word. The objective function is:

where

T is the total number of words in the corpus,

c is the context window size,

is the target word, and

are the context words. After training the Word2Vec model, we obtain embeddings for each entity. These embeddings are then aggregated to create feature vectors for each card ID. Aggregation methods include calculating the minimum, maximum, average, and standard deviation of the embeddings for all transactions associated with a card ID.

where

is the embedding vector of the

i-th transaction, and

n is the total number of transactions for the card ID. The resulting feature vectors capture the inherent similarities and differences between different entities, enhancing the predictive power of our models. By leveraging Word2Vec embeddings, we effectively transform categorical data into a continuous vector space, enabling more sophisticated analysis and modeling.

4. Model Architecture and Methodology

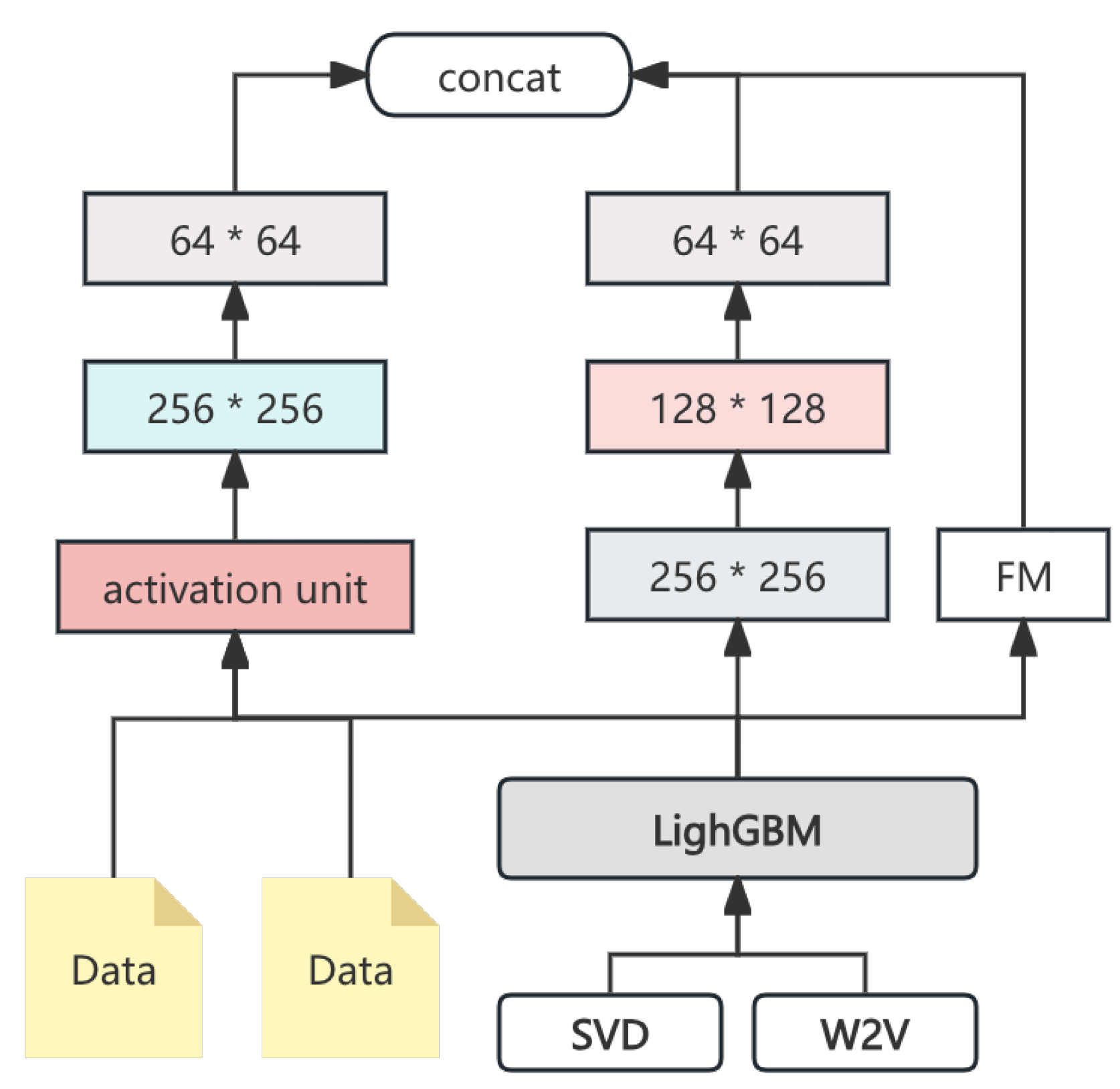

The primary models utilized in this study are LightGBM, DeepFM, and DIN, each contributing unique strengths to the predictive capabilities. The complete model ensemble pipeline is illustrated in

Figure 1.

4.1. Lightgbm

LightGBM is a gradient boosting framework that uses tree-based learning algorithms. It is designed to be distributed and efficient, capable of handling large-scale data.

where

l is the loss function,

is the regularization term,

is the true value, and

is the predicted value.

4.2. DeepFM

DeepFM combines factorization machines with deep neural networks to capture high-order feature interactions for recommendation tasks. DeepFM’s architecture combines two components: a factorization machine (FM) for low-order feature interactions and a deep neural network (DNN).

where

is the global bias,

are the weights of the first-order features,

are the latent vectors representing the features, and

denotes the dot product between the latent vectors. The DNN component captures the high-order feature interactions. The input to the DNN is the concatenation of the embeddings of the sparse features:

The DNN layers are defined as follows:

where

is the output of the

l-th layer,

and

are the weights and biases, and

is the activation function. The outputs of the DNN and FM components are combined for the final prediction:

4.3. DIN

The Deep Interest Network (DIN) uses attention mechanisms to dynamically capture user interests from relevant past behaviors. The core idea is to represent user interests as an aggregation of their historical behaviors, weighted by their relevance to the current context. The attention mechanism in DIN can be formulated as:

where

represents the hidden state of the

i-th historical behavior,

is the embedding of the current context, and score is a function that measures the relevance between

and

.

The weighted sum of historical behaviors forms the final representation of user interest.

After combining with the current context embedding, this representation is passed to a fully connected network for the final prediction.

where

and

are the weights and biases of the output layer.

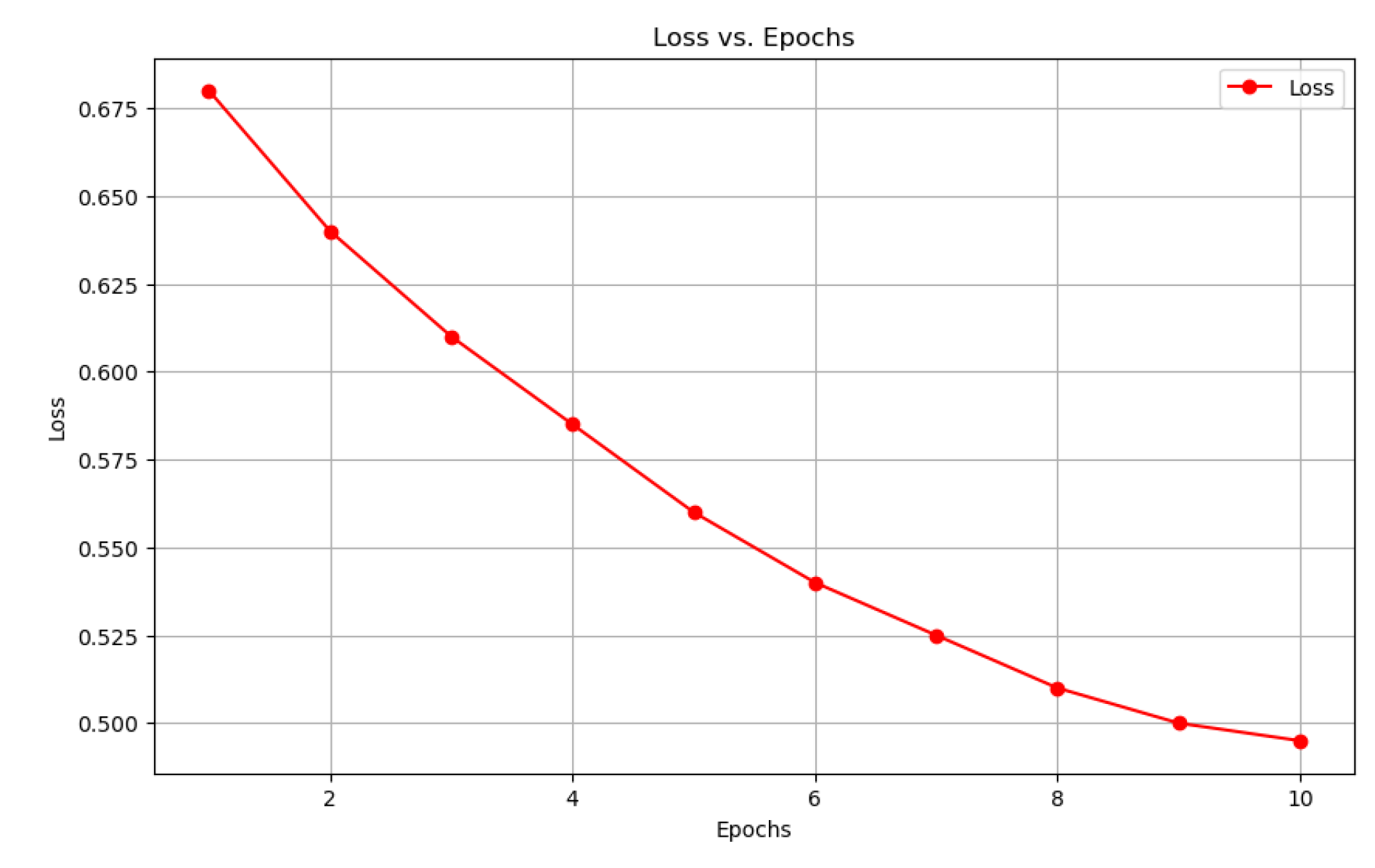

4.4. Loss

To optimize the models, we employ different loss functions tailored to each model’s architecture and objective. For the DeepFM model, We utilize the binary cross-entropy loss function, which is ideal for binary classification tasks.

For the DIN model, we use a similar binary cross-entropy loss but also experiment with other loss functions to capture sequence-specific information better:

4.5. Model Ensemble

To further enhance the predictive performance, we combine the predictions of multiple models using an ensemble approach. The ensemble method integrates the strengths of each model, reducing the overall variance and improving generalization. We apply a weighted average ensemble, where the final prediction is the weighted sum of individual model predictions.

where

K is the number of models,

is the prediction of the

k-th model, and

is the weight assigned to the

k-th model. The weights

are determined through cross-validation, ensuring that the ensemble model leverages the best-performing models more heavily. This approach allows us to capitalize on the diverse strengths of LightGBM, DeepFM, and DIN, leading to robust and accurate predictions. By combining these advanced models and techniques, we achieve a comprehensive solution for predictive analysis, capable of handling complex datasets and delivering high-performance results.

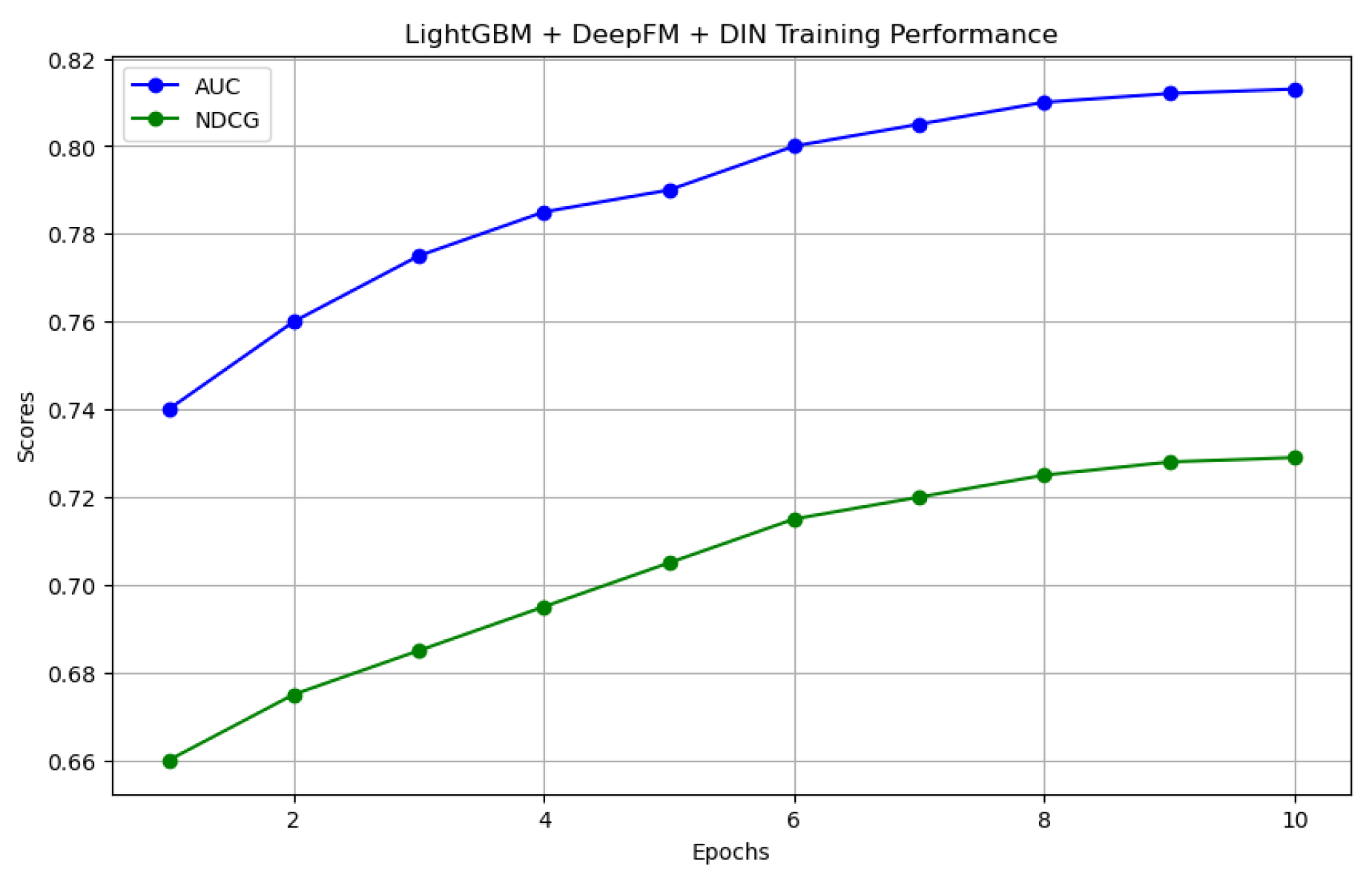

5. Experiments and Results

5.1. Metrics

To assess the impact of the personalized recommendation, we use AUC, recall, and NDCG as the key evaluation indicators.

5.1.1. AUC

AUC measures the model’s ability to distinguish between positive and negative classes, with higher AUC indicating better performance. It is calculated as the area under the ROC curve, which plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate.

where

is the true positive rate and

is the false positive rate at threshold

t.

5.1.2. NDCG

NDCG measures the quality of the model’s ranking, giving higher scores for correct predictions that appear earlier in the list. The formula for Discounted Cumulative Gain (DCG) at position

p is defined as:

where

is the relevance score of the item at position

i. The Ideal Discounted Cumulative Gain (IDCG) is the maximum possible DCG for a given set of items. NDCG is then given by:

Ranging from 0 to 1, NDCG values reflect better ranking performance as they increase. By using these diverse metrics, we provide a comprehensive evaluation of the models’ performance, capturing both prediction accuracy and ranking quality.

5.2. Performance

The models were evaluated on a public test set, with performance measured by the metric we mentioned before. The results are summarizedin

Table 1:

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, we illustrates the importance of comprehensive data preprocessing and feature engineering in predictive modeling. By integrating LightGBM, DeepFM, and DIN, we achieved significant improvements in prediction accuracy. Future work will explore further optimization and real-world application of these methodologies.

References

- He, X.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Nie, L.; Hu, X.; Chua, T.S. Neural collaborative filtering. Proceedings of the 26th international conference on world wide web, 2017, pp. 173–182.

- Cheng, H.T.; Koc, L.; Harmsen, J.; Shaked, T.; Chandra, T.; Aradhye, H.; Anderson, G.; Corrado, G.; Chai, W.; Ispir, M.; others. Wide & deep learning for recommender systems. Proceedings of the 1st workshop on deep learning for recommender systems, 2016, pp. 7–10.

- Guo, H.; Tang, R.; Ye, Y.; Li, Z.; He, X. DeepFM: A factorization-machine based neural network for CTR prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.04247 2017.

- Zhou, G.; Mou, N.; Fan, Y.; Pi, Q.; Bian, W.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, X.; Gai, K. Deep interest evolution network for click-through rate prediction. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 5941–5948. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Yu, B.; Liu, M.; Guo, L.; Tian, L.; Huang, J. Utilizing Large Language Models to Illustrate Constraints for Construction Planning. Buildings 2024, 14, 2511. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zou, D.; Qin, H. Enhancing Healthcare through Large Language Models: A Study on Medical Question Answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04138 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Xie, X.; Guo, M. DKN: Deep knowledge-aware network for news recommendation. Proceedings of the 2018 world wide web conference, 2018, pp. 1835–1844. [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572 2014.

- Wu, D.; Xia, S.T.; Wang, Y. Adversarial weight perturbation helps robust generalization. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 2958–2969.

- Tang, J.; Qu, M.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Yan, J.; Mei, Q. Line: Large-scale information network embedding. Proceedings of the 24th international conference on world wide web, 2015, pp. 1067–1077. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Du, T.; Wang, J. Deep Learning over Multi-field Categorical Data: –A Case Study on User Response Prediction. Advances in Information Retrieval: 38th European Conference on IR Research, ECIR 2016, Padua, Italy, March 20–23, 2016. Proceedings 38. Springer, 2016, pp. 45–57.

- He, X.; Zhang, H.; Kan, M.Y.; Chua, T.S. Fast matrix factorization for online recommendation with implicit feedback. Proceedings of the 39th International ACM SIGIR conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2016, pp. 549–558. [CrossRef]

- Covington, P.; Adams, J.; Sargin, E. Deep neural networks for youtube recommendations. Proceedings of the 10th ACM conference on recommender systems, 2016, pp. 191–198. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).