2. Set Duplicability

In 1878, Cantor proved two instances of

, where ↔ denotes a 1-1 (bijective) function, that is,

, where

is the cardinality of the set

A, such that

, and

is a kind of ordinal number called cardinal number. In the first instance of Cantor’s proofs

, while in the second instance

(the naturals and the reals respectively). These results about cardinal numbers were a shock. In a letter to Richard Dedekind Cantor wrote:

I see it, but I cannot believe it, as reported in Abraham Fränkel’s book [

8].

According to Cantor, a set is infinite if it includes a subset that is equipotent (1-1), with the set of natural numbers.

The bijection

means that the set

A is

Cartesian Duplicable. The general proof that, for every infinite set

A,

requires the Axion of Choice AC [

8]. Moreover, Tarski showed in 1924 [

10] that “

for any infinite

A” is equivalent to the Axiom of Choice AC.

Informally, the axiom of choice says that for any collection of nonempty sets, it is possible to construct a new set by choosing one element from each set (even if the collection is infinite). An equivalent formulation says that the Cartesian product of a collection of non-empty sets is non-empty. Many important results in set theory need AC to be proved. Axiomatic set theories, such as ZF (Zermelo Fränkel), establish axioms expressing the essence of sets, but avoiding the paradoxes arising when a naive notion of class is assumed, such as Russell’s paradox reported in 1902. The theory ZFC is the ZF theory with the Axiom of Choice.

Dedekind’s infinity DI of a set A claims that ( denotes an injective and not surjective function).

A set is (simply)

Duplicable if

, that is, if

with

both bijective with

A. Dedekind Infinity implies Cantor’s infinity. If AC is assumed, set infinity is equivalent to Dedekind infinity. [

4,

5,

7,

10,

11]. It was proved that set duplicability is weaker than AC [

7].

Lemma 1 (Cartesian Duplicability implies Duplicability)

If A is a Cartesian duplicable set, it is a sum duplicable set.

Proof. If

A is Cartesian duplicable, then:

and the following chain of bijective functions holds:

where

and

(

A includes a set bijective to

and

can be set as the element of this set corresponding to 0), then:

. if

then

that is:

Therefore, by (

2) the thesis follows. □

According to John von Neumann [

4,

5],

an ordinal number is the set of numbers preceding it. Therefore, the first ordinal number is

∅, the second one is

, the third is

, and in general the successor of an ordinal

is

. The union of all finite ordinals is

, the first infinite ordinal. Then, the successor of

is

, therefore, the usual counting process of numbers can be extended to all transfinite numbers. Surprisingly, Cantor’s transfinite counting is strongly related to Archimedes’ counting process based on orders and periods [

6].

Now, we give two different proofs of set duplicability. The first one uses AC; the other one does not use AC.

Lemma 2 (Set Infinity implies Set Duplicability)

Any infinite set A is duplicable, that is, it is equipotent to the union of two disjoint sets and that are both equipotent to A.

Proof 1. It is well-known that AC implies that any set is well-ordered, that is, it is 1-1 with some ordinal . But . This can be shown in several ways, for example by using an argument similar to Cantor’s proof that (). □

Proof 2. The infinity of A implies that, for any , surely there exists a subset that is a bijective image of a function f from to with . At this point, i) we mark a by 0, by replacing it with , and ii) if , we add the pair to a function g initially equal to ∅. We continue to repeat this procedure. Hence, the process goes on, step by step, by applying substeps i) and ii) for all unmarked elements present in A at that step (for infinite steps, they are an infinite set). The set of all 0-marked elements is bijective with the set of their images according to g, and the initial set A is 1-1 with . □.

Lemma 3 (Set Duplicability implies Set Infinity)

A duplicable set is infinite.

Proof. If a set is finite, it cannot be duplicable. This means, by contraposition, that a duplicable set has to be infinite. □

The second proof of the Lemma 2 can be extended to prove that, given an infinite set

A and a family of finite sets

, then

. But a stronger result holds, because even when

, for every

, then

(in this case AC seems to be essential in the proof). However, if we consider the ordinal numbers having a cardinality less than or equal to a cardinal number

, then

. The ordinal

is an

initial ordinal, and corresponds to the cardinal number

. Cantors’s Continuum Hypothesis CH claims that

, and a crucial result of the last century, solving the 23

o Hilbert Problem presented in 1900, shows that there are models of sets where CH holds and models where CH does not hold [

2].

The previous two lemmas show that the infinity of sets is equivalent to their duplicability. The same equivalence does not hold between infinity and Dedekind infinity. Namely, if a set is finite, it cannot be Dedekind infinite. Therefore, when a set is Dedekind infinite it has to be infinite. But non necessarily infinite sets are also Dedekind infinite because there exist models of ZF where there are sets infinite that are not Dedekind infinite, called iDf (infinite Dedekind finite).

Lemma 4 Given two sets if is 1-1 with a proper part of X, then .

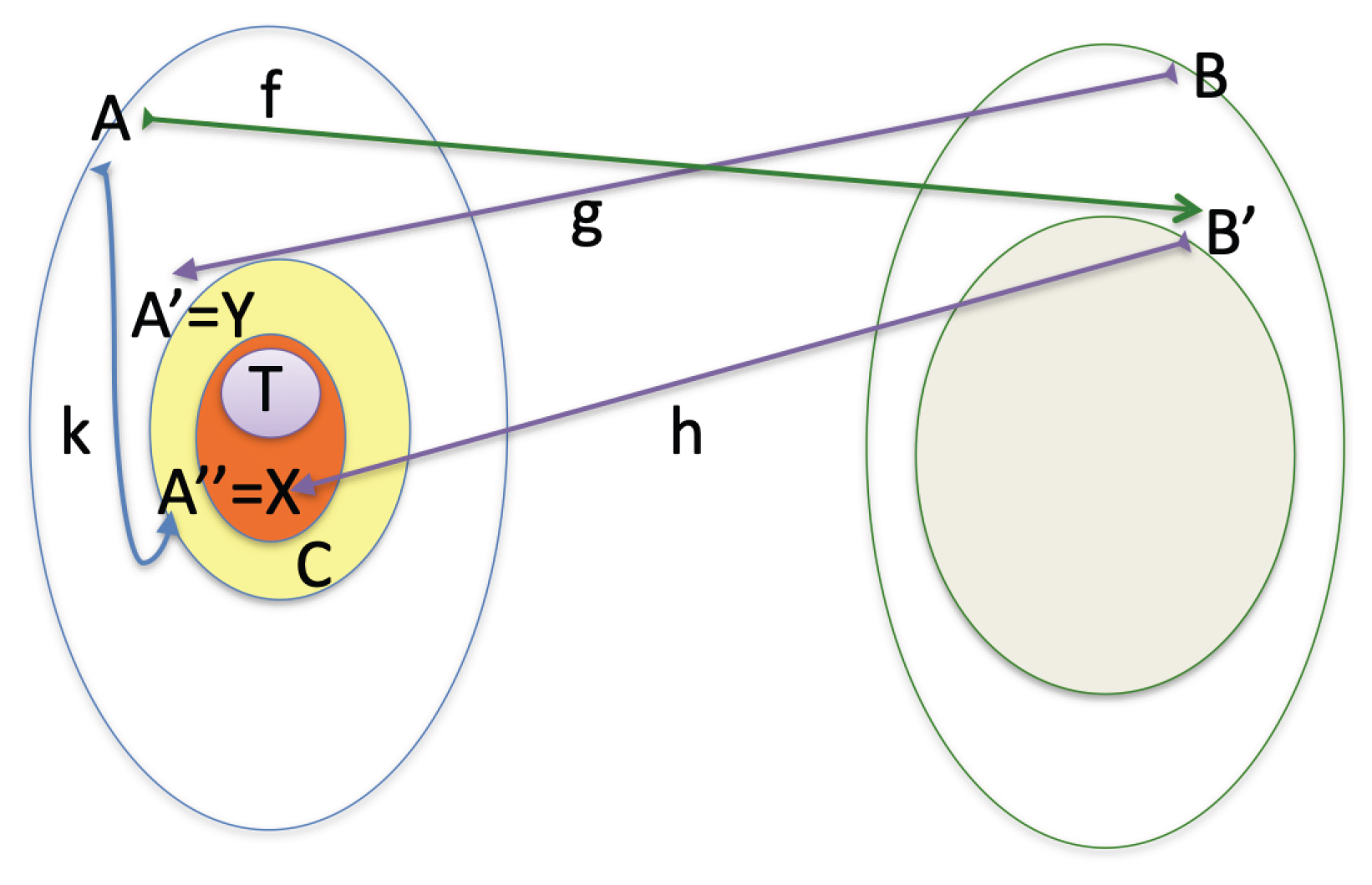

Proof. Let us denote by

C the difference

and by

T its image in

X such that

(see

Figure 1). At first glance, a 1-1 correspondence could be obtained by the union of the correspondence

plus the identical correspondence

. However, this is not the correct way to establish a correspondence

. Namely,

T (and any subset of

X) has to be considered twice: when it is a subset of

X and when it is a subset of

Y and in the previous wrong solution

T as a subset of

Y remains uncovered by the correspondence. For this reason, set duplicability is essential to give the right 1-to-1 correspondence between

X and

Y. Let us suppose that

T is infinite (otherwise the proof is trivial). For a better explanation let us denote by a superscript the superset where a set is considered. Now, by the Lemma 2, the set

is bijective with the union of two disjoint sets

that are both 1-to-1 with

. Then

X is 1-to-1 with

Y as the union of the following three correspondences:

. □

The following Proposition will prove Schröder-Bernstein Theorem, shortly SBT, from the duplicability of infinite sets. A classical proof of SBT can be found in [

3], and historical accounts of SBT are given in [

9,

12]. Given two sets

, then

means that there exists an injective function from

A to

B, while

means that

. If

and a 1-1 function from

A to

B exists, then

.

Proposition 4 (Cantor-Schröder-Bernstein Theorem)

If and , then .

Proof. The following bijections derive from the hypothesis (see

Figure 1,

):

1)

2)

3)

4) .

From 4) it follows that has to be bijective (in the correspondence k) with some subset T of . Therefore, we can apply Lemma 4 where and , from which the following correspondences follows:

5) . Then, from 2) and 5) we get the conclusion . □

The first proof of SBT was given in 1887 by Dedekind [

12], who did not publish it. This proof and a second proof given by Dedekind in 1897 do not use AC, but both use the

Dedekind Lemma [

9]:

and

implies |

. This Lemma easily follows from Lemma 3 given above.