2.1. Autonomic Nervous System

Auber et al., [

4], when comparing indexes of heart rate variability between aerobically-trained athletes and non-athletes, matched by age (18 to 34 years old), demonstrated that young adult athletes presented higher values of parasympathetic autonomic nervous activity in all the analyzed indicators (Mean NN = normal-to-normal interval; pNN50 = percentage of successive interval differences greater than 50ms; rMSSD = square root of the mean squared successive differences between adjacent RR intervals; SDNN = standard deviation of the NN interval) [

4].

Regarding elderly athletes and a sedentary population of the same age, Jensen-Urstad et al., [

5], when analyzing the following parameters: Low frequency (LF) and High frequency (HF) for 24 hours, with LF being a predominantly indicator of sympathetic activity, however with some participation of parasympathetic nerve activity, and HF exclusively of vagal activity, demonstrated that elderly athletes did not present significant differences in both markers. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that, visually, athletes presented lower values of LF and higher values of HF than their control peers. Thus, pointing out, that aerobically-trained athletes seem to have better autonomic nervous health than their control peers [

5].

In addition, in a classic and elegant experiment [

6], a simple model to characterize sympathetic and parasympathetic effects on heart rate (R) was tested during rest in 10 nonathletes and 8 world-class rowers, all male. The model states that R = mnR0, where R0 is the intrinsic cardiac rate, and m and n depend only on sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, respectively. The multipliers, m, and n were determined by dual pharmacological blockade in two sessions under similar conditions, but in one session propranolol and the other atropine were given first. In athletes the control heart rate [55± 3.3 bpm] and R0 (81 ± 8.3 bpm) were lower than in non-athletes (62 ± 6.0; p<0.01 and 102 ± 11; p< 0.001, respectively). The sympathetic multiplier, m, was similar (1.18 ± 0.06 vs. 1.20 ± 0.05; p>0.4) in the two groups, but n, the parasympathetic multiplier, was higher (p<0.01) in the athletes (0.57 ± 0.03) than nonathletes (0.51 ± 0.05).

Adding information to this body of evidence, Biswas (2020), when comparing resting heart rate, Standard deviation of all NN intervals (SDNN), Root mean squared sum of successive NN intervals (rMSSD), and the percentage of the difference between adjacent NN intervals differing more than 50 milliseconds (pNN50%), all these indicators of parasympathetic nerve activity, among cricket athletes (n=15), athletes of different modalities (n=14) and non-athletes (n=11), showed that both groups of athletes had only lower resting heart rate, with no difference in HRV indicators. It is worth mentioning that the groups of athletes presented higher values of the indicators of parasympathetic nervous activity, although not significant (p>0.05) when compared to the group of athletes. This may suggest a protective effect of the athlete's lifestyle on autonomic nervous activity. That is, the greater parasympathetic activity in the group of athletes, although not significant, may be clinically relevant [

7].

An elegant protocol [

8], aimed to verify if autonomic heart rate modulation, indicated by HRV, differed during supine rest and head-up tilt (HUT) when sedentary and endurance-trained cyclists were compared. Eleven sedentary young men and 10 trained cyclists were studied. At rest, the athletes had lower heart rates (p<0.05) and higher values in the time domain of HRV compared with controls (SD of normal RR interval, SDNN, medians): 59.1 ms (sedentary) vs. 89.9 ms (cyclists), p< 0.05. During tilt athletes also had higher values in the time domain of HRV compared with controls (SDNN, medians): 55.7 ms (sedentary) vs. 69.7 ms (cyclists), p< 0.05. No differences in power spectral components of HRV at rest or during HUT were detected between groups.

Shin et al., [

9], evaluated the adaptive effects of endurance training on autonomic function using HRV, in which, continuous ECG were recorded from 15 athletes and 15 nonathletes during 10 minutes in sitting position. Autonomic function was assessed by LF power and HF power. The resting heart rate of athletes was significantly lower than that of nonathletes. The HF power, an index of parasympathetic activity, was significantly higher in athletes than in nonathletes. Meanwhile, the LF power showed no significant difference between both groups, although that of athletes was slightly lower than that of non-athletes [

9].

Stang et al., [

10] compared the parasympathetic nervous activity of athletes from different modalities and their non-athlete controls. The parasympathetic activity was measured by pupillometry and HRV at the onset of exercise with the cardiac vagal index calculated in 28 cross-country skiers (10 female/18 male), 29 swimmers (12 female/17male), and 30 healthy nonathlete controls (16 female/14 male) on two different days. The results demonstrated that athletes had a better vagal heart index than non-athletes. In addition, interestingly, swimmers presented a better vagal heart index than ski cross-country athletes [

10].

On the other hand, Molina et al., [

11] compared 12 elite mountain bikers and 11 non-athlete matched controls, the time domain and frequency of HRV were evaluated based on a series of ECG RR intervals of 5 minutes obtained in the supine and standing positions. The authors found that athletes had lower heart rates (50 vs. 63 bpm; p = 0.0004), but no statistical difference was found in HRV between the groups [

11].

With regard to adolescents, Subramanian et al., [

12], when comparing 30 athletes from aerobic sports and 30 non-athletes, aged between 10 and 19 years, showed that athletes had greater baroreflex sensitivity and greater parasympathetic tone (SDNN, rMSSD and HF power) than their non-athlete peers. Furthermore, parasympathetic reactivity was higher in athletes [

12].

Similar results were also found when investigating athletes with spinal cord injury (SCI) [

13]. A recent and elegant study compared 145 evaluated subjects: 36 athletes with traumatic spinal cord injury (41.1 ± 16.8 years), 52 non-athletes with traumatic spinal cord injuries (40.2 ± 14.1 years), and 57 fit individuals (39.4 ± 12.5 years). Cardiac autonomic modulation was assessed through HRV measured in the sitting position at rest and during a virtual reality (VR) gaming activity. Significantly more favorable HRV for athletes with SCI was found when compared to nonathletes with SCI, but no differences between athletes with SCI and able-bodied controls were verified. In addition, athletes and able-bodied controls showed adequate autonomic nervous system adaptation (rest versus physical activity in VR gaming activity).

Regarding master endurance athletes, 10 elderly male endurance athletes, aged 65 ± 2.6 (group A), were compared with 12 male elderly subjects, aged 66 ± 3.7, who practiced moderate exercise (group B), and with a control group (group C) composed of 20 healthy younger male subjects aged 32 ± 2.3 who practiced moderate exercise. ECG holter monitoring and heart rate variability analysis data were collected. The non-spectral index used to analyze heart rate variability (pNN50) were significantly higher in group A athletes (39.7 ± 9.4%) and in group C subjects (39.2 ± 10.2%) than in group B subjects (32.2 ± 11.5%; p < 0.05) [

14].

These results indicate that athlete status, especially in endurance sports, results in enhanced vagal activity, which may contribute in part to resting bradycardia. In this scenario, it is suggested that athletes appear to be less likely to develop systemic arterial hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, obesity, insulin resistance, increased oxidative stress and inflammation, and, therefore, metabolic syndrome. Since the increase of sympathetic nervous activity has been postulated as the cause and consequence of the diseases and conditions previously mentioned [

15].

2.2. Immune Function

With regards to the immune system, an issue that is emerging today, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, Nieman et al. [

16], when analyzing Phytohaemagglutinin induced lymphocyte proliferative response (whole blood adjusted as cpm for each CD3+ or T cell) showed significantly higher results (31% and 36% for optimal and suboptimal concentrations, respectively) in rowers than in controls. In addition, natural killer cell activity was substantially higher (1.6 – fold for total lytic units) in the female rowers than in controls. These results suggest that athletes seem to be more protected against some harmful agents than non-athletes.

However, another study by the same researchers [

17], with the purpose to compare natural killer cell cytotoxic activity and Con A-induced lymphocyte proliferation (T cell function) in athletes versus non-athletes, with measurement of natural killer and T cells to allow a comparison on a "per-cell" adjusted basis, was carried out. Eighteen young male endurance athletes (10 runners and 8 cyclists) with 6.6 ± 0.8 years of competitive experience were compared with 11 nonathletic male adults. Concentrations of circulating leukocyte and lymphocyte subsets, including natural killer and T cells, were not significantly different between groups. Natural killer cell cytotoxic activity and T cell function also did not differ between groups, whether expressed unadjusted or adjusted on a per-cell basis.

Nevertheless, an elegant review study, also conceived and written by the same author [

18], pointed out that, when comparing the immune function of athletes and nonathletes, results revealed that the adaptive immune system is largely unaffected by athletic endeavor. The innate immune system appears to respond differentially to the chronic stress of intense exercise, with natural killer cell activity tending to be enhanced while the neutrophil function is suppressed.

In adolescent athletes, resting immune function and infection incidence was compared between 20 (10 female/10 male) elite teenage tennis athletes and 18 (9 female/9 male) non-athletic, age-matched controls. Natural killer cell counts were 53% higher (p = 0.015) and neutrophil counts were 16% lower (p = 0.030) in the athletes. However, salivary immunoglobulin IgA output, serum/plasma concentration of IL-6, Il-1ra, cortisol, and growth hormone, Phytohaemagglutinin-induced lymphocyte proliferation, and IL-2 production, and the incidence of upper respiratory tract infections during 2.5 months did not differ between groups. These data suggest that despite intensive training by adolescent tennis athletes, immune function and upper respiratory tract infection incidence are normal. The natural killer cell elevation is consistent with previous studies in athletes that show an enhanced recirculation and activity of natural killer cells [

19].

Thus, there is a weak suggestion of a slightly elevated natural killer cell count and cytolytic action in trained individuals [

20]. Levels of secretory immunoglobulins, such as salivary IgA, vary widely between individuals, and, although some early studies indicated that salivary IgA concentrations are lower in endurance athletes compared to sedentary individuals [

21], the majority of more recent studies indicate that s-IgA levels are generally not lower in athletes when compared to non-athletes, except when athletes are engaged in periods of very heavy training [

22].

Thus, the argument for an improvement in the immune system of athletes when compared to non-athletes seems to be shy, although, enough to reverberate in a better state of health than non-athletes. It is reasonable to infer that the immune system of athletes may be more efficient than their non-athlete peers, as high-level athletes are less likely to develop chronic diseases [

23]. It is noteworthy that the immune system seems to play a central role in many processes involving chronic diseases [

24].

2.3. Gut Microbial Diversity

Recently, gut microbial diversity has been the subject of many investigations. For instance, the study by Clarke et al. [

25], compared the diversity of intestinal microbiota between elite athletes and non-athletes, which were divided into three groups: athletes; control with BMI <25 and control with BMI≥ 25 kg∙m-2, matched by age. The authors found that athletes had greater diversity in the gut microbial, in all analyzed indexes (phylogenetic diversity, Shannon index, Simpson, Chao1 and observed species), when compared to the other groups. Greater gut microbial diversity has been associated with less chance of developing diseases [

25].

Barton et al. [

26] investigated metabolic phenotyping and functional metagenomic analysis of the intestinal microbiome of professional international rugby union players (n = 40) and their control peers (n = 46) and associated these variables with lifestyle parameters and clinical measures (e.g., diet habit and serum creatine kinase, respectively). The results indicated that athletes had relative increases in pathways (e.g., amino acid and antibiotic biosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism) and faecal metabolites (e.g., microbial produced short-chain fatty acids acetate, propionate and butyrate) associated with enhanced muscle turnover (fitness) and general health when compared with control group.

Han et al. [

27], studied a team of professional female rowing athletes in China and 306 fecal samples were collected from 19 individuals, which were separated into three cohorts: adult elite athletes, youth elite athletes, and youth non-elite athletes. The differences in gut microbiome among different cohorts were compared, and their associations with dietary factors, physical characteristics, and athletic performance were investigated. The microbial diversities of elite athletes were higher than those of youth non-elite athletes. The taxonomical, functional, and phenotypic compositions of adult elite athletes, youth elite athletes and youth non-elite athletes were significantly different. Additionally, three enterotypes with clear separation were identified in athlete’s fecal samples, with majority of elite athletes stratified into enterotype 3. This enterotype-dependent gut microbiome is strongly associated with athlete performances. These differences in athlete gut microbiota led to the development of a random forest classifier based on taxonomical and functional biomarkers, capable of differentiating elite athletes and non-elite athletes with high accuracy.

Given that there appears to be a clear dichotomization of the intestinal microbiome between adult elite athletes, youth elite athletes and youth non-elite athletes, it is reasonable to infer that these differences may be even more pronounced when compared to non-athlete individuals.

In this scenario, it seems likely that athletes will benefit both in aspects of human health and in sports performance from the fundamental role of microbiomes. Despite there being an evident and clear difference between athletes and non-athletes, regardless of the nature of the sport, whether endurance or neuromuscular, the structure of the athletes' intestinal microbiome seems to be positively influenced. However, to understand the implications of these factors, more in-depth studies are needed to indicate how organisms present in the microbiota respond to physical exercise, inducing improvement in the performance and health of these individuals [

28].

2.4. Bone Mineral Density

Another aspect that athletes seem to have better rates than their non-athlete peers refer to bone health, even in athletes in a state of amenorrhea. An elegant study [

29] compared several bone health indicators among weight-bearing sports athletes with eumenorrheic weight, amenorrheic athletes, and non-athletes and found the following results: cortical perimeter, porosity and trabecular area at the weight-bearing tibia were greater in both groups of athletes than non-athletes, whereas the ratio (%) of cortical to total area was lowest in amenorrheic athletes. Although greater cortical porosity in eumenorrheic athletes, estimated tibial stiffness, and failure load was higher than in non-athletes, this benefit was lost in amenorrheic athletes. At the non-weight-bearing radius, failure load and stiffness were lower in amenorrheic athletes when compared to non-athletes. Subsequently, controlling for lean mass and menarchal age, athletic status accounted for 5–9% of the variability in stiffness and failure load, menarchal age for 8–23%, and lean mass for 12–37% [

30]. These results indicate that athletes, especially those without interruption of menarche, have better bone health indicators than non-athletes.

In another perspective, Herbet et al. [

31], investigated the contribution of genetic variants to bone mineral density and the possible sensitivity of specific genotypes to external stimuli, including mechanical load through training in 103 high-level endurance runners (45 men, 58 women) and 112 (52 men, 60 women) ethnically matched non-athletes. To this end, ten single-nucleotide polymorphisms were identified from previous genome-wide and/or candidate gene association studies that have a functional effect on bone physiology. The aims of this study were to investigate (1) associations between genotype at those ten single-nucleotide polymorphisms and bone phenotypes in high-level endurance runners, and (2) interactions between genotype and athlete status on bone phenotypes.

Female runners with P2RX7 rs3751143 AA genotype had 4% higher total-body bone mineral density and 5% higher leg bone mineral density than AC + CC genotypes. Male runners with WNT16 rs3801387 AA genotype had 14% lower lumbar spine bone mineral density than AA genotype non-athletes, whilst AG + GG genotype runners also had 5% higher leg bone mineral density than AG + GG genotype non-athletes. Thus, highlighting a potential genetic interaction with factors common in endurance runners, such as high levels of mechanical loading.

These results suggest that, with regard to bone health, as was assumed, some sports, especially those involving power and strength, can produce greater benefits than those of an aerobic nature. On the other hand, depending on the genotype, even endurance athletes appear to have better preserved bone health than their non-athlete peers. With regard to master athletes, similar results and showing a difference in bone mineral density associated with the type of physical exercise are pointed out by Piasecki et al., [

32] who studied 38 master sprint runners, 149 master endurance runners and 59 male and female non-athletes (control) to investigate the relationship between participation in regular sprint or endurance running and bone health. For the hip skeleton (14%) and spine, sprinters had a better result in bone mineral density when compared to endurance runners and non-athletes. However, no significant differences were observed in bone mineral density of the hip and spine between non-athletes and endurance runners.

Sagayama et al [

33], when analyzing the bone mineral density of 33 athletes (fighters, judokas and endurance athletes) and 8 non-athletes (control group), through X-ray absorptiometry, observed that athletes classified with higher body weight (judokas and wrestling fighters) also had higher bone mineral density than non-athletes and endurance athletes. However, the difference between judoka and endurance-athletes disappeared when adjusted for body mass. Regarding the prevalence of fractures, in a sample of 5,398 former university students, 2,622 former university athletes and 2,776 non-athletes, aged between 21 and 80 years, authors found that among women aged 60 and older who did not have a fracture by age 40, the rate of any fracture by age 40 or older was 29% for former college athletes, compared with 32% for non-athletes, although the statistic did not show a significant difference.

These results are evidence that sport is important for the bone health of athletes. However, it is possible to observe that there is a need to use high-impact and regular cross-training, especially for endurance athletes, in order to mainly minimize fragility and stress fractures resulting from the impact force performed in a repetitive manner, even if they are a characteristic of the sport [

34].

2.5. Vascular Health

A sophisticated review about vascular health and aging [

35], showed that both young and Master athletes, who were aerobically trained, had better vascular health than young, untrained subjects. When compared to their untrained peers, aerobically trained Master’s athletes demonstrated a more favorable arterial function–structure phenotype, including lower large elastic artery stiffness, enhanced vascular endothelial function, and less arterial wall hypertrophy. Having a favorable arterial function–structure profile may contribute to their lower risk of clinical cardiovascular diseases.

Furthermore, Beteck et al. [

36], reviewed office records of their patients treated for thoracic outlet syndrome from 2009 to 2014 and extracted demographic, historical, procedural and follow-up data. They then contacted these patients to complete a survey to evaluate patient-centered first rib resection and scalenectomy outcomes and compare survey responses from athletes versus non-athletes.

Of the 184 who responded, 97 were athletes (53%) and 87 were non-athletes (47%). Survey results suggested that 87% improved in analgesic use (athletes 93% vs. non-athletes 80%, p=0.013), 77% would undergo first rib resection and scalenectomy on the contralateral side if necessary (athletes 75% vs. non-athletes 79%, p=0.49), 73% had resolution of thoracic outlet syndrome symptoms (athletes 80% vs. non-athletes 65%, p=0.02) and 86% were able to perform activities of daily living without limitations (athletes 95% vs. non-athletes 77%, p=0.0004). Although 24% of respondents needed another procedure unrelated to thoracic outlet syndrome (athletes 27% vs. non-athletes 22%, p=0.6), 89% felt they had made the right decision (athletes 93% vs. non-athletes 80%, p=0.09).

A classic study by Pyörälä et al. [

37] which subjected sixty-one former endurance racing champions or cross-country skiers, aged between 40 and 79 years, and 54 non-athletes, to a thorough evaluation of the cardiovascular system, paired by age, found the following results: Both the athletes mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure were significantly lower than those of the controls; there was no difference in serum cholesterol level or blood hemoglobin concentration between the two groups; coronary heart disease was diagnosed in 17 of 54 controls and in 15 of 61 athletes. Eight control subjects, but only 2 athletes, showed symptoms of coronary heart disease. Twenty-nine of the controls and 38 of the athletes were considered “healthy.”

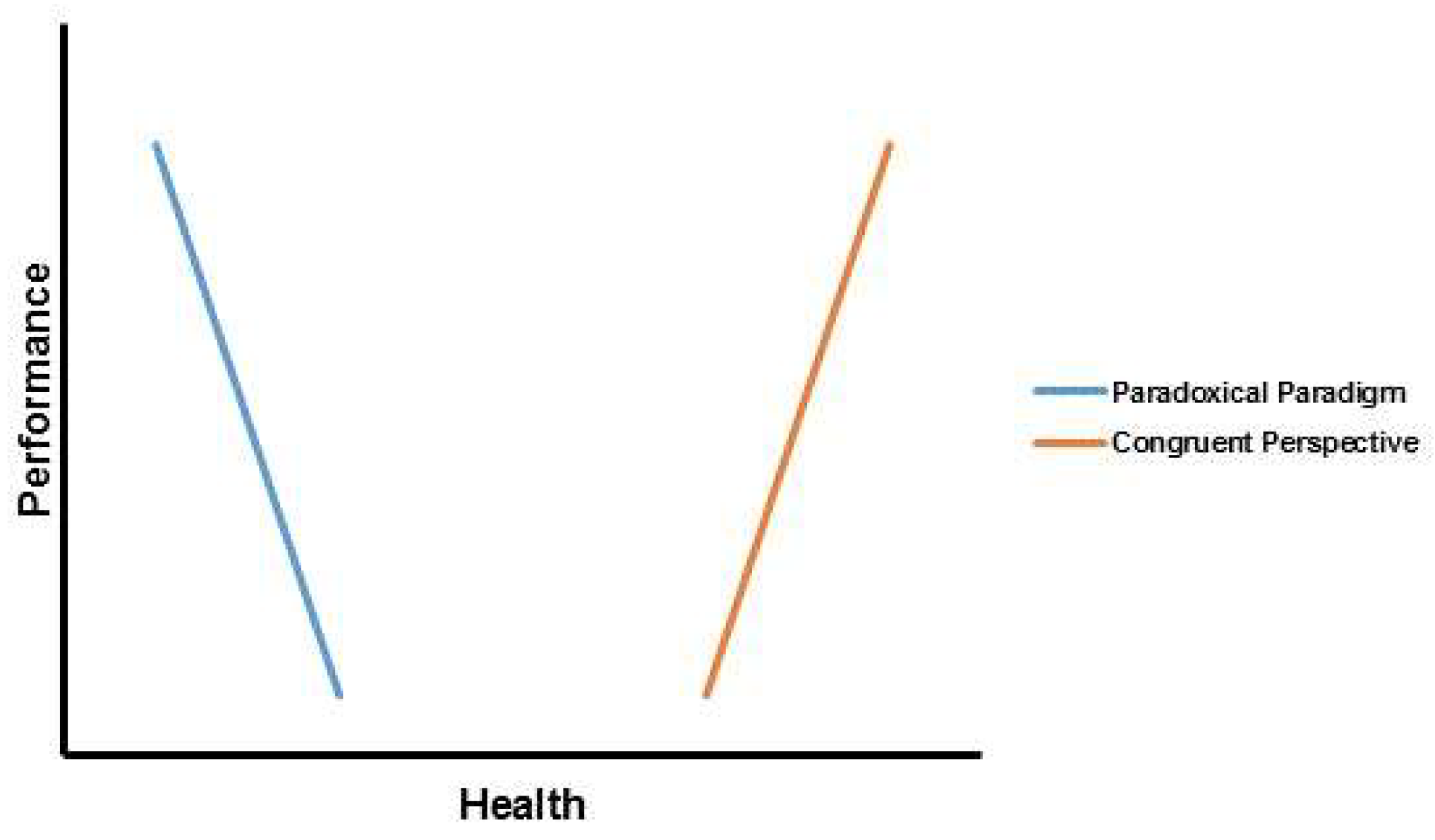

On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that athletes who experience high training loads frequently, being exposed to excess fatigue, overreaching and overtraining, can produce harmful effects on vascular health. As suggested in a recent study, Grandys et al., [

38], investigated the effects of high training stress on endothelial function assessed by flow-mediated dilation and markers of glycocalyx clearance in 15 mid- and long distance and their control pairs (n=15), both groups composed of women, after two months of training by the group of athletes. The results indicated that, after two months of high physical stress training, flow-mediated dilation was reduced (p<0.01) and basal serum concentrations of hyaluronan and syndecan-1 (p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively) increased, which were accompanied by significantly lower baseline serum testosterone and free testosterone (p<0.05) and higher cortisol concentration (p<0.05), than their control peers.

Nevertheless, it is important to mention that states of high physical stress due to training should not occur for long periods and states of overreaching and overtraining must be absolutely avoided, as they can obviously lead to the onset of diseases and, consequently, loss of performance. Furthermore, the literature above overwhelmingly demonstrated that athletes, apparently well monitored, presented better vascular health than non-athletes.

2.6. Breast Cancer and cancer of the reproductive and non-reproductive system

A well-designed study, which followed former university athletes and their non-athlete colleagues for 15 years, matched participants according to the family history of cancer and breast cancer, pregnancy, use of contraceptives, and use of hormone replacement therapy by women aged 50 and over. The results showed that, regarding lifestyle factors, such as exercise, smoking, and diet, the proportion of former athletes who continued to exercise was higher than that of non-athletes. The two groups did not differ in terms of smoking history, that is, if they had ever smoked. More non-athletes reported dietary restrictions and followed a low-fat diet than athletes. Former college athletes had a lower incidence of breast cancer than non-athletes. Breast cancer incidents in 15 years were 64/1000 among athletes and 111/1000 among non-athletes [

39].

In addition, Frisch et al. [

40], investigated 2,622 former college athletes and 2,776 non-athletes, from data on medical and reproductive history, athletic training and diet. The former athletes had a significantly lower risk of cancer of the breast and reproductive system than did the non-athletes. The relative risk, non-athletes/athletes, for cancers of the reproductive system was [2.53 (95%CI: 1.17- 5.47)]. The relative risk for breast cancer was [1.86 (95%CI: 1.00 - 3.47)].

In this same sample, but not the same study, when evaluating the prevalence and relative risk of cancer of the non-reproductive system, in which cancers of the non-reproductive system were divided into two classes: class I, which included cancers of the digestive system, thyroid, bladder, lung and others local and hematopoietic cancers (lymphoma, leukemia, myeloma and Hodgkin's disease) and class II, which included skin cancer and cutaneous melanoma, authors found that former college athletes had a significantly lower prevalence of class I cancers when compared to the non-athletes; the age-adjusted relative risk was [3.34 (95%CI: 1.35, 8.33; p=0.009)]. In contrast, the prevalence rates of malignant melanomas and skin cancers did not differ significantly between the former athletes and nonathletes [

41].

These same researchers [

42] analyzed the lifetime occurrence of breast cancer and reproductive system cancer in the same sample and the results indicated that non-athletes had an increased relative risk of reproductive system cancer [2.53 (95%CI: 1,17 - 5.47). The relative risk for breast cancer was [1.86 (95%CI: 1.00 - 3.47)]. These outcomes point to the importance of the athlete's lifestyle in the protection and treatment against all type of cancer, especially breast cancer.

2.7. Redox Balance and Telomere Length

Regarding the REDOX state and how it reverberates in the length of telomeres, which is known as a biological marker of aging that is associated with age-related diseases, our group recently conducted a study [

43] comparing REDOX balance markers and the telomeres in leukocytes between Master athletes and non-young and middle-aged athletes (paired with Master athletes). The results showed that the Master athletes and the group of young non-athletes had a better REDOX balance, according to the antioxidant/pro-oxidant ratios, when compared to non-athlete middle-age participants. While the middle-aged non-athletes had shorter leukocyte telomere length than the young non-athletes, no difference was observed between Master athletes and young non-athlete participants. This suggests that Master athletes can have similar cellular aging as non-athlete young adults.

Furthermore, master sprint athletes have shown longer telomeres length than non-athletes. Performance was positively associated with telomeres length, and negatively associated with decline in performance. Therefore, longer telomere length is related to a smaller decline in the performance [

44].

Rosa et al. [

45] compared male master sprinters (n = 13), endurance runners (n = 18), untrained young (n = 17) and age-matched controls (n = 12) for the following variables: REDOX balance, cytokine levels and biomarkers responsible for aging. An increased pro-oxidant activity (elevated protein carbonyl; isoprostanes and 8-OHdG) was observed for age-matched controls in comparison to remaining groups. However, master sprinters presented better antioxidant capacity than both age-matched controls and endurance runners, while nitrite+nitrate (NOx) availability was higher for endurance runners and lower for the age-matched controls. Both groups of athletes presented better anti-inflammatory status than age-matched controls (increased IL-10 and lowered IL-6, sIL-6R, sTNF-RI), but worse than untrained young (increased TNF-α, sTNF-RI, and sIL-6R). Telomere length was shorter in age-matched controls, which also had lower levels of irisin and klotho, and elevated FGF-23. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA) levels were higher in age-matched controls and master sprinters, while irisin was lower in endurance runners when compared to master sprinters and untrained young (p < 0.05).

A very interesting systematic review and meta-analysis research was produced by Aguiar et al. [

46], which gathered 11 studies to assess telomere length in master athletes (240) and non-athletic individuals (209) of the same age and also discussed mechanisms that could preserve telomere length in master athletes. Pooled analyses, calculated based on standard mean difference (SMD), revealed that master athletes had longer telomeres than aged-matched non-athletes (SMD=0.89; 95%CI: 0.45−1.33; p<0.001). Master athletes showed lower pro-oxidant damage (SMD=0.59; 95%CI: 0.26−0.91; p<0.001) and higher antioxidant capacity (SMD=-0.46; 95%CI: -0.89−0.03; p=0.04) than age matched non-athletes. In addition, greater telomere length in master athletes was associated with lower oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, and enhanced shelterin protein expression and telomerase activity.

Such findings indicate the importance of the athlete's lifestyle in preserving telomere length, which is inversely associated with aging and, therefore, with chronic diseases and aging.

2.8. Concussion Rehabilitation

Concussion, when associated with sports, may have repercussions on cognitive, physical and emotional problems. Thus, this type of injury results in physical disability that prevents the individual from being able to perform physical exercise in the expected way for their physical conditioning and age. Studies indicate that ventilation can be affected by contusion conditions that increase the levels of carbon dioxide in the arteries, increasing blood flow in the brain which may decrease levels of tolerance to physical exercise, causing impairment in sports performance [

47].

An interesting study that investigated the incidence of concussion among 904 college students, including 502 men and 452 women, of these 448 athletes, showed that the rate of non-sport related concussions (81.0 [95%CI: 73.9-88.7] concussions per 10,000 students in the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 academic years) was higher than the rate of sports-related concussions (51.5 [95% CI: 49.5-57.7] concussions per 10,000 students in the academic years 2016-2017 and 2017-2018). Suggesting that even athletes, apparently more exposed to the event in question, appear to be physically more prepared and, therefore, protected from possible concussion episodes [

48].

Another interesting study that compared the gait speed between athletes and non-athletes after a concussion showed that: 1) athletes who suffered a concussion have higher gait speed than apparently healthy non-athletes and; 2) athletes who suffered concussion have higher gait speed than their non-athlete peers. Thus, it is reasonable to infer that athletes who suffered concussion may have greater preservation of autonomy and, therefore, independence, reverberating in a higher quality of life than their control peers [

49].

Due to the high prevalence of concussion in athletes compared to non-athletes, comparative literature between these groups is still scarce. On the other hand, there seems to be enough evidence to consider that athletes react better to concussion, as well as have a lower risk of recurrence, evidencing the protective effect of the athletic lifestyle on the outcome variable in question.

2.9. Sleep Quality

Demirel et al. [

50], when comparing variables related to sleep quality (copious sleep duration, problem falling asleep in the first 30 minutes, problem keeping late hours, problem falling asleep, early wake up in night or morning, and excessive chilling perception) between athletes and non-athletes, matched by age, demonstrated that athletes have better scores in all variables than non-athletes and, therefore, a better overall sleep quality index.

Likewise, Litwic-Kaminska et al [

51], when investigating a total of 335 healthy university students, using the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire, Perceived Stress Scale, Life Satisfaction Scale and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, among athletes (n=207) and non-athletes (n=128), indicated that student athletes were less stressed (p<0.001), declared greater satisfaction with life (p<0.001) and better sleep quality (p <0.001) compared to non-athletes.

Ungaro et al. [

52], when comparing sleep habits between 34 student-athletes (18 men and 16 women), aged 15.8 ± 0.8 years, and 38 non-athletes (10 men and 28 women), aged 16.3 ± 0.7 years, showed that student-athletes and non-athletes did not differ in total sleep time (440.4 ± 46.4 vs 438.1 ± 41.7 min, p= 0.82) and sleep efficiency (93.6 ± 2.3 vs 92.9 ± 2.3%, p = 0.20). Additionally, 79% of student-athletes and 87% of non-athletes were unable to sleep more than the recommended minimum of 8 hours of total sleep per night. Student-athletes had earlier bedtimes and earlier wake-up times. Although the statistics did not reveal a difference between the groups of athletes and non-athletes and the visual differences were really small, this minimal difference may have some clinical relevance that we are not aware of.

Zhou et al. [

53] compared 372 student athletes and 252 non-athlete students aged between 18 and 22 years old. The results showed that compared to non-athlete students, athlete students performed better in healthy habits (10.01 vs. 8.27) and that, among healthy behaviors, is adequate sleep.

With regard to elite athletes, they are particularly susceptible to sleep inadequacies, characterized by habitually short sleep (<7 hours/night) and poor sleep quality (e.g., sleep fragmentation). Fortunately, much is known about the main risk factors for sleep inadequacy in athletes, allowing for targeted interventions. For example, athletes' sleep is influenced by sport-specific factors (related to training, travel and competition) and non-sport factors (e.g. female gender, stress and anxiety) [

54]. On the other hand, some evidence suggests that athletes have better sleep quality than their non-athlete peers. In other words, even with the sleep limitations highlighted above, athletes seem to have somewhat better sleep than their non-athlete peers.

2.10. Social Connectedness, Self-Esteem, Depression, and Happiness

Regarding social and emotional aspects, such as self-esteem, depression, and social connectedness, a study demonstrated that athletes have significantly higher levels of self-esteem and social connections, as well as significantly lower levels of depression than non-athletes [

55]. Thus, athletes seem to be happier than non-athletes [

56].

Dobersek and Arellano [

57], proposed to examine self-esteem and shyness in populations of student athletes and non-athletes. One hundred and ninety-six undergraduate participants (athletes = 128, non-athletes = 68) from a university in the southeastern US completed a demographic questionnaire, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the Shyness Scale. The results are in line with previous researches demonstrating that athletes scored higher in self-esteem and less shyness when compared to non-athletes. A simple linear regression analysis revealed a significant negative relationship between shyness and self-esteem.

Ghaedi and MohdKosnin [

58] compared the level of depression between 170 athletes and 170 non-athletes, 90 males and 80 females in each athlete and non-athlete group, all undergraduate students at a private university in Esfahan, Iran. The results showed that the prevalence rate of depression among male non-athlete undergraduate students was significantly higher than that among male student athletes.

Concerning the prevalence of depression, an interesting study examined depression among male intercollegiate team sports athletes (n = 66) and male non-athletes (n = 51) enrolled at a public university in the United States [

59]. The results revealed that athletes reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms than non-athletes. In terms of current prevalence rates of depressive symptoms, 29.4% of non-athletes met the criteria for possible depression, compared to only 15.6% of athletes. Therefore, it is suggested that athletic participation in college team sport appears to be related to lower levels of depression [

60].

Similarly, Zhou et al. [

53], compared 372 student athletes and 252 non-athlete students aged between 18 and 22 years old. The results showed that when compared to non-athlete students, athlete students performed better in healthy habits (10.01 vs. 8.27), reported lower proportion of depression (44.6% vs. 54.4%) and higher proportion of good health (77.2% vs. 55.6 %).

Snyder et al. [

61], when comparing health-related quality of life using two different instruments (Medical Outcomes Short Form (SF-36) and the Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument) among 219 athletes and 106 adolescent non-athletes, found that, on the Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument, athletes reported higher scores on the sport and physical function and happiness subscales.

Regarding the comparison between former artistic gymnastics athletes and other gymnastics athletes with non-athletes, former athletes appeared to have a better quality of life, as well as reduced anxiety and depression scores when compared to their control peers, non-athletes. Highlighting the prophylactic effect of the athlete's lifestyle on emotional disorders [

62].

2.11. Quality of life

Snyder et al. [

61], when comparing health-related quality of life using two different instruments (Medical Outcomes Short Form (SF-36) and the Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument) among 219 athletes and 106 adolescent non-athletes, found that, on the SF-36, athletes reported higher scores on the physical function, general health, social functioning, and mental health subscales and the mental composite score and lower scores on the bodily pain subscale than non-athletes. On the Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument, athletes reported higher scores on the sport and physical function and happiness subscales and lower scores on the pain/comfort subscale.

Dehkordi [

63], who compared the general health, mental health and quality of life of women in the city of Ahvaz, divided equally into two groups: athletes (n=50) and non-athletes (n=50), revealed that the average scores for general health, mental health and quality of life were higher in athletes than in non-athletes.

Regarding the elderly population (aged between 60 and 69 years), the quality of life between athletes (n=80) and non-athletes (n=80) was compared and, in all domains analyzed, athletes presented better scores than non-athletes. In other words, the average scores for general health, mental health and quality of life were higher in athletes than in non-athletes.

Concerning the comparison between former artistic gymnastics athletes and (n=39) other gymnastics athletes (n=53) with non-athletes (n=22), former artistic gymnastics athletes (75.08 ± 14.42) and other gymnastics athletes (76.49 ± 15.08) appeared to have a better quality of life when compared to their control peers, non-athletes (69.49 ± 17.54). Highlighting the prophylactic effect of the athlete's lifestyle on quality of life [

62].

With regard to individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI), Bella et al. [

64], compared 16 athletes and 24 non-athletes with SCI in demographic and clinical variables, including pain scores and pain interference in daily life (Brief Inventory of Pain, BPI), severity of neuropathic pain (Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory, NPSI) and Quality of life (Word Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment, WHOQOL-BREF). Non-parametric tests were used to compare the groups and, due to the younger age of the athletes, multiple linear regression analysis were used to adjust the effect of sports practice on the outcome variables when adjusted for age. Quality of life was higher in athletes in the Physical, Psychological, Social Relationships, Self-Assessment and Total Score domains when adjusted for age (p < 0.01). Despite having no significant differences in pain intensity scores (NPSI, p = 0.742 and BPI, p = 0.261), athletes had less pain interference in the domains “Relationship with others”, “I enjoy living” and Total score (p< 0.05). Participation in competitive adapted sports (p = 0.004) and Total Pain Interference (p = 0.043) were significantly associated with quality-of-life scores in multiple linear regression analyses.

In addition to all this, Houston et al. [

65] carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis on the topic. The authors stated that all five studies included in the review that compared health-related quality of life in athletes and non-athletes demonstrated positive effect sizes, indicating that athletes reported better health-related quality of life on generic instruments.