Submitted:

08 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Nomenclature and Biological Justification for Studying Such Higher-Order DNA Structural Motifs: G and C rich DNA Segments in Gene Control Regions Are Prone to Form Noncanonical DNA Secondary Structures in Competition with Duplex DNA

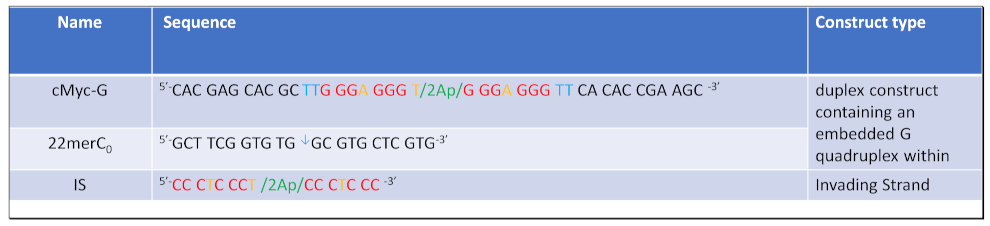

1.2. Rationale for Design of the System Studied

Spectroscopic Features of and Reasons for Studying the “mutated”/site altered cMyc Sequences

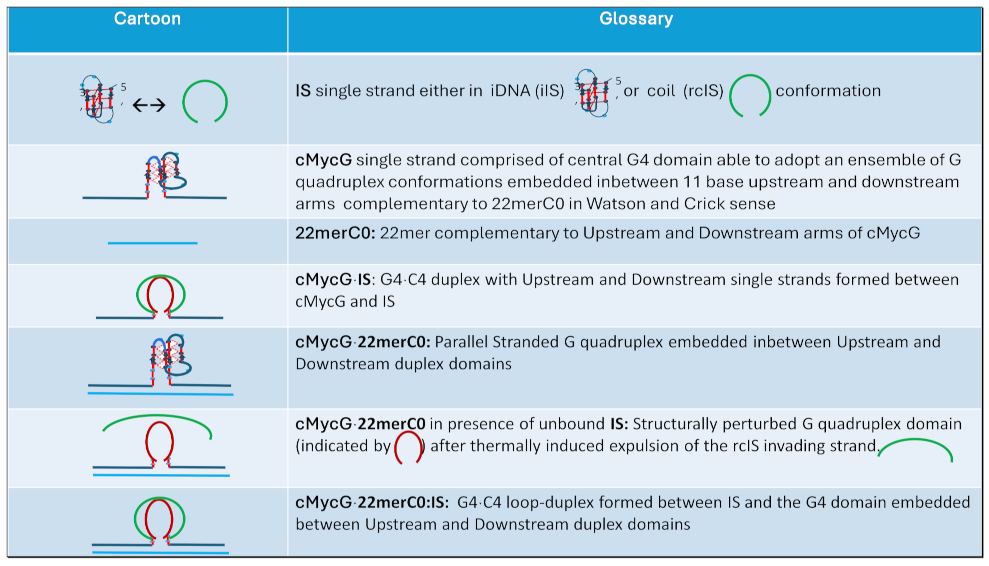

1.3. Glossary of Designated States

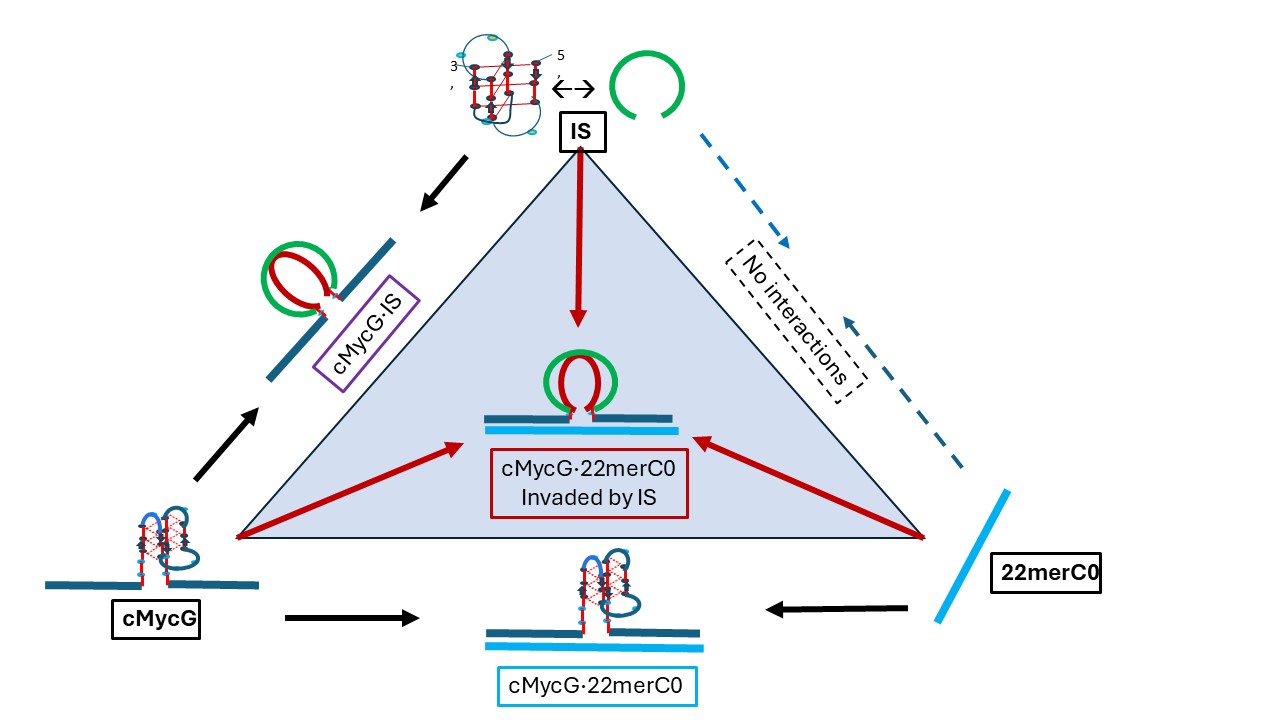

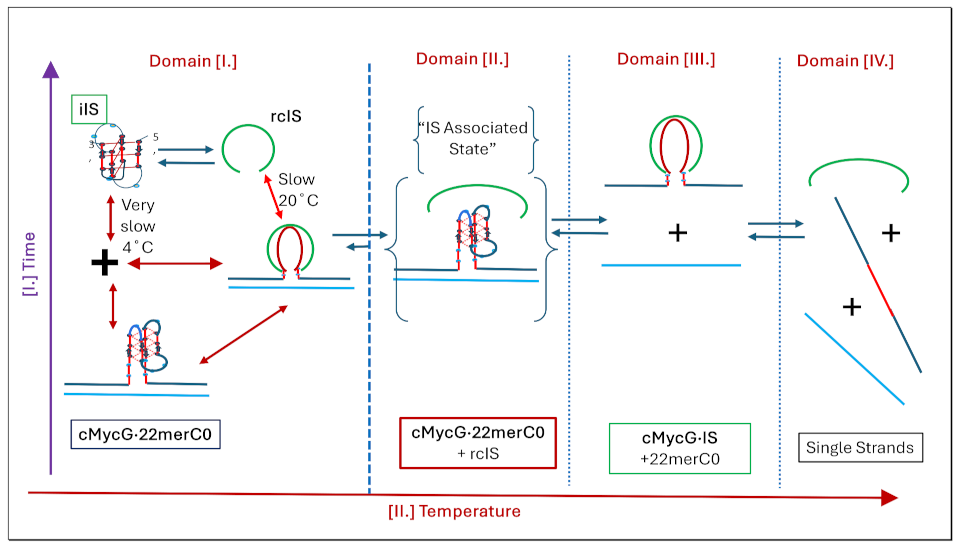

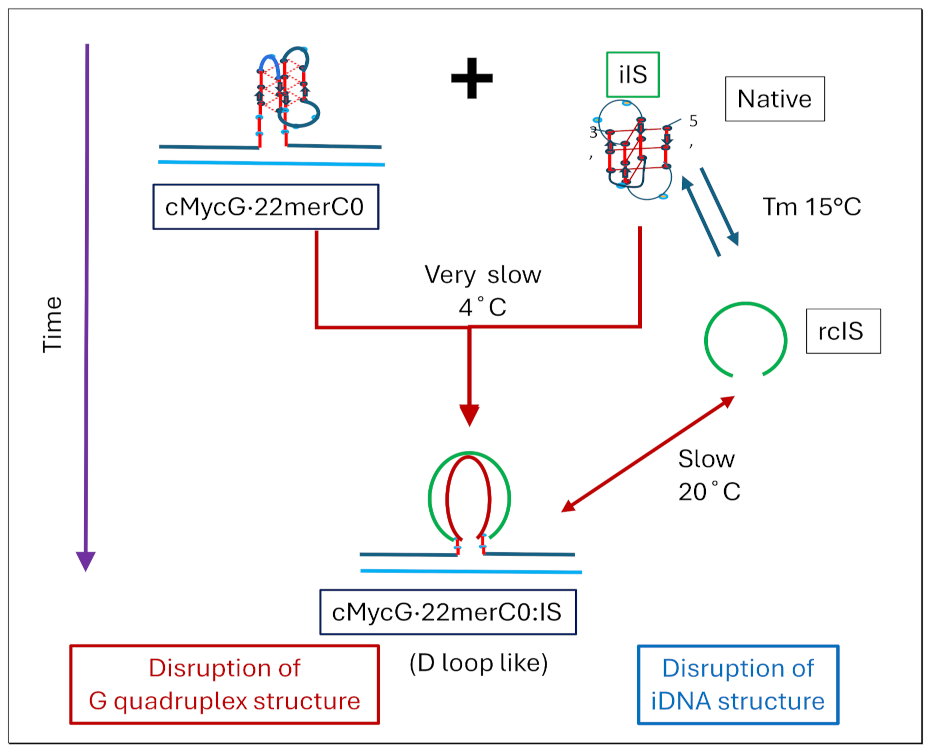

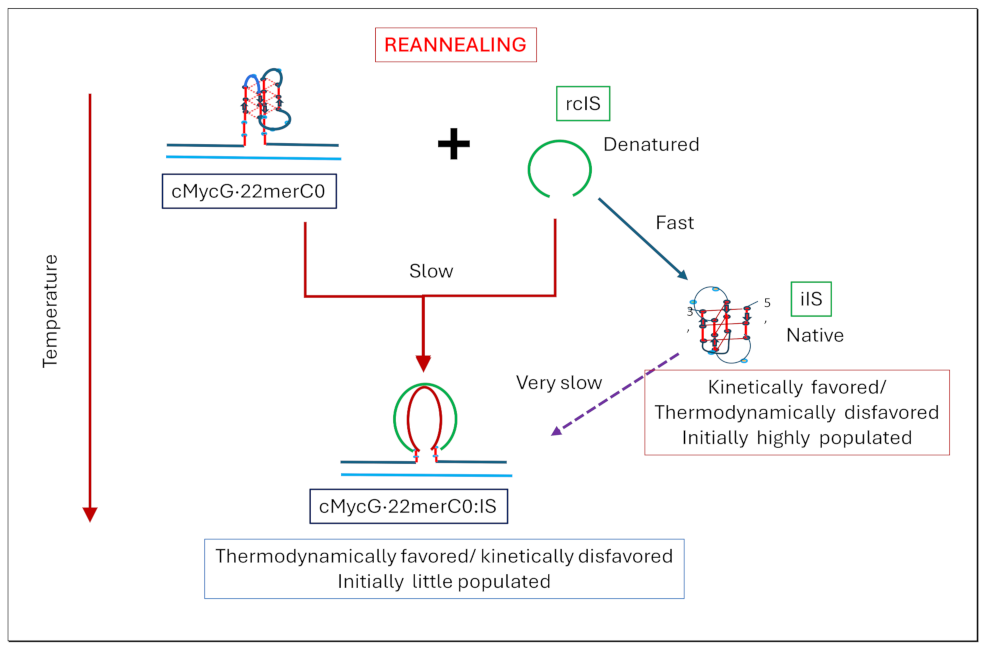

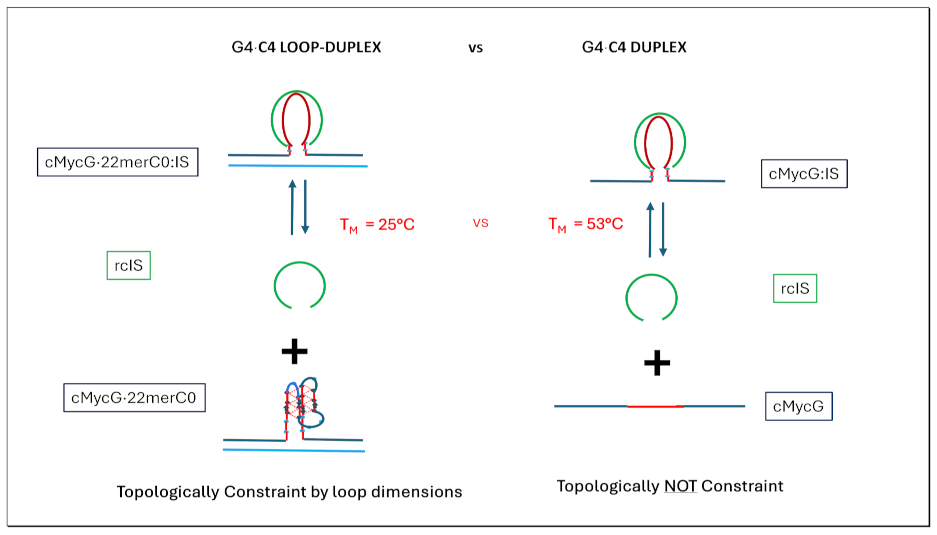

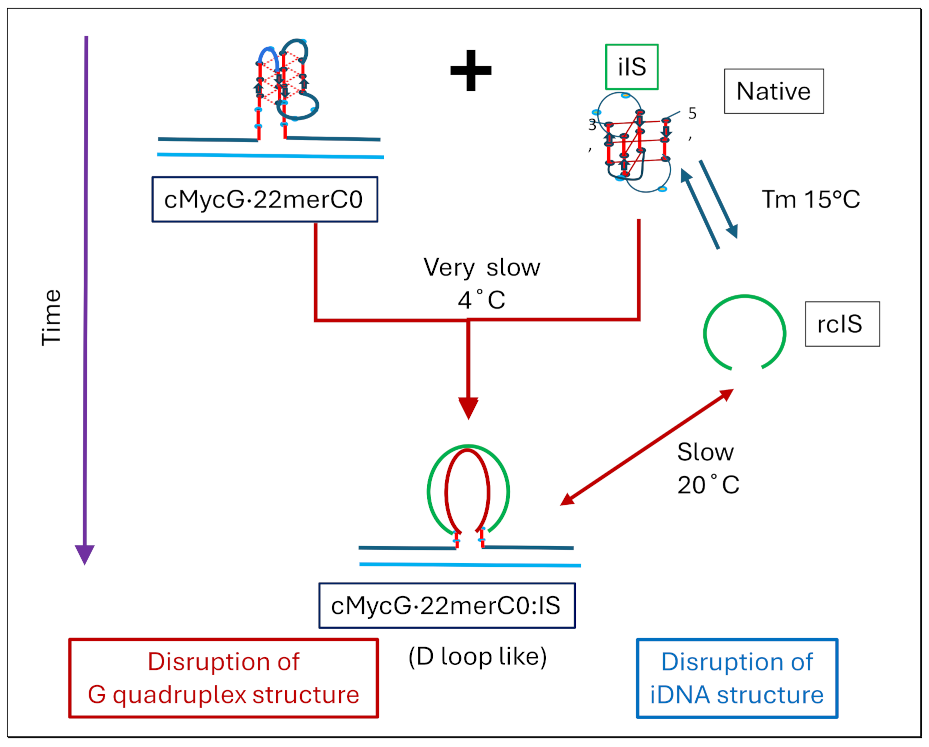

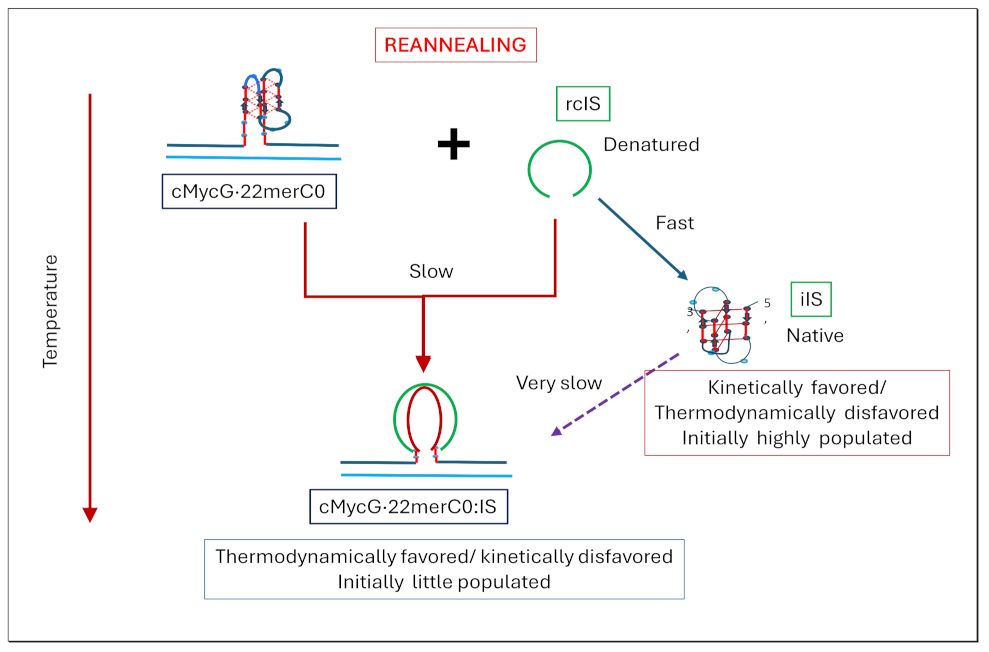

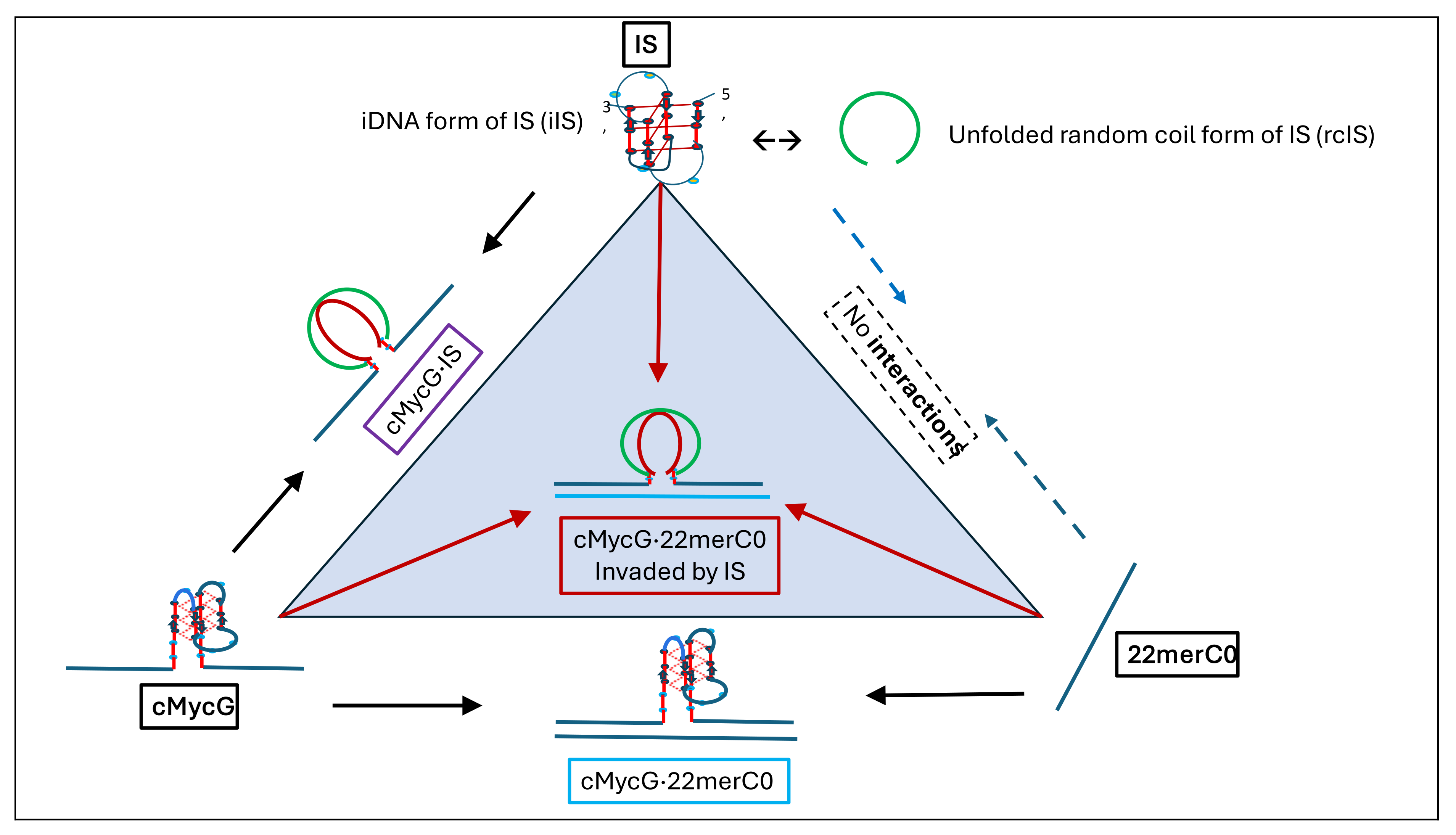

1.4. Summary Flow Charts:

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials:

2.2. Spectroscopy

3. Results and Discussion

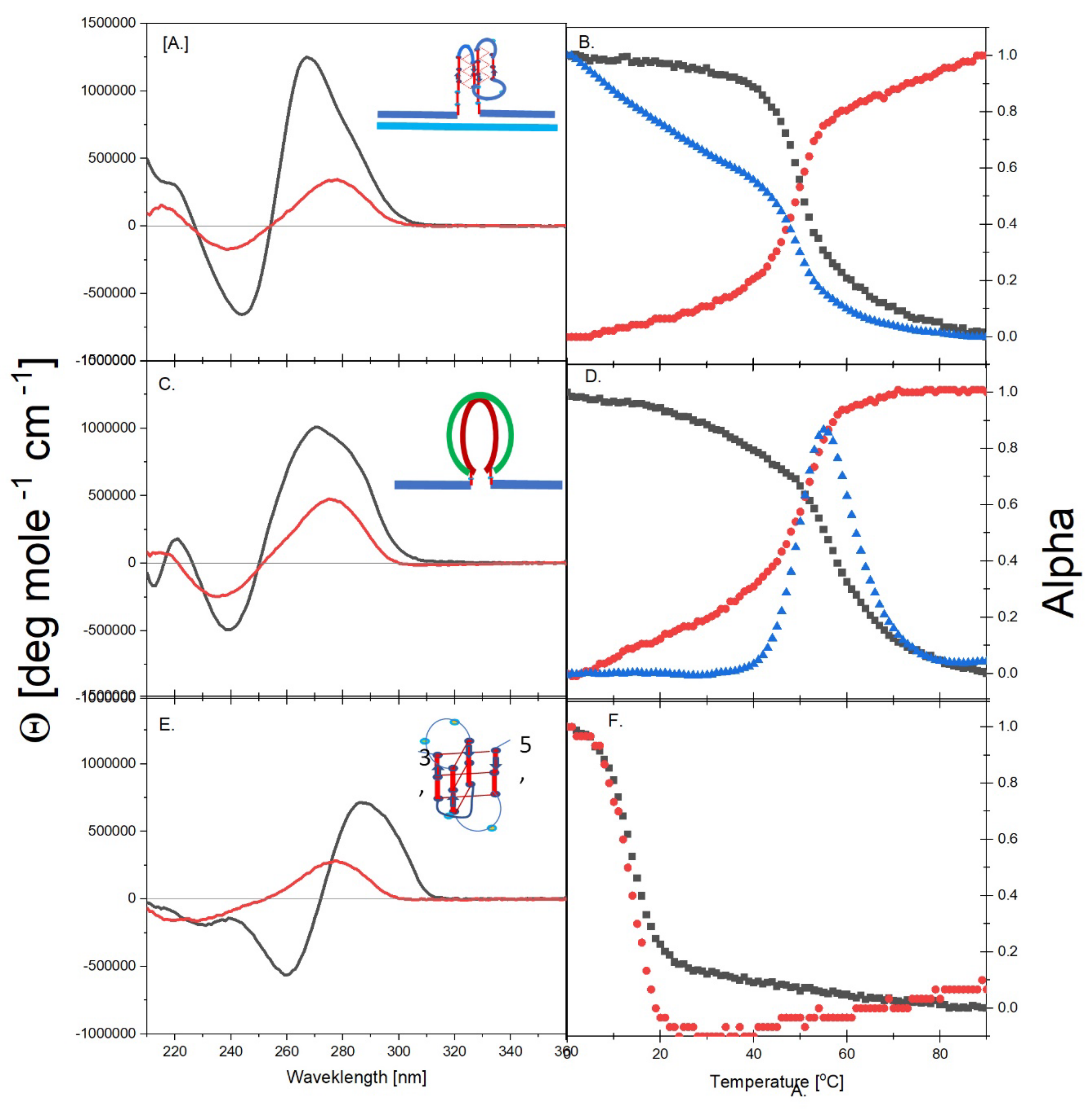

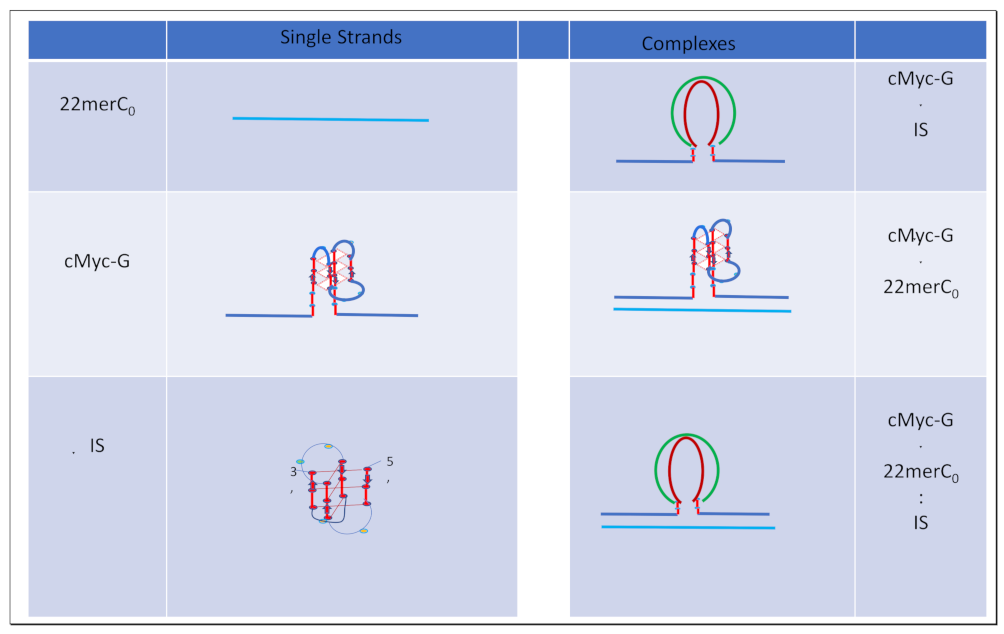

3.1. PART I. Background of the isolated DNA component species

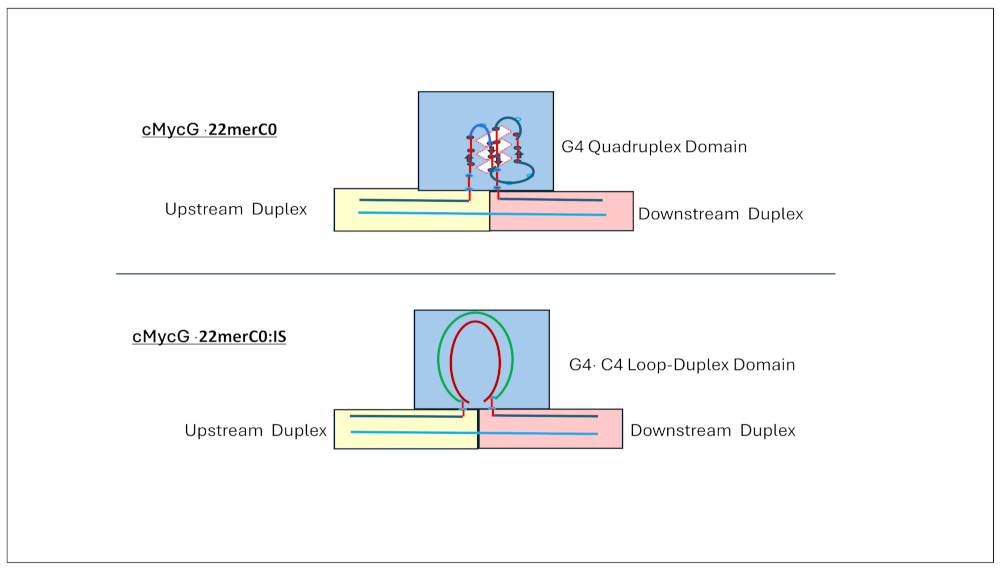

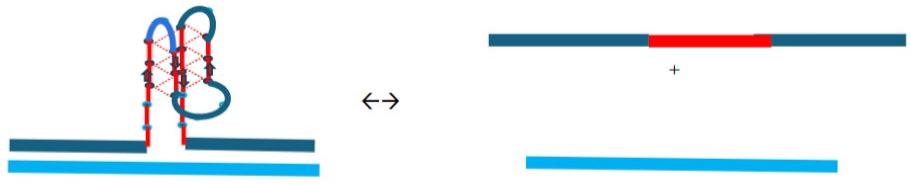

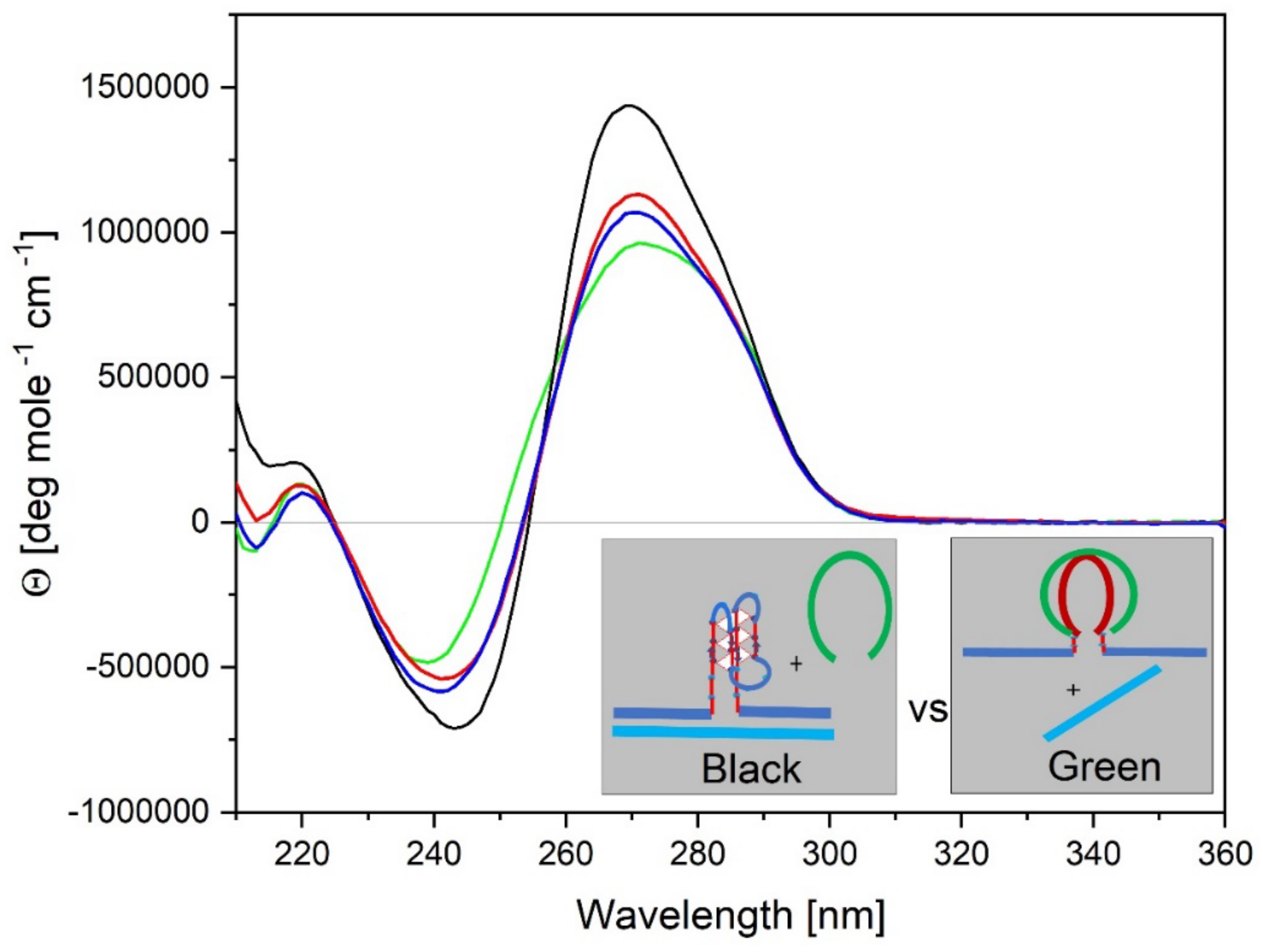

3.1.1. Spectroscopic Evidence for Formation of a Parallel Stranded G Quadruplex by cMycGˑ22merC0

3.1.2. Spectroscopic Evidence for the Formation of a Duplex with Overhanging Single Stranded Ends Between cMycG and IS

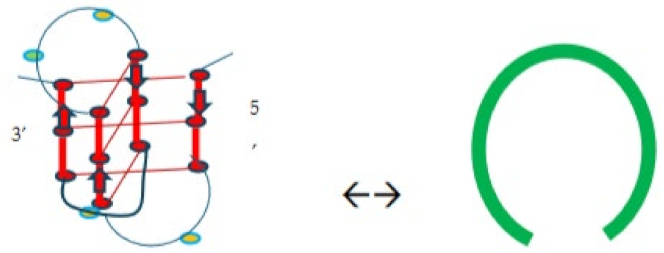

3.1.3. Spectroscopic Evidence for the Formation of an Unstable iDNA by IS

3.1.4. cMycGˑ22merC0, cMycGˑIS, and IS Exhibit Unique Spectroscopic Properties

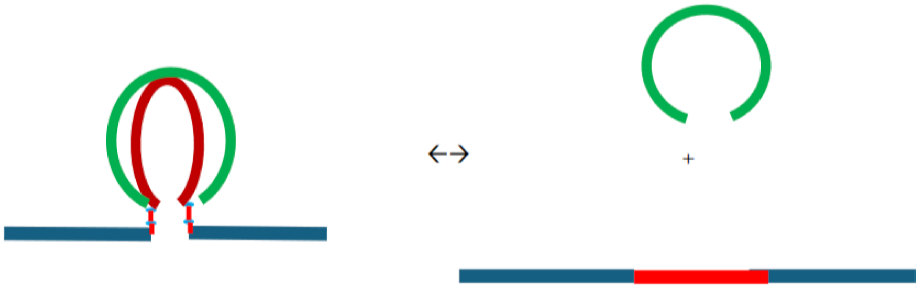

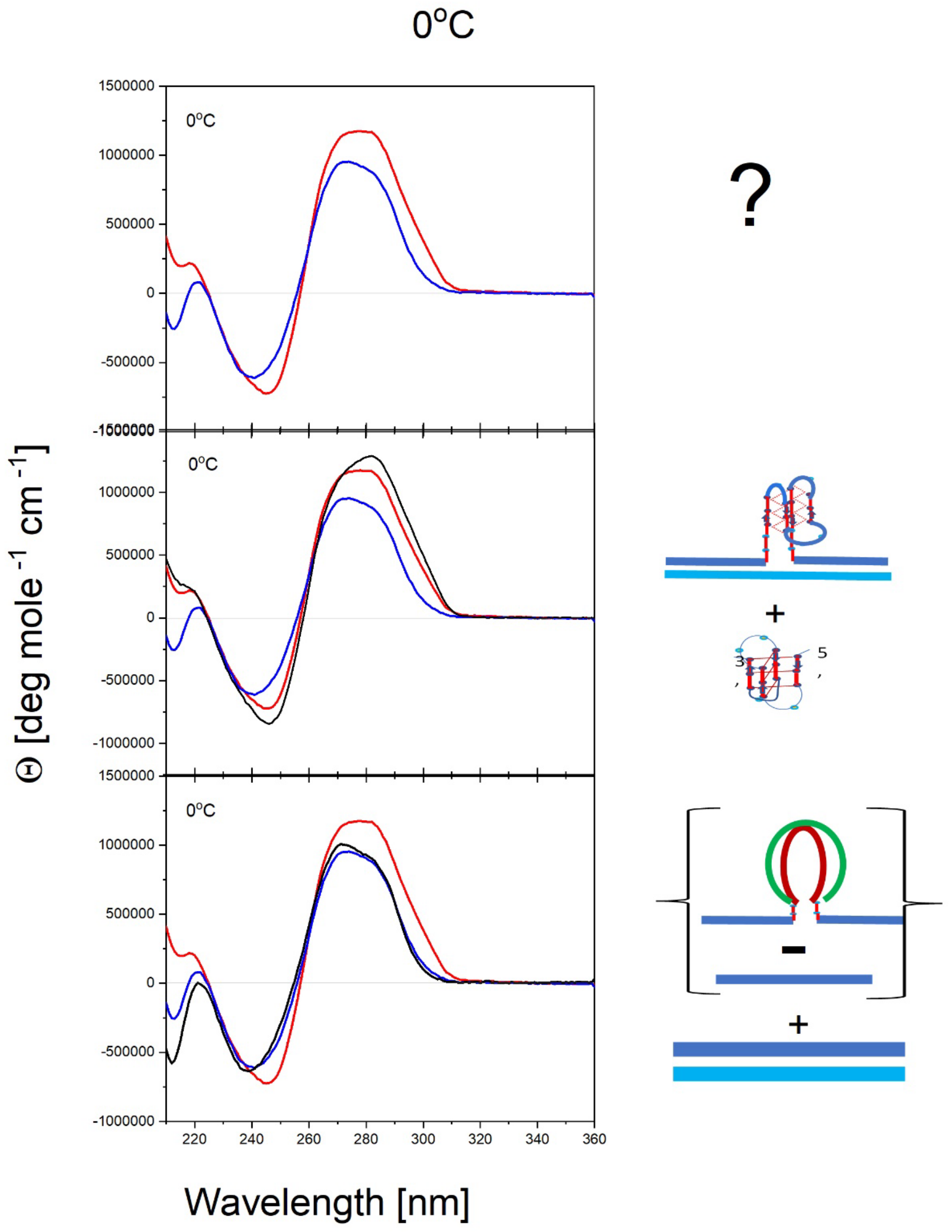

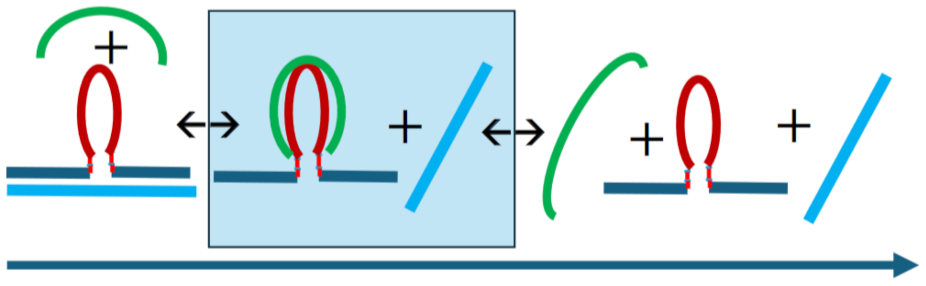

3.2. Part II: Spectroscopic Evidence for Strand Invasion of the G Quadruplex by IS

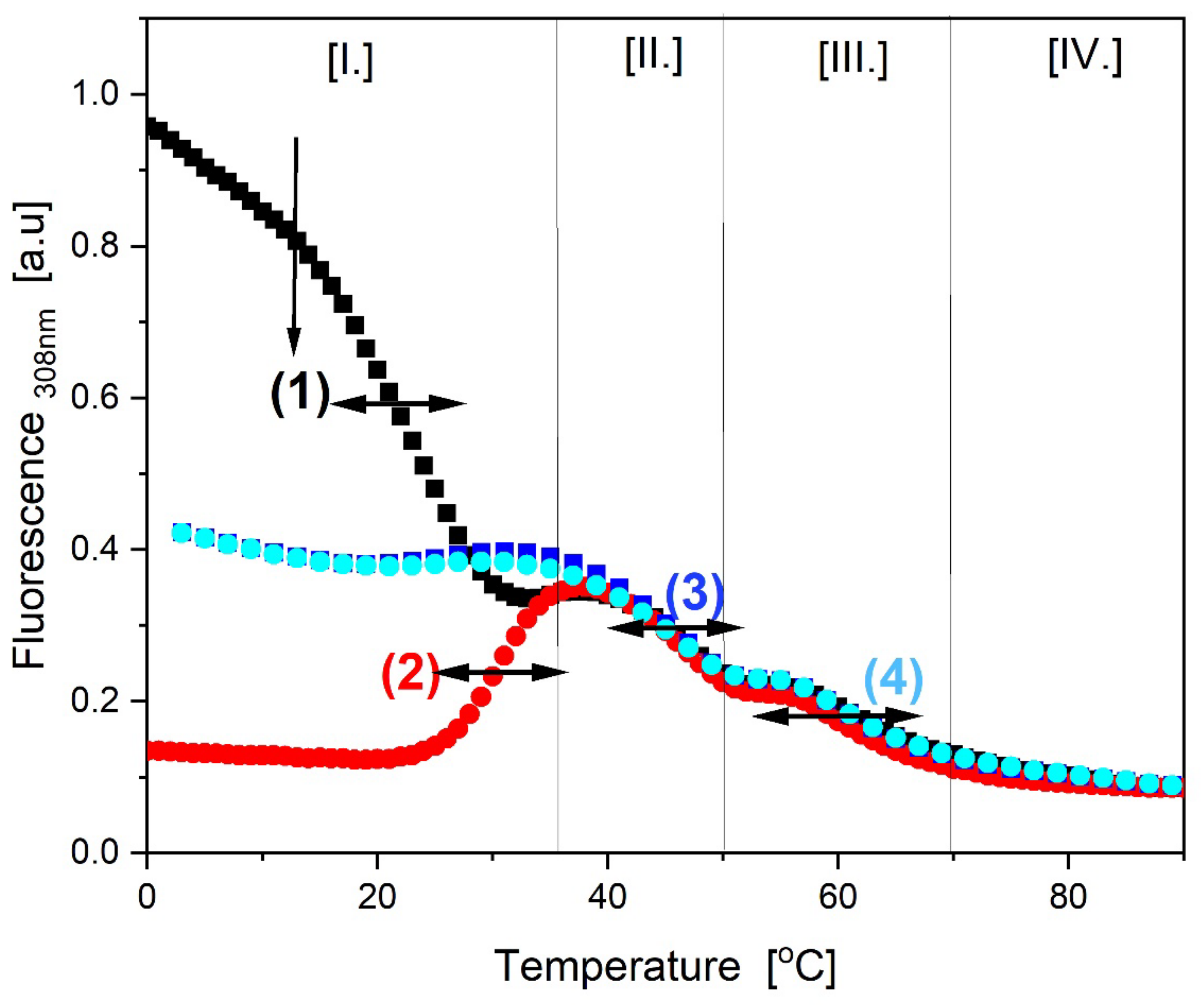

- All three spectral observables obtained immediately after mixing (black curves) differ from the spectral observables after incubation for 2 weeks at 4°C (red curves); with the most profound changes observed for the local 2Ap fluorescence probe inserted in the center of the G4 domain. By contrast, the 90°C denatured state spectra (dark blue and cyan) are indistinguishable, as one would expect for the fully denatured forms. These collective observations are consistent with slow interactions between cMycGˑ22merC0 and IS at the low incubation temperatures employed here. These conclusions are pictorially reflected in the corresponding Flowcharts.

- The associated melting curves reveal multiple transitions, with only the low temperature transition(s) depending on incubation times. In addition, the curves reveal hysteresis at low temperature upon heating and cooling. By contrast, the higher temperature transitions are identical for freshly prepared samples, and for those incubated at 4°C for 2 weeks prior to the melting experiments, and are completely reversible, as reflected by the identical heating and cooling curves. On the other hand, for all observables, the features of the initial low temperature transition depend strongly on the history of the sample, consistent with the pictorial representations within the relevant Flow Charts.

- While all optical observables reveal multiple temperature induced transitions, the 2Ap fluorescence melting curves exhibit the greatest resolution of identifiable transitions. We posit that this greater resolution, at least in part, results from the additional quenching of 2Ap by freely mobile guanines surrounding the 2Ap site following disruption of base paired/secondary structure elements involving the guanines that surround the local 2Ap residue [119,120,121,122,123] The implications of these results are further discussed in later sections.

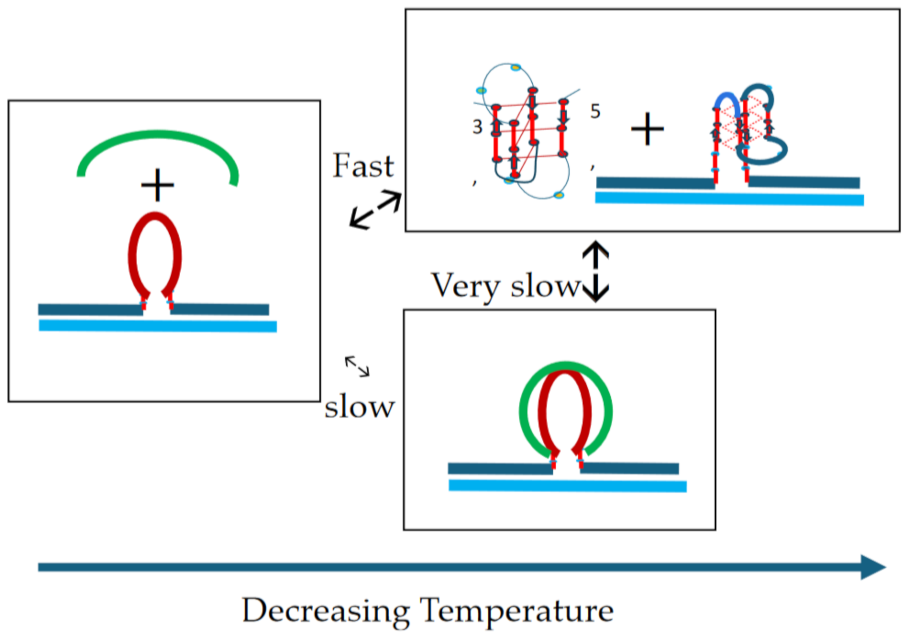

- The cooling /reannealing curves identically “reverse” the heating/melting transitions observed at high temperature, yet they diverge for the low temperature transition in a reproducible manner. Specifically, the reannealing curves fall in between the heating curves initially observed upon melting and those observed after preincubation at 4°C, while also exhibiting an intriguing and reproducible “wiggle” in the fluorescence annealing curves. Starting at the temperature where the heating and cooling curves begin to diverge during cooling, the 2Ap signal initially and gradually decreases to a temperature of about 20°C, whereas at lower temperatures the 2Ap fluorescence begins to increase again. The significance of this behavior is discussed below, while also being pictorially illustrated in the relevant Flow Charts.

- Particularly noteworthy, as previously underscored, and worth repeating for emphasis, is the impressive diversity of multiple DNA states we spectroscopically detect that can result from the comingling of just three oligonucleotides. We re-emphasize how the kinetic and thermodynamically controlled array of interacting species and their product complexes are dependent on temperature, time, sequence, and sample history/preparation, including incubation of individual species prior to mixing. We regularly allude to this recurring theme; namely, the range and complexity of coupled and uncoupled DNA states that can result from strand invasion events triggered by the co-mingling of a relatively few initial oligonucleotide species.

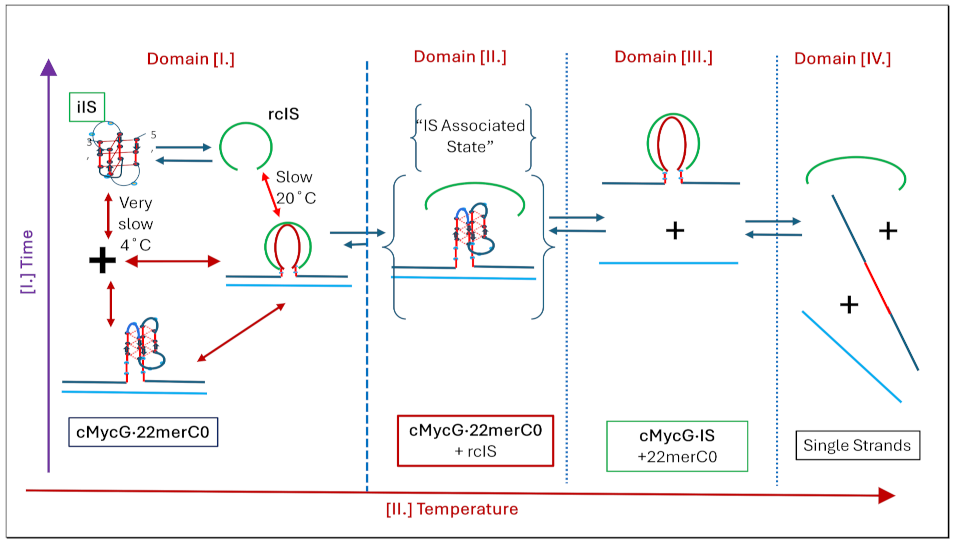

3.3. Part III: Towards a Globally Integrated Understanding of the Collective Observations

3.3.1. AP Fluorescence-Detected, Thermally-Induced Alterations in the G-Quadruplex Strand of the cMyGˑ22merC0 +IS Complex

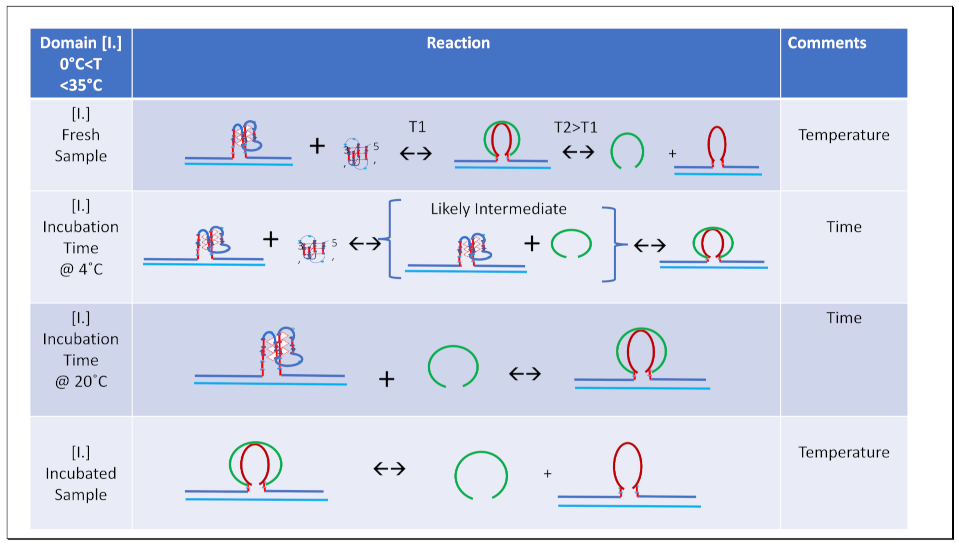

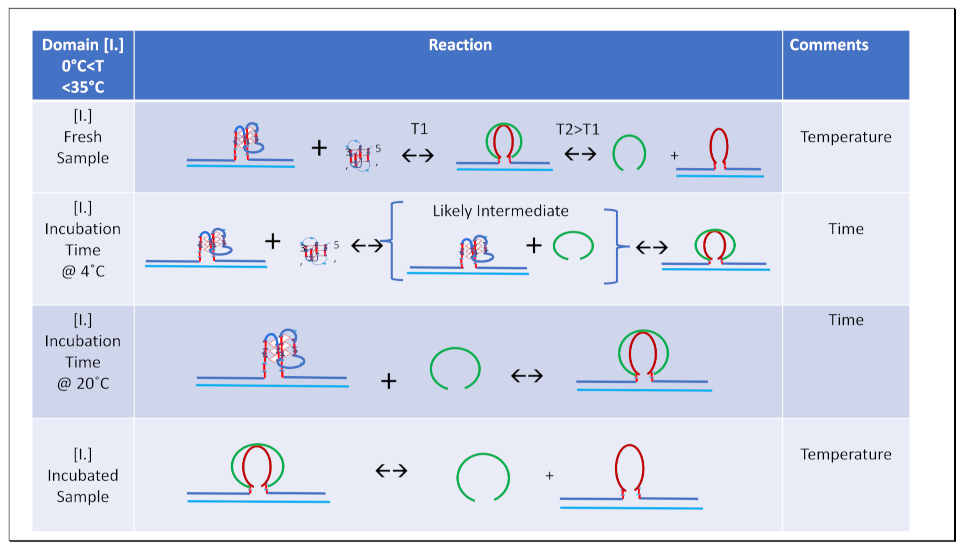

3.3.2. Temperature Domain [I.] Coupled Strand Invasion and Expulsion of the Invading IS Strand

- Comparison of cMycGˑ22merC0: IS with IS: Evidence for strand invasion by IS.

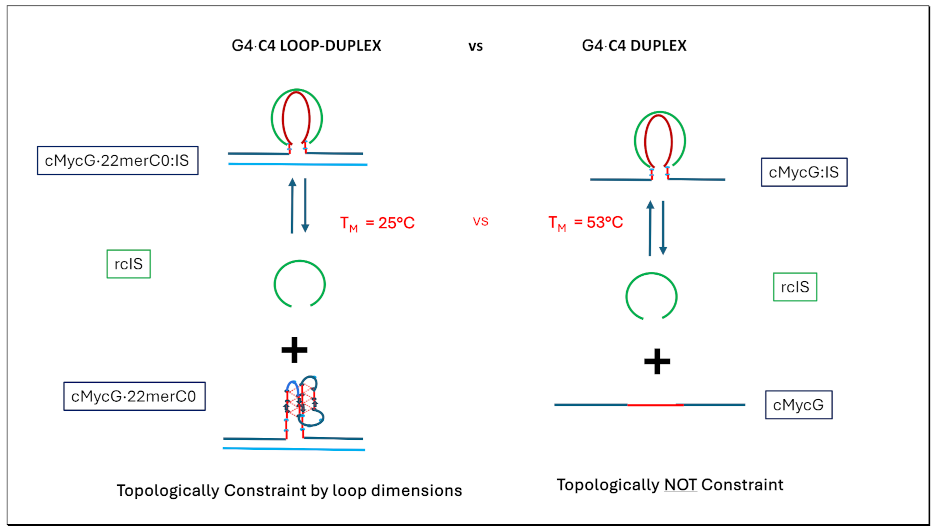

- Formation of the G4ˑC4 loop-duplex by strand invasion is kinetically inhibited but thermodynamically favored.

- Hysteresis in cooling curves reflects competing kinetic processes that occur at different relative rates and lead to population of metastable intermediates.

- (1)

- For a freshly prepared sample, we propose coupled transformations that correspond to the invasion of the G4 quadruplex by IS, likely via an unfolded intermediate, followed, at slightly higher temperature, by the melting of the G4ˑC4 loop-duplex.

- (2)

- For a sample incubated at 4°C, we propose formation of the G4ˑC4 loop-duplex, with the unfolded IS as a likely intermediate, coupled transformations that collectively exhibit complex kinetics.

- (3)

- For a sample incubated at 20°C, we propose formation of G4ˑC4 loop-duplex with slow, single exponential kinetics associated with IS invasion

- (4)

- For a sample preincubated at 4°C we propose melting of G4ˑC4 loop-duplex to form cMycGˑ22merC0 and IS. However, as we show in the next section, IS remains closely associated but not formally bound to cMycGˑ22merC0, leading to altered properties of the cMycGˑ22merC0 complex.

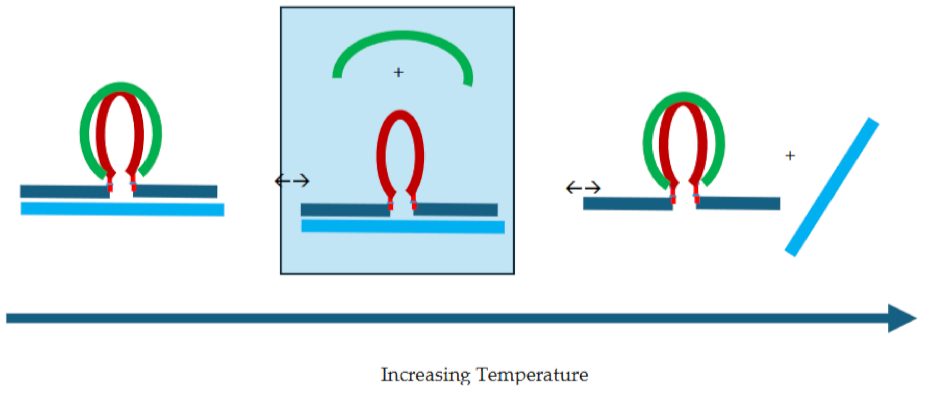

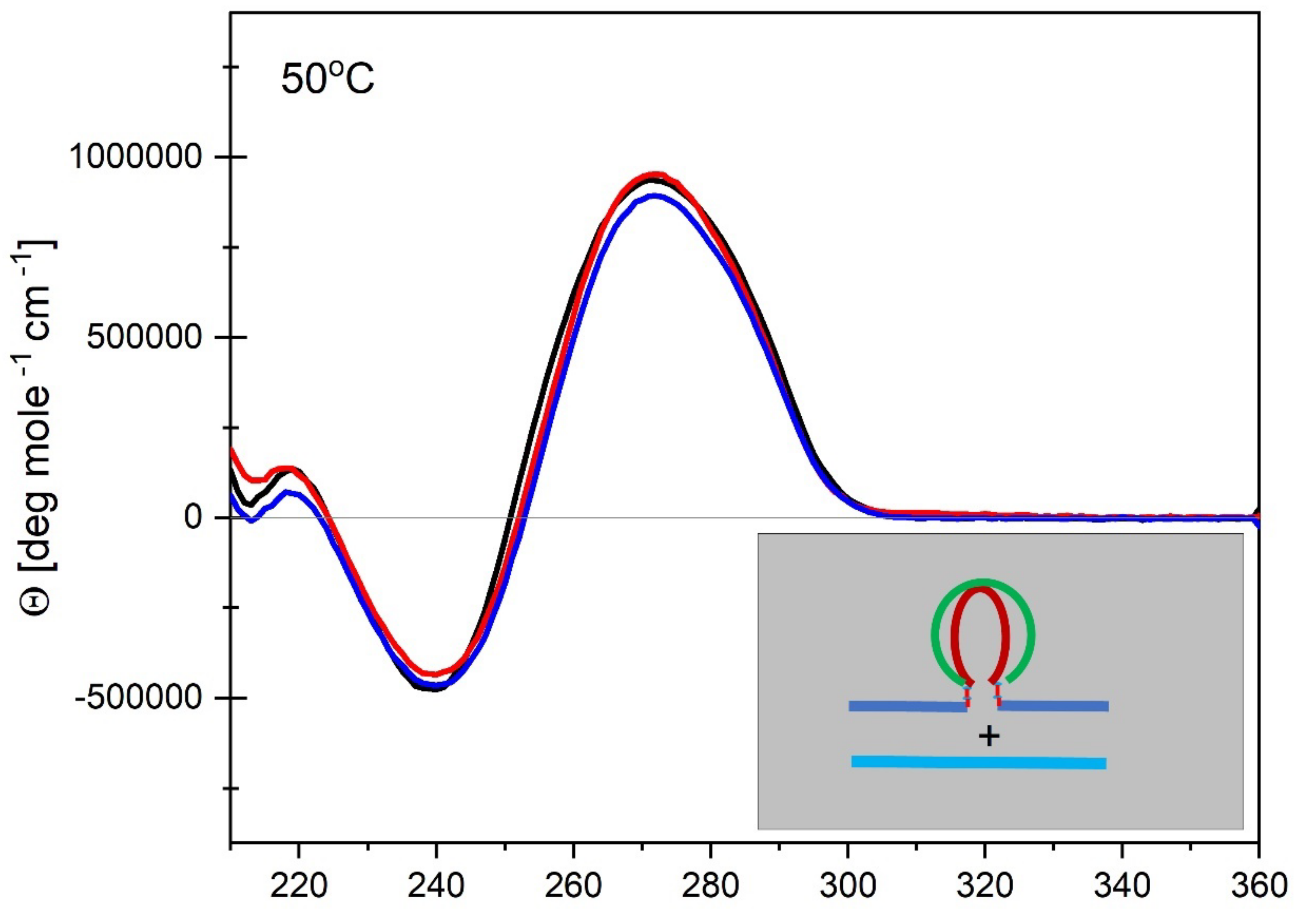

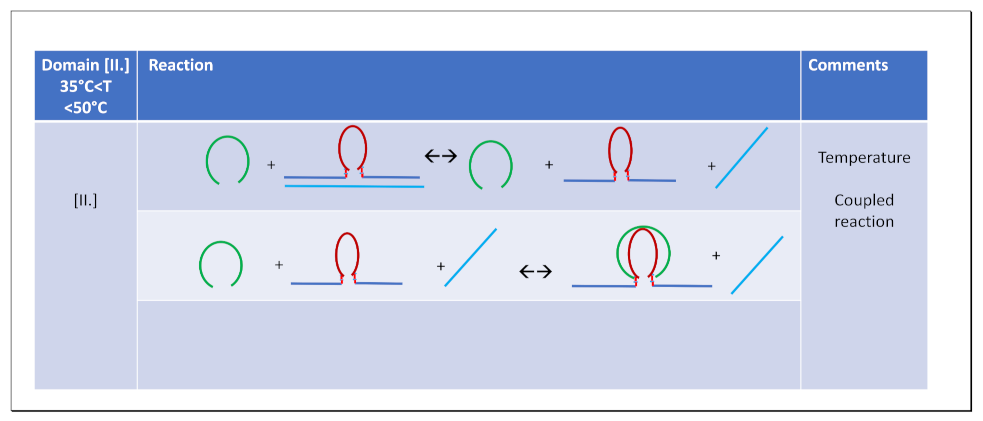

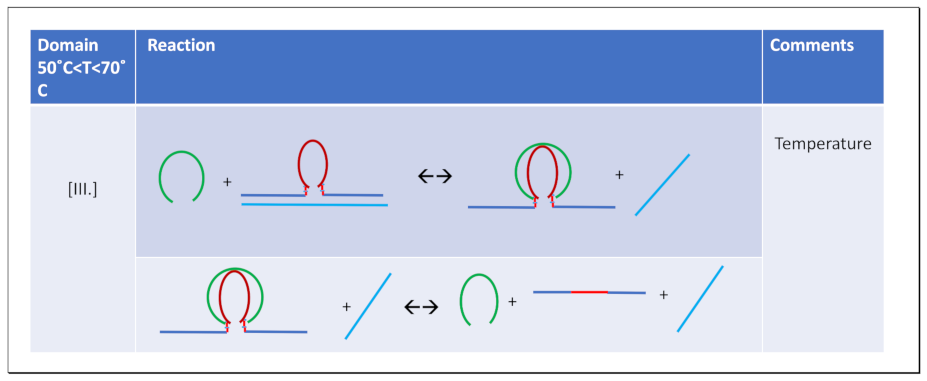

3.3.3. Temperature Domain [II.] cMycG·22merC0 in the Presence of IS

3.4. How IS Interacting with the G4 Quadruplex Domain Influences cMycGˑ22merC0 Properties

3.4.1. Invasion of the G4 Quadruplex is Kinetically Inhibited by the Quadruplex Fold as well as by The Self-Structure of the Invading Strand

3.4.2. The Product of Invasion of the G quadruplex by IS: The G4·C4 Loop-Duplex, Is Thermally less Stable than the Corresponding Linear G4·C4 duplex

3.4.3. Expulsion of the Invaded IS Strand Does not Allow Refolding of the G4 Quadruplex into the Conformation it Adopts Absent the Invading Strand

3.4.4. IS displaced from the G4·C4 Loop-Duplex Domain Can Reversibly Rebind cMycG After Melting of the cMycG·22merC0 Complex

3.4.5. The Hysteresis Upon Cooling Is Driven by Differential Rates of Interactions Between the Invasion complex and the IS Self-Structure

3.5. Integrating and Summarizing the Interactions Between the Multiplicity of DNA States

Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nussinov, R.; Wolynes, P.G. A second molecular biology revolution? The energy landscapes of biomolecular function. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2014, 16, 6321–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wales, D.J. Energy Landscape Applications to Clusters, Biomolecules and Glasses, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, 2004.

- Wales, D.J. Exploring Energy Landscapes. Annu Rev Phys Chem 2018, 69, 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Wang, J. Potential Energy Landscape and Robustness of a Gene Regulatory Network: Toggle Switch. PLOS Computational Biology 2007, 3, e60. [CrossRef]

- Prada-Gracia, D.; Gómez-Gardeñes, J.; Echenique, P.; Falo, F. Exploring the Free Energy Landscape: From Dynamics to Networks and Back. PLOS Computational Biology 2009, 5, e1000415. [CrossRef]

- Greive, S.J.; Von Hippel, P.H. Thinking quantitatively about transcriptional regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005, 6, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Vasquez, K.M. Dynamic alternative DNA structures in biology and disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 2023, 24, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos-Rodrigues, G.; Hisey, J.A.; Nussenzweig, A.; Mirkin, S.M. Detection of alternative DNA structures and its implications for human disease. Molecular Cell 2023, 83, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateishi-Karimata, H.; Sugimoto, N. Roles of non-canonical structures of nucleic acids in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, 7839–7855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacolla, A.; Wang, G.; Vasquez, K.M. New Perspectives on DNA and RNA Triplexes As Effectors of Biological Activity. PLOS Genetics 2015, 11, e1005696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacolla, A.; Wells, R.D. Non-B DNA conformations as determinants of mutagenesis and human disease. Mol Carcinog 2009, 48, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Iwasaki, W.; Hirota, K. The intrinsic ability of double-stranded DNA to carry out D-loop and R-loop formation. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2020, 18, 3350–3360. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2001037020304475. [CrossRef]

- Prado, F. Homologous Recombination: To Fork and Beyond. Genes 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejci, L.; Altmannova, V.; Spirek, M.; Zhao, X. Homologous recombination and its regulation. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, i.A.; Griffith, M.C.; Ramasamy, K.; Risen, L.M.; Freier, S.M. Inhibition of NF-κB specific transcriptional activation by PNA strand invasion. Nucleic Acids Res 1995, 23, 3003–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alecki, C.; Chiwara, V.; Sanz, L.A.; Grau, D.; Arias Pérez, O.; Boulier, E.L.; Armache, K.; Chédin, F.; Francis, N.J. RNA-DNA strand exchange by the Drosophila Polycomb complex PRC2. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehrs, C.; Luke, B. Regulatory R-loops as facilitators of gene expression and genome stability. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2020, 21, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulfridge, P.; Sarma, K. Intertwining roles of R-loops and G-quadruplexes in DNA repair, transcription and genome organization. Nat Cell Biol 2024, 26, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, J.D.; Comeau, L.; Rosenfield, S.; Stansel, R.M.; Bianchi, A.; Moss, H.; de Lange, T. Mammalian Telomeres End in a Large Duplex Loop. Cell 1999, 97, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.; Mergny, J.L.; Klump, H.H. From quadruplex to helix and back: Meta-stable states can move through a cycle of conformational changes. Arch Biochem Biophys 2008, 474, 8–14. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000398610700608X. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, T.A.; Kendrick, S.; Hurley, L. Making sense of G-quadruplex and i-motif functions in oncogene promoters. The FEBS Journal 2010, 277, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsen, R.C.; Deleeuw, L.W.; Dean, W.L.; Gray, R.D.; Chakravarthy, S.; Hopkins, J.B.; Chaires, J.B.; Trent, J.O. Long promoter sequences form higher-order G-quadruplexes: an integrative structural biology study of c-Myc, k-Ras and c-Kit promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathad, R.I.; Hatzakis, E.; Dai, J.; Yang, D. c-MYC promoter G-quadruplex formed at the 5′-end of NHE III 1 element: insights into biological relevance and parallel-stranded G-quadruplex stability. Nucleic Acids Research 2011, 39, 9023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Hurley, L.H. Structure of the Biologically Relevant G-Quadruplex in The c-MYC Promoter. Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids 2006, 25, 951. [CrossRef]

- Del mundo, I.M.A.; Zewail-Foote, M.; Kerwin, S.M.; Vasquez, K.M. Alternative DNA structure formation in the mutagenic human c-MYC promoter. Nucleic Acids Research 2017, 45, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N. The Interplay between G-quadruplex and Transcription. CMC 2019, 26, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, D.; Lipps, H.J. G-quadruplexes and their regulatory roles in biology. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murat, P.; Balasubramanian, S. Existence and consequences of G-quadruplex structures in DNA. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2013, 25, 22. [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, S.; Hurley, L.H. The role of G-quadruplex/i-motif secondary structures as cis-acting regulatory elements. 2010, 82, 1609–1621. [CrossRef]

- Bedrat, A.; Lacroix, L.; Mergny, J. Re-evaluation of G-quadruplex propensity with G4Hunter. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 1746–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, A.K.; Johnston, M.; Neidle, S. Highly prevalent putative quadruplex sequence motifs in human DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, 2901–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, J.L. Structure, location and interactions of G-quadruplexes. The FEBS Journal 2010, 277, 3452–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, J.L.; Balasubramanian, S. G-quadruplexes in promoters throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 35, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, J.; Maizels, N. Gene function correlates with potential for G4 DNA formation in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, 3887–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Halder, K.; Halder, R.; Yadav, V.K.; Rawal, P.; Thakur, R.K.; Mohd, F.; Sharma, A.; Chowdhury, S. Genome-Wide Computational and Expression Analyses Reveal G-Quadruplex DNA Motifs as Conserved cis-Regulatory Elements in Human and Related Species. J Med Chem 2008, 51, 5641–5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, S.; Parkinson, G.N.; Hazel, P.; Todd, A.K.; Neidle, S. Quadruplex DNA: sequence, topology and structure. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, 5402–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, K. A world beyond double-helical nucleic acids: the structural diversity of tetra-stranded G-quadruplexes. ChemTexts 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webba da Silva, M. Geometric Formalism for DNA Quadruplex Folding. Chemistry – A European Journal 2007, 13, 9738–9745. [CrossRef]

- Chalikian, T.V.; Liu, L.; Macgregor, J.,Robert, B. Duplex-tetraplex equilibria in guanine- and cytosine-rich DNA. Biophys Chem 2020, 267, 106473. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301462220301812. [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.D.; Trent, J.O.; Arumugam, S.; Chaires, J.B. Folding Landscape of a Parallel G-Quadruplex. J Phys Chem Lett 2019, 10, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Hurley, L.H. Structures, folding patterns, and functions of intramolecular DNA G-quadruplexes found in eukaryotic promoter regions. Biochimie 2008, 90, 1149–1171. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0300908408000540. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.; Roy, S.; Srivatsan, S.G. Probing the Competition between Duplex, G-Quadruplex and i-Motif Structures of the Oncogenic c-Myc DNA Promoter Region. Chem Asian J 2023, 18, e202300510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Park, H. Novel Molecular Mechanism for Actinomycin D Activity as an Oncogenic Promoter G-Quadruplex Binder. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 7392–7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, T.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Tan, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, D.; Wong, K.; Tang, J.C.; et al. Stabilization of G-Quadruplex DNA and Down-Regulation of Oncogene c-myc by Quindoline Derivatives. J Med Chem 2007, 50, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broxson, C.; Beckett, J.; Tornaletti, S. Transcription Arrest by a G Quadruplex Forming-Trinucleotide Repeat Sequence from the Human c-myb Gene. Biochemistry (N Y) 2011, 50, 4162–4172. [CrossRef]

- Belotserkovskii, B.P.; Mirkin, S.M.; Hanawalt, P.C. DNA Sequences That Interfere with Transcription: Implications for Genome Function and Stability. Chem Rev 2013, 113, 8620–8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esain-Garcia, I.; Kirchner, A.; Melidis, L.; Tavares, R.D.C.A.; Dhir, S.; Simeone, A.; Yu, Z.; Madden, S.K.; Hermann, R.; Tannahill, D.; et al. G-quadruplex DNA structure is a positive regulator of MYC transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, J.; Cuesta, S.M.; Adhikari, S.; Hänsel-Hertsch, R.; Tannahill, D.; Balasubramanian, S. G-quadruplexes are transcription factor binding hubs in human chromatin. Genome Biol 2021, 22, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Spiegel, J.; Martínez Cuesta, S.; Adhikari, S.; Balasubramanian, S. Chemical profiling of DNA G-quadruplex-interacting proteins in live cells. Nature Chemistry 2021, 13, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.; Raguseo, F.; Nuccio, S.P.; Liano, D.; Di antonio, M. DNA G-quadruplex structures: more than simple roadblocks to transcription? Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, 8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, R.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Qin, Z.S.; Sun, X. Integrative characterization of G-Quadruplexes in the three-dimensional chromatin structure. Epigenetics 2019, 14, 894–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Kendrick, S.; Hecht, S.M.; Hurley, L.H. The Transcriptional Complex Between the BCL2 i-Motif and hnRNP LL Is a Molecular Switch for Control of Gene Expression That Can Be Modulated by Small Molecules. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136, 4172–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendrick, S.; Kang, H.; Alam, M.P.; Madathil, M.M.; Agrawal, P.; Gokhale, V.; Yang, D.; Hecht, S.M.; Hurley, L.H. The Dynamic Character of the BCL2 Promoter i-Motif Provides a Mechanism for Modulation of Gene Expression by Compounds That Bind Selectively to the Alternative DNA Hairpin Structure. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136, 4161–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Yu, Z.; Konik, R.; Cui, Y.; Koirala, D.; Mao, H. G-Quadruplex and i-Motif Are Mutually Exclusive in ILPR Double-Stranded DNA. Biophysical Journal 2012, 102, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, C.; Cui, Y.; Mao, H.; Hurley, L.H. A Mechanosensor Mechanism Controls the G-Quadruplex/i-Motif Molecular Switch in the MYC Promoter NHE III1. J Am Chem Soc 2016, 138, 14138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Kong, D.; Ghimire, C.; Xu, C.; Mao, H. Mutually Exclusive Formation of G-Quadruplex and i-Motif Is a General Phenomenon Governed by Steric Hindrance in Duplex DNA. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.J.; Irving, K.L.; Evans, C.W.; Chikhale, R.V.; Becker, R.; Morris, C.J.; Peña Martinez, C.D.; Schofield, P.; Christ, D.; Hurley, L.H.; et al. DNA G-Quadruplex and i-Motif Structure Formation Is Interdependent in Human Cells. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 20600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui-Jain, A.; Grand, C.L.; Bearss, D.J.; Hurley, L.H. Direct evidence for a G-quadruplex in a promoter region and its targeting with a small molecule to repress c-MYC transcription. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 11593–11598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, T.A.; Hurley, L.H. Targeting MYC Expression through G-Quadruplexes. Genes & Cancer 2010, 1, 641–649. [CrossRef]

- Murat, P.; Balasubramanian, S. Existence and consequences of G-quadruplex structures in DNA. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2014, 25, 22–29. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959437X13001494. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, E.Y.N.; Beraldi, D.; Tannahill, D.; Balasubramanian, S. G-quadruplex structures are stable and detectable in human genomic DNA. Nature Communications 2013, 4, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, A.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Chavez, E.A.; Platt, J.; Johnson, F.B.; Brosh, R.M.; Sen, D.; Lansdorp, P.M. Detection of G-quadruplex DNA in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 42, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biffi, G.; Tannahill, D.; McCafferty, J.; Balasubramanian, S. Quantitative visualization of DNA G-quadruplex structures in human cells. Nature Chemistry 2013, 5, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Neidle, S. G-quadruplex nucleic acids as therapeutic targets. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2009, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Hurley, L.H.; Neidle, S. Targeting G-quadruplexes in gene promoters: a novel anticancer strategy? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidle, S. Quadruplex nucleic acids as targets for anticancer therapeutics. Nature Reviews Chemistry 2017, 1, 0041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hurley, L.H.; Schaefer, H.J. PIIS0165614700014577.

- Carvalho, J.; Mergny, J.; Salgado, G.F.; Queiroz, J.A.; Cruz, C. G-quadruplex, Friend or Foe: The Role of the G-quartet in Anticancer Strategies. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2020, 26, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Kotar, A.; Tateishi-Karimata, H.; Bhowmik, S.; Wang, Z.; Chang, T.; Sato, S.; Takenaka, S.; Plavec, J.; Sugimoto, N. Chemical Modulation of DNA Replication along G-Quadruplex Based on Topology-Dependent Ligand Binding. J Am Chem Soc 2021, 143, 16458–16469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.; Chalikian, T.V. Stabilization of G-Quadruplex-Duplex Hybrid Structures Induced by Minor Groove-Binding Drugs. Life 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dubins, D.N.; Völker, J.; Chalikian, T.V. G-Quadruplex Recognition by Tetraalkylammonium Ions: A New Paradigm for Discrimination between Parallel and Antiparallel G-Quadruplexes. J Phys Chem B 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, B.A. The impact of nucleic acid secondary structure on PNA hybridization. Drug Discov Today 2003, 8, 222–228. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359644603026114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, A.; Nordén, B. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA): its medical and biotechnical applications and promise for the future. The FASEB Journal 2000, 14, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittung, P.; Nielsen, P.; Nordén, B. Direct Observation of Strand Invasion by Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) into Double-Stranded DNA. J Am Chem Soc 1996, 118, 7049–7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratilainen, T.; Holmén, A.; Tuite, E.; Nielsen, P.E.; Nordén, B. Thermodynamics of Sequence-Specific Binding of PNA to DNA. Biochemistry (N Y) 2000, 39, 7781–7791. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Lee, L.; Roy, S.; Tanious, F.A.; Wilson, W.D.; Ly, D.H.; Armitage, B.A. Strand Invasion of DNA Quadruplexes by PNA: Comparison of Homologous and Complementary Hybridization. ChemBioChem 2013, 14, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyshchenko, M.I.; Gaynutdinov, T.I.; Englund, E.A.; Appella, D.H.; Neumann, R.D.; Panyutin, I.G. Stabilization of G-quadruplex in the BCL2 promoter region in double-stranded DNA by invading short PNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2009, 37, 7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, E.A.; Gupta, P.; Micklitsch, C.M.; Onyshchenko, M.I.; Remeeva, E.; Neumann, R.D.; Panyutin, I.G.; Appella, D.H. PPG Peptide Nucleic Acids that Promote DNA Guanine Quadruplexes. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 1887–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, V.; Hurley, L.H. The c-MYCNHE III1: Function and Regulation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2009, 50, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.G.; Evans, H.M.; Dubins, D.N.; Chalikian, T.V. Effects of Salt on the Stability of a G-Quadruplex from the Human c-MYC Promoter. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 3420–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, A.; Chen, D.; Dai, J.; Jones, R.A.; Yang, D. Solution Structure of the Biologically Relevant G-Quadruplex Element in the Human c-MYC Promoter. Implications for G-Quadruplex Stabilization. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 2048–2058. [CrossRef]

- Jana, J.; Weisz, K. A Thermodynamic Perspective on Potential G-Quadruplex Structures as Silencer Elements in the MYC Promoter. Chem Eur J 2020, 26, 17242–17251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grün, J.T.; Blümler, A.; Burkhart, I.; Wirmer-Bartoschek, J.; Heckel, A.; Schwalbe, H. Unraveling the Kinetics of Spare-Tire DNA G-Quadruplex Folding. J Am Chem Soc 2021, 143, 6185–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grün, J.T.; Schwalbe, H. Folding dynamics of polymorphic G-quadruplex structures. Biopolymers 2022, 113, e23477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grün, J.T.; Hennecker, C.; Klötzner, D.; Harkness, R.W.; Bessi, I.; Heckel, A.; Mittermaier, A.K.; Schwalbe, H. Conformational Dynamics of Strand Register Shifts in DNA G-Quadruplexes. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freyer, M.W.; Buscaglia, R.; Kaplan, K.; Cashman, D.; Hurley, L.H.; Lewis, E.A. Biophysical Studies of the c-MYC NHE III1 Promoter: Model Quadruplex Interactions with a Cationic Porphyrin. Biophysical Journal 2007, 92, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzakis, E.; Okamoto, K.; Yang, D. Thermodynamic Stability and Folding Kinetics of the Major G-Quadruplex and Its Loop Isomers Formed in the Nuclease Hypersensitive Element in the Human c-Myc Promoter: Effect of Loops and Flanking Segments on the Stability of Parallel-Stranded Intramolecular G-Quadruplexes. Biochemistry (N Y) 2010, 49, 9152–9160. [CrossRef]

- Law, S.M.; Eritja, R.; Goodman, M.F.; Breslauer, K.J. Spectroscopic and Calorimetric Characterizations of DNA Duplexes Containing 2-Aminopurine. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 12329–12337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J.; Barch, M.; Castner, E.W.; Volker, J.; Breslauer, K.J. Structure and dynamics in DNA looped domains: CAG triplet repeat sequence dynamics probed by 2-aminopurine fluorescence. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 10756–10766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.D.; Petraccone, L.; Trent, J.O.; Chaires, J.B. Characterization of a K+-Induced Conformational Switch in a Human Telomeric DNA Oligonucleotide Using 2-Aminopurine Fluorescence. Biochemistry (N Y) 2010, 49, 179–194. [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.D.; Petraccone, L.; Buscaglia, R.; Chaires, J.B. 2-Aminopurine as a Probe for Quadruplex Loop Structures. In G-Quadruplex DNA: Methods and Protocols; Baumann, P., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Buscaglia, R.; Jameson, D.M.; Chaires, J.B. G-quadruplex structure and stability illuminated by 2-aminopurine phasor plots. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 4203–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Kawai, K.; Fujitsuka, M.; Majima, T. Monitoring G-quadruplex structures and G-quadruplex–ligand complex using 2-aminopurine modified oligonucleotides. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 3585–3590. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040402007001755. [CrossRef]

- Volker, J.; Plum, G.E.; Gindikin, V.; Klump, H.H.; Breslauer, K.J. Impact of bulge loop size on DNA triplet repeat domains: Implications for DNA repair and expansion. Biopolymers 2014, 101, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, J.; Gindikin, V.; Klump, H.H.; Plum, G.E.; Breslauer, K.J. Energy landscapes of dynamic ensembles of rolling triplet repeat bulge loops: implications for DNA expansion associated with disease states. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 6033–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, J.; Plum, G.E.; Klump, H.H.; Breslauer, K.J. DNA repair and DNA triplet repeat expansion: the impact of abasic lesions on triplet repeat DNA energetics. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131, 9354–9360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volker, J.; Klump, H.H.; Breslauer, K.J. DNA metastability and biological regulation: conformational dynamics of metastable omega-DNA bulge loops. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2007, 129, 5272–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, J.; Plum, G.E.; Gindikin, V.; Breslauer, K.J. Dynamic DNA Energy Landscapes and Substrate Complexity in Triplet Repeat Expansion and DNA Repair. Biomolecules 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Gehring, K.; Leroy, J.; Guéron, M. A tetrameric DNA structure with protonated cytosine-cytosine base pairs. Nature 1993, 363, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guéron, M.; Leroy, J. The i-motif in nucleic acids. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2000, 10, 326–331. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959440X00000919. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Assi, H.; Garavís, M.; González, C.; Damha, M.J. i-Motif DNA: structural features and significance to cell biology. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, 8038–8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergny, J.; Lacroix, L.; Han, X.; Leroy, J.; Helene, C. Intramolecular folding of pyrimidine oligodeoxynucleotides into an i-DNA motif. J Am Chem Soc 1995, 117, 8887–8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, J.; Klump, H.H.; Breslauer, K.J. The energetics of i-DNA tetraplex structures formed intermolecularly by d(TC5) and intramolecularly by d[(C5T3)3C5. Biopolymers 2007, 86, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, F.D.; Snell, C.T. Colorimetric methods of analysis, including some turbidimetric and nephelometric methods, R.E. Krieger Pub. Co: Huntington, N.Y., 1972; pp. v.

- Plum, G.E. Optical Methods. Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry 2000, 00, 7.3.1–7.3.17. [CrossRef]

- Völker, J.; Breslauer, K.J. Differential repair enzyme-substrate selection within dynamic DNA energy landscapes. Q Rev Biophys 2022, 55, e1. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/differential-repair-enzymesubstrate-selection-within-dynamic-dna-energy-landscapes/1CD6DD4B6383DDBFA6C81899552C4C03. [CrossRef]

- del Villar-Guerra, R.; Trent, J.O.; Chaires, J.B. G-Quadruplex Secondary Structure Obtained from Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed 2018, 57, 7171–7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Villar-Guerra, R.; Gray, R.D.; Chaires, J.B. Characterization of Quadruplex DNA Structure by Circular Dichroism. Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry 2017, 68, 17.8.1–17.8.16. [CrossRef]

- Vorlíčková, M.; Kejnovská, I.; Bednářová, K.; Renčiuk, D.; Kypr, J. Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy of DNA: From Duplexes to Quadruplexes. Chirality 2012, 24, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kypr, J.; Kejnovská, I.; Renčiuk, D.; Vorlíčková, M. Circular dichroism and conformational polymorphism of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, A.T.; Modi, Y.S.; Patel, D.J. Propeller-Type Parallel-Stranded G-Quadruplexes in the Human c-myc Promoter. J Am Chem Soc 2004, 126, 8710–8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.G.; Evans, H.M.; Dubins, D.N.; Chalikian, T.V. Effects of Salt on the Stability of a G-Quadruplex from the Human c-MYC Promoter. Biochemistry (N Y) 2015, 54, 3420–3430. [CrossRef]

- Seenisamy, J.; Rezler, E.M.; Powell, T.J.; Tye, D.; Gokhale, V.; Joshi, C.S.; Siddiqui-Jain, A.; Hurley, L.H. The Dynamic Character of the G-Quadruplex Element in the c-MYC Promoter and Modification by TMPyP4. J Am Chem Soc 2004, 126, 8702–8709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Ma, C.; Wells, J.W.; Chalikian, T.V. Conformational Preferences of DNA Strands from the Promoter Region of the c-MYC Oncogene. J Phys Chem B 2020, 124, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhu, L.; Tong, H.; Su, C.; Wells, J.W.; Chalikian, T.V. Distribution of Conformational States Adopted by DNA from the Promoter Regions of the VEGF and Bcl-2 Oncogenes. J Phys Chem B 2022, 126, 6654–6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, V.; Verma, A.; Maiti, S.; Chowdhury, S. Thermodynamics of i-tetraplex formation in the nuclease hypersensitive element of human c-myc promoter. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2004, 320, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.G.; Chalikian, T.V. Thermodynamic linkage analysis of pH-induced folding and unfolding transitions of i-motifs. Biophys Chem 2016, 216, 19–22. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301462216301636. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kim, B.G.; Feroze, U.; Macgregor, R.B.J.; Chalikian, T.V. Probing the Ionic Atmosphere and Hydration of the c-MYC i-Motif. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140, 2229–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Neely, R.K. 2-aminopurine as a fluorescent probe of DNA conformation and the DNA–enzyme interface. Q Rev Biophys 2015, 48, 244–279. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/A6142805AADDFF8FE114F2AA9F4C66D3. [CrossRef]

- Jean, J.M.; Hall, K.B. 2-Aminopurine fluorescence quenching and lifetimes: Role of base stacking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001, 98, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, J.M.; Hall, K.B. Stacking−Unstacking Dynamics of Oligodeoxynucleotide Trimers. Biochemistry (N Y) 2004, 43, 10277–10284. [CrossRef]

- Kawai, M.; Lee, M.J.; Evans, K.O.; Nordlund, T.M. Temperature and Base Sequence Dependence of 2-Aminopurine Fluorescence Bands in Single- and Double-Stranded Oligodeoxynucleotides. J Fluoresc 2001, 11, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somsen, O.J.G.; Keukens, L.B.; de Keijzer, M.N.; van Hoek, A.; van Amerongen, H. Structural Heterogeneity in DNA: Temperature Dependence of 2-Aminopurine Fluorescence in Dinucleotides. ChemPhysChem 2005, 6, 1622–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greider, C.W. Telomeres Do D-Loop–T-Loop. Cell 1999, 97, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, T.; Zhang, J.; Ouyang, J.; Leung, W.; Simoneau, A.; Zou, L. TERRA and RAD51AP1 promote alternative lengthening of telomeres through an R- to D-loop switch. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 3985–4000.e4. [CrossRef]

- Berson, J.A. Memory Effects and Stereochemistry in Multiple Carbonium Ion Rearrangements. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 1968, 7, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghigo, G.; Maranzana, A.; Tonachini, G. Memory Effects in Carbocation Rearrangements: Structural and Dynamic Study of the Norborn-2-en-7-ylmethyl-X Solvolysis Case. J Org Chem 2013, 78, 9041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyavkin, S.A.; Lyubchenko, Y.L. The nonequilibrium character of DNA melting: effects of the heating rate on the fine structure of melting curves. Nucleic Acids Res 1984, 12, 4339–4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W., H.V., Robert; Avakyan, N.; Sleiman, H.F.; Mittermaier, A.K. Mapping the energy landscapes of supramolecular assembly by thermal hysteresis. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 3152. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ruiz, J.M. Protein kinetic stability. Biophys Chem 2010, 148, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorga, O.L.; Freire, E. Dynamic analysis of differential scanning calorimetry data. Biophys Chem 1987, 27, 87–96. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0301462287800492. [CrossRef]

- Volker, J.; Blake, R.D.; Delcourt, S.G.; Breslauer, K.J. High-resolution calorimetric and optical melting profiles of DNA plasmids: resolving contributions from intrinsic melting domains and specifically designed inserts. Biopolymers 1999, 50, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveille, M.P.; Tran, T.; Dingillo, G.; Cannon, B. Detection of Mg(2+)-dependent, coaxial stacking rearrangements in a bulged three-way DNA junction by single-molecule FRET. Biophys Chem 2019, 245, 25–33.

- Shlyakhtenko, L.S.; Rekesh, D.; Lindsay, S.M.; Kutyavin, I.; Appella, E.; Harrington, R.E.; Lyubchenko, Y.L. Structure of Three-Way DNA Junctions 1. Non-Planar DNA Geometry. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 1994, 11, 1175–1189. [CrossRef]

- Shlyakhtenko, L.S.; Appella, E.; Harrington, R.E.; Kutyavin, I.; Lyubchenko, Y.L. Structure of Three-Way DNA Junctions. 2. Effects of Extra Bases and Mismatches. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 1994, 12, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontis, N.B.; Kwok, W.; Newman, J.S. Stability and structure of three-way DNA junctions containing unpaired nucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res 1991, 19, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilley, D.M.J. Structures of helical junctions in nucleic acids. Quart Rev Biophys 2000, 33, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadden, G.M.; Wilken, S.J.; Magennis, S.W. A single CAA interrupt in a DNA three-way junction containing a CAG repeat hairpin results in parity-dependent trapping. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, gkae644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Morten, M.J.; Magennis, S.W. Conformational and migrational dynamics of slipped-strand DNA three-way junctions containing trinucleotide repeats. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsen, R.C.; Chua, E.Y.D.; Hopkins, J.B.; Chaires, J.B.; Trent, J.O. Structure of a 28.5 kDa duplex-embedded G-quadruplex system resolved to 7.4 Å resolution with cryo-EM. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, 1943–1959. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36715343. [CrossRef]

- Simmel, F.C.; Yurke, B.; Singh, H.R. Principles and Applications of Nucleic Acid Strand Displacement Reactions. Chem Rev 2019, 119, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hellmer, H.; Simmel, F.C. Genetic switches based on nucleic acid strand displacement. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2022, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, N.; Ouldridge, T.E.; Šulc, P.; Schaeffer, J.M.; Yurke, B.; Louis, A.A.; Doye, J.P.K.; Winfree, E. On the biophysics and kinetics of toehold-mediated DNA strand displacement. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, 10641–10658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, W.; Hua, W.; Liang, H. Catalytic-assembly of programmable atom equivalents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNA facilitates escape from metastability in self-assembling systems. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2023-05-dna-metastability-self-assembling.html.

- Sun, Y.; Mccorvie, T.J.; Yates, L.A.; Zhang, X. Structural basis of homologous recombination. Cell Mol Life Sci 2019, 77, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaska, L.; Nosek, J.; Kar, A.; Willcox, S.; Griffith, J.D. A New View of the T-Loop Junction: Implications for Self-Primed Telomere Extension, Expansion of Disease-Related Nucleotide Repeat Blocks, and Telomere Evolution. Frontiers in Genetics 2019, 10. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2019.00792.

- Wetmur, J.G. Hybridization and renaturation kinetics of nucleic acids. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng 1976, 5, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouldridge, T.E.; Šulc, P.; Romano, F.; Doye, J.P.K.; Louis, A.A. DNA hybridization kinetics: zippering, internal displacement and sequence dependence. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, 8886–8895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porschke, D.; Eigen, M. Co-operative non-enzymic base recognition. 3. Kinetics of the helix-coil transition of the oligoribouridylic--oligoriboadenylic acid system and of oligoriboadenylic acid alone at acidic pH. J Mol Biol 1971, 62, 361–381. [CrossRef]

- Lilley, D.M.J. Structures of helical junctions in nucleic acids. Q Rev Biophys 2000, 33, 109–159. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/6F6C39B8D3D4F6CF1C10090C0DA311C1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garabet, A.; Liu, L.; Chalikian, T.V. Heat capacity changes associated with G-quadruplex unfolding. J Chem Phys 2023, 159, 055101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalikian, T.V.; Volker, J.; Plum, G.E.; Breslauer, K.J. A more unified picture for the thermodynamics of nucleic acid duplex melting: a characterization by calorimetric and volumetric techniques. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1999, 96, 7853–7858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, J.; Plum, G.E.; Breslauer, K.J. Heat Capacity Changes (ΔCp) for Interconversions between Differentially-Ordered DNA States within Physiological Temperature Domains: Implications for Biological Regulatory Switches. J Phys Chem B 2020, 124, 5614–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelesarov, I.; Crane-Robinson, C.; Privalov, P.L. The energetics of HMG box interactions with DNA: thermodynamic description of the target DNA duplexes. J Mol Biol 1999, 294, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzina, I.; Bloomfield, V.A. Heat capacity effects on the melting of DNA. 2. Analysis of nearest-neighbor base pair effects. Biophys J 1999, 77, 3252–3255.

- Rouzina, I.; Bloomfield, V.A. Heat capacity effects on the melting of DNA. 1. General aspects. Biophys J 1999, 77, 3242–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, D.A.; Jia, B.; Nesbitt, D.J. Measuring Excess Heat Capacities of Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) Folding at the Single-Molecule Level. J Phys Chem B 2021, 125, 9719–9726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Chen, J.; Ju, H.; Zhou, J.; Mergny, J. Drivers of i-DNA Formation in a Variety of Environments Revealed by Four-Dimensional UV Melting and Annealing. J Am Chem Soc 2021, 143, 7792–7807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Školáková, P.; Gajarský, M.; Palacký, J.; Šubert, D.; Renčiuk, D.; Trantírek, L.; Mergny, J.; Vorlíčková, M. DNA i-motif formation at neutral pH is driven by kinetic partitioning. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 2950–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).