Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

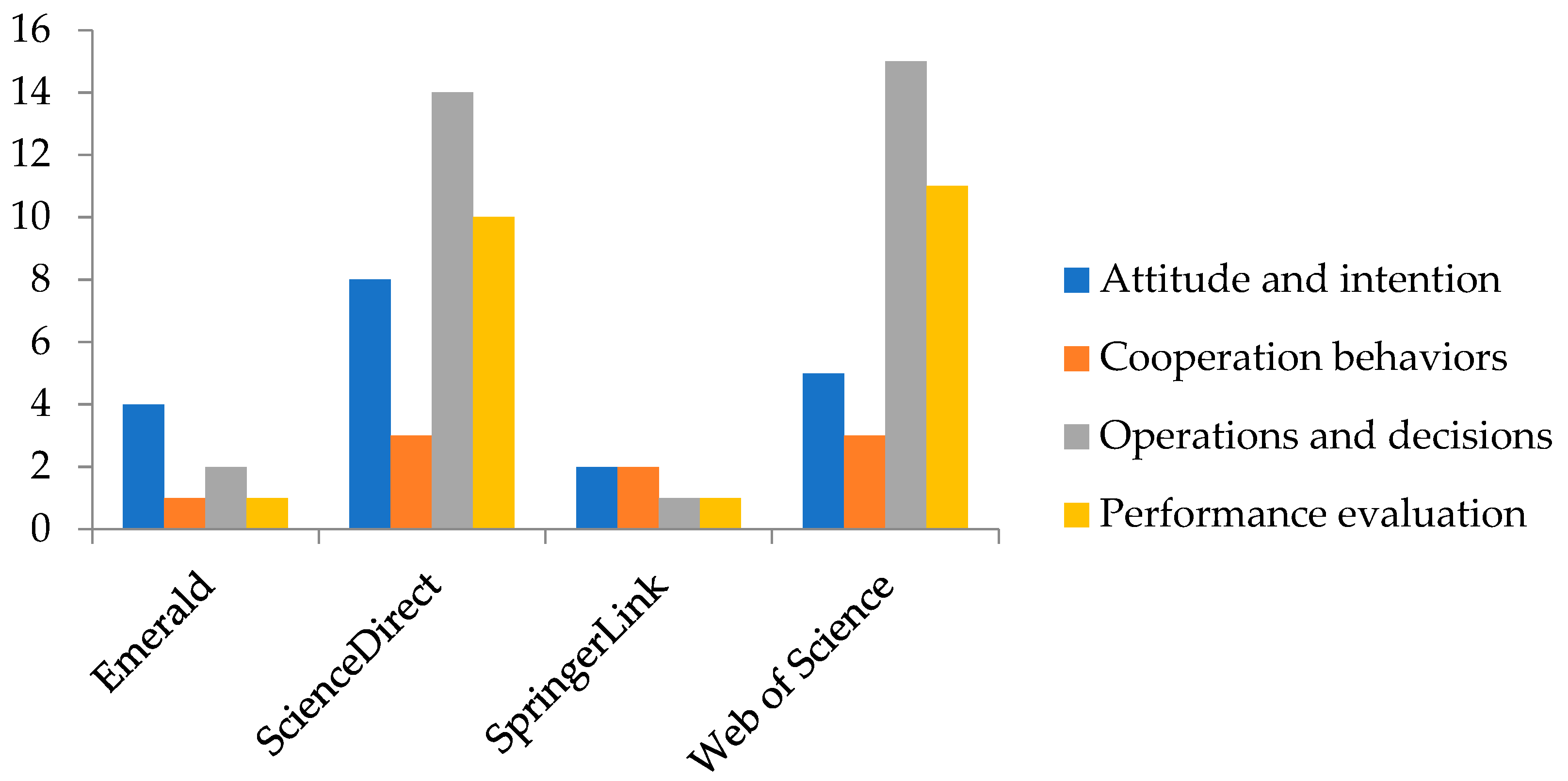

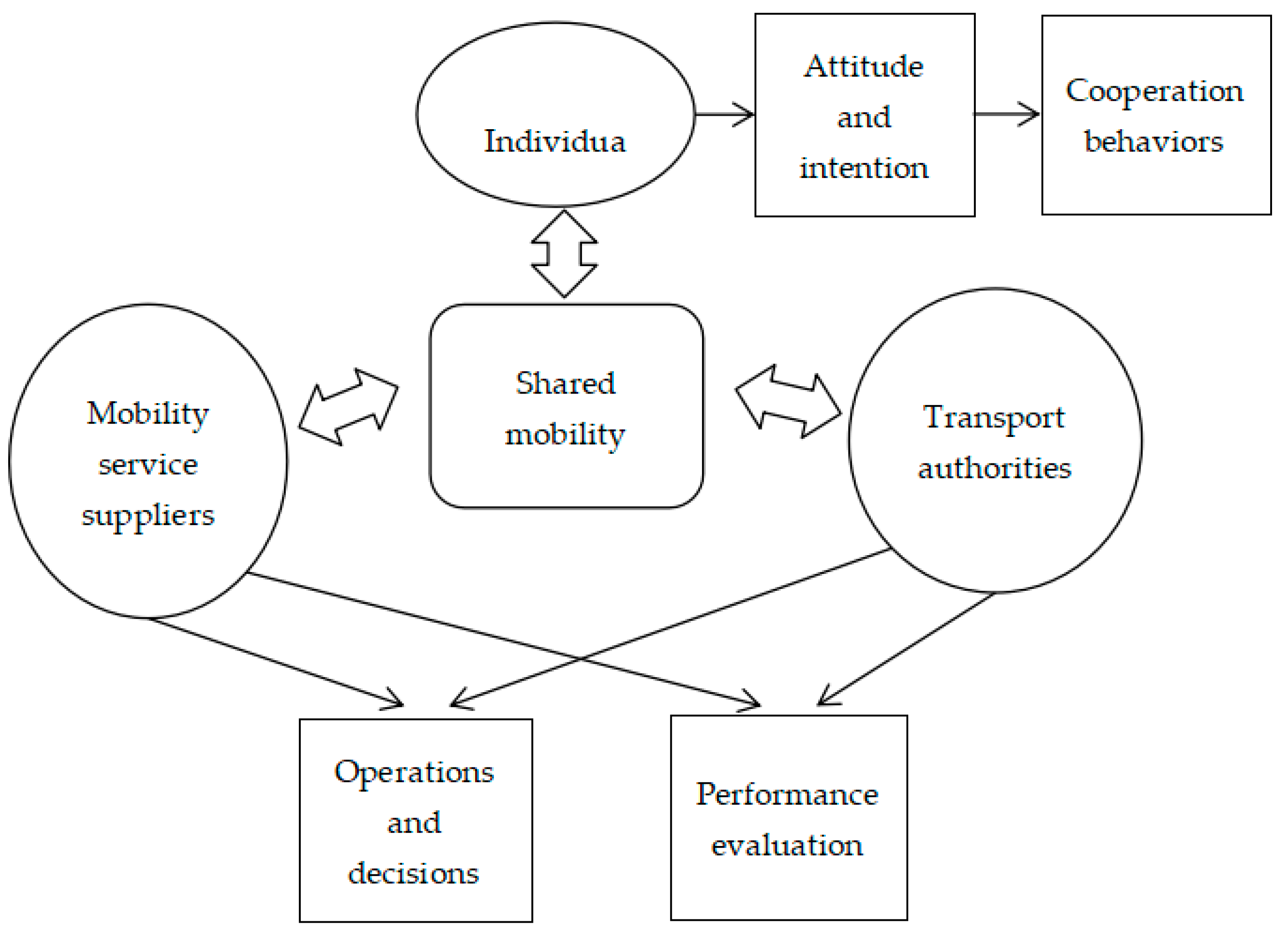

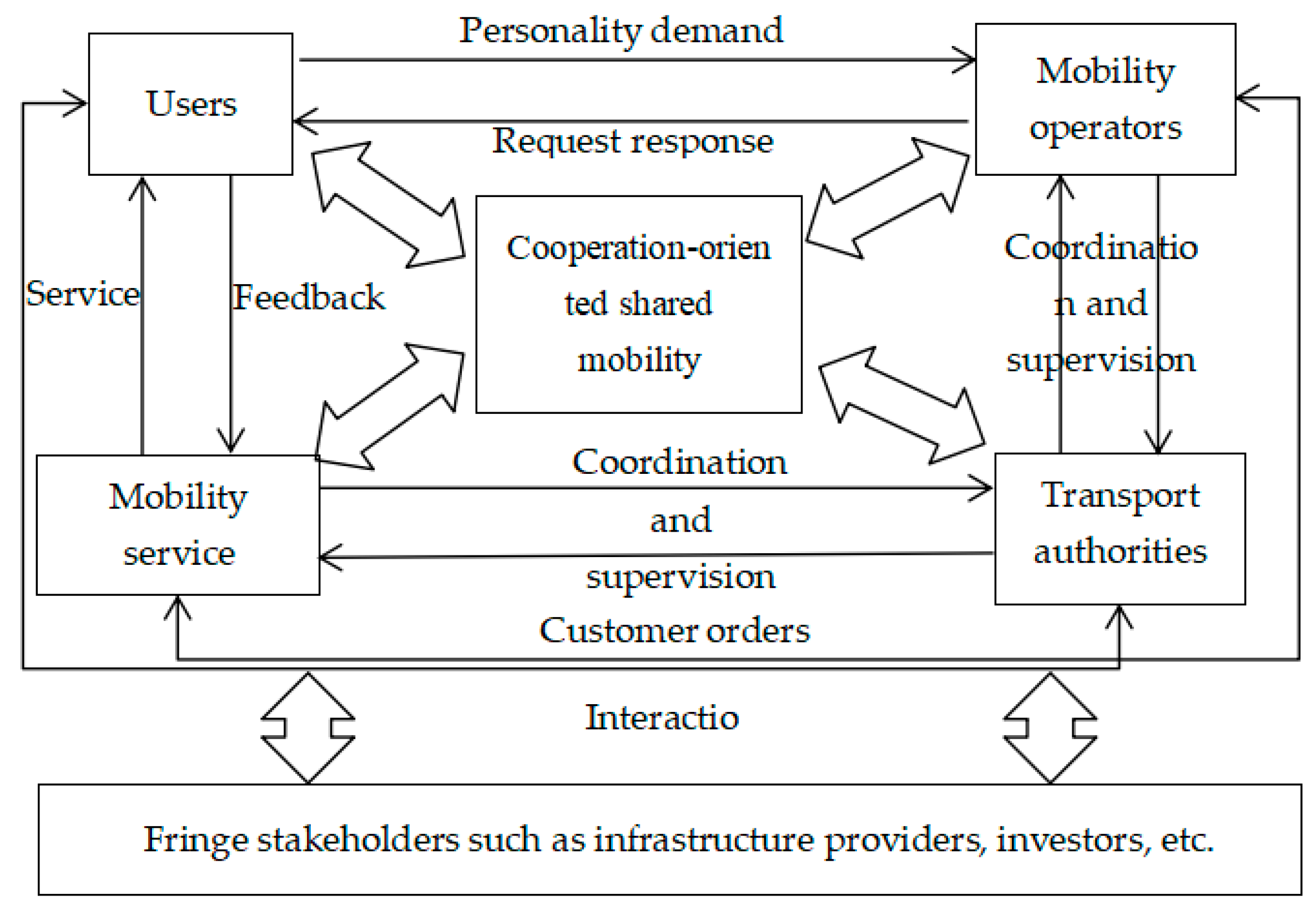

There is an increasing adoption of shared mobility for improving transport systems performance, reducing excessive private vehicle use, and making full utilization of existing infrastructure. Despite numerous studies in exploring the use of shared mobility for sustainable transport from different perspectives, how it has improved the sustainability of existing transport and what impact it has on various stakeholders are unclear. A systematic literature review, therefore, is carried out in this study on developing and adopting shared mobility for pursuing sustainable transport in urban traveling. Four emerging themes including (a) attitude and intention, (b) cooperation behaviors, (c) operations and decisions, and (d) performance evaluation have been identified, and some research gaps and challenges are discussed. An integrated framework for developing cooperation-oriented shared mobility is proposed. This leads to better understanding of share mobility and its use for sustainable transport.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

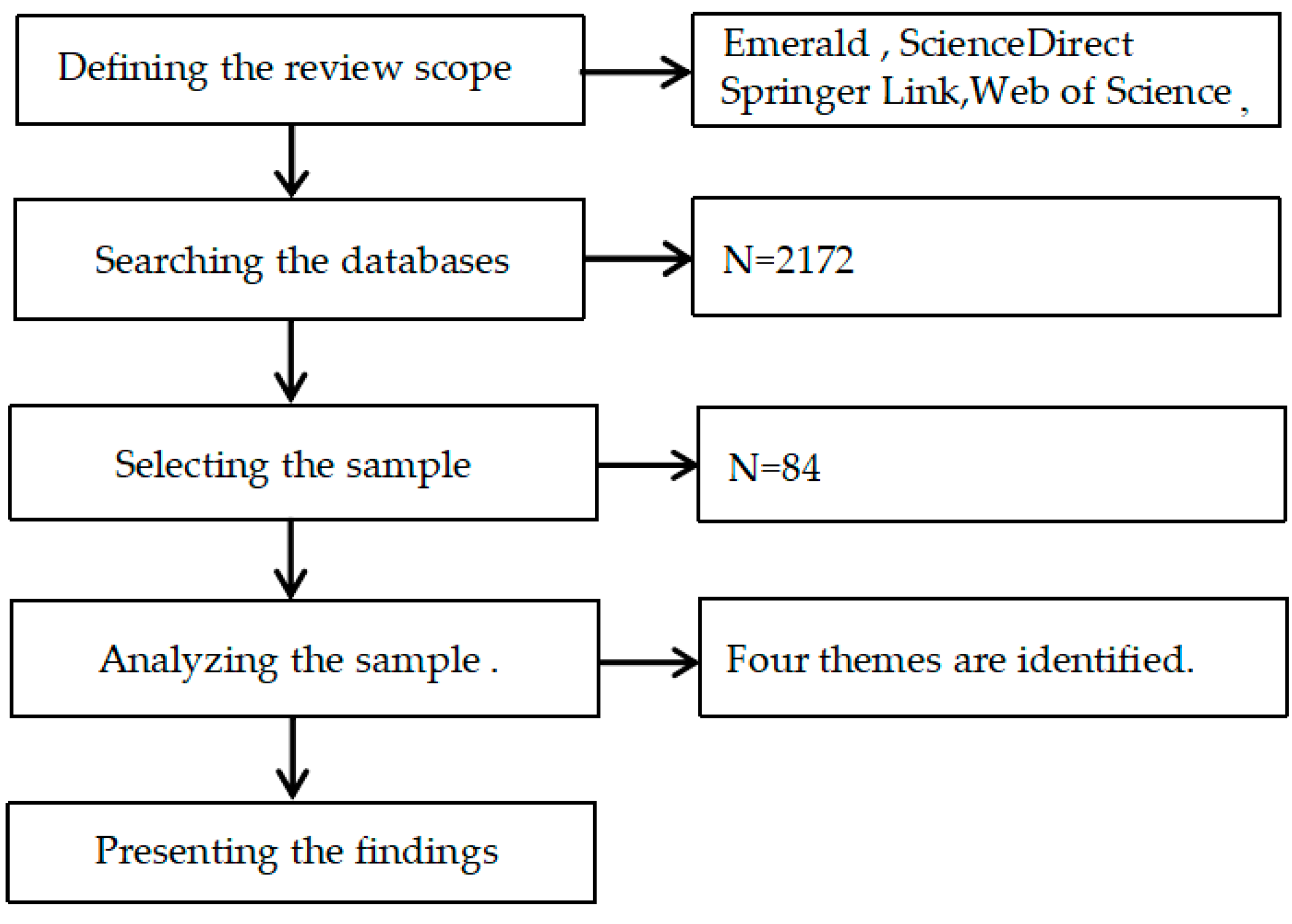

2. The Review Method

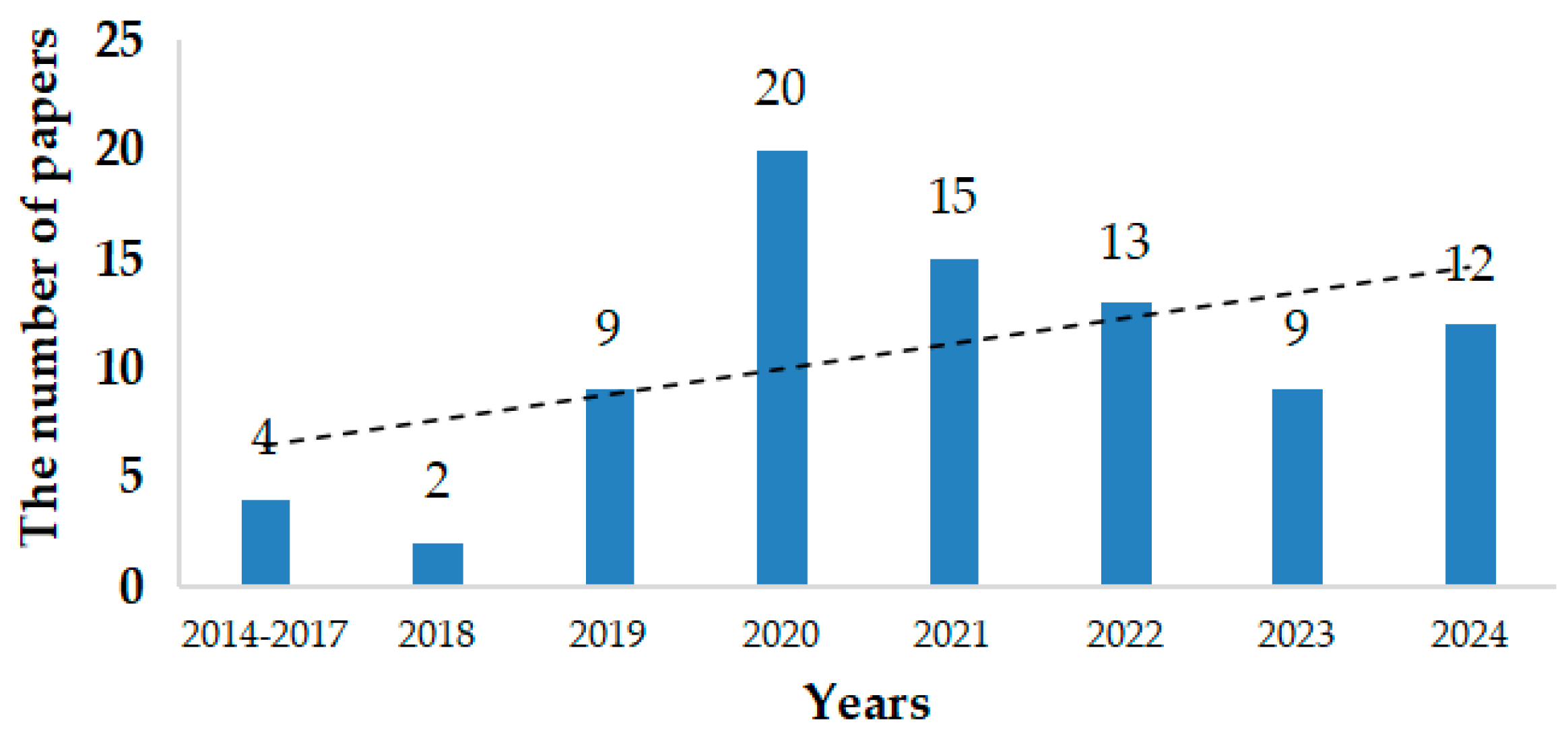

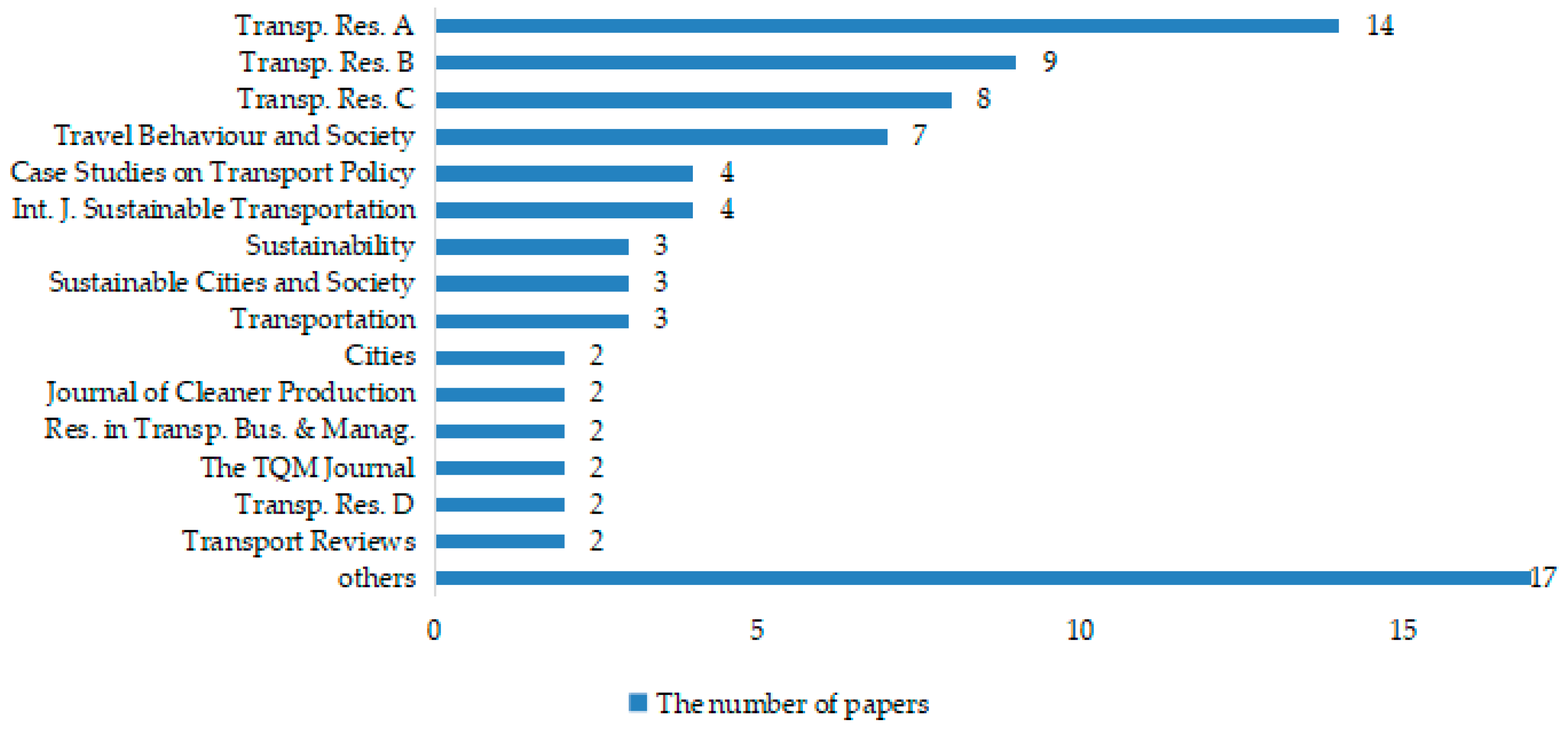

3. Descriptive Literature Analysis

4. Emerging Research Themes

5. Research Gaps and Questions

6. An Integrated Cooperation-Oriented Shared Mobility Framework

7. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- Aba, A., Esztergár-Kiss, D., 2024. A mobility pilot development process experimented through a MaaS pilot in Budapest. Travel Behaviour and Society, 37, 100846.

- Acheampong, R.A., Siiba, A., Okyere, D.K., Tuffour, J.P., 2020. Mobility-on-demand: An empirical study of internet-based ride-hailing adoption factors, travel characteristics and mode substitution effects. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies,115,102638.

- Ahmed, S., Choudhury, M.M., Ahmed, E., Chowdhury, U.Y., Asheq, A.A., 2021. Passenger satisfaction and loyalty for app-based ride-sharing services: through the tunnel of perceived quality and value for money. The TQM Journal, 33(6), 1411-1425.

- Ajzen, I., 1985. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In J. Kuhl, J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behaviour (pp. 11-39), Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Alessandretti, L., Aslak, U., Lehmann, S., 2020. The scales of human mobility.Nature, 587, 402–407.

- Alonso-González, M., Hoogendoorn-Lanser, S., van Oort, N., Cats, O., Hoogendoorna, S., 2020. Drivers and barriers in adopting Mobility as a Service (MaaS) – A latent class cluster analysis of attitudes. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,132,378-401.

- Alyavina, E., Nikitas, A., Njoya, E.T., 2022. Mobility as a service (MaaS): A thematic map of challenges and opportunities. Research in Transportation Business & Management,43,100783.

- Ambrosino, G., Nelson, J.D., Boero, M., Ramazzotti, D., 2016. From the Concept of Flexible Mobility Services to the ‘Shared Mobility Services Agency’. Paratransit: Shaping the Flexible Transport Future (Transport and Sustainability, Vol. 8), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 203-215.

- Anagnostopoulou, E., Urbančič, J., Bothos, E., Magoutas, B., Bradesko, L., Schrammel, J., Mentzas, G., 2020. From mobility patterns to behavioural change: leveraging travel behaviour and personality profiles to nudge for sustainable transportation. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems,54(1), 157–178.

- Arias-Molinares, D., García-Palomares, J.C., 2020. Shared mobility development as key for prompting mobility as a service (MaaS) in urban areas: The case of Madrid. Case Studies on Transport Policy,8(3),846-859.

- Asgari, H., Jin, X., 2019. Incorporating attitudinal factors to examine adoption of and willingness to pay for autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board,2673(8), 418–429.

- Atasoy, B., Ikeda, T., Ben-Akiva, M.E., 2016. An Innovative Concept for Paratransit: Flexible Mobility on Demand, Paratransit: Shaping the Flexible Transport Future (Transport and Sustainability, Vol. 8), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 357-375.

- Athanasopoulou, A., Deijkers, T., Ozkan, B., Turetken, O., 2022. MaaS platform features: An exploration of their relationship and importance from supply and demand perspective. Journal of Urban Mobility, 2,100028.

- Awad-Núñez, S., Julio, R., Gomez, J., Moya-Gómez, B., González, J.S., 2021.Post-COVID-19 travel behaviour patterns: impact on the willingness to pay of users of public transport and shared mobility services in Spain.European Transport Research Review,13, 20.

- Bandiera, C., Connors, R.D., Viti, F., 2024. Mobility service providers’ interacting strategies under multi-modal equilibrium. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, In press.

- Becker, H., Balac, M., Ciari, F., Mackay, K., 2020. Assessing the welfare impacts of Shared Mobility and Mobility as a Service (MaaS). Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,131,228-243.

- Benjaafar, S., Hu, M., 2020. Operations Management in the Age of the Sharing Economy: What Is Old and What Is New? Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 22(1), 93-101.

- Benjaafar, S., Kong, G., Li, X., Courcoubetis, C., 2019. Peer-to-peer product sharing: Implications for ownership, usage and social welfare in the sharing economy. Management Science, 65(2), 477–493.

- Bi, H., Ye, Z., 2021. Exploring ridesourcing trip patterns by fusing multi-source data: A big data approach, Sustainable Cities and Society, 64, 102499.

- Biehl, A., Chen, Y., Sanabria-Véaz, K, Uttal, D., Stathopoulos, A., 2019. Where does active travel fit within local community narratives of mobility space and place? Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice, 123, 269–287.

- Bushell, J., Merkert, R., Beck, M.J., 2022. Consumer preferences for operator collaboration in intra- and intercity transport ecosystems: Institutionalising platforms to facilitate MaaS 2.0. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice, 160, 160-178.

- Butler, L., Yigitcanlar,T., Paz, A., 2021. Barriers and risks of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) adoption in cities: A systematic review of the literature. Cities, 109,103036.

- Carbonara, N., Petruzzelli, A.M., Panniello, U., De Vita, D., 2024. Embracing new disruptions: Business model innovation in the transition to Mobility as a Service (MaaS). Journal of Cleaner Production, 464, 142744.

- Chahine, R., Christ, S.L., Gkritza, K., 2024a. A latent class analysis of public perceptions about shared mobility barriers and benefits. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 25, 101132.

- Chahine, R., Losada-Rojas, L.L., Gkritza, K., 2024b. Navigating post-pandemic urban mobility: Unveiling intentions for shared micro-mobility usage across three U.S. cities. Travel Behaviour and Society, 36, 100813.

- Chen, Y., Acheampong, R.A., 2023. Mobility-as-a-service transitions in China: Emerging policies, initiatives, platforms and MaaS implementation models. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 13,101054.

- Chen, X., Zheng, H., Ke, J., Yang, H., 2020. Dynamic optimization strategies for on-demand ride services platform: Surge pricing, commission rate, and incentives. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 138, 23–45.

- Chen, X.G., 2015. General Research Framework and its Properties Analysis of Traffic Flow Evolutionary Dynamics. Journal of Management Sciences in China, 18(6),58-69. (in Chinese).

- Chen, X.G., 2020. Research on Behavioural Mechanism on Travel Cooperative Intention with Information Use and Social Networks Affecting. Soft Science, 34(5), 115-123. (in Chinese).

- Chen, X.G., Deng, H., 2019. A correlation analysis of information use, social networks and cooperation consciousness in travel behaviors. Transportation Research Part F:Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 62, 819–832.

- Chen, X.G., Deng, H., 2022. Latent pattern analysis of conscious cooperation for developing sustainable transport. Transportation Research Part F:Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 86,356–369.

- Chen, X.G., Zhu, Z.T., Dai, Y.H., 2017. Exploring cooperation in traffic and transportation systems: concepts, principles and approaches. 2017 4th International Conference on Management Science and Management Innovation (MSMI 2017), Jun.,23-25.

- Christensen, T.H., Friis, F., Nielsen, M.V., 2022. Shifting from ownership to access and the future for MaaS: Insights from car sharing practices in Copenhagen. Case Studies on Transport Policy,10(2),841-850.

- Ciasullo, M.V., Troisi, O., Loia, F., Maione, G., 2018. Carpooling: travelers’ perceptions from a big data analysis.The TQM Journal, 30(5), 554-571.

- Coenegrachts, E., Vanelslander, T., Verhetsel, A., Beckers, J., 2024. Analyzing shared mobility markets in Europe: A comparative analysis of shared mobility schemes across 311 European cities. Journal of Transport Geography, 118, 103918.

- Cohen, B., Kietzmann, J., 2014. Ride on! Mobility business models for the sharing economy. Organization & Environment, 27(3), 279–296.

- Davis, F. D., 1985. A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- Delclòs-Alió, X., Gutiérrez, A., Tomàs-Porres, J., Vich, G., Miravet, D., 2023. Walking through a pandemic: How did utilitarian walking change during COVID-19?, International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 17(10), 1155-1170.

- Deng, Y., Shao, S., Mittal, A., Twumasi-Boakye, R., Fishelson, J., Gupta A., Shroff, N.B., 2022. Incentive design and profit sharing in multi-modal transportation networks. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological,163,1-21.

- Duan, S.X., Tay, R., Molla, A., Deng, H., 2022. Predicting Mobility as a Service (MaaS) use for different trip categories: An artificial neural network analysis. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice, 166, 135–149.

- Eagly, A. H., Chaiken, S., 1993. The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

- Erhardt, G.D., Roy, S., Cooper, D., Sana, B., Chen, M., Castiglione, J., 2019. Do transportation network companies decrease or increase congestion? Science Advances, 5(5), eaau2670.

- Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I., 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Freedman, J.L., Sears, D.O., Carlsmith, J.M., 1978, Social Psychology, London:Prentice-Hall.

- Gao, F., He, S., Han, C., Liang, J., 2024. The impact of shared mobility on metro ridership: The non-linear effects of bike-sharing and ride-hailing services. Travel Behaviour and Society, 37, 100842.

- Guan, X., Lierop, D.V., An, Z., Heinen, E., Ettema, D., 2024. Shared micro-mobility and transport equity: A case study of three European countries. Cities, 153, 105298.

- Guo, X., Qu, A., Zhang, H., Noursalehi, P., Zhao, J., 2023. Dissolving the segmentation of a shared mobility market: A framework and four market structure designs. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 157, 104397.

- Guyader, H., Nansubuga, B., Skill, K., 2021. Institutional Logics at Play in a Mobility-as-a-Service Ecosystem. Sustainability,13(15),8285.

- Hanaki, N., Peterhansl, A., Dodds, P.S., Watts, D.J., 2007. Cooperation in Evolving Social Networks, Management Science, 53(7), 1036–1050.

- Henao, A., Marshall, W.E., 2019. The impact of ride-hailing on vehicle miles traveled. Transportation, 46, 2173–2194.

- Hensher, D.A., Ho, C.Q., Reck, D.J., 2021. Mobility as a service and private car use: Evidence from the Sydney MaaS trial. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,145,17-33.

- Herberz, M., Hahnel, U.J.J., Brosch, T., 2020. The importance of consumer motives for green mobility: A multimodal perspective. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice, 139, 102–118.

- Ho,C.Q., 2022. Can MaaS change users’ travel behaviour to deliver commercial and societal outcomes?Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 165,76-97.

- Ho, C.Q., Hensher, D.A., Reck, D.J., 2021. Drivers of participant’s choices of monthly mobility bundles: Key behavioural findings from the Sydney Mobility as a Service (MaaS) trial. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies,124,102932.

- Hong, Z., Chen, Y., Mahmassani, H.,S., Xu, S., 2017. Commuter ride-sharing using topology-based vehicle trajectory clustering: Methodology, application and impact evaluation. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies: 85, 573–590.

- Hu, J.W., Creutzig, F., 2022. A systematic review on shared mobility in China. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 16(4), 374-389.

- Hu, M., 2021. From the classics to new tunes: a neoclassical view on sharing economy and innovative marketplaces. Production and Operations Management, 30(6), 1668-1685.

- Jian, S., Liu, W., Wang, X.L., Yang, H., Waller, S.T., 2020. On integrating carsharing and parking sharing services. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 142,19–44.

- Jin, S.T., Kong, H., Wu, R., Sui, D.Z., 2018. Ridesourcing, the sharing economy, and the future of cities. Cities, 76, 96-104.

- Karlsson, I.C.M., Mukhtar-Landgren, D., Smith, G., Koglin, T., Kronsell, A., Lund, E., Sarasini, S., Sochor, J., 2020. Development and implementation of Mobility-as-a-Service – A qualitative study of barriers and enabling factors. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice:Policy and Practice,131,283-295.

- Kayikci, Y., Kabadurmus, O., 2022. Barriers to the adoption of the mobility-as-a-service concept: The case of Istanbul, a large emerging metropolis.Transport Policy,129, 219-236.

- Ke, J.T., Yang, H., Zheng, Z.F., 2020. On ride-pooling and traffic congestion. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 142, 213–231.

- Klein, I., Ben-Elia, E., 2016. Emergence of cooperation in congested road networks using ICT and future and emerging technologies: A game-based review. Transportation Research Part C:Emerging Technologies, 72, 10–28.

- Klein, I., Ben-Elia, E., 2018. Emergence of cooperative route-choice: A model and experiment of compliance with system-optimal ATIS. Transportation Research Part F:Traffic Psychology and Behaviour,59,348–364.

- Klein, I., Levy, N., Ben-Elia, E., 2018. An agent-based model of the emergence of cooperation and a fair and stable system optimum using ATIS on a simple road network. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies,86, 183–201.

- Krauss, K., Reck, D.J., Axhausen, K.W., 2023. How does transport supply and mobility behaviour impact preferences for MaaS bundles? A multi-city approach. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 147, 104013.

- Kriswardhana, W., Esztergár-Kiss, D., 2023. A systematic literature review of Mobility as a Service: Examining the socio-technical factors in MaaS adoption and bundling packages. Travel Behaviour and Society, 31, 232–243.

- Lesteven, G., Samadzad, M., 2021. Ride-hailing, a new mode to commute? Evidence from Tehran, Iran. Travel Behaviour and Society,22,175-185.

- Li, J., Chen, D., Zhang., M., 2022a. Equilibrium modeling of mixed autonomy traffic flow based on game theory. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 166, 110-127.

- Li, X.F., Du, M.Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, J.Z., 2022b. Identifying the factors influencing the choice of different ride-hailing services in Shenzhen, China. Travel Behaviour and Society,29,53-64.

- Liljamo, T., Liimatainen, H., Pöllänen, M., Utriainen, R., 2020. People’s current mobility costs and willingness to pay for Mobility as a Service offerings.Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,136,99-119.

- Lindkvist, H., Melander, L., 2022. How sustainable are urban transport services? A comparison of MaaS and UCC.Research in Transportation Business & Management,43,100829.

- Lopez-Carreiro, I., Monzon, A., Lois, D., Lopez-Lambas, M.E., 2021a. Are travellers willing to adopt MaaS? Exploring attitudinal and personality factors in the case of Madrid, Spain. Travel Behaviour and Society,25,246-261.

- Lopez-Carreiro, I., Monzon, A., Lopez-Lambas, M.E., 2021b. Comparison of the willingness to adopt MaaS in Madrid (Spain) and Randstad (The Netherlands) metropolitan areas. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,152,275-294.

- Lyons, G., Hammond, P., Mackay, K., 2019. The importance of user perspective in the evolution of MaaS. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,121,22-36.

- Matowicki, M., Amorim, M., Kern, M., Pecherkova, P., Motzer, N., Pribyl, O., 2022. Understanding the potential of MaaS – An European survey on attitudes. Travel Behaviour and Society,27,204-215.

- Mattia, G., Mugion, R.G., Principato, L., 2019. Shared mobility as a driver for sustainable consumptions: The intention to re-use free-floating car sharing. Journal of Cleaner Production,237,117404.

- Matyas, M, Kamargianni, M., 2019. The potential of mobility as a service bundles as a mobility management tool. Transportation, 46, 1951–1968.

- Meng, L., Somenahalli, S.,, Berry, S., 2020. Policy implementation of multi-modal (shared) mobility: review of a supply-demand value proposition canvas.Transport Reviews, 40(5), 670-684.

- Meurs, H., Sharmeen, F., Marchau, V., van der Heijden, R., 2020. Organizing integrated services in mobility-as-a-service systems: Principles of alliance formation applied to a MaaS-pilot in the Netherlands. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,131,178-195.

- Mock, M., 2023. Making and breaking links: the transformative potential of shared mobility from a practice theories perspective. Mobilities, 18(3), 374-390.

- Molla, A., Duan, S.X., Deng, H., Tay, R., 2024. The effects of digital platform expectations, information schema congruity and behavioural factors on mobility as a service (MaaS) adoption. Information Technology & People,. 37, 1, 81-109.

- Moody, J., Middleton, S., Zhao, J., 2019. Rider-to-rider discriminatory attitudes and ridesharing behavior. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 62, 258–273.

- Mourad, A., Puchinger, J., Chengbin, C., 2019. A survey of models and algorithms for optimizing shared mobility. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 123,323–346.

- Muller, M., Park, S., Lee,R., Fusco, B., de Almeida Correia, G.H., 2021. Review of Whole System Simulation Methodologies for Assessing Mobility as a Service (MaaS) as an Enabler for Sustainable Urban Mobility. Sustainability,13(10),5591.

- Narayanan, S., Antoniou, C., 2023. Shared mobility services towards Mobility as a Service (MaaS): What, who and when? Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice, 168, 103581.

- Nguyen, T.,K., Hoang, N.H., Vu, 2022. A unified activity-based framework for one-way car-sharing services in multi-modal transportation networks, Transportation Research Part E:Logistics and Transportation Review, 157, 102551.

- Ofori, K.S., Anyigba, H., Adeola, O., Junwu, C., Osakwe, C.N., David-West, O., 2022. Understanding post-adoption behaviour in the context of ride-hailing apps: the role of customer perceived value. Information Technology & People,35(5),1540-1562.

- Pamucar, D., Simic, V., Lazarević, D., Dobrodolac, M., Deveci, M., 2022. Prioritization of sustainable mobility sharing systems using integrated fuzzy DIBR and fuzzy-rough EDAS model. Sustainable Cities and Society,82,103910.

- Pangbourne, K., Stead, D., Mladenović, M., Milakis, D., 2018, "The Case of Mobility as a Service: A Critical Reflection on Challenges for Urban Transport and Mobility Governance", Marsden, G. and Reardon, L. (Ed.) Governance of the Smart Mobility Transition, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 33-48.

- Rahimi, A., Azimi, G., Jin, X., 2020. Examining human attitudes toward shared mobility options and autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour,72, 133–154.

- Reck, D.J., Hensher, D.A., Ho, C.Q., 2020. MaaS bundle design. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice:,141,485-501.

- Schikofsky, J., Dannewald, T., Kowald, M., 2020. Exploring motivational mechanisms behind the intention to adopt mobility as a service (MaaS): Insights from Germany. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,131,296-312.

- Shaheen, S., Cohen, A., Yelchuru, B., Sarkhili, S., 2017. Mobility on Demand Operational Concept Report. Technical Report. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/34258.

- Shaheen, S., Cohen, A., Zohdy, I., 2016. Shared Mobility: Current Practices and Guiding Principles. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration.

- Shen, Q., Wang, Y., Gifford, C., 2021. Exploring partnership between transit agency and shared mobility company: an incentive program for app-based carpooling. Transportation, 48, 2585–2603.

- Shi, K., Shao, R., De Vos, J., Cheng, L., Witlox, F., 2021.The influence of ride-hailing on travel frequency and mode choice. Transportation Research Part D:Transport and Environment,101,103125.

- Shokouhyar, S., Shokouhyar, S., Sobhani, A., Gorizi, A.J., 2021. Shared Mobility in Post-COVID Era:New Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 67, 102714.

- Sochor, J., Strömberg, H., Karlsson, I.C.M., 2015. Implementing Mobility as a Service Challenges in Integrating User, Commercial, and Societal Perspectives. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board,2536, 1–9.

- Storme, T., De Vos, J., De Paepe, L., Witlox, F., 2020. Limitations to the car-substitution effect of MaaS. Findings from a Belgian pilot study. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,131,196-205.

- Sun, L., Teunter, R.H., Hua, G., Wu, T., 2020. Taxi-hailing platforms: Inform or Assign drivers? Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 142,197–212.

- Surakka, T., Härri, F., Haahtela, T., Horila, A., Michl, T., 2018. Regulation and governance supporting systemic MaaS innovations. Research in Transportation Business & Management,27,56-66.

- Tian, C., Tu, K., Sui, H., Sun, Qi., 2024. Value co-creation in shared mobility: The case of carpooling in China. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 205, 123481.

- Tirachini, A., 2020. Ride-hailing, travel behaviour and sustainable mobility: an international review. Transportation,47(4),2011-2047.

- Tirachini, A., Chaniotakis, E., Abouelela, M., Antoniou, C., 2020. The sustainability of shared mobility: Can a platform for shared rides reduce motorized traffic in cities? Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 117, 102707.

- Tirachini, A., Gomez-Lobo, A., 2020. Does ride-hailing increase or decrease vehicle kilometers traveled (VKT)? A simulation approach for Santiago de Chile. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 14 (3), 187–204.

- van den Berg, V.A.C, Meurs, H., Verhoef, E.T., 2022. Business models for Mobility as an Service (MaaS).Transportation Research Part B: Methodological,157,203-229.

- van Veldhoven, Z., Koninckx, T., Sindayihebura, A., Vanthienen, J., 2022. Investigating public intention to use shared mobility in Belgium through a survey. Case Studies on Transport Policy,10(1),472-484.

- Vega-Gonzalo, M., Gomez, J., Christidis, P., Vassallo, J.M., 2024. The role of shared mobility in reducing perceived private car dependency. Transportation Research Part D:Transport and Environment, 126, 104023.

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M.G., Davis, G.B., Davis, F.D., 2003. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

- Vélez, A.M.A., 2024. Environmental impacts of shared mobility: a systematic literature review of life-cycle assessments focusing on car sharing, carpooling, bikesharing, scooters and moped sharing, Transport Reviews, 44, 3, 634-658.

- Vial, G., 2019. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 28(2), 118-144.

- Vij, A., Ryan, S., Sampson, S., Harris, S., 2020. Consumer preferences for Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) in Australia. Transportation Research Part C:Emerging Technologies,117,102699.

- Wang, H., Yang, H., 2019. Ridesourcing systems: A framework and review. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 129, 122–155.

- Wilson, A., Mason, B., 2020. The coming disruption – The rise of mobility as a service and the implications for government. Research in Transportation Economics, 83,100898.

- Wolfswinkel, J. F., Furtmueller, E., Wilderom, C.P., 2013. Using grounded theory as a method for rigorously reviewing literature. European Journal of Information Systems, 22(1), 45-55.

- Wong, Y.Z., Hensher, D.A., Mulley, C. 2020. Mobility as a service (MaaS): Charting a future context. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,131, 5-19.

- Wright, S, Nelson, J.D, Cottrill, C.D., 2020. MaaS for the suburban market: Incorporating carpooling in the mix. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,131,206-218.

- Xi, H., Li, M., Hensher., D.A., Xie, C., Gu, Z., Zheng, Y., 2024. Strategizing sustainability and profitability in electric Mobility-as-a-Service (E-MaaS) ecosystems with carbon incentives: A multi-leader multi-follower game, Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 166, 104758.

- Xu, Z., Yin, Y., Chao, X., Zhu., H., Ye., J., 2021. A generalized fluid model of ride-hailing systems, Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 150, 587-605.

- Yan, C., Zhu., H., Korolko, N., Woodard, D., 2020. Dynamic pricing and matching in ride-hailing platforms. Naval research logistics, 67(8),705–724.

- Yao, R., Zhang, K., 2024. Design an intermediary mobility-as-a-service (MaaS) platform using many-to-many stable matching framework. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, In press.

- Young, M. Farber, S., 2019.The who, why, and when of Uber and other ride-hailing trips: An examination of a large sample household travel survey. Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice,119,383-392.

- Zhang, Z., Zhang, N., 2021a. A Novel Development Scheme of Mobility as a Service: Can It Provide a Sustainable Environment for China? Sustainability,13(8),4233.

- Zhang, Z.Y., Zhang, X.,2021b. Competition and coordination strategies of shared electric vehicles and public transportation considering customer travel utility. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(44), 62142–62154.

- Zhou, F., Zheng, Z., Whitehead, J., Perrons, R.K., Washington, S., Page, L., 2020. Examining the impact of car-sharing on private vehicle ownership.Transportation Research Part A:Policy and Practice, 138, 322-341.

- Zhou, T., Zhang, J., Peng, L., Zhang, S., 2022. Exploring the determinants of public transport usage and shared mobilities: A case study from Nanchang, China. Sustainable Cities and Society,87,104146.

- Zhou, X., Liu, H., Li, J., Zhang, K., Lev, B., 2023. Omega. Channel strategies when digital platforms emerge: A systematic literature review, 120, 102919.

- Zhu, J., Xie, N., Cai, Z., Tang, W., Chen, X.M., 2023. A comprehensive review of shared mobility for sustainable transportation systems. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 17(5), 527-551.

| Approaches | Methods | Theories/Models | No of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Review | None | 7 | |

| Qualitative |

Interview | Social practice theories, dynamic capability theory, systems theory | 3 |

| Case study | Innovation theory, stakeholder theory, supply-demand value proposition, technology-organization-environment framework | 8 | |

| Field study | Stakeholder theory, organizational socialization framework | 4 | |

| Quantitative |

Survey | Econometric model, behavioral theory | 17 |

| Modeling, simulation |

Game theory, evolutionary game theory | 7 | |

| mathematical model | 16 | ||

| Experiment | Data mining, statistical techniques | 9 | |

| Mixed-methods |

Interview+ Survey | None | 4 |

| Case study+ Survey | None | 6 | |

| Other | None | 3 |

| Themes | References | Approaches | Critical Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Ciasullo et al. (2018) | Text analytics | Economic and environmental efficiency, comfort, socialization, reliability, curiosity |

| Moody et al. (2019) | Survey | Discriminatory attitude | |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) | Survey | Perceived quality, value for money | |

| Li et al. (2022b) | Multinomial logistic model | User orientation, travel characteristics, perceived performance | |

| Chahine (2024a) | Latent class analysis | Benefits and barriers | |

| Intention | Mattia et al. (2019) | Structural equation modeling (SEM) | Attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control |

| Herberz et al. (2020) | SEM | Environmental motives, status, financial, independence, safety, hedonic motives | |

| Duan et al. (2022) | Survey | Costs, network externality, institutional factors, behavioral factors, environmental concerns, options, socio-economic influences | |

| van Veldhoven et al. (2022) | Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) | Environmental value, ease of use, time saving, ownership, price, compatibility, digital savviness | |

| Molla et al. (2024) | Survey | Personalization, customizability, functional integration, network integration governance, information schema congruity | |

| Chahine et al. (2024b) | SEM | Attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and social norms | |

| WTP | Asgari and Jin (2019) | SEM | Driving pleasure, reasons for mode choice, trust, technical savvy |

| Liljamo et al. (2020) | Linear regression | Costs, income, gender | |

| Vij et al. (2020) | Survey | Age, lifecycle stage | |

| Lopez-Carreiro et al. (2021a) | Cluster analysis | Control, privacy, environmental awareness, services integration | |

| Lopez-Carreiro et al. (2021b) | Gologit model | Demographic, socioeconomic, travel-related variables |

| Themes | References | Approaches | Critical Factors/Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior patterns | Chen and Deng (2019) | Cluster analysis | Three cooperation behaviors patterns |

| Biehl et al. (2019) | Focus group | The acceptance of shared mobility is different in communities | |

| Young and Farber (2019) | Statistical analysis | Ride-hailing is related to wealthy young people | |

| Bi and Ye (2021) | Data mining | Ridesourcing user patterns | |

| Vega-Gonzalo et al. (2024) | Multilevel ordered logit modeling | Shared mobility reduces private car use | |

| Critical factors | Acheampong et al. (2020) | SEM | Ease of use, safety risks, control, car dependent lifestyle |

| Schikofsky et al. (2020) | SEM | Autonomy, competence, feeling of being social groups, usefulness | |

| Lesteven and Samadzad (2021) | Logit model | Smartphone use and income level | |

| Shi et al. (2021) | Logistic model | Accessibility to bus station | |

| Zhou et al. (2022) | Logit model | Weather condition, travel time, safety | |

| Formulation and evolution | Chen (2015) | Game theory | Cooperation behaviors |

| Anagnostopoulou et al. (2020) | Experiment | Positive results on behavioral changes | |

| Chen (2020) | Latent class cluster analysis | Cooperation is related to information use and social networks | |

| Li et al. (2022a) | Game theory | Cooperation can be developed | |

| Gao et al. (2024) | Random forest model | Bike-sharing and ride-hailing have non-linear effect on the use of metro |

| Themes | References | Approaches | Critical Factors/Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single shared mobility | Hong et al. (2017) | Data-driven clustering | Carpool programs contribute to less congested traffic and environment-friendly travel |

| Chen et al. (2020) | Mathematical model | Dynamic strategies help platforms adjust supply and demand for achieving optimization goals | |

| Jian et al. (2020) | Mathematical model | Bundled mobility offerings can improve providers’ profit and individuals’ social welfare | |

| Ke et al. (2020) | Macroscopic diagram | An optimal model for minimizing the time cost | |

| Sun et al. (2020) | Queueing theory | Insights on how platforms allocate rides | |

| Yan et al. (2020) | Mathematical model | Price variability is reduced and capacity utilization, trip throughput, and welfare are increased | |

| Xu et al.(2021) | Macroscopic fluid model | A model for policy control | |

| Nguyen et al. (2022) | Mathematical model | A mathematical model | |

| Guo et al. (2023) | Game/integer linear program | Market design can reduce inefficiency and promote healthy competition | |

| MaaS | Karlsson et al. (2020) | Case study | A consistent characterization of business models |

| Meurs et al. (2020) | Case study | A conceptual framework for cooperation | |

| Butler et al. (2021) | Literature review | Desired MaaS outcomes, supply side barriers and demand side risks related to MaaS adoption | |

| Guyader et al. (2021) | Case study | Experimenting innovative solutions for key learnings about shared mobility ecosystems and stakeholders | |

| Alyavina et al. (2022) | Literature review | Areas for affecting MaaS’ capacity | |

| Athanasopoulou et al. (2022) | Literature review | Non-features requirements are highly valued | |

| Xi et al. (2024) | Mathematical model | A novel e-MaaS ecosystem | |

| Yao and Zhang (2024) | Mathematical model | A new MaaS platform design | |

| MSM | Cohen and Kietzman (2014) | Qualitative exposition | Existing models are fraught with conflicts, a merit model is the most promising one |

| Ambrosino et al. (2016) | Literature review | The role of a shared mobility centre in MSM use | |

| Meng et al. (2020) | Literature review | Shared mobility requires collaborative partnership | |

| Shokouhyar et al. (2021) | Delphi approach | 18 challenges and 12 constructs are critical to the sustainability of MSM | |

| Deng et al. (2022) | Game theory | Platform profit increases through cooperation | |

| Narayanan and Antoniou (2023) | Multinomial logit model | A choice model for selecting mobility services | |

| Bandiera et al. (2024) | Mathematical model | A novel mathematical model on the interaction between providers and users |

| Themes | References | Approaches | Critical Factors/Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific shared mobility | Jin et al. (2018) | Literature review | Ride-sourcing affects efficiency, equity, and sustainability |

| Erhardt et al. (2019) | Regression model |

TNCs contribute to growing traffic congestion | |

| Henao and Marshall (2019) | Experiment and survey | Ride-hailing increases VKT | |

| Shen et al. (2021) | Regression | Carpooling generates promising outcomes | |

| Tirachini and Gomez-Lobo (2020) | Monte Carlo simulation | Ride-hailing increases occupancy rate, leading to increased VKT | |

| Tirachini et al. (2020) | Survey | VKT depends on various factors | |

| Coenegrachts et al. (2024) | Latent class clustering | Individuals have access to shared mobility | |

| Vélez (2024) | Literature review | Travel behaviour, shared mobility modes, and local contexts are critical | |

| Shared mobility performance | Matyas and Kamargianni (2019) | A Mixed MNL model | MaaS bundles can introduce more travelers to use shared modes |

| Reck et al. (2020) | Experiment | A framework compare stated choice studies | |

| Hensher et al. (2021) | Choice model | MaaS can change travel behaviour | |

| Ho et al. (2021) | Logit choice model | PAYG is a preferred option for shared mobility | |

| Lindkvist and Melander (2022) | Literature review | Sustainable business models for shared mobility | |

| Muller et al. (2021) | Literature review | Comparative assessment of simulation tools for shared mobility solutions | |

| Zhang and Zhang (2021a) | Literature review | Cooperation, government support, and data sharing are critical to shared mobility projects | |

| van den Berg et al. (2022) | Game theory | MaaS benefits consumers by increasing competition and removing marginalization | |

| Kriswardhana and Esztergár-Kiss (2023) | Literature review | Environment factors and user groups | |

| Carbonara et at. (2024) | Case study | The MaaS operations process | |

| Impact assessment | Arias-Molinares and García-Palomares (2020) | Case study | Governance and collaboration is critical for developing MaaS |

| Becker et al. (2020) | Simulation | MaaS increases system efficiency, while substantially reducing energy consumption | |

| Christensen et al. (2022) | Interview | MaaS should consider embodied routinization and entanglement of mobility practices | |

| Ho (2022) | Choice modeling | MaaS affects travel behaviour | |

| Krauss et al. (2023) | Preference experiment | Shared mobility use reduces car use | |

| Aba and Esztergár-Kiss (2024) | Case study | MaaS is effective for reducing private car use |

| Themes | Topics | Gaps | Research Questions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude and intention | Attitude |

|

|

Ciasullo et al. (2018); Asgari and Jin (2019); Liljamo et al. (2020); Vij et al. (2020); Lopez-Carreiro et al. (2021a,2021b); Duan et al.(2022); Veldhoven et al. (2022); Molla et al. (2024); Chahine et al. (2024b) |

| Intention |

|

|||

| Willingness to pay | ||||

| Cooperation behaviors | Behavior patterns |

|

|

Chen and Deng (2019); Young and Farber (2019); Acheampong et al. (2020); Schikofsky et al. (2020); Lesteven and Samadzad (2021); Shi et al. (2021); Zhou et al. (2022); Li et al. (2022a); Gao et al. (2024); Vega-Gonzalo et; al. (2024) |

| Critical factors |

|

|||

| Formulation and evolution |

|

|||

| Operations and decisions | Single shared mobility |

|

|

Hong et al. (2017); Chen et al. (2020); Jian et al. (2020); Butler et al. (2021); Xu et al.(2021); Alyavina et al. (2022); Athanasopoulou et al. (2022); Guo et al. (2023); Xi et al. (2024); Yao and Zhang (2024) |

| MaaS | ||||

| MSM | ||||

| Performance evaluation | Specific shared mobility |

|

|

Jin et al. (2018); Erhardt et al. (2019); Reck et al. (2020); Tirachini and Gomez-Lobo (2020); Hensher et al. (2021); Muller et al. (2021); Zhang and Zhang (2021a); Lindkvist and Melander (2022); Krauss et al. (2023); Kriswardhana and Esztergár-Kiss (2023); Aba and Esztergár-Kiss (2024) |

| Shared mobility development |

|

|||

| Impact assessment |

| Transport mode | Cooperation | Operations | Output | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shared mobility | Sharing vehicles | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Jian et al. (2020); Narayanan and Antoniou (2023); Chahine et al. (2024b) |

| Ridesharing | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Hong et al. (2017); Ke et al. (2020); Narayanan and Antoniou (2023); Vega-Gonzalo et al. (2024) | |

| On-demand ride services | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Young and Farber (2019); Sun et al. (2020); Xu et al. (2021); Li et al. (2022b); Guo et al. (2023) | |

| Micro-mobility | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Shi et al., (2021); Zhou et al. (2022); Zhu et al. (2023) | |

| Non-shared mobility | Private vehicle | Inconspicuous | Low | Moderate /Inferior | Zhou et al. (2020); Mock (2023); Vega-Gonzalo et al. (2024) |

| Other ownership modes | Inconspicuous | Low | Moderate /Inferior | Meng et al. (2020); Shokouhyar et al. (2021); Delclòs-Alió et al. (2023) |

|

| MaaS | Conspicuous | High | Excellent | Alonso-González et al. (2020); Meurs et al. (2020); Butler et al. (2021); Alyavina et al. (2022); Xi et al. (2024) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).