Introduction

The ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remains the leading cause of death worldwide. In most cases, it is caused by an acute thrombosis over an atherosclerotic plaque, resulting in downstream vessel occlusion and subsequent death of cardiomyocytes. Here, we present an extremely rare case where acute plaque thrombosis occurs simultaneously in two coronary arteries, leading to a clinical picture of STEMI associated with unstable presentation of cardiogenic shock.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old male with a medical history of hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, and heavy smoking (approximately 3 packs per day) with pulmonary fibrosis was admitted to the emergency department following a two-day history of chest pain. On arrival, he was in cardiogenic shock.

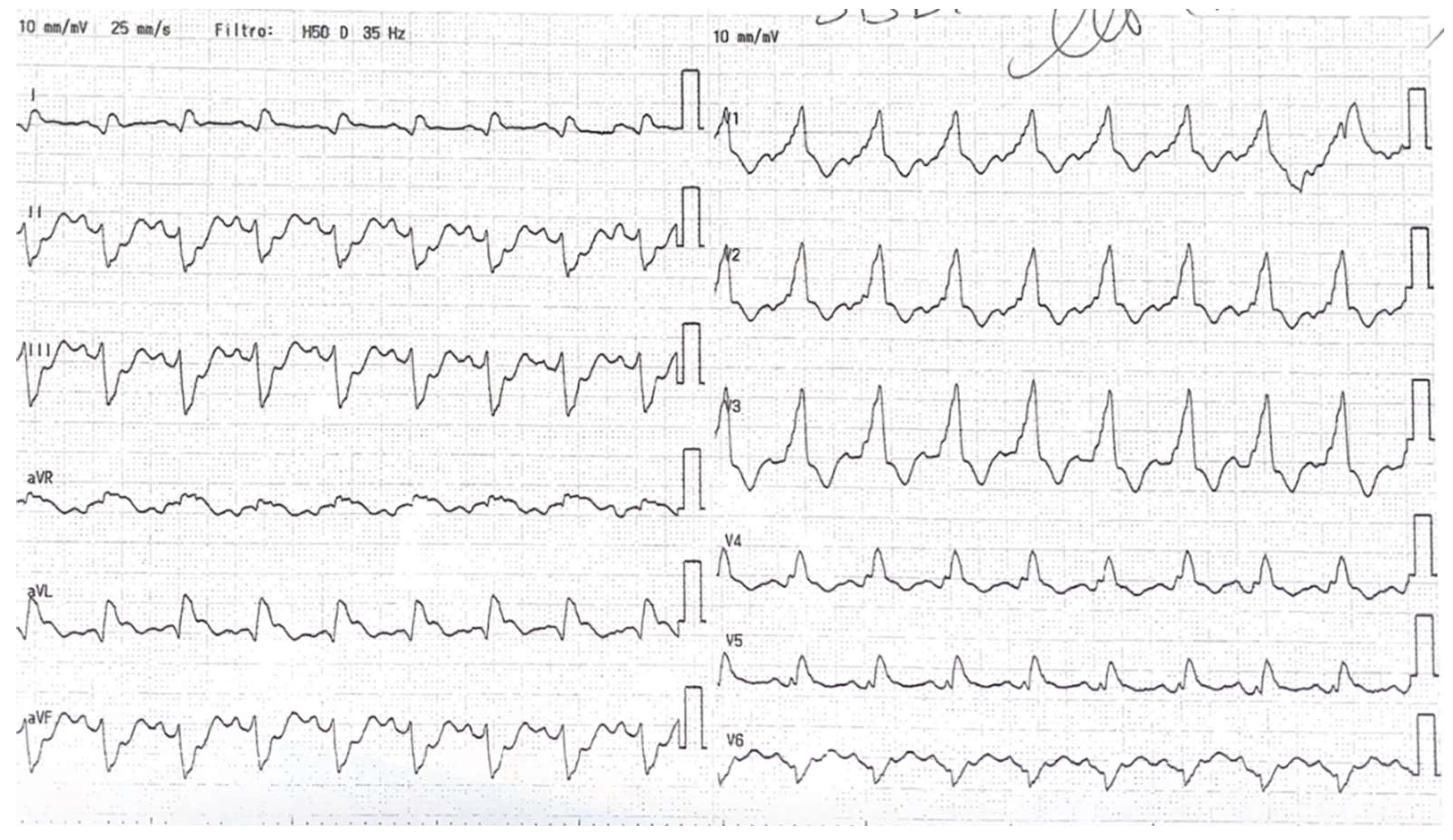

The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed significant ST-segment elevation in AVR and diffuse subendocardial ischemia, with ST elevation in lateral derivation and right bundle branch block as shown in

Figure 1. The echocardiogram demonstrated anterior and anterolateral akinesia, hypokinesia in the remaining segments, and normal septal contractility, which resulted in a severe reduction in ejection fraction (EF 20%) and mild-to-moderate mitral regurgitation. The emogas analysis showed metabolic acidosis with a slight increase of sierum lactates (lactates 4 mmol/L) and his systolic pressure was consistently below 90 mmHg.

Figure 1.

the ECG showing ST-elevation in AVR, avL and first derivation and right bundle branch block.

Figure 1.

the ECG showing ST-elevation in AVR, avL and first derivation and right bundle branch block.

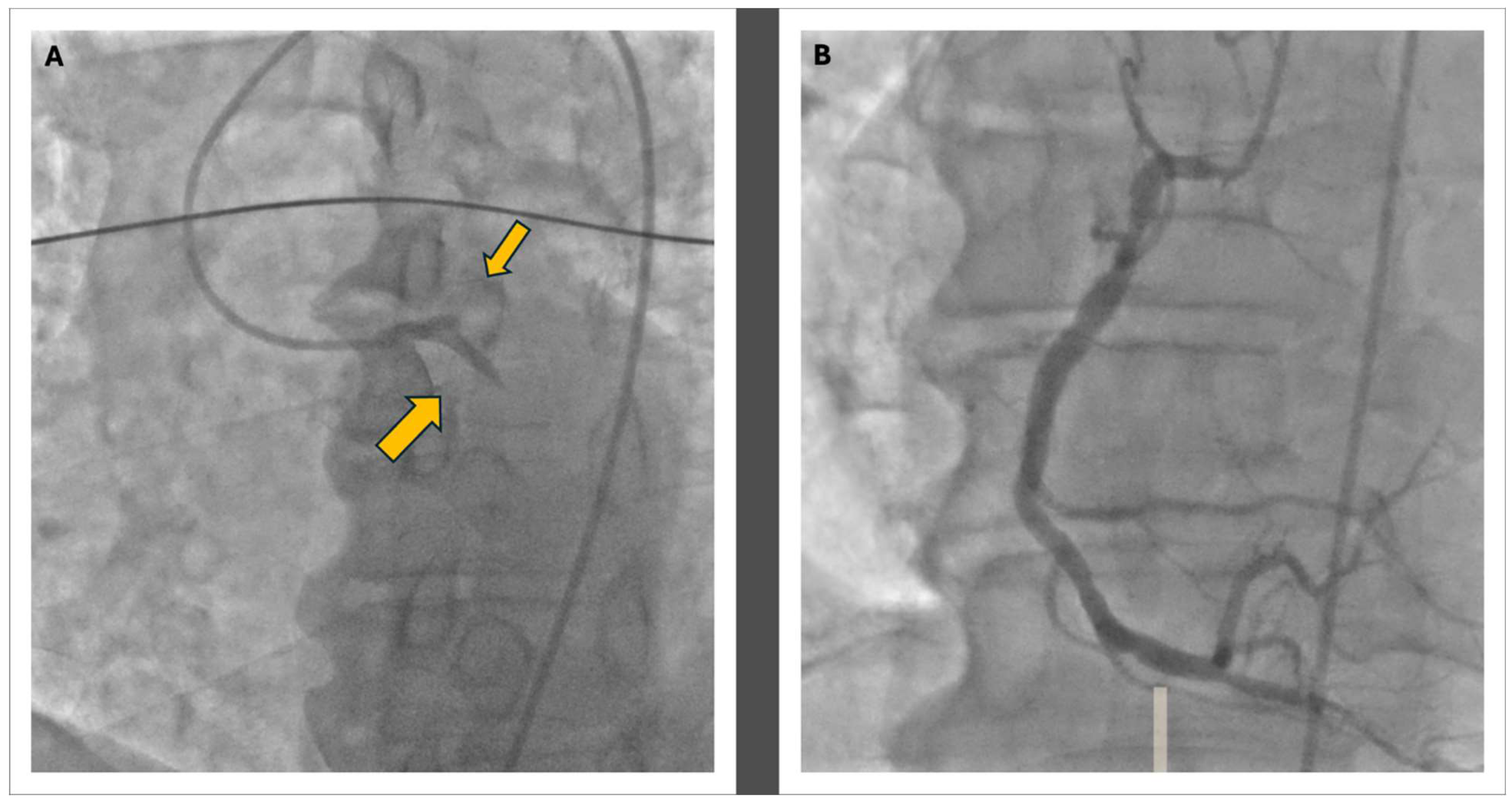

Figure 2.

The coronary angiography: Panel A shows the double thrombosis of the left coronary artery at the proximal level of the LAD and the CFX with a TIMI 0 in both vessels; in Panel B, the morphology of the right coronary artery is visible, displaying widespread atheromatous wall changes.

Figure 2.

The coronary angiography: Panel A shows the double thrombosis of the left coronary artery at the proximal level of the LAD and the CFX with a TIMI 0 in both vessels; in Panel B, the morphology of the right coronary artery is visible, displaying widespread atheromatous wall changes.

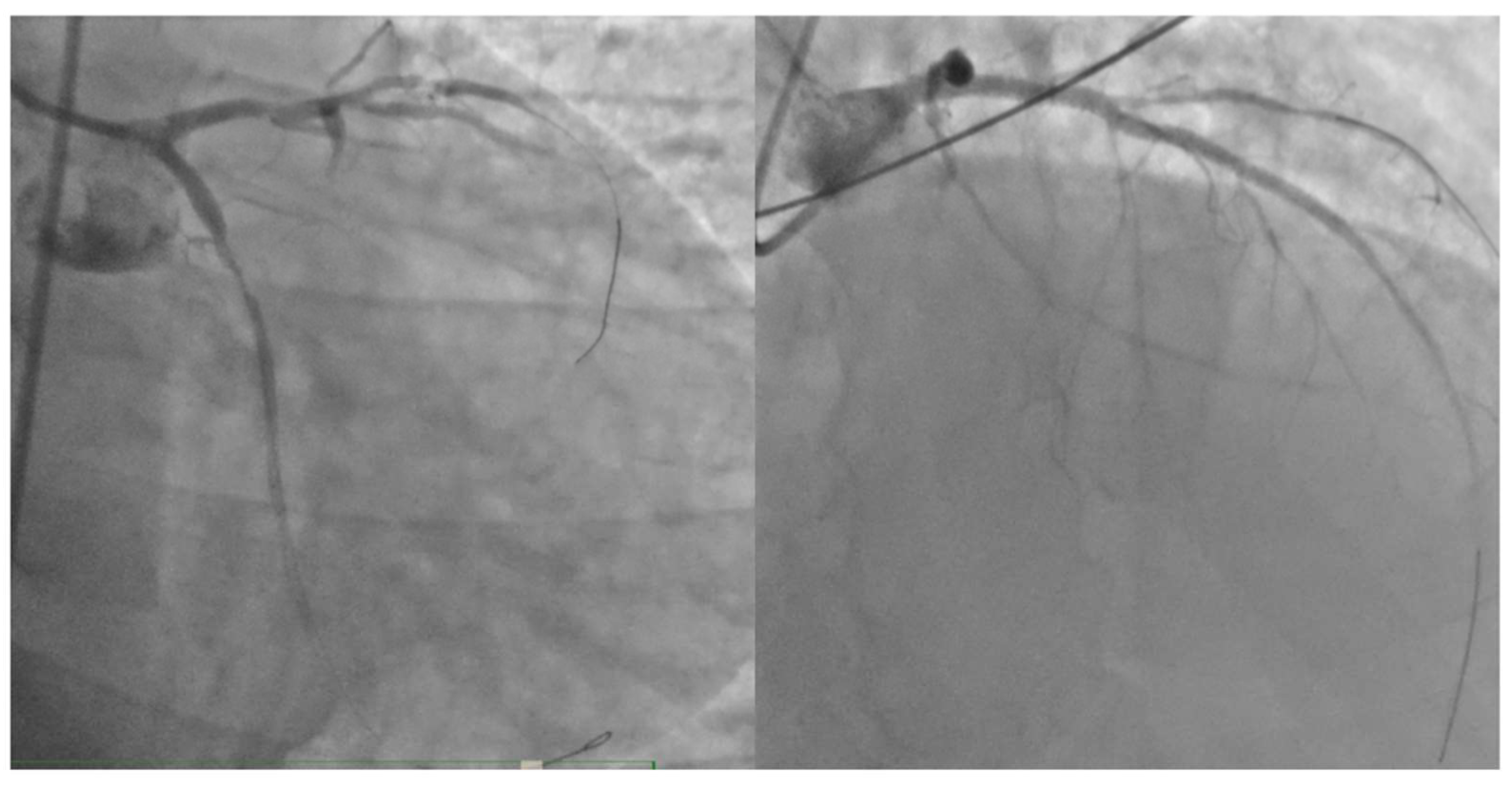

Figure 3.

the final results of percutaneous coronary intervention on left anterior discending artery and circumflex artery.

Figure 3.

the final results of percutaneous coronary intervention on left anterior discending artery and circumflex artery.

In response to the cardiogenic shock which led to severe hypotension, inotropic therapy with norepinephrine and dobutamine was initiated. The patient was then transferred to the catheterization lab, where acute subocclusion of the proximal circumflex branch and proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) was identified. Mechanical thrombus aspiration was performed through dual femoral access, and stents were placed in the proximal circumflex branch and proximal LAD. The distal LAD was treated with plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA). An intra-aortic balloon pump (IAPB) was also inserted to support hemodynamics. After the coronary angioplasty procedure, the patient was placed on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with acetylsalicylic acid and prasugrel. The final result was not optimal, but the vessels were open, as demonstrated in

Figure 3.The peak troponin value was 180,900 ng/L (reference range: 2.5-53 ng/L).

The patient was subsequently admitted to the intensive coronary care unit (CCU), where his stay was complicated by several issues. Initially he underwent oro-tracheal intubation and subsequently, due to difficulties in weaning from intubation given the severe pulmonary history, the patient underwent a tracheostomy.

Initially, he developed infections caused by various pathogens, leading to impaired gas exchange and necessitating orotracheal intubation. Pathogens were isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage and his x-ray and chest CT are shown in

Figure 2. The patient’s initial blood cultures were positive for

Staphylococcus capitis, followed by

Staphylococcus hominis, and were treated with vancomycin. Positive urine cultures for

Candida glabrata,

Candida albicans, and

Candida tropicalis were not treated. Oral candidiasis was treated with Mycostatin. Following the resolution of these infections, the patient again presented with a febrile condition, elevated inflammatory markers, and positive blood cultures for

Enterobacter cloacae, which was effectively treated with meropenem. Additionally, the patient developed severe bilateral pleural effusion, which required bilateral evacuative thoracentesis with drainage of serous fluid. He also experienced paralytic ileus, managed conservatively with the placement of a double-lumen nasogastric tube and parenteral nutrition. The patient’s nearly two-month stay in the CCU was marked by a challenging weaning process from orotracheal intubation and vasopressor support.

Moreover, during the intensive care stay, approximately 15 days after admission, the patient developed tetraparesis. A brain CT scan showed no signs of acute ischemic or hemorrhagic events, and electromyography revealed acute sensory-motor axonal polyneuropathy. During the hospitalization, this condition was managed with physiotherapy and corticosteroids, resulting in only a mild residual strength deficit in the left lower limb by the end of the treatment period.

Once the infectious issues were resolved, we attempted to strengthen our patient’s heart by administering two cycles of levosimendan approximately 25 days apart, using a low infusion dose due to marked hypotension. This approach was chosen because, according to serial echocardiograms, the systolic function was not improving, with an EF around 20%, and particularly because of the difficult weaning from inotropic support.

Despite rapid coronary revascularization, ongoing vasopressor support, and meticulous vessel care, the patient’s cardiac function did not improve and due to refractory heart failure leading to multiple pleural effusions, the patient was transferred to another center for evaluation of left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation after 2 months in our CCU. After the evaluation, the patient underwent LVAD implantation.

Discussion

Myocardial infarction is the result of ischemic necrosis of cardiomyocytes downstream of coronary artery obstruction. This obstruction can be either subocclusive or occlusive, leading to either transmural necrosis, known as STEMI, or affecting only the endocardial portion, resulting in a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Typically, the obstruction is caused by thrombosis over an atherosclerotic plaque and, in the vast majority of cases, affects a single vessel at a time. The advent of coronary angioplasty has dramatically changed the course of this condition. By restoring coronary blood flow in the affected artery within a short time frame, it is possible to limit ischemia-reperfusion injury, significantly impacting patient mortality and prognosis. Additionally, when only one vessel is involved, the ischemic and potentially necrotic area will be more confined, although it may still be extensive.

According to Pollak's data, published in 2015, males were significantly more affected by this rare condition, with smoking identified as the primary risk factor. The most common pattern of simultaneous occlusion involved the right coronary artery (RCA) and the circumflex artery (CFx), followed by occlusion of the right coronary artery and the left anterior descending artery. The least frequent scenario was the simultaneous occlusion of the two branches of the left coronary artery [

1].

This condition, being very rare, also presents a challenge in determining the appropriate management approach. Hage [

3], in a previous case report, emphasized the importance of intracoronary imaging to guide treatment; his case involved two culprit lesions, in both the RCA and LAD. After a failed thrombus aspiration on the LAD, they opted for a conservative approach, performing only an OCT 48 hours later. This imaging confirmed the presence of eroded plaques with small adherent thrombi, without significant stenosis. However, their case involved a hemodynamically stable patient, whereas our patient was in cardiogenic shock, and we needed to restore intracoronary flow as quickly as possible.

In the case reported by Jariwala, the dual thrombosis involved the proximal LAD and the distal RCA. In this scenario, the left ventricle retained some revascularization from the circumflex branches, and although the right coronary artery had a distal thrombosis, the patient still presented in cardiogenic shock with high-grade atrioventricular block that necessitated the placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump [

4] and PCI.

In the case described by Kuzemczak, similar to our reported case, the patient exhibited dual thrombosis in the LAD and the circumflex arteries, with a TIMI 0 flow observed in the proximal LAD and at the mid left circumflex artery, distally beyond the emergence of the first marginal branch. The patient experienced distress and tachycardia but was not in cardiogenic shock. Following PCI of both vessels without mechanical support, the patient was discharged without any adverse events after a week-long hospitalization [

5].

In the case reported by Fukaya, the dual thrombosis involved the proximal LAD with a TIMI 0 flow and the mid-distal circumflex artery. The patient was hemodynamically stable at presentation but became unstable during PCI and went into cardiogenic shock, necessitating the use of an intra-aortic balloon pump for circulatory support, similar to our case. The PCI was successfully completed by stenting both vessels. We do not have discharge data for this patient, but it is known that at the time of publication, the patient had a biplane ejection fraction of 60% and had not experienced any major events [

6]. The previous published case report are summarized in

Table 1.

Compared to previously reported cases, our patient presented in critical condition from the onset; he was in cardiogenic shock and significantly hypotensive. Additionally, our patient developed a newly diagnosed right bundle branch block (RBBB). According to data from a meta-analysis, new-onset RBBB in patients with myocardial infarction is an unfavorable prognostic factor, as it is associated with a higher risk of long-term mortality and cardiogenic shock [

7].

Moreover, compared with the two discussed previous patients, our patient, to our knowledge the first reported case, had a TIMI 0 flow on both the proximal LAD immediately after the left main trunk and on the proximal circumflex before the emergence of any marginal branch. This scenario was equivalent to a TIMI 0 flow at the level of the left main trunk; indeed, the ECG was quite typical of a left main trunk involvement with strongly positive AVR, despite the presence of a right bundle branch block.

In line with what is known in the literature, our patient also has a significant smoking history, which may suggest that smoking could play a role in the pathogenesis of this rare occurrence. However, our patient developed one of the rarest combinations, presenting with thrombosis of both the circumflex artery and the LAD.

This case report provides a point of reflection also on the approach to patients with STEMI ACS in the context of multivessel coronary artery disease.

The 2023 acute coronary syndrome (ACS) guidelines provide recommendations for revascularization in the case of non-culprit vessels. In hemodynamically stable STEMI cases, there is a Class I recommendation to revascularize the non-culprit either during the index procedure or within 45 days. However, in cases of cardiogenic shock, the Class I recommendation is to revascularize only the culprit lesion [

8].

Therefore, the guidelines do not provide explicit guidance for situations involving two different culprit lesions. In this case, we can assume that the primary culprit was the CX coronary artery lesion, which may have triggered the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and vasoconstrictive molecules. These factors likely contributed to the destabilization of a pre-existing plaque in the left LAD.

Nevertheless, since in an emergency situation it is very challenging to determine which of the two vessels was the initial culprit lesion that led to low cardiac output and subsequently caused acute thrombosis of the second culprit lesion, it may be reasonable to treat both culprit lesions if the patient stabilizes.

Moreover, the ACS 2023 guidelines recommend avoiding invasive procedures if the patient's symptoms have started more than 48 hours prior, and if the patient is asymptomatic [

8]. In our case, the patient's symptoms began two days before presentation, aligning with the 48-hour guideline threshold. However, given that the patient was still symptomatic upon arrival at the emergency department and presented in cardiogenic shock, we opted to proceed with PCI. During the procedure, we decided to revascularize both the circumflex artery and the LAD, prioritizing the patient's critical condition and the need for prompt intervention given that both the anterior septum and the posterolateral wall were not yet akinetic.

Self-critique. Our patient was transferred to a secondary care facility for evaluation for LVAD implantation, intended as a bridge to heart transplantation. Despite all efforts, including two months of hospitalization in the coronary intensive care unit after a double cycle of levosimendan, there was no improvement in left ventricular function. This lack of improvement could be attributed, at least in part, to certain decisions made during the treatment course. Notably, heart failure therapy was not fully optimized due to the patient’s unstable hemodynamic status; for example, beta-blocker therapy was maintained at very low doses following a brief episode of complete atrioventricular block. Implanting an ICD at that time might have allowed for more aggressive beta-blocker titration, but given the patient’s critical condition, we believe it was not the best option. Furthermore, after this short episode of total AV block, which lasted only a few minutes, the patient did not experience any recurrence. We initiated an aldosterone antagonist and valsartan with the aim of eventually introducing sacubitril/valsartan. However, this could not be achieved due to the patient's persistent hypotension, which prevented the transition to this combination therapy.

Retrospectively, there was a discussion within our team regarding the possibility of using an alternative circulatory support system. There is a lack of substantial evidence regarding which circulatory support device is the most effective on survival rate. On one hand, in the IABP-SHOCK II trial, the routine use of IABP in patients with ACS and cardiogenic shock did not reduce 30-day, 1-year, or 6-year mortality [

9]. On the other hand, the randomized trials ISAR-SHOCK [

10] and IMPRESS [

11] compared the use of IABP and Impella (specifically Impella 2.5 and CP) in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock, demonstrating the absence of statistically significant differences in mortality between the two groups (at 30 days and at 6 months, respectively), albeit at the cost of a higher rate of bleeding in patients treated with Impella. The timing for the implantation of the support device differed between the two studies. In ISAR-SHOCK, the device was implanted following coronary revascularization, while in IMPRESS, the decision regarding when to implant the device was left to the operator's judgment, allowing for implantation before, after, or during primary PCI. Recently, findings have indicated the benefits of the systematic and timely implantation of the Impella device in patients experiencing acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock, implemented before revascularization procedures and prior to administering inotropes and vasopressors [

12]. However, in the case of our patient, with the entire left coronary artery occluded, there was no way to wait to position the Impella before reopening the vessel; therefore, we preferred to initiate positive inotropic therapy, reopen the two occluded vessels, and subsequently opted to place the intra-aortic balloon pump.

Conclusion

This rare case of simultaneous thrombosis in two coronary arteries leading to STEMI and cardiogenic shock underscores the complexities of management in such patients. Further research is needed to optimize revascularization strategies and improve outcomes, highlighting the importance of a tailored and multidisciplinary approach in critical cases.

List of Table

References

- Pollak, P. M., Parikh, S. V, Kizilgul, M. & Keeley, E. C. Multiple culprit arteries in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction referred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. J. Cardiol. 104, 619–623 (2009).

- Saito, R., Koyama, K., Kongoji, K. & Soejima, K. Acute myocardial infarction with simultaneous total occlusion of the left anterior descending artery and right coronary artery successfully treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 1–9 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Hage, G. et al. Double Culprit Lesions in a Patient With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Should I Stent or Should I Go? JACC. Case reports vol. 3 1906–1910 (2021).

- Jariwala, P., Hospital, Y., Pramod, G. & Hospital, Y. “ Double Myocardial Infarct Syndrome ” resulting from Simultaneous Occlusion of Dual Coronary Arteries : A Double Jeopardy “ Double Myocardial Infarct Syndrome ” resulting from Simultaneous Occlusion of Dual Coronary Arteries : A Double Jeopardy. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kuzemczak, M., Kasinowski, R. & Skrobich, P. A Successfully Treated STEMI Due to Simultaneous Thrombotic Occlusion of Left Anterior Descending Artery and Left Circumflex Artery : A Case Report and Review of the Literature. 9, 395–399 (2018).

- Fukaya, H. et al. Acute myocardial infarction involving double vessel total occlusion of the left anterior descending and left circumflex arteries: A case report. Journal of cardiology cases vol. 4 e1–e4 (2011).

- Wang, J. et al. Prognostic value of new-onset right bundle-branch block in acute myocardial infarction patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 6, e4497 (2018).

- Task, A. et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes Developed by the task force on the management of acute coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology ( ESC ) ( United Kingdom ), ( United Kingdom ),. 1–107 (2023).

- Olbrich, H. et al. new england journal. 1287–1296 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Seyfarth, M. et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 1584–1588 (2008).

- Karami, M. et al. Long-term 5-year outcome of the randomized IMPRESS in severe shock trial: percutaneous mechanical circulatory support vs. intra-aortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Hear. journal. Acute Cardiovasc. care 10, 1009–1015 (2021).

- Basir, M. B. et al. Effect of Early Initiation of Mechanical Circulatory Support on Survival in Cardiogenic Shock. Am. J. Cardiol. 119, 845–851 (2017).

- Mahorkar, A. V, Mahorkar, V. U., Mahorkar, U. K., Vidhale, A. A. & Sarwale, S. J. A tale of two culprits : a case report. 10, 734–736 (2023).

- Kanei, Y., Janardhanan, R., Fox, J. T. & Gowda, R. M. Multivessel coronary artery thrombosis. J. Invasive Cardiol. 21, 66–68 (2009).

- Marchi, E., Muraca, I., Cesarini, D., Pennesi, M. & Valenti, R. Double coronary artery occlusion presenting as inferior ST segment elevation myocardial infarction and Wellens syndrome type A: a case report. Eur. Hear. J. - Case Reports 8, ytae394 (2024).

Table 1.

The lists of published cases, with the mode of presentation, the treatment, and the outcome.

Table 1.

The lists of published cases, with the mode of presentation, the treatment, and the outcome.

| Author and year |

Type of ACS |

Presentation |

Outcome |

Vessels |

Treatment |

| Mahorkar AV et al., 2023 [13] |

Infero-posterior |

Severe hypokinesia, ejection fraction 30%, symptoms of infero-posterior wall MI |

Discharged on day 5 in stable condition |

Distal RCA, LCx |

Drug-eluting stents, PTCA for RCA and LCx |

| Kanei et al., 2009 [14] |

Inferior STEMI |

Cardiogenic shock |

|

RCA, LAD |

Intra-aortic balloon pump, thrombectomy, PCI with DES to RCA and LCx |

| Fukaya et al., 2011 [6] |

Anterolateral STEMI |

Haemodinamically stable, FE 60% |

No data |

LAD, LCx |

Intra-aortic balloon pump, PCI with DES |

| Kuzemczak et al., 2018 [5] |

STEMI due to simultaneous occlusion of LAD and LCx, rapid clinical course |

Haemodynamically stable, but very sofferent |

Discharged in stable condition |

LAD, LCx |

PCI with DES |

| Pankaj Jariwala et al., 2023 [4] |

Inferior STEMI |

Cardiogenic shock with with 2:1 atrio-ventricular block |

|

Proximal LAD and RCA |

IAPB, PCI with DES |

| Hage et Al., 2021 [3] |

Anterior and inferior STEMI |

Haemodinamically stable |

Discharge in stable conditions |

Proximal LAD and mid RCA |

Failed PCI in LAD and medical treatment in RCA |

| Marchi ed Al. 2024 [15] |

Inferior STEMI and Wellens type A |

Hypotensive |

Discharge in stable conditions |

Proximal RCA and mid LAD |

PCI |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).