Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

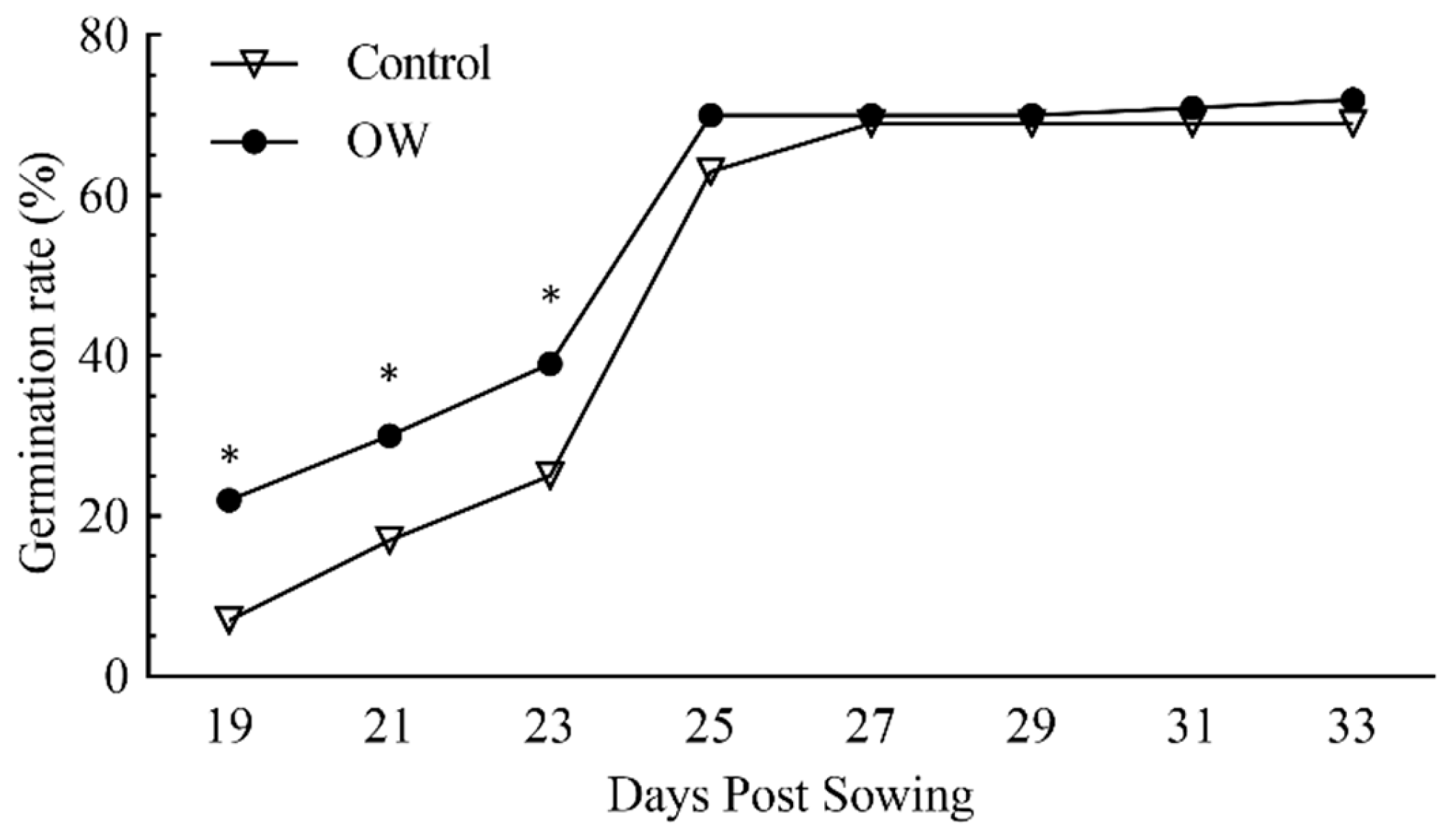

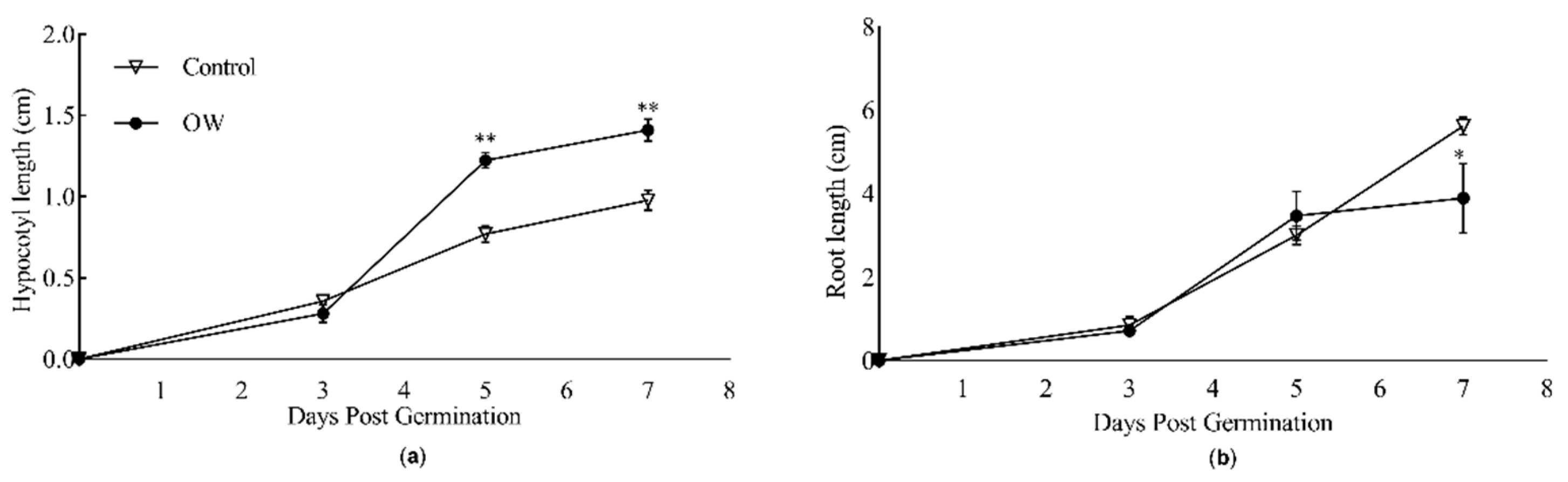

2.1. OW-Treatment Anticipates In Vitro Germination of Diplotaxis Tenuifolia and Promotes Hypocotyl Elongation

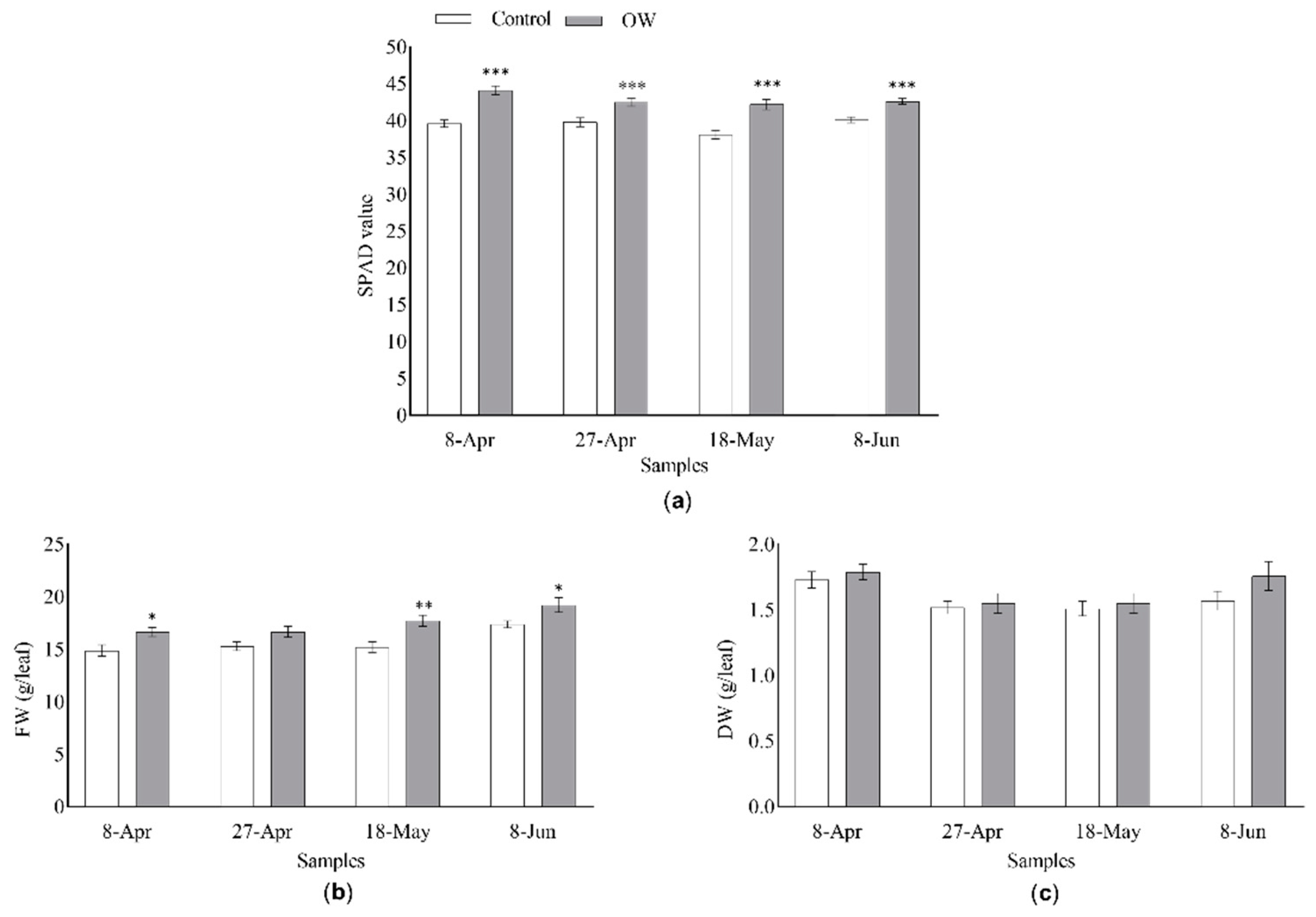

2.2. OW-Treatment Increases the Levels of Light Absorption by Diplotaxis Tenuifolia Leaves and Their Fresh Weight

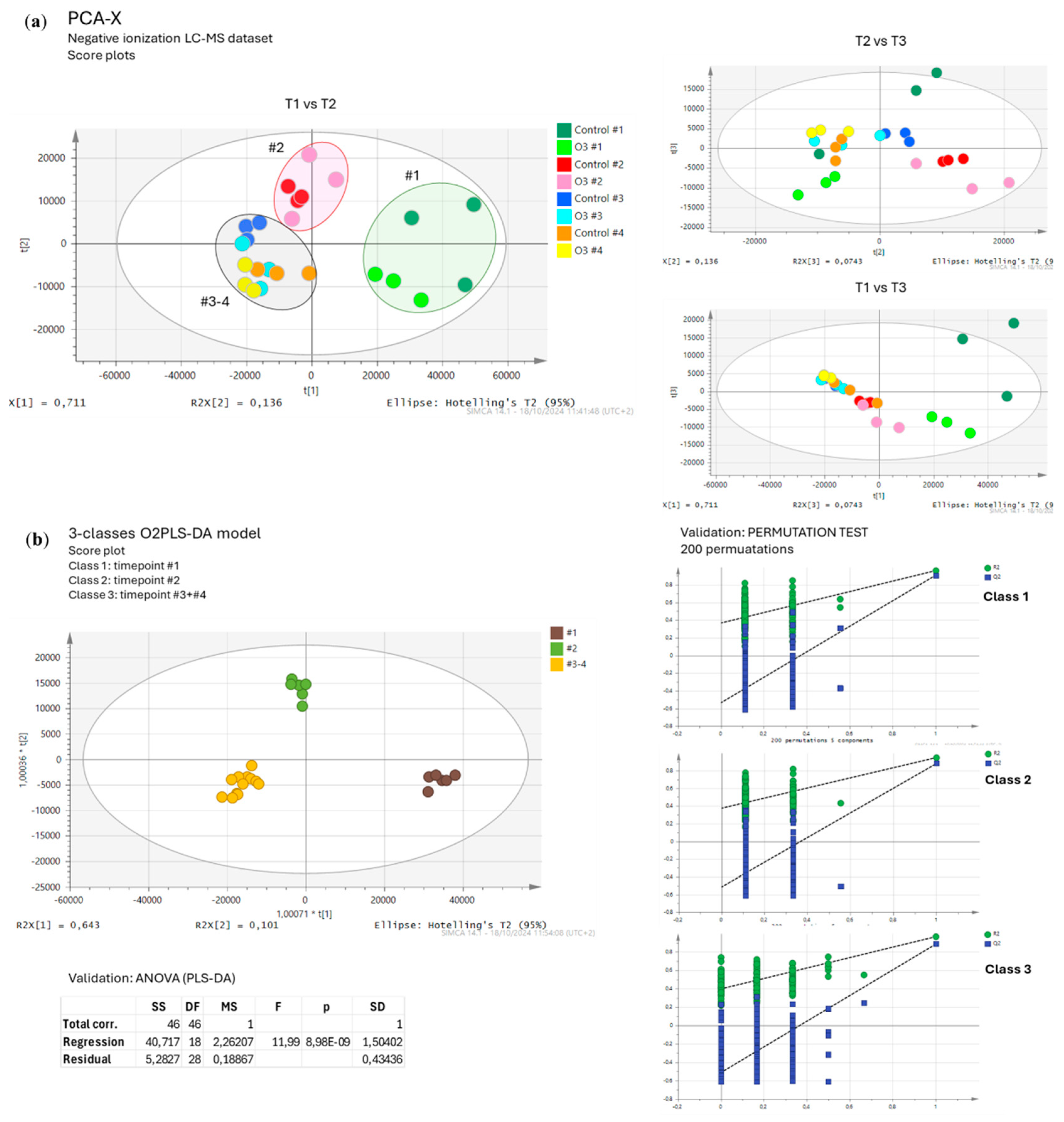

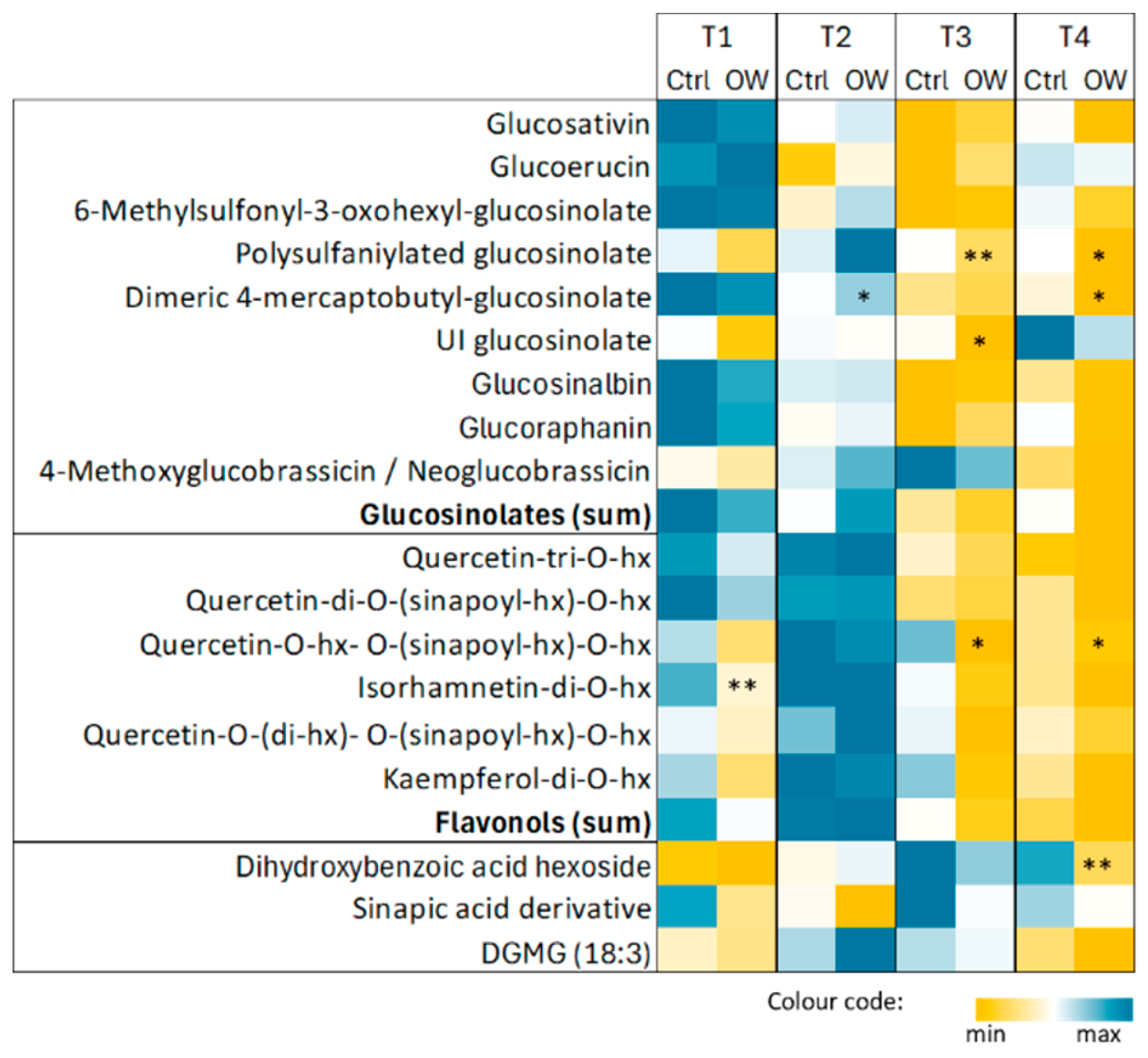

2.3. OW-Treatment Has a Negligible Impact on Diplotaxis Tenuifolia Secondary Metabolome

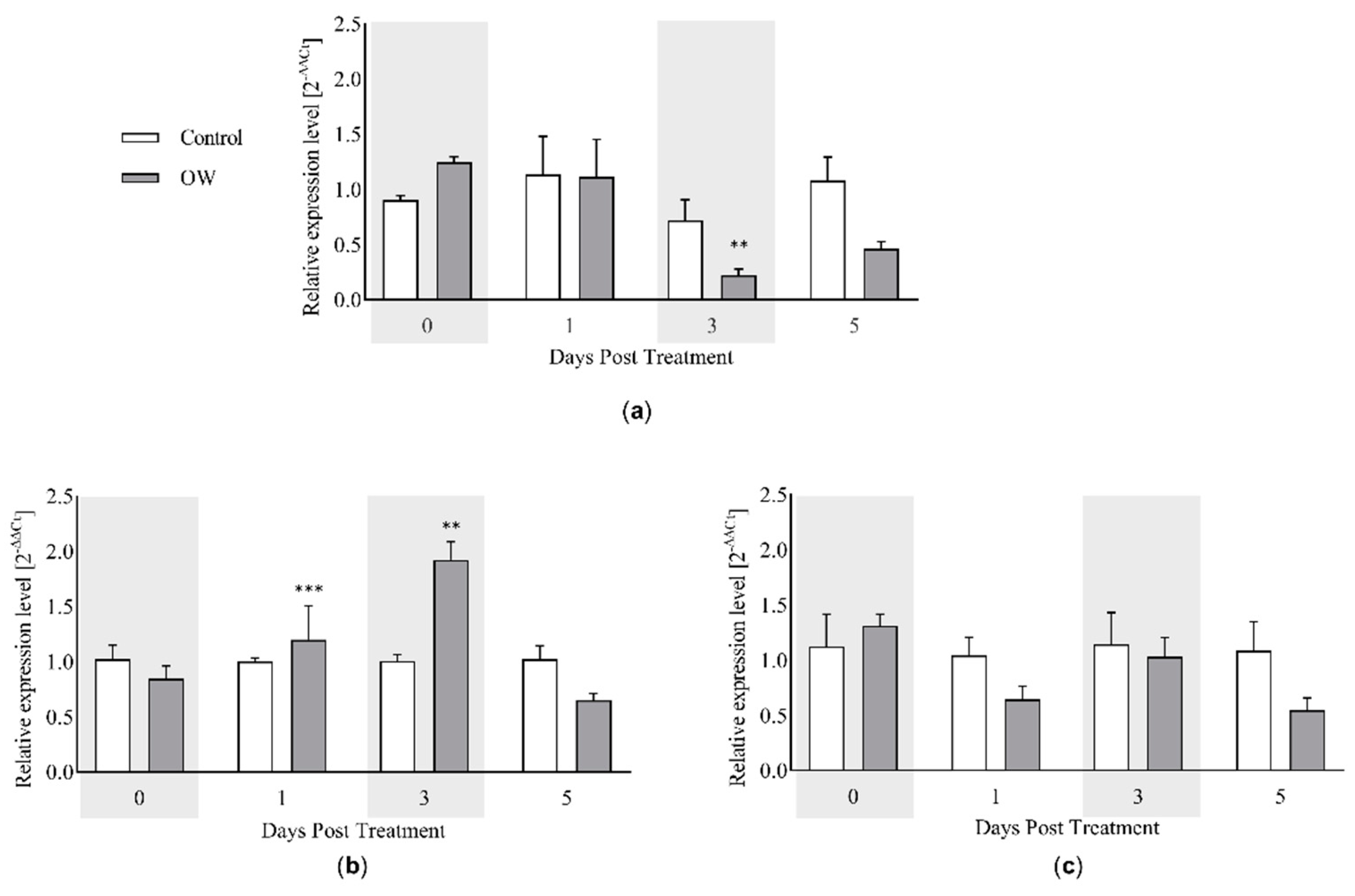

2.4. OW-Treatment Modulates the Expression of Defense Marker Genes in Diplotaxis Tenuifolia Plants in the Field

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

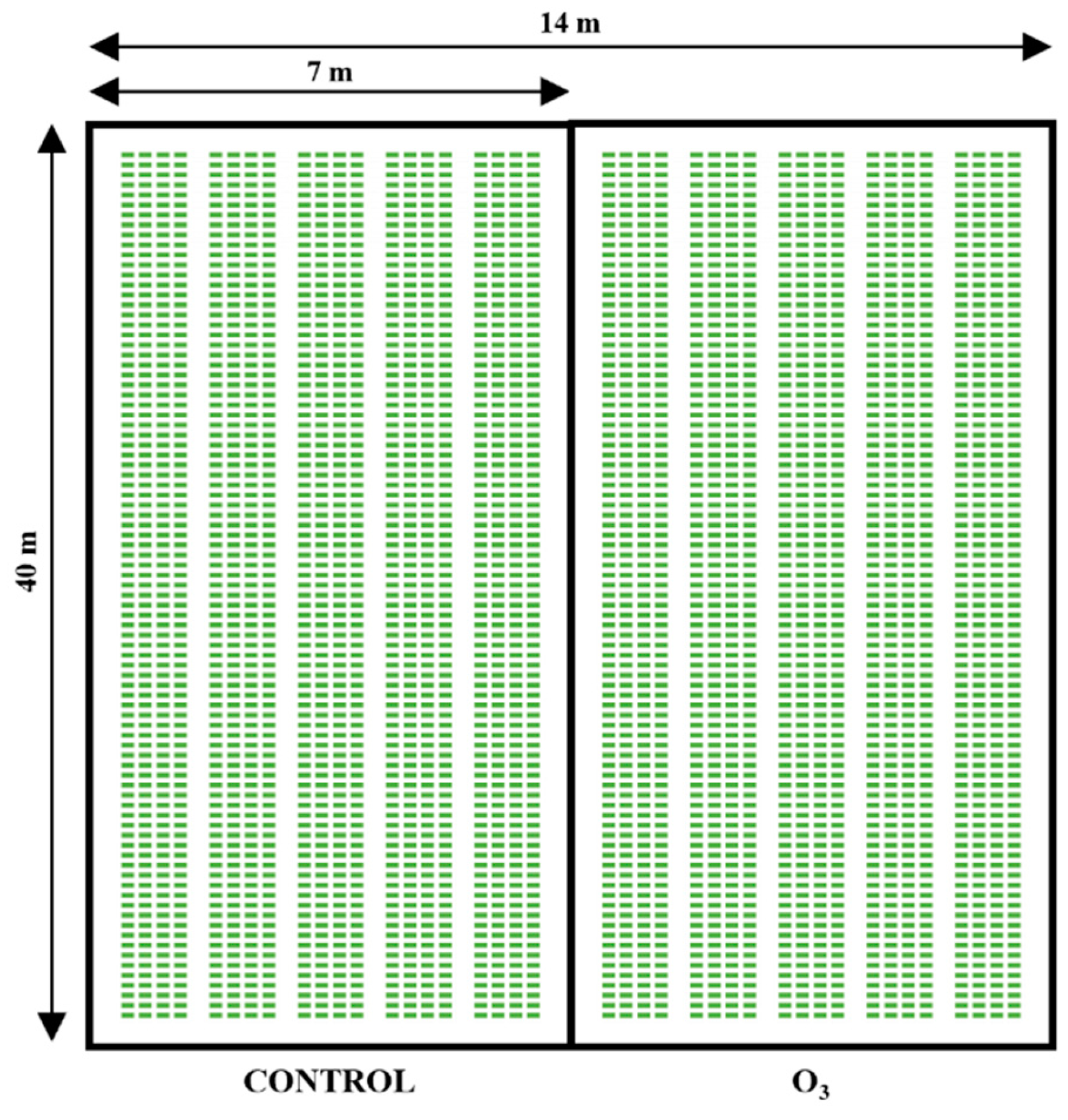

4.1. Plant Material and Experimental Design

4.2. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

4.3. RNA Extraction and Real Time RT-qPCR

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Rt (min). | Class | Putative identification |

Formula | ESI- ion | m/z detected | Fragments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.56 | Glucosinolates | Glucosinalbin | C14H19NO10S2 | [M-H+]- | 424.0369 | 96.9591;95.9538; 259.0161 | HMDB |

| 3.02 | Glucosinolates | Glucoraphanin | C12H23NO10S3 | [M-H+]- | 436.0401 | 372.0444;178.0189; 96.9591; 95.9518; 79.9556 | MassBank |

| 3.12 | Glucosinolates | 6-Methylsulfonyl-3-oxohexyl-glucosinolate | C14H25NO12S3 | [M-H+]- | 494.0458 | 414.0907; 218.0490; 96.9591; 95.9518; 252.0366; 298.0086 | [46] |

| 3.47 | Benzoic acids | Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside | C13H16O9 | [M-H+]- | 315.0711 | 152.0117; 108.0214; 153.0178; 109.0279 | MassBank |

| 3.55 | Glucosinolates | Glucosativin | C11H21NO9S3 | [M-H+]- | 406.0298 | 164.0212; 259.0128; 241.0036; 96.9591; 274.9894 | [47] |

| 4.19 | Glucosinolates | Glucoerucin | C12H23NO9S3 | [M-H+]- | 420.0453 | 96.9591; 959.9518; 259.0128; 241.0036; | [47] |

| 4.66 | Glucosinolates | Dimeric 4-mercaptobutyl-glucosinolate | C22H40O18N2S6 | [M-2H+]2- | 405.0211 | 811.0568; 96.9591; 95.9518 | [48] |

| 5.12 | Flavonols | Quercetin-tri-O-hexoside | C33H40O22 | [M+FA-H+]- | 833.1993 | 787.1932; 625.1457; 463.0889; 301.0341; 300.0263 | manual identification |

| 5.20 | Phenylpropanoids | Sinapic acid derivative | - | - | 385.1128 | 205.0515; 190.0273; 175.0056; 223.0620; | manual identification |

| 5.40 | Flavonols | Quercetin-O-(di-hexoside)- O-(sinapoyl-hexoside)-O-hexoside | C50H60O31 | [M-H+]- | 1155.3061 | 993.2659; 831.2114; 669.1579; 625.1457; 463.0889; 301.0377; 300.0263 | [49] |

| 5.43 | Glucosinolates | 4-Methoxyglucobrassicin/Neoglucobrassicin | C17H22N2O10S2 | [M-H+]- | 477.0628 | 96.9611; 95.9518; 259.0095 | [50] |

| 5.72 | Flavonols | Kaempferol-di-O-hexoside | C27H30O16 | [M-H+]- | 609.1459 | 283.0244; 284.0309; 255.0320; 446.0857; 285.0426; 447.0893 | manual identification |

| 5.86 | Flavonols | Isorhamnetin-di-O-hexoside | C33H40O22 | [M-H+]- | 639.1563 | 313.0352; 314.0429; 476.0991; 477.1046 | MassBank |

| 6.25 | Flavonols | Quercetin-O-hexoside-O-(sinapoyl-hexoside)-O-hexoside | C33H40O22 | [M-H+]- | 993.2513 | 831.2114; 669.1579; 625.1457; 463.0889; 301.0377; 300.0263 | manual identification |

| 6.76 | Glucosinolates | UI glucosinolate | - | - | 321.1003 | 96.9591; 292.8121; 276.8391 | |

| 7.07 | Flavonols | Quercetin-di-O-(sinapoyl-hexoside)-O-hexoside | C55H60O30 | [M-H+]- | 1199.3098 | 1037.2572; 669.1473; 301.0377; 463.0889; 831.2055; | manual identification |

| 10.24 | Glucosinolates | Polysulfaniylated glucosinolate | C16H28N2O9S5 | [M-H+]- | 551.0320 | 96.9611; 95.9518; 259.0095; 241.973; 274.989 | [51] |

| 13.12 | Lipids | DGMG (18:3) | C33H56O14 | [M+FA-H+]- | 721.3651 | 675.3624; 397.1351; 415.1452; 277.2173 | [52] |

References

- H. Karaca and Y. S. Velioglu, “Ozone applications in fruit and vegetable processing,” Food Rev. Int., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 91–106, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Shezi, L. Samukelo Magwaza, A. Mditshwa, and S. Zeray Tesfay, “Changes in biochemistry of fresh produce in response to ozone postharvest treatment,” Sci. Hortic., vol. 269, p. 109397, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Zheng, C. Liu, and W. Song, “Effect of Ozonated Nutrient Solution on the Growth and Root Antioxidant Capacity of Substrate and Hydroponically Cultivated Lettuce ( lactuca Sativa ),” Ozone Sci. Eng., vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 286–292, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Üner Öztürk and M. A. Koyuncu, “Effects of ozone and salicylic acid on post-harvest quality of parsley during storage,” Biol. Agric. Hortic., vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 183–196, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Miller, C. L. M. Silva, and T. R. S. Brandão, “A Review on Ozone-Based Treatments for Fruit and Vegetables Preservation,” Food Eng. Rev., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 77–106, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J.-G. Kim, A. E. Yousef, and S. Dave, “Application of Ozone for Enhancing the Microbiological Safety and Quality of Foods: A Review,” 1999. [CrossRef]

- F. Kobayashi, H. Ikeura, S. Ohsato, T. Goto, and M. Tamaki, “Disinfection using ozone microbubbles to inactivate Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melonis and Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum,” Crop Prot., vol. 30, no. 11, pp. 1514–1518, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Najarian, A. Mohammadi-Ghehsareh, J. Fallahzade, and E. Peykanpour, “Responses of cucumber (Cucumissativus L.) to ozonated water under varying drought stress intensities,” J. Plant Nutr., vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Khadre, A. E. Yousef, and J. G. Kim, “Microbiological aspects of ozone applications in food: A review,” J. Food Sci., vol. 66, no. 9, pp. 1242–1252, 2001. [CrossRef]

- A. Brodowska, A. Nowak, A. Kondratiuk-Janyska, M. Piątkowski, and K. Śmigielski, “Modelling the Ozone-Based Treatments for Inactivation of Microorganisms,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 14, no. 10, p. 1196, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Pagès, D. Kleiber, and F. Violleau, “Ozonation of three different fungal conidia associated with apple disease: Importance of spore surface and membrane phospholipid oxidation,” Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 8, no. 10, pp. 5292–5297, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo, Z. Wang, Y. Li, and Q. Wang, “Effect of Different Concentrations of Ozone on in Vitro Plant Pathogens Development, Tomato Yield and Quality, Photosynthetic Activity and Enzymatic Activities,” Ozone Sci. Eng., vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 531–540, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Piechowiak and M. Balawejder, “Impact of ozonation process on the level of selected oxidative stress markers in raspberries stored at room temperature,” Food Chem., vol. 298, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Sachadyn-Król, M. Materska, and B. Chilczuk, “Ozonation of hot red pepper fruits increases their antioxidant activity and changes some antioxidant contents,” Antioxidants, vol. 8, no. 9, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Martínez-Sánchez and E. Aguayo, “Effects of ozonated water irrigation on the quality of grafted watermelon seedlings,” Sci. Hortic., vol. 261, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Onopiuk, A. Półtorak, M. Moczkowska, A. Szpicer, and A. Wierzbicka, “The impact of ozone on health-promoting, microbiological, and colour properties of Rubus ideaus raspberries,” CyTA - J. Food, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 563–573, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Sharaf-Eldin et al., “Influence of Seed Soaking and Foliar Application Using Ozonated Water on Two Sweet Pepper Hybrids under Cold Stress,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 20, p. 13453, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Sachadyn-Król and S. Agriopoulou, “Ozonation as a method of abiotic elicitation improving the health-promoting properties of plant products-A review,” Molecules, vol. 25, no. 10, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Vainonen and J. Kangasjärvi, “Plant signalling in acute ozone exposure,” Plant Cell Environ., vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 240–252, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Flores, V. Hernández, J. Fenoll, and P. Hellín, “Pre-harvest application of ozonated water on broccoli crops: Effect on head quality,” J. Food Compos. Anal., vol. 83, p. 103260, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Campayo, K. S. de la Hoz, M. M. García-Martínez, M. R. Salinas, and G. L. Alonso, “Spraying ozonated water on bobal grapevines: Effect on wine quality,” Biomolecules, vol. 10, no. 2, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. M. García-Martínez, A. Campayo, N. Moratalla-López, K. S. de la Hoz, G. L. Alonso, and M. R. Salinas, “Ozonated water applied in grapevines is a new agronomic practice that affects the chemical quality of wines,” Eur. Food Res. Technol., vol. 247, no. 8, pp. 1869–1882, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Campayo et al., “The application of ozonated water rearranges the Vitis vinifera L. leaf and berry transcriptomes eliciting defence and antioxidant responses,” Sci. Rep., vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Modesti et al., “Effects of treatments with ozonated water in the vineyard (cv Vermentino) on microbial population and fruit quality parameters,” BIO Web Conf., vol. 13, p. 04011, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Thakur, S. Bhattacharya, P. K. Khosla, and S. Puri, “Improving production of plant secondary metabolites through biotic and abiotic elicitation,” J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants, vol. 12, pp. 1–12, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Martínez-Sánchez and E. Aguayo, “Effect of irrigation with ozonated water on the quality of capsicum seedlings grown in the nursery,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 221, pp. 547–555, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Caarls, C. M. J. Pieterse, and S. C. M. Van Wees, “How salicylic acid takes transcriptional control over jasmonic acid signaling,” Front. Plant Sci., vol. 6, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Bussotti et al., “Ozone stress in woody plants assessed with chlorophyll a fluorescence. A critical reassessment of existing data,” Environ. Exp. Bot., vol. 73, pp. 19–30, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Vitha, L. Zhao, and F. D. Sack, “Interaction of Root Gravitropism and Phototropism in Arabidopsis Wild-Type and Starchless Mutants,” Plant Physiol., vol. 122, no. 2, pp. 453–462, Feb. 2000. [CrossRef]

- H. Labair et al., “Investigating the synergistic impact of ozonated water irrigation and organic fertilization on tomato growth,” Emir. J. Food Agric., vol. 36, pp. 1–9, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. H. Pinzón-Sandoval, P. J. Almanza-Merchán, G. E. Cely-Reyes, P. A. Serrano-Cely, and G. A. Ayala-Martínez, “Correlation between SPAD and chlorophylls a, b and total in leaves from Vaccinium corymbosum L. cv. Biloxi, Legacy and Victoria in the high tropics,” Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Hortícolas, vol. 16, no. 2, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.-P. Xu, Y.-C. Yu, T. Zhang, Q. Ma, and H.-B. Yang, “Effects of ozone water irrigation and spraying on physiological characteristics and gene expression of tomato seedlings,” Hortic. Res., vol. 8, no. 1, p. 180, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. J. J. Clarkson, E. E. O’Byrne, S. D. Rothwell, and G. Taylor, “Identifying traits to improve postharvest processability in baby leaf salad,” Postharvest Biol. Technol., vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 287–298, Dec. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Prigigallo et al., “Ozone treatments activate defence responses against Meloidogyne incognita and Tomato spotted wilt virus in tomato,” Pest Manag. Sci., vol. 75, no. 8, pp. 2251–2263, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X.-Z. Yu, Y.-P. Chu, H. Zhang, Y.-J. Lin, and P. Tian, “Jasmonic acid and hydrogen sulfide modulate transcriptional and enzymatic changes of plasma membrane NADPH oxidases (NOXs) and decrease oxidative damage in Oryza sativa L. during thiocyanate exposure,” Ecotoxicology, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 1511–1520, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Dai, G. Jia, and C. Shan, “Jasmonic acid-induced hydrogen peroxide activates MEK1/2 in upregulating the redox states of ascorbate and glutathione in wheat leaves,” Acta Physiol. Plant., vol. 37, no. 10, p. 200, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Yu. V. Karpets, Yu. E. Kolupaev, A. A. Lugovaya, and A. I. Oboznyi, “Effect of jasmonic acid on the pro-/antioxidant system of wheat coleoptiles as related to hyperthermia tolerance,” Russ. J. Plant Physiol., vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 339–346, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, F. Zhang, M. Melotto, J. Yao, and S. Y. He, “Jasmonate signaling and manipulation by pathogens and insects,” J. Exp. Bot., p. erw478, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Sangiorgio, F. Spinelli, and E. Vandelle, “The unseen effect of pesticides: The impact on phytobiota structure and functions,” Front. Agron., vol. 4, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Bell, S. Lignou, and C. Wagstaff, “High Glucosinolate Content in Rocket Leaves (Diplotaxis tenuifolia and Eruca sativa) after Multiple Harvests Is Associated with Increased Bitterness, Pungency, and Reduced Consumer Liking,” Foods, vol. 9, no. 12, p. 1799, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Colunje, P. Garcia-Caparros, J. F. Moreira, and M. T. Lao, “Effect of ozonated fertigation in pepper cultivation under greenhouse conditions,” Agronomy, vol. 11, no. 3, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Konica Minolta, “Chlorophyllmeter Spad-502Plus - Instruction manual.” Konica Minolta sensing, Inc., 2009.

- T. Fisher Scientific, “Procedural guidelines.” [Online]. Available: https://www.thermofisher.com/trizolfaqs.

- L. Technologies Corporation, “TURBO TM DNase,” 2012. [Online]. Available: www.lifetechnologies.com/termsandconditions.

- M. Cavaiuolo, G. Cocetta, N. D. Spadafora, C. T. Muller, H. J. Rogers, and A. Ferrante, “Gene expression analysis of rocket salad under pre-harvest and postharvest stresses: A transcriptomic resource for Diplotaxis tenuifolia,” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 5, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. R. I. Cataldi, F. Lelario, D. Orlando, and S. A. Bufo, “Collision-Induced Dissociation of the A + 2 Isotope Ion Facilitates Glucosinolates Structure Elucidation by Electrospray Ionization-Tandem Mass Spectrometry with a Linear Quadrupole Ion Trap,” Anal. Chem., vol. 82, no. 13, pp. 5686–5696, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Bell, E. Kitsopanou, O. O. Oloyede, and S. Lignou, “Important Odorants of Four Brassicaceae Species, and Discrepancies between Glucosinolate Profiles and Observed Hydrolysis Products,” Foods, vol. 10, no. 5, p. 1055, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. N. Bennett, F. A. Mellon, N. P. Botting, J. Eagles, E. A. S. Rosa, and G. Williamson, “Identification of the major glucosinolate (4-mercaptobutyl glucosinolate) in leaves of Eruca sativa L. (salad rocket),” Phytochemistry, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 25–30, Sep. 2002. [CrossRef]

- A. bMartínez-Sánchez, R. Llorach, M. I. Gil, and F. Ferreres, “Identification of New Flavonoid Glycosides and Flavonoid Profiles To Characterize Rocket Leafy Salads ( Eruca vesicaria and Diplotaxis tenuifolia ),” J. Agric. Food Chem., vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 1356–1363, Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- B. Zhou, W. Huang, X. Feng, Q. Liu, S. A. Ibrahim, and Y. Liu, “Identification and quantification of intact glucosinolates at different vegetative growth periods in Chinese cabbage cultivars by UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS,” Food Chem., vol. 393, p. 133414, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Dernovics, A. Molnár, and G. Szalai, “UV-B-radiation induced di- and polysulfide derivatives of 4-mercaptobutyl glucosinolate from Eruca sativa,” J. Food Compos. Anal., vol. 122, p. 105485, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Masullo, A. Cerulli, C. Pizza, and S. Piacente, “Pouteria lucuma Pulp and Skin: In Depth Chemical Profile and Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 17, p. 5236, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).