1. Introduction

Demotivation and disengagement (D&D) are persistent issues in education, impacting various initiatives and courses. These problems can hinder learning, cause delays, increase workload, and lead to dissatisfaction and dropouts. They can also affect initially motivated and engaged students [

1][

2].

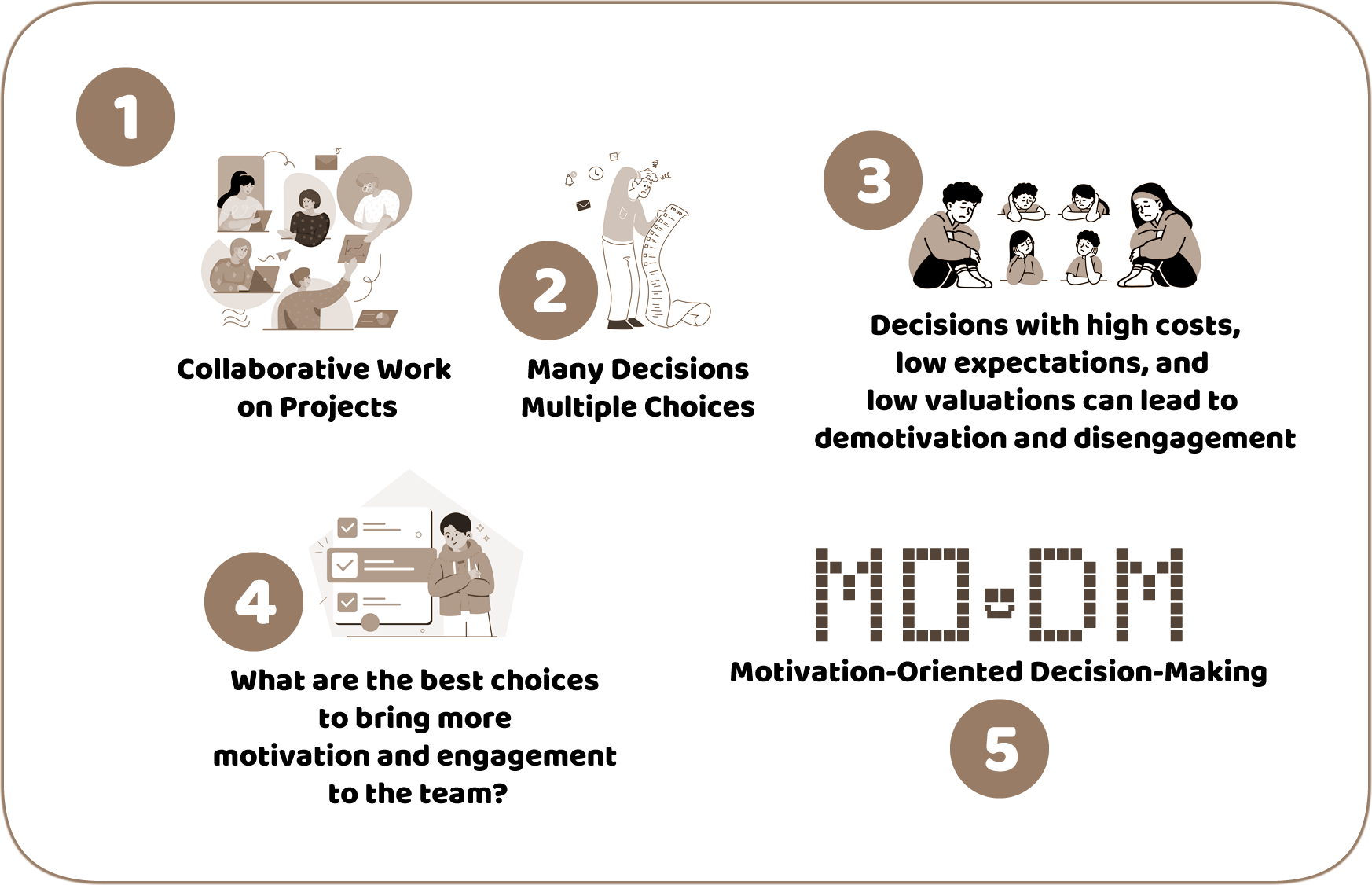

A doctoral study was conducted with undergraduate students from the Informatics Center at one of Brazil’s top five universities for computing courses. The research aimed to identify and understand the main causes of D&D in a setting where students work in teams on technology-based innovative projects.

The students involved were part of a multidisciplinary education initiative called Projetão, which is included in the Computer Science course curriculum at the institution. This open discipline attracts students from various fields to create technological solutions for real-world problems and market them. Participants primarily come from Computer Science and Computer Engineering but also include students from other courses, like Physics, Biology, Design, Administration, and Psychology, among others, totaling around 100 students each semester.

The study found that the decision-making process within teams is the main source of demotivation and disengagement. Students often make high-cost, undervalued decisions with low execution expectations for some team members. These decisions accumulate throughout the project, adversely affecting motivation and engagement.

This paper discusses that problem and presents a model and tool, called MO-DM (Motivation-Oriented Decision-Making), as a solution, promoting a new way of evaluating and prioritizing options when deciding, fostering more informed and fruitful discussions among students to enhance their motivation and engagement.

1.1. Innovation Education (EI)

It was within the context of Innovation Education (EI) that the problem was initially detected. EI lacks a consensus definition but is seen as a driver of change, linked to invention and creativity. Rogers [

3] defines innovation as something perceived as new. The EI has gained significant academic attention, with publications increasing from 1,096 to 6,728 between 2012 and 2023, considering the total result amount from bases like IEEE, ACM, Google Scholar, Springer, and Academia.edu, together [

21].

EI is described as essential for preparing students for the future, stimulating necessary skills, and contributing to regional development [

4][

5]. It involves constant decision-making, using approaches like Design Thinking, which emphasizes collaborative, human-centered problem-solving. This process is divided into two phases: exploring problems and finding solutions, each with divergent and convergent stages, known as the double diamond process [

6].

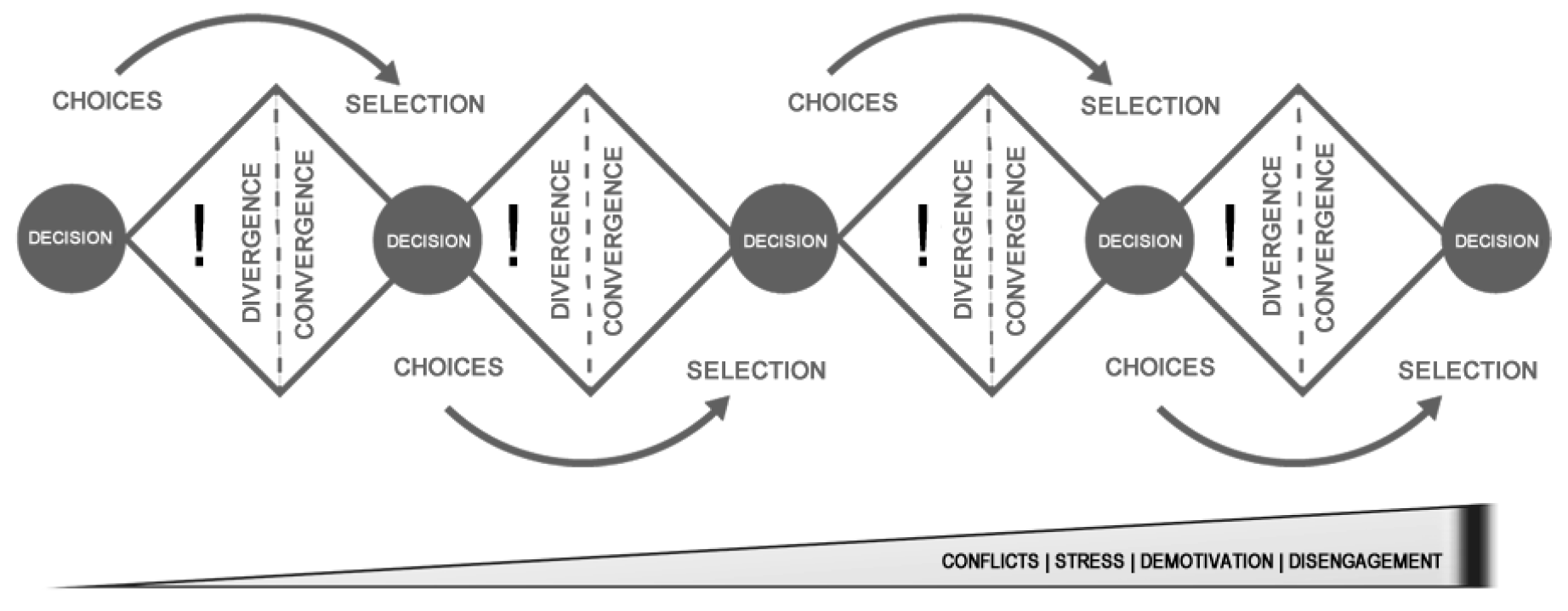

However, frequent decision-making, passing through a lot of divergent phases (

Figure 1), can lead to conflict, stress, demotivation, and disengagement, requiring careful management to ensure effective innovation education [

7].

1.2. Demotivation and Disengagement (D&D)

Demotivation in education refers to a lack of interest and foundation in learning, negatively impacting a student’s drive [

8]. Disengagement means low involvement in learning activities [

9]. Both factors significantly affect learning outcomes [

10]. Motivation and engagement are interdependent; without motivation, there is no engagement, and vice versa. Unmotivated students may disengage, and disengaged students may become unmotivated [

10].

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by Deci and Ryan [

1] explains these behaviors and is widely supported in education, business, and industry. Research indicates that motivation and engagement are critical factors

1 for student success, affecting satisfaction and psychological well-being, and reducing dropout rates [

11][

12].

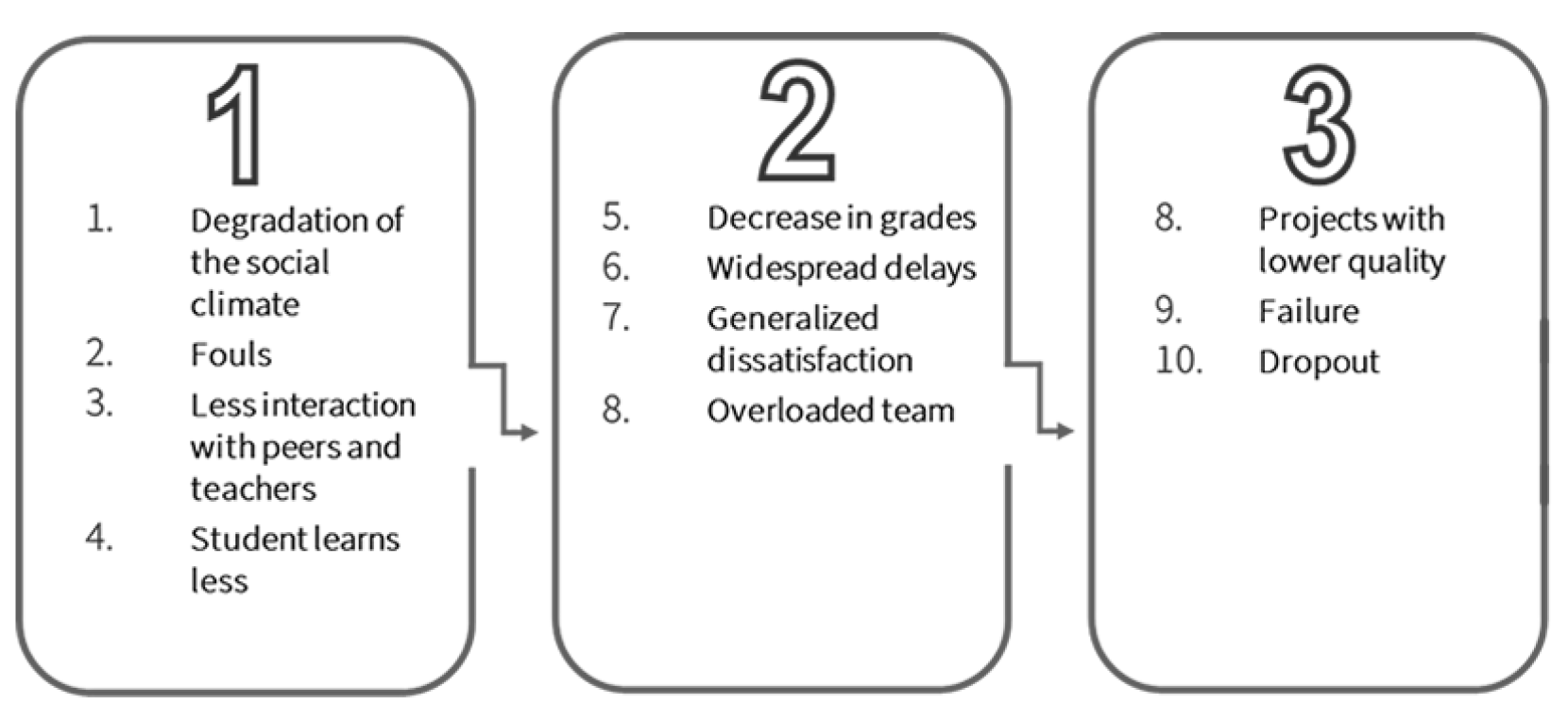

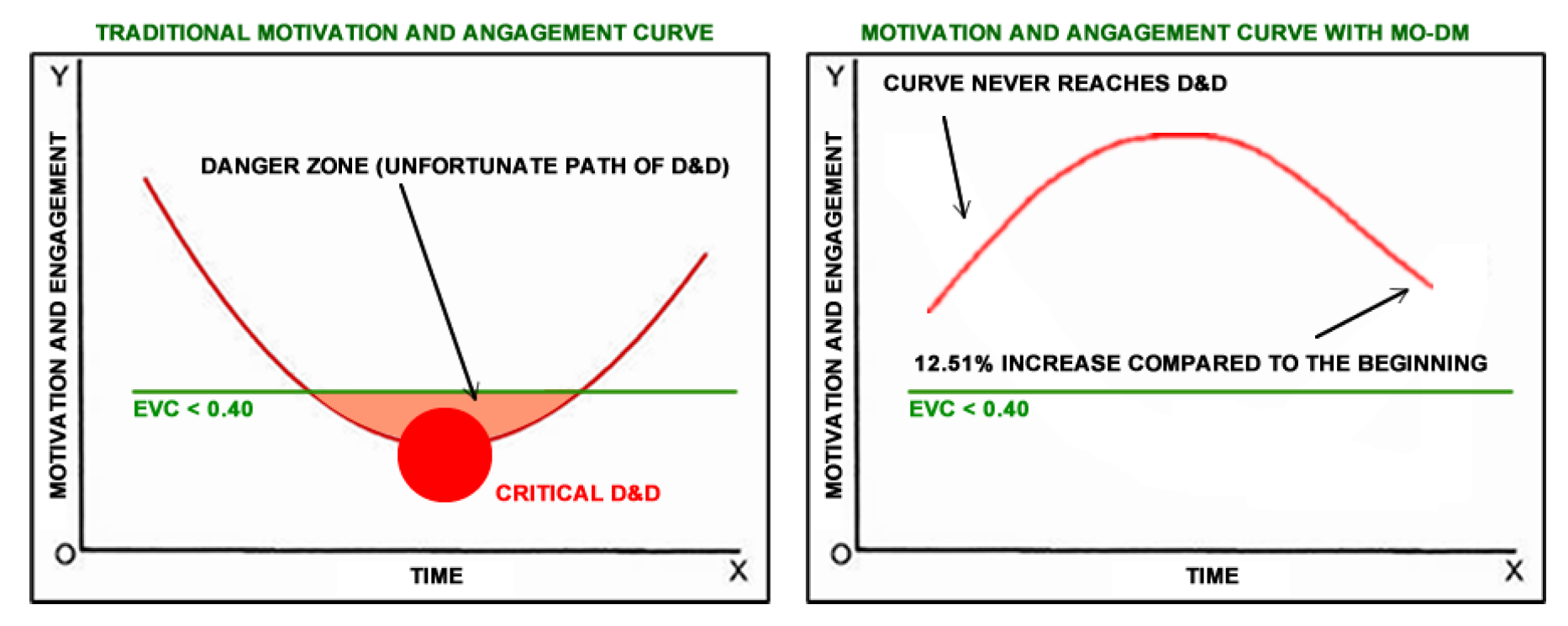

Demotivation and disengagement are relevant topics because they imply an extremely harmful path to student learning, here called the Unfortunate Path of D&D (

Figure 2), that shows the negative effects that these problems cause for any education initiative.

Addressing demotivation and disengagement is vital for improving educational outcomes by understanding and mitigating their triggers [

13].

1.3. Decision-Making

Decision-making involves selecting among options, either individually or collectively and is integral to the functioning of teams. In group settings, decisions often rely on unanimity or majority voting, with the latter being more prevalent due to its perceived democratic nature [

14]. However, this approach has been criticized for overlooking essential factors such as costs and the expectations of all involved parties [

15].

Numerous studies [

15] have highlighted flaws in the majority voting system, suggesting that it can lead to the neglect of better options and overlook the impacts of decisions, particularly on minority groups within teams. This oversight can have detrimental effects on innovation and team cohesion, ultimately affecting project outcomes.

Furthermore, decision-making is intricately linked to team motivation and engagement. Constant decision-making can generate conflicts and costs, making it one of the most critical processes for teams working on innovative projects [

16]. Effective decision-making requires constant monitoring and adjustment to avoid costly errors, especially within EI initiatives where time constraints are prevalent [

17].

Given its significant impact on project success, decision-making processes within teams have garnered substantial attention from academia and industry alike [

18]. Understanding the complexities of decision-making and its implications is crucial for optimizing team performance and project outcomes.

1.4. Expectancy-Value-Cost (EVC)

The solution proposed in this article is based on EVC. The EVC theory, a refined version of the Expectancy-Value Theory by Eccles [

19], elucidates three crucial variables: expectancy (E), value (V), and cost (C); which significantly shape motivation and engagement in individuals’ decision-making processes. These elements collectively influence one’s inclination to undertake a particular task.

In more complex projects characterized by heightened uncertainty, such as innovation projects, students are more likely to discern the cost dimension over other attributes[

20]. Literature suggests that costs hold the greatest influence, constituting 40% of motivation and engagement, compared to 30% each for expectancy and value [

21].

Despite its wide-ranging applicability, particularly in the realm of social sciences, there remains a paucity of research delving into its relevance within innovation and education spheres, according to Soleas [

22], a prominent researcher in this field. Recognizing the profound impact of these factors, it is imperative to explore their implications in educational contexts.

It is important to highlight that the EVC makes it possible to evaluate the phenomena of motivation and engagement jointly. There are other tools, such as the AMS (Academic Motivation Scale), for assessing motivation; and the SCEQ (Student Course Engagement Questionnaire) to assess engagement, for example. For comparison purposes, a complementary study was carried out with technology students showing that the results obtained by the EVC and these two other resources are quite similar, with a Pearson correlation score of 0.9886, between the EVC and the SCEQ, and a score of 0.9942 between EVC and AMS, meaning strong positive correlations.

Various instruments, such as the Expectancy-Value-Cost Scale proposed by Kosovich et al. [

23], have been developed to quantitatively measure student motivation and engagement. Moreover, the EVC theory has found practical applications in diverse domains, including the design of AI agents to optimize decision-making processes, through reducing costs; and predictive analytics in educational settings to gauge student performance and motivation.

Despite its wide-ranging applications, there remains a notable gap in the literature regarding the utilization of EVC theory in facilitating collaborative decision-making among multidisciplinary student teams. However, given its efficacy in assessing motivation and engagement, it holds promise for guiding decision-making processes in such contexts.

1.5. Projetão

Projetão, an educational initiative within the Computer Science curriculum at a prestigious Brazilian university, has been fostering innovation since its inception in 2003. Over two decades, it has influenced more than 2500 students and facilitated the creation of over 150 innovation projects and 50 startups. Operating as a multidisciplinary framework, it extends beyond the confines of its home institution, reaching other educational centers and partnering with technology hubs like Porto Digital in Recife.

The essence of Projetão lies in its project methodology, emphasizing innovation through ten sequential stages termed "quests." These quests guide students through problem identification to the delivery of innovative technological solutions. While primarily attracting students from Computer Science and Engineering, its inclusive nature encourages participation from diverse academic backgrounds, enriching a collaborative and multidisciplinary environment.

Despite its local roots, Projetão resonates with global trends in innovation education. A comprehensive review of similar initiatives worldwide highlights striking parallels in teaching techniques, methodologies, and demographic characteristics, with a Pearson Correlation Coefficient

2, for numerical data, of 0.9541 (very strong). The statistical correlation underscores the program’s relevance and effectiveness, suggesting potential for broader adoption and adaptation.

The course isn’t devoid of challenges. This work indicates a concerning trend of D&D, with nearly a quarter (25.9%) of students demotivated and disengaged. Additionally, a dropout rate of 17% underscores the need for ongoing refinement and improvement. Decision-making predominantly relies on a majority vote system, indicating room for adopting the MO-DM model.

The results described in this paper were obtained after a four-year analysis, initiated in 2019, of Projetão. Considering its regional significance, tangible outcomes, and alignment with global counterparts, there is great potential for replication of the experiments that promoted enhancements in student motivation and engagement. Results contain promising indicators for the broader educational landscape.

2. Problem Definition

2.1. Problem Statement

Some decisions, made by students working collaboratively on projects during a learning process, have been more costly, less valued, and with less expectation of execution by part of the group, causing demotivation and disengagement (D&D) on the team.

The previous paragraph defined the identified problem that will be described in the next section through the use of personas

3.

2.2. Personas: Under the Problem

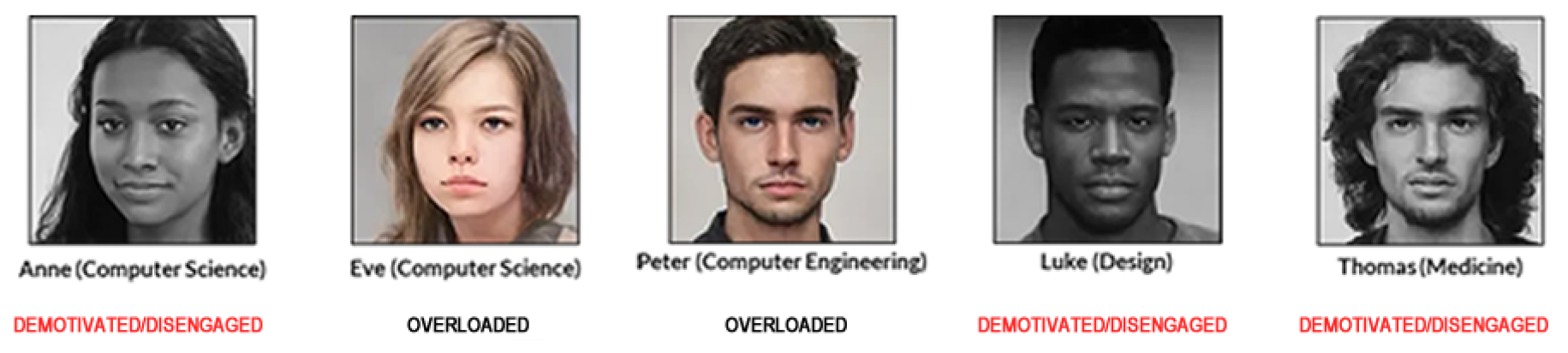

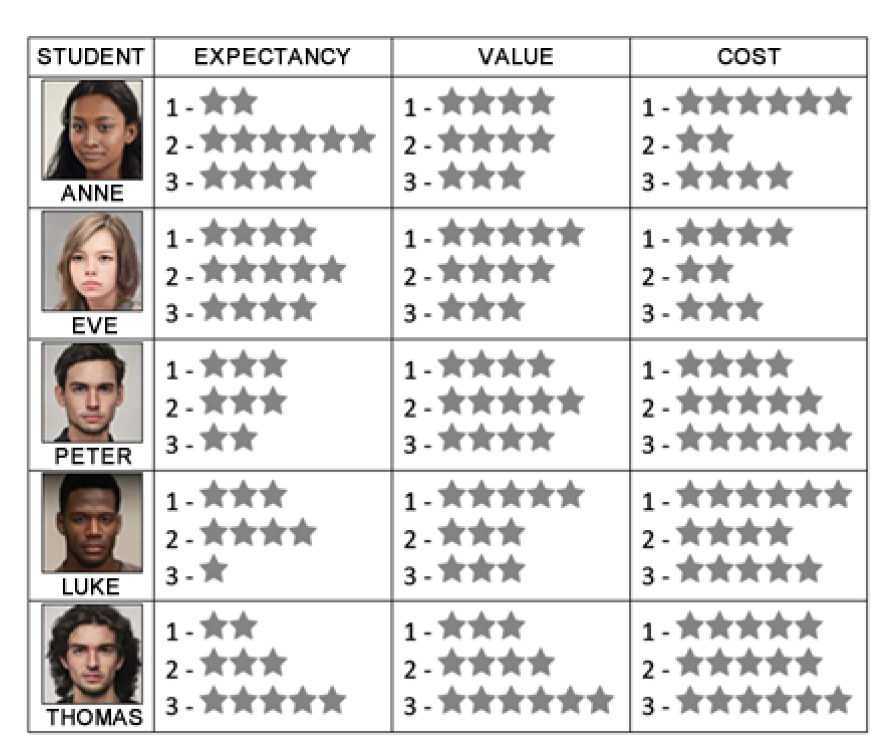

On an innovation learning journey, five students (Anne, Eve, Peter, Luke, and Thomas) assembled a team to work on a project to tackle a real-world problem, creating an innovative technological product to solve it. They are from Computer Science, Computer Engineering, Design, and Medicine courses. At this moment, they are in the convergent phase of choosing the problem to be worked on.

They have already gone through the divergence-convergence cycle multiple times with many previous decisions that eliminated options that some team members were interested in working on. This repetitive process has been generating wear, stress, and conflicts.

At this point, there are already accumulated negative effects, but they still need to choose one of three projects:

1. GPS ITEMS: A project to develop a system using GPS tags and an AR application to help users locate lost, tagged items, addressing the common problem of losing small objects in companies.

2. DEEP TRUE: A project aimed at creating a Deep Fake detection system to monitor social media during Brazilian election periods, combating the use of false images and videos to damage opposing candidates.

3. SUPER EYES: A project to design an eye movement capture system for low-cost VR headsets, facilitating communication for individuals who can only communicate through eye movements.

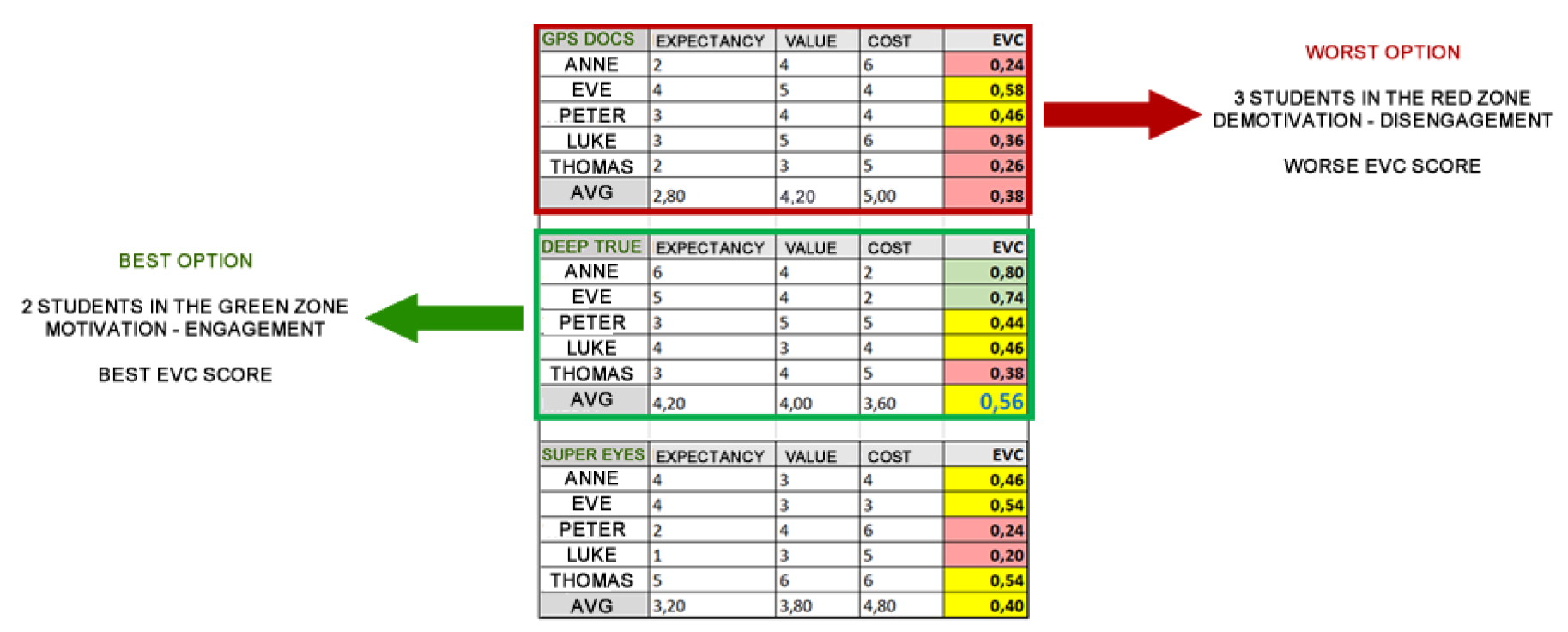

To choose a project, students used the most traditional system of decision: voting. Considering the results shown in

Figure 3, the chosen project was GPS ITEMS, with 3 votes. However, after some time, students experienced demotivation and disengagement. They realized they hadn’t made a good choice.

Anne voted on the spur of the moment, even though she thought she wouldn’t be able to do her best on the project. Her expectations were low and she was afraid of failing. She decided to take a chance, but her fears were confirmed and she became unmotivated.

Thomas did not vote for the winning project, he wanted another option, one that would have an impact on people’s quality of life. He practically worked without any interest, becoming demotivated and disengaged.

Luke voted out of curiosity. He would like to work with VR headsets on Project 3, something he had done before, but he chose Project 1. In the end, he found it too costly to learn the technologies involved and ended up quitting the project.

The traditional voting system is unable to capture these issues: expectations, values, and costs; as it is based solely on the number of votes. However, these are crucial issues that directly impact the motivation and engagement of everyone involved. The team continues with the project, making new decisions and ignoring potential threats.

It ended up that 60% of the team was unmotivated (

Figure 4). And with demotivation came disengagement. Delays became frequent. Eve and Peter became overloaded. The quality of the final project was not good and the team’s grade was low. Luke dropped out of the course. The relationship between team members deteriorated.

Similar situations were observed in other teams. In the long term, many Design students, like Luke, began to consider the course to be very difficult (high cost) and created low expectations that they would be able to complete it; so they gave up enrolling in it.

3. Materials and Methods: How the Problem was Discovered?

The problem was identified during a doctoral program and occurred in three stages:

1. Research, through a Systematic Review of the Literature (SLR), of the main causes of D&D in EI (20 causes were identified).

2. Identification, through mixed methods in a real initiative (Projetão), which of the 20 causes had the most negative effects on motivation and engagement. Main cause: difficulties within the decision-making process.

3. Identification of low expectations, low appreciation, and high cost of decisions as the primary source of D&D in teams during learning.

The SLR search string used was ("education for innovation" OR "innovation education") AND (challenges OR barriers OR problems OR difficulties OR impediments OR restrictions OR concerns OR pains OR troubles) AND (demotivation OR disengagement OR amotivation). The databases ACM, IEEE, Springer, Google Scholar, and Academia.edu were utilized. The objective was to find reports of D&D and/or causes, difficulties, and problems leading to D&D and their effects in the context of EI. Articles, preferably peer-reviewed, from 2012 to 2021 were considered.

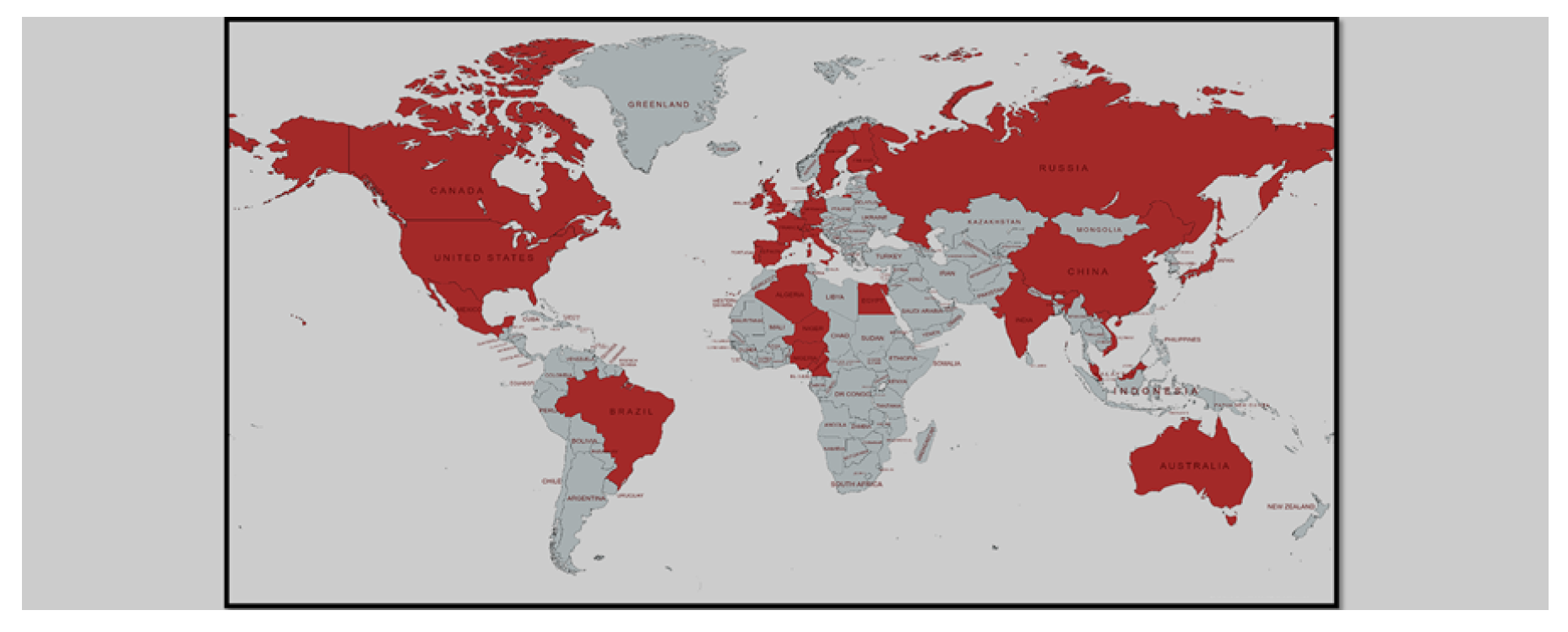

Reports of D&D in education for innovation are scattered in the literature. The SLR considered 95 articles to find 20 main causes of D&D in these types of education initiatives. As a consequence, the literature also does not indicate which of these causes is the most impactful in promoting D&D in EI. This work was pioneering, both in surveying these causes, condensing them in a study, and also by evaluating in a real course, which is similar to several other initiatives from institutions around the planet, which of the difficulties would be worse for the motivation and the engagement of the students. The decision-making process accumulated 41.1% of the student’s votes pointing it as the main cause of D&D. The initiatives researched come from various parts of the globe (see

Figure 5) and together involve the participation of approximately 7,300 students. Most of them are concentrated in the USA or China.

In total, 209 students participated in data collection over 3 consecutive semesters (2019-2020) and a further 30 participated in testing the solution between 2021-2024. A Survey was applied, it included 8 sections encompassing 81 questions, with an average response time of 20 minutes, divided as follows:

Section 1 - 01 question - Consent Term;

Section 2 - 03 questions - General Information;

Section 3 - 04 questions - Course Difficulties;

Section 4 - 12 questions - EVC - Motivation/Engagement;

Section 5 - 25 questions - SCEQ - Types and Levels of Engagement;

Section 6 - 28 questions - AMS - Types and Levels of Motivation;

Section 7 - 05 questions - Detailing Difficulties; and Section 8 - 03 questions - Final Part - Extra Questions.

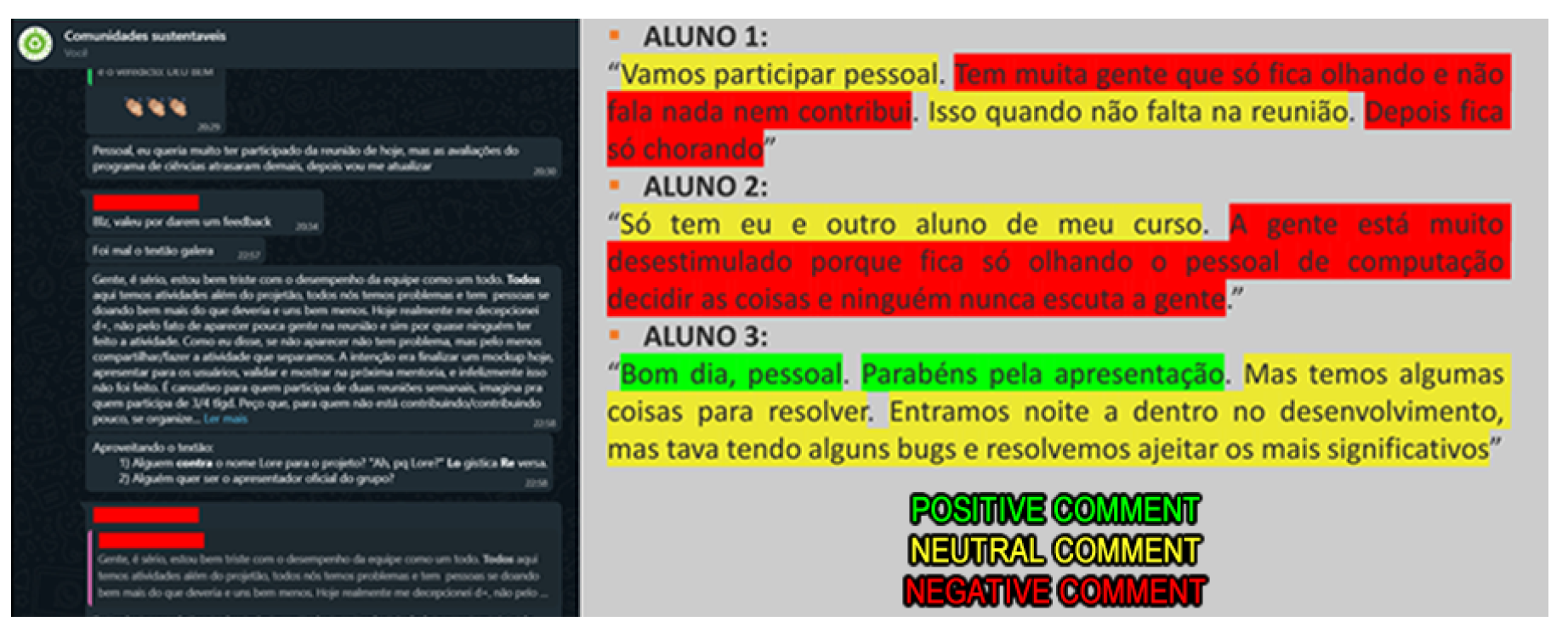

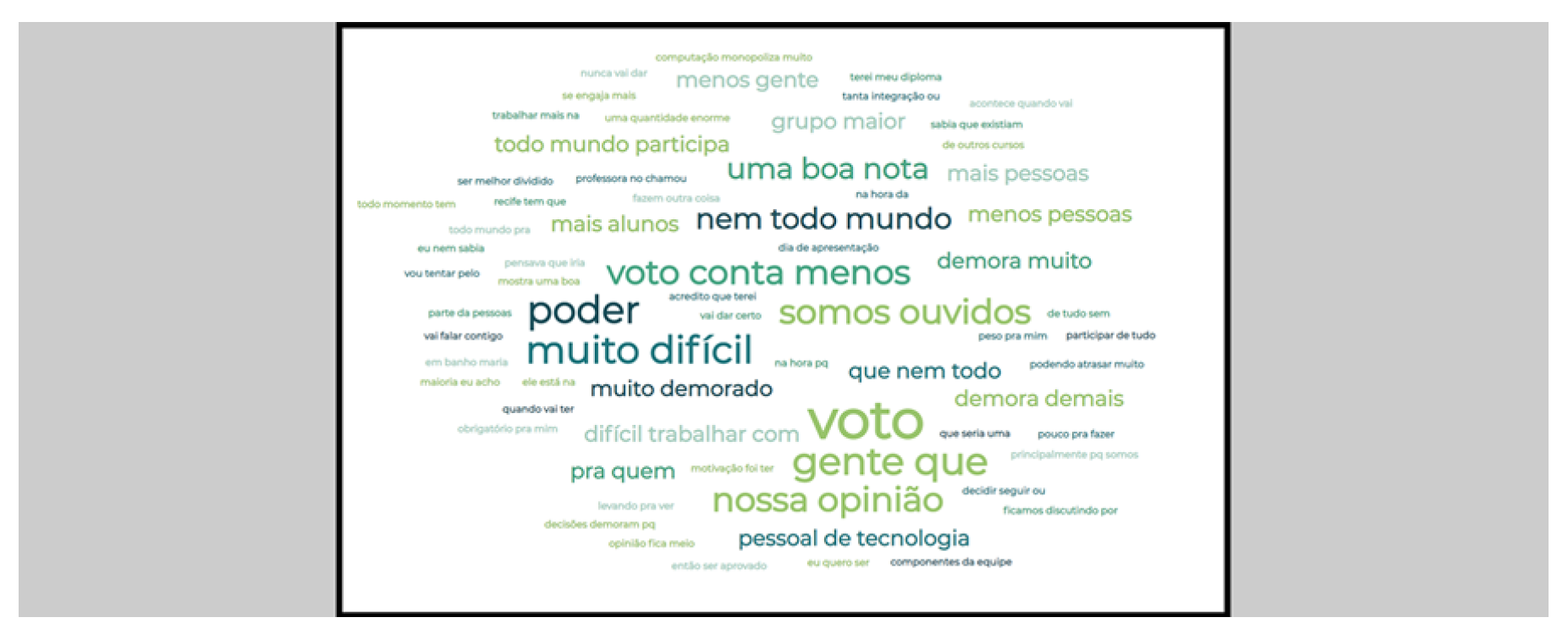

Additionally, 31,847 lines of text generated through conversations between teams working on the projects were evaluated. The analysis was consented to by the students. An artificial intelligence tool for natural language processing (NLP) was used to split positive and negative comments (

Figure 6). The student’s difficulties were analyzed based on the negative ones through word clouds combined with artificial intelligence to consider not only word frequency but also their relevance, relationship with other words in the text, and synonyms, sentence lengths, etc (

Figure 7).

Three tools were used to measure students’ motivation and engagement: EVC, AMS, and SCEQ (

Section 1.4). All presented similar and concordant results, with an excellent degree of agreement according to the Pearson correlation coefficient (0.9524 between EVC and SCEQ, 0.9524 between EVC and AMS, and 0.9286 between AMS and SCEQ; all classified as

strong positive correlation).

There were also semi-structured interviews with the students to understand the main types of complaints they had when making decisions: ’I don’t think I can do it’, ’I don’t want to do it’, and ’It’s difficult’.

Considering all the data collected, the problem was defined with a high degree of certainty. Once the problem was specified, brainstorming was carried out with the students to discuss it and validate it. Also, ideas for a potential solution were presented. The MO-DM was conceived from the combination of all gathered information and is described in the following section.

4. Solution

Decision-making plays a pivotal role in regarding issues of demotivation and disengagement (D&D) within teams. However, conventional decision methods, such as voting, often overlook crucial dimensions like expectations, values, and costs. Given the diverse nature of innovation projects, it’s recognized that no universally applicable solution exists to enhance students’ motivation and engagement uniformly across all endeavors. Each project presents unique challenges and outcomes, requiring tailored approaches.

The Motivation-Oriented Decision-Making (MO-DM) model introduces a scalable solution by integrating the EVC index into decision-making processes. Unlike traditional binary voting systems, where students just say yes or no to an option, MO-DM evaluates them based on the impact on individuals’ expectations, values, and costs. This nuanced approach fosters richer discussions and allows for context-specific assessments, promoting informed decision-making.

By prioritizing simplicity and user-friendliness, MO-DM offers a straightforward yet effective solution. Its implementation demonstrates promising results, showing significant improvements in student motivation and engagement. Moreover, the model identifies individuals most affected by decisions, facilitating targeted support throughout their learning journey.

The forthcoming section will introduce a solution to foster a more motivated and engaged learning environment while mitigating the adverse effects of D&D by changing how students make decisions: the MO-DM.

4.1. Personas: Using the Solution

Anne, Eve, Peter, Luke, and Thomas are ready to choose a project using MO-DM. Instead of voting on the project to be worked on, they will evaluate how each one impacts their expectations, values, and costs. Expectation measures how much the student believes in success in making that choice, the value indicates how much the student wants that option and the cost evaluates the obstacles that could arise from the choice.

Each of these dimensions is evaluated on a 6-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates low impact and 6 high impact. The higher the expectations and values, and the lower the costs, the better. It is worth noting that in the tool created (

Section 4.2), this evaluation is carried out using a star-rating system, where 1 to 6 stars are assigned to each option evaluated, improving the user experience.

After using the MO-DM, we would have the result shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. Based on the new results, a ranking indicates that the best option for motivation and engagement is now the DEEP TRUE project, not GPS ITEMS. The model shows that GPS ITEMS is the worst choice, potentially causing demotivation and disengagement (D&D) in three people and having the lowest EVC score (

Figure 9). Conversely, DEEP TRUE has the potential to leave two people highly motivated and engaged, which is considered excellent for projects [

25].

One point that must be taken into consideration is that, with the choice of the DEEP TRUE project, there will still be one student who will be negatively impacted: Thomas. However, this is prior information that becomes known due to the use of MO-DM, enabling both the team and the teacher to talk to Thomas, accompany him, answer his questions, and promote a dialogue to better understand his main difficulties and prevent him from becoming demotivated and disengaged.

Following a debate on the results, the students chose the DEEP TRUE project, as recommended by the model. Anne had high expectations for the new project and was highly motivated and engaged. Although it was not Thomas’s preferred project, the team provided support and encouragement, and the professor answered more of his questions, leading to a shift in his perspective. Thomas remained motivated and engaged. Luke found the project manageable, developed a curiosity for the involved technologies, and became motivated and engaged. The other team members were not overburdened, and the project was successful. As a result, everyone gained more knowledge and spoke positively about the course, which attracted the interest of new students.

4.2. The MO-DM Tool

A tool was developed to easily apply the MO-DM model in decision-making. It was made public through this

address, and this

one, and is described in this section.

The MO-DM tool is now in its second version. The first version was created in 2022 and was fully developed with Unity

4 using the

C# programming language. A demonstration of the first version can be seen

here. A new version was created in 2024, entirely developed with JavaScript (JS), running on Node.js and using an SQLite database. The adoption of these technologies opened the door for all source code to be made available online, under the MIT license, through this

address. A demo video of the new version can be found

here.

In a simplified way, the tool allows the analysis of each decision, through the evaluation of each of the three EVC dimensions: expectation, value, and cost (

Figure 10). Each decision is attributed to its stakeholders, the people who, in some way, will have their motivation and engagement affected by the choices made. This assessment is made through a user-friendly interface where one to six stars are assigned to each of the dimensions. The proposed formula for obtaining the EVC score is [

21]:

EVC = ((0.3 * E + O.3 * V - 0.4 * C) + 1.8)/5

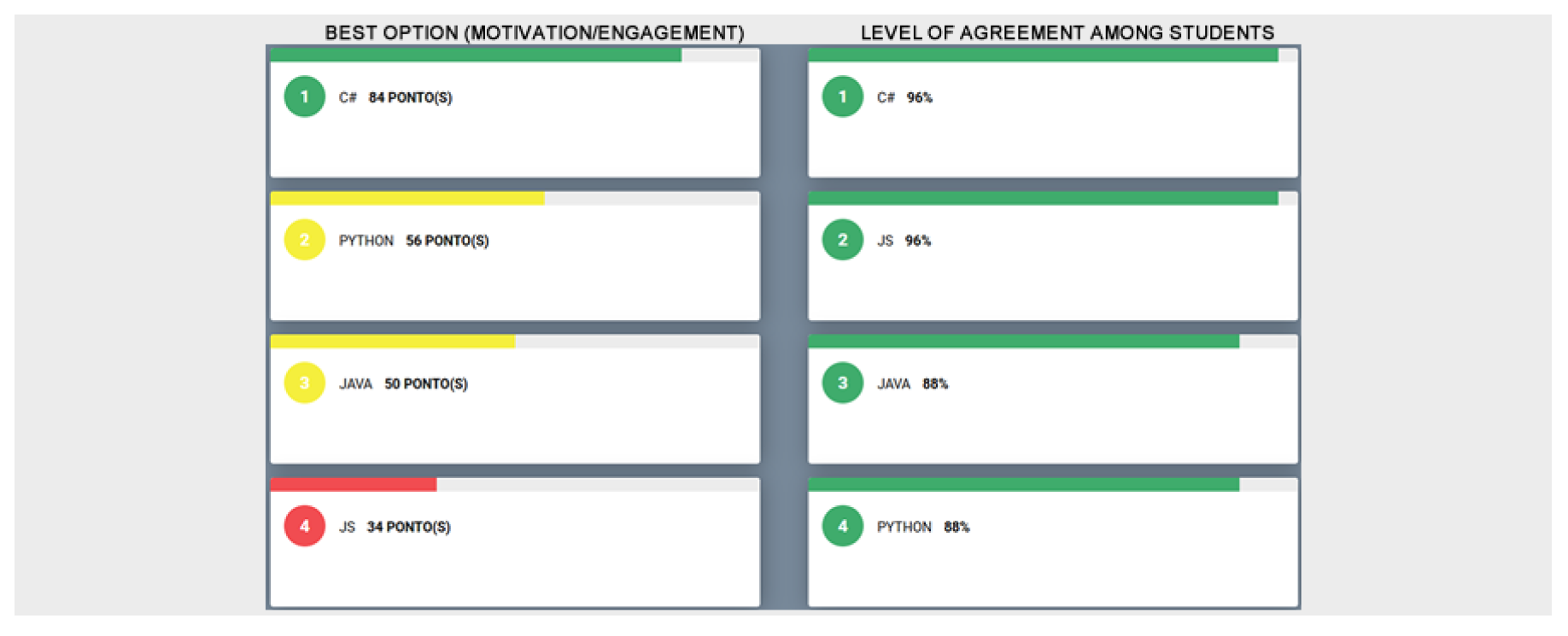

After computing all evaluations, two rankings are established (

Figure 12) that point to the potential best choices to be made by the team. The first, and most important, of the rankings, shows precisely the best options considering motivation and engagement through EVC score. The second rank shows how much stakeholders agree with each other, which is calculated using the IRA

5 statistic r*wg(j) proposed by Lindell et al. [

24].

Considering the EVC score, values below 0.40 points indicate demotivation and disengagement, while values above 0.70 indicate over-motivation and over-engagement (

Figure 11). Regarding levels of agreement between students, a level above 65% is considered good [

21].

4.3. Evaluation

The MO-DM was tested in three different situations that are described in the following sections:

4.3.1. Preliminary Assessment

This evaluation was carried out with five students, in a multidisciplinary team, using the first version of the tool. It was an innovation project simulated during an entire afternoon. The students belonged to the Computer Science (1), Computer Engineering (1), Physics (1), Design (1) and Hospitality (1) courses. They worked together to create a hypothetical, innovative software product to solve a problem. There were four males and one female person with ages ranging from 19 to 25 years old.

Although no code was implemented, and no product was delivered, an interactive prototype was presented at the end. A mentor was fully available to answer questions about using the model and tool.

All decisions were made throughout the 4 stages of the project: preparation, development, testing, and launch. There was no concern about the viability of the product as it was hypothetical software. The selected project was to develop a Lost Document Search System using AR and location tags based on GPS.

At the end of the project, students assessed MO-DM through a survey form. They had to make a classification evaluating whether there was a positive, negative, or no impact, considering seven topics of interest for the model. These points addressed topics such as time for decision-making, influence in the voting system, the feeling of being listened to, participation of everyone involved, efficiency and effectiveness of the decision, and clarity of the impacts of them on those involved.

Furthermore, students were free to add any comments to the evaluation. Fleiss’ Kappa was used to evaluate agreement between students and their motivation and engagement were measured, using the EVC, one day before and one day after using the tool

4.3.2. Assessment in a Higher Technology Course

This is an analysis outside the innovation education environment but within the context of student teams working on a project.

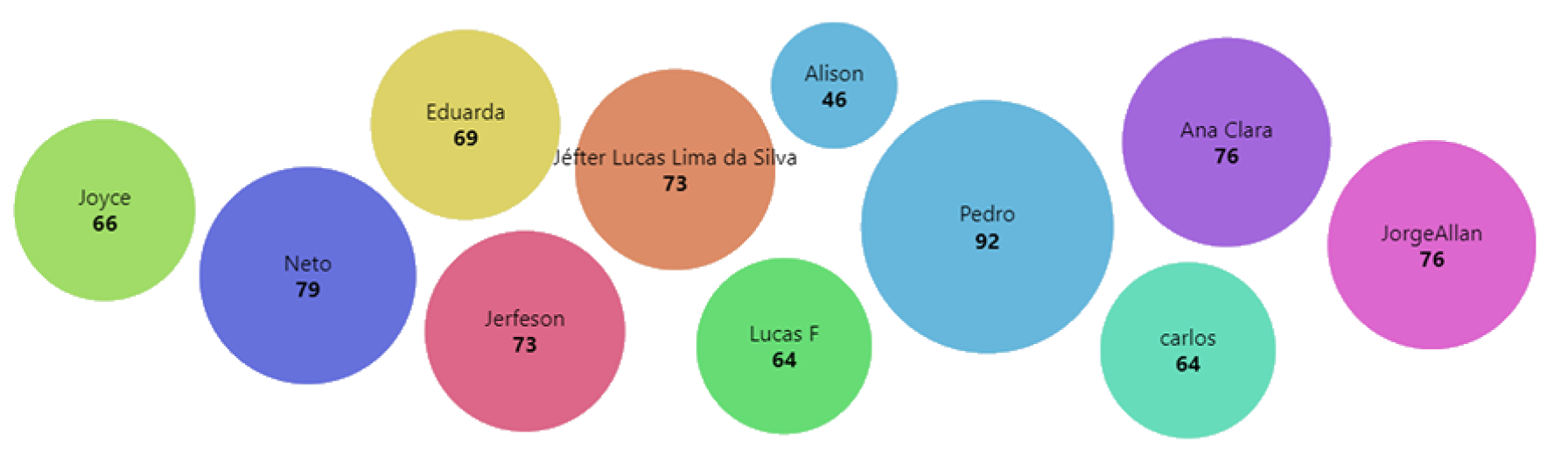

Eleven students from a higher education course in Systems Analysis and Development, at a federal education institute in the state of Paraíba, Brazil, participated in a 1-day Hackathon to create a web application. Eight of them identified themselves as male, and three as female. Ages ranged from 18 to 26 years old. Students were from the first, second, and third semesters of the course (

Figure 13).

The project was not previously defined, so they had to decide among themselves using the MO-DM. There was only one restriction, the project had to address something deliverable on that day, including a working system, with complete documentation and manual, in addition to the final stage of customer training (a role assumed by the Hackathon mentor). It was a full-day event.

They divided the project into five phases: planning, prototyping, development, testing, and delivery. It was called ADS-FAST-PROJECT. All project decisions were made using MO-DM. No other decision-making systems were used.

The students chose to create a digital voting system. They simulated the Brazilian electronic voting machine, but in a web version, with an interface and use of sounds identical to the physical device.

After completing the project, students evaluated the MO-DM by answering two simple questions for which there were only three answers each:

Question 1 - Do you believe that the use of MO-DM, replacing the traditional decision-making system, based on majority votes, brought more motivation and engagement to the team, in addition to promoting better debates and discussions about choices? The possible and mutually exclusive answers to this question were: Yes, No and I need more time to evaluate.

Question 2 - Do you agree with the results of your motivation and engagement levels displayed in the tool and do you believe that they faithfully correspond to how you feel and/or felt about the project and throughout it? For this question, the possible answers were: Yes, No and I’m not sure.

Unlike the situation described in the previous section (

Section 4.3.1), motivation and engagement were not measured before and after using the tool, but throughout its use, decision by decision. The EVC score was used.

4.3.3. Assessment with a Multidisciplinary EI Discipline

This evaluation is still ongoing. It is expected to be completed at the end of the first semester of 2024. This is a team that is participating in Projetão classes (

Section 1.5). The team is made up of fourteen students, six females, and eight males, with ages ranging from 18 to 23 years old. It is a multidisciplinary team with representatives from Computer Science (4), Computer Engineering (1), Administration (2), Economics (4), Design (2) and Nursing (1). The initial name of the team was defined as EDU-MERCADO.

The team is only using the tool for those decisions they consider will have an impact on the team’s motivation and engagement.

Until the time of writing this article, they used the MO-DM to establish the theme of the problem addressed, which involves the difficulty that companies, in general, have in finding qualified professionals for their staff. Furthermore, they are also using the tool to define roles within the team and to choose some activities to be carried out during the week, since the class has weekly deliveries.

As they are practically halfway through the course, it was considered that they could already evaluate the MO-DM based on what they had used so far. The same questions listed at the end of the previous section (

Section 4.3.2) were used, which ask about the potential of the model to bring more motivation and engagement to the team and about the results brought by the tool.

As in the previous scenario (

Section 4.3.2), motivation and engagement were measured throughout the project, using EVC.

4.3.4. Results

Considering the preliminary evaluation (

Section 4.3.1), 82.86% of MO-DM evaluations were positive, against 8% negative. The rest of the evaluations (9.14%) classified the results as neutral (neither positive nor negative). There was moderate agreement among students, reaching a Fleiss Kappa of 0.58. In percentage terms, there was 72% agreement between them. As the main result, an increase of 12.51% in student motivation and engagement was noticed.

In the Systems Analysis and Development class (

Section 4.3.2), there were no students classified as unmotivated/disengaged, that is, with an EVC score below 0.40 (

Figure 14). The team started the project with an EVC score of 0.78, indicating super motivation/engagement, reached a peak of 0.82, and ended it with a level of 0.71 (team average), also super motivated/engaged. The student with the lowest score obtained 0.46 points, pointing to a medium motivation/engagement. On the other hand, the most motivated/engaged student reached the mark of 0.92 points.

All students (100%) stated that MO-DM brought more motivation and engagement to the project, in addition to promoting better debates with the information provided. Regarding the second question, nine students (81.82%) stated that they agreed with the results displayed by the tool about their levels of motivation and engagement. One student (0.09%) stated that he did not agree with his level of motivation and engagement calculated by the tool and another student (0.09%) was unsure whether the levels were consistent with his motivation and engagement.

Finally, in the last scenario (

Section 4.3.3), the project started with a general score of 0.71. It reached a peak of 0.76 and ended with an EVC score of 0.75 (team average), classifying the team as super motivated/engaged. The most motivated/engaged student reached 0.90 points, compared to 0.54 points from the least motivated/engaged one. The most motivated/engaged course was Computer Engineering, with 0.83 points in contrast to 0.59 points from the least motivated/engaged one: Design. These comparisons are displayed in

Figure 15.

In the same way, as seen in the Systems Analysis and Development class scenario, none of the team members reached the levels of demotivation and disengagement. All students (100%) stated that MO-DM was able to bring more motivation and engagement to the project. Furthermore, they all (100%) also stated that they agreed with the results presented by the tool so far. Three students chose to add feedback, in free text form, about the tool:

"I think using the model is very useful, as it makes it possible to see team members who are not as engaged in the project, and then try to better understand what could be causing this disengagement."

"The initiative was very impressive, it brought us a new method of choice that allows us to make better considerations before making a decision."

"I think the tool helps to understand the feelings of the people who are participating in the process. This way, we can better identify who may be dissatisfied with the choices and try to work around them."

5. Comparison with Other Tools

The use of Expectancy-Value models in decision-making is common, facilitating choices [

26]. Traditional models often relate to Subjective Expected Utility (SEU), where evaluations are based on values and probabilities [

27]. Typically, these models are predictive tools [

28,

29] or explain decisions and behaviors [

27]. However, there is no evidence of EVC being used to enhance motivation and engagement in multidisciplinary student teams in EI. The MO-DM model is pioneering in this respect.

Many studies use EVC to predict achievements, failures, dropouts, intentions, grades, and more [

27,

28,

30,

31], all concluding that cost is a strong predictor of negative outcomes. The MO-DM logically extends this to prevent negative results by forecasting poor choices, and facilitating smarter decisions with better information.

Highlighted decision support tools:

-

▪

MO-DM: Prevents D&D by emphasizing motivational and engagement-enhancing choices [

21].

-

▪

MGPM: Predicts decisions but doesn’t focus on reducing D&D [

32].

-

▪

Strateegia: Promotes creativity and debate but doesn’t focus on D&D reduction [

33].

-

▪

Eligere (FAHP): Based on multiple criteria. Does not focus on reducing D&D [

34].

-

▪

CMMDS: Aims for satisfaction by making safer, well-informed choices [

26].

-

▪

EVC framework (EVCF): Evaluates cognitive control costs for beneficial, low-effort choices [

35].

The MO-DM uses EVC to account for cost, expectation, and value, promoting more motivating and engaging choices. The closest model, CMMDS, indirectly supports motivation through satisfaction by eliminating uncertainty, a hypothesis yet untested.

CMMDS might complicate decision-making with information overload, increasing stress and conflict, particularly in frequent and important EI decisions. MO-DM, based on well-established EVC, ensures results geared towards enhancing motivation and engagement and preventing D&D by individualizing the impact of each choice. This allows targeted interventions for affected students to mitigate D&D effects.

Ultimately, MO-DM uniquely focuses on boosting motivation and engagement, acting as a D&D preventive measure already tested in innovation learning.

Another tool, gamification

6, is a widely used strategy to enhance motivation in educational settings. However, while many efforts focus on introducing motivational factors, there is a lack of research on mitigating and preventing demotivational factors. Although the end goal is motivation, these are distinct approaches. Parjanen & Hyypiä [

38] created a game called Innotin to foster motivation and engagement for stimulating creativity in collaborative activities. This game, similar to Monopoly

7, involves innovation challenges instead of traditional property trading. Despite its engaging nature, gamification aims to stimulate rather than prevent or address demotivational factors. The authors note that gamification alone does not guarantee success in innovation processes and suggest future research should examine how these elements (de)motivate individuals.

Similarly, Tobar-Muñoz et al. [

39] used a digital game, CAFET, to promote an innovation mindset, but not all participants adapted well, affecting motivation and engagement. Emmanuel et al. [

37] proposed using an RPG game for innovation education with mixed results. These examples highlight that introducing motivational elements without understanding demotivational factors may not always be effective. Motivational mechanisms vary among individuals, meaning what motivates some may demotivate others [

40,

41].

Thus, it is crucial to evaluate and research demotivational factors to propose strategies to reduce, mitigate, and prevent their adverse effects [

42], as addressed in this work.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the existence of AI decision support systems, AI-based tools that utilize generative artificial intelligence to promote decisions that increase intrinsic motivation [

36]. Due to their recent development, no studies detailing concrete applications of solutions for comparison with the MO-DM have been found, leaving further investigation of the topic as future work. They appear to be promising tools that deserve attention and could contribute to the MO-DM.

6. Discussion

The application of the MO-DM model yielded promising results in both multidisciplinary educational contexts focused on innovation and in technology projects involving collaborative student work. Initial analysis revealed a significant improvement of over 12% in motivation and engagement, prompting further investigation in larger class settings. Subsequent iterations led to the development of version 2.0 of the tool, now open-source and publicly available.

In real classroom scenarios, the new tool facilitated highly motivated and engaged team dynamics, notably maintaining motivation throughout projects without reaching demotivating levels.

Figure 16 contrasts the typical motivation and engagement curve patterns observed in this doctoral research and in the literature [16] with the curve observed when using MO-DM. Normally, motivation and engagement begin high, dip mid-project, and then rise again, with critical demotivation and disengagement occurring in the middle, causing the effects of the "Unfortunate Path of D&D" (

Figure 2). However, with MO-DM, the curve shows higher peaks in the middle and returns to initial levels without reaching critical D&D limits, indicated by EVC indices below 0.40. Though this promising result appears unusual, it will be further examined when the tool is applied across all teams in an initiative.

By leveraging the MO-DM model, students became more self-aware of their expectations, values, and costs, fostering thoughtful decision-making and broader perspectives. This proactive approach likely mitigated demotivation and disengagement, aspects not typically considered in prior projects. Notably, student feedback unanimously highlighted the improvement in motivation and engagement, with a high percentage also validating the system’s information.

Additionally, collaborative and multidisciplinary technological projects showcased superior motivation and engagement among students in technology courses, indicating comfort and alignment with their field. However, vigilance is warranted for students outside their expertise, highlighting the importance of support mechanisms for such individuals.

7. Conclusion

The doctoral research discussed in this article was groundbreaking in identifying key factors contributing to demotivation and disengagement in innovation education initiatives. It further distinguished itself by examining twenty identified issues to determine their impact on student motivation and engagement in collaborative technological projects.

Findings highlighted decision-making processes, particularly choices perceived as costly, with low expectations of success, and lacking team consensus, as primary contributors to demotivation and disengagement (D&D). The proposed solution introduced innovation by integrating the EVC into the decision-making framework, enabling better-informed choices before implementation.

Moreover, the model not only predicts motivation and engagement but also identifies individuals most affected by decisions, facilitating targeted support from peers and instructors to prevent D&D. Students demonstrated improved decision-making and enhanced consideration for team perspectives, prioritizing the well-being of those most affected.

The impressive outcomes, including a 12% increase in motivation and engagement, over 80% positive student evaluations, unanimous recognition of motivation and engagement improvement, and high agreement rates, validate the efficacy of the MO-DM model. Its readiness for broader implementation, potentially across entire classes, signals the final phase of its development: its use by all students on a course, from start to finish. Minor usability adjustments based on student feedback are anticipated to enhance its effectiveness further.

Author Contributions

Research, Document and Experiments, Alvaro Magnum; Supervision, Cristiano Araujo and Patricia Tedesco; Text Revision, Emmanuel Carvalho. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Authorship is limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The portion of the research involving the collection of student responses is still pending approval from the ethics committee due to time constraints.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. "Self-determination theory." Handbook of theories of social psychology 1.20, 2012.

- Reeve, Johnmarshall. "A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement." Handbook of research on student engagement. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2012.

- Rogers, Everett M., Arvind Singhal, and Margaret M. Quinlan. "Diffusion of innovations." An integrated approach to communication theory and research. Routledge, 2014.

- Xu, Haiying, et al. "Can higher education, economic growth and innovation ability improve each other?." Sustainability 12.6, 2020.

- Edwards, John, et al. "Factors influencing the potential of European Higher Education Institutions to contribute to innovation and regional development." Publications Office, 2020.

- Irbīte, Andra, and Aina Strode. "Design thinking models in design research and education." SOCIETY. INTEGRATION. EDUCATION. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. Vol. 4. 2016.

- Mann, Leon, and Irving J. "Conflict theory of decision making and the expectancy-value approach." Expectations and actions. Routledge, 2021.

- Reeve, Johnmarshall. "Self-determination theory applied to educational settings.". 2002.

- Wellborn, James Guy. Engaged and disaffected action: The conceptualization and measurement of motivation in the academic domain. University of Rochester, 1992.

- Coates, Hamish. "The value of student engagement for higher education quality assurance." Quality in higher education 11.1. 2005.

- Brown, Philip R., et al. "The use of motivation theory in engineering education research: a systematic review of literature." European Journal of Engineering Education 40.2. 2015.

- Chow, Tsun, & Dac-Buu Cao. "A survey study of critical success factors in agile software projects." Journal of systems and software. 2008.

- Silva, Rui, Ricardo Rodrigues, and Carmem Leal. "Student learning motivations in the field of management with (and without) gamification." Journal of Management and Business Education 3.1. 2020.

- Miller, Charles E. "Group decision making under majority and unanimity decision rules." Social Psychology Quarterly. 1985.

- Christiano, Thomas. The rule of the many: Fundamental issues in democratic theory. Routledge, 2018.

- Heinis, Timon B., Ina Goller, and Mirko Meboldt. "Multilevel design education for innovation competencies." Procedia cirp 50. 2016.

- Acar, Oguz A., Murat Tarakci, and Daan Van Knippenberg. "Creativity and innovation under constraints: A cross-disciplinary integrative review." Journal of management 45.1. 2019.

- Ceschi, Andrea, Ksenia Dorofeeva, and Riccardo S. "Studying teamwork and team climate by using a business simulation: how communication and innovation can improve group learning and decision-making performance." European Journal of Training and Development. 2014.

- Wigfield, Allan, and Jacquelynne S. Eccles. "Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation." Contemporary educational psychology. 2000.

- Soleas, Eleftherios K. "Leader strategies for motivating innovation in individuals: a systematic review." Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 9. 2020.

- Neto, Alvaro Magnum Barbosa, Emmanuel Carvalho, and MarcíLio Bandeira. "MO-DM Tool: Improving teams’ engagement with Motivation-Oriented Decision-Making." Proceedings of the XXXVI Brazilian Symposium on Software Engineering. 2022.

- Soleas, Eleftherios K. What Factors and Experiences Motivate Innovators? An Expectancy-Value-Cost Approach to Promoting Student Innovation. Diss. Queen’s University (Canada), 2020.

- Kosovich, Jeff J., et al. "A practical measure of student motivation: Establishing validity evidence for the expectancy-value-cost scale in middle school." The Journal of Early Adolescence 35.5-6. 2015.

- Lindell, Michael K., Christina J. Brandt, and David J. Whitney. "A revised index of interrater agreement for multi-item ratings of a single target." Applied Psychological Measurement 23.2. 1999.

- Bredillet, Christophe, and Ravikiran Dwivedula. "The influence of work motivation on project success: Towards a framework." Proceedings of the 8th Annual European Academy of Management (EURAM) Conference. European Academy of Management (EURAM), 2008.

- Small, Ruth V., and Murali Venkatesh. "A cognitive-motivational model of decision satisfaction." Instructional science 28, 2000.

- Feather, Norman T., ed. Expectations and actions: Expectancy-value models in psychology. Routledge, 2021.

- Jiang, Yi, Emily Q. Rosenzweig, and Hanna Gaspard. "An expectancy-value-cost approach in predicting adolescent students’ academic motivation and achievement." Contemporary Educational Psychology 54, 2018.

- Raczkoski, Brandon Marc. Examining predictors of student motivation to enroll in a study abroad course from a relative costs perspective. Diss. Oklahoma State University, 2018.

- Oliveira, Reutman, and César França. "Agile Practices and Motivation: A quantitative study with Brazilian software developers." Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering. 2019.

- Chen, Pei-Chi, Ching-Chin Chern, and Chung-Yang Chen. "Software project team characteristics and team performance: Team motivation as a moderator." 2012 19th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference. Vol. 1. IEEE, 2012.

- Ballard, Timothy, et al. "An integrative formal model of motivation and decision making: The MGPM*." Journal of Applied Psychology 101.9, 2016.

- Neves, André, et al. "Strateegia: a framework that assumes design as a strategic tool." Advances in Ergonomics in Design: Proceedings of the AHFE 2020 Virtual Conference on Ergonomics in Design, 16–20 July 2020, USA. Springer International Publishing, 2020. 16 July.

- Grazioso, Stanislao, et al. "Eligere: a fuzzy ahp distributed software platform for group decision making in engineering design." 2017 IEEE international conference on fuzzy systems (FUZZ-IEEE). IEEE, 2017.

- Kool, Wouter, Amitai Shenhav, and Matthew M. Botvinick. "Cognitive control as cost-benefit decision making." The Wiley handbook of cognitive control, 2017.

- Buçinca, Zana. "Optimizing Decision-Maker’s Intrinsic Motivation for Effective Human-AI Decision-Making." Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2024.

- Carvalho, Emmanuel, et al. "A proposal for micromanagement of people through RPG cards in education for innovation." 2022 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON). IEEE, 2022.

- Parjanen, Satu, and Mirva Hyypiä. "Innotin game supporting collective creativity in innovation activities." Journal of Business Research 96, 2019.

- Tobar-Muñoz, Hendrys, et al. "Videogames and innovation: Fostering innovators’ skills in online-learning environments." Sustainability 12.21, 2020.

- Koltharkar, Parth, K. K. Eldhose, and R. Sridharan. "Application of fuzzy TOPSIS for the prioritization of students’ requirements in higher education institutions: A case study: A multi-criteria decision making approach." 2020 International Conference on System, Computation, Automation and Networking (ICSCAN). IEEE, 2020.

- Koh, Jinyoung. "The importance of context in predicting the motivational benefits of choice, task value, and decision-making strategies." International Journal of Educational Research 102, 2020.

- Silva, Rui, Ricardo Rodrigues, and Carmem Leal. "Student learning motivations in the field of management with (and without) gamification." Journal of Management and Business Education 3.1, 2020.

| 1 |

Critical success factors (CSFs) are essential elements within a project, area, activity, or role performed. The absence of these elements can result in the failure of a project. |

| 2 |

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is the most common way of measuring a linear correlation. It is a number between –1 and 1 that measures the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables. |

| 3 |

The concept of personas involves the use of fictional characters, placed within a precisely described situation, to represent how users impact or are impacted, in a hypothetical or reality-based narrative context. Their perceptions and objectives, among others, are taken into account |

| 4 |

Unity is, originally and primarily, a game engine. However, there are already other types of applications created with the platform that take advantage of its 3D graphic capabilities |

| 5 |

Inter-rater agreement (IRA) can be defined as the degree to which individuals agree about something. There are plenty of IRA statistics indices for Likert-type response scales to quantify consensus in target ratings. |

| 6 |

Gamification means the application of elements used in games, such as aesthetics, mechanics, and dynamics, to other contexts unrelated to games. For example, awarding badges and points, creating rankings, etc. |

| 7 |

Monopoly is one of the most popular board games in the world, in which properties such as houses, hotels, and businesses are bought, sold, and rented. The objective of the game, played by multiple players, is to become wealthy and bankrupt the opponents. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).