Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- C: set of convex functions of .

- N: set of normal functions of .

- L: set of both convex and normal functions of .

- K: functions of N, whose images are 0 or 1 (but not all 0).

- : functions of K whose support is a finite union of closed intervals. In the notation , c stands for close and F for finite.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Some Types of Fuzzy Sets and Operations

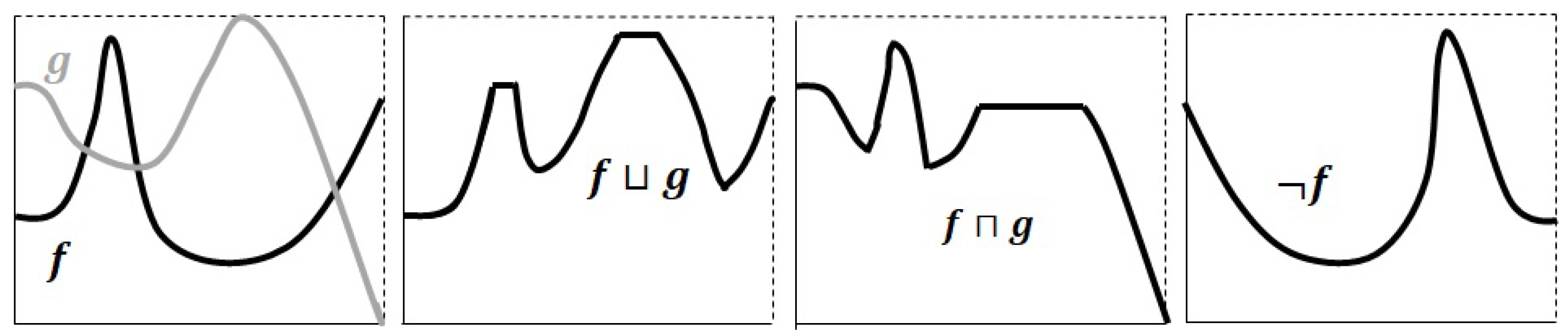

- The two partial orders ⊓ and ⊔ do not generally coincide.

- , and so , for all , that is, is the largest element of the partial order ⊑.

- , and then , for all , that is, is the smallest element of the partial order ⪯.

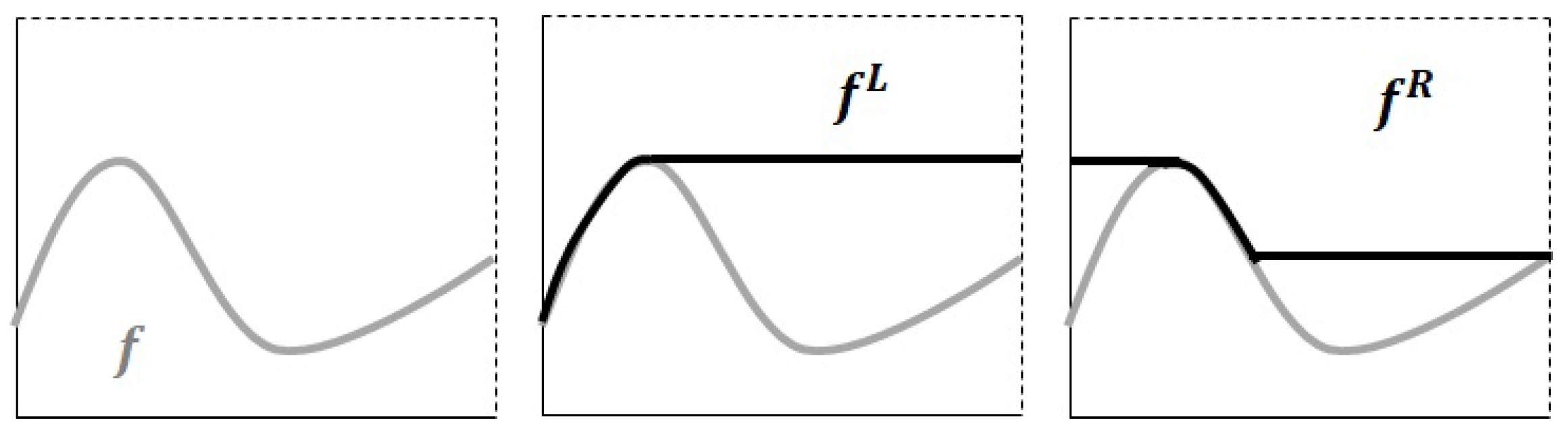

- and are monotonically increasing and decreasing, respectively (see for example Figure 2).

- and where ≤ is the usual pointwise order in the set of functions ( if and only if for all ).

- and .

- If we define and , the next assertion holds:

2.2. T-Norms and t-Conorms on Bounded Posets

- for all (commutativity),

- for all (associativity),

- , for all (neutral element),

- Let such that , then (monotony).

- 3’.

- ,

- The minimum t-norm and the maximum t-conorm .

- The product t-norm and the probabilistic sum .

- The drastic t-norm and the drastic t-conorm:

- ▴ and ▾ are commutative and associative in .

- , , and for all .

- , for all where .

- for all .

- for all .

-

and for all.

- Given , such that , then:

- , for all .

- For all such that and :

- If , then:

- ▴ and ▾ are closed onM,C,N, andL .

- ▴ and ▾ are t-norms and t-conorms, respectively, on the lattice .

3. T-norms and t-conorms on M, C, N, L, K and .

3.1. The Operations ▴ and ▾ on M, C, N, K and .

- if and only if , , and , for all .

- if and only if , , and , for all .

3.2. The Operations ⊥ and ⊤ on M, C, N, L, K and .

- ⊥ and ⊤ are equivalent to ▴ and ▾, respectively, on . If , then and (see [37]). Moreover since and for all , we can state that , on . Consequently, Proposition 4 provides counterexamples where ⊥ and ⊤ are neither t-norm nor t-conorm with respect to either order ⊑ or ⪯ onC, and therefore onM .

- Since and as a consequence of the previous point, ⊥ and ⊤ are also equivalent to ▴ and ▾, respectively, on . It was proven in [18] that ▴ (▾) is t-norm (t-conorm) on (L, ⊑, , ) so ⊥ (⊤) is also t-norm (t-conorm).

-

If or we can find examples where and . Let us consider the function:We have that , , but , and . Consequently, ⊥ and ⊤ are not equivalent in general to ▴ and ▾ onN,Kor .

- ii)

- for all .

- iii)

- for all .

- ii)

- For all , we have that . Hence:and the desired property is proven.

- iii)

- The proof is analogous to the previous one.

- i)

- ii)

- ii)

- By Proposition 7 i), if , then and . Once again, by Theorem 3, we know that ▴ and ▾ are closed operations on L so the result is verified.

- .

- .

- i)

- The operation ⊥ is increasing in each argument on , and .

- ii)

- The operation ⊤ is increasing in each argument, on , and .

- If all functions and h are different from , by Proposition 11 we have:

- If , since and g is the maximum, then . Thus, .

- If , then

-

Finally, let us see the case in which and . Here, and . As a consequence, it is sufficient to prove that:As , from Proposition 11 and Theorem 3:Let us check that . By Theorem 1 the inequality:must hold. According to Proposition 7, this inequality is equivalent towhich trivially holds. Then, ⊥ is increasing on each argument on . Consequently, it is also increasing in each argument on and .

- i)

- ⊥ is a t-norm on , and , with neutral element and absorbent element .

- ii)

- ⊤ is a t-conorm on , and , with neutral element and absorbent element .

4. Concluding Remarks

- The operator ▴, with and , is neither increasing with respect to ⊑ nor with respect to ⪯ on M, N, K and .

- The operator ▾, with and is neither increasing with respect to ⊑ nor with respect to ⪯ on M, N, K and .

- The operator is t-norm on M, C, N, K and with respect to ⊑.

- The operator is t-conorm on M, C, N, K and with respect to ⪯.

- In general, the operators ▴, ▾, ⊥ and ⊤ are neither t-norm nor t-conorm, on C with respect to either ⊑ and ⪯.

- The operator ⊥ is t-norm on N, L, K and with respect to the order ⊑. Moreover, on C.

- The operator ⊤ is t-conorm on N, L, K and with respect to the order ⪯. Moreover, on C.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FS | Fuzzy set |

| IVFS | Interval-Valued Fuzzy Set |

| T2FS | Type-2 Fuzzy Set |

| IT2FS | Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Set |

| T2FLS | Type-2 Fuzzy Logic System |

References

- H. Bustince, E. H. Bustince, E. Barrenechea and M. Pagola, “Generation of interval-valued fuzzy and Atanassov’s intuitionistic fuzzy connectives from fuzzy connectives and from Kα operators. Laws for conjunctions and disjunctions. Amplitude”, Internat. J. Intell. Syst., vol. 23, pp. 680–714, 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Bustince, J. H. Bustince, J. Fernandez, H. Hagras, F. Herrera, M. Pagola and E. Barrenechea, “Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Sets are Generalization of Interval-Valued Fuzzy Sets: Toward a Wider View on Their Relationship”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 1876–1882, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Bustince, E. H. Bustince, E. Barrenechea, M. Pagola, J. Fernandez, Z. Xu, B. Bedregal, J. Montero, H. hagras, F. Herrera and B. De Baets, B. (2015). A historical account of types of fuzzy sets and their relationships. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2015; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Baets, B. , Mesiar, R.: Triangular norms on product lattices. Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 104, 61–75 (1999). [CrossRef]

- De Cooman, G. , Kerre, E.: Order norms on bounded partially ordered sets. Journal Fuzzy Mathematics, 2, 281–310 (1994).

- S. Coupland, M. S. Coupland, M. Gongora, R. John, and K. Wills, “A comparative study of fuzzy logic controllers for autonomous robots”, in Proc. IPMU, Paris, France, Jul. 2006, pp. 1332–1339.

- S. Coupland and R. John, “A fast geometric method for defuzzification of type-2 fuzzy sets”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 929–941, 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Coupland and R. John, “Fuzzy logic and computational geometry”, in Proceedings of RASC 2004, Nottingham, England, 2004, pp. 3–8.

- S. Coupland and R. John, “Geometric type-1 and type-2 fuzzy logic systems”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 15, no.1, pp.3–15, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gera and J. Dombi, “Exact calculations of extended logical operations on fuzzy truth values”, Fuzzy Sets Syst., vol. 159, no. 11, pp. 1309–1326, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, M. , Walker, C., Walker, E.: Some comments on interval-valued fuzzy sets. Internat. J. Intell. Systems, 11, 751–759 (1996).

- J. Goguen, “L-fuzzy sets”, J. Math. Anal. Appli., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 623–668, 1967.

- J. Harding, C. J. Harding, C. Walker and E. Walker, “Convex normal functions revisited”, Fuzzy Sets Syst., vol. 161, pp. 1343–1349, 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Harding, C. J. Harding, C. Walker and E. Walker, “Lattices of convex normal functions”, Fuzzy Sets Syst., vol. 159, pp. 1061–1071, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, P. , Cubillo, S., Torres-Blanc, C.: A Complementary Study on General Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Sets. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 30 (11), 5034–5043 (2022). [CrossRef]

- P. Hernández, S. P. Hernández, S. Cubillo and C. Torres-Blanc, “Negations on type-2 fuzzy sets”, Fuzzy Sets Syst., vol. 252, pp. 111–124, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, P. , Cubillo, S., Torres-Blanc, C.: Nuevas operaciones binarias sobre los conjuntos borrosos de tipo 2, en: Actas Multiconferencia CAEPIA 2013, 1250–1259 (2013).

- P. Hernández, S. P. Hernández, S. Cubillo and C. Torres-Blanc, “On t-norms on type-2 fuzzy sets”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 1155–1163, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Klement, P. , Mesiar, R., Pap, E.: Triangular Norms. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands (2000).

- Q. Liang and J.M. Mendel, “Interval type-2 fuzzy logic systems: theory and design”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 535–550, 2000. [CrossRef]

- O. Linda and M. Manic, “General type-2 fuzzy C-means algorithm for uncertain fuzzy clustering”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 883–897, 2012. [CrossRef]

- O. Linda and M. Manic, “Monotone centroid flow algorithm for type reduction of general type-2 fuzzy sets”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 805–819, 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Liu, “An efficient centroid type-reduction strategy for general type-2 fuzzy logic system”, Inf. Sci., vol. 178, pp. 2224–2236, 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. Mendel and R. Jhon, “Type-2 fuzzy sets made Simple”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 117–127, 2002. [CrossRef]

- J. Mendel, F. J. Mendel, F. Liu, and D. Zhai, “α-plane representation for type-2 fuzzy sets: theory and applications”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1189–1207, Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Mendel, R. I. J. M. Mendel, R. I. John and F. Liu, “Interval type-2 fuzzy logic systems made simple”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 808–821, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Menger, K. : Statical metrics. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 37, 535-537 (1942).

- M. Mizumoto and K. Tanaka, “Fuzzy sets of type-2 under algebraic product and algebraic sum”, Fuzzy Sets Syst., vol. 5, pp. 277–290, 1981. [CrossRef]

- M. Mizumoto and K. Tanaka, “Some properties of fuzzy sets of type-2”, Inf. Control, vol. 31, pp. 312–340, 1976.

- A. Niewiadomski, “On finity, countability, cardinalities, and cylindric extensions of type-2 fuzzy sets in linguistic summarization of databases”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 532–545, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Ray, “Representation of a Boolean algebra by its triangular norms”, Mathware and Soft Computing, vol. 4, pp. 63–68, 1997.

- G. Ruiz-García, H. G. Ruiz-García, H. Hagras, I. Rojas and H. Pomares, “Towards a Framework for Singleton General Forms of Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Systems”, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 3–26, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, B. , Sklar, A.: Associative functions and statistical triangle inequalities. Publ. Math., 8, 169–186 (1961).

- Schweizer, B. , Sklar, A.: Statistical metric spaces. Pacific J. Math., 10, 313–334 (1960).

- C. Wagner and H. Hagras, “Toward general type-2 fuzzy logic systems based on zSlices”, IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 637–660, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. Walker and E. Walker, “Some general comments on fuzzy sets of type-2”, Internat. J. Intell. Syst., vol. 24, pp. 62–75, 2009.

- C. Walker and E. Walker, “The algebra of fuzzy truth values”, Fuzzy Sets Syst., vol. 149, pp. 309–347, 2005.

- Walker, C. , Walker, E.: T-norms for type-2 fuzzy sets. In: Proc. Internat. Conf. on Fuzzy Systems IEEE 2006, pp. 1235–1239, –21, Vancouver (Canadá) (2006). 16 July. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu and G. Chen, “Answering an open problem on t -norms for type-2 fuzzy sets”, Inform. Sci., vol. 522, pp. 124–133, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X.Wu, G. X.Wu, G.Chen and L.Wang, “On union and intersection of type-2 fuzzy sets not expressible by the sup-t-norm extension principle”, Fuzzy Sets Syst., vol. 441, pp. 241–261 (2022). [CrossRef]

- L. Zadeh, “Fuzzy sets”, Inf. Control, vol. 20, pp. 301–312, 1965.

- L. Zadeh, “The concept of a linguistic variable and its application to approximate reasoning-I”, Inf. Sci., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 199–249, 1975. [CrossRef]

- L. Zadeh, “The concept of a linguistic variable and its application to approximate reasoning-II”, Inf. Sci., vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 301–357, 1975. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).