1. Introduction

The launching of multiprocessor computers changed permanently the way we deal with designing code. Moore’s Law predicted the doubling of processor frequency every 2 years [

1], but this projection cannot be sustained indefinitely. Consequently, the emphasis is on using the parallel or concurrent power of processing, using multiprocessors. Solving multiple tasks simultaneously represents concurrency [

2,

3]. The Java programming language [

4,

5] allowed from its beginnings multiple threads, through the management of the Thread class [

6]. This could be changed by a custom implementation that overrides the run() function. Also, the composition principle can be used, implying creating a customized class that implements Runnable [

7], with instances of this class being offered as arguments to the constructor of the Thread class. After the introduction of the java.util.concurrent package, programmers could use classes that abstract the work with multiple threads [

8]. This offers the following data structures specific for working with threads: queues, lists, and maps. Also, these classes offer factory methods for working with implementations of the Executor class, such as ExecutorService and ScheduledExecutorService, or interfaces such as ThreadFactory or Callable. Using this package, the step to asynchronous programming is done. Later, the asynchronous programming migrated to reactive programming, based on the Flow class which follows the Reactive Streams specifications [

9].

In a world in which social media exploded, apps should find methods to use the resources more efficiently. Consequently, a new approach to processing data was found. In the synchronous approach, N tasks were executed by N threads. If one task is reading from the network or database, the thread in use is blocked without doing anything useful. The need for a change was promoted by many computer science engineers, to reduce the processing time.

A great part of processing moved to the Cloud, allowing the usage of performant machines by any company [

3]. However, when using Cloud providers [

10] of services such as PaaS or IaaS [

11] you must pay for every extra processor. How can we do more with fewer processors?

Given N tasks, each of them requires M seconds, from which half is necessary for processing and half for retrieving data. There are also P processors. We consider wall time as the time shown by a clock on the wall that passes between the moment when the processor starts solving the tasks and the time shown by the same clock when the processor finishes its job. The wall time in a synchronous approach would be , if N is not a multiple of P, or if N is a multiple of P. The number of processors is fixed, and so is the time needed for the execution of a task. Using a programming paradigm in which one thread is not blocked during data retrieval would be a great improvement. The asynchronous approach does exactly that. Every thread solves multiple tasks so that the processor is used more effectively. When a task is blocking the thread, the processor switches to a new task. In the asynchronous paradigm, the wall time would be , if N is not a multiple of P, or , if N is a multiple of P. That means the time would be almost twice as short to achieve the same thing.

Asynchronous functions, compared to synchronous ones, are non-blocking. They are returning a substitute for the answer immediately after they are called, such as Mono, finishing their work later. The thread from which the asynchronous method was called can continue its work without waiting for the entire processing to be done and instead uses the substitute offered by the method. This approach has its drawbacks because sometimes it’s harder to determine when the work is finished. The fact that the function returned doesn’t mean that all calculations were done.

2. Objectives

The objectives of the current paper are to determine the optimal conditions to decide between concurrent programming and asynchronous programming in a multi-layered design of a Java application. The advantages and disadvantages of various types of programs will be analyzed. To determine which approach is more performant and in which situation, a system that interacts with a database that contains data from an electronic devices store will be used. Several types of queries will be used to obtain a wider view and to show the behavior in different environments. An important goal is to obtain concrete numeric values, which can measure the time necessary for every experiment so that decisions can be made based on facts. The overall objective is to obtain a competent point of view on what programming approach should be used (synchronous or asynchronous) and in which situations when designing a multi-layered application using Java.

3. Related Work

Modern web applications face rapidly growing user demands and data volumes, increasing the need for high concurrency. Ju, Yadav et. al investigate how asynchronous frameworks and database connection pools improve web application performance in such environments [

12]. Asynchronous frameworks enable non-blocking request handling, freeing up thread resources and boosting concurrency. Database connection pools reduce connection management overhead, easing database load. By using Spring WebFlux and optimized connection pool configurations, this model achieves lower response times, higher throughput, and improved stability, outperforming both synchronous models and async setups lacking connection pooling. These findings offer practical guidance for enhancing application performance.

In recent years also comparative studies have been done to determine the best choice for developing modern web apps. Catrina compares the Spring WebFlux framework, representing asynchronous programming, against Spring Boot MVC, which represents synchronous programming [

13]. Response times, performance metrics, and resource usage are analyzed while varying the workload for the apps. In the end, this research shows that the app based on WebFlux has a similar response time to the MVC one but lesser resource utilization.

Wycislik and Ogorek compare synchronous and asynchronous frameworks as well as database drivers (JDBC and R2DBC) [

14]. This study uses both relational (Postgres) and non-relational databases (MongoDB) and demonstrates that in some cases the synchronous approach might be faster than the asynchronous one. The experimental stage for the Postgres reactive driver is deemed to be the factor for the success of the synchronous applications.

Rao and Swamy examine the relevance of synchronous and asynchronous web applications [

15]. For asynchronous versions, high scalability is presented as one of the main advantages over their synchronous counterparts. Also, fewer threads and memory are used to obtain similar performance in the async version.

Rankovski and Chorbev examine the impact of asynchronous I/O calls on web application scalability, focusing on increasing request throughput and reducing response time [

16]. Traditionally, web development frameworks primarily used blocking I/O APIs, complicating asynchronous implementation and maintenance. Recent advancements, such as improved asynchronous syntax in .NET, aim to enhance developer experience and promote asynchronous programming. The .NET platform shares a lot of similarities with the Java ecosystem and thus was chosen for related work for synchronous versus asynchronous articles. The study evaluates these syntax improvements in .NET, presenting and analyzing the resulting performance benefits.

4. Current Approaches

To create concurrent programs in a structured way, Bijlsma, Huizing, et al. designed an investigation methodology [

17]. Many books only provide a framework for syntax and examples. The article provides a methodology broken down into steps small enough and clear enough to be understood that provides a basis for understanding the concurrent way of working and its applications.

This consists of 7 steps:

Structuring the domain problem without concurrency. In this stage, the process is created sequentially, the focus being on the creation of a class structure necessary to solve the problem.

Analyzing the concurrency of the problem. It is determined which activities can be performed concurrently, which activities cannot be performed concurrently, how many threads are needed and for which activity.

Analyzing the conditions that lead to concurrent access to common data. To avoid inconsistent states, it is necessary to create UML diagrams [

18] to see if threads access common variables. Access to them must be synchronized.

Analyzing conditions that lead to check-and-then-act concurrent access. Any situations where a value is first read and then modified must be checked. After the value has been read, another thread may have modified it, and thus the current thread may no longer be able to make changes based on the latest information.

Reflect on the application. Analyzing the code and determining if improvements could be made. Determines if classes are thread-safe.

Apply nested locks [

19]. It checks if multiple locks are needed and implements them in a deadlock-free manner.

Analyze and eliminate deadlock. This step is looking for situations where an F1 thread holds the lock on a resource, let’s call it A. It needs another resource to continue calculations, let’s call it B. This is owned by an F2 thread which in turn needs a resource A. Each one needs the resource over which another thread has control, they cannot proceed further and the program hangs.

Kragl, Qadeer, and Henzinger provide means to apply operations that can help programmers obtain the synchronous equivalent of an asynchronous program [

20]. Synchronous programs provide high predictability and can be easily traced because the effects of a function can be seen when it returns a result. Asynchronous programs are hard to predict because of the calculations that can still be done after the function returns a response. The solution offered is synchronization, as a rule for checking asynchronous programs by absurdly assuming, demonstratively, that asynchronous operations finish as if they were synchronous. It summarizes asynchronous computation by synchronizing as an immediate atomic effect.

As we can see a shift in client-server systems [

21,

22] to an asynchronous approach, Zhang, Wang, and Kanemasa conducted a test to see if the new approach lives up to expectations [

23]. They performed a series of micro and macro tests to be able to examine the behavior of the servers. The conclusion was that asynchronous servers can perform worse than those based on working directly with threads and remote procedure calls if certain factors are not considered. Two arguments have been supported. The first one is that the approach of using a handler for each event can create many context switches for the asynchronous server and consequently the performance is affected. The second one is that workload and network conditions can negatively impact asynchronous servers but not synchronous ones. The article proposes a hybrid approach that uses the advantages of each approach.

High-performance internet servers have been studied intensively before. Many have concluded that asynchronous ones are the most advantageous over those that use direct threads and remote method calls. However, creating them is a challenge considering that the code generation and debugging stage is difficult due to the execution control hidden from the developer. It has been observed that sending a large amount of data from the server, due to the non-blocking nature of asynchronous functions, leads to frequent unnecessary repeated input/output (I/O) calls. Because a handler is created for each event, multiple intermediate events are created as well, and context changes that could have been avoided. As an example of such systems, Tomcat [

24] version 7 synchronous was compared with version 8 asynchronous. Other middleware such as Jetty [

25], GlassFish [

26], and MongoDB Asynchronous Driver [

27] were also compared [

28]. For a 100KB response message, an asynchronous server can cause a write-spin problem [

29], due to the small size of the TCP buffer, and the TCP wait-accept mechanism, wasting between 12% and 24% of central processing unit (CPU) resources processing. By the wait-accept mechanism, we refer to the method by which the TCP protocol verifies that the packets have reached their destination, a method that represents the major difference from UDP. The thread writes until it fills the TCP buffer. Sending messages over the Internet to the destination begins. Then the recipient must respond with ACK, a message that the data has been received and the transmission can continue. As long as the data is being sent and until the ACK message arrives, no data can be pushed into the buffer, but the thread keeps trying to send, wasting resources.

Zhang, Wang, and Kanemasa conclude that a major improvement can be obtained by using the asynchronous approach, but carefully calibrating the system for large response sizes and adverse network conditions [

23].

4. Proposed Projects

For the design of a multi-layered Java application, the technologies stack provides alternatives at each level:

JDBC (Java Database Connectivity) [

30] is an API (application programming interface) used by the Java programming language to specify the interaction between the program and the database. The technology was introduced in the very early versions of Java and it is synchronous (blocking) by nature. This means that, while executing I/O operations [

31], a thread will be blocked until data can be read, or the data is fully written.

R2DBC (Reactive Relational Database Connectivity) [

32] is a specification to access databases through reactive drivers. R2DBC is a non-blocking API, it can manage more connections using fewer threads.

MVC (Model-View-Controller) [

33] is a design pattern to develop user interfaces, separating the program into three interconnected elements: the model (the internal representation of the information), the view (the way the information is presented to the user), and the controller (it receives inputs and generates commands for the model or the view).

WebFlux [

34] is a parallel version of MVC provided by the Spring framework and supports fully non-blocking reactive streams.

To investigate the two design approaches, the synchronous and the asynchronous one, we created several projects, as follows:

P_JDBC, to directly interact with a database from a Java program using a synchronous JDBC driver and execute a series of CRUD (Create, Read, Update, and Delete) operations.

P_R2BC, to directly interact with a database from a Java program using an asynchronous R2DBC driver and execute a series of CRUD operations.

P_JDBC_MVC, to create a web application to access the database through JDBC. It is fully synchronous, being based only on synchronous libraries and a synchronous application server.

P_JDBC_WebFlux, to create a web application using WebFlux accessing the database through JDBC. It uses a synchronous database driver and an asynchronous web stack.

P_R2DBC_MVC, to create a web application to access the database through R2DBC. It uses an asynchronous dataset driver and a synchronous web stack.

P_R2DBC_WebFlux, to create a web application using WebFlux, accessing the database through R2DBC. It is fully asynchronous, uses database and web asynchronous libraries, and runs on an application server designed to be reactive.

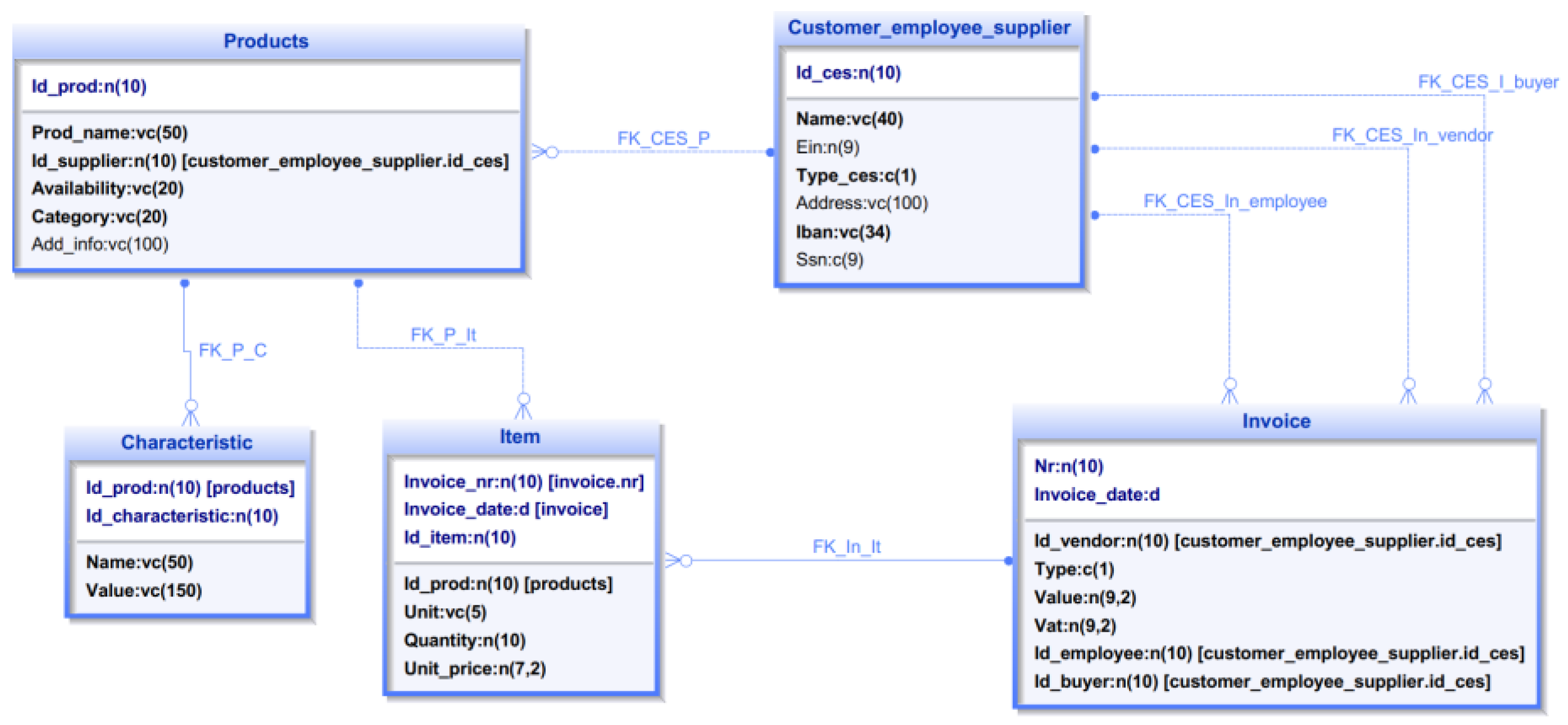

All projects will be tested with a program that simulates a great number of concurrent users and generates a fixed number of requests one after the other. The database schema that was used by all projects consists of 5 tables (

Figure 1).

These tables have primary keys, not null, and foreign key constraints to maintain the data consistency. Together, they represent all data that is needed by an IT Store:

The Products table, with the columns: Id_prod (Primary Key), Prod_name, Id_supplier, Availability, Category, Add_info.

The Characteristic table is in a master-detail relationship with Products, with the columns: Id_prod, Id_Characteristic, Name, and Value.

The Customer_employee_supplier table contains information about clients, employees, and suppliers. Every row is identified by a unique number, the primary key. One column is used to determine the person type: ’c’ for client, ‘e’ for employee, and ‘s’ for supplier.

The Invoice table contains information about the invoices. The primary key consists of two columns: Nr and Invoice_date.

The Item table, with a primary key formed by three columns: Invoice_nr, Invoice_date, and Id_Item.

5. Experiments and Results Analysis

5.1. Database Connectivity

The first test analyzes the database connectivity with no concurrency and a small load. The database used in this case is PostgreSQL [

35], one of the most known and performant relational databases [

36]. The interaction of the program with the database is done by executing JUnit 5 tests [

37] and the Spring Data API [

38].

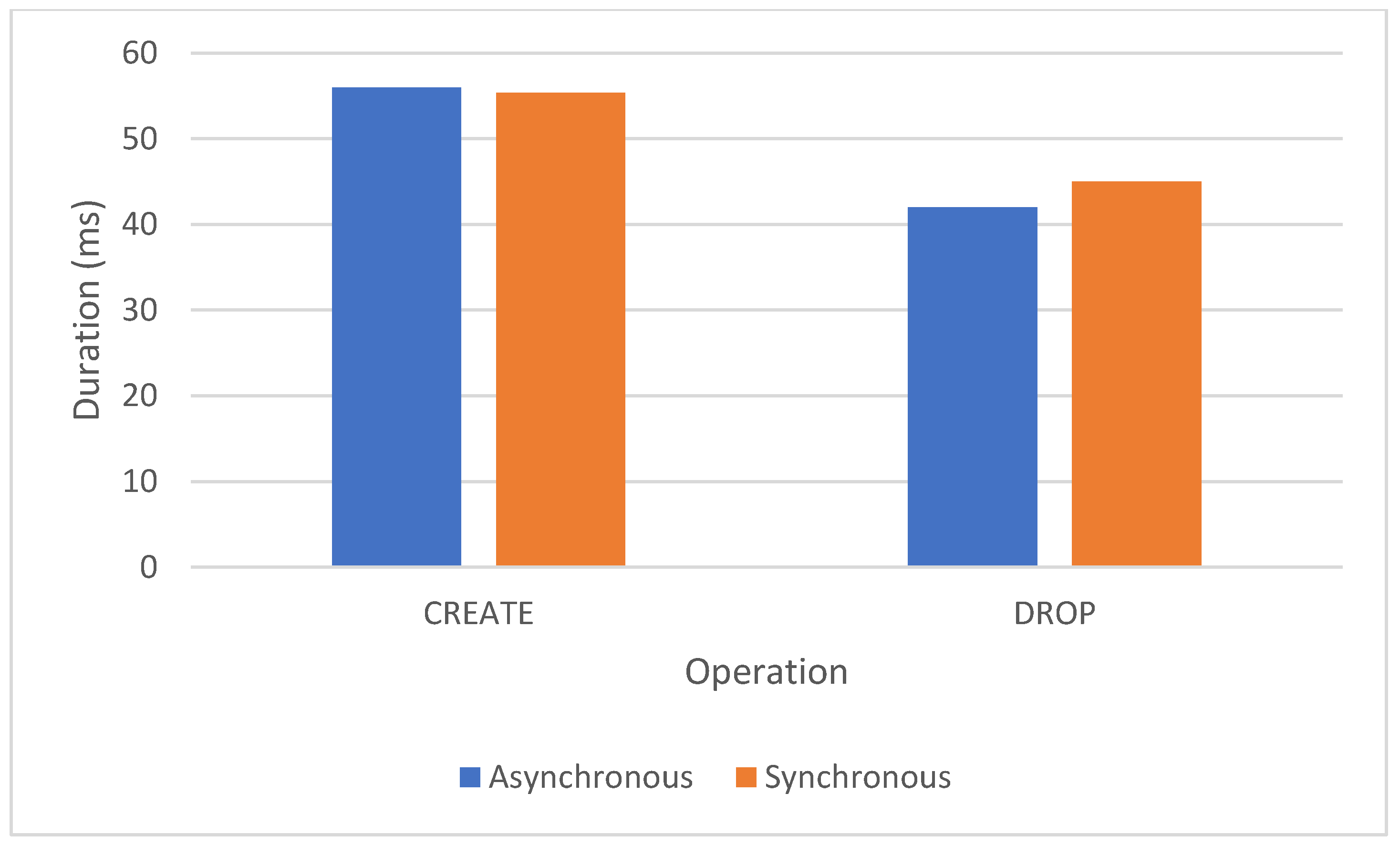

As seen in

Figure 2, we have two types of instructions: Create and Drop. The test for Create contains 5 such statements. The Drop test also contains 5 statements. Each test contains ALTER TABLE statements to add or remove foreign key constraints.

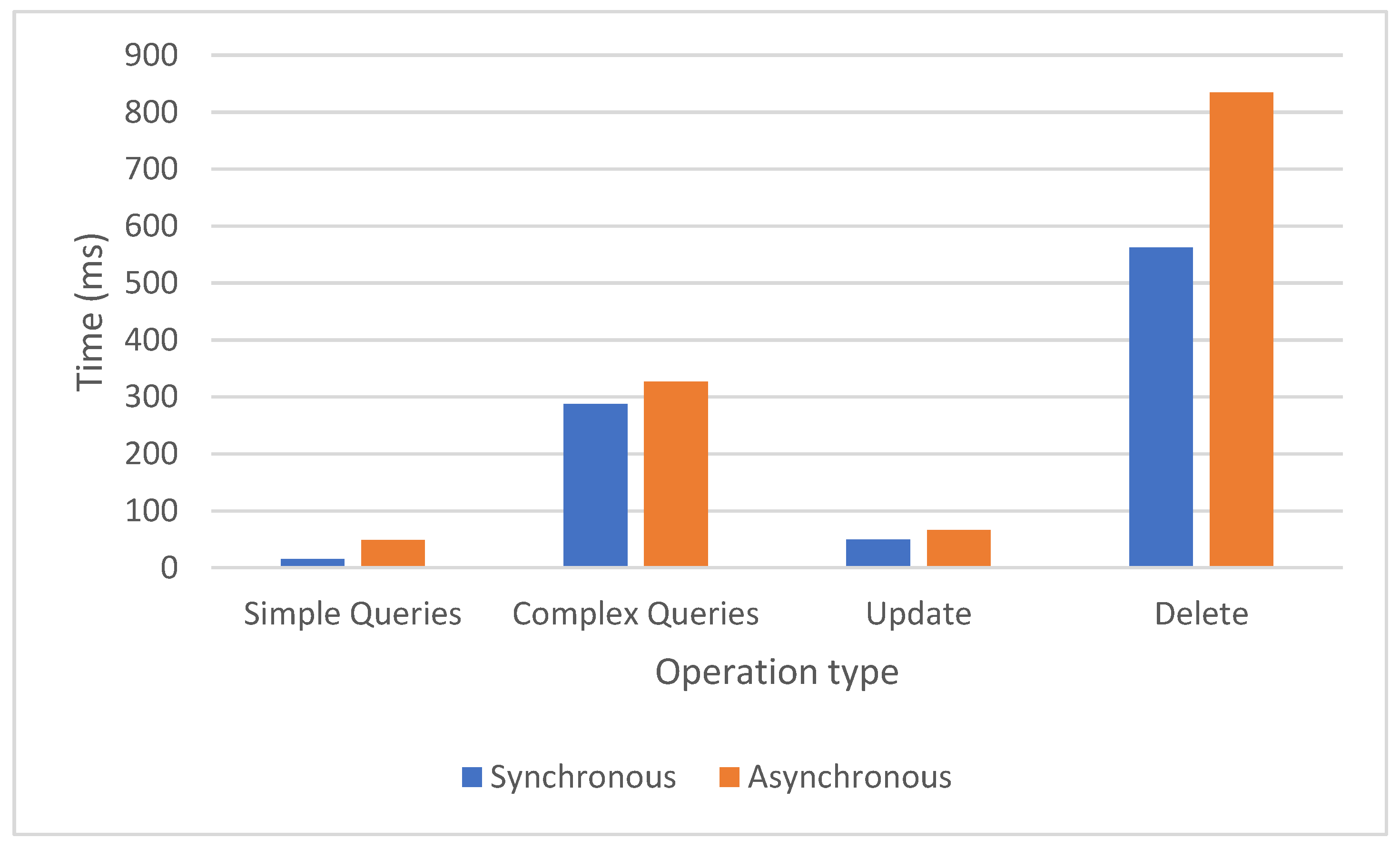

Figure 3 shows the duration of 4 experiments, each experiment being done as only one customer is using the database at a time, as follows:

The first experiment executes 4 simple queries.

The second experiment calls 4 complex queries.

The third experiment executes 3 updates.

The last experiment deletes all data from the database.

The synchronous approach is faster, the difference between the average durations being up to almost 50 milliseconds.

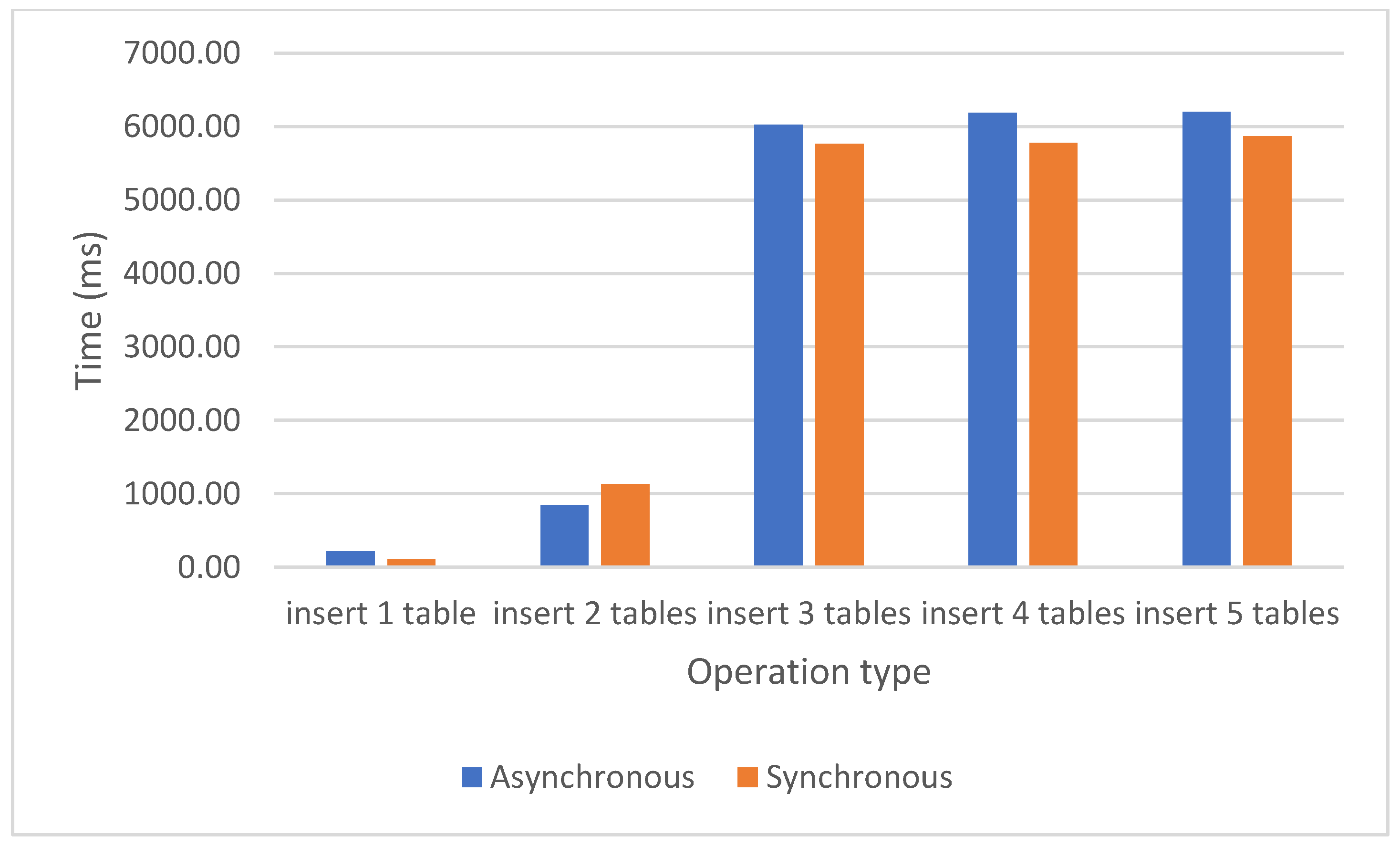

Figure 4 presents the results of 5 INSERT tests, from inserting into one table up to inserting into 5 tables. Also, in this case, the average duration is lower for the synchronous approach, the difference between the approaches starting from 111 milliseconds in the first test and reaching 336 milliseconds in the last test.

5.2. REST Services

We’ll move on to addressing both the database and the web connectivity. The projects created for the experiments use either synchronous or asynchronous drivers for interacting with the database and web clients.

Simple Queries

Testing the REST API [

39] starts with simple queries:

Retrieve customers, doing a simple filtering operation on Customer_Employee_SupplierTable based on the type_ces field.

Retrieve all characteristics of a certain product.

Obtain the invoice with the greatest value, by applying an aggregate function on the Invoice table.

Retrieve the items that are sold between certain dates. This is a little bit more complex, using a join between the Invoice and the Item tables and filtering using date-related functions.

One goal is to generate realistic scenarios. Consequently, using JMeter [

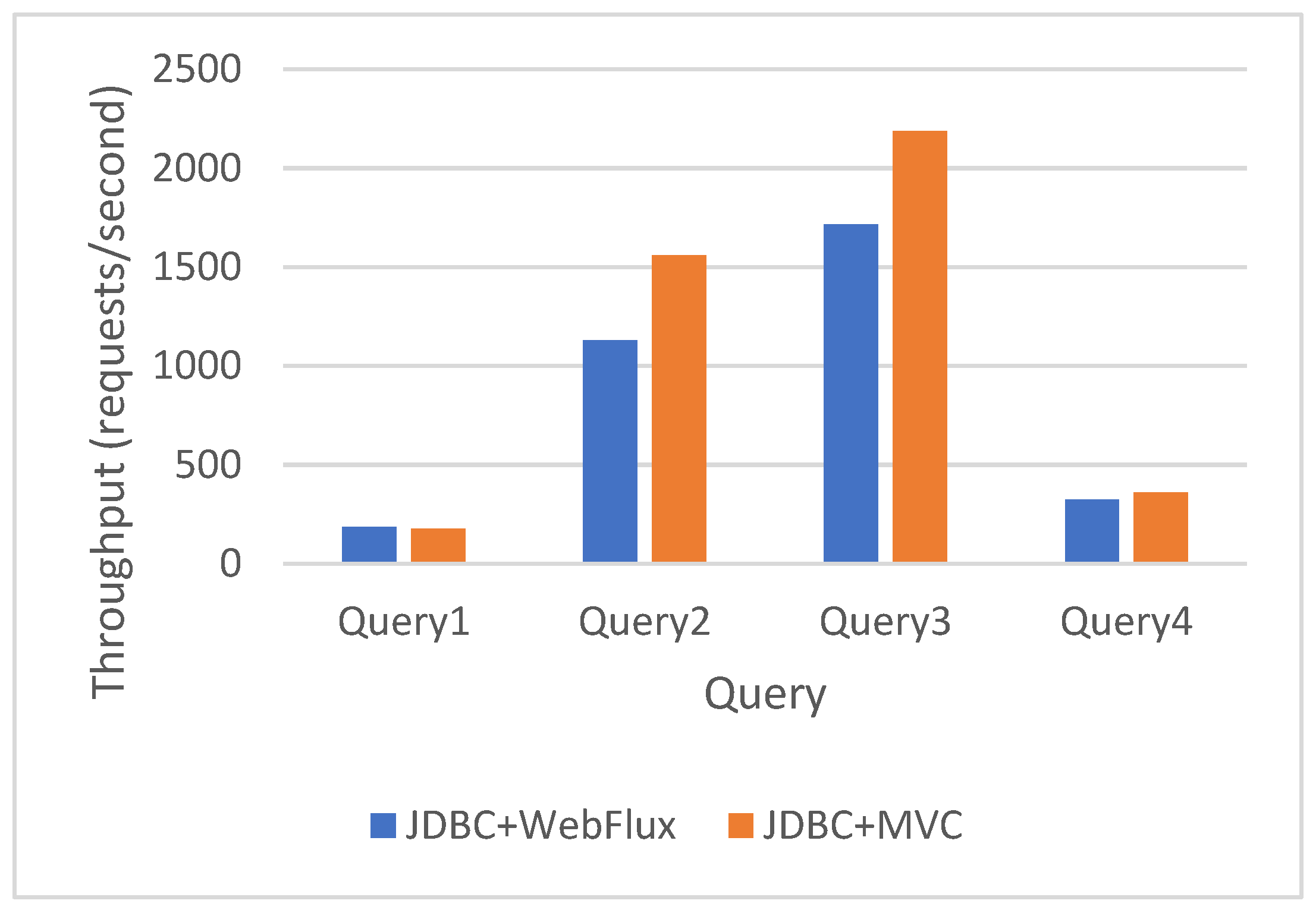

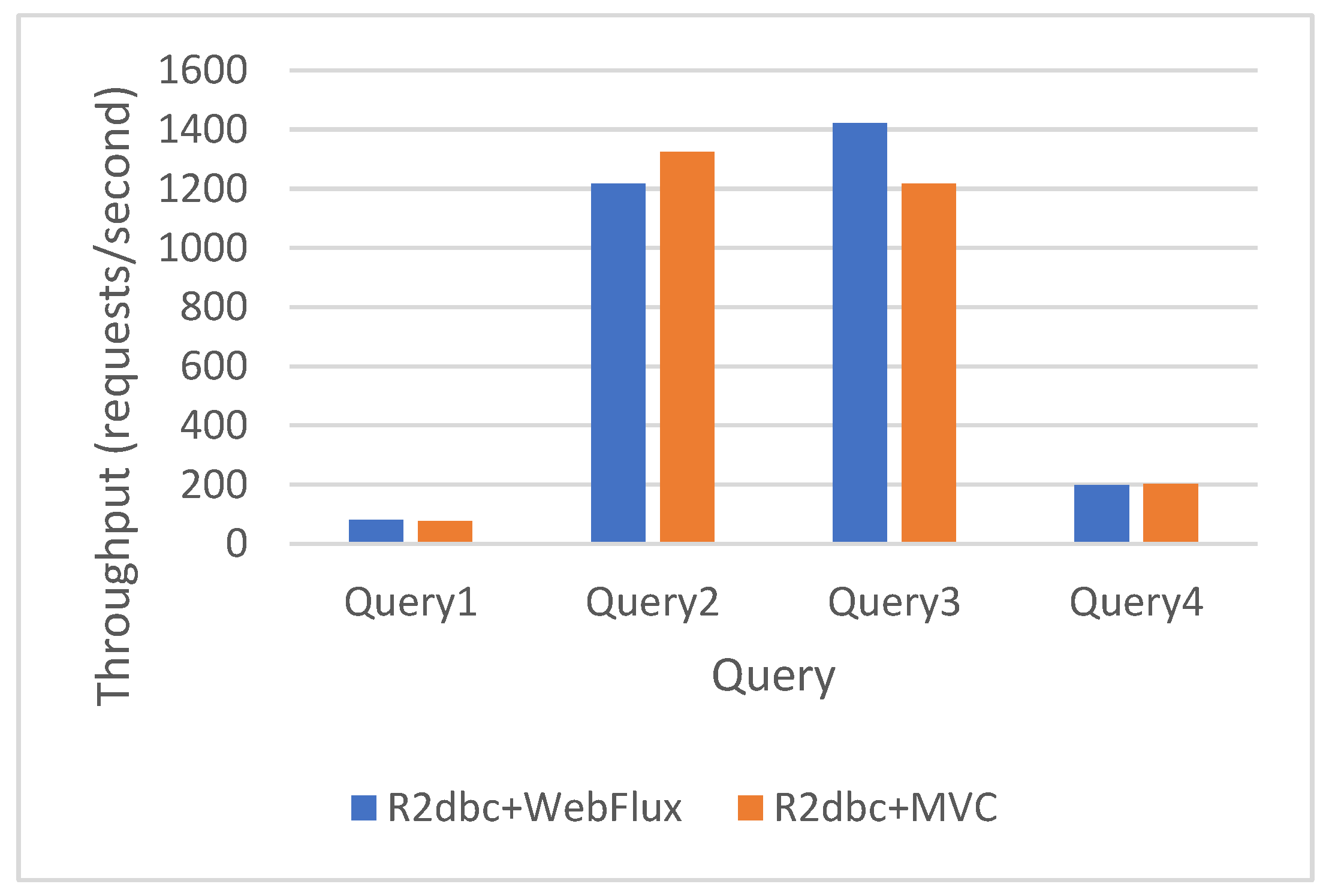

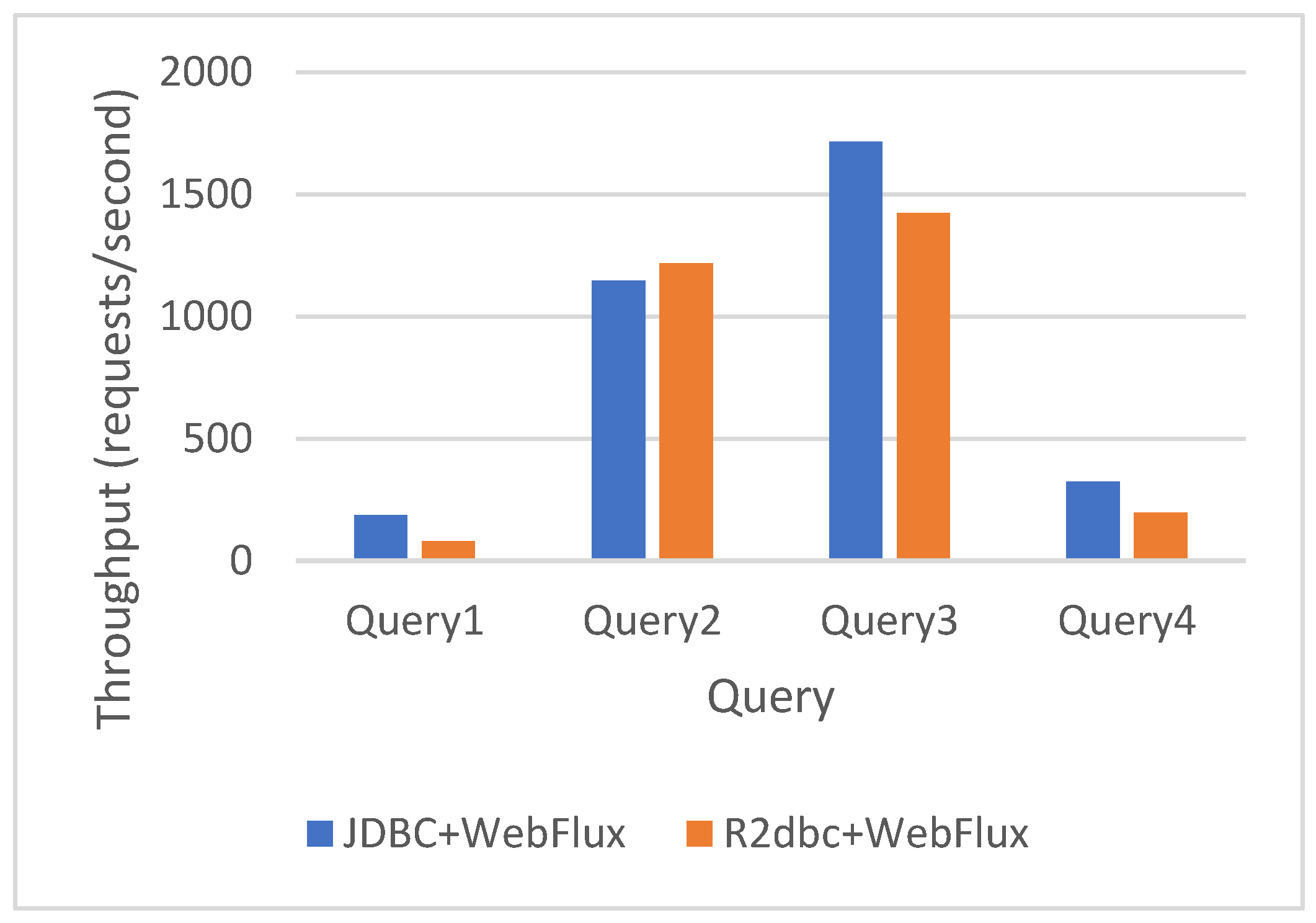

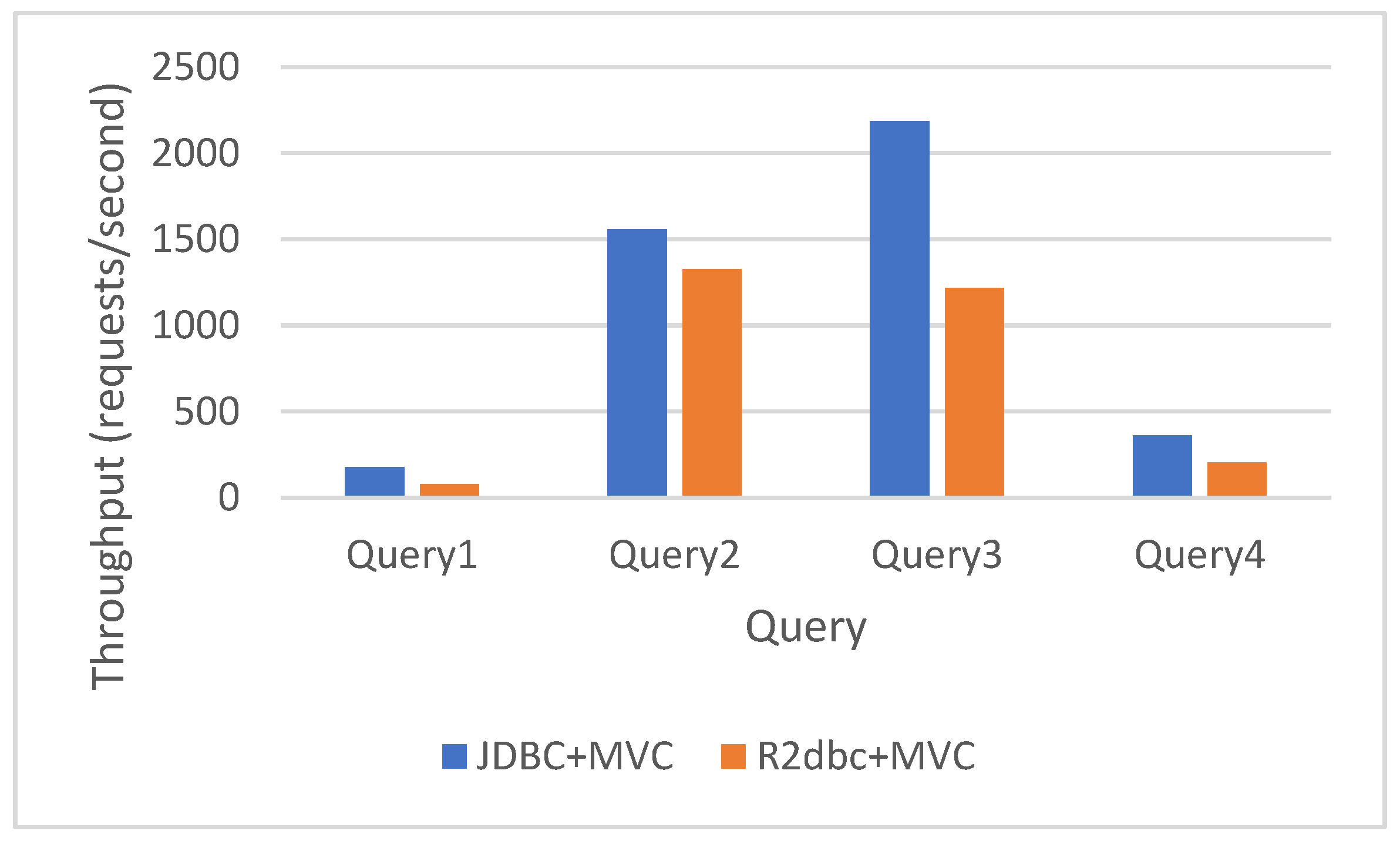

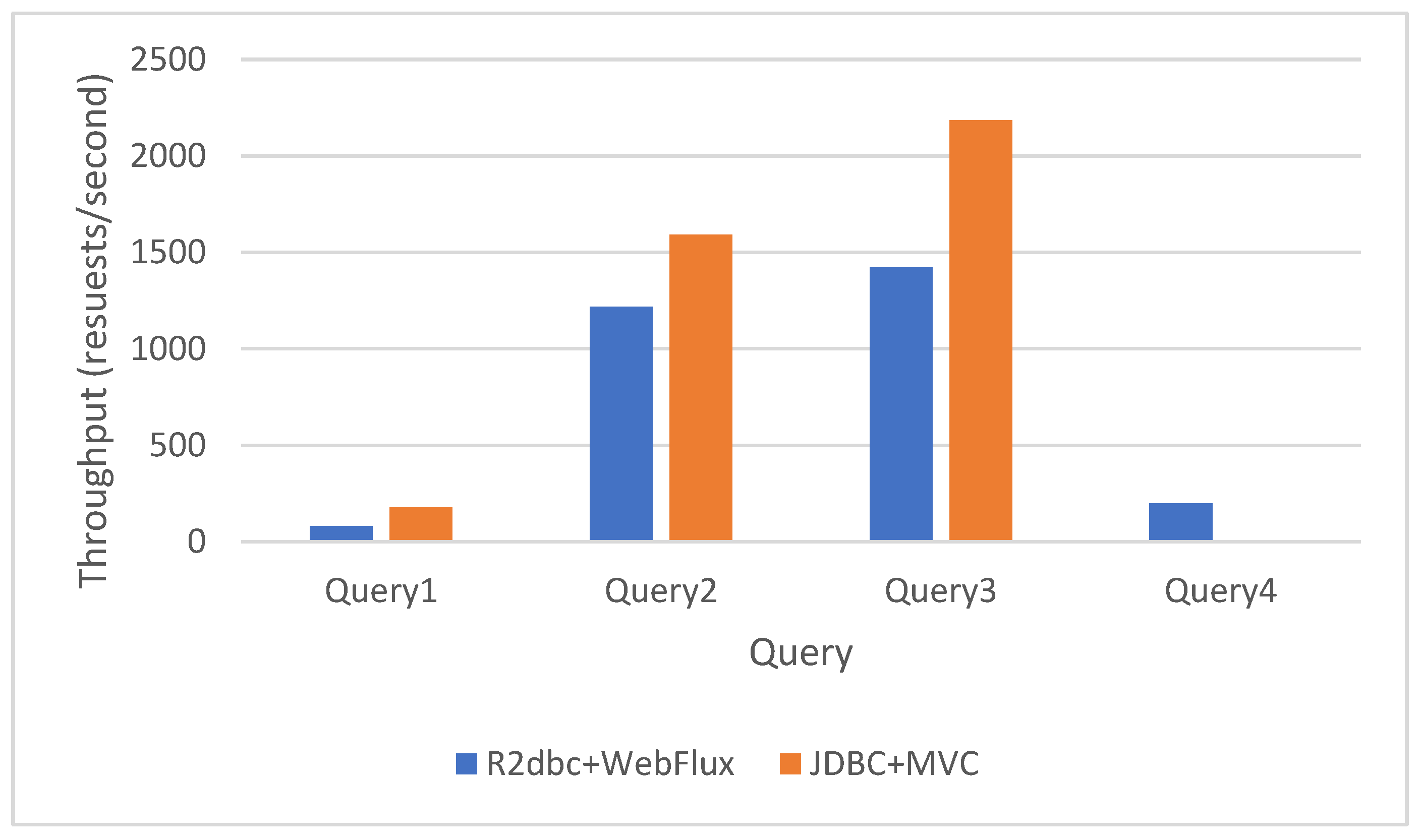

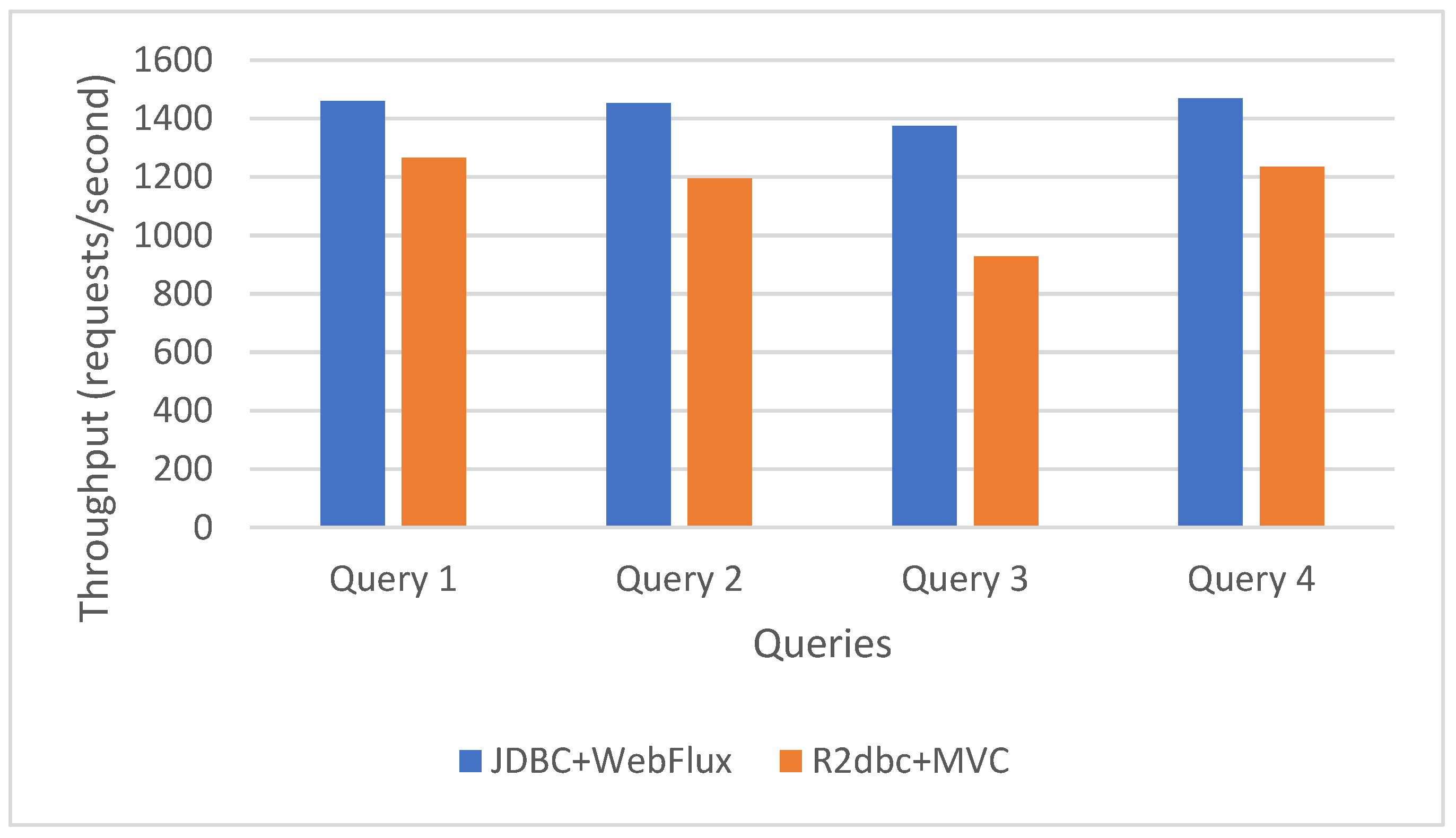

40], 400 users are simulated (every user is represented by a thread), each of them executing the current query 10 times. All users are simultaneously sending requests, each user sends the next request after receiving the answer for the previous one. The throughput is measured in requests per second. Each of the four tests is repeated 10 times, and the average of the 10 throughputs is displayed. The results of these tests are displayed in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, with the throughput displayed in requests per second processed by the Java REST API. Using JDBC, WebFlux has a smaller throughput than MVC (

Figure 5). As JDBC is a synchronous driver, it works better with a synchronous Java framework.

Using R2DBC, WebFlux has a higher throughput than MVC when executing Que-ry3, though a smaller throughput when executing Query2. The results for Query1 and Query4 are comparable and do not show a clear winner (

Figure 6).

WebFlux JDBC has a higher throughput than WebFlux R2DBC in all cases except Query 2, as shown in

Figure 7. This can be explained as the endpoint that uses Query 2 returns a list of Characteristic Java objects as a JSON file.

R2DBC MVC has a smaller throughput than JDBC MVC in all cases, as shown in

Figure 8.

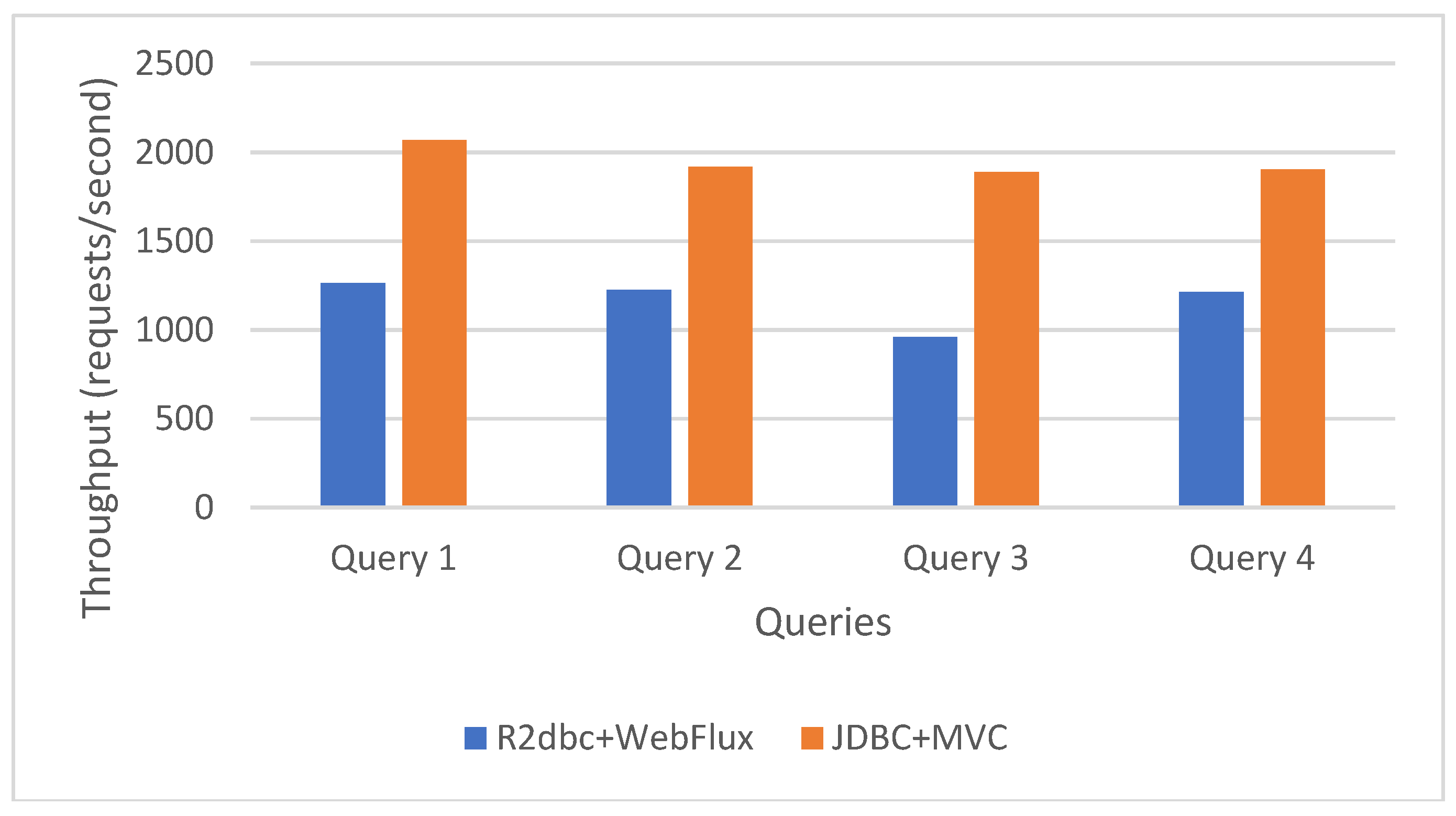

Finally, we compare the pure synchronous vs. the pure asynchronous alternative, including both the driver and the web frameworks. As shown in

Figure 9, the synchronous version (JDBC MVC) always has a higher throughput than the asynchronous one (R2DBC WebFlux).

Complex Queries

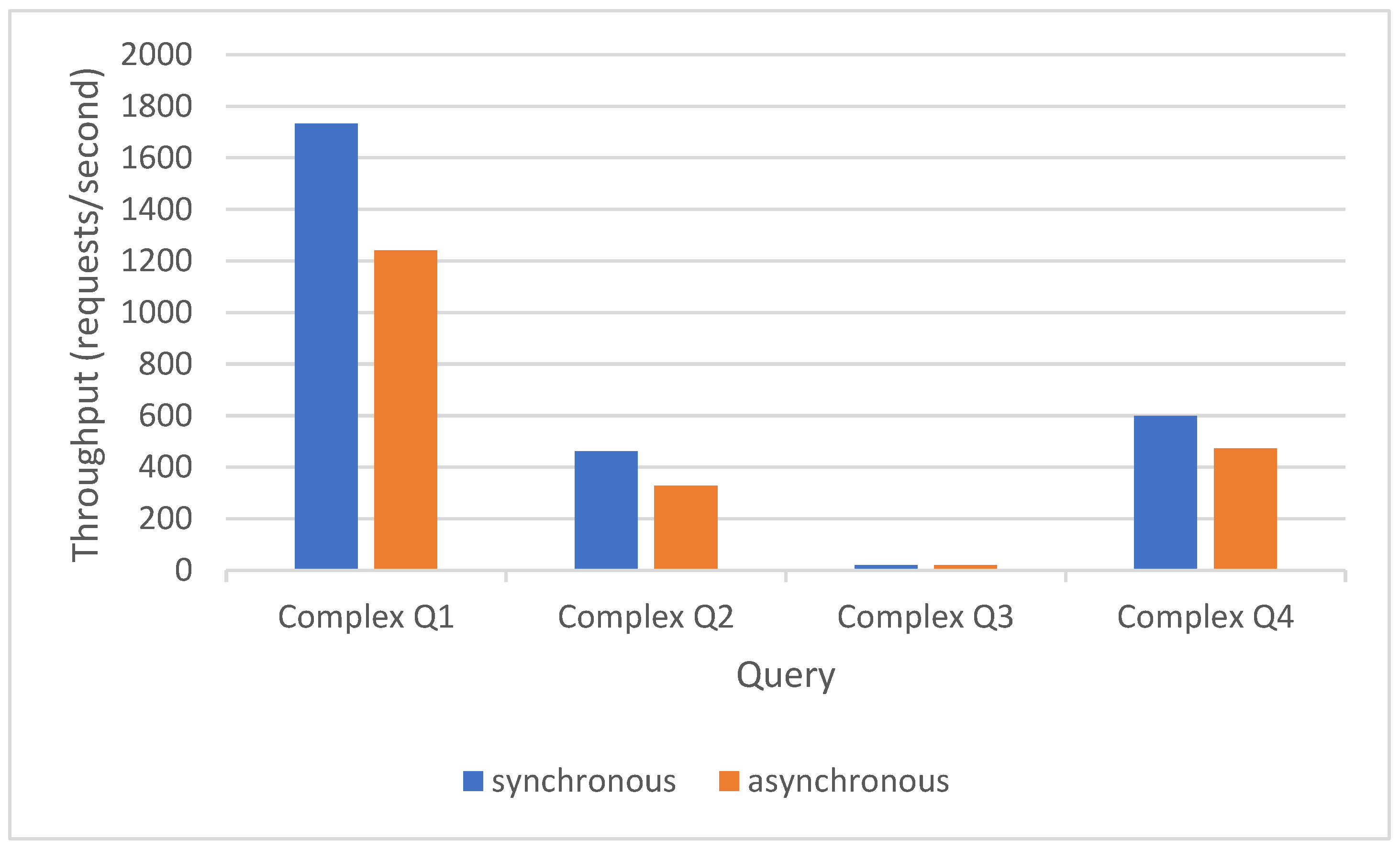

To provide significant results, we’ll move now to analyzing the execution of complex queries, in the context of similar combinations of synchronous/asynchronous layers of the application.

The tests from

Figure 10 were run simulating 400 concurrent users and each query was executed 10 times by every single user. The average of these 10 executions is shown in the graphic.

The executed queries do the following:

Retrieve the sales and costs for every month and year. Date and time functions are used at the database level to extract the month and year from the invoice_date field of the Invoice table. The query includes two subqueries, one for sales and one for costs, that are joined on their month and year fields. This can be used to determine what months are greater for sales and what years have brought a greater profit.

Calculate the profit for each month. A date function is used for extracting month and year. The query includes two subqueries and calculates the profit as the difference between sales and costs. This query determines the best months for the company.

Find the product with the greatest profit for each category. The query computes the profit for every product, the result is then filtered with a correlated subquery that retrieves the maximum profit for the current category.

Find the profit for each category. The query includes two subqueries, one calculating the sales and the other the costs for each category. The difference between the two values gets the profit for each category.

The pure synchronous approach performs better. JDBC makes the main difference, as both projects that use it are much faster than those that do not. The projects that use R2DBC have a lower throughput, using MVC or WebFlux with R2DBC does not make such a difference, the executed queries returned just a few data.

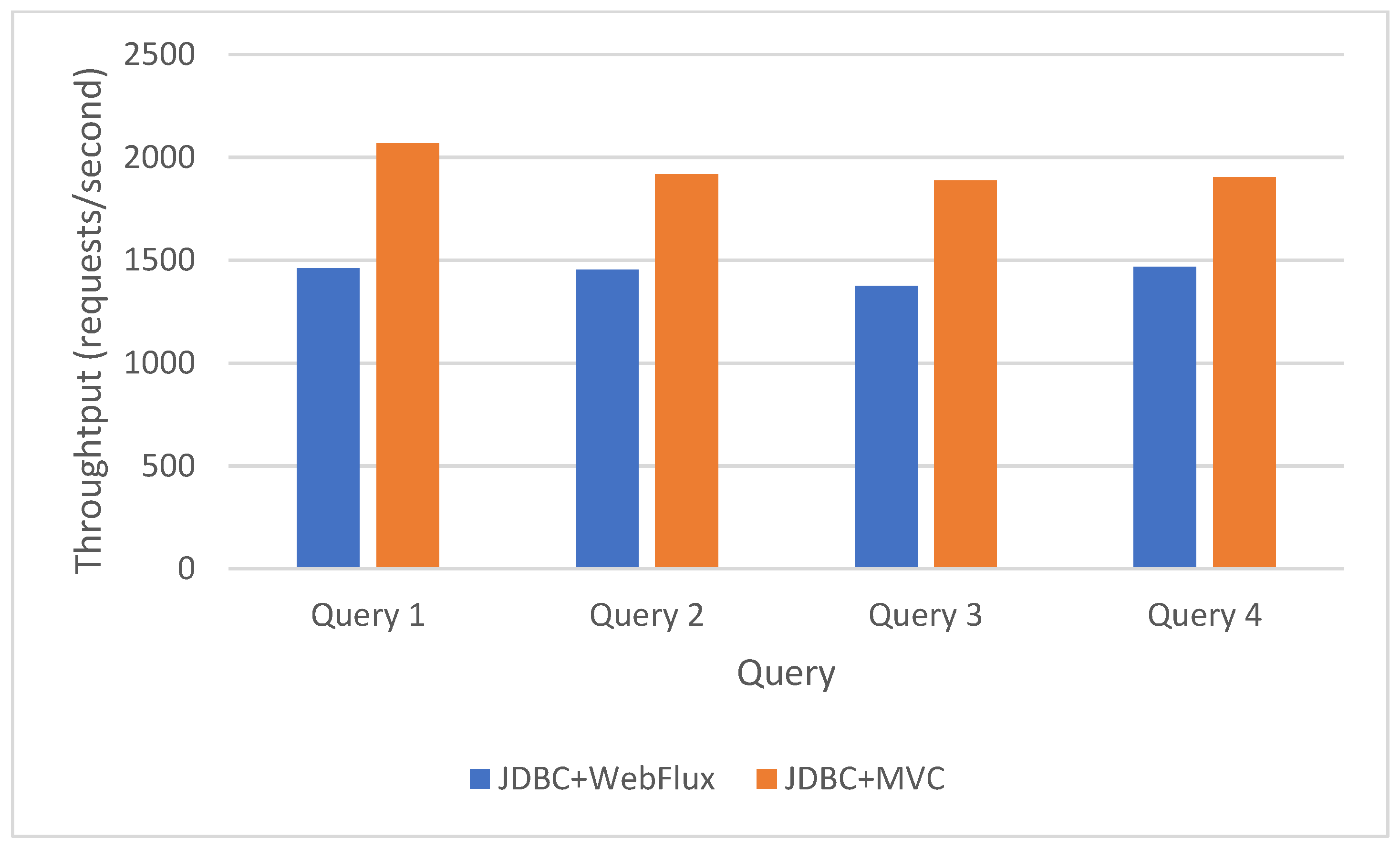

Connecting to the database through JDBC (a synchronous database driver, blocking) will favor choosing to also connect to the Internet synchronously (through the MVC framework), as shown in

Figure 11.

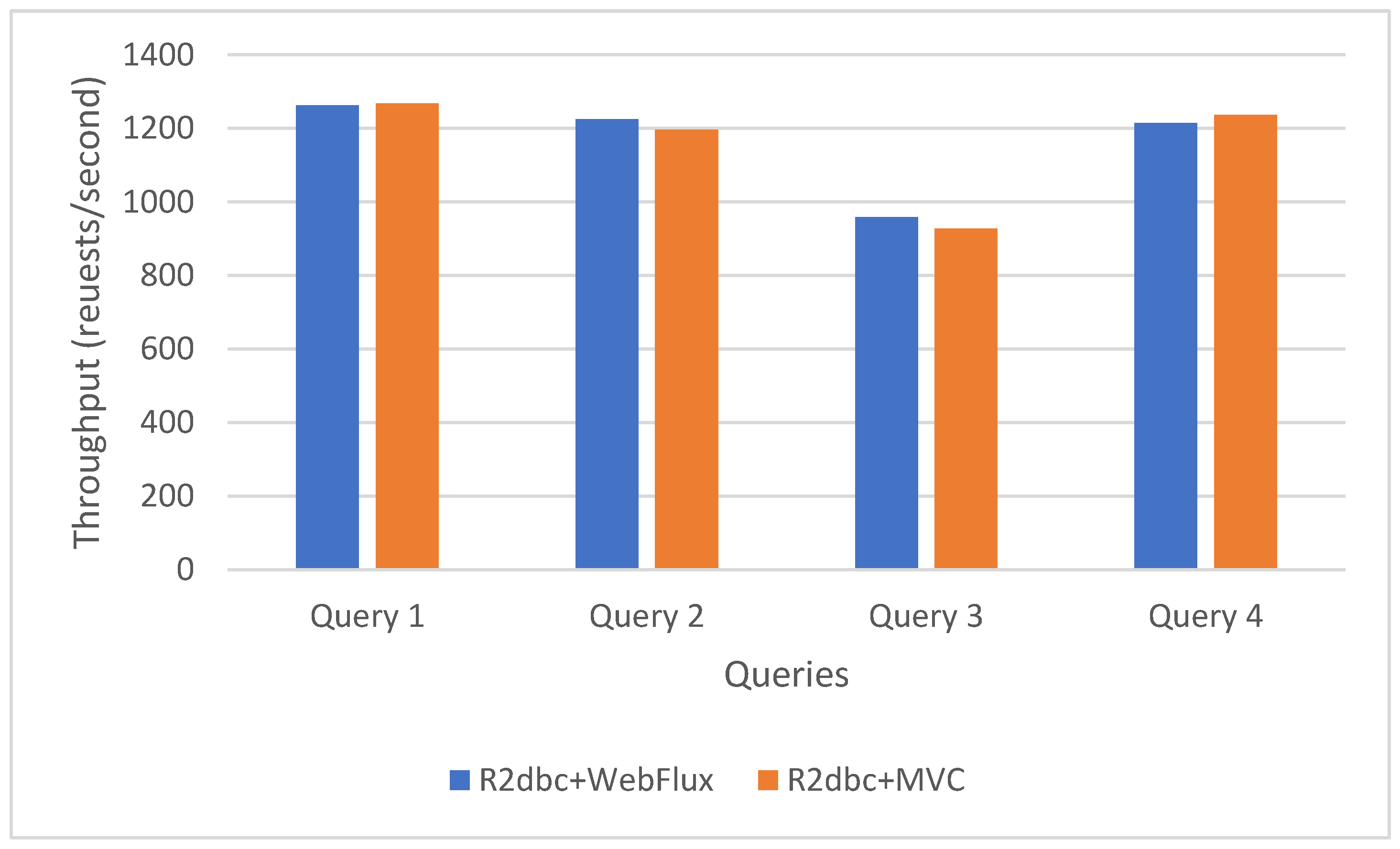

Connecting to the database through a reactive driver mainly favors the usage of a reactive framework for connections to the Web, as shown in

Figure 12.

Comparing the two hybrid approaches, JDBC WebFlux performs better than R2DBC MVC, as demonstrated in

Figure 13.

The synchronous approach has significantly higher throughput than the asynchronous, reactive approach, as shown in

Figure 14.

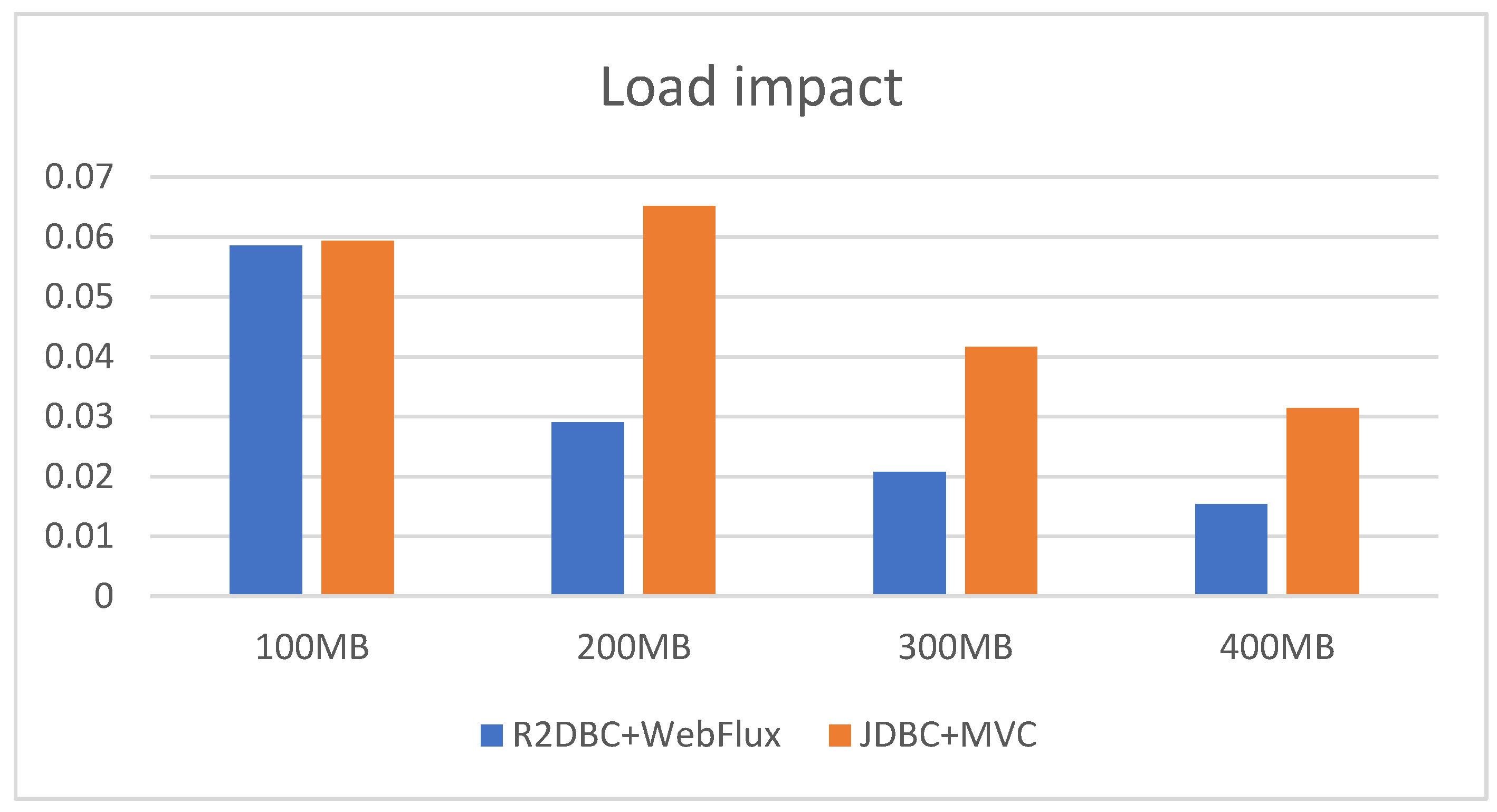

Response Size

One important aspect to study is if the size of the response can impact the performance. The results summarized in

Figure 15 show that, independently of the size of the response, the JDBC MVC (fully synchronous) version is always faster than the R2DBC WebFlux (fully asynchronous) one.

The Oy axis displays the throughput, in requests addressed per second, while the Ox axis displays the size of the answer. The tests implied no concurrent users, only the load was taken into account. 100MB (613202 products) were returned for the first experiment from

Figure 15 for P_R2DBC_WebFlux. Using both REST APIs, the same number of products were requested. The difference was generated because the asynchronous P_R2DBC_WebFlux project does not use JPA, while the synchronous P_JDBC_MVC project uses it. The test was repeatedly executed 10 times, displaying the average in the graphic.

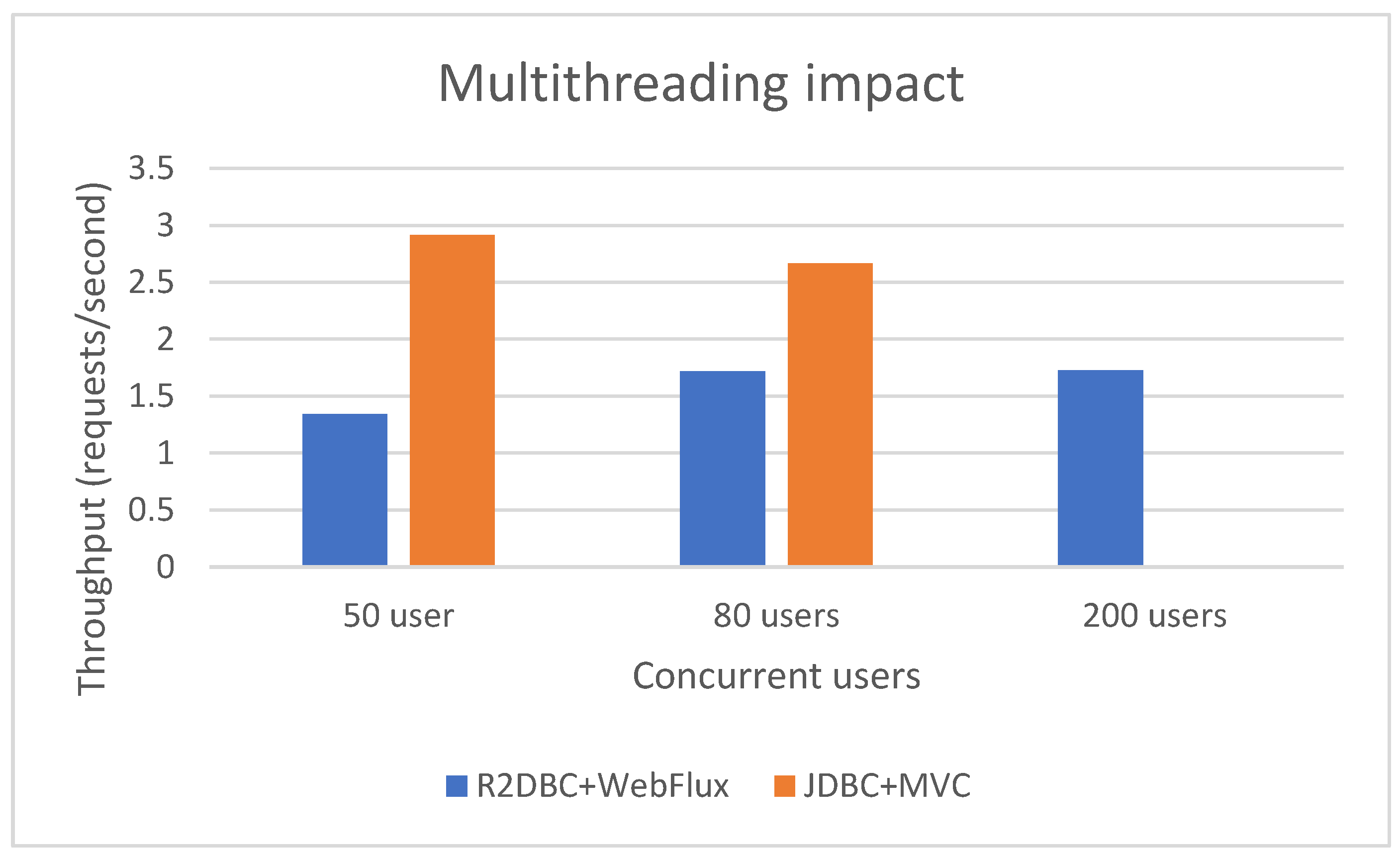

Multithreading Impact

Figure 17 displays on the Oy axis the throughput (in requests addressed per second), while the Ox axis displays the number of concurrent users. While the fully synchronous version is still faster than the fully asynchronous one, it is not scaling out. With 200 concurrent users, the asynchronous solution still works, while the synchronous one is blocked and can no longer respond to the requests. The concurrency was tested with a quite large answer, 10MB for P_R2DBC_WebFlux and a little bit over 20MB for P_JDBC_MVC.

5.3. MVC vs. WebFlux (no database)

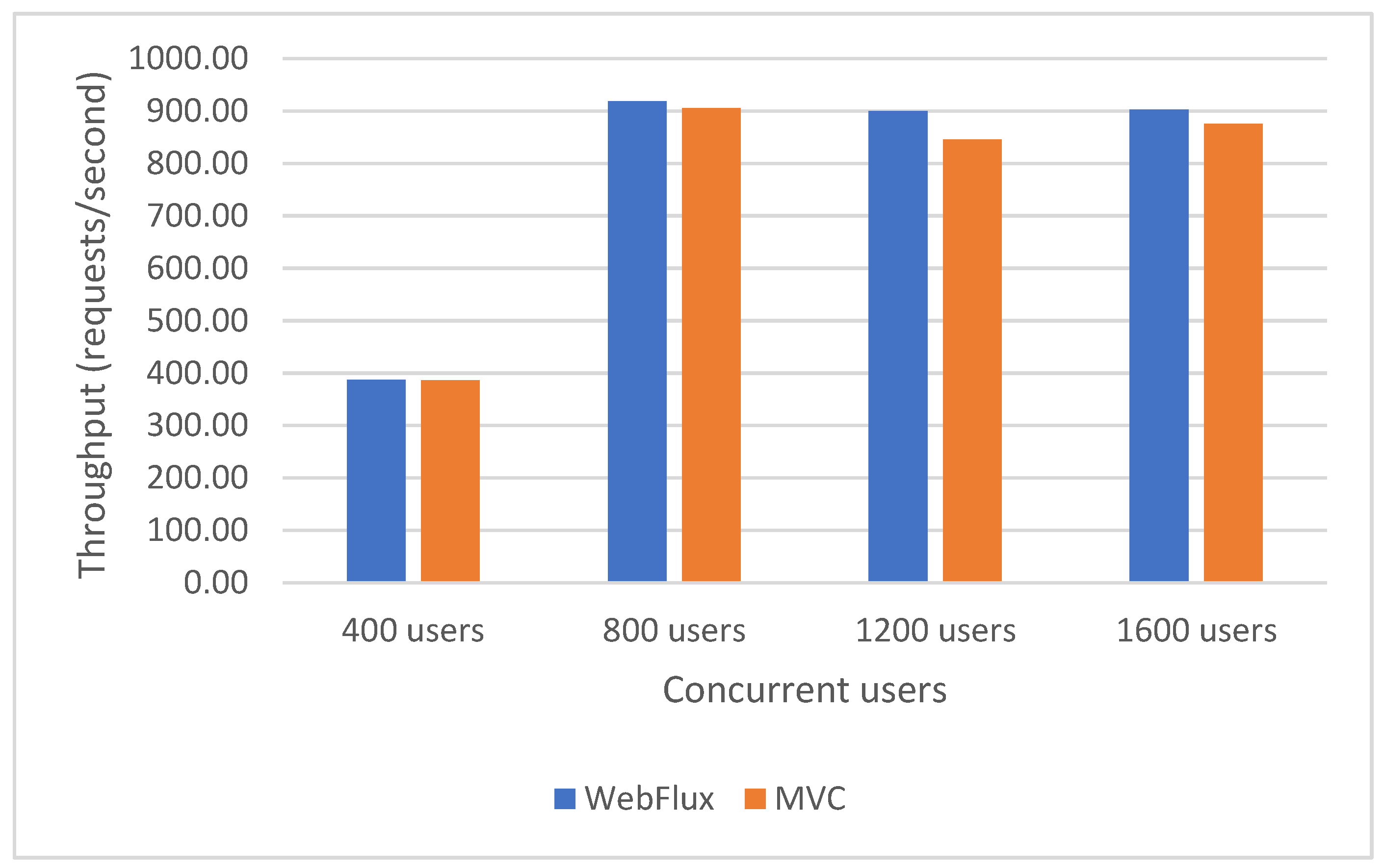

To analyze the results of using asynchronous web frameworks versus synchronous ones, the user interacts with an endpoint that does not extract data from a database. Data is small, less than 1 KB, and it is hardcoded in the Java program so that the test focuses only on the WebFlux or MVC frameworks.

Figure 18 shows that the asynchronous approach has a higher throughput, regardless of the concurrency level.

5.4. Resources Usage

VisualVM [

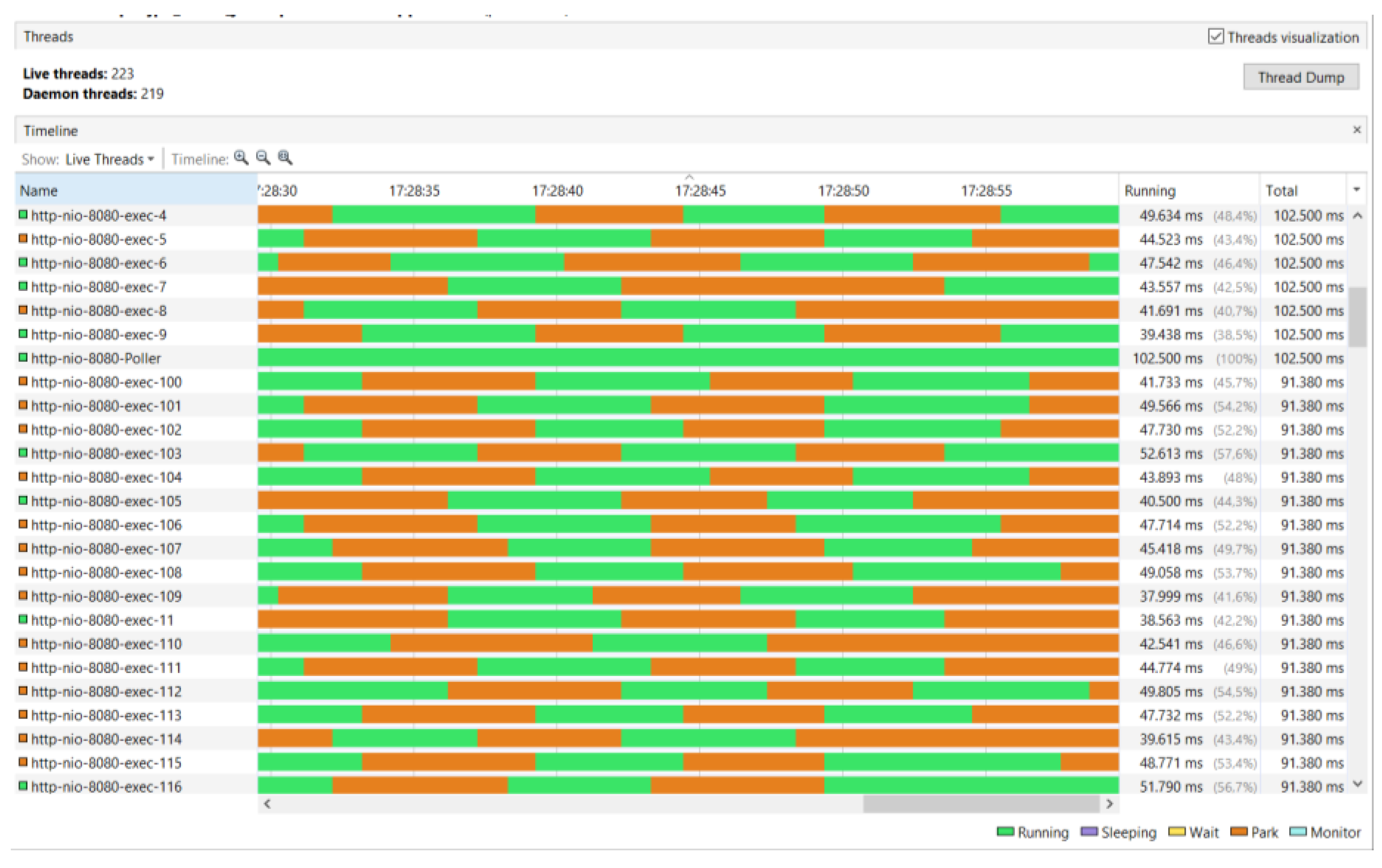

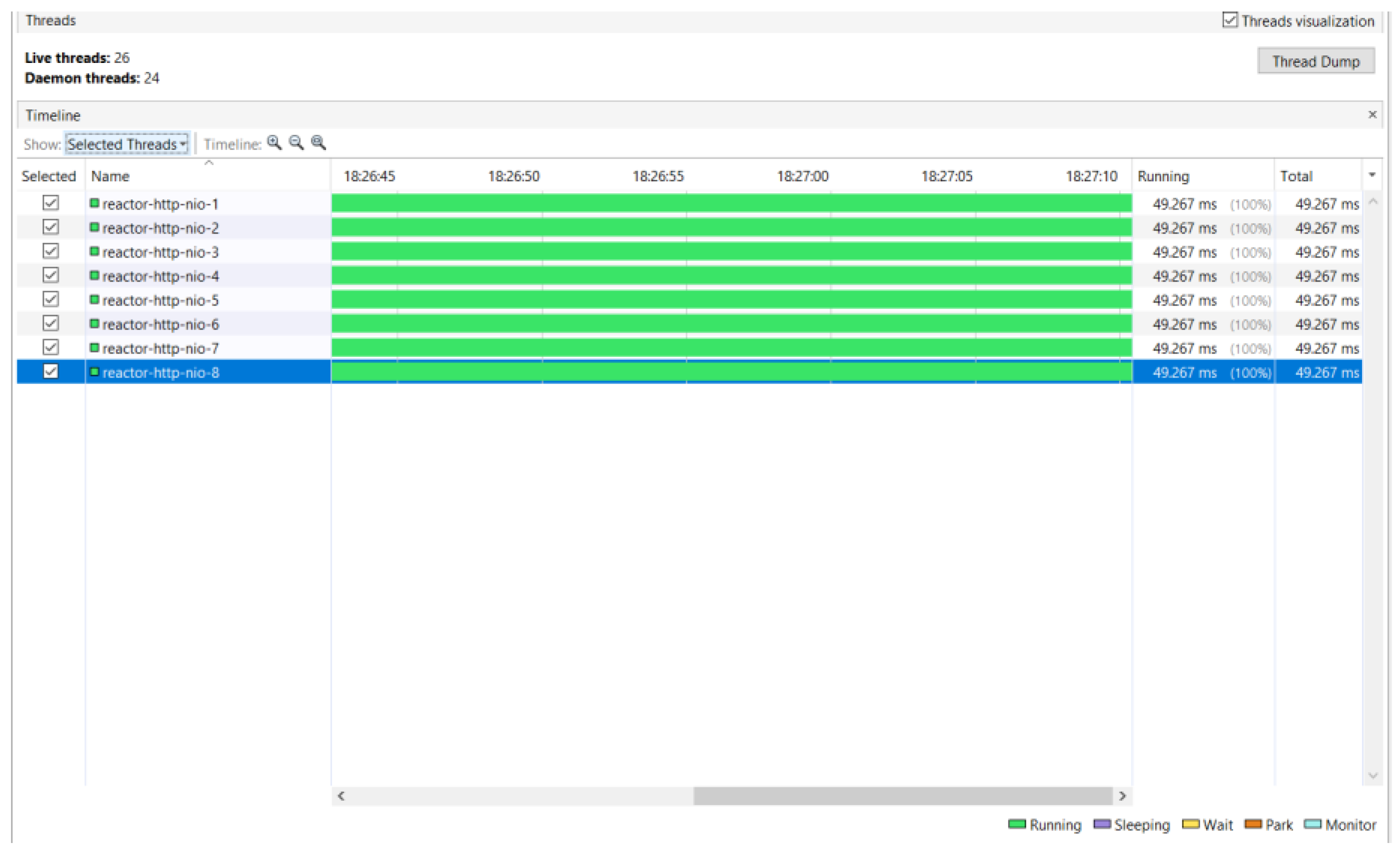

41] was used for analyzing the thread usage. The test simulates 200 users sending the same request, successively. The answer is of average size, there are 10,000 requested products. As displayed in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20, for the interaction between the clients and the project, the fully synchronous approach (JDBC MVC) uses 223 threads, while the fully asynchronous approach (R2DBC WebFlux) uses only 8 threads. The machine used for testing has 4 physical cores and 8 virtual ones, the fully asynchronous approach uses exactly 8 threads. So, the reactive approach uses the resources much more efficiently than the synchronous one.

For the synchronous approach, in

Figure 19, some of the time of each thread is marked as red, representing the blocking state.

Figure 20, representing the usage of the resources for the asynchronous approach, displays only the green color for each thread, representing the running, non-blocking state. However, as the asynchronous approach uses a smaller number of threads, a higher context-switching is also necessary. Unless the number of users is high enough and the size of the answer is large, the synchronous project will outperform the asynchronous one.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Both synchronous and asynchronous approaches offer distinct advantages and limitations. In the experiments, factors such as system load, concurrency, and the complexity or simplicity of the database queries were evaluated to assess performance. Additionally, the analysis included a separate examination of the libraries used for database connectivity in contrast to those used for web handling. This separation allowed for a clearer comparison of each approach’s impact on application performance and scalability.

When factoring in both web handling and database connectivity while adjusting the load, the synchronous approach shows faster results in single-threaded scenarios with no concurrency. However, theoretically, the asynchronous method should excel in handling larger data volumes and higher concurrency levels due to its non-blocking nature.

As the concurrency increases, the synchronous approach still offers better performance until a certain level is achieved. When that level is reached, the synchronous project is blocked and can no longer respond to requests, while the asynchronous one is still running. That means the asynchronous approach is more scalable.

The complexity of the queries does not influence the outcome. The complexity comprises the number of tables being joined, the aggregate functions used, the conditions imposed at the group level, and so on. The synchronous approach is the fastest in almost every case.

Comparing JDBC with R2DBC, it is obvious that, at a smaller concurrency, up to 200 users and a response size under 10MB, the synchronous approach is much faster. The throughput is almost double for the projects that use the synchronous driver, regardless of the web library that is used.

Comparing the MVC with WebFlux, using a list of data that is small and hard-coded so that the database connectivity does not interfere, it is obvious that the asynchronous response is faster. A higher concurrency offers an advantage to WebFlux. MVC uses one thread per connection, while WebFlux uses the same number of threads as the number of logical processors of the machine that the project is running on.

It is worth noticing that MVC uses as server Tomcat version 10 which has non-blocking behavior [

42,

43]. The synchronous version is thus run on top of an application server that supports asynchronous sending of files or data. So for applications made with the latest Spring Boot, it is not possible to make a completely synchronous version, which in itself tells a lot about how important asynchronous programming has become.

The MVC framework in Spring, particularly when deployed with Tomcat 10, benefits from the server’s non-blocking, asynchronous capabilities. This setup allows applications to perform tasks without needing to pause the main execution thread, which is particularly advantageous when handling high-concurrency scenarios. Tomcat 10 supports non-blocking I/O (NIO) for better scalability, allowing it to manage numerous connections.

With Spring Boot’s focus on modern reactive programming, synchronous-only applications become increasingly incompatible with its architecture. The Spring WebFlux framework, introduced as a complement to MVC, is entirely non-blocking, and its integration encourages asynchronous patterns across the entire framework. This approach enables Spring Boot applications to handle larger numbers of requests with lower latency and more efficient resource usage, highlighting the shift towards asynchronous programming as a standard for scalable web development.

These features mean that newer applications built on Spring Boot and Tomcat 10 will inherently adopt asynchronous behaviors, as even MVC’s synchronous processing now leverages asynchronous I/O under the hood, making fully synchronous designs less feasible or efficient. This trend reflects the broader industry shift, where asynchronous design patterns are increasingly prioritized for performance in high-demand applications.

An asynchronous approach offers better scalability for applications that interact with relational databases and serve hundreds of users simultaneously, as it allows for efficient resource management under heavy loads. However, when an application serves only a small number of clients, a synchronous approach can be nearly twice as fast, as it avoids the overhead of managing asynchronous tasks, leading to simpler, more direct processing paths.

In the future, we could adopt a software development methodology [

44], such as Scrum or Kanban, to enable more thorough testing of the synchronous and asynchronous approaches. This strategy would also support faster, more efficient development cycles, leading to improved versions of the web applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and C.T.; formal analysis, M.G. and C.T.; investigation, M.G. and C.T.; methodology, M.G. and C.T.; software, M.G. and C.T.; supervision, C.T.; validation, M.G. and C.T.; writing—original draft, M.G.; writing—review and editing, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Waldrop, M.M. More than Moore, Nature, 2016, 530, 7589, 144+.

- Goetz, B. Java Concurrency In Practice; Pearson India, 2016.

- Abhinav P. Y.; Bhat A.; Joseph C. T.; Chandrasekaran K., Concurrency Analysis of Go and Java, in 5th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Security (ICCCS), Patna, India, 2020.

- Arnold, K.; Gosling, J.; Holmes, D. The Java Programming Language, 4th ed.; Addison-Wesley Professional: Glenview, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, K.; Bates, B.; Gee, T. Head First Java: A Brain-Friendly Guide, 3rd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oracle Thread - Available online: https://docs.oracle.com/en/java/javase/21/docs/api/java.base/java/lang/Thread.html.

- Oracle Runnable - Available online: https://docs.oracle.com/en/java/javase/21/docs/api/java.base/java/lang/Runnable.html.

- Oracle java.util.concurrent, - Available online: https://docs.oracle.com/en/java/javase/21/docs/api/java.base/java/util/concurrent/package-summary.html.

- Oracle Flow - Available online: https://docs.oracle.com/en/java/javase/21/docs/api/java.base/java/util/concurrent/Flow.html.

- Marinescu, D.C. Cloud Infrastructure; Cloud Computing: Theory and Practice, 2013; pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kibe, S.; Watanabe, S.; Kunishima, K.; Adachi, R.; Yamagiwa, M.; Uehara, M., PaaS on IaaS, 2013 IEEE 27th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications (AINA), 2013, 362-367.

- Ju, L.; Yadav, A.; Khan, A.; Sah, A. P.; Yadav, D. Using Asynchronous Frameworks and Database Connection Pools to Enhance Web Application Performance in High-Concurrency Environments 2024 8th International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Kirtipur, Nepal, 2024, 742-747. [CrossRef]

- Catrina, A.V. A Comparative Analysis of Spring MVC and Spring WebFlux in Modern Web Development, 2023, Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/812448/Catrina_Alexandru.pdf?sequence=2.

- Wycislik, L.; Ogorek, L. Issues on Performance of Reactive Programming in the Java Ecosystem with Persistent Data Sources. In: Gruca, A., Czachórski, T., Deorowicz, S., Harężlak, K., Piotrowska, A. (eds) Man-Machine Interactions 6. ICMMI 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 1061. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.; Swamy, S R. Review on Spring Boot and Spring Webflux for Reactive Web Development. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology 2020, 07, 04. [Google Scholar]

- Rankovski, G.; Chorbev, I. Improving Scalability of Web Applications by Utilizing Asynchronous I/O, ICT Innovations 2016. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 2016, 665. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, A.; Huizing, C.; Kuiper, R.; Passier, H.; Pootjes, H.; Smetsers, J., A Structured Design Methodology for Concurrent Programming, in CSERC ’17, Helsinki, Finland, 2017.

- Fowler, M. UML Distilled: A Brief Guide to the Standard Object Modeling Language; Addison-Wesley Professional; 3rd edition, 2003.

- Lee, J.; Fekete, A., Multi-granularity Locking for Nested Transactions, ACTA INFORMATICA, 1996, 33, 2, 131-152.

- Kragl, B.; Qadeer, S.; Henzinger, T. A., Synchronizing the Asynchronous, in 29th International Conference on Concurrency Theory (CONCUR 2018), 2018, 118, 21:1-21:17.

- Smith, P.N.; Guengerich, S.L., Client/Server Computing (Professional Reference Series); SAMS, 1994.

- Saternos, C. Client-Server Web Apps with JavaScript and Java: Rich, Scalable, and RESTful; O’Reilly Media, 2014.

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Kanemasa, Y. Improving Asynchronous Invocation Performance in Client-server Systems, in International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems, 2018.

- Tomcat Documentation - Available online: https://tomcat.apache.org/.

- Jetty Documentation - Available online: https://jetty.org/index.html.

- Glassfish Documentation – Available online: https://glassfish.org/.

- Bradshaw, S.; Brazil, E.; Chodorow, K., MongoDB: The Definitive Guide: Powerful and Scalable Data Storage, O’Reilly Media; 3rd edition, 2019.

- Khalilipour, A.; Challenger, M. Invocations, an Event-based Approach on Automatic Synchronous-to-Asynchronous Transformation of Web Service, in 9th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE 2019), 2019.

- Zhang, S.G.; Wang, Q.Y.; Kanemasa, Y.; Shan, H.S.; Hu, L.T. The Impact of Event Processing Flow on Asynchronous Server Efficiency, IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, 2020, 31, 3, 565-579.

- Bales, D. JDBC Pocket Reference, O’Reilly Media, 2003.

- Harold, E.R. Java I/O: Tips and Techniques for Putting I/O to Work, O’Reilly Media; 2nd edition, 2006.

- Hedgpeth, R. R2DBC Revealed: Reactive Relational Database Connectivity for Java and JVM Programmers, Apress; 1st edition, 2021.

- Chain, R. Mastering Spring MVC: From Novice to Expert Independently published, 2023.

- Millie, K. Reactive programming with Spring WebFlux, Independently published, 2024.

- Ferrari, L.; Pirozzi, E., Learn PostgreSQL: Use, manage and build secure and scalable databases with PostgreSQL 16, 2nd Edition; Packt Publishing; 2023.

- Bonteanu, A.M.; Tudose, C. Performance Analysis and Improvement for CRUD Operations in Relational Databases from Java Programs Using JPA, Hibernate, Spring Data JPA, Applied Sciences – Basel, 2024, 14, 7, 2743.

- Tudose, C. JUnit in Action; Manning: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tudose, C. Java Persistence with Spring Data and Hibernate; Manning: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, R.T. Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures, PhD Thesis, 2000.

- JMeter Documentation - Available online: https://jmeter.apache.org/.

- VisualVM Documentation - Available online: https://visualvm.github.io/.

- Tomcat 10 changelog. Available online: https://tomcat.apache.org/tomcat-10.1-doc/changelog.html#Tomcat_10.1.31_(schultz).

- Advanced IO and Tomcat. Available online: https://tomcat.apache.org/tomcat-10.1-doc/aio.html.

- Anghel, I.I.; Calin, R.S.; Nedelea, M.L.; Stanica, I.C.; Tudose, C.; Boiangiu, C.A. Software development methodologies: A comparative analysis. UPB Sci. Bull. 2022, 83, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The database schema.

Figure 1.

The database schema.

Figure 2.

The results of running the synchronous and asynchronous DDL statements.

Figure 2.

The results of running the synchronous and asynchronous DDL statements.

Figure 3.

The results of running the synchronous and asynchronous DML statements.

Figure 3.

The results of running the synchronous and asynchronous DML statements.

Figure 4.

Asynchronous and synchronous INSERT operations results.

Figure 4.

Asynchronous and synchronous INSERT operations results.

Figure 5.

JDBC WebFlux vs. JDBC MVC simple queries results.

Figure 5.

JDBC WebFlux vs. JDBC MVC simple queries results.

Figure 6.

R2DBC WebFlux vs. R2DBC MVC simple query results.

Figure 6.

R2DBC WebFlux vs. R2DBC MVC simple query results.

Figure 7.

JDBC WebFlux vs R2DBC WebFlux simple queries results.

Figure 7.

JDBC WebFlux vs R2DBC WebFlux simple queries results.

Figure 8.

JDBC MVC vs. R2DBC MVC simple query results.

Figure 8.

JDBC MVC vs. R2DBC MVC simple query results.

Figure 9.

Synchronous (JDBC MVC) vs asynchronous (R2DBC WebFlux) simple queries results.

Figure 9.

Synchronous (JDBC MVC) vs asynchronous (R2DBC WebFlux) simple queries results.

Figure 10.

Direct complex query execution in the context of concurrent access.

Figure 10.

Direct complex query execution in the context of concurrent access.

Figure 11.

JDBC WebFlux vs. JDBC MVC complex queries results.

Figure 11.

JDBC WebFlux vs. JDBC MVC complex queries results.

Figure 12.

R2DBC WebFlux vs. R2DBC MVC complex queries results.

Figure 12.

R2DBC WebFlux vs. R2DBC MVC complex queries results.

Figure 13.

JDBC WebFlux vs. R2DBC MVC (synchronous mixed with asynchronous).

Figure 13.

JDBC WebFlux vs. R2DBC MVC (synchronous mixed with asynchronous).

Figure 14.

Pure synchronous (JDBC MVC) vs. pure asynchronous (R2DBC WebFlux) throughput.

Figure 14.

Pure synchronous (JDBC MVC) vs. pure asynchronous (R2DBC WebFlux) throughput.

Figure 15.

Pure synchronous (JDBC MVC) vs. pure asynchronous (R2DBC WebFlux) load impact.

Figure 15.

Pure synchronous (JDBC MVC) vs. pure asynchronous (R2DBC WebFlux) load impact.

Figure 17.

Throughput by concurrency in synchronous/asynchronous applications.

Figure 17.

Throughput by concurrency in synchronous/asynchronous applications.

Figure 18.

MVC vs. WebFlux (no database).

Figure 18.

MVC vs. WebFlux (no database).

Figure 19.

Resources usage for the fully synchronous approach.

Figure 19.

Resources usage for the fully synchronous approach.

Figure 20.

Resources usage for the fully asynchronous approach.

Figure 20.

Resources usage for the fully asynchronous approach.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).