1. Introduction

Human-induced CO₂ emissions have markedly increased owing to the rise in fossil fuel use since the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century [

1]. The oceans serve as a significant sink for anthropogenic CO₂ emissions, absorbing approximately 48% of these emissions since the onset of the Industrial Revolution. [

2]. When atmospheric CO

2 reacts with seawater, carbonic acid (H

2CO

3) is formed. This compound is unstable in the marine environment and dissociates into bicarbonate (HCO

3−) and carbonate (CO

32−) ions, while releasing hydrogen ions (H

+) [

1]. While the ocean's absorption of CO2 alleviates the accumulation of greenhouse gases and rising temperatures in the Earth's atmosphere, it alters the carbonate chemistry of the ocean, resulting in decreased pH and aragonite saturation states, which are essential for marine calcifying organisms and the carbonate cycle within coral reef ecosystems [

3]. This process is often known as ocean acidification (OA).

Ocean acidifications possess a twofold threat to marine life: it not only diminishes the ability of organisms to calcify but also accelerates the dissolution of their calcium carbonate (CaCO

3) structures. The rapid pace of this change produces significant concern, as many marine organisms, especially those that form calcium carbonate structures, may struggle to adapt quickly enough to survive [

4,

5]. The management of CO

2 in marine ecosystems includes efforts to remove excess from the atmosphere. In this context, nature climate solutions have emerged as a preferred option to achieve this goal [

6]. Recent studies have indicated that corals and free-living crustose coralline algae CCA may play a significant role in carbon sequestration by absorbing and storing atmospheric CO₂ [

7]. This process potentially mitigates climate change impacts and helps offset anthropogenic carbon emissions [

8,

9,

10,

11].

In most calcifying phototrophs such as corals and free-living CCA, calcification occurs concurrently with photosynthesis when light is available [

12]. However, the interactions between these two metabolic processes at the organismal level remain poorly understood [

13,

14]. The connection between photosynthesis and calcification may represent a crucial mechanism for carbon recycling. Although this phenomenon has been observed within calcifying communities [

15,

16], a detailed mechanistic comprehension at the organismal scale is still lacking [

17]. From this perspective, numerous studies on corals and coralline algae have demonstrated that calcification rates are highly dependent upon photosynthesis, supporting the concept of photosynthetically enhanced calcification, also known as light-enhanced calcification (LEC) [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Calcification takes place during both day and night, but rates are notably higher during daylight, as photosynthesis can stimulate calcification through LEC [

12,

21]. This is evidenced by the consistently higher calcification rates observed during the day in comparison to night [

22,

23].

The carbon cycle of coral reefs at the ecological level is governed by the interrelated processes of photosynthesis, respiration, calcification, and dissolution, collectively referred to as coral reef metabolism [

18,

24]. Given these interconnected processes, it is crucial to understand the broader carbon cycle, particularly as shifts in seawater pH alter the balance between the different forms of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), represented by the following equilibrium:

This equilibrium is mediated by the processes of calcification-dissolution and photosynthesis-respiration [

18]. Photosynthesis and respiration significantly influence hydrogen ion concentration [H

+], with photosynthesis raising pH by reducing [H

+] and respiration lowering pH by increasing [H

+]. Net photosynthesis (P

net) represents the balance between photosynthesis and respiration, positive and negative flux respectively, and, unlike calcification-dissolution, photosynthesis-respiration does not affect total alkalinity (T

A). Moreover, calcification and dissolution are inversely related, with net calcification (G

net) representing the total of calcification (positive) and dissolution (negative flux). These processes influence the relative concentrations of carbonate (CO

32−), bicarbonate (HCO

3−), and carbon dioxide (CO

2).

Calcification is a biological process significantly influenced by photosynthesis and respiration, which alter pH and consequently affect the carbon chemistry of seawater [

19]. Additionally, the impact of a coral reef's metabolism on seawater chemistry is observed through the rhythmic, daily, and seasonal fluctuations in total alkalinity (T

A) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), often referred to as the 'metabolic pulse.' Since variations in TA and DIC primarily reflect coral reef metabolic activity, they serve as valuable indicators of disturbances affecting coral reefs at the organismal, community, and ecosystem levels [

18]. In summary, these metabolic processes are essential in regulating seawater chemistry. These processes govern the balance of pH, DIC and TA and serve as key indicators of reef perturbations across organismal, community, and ecosystem scales.

The aim of this study was to compare 1) the metabolic processes of photosynthesis-respiration and calcification-dissolution in the free-living rolling coral

Siderastrea radians, a seagrass dweller, and calcifying coralline algae (coated grains), usually made single or a consortium of 2-3 species including variably

Lithothamnion spp.,

Hydrolithon spp. and

Mesophyllum spp., from the back reef [

25] and 2) to clarify and characterize the process of carbonate chemistry recycling within these two different types of tropical calcifiers in the proximity of coral reefs. As both are photosynthesizers, they have the potential to manage high CO

2 concentrations in seawater that may help mitigate ocean acidification within the context of climate change. We hypothesize that free-living (CCA) and rolling corals actively contribute to CO

2 mitigation in seawater through their photosynthetic-respiration and calcification-dissolution processes, with significant variations in their carbon capture capacity depending on the time of day. Moreover, both corals and free-living (CCA) efficiently move carbon cycle in the seawater, playing a crucial role in regulating total alkalinity and dissolved inorganic carbon within their microenvironments through these metabolic activities.

3. Results

For every incubation set, PAR light values were recorded in the morning, afternoon, and night. Differences in photosynthetically active radiation (μmol photons m

-2 s

-1) at different times of the day were assessed using a Kruskal-Wallis test, following confirmation of non-normal data distribution via the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Kruskal-Wallis analysis revealed significant differences between the moments of day (χ² = 175.34, df = 2,

p < 0.05). A post-hoc analysis using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction showed that all pairwise comparisons (afternoon - morning; afternoon - night and morning - night) were statistically significant. Specifically, the comparison between afternoon and morning yielded a Z= -5.16;

p < 0.05, while the comparison between afternoon and night presented a Z= 7.42;

p < 0.05. These results confirm significant variations in photosynthetically active radiation throughout the day, being highest during the morning compared to the afternoon and night (

Figure S2 Supplementary Material).

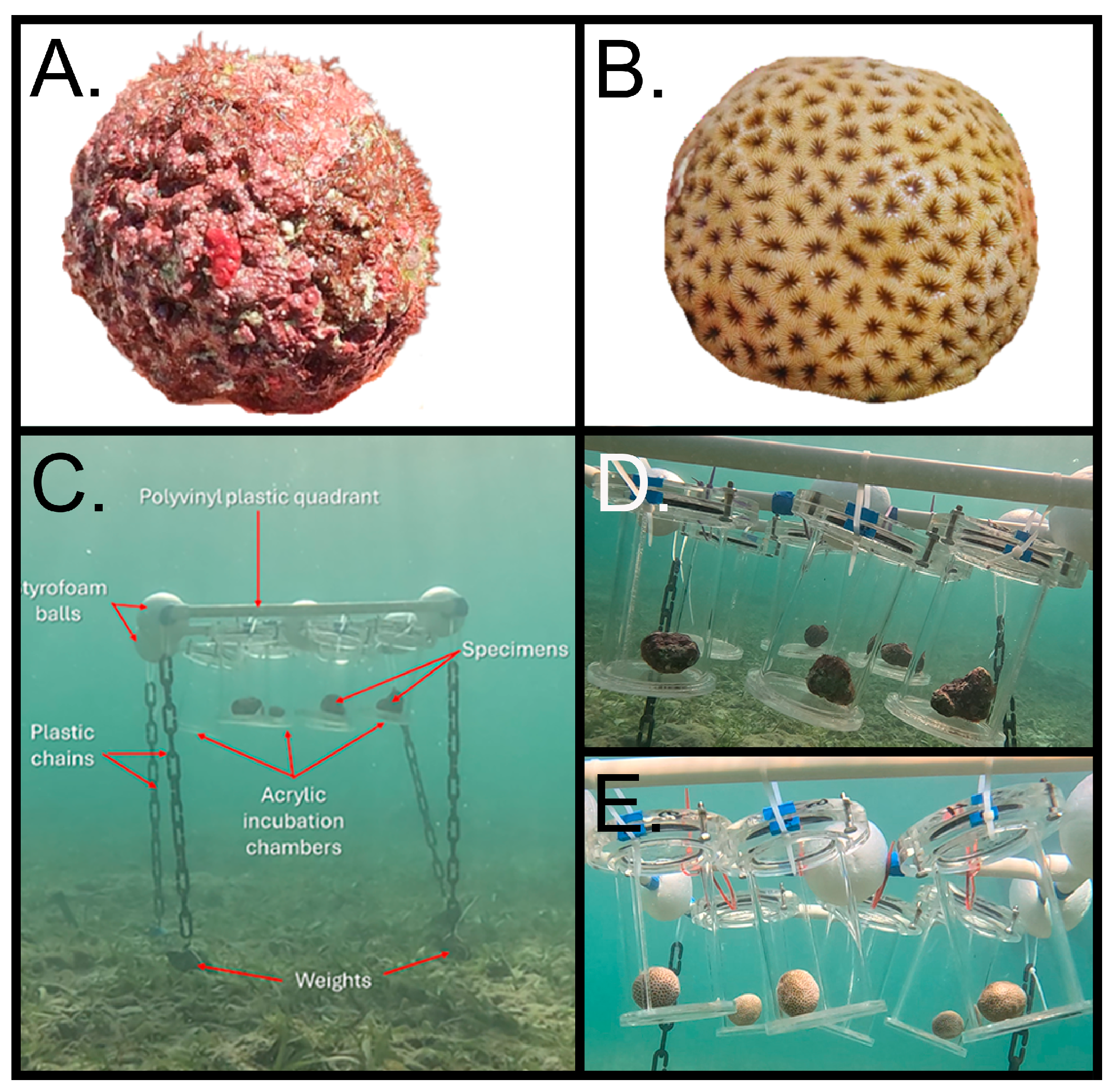

3.1. Daily Changes in Concentration of TA, DIC, HCO3, CO2, CO3 and DO

Both free-living CCA and corals influence seawater chemistry through their metabolic process (photosynthesis-respiration and calcification-dissolution). The lowest change in total alkalinity (∆TA), dissolved inorganic carbon (∆DIC), bicarbonate (∆HCO

3), and carbon dioxide (∆CO

2) were consistently observed during periods of expected net photosynthesis (morning and afternoon) (

Figure 2 A–D respectively), while the highest values were observed at night. Conversely, changes in carbonate (∆CO

3) and dissolved oxygen (∆DO) exhibited the opposite pattern, with greater influence during daylight hours (

Figure 2 E,F) (

Table 1).

Statistical analysis revealed significant effects of both organism type (free-living CCA or coral) and time of day (morning, afternoon, night) on changes in total alkalinity (∆TA) (F=11.076,

p < 0.003 for organism type; F=11.174,

p < 0.01 for time of day), dissolved inorganic carbon (∆DIC) (F=7.271,

p < 0.05; F=61.992,

p < 0.001), bicarbonate (∆HCO

3) (F=5.140,

p < 0.033; F=71.130, p < 0.001) and dissolved oxygen (∆DO) (F=20.321,

p < 0.001; F=176.543,

p < 0.001). While carbonate (∆CO

3) and carbon dioxide (∆CO

2) levels also vary significantly with time of day (F=72.285,

p < 0.001) (F=82.265,

p < 0.001) respectively, they were not significantly affected by type of organism (

p = 0.403;

p = 0.203) respectively. These findings suggest that while both organism type and time of day influence various seawater chemistry variables, their combined effects are not significant across all cases. Notably, a significant interaction effect was observed only for ∆TA indicating that the influence of organism on total alkalinity depends on the type and time of day (

Table 2).

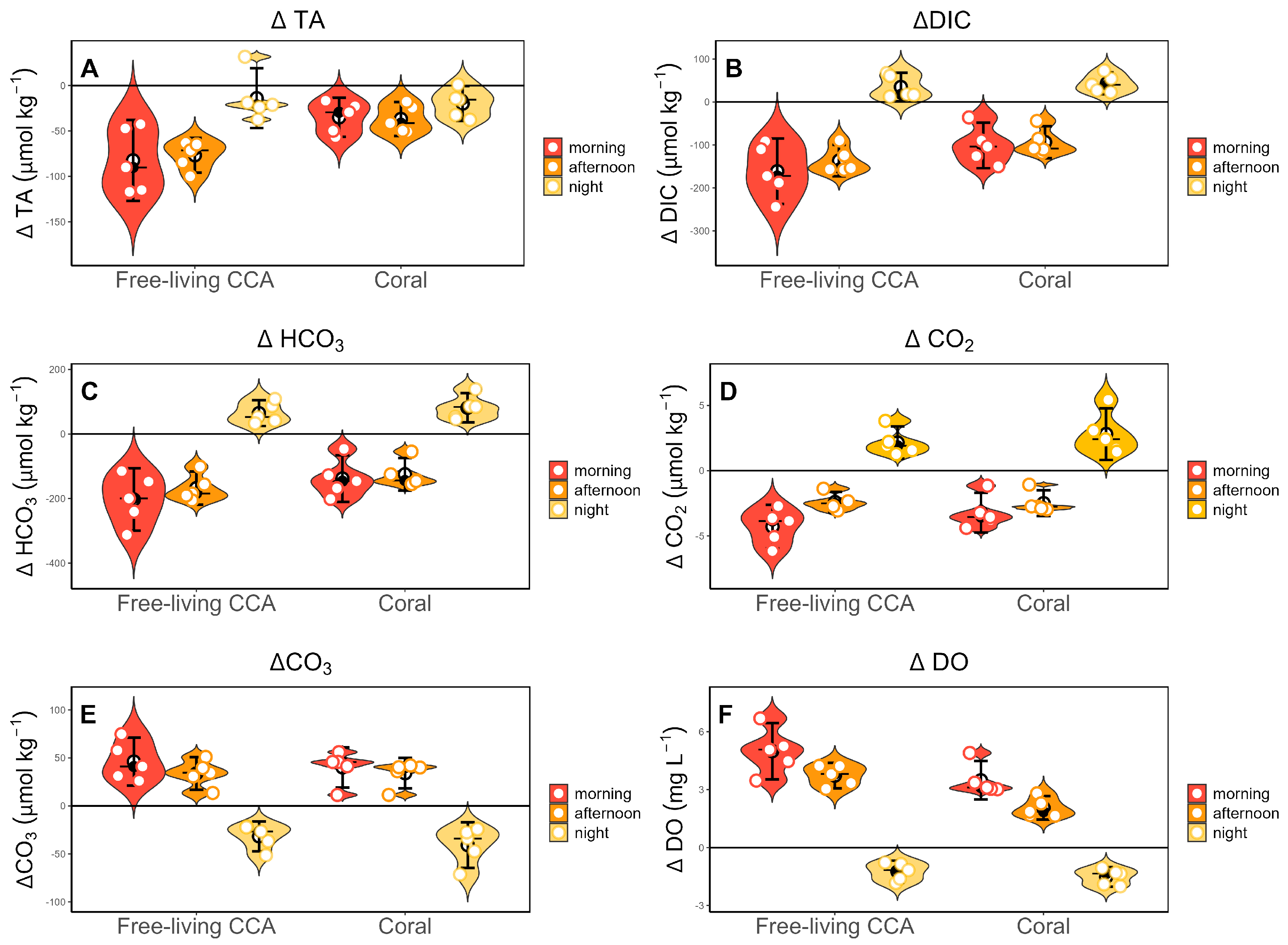

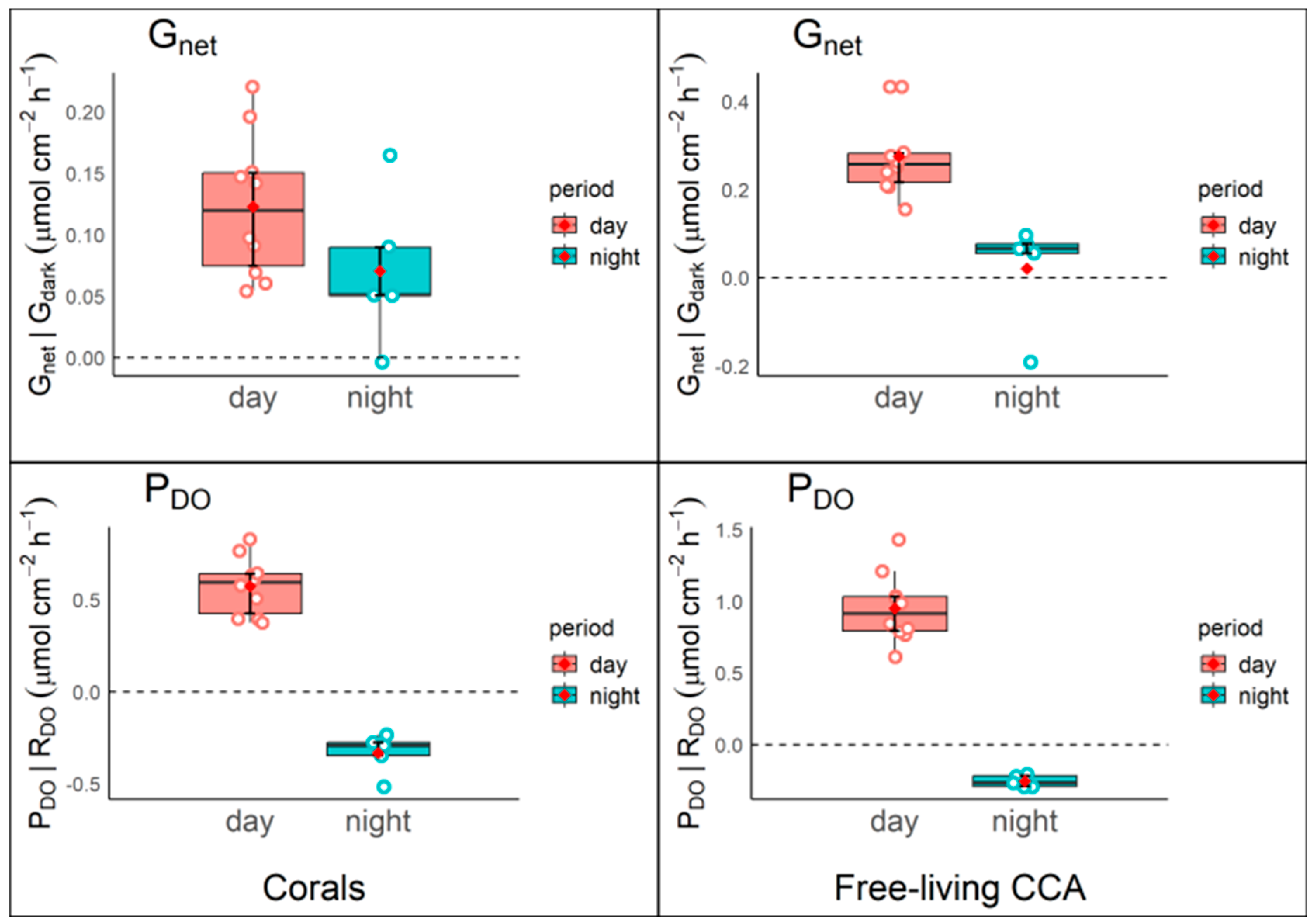

3.2. Rates of Metabolism

3.2.1. Photosynthesis from Oxygen Changes (PDO)

Free-living CCA exhibited significantly higher photosynthetic rates (P

DO) compared to corals during both morning and afternoon incubations, with mean values and standard deviations of 0.975±0.2 and 0.927±0.3, respectively, while corals exhibited rates of 0.686±0.1 and 0.462±0.1. However, at night, corals showed a significantly higher respiration rate than free-living CCA, with a mean and standard deviation of -0.333±0.1, as evidenced by negative P

DO values, reflecting net O

2 consumption (

Table 3,

Figure 3). Statistical analysis revealed a significant effect of organism type on P

DO (F =20.95,

p < 0.001), indicating differences in photosynthetic activity between free-living CCA and corals. Additionally, the time of day significantly influenced P

DO (F=136.654,

p < 0.001), although the interaction between organism type and time of day was not significant (F=3.383,

p = 0.051) (

Table 2).

3.2.2. Calcification (Gnet)

We observed significantly higher calcification rates in free-living CCA (0.243±0.1; 0.307±0.1) than in corals (0.134±0.1; 0.111±0.1) for both morning and afternoon, while corals calcify (0.070±0.1) significantly more at night than free-living CCA (0.020±0.1) (

Figure 3 and

Table 3). Notably, both free-living CCA and corals showed CaCO

3 dissolution at night, with free-living CCA exhibiting higher dissolutions rates (

Figure 3). Statistical analysis showed significant effect in both organism type (F=7.823,

p < 0.01) and time of the day (F=11.948,

p < 0.001) on net calcification (G

net), indicating differences between free-living CCA and corals as well as throughout different times of the day. A significant interaction effect between organism type and time of day (F=5.062,

p =0.015) indicates that the relationship between free-living CCA and coral calcification rates is influenced by the time of day (

Table 2).

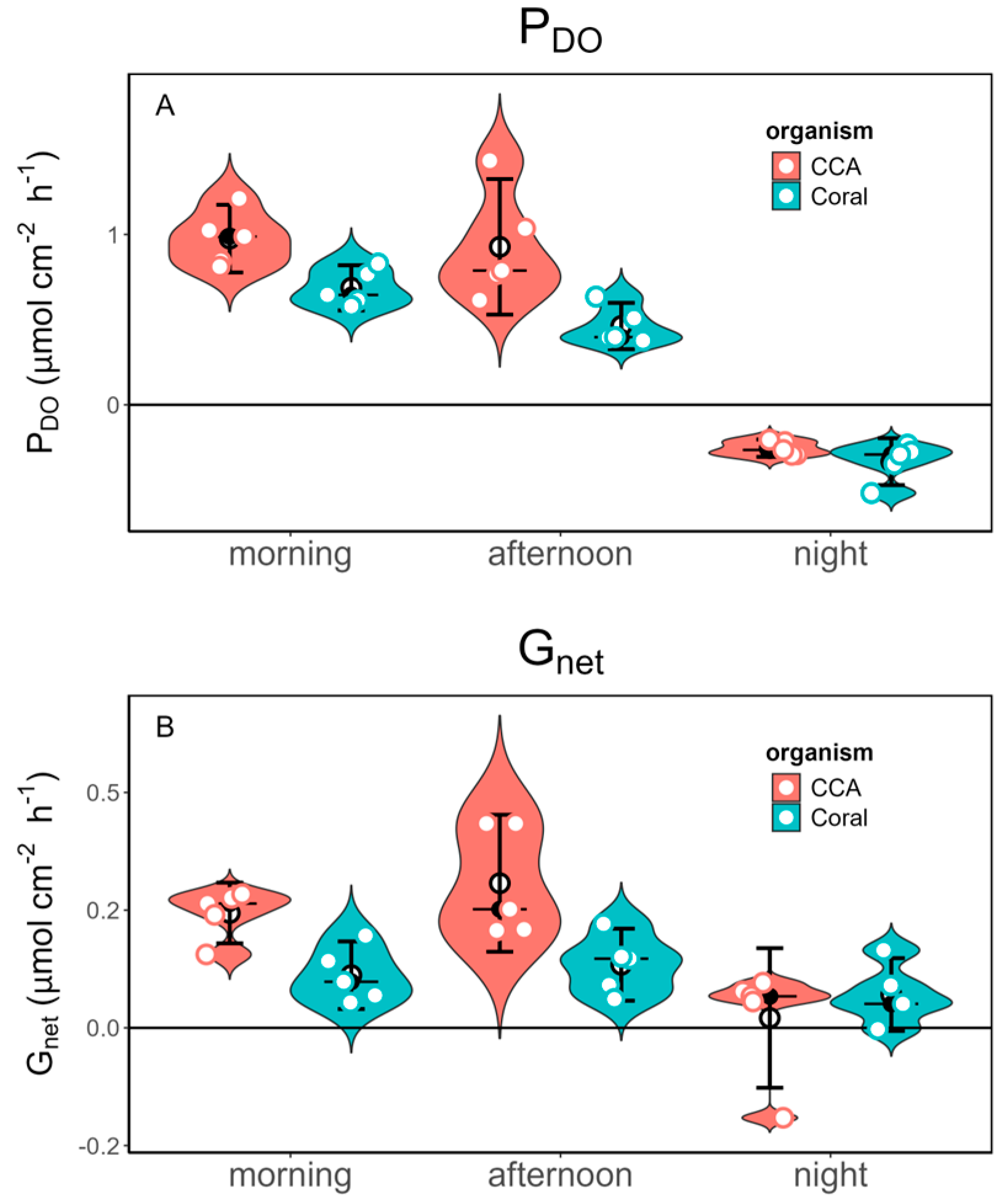

On the other hand, the comparison between net fluxes of calcification rates G

net and productivity P

DO between type of organisms shows that free-living CCA exhibit greater G

net variation between day and night compared to corals, with a clear increase in G

net during the day and a notable reduction at night. This pattern is less pronounced in corals, where G

net values remain more consistent between both periods. Likewise, a similar dynamic is observed in P

DO for both organisms, with a significant increase in productivity during the day and a decline at night. However, free-living CCA shows a greater amplitude in the day/night changes compared to corals. This indicates how free-living CCA shows more pronounced changes in the net fluxes of G

net and P

DO between day and night compared to corals (

Figure 4). Moreover, free-living CCA exhibited 24.7% greater productivity and 79.4% higher calcification than corals when assessed the mean values from day and night (

Table 4). These results highlight important differences in productivity and calcification patterns between the evaluated organisms, suggesting implications for understanding biogeochemical cycles in marine ecosystems.

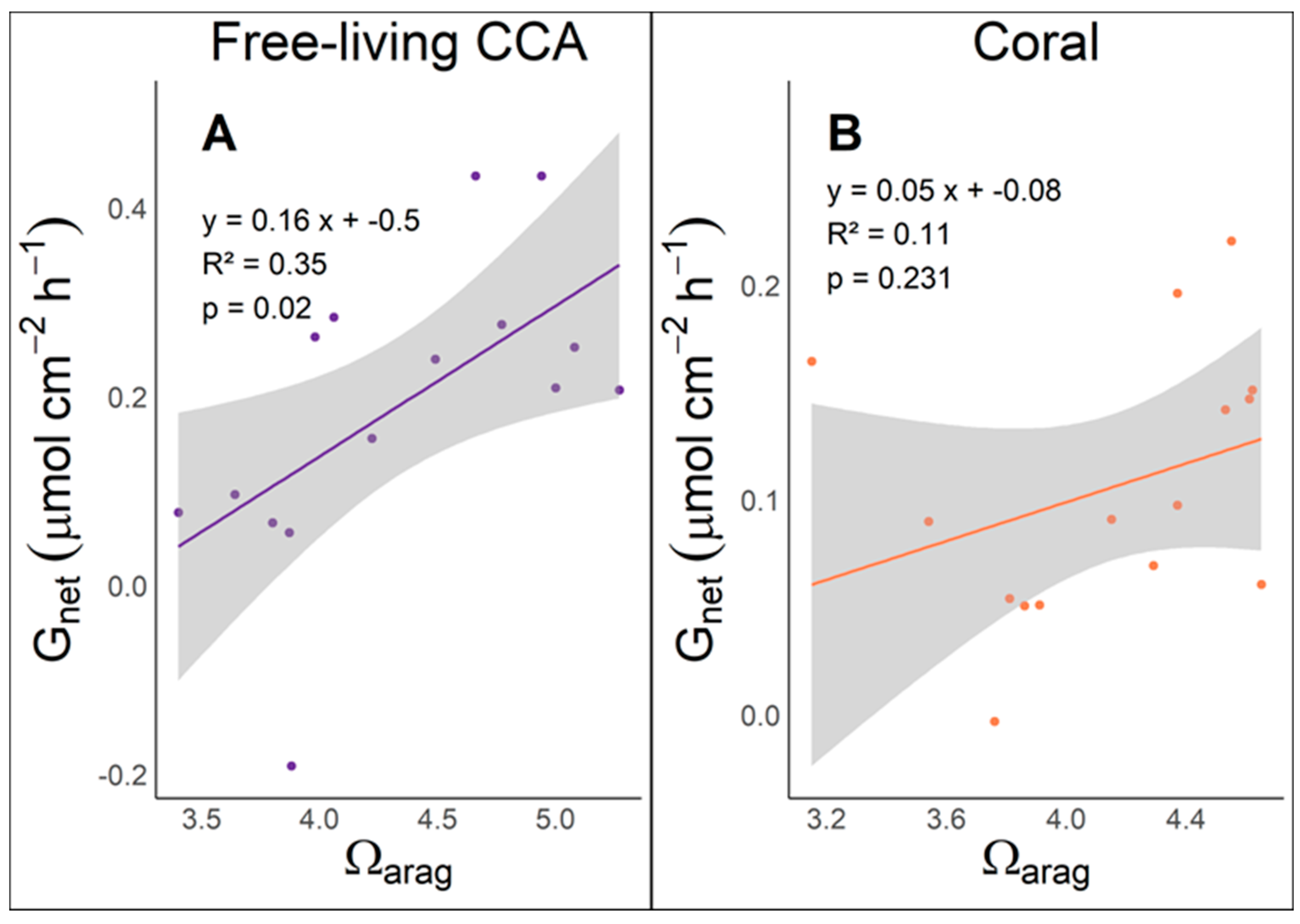

3.3. The Relationship Between Gnet and Ωarag

Plotting the G

net linear regression as a function of Ω

arag has become a widespread way to describe reef calcification [

19]. For instance, a linear regression analysis was employed to evaluate the relationship between net calcification G

net and aragonite saturation state (Ω

arag). In free-living CCA incubations, the analysis revealed a statistically significant positive relationship (

p = 0.0195), suggesting that G

net increases with higher Ω

arag. The regression equation (G

net = 0.16 ⋅ Ω

arag + −0.5) indicates that for each unit increase in Ω

arag, the calcification G

net rises by approximately 0.16 μmol cm

-² h

-1, with the model explaining 35.29% of the variance in G

net (R

2= 0.3529). In contrast, the regression analysis for coral samples demonstrated that the relationship between G

net and Ω

arag was not statistically significant (

p = 0.2306). The regression equation (G

net = 0.05 ⋅ Ω

arag + −0.08) suggests that each unit increase in aragonite saturation only correlates with an increase of 0.04521 μmol cm

-² h

-1 in G

net. This model accounted for 10.85% of the variance in G

net (R

2= 0.1085), indicating weak explanatory power. These findings highlight the distinct influences of aragonite saturation on calcification processes in free-living CCA compared to corals, suggesting that while aragonite saturation significantly impacts net calcification in free-living CCA, other factors may play a more crucial role in coral calcification dynamics (

Figure 5).

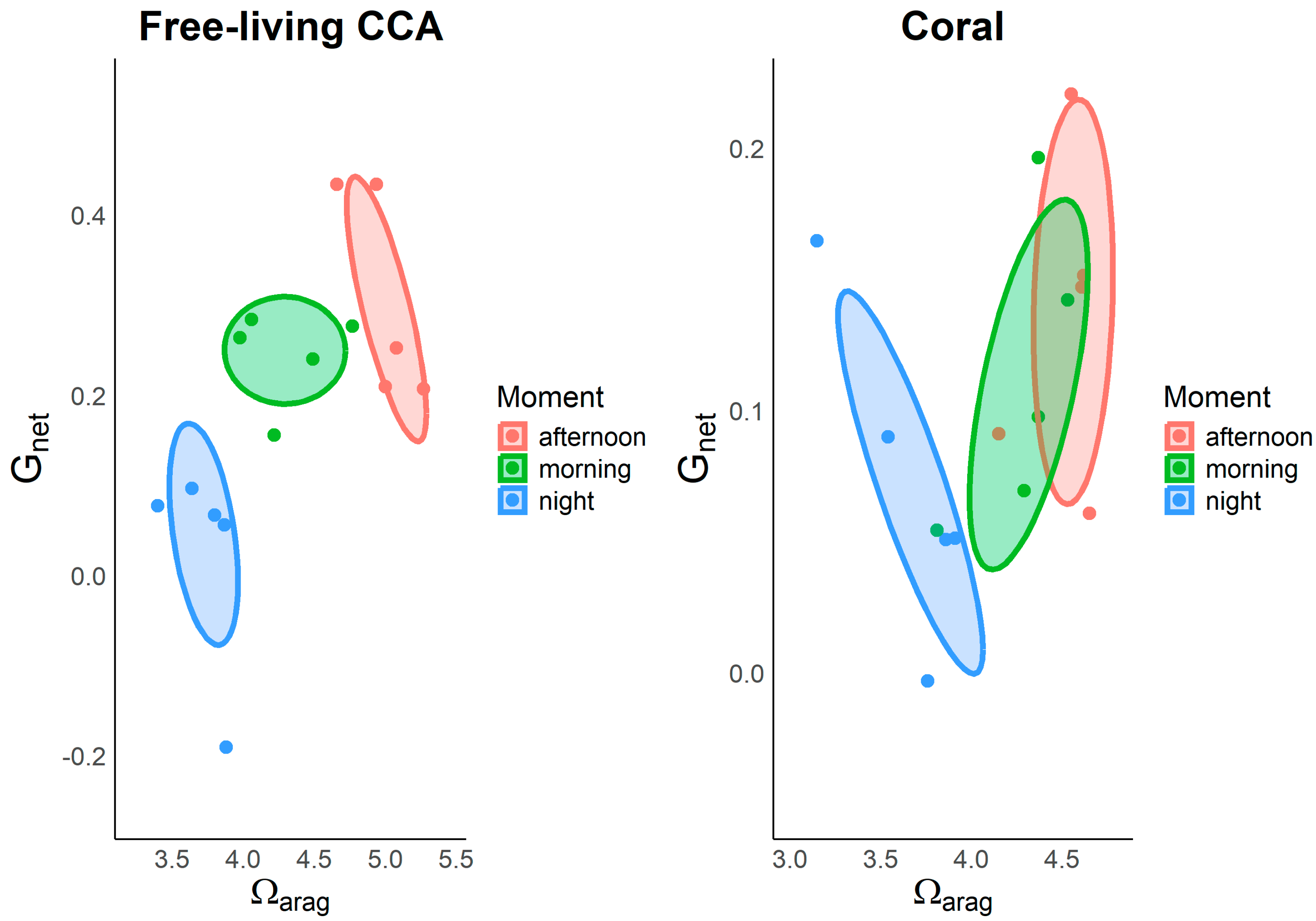

3.4. Diel Hysteresis and Calcification Patterns

Grouping the data of G

net and Ω

arag for type of organism and time of day reveals a distinct pattern of diel hysteresis (

Figure 6). Both organisms show significant variation in the link between Ω

arag and G

net throughout the day. The highest values of Ω

arag and the highest calcification rates occur in the afternoon, indicating increased calcification efficiency under optimal photosynthetic conditions. In contrast, intermediate calcification rates are observed in the morning, while free-living CCA even show negative G

net values at night, suggesting a CaCO

3 dissolution process under these conditions. Additionally, a more pronounced diel hysteresis pattern is evident in free-living CCA compared to corals. In free-living CCA, the relationship between G

net and Ω

arag shows a distinct separation at each time of day. In contrast, corals exhibit overlapping patterns of this relationship during the morning and afternoon (

Figure 6).

The MANOVA results reveal significant effects of both organism and time of day (moment) on net calcification (Gnet) and aragonite saturation state (Ωarag). For the Gnet response, a significant main effect of the factor organism (F = 7.84, p = 0.0099) indicates that calcification rates differ significantly between corals and free-living CCA. Additionally, the effect of moment is highly significant (F = 11.97, p = 0.00025), suggesting a consistent diel variation in calcification, with peak rates observed in the afternoon. The interaction between the organism and the time of day is also noteworthy (F = 5.06, p = 0.0146), indicating different hysteresis patterns in calcification for each organism, each responding uniquely to the varying environmental conditions throughout the day. In terms of Ωarag, the effect of moment of day is highly significant (F = 42.23, p < 0.0001), indicating strong diel fluctuations. The effect of the organism type on Ωarag is not significant (F = 4.07, p = 0.055), indicating that there are no substantial differences in Ωarag between corals and free-living CCA. The interaction between organism and moment is not statistically significant (F = 2.19, p = 0.134), indicating similar diel patterns for both organisms. Overall, these findings underscore the complex, non-linear relationship between calcification, aragonite saturation, and diel environmental changes in marine ecosystems.

4. Discussion

This study provides a comparative analysis of marine carbon flux (carbonate cycle) by two types of photosynthetic and calcifying seafloor rolling organisms, such as free-living CCA and the coral Siderastrea radians. Our results highlight the significant influence of both organisms on different seawater chemistry variables through their metabolic processes.

We observed a consistent diel pattern in total alkalinity (∆TA), dissolved inorganic carbon (∆DIC), bicarbonate (∆HCO

3), and carbon dioxide (∆CO

2), which all reached their lowest values during morning and afternoon hours, with peak values observed at night. This pattern shows the influence of photosynthesis and calcification processes on seawater chemistry, which is more active during daylight hours, as was observed in other studies studying diurnal changes in coral-algae metabolism [

19]. Conversely, carbonate (∆CO

3) and dissolved oxygen (∆DO) exhibited opposite trends, reaching their lowest values at night. This indicates the night-time predominance of respiration that release CO

2 and favor dissolution of calcium carbonate, highlighting the importance of the dynamic interplay between organic and inorganic metabolic processes (photosynthesis-respiration/calcification-dissolution) in influencing the diel cycles of seawater chemistry [

18,

19]. Statistical analyses confirmed the significant influence of both type of organism and time of day on the seawater chemistry variables ∆TA, ∆DIC and ∆HCO

3. While ∆CO

3 and ∆CO

2 also showed substantial diel variation, they did not differ significantly between free-living CCA and corals. Interestingly, a significant interaction effect was observed only in ∆TA, indicating that the influence of organism type on total alkalinity is dependent on the time of day.

Measurements of photosynthesis through oxygen changes (P

DO) revealed significantly higher photosynthetic rates in free-living CCA compared to corals during the morning and afternoon incubations. Conversely, corals exhibited a significantly higher respiration rate at night. The differences found indicate how these organisms contribute to the seawater chemistry at different times of the day. During the morning and afternoon, free-living CCA perform photosynthesis at a much higher rate than corals. Therefore, it generates more oxygen and absorbs more carbon dioxide during these hours compared to corals. Additionally, at night, corals have a significantly higher respiration rate than free-living CCA. Thus, while free-living CCA produces oxygen during the day, corals consume oxygen more rapidly at night. These findings suggest that CCA may play a more substantial role in carbon fixation within the marine ecosystem, which aligns with growing understanding of the potentially contribution of rhodolith beds to the global carbon budget [

8,

37,

38,

39] and in future scenarios of ocean acidification [

40]. This is particularly relevant in the context of current efforts to identified nature-based solutions for mitigating anthropogenic carbon emissions that are leading to climate change [

41].

Significant differences in net calcification (G

net) were observed between free-living CCA and corals as well as throughout the diel cycle. Free-living CCA exhibited higher calcification rates during the morning and afternoon, while corals showed higher dark calcification at night, despite both organisms experiencing CaCO

3 dissolution. These findings highlight the importance of considering both organism type and time of day when evaluating biogeochemical processes in marine ecosystems. Our findings align with recent evidence suggesting that CCA may play a greater role than corals to reef carbonate production in specific areas [

9]. The observed temporal variability underscores the need for studies that integrate both daily variation and differences among organism types to better understand their influence on marine ecosystem dynamics.

The comparison of net fluxes between calcification rates (Gnet) and productivity (PDO) during the day and night in both types of organisms, provides important insights into their distinct roles in marine ecosystems. Free-living CCA demonstrates a more dynamic calcification response to diurnal light changes. This variation could be attributed to differences in metabolic regulation, where it might be more sensitive to light availability, photosynthesis rates, or environmental conditions that affect calcification. In contrast, the more stable Gnet values in corals suggest a more consistent calcification process that may be less influenced by diurnal fluctuations. The pronounced changes in both Gnet and PDO in free-living CCA compared to corals suggest that the former contribute more significantly to carbon cycling during the day, when their calcification and productivity peak. This may indicate that free-living CCA act as carbon sinks during daylight hours, potentially playing a more substantial role in mitigating CO2 levels in marine environments than previously thought. The increased calcification during the day in free-living CCA, followed by a sharp reduction at night, contrasts with the more moderate changes seen in corals, highlighting its greater ecological plasticity in responding to environmental changes.

The 24.7% greater productivity and 79.4% higher calcification in free-living CCA compared to corals, further reinforces the idea that CCA have a stronger influence on carbon biogeochemical cycle. This difference in performance could be linked to their structural composition and ecological interactions, suggesting that free-living CCA may contribute more effectively to the long-term storage of carbon in marine ecosystems. Our results are noteworthy as a recent study revealed conflicting patterns in the assessed calcifying algae (CCA), exhibiting smaller variations compared to the coral species

P. astreoides,

A. cervicornis,

O. faveolata, and

S. siderea in the relationship between both G

net and G

dark, as well as P

DO and R

DO [

20]. Our results indicate that free-living CCA show greater fluctuations in the net fluxes of G

net and P

DO, particularly between day and night, suggesting a higher sensitivity to diurnal environmental changes. Overall, these results highlight the need to further investigate the mechanisms behind the greater amplitude of day/night changes in free-living CCA. Understanding these processes could improve predictive models of carbon cycling and inform conservation efforts aimed at preserving critical marine habitats that play a role in global carbon dynamics.

A diel hysteresis pattern could be demonstrated when grouping the data according to time of day in the linear regression between G

net and Ω

arag in free-living CCA and corals (

Figure 6). Our observations revealed that highest Ω

arag values and calcification rates occur in the afternoon, reflecting an enhanced calcification efficiency under optimal photosynthetic conditions. Intermediate rates are seen in the morning, while free-living CCA display negative G

net values at night, indicating possible dissolution of CaCO

3. Additionally, CCA show a more pronounced diel hysteresis compared to corals, with a clear separation of the G

net-Ω

arag relationship across different times of day. In contrast, corals exhibit overlapping patterns in this relationship between morning and afternoon. This pattern is consistent with the diel hysteresis documented in other studies, where irradiance serves as a primary driver of carbon assimilation during photosynthesis, subsequently regulating calcification rates [

19]. Moreover, previous research has attributed the pronounced diurnal hysteresis observed in coral reefs to the interplay between photosynthesis and respiration processes [

18,

42,

43]. Additionally, the diel hysteresis patterns observed in free-living CCA and corals support the concept of light-enhanced calcification, where photosynthetic processes during the day increase calcification efficiency in these organisms. The higher calcification efficiency in the afternoon and the negative G

net values observed at night in CCA and corals suggest a dependency of calcification on irradiance. This phenomenon may reflect distinct photosynthetic and respiratory processes between CCA and corals, aligning with previous studies that link daytime photosynthesis to increased calcification rates [

19,

20,

22,

23]. The more pronounced diel hysteresis observed in CCA compared to corals highlights their sensitivity to daytime irradiance and underscores their potential role in carbon assimilation in marine ecosystems. Additionally, emphasizes the need to consider temporal dynamics when assessing the role of calcifying organisms in biogeochemical processes, particularly regarding ocean acidification and climate change.

However, the linear regression analysis of

Gnet vs. Ω

arag for free-living CCA and coral explained only a part of the variance (

R2 = 0.352 and R

2= 0.108 respectively). This suggests that the linear regression does not effectively capture the variance associated with the diel pattern. Nevertheless, a similar situation was observed by [

19] when comparing the same variable relationships in a mesocosm experiment. However, unlike our results, they reported a clear hysteresis pattern in corals but not in algae alone. This suggests that additional factors beyond aragonite saturation state, such as light availability, temperature, or nutrient levels, may play a significant role in driving the diel patterns observed. Additionally, the difference in hysteresis patterns suggests that the physiological responses of corals and free-living CCA to environmental variables are distinct, potentially influenced by species-specific traits or environmental conditions that were not fully captured in either study's linear models. This underscores the need for more comprehensive models that incorporate a wider range of variables to better understand the underlying drivers of calcification dynamics.

This study highlights the critical role of free-living CCA and corals in the marine environment, particularly concerning their contributions to the fluxes and reservoirs of oceanic carbon. While both types of organisms exhibit significant rates of calcification and photosynthesis, CCA contribute substantially more to biological carbon sequestration compared to corals. In this regard, in coral reef geology and ecology, crustose coralline algae are increasingly recognized as essential contributors to reef accretion and carbonate production [

7,

9,

44]. These findings are important in the current context of global change, as the ongoing global bleaching events make it increasingly evident that reefs face severe threats [

45,

46]. It therefore seems reasonable that the loss of corals would lead to reduced reef growth and, eventually, the degradation of reef structures. [

44]. Assessing the contribution of coralline calcifying algae (CCA) to net calcium carbonate production and structural stability in coral reefs is becoming essential as climate change progressively diminishes coral cover [

47]. However, detailed assessments of reef growth over ecological timescales have demonstrated that, even with coral loss, accretion can continue, with crustose coralline algae making a particularly notable contribution to this process [

48]. Therefore, the preservation and study of crustose coralline algae and free-living CCA should be a priority in marine conservation efforts, ensuring the stability of reef structures in changing global conditions.

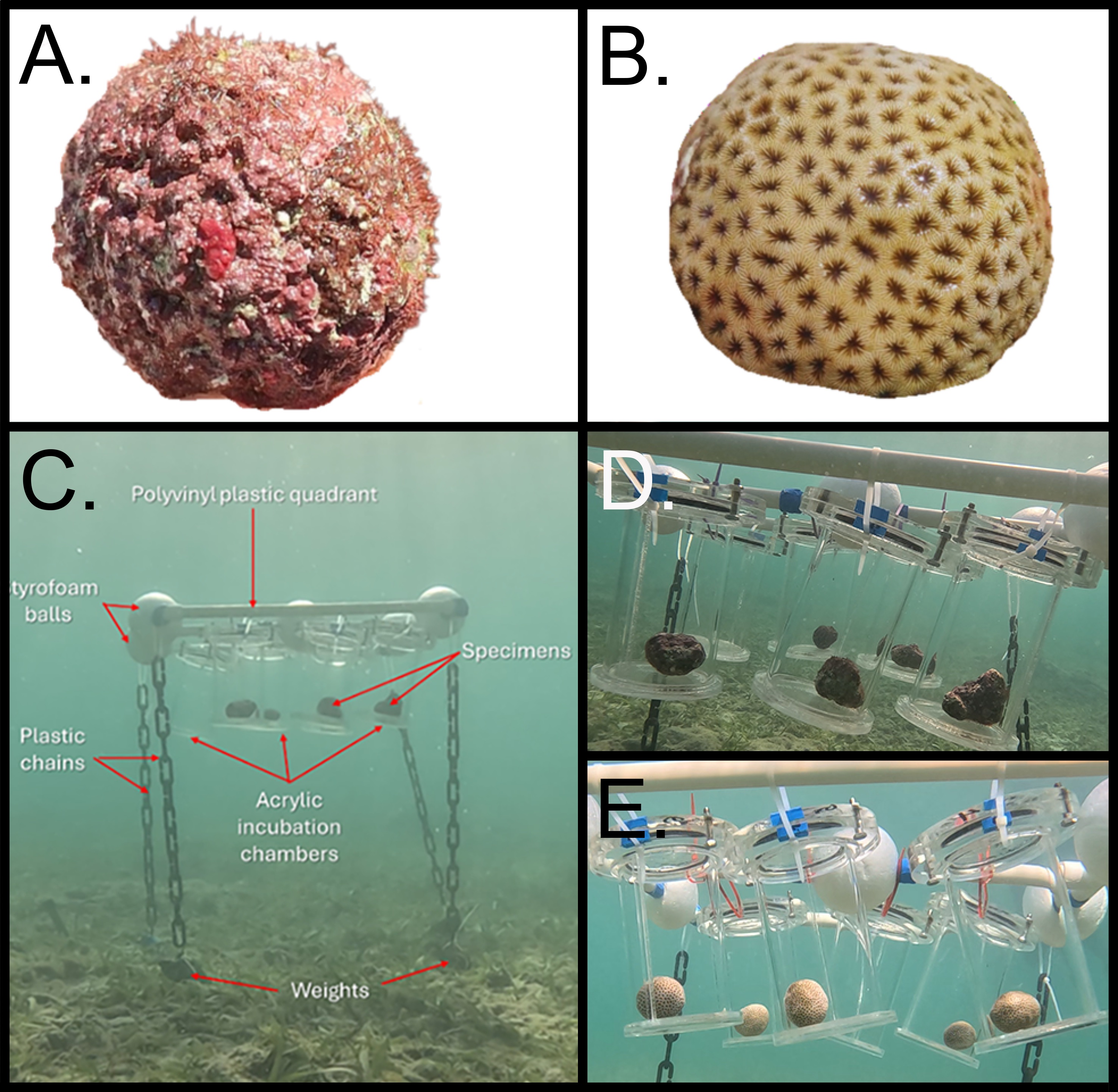

Figure 1.

Type of organisms used in the experiments. A). Free-living non-geniculate calcifying coralline algae (CCA) from the barrier reef. B). Semispherical colonies of Siderastrea radians collected from a seagrass environment. C). In situ incubation setup with acrylic chambers. D). Acrylic chambers with free-living CCA specimens inside. E). Acrylic chambers with S. radians corals inside.

Figure 1.

Type of organisms used in the experiments. A). Free-living non-geniculate calcifying coralline algae (CCA) from the barrier reef. B). Semispherical colonies of Siderastrea radians collected from a seagrass environment. C). In situ incubation setup with acrylic chambers. D). Acrylic chambers with free-living CCA specimens inside. E). Acrylic chambers with S. radians corals inside.

Figure 2.

Plots showing the values of seawater chemistry variables of A) total alkalinity (∆TA), B) dissolved inorganic carbon (∆DIC), C) bicarbonate (∆HCO3), D) carbon dioxide (∆CO2), E) carbonate (∆CO3) and F) dissolved oxygen (∆DO) for incubations at different times of the day (morning, afternoon, and night). Plots show median (horizonal bar with black circle) and IQR (whisker), mean (empty black circle) and Individual data points are represented as empty circles. x-axes show free-living CCA and corals.

Figure 2.

Plots showing the values of seawater chemistry variables of A) total alkalinity (∆TA), B) dissolved inorganic carbon (∆DIC), C) bicarbonate (∆HCO3), D) carbon dioxide (∆CO2), E) carbonate (∆CO3) and F) dissolved oxygen (∆DO) for incubations at different times of the day (morning, afternoon, and night). Plots show median (horizonal bar with black circle) and IQR (whisker), mean (empty black circle) and Individual data points are represented as empty circles. x-axes show free-living CCA and corals.

Figure 3.

Plots for metabolic rates at different times of day (morning, afternoon and night) in Free-living CCA and corals. A) rates of photosynthesis during the day and respiration at night as measured by oxygen changes (PDO: μmol C cm2 h-1) and B) net calcification (Gnet: μmol CaCO3 cm2 h-1) rates during the morning, afternoon and night. .

Figure 3.

Plots for metabolic rates at different times of day (morning, afternoon and night) in Free-living CCA and corals. A) rates of photosynthesis during the day and respiration at night as measured by oxygen changes (PDO: μmol C cm2 h-1) and B) net calcification (Gnet: μmol CaCO3 cm2 h-1) rates during the morning, afternoon and night. .

Figure 4.

Comparison of net fluxes of calcification rates Gnet and productivity through PDO between corals (left panels) and free-living CCA (right panels) during day (red box) and night (green box) periods. Photosynthesis and respiration were calculated from DO: PDO and RDO; light and dark calcification was calculated from changes in total alkalinity during light and dark incubations Gnet and Gdark.

Figure 4.

Comparison of net fluxes of calcification rates Gnet and productivity through PDO between corals (left panels) and free-living CCA (right panels) during day (red box) and night (green box) periods. Photosynthesis and respiration were calculated from DO: PDO and RDO; light and dark calcification was calculated from changes in total alkalinity during light and dark incubations Gnet and Gdark.

Figure 5.

Relationship between net calcification gain (Gnet in µmol of CaCO3 cm−2 h−1) and aragonite saturation (Ωarag) in free-living CCA and corals. The scatter plots display data for both organisms, with the fitted regression line and the 95% confidence interval represented by the shaded gray area. (A) Free-living (CCA) incubations, the linear regression equation is y = 0.16 x + -0.5 with an R² value of 0.35 (p = 0.02). (B) Coral incubations, regression equation y = 0.05 x + -0.08 with an R² value of 0.11 (p = 0.231).

Figure 5.

Relationship between net calcification gain (Gnet in µmol of CaCO3 cm−2 h−1) and aragonite saturation (Ωarag) in free-living CCA and corals. The scatter plots display data for both organisms, with the fitted regression line and the 95% confidence interval represented by the shaded gray area. (A) Free-living (CCA) incubations, the linear regression equation is y = 0.16 x + -0.5 with an R² value of 0.35 (p = 0.02). (B) Coral incubations, regression equation y = 0.05 x + -0.08 with an R² value of 0.11 (p = 0.231).

Figure 6.

Relationship between calcification rates Gnet and aragonite saturation state Ωarag in free-living CCA and corals throughout the diel cycle (morning, afternoon, and night). Free-living CCA (left panel), Corals (right panel).

Figure 6.

Relationship between calcification rates Gnet and aragonite saturation state Ωarag in free-living CCA and corals throughout the diel cycle (morning, afternoon, and night). Free-living CCA (left panel), Corals (right panel).

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters (means and standard deviation SD) of seawater chemistry indicate the difference between the measurements taken at the end of the incubation period and the initial values (final – initial = ∆) of (total alkalinity ∆TA (µmol/kg-1), dissolved inorganic carbon ∆DIC (µmol/kg-1), bicarbonate ∆HCO3 (µmol/kg-1), carbon dioxide ∆CO2 (µmol/kg-1), carbonate ∆CO3 (µmol/kg-1) and dissolved oxygen ∆DO (mg L-1)) for free-living CCA and corals at different times of day, morning, afternoon and night.

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters (means and standard deviation SD) of seawater chemistry indicate the difference between the measurements taken at the end of the incubation period and the initial values (final – initial = ∆) of (total alkalinity ∆TA (µmol/kg-1), dissolved inorganic carbon ∆DIC (µmol/kg-1), bicarbonate ∆HCO3 (µmol/kg-1), carbon dioxide ∆CO2 (µmol/kg-1), carbonate ∆CO3 (µmol/kg-1) and dissolved oxygen ∆DO (mg L-1)) for free-living CCA and corals at different times of day, morning, afternoon and night.

| Organism |

Time of the day |

Temp ◦C |

Sal |

pHT

|

Surface area (cm2) |

∆TA

(µmol/kg-1) |

∆DIC

(µmol/kg-1) |

∆HCO3

(µmol/kg-1) |

∆CO2

(µmol/kg-1) |

∆CO3

(µmol/kg-1) |

∆DO

(mg L-1) |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| Free-living CCA |

morning |

29,9 |

36,0 |

8,1 |

66,7 |

-82,4 |

35,8 |

-161,1 |

61,5 |

-203,0 |

77,9 |

-4,3 |

1,3 |

46,2 |

20,1 |

5,0 |

1,2 |

| afternoon |

30,5 |

36,0 |

8,2 |

66,7 |

-76,7 |

15,4 |

-136,3 |

29,7 |

-167,7 |

41,1 |

-2,4 |

0,6 |

33,9 |

13,7 |

3,7 |

0,5 |

| night |

30,3 |

36,0 |

8,0 |

66,7 |

-14,0 |

26,5 |

35,0 |

26,8 |

64,6 |

32,0 |

2,2 |

1,0 |

-31,7 |

12,6 |

-1,2 |

0,5 |

| Coral |

morning |

29,9 |

36,0 |

8,1 |

62,8 |

-35,1 |

17,4 |

-101,0 |

42,8 |

-137,9 |

58,1 |

-3,2 |

1,2 |

40,1 |

16,9 |

3,5 |

0,8 |

| afternoon |

30,7 |

36,0 |

8,1 |

62,8 |

-36,8 |

15,0 |

-93,3 |

30,1 |

-124,9 |

40,8 |

-2,5 |

0,8 |

34,0 |

12,8 |

2,1 |

0,5 |

| night |

30,3 |

36,0 |

8,0 |

62,8 |

-19,8 |

15,5 |

43,4 |

20,6 |

81,4 |

36,8 |

2,8 |

1,6 |

-40,9 |

19,2 |

-1,5 |

0,4 |

Table 2.

Output of Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) tests regarding delta of several dependent variables as physicochemical parameters (∆TA, ∆DIC, ∆HCO3, ∆CO2, ∆CO3 and ∆DO) of seawater and photosynthesis measured by oxygen changes (PDO), and calcification (Gnet) rates between type of organisms and time of day as independent variables. Df (Degrees of Freedom), Sum Sq (Sum of Squares), Mean Sq (Mean Square), F value, p (p-value), Significance codes (SC): <0.001 ‘***’, 0.001 ‘**’, 0.01 ‘*’.

Table 2.

Output of Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) tests regarding delta of several dependent variables as physicochemical parameters (∆TA, ∆DIC, ∆HCO3, ∆CO2, ∆CO3 and ∆DO) of seawater and photosynthesis measured by oxygen changes (PDO), and calcification (Gnet) rates between type of organisms and time of day as independent variables. Df (Degrees of Freedom), Sum Sq (Sum of Squares), Mean Sq (Mean Square), F value, p (p-value), Significance codes (SC): <0.001 ‘***’, 0.001 ‘**’, 0.01 ‘*’.

| Dependent variables |

Independent variables and interaction |

Df |

Sum Sq |

Mean Sq |

F |

p |

SC |

| ∆TA |

Organism |

1 |

5519.8 |

5519.8 |

11.076 |

0.003 |

** |

| Time of day |

2 |

11136.5 |

5568.3 |

11.174 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Interaction |

2 |

4145.8 |

2072.9 |

4.159 |

0.028 |

* |

| ∆DIC |

Organism |

1 |

10355 |

10355 |

7.271 |

0.013 |

* |

| Time of day |

2 |

176563 |

88281 |

61.992 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Interaction |

2 |

3485 |

1742 |

1.223 |

0.312 |

|

| ∆HCO3 |

Organism |

1 |

13001 |

13001 |

5.140 |

0.033 |

* |

| Time of day |

2 |

359792 |

179896 |

71.130 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Interaction |

2 |

2922 |

1461 |

0.577 |

0.569 |

|

| ∆CO3 |

Organism |

1 |

189 |

189.4 |

0.725 |

0.403 |

|

| Time of day |

2 |

37740 |

18870.2 |

72.285 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Interaction |

2 |

113 |

56.7 |

0.217 |

0.806 |

|

| ∆CO2 |

Organism |

1 |

2.254 |

2.254 |

1.716 |

0.203 |

|

| Time of day |

2 |

216.007 |

108.004 |

82.265 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Interaction |

2 |

1.702 |

0.851 |

0.648 |

0.5318 |

|

| ∆DO |

Organism |

1 |

9698 |

9698 |

20.321 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Time of day |

2 |

168498 |

84249 |

176.543 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Interaction |

2 |

2835 |

1417 |

2.969 |

0.070 |

|

| PDO |

Organism |

1 |

0.5782 |

0.5782 |

20.953 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Time of day |

2 |

7.5425 |

3.7712 |

136.654 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Interaction |

2 |

0.1867 |

0.0934 |

3.383 |

0.051 |

|

| Gnet |

Organism |

1 |

0.054 |

0.054 |

7.823 |

< 0.01 |

** |

| Time of day |

2 |

0.166 |

0.083 |

11.948 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Interaction |

2 |

0.070 |

0.035 |

5.062 |

0.015 |

* |

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations SD of net productivity (PDO) and calcification (Gnet) rates of free-living CCA and corals across different times of the day.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations SD of net productivity (PDO) and calcification (Gnet) rates of free-living CCA and corals across different times of the day.

| Organism |

Time of the day |

Net Productivity |

Net Calcification |

| PDO (μmol C cm2 h-1) |

Gnet (μmol CaCO3 cm2 h-1) |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| Free-living CCA |

morning |

0.975 |

0.2 |

0.243 |

0.1 |

| afternoon |

0.927 |

0.3 |

0.307 |

0.1 |

| night |

-0.254 |

0.0 |

0.020 |

0.1 |

| Coral |

morning |

0.686 |

0.1 |

0.134 |

0,1 |

| afternoon |

0.462 |

0.1 |

0.111 |

0,1 |

| night |

-0,333 |

0.1 |

0.070 |

0,1 |

Table 4.

Day and night variation of net productivity PDO and calcification Gnet in free-living CCA and corals. day means include morning and afternoon data, net (day mean – nigh mean), %: comparative differences between free-living CCA and corals in net productivity and net calcification.

Table 4.

Day and night variation of net productivity PDO and calcification Gnet in free-living CCA and corals. day means include morning and afternoon data, net (day mean – nigh mean), %: comparative differences between free-living CCA and corals in net productivity and net calcification.

| Organism |

Time of day |

Net Productivity |

Net Calcification |

| PDO

|

Gnet

|

| Mean |

net

(day - night) |

Mean |

net

(day - night) |

| Free-living CCA |

day |

0.951 |

1.206 |

0.275 |

0.254 |

| night |

-0,333 |

0.020 |

| Coral |

day |

0.574 |

0.907 |

0.123 |

0.052 |

| night |

-0,333 |

0.070 |

| % difference |

|

|

24.7 |

|

79.4 |