1. Introduction

Recently, the nonlocal macro-meso-scale consistent damage (NMMD) model (Lu and Chen 2020 [

1]; Chen et al. 2021 [

2]) has been applied to various static and dynamic fracture problems in the manner of articulation, accuracy and effectiveness. These applications include mixed-mode cracking problems (Ren et al. 2024 [

3]; Lu et al. 2024 [

4]), direct-shear fracture (Ren et al. 2023 [

5]), dynamic crack branching (Lu and Chen 2021 [

6]), compression fracture of concrete (Ren et al. 2024 [

7]), anisotropic cracking of rocks (Xia et al. 2024 [

8]) and rate-dependent failure (Zhao et al. 2024 [

9]). However, the influence radius (also called the characteristic length) in NMMD model, though proved to be necessary for the mesh insensitivity of strain-softening regime, remains to be estimated indirectly with considerable arbitrariness.

The NMMD model still belongs to the family of nonlocal damage theories, which can be traced back to the remarkable works of Eringen (1981 [

10]) and Bažant et al. (1984 [

11]). Whatever form is used in constructing damage variable (Bažant and Jirásek 2002 [

12]), the integral-type or the gradient-enhanced approach, (strictly speaking, the NMMD model should be classified as the integral-type), the common feature of these nonlocal theories is the involvement of characteristic length to avoid the mesh-size sensitivity. Nonetheless, there is no broad acceptance of consensus on the interpretative declaration of characteristic length in nonlocal models, such as nonlocal-integral damage model (Bažant and Pijaudier-Cabot 1989 [

13]; Bažant and Jirásek 2002 [

12]), peridynamics (Silling 2000 [

14]; Silling and Lehoucq 2007 [

15]), phase field model (Bourdin et al. 2000 [

16]; Bourdin et al. 2008 [

17]; Wu 2017 [

18]; Feng et al. 2021 [

19]) and gradient-enhanced model (Peerlings et al. 1996 [

20]; Xue and Ren 2024 [

21]). Natural questions emerge about the characteristic length employed in nonlocal models. Is it a mathematically fictitious parameter or physically-based material property? If it is a material property, then is it identifiable and measurable by the underlying physical experiment? How can it relate to ordinary material-constants?

This paper, focusing on the NMMD model and its macro-meso-scale consistent mechanism, aims to answer these above questions by experimental, numerical and theoretical investigations. It should be stressed that we limit ourselves to brittle materials like PMMA and currently do not deal with quasi-brittle and ductile fractures for the sake of preliminary exploration.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 firstly states the fact that the conventional local criteria cannot adequately interpret and predict the experimentally-observed results of tests with various sizes of defect due to the lack of involving characteristic length.

Sections 3 briefly introduces the basic idea of NMMD model and its application to the analysis of brittle materials like polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA). The corresponding results and discussions are arranged in

Section 4, where the theoretical calibration of the characteristic length in NMMD model is identified for the first time. Comparisons with other modified criteria involving characteristic length are also discussed in

Section 5. Besides, in

Section 6 theoretical calibration of characteristic length is proved to be suitable for problems of mixed-mode fracture with stress singularity. Finally, the main conclusions are drawn in

Section 7, followed by an

Appendix A.

2. Statement of the Problem: Crack Onset at Non-Singular Stress Concentration

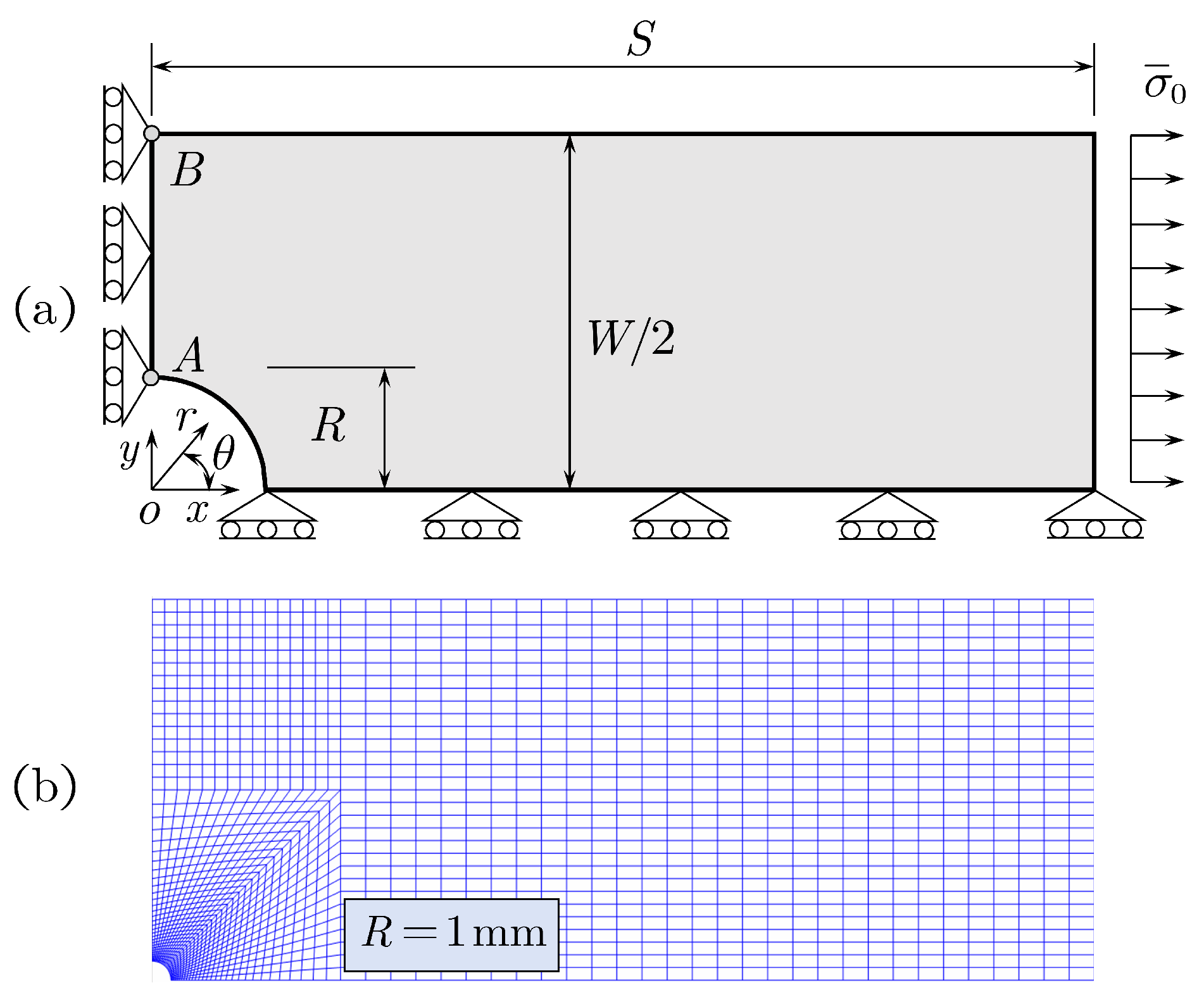

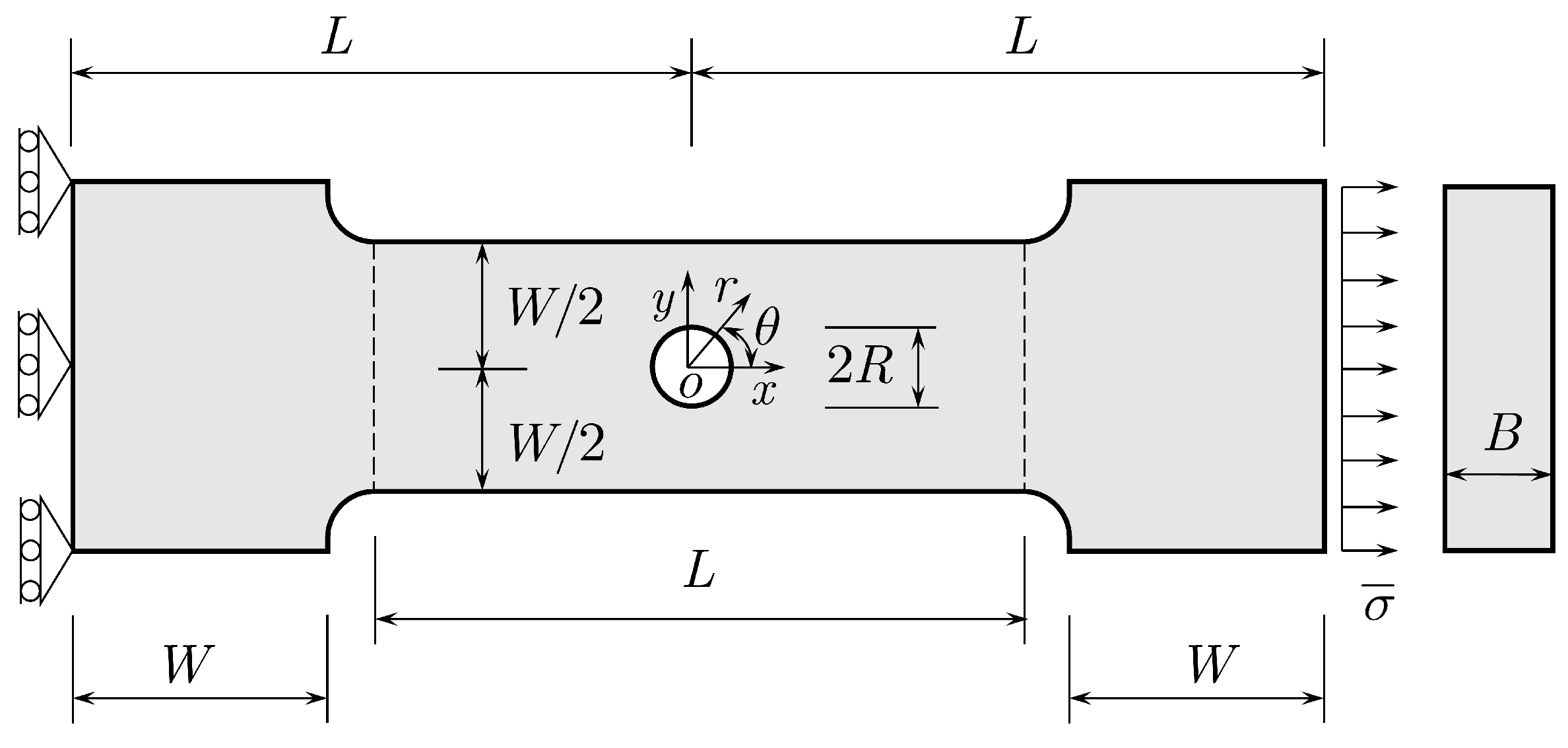

Shown in

Figure 1 is the dog-bone specimen made of PMMA material, in which a circular hole with the diameter

is preset at the central of the specimen. These specimens, subjected to a uniaxial tension

were experimentally conducted by Sapora et al. (2018 [

22]) with the following dimensions:

,

, and thickness

. The basic mechanical properties of PMMA material (Sapora et al. 2018 [

22]) are listed in

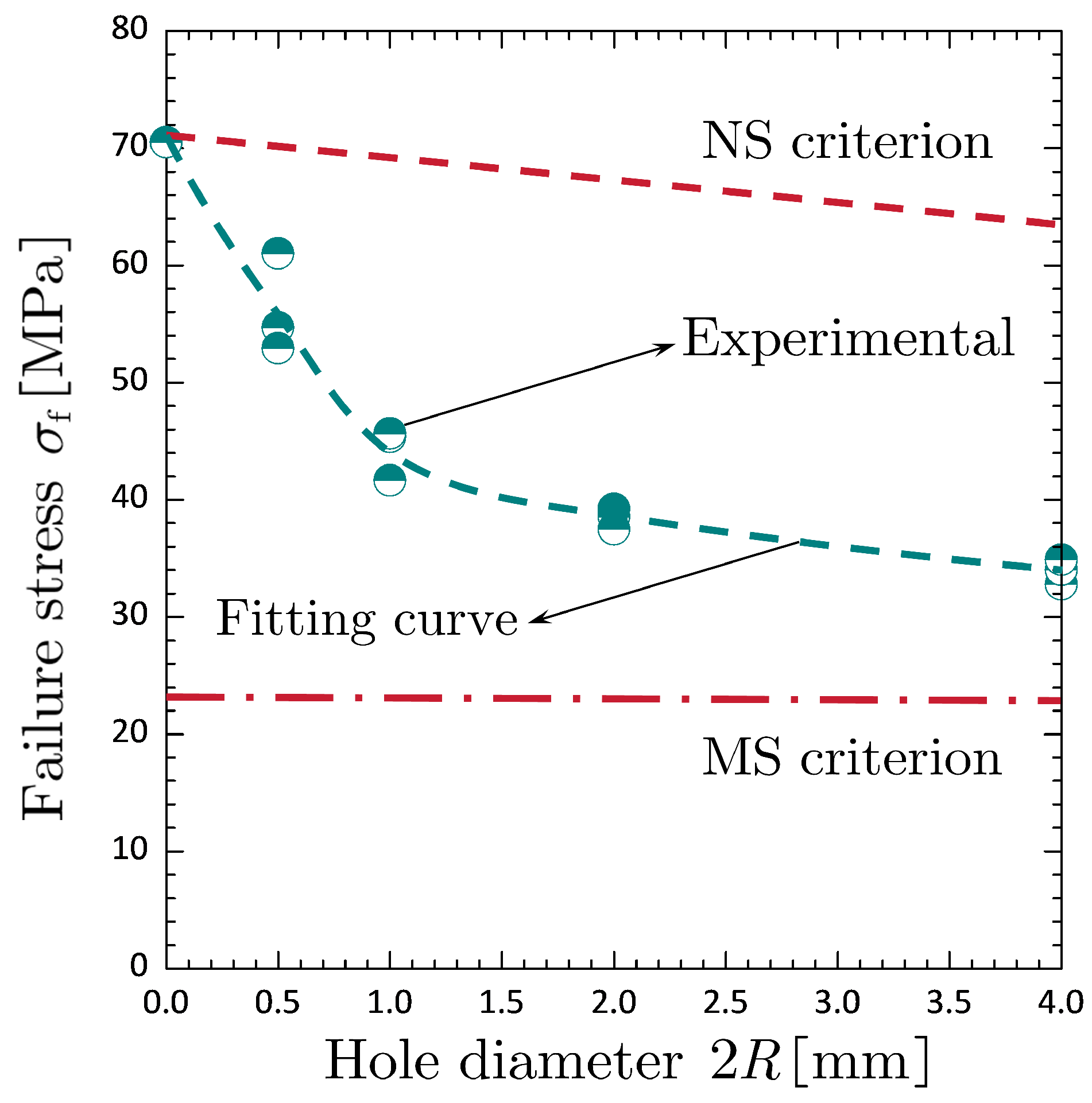

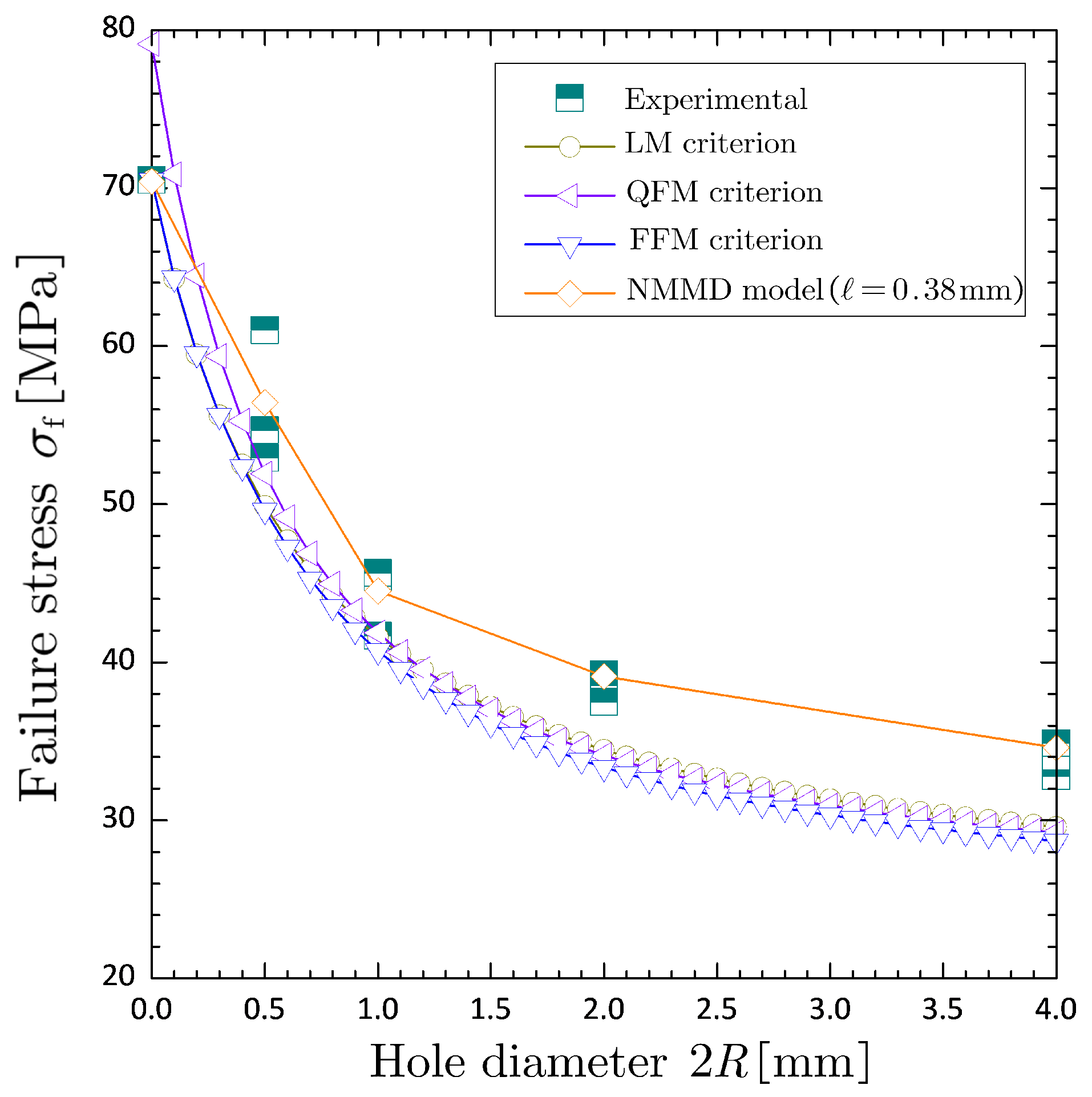

Table 1, and the experimental results of failure stress

, which is defined as the ultimate load divided by the minimum cross area, against the hole diameter are plotted in

Figure 2. It can be seen that the failure stress of central-holed specimens strongly depends on the size of circular hole. In particular, the failure stress asymptotically and nonlinearly increases as the diameter of circular hole decreases, and it reaches the tensile strength

as the size of circular hole tends to zero.

As is well known, referring to the polar coordinate system

, the stress distribution around the circular hole within an infinite plate under the uniaxial loading is given by (Timoshenko and Goodier 1951 [

42], p.80)

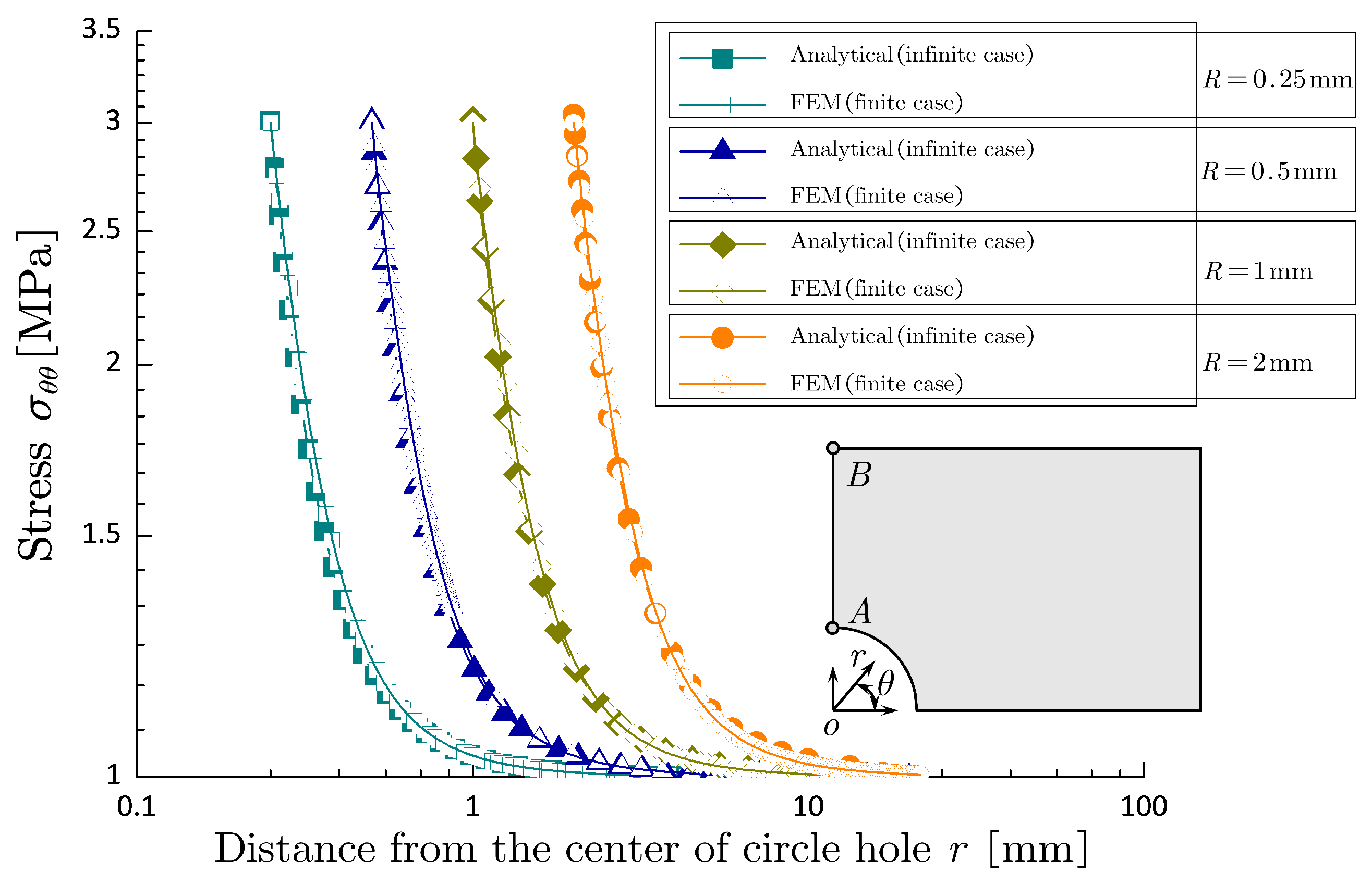

It is checked in

Appendix that Equation (

1) is still sufficiently suitable for the dog-bone specimens with the finite size.

For brittle cracking problems with non-singular stress concentration, in engineering design and analysis it was usually believed that either the maximum stress (MS) criterion

or the net stress (NS) criterion

would provide predictions of satisfaction. The predicted results of the two commonly-used criteria are also plotted in

Figure 2, however, excepting the case without hole it is clearly observed that both of them are significantly different from the mean values of experimental results.

In terms of the cases of

, the discrepancy between predictions of the two commonly-used criteria and experimental results manifests that the NS criterion predicts the upper bound of the real failure stress, while the MS criterion provides the lower bound. Similar experimental results (e.g., Carter 1992 [

23], Li and Zhang 2005 [

24]; Torabi et al. 2022 [

25]), though not shown here, also confirm that both the MS criterion and the NS criterion, without involving some kind of characteristic length, are far from being satisfactory to handle crack onset from a hole boundary.

In the following, the NMMD model will be employed to analyze the above dog-bone specimens and provide insight into the problem of crack onset at non-singular stress concentration.

3. The NMMD Model for PMMA-like Materials

In this section, the basic idea of NMMD model and its application to the analysis of PMMA-like materials will be briefly summarized and described correspondingly. For more aspects of theoretical detail and numerical implementation of NMMD model, the interested reader can refer to Lu and Chen (2020 [

1]) and Chen et al. (2021 [

2]).

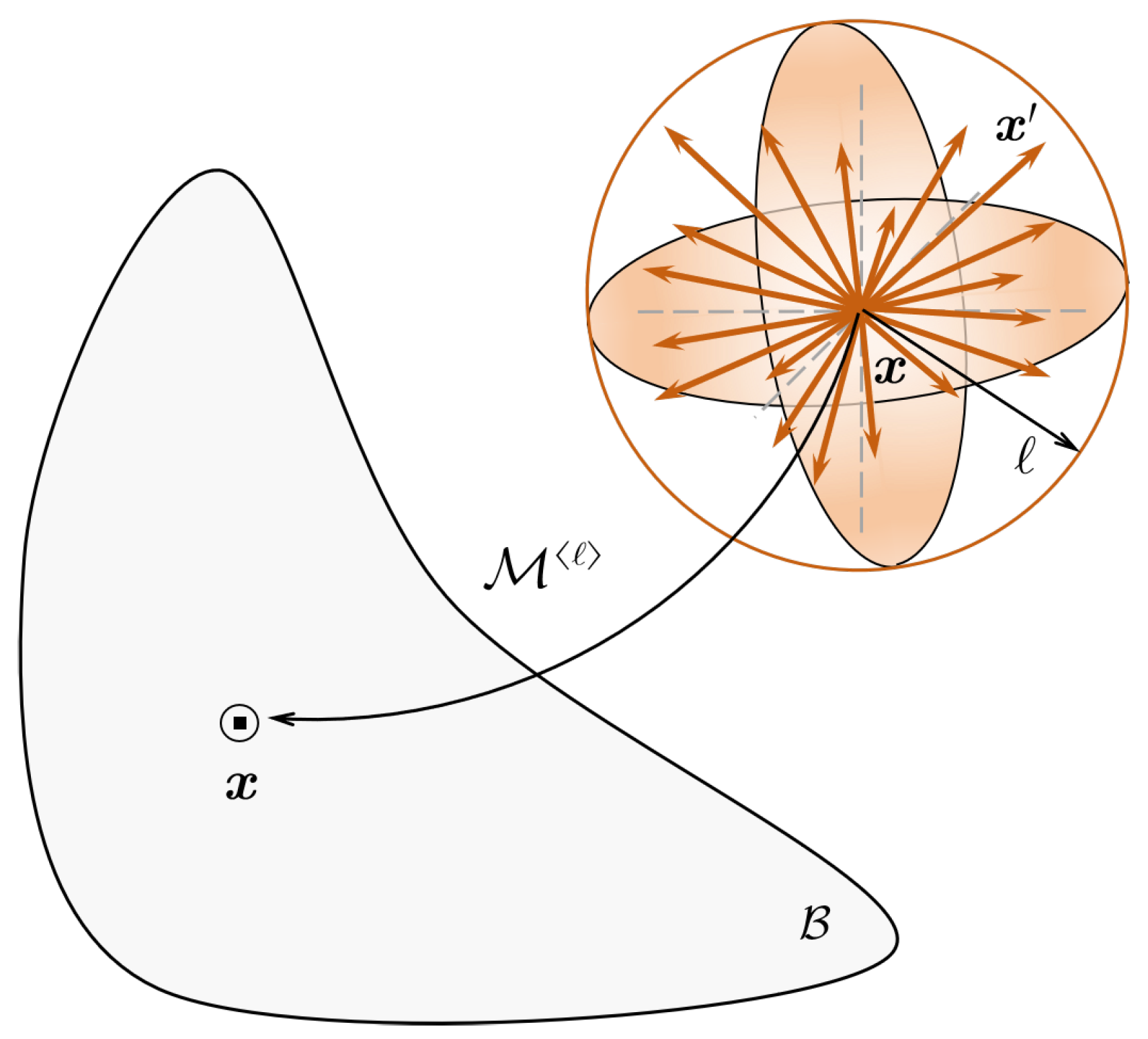

3.1. General Formulation of NMMD Model

Let

(

) be the reference configuration of a solid body, and

denote its external boundary. Given the influence radius (also called the characteristic length)

, the mesoscopic structure (see

Figure 3) assigned to the solid body is defined as

where

is the neighborhood of material point

, and

denotes the Euclidean norm. It is noted that such mesoscopic structure in essentially the simplest case of the n-point meso-structures (Chen et al. 2024 [

26]).

Denote the set

with

as the time of interest, and the map

be the displacement vector field. The deformation intensity measure of a material point-pair is expressed by the natural deformation (also called predominant elongation)

where

is the unit direction vector. The meso-scale damage can be described by the composition (Lu and Chen 2020 [

1])

where

is the meso-scale damage evolutionary rule required to be a monotone nondecreasing function,

is the quantity related to the deformation history of point-pair, and

is the critical threshold.

Once the natural deformation of material point-pair exceeds the critical threshold, it leads to the geometric breaking of the influence domain, which can be measured by the topology damage (Lu and Chen 2020 [

1])

where

is the influence domain,

is the weighted Lebesgue measure, and

.

To establish the relationship between the geometry-based damage

and the energy-based one

, a continuous convex function

called the energetic degradation factor is employed as follows

Noting the definition of energy-based damage

i.e., the ratio of the current Helmholtz free energy density

to the elastic strain energy density

for the appropriate strain tensor

, and applying the Coleman-Noll procedure (Li et al. 2014 [

43]) in continuum damage mechanics, the governing equation of NMMD model reads

In Equation (

10), the stress tensor is recognized as

which is called the nonlocal macro-meso-scale consistent constitutive relationship, and

is the total body-force density including the inertial term

. The boundary conditions are subjected as

where

and

are the prescribed surface force and displacement vector acting on the corresponding boundaries

and

with the outward unit normal vector

.

3.2. Application to PMMA-like Materials

The general formulation of NMMD model described in Subsection 3.1 is well suited to a wide range of applications, including brittle and ductile fracture. For PMMA-like materials investigated herein, we consider the following assumptions: (I) The solid is made up of an isotropic, homogeneous brittle material; (II) The displacement gradient is small, i.e., the strain tensor can be linearized as , in which the superscript denoted the transpose. In addition, the residual stress in the reference configuration vanishes; (III) The body is subjected to quasi-static loading such that the loading-rate effect and the inertial force () can be ignored.

With these assumptions, the NMMD model could be simplified. In particular, the elastic strain energy density in Equations (

9) and (

10) is the well-known Navier-Lamé potential function (Gurtin 1981 [

44])

where

E and

are Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio respectively,

and

correspondingly indicate the Frobenius norm and the trace operator. The meso-scale damage evolutionary rule in Equation (

6) is simultaneously reduced to the Heaviside step function, i.e.,

and for brittle material the energetic degradation factor in Equations (

8) and (

10) takes the following monomial

where the power

p is the degradation parameter.

It should be noted that for the quasi-static cracking problems at each virtual time step (namely the load increment) the standard finite element procedure equipped with the local arc-length method (May and Duan 1997 [

27]) is employed to obtain the complete equilibrium solutions of NMMD model, including descending branch and snap-back behaviors in the load-deflection response after attaining the peak-load.

4. Results and Discussions: Crack Onset of the Dog-Bone Specimens Without and With Hole

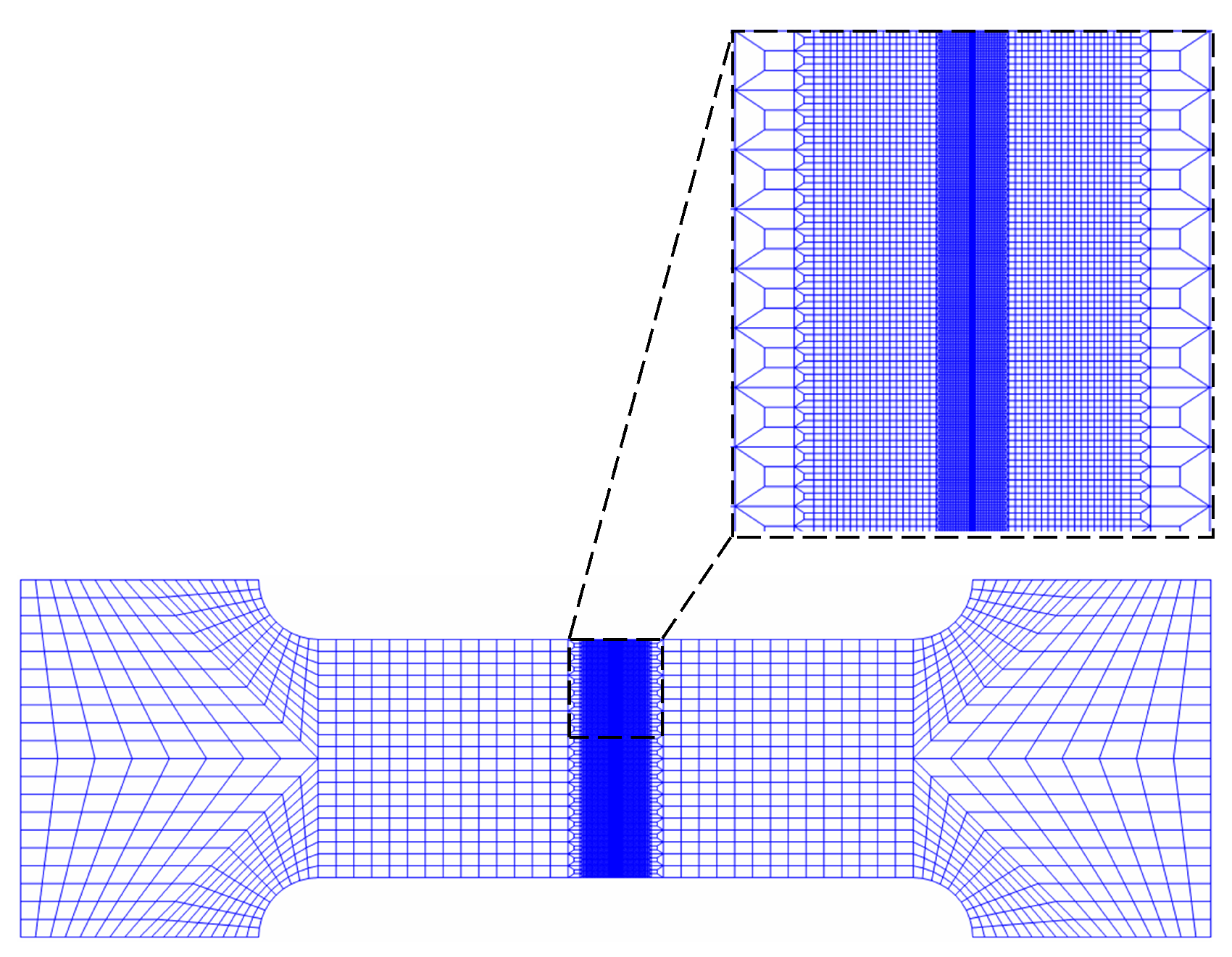

The dog-bone specimens described in

Section 2 are revisited by the NMMD model, and the finite element mesh is shown in

Figure 4. The basic mechanical properties of PMMA material listed in

Table 1 are also adopted in the analysis, and all the specimens with and without hole are considered as plane stress problems.

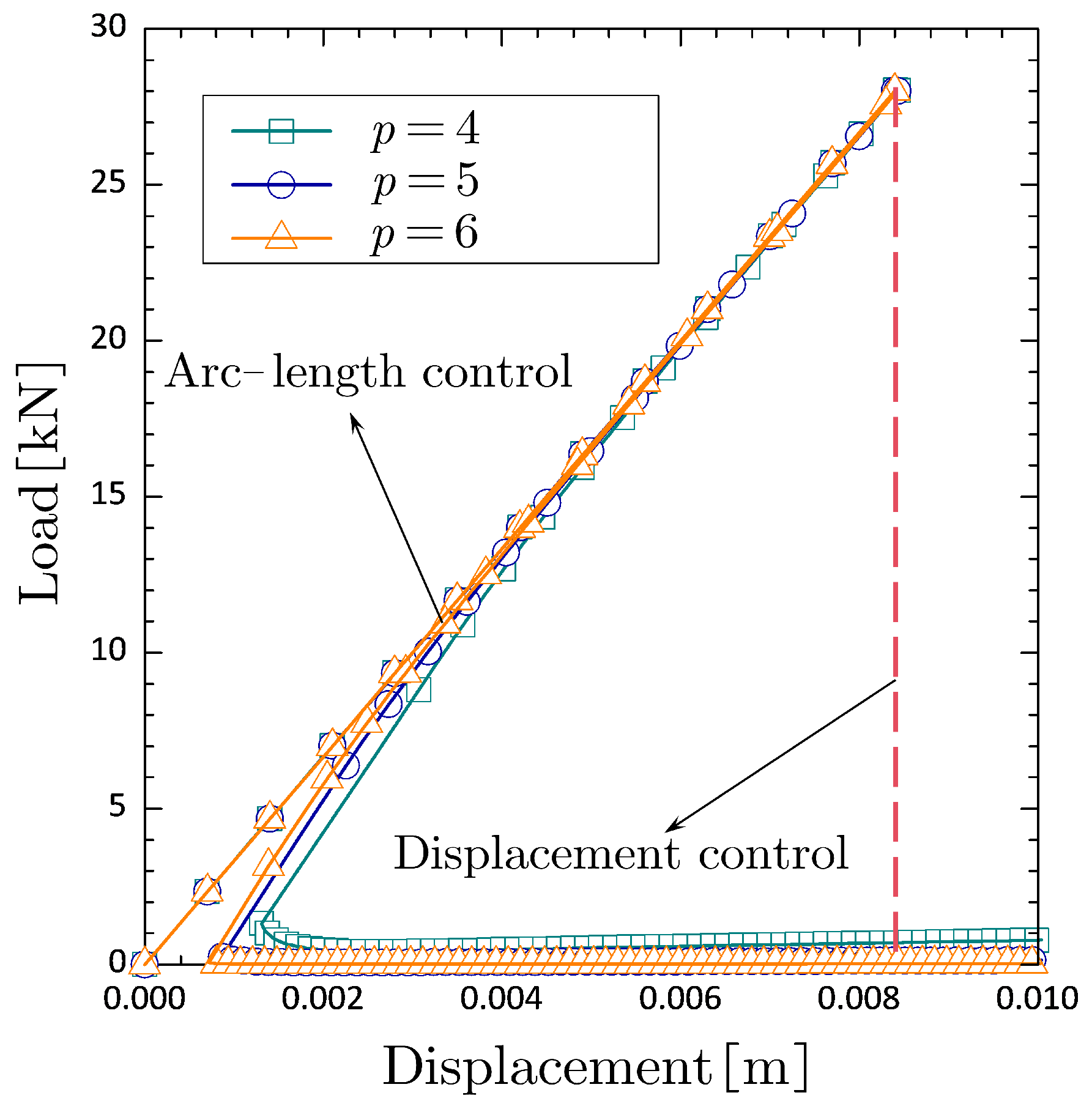

4.1. Dog-Bone Specimen Without Hole

As can be seen in

Section 3, besides the two ordinary elasticity constants (namely Young’s modulus

E and Poisson’s ratio

), there are three additional parameters to be determined in the failure process analysis, i.e., the degradation parameter

p, the critical threshold

and the influence radius

ℓ. In this subsection, we take the dog-bone specimen without hole as the first example to illustrate how these parameters influence the numerical results. Listed in

Table 2 is the parameter setting for various degradation parameters (namely

), and the corresponding results of NMMD model are shown in

Figure 5.

When equipped with the local arc-length method (May and Duan 1997 [

27]), rather than the ordinary displacement control method, as can be seen, the NMMD model can capture the visible snap-back behavior in the post-peak regime of load-deformation curve. Meanwhile, it can be observed that the load-deformation curves obtained from NMMD model are almost the same everywhere as long as the degradation parameter is suitably large (e.g.,

). In particular, the peak-load of all cases uniformly converges to

, which is quite closed to the experimental result

. These investigations highlight the ability of NMMD model to capture the whole process of brittle fracture without given pre-existing defects.

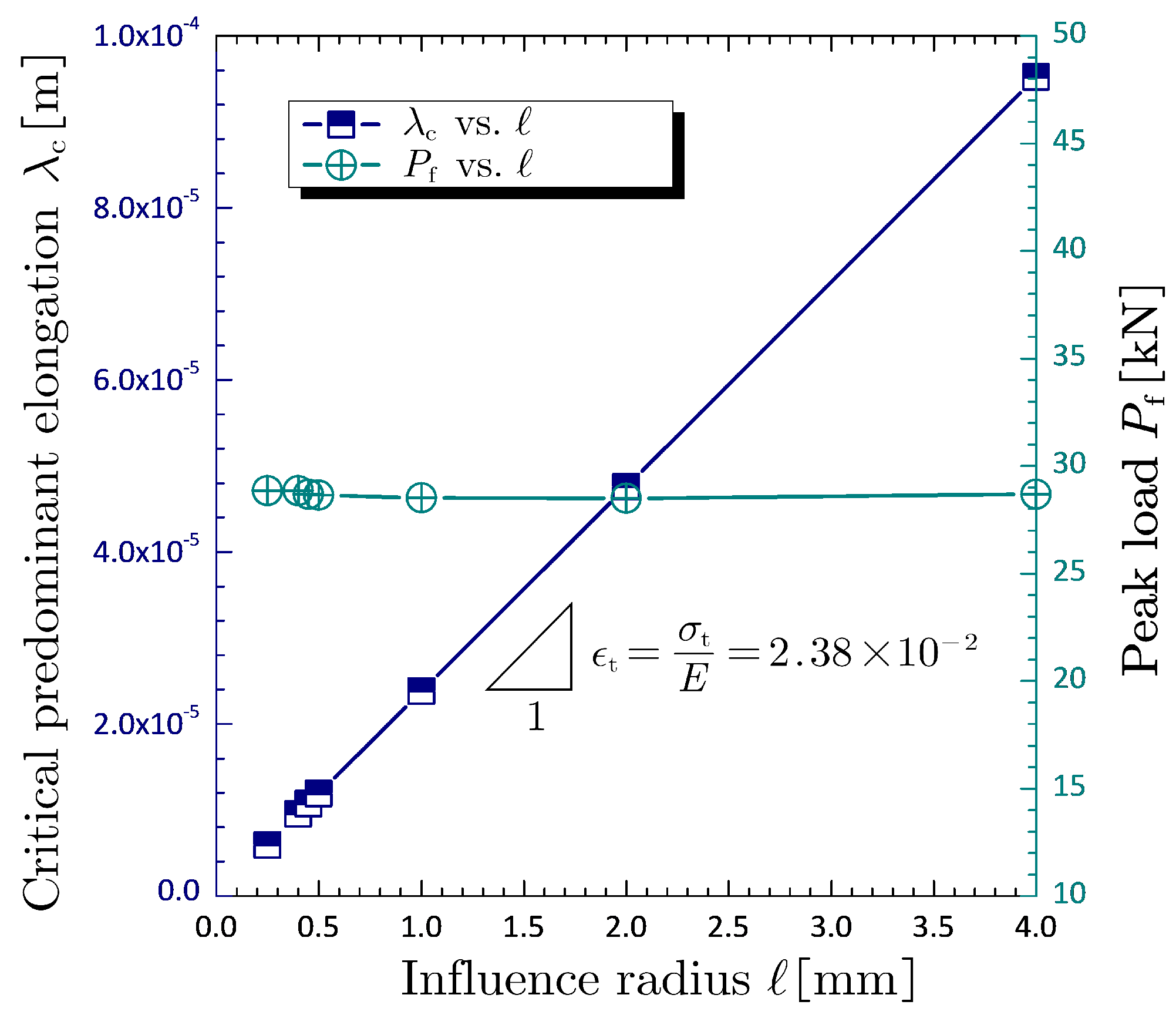

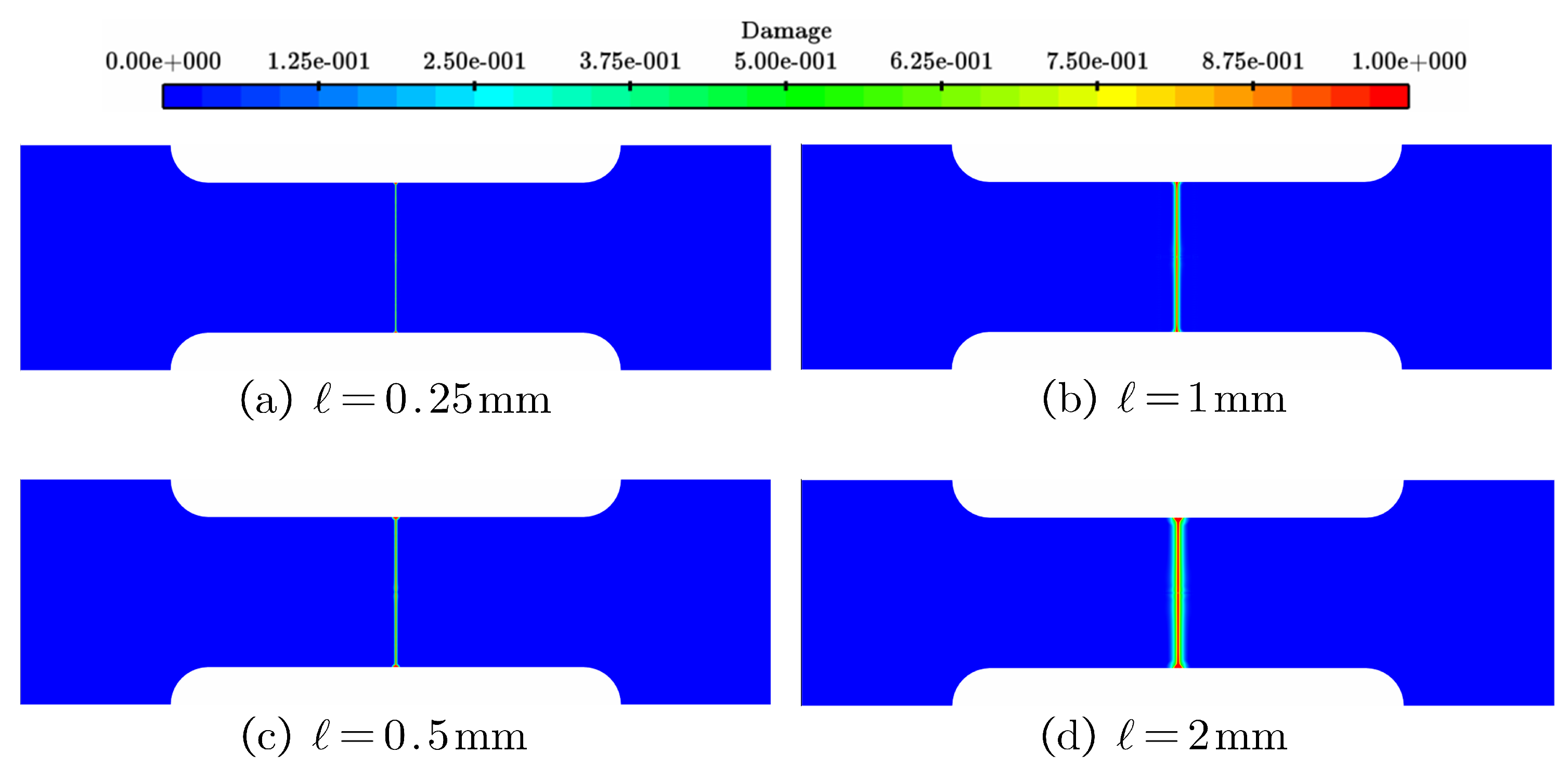

On that basis, we further investigate the calibration of critical threshold and influence radius, and the parameter setting is listed in

Table 3. In these cases, the degradation parameter is consistently limited to a fixed constant (i.e.,

) and the critical threshold varies in direct proportion to influence radius, namely

. The corresponding results of NMMD model are shown in

Figure 6, in which the peak load of all cases almost equals to the experimental result when the proportion keeps a constant

. It is of interest to find that the proportion is exactly equivalent to the experimental critical strain, that is

for cracking problems without singular stress concentration.

Besides, the load-deformation curve of all cases (though not shown here) are very similar to that as shown in

Figure 5, and fairly closed to each other. Several damage profiles with regard to different values of influence radius are also shown in

Figure 7. It seems that there are infinitely many pairs of critical threshold and influence radius satisfying the requirement of NMMD model in simulating the failure process of PMMA-like material.

However, in our previous analyses, e.g., Lu and Chen (2020 [

1]), Ren et al. (2024 [

3]) and Lu et al. (2024 [

4]), the numerical results without exception point to the fact that the influence radius (i.e., characteristic length) should be deemed as a certain kind of physical or material property, rather than the mathematically fictitious parameter as argued in phase-field model (Wu 2017 [

18]; Feng et al. 2021 [

19]) and gradient damage model (Xue and Ren 2023 [

21]). In other words, the influence radius in NMMD model should be identifiable and measurable in physical meaning. The further results and discussion are arranged in the next subsection.

4.2. Dog-Bone Specimen with Different Sizes of Circular Hole

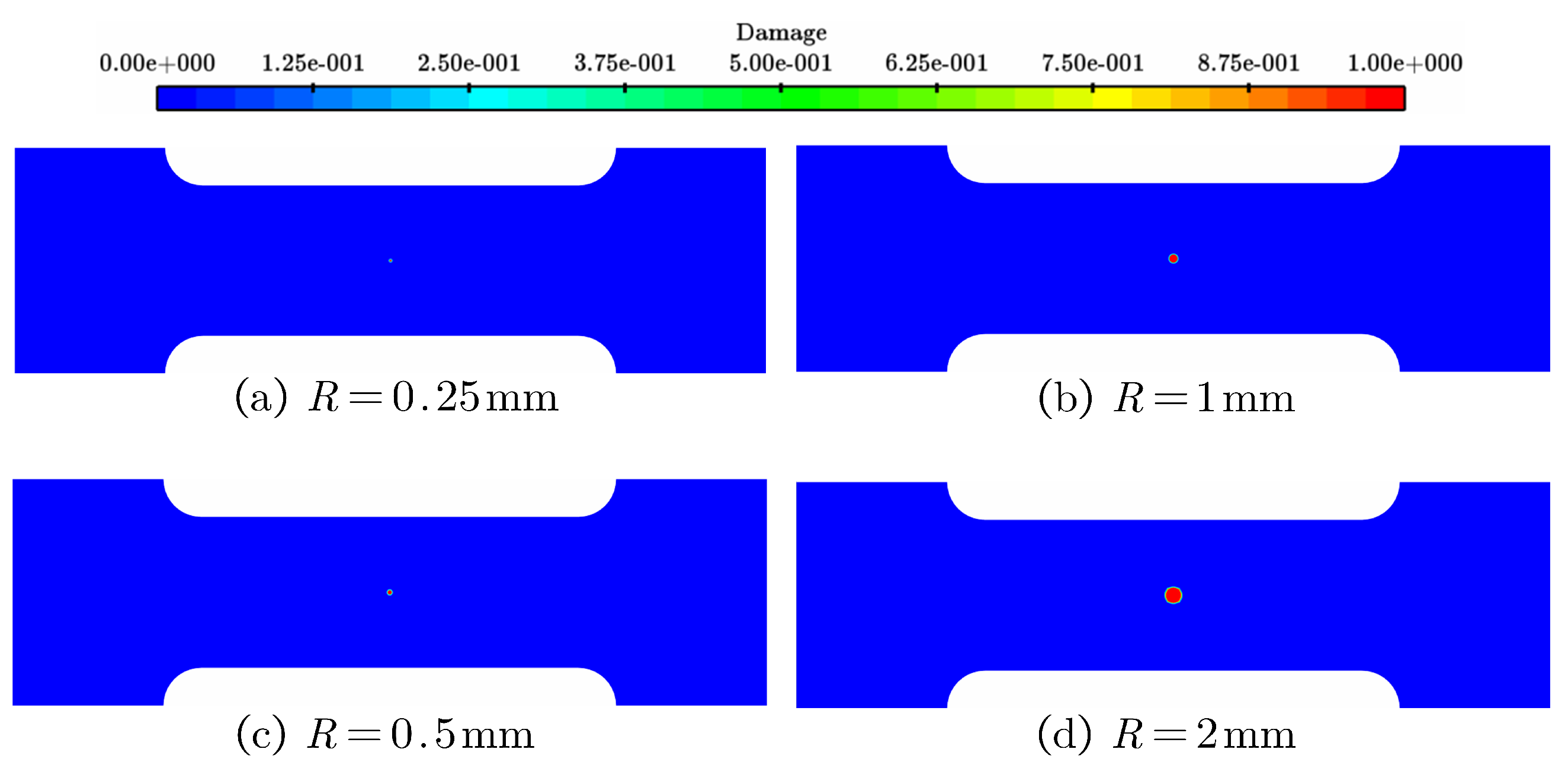

Now let us turn to the cases with different sizes of circular hole. Shown in

Figure 8 are the initial profiles before accessing to the main program of NMMD model, in which the radius of circular hole is considered to be the same size as experiments (Sapora et al. 2018 [

22]), i.e.,

. Before analysis the topology damage at the pre-existing circular hole is set to one (i.e., the empty material in geometry).

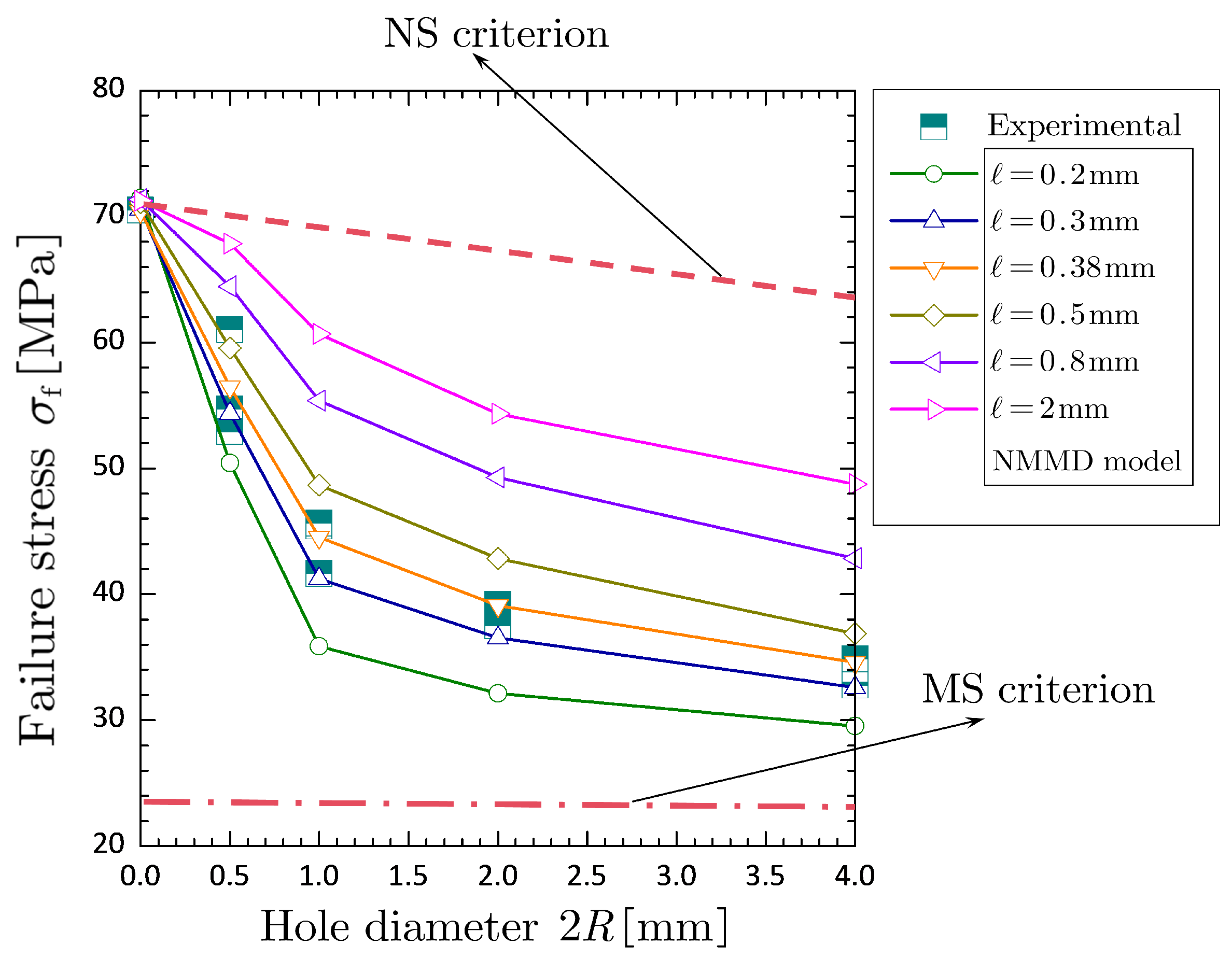

Figure 9 shows the numerical results (namely failure stress) with respect to various sizes of influence radius. As can be seen, the predictions of NMMD model would approximate that of MS criterion as the influence radius tends to zero and reach that of NS criterion when enlarging the influence radius. Among these results, the influence radius

is inferred from the phenomenological evidence that its result perfectly fits the experimental observations in regard to various sizes of hole.

From the above analyses, it can be seen that the characteristic length (i.e., influence radius) is identifiable and can be uniquely determined by the underlying physical experiment. With the material characteristic length, the NMMD model is capable of handling the failure stress of brittle fracture with and without pre-existing defect fairly well. Excepting the critical state of brittle failure, actually, the NMMD model could provide the simulation of the process sequences from linearly elastic deformation to complete failure, as shown in

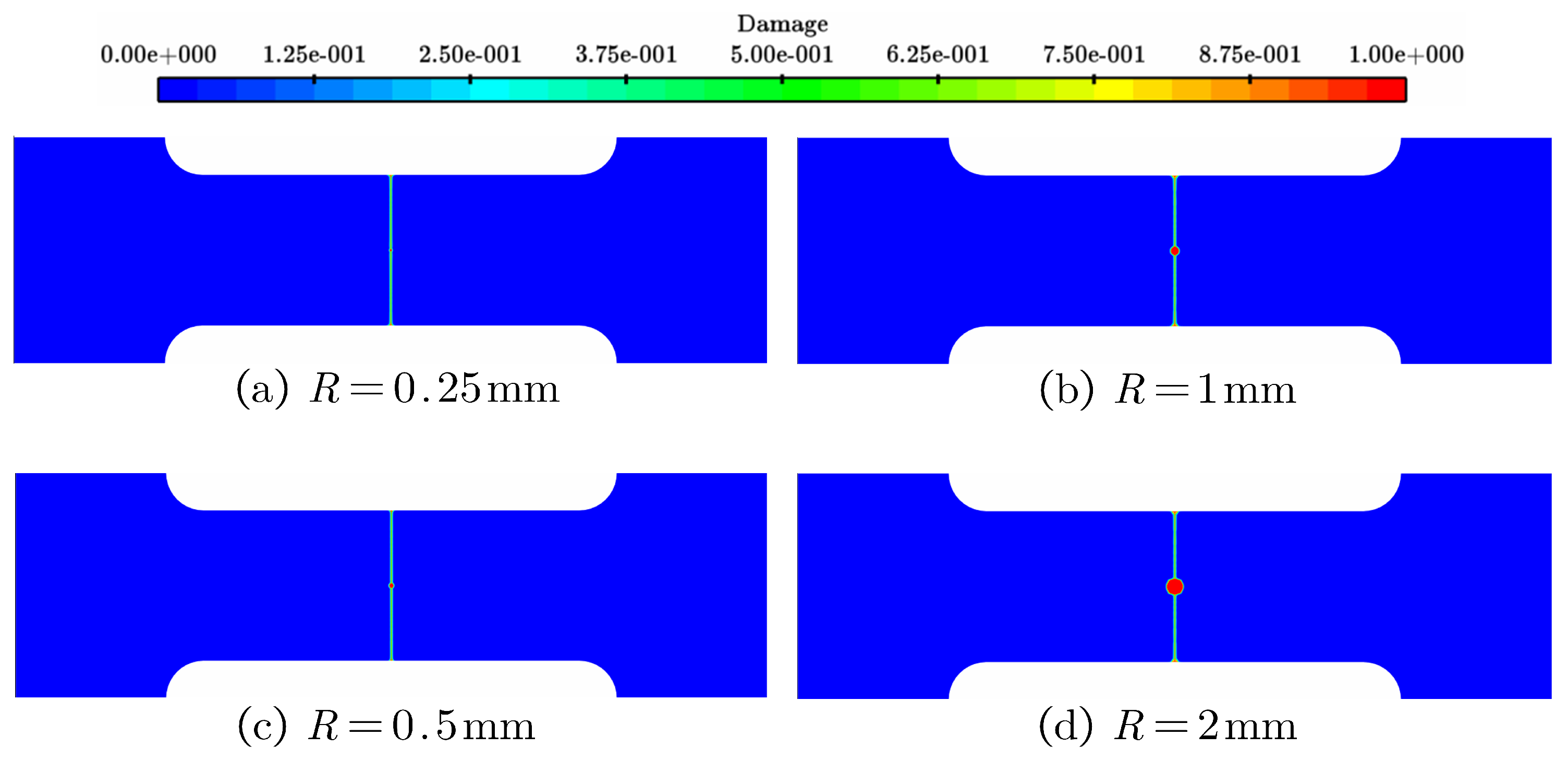

Figure 10 for the case of

with

.

It is worth noting that crack has already initiated and developed to a certain extent (almost equaling to the size of influence radius; see Step I in

Figure 10) when the load reaches its peak, which is consistent with many experimental observations, e.g., Romani et al. (2015 [

28]) and Yin et al. (2022 [

29]). Similar phenomenon also occurs in other sizes of circular hole.

Figure 11 only displays their final failure morphology for the sake of non-repetition. As such, one clearly sees that the blame for incapacity of the conventional local criteria (including MS criterion and NS criterion) is attributable to the lack of material characteristic length.

4.3. Theoretical Determination of the Influence Radius

It is highlighted that the selection of influence radius in NMMD model (see

Subsection 4.2) to numerically fit the experimental results is not for pleasing the eye but for aiming to assert the necessity and importance of involving characteristic length into the analysis of solid fracture. In the following, the theoretical determination of influence radius is further discussed.

Without loss of generality, the plane deformation problem is considered. Noting the fact that the crack has propagated slowly and steadily before the peak load is reached (see

Figure 10), we therefore start with the cracked body. According to the recent result (Lu et al. 2024 [

4]) that the crack topology represented by NMMD model always propagates along the direction of the maximum stress intensity factor of mode-I, which means the mixed mode brittle fracture can be equivalently transformed into the corresponding pure mode-I problem, hence we might as well focus on the mode-I loading, as shown in

Figure 12.

Based on fracture mechanics, referring to the polar coordinate system

, the stress field of mode-I near crack tip is expressed as (Tada et al. 2000 [

45], p.7)

where the coefficient

is the stress intensity factor of mode-I. Assume that the crack propagates with a small length scale

, as is well-known, the mode-I crack would extend along a straight line without kink-type deflection (i.e.,

). For plane stress problems concerned in this paper, by applying the generalized Hooke’s law the corresponding strain field along the crack has

as

, where Irwin’s criterion (i.e.,

) in linear elastic fracture mechanics (Anderson 2005 [

46],p. 15) is employed for the extended crack.

According to Equation (

5), right before crack propagation the maximum predominant elongation should occur at those material point-pairs which are perpendicular to the crack and pass through the crack tip, that is

where

and

are the distances of material points

and

from crack tip

(see

Figure 12 for the illustration). Substituting Equation (

18) into (

19) and noting the evolution of meso-scale damage for brittle material, i.e., Equations (

6) and (

14), we have

Recalling the relationship between the critical threshold of and critical strain in Equation (

16), furthermore, with combination of Equation (

20) the influence radius in NMMD model can be theoretically determined by the solution, i.e.,

This relationship is very similar to Irwin’s length (namely the size of crack-tip-yielding zone) in elastic-plastic fracture mechanics (Anderson 2005 [

46], p. 61) with small scale yielding, that is,

, where

is the yield strength. It means that even in brittle material once crack growth is initiated, stresses at the crack tip would not be infinite. In this process, the irreversible breakage of meso-scale bonds, accompanied by the energetic degradation, leads to the further stress relaxation of crack-tip.

It is of interest to check that by substituting the material properties of PMMA material listed in

Table 1 the theoretical influence radius

in Equation (

21) is very closed to the numerically identified one

as discussed previously in

Subsection 4.2. This result asserts again that the influence radius should not be construed to a mathematically fictitious parameter, but rather the physically-based material property.

5. Comparison with Other Modified Nonlocalized Criteria

Not coincidentally, in contrast to conventional local criteria (e.g., MS criterion and NS criterion), there are many modified nonlocalized criteria involving some kind of characteristic length, see Seweryn and Łukaszewicz (2002 [

30]), Li and Zhang (2005 [

24]) and Sapora et al. (2018 [

22]) for the overview perspective. Among those modified criteria, the line method (LM; Novozhilov 1969 [

31], Seweryn 1994 [

32]), the quantized fracture mechanics (QFM; Seweryn and Łukaszewicz 2002 [

30], Pugno and Ruoff 2004 [

33]) and the finite fracture mechanics (FFM; Carpinteri et al. 2008 [

34]) criteria are the representative works. In this section, discussions are devoted to the comparison between NMMD model and the above three modified criteria. To be consistent, examples of dog-bone specimen with a circular hole (Sapora et al. 2018 [

22]) as previously discussed are still considered.

In LM criterion (Seweryn 1994 [

32]), assuming that failure occurs when the averaged stress ahead of failure location over a segment of length

reaches the specified strength, it states

and therefore,

where

is a certain kind of stress measure normal to the cracking direction.

Similarly, the QFM criterion (Pugno and Ruoff 2004 [

33]) supposes that failure is achieved when the accumulated energy release rate

G with regard to

(namely the crack extension) reaches the critical value

, that is

and therefore,

where

a denotes the length of crack (already present or not).

The combination of LM criterion and QFM criterion gives birth to the FFM criterion (Carpinteri et al. 2008 [

34])

where the characteristic length

is considered as an unknown quantity to be solved in Equation (

26).

It is clear that the above three criteria are essentially nonlocalized criteria. In application to the failure analysis of dog-bone specimen with circular hole, the stress component

in LM criterion (

22) and FFM criterion (

26) is chosen as

And with Irwin’s relationship (Anderson 2005 [

46], p. 15) the energy release rate and fracture energy in QFM criterion (

24) and FFM criterion (

26) can be related to the stress intensity factor and fracture toughness respectively, i.e.,

where the stress intensity factor is expressed as (Tada et al. 2000 [

45], p.289)

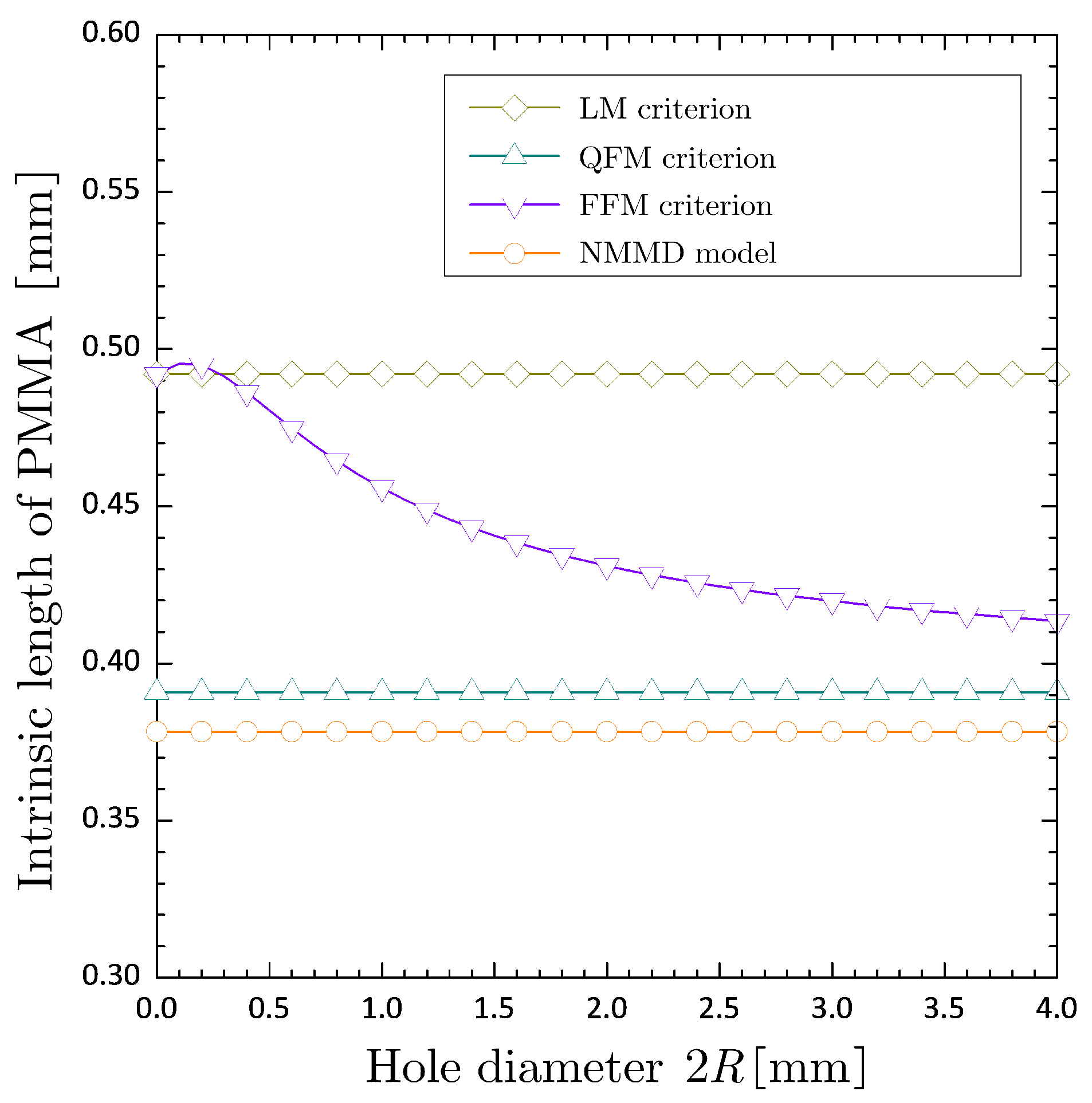

By substituting the material properties of PMMA in

Table 1, results of the above three criteria, including failure stress and the characteristic length, along with that of NMMD model and experiment (Sapora et al. 2018 [

22]), are shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

As can be seen from Figure

13, LM criterion always provides the lower bound of the experimental failure stress for various sizes of circular hole, while the results of QFM criterion suffer the maximum percentage discrepancy (i.e.,

) for the case without hole. Due to the coupling of LM and QFM criteria, the FFM criterion could effectively suppress the discrepancy at the case without hole suffered by QFM criterion, but not be of much assistance to improve the accuracy of cases with finite size of circular hole as predicted by LM criterion. Anyway, the FFM criterion pays a heavy price for overcoming the incongruence of QFM criterion, that is, the material constant stipulation of characteristic length, shown in Figure

14. Actually, as noticed that the LM, QFM and FFM criteria are all nonlocalized criteria. If it is further noticed that the energy release rate itself is a nonlocalized quantity (Lu et al. 2024 [

4]), QFM and FFM are twice averaged, which is physically not convincingly reasonable. This might interpret why QFM and FFM criteria seem not as good as LM criterion. Compared with the above three modified criteria, the NMMD model with the theoretically-determined influence radius (namely the material constant

) provides the best prediction for the mean values of experimentally-measured failure stress.

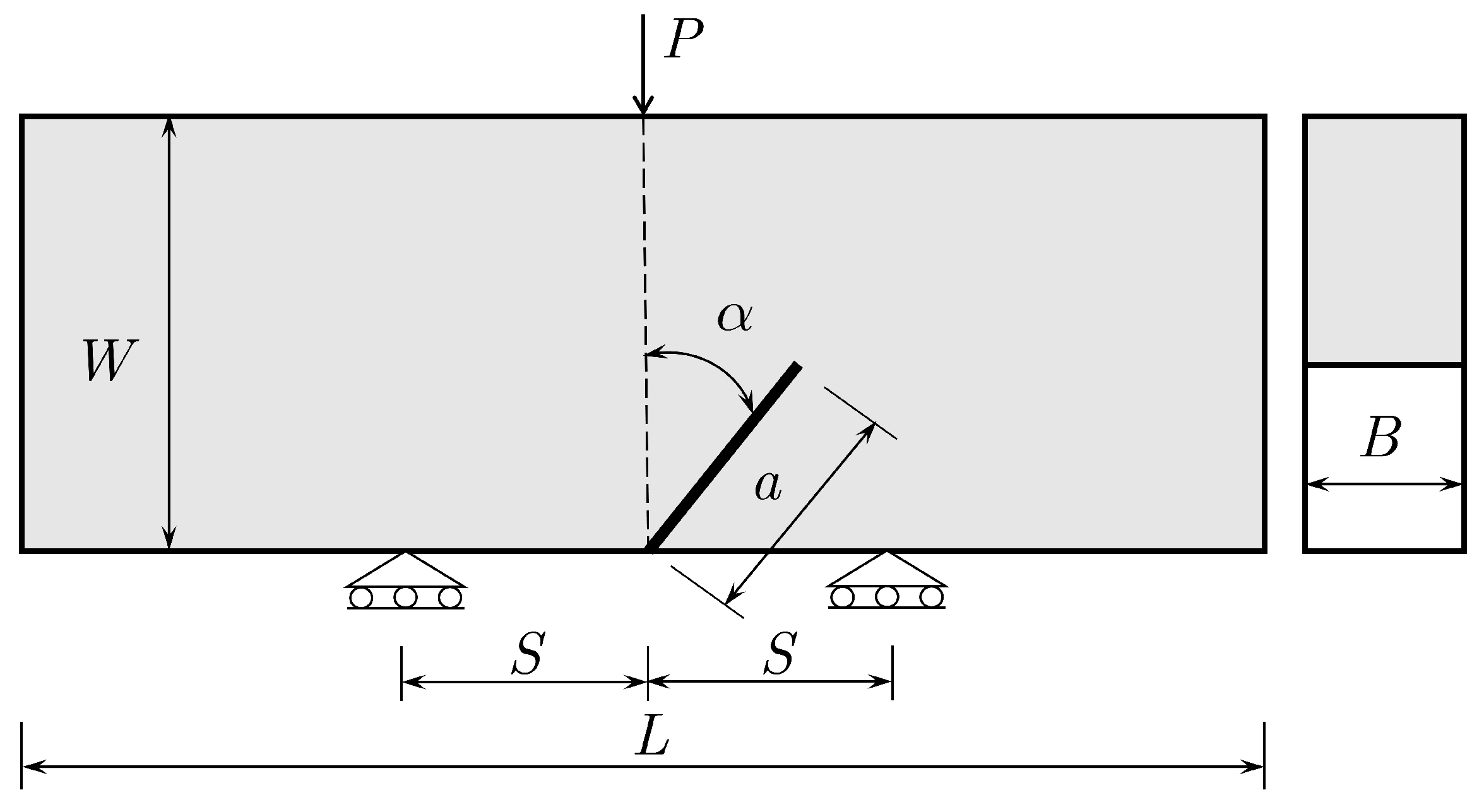

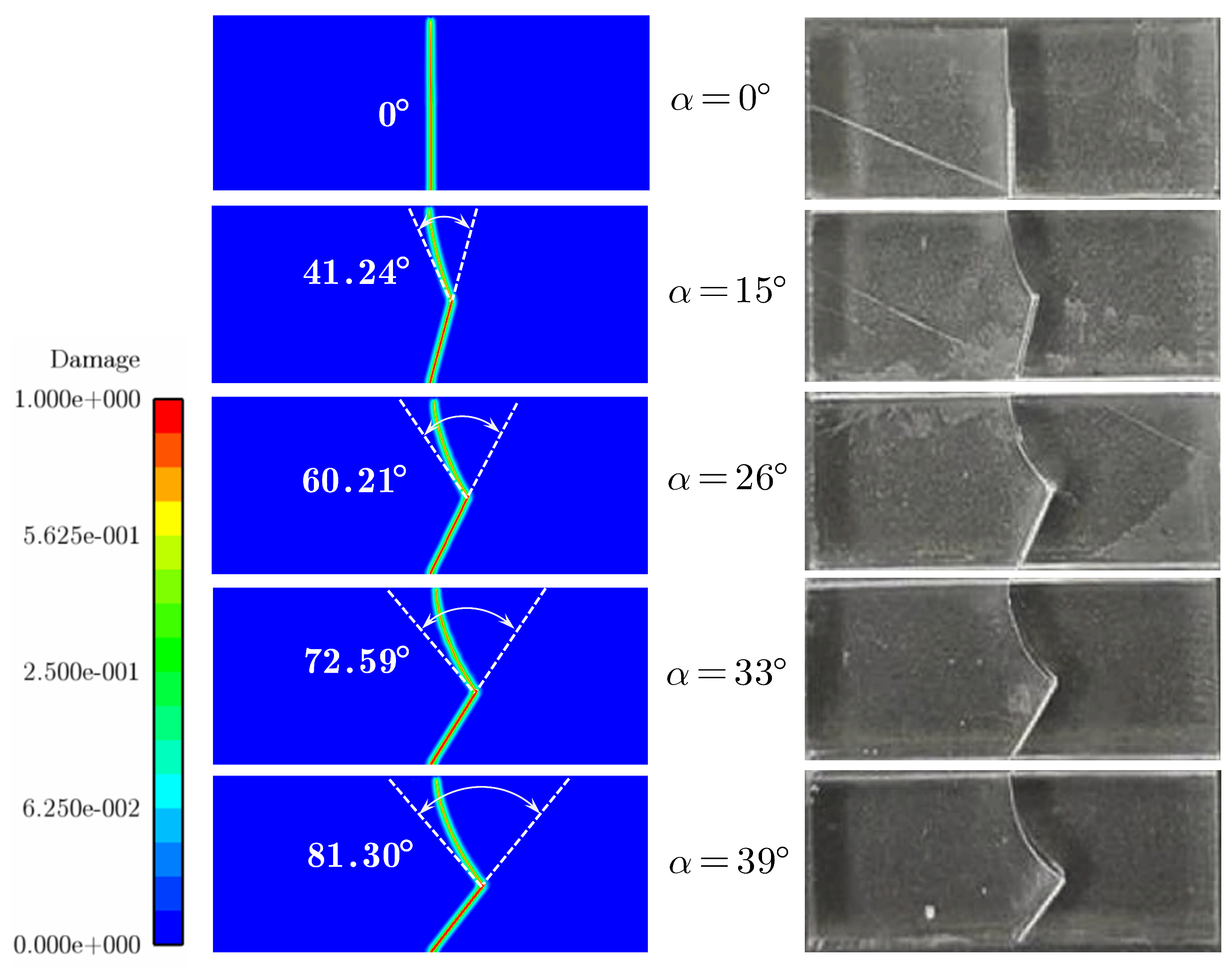

6. Revalidation: Mixed-Mode Fracture from Notch-Tip with Stress Singularity

Another experiment needed to be further investigated is the short bending beams with a pre-existing crack as reported in Mousavi et al. (2020 [

35]) and Aliha et al. (2021 [

36]).

Figure 15 illustrates the details of geometry, loading and boundary condition. Specifically, the length, width and thickness of specimens were considered as:

,

and

. In each specimen, the pre-existing crack with length

makes an inclination angle

relative to the vertical direction, two simple-supports with the span

were symmetrically placed at the bottom surface of the beam, and the vertical concentrated force

P was loaded at the midpoint of the top surface. These specimens were also made of PMMA material, and mechanical properties are listed in

Table 4, which are a bit different (namely the lower strength and the higher fracture toughness) from the sample in

Table 1 as investigated in Sapora et al. (2018 [

22]).

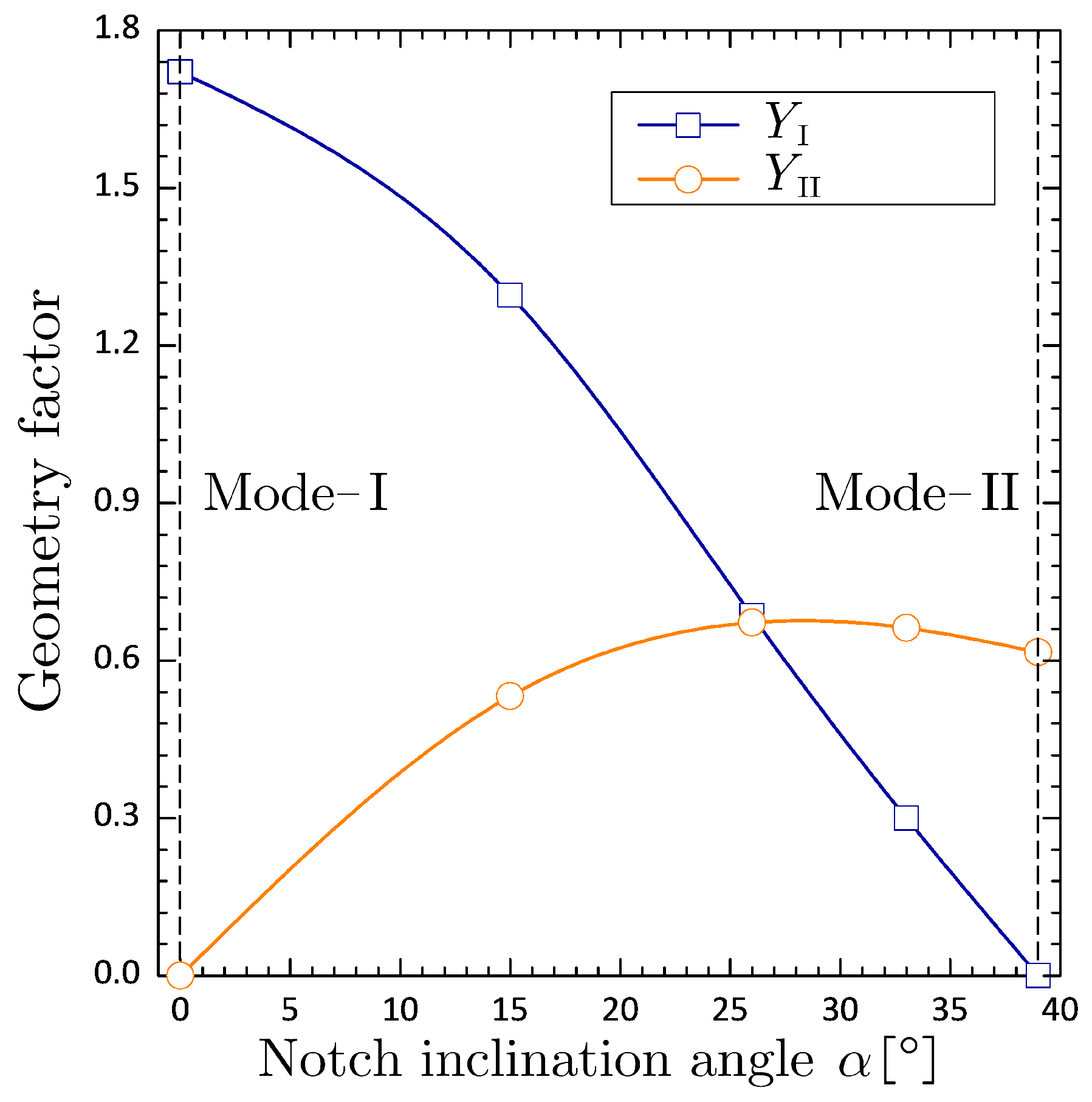

In the short bending beams, stress intensity factors of mode-I and mode-II are functions as follows (Mousavi et al. 2020 [

35])

where

and

are the geometry factors corresponding to crack length ratio

, loading span ratio

and crack inclination angle

. For the tested specimens, the variations of geometry factors respect to different inclination angles are shown in

Figure 16. Five inclination angles (i.e.,

) were set to investigate cracking behaviors of different loading mode mixtites from pure mode-I (

) to pure mode-II (

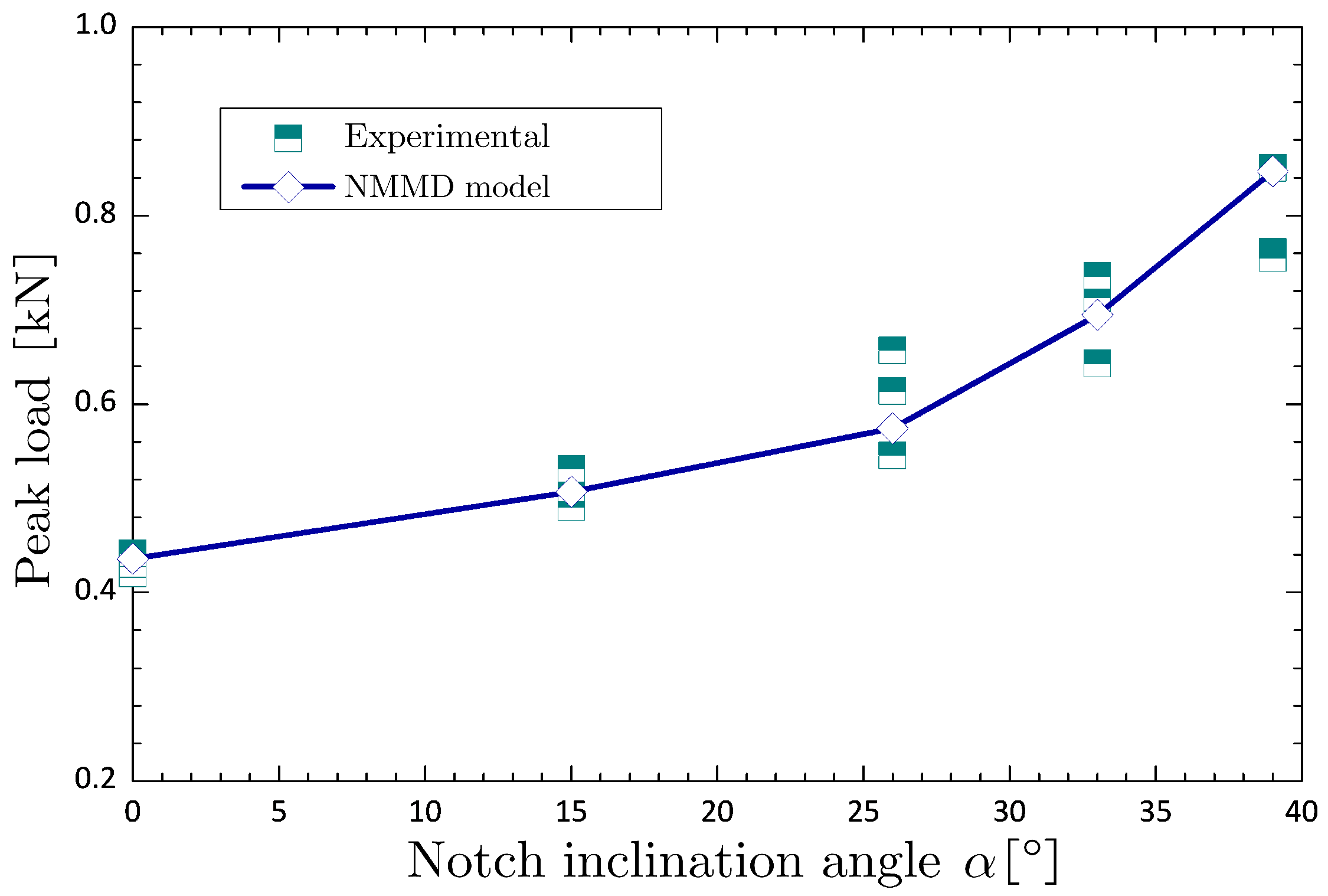

).

By advocating Equations (

16) and (

21), the influence radius and the critical threshold in NMMD model are calibrated as

and

according to mechanical properties listed in

Table 4. As can be seen, the influence radius for this example is slightly larger than that in the previous dog-bone specimens due to the lower strength and the higher fracture toughness. Numerical results including crack propagation path and peak load, together with experimental observations (Mousavi et al. 2020 [

35]; Aliha et al. 2021 [

36]) are shown in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18. It is found that the crack propagation paths from mode-I to mode-II loadings obtained by NMMD model are quite close to that observed in experiments. Meanwhile, the corresponding peak loads vary within the scope of experimental measurements. That is to say, the calibration procedure of NMMD model, i.e., Equations (

16) and (

21), though proposed for crack onset at non-singular stress concentration, is still suitable for problems of mixed mode fracture from notch-tip with stress singularity.

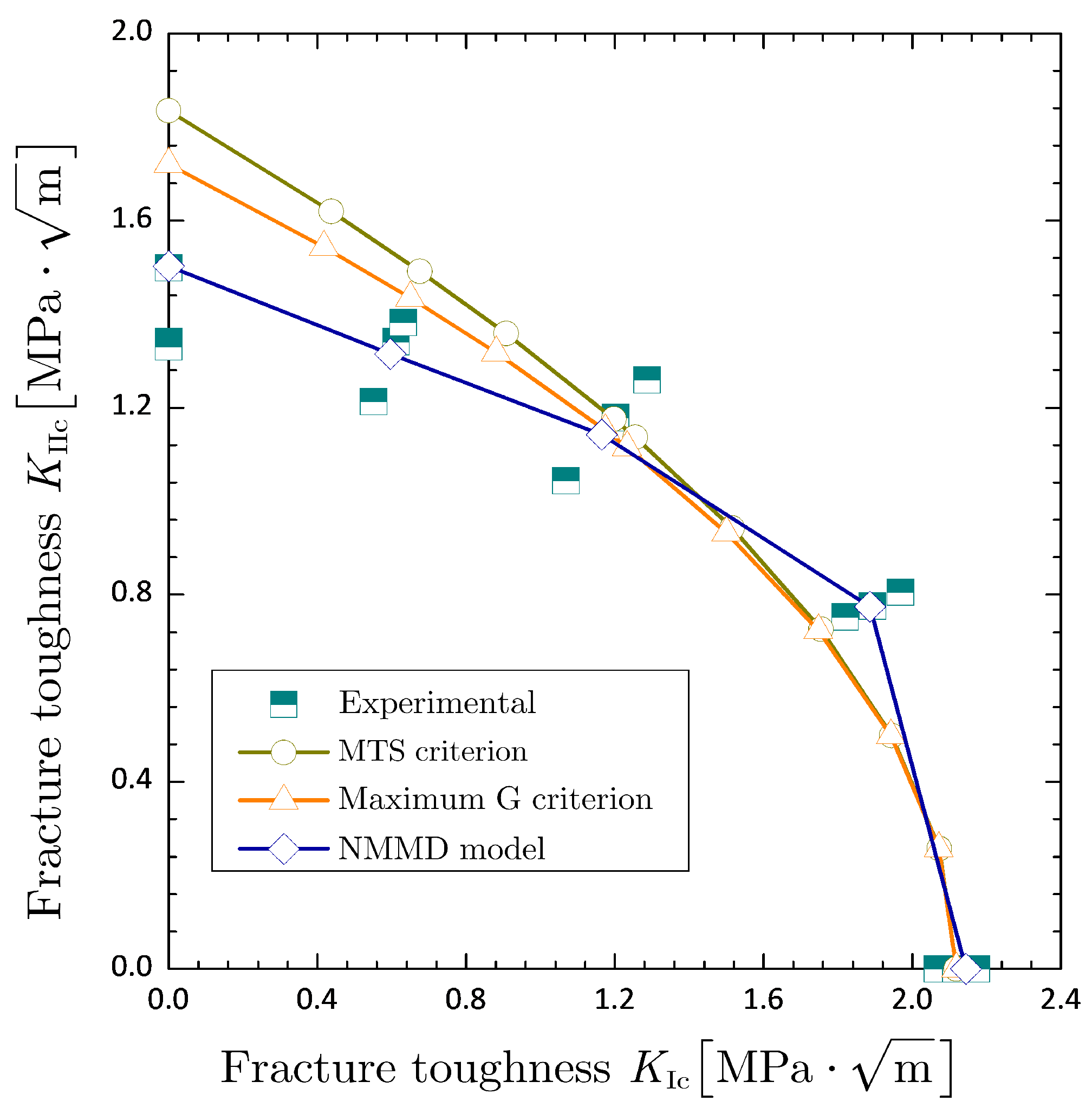

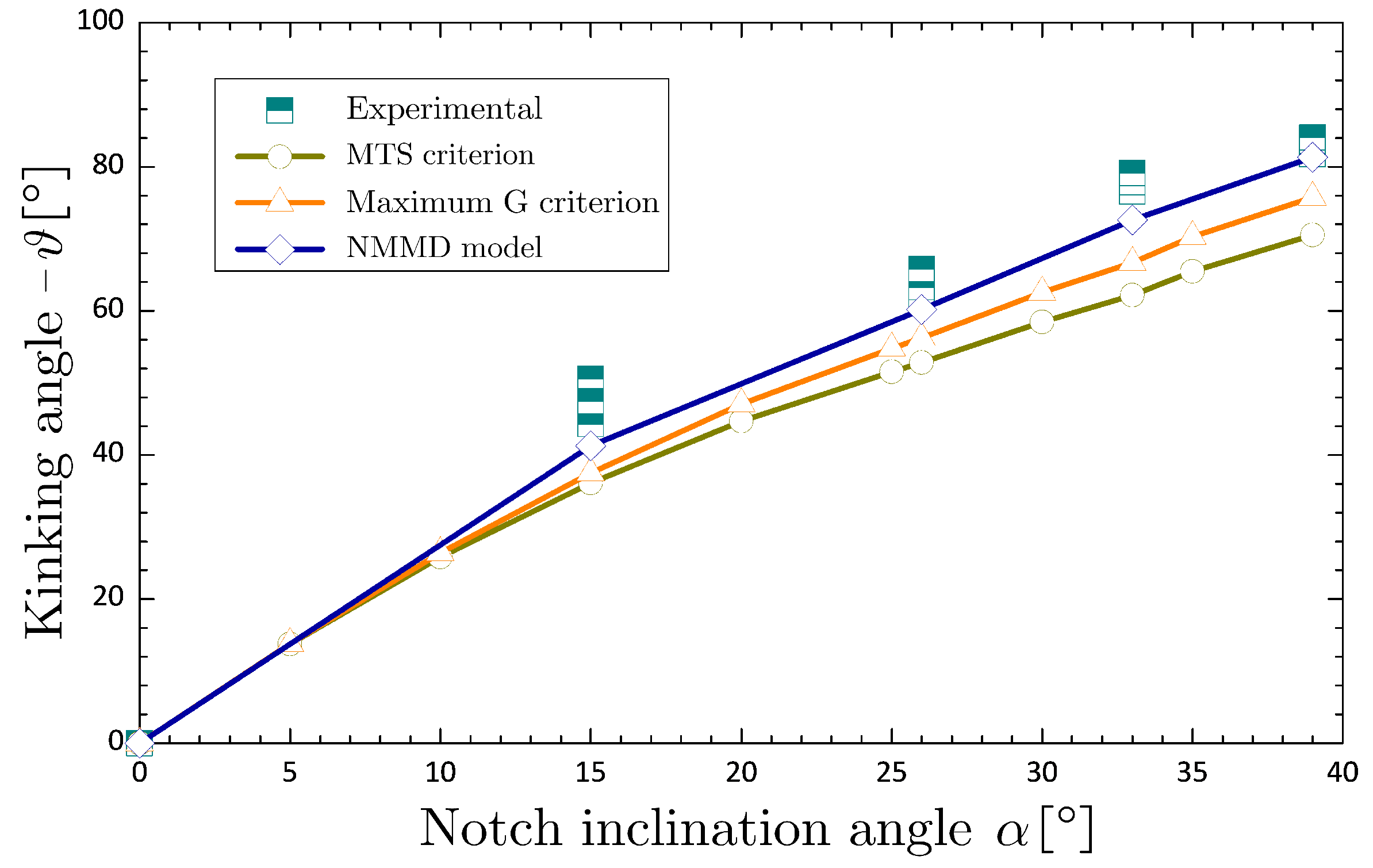

Such problems of short bending beam with a pre-existing crack, without a doubt, should belong to the scope of linear elastic fracture mechanics. However, as shown in

Figure 19, both predictions of fracture toughness by the two celebrated local criteria, the maximum tangential stress (MTS) criterion (Erdogan and Sih 1963 [

37]) and the maximum energy release rate (refers to as G) criterion (Wu 1978 [

38]), cannot yet provide satisfactory consistency with the experimental results, especially for the mode-II dominated loading conditions (i.e.,

or

; see

Figure 16). Other commonly-used criteria, such as the principle of local symmetry criterion (Gol’dstein and Salganik 1974 [

39]), the minimum strain energy density criterion (Sih 1974 [

40]) and the maximum tangential strain criterion (Chang 1981 [

41]), though not shown here, also encounter the similar discrepancies. As can be seen in

Figure 19, the NMMD model with the theoretically-determined influence radius obviously provides better predictions of fracture toughness under mixed-mode loadings. On the other hand, comparison of kinking angle (see

Figure 20) also confirms the assertion.

7. Concluding Remarks

In this work, we investigated the problems of crack onset at non-singular stress concentration and mixed-mode fracture from pre-existing notch-tip with stress singularity, in which predictions of the nonlocal macro-meso-scale consistent damage (NMMD) model, the conventional local criteria and the modified nonlocalized criteria, are discussed and compared with the corresponding experimental results. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

(1) The conventional local criteria (e.g., maximum stress (MS) criterion and net stress (NS) criterion) cannot predict the experimentally-observed failure stress of specimens containing various sizes of circular defect with satisfaction due to the lack of involving characteristic length, whereas the NMMD model is capable of providing adequate critical loads consistent with experimental data for the size effect of defect.

(2) For brittle materials like PMMA all the parameters in NMMD model can be uniquely determined by standard specimens (e.g., the dog-bone specimen) with and without defect in company. The most important parameter in NMMD model, i.e., the influence radius (also called the characteristic length), is proved to be directly measurable in experiments, and theoretically it is related to the ratio of fracture toughness to tensile strength of the material.

(3) Compared to the modified nonlocalized criteria also involving characteristic length (e.g., line method criterion, quantized fracture mechanics criterion and finite fracture mechanics criterion), the NMMD model is not only able to predict the critical loads in higher accuracy with regarding to experimental results but also able to quantitatively provide crack morphologies from initiation to propagation.

(4) The calibration procedure proposed for NMMD model is suitable for both brittle fracture problems of crack onset at non-singular stress concentration and mixed mode cracking from notch-tip with stress singularity. The results show a remarkable improvement in prediction of fracture toughness and kinking angle in comparison to the celebrated local criteria in linear elastic fracture mechanics, such as the maximum tangential stress criterion and the maximum energy release rate criterion.

These investigations imply that the NMMD model constitutes a promising tool for prediction of failure load and crack evolution in brittle materials. Even so, much more should be done in the future, including extensions of this work to failure analysis of quasi-brittle and heterogeneous materials, e.g., concrete, asphalt and rock mass.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 12202314)

Data Availability Statement

Data supplied on request.

Acknowledgments

The support of National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 12202314) is highly appreciated. We are highly grateful to Prof. Jianbing Chen from Tongji University for his instructive comments and great encouragement, and to Mr. Yudong Ren and Mr. Jiankang Xie from Tongji University for their constructive discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Examination of the Applicability of Analytical Stress Solution to Specimens of Finite Size

The analytical stress solution around a circular hole shown in Equation (

1) is obtained by advocating the hypothesis of infinite plate. To investigate the applicability to specimens of finite size, we take one-quarter of dog-bone specimen with circular hole (mainly the core-part) as an example. Shown in

Figure A1 (a) is the corresponding geometry, loading and boundary conditions similar to that as described in

Section 2, and

Figure A1 (b) displays an example of finite element mesh with respect to the case of hole radius

. In analysis, the material properties are taken from

Table 1, and the applied tensile stress is set as

without loss of generality.

Figure A1.

A quarter of the dog-bone specimen with circular hole (mainly the core-part): (a) geometry, loading and boundary conditions; (b) scheme of finite element mesh.

Figure A1.

A quarter of the dog-bone specimen with circular hole (mainly the core-part): (a) geometry, loading and boundary conditions; (b) scheme of finite element mesh.

Shown in

Figure A2 is the comparison between the finite element results and the analytical solutions with respect to various sizes of hole radius (as investigated in the experiment), in which the stress component

along the cross section

(see

Figure A2) is focused. It can be seen that even referring to logarithmic coordinate the discrepancy between numerical result and analytical solution is very low and thus can be ignored, e.g., for the case of

the discrepancy is still less than

.

Figure A2.

Comparison of finite element result and analytical solution with geometric conditions.

Figure A2.

Comparison of finite element result and analytical solution with geometric conditions.

References

- Lu, G. D.; Chen, J. B. A new nonlocal macro-meso-scale consistent damage model for crack modeling of quasi-brittle materials. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 2020,362, 112802. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. B.; Ren, Y. D.; Lu, G. D. Meso-scale physical modeling of energetic degradation function in the nonlocal macro-meso-scale consistent damage model for Quasi-Brittle materials. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 2021,374, 113588. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y. D.; Lu, G. D.; Chen, J. B. Physically consistent nonlocal macro–meso-scale damage model for quasi-brittle materials: A unified multiscale perspective. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2024,293, 112738. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G. D.; Chen, J. B; Ren, Y. D. New insights into fracture and cracking simulation of quasi-brittle materials based on the NMMD model. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 2024,432 Part B, 117347.

- Ren, Y. D.; Chen, J. B; Lu, G. D. A structured deformation driven nonlocal macro-meso-scale consistent damage model for the compression/shear dominate failure simulation of quasi-brittle materials. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 2023,410, 115945. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G. D.; Chen, J. B. Dynamic cracking simulation by the nonlocal macro-meso-scale damage model for isotropic materials. J. Numer. Methods Engrg. 2021,122 (12), 3070–3099. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y. D.; Chen, J. B; Lu, G. D. Mesoscopic simulation of uniaxial compression fracture of concrete via the nonlocal macro-meso-scale consistent damage model. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024,304, 110148. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. Z.; Wang, X.; Lu, G. D.; Gu, X.; Lv, W. F.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.Z. A new nonlocal macro-micro-scale consistent damage model for layered rock mass. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 2024,133 Part A, 104540. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. W.; Du, C. B.; Sun,L. G.; Du, N. Y. Simulation of the dynamic cracking of brittle materials using a nonlocal damage model with an effective strain rate effect. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 2024,418, 116579. [CrossRef]

- Eringen, A. C. On nonlocal plasticity. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1981,19 (12), 1461-1474. [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z. P.; Belytschko, T. B.; Chang, T. P. Continuum theory for strain-softening. J. Eng. Mech. 1984,110 (12), 1666-1692. [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z. P.; Jirásek, M. Nonlocal integral formulations of plasticity and damage: survey of progress. J. Eng. Mech. 2002,128 (11), 1119-1149. [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z. P.; Pijaudier-Cabot, G. Measurement of characteristic length of nonlocal continuum. J. Eng. Mech. 1989,115 (4), 755-767. [CrossRef]

- Silling, S. A. Reformulation of elasticity theory for discontinuities and long-range forces. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2000,48 (1), 175-209. [CrossRef]

- Silling, S. A.; Lehoucq, R. B. Peridynamic theory of solid mechanics. Adv. Appl. Mech. 2010,44, 73-168.

- Bourdin, B.; Francfort, G. A.; Marigo, J. J. Numerical experiments in revisited brittle fracture. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2000,48 (4), 797–826. [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, B.; Francfort, G. A.; Marigo, J. J. The variational approach to fracture. J. Elasticity 2008,91, 5-148. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Y. A unified phase-field theory for the mechanics of damage and quasi-brittle failure. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2017,103, 72-99. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Fan, J.; Li, J. Endowing explicit Cohesive laws to the phase-field fracture theory. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2021,152, 104464. [CrossRef]

- Peerlings, R. H.; de Borst, R.; Brekelmans, W. M.; de Vree, J. Gradient enhanced damage for quasi-brittle materials. Internat. J. Numer. Methods Engrg. 1996,39 (19), 3391-3403. [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Ren, X. D. Achieving irreversibility in damage evolution: Extended gradient damage model with decoupled damage profile and cohesive law. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2024,183, 105524. [CrossRef]

- Sapora, A.; Torabi, A. R.; Etesam, S.; Cornetti, P. Finite fracture mechanics crack initiation from a circular hole. Fatigue Fract. Eng. M. 2018,41 (7), 1627-1636. [CrossRef]

- Carter, B. J. Size and stress gradient effects on fracture around cavities. Rock Mech. Rock Engng. 1992,25 (3), 167-186. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X. B. A criterion study for non-singular stress concentrations with size effect. Strength Fract. Comp. 2005,3 (2-4), 205-215.

- Torabi, A. R.; Etesam, S.; Sapora, A.; Cornetti, P. Size effects on brittle fracture of Brazilian disk samples containing a circular hole. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2017,186, 496-503. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. B.; Xie, J. K.; Lu, G. D. A new exploration of mesoscopic structure in the nonlocal macro-meso-scale consistent damage model for quasi-brittle materials. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 2024,432 Part B, 117456. [CrossRef]

- May, I. M.; Duan, Y. L. A local arc-length procedure for strain softening. Comput. Struct. 1997,64 (1-4), 297-303.

- Romani, R.; Bornert, M.; Leguillon, D.;Le Roy, R.; Sab, K. Detection of crack onset in double cleavage drilled specimens of plaster under compression by digital image correlation–theoretical predictions based on a coupled criterion. Eur. J. Mech. A-Solid 2015,51, 172-182. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Reinhardt, H. W.; Xu, S. L. The double-K fracture model: A state-of-the-art review. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023,277, 108988. [CrossRef]

- Seweryn, A.; Łukaszewicz, A. Verification of brittle fracture criteria for elements with V-shaped notches. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2002,69 (13), 1487-1510. [CrossRef]

- Novozhilov, V. V. On a necessary and sufficient criterion for brittle strength. J. Appl. Math. Mec. 1969,33 (2), 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Seweryn, A. Brittle fracture criterion for structures with sharp notches. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1994,47 (5), 673-681. [CrossRef]

- Pugno, N. M.; Ruoff, R. S. Quantized fracture mechanics. Philos. Mag. 2004,84 (27), 2829-2845. [CrossRef]

- Carpinteri, A.; Cornetti, P.; Pugno, N.; Sapora, A.; Taylor, D. A finite fracture mechanics approach to structures with sharp V-notches. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2008,75 (7), 1736-1752. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S. S.; Aliha, M. R. M.; Imani, D. M. On the use of edge cracked short bend beam specimen for PMMA fracture toughness testing under mixed-mode I/II. Polym. Test. 2020,81, 106199. [CrossRef]

- Aliha, M. R. M.; Samareh-Mousavi, S. S.; Mirsayar, M. M. Loading rate effect on mixed mode I/II brittle fracture behavior of PMMA using inclined cracked SBB specimen. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2021,232, 111177. [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, F.; Sih,G. C. On the crack extension in plates under plane loading and transverse shear. J. Basic Eng. 1963,85 (4), 519-525. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. H. Maximum-energy-release-rate criterion applied to a tension-compression specimen with crack. J. Elasticity 1978,8 (3), 235-257. [CrossRef]

- Gol’dstein, R. V.; Salganik, R. L. Brittle fracture of solids with arbitrary cracks. Int. J. Fracture 1974,10, 507-523. [CrossRef]

- Sih, G. C. Strain-energy-density factor applied to mixed mode crack problems. Int. J. Fracture 1974,10, 305-321. [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. J. On the maximum strain criterion—a new approach to the angled crack problem. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1981,14 (1), 107-124. [CrossRef]

- Timoshenko, S. P.; Goodier, J. N. Theory of Elasticity; McGraw-hill: New York, 1951.

- Li, J.; Wu, J. Y.; Chen, J. B. Stochastic Damage Mechanics of Concrete Structures [in Chinese]; Science Press: Beijing, 2014.

- Gurtin, M. E. An Introduction to Continuum Mechanics; Academic Press: New York, 1981.

- Tada, H.; Paris, P. C.; Irwin, G. R. The Stress Analysis of Cracks Handbook, 3rd ed.; ASME Press: New York, 2000.

- Anderson, T. L. Fracture Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications, 3rd ed.; CRC press: Boca Raton, 2005.

Figure 1.

Dog-bone specimen with a circular hole: Geometry, loading and boundary conditions.

Figure 1.

Dog-bone specimen with a circular hole: Geometry, loading and boundary conditions.

Figure 2.

Failure stress against hole diameter obtained from experiments (Sapora et al. [

22]) and the two commonly-used criteria.

Figure 2.

Failure stress against hole diameter obtained from experiments (Sapora et al. [

22]) and the two commonly-used criteria.

Figure 3.

The meso-structure of NMMD model.

Figure 3.

The meso-structure of NMMD model.

Figure 4.

Finite element mesh of the dog-bone specimen (total element number: 36600; the minimum size of element: 0.08 ).

Figure 4.

Finite element mesh of the dog-bone specimen (total element number: 36600; the minimum size of element: 0.08 ).

Figure 5.

Results of NMMD model for various degradation parameters.

Figure 5.

Results of NMMD model for various degradation parameters.

Figure 6.

Results of NMMD model for the variations of critical threshold and influence radius.

Figure 6.

Results of NMMD model for the variations of critical threshold and influence radius.

Figure 7.

Damage profiles of NMMD model with respect to different sizes of influence radius.

Figure 7.

Damage profiles of NMMD model with respect to different sizes of influence radius.

Figure 8.

Initial settings of damage profile for various sizes of circular hole.

Figure 8.

Initial settings of damage profile for various sizes of circular hole.

Figure 9.

Failure stress against hole diameter obtained from NMMD model.

Figure 9.

Failure stress against hole diameter obtained from NMMD model.

Figure 10.

Failure process for the case of hole radius with influence radius .

Figure 10.

Failure process for the case of hole radius with influence radius .

Figure 11.

Final damage profile of various sizes of hole radius with influence radius .

Figure 11.

Final damage profile of various sizes of hole radius with influence radius .

Figure 12.

Stress field near the crack tip in polar coordinates.

Figure 12.

Stress field near the crack tip in polar coordinates.

Figure 13.

Comparison of failure stress obtained by different approaches.

Figure 13.

Comparison of failure stress obtained by different approaches.

Figure 14.

Theoretical prediction of intrinsic length of PMMA by different approaches.

Figure 14.

Theoretical prediction of intrinsic length of PMMA by different approaches.

Figure 15.

Theoretical prediction of intrinsic length of PMMA by different approaches.

Figure 15.

Theoretical prediction of intrinsic length of PMMA by different approaches.

Figure 16.

Variations of geometry factor with respect to different notch inclination angles.

Figure 16.

Variations of geometry factor with respect to different notch inclination angles.

Figure 17.

Comparison of crack propagation path between NMMD model and experiments (Mousavi et al. 2020 [

35]; Aliha et al. 2021 [

36]).

Figure 17.

Comparison of crack propagation path between NMMD model and experiments (Mousavi et al. 2020 [

35]; Aliha et al. 2021 [

36]).

Figure 18.

Comparison of peak load between NMMD model and experiments (Mousavi et al. 2020 [

35]; Aliha et al. 2021 [

36]).

Figure 18.

Comparison of peak load between NMMD model and experiments (Mousavi et al. 2020 [

35]; Aliha et al. 2021 [

36]).

Figure 19.

Comparison of fracture toughness obtained by different approaches.

Figure 19.

Comparison of fracture toughness obtained by different approaches.

Figure 20.

Comparison of kinking angle obtained by different approaches.

Figure 20.

Comparison of kinking angle obtained by different approaches.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of PMMA material (Sapota et al. [

22]).

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of PMMA material (Sapota et al. [

22]).

| Tensile Strength |

Fracture Toughness |

Young’s Modulus |

Poisson’s Ratio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Parameter setting for variation of the degradation parameter.

Table 2.

Parameter setting for variation of the degradation parameter.

| Case |

Degradation parameter |

Critical threshold |

Influence radius |

| |

p |

|

|

| I |

4 |

|

1 |

| II |

5 |

|

1 |

| III |

6 |

|

1 |

Table 3.

Parameter setting for variations of critical threshold and influence radius.

Table 3.

Parameter setting for variations of critical threshold and influence radius.

| Case |

Degradation parameter |

Critical threshold |

Influence radius |

| |

p |

|

|

| A |

5 |

|

|

| B |

5 |

|

|

| C |

5 |

|

|

| D |

5 |

|

|

| E |

5 |

|

1 |

| F |

5 |

|

2 |

| G |

5 |

|

4 |

Table 4.

Mechanical properties of PMMA material (Aliha et al. 2021 [

36]).

Table 4.

Mechanical properties of PMMA material (Aliha et al. 2021 [

36]).

| Tensile Strength |

Fracture Toughness |

Young’s Modulus |

Poisson’s Ratio |

|

|

|

|

| 65 |

|

3 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).