Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

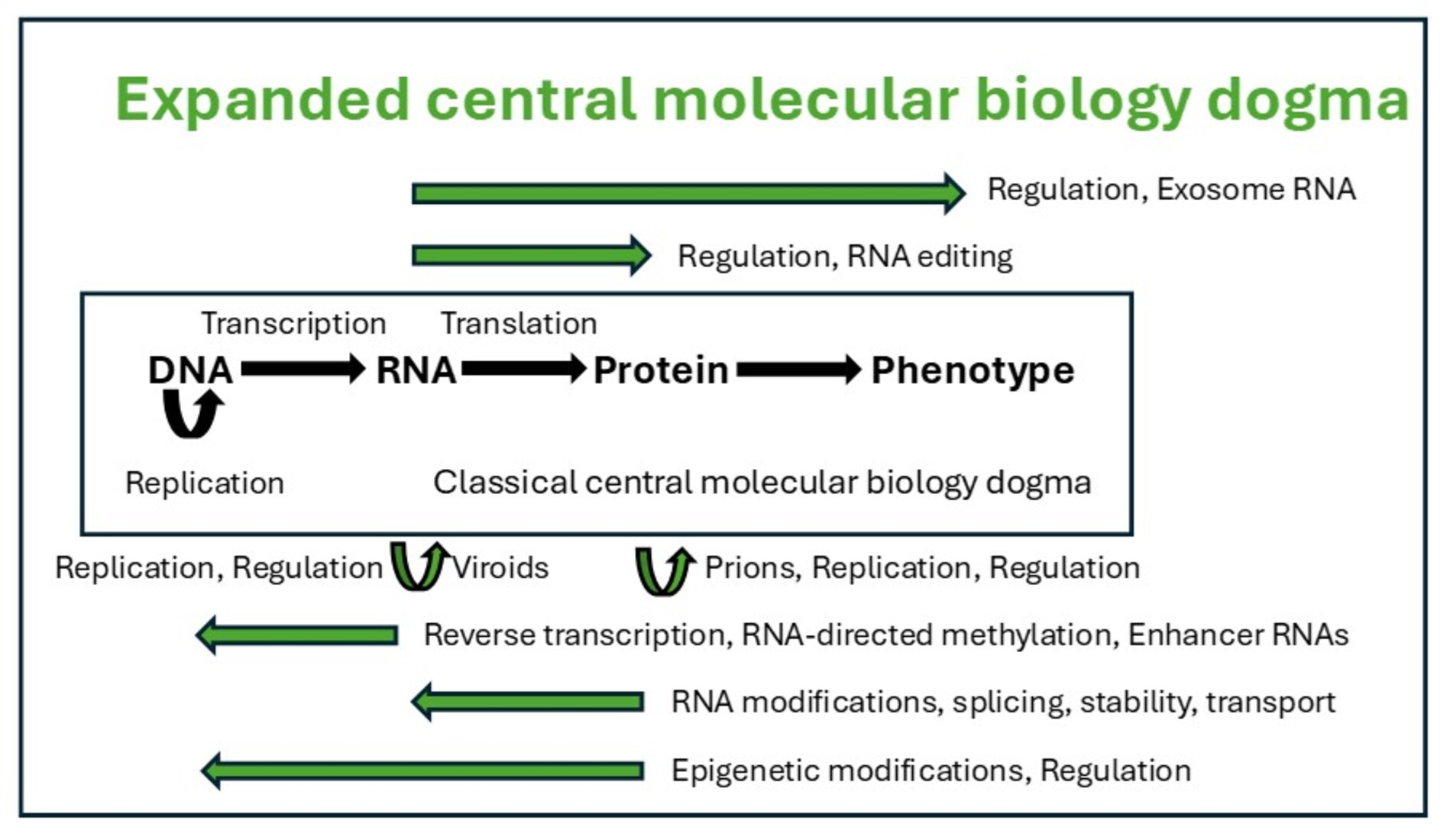

1. The Classical Central Molecular Biology Dogma

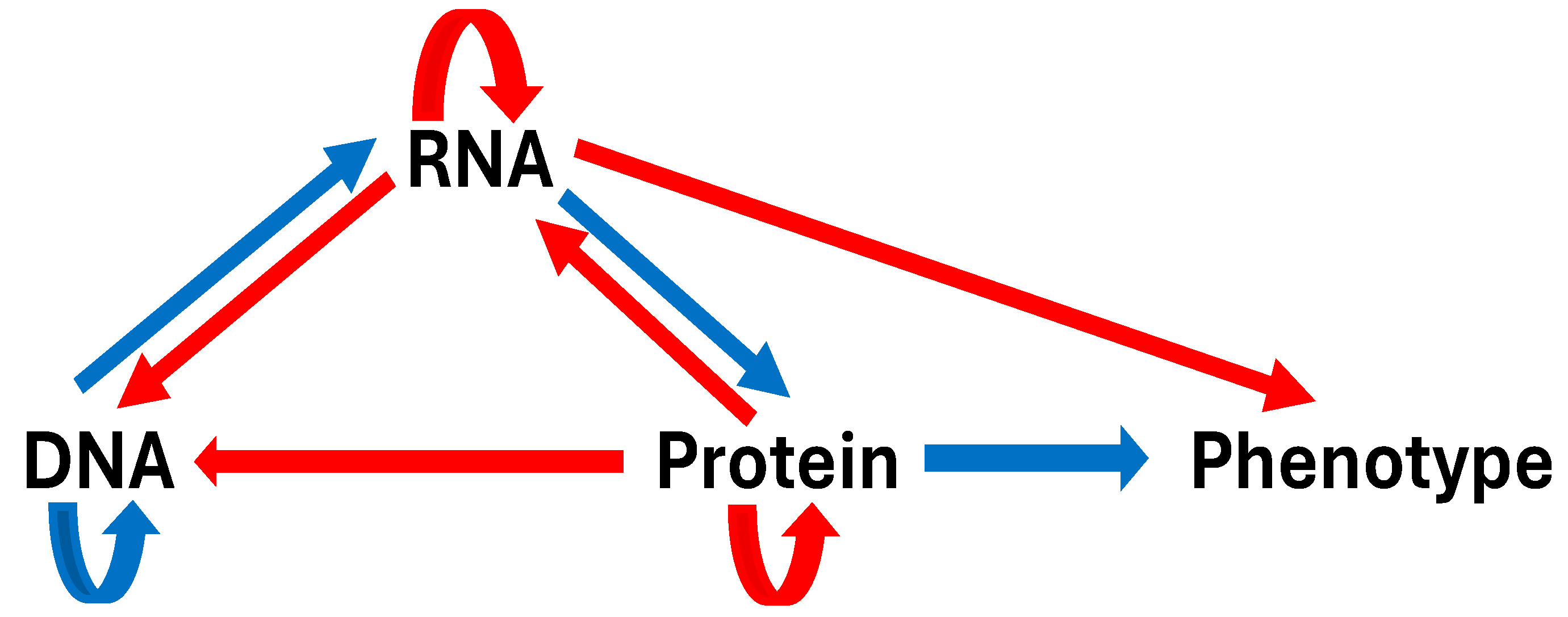

2. The Flow of Genetic Information Is Not Solely Colinear and Irreversible from DNA-to-RNA-to-Protein-to-Phenotype

2.1. RNA Can Store Vertically Transmitted Genetic Information and Serve as a Template to Generate DNA

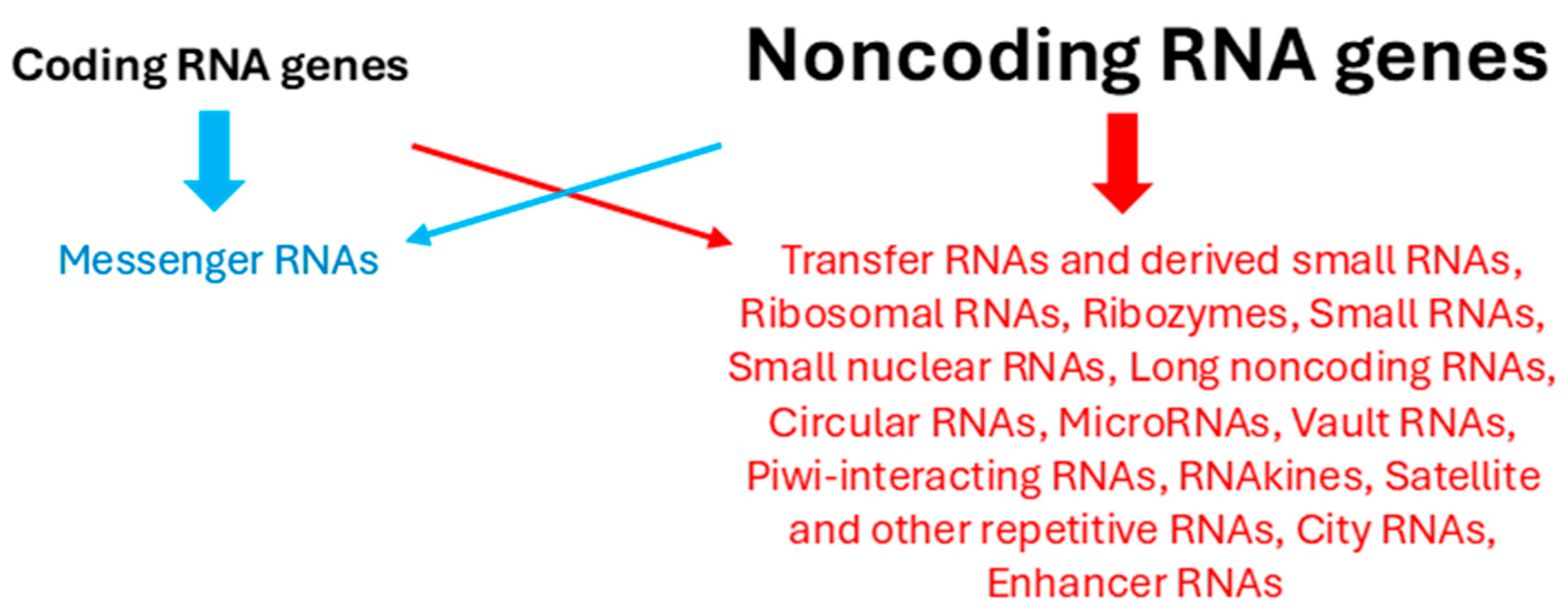

2.2. Most RNAs Do Not Encode Proteins

2.3. Biological Diversity Primarily Results from RNA Generation, Processing, and Regulation Complexities

2.3.1. Alternative Splicing

2.3.2. Alternative Polyadenylation

2.3.3. Regulatory RNA-Binding Proteins

2.3.4. Formation of Ribonucleoprotein Complexes

2.3.5. Formation of Biomolecular Condensates Through Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation

2.3.6. RNA Modifications

2.3.7. Regulatory RNAs or Riboregulators

2.3.8. RNA Stability

2.4. RNA Can Guide Other Molecules that Modify DNA, Regulating Gene Expression

2.5. RNA Can Directly Affect Extracellular Biology and Pathology

2.5.1. GlycoRNAs

2.5.2. RNAs Can Be Transferred Intra- and Inter-Species in Extracellular Vesicles

2.6. Prions Are Infectious Proteins that Transmit Genetic Information Without DNA Mediation

2.7. Proteins Can Regulate DNA Gene Expression via Transcription Factors and Histone Modification, Underlying Epigenetic Inheritance Beyond Genomic DNA Inheritance

2.8. Genetic Mosaicism

3. One Gene Can Encode Multiple Proteins and Noncoding RNAs

3.1. Splicing

3.2. Translation from Noncanonical Open Reading Frames or Generation from Noncoding RNAs

3.3. Stop Codon Readthrough

3.4. Generation of Microproteins or Short Bioactive Peptides

3.5. Overlapping Reading Frames or Genes

3.6. RNA Processing and Modification, Including Editing

3.7. Protein Modification

3.8. Antisense Strand Transcription

4. The Expanded Central Molecular Biology Dogma Reflects the Interrelatedness of All Biomolecules and Phenotype

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smýkal, P., K Varshney, R., K Singh, V., Coyne, C.J., Domoney, C., Kejnovský, E., Warkentin, T. From Mendel's discovery on pea to today's plant genetics and breeding : Commemorating the 150th anniversary of the reading of Mendel's discovery. Theor Appl Genet 2016, 129, 2267-2280. [CrossRef]

- Luria, S.E. Genetics of bacteriophage. Annu Rev Microbiol 1962, 16, 205-240. [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.H. On protein synthesis. Symp Soc Exp Biol 1958, 12, 138-163.

- Crick, F.H. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol 1968, 38, 367-379. [CrossRef]

- Crick, F. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 1970, 227, 561-563. [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.H., Barnett, L., Brenner, S., Watts-Tobin, R.J. General nature of the genetic code for proteins. Nature 1961, 192, 1227-1232. [CrossRef]

- Jain, N., Blauch, L.R., Szymanski, M.R., Das, R., Tang, S.K.Y., Yin, Y.W., Fire, A.Z. Transcription polymerase-catalyzed emergence of novel RNA replicons. Science 2020, 368, eaay0688. [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, E.K., Kao, C.C. Analysis of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase structure and function as guided by known polymerase structures and computer predictions of secondary structure. Virology 1998, 252, 287-303. [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T., Dos Santos Junior, A.P., Rêgo, T.G., José, M.V. Origin and Evolution of RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. Front Genet 2017, 8, 125. [CrossRef]

- Baltimore, D. RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of RNA tumour viruses. Nature 1970, 226, 1209–1211.

- Temin, H.M., Mizutani, S. RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of Rous sarcoma virus. Nature 1970, 226, 1211–1213.

- Wilkinson, M.E., Li, D., Gao, A., Macrae, R.K., Zhang, F. Phage-triggered reverse transcription assembles a toxic repetitive gene from a noncoding RNA. Science 2024, 386, eadq3977. [CrossRef]

- Ivancevic, A., Simpson, D.M., Joyner, O.M., Bagby, S.M., Nguyen, L.L., Bitler, B.G., Pitts, T.M., Chuong, E.B. Endogenous retroviruses mediate transcriptional rewiring in response to oncogenic signaling in colorectal cancer. Sci Adv 2024, 10, :eado1218. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Lu, X., Zhang, W., Liu, G.H. Endogenous retroviruses in development and health. Trends Microbiol 2024, 32, 342-354. [CrossRef]

- Diener, T.O. Viroids. Adv Virus Res 1972, 17, 295-313. [CrossRef]

- Symons, R.H., Randles, J.W. Encapsidated circular viroid-like satellite RNAs (virusoids) of plants. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1999, 239, 81-105. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.M. Hepatitis D Virus Replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 5, a021568. [CrossRef]

- Assmann, S.M., Chou, H.L., Bevilacqua, P.C. Rock, scissors, paper: How RNA structure informs function. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1671-1707. [CrossRef]

- Eisfeldt, J., Ameur, A., Lenner, F., Ten Berk de Boer, E., Ek, M., Wincent, J., Vaz, R., Ottosson, J., Jonson, T., Ivarsson, S., Thunström, S., Topa, A., Stenberg, S., Rohlin, A., Sandestig, A., Nordling, M., Palmebäck, P., Burstedt, M., Nordin, F., Stattin, E.L., Sobol, M., Baliakas, P., Bondeson, M.L., Höijer, I., Saether, K.B., Lovmar, L., Ehrencrona, H., Melin, M., Feuk, L., Lindstrand, A. A national long-read sequencing study on chromosomal rearrangements uncovers hidden complexities. Genome Res 2024, Oct 29. [CrossRef]

- Mathews, D.H. Using an RNA secondary structure partition function to determine confidence in base pairs predicted by free energy minimization. RNA 2004, 10, 1178–1190. [CrossRef]

- Luttermann, C., Meyers, G. A bipartite sequence motif induces translation reinitiation in feline calicivirus RNA. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 7056-7065. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., Tang, Y., Kwok, C.K., Zhang, Y., Bevilacqua, P.C., Assmann, S.M. In vivo genome-wide profiling of RNA secondary structure reveals novel regulatory features. Nature 2014, 505, 696-700. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.J., Roche, J., Moss, W.N. Scanfold: an approach for genome-wide discovery of local RNA structural elements-applications to Zika virus and HIV. PeerJ 2018, 6, e6136. [CrossRef]

- Spasic, A., Assmann, S.M., Bevilacqua, P.C., Mathews, D.H. Modeling RNA secondary structure folding ensembles using SHAPE mapping data. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, 314–323. [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, Z.A., Kieft, J.S. Viral RNA structure-based strategies to manipulate translation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17, 110-123. [CrossRef]

- Vicens, Q., Kieft, J.S. Thoughts on how to think (and talk) about RNA structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2112677119. [CrossRef]

- Sherlock, M.E., Baquero Galvis, L., Vicens, Q., Kieft, J.S., Jagannathan, S. Principles, mechanisms, and biological implications of translation termination-reinitiation. RNA 2023, 29, 865-884. [CrossRef]

- Khan, D., Fox, P.L. Host-like RNA Elements Regulate Virus Translation. Viruses 2024, 16, 468. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S., Conte, V., Zhang, D.J., Žedaveinytė, R., Lampe, G.D., Wiegand, T., Tang, L.C., Wang, M., Walker, M.W.G., George, J.T., Berchowitz, L.E., Jovanovic, M., Sternberg, S.H. De novo gene synthesis by an antiviral reverse transcriptase. Science 2024, Aug 8, eadq0876. [CrossRef]

- Rusk, N. Understanding noncoding RNAs. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 35. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, P.P., Mattick, J.S. Noncoding RNA in development. Mamm Genome 2008, 19, 454-492. [CrossRef]

- Joglekar, A., Hu, W., Zhang, B., Narykov, O., Diekhans, M., Marrocco, J., Balacco, J., Ndhlovu, L.C., Milner, T.A., Fedrigo, O., Jarvis, E.D., Sheynkman, G., Korkin, D., Ross, M.E., Tilgner, H.U. Single-cell long-read sequencing-based mapping reveals specialized splicing patterns in developing and adult mouse and human brain. Nat Neurosci 2024, 27, 1051-1063. [CrossRef]

- Seitz, E.E., McCandlish, D.M., Kinney, J.B. et al. Interpreting cis-regulatory mechanisms from genomic deep neural networks using surrogate models. Nat Mach Intell 2024, 6, 701–713. [CrossRef]

- Merkin, J., Russell, C., Chen, P., Burge, C.B. Evolutionary dynamics of gene and isoform regulation in Mammalian tissues. Science 2012, 338, 1593-1599. [CrossRef]

- Furlanis, E., Scheiffele, P. Regulation of Neuronal Differentiation, Function, and Plasticity by Alternative Splicing. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2018, 34, 451-469. [CrossRef]

- Șelaru, A., Costache, M., Dinescu, S. Epitranscriptomic signatures in stem cell differentiation to the neuronal lineage. RNA Biol 2021, 18, 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Zhang, T., Yu, Z., Tan, W.T., Wen, M., Shen, Y., Lambert, F.R.P., Huber, R.G., Wan, Y. Genome-wide RNA structure changes during human neurogenesis modulate gene regulatory networks. Mol Cell 2021, 81, 4942-4953.e8. [CrossRef]

- Patowary, A., Zhang, P., Jops, C., Vuong, C.K., Ge, X., Hou, K., Kim, M., Gong, N., Margolis, M., Vo, D., Wang, X., Liu, C., Pasaniuc, B., Li, J.J., Gandal, M.J., de la Torre-Ubieta, L. Developmental isoform diversity in the human neocortex informs neuropsychiatric risk mechanisms. Science 2024, 384, eadh7688. [CrossRef]

- Joglekar, A., Hu, W., Zhang, B., Narykov, O., Diekhans, M., Marrocco, J., Balacco, J., Ndhlovu, L.C., Milner, T.A., Fedrigo, O., Jarvis, E.D., Sheynkman,, G., Korkin, D., Ross, M.E., Tilgner, H.U. Single-cell long-read sequencing-based mapping reveals specialized splicing patterns in developing and adult mouse and human brain. Nat Neurosci 2024, 27, 1051-1063. [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H., Miller, C.M., Ettinger, C.R., Belkina, A.C., Snyder-Cappione, J.E., Gummuluru, S. HIV-1 intron-containing RNA expression induces innate immune activation and T cell dysfunction. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3450. [CrossRef]

- Guney, M.H., Nagalekshmi, K., McCauley, S.M., Carbone, C., Aydemir, O., Luban, J. IFIH1 (MDA5) is required for innate immune detection of intron-containing RNA expressed from the HIV-1 provirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2404349121. [CrossRef]

- Foord, C., Hsu, J., Jarroux, J., Hu, W., Belchikov, N., Pollard, S., He, Y., Joglekar, A., Tilgner, H.U. The variables on RNA molecules: concert or cacophony? Answers in long-read sequencing. Nat Methods 2023, 20, 20-24. [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, F., Schwarzl, T., Valcárcel, J., Hentze, M.W. RNA-binding proteins in human genetic disease. Nat Rev Genet 2021, 22, 185-198. [CrossRef]

- Hentze, M.W., Castello, A., Schwarzl, T., Preiss, T. A brave new world of RNA-binding proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 327-341. [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J., Amaral, P. RNA, the Epicenter of Genetic Information: A new understanding of molecular biology. Abingdon (UK): CRC Press; 2022 Sep 20. Chapter 16, RNA Rules. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK595927/ https://doi.org10.1201/9781003109242-16.

- Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., Tan, W.T., Lambert, F., Darmawan, J., Huber, R., Wan, Y. RNA structure profiling at single-cell resolution reveals new determinants of cell identity. Nat Methods 2024, 21, 411-422. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wang, Y., Tan, Y.Q., Yue, Q., Guo, Y., Yan, R., Meng, L., Zhai, H., Tong, L., Yuan, Z., Li, W., Wang, C., Han, S., Ren, S., Yan, Y., Wang, W., Gao, L., Tan, C., Hu, T., Zhang, H., Liu, L., Yang, P., Jiang, W., Ye, Y., Tan, H., Wang, Y., Lu, C., Li, X., Xie, J., Yuan, G., Cui, Y., Shen, B., Wang, C., Guan, Y., Li, W., Shi, Q., Lin, G., Ni, T., Sun, Z., Ye, L., Vourekas, A., Guo, X., Lin, M., Zheng, K. The landscape of RNA binding proteins in mammalian spermatogenesis. Science 2024, 386, eadj8172. [CrossRef]

- Blaise, M., Bailly, M., Frechin, M., Behrens, M.A., Fischer, F., Oliveira, C.L., Becker, H.D., Pedersen, J.S., Thirup, S., Kern, D. Crystal structure of a transfer-ribonucleoprotein particle that promotes asparagine formation. EMBO J 2010, 29, 3118-329. [CrossRef]

- Briata, P., Gherzi, R. Long Non-Coding RNA-Ribonucleoprotein Networks in the Post-Transcriptional Control of Gene Expression. Noncoding RNA 2020, 6, 40. [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.R., Zabezhinsky, D., Gelin-Licht, R., Haas, B.J., Dyhr, M.C., Sperber, H.S., Nusbaum, C., Gerst, J.E. Multiplexed mRNA assembly into ribonucleoprotein particles plays an operon-like role in the control of yeast cell physiology. Elife 2021, 10, e66050. [CrossRef]

- Hollin, T., Abel, S., Banks, C., Hristov, B., Prudhomme, J., Hales, K., Florens, L., Stafford Noble, W., Le Roch, K.G. Proteome-Wide Identification of RNA-dependent proteins and an emerging role for RNAs in Plasmodium falciparum protein complexes. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1365. [CrossRef]

- Bleichert, F., Baserga, S.J. Ribonucleoprotein multimers and their functions. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2010, 45, 331-350. [CrossRef]

- Geuens, T., Bouhy, D., Timmerman, V. The hnRNP family: insights into their role in health and disease. Hum Genet 2016, 135, 851-867. [CrossRef]

- Bhola, M., Abe, K., Orozco, P., Rahnamoun, H., Avila-Lopez, P., Taylor, E., Muhammad, N., Liu, B., Patel, P., Marko, J.F., Starner, A.C., He, C., Van Nostrand, E.L., Mondragón, A., Lauberth, S.M. RNA interacts with topoisomerase I to adjust DNA topology. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 3192-3208.e11. https://doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2024.07.032.

- Zarnack, K., Balasubramanian, S., Gantier, M.P., Kunetsky, V., Kracht, M., Schmitz, M.L., Sträßer, K. Dynamic mRNP Remodeling in Response to Internal and External Stimuli. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1310. [CrossRef]

- Scott-Hewitt, N., Mahoney, M., Huang, Y., Korte, N., Yvanka de Soysa, T., Wilton, D.K., Knorr, E., Mastro, K., Chang, A., Zhang, A., Melville, D., Schenone, M., Hartigan, C., Stevens, B. Microglial-derived C1q integrates into neuronal ribonucleoprotein complexes and impacts protein homeostasis in the aging brain. Cell 2024, 187, 4193-4212.e24. [CrossRef]

- Galvanetto, N., Ivanović, M.T., Chowdhury, A., Sottini, A., Nüesch, M.F., Nettels, D., Best, R.B., Schuler, B. Extreme dynamics in a biomolecular condensate. Nature 2023, 619, 876-883. [CrossRef]

- Del Blanco, B., Niñerola, S., Martín-González, A.M., Paraíso-Luna, J., Kim, M., Muñoz-Viana, R., Racovac, C., Sanchez-Mut, J.V., Ruan, Y., Barco, Á. Kdm1a safeguards the topological boundaries of PRC2-repressed genes and prevents aging-related euchromatinization in neurons. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1781. [CrossRef]

- Hnisz, D., Shrinivas, K., Young, R.A., Chakraborty, A.K., Sharp, P.A. A Phase Separation Model for Transcriptional Control. Cell 2017, 169, 13-23. [CrossRef]

- Franke, M., Ibrahim, D.M., Andrey, G., Schwarzer, W., Heinrich, V., Schöpflin, R., Kraft, K., Kempfer, R., Jerković, I., Chan, W.L., Spielmann, M., Timmermann, B., Wittler, L., Kurth, I., Cambiaso, P., Zuffardi, O., Houge, G., Lambie, L., Brancati, F., Pombo, A., Vingron, M., Spitz, F., Mundlos, S. Formation of new chromatin domains determines pathogenicity of genomic duplications. Nature 2016, 538, 265-269. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.R., Selvaraj, S., Yue, F., Kim, A., Li, Y., Shen, Y., Hu, M., Liu, J.S., Ren, B. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 2012, 485, 376-80. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, Q., Bantignies, F., Cavalli, G. Principles of genome folding into topologically associating domains. Sci Adv 2019, 5, eaaw1668. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman-Aiden, E., van Berkum, N.L., Williams, L., Imakaev, M., Ragoczy, T., Telling, A., Amit, I., Lajoie, B.R., Sabo, P.J., Dorschner, M.O., Sandstrom, R., Bernstein, B., Bender, M.A., Groudine, M., Gnirke, A., Stamatoyannopoulos, J., Mirny, L.A., Lander, E.S., Dekker, J. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 2009, 326, 289-93. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S., Huntley, M.H., Durand, N.C., Stamenova, E.K., Bochkov, I.D., Robinson, J.T., Sanborn, A.L., Machol, I., Omer, A.D., Lander, E.S., Aiden, E.L. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 2014, 159, 1665-1680. [CrossRef]

- Fullwood, M.J., Liu, M.H., Pan, Y.F., Liu, J., Xu, H., Mohamed, Y.B., Orlov, Y.L., Velkov, S., Ho, A., Mei, P.H., Chew, E.G., Huang, P.Y., Welboren, W.J., Han, Y., Ooi, H.S., Ariyaratne, P.N., Vega, V.B., Luo, Y., Tan, P.Y., Choy, P.Y., Wansa, K.D., Zhao, B., Lim, K.S., Leow, S.C., Yow, J.S., Joseph, R., Li, H., Desai, K.V., Thomsen, J.S., Lee, Y.K., Karuturi, R.K., Herve, T., Bourque, G., Stunnenberg, H.G., Ruan, X., Cacheux-Rataboul, V., Sung, W.K., Liu, E.T., Wei, C.L., Cheung, E., Ruan, Y. An oestrogen-receptor-alpha-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature 2009, 462, 58-64. [CrossRef]

- Van Bortle, K., Nichols, M.H., Li, L., Ong, C.T., Takenaka, N., Qin, Z.S., Corces, V.G. Insulator function and topological domain border strength scale with architectural protein occupancy. Genome Biol 2014, 15, R82. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, T., Ninomiya, K., Nakagawa, S., Yamazaki, T. A guide to membraneless organelles and their various roles in gene regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023, 24, 288-304. [CrossRef]

- Putnam, A., Thomas, L., Seydoux, G. RNA granules: functional compartments or incidental condensates? Genes Dev 2023, 37, 354-376. [CrossRef]

- Emenecker, R.J., Holehouse, A.S., Strader, L.C. Emerging Roles for Phase Separation in Plants. Dev Cell 2020, 55, 69-83. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z., Zhang, W., Chang, R., Zhang, S., Yang, G., Zhao, G. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation: Unraveling the Enigma of Biomolecular Condensates in Microbial Cells. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 751880. [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, E., Audas, T.E. Keeping up with the condensates: The retention, gain, and loss of nuclear membrane-less organelles. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 998363. [CrossRef]

- Rostam, N., Ghosh, S., Chow, C.F.W., Hadarovich, A., Landerer, C., Ghosh, R., Moon, H., Hersemann, L., Mitrea, D.M., Klein, I.A., Hyman, A.A., Toth-Petroczy, A. CD-CODE: crowdsourcing condensate database and encyclopedia. Nat Methods 2023, 20, 673-676. [CrossRef]

- Lafontaine, D.L.J., Riback, J.A., Bascetin, R., Brangwynne, C.P. The nucleolus as a multiphase liquid condensate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 165-182. [CrossRef]

- Standard, N., Weil, D. P-Bodies: Cytosolic Droplets for Coordinated mRNA Storage. Trends Genet 2018, 34,612-626. [CrossRef]

- Faber, G.P., Nadav-Eliyahu, S., Shav-Tal, Y. Nuclear speckles - a driving force in gene expression. J Cell Sci 2022, 135, jcs259594. [CrossRef]

- Vidya, E., Duchaine, T.F. Eukaryotic mRNA Decapping Activation. Front Genet 2022, 13, 832547. [CrossRef]

- Ries, R.J., Pickering, B.F., Poh, H.X., Namkoong, S., Jaffrey, S.R. m6A governs length-dependent enrichment of mRNAs in stress granules. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2023, 30, 1525-1535. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.E., de Queiroz, B.R., Kiebler, M.A., Besse, F. RNA granules in neuronal plasticity and disease. Trends Neurosci 2023, 46, 525-538. [CrossRef]

- Gershoni-Emek, N., Altman, T., Ionescu, A., Costa, C.J., Gradus-Pery, T., Willis, D.E., Perlson, E. Localization of RNAi Machinery to Axonal Branch Points and Growth Cones Is Facilitated by Mitochondria and Is Disrupted in ALS. Front Mol Neurosci 2018, 11, 311. [CrossRef]

- Corradi, E., Dalla Costa, I., Gavoci, A., Iyer, A., Roccuzzo, M., Otto, T.A., Oliani, E., Bridi, S., Strohbuecker, S., Santos-Rodriguez, G., Valdembri, D., Serini, G., Abreu-Goodger, C., Baudet, M.L. Axonal precursor miRNAs hitchhike on endosomes and locally regulate the development of neural circuits. EMBO J 2020, 39, e102513. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.C., Fernandopulle, M.S., Wang, G., Choi, H., Hao, L., Drerup, C.M., Patel, R., Qamar, S., Nixon-Abell, J., Shen, Y., Meadows, W., Vendruscolo, M., Knowles, T.P.J., Nelson, M., Czekalska, M.A., Musteikyte, G., Gachechiladze, M.A., Stephens, C.A., Pasolli, H.A., Forrest, L.R., St George-Hyslop, P., Lim, J.P., Brunet, A. Bridging the transgenerational gap with epigenetic memory. Trends Genet 2013, 29, 176-186. [CrossRef]

- De Pace, R., Ghosh, S., Ryan, V.H., Sohn, M., Jarnik, M., Rezvan Sangsari, P., Morgan, N.Y., Dale, R.K., Ward, M.E., Bonifacino, J.S. Messenger RNA transport on lysosomal vesicles maintains axonal mitochondrial homeostasis and prevents axonal degeneration. Nat Neurosci 2024, 27, 1087-1102. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, A.W., McNally, M.T., Mouland, A.J. The retrovirus RNA trafficking granule: from birth to maturity. Retrovirology 2006, 3, 18. [CrossRef]

- Cioni, J.M., Lin, J.Q., Holtermann, A.V., Koppers, M., Jakobs, M.A.H., Azizi, A., Turner-Bridger, B., Shigeoka, T., Franze, K., Harris, W.A., Holt, C.E. Late Endosomes Act as mRNA Translation Platforms and Sustain Mitochondria in Axons. Cell 2019, 176, 56-72.e15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H., Guo, K.X., Li, J., Xu, S.H., Zhu, H., Yan, G.R. Regulations of m6A and other RNA modifications and their roles in cancer. Front Med 2024, 18, 622-648. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L., Jing, Q., Li, Y., Han, J. RNA modification: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Mol Biomed 2023, 4, 25. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zhou, Z., Chen, Y., Chen, D. Reading the m6A-encoded epitranscriptomic information in development and diseases. Cell Biosci 2024, 14, 124. [CrossRef]

- Kahl, M., Xu, Z., Arumugam, S., Edens, B., Fischietti, M., Zhu, A.C., Platanias, L.C., He, C., Zhuang, X., Ma, Y.C. m6A RNA methylation regulates mitochondrial function. Hum Mol Genet 2024, 33, 969-980. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Liu, Z., Zhang, L. et al. The lncRNA SNHG26 drives the inflammatory-to-proliferative state transition of keratinocyte progenitor cells during wound healing. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8637. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Kim, S.H., Yang, E., Kang, M., Joo, J.Y. Molecular insights into regulatory RNAs in the cellular machinery. Exp Mol Med 2024, 56, 1235-1249. [CrossRef]

- Fris, M.E., Murphy, E.R. Riboregulators: Fine-Tuning Virulence in Shigella. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2016, 6, 2. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T., Ngo, L.H., Wickramasinghe, V.O. Nuclear export of RNA: Different sizes, shapes and functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2018, 75, 70-77. [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, A.F., Qiu, Y., Kang, Y.M. mRNA nuclear export: how mRNA identity features distinguish functional RNAs from junk transcripts. RNA Biol 2024, 21, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Ren, Y. Mechanisms of nuclear mRNA export: A structural perspective. Traffic 2019, 20, 829-840. [CrossRef]

- Coban, I., Lamping, J.P., Hirsch, A.G., Wasilewski, S., Shomroni, O., Giesbrecht, O., Salinas, G., Krebber, H. dsRNA formation leads to preferential nuclear export and gene expression. Nature 2024, 631, 432-438. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, K., Ly, J., Bartel, D.P. Control of poly(A)-tail length and translation in vertebrate oocytes and early embryos. Dev Cell 2024, 59, 1058-1074.e11. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.J., Mubaid, S., Busque, S., de Los Santos, Y.L., Ashour, K., Sadek, J., Lian, X.J., Khattak, S., Di Marco, S., Gallouzi, I.E. The formation of HuR/YB1 complex is required for the stabilization of target mRNA to promote myogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 1375-1392. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Zhan, S., Zhao, S., Zhong, T., Wang, L., Guo, J., Dai, D., Li, D., Cao, J., Li, L., Zhang, H. HuR Promotes the Differentiation of Goat Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells by Regulating Myomaker mRNA Stability. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 6893. [CrossRef]

- Nabeel-Shah, S., Pu, S., Burns, J.D., Braunschweig, U., Ahmed, N., Burke, G.L., Lee, H., Radovani, E., Zhong, G., Tang, H., Marcon, E., Zhang, Z., Hughes, T.R., Blencowe, B.J., Greenblatt, J.F. C2H2-zinc-finger transcription factors bind RNA and function in diverse post-transcriptional regulatory processes. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 3810-3825.e10. [CrossRef]

- Nabeel-Shah, S., Pu, S., Burke, G.L., Ahmed, N., Braunschweig, U., Farhangmehr, S., Lee, H., Wu, M., Ni, Z., Tang, H., Zhong, G., Marcon, E., Zhang, Z., Blencowe, B.J., Greenblatt, J.F. Recruitment of the m6A/m6Am demethylase FTO to target RNAs by the telomeric zinc finger protein ZBTB48. Genome Biol 2024, 25, 246. [CrossRef]

- Song, J., Nabeel-Shah, S., Pu, S., Lee, H., Braunschweig, U., Ni, Z., Ahmed, N., Marcon, E., Zhong, G., Ray, D., Ha, K.C.H., Guo, X., Zhang, Z., Hughes, T.R., Blencowe, B.J., Greenblatt, J.F. Regulation of alternative polyadenylation by the C2H2-zinc-finger protein Sp1. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 3135-3150.e9. [CrossRef]

- Kilchert, C., Wittmann, S., Vasiljeva, L. The regulation and functions of the nuclear RNA exosome complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17, 227–239. [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, N., Zuber, H., Gobert, A. et al. RNA degradation by the plant RNA exosome involves both phosphorolytic and hydrolytic activities. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 2162. [CrossRef]

- Kögel, A., Keidel, A., Loukeri, M.J. et al. Structural basis of mRNA decay by the human exosome–ribosome supercomplex. Nature 2024. [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, R.M., Picard, C.L. RNA-directed DNA Methylation. PLoS Genet 2020, 16, e1009034. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, R.A., Pedram, K., Malaker, S.A., Batista, P.J., Smith, B.A.H., Johnson, A.G., George, B.M., Majzoub, K., Villalta, P.W., Carette, J.E., Bertozzi, C.R. Small RNAs are modified with N-glycans and displayed on the surface of living cells. Cell 2021, 184, 3109-3124.e22. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Chai, P., Till, N.A., Hemberger, H., Lebedenko, C.G., Porat, J., Watkins, C.P., Caldwell, R.M., George, B.M., Perr, J., Bertozzi, C.R., Garcia, B.A., Flynn, R.A. The modified RNA base acp3U is an attachment site for N-glycans in glycoRNA. Cell 2024, Aug 15:S0092-8674, 00838-9. [CrossRef]

- Nachtergaele, S., Krishnan, Y. New Vistas for Cell-Surface GlycoRNAs. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 658-660. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, W., Pandey, V., Pokharel, Y.R. Membrane linked RNA glycosylation as new trend to envision epi-transcriptome epoch. Cancer Gene Ther 2023, 30, 641–646. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., Tang, W., Torres, L., Wang, X., Ajaj, Y., Zhu, L., Luan, Y., Zhou, H., Wang, Y., Zhang, D., Kurbatov, V., Khan, S.A., Kumar, P., Hidalgo, A., Wu, D., Lu, J. Cell surface RNAs control neutrophil recruitment. Cell 2024, 187, 846-860.e17. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Guo, W., Mou, Q., Shao, X., Lyu, M., Garcia, V., Kong, L., Lewis, W., Ward, C., Yang, Z., Pan, X., Yi, S.S., Lu, Y. Spatial imaging of glycoRNA in single cells with ARPLA. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 608-616. [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H., Ekström, K., Bossios, A. et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654–659. [CrossRef]

- Weiberg, A., Wang, M., Lin, F.M., Zhao, H., Zhang, Z., Kaloshian, I., Huang, H.D, Jin, H. Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science 2013, 342, 118-123. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q., Qiao, L., Wang, M., He, B., Lin, F.M., Palmquist, J., Huang, S.D., Jin, H. Plants send small RNAs in extracellular vesicles to fungal pathogen to silence virulence genes. Science 2018, 360, 1126-1129. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., He, B., Wu, H., Cai, Q., Ramírez-Sánchez, O., Abreu-Goodger, C., Birch, P.R.J., Jin, H. Plant mRNAs move into a fungal pathogen via extracellular vesicles to reduce infection. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 93-105.e6. [CrossRef]

- Buck, A., Coakley, G., Simbari, F. et al. Exosomes secreted by nematode parasites transfer small RNAs to mammalian cells and modulate innate immunity. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5488. [CrossRef]

- Koeppen, K., Hampton, T.H., Jarek, M., Scharfe, M., Gerber, S.A., Mielcarz, D.W., Demers, E.G., Dolben, E.L., Hammond, J.H., Hogan, D.A., Stanton, B.A. A Novel Mechanism of Host-Pathogen Interaction through sRNA in Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005672. [CrossRef]

- Halder, L.D., Babych, S., Palme, D.I., Mansouri-Ghahnavieh, E., Ivanov, L., Ashonibare, V., Langenhorst, D., Prusty, B., Rambach, G., Wich, M., Trinks, N., Blango, M.G., Kornitzer, D., Terpitz, U., Speth, C., Jungnickel, B., Beyersdorf, N., Zipfel, P.F., Brakhage, A.A., Skerka, C. Candida albicans Induces Cross-Kingdom miRNA Trafficking in Human Monocytes To Promote Fungal Growth. mBio 2022, 13, e03563-21. [CrossRef]

- Ren, B., Wang, X., Duan, J., Ma, J. Rhizobial tRNA-derived small RNAs are signal molecules regulating plant nodulation. Science 2019, 365, 919-922. [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.C., Jucker, M. The prion principle and Alzheimer's disease. Science 2024, 385, 1278-1279. [CrossRef]

- Bridges, L.R. RNA as a component of scrapie fibrils. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5011. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Zhang, W., Yang, Y., Murzin, A.G., Falcon, B., Kotecha, A., van Beers, M., Tarutani, A., Kametani, F., Garringer, H.J., Vidal, R., Hallinan, G.I., Lashley, T., Saito, Y., Murayama, S., Yoshida, M., Tanaka, H., Kakita, A., Ikeuchi, T., Robinson, A.C., Mann, D.M.A., Kovacs, G.G., Revesz, T., Ghetti, B., Hasegawa, M., Goedert, M., Scheres, S.H.W. Structure-based classification of tauopathies. Nature 2021, 598, 359-363. [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.F., Loureiro, J.R., Bessa, J., Silveira, I. Antisense Transcription across Nucleotide Repeat Expansions in Neurodegenerative and Neuromuscular Diseases: Progress and Mysteries. Genes 2020, 11, 1418. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Canasto-Chibuque, C., Kim, J.H., Hohl, M., Leslie, C., Reis-Filho, J.S., Petrini, J.H.J. Chronic interferon-stimulated gene transcription promotes oncogene-induced breast cancer. Genes Dev 2024, Oct 25. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.G., Ritter, C., Kummer, E. Structural insights into the role of GTPBP10 in the RNA maturation of the mitoribosome. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7991. [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.W., Burger, G., Lang, B.F. Mitochondrial evolution. Science 1999, 283, 1476-1481. [CrossRef]

- Rius, R., Compton, A.G., Baker, N.L., Balasubramaniam, S., Best, S., Bhattacharya, K., Boggs, K., Boughtwood, T., Braithwaite, J., Bratkovic, D., Bray, A., Brion, M.J., Burke, J., Casauria, S., Chong, B., Coman, D., Cowie, S., Cowley, M., de Silva, M.G., Delatycki, M.B., Edwards, S., Ellaway, C., Fahey, M.C., Finlay, K., Fletcher, J., Frajman, L.E., Frazier, A.E., Gayevskiy, V., Ghaoui, R., Goel, H., Goranitis, I., Haas, M., Hock, D.H., Howting, D., Jackson, M.R., Kava, M.P., Kemp, M., King-Smith, S., Lake, N.J., Lamont, P.J., Lee, J., Long, J.C., MacShane, M., Madelli, E.O., Martin, E.M., Marum, J.E., Mattiske, T., McGill, J., Metke, A., Murray, S., Panetta, J., Phillips, L.K., Quinn, M.C.J., Ryan, M.T., Schenscher, S., Simons, C., Smith, N., Stroud, D.A., Tchan, M.C., Tom, M., Wallis, M., Ware, T.L., Welch, A.E., Wools, C., Wu, Y., Christodoulou, J., Thorburn, D.R. The Australian Genomics Mitochondrial Flagship: A National Program Delivering Mitochondrial Diagnoses. Genet Med 2024, Sep 17, 101271. [CrossRef]

- Grand, R.S., Pregnolato, M., Baumgartner, L., Hoerner, L., Burger, L., Schübeler, D. Genome access is transcription factor-specific and defined by nucleosome position. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 3455-3468.e6. [CrossRef]

- Banerji, J., Rusconi, S., Schaffner, W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell 1981, 27, 299-308. [CrossRef]

- Dunipace, L., Ozdemir, A., Stathopoulos, A. Complex interactions between cis-regulatory modules in native conformation are critical for Drosophila snail expression. Development 2011, 138, 4075-4084. [CrossRef]

- Lagha, M., Bothma, J.P., Levine, M. Mechanisms of transcriptional precision in animal development. Trends Genet 2012, 28, 409-416. [CrossRef]

- Levine, M. Transcriptional enhancers in animal development and evolution. Curr Biol 2010, 20, R754-63. [CrossRef]

- Waite, J.B., Boytz, R., Traeger, A.R., Lind, T.M., Lumbao-Conradson, K., Torigoe, S.E. A suboptimal OCT4-SOX2 binding site facilitates the naïve-state specific function of a Klf4 enhancer. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0311120. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S., Ahmad, K., Ramachandran, S. Cooperative binding between distant transcription factors is a hallmark of active enhancers. Mol Cell 2021, 81, 1651-1665.e4. [CrossRef]

- Horton, C.A., Alexandari, A.M., Hayes, M.G.B., Marklund, E., Schaepe, J.M., Aditham, A.K., Shah, N., Suzuki, P.H., Shrikumar, A., Afek, A., Greenleaf, W.J., Gordân, R., Zeitlinger, J., Kundaje, A., Fordyce, P.M. Short tandem repeats bind transcription factors to tune eukaryotic gene expression. Science 2023, 381, eadd1250. [CrossRef]

- Spolski, R., Li, P., Chandra, V., Shin, B., Goel, S., Sakamoto, K., Liu, C., Oh, J., Ren, M., Enomoto, Y., West, E.E., Christensen, S.M., Wan, E.C.K., Ge, M., Lin, J.X., Yan, B., Kazemian, M., Yu, Z.X., Nagao, K., Vijayanand, P., Rothenberg, E.V., Leonard, W.J. Distinct use of super-enhancer elements controls cell type-specific CD25 transcription and function. Sci Immunol.2023, 8, eadi8217. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., Kleinschmidt, H., Yang, J., Leith, E.M., Johnson, J., Tan, S., Mahony, S., Bai, L. Systematic dissection of sequence features affecting binding specificity of a pioneer factor reveals binding synergy between FOXA1 and AP-1. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 2838-2855.e10. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z., Dou, X., Li, Y., Zhang, Z., Wang, J., Gao, B., Xiao, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, L., Sun, C., Liu, Q., Yu, X., Wang, H., Hong, J., Dai, Q., Yang, F.C., Xu, M., He, C. RNA m5C oxidation by TET2 regulates chromatin state and leukaemogenesis. Nature 2024, Oct 2. [CrossRef]

- Yao, W., Hu, X., Wang, X. Crossing epigenetic frontiers: the intersection of novel histone modifications and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 232. [CrossRef]

- Lukauskas, S., Tvardovskiy, A., Nguyen, N.V., Stadler, M., Faull, P., Ravnsborg, T., Özdemir Aygenli, B., Dornauer, S., Flynn, H., Lindeboom, R.G.H., Barth, T.K., Brockers, K., Hauck, S.M., Vermeulen, M., Snijders, A.P., Müller, C.L., DiMaggio, P.A., Jensen, O.N., Schneider, R., Bartke, T. Decoding chromatin states by proteomic profiling of nucleosome readers. Nature 2024, 627, 671-679. [CrossRef]

- Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium, Kundaje, A., Meuleman, W., Ernst, J., Bilenky, M., Yen, A., Heravi-Moussavi, A., Kheradpour, P., Zhang, Z., Wang, J., Ziller, M.J., Amin, V., Whitaker, J.W., Schultz, M.D., Ward, L.D., Sarkar, A., Quon, G., Sandstrom, R.S., Eaton, M.L., Wu, Y.C., Pfenning, A.R., Wang, X., Claussnitzer, M., Liu, Y., Coarfa, C., Harris, R.A., Shoresh, N., Epstein, C.B., Gjoneska, E., Leung, D., Xie, W., Hawkins, R.D., Lister, R., Hong, C., Gascard, P., Mungall, A.J., Moore, R., Chuah, E., Tam, A., Canfield, T.K., Hansen, R.S., Kaul, R., Sabo, P.J., Bansal, M.S., Carles, A., Dixon, J.R., Farh, K.H., Feizi, S., Karlic, R., Kim, A.R., Kulkarni, A., Li, D., Lowdon, R., Elliott, G., Mercer, T.R., Neph, S.J., Onuchic, V., Polak, P., Rajagopal, N., Ray, P., Sallari, R.C., Siebenthall, K.T., Sinnott-Armstrong, N.A., Stevens, M., Thurman, R.E., Wu, J., Zhang, B., Zhou, X., Beaudet, A.E., Boyer, L.A., De Jager, P.L., Farnham, P.J., Fisher, S.J., Haussler, D., Jones, S.J., Li, W., Marra, M.A., McManus, M.T., Sunyaev, S., Thomson, J.A., Tlsty, T.D., Tsai, L.H., Wang, W., Waterland, R.A., Zhang, M.Q., Chadwick, L.H., Bernstein, B.E., Costello, J.F., Ecker, J.R., Hirst, M., Meissner, A., Milosavljevic, A., Ren, B., Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A., Wang, T., Kellis, M. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 2015, 518, 317-330. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J., Kellis, M. Discovery and characterization of chromatin states for systematic annotation of the human genome. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28, 817-25. [CrossRef]

- Bošković, A., Rando, O.J. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance. Annu Rev Genet 2018, 52, 21-41. [CrossRef]

- Daxinger, L., Whitelaw, E. Understanding transgenerational epigenetic inheritance via the gametes in mammals. Nat Rev Genet 2012, 13, 153-62. [CrossRef]

- Grossniklaus, U., Kelly William, G., Kelly, B., Ferguson-Smith, A.C., Pembrey, M., Lindquist, S. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: how important is it? Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14, 228-235. [CrossRef]

- Heard, E., Martienssen, R.A. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: myths and mechanisms. Cell 2014, 157, :95-109. [CrossRef]

- Horsthemke, B. A critical view on transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2973. [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, E., Raz, G. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: prevalence, mechanisms, and implications for the study of heredity and evolution. Q Rev Biol 2009, 84, 2, 131-76. [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, G., Heard, E. Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature 2019, 571, 489-499. [CrossRef]

- Radford, E.J. Exploring the extent and scope of epigenetic inheritance. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018, 14, 345-355. [CrossRef]

- Rechavi, O., Lev, I. Principles of Transgenerational Small RNA Inheritance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol 2017, 27, R720-R730. https://doi.org10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.043.

- Perez, M.F., Lehner, B. Intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in animals. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 21, 143-151. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y., Morales Valencia, M., Yu, Y., Ouchi, Y., Takahashi, K., Shokhirev, M.N., Lande, K., Williams, A.E., Fresia, C., Kurita, M., Hishida, T., Shojima, K., Hatanaka, F., Nuñez-Delicado, E., Esteban, C.R., Izpisua Belmonte, J.C. Transgenerational inheritance of acquired epigenetic signatures at CpG islands in mice. Cell 2023, 186, 715-731.e19. [CrossRef]

- Waldvogel, S.M., Posey, J.E., Goodell, M.A. Human embryonic genetic mosaicism and its effects on development and disease. Nat Rev Genet 2024, 25, 698-714. [CrossRef]

- McClintock, B. Chromosome organization and genic expression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 1951, 16, 13-47. [CrossRef]

- Stepankiw, N., Yang, A.W.H., Hughes, T.R. The human genome contains over a million autonomous exons. Genome Res 2023, 33, 1865-1878. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, P., Carbonell-Sala, S., De La Vega, F.M., Faial, T., Frankish, A., Gingeras, T., Guigo, R., Harrow, J.L., Hatzigeorgiou, A.G., Johnson, R., Murphy, T.D., Pertea, M., Pruitt, K.D., Pujar, S., Takahashi, H., Ulitsky, I., Varabyou, A., Wells, C.A., Yandell, M., Carninci, P., Salzberg, S.L. The status of the human gene catalogue. Nature 2023, 622, 41-47. https::/doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06490-x.

- Inamo, J., Suzuki, A., Ueda, M.T., Yamaguchi, K., Nishida, H., Suzuki, K., Kaneko, Y., Takeuchi, T., Hatano, H., Ishigaki, K., Ishihama, Y., Yamamoto, K., Kochi, Y. Long-read sequencing for 29 immune cell subsets reveals disease-linked isoforms. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4285. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q., Shai, O., Lee, L.J., Frey, B.J., Blencowe, B.J. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 2008, 40, 1413-1415. [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.T., Sandberg, R., Luo, S., Khrebtukova, I., Zhang, L., Mayr, C., Kingsmore, S.F., Schroth, G.P., Burge, C.B. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 2008, 456, 470-476. [CrossRef]

- Frankish, A., Diekhans, M., Jungreis, I., Lagarde, J., Loveland, J.E., Mudge, J.M., Sisu, C., Wright, J.C., Armstrong, J., Barnes, I., Berry, A., Bignell, A., Boix, C., Carbonell Sala, S., Cunningham, F., Di Domenico, T., Donaldson, S., Fiddes, I.T., García Girón, C., Gonzalez, J.M., Grego, T., Hardy, M., Hourlier, T., Howe, K.L., Hunt, T., Izuogu, O.G., Johnson, R., Martin, F.J., Martínez, L., Mohanan, S., Muir, P., Navarro, F.C.P., Parker, A., Pei, B., Pozo, F., Riera, F.C., Ruffier, M., Schmitt, B.M., Stapleton, E., Suner, M.M., Sycheva, I., Uszczynska-Ratajczak, B., Wolf, M.Y., Xu, J., Yang, Y.T., Yates, A., Zerbino, D., Zhang, Y., Choudhary, J.S., Gerstein, M., Guigó, R., Hubbard, T.J.P., Kellis, M., Paten, B., Tress, M.L., Flicek, P. GENCODE 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D916-D923. [CrossRef]

- Baralle, F.E., Giudice, J. Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18, 437-451. [CrossRef]

- Carvill, G.L., Engel, K.L., Ramamurthy, A., Cochran, J.N., Roovers, J., Stamberger, H., Lim, N., Schneider, A.L., Hollingsworth, G., Holder, D.H., Regan, B.M., Lawlor, J., Lagae, L., Ceulemans, B., Bebin, E.M., Nguyen, J.; EuroEPINOMICS Rare Epilepsy Syndrome, Myoclonic-Astatic Epilepsy, and Dravet Working Group; Barsh, G.S., Weckhuysen, S., Meisler, M., Berkovic, S.F., De Jonghe, P., Scheffer, I.E., Myers, R.M., Cooper, G.M., Mefford, H.C. Aberrant Inclusion of a Poison Exon Causes Dravet Syndrome and Related SCN1A-Associated Genetic Epilepsies. Am J Hum Genet 2018, 103, 1022-1029. [CrossRef]

- Leppek, K., Das, R., Barna, M. Functional 5' UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 158-174. [CrossRef]

- Griesemer, D., Xue, J.R., Reilly, S.K., Ulirsch, J.C., Kukreja, K., Davis, J.R., Kanai, M., Yang, D.K., Butts, J.C., Guney, M.H., Luban, J., Montgomery, S.B., Finucane, H.K., Novina, C.D., Tewhey, R., Sabeti, P.C. Genome-wide functional screen of 3'UTR variants uncovers causal variants for human disease and evolution. Cell 2021, 184, 5247-5260.e19. [CrossRef]

- Poliseno, L., Lanza, M. & Pandolfi, P.P. Coding, or non-coding, that is the question. Cell Res 2024, 34, 609–629. [CrossRef]

- Erokhina, T.N., Ryazantsev, D.Y., Zavriev, S.K., Morozov, S.Y. Biological Activity of Artificial Plant Peptides Corresponding to the Translational Products of Small ORFs in Primary miRNAs and Other Long "Non-Coding" RNAs. Plants (Basel) 2024, 13, 1137. [CrossRef]

- Logeswaran, D., Li, Y., Akhter, K., Podlevsky, J.D., Olson, T.L., Forsberg, K., Chen, J.J. Biogenesis of telomerase RNA from a protein-coding mRNA precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2204636119. [CrossRef]

- Al-Turki, T.M., Griffith, J.D. Mammalian telomeric RNA (TERRA) can be translated to produce valine-arginine and glycine-leucine dipeptide repeat proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2221529120. [CrossRef]

- Koch, L. Gene synthesis from a non-coding RNA. Nat Rev Genet 2024, 25, 747. [CrossRef]

- Millman, A., Bernheim, A., Stokar-Avihail, A., Fedorenko, T., Voichek, M., Leavitt, A., Oppenheimer-Shaanan, Y., Sorek, R. Bacterial Retrons Function In Anti-Phage Defense. Cell 2020, 183, 1551-1561.e12. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Altae-Tran, H., Böhning, F., Makarova, K.S., Segel, M., Schmid-Burgk, J.L., Koob, J., Wolf, Y.I., Koonin, E.V., Zhang, F. Diverse enzymatic activities mediate antiviral immunity in prokaryotes. Science 2020, 369, 1077-1084. [CrossRef]

- Saunier, M., Fortier, L.C., Soutourina, O. RNA-based regulation in bacteria-phage interactions. Anaerobe 2024, 87, 102851. [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, A., Mestre, M.R., Martínez-Abarca, F., Toro, N. Prokaryotic reverse transcriptases: from retroelements to specialized defense systems. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2021, 45, fuab025. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, D., Florian, C., Doherty, B.M., White, K.M., Reardon, K.M., Ge, X., Garbow, J.R., Yuede, C.M., Cirrito, J.R., Dougherty, J.D. Aqp4 stop codon readthrough facilitates amyloid-β clearance from the brain. Brain 2022, 145, 2982-2990. [CrossRef]

- Loughran, G., Chou, M.Y., Ivanov, I.P., Jungreis, I., Kellis, M., Kiran, A.M., Baranov, P.V., Atkins, J.F. Evidence of efficient stop codon readthrough in four mammalian genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 8928-8938. [CrossRef]

- Sandmann, C.L., Schulz, J.F., Ruiz-Orera, J., Kirchner, M., Ziehm, M., Adami, E., Marczenke, M., Christ, A., Liebe, N., Greiner, J., Schoenenberger, A., Muecke, M.B., Liang, N., Moritz, R.L., Sun, Z., Deutsch, E.W., Gotthardt, M., Mudge, J.M., Prensner, J.R., Willnow, T.E., Mertins, P., van Heesch, S., Hubner, N. Evolutionary origins and interactomes of human, young microproteins and small peptides translated from short open reading frames. Mol Cell 2023, 83, 994-1011.e18. [CrossRef]

- Ardern, Z. Alternative Reading Frames are an Underappreciated Source of Protein Sequence Novelty. J Mol Evol 2023, 91, 570-580. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A., Chan Mine, E., Gaifas, L., Leyrat, C., Volchkova, V.A., Baudin, F., Martinez-Gil, L., Volchkov, V.E., Karlin, D.G., Bourhis, J.M., Jamin, M. Orthoparamyxovirinae C Proteins Have a Common Origin and a Common Structural Organization. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 455. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.C., Brown, J.W. Genes within genes within bacteria. Trends Biochem Sci 2003, 28, 521-523. [CrossRef]

- Meydan, S., Vázquez-Laslop, N., Mankin, A.S. Genes within Genes in Bacterial Genomes. Microbiol Spectr 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., Slavoff, S.A. Non-AUG start codons: Expanding and regulating the small and alternative ORFeome. Exp Cell Res 2020, 391, 111973. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.C., Liu, M.J. Translation initiation at AUG and non-AUG triplets in plants. Plant Sci 2023, 335, 111822. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Board on Life Sciences; Toward Sequencing and Mapping of RNA Modifications Committee. Charting a Future for Sequencing RNA and Its Modifications: A New Era for Biology and Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2024 Jul 22. PMID: 39159274.

- Quarleri, J., Galvan, V., Delpino, M.V. Henipaviruses: an expanding global public health concern? Geroscience 2022, 44, 2447-2459. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.L. Henipaviruses employ a multifaceted approach to evade the antiviral interferon response. Viruses 2009, 1, 1190-1203. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T., Niu, G., Zhang, Y., Chen, M., Li, C.Y., Hao, L., Zhang, Z. Host-mediated RNA editing in viruses. Biol Direct 2023, 18, 12. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J., Drummond, A.J., Kingston, R.L. Evolutionary history of cotranscriptional editing in the paramyxoviral phosphoprotein gene. Virus Evol 2021, 7, veab028. [CrossRef]

- Shook, E.N., Barlow, G.T., Garcia-Rosales, D., Gibbons, C.J., Montague, T.G. Dynamic skin behaviors in cephalopods. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2024, 86, 102876. [CrossRef]

- Zolotarov, G., Fromm, B., Legnini, I., Ayoub, S., Polese, G., Maselli, V., Chabot, P.J., Vinther, J., Styfhals, R., Seuntjens, E., Di Cosmo, A., Peterson, K.J., Rajewsky, N. MicroRNAs are deeply linked to the emergence of the complex octopus brain. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eadd9938. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T., Nguyen, T., Zhou, B., Zheng, Y.G. Chemical probes and methods for the study of protein arginine methylation. RSC Chem Biol 2023, 4, 647-669. [CrossRef]

- Motone, K., Kontogiorgos-Heintz, D., Wee, J. et al. Multi-pass, single-molecule nanopore reading of long protein strands. Nature 2024, 633, 662–669. [CrossRef]

- Romerio, F. Origin and functional role of antisense transcription in endogenous and exogenous retroviruses. Retrovirology 2023, 20, 6. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, B.R., Grandchamp, A., Bornberg-Bauer, E. How antisense transcripts can evolve to encode novel proteins. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 6187. [CrossRef]

- Bardou, F., Merchan, F., Ariel, F., Crespi, M. Dual RNAs in plants. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1950-1954. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., Huang, Z., Yang, R., Chen, Y., Wang, Q., Gao, L. Insights into Enhancer RNAs: Biogenesis and Emerging Role in Brain Diseases. Neuroscientist 2023, 29, 166-176. [CrossRef]

- Ye, R., Cao, C., Xue, Y. Enhancer RNA: biogenesis, function, and regulation. Essays Biochem 2020, 64, 883-894. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z., Li, W. Enhancer RNA: What we know and what we can achieve. Cell Prolif 2022, 55, e13202. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Wang, W., Wu, Y., Qiu, Y., Zhang, L. LINC00887 Acts as an Enhancer RNA to Promote Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma Progression by Binding with FOXQ1. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2024, 24, 519-533. [CrossRef]

- Manrubia, S. The simple emergence of complex molecular function. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 2022, 380, 20200422. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.I., Xulvi-Brunet, R., Campbell, G.W., Turk-MacLeod, R., Chen, I.A. Comprehensive experimental fitness landscape and evolutionary network for small RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 14984-14989. [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.L., Wagner, A. The robustness and evolvability of transcription factor binding sites. Science 2014, 343, 875-877. [CrossRef]

- Wucherpfennig, KW. Structural basis of molecular mimicry. J Autoimmun 2001, 16, 293-302. [CrossRef]

- Tsonis, P.A., Dwivedi, B. Molecular mimicry: structural camouflage of proteins and nucleic acids. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008, 1783, 177-187. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, N., Lehman, N. One RNA plays three roles to provide catalytic activity to a group I intron lacking an endogenous internal guide sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, 3981-3989. https://doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp271.

- Vaidya, N., Manapat, M.L., Chen, I.A., Xulvi-Brunet, R., Hayden, E.J., Lehman, N. Spontaneous network formation among cooperative RNA replicators. Nature 2012, 491, 72-77. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. Mutational robustness accelerates the origin of novel RNA phenotypes through phenotypic plasticity. Biophys J 2014, 106, 955-965. [CrossRef]

- Khersonsky, O., Tawfik, D.S. Enzyme promiscuity: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Annu Rev Biochem 2010, 79, 471-505. [CrossRef]

- Alfano, C., Fichou, Y., Huber, K., Weiss, M., Spruijt, E., Ebbinghaus, S., De Luca, G., Morando, M.A., Vetri, V., Temussi, P.A., Pastore, A. Molecular Crowding: The History and Development of a Scientific Paradigm. Chem Rev 2024, 124, 3186-3219. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., Nagi, S.S., Usoskin, D., Hu, Y., Kupari, J., Bouchatta, O., Yan, H., Cranfill, S.L., Gautam, M., Su, Y., Lu, Y., Wymer, J., Glanz, M., Albrecht, P., Song, H., Ming, G.L., Prouty, S., Seykora, J., Wu, H., Ma, M., Marshall, A., Rice, F.L., Li, M., Olausson, H., Ernfors, P., Luo, W. Leveraging deep single-soma RNA sequencing to explore the neural basis of human somatosensation. Nat Neurosci 2024, Nov 4. [CrossRef]

| RNA as a Genetic Information Carrier | RNA Can Store Vertically Transmitted Genetic Information and Serve as a Template to Generate DNA. Plant RNA Can Modify DNA Through Methylation. |

|---|---|

| Noncoding RNAs | Over 95% of the genome encodes non-protein-coding RNAs, which play crucial roles in gene expression regulation, chromatin remodeling, and various cellular processes. |

| RNA diversity and biological complexity | RNA diversity, generated through alternative splicing, polyadenylation, and other means, underlies most intra- and interspecies diversity, influencing protein architecture and disease-linked variation. Antisense strand transcription of some genes and gene expression regulatory elements can generate RNAs and proteins. |

| RNA modifications | Various RNA modifications, including N6-methyladenosine (m6A), directly impact protein production and gene expression regulation, contributing to diverse biological processes and disease mechanisms. RNA editing allows the production of multiple proteins from one gene. |

| RNA’s extracellular roles | RNA can affect extracellular biology and pathology, such as glycoRNAs influencing immunity and pathogenesis, and RNAs transferred via extracellular vesicles affecting cell biology and interspecies interactions. |

| Prions and genetic information | Prions, infectious proteins that transmit genetic information without DNA mediation, add complexity to the central dogma by converting normal proteins into misfolded forms, leading to neurodegenerative diseases. |

| Epigenetic inheritance | Proteins can regulate DNA gene expression via transcription factors and histone modification, underlying epigenetic inheritance beyond genomic DNA inheritance, and affecting gene expression and phenotype. |

| Genetic mosaicism | Many organisms exhibit genetic mosaicism, where transpositions and mutations arising during cell division become fixed in daughter cells, potentially affecting tissue function and disease development. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).